#abdulhamid i

Photo

The most powerful Ottoman Sultans + their Valides

#ottoman#osman i#halime hatun#ertugrul#mehmed ii#huma hatun#mehmed bir cihan fatihi#suleiman i#ayse hafsa sultan#hafsa sultan#mc#magnificent century#abdulhamid ii#tirimujgan kadin#payitahtabdülhamid#ottoman sultans#ottoman empire#valide sultan#myedit#historyedit#history

173 notes

·

View notes

Text

Don't forget your daily click Help the Palestinian People with a Click | arab.org

---Also some other links---

eSims For Gaza (gazaesims.com)

Care For Gaza (@CareForGaza) / X (twitter.com)

Direct Aid for Gaza 🇵🇸 (@GazaDirectAid) / X (twitter.com)

-----

The Sonic fandom has had a bit of a weird relationship with Zionism lately, so I thought I'd take the opportunity to spread some links for Palestine.

https://gofund.me/496dafbb

Fundraiser by Belal Emad Hamdy Khalifa : Get Family out of Gaza. Build a new life in Egypt. (gofundme.com)

#sonic the hedgehog#sega sonic#metal sonic#from river to sea palestine will be free#from the river to the sea palestine will be free#this isn't related to mike pollocks tweets#remember to boycott#boycott paramount

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

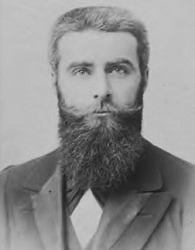

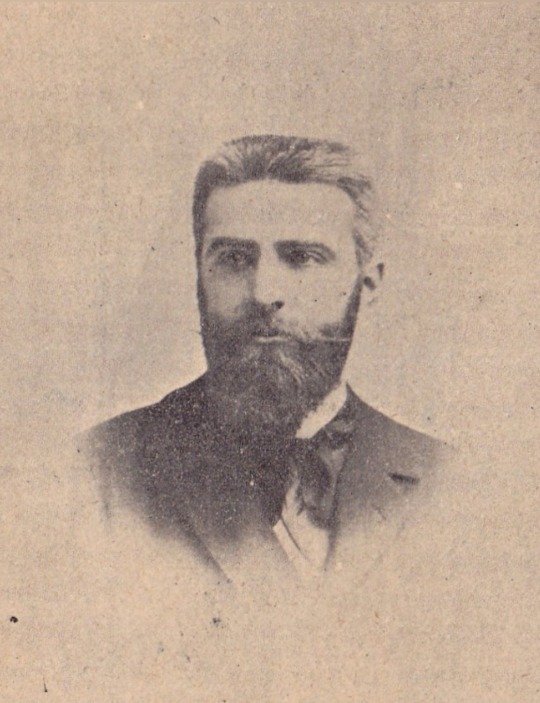

Ahmed Rıza, was an Ottoman politician, writer, educator and the leader of the Young Turk movement. He lived in the last periods of the Ottoman Empire, and struggled to keep his homeland, which was about to collapse, alive throughout his life.

He tried to emphasize the unfairness of the Western Imperialism conducted in Anatolia in

his works, and tried to defend the East against the West in the line of civilization.

No difficulties he faced could intimidate him and he continued to walk with a determined stance on the path he believed in, even though his friends distanced himself from him for the sake of self-interest or because of his "idealistic" ideas.

"His name was whispered in secret, with deep reverence and admiration. Ahmed Rıza was always rising and living in dreams, like an inaccessible high mountain, always out of sight, always covered with clouds. There were legends about him; stories and anecdotes were being told to show his greatness... As the administration of Abdulhamid defiled many of the freedom fighters who had fled to Europe and stained them with a greed for self-interest, Ahmed Rıza's irreconcilable, unyielding face rose in our hearts." -these are the words of the Turkish writer Huseyin Cahit Yalçın.

As a young lady, i could say that he is my SWEETHEART

85 notes

·

View notes

Text

Birgi Çakırağa Konağı (Ödemiş, İzmir)

Türk Rokoko mimarlığının en güzel örneklerinden biri olan Çakırağa Konağı, mimari üslubunu korumuş ender konaklardan biridir.

Rivayete göre Çakıroğlu’nun biri İzmirli, diğeri İstanbullu iki eşi varmış.

Eşlerinin sıla hasretlerini gidermeleri için İstanbul odasına, içinde yelkenlilerin yüzdüğü Haliç, İzmir odasına ise Kadifekale’den Konak panoramik manzaralarının yer aldığı duvar süslemelerini yaptırmıştır.

Konağın I. Abdülhamid (1774-1789) veya III. Selim devrinde (1789-1807) yapıldığı düşünülmektedir.

Osman Kürşat SERTTÜRK

.......

Birgi Çakırağa Mansion (Ödemiş, İzmir, Türkiye 🇹🇷)

Çakırağa Mansion, one of the most beautiful examples of Turkish Rococo architecture, is one of the rare mansions that has preserved its architectural style.

Rumor has it that Çakıroğlu had two wives, one from Izmir and the other from Istanbul.

In order for his wives to relieve their homesickness, he had wall decorations made in the Istanbul room, showing the Golden Horn where sailboats sail, and in the Izmir room, with panoramic views of Konak from Kadifekale.

The mansion was built by Abdulhamid I (1774-1789) or III. It is thought to have been built during the Selim period (1789-1807). Osman Kürşat SERTTÜRK

#Birgi Çakırağa Konağı#konak#ödemiş#izmir#2.Abdülhamid#3.Selim#ottoman#ottoman empire#sıla#hasret#türkiye#doğa#travel photography#travel destinations#travel#manzara#view#natural#europe#africa#barok#mimari

31 notes

·

View notes

Note

If Hatice decided to divorce Ibrahim, would he really lose everything as she states in that argument in season 2? He was grand vizier before he married her. I know Lufti Pasha was dismissed as Grand Vizier but he physically assaulted Sah. Considering Suleiman favors Ibo so much, would he really dismiss Ibo? I know his power and reputation would take a bit but how much of one in an au?

Another alternate universe question- could Hatice be capable of staying married for their children and Mustafa but not falling back in love/reconciling with Ibrahim? Or is that completely out of her character?

So, admittedly, this is a matter that I have to divorce from the "real historical" a bit as, had this actually occurred, it would've been career suicide on Ibrahim's part. The only rough equivalent I can find is the affair that, ironically a different Hatice, daughter of Murad V, had with the husband of Naime, daughter of Abdulhamid II. That man, Kemaleddin Paşa, found himself not only divorced, but stripped of military ranks and exiled to Bursa. And that was in 1904!

I could see how the Suleiman of the show, who seemed oddly prepared to forgive Ibrahim for almost anything, might behave otherwise, but, in reality, Ibrahim would have absolutely been stripped of his position, I believe. These women, particularly in the era where slavery was still permissible in the empire, outranked their husbands, so any insult to their honor (and, by extension, the honor of the dynasty itself) carried with it strict punishments.

I do think, however, that it wouldn't stretch the limits of Hatice's character to remain wed for politic over love. It's tragic, yet realistic, for there to come a point where she has to awaken from the fairy tale at last. A sort of steady realization that, losing her "grand love" doesn't mean she also loses her own power. I could honestly see her becoming an Imperial princess with more heart on display than Şah, but with equal astuteness. (I'd pay to watch her own agenda clash with Ibrahim's at some point too.)

There's even a chance for her to still fall into guilt after Ibrahim's death, wondering, if she had just given him that second chance, could things have been better.

I live for restructuring things away from the sexist angle the writers take of "the most powerful thing women do in the show is die for their love" so I wouldn't go for it, I think.

#answered#anon#magnificent century#hatice sultan#suicide tw#like i'd love to write a scene where hatice realizes ibrahim is trying to manipulate her emotions to have is way as always#and just hauls off and slaps him for it

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Duhovna dimenzija obuhvata sumu ljudskih aktivnosti i u kontekstu toga svako čovjekovo djelo može potencijalno biti ibadet, odnosno, bogougodno djelo, sve u zavisnosti od cilja i namjere, i bez obzira na kvantitet i karakter — bilo da se radi o respektabilnim djelima ili stremljenjima duše. Tako, shodno univerzalnoj kur'anskoj viziji, cijeli život jednog muslimana jeste zikr i džihad — spominjanje i svijest o Allahu i ulaganje duhovnog i fizičkog napora, odnosno obožavanje i bogoslužje. Život jednog muslimana protiče u obavljanju propisane molitve — pet dnevnih namaza, činjenju dove, postu, davanju zekata, učenju Kur'ana, poštivanju propisa i provođenju obreda — sve ove aktivnosti određuju i oživljavaju dušu muslimana i predstavljaju njegov dosljedan odgovor na propisane dužnosti i Božanske preporuke navedene u Kur'anu:

“Ja sam, uistinu, Allah, drugog boga, osim Mene, nema; zato se samo Meni klanjaj i molitvu obavljaj – da bih ti uvijek na umu bio!” (Ṭāhā, 14.)

