#adam of bremen

Text

Where is Vanaheimr, Land of the Norse Nature Gods? | Ancient Origins

https://www.ancient-origins.net/myths-legends-europe/where-vanaheimr-land-norse-nature-gods-009654

View On WordPress

#13th century#Adam of Bremen#Aesir#Aesir-Vanir War#Alfheim#Asgard#Freyja#Freyr#Hel#Jotunheimr#Loki#Midgard#Muspelheim#Niflheim#Nine Realms#Nine Worlds#Njord#Norse#Norse Mythology#Norse Pantheon#Odin#Old Norse#Poetic Edda#Scandinavia#Snorri Sturluson#Svartalfaheim#Svartalfaheimr#Temple of Uppsala#Thor#Underworld

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Tatort Hamburg: Schattenleben (2022)

#tatort#tatort hamburg#julia grosz#thorsten falke#mine*#gifs*#besties#ich will ihnen immer noch einen award dafür geben dass sie beim Du angekommen sind ohne vorher miteinander im bett zu landen#weiß nicht ob das ein alleinstellungsmerkmal ist unter den m/f teams aber unter denen die ich gucke/geguckt hab wohl#honorable mention für olga/adam's letzte 10 minuten#warte. bremen auch oder.

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

you can’t convince me otherwise: tatort bremen and tatort saarbrücken are related

The fact that they both can’t sit on a chair/ table in a proper way…

(it’s giving everything it should give)

Plus the fact with the turtlenecks

adam and linda… i can see what you did there

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Remind me to never drink anything containing caffeine ever again.

#i have an expose and a bibliography due to * checks watch * today#and I haven't done anything for it and have been exhausted the entire day#my absolutism seminar did ABSOLUTEly not help with that#so I had 3 espresso shots and an energy drink and I don't know how to describe what I'm feeling but it's BaD#i usually don't drink any caffeine bc it makes me jittery#welp#but fuck if i haven't looked at sources y'know?#ansgar and adam of bremen I'm coming for your fucking throats#still have to look up more stuff abt the christianization of sweden and denmark but it'll be fiiiiiine#i think. hope. pray.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Harry Crosby put a lot of time and care into his work as a navigator. This is evident in Part 3 when he is adamant in his conversation with Douglass about getting the logs right and in Part 5 when Crosby had clearly been up all night working on and planning the mission to Bremen.

I can’t imagine how awful he must feel, the weight on his shoulders of feeling responsible for every plane that goes down. It’s not his fault, they’ll say, but their words don’t alleviate the burden he places on himself.

In his memoir, Crosby mentions going 75 hours straight without sleep during their planning for D-Day and I can almost guarantee that was not the first time he’d done such by that point. In fact, I’ll bet he threw himself even further into his work, neglecting his own needs without someone there to remind him to eat and sleep. There’s new faces everywhere he looks, fewer people to give a weak smile and a nod to as he passes by and therefore fewer reasons to leave his office.

Not a minute goes by where he doesn’t wish for a familiar face to burst through those doors and rescue him from himself. Until then he keeps working, unable to stop because in theory the sooner he gets back to work the sooner they could one day put an end to this godforsaken war and the sooner their men could come home. All he can do is hold onto hope that some of their men come home.

#Harry Crosby needs a hug#I need all of the fix it fics guys 👏👏👏#i will protect Croz with everything I have#the Harry Crosby protection squad is mia and he is not okay :(#Harry Crosby deserves better#they all do tbf#masters of the air#mota#mota musings#Harry Crosby

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

De Divino Trifunctionalismo Indo-Europæorum

I. Introduction

By the divine trifunctionalism I mean a set of three(+) core gods whom the Indo-Europeans kept & cherished even as they sundered & settled all over Eurasia. This set of gods can be recognized in every branch of the Indo-European religion that we have good knowledge of, except for that of the Hittites (who were overwhelmed with the cults they learned from their well-urbanized neighbors), and of the British & Irish (though I don’t despair of finding them there).

The pattern was, of course, first recognized by Georges Dumézil, but he was an atheist, and considered the gods not as individual persons, but as personifications of a set of three social classes, which, while likely a poetic trope, it is unclear that the Proto-Indo-Europeans actually founded their laws in. This belief led him to misstate his case, trying to match the gods in vain to these classes, and so flailingly trying to cut off parts of the gods’ characters. In fact all the trifunctional gods are kings, all work in war, and all are linked to the fruits of the land.

And indeed the trifunctional classes, or elements, of sacrificant, warrior, & farmer were considered to be all needed in the character of a lordly man, as seen in Romulus, Odysseus, Cincinnatus, Egill, and many other ideal lords.

II. Triads

Attestations of trifunctional triads include—I list them mainly in the order they occur in the texts but with numerals to match with Dumézil’s traditional 1st/2nd/3rd function assignments—

Theodiscan:

2. Thunder – 1. Woden – 3. “Fricco” (= O.N. *Frakka = Ing-Free): Temple of Uppsala according to Adam of Bremen.

2. Thunder – 1. Woden – 3. Sexneat: Old Saxon Baptismal Oath.

3. Ing-Free, Easter-Free, Nearth – 1. Woden – 3. Thunder: one of Hallfreð’s Óttarsson’s poems bitterly renouncing the gods for Christ.

Possibly also the set can be seen in the worldending duels sung at the end of the Völuspá viz. 1. Woden vs. Fennerswolf, 3. Ing-Free vs. Surt, 2. Thunder vs. Midyardsworm—here Wider intervenes after Woden’s fall, though the stanza may be illplaced—and perhaps in the “1. Mercurius, 2. Herculés, & 3. Márs” reported by Tacitus. (I’ll take this moment to remind that his Ísis Suébórum is Easter-Free, under the name *Idisiz, a synonym of *Frawjǭ.)

Italic:

1. Juppiter – 2. Márs – 3. Quirínus: Roman Major Flaminate.

1. Juppiter – 2. Márs – 3. Vofonius: Iguvine Grabovian gods.

Hellenic:

1. Héré – 2. Athéné – 3. Aphrodíté: Judgment of Paris.

This is the only version where the set is all feminine. The masculine complement would be 1. Zeus – 2. Héraclés – 3. Dioscouroi

Irano-Armenian:

1. Aramazd – 3. Anahit – 2. Vahagn: Edict of Tiridates against the Christians.

Aryan:

2. Indra – 1. Sauru (= San. Sarvá?) – 3. Naunghaithya (= San. Násatyá): daevas denounced in the Zorastrian Vendidad.

1. Mitrá-Varuná – 2. Indrá – 3. Násatyá: Rig Veda 10.125 as well as the treaty between Sattiwaza of Mitanni and Suppiluliuma of Hatti. Similar lists in other parts of the Rig Veda.

Interestingly, many of these listings are found in contexts where the Indo-Europeans were confronted with a monotheistic religion—Christianity or Zoroastrianism—and proclaimed the three as an epitome of their faith, and, when they fell, were demanded to renounce those same gods. The Mitanni attestation also suggests that, in a less mortal context, the question of “who are your gods?” was asked and the same standard answer was given.

III. Gods

1. First Function

The Wizard-King

The creator of the world, dividing Heaven & Earth. Third in a dynasty of three father-kings, third among three brother-kings. Alternately chaste & lustful to maintain the world. Dwells upon the Mountain, looking down at all the world. The god of Heaven, and husband of Earth. Father of gods & wers. A shape-shifting seducer. A serpent arising from the earth. Punishes the wicked. Goes among men as a wanderer, an ascetic. Prophecies with witches and mad women. Shoots men dead from afar. Unreliable, often malicious. The terror-god. Schemes for wars to be fought that heroes may be martyred into the Walhall; gives their bodies to the dogs & birds.

In the Mediterranean religions, *Dyḗws (Ph₂tḗr), viz. Heavenly Father is the main name; the same name is found in Sanskrit though in a far more marginal context and never quite clearly linked to Varuná or Rudrá.

Theodiscan: Woden (O.N. Óðinn)

Italic: Juppiter-Védiovis

Hellenic: Zeus, Hermés (avatar upon the earth)

Trojan: Apollón(?)

Irano-Armenian: Aramazd

Aryan: Varuná, Rudrá-Shivá

Sister & twin of the Wizard-King. Threefold like he. Like him a far-shooting slaughterer & a witch. A terror-gyden of death. Unwed & vicious.

The Witch-Queen

Theodiscan: Yeven (O.N. Gefjon)

Italic: Díána(?)

Hellenic & Trojan: Artemis-Hecaté

Aryan: Kálí, Chámundá...