”Postići će šta želi onaj koji se očisti i spomene ime Gospodara svoga pa molitvu obavi!” (El-Eʿlā, 14—15.)

”Ako se budete nečega bojali, onda hodeći ili jašući. A kada budete sigurni, spominjite Allaha onako kako vas je On naučio onome što niste znali.” (El-Bekare, 239.)

“Kazuj Knjigu koja ti se objavljuje i obavljaj molitvu, molitva, zaista, odvraća od razvrata i od svega što je ružno; obavljanje molitve je najveća poslušnost! – A Allah zna šta radite.” (El-ʿAnkebūt, 45.)

“I za one koji se, kada grijeh počine ili kad se prema sebi ogriješe, Allaha sjete i oprost za grijehe svoje zamole – a ko će oprostiti grijehe ako ne Allah? – i koji svjesno u grijehu ne ustraju.” (Āli-ʿImrān, 135.)

.…

Abdulhamid Ebu Sulejman, Slabljenje islamske civilizacije i njena obnova: obrazovni i odgojni korijeni

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

My Love for Central Asian Literature Part 1 – Abdurauf Fitrat, Abdulla Qodiry, and Cho’lpon

I’m currently working on a script for my history podcast, the Art of Asymmetrical Warfare, about three Central Asian literary giants: Abdurauf Fitrat, Abdulla Qodiry, and Abdulhamid Sulayman o’g’li Yusunov also known as Cho’lpon and it got me thinking about their influence on my historical interests, reading tastes, and writing style.

If you’re wondering why a podcast about asymmetrical warfare is talking about three Central Asian writers, you should check out my upcoming podcast episode. 😉

How I Became Interested in Central Asian Literature

My interest in Central Asia has been a long time percolating and it was just waiting for the right combination of sparks to turn it into a hyperfixation (sort of like my interest in the IRA). I went to the Virginia Military Institute for undergrad and majored in International Relations with a minor in National Security and my focus was on terrorism. So, I knew a lot about Afghanistan and Pakistan and the “classic” “terrorists” like the IRA, the FLN, Hamas, etc. and I knew of the five Central Asian states (one of my professors was banned for life from either Turkmenistan or Tajikistan and sort of life goals, but also please don’t ban me haha), but my brain bookmarked it, and I went on my merry way.

Then I went to University of Chicago for my masters, and I took my favorite class: Crime, the State, and Terrorism which focused on moments when crime, government, and terrorism intersect. This brought me back to Pakistan and Afghanistan, but this time focusing on the drug trade which led me to Uzbekistan and Tajikistan and their ties to the Taliban and it was sort of like an awakening. I suddenly had five post-Soviet states (if you know me, you’ll know I’m fascinated by post-Soviet states) with connections to the drug trade (another interest of mine) and influenced by Persian and Turkic identities. I was also writing a scifi series at the time that included a team of Russian, Eastern European, and Central Asian scientists and officers, so the interest came at the right time to hook my brain. Actually, if you buy my friend’s EzraArndtWrites upcoming “My Say in the Matter” anthology, you’ll read a short story featuring Ruslan, my bisexual, Sunni Muslim, Uzbek doctor who was inspired by my sudden interest in Central Asia.

Hamid Ismailov’s the Devils’ Dance

I wanted to know more beyond the drug trade and usually when I try to learn about a place whether it be Poland, Ireland, or Uzbekistan, I go to their music and literature. This led me to one of my all-time favorite writers Hamid Ismailov and my favorite publishers Tilted Axis Press.

Tilted Axis Press is a British publisher who specializes in publishing works by mainly Asian, although not only Asian writers, translated into English. They publish about six books a year and you can purchase their yearly bundle which guarantees you’ll get all six books plus whatever else they publish throughout the year. I’ve purchased the bundle two years in a row, and I haven’t regretted it. The literature and writers you’re introduced to are amazing and you probably won’t normally have found unless you were looking specifically for these types of books.

Hamid Ismailov is an Uzbek writer who was banished from Uzbekistan for “overly democratic tendencies”. He wrote for BBC for years and published several books in Russian and Uzbek. A good number of his books have been translated into English and can be found either through Tilted Axis or any other bookstore/bookseller. Some of my favorites include Dead Lake, the Manaschi, the Underground, and the book that inspired everything the Devils’ Dance.

Tilted Axis’ translation of The Devils’ Dance came out the same year I was working on my masters, and I bought it because it is a fictional account of Abdulla Qodiriy’s last days while in a Soviet prison. He goes through several interrogations and runs into his fellow writers and friends: Fitrat and Cho’lpon. Qodiriy is written as detached from events while Cho’lpon comes across as very sarcastic, as if this is all a game, and Fitrat is interestingly resigned to the Soviet’s games but seems to have some fight in him. Qodiry distracts himself from the horrors around him by thinking about his unwritten novel (which he really was working on when he was arrested by the NVKD). His novel focuses on Oyxon, a young woman forced to marry three khans during the Great Game. His daydreaming takes a power of its own and he occasionally slips back to talk with historical figures such as Charles Stoddart and Arthur Connolly-two British officers who were murdered by the Khan of Bukhara (not a 100% convinced they didn’t have it coming).

We spend half of the narrative with Qodiriy and the other half with Oyxon as she is taken from her home and thrown into the royal court of Kokand’s khans where she is raped and mistreated and has to survive the uncertain times of Central Asia during the Great Game. She is passed from Umar, the father, to Madali, the son, to the conquering Khan of Bukhara, Nasrullah who eventually murders her and her children. From a historical perspective, I have a lot of questions about Nasrullah because a lot of sources write him off as a cruel tyrant and nothing more which usually means there’s more…Before Oyxon and Qodiriy are taken to their deaths, there is a poignant scene where the two timelines merge into one that will stay with you long after the novel is over.

The book is a masterpiece exploring themes of colonialism, liberty, powerlessness in face of overwhelming might, the power of the human mind and spirit, the endurance of ideas, even when burned and “lost”, as well as being a powerful historical fiction about two disruptive periods in Central Asian history. It’s also a love letter to the three literary giants of Uzbek fiction: Abdurauf Fitrat: a statesmen who crafted the Turkic identity of Uzbekistan, a playwright and statesmen, Abdulla Qodiriy who created the first Uzbek novel (O’tgan Kunar which was recently translated by Mark Reese and can be bought in most bookstores), and Cho’lpon who created modern Uzbek poetry (you can buy his only novel Night translated by Christopher Fort and a collection of his poems 12 Ghazals by Alisher Navoiy and 14 Poems by Abdulhamid Cho’lpon translated by Andrew Staniland, Aidakhon Bumatova, and Avazkhon Khaydarov in any bookstore).

City of Kokand circa 1840-1888, thanks to Wikicommons

All three men were Jadids (modern Muslim reformers) who worked with the Bolsheviks to stabilize Central Asia, helped create the borders of the five modern Central Asian states, and were murdered by the Soviets during Stalin’s Great Purge of the 1930s. It was illegal to publish their work until the glasnost. Check out my history podcast to learn more about the Jadids and the Russian and Central Asian Civil Wars.

From a literary perspective however, Ismailov wrote the Devils’ Dance similarly to Qodiriy’s own O’tgan Kunlar and Cho’lpon’s Night (whereas Ismailov’s other books: Dead Lake and the Underground are more Soviet era Central Asian literature and his newest book the Manaschi is more post-Soviet). Like Qodiriy and Cho’lpon, Ismailov writes about MCs who are not the master of his own fate, but instead are going through the motions of a fate already written, one of his MCs is a woman unfairly caught in a misogynistic system that uses women as it sees fit (although I would argue that Hamid gives his women characters more agency than either Qodiry and Cho’lpon), and he writes about the corruption and inefficiencies of whatever government agency is in control at the time – whether it be a Russian, a Khan, or an indigenous agent of said government. All three books end in death, although only Cho’lpon’s Night and Ismailov’s the Devils’ Dance end in a farce of a trial. Even stylistically Ismailov mimics the rich and dense language of Qodiriy whereas I find Cho’lpon’s style crisper although no less rich for it.

Abdurauf Fitrat’s Downfall of Shaytan

While Ismailov led me down a historical rabbit hole which is captured on my history podcast, I also wanted to see if any of Fitrat’s, Qodiry’s, or Cho’lpon’s work had been translated into English.