The Queen of Heaven

The Heavenly Mother. The bride of the Heavenly Father, perhaps distinct from the Earthly Mother. Frequently quarrels with her groom. Attempts to thwart ascents to heaven by men. Presides over marriage, and her blissful union with the Father is the joy of the poets (Woden as he who dwells in Frie’s arms, the end of the first book of the Iliad, the lingam-yoni…)

Theodiscan: Frie-Scathe (O.N. Frigg-Skaði)

Italic: Júnó

Hellenic: Héré, Themis

Aryan: Párvatí

An eschatological god (perhaps not really belonging to the First Function) known only from two branches, noticed by Dumézil. The heir of the Heavenly Father. Shall destroy the ettins of the Windeld and renew the world. His central deed is his ride (on the horse the Wizard-King gave him), and his stride—Wider trampling down the jaw of the Fennerswolf, Vishnú’s three strides against Balí.

The Strider

Theodiscan: Wider (O.N. Víðarr)

Aryan: Vishnú

I do wonder if he might be found in Hellas somewhere, perhaps among the heroes.

2. Second Function

The Champion of the Gods

The son of Heaven & Earth, Thunder sent by the Father. Bringer of water. The only god strong enough to slay great ettins & worms. Rides in his chariot, red-bearded, casts forth the meteoric stone. Quarrels with the Father or Mother atimes. The friend of mankind, heavy-feasting & drinking. The holy keeper of the world.

Theodiscan: Thunder (O.N. Þórr)

Italic: Márs

Hellenic: Héraclés, Arés(?)

Irano-Armenian: Vahagn

Aryan: Indrá, Ganeshá(?)

Márs seems a bit strange here, I do wonder if he might be different war-god belonging to the second function (perhaps equal to the unidentifiable Thedish Tue). Nevertheless he is linked with Herculés as both are founder-gods of Rome (see book VIII of the Æneid).

As for Héraclés, one must remember that he was always worshipped as a god and understood as such, even while said to be a hero. Perhaps the tales of one of his avataric births took over his mythology? Moreover though, the Dioscouroi (see below) were also deemed both heroes and gods, but we know from other branches that they are gods.

The female god in this position is Athéné, whom indeed is often seen assisting Héraclés, alongside other heroes such as Achilleus, Odysseus, Diomédés &c. I cannot find her elsewhere save of course as Minerva in Italy, though I have seen Vác proposed as her Indian form.

3. Third Function

This function has what seem to be two different masculine gods, one worshipped by branches in the west, others by branches in the east.

The Captain of the People

The founding king, the defending king. Osirian. Dead & in the earth. Virile. Lord of golden fruitfulness, god of lust, seizing women. He seems to be have reenshrined & renamed at every thede’s burg, often with a name showing his nature as captain of the people, a name from their weaponish ethnonym. Seaxnéat from the seax of the Seaxan. Quirínus from the quirís of the Curés/Quirítés.

Theodiscan: Ing-Free, Sexneat (O.N. Yngvi-Freyr)

Italic: Quirínus, Vofonius

The Sons of Heaven

The twin sons of Heaven. Horsemen, sailors. Both dead, both everliving, one lives while the other dies. The saviors of mankind. Challenge the heavenly gods to win their cult.

Hellenic: Dioscouroi

Aryan: Násatyá/Ashviná

And then there are Founding Twins, who have the characteristics of both the above Third Function masculine gods together, but are rarely deemed gods. Among the Romans Romulus & Remus, Amphión & Zéthos among the Thebans. But these are especially common among the Theodiscans—Hengst & Horsa of the Anglo-Saxons, the Alcis of the Nahanarvali, Ybor & Agio of the Langobards, Alrekr & Eiríkr of the Yngling Swedes (called Freys afspring which I need not gloss)—I almost certainly forget some more. I am not completely sure where to place them, but they certainly deserve mention here.

Easter, the Lady Dawn

The Lady Dawn, and from this her Proto-Indo-European name can said with surety—H₂éwsōs. Born of Heaven & Sea. The golden, bejeweled princess of the east. The sister of the Sun & Moon, the Daughter of Heaven, and sister of the Sons of Heaven. Desired by the ettins for their victory along her siblings, denied to them by Heaven’s Thunder. The gyden of lust & delight. And no less the walkyrie as houri, helping the Father bring wars to wers and to harvest them up to the Folkwang, the fields of Paradise.

Among the Hellenes she appears as three overlapping characters—Éós as her cosmic character, Aphrodíté as her main cultic form, and Helené as her Spartan worship and the sister of the Dioscouroi. Nevertheless these all share like tripled roles in the Trojan War mythology, and share like origin myths (Aphrodíté born from Ouranos & the sea, Helené born from Zeus & Oceanos...)

Theodiscan: Easter-Free (O.E. Éastre, O.N. Freyja)

Italic: Auróra, Mater Mátúta

Hellenic & Trojan: Éós-Aphrodíté-Helené

Irano-Armenian: Anahit

Aryan: Ushás

Finis. Laus deis deabusque.

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Beni Döven Kocamı Alman Komşumla Boynuzladım! (Yasemin 35 Y., Bremen / Almanya)

Merhaba arkadaşlar, ben Yasemin, 35 yaşındayım, 17 yıllık evliyim ve Almanya'da yaşıyorum. Almanya'ya kocam getirdi beni. Kocam 39 yaşında, ismini vermek istemediğim tanınmış bir fabrikada işçi olarak çalışıyor. Benim hikayem karılarını döven erkeklere ders olsun. Evlendik evleneli kocam hep Maçodur. Dediği dedik, ondan iyi bilen olmaz tavırları ve hep benim diyen davranışlarıyla beni usandırmıştı. Fakat sikmeye geldi mi, canım gülüm der, işi bitince yine o Hanzo tipine bürünürdü.

En son beni hiç yere dövmüştü. Dövme sebebi de yemekti. Söylemesi ayıp, birgün önce Karnıyarık yapmıştım ve yarısı artmıştı, ben de israf olmasın diye, ertesi gün akşam yemeğinde pilavla salata yaptım ve kalan Karnıyarıkları da ısıttım. Kocam da, "Ne ulan bu? Her gün aynı yemeği getiriyorsun önüme! Akşama kadar evde götünü büyüteceğine, kocana doğru dürüst yemek yap, amına koduğumun Orospusu seni!" diye vurmuştu. Beni dövmesine değil de, bana "Orospu!" demesine çok üzülmüştüm ve "Ne Orospuluğumu gördün şimdiye kadar?" deyince, "Orospuya bak birde cevap veriyor!" deyip birtane daha vurmuştu.

Beni dövmesi ve bana "Orospu!" demesiyle o anda içimde bazı duyguları da öldürmüştü. İçimden, (Demek Orospu haa? Ben sana gösteririm Orospuluğu!) deyip sesimi kesmiştim. Bu olaydan sonra kocamla sadece o isteyince sikişiyordum. Beni hayvan gibi sikip, işi bitince de sırtını dönüp yatıyordu. Kocamın bana, "Orospu!" demesi çok ama çok kırmıştı beni.

Alt kattaki Alman komşum Walter beni her görüşünde elimde birşey varsa alır kapıma kadar getirirdi. Çok nazik bir erkekti. Bir sabah yine elimde poşetlerle Supermarkt'tan gelirken beni görüp elimden poşetleri aldı ve yukarı getirdi. Ben de, "Lütfen içeri girin, her dafasında yardım ediyosunuz, bir kahvemi için!" dedim. "Rahatsız etmeyeyim..." diye önce teklifimi geri çevirdi, ama ısrar edince girdi. Çocuklar okulda, kocam da işteydi. Kahveleri yaptım, karşıklıklı oturduk ve sigara içiyorduk. Alman komşum Walter gayet kibar birisi idi. Konuşurken birden, "Geçen gün kavga yaptınız herhalde, sesiniz aşağılara geldi." dedi. Kıpkırmızı olmuştum, "Evet, kocam beni dövdü!" dedim. Walter, "Neden Polis çağırmadın? Bu devirde kadın dövmek mi?" falan diye hayretle yüzüme bakıyordu. Benden cevap çıkmayınca, "Nasıl olur bu? Kocanı mı aldattın yoksa?" deyince, "Hayır, kocam Maço bir erkek!" dedim. Adam gülerek, "Evet, bence bu bütün Türk erkeklerinin sorunu!" deyip beni sakinleştirmeye ve teselli etmeye çalışıyordu.

Bense utandığımdan konuyu değiştirmeye çalışıyordum, "Sen neden evli değilsin?" deyince, Walter, "Kızarkadaşım var, ama evlilik istemiyoruz, serbest seksten yanayız, o istediği erkekle ben de istediğim kadınla birlikte olma özgürlüğüne sahibiz, birbirimizi kısıtlamıyoruz." dedi. Kahvelerimiz bitince, tazelemek için mutfağa gittim. Mutfakta (Neden Walterle sikişmiyorum ki?) diye düşünmeye başladım. Hem öküz kocam boynuz takmalıydı, kocamdan intikamımı Walterle sikişerek alacaktım. Kahveleri tazeleyip geri geldim. Walter yine gayet nazikçe teşekkür ederek kahvesini aldı. Ben bu sefer bacak bacak üstüne atıp, farkında değilmişim gibi eteğimin açılmasını sağladım. Walter bacaklarımdan gözünü alamıyordu. Başladı, "İnsan böyle güzel karısını döver mi?" falan diye...

Yavaşça yanına yaklaştım, kahve fincanını elinden alıp sehpaya koydum ve "Walter senden bir ricam var!" dedim. "Lütfen buyurun!" deyince, "Beni sikmeni istiyorum, hemde şimdi!" dedim. Adam şaşkın şaşkın bakıyordu sadece. "Lütfen beni sik!" dedim ve dudaklarından öpmeye başladım. Şaşkınlığını atan Walter bana karşılık vermeye ve beni soymaya başladı. Öyle nazikti ki, elbisemin her çıkardığı parçasını güzelce yere bırakıyor ve soyduğu yerleri öpüp yalıyordu. Birkaç dakika sonra tamamen çıplak kalmıştım. Walteri elinden tutup yatakodasına götürdüm. İstiyordum ki kocama boynuzu kocamın kendi yatağında taksın. Beni yatağa uzatıp kendisi de soyundu ve amımı yalamaya başaldı. Öyle güzel yalıyordu ki amımı, kendimden geçiyordum. Derken dudaklarını ve dilini götümde hissetmiştim. Öküz kocam birkere bile öpmemişti götümü. İyice azmıştım, artık, "Bitte Fick Mich!" diye inliyordum...

Walter beni üzerine aldığı gibi 69 yapmış ve sikini ağzıma vermişti. Siki ben yaladıkça büyüyordu. Kocamın siki kadar vardı büyüklüğü. Amım ve götüm yalanırken defalarca Orgazm olmuştum, sırıl sıklam olmuş amım yanıyordu. "Ne olur sok artık!" diye üzerinden indim ve domaldım Walterin önüne. Yavaşça sikini amıma soktu ve belimden tutup gidip gelmeye başladı. Tam karşımda kocamla ikimizin düğün resmi vardı, gözüm oraya takılınca sanki kocam görüyormuş gibi hırsla ve zevkle sikişmeye başladım. Walter de bana ayak uydurup hızlanıyor, hızlandıkça da yatak ileri geri sallanıyordu. Walter kocamın sikmediği gibi çok ustaca sikiyordu beni, içimde hızlanıyor, birden yavaşlayıp, sonra birden hepsini köklüyordu. Walter beni altına alıp sikmeye başladığında ise artık iyice delirmiştim. Kocamdan daha iyi sikiyordu, en önemlisi kocam şimdiye kadar çoktan boşalmıştı. Ve ben şimdiye kadar almadığım zevki ve tadı alıyordum. Amıma pompalarken memelerimi yalıyor, boynumu hafif hafif ısırıyordu. Adamın altında delirmiş gibi inliyordum...

Beni yarım saate yakın siktiğinde ikimiz de yorulmuş ve terden sırılsıklam olmuştuk. Öyle güzel sikiyordu ki, şimdiye kadar siktirmediğime pişman oldum. Sonra birden, "Jasmin geliyorum!" dedi (Yasemin diyemediği için bana hep Jasmin der). Ben de, "Lütfen içime boşal, çıkma içimden!" dedim. Son bir kez bana kenetlendi ve kendinden geçmiş bir vaziyette içime boşaldı. Önce hiç konuşmadık, dakikalarca beni okşadı, öptü. Siki amımın içinde küçülünce kalktı ve "Artık gideyim!" dedi. Ben de, "Gitmeden senden bir ricam olacak, lütfen kimseye birşey söyleme, biliyorsun ben evliyim ve evli kalmak istiyorum. Bu kocamdan intikam içindi!" dedim. Walter de eğilip beni birdaha öptü ve "OK!" deyip gitti.

Ben de kalktım ama banyo yapmadım, Alman komşumun dölleriyle dolu amımı kocama yalatıp siktirecektim. Yaptım da! Bu da üstüne kapak oldu! Karılarını döven erkeklere ders olsun!

[Yasemin]

95 notes

·

View notes

Text

A megaboard (?) based on all 14 contestants of the 1942 Festival of Termina-- one gif each

x x x

x x x

x x x

x x x

x x x

Banner

They are in alphabetical order:

Abella: A mechanic from the northern capital Oldegård. She is part of an underground rebel organization.

August: A mysterious elderly gentleman from the northern capital of Oldegård. He seems to know a lot of the situation at hand...

Caligura: A ruthless mobster from the Vatican City. His cruel ways and his ghoulish appearance earned him the nickname "Count Dragul" among his peers.

Daan: A doctor with an unorthodox background including several years on the frontlines.

Henryk: A chef from the Kingdom of Rondon. Adamant about keeping his life secret. It's another thing whether there really is anything interesting to hide or not...

Karin: A war correspondent/journalist who has seen the worst The Second Great War has had to offer.

Levi: A former child soldier with a lot of experience in modern warfare despite his young age.

Marcoh: A small-time thug from the Vatican City/An aspiring amateur boxer struggling to stay on the lawful path.

Marina: An occultist apprentice returning home from her studies in the Vatican City.

O'saa: A mysterious yellow mage hailing originally from the land of Abyssonia.

Olivia: A botanist returning to Prehevil for her sister.

Pav: A lieutenant of the Bremen army. He has quickly risen in ranks and clearly he has a goal of his own that goes beyond army matters.

Samarie: A dark priest apprentice from the Vatican City. Doesn't tell much about her life beyond that...

Tanaka: A businessman who has travelled from far east all the way to the Europa to take an advantage of the political turmoil, all in the name of his family business.

(via the wiki)

#f&h#f&h termina#f&h2#fear and hunger#festival of termina#fnh#fnh2#funger#funger termina#stim#content: stimboard#cw: clusters#cw: food#//#abella#August#caligura#daan von dutch#henryk klimkov#karin sauer#Levi#marcoh#marina domek#o'saa#olivia haas#pavel yudin#samarie#tanaka

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

A few elements of interest concerning the temple at Uppsala

Yngvi-Freyr constructs the Temple at Uppsala (1830) by Hugo Hamilton

Chapter 26: “Now we shall say a few words about the superstitions of the Swedes. That folk has a very famous temple [134] called Uppsala, situated not far from the city of Sigtuna and Björkö. In this temple, [135] entirely decked out in gold, the people worship the statues of three gods in such wise that the mightiest of them, Thor, occupies a throne in the middle of the chamber; Wotan [Odin] and Frikko [Freyr] have places on either side. The significance of these gods is as follows: Thor, they say, presides over the air, which governs the thunder and lightning, the winds and rains, fair weather and crops. The other, Wotan -that is, the Furious–carries on war and imparts to man strength against his enemies. The third is Frikko, who bestows peace and pleasure on mortals. His likeness, too, they fashion with an immense phallus. But Wotan they chisel armed, as our people are wont to represent Mars. Thor with his scepter apparently resembles Jove. The people also worship heroes made gods, whom they endow with immortality because of their remarkable exploits, as one reads in the Vita of Saint Ansgar they did in the case of King Eric.”

Scholium note 134: “Near this temple stands a very large tree with wide-spreading branches, always green winter and summer. What kind it is nobody knows.”

Scholium note 135: “A golden chain goes round the temple. It hangs over the gable of the building and sends its glitter far off to those who approach, because the shrine stands on level ground with mountains all about it like a theater.”

Chapter 27: “For all their gods there are appointed priests to offer sacrifices for the people. If plague and famine threaten, a libation is poured to the idol Thor; if war, to Wotan; if marriages are to be celebrated, to Frikko. It is customary also to solemnize in Uppsala, at nine-year intervals, a general feast of all the provinces of Sweden. From attendance at this festival no one is exempted Kings and people all and singly send their gifts to Uppsala and, what is more distressing than any kind of punishment, those who have already adopted Christianity redeem themselves through these ceremonies.”

Selected excerpts from Adam of Bremen’s late 11th century work Gesta Hammaburgensis ecclesiae pontificum (“Deeds of the Bishops of Hamburg”)

40 notes

·

View notes

Note

So interesting how as a croatian I grew up hearing about Svarožić due to a childrens books author, then grew up believing he was an actual slavic deity that everyone knew about. Only now to see that there's only one actual source about him :/

Oh well, in my heart he is as big as Perun

Actually Svarožic is an exceptionally well attested Slavic god! There is only one mention of Svarog.