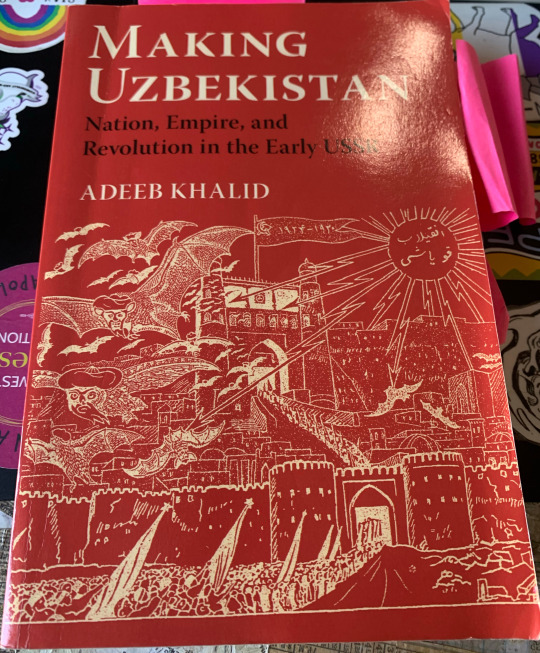

So far, I can’t find anything by Fitrat except excerpts in the Devils’ Dance and Making Uzbekistan by Adeeb Khalid (one of my all-time favorite history books by one of my favorite scholars who also happens to be very kind and patience and I still can’t believe I interviewed him for my podcast).

Fitrat wrote a specific play I really want to read called Shaytonning Tangriga Isyoni which Dr. Khalid translated as Shaytan’s Revolt Against God. According to the summary provided by Dr. Khalid it is a challenging take on the Islamic version of Satan’s downfall.

According to Dr. Khalid, in Islamic cosmology God created angels from light and jinns from fire and they could only worship God. When God made Adam, He commanded all angels and jinn to bow before him. Azazel (who would become Shaytan) refused claiming he was better than Adam who was made out of clay. He was cast out of heaven and became Shaytan/Iblis.

Fitrat reimagines Shaytan’s defiance as heroic. He is disgusted by the angels’ submissive nature and God’s ability to create anything and yet he chooses to create servants. Azazel has seen God’s plan to create another being out of clay and have the angels worship him as well, which Azazel sees as a betrayal on God’s part. Gabriel, Michael, and Azrael try to convince Azazel to see reason and instead he brings his grievance to the other angels who are confused. God intervenes and the angels give in, but Azazel continues to defy God. God strips him of his angelic nature, and he turns into Shaytan who warns Adam of God’s treacherous nature and vows to free him and all other creatures from God’s trickery.

Doesn’t it sound amazing?! Fitrat has outdone Milton in terms of completely overturning God’s and Satan/Shaytan’s rules (also no wonder he was marked for execution right? Complete firebrand and pain in the ass (and I mean that with love)) and I really want to read it. So, either someone needs to translate this into English, or I need to learn Persian/Uzbek, which ever happens first, haha (judging on how my Russian is going…)

Abdulla Qodiry’s O’tgan Kunlar

While I can’t find any of Fitrat’s work in English, there have been two translations of Abdulla Qodiriy’s novel and the first ever Uzbek novel O’tgan Kunlar. In English, the title translates as Days Gone By or Bygone Days. There are two translates out there: Days Gone By translated by Carol Ermakova, which is the version I’ve read, and Otgun Kunlar by Mark Reese, which I haven’t read yet but I’ve heard him speak (and actually spoke to him about his translation – thank you Oxus Society) so you can’t go wrong with either one.

O’tgan Kunlar is an epic novel set in the Kokand Khanate in the 18th century and is about Otabek and his love Kumush. There’s also a corrupt official, Hamid who hates Otabek because Otabek is a former who wants to change the society Hamid benefits from. Hamid tries to get Otabek killed for treason because of his reformist believes, but the overthrow of the corrupt leader of Tashkent (who Otabek worked for) saves Otabek’s life. However, the corrupt leader’s machinations convince the Khan to declare war against the Kipchaks people, who are massacred. Otabek and his father vehemently disagree with the massacre of the Kipchaks.

Once Otabek is released and gets revenge against Hamid, he marries Kumush without his parent’s approval and is torn between the two families. His mother hates Kumush and forces him to take a second wife, Zainab. Obviously, things go terribly wrong as Otabek doesn’t even like Zainab and Kumush doesn’t know how to feel about her husband having a second wife. Zainab hates her position within the household and eventually poisons Kumush.

Abdulla Qodiriy thanks to Wikicommons

O’tgan Kunlar is considered to be an Uzbek masterpiece that is central to understanding Uzbekistan. Not only is it a great tragic love story, but it also highlights some of the things Qodiriy was thinking about as he engaged with other Jadids. Just as Otabek argued for reforms especially in the educational, social, and familial realms, the Jadids were making the same arguments. We can also see the Jadid’s struggle with the ulama and the merchants in Otabek’s struggle with Hamid. Qodiry attempts to capture the struggle women went through by writing about the horrors for arrange marriages and polygamy, but Kumush is an idealized version of a woman. She is the pure “virgin” like Margarete from Faust while the other two female characters; Otabek’s mother and Zainab are twisted, bitter woman who hurt those they “love”. One could argue they’ve been corrupted by the society they live in, but they also lack the depth of Otabek and even his father.

One of the most interesting parts of the novel is the massacre of the Kipchaks because it is written as the horror it was and both Otabek and his father condemn the action. His father even claims that there is no sense if hating a whole race for aren’t we all human? Central Asia is a vast land full of different peoples who share common, but divergent histories and while these differences have led to massacres, there have also been moments of living peacefully together. It’s interesting that Qodiriy would pick up that thread and make it a major part of his novel because this was written during the Russian Civil Wars and the attempts to create modern states in Central Asia. The Bolsheviks really pushed the indigenous people of Central Asia to create ethnic and racial identities they could then use to better manage the region and so one wonders if Qodiriy is responding to this idea of dividing the region instead of uniting it.

Cho’lpon’s Night

While O’tgan Kunlar is a beautiful book and Qodiriy is a masterful writer, I prefer Cho’lpon’s Night (although don’t tell anyone). Night was supposed to be a duology, but Cho’lpon was murdered before he could finish the second book. Cho’lpon wrote Night in 1934, after years of being attacked as a nationalist. It was a seemingly earnest attempt to get into the Soviet’s good graces. Instead, he would be murdered along with Qodiriy and Fitrat in 1938.

Night is about Zebi, a young woman, who is forced to marry the Russian affiliated colonial official Akbarali mingboshi. The marriage is arranged by Miryoqub, Akbarali’s retainer. Akbarali already has three wives and, like in O’tgan Kunlar, adding a new wife causes lots of problems in the household. Meanwhile Miryoqub falls in love with a Russian prostitute named Maria and they plan to flee together. While they are fleeing they met a Jadid named Sharafuddin Xo’Jaev and Miryoqub becomes a Jadids. Meanwhile Akbarali’s wives conspire against Zebi and attempt to poison her but she unwittingly gives it to Akbarali instead. Zebi is arrested and found guilty of murdering her husband and sentenced to exile in Siberia. The book ends with Zebi’s father, who encouraged her marriage to Akbarali, is driven made by his daughters fate and murders a sufi master while Zebi’s mother goes mad, wandering the streets and singing about her daughter.

Like Qodiriy, Cho’lpon is interested in examining governmental corruption, the need for reform, and women’s plight, but Cho’lpon is less resolute than Qodiriy. Cho’lpon’s novel is constructed similar to poetry: an indirect attempt to capture something that is concrete only for a moment.

His characters are own irresolute or ignorant of important pieces of information meaning they are never truly in full control of their fates. Even Miryoqub’s conversion to Jadidism is to be understood as a step in his self-discovery. In Cho’lpon’s world, no one is ever truly done discovering aspects of themselves and no one will ever have true knowledge to avoid tragedy.

Cho'lpon courtesy of Wikicommons

It is interesting to read Night as Cho’lpon’s own insecurity and anxiety about his own fate and the fate of his fellow countrymen as Stalin seemingly paused persecuting those who displeased him. While Qodiriy crafted and wrote O’tgan Kunlar in the 1920s, which were unstable because of civil war, but promised something greater as the Jadids and Bolsheviks regained control over the region, Cho’lpon wrote Night during the height of Stalin’s Great Terror, most likely knowing he would be arrested and executed soon.

Both novels are beautifully written historical novels about a beautiful region, but I prefer Cho’lpon’s poetic prose and uncertainty.

Conclusion

Reading the works of Fitrat, Qodiriy, and Cho'lpon not only introduced me to a history I knew little about, but also introduced me to a whole literature I never knew existed. The books mentioned in this blog post are beautiful pieces literature and will challenge how you see the world and how much literature we miss out on when we don't read beyond authors who work in our native tongues.

The canon of Central Asian literature is immense, with only a handful of books and poems translated into English. I hope more works are translated so other people can engage with these books and poems and learn about these writers and the circumstances that shaped them. And, if you haven't, go check out Tilted Axis who are doing amazing work translating books so people can engage with them.

If you're enjoying this blog, please join my patreon or donate to my ko-fi

#central asian history#central asian literature#abdurauf fitrat#abdulla qodiriy#cho'lpon#O'tgan Kunlar#Days Gone by#Night#Hamid Ismailov#the Devils' Dance#Soviet Union#Soviet Central Asia#Uzbekistan

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

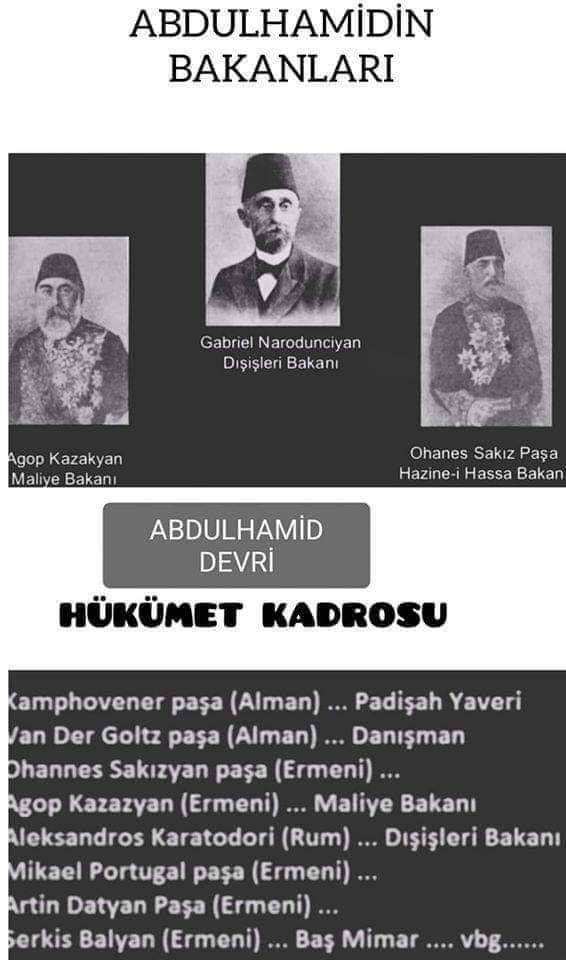

OKU !!!

BU EKİBE IYI BAKIN !

33 SENELIK ABDULHAMİD DEVRINİN EKİBİ

Sonrada devlet batınca vay efendim Türkçülük başlamışta devlet çökmüşmüş.

Peki bu ekonomik iflas tablosunda Türkler nerede ?

Halife-i Müslümin 2. Abdülhamit’in nazırlarından (bakanlarından) ve bürokratlarına bakalim buyrun:

Hariciye Nazırları; Aleksandros Karateodori Paşa (1878-1879)Gabriel Pasha ve Sava Paşa (1879-1880)

Hazine-i Hassa Nazırları: Agop Ohanes Kazazyan (1876-1891), Mikail Portakalyan Efendi (1891-1897), Ohanes Sakız Efendi (1897-1908)

Maliye Nazırı: Agop Ohanes Kazasyan Paşa (28-30 Ağustos 1885), (Aralık 1886 - Mart 1887) (1888-1891)

Nafia Nazırları: Ohanes Çamiç Efendi (1877-1878), Aleksandr Karateodori Paşa (1878) Sava Paşa (1878-1879)

Orman ve Maadin Nazırları; Mavrokordato Efendi (1908-1909), Aristidi Paşa ( 1909)

Ticaret ve Ziraat Nazırları: Bedros Kuyumcuyan Efendi (1880) Gabriel Noradonkyan Efendi (1908-1909)

Ayan Üyeleri(1876); Antopolos Efendii Aristarki Bey, Daviçon Karmona Efendi, Musurus Paşa, Serviçen Efendi, Stoyanoviç Efendi, Dr. De Kastro Bey, Mavroyeni Paşa, Karatodri Paşa, Abraham Karakahya Paşa

Ayan Üyeleri(1908) Azaryan Efendi, Basarya Efendi ,Bohor Efendi, Fethi Franko Bey, Gabriyel Noradonkyan Efendi, Mavrokordato Efendi, Mavroyeni Bey, Oksanti Efendi, Yorgiyadis Efendi, Aram Efendi, Popoviç Temko Efendi,

Babıali Hukuk Müşaviri Gabriel Efendi Abdülhamit zamanında sürekli el üstünde tutulan bu Gabriel Efendi 2. Dünya savaşı sonrası düzenlenen Paris Konferansında Ermeniler için toprak talep etmiş, Lozan Konferansına da Ermeniler adına katılmıştır…

Elçilere göz attığımızda;

Y. Fotiades Bey ve Gobdan Efendi’nin Atina, Azaryan Efendi’nin Belgrad, E. Karatodri Efendi’nin Brüksel, Blak Bey’in Bükreş, Yanko Karaca, Misak Efendi ve Aritraki Efendi’nin Lahey, K. Musurus Paşa, Alfred Rüstem Paşa ve Antopulo Paşa’nın Londra, Naum Paşa’nın Paris, S. Musurus Bey ve Y. Fotiades Bey’in Roma, Nikola Gobdan Efendi’nin Sofya, A. Vogorides Paşa’nın Viyana, L. Aristarki Bey ve A. Mavroyeni Bey’in Washington’da Büyükelçi-Elçi olarak görev yaptıklarını görüyoruz.

Konsolos ve kâtipliklerde de Türk unsurundan ziyade Ermeni ve bilhassa Rum memurlar kullanılmakta idi.

Valilik koltuklarının çoğunda da gayrimüslimler oturuyordu.

Mesela;

Şarkî Rumeli Valileri Sava Paşa, Aleko Vogorides Paşa, Gavril Paşa Hristoiç, Alexandre de Battenberg, Ferdinand de Saxe-Cobourg et Gotha,

Sisam Beyleri; Mişel Gregoriyadis Bey, Aleksander Mavroyeni Bey, Yanko Vitinos Bey, Kostaki Karateodori Paşa, Yorgi Yorgiadis Efendi, Andrea Kopasis Efendi,

Cebelilübnan Sancağı Mutasarrıfları Vasa Paşa, Naum Paşa, Yusuf Franko Paşa

Maliyesini, hariciyesini, tarımını, madenlerini ve de mülkiyesini gayrimüslimlere bırakmış devletin başında bir İslam Halifesi (!) vardır…

ŞİMDİ ANLADINIMIZMI ATATÜRKÜN KİMİN TEKERİNE ÇOMAK SOKTUĞUNU ?

Türk dil KURUMUNA 1 ermeni dilbilgisi uzmanini oda sadece Genel sekreter olarak atadı diye, ki adam osmanlı memuru zaten, 100 senedir Atatürke demediğini bırakmayanlara soralım, insafiniz varmi ?

Kaynak kitap:

KUNERALP, Sinan, Son Dönem Osmanlı Erkan ve Ricali, Prosopografik Rehber, İstanbul: İsis Yayınları, 1999.

(Zkr. Oktay Polat)

Erhan Gürel sayfasından

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Saudi Arabia’s defense was mind blowing 🥹❤️❤️

▪️ Mohammed Alowais

▪️ Yasser Alshahrani

▪️ Ali Albulayhi

▪️ Saud Abdulhamid

▪️ Hassan Al Tambakti

But I feel sad for Messi 😔

#saudiarabia vs #Argentina

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

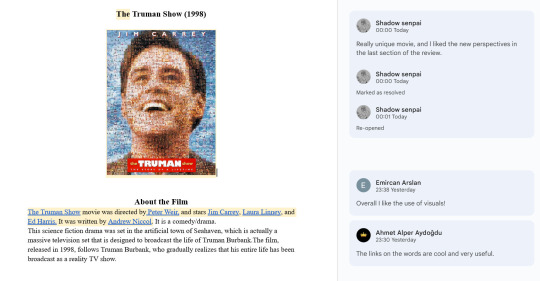

A Film Review: The Truman Show

Hey Boo

How are you doing ? I hope you’re fine and everything is fine. first of all, I want to give u a good news for today. And that is that i got my A1 in spanish today ;( i am so happy for that. I will teach one word this time and that word is película, it means movie. And because we mentioned that i can say that this time our final assignment is to write a movie review but collaboratively and online. With another words, writing together in the same document and in the same time to learn how to work with each other.

Okay, it wasn’t that much hard actually, because we used to do that in writing researches and articles in the other lessons such curriculum design lesson.

I did the review with my close friends again, Elif and Bade. You can check their blogs to.

We used Google Docs to write the review. I was the one who chose the movie :)

The Truman Show is a movie that can effect anyone who watched it because of its different ideas.

It may be Jim Carrey’s best work.

Here is the trailer.

In addition to that, Alper, Emircan and Abdulhamid helped us with their feedbacks and comments.

The easiest part was mine and it was the first part. So i just wrote the the name of the movie, the characters and genre.

But the part that i really like was when i wrote my opinion about the movie.

I am really excited about your opinions.

See you in the comments.

The review.

0 notes

Text

I think it a point worth restating:

The first Muslim claim to Jerusalem is the same claim that the Greek civilization in a Christian form it deposed had. The Yarmuk and Gaugamela have equal legitimacy, if Muslims are the indigenous culture of the region then they supplanted an indigenous culture. If the Greeks they displaced are imperialist colonizers then a religion imposed by soldiers is innately colonialist because it replaced a Christian and Zoroastrian Aramaic and Farsi speaking world with an Arabic Islamic one. Nobody 'voluntarily' adopts a new language, it is always forced by means more or less overtly imperialist, whether or not people have the historical awareness enough to realize this is what happened.