And Svarožic was very big! His cult center in Radogošč (Redigast) was very famous and very well respected among the Polabians. It was the political and religious center for the Lutician federation! Slavs from other tribes would go on pilgrimages to Radogošč temple to consult the oracle and leave offerings. According to Adam of Bremen because of how ancient the town was and how famous the temple was the Redarii began to view themselves as particularly important among Slavic peoples and wanted to rule supreme among them.

Adam of Bremen, Helmold and Thietmar mention Svarožic being „most important among the gods in the temple” and Thietmar calls him „especially worshipped by all pagans”. And clearly he was also well known among the Eastern Slavs because we have a bunch of different sermons in East Old Church Slavonic raging against people that make sacrifices to him!

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bremen Mızıkacı kitabında bir tane yamuk adam var o da horoz, diğeri aslan gibi çocuklar

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Meine Top 10 Tatorte 2023

1. Tatort Berlin - Das Opfer (einfach nur wow ! dieser Tatort tat das was Tatort Saarbrücken bisher noch nicht konnte, endlich mal ne Komissar-Gay-Love-Story) , stimmt immernoch auch im 2023

2. Tatort Berlin - Tiere der Grossstadt (weil das Thema, die Rache so gut umgesetzt wurde + Roboter)

3. Tatort Luzern - Ihr werdet gerichtet (Selbstjustiz auf einem andere Level und endlich mal action)

4. Tatort Saarbrücken - Die Kälte der Erde (Queerbaiting af aber ich ess es jedes mal auf)

5. Tatort Dortmund - Liebe mich! (das Ende = Trauma)

6. Tatort Dortmund - Love is Pain (Das Thema, die Liebe als Schmerzverursacher Nr. 1 war top umgesetzt und auch das man alles für die Liebe macht fand ich sehr spannend)

7. Tatort Kiel - Borowski und der gute Mensch (Kai Korthals ist einer der besten Tatort Villains ever! Bis ich gecheckt hatte das er Ihre Haare trägt auf dem Fahrrad, exploding brain emoji)

8. Tatort Zürich - Blinder Fleck (Drohnen, Jugoslawienkrieg, endlich hat sich der Tatort mal schweizerisch relevanten Themen gestellt)

9. Tatort Luzern - Friss oder stirb (immer noch wegen der Musik und weil ich Kammerspiele liebe, werde die Szene als Paint it Black spielte nie mehr vergessen, die Musik macht dass diese Geschichte mir so ins Gedächnis gebrannt wurde)

10. Tatort Saarbrücken - Herz der Schlange

Ende Jahr (2023) muss ich sagen, dass ich nicht mehr so strikte lieblings Komissare habe. Ich habe dieses Jahr auch endlich den Dortmunder Tatort gesehen und finde Bönisch, Pawlak, Herzog und manchmal auch Faber top. Saarbrücken ist aber nach wie vor weit oben und Karow auch noch, jedoch kann ich nichts mit der neuen, Bonard, anfangen tbh. Grandjean im letzten Zürcher fand ich so spannend und man erfährt endlich den Beziehungsstatus mit ihr und diesem Typen. Zudem geht mir seit ich den ersten Bremer Fall mit den neuen Kommissaren gesehen habe, diese Zugverbindung von Bremen nach Kopenhagen nicht mehr aus dem Kopf und wie er einen Zug nach dem anderen verpasste. Für nächstes Jahr habe ich aber wenig Hoffnung, denn Tatort Saarbrücken ist und bleibt ein Queerbait, Pawlak verlässt Dortmund und Berlin ist langweilig und Zürich ist eher miss als Hit.

Aber die Hoffnung stirbt zuletzt oder?

Meine Top Tatort Komissare:

Jan Pawlak

Martina Bönisch

Rosa Herzog

Robert Karow

Adam Schürk

Leo Hölzer

Pia Heinrich

Esther Baumann

Isabelle Grandjean

#Tatort#tatort zürich#tatort saarbrücken#tatort berlin#tatort dortmund#robert karow#adam schürk#leo hölzer#rosa herzog#jan pawlak#herzlak#leo & adam#wieso tue ich mir das an#ach was wär das Leben ohne copaganda#tatort

17 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi! I really loved a post you made earlier about how society is only now returning to a variety of religious beliefs and was wondering if you could talk more about it. Any thoughts on countries taking up their original religions? Magnus and asatru? Rhys or his siblings with druidism?

TW discussions of religion, religious skepticism and fictional depictions of religion in historical fantasy.

I feel like they pick up things they themselves remember but the modern human iteration is... Meh. No shade to believers, I did some time with the Nordic pantheon before the Nazis took it over but the modern iterations of almost all European pre-Christian religions are unfortunately mostly constructed between the 18th and 20th centuries. Almost none of it dates back further than revivals during the enlightenment. Would they see echoes of their lived experience in these revivals? Sure. I just don't know if they'd be adherents to the modern form when they can remember at least some of the real thing, otherwise now dead and gone. So I do think there's things in them that survive but they can't quite look at modern paganism as a belief system.

But two parts I think would really feel important to them: a lot of the pagan revivals are about a rejection of the Calvinist themes of Reformation and counter-reformation Christianity that emphasize individuality, created the belief of the elect who are saved by god and stripped Christianity of a lot of its older emphasis on community and mutual aid and responsibility. I think a lot of the pagan revivalism would very much appeal there and in its counter-culture themes.

And second, because I'm a weirdo who uses hetalia to get into really niche topics and practice writing historical fiction I want to publish when I'm grown, I try to stick to what we actually know. I want to replicate the perspectives of history. The fantastical aspects are often just adaptations of what magic was actually believed in, as far as I can adapt from a very limited pool of knowledge. I have written Alasdair carving the symbols we have from some Pictish standing stones and Ogham, a Gaelic form of literacy into objects and sacred trees to make them into portals and protective objects. I have written Arthur's primary contact with their mother as being not when he visits the site of her barrow and the Kirk that gives them their name that was later built on he same site, but after he drowns or is caught in a storm, because we know the Britons of prehistory and the Roman era and even into the early medieval believed water was a kind of portal between this world and the sacred. I gave Rhys their mother's bronze age sword because magic swords are everywhere in every flavor of Celtic Mythology. Arthur keeps Cromwell's head on the mantel partially because he's a stubborn fuck who can hold a grudge for centuries but also because we know that the ancient Celts believed the head specifically to be a very powerful magical object.

Norse paganism as we know it today is based on things like the Icelandic Sagas and the descriptions of the temple of Uppsala by Adam of Bremen. Those are fantastic documents but they only come into being centuries after the end of the Viking age and are written by Christians, usually clerics, and usually men. Our heads are full of images of powerful priestesses, shield maidens and goddesses, but more than a third of human women were starved as children compared to under ten percent of boys. Every Norse grave is different, with only general categories being able to be sussed put based on grave goods, the style of inhumation or cremation and marking ships or stones. We just don't know fuck all about the specifics what the people of this era really believed.

Or with the British celts. We know what the Romans said. That they burned criminals in wicker men, committed human sacrifice, that the Romans slaughtered the druids on Anglesey in Wales. We know the names of their gods when they are twinned with Roman ones or archaeologists find inscriptions. But so many of them are only known by one or two inscriptions. There are only eight for Brigantia and she was the patron goddess for the largest tribe by territory in Iron Age Britain. We know they offered sacrifices of value to bodies of water, we know from medieval Irish sources, also written by Christians, that they had 4 holidays aligning with the seasons and divided the year into half light half dark. But we don't know shit about songs or prayers or even how much the Romans made the fuck up. Which was likely most of it but we'll never know. What the Picts in Scotland may have believed is especially lost, we don't even have most of their language or even sheep counting like Cumbrian.

There's been a lot of push back against terms prehistory and dark ages and rightly so in that they conjure images of a filthy past, people living in their own shit and grim misery. But on a historical level, on an archival level, there really are such things as dark ages and prehistory where we just do not know the details and when discussing and writing religion I err towards what we know the most about, especially where archaeology and history can support each other.

#the ask box || probis pateo#meatsack mechanics || the sociology and biology of nations#today on: I use hetalia to figure out how I want to write historical fiction when I grow up lmao

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Skåne är den vackraste provinsen i Danmark" ~Adam av Bremen

heh

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

IF YOU KILL A SNAKE - THE SUN WILL CRY

Baltic culture is frequently described as extremely conservative and dedicated to tradition. This is not mere romantic and historical data. For the conservative aspects of the Baltic languages one need look no further than A. Meillet who wrote that: "Le lituanien est remarquable par quelque traits qui donnent une impression d'antiquite indo-europeenne; on y trouve encore au XVIe siecle et jusqu'aujourd'hui des formes qui recouvrent exactement des formes vediques ou homeriques..." (Meillet 1964:73). Secondly, the Baltic peoples (who at one time comprised several related tribes that are now extinct, eg. the Old Prussians) were the last Europeans to adopt Christianity. The new religion was introduced into Latvia and Prussia at the beginning of the thirteenth century by the Knights of the Teutonic Order. The Lithuanians resisted the longest and officially only joined the Christian Church in 1387 through Poland. The new faith, however, was introduced in a foreign language (Polish) and was not understood by the Baltic villagers who remained pagan.

The merger of these two religions commenced in the sixteenth century and continued for three hundred years, the Christian missionaries never entirely destroying the old religion. The final product was a syncretistic religion with only a veneer of Christianity over a surviving core of pagan belief. In this way, the Baits clearly distinguish themselves from their Slavic and Germanic neighbors who accepted Christianity at a much earlier date (the Slavs ca. tenth century, the Germans in the ninth century). As a result, these latter peoples are farther removed from their pagan past and although various folk-beliefs and customs may still exist as "remnants" of their ancient religion, their initial meaning and intent has since become quite obscured. Scholars may sometimes reconstruct plausible explanations for pagan survivals in Germanic and Slavic folk-belief, but the "folk" as such are usually quite unaware and unconcerned about them. In contrast, Baltic peasants in the early twentieth century could often explicate their own folk customs and beliefs in the same manner as their pagan ancestors did several hundred years ago.

A particularly fine example of such long-term persistence of belief from the pagan era to the present is the Balts' attitude towards the snake, a major figure of tale-type 425 M with which this study is concerned.

THE SNAKE

Chronicles, travelogues, ecclesiastical correspondence and other historical records written by foreigners often made mention of snake worship among the Old Prussians, Samogitians, Lithuanians, and Latvians. The snakes were frequently referred to as žalčiai (cognate with Žalias 'green') which has been identified as the non-poisonous Tropodonotus natrix. Sometimes the chronicles also referred to them as gyvatės, a word which is clearly associated with Lith. gyvata 'vitality' and gyvas 'living'. The following historical records should more than suffice to demonstrate that snakes were worshipped widely among the Balts.6

In the eleventh century, Adam of Bremen wrote that the Lithuanians worshipped dragons and flying serpents to whom they even offered human sacrifices (Balys 1948:66).

Aeneas Silvius recorded in 1390 an account given him by the missionary Jerome of Prague who worked among the Lithuanians in the final decade of the fourteenth century. Jerome related that

The first Lithuanians whom I visited were snake worshippers. Every male head of the family kept a snake in the corner of the house to which they would offer food and when it was lying on the hay, they would pray by it.

Jerome issued a decree that all such snakes should be killed and burnt in the public market place. Among the snakes there was one which was much larger that all the others and despite repeated efforts, they were unable to put an end to its life (Balys 1948:66; Korsakas, et al 1963:33).

Dlugosz at the end of the fifteenth century wrote that among the eastern Lithuanians there were special deities in the forms of snakes and it was believed that these snakes were penates Dii (God's messengers). He also recorded that the western Lithuanians worshipped both the gyvatės and žalčiai (Gimbutas 1958:35).

Erasmus Stella in his Antiquitates Borussicae (1518) wrote about the first Old Prussian king, Vidvutas Alanas. Erasmus related that the king was greatly concerned with religion and invited priests from the Sūduviai (another Baltic tribe), who, greatly influenced by their stupid beliefs, taught the Prussians how to worship snakes: for they are loved by the gods and are their messengers. They (the Prussians) fed them in their homes and made offerings to them as household deities (Balys 1948: II 67).

Simon Grunau in 1521 wrote that in honor of the god Patrimpas, a snake was kept in a large vessel covered with a sheaf of hay and that girls would feed it milk (Welsford 1958:421).

works: Balys 1948:66-74; Elisonas 1931:81-90; Gimbutas 1958: 32-35; Korsakas et al 1963:22-24; and Welsford 1958:420-422.

Maletius observed ca. 1550 that...

The Lithuanians and Samogitians kept snakes under their beds or in the corner of their houses where the table usually stood. They worship the snakes as if they were divine beings. At certain times they would invite the snakes to come to the table. The snakes would crawl up on the linen-covered table, taste some food, and then crawl back to their holes. When the snakes crawled away, the people with great joy would first eat from the dish which the snakes had first tasted, believing that the next year would be fortunate. On the other hand, if the snakes did not come to the table when invited or if they did not taste the food, this meant that great misfortune would befall them in the coming year (Balys 1948:67).

In 1557 Zigismund Herberstein wrote about his journey through northwestern Lithuania (Moscovica 1557, Vienna):

Even today one can find many pagan beliefs held by these people, some of whom worship fire, others — trees, and others the sun and the moon. Still others keep their gods at home and these are serpents about three feet long... They have a special time when they feed their gods. In the middle of the house they place some milk and then kneel down on benches. Then the serpents crawl out and hiss at the people engaged geese and the people pray to them with great respect. If some mishap befalls them, they blame themselves for not properly feeding their gods (Balys 1948: II 67).

Strykovsky in his 1582 chronicle on the Old Prussians related:

They have erected to the god Patrimpas a statue and they honor him by taking care of a live snake to whom they feed milk so that it would remain content (Korsakas et. al 1963:23).

A Jesuit missionary's report of 1583 reported:

.. .when we felled their sacred oaks and killed their holy snakes with which the parents and the children had lived together since the cradle, then the pagans would cry that we are defaming their deities, that their gods of the trees, caves, fields, and orchards are destroyed (Balys 1948: 11,68).

In 1604 another Jesuit missionary remarked:

The people have reached such a stage of madness that they believe that deity exists in reptiles. Therefore, they carefully safeguard them, lest someone injure the serpents kept inside their homes. Superstitiously they believe that harm would come to them should anyone show disrespect to these serpents. It sometimes happens that snakes are encountered sucking milk from cows. Some of us occasionally have tried to pull one off, but invariably the farmer would plead in vain to dissuade us... When pleading failed, the man would seize the reptile with his hands and run away to hide it (Gimbutas 1958:33).

In his De Dies Samagitarum of 1615, Johan Lasicci wrote:

Also, just like some household deities, they feed black-colored reptiles which they call gioutos. When these snakes crawl out from the corners of the house and slither up to the food, everyone observes them with fear and respect. If some mishap befalls anyone who worship such reptiles, they explain that they did not treat them properly (Lasickis 1969:25).

Andrius Cellarius in his Descripto Regni Polonicae (1659) observed:

although the Samogitians were christianized in 1386, to this very day they are not free from their paganism, for even now they keep tamed snakes in their houses and show great respect for them, calling them Givoites (Balys 1948: II 70).

T. Arnkiel wrote that ca. 1675 while traveling in Latvia he saw an enormous number of snakes.

die night allein auf dem Felde und im Walde, sondern auch in den Häusern, ja gar in den Betten sich eingefunden, so ich mannigmahl mit Schrecken angesehen. Diese Schlangen thun selten Schaden, wie denn auch niemand unter den Bauern ihren Schaden zufügen wird. Scheint, dass bey denselben die alte Abgötterey noch nicht gäntzlich verloschen (Biezais 1955: 33).

The Balts' positive attitude towards the snake has been recorded also in the late nineteenth century in the Deliciae Prussicae (1871) of Matthaus Pratorius who observed: "Die Begegnung einer Schlange ist den Zamatien und preussischen Littauern noch jetziger Zeit ein gutes Omen (Elisonas 1931:8.3).

Aside from the widespread attestation of snake-worship among the Baits and its persistence into Christian times, these historical records also suggest an intriguing relationship between Baltic mythology and our folk tale. Both Simon Grunau (1521) and Strykovsky (1582) mention the worship of the snake in close reference to the god Patrimpas. This deity is commonly identified as the "God of Waters" and his name is cognate with Old Prussian trumpa 'river'. The close association between the snake and the "God of Waters" has prompted E. Welsford to suggest a slight possibility that the water deity Patrimpas was at one time worshipped in the form of a snake (Welsford 1958:421). A serpent divinity associated with the water finds numerous parallels among Indo-European peoples, eg. the Indie Vrtra who withholds the waters and his benevolent counterpart, the Ahibudhnya 'the serpent of the deep'; the Midgard serpent of Norse mythology; Poseidon's serpents who are sent out of the sea to slay Lacoon, etc. A detailed comparison of the IE water-snake figure would far exceed the limits of this paper, nevertheless, it is curious to note that except for the quite minor Ahibudhnya, most IE mythologies present the water-serpent as malevolent creature — an attitude quite at variance with that of the ancient Balts.