The claim deposed by General Allenby in 1918 at Megiddo was won by the same means by the armies of the Ottoman Sultan, who went against the heirs of Sultan Baibars, eraser of the Crusader states. At the time the three sub-provinces of what would later be termed Palestine were eastern Mamluk zones. As a result of this battle, where the heroic legions of Baibar's successors were butchered by cannons much like they would be again by Napoleon, showing the signal inability of Mamluks to accept the implications of why they were semi-loyal servants of the Ottomans in the first place, the region later merged into Mandatory Palestine became Ottoman territory for 402 years.

And so the question. If winning a battle made Abdulhamid II and the genocidal murder-gang called the Committee of Union and Progress the rightful masters of Jerusalem, why does this only apply to the empire whose conquest unraveled in another conquest and when is the statue of limitations on conquest met?

This is one of the reasons why trying to apply a logic suited to understanding the history of the Americas breaks down very hard in the region where empire begins at the dawn of humankind's experiments in civilization in the hubristic and grandiloquent boasts of the lords of Sumer and Agade of being 'lords of the four corners and all the world.'

Either empires and the identities they spawn as their bastard offspring or legitimate or there's never been any coherent ethnocultural identities in the region, only a sequence of fallen empires and rising and falling religions loosely superimposed into a historical narrative. To grapple with this is to grapple in turn with one of the simplest realities of history. Not every culture comes close to sharing the same narratives or experiences, and projecting the ideal self-image of one culture onto the vastly different experiences when Selim the Grim is a founding father of a 400-year world which was much younger than Ottoman rule of the Balkans, as compared to a world started by James Polk's blundering horde ripping apart the semi-functional and badly wounded Mexico of the Age of Santa Anna.

Some principles, if held to be universal, render entire elements of histories and cultures incoherent and impossible to describe unless one is willing to admit that the history of the Middle East is not that of Europe, or China, or India, or Central Asia, or the Americas, or the Australian continent and that different regions should be treated respectfully, and differently, with awareness the underlying faultlines are also distinct.

#lightdancer comments on history#middle eastern history#islamic history#mamluk history#history of the ottoman empire#point worth noting that Ottomans vs Mamluks had Arabs reduced to serfs at that point and resenting it as they have ever since#they have never accepted that the Seljuks turned them from lords to hewers of wood and drawers of water#no different to how Mexico still resents the loss of Texas and California#though whether or not giving current Texas back to Mexico would be a punishment or not is a different question#a truer history of Arabs as subjects vs lords starts with the Seljuk Sultanate and the Mongol sacking of Baghdad#but that would again require the people who want to defend Islamic history to know anything about it to have those conversations#and that would require them in turn to actually put the effort to find it#and that effort does not and will not exist because it would spoil too many illusions#poor Alp Arslan and Baibars and Selim the Grim and Suleiman the Magnificent#even when the Battles of Actium and Gaixia and Moscow defined history no less in other parts of the world

0 notes

Text

SONNET By Muhammad Abdulhamid Kumo

SonnetFrom far, back I have comeTo their surprise, I brought a dove, Happy they were, everyone at home, And a nest they weaved for her, what a love! My brother, a smith, made her a golden ring. Love and compassion led her out of bondTo the sky she soars up — her song to sing.Between us no frictional touch, but fine fond;In her crops-pasturing afoot she walks, While our eyes tendering on her…

View On WordPress

0 notes

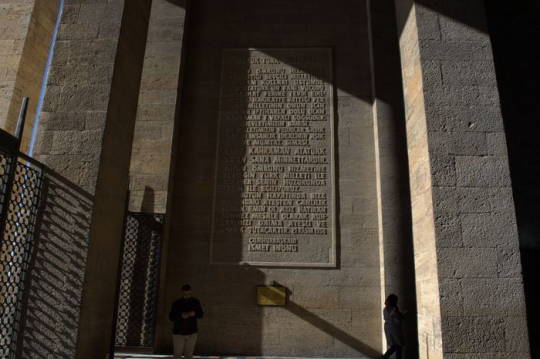

Photo

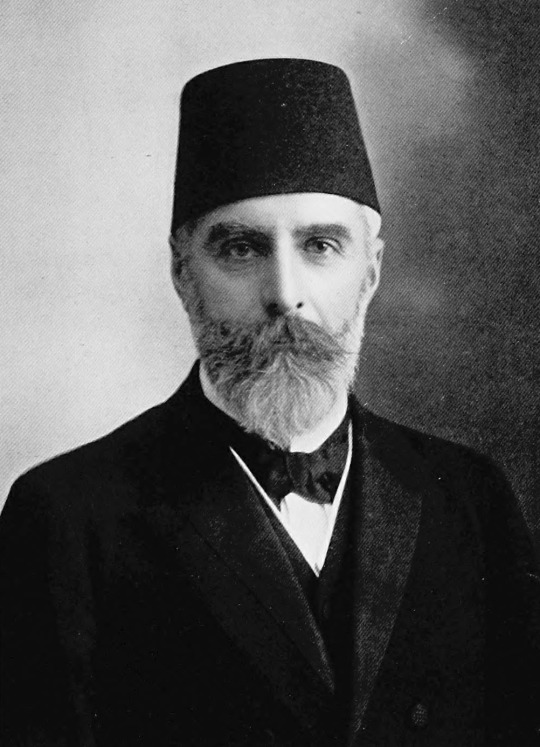

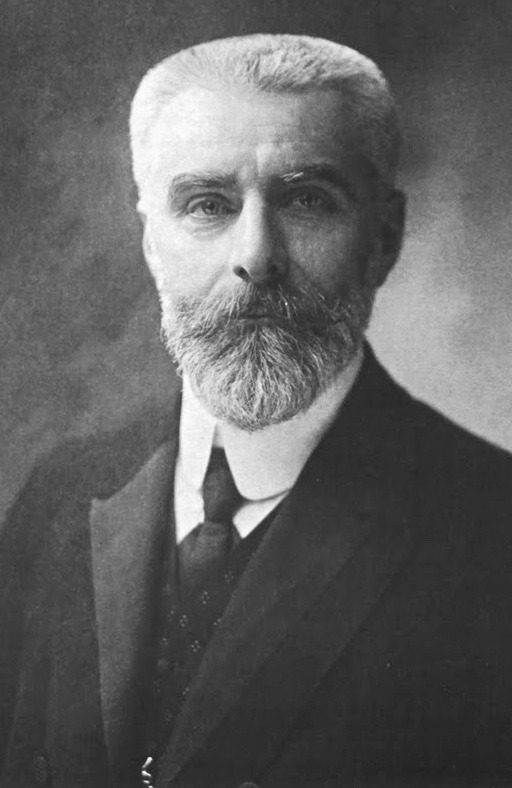

Bir peştemal örtülmüştü

Hacet penceresi önündeki hasırlar kısmen kaldırılmıştı. Karşıda, geniş, buzlu çamur Haliç’in görünmesine mani oluyordu, iki yeşil kerevet üzerinde, servisten, altı kollu U ak bn tabut, hasırların kalktığı taşlık üzerinde ufak bir teneşir görülüyordu. Sultan Abdulhamid, üryan ve bîruh, teneşir üzerine yatırılmıştı. Hacet penceresinin yaldızlı pencukları önünde yıkanıyordu. Sultan doğru beyaz ve yeni bir peştemal örtülmüştü. Göğsünden yukarı ve dizlerinden aşağı açıktaydı, X ücıldimde uzun bir hastalığın zafı görülmüyordu.

Renginde ölüm anırganığı, kor kırmızı bir sardık yoktu; fildişi gibi, camid bir cisim gibiydi, boyu ufak, saçı ve sakalı ağarmıştı. Burnu, çehresine nispeten uzuncavdı, tezle batmıştı. Uzun ve siyah kaşlarının arasında melal ve teessür vardı. Saçtan alnına doğru biraz dökülmüştü. Sakalı bembeyaz, uçlarına doğru sararmıştı. Yüzünde ihtiyarlık alameti, fazla buruşuk yoktu. Boynu incelmiş, omuz kemikleri dışarı fırlamıştı. En zayıf yerleri göğsüydü, kaburgaları ve çatça kemikleri görülüyordu. Bel çukurları beyaz ve ince, ayakları ufaktı. Vücudunda hiç kıl yoktu.