From the historical records it is difficult to determine to what extent the ancient Balts might actually have possessed an organized snake-cult. Erasmus Stella's account of 1518 concerning the Sudovian Priest's introduction of snake-worship into Prussia might suggest such an established cult. In any event, that the snake was worshipped widely on a domestic level cannot be denied. In general it was deemed fortunate to come across a žaltys, and encountering a snake prophesied either marriage or birth. The žaltys was always said to bring happiness and prosperity, ensuring the fertility of the soil and the increase of the family. Up until the twentieth century, in many parts of Lithuania, farm women would leave milk in shallow pans in their yards for the žalčiai. This, they explained, helped to ensure the well-being of the family.

In 1924 H. Bertuleit wrote that the Samogitian peasants "even at the present time, staunchly maintain that the žaltys/gyvatė is a health and strength giving being" (Balys 1948: II 73). To this day in Lithuania, the gabled roofs are occasionally topped with serpent-shaped carvings in order to protect the household from evil powers.

The best proof of the still persistent respect, if no longer veneration, of the snake (or žaltys in specific) is provided by various folk sayings and beliefs which were recorded during this century. Some of them clearly reflect the association of the snake with good luck, while others depict the evil consequences which will befall one if he does not respect the snake. The following are some examples:7

Good luck

1. If a snake crosses over your path you will have good luck.

2. If a snake runs across your path, there will be good fortune.

3. Žaltys is a good guardian of the home, he protects the home from thunder, sickness and murder.

4. If a žaltys appears in the living room, someone in that house will soon get married.

Bad consequences

5. In some houses there live domestic snakes; one must never kill this house-snake, for if you do, misfortunes and bad luck will fall on you and will last for seven years.

6. If you burn a snake in a fire and look at it when it is burning, you will become blind.

7. If you find a snake and throw it on an ant hill, it will stick out its little legs which will cause you to go blind.

8. If s snake bites someone and the person then kills the snake, he will never get well.

9. If a snake bites a man and another person kills it, the man will never recover.

10. If you kill the snake that bit you, you will never recover.

11. If a žaltys comes when one is eating, one must give it food, otherwise one will choke.

12. When children are eating and a žaltys crawls up to them, he must be fed; otherwise the children will choke.

13. If you kill a žaltys, your own animals will never obey you.

14. If someone kills a snake, it will not die until the sun has set.

15. If you kill a snake, the sun cries.

16. If you kill a snake and leave it unburied, the sun grows sick.

17. When a snake or a žaltys is killed, the sun cries while the Devil laughs.

18. If you kill a snake and leave it in the forest, then the sun grows dim for two or three days.

19. If you kill a snake and leave it unburied, then the sun will cry when it sees such a horrible thing.

20. If you kill a snake, you must bury it, otherwise the sun will cry when it sees the dead snake.

The snake's name.

21. If one finds a snake in the forest and wants to show it to others, he must say: "Come, here I found a paukštyte (little bird)!", otherwise, if you call it a gyvate, the snake will understand its name and run away.

22. If you see a snake, call it a little bird; then it will not attack humans.

23. While eating, never talk about a snake or you will meet it when going through the forest.

24. Snakes never bite those who do not mention their name in vain, especially while eating and on the days of the Blessed Mary (Wednesdays and Sundays).

25. On seeing a snake you should say: "Pretty little swallow." It likes this name and does not get angry nor bite.

26. If someone guesses the names of a snake's children, the snake and its children will die.

27. If you do not want a snake to bite you when you are walking though the forest, then don't mention its name.

28. A snake does not run away from -those who know its name.

29. Whoever knows the name of the king of the snakes will never be bitten by them.

30. One must never directly address a snake as gyvatė (snake); instead, one should use ilgoji (the long one) or margoji (the dappled one).

Snakes and cows.

31. Every cow has her own žaltys and when the žaltys becomes lost, she gives less milk. When buying a cow, a žaltys should also be bought together.

32. If you kill a žaltys, things will go bad because other žalčiai will suck all the milk from the cows.

Life-index and affinity to man

33. Some people keep a žaltys in the corner of their house and say: if I didn't have that žaltys, I would die.

34. If a person takes a žaltys out of the house — that person will also have to leave home.

35. If a žaltys leaves the house, someone in that household will die.

Enticement.

36. When you see a snake crawl into a tree trunk, cross two branches and carry them around the tree stump. Then place the crossed branches on the hole through which the snake crawled in. When the sun rises, you will find the snake lying on these branches.

37. When you see a snake and it crawls into a tree-stump, take a stick and draw a circle around the stump. Then, break the stick and place it in the shape of a cross and the snake will crawl out and lie down on the cross.

Miscellaneous.

38. If a snake bites you, pick it up in your hands and rub its head against the wound. Then you will get well.

39. When one is bitten by a snake, say: "Iron one! Cold-tailed one! Forgive (name of person bitten)," while blowing in the direction of the sick person.

40. If you throw a dead snake into water, it will come back to life.

41. A snake attacks a man only when it sees his shadow.

42. They say that when a snake is killed, it comes back to life on the ninth day.

43. If a snake bites an ash tree, the tree bursts into leaf.8

44. If someone understands the language of the snakes, whey will obey him and he can command them to go from one place to another.

45. If there are too many snakes and you want them to leave, light a holy fire at the edge of your field and in the center; all the snakes will then crawl in groups through the fire and go away, but you must not touch them.

Some folk-beliefs show an obvious Christian influence and are possibly the products of frustrated Jesuit anti-snake propagandists:

45. When you meet a snake you must certainly have to kill it for if you fail to do so, then you will have committed a great sin.

46. If you kill a snake, you will win many indulgences.

47. If you kill seven snakes, all your sins will be forgiven.

48. If you kill seven snakes, you will win the Kingdom of Heaven

Such examples as these, however, are quite rare in comparison to the folk-beliefs which are sympathetic to the snake.

Considering the evidence amassed from both historical records and folk-belief that the Balts possessed a positive and reverent attitude towards the snake, it is little wonder that the snake husband's death is viewed as tragedy. If, as the proverbs suggest, a snake's death can affect the sun, then what consequences might the death of the very King of the Snakes have among mortals? This tragic outcome, as Swahn has indicated, gives the tale a character which is foreign to the true folk-tale (Swahn 1955:341). This tale could not terminate on the usual euphoric note typical of the Märchen (although the tale does contain numerous Märchen motifs) because the main event of the story relates to a "reality" which the people who tell the story still hold to be true. The tale is thus well-nourished in a setting where such folk-beliefs about the snake persist. On the other hand, the tale itself may have played a part in affecting the longevity of the beliefs. Whichever case may be true, it is obvious that both are closely related.

A specific element of folk-belief that survived as an ideological support to the tale is that of the snake's name-taboo. The tragic killing of the snake king is implemented only because the name formula is revealed. Thus, the general snake-taboo proverbs (No. 21-30; receive a specific denouement in the snake-father ordering that his name and summoning formula not be revealed to others. There appear to be two important aspects that surround this name-taboo. First of all, it reflects the primitive concept of one being able to manipulate another when his name is known. A second aspect is that the name-taboo may rest on the reverence and fear of a more powerful supernatural being that requires mortals never to mention the deity's real name. For example, Perkūnas, the all-powerful Thunder God of the Balts, has many substitutes for his real name which are usually onomatopoeic with the sound of thunder, eg. Dudulis, Dundulis, Tarškulis, Trenktinis. In our tale the general reason for the name-taboo may be partially related to this second explanation especially since there are a number of variants for the name of the snake-king, eg. Žilvine, which have no etymological support but bear a suspicious resemblance to the word žaltys 'snake'. This might then indicate a deliberate attempt to destroy the name žaltys in such a way as to avoid breaking the name-taboo but still retain some of the underlying semantic force. On the other hand, it must be admitted that many of the summoning formulas include a direct reference to the husband as žaltys. In these cases, since the brothers know his name, they can extend their power over him. It is likely that both these aspects should be considered when explaining the name-taboo of the story. The clear distinction between the obviously Christian folk-sayings (No. 45-48) and the underlying pro-snake proverbs carries considerable significance when one views the substitution of the Devil for the snake in many of the Latvian variants. This substitution occurred in all probability with the increasing influence of Christianity and its usual association of the serpent with the Devil as in the Garden of Eden story. It is interesting to reflect that in some cases the entire story proceeds with the same tragic development despite this substitution (Lat. 2, 7, 9, 15). Even in the Lithuanian variant (Lith. 4) where an old woman tells the heroine that her snake-husband is actually the Devil, this does little to alter the tragic tone of the tale's ending. Thus, it would seem that the Devil is a relatively late introduction, sometimes amounting to little more than a Christian gloss of the snake's real identity. On this basis, one might well conelude that the tale must have been composed in pagan times and is thereby, at the very least, four or five centuries old if not far older.

The effect of the diabolization of the snake among the Latvian variants seems to have led to a disintegration of the tale's actual structure. In some of the Latvian redactions (Lat. 4, 8, 15) where the Devil is the abductor, the story simply ends with the killing of the supernatural husband and the heroine's rescue. In variants of the tale which progress with such a rescue-motif development, it is important to observe that many of the other elements are consequently dropped. There is no name-taboo or magic formula, sometimes no children, and, of course, no magical transformation. Thus the tale is stripped of all these other embellishments and appears rather bare. It simply relates an abduction of the heroine and her rescue, usually accomplished by some members of her family or a priest and thunder storm (Latv. 15). In any event, the abductor is one whom she quite definitely cannot marry and therefore, there can be no Märchen marriage-feast. When the tale has been altered, the rescue motif can then be correlated to the other Märchen tale-types where the heroine is abducted (rather than married) and is eventually rescued by an eligible marriage partner. One might even speculate that this will be the eventual fate of those particular Latvian variants which no longer specify that the snake, a sacred and positive being, is the supernatural husband. We then have an intimate relationship between folk-belief and folk-tale which ultimately may be mirrored in the very structure of the story.

The place of the snake in Baltic folk-belief and its relation to our tale now having been well established, the obvious next question is whether similar beliefs exist in the neighboring non-Baltic countries and, if not, might we propose this as a possible explanation why the story as a Baltic oicotype has not spread to these other cultures. A complete analysis of the role of the snake in Germanic and Slavic folk-belief would far exceed the time allotted for the composition of this study, nevertheless, some of the evidence arrived at by way of a cursory review should be brought forth.

Of sole interest in our investigation of snake beliefs among the Germans and Slavs is the extent to which these cultures parallel the Balts with respect to the lat-ter's quite sympathetic attitude toward the snake. Bolte and Polivka, Hoffmann - Krayer and J. Grimm all mention that among the Germans there are some beliefs which view the snake in a positive light. A few specific entries in Handwörterbuch des deutschen Aberglaubens are similar to some folk-beliefs already cited among the Balts (Hoffmann - Krayer 1935-36: VII 1139-1141). Bolte and Polivka in listing parallels to Grimm's Märchen von der Unke cite several instances of snakes bringing great fortune to those who treat them well and disaster to those who disrespect or abuse them (Bolte and Polivka 1915: II 459-465) .9 Both Hoffmann-Krayer and Grimm, after listing various "remnants" of what they maintain might be evidence for an ancient snake-cult in Germany, state that under the influence of Christianity the snake is usually diabolized and its image as a malignant and deceitful creature predominates. Only in some very "old" stories are there traces of the original heathen positive attitude towards the snake (Grimm 1966: II 684); Hoffmann - Krayer 1935-36: VII Sp. 1139).

Welsford, in writings about the snake-cult among the ancient Slavs, states that it was probably quite similar to the one which persisted among the Baits, but that the latter seems to have retained it much longer. In the Slavic countries the snake was usually regarded as a creature in which dead souls were embodied and through time came to be viewed mostly as a dangerous animal. It is this aspect of the snake which appears most often in Slavic stories. The snake seems to be similar or even identical with other evil antagonists such as Baba Yaga (Welsford 1958: 422). There are also many stories involving a hero or heroine who has been transformed into a snake by evil enchantment.10 These stories primarily relate how this "curse" is ultimately overcome.

These remarks indicate that the respect for the snake and its association with good fortune was also known to both Germans and Slavs. The heathen past, however, is farther removed from these peoples than form the Latvians and Lithuanians. If similar snake-cults existed in Germany and in Slavic lands, they were not practiced on the same scale within recorded history as they were by the Baits. The cited fourteenth to eighteenth century reports on the Baits were written by Slavs and Germans and already then the surprise and disgust with which they viewed Baltic snake-veneration gives us a good indication of the place of the snake within their own cultures.

Cursory perusal of present-day Germanic and Slavic beliefs about the snake seems to verify the fact that, indeed, the snake is usually considered deceitful and malevolent. The majority of folk-beliefs, expressions, and proverbs reflect this general negative attitude. There are only a few examples of a positive regard for the snake, usually associating it with powers of healing. One may speculate that the folk medicine beliefs which prescribe the use of a snake as an effective cure may be partially explained by the notion that evil conquers evil (ie. an extension of similia similibus curantor). This, however, is mere speculation for it is also likely that the snake's obvious vitality may be responsible for its specification in various folk cures. This latter case seems to be well supported in the Baltic beliefs (cf. folk-belief 38, 39) since the name for snake, gyvatė, and its association with gyvata 'life' helps one to consciously sense the logical correlation.

Stories which mention the affinity between snakes and children are probably known throughout the world because they describe an unexpected occurrence. W. Hand has suggested that the credibility of such stories rests on the notion that the child's innocence and helplessness can not be breached even by a snake (Hand 1968). Note that this kind of logic presupposes that the snake is evil.

Hence, although a more thorough investigation is definitely required, one may still suggest that the Baits have sustained through their history a more sympathetic regard for the snake than either the Germans or Slavs. Assuming that this hypothesis may be true, let us now see how it might be related to the discussion of our tale.

When one assumes no comparable folkloric basis among the Germans and Slavs with regard to the snake, then the Baltic tale would make very little "cultural sense" to these people and even if it penetrated into their cultural spheres, it would probably by altered by the same process which seems to be occurring with the Latvian tales. Secondly, even if we posit the existence of a similar positive attitude toward the snake in these cultures at a pre-Christian time, these beliefs would now seem to have almost entirely died out. In any case, even though there may be some survivals, there has been no comparative retention of respect and reverence for the snake among the Germans and Slavs as one finds with the Baits. The narrative motif of this tale clearly rests on a folk-belief which serves as an ideological backbone to the story. Conversely, people unfamiliar with the underlying folk-belief or possessing quite antithetical beliefs would find this tale lacking in cultural meaning and, therefore, "untransferable," at least in its original form.

TREES

Another typical element of the Baltic 425 M tale is the terminating motif where the heroine and her children are transformed into trees. Swahn has commented that it is this motif which gives the tale the character of an aition-legend (Swahn 1955: 341). However, most Baltic aetiological-legends rarely possess such fantastic Märchen-type motifs as a supernatural husband, difficult tasks or name taboo and are certainly not so elaborate or complex as this specific tale. The explanation for the curse-inflicted transformation is based in Baltic folk-beliefs. First of all, the power of the heroine's word is what brings about the arboreal transformation. To this very day the Balts believe that a parent's curse is most effective in bringing about dire consequences to her children. This belief is, of course, also well known in other cultures. Secondly, one can observe that the transformation into trees is typically Baltic. The full impact of this motif to the Baits is directly related to their folk-beliefs and is not simply an element of the story to be appreciated on an aesthetic basis. The Balts have retained to this very day a special empathy for trees. They believe that trees are like humans in that they also have a heart and blood (sap). When cut down without good reason, they feel pain and there are folk accounts of how real blood has flowed out of injured trees. For this reason, parents always instruct their children (as this writer was instructed) never to pluck leaves, break the branches or peel the bark from a tree since it experiences the same kind of pain as when someone pulls the hair of one's head or peels off his skin from his body. Whoever injures a tree in such a manner will eventually have to suffer a similar pain in his own life. Trees also have a language of their own which man is unable to understand. One can, however, hear a tree cry and moan every time an axe digs into its trunk by putting his ear to the tree-trunk.

All these current beliefs stem from a conviction rooted in the pagan era that the souls of the dead actually go into trees, usually the ones growing near a person's homestead or more specifically, near his grave. For this reason, trees in cemeteries are considered especially sacred and must never be touched by a pruner's hand since "to cut a cemetery tree is to do evil to the deceased" (Gimbutas 1963: 191). This belief in total reincarnation of one's life force in a tree has been slightly altered by the influence of Christianity. It is quite commonly heard that souls which must undergo penance for their sins are sent by God into trees. Thus, when a tree creaks on a windless night, it is in truth the weeping and crying of the penitent soul that one hears. One must then pray for them, mentioning Adam and Eve, and the soul will be pardoned and the tree will cease its creaking. It is said that souls in general inhabit old spruces, but more specifically, a girl's soul will pass into a linden or a birch while a man's soul will enter an oak, ash or alder. In general, all trees are holy save the aspen which is believed cursed because it was on that tree that Judas hung himself. This is directly related to our tale where the youngest daughter, the one who betrayed her father, is especially cursed and transformed into an aspen.

Another proof linking reincarnation with trees is found in the funeral laments which have served as a reservoir of on-going folk-belief up until this present century, In one, a mother addresses her dead daughter:

What kind of flower will you bloom in? What kind of leaf? What blossoms will you sprout when I walk by? How will I recognize you? How will I know you? Will you be in flowers? In leaves? (Šalčiūtė 1967:42).