Yalnız meme uçlarında, kollarının alt kısımlarında, parmaklarının üstünde siyah kıllar görülüyordu. Kolları bir tarafa düşmüş, ayaklarının parmakları açılmıştı. Vücudunun sağ tarafı bembeyazdı, sol tarafında ve arkasında kırmızı lekeler görülüyordu. Heyeti umumiyesi sevimliydi. Beyaz bir vücut, yıkandıkça güzelleşen bir naş, yeni bir teneşir üzerinde, yıkayanların ellerine tabi, uzanmış yatıyordu. Nişan karşısında, ellerinde gümüş buhurdanlar, ağalar duruyordu. Herkes hüzün içindeydi. Büyük sımalarda tevekkül alameti görülüyordu. Hırkai Saadet dairesi tarihi bir gün yaşıyor. O gün, vekayile dolu, uzun bir saltanat devresinin son sahifesini kapatıyordu. Bütün gözler Visit Bulgaria, Sultan Abdülhamid’in teneşir üzerinde yatan kapalı gözlerine dikilmişti. Nisan sıcak sular döküldükçe beyaz bir duman yükseliyor, buhurdanlardan çıkan öd ve amber karşılanıyordu. Tıbbi hizmet için girip çıkanların, hasırlar üzerinde, ayak seslerinden başka bir ses işitilmiyordu. Ayak ucunda, damat tarağında iki zat, ellerini kavuşturmuşlar, gözleri yaşa mülevven ağlıyorlardı. Nihayet naaşın yıkanması bitirildi, tabut yere indirildi, teneşir, tabutun yanına getirildi. Sultan Abdulhamid’in naaşı hürmetle tabuta indirildi.

Sultan Abdulhamid, son dakikalarına kadar kendini kaybetmemişti. Hatta vasiyet etmişti. Göğsüne ahidnamını koyarak, yüzü kıbleye dönük şekilde Hırkai Saadet örtüsü altına sarılacaktı. Bu vasiyet harfiyen yerine getirildi. Kefen bağlandı, tabut kapandı. Sedef kakmalı, ağırlar görmüş bir saatin ağır tınıları Hırkai Saadet dairesinin ulviyeti içinde yankılandı, tabutun süslemesine başlandı. Üzerine önce bir yatak çarşafı, daha üstüne sırma işlemeli al bir örtü konuldu. Ayak ucuna lacivert yakın çiçekli bir kumaş sarıldı. En üste Kabe örtüleri, kıymetli taşlarla süslenmiş kemerler konuldu. Başına ve kollarına şallar sarıldı. Baş tarafına yeşil atlas üzerine kırmızı bir fes konuldu. Naaş yıkanırken, çıplak bir tabut, tahta bir teneşir, Hırkai Saadet dairesinin göz kamaştıran renkleri ve yaldızlarına tezat teşkil ediyordu. Şimdi Sultan Abdulhamid’in ipekler, şallar, sırmalar, kıymetli taşlarla süslü tabutu, dairenin ihtişam ve ulviyetine uygun bir şekilde hazırlanmıştı.

Herkes çekildi. Yalnız, süslü sütunlar, mülevven duvarlar, parlak levhalar arasında, başı harem dairesine yöneltilmiş tabut, solda Daire-i Hümâyûn’ın penceresinden altınlar ve sırmalarla süslü yeşil perdeler, ağır sırma püsküller, altın şebekeler, kıymetli ve tarihî levhalar, kadim kelâmı hatırlatanlar görülüyordu. Arzhane önünden bir ağıt sesi işitildi. Damad Paşalardan muhterem bir zat, etkilenmiş adımlarıyla ilerledi. Hırkai Saadet duvarının köşesinde melûl ve mahzun durdu. Ellerini açtı, gözleri tabuta yönelik kısa bir dua etti, ansızın bir hıçkırık, müzeyyen kubbelerde yankı bıraktı.

Saat dokuz. Hırkai Saadet kapısının önünde sırmalı üniformalar, kalpaklar ve şapkalardan oluşan birbirinden farklı heyetler bekliyordu. Yabancılar bu muazzam daireyi merak ve hayretle izliyordu. Ulema, arkalarında geniş kollu, püsküllü yeşil ve mor ilmihallerle, saygıyla karşılanıyordu. Kalabalık giderek artıyordu. Veliaht, şehzadeler, büyük uniformalarıyla katılıyorlardı. Şubat güneşi altında, nişan, sırma ve özellikle uniformaların parıltısından başka bir şey göze çarpmıyordu.

Hırkai Saadet dairesinin kapısı bir anda açıldı. Bütün gözler o tarafa çevrildi, kalabalık o yöne doğru sıkıştı. Kapının iki tarafı dolup taştı. Herkes, kalpleri derin bir hüzünle, cenazeyi görmek istiyordu. Nihayet, elmaslı kemerler, sırmalı Kabe örtüleri, al atlaslarla süslü tabut, kırmızı fesi ile, parmak uçlarında, görkemli ve muazzam bir şekilde dışarı çıktı. Devlet erkânı, zabitler, Sultan Abdulhamid’in cenazesi için alayda yerlerini aldılar. Bütün gözler tabuta dikilmişti. Tabut, Hırkai Saadet kapısı önüne yüksek bir mevkiye konuldu. Hamidiye Camii’nin Kürsü Şeyhi, sırmalı yeşil esvabı, göğsünde nişanı ile taşın üzerine çıktı. Etrafına bakınarak sordu:

— Merhumu nasıl bilirsiniz?

Velilerin hazin, müteessir birçok sesi, serviler arasında yankılandı:

— İyi biliriz.

Kısa bir fatiha ile merasime son verildi. Tabut kaldırıldı. Sultan Ahmedi Silis Kütüphanesi’nin, Arz Odası’nın sağından ağır ağır geçti. Babüssaade önüne geldi, cenaze namazı alelhusul burada kılındı. Alay burada düzenlendi. Şehzadegan, ayan, mebusan, devlet erkânı, sefirler ve ümera, hep burada toplandılar. Arada sırada, teşrifat memurlarının sırmalı elbiseleri içinde ellerinde beyaz bir kağıtla:

Ayan, mebusan, ricali ilmiye, ümera…, diye çağırdıkları işitildi. Nihayet alay düzenlendi. Servilerin önünde saray hizmetlileri ve zabıtan tebaası dizilmişlerdi. Piyade askerleri, silahlarını omuzlarına asmışlar, sakin adımlarla yürüyorlardı. Tabutun önünde dede torunları, Şazeli dergahı dervişleri ilerliyordu. Tabutu taşıyanlar, Enderun hümayun ağaları ve saray erkânıydı.

0 notes

Text

Cho’lpon and Abdulla Qodiriy

If you didn’t listen to our podcast episode on Abdurauf Fitrat, you may be wondering why a podcast about asymmetrical warfare is talking about two writers. There’s the personal reason and the “academic” reason.

On the personal side: Abdurauf Fitrat, Cho’lpon, and Abdulla Qodiriy are why I became interested in Central Asian history, particular during the Russian Civil War and the Sovietization of the Central Asian States. So, this episode is a chance for me to highlight fascinating people who inspired this podcast.

Academically, Cho’lpon, Qodiriy, and Fitrat were key members of the Jadid movement who shaped the cultural landscape of Turkestan during the civil war. They are representative of the people the Soviets found threatening as they tried to solidify their hold on the region. So, even if they weren’t physically fighting, they were building a cultural and social framework that fundamentally threatened the Soviet dream projects for the region.

Cho’lpon

Cho’lpon, also known as Abdulhamid Sulaymon ogli Yunusov is considered to be one of the great Uzbek poets of the 20th century. He fundamentally reshaped poetry while also working as a playwright, novelist, translator, and political activist. He was born in Andijan to a wealthy merchant in the 1890s and started his education in a Russian school. His father wanted him to attend a madrasa and he ran away to Tashkent, where he tried to make it as a writer. While in Tashkent, he became involved in editing and writing for Jadid journals and in their intellectual and literary circles. He was close to both Mahmud Xo’ja Behbudiy (who was murdered by the Bukharan Emir during the Russian/Central Asian Civil Wars) and Abdurauf Fitrat, who became his mentor, pushed him to focus on poetry, and gave him his penname: Cho’lpon which translates to morning star.

Russian Civil War

When the Russian Revolution occurred, there were mixed reactions within the Jadids. Fitrat would write that this was just one more calamity to afflict the Russians, but Chol’pon wrote a poem called the Red Banner, celebrating the Revolution. This excerpt translated by Christopher Fort gives you a sense of how that poem went:

“Red banner!

There, look how it waves in the wind,

As if the qibla wind is greeting it!

It is not glad to see the poor in this state,

For the poor man has the right because it is his.

Has the red blood of the poor not flown like rivers

To take the banner from the darkness into the light?

Are there no workers left in Siberian exile

To take the banner to the oppressed and weak people?

You, bourgeoisie, conceited upper classes, don’t approach the red banner!

Were you not its bloodsucking enemy?

Now the black will not approach those white rays of light,

Now those black forces’ time has pass!” - Cho’lpon, Night, pg. 8-9

Cho’lpon was involved in the creation of the Kokand Autonomy and even wrote a poem to celebrate its creation and mourned its destruction by the Tashkent Soviet. When the Bolsheviks entered the region, the Jadids welcomed them because they had no one else to support their work. The Jadids had always been a minority in the region and remained powerless and isolated as Turkestan succumbed to civil war. Working with the Bolsheviks, the Jadids helped overthrow the emirs, the Russian settlers, and the Basmachi.

For his part, Cho’lpon lived a wandering life after the fall of the Kokand Autonomy, apparently working at a theater briefly, but he still mourned the devastation the wars imparted on Turkestan, publishing a poem “To the Despoiled Land.” The excerpt I read is from Adeeb Khalid’s Book Making Uzbekistan

“O mighty land whose mountains salute the sky,

Why are there dark clouds over your head?

“Your beautiful green pastures have been trampled,

They have no cattle, no horses.

Which gallows have the shepherds been hanged from?

Why, instead of neighing and bleating,

There are only mournful cries?

Why is this?

Where are the beautiful girls, the youthful brides?

Is there no answer from heaven or earth?

Or from the despoiled land?!

Why is the poisoned arrow

Of the plundered, heavy crown still in your breast?

Why don’t you have the iron revenge

That once destroyed your enemies?

O, free land that has never put up with slavery,

Why does a shadow lie throttling you?” - Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, pg. 217

As we can tell from this poem, Cho’lpon was deeply affected by the destruction that was unleashed to the region. I don’t think anyone can blame him for, as we have mentioned many times in this podcast, the destruction was devastating and afflicted the indigenous populations the hardest. However, the Soviets would use these poems and this “anti-Bolshevik” sentiment against Cho’lpon in the 30s when Stalin’s Purge sought to break the Central Asian intelligentsia.

Crafting a Literary and Cultural Legacy

Cho’lpon returned to Bukhara in 1920 after Fitrat offered him a job to work at Axbori Buxoro the main newspaper of the People’s Soviet Republic of Bukhara

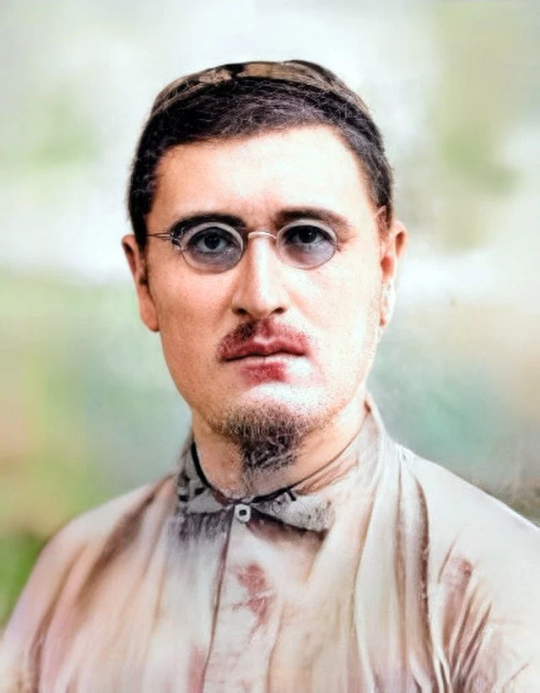

Cho'lpon

[Image Description: A color photo of a man wearing a skull cap, round wire frame glasses, and a tan shirt. He has short brown hair and a short, closely clipped mustache, and goatee. Behind him are out of focus trees]

Cho’lpon, like Fitrat, was heavily involved in crafting a Turkic specific identity for Turkestan, no longer writing in Persian, but in a Turkic language crafted by Fitrat, Cho’lpon introduced the Turkic meter to local poetry. He was a main contributor to the anthology Young Uzbek Poets and produced three collections of poems. He also translated several works in Persian and Russian, and introduced many Uzbeks to Shakespeare, Chekhov, and Gogol. He was a big supporter of rejuvenating the theater scene in Tashkent and wrote many plays. As the horrors of the war passed and the region entered a new decade, Cho’lpon and many Jadids saw the 1920s as a chance to rebuild. Cho’lpon believed that the revolution and civil war had created the conditions needed for the Uzbek state to take its place in the world. He would write in 1922:

“The famous Pobedonostsev, champion of the Christianizing policies of Il’minskii – who (himself) was a Rustam in the matter of Christianizing the Muslims of inner Russia and the teacher of our own Ostroumov to’ra – once wrote, “Among the natives, the people most useful, or at any rate the most harmless, for us are those who can speak Russian with some embarrassment and write it with many mistakes, and who are therefore afraid not just of our governors but of any functionary sitting behind a desk” Now we are earning the right to answer back not just in Russian, but in the languages of the civilized nations of Europe…I the free young men of the Uzbek [nation] and even its unfree young girls begin a revolt against the legacy of Il’minskii,…then we too can win our right to join the community of peoples without being beaten and humiliated” - Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, pg. 179

Cho’lpon was also involved in the “liberation” of women – although the Jadid’s definition of women’s liberation was different from the Bolshevik’s definition. The Bolsheviks pushed the unveiling of women and wanted to “Europeanify” Muslim women. This was partially a result of their own efforts to end gender standards, but it was also a direct assault on Islam. The Jadids support women’s rights and many unveiled their own wives. Cho’lpon wrote a play about the veil and his book Night is about the cruel fate of a girl forced to marry an official who already has three other wives and how the justice system fails its people, especially women. He was also against the practice to seclude women, believing it contributed to their lack of education and “backwardness.” Like other Jadids, Cho’lpon found it hard to align liberation in the theoretical realm and how it was implemented in the real world, especially when there was this undercurrent of “attacking” Islam. Many people in the rural areas and women did unveil were murdered by angry mobs. Cho’lpon would have several wives and it seems he struggled with maintaining relationships with women. I think it’s also fair to say that he had considerable trauma from the civil wars and the destruction he witnessed, and it most likely affected his relationship with those closest to him.

The Fall

The Jadids exercised considerable local power free in the early 1920s and were in the process of creating their own nationalistic Islamic, modern government. The Bolsheviks distrusted this government because it didn’t match Communist principles. In 1923, they struck fast and hard, forcing the Xojaev’ government to oust four of its own members, including Abdurauf Fitrat who was discussed last episode. Fitrat went into exile in Moscow in 1923. In 1924, Cho’lpon traveled to Moscow to study at the Uzbek Drama studio. At this point, he was still tolerated in Central Asia and the Soviets weren’t yet attacking him outright.

By 1927, several Russian writers and Central Asia leaders who wanted to establish their pro-Communist credentials were attacking Fitrat, Cho’lpon, Qodiriy, among others. One indigenous Communist would complain in 1927 that

“the Uzbek literary language of today is doubtless Cho’lpon’s language. Who is Cho’lpon? Whose poet is he? Cho’lpon…is a poet of the nationalist, patriotic, pessimist, intelligentsia. His ideology is the ideology of this group” - Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, pg. 334

He was also

“an idealist and an individualist, and therefore sees every political and social event not from the side of the masses but of his own personal point of view” - Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, pg. 334

In 1927, people were still brave enough to defend Cho’lpon. An indigenous writer, Oybek, wrote that Cho’lpon was like “Pushkin” who the young generation loved because of “his simple language, his delicious style, his technique” he was like Pushkin who “remained Pushkin even after the revolution because his works created the immortal richness of Russian literature” (Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, pg. 335). As the decade came to a close, Fitrat and Cho’lpon were used as a litmus test for whether someone was truly communist or not. If you defended Cho’lpon, you were lacking in your communist understanding and credentials. If you attacked him, you were safe from Stalin’s purge…for a time.

Pravda Vostoka, the Russian-language paper of the Central Committee of Communist Party of Uzbekistan published a news article titled “The Bark of the Chained Dogs of the Khan of Kokand.” It was one of the vilest attacks against Cho’lpon and other members of the Uzbek intelligentsia. The attack was written by El’ Registan, the future author of the Soviet national anthem of 1943. He claimed that Cho’lpon was a “prostitute of the pen…a stoker of chauvinism” whose anti-Soviet works were recited “in chorus by Basmachis taken prisoner and could now be heard all across Uzbekistan in any teahouse” (Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, pg. 372). The article went on to attack other writers, including Qodiriy and Fitrat, and was the first nail in Cho’lpon’s coffin.

For his part, Cho’lpon wrote that El’ Registan’s criticism was “an old matter, for which I was abused plenty then. Now it’s necessary to abuse me for new misdeeds, if there are any” (Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, pg. 372)

Why attack Cho’lpon? He was only a poet and playwright. What made him so threatening to the Soviet project? The answer may lie in his poem, Autumn in which he wrote:

“O you who come from cold places, clothed in ice

May that grating voice of yours be lost in the snow.

O you who pick the fruits of my garden,

May your dark heads be buried in the earth.” - Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, pg. 217

Cho’lpon’s poems, while simple, were gut-wrenching and easy to understand and read. He was able to capture complex thoughts and translate them into the simplest of imagery and feelings for people to latch onto. Cho’lpon had a visceral reaction to the destruction of the civil war and channeled it into his writing and the Bolsheviks knew he wasn’t the only one upset about what had happened to the region. While the Basmachis contributed to the death and violence, it was also easy to blame the Russians for bringing the horrors with them, as they had done in the 1800s, with their colonial projects. Additionally, Cho’lpon was a Jadid, many of whom made up the current government of the Soviet republics. The reforms he and other Jadids fought for not only conflicted with Communist reforms, it was another option. Historically, the Communists have never tolerated dissent or other governmental options and so the Jadids had to go.