A daughter cries for her mother:

.. .I will ask my brother that he would plant a birch on my mother's grave. When the cold storms will come, I shall go up the high hill to my mother's grave. The birch branches will enfold me like my mother's white arms. The north wind will not blow on me, the biting rain will not fall on me (Jonynas et al 1954: 522).

A daughter cries for her father:

Oh that a green plane-tree would grow from my father's grave. All the beautiful birds would then alight there, and would pick sweet berries. Oh, a mottled cuckoo would weep for you with her song (ibid.:52B).

And a mother laments for her. daughter:

Oh my dearest little daughter, Oh, how will you sleep in the black earth where the winds don't blow, where the sun doesn't shine. Only the cuckoo will cry. Only the little birds will sing in the white birch on your little grave! (ibid.:533).

Other than laments, many Lithuanian folksongs draw analogies between man and trees or plants. The usual epithet for a young girl is "white lily" and for a young lad it is "white clover." Constant parallels are also drawn between a young maid and a green linden and a young man and a green oak. As folksong scholars have marked, this type of parallelism usually enhances the songs' poetical quality and these traditional "formulaic expressions" may have persisted precisely because of their aesthetic appeal. Nevertheless, they seem to be instrumental in shaping the general world-view of the people who sing them and it is, therefore, not at all surprising that the Baits do feel this close identity with nature. The following Lithuanian folksong well illustrates this:

Oh dearest father, don't cut the birch growing near the road.

Oh my own true mother, don't fetch the water from the stream.

Oh my own true brother, don't cut the hay near the water.

Oh my own true sister, don't pluck the flowers in your garden.

The birch near the road is really me, the young one.

The water from the stream — my sorrowful tears.

The hay near the waters — my yellow hair.

The flowers in the garden — my bright little eyes.

(Balys 1948: II 64).

CUCKOO

It is interesting to observe that in many Baltic folktales, legends, songs and beliefs, women turn into cuckoos out of grief when they have been separated from ones they love. This motif constantly repeats itself in the laments where the mourner expresses a desire to turn into a cuckoo and "weep with its song." This belief is clearly reflected in those variants of the tale where the heroine becomes a cuckoo and her children become either trees or other birds.

Any attempt to demonstrate that the tale is a Baltic oicotype because of its close correlation to Baltic folk-beliefs becomes more difficult when dealing with these other motifs of the story. The power of a parent's curse, the transformation to some other form of plant or animal out of grief, even the idea of reincarnation in trees are not solely unique to the Baits but are found in other European folk traditions. What may be somewhat atypical is that among the Baits these beliefs are still widespread and constantly expressed to this very day and find reinforcement in songs and laments. It may then be argued that all of these factors help to imbue the story with a cultural relevance for the Balt which might not be so quickly perceived or deeply felt by a German or Slav. But it must be admitted that the case for these motifs, ie. trees, cuckoo, is not nearly so strong as that for the snake when discussing possible factors that would have limited the tale to the Baltic countries.

CONCLUSION

One conclusion that can certainly be drawn is that the motifs of the tale and their ultimate structure (ie. sequence of events) reflects many still very viable folk-beliefs which are generally known to most Baits. This would almost suggest that the tale is not as fantastical as it would first seem since it is so deeply rooted in a folkloric reality accepted by the people who relate it. Whether the story should therefore be considered a Sage rather than a Märchen (its usual classification by folktale scholars) is another matter.

The initial purpose of this study — to illustrate how folk-beliefs may be the laws which account for oicoty-pification of a folk tale — has been partially fulfilled. If one of the "laws" which affect the life of a story is the relevance which it may have for the people via various folk-beliefs and convictions, then that case has been well demonstrated. But whether this relevance simply enhances the popularity of the tale or is actually the crucial life-root which maintains the existence of the tale and restricts its migration requires much more substantial proof. If our analysis of the disintegration of some of the Latvian variants is valid and the general discussion of the folk motifs, especially the snake, is also of some merit, then perhaps our research is at least heading in the right direction.

🐍🐍🐍

Folktale Type 425-M: A Study in Oicotype and Folk Belief - Elena Bradunas

LITUANUS

LITHUANIAN QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

Volume 21, No.1 - Spring 1975

Editors of this issue: Antanas Klimas, Thomas Remeikis, Bronius Vaškelis

Copyright © 1975 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

Lituanus

"IF YOU KILL A SNAKE — THE SUN WILL CRY"

Folktale Type 425-M

A Study in Oicotype and Folk Belief

ELENA BRADŪNAS

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

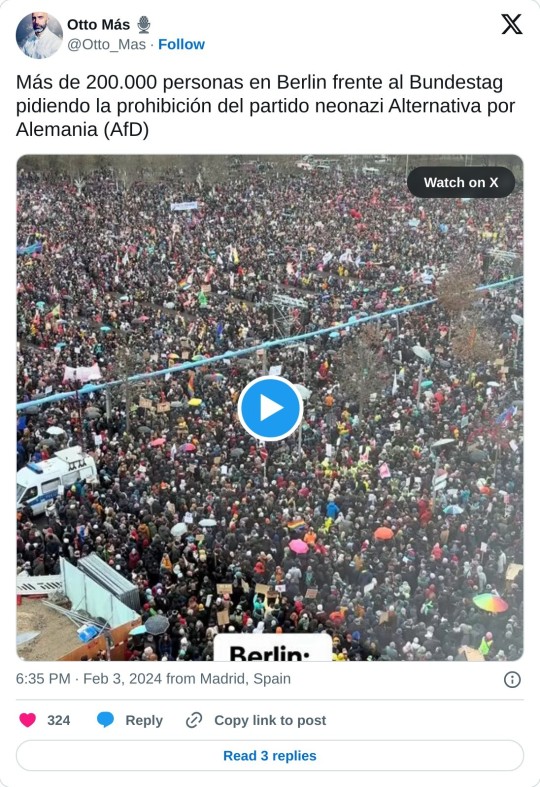

Common Dreams Staff

Feb. 3, 2024

“All together against racism,” the crowd in Berlin shouts. Some held posters that said “Heart instead of hate” or “Racism is not an alternative.”

Up to 300,000 people took to the rainy streets of Berlin, Germany on Saturday as nationwide protests against the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) party. Protests were also taking place in dozens of other cities such as Freiburg, Dresden, Hannover, and Mainz, a sign of growing alarm at growing support for the AfD.

Under the slogan “We are the Firewall” — a reference to the longstanding taboo against collaborating with the far right in German politics — protesters turned the space next to the Bundestag, or national parliament, into a sea of signs, flags, and umbrellas.

“All together against racism,” the crowd in Berlin shouted. Some held posters that said “Heart instead of hate” or “Racism is not an alternative.”

The new wave of mobilization against Alternative for Germany (AfD) was ignited by a January report by investigative outlet Correctiv. It revealed that AfD members had discussed the expulsion of immigrants and “non-assimilated citizens” at a meeting with extremists.

The report sent shockwaves across Germany at a time when the AfD was soaring in opinion polls, months ahead of three major regional elections in eastern Germany where their support was strongest.

“We absolutely must not allow the stories that we experienced in 1930 or even back in the 1920s to happen again ... We must do everything we can to prevent that,” said Jonas Schmidt, who came from the western port city of Bremen told the Associated Press. “That’s why I’m here.”

Kathrin Zauter, another protester, called the strong attendance “really encouraging.”

“This encourages everyone and shows that we are more — we are many,” she said.

Jakob Springfeld, the spokesman for the NGO Solidarity Network Saxony, said he was shocked that it had taken such a long time for mass demonstrations against the far-right, given the AfD had been successful in many smaller communities already. "But there's a jolt now. And the fact that the jolt is coming provides hope, I believe."

German Chancellor Olaf Scholz praised the protests, writing in a Saturday post on the social media platform X that citizens’ presence at the gatherings is “a strong sign for democracy and our constitution.”

“In small and big cities across the country, citizens are coming together to demonstrate against forgetting, against hate and incitement,” he added.

Saturday's protest was a collaboration involving more than one thousand entities, including leave none behind, Amnesty International, Echo Iran, and FridaysForFuture, initiated the call for action against right-wing extremism at the Reichstag building. (Photo by HAMI ROSHAN/Middle East Images/AFP via Getty Images)

A participant holds up a placard reading 'No sex with Nazis' during a rally under the motto 'We are the firewall' called for by international non-profit organisation 'Hand in Hand' against right-wing politics in front of the Reichstag building in Berlin, Germany on February 3, 2024. (Photo by ADAM BERRY/AFP via Getty Images)

"We are the firewall" for democracy and against right-wing extremism. With the demonstration, the participants want to set an example of resistance against right-wing extremist activities. (Photo by Kay Nietfeld/picture alliance via Getty Images)

3 notes

·

View notes