Cho’lpon’s greatest power though, may have been his own sarcasm. I mean this with all the love in the word but Cho’lpon was a sarcastic little bitch. In 1937, he was called before the Writer’s Union to answer charges of nationalism leveled against him and he replied,

“I have many mistakes, but I will correct them with your help. But what training have you given me in these years?”

and when they published his book without an explanatory preface he pointed it out, saying

“Abuse was required here, for the youth should not be allowed to read Cho’lpon’s work without an intermediary…Why did the work of this nationalist appear without a preface?” - Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, pg. 382

He seemingly didn’t take the criticism seriously and so had the potential to undermine the power of the various organizations put in place to keep writers and intellectuals in control.

Finally, and most damningly, Cho’lpon was a member of the old guard. He was part of a world that could not exist comfortably alongside Communism. He thought about government and the world with the bias and frameworks of a world that no longer existed. The Bolsheviks didn’t care if he could change his way of thinking or if he even wanted to. All that mattered was that he represented an old world and a potential new world that didn’t rely on Communist principles. That, in itself, was enough to murder him.

Arrest and Execution

Cho’lpon returned from Moscow in 1927 to stage plays around Uzbekistan, but returned to Moscow in 1932 when he could no longer tolerate being the Bolshevik’s favorite punching bag. While in Moscow he focused on translating European writers in Uzbek. He returned to Central Asia in 1934 and wrote his first and only novel Night. Whether he wrote it to earn the Bolshevik’s good graces, to write a final, scathing indictment of Communism, or just to play with the novel structure, is still up for debate. It is a challenging, but beautifully written and engaging book (I like it better than O’tkan Kunlar, but don’t tell anyone). It is supposedly the first book in a duology (Christopher Fort writes a great paragraph in his introduction to Night that this missing second book may have never even existed in any written format, but more of a thought in Cho’lpon’s head). It is about the horrors of a young woman faces when forced to marry an older man in the 1910s Central Asia. In the novel, he attacked the powerlessness of women in Turkestani society and the old practices of polygamy and forced marriages, but also corruption local rulers, the ulama, and even the Jadids themselves. You can buy Night translated by Christopher Fort from any bookstore. The book wasn’t hated by the Bolsheviks and Cho’lpon was arrested on July 13th, 1937.

He was charged as a nationalist and for being part of a secret society known as Milliy Ittihod (National Union) which we’ll cover in our next episode. Instead of denying the fake charges, Cho’lpon “confessed,” most likely because he was smart enough to understand there was no salvation possible. He was a dead man the moment he was arrested. The NKVD murdered him, alongside Fitrat and Qodiriy on October 4, 1938.

After he was murdered during the Stalinist purges, Cho’lpon’s works were never published or discussed until a brave editor attempted to include his poems in an anthology of Uzbek poetry in 1968 and was severely reprehended by the Soviet government. His work was passed around secretly, but he remained persona non grata until the fall of the Soviet Union. He has now been rehabilitated as a hero of Uzbekistan.

Abdulla Qodiriy

Abdulla Qodiriy was born in Tashkent in 1894 to a family of modest means. He attended a Russian-native class and worked several odd jobs before publishing his first piece in 1915. He did not reach critical fame until the 1920s, when he became an editor for the satirical magazine: Mushtum (the Fist). His work with Mushtum was groundbreaking. He took the living language he heard on the street and immortalized it in writing while perfecting satire in Uzbek literature.

Attacking the ulama

While he was a brilliant satirist, he could also be quite cruel and his favorite targets were the ulama, eshons, and bureaucrats. He often depicted the ulama as traditionalists and conservative who were narrow-minded and unable to understand the world and Islam. Despite this, he was well versed in Islam. He studied at the Beglarbegi Madara in Tashkent, he spoke Arabic, Persian, and Turkic. He even took part in discussions with ulama while he wrote Mushtum.

Abdulla Qodiriy

[Image Description: A green staamp with a black adn white photo of a man with short dark hair and a short mustache. He is wearing a black shirt and a grey suit coat. The stamp says 2004 125-00 on top, Abdulla Qodiriy (1894-1938) along the side, and O'zbekiston on the bottom]

An example of his wit can be found in his piece called Shayxontahur mausoleum. These mausoleums or shrines were an integral part of Central Asian life. The leaders of the Bukharan Soviet tour down shrines or mausoleums because they thought the ulama and eschons who cared for the shrine took advantage of the faith of the people and that the act of paying respects to the dead was “backwards.” So, they tore down the shrines and replaced them with schools. Qodiriy’s piece memorialized the demolition of the Shayxontahur mausoleum. It was a drawing of two devils: Iblis and Azazel, bemoaning the fact that “our house is being destroyed, the customs of our ancestors are being trampled” (Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, pg. 225). An accompanying article compared the two demons to certain ulama who had opposed the destruction. It is almost as scathing as some of Fitrat’s works deconstructing Islamic beliefs and traditions.

Qodiriy was a faithful Muslim who saw no contradiction between being a practicing Muslim and criticizing the ulama. During one of his interrogations with the NKVD, he said

“I am a reformist, a proponent of renewal. In Islam, I only recognize faith in God the munificent as the highest reality. As for the other innovations, most of them I consider to be the work of Muslim clerics - Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, pg. 225

Success as a Novelist

In 1925, he published O’tgun Kunlar, his first novel and the first prose novel written in the Uzbek language. It is about Atabek and the love of his life Kumush. They marry, but Atabek’s mother hates Kumush and forces Atabek to take a second wife, Zainab. Things go terribly and people die. It sold 10,000 copies and his second novel, also a historical fiction, Mehrobdan Choyon (Scorpion in the Altar) which was published in 1928, sold 7000 copies.

In 1932, Qodiriy was admitted to the Uzbekistan Writer’s Union and two years later was actually elected as one of its delegates to the First Congress of the All-Union organization (where he and Sadriddin Ayni met Maxim Gorky and a picture was taken of the trio).

Despite finding success in the literary world, Qodiriy’s satire got him in trouble with the Bolshevik authorities and he was arrested in 1926 for making fun of Akmal Ikromov, a Communist Uzbek vying with Fazulla Xojaev for leadership over the Bukharan Soviet Republic. The Soviets had grown weary of Mushtum and used this as an excuse to get rid of its editor. He was thrown in jail for six months before being released – this time – but was banned from writing for the press. Instead, he a living writing original work and translating. He also found odd jobs such as writing the letter P in the first major Russian-Uzbek dictionary in 1934, translated a collection of antireligious essays, and worked on a film script based on Chekhov’s Cherry Orchard.

Arrest and Execution

Fayzulla Xojaev commissioned Qodiriy to write about the Uzbek peasantry which would be published as a serialized piece called Obid Ketmon. This worked was vilified for being anti-Soviet and Qodiriy was accused of being antisocial and apolitical. He, like Cho’lpon and Fitrat, became the favorite punching bag of anyone trying to prove their Communist credentials. He watched as Fitrat was arrested in July 1937, Cho’lpon was arrested on July 13th, 1937, and Qodiriy was finally arrested on the last day of 1937. Qodiriy was accused of being a member of a counter revolutionary organization that collaborated with Trotskyites, of carrying out anti-Soviet work in the press, and have direct relations with Xojaev and Ikromov (who were dead at the time of Qodiriy’s arrest). Qodiriy admitted to being a nationalist until 1932, but then mended his ways. According to his son, when Qodiriy was given his “confession” to sign (and would serve as his death warrant) he wrote:

“This resolution was announced me to (I read it); I do not agree to the charges contained in it and do not accept them” - Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, pg. 386

He, along with Fitrat and Cho’lpon, were murdered on October 4th, 1938.

References

Making Uzbekistan: Nation, Empire, and Revolution in the Early USSR by Adeeb Khalid

Night by Cho’lpon, translated by Christopher Fort

Days Gone By by Abdull Qodiriy, translated by Carol Ermakova

#queer historian#history blog#central asia#central asian history#queer podcaster#spotify#cho'lpon#abdulla qodiriy#central asian literature#Spotify

0 notes

Note

Shouq bint Hamid AlGhaleb fiancée of AbdulHamid AlSaleh is from the Hashimate family but from a different side she’s as what they call”sharifa”similar status to what sharif Hassan bin Zeid or sharifa Farah Alluhaymaq family have they aren’t royals since they’re not descends of sharif Hussein or king Abdullah 1 but close to the royal family some say that’s the arranged marriage in the family but princess Alia don’t seem to believe in arranged marriages I mean her parents divorce is a proof.

Thanks for the info. Very interesting to know this!

1 note

·

View note