#The language you’re using is making it seem like advocating for Arabs not to be killed is just an online activism circlejerk

Note

To answer your tags about that other anon, I think some people have decided to be aggressively indifferent towards the situation. Some of it is a contrarian response to the ‘do this or you are an evil person’ kind of online activism that is popular, and some of it is just a genuine desensitisation and nihilism.

Being so rude like that anon is not acceptable, but online activists do well to remember that some people are allies but simply are not aware of the latest online rules concerning posting about the situation. I have seen many people like that turn off when their humanity is questioned by strangers online for disobeying directives they did not know existed.

Ok I know you think you’re trying to be nuanced about this but I think in typing this you forgot you’re talking about a genocide

#It doesn’t take keeping up with ‘online rules’ (?) to recognize why saying something like that is not only tone deaf but clearly wrong#Youre forgetting that when it comes to genocide the approach really should be binary & people should know better by now#The language you’re using is making it seem like advocating for Arabs not to be killed is just an online activism circlejerk#I don’t appreciate your implication and I think you should evaluate why you decided to be a devil’s advocate in the midst of an ongoing#Genocide#im serious. I think you should evaluate.

27 notes

·

View notes

Link

On the list of America’s irrational fears, Palestine is near the top. This is no small feat for a “country” with no actual territory and a population about the size of South Carolina. Despite its lack of an air force, navy, or any real army to speak of, Palestine has long been considered an existential threat to Israel, a nuclear-armed power with one of the most powerful militaries in the world and the full backing of the United States. Since there’s no military or economic justification for this threat, a more nebulous one had to be invented. Thus, Palestinians are depicted in the media as hot-blooded terrorists, driven by the twin passions of fanatical Islam and a seething hatred for Western culture. So engrained is this belief that the op-ed page of the New York Times can “grapple with questions of [Palestinian] rights” by advocating openly for apartheid, forced expulsion, or worse.

This worldview demands an Olympian feat of mental gymnastics. It can only be maintained so long as most Americans have no firsthand contact with Palestine or Palestinian people. Even the smallest act of cultural exchange is enough to make us start questioning the panic-laced myths we’ve been taught since birth.

Of course, the best way to discover the truth about Palestine is to visit the country yourself, though most Americans don’t have the free time or financial resources to do so (this is not a coincidence). This means that those of us who are fortunate enough to visit have a responsibility to share what we’ve seen and heard, without lapsing into pre-fabricated narratives, even “sympathetic” ones. We can’t fight untruth by telling untruths from the opposite perspective. What we can do, however, is report what we saw and heard in Palestine. We can try to provide a snapshot of daily life and let people come to their own conclusions.

With this in mind, here’s what I learned during a recent trip to the Holy Land…

The Palestinian doorman of the Palm Hostel in Jerusalem is a large and friendly man who insists his name is Mike. My fiancée and I are skeptical, as we’d expected something a bit more Arabic. We ask him what his friends call him.

“Just Mike,” he says, and taps an L&M cigarette against the wooden desk. He’s sitting in a dark alcove with rough stone floors, nestled halfway up the staircase that leads from the fruit market to the Palm’s small arched doorway. A pleasant, musty oldness floats in the air. You could imagine Indiana Jones staying here, if he’d lost tenure and gone broke for some reason. To Westerners like us, it seems too exotic to have a doorman named Mike.

Before we can ask him again, though, Mike pounces with a question of his own. “You’re from the States, right?” He speaks English with a thick accent and slow but almost flawless diction, an odd combination that is causing my fiancée some visible confusion, which seems amusing to Mike. I tell him that we’re from Minnesota, a small and boring place in the center-north of the USA. His grin gets bigger, which makes me self-conscious, so I also explain that Minnesota has no mountains or sea, and the winters are very cold.

“Yeah, I know,” says Mike. “I lived in El Paso for thirty years. Border cop, K9 unit. It was a nice place. Had a couple kids there.” Now it’s my turn to gawk, and I start to race through all the possible scams he might be trying to pull. Mike seems to guess what I’m thinking. “Really. I even learned some Spanish.” He scrunches his brow in mock concentration and clamps a hairy hand over his forehead. “Hola. ¿Como estás?Una cerveza, por favor.” He opens his eyes and laughs. “Welcome to Jerusalem, guys. Damascus Gate is that way. Enjoy.”

I don’t know why I’m so surprised he knows a handful of Taco Bellisms, or why this convinces me of his honesty. However, now it’s impossible to walk away. We have too many questions. The first one: Why’d he return to Jerusalem? Mike looks down at his cigarette, smoldering into a fine grey tail of ash. He flicks it against a stone and a bright red ember blazes to life.

“This is my home. I had to.”

Later, as we sip sweet Turkish coffee outside a rug shop in the Old City, it occurs to me that Mike was the first Palestinian person I’d ever spoken with face-to-face. His life story seemed unusual, but I have no idea what’s “usual” when it comes to Palestinian lives. I’d never thought about them before, to be honest. The world has an infinite number of stories, and the days are not as long as I’d like. It’s not like I’d chosen to ignore Palestine. I just hadn’t chosen to be interested in it.

Which was odd, because Palestine has been all over the news since I was a kid. There isn’t a single specific story I recall, just a murky soup of words and phrases, like “fragile peace talks” and “two-state solution” and “violent demonstrations.” They all swirl together, settling under the stock image of a bombed-out warzone as the headlines mumbled something about Hamas or Hezbollah or the Palestinian Authority. I remember reading about rockets and settlements, refugees and suicide bombers, non-binding resolutions and vetoed Security Council decisions. Not a single detail had stuck. I could feign awareness of some important-sounding events—the Balfour Declaration, the Oslo Accords, the Camp David Summit—but I couldn’t say what decade they happened, or who was involved, or what was decided.

For years, I’d been under the impression that I knew enough about Palestine to be uninterested in what was happening there. This isn’t to say I felt any particular animosity toward the Palestinians. But it’s impossible to fight for every cause, no matter how righteous, if only for reasons of time. Every minute you spend feeding the hungry is a minute you’re not visiting the sick. Life is a zero sum game more often than we’d like to believe.

As we headed toward the Via Dolorosa, the road that Jesus walked on the way to his crucifixion, I began to feel uneasy. The Israeli police (indistinguishable from soldiers except for the patches on their uniforms) who stood guard at every corner still smiled at us, and they were still apologetic when they forbade us from walking down streets that were “for Muslims only, unfortunately.” Their English was excellent. Many of them were women. They were young and diverse and photogenic, a recruiter’s dream team. But all I could see were their bulletproof vests and submachine guns. Above every ancient stone arch bristled a nest of surveillance cameras. Only a few hours ago, I’d been able to block all that from my sight, leaving me free to enjoy the giddy sensation of strolling through the holiest city on earth.

The road ended at the Lion’s Gate. Just as we approached it, a battered Toyota came rattling through. It screeched to a halt and a squad of Israeli police surrounded the car. All four doors opened and out stepped a Palestinian family. The driver was a young man in his 20s, with short black hair cut in the style of Ronaldo, the famous Real Madrid footballer. When the police told him to turn around and face the wall, he did so without a word. It was obvious this was a daily ritual. The policeman who frisked him looked as bored as it’s possible to look when patting down another man’s genitals. Soon it was over, and the family got back in their car. One of the policemen pulled out his phone and started texting.

If I’d made a video of the search (which I didn’t) and showed it to you with the volume off, you probably wouldn’t find it very interesting. The Israeli police didn’t hurt the man, and he barely made eye contact with them. There were no outrageous racial slurs or savage beatings. The only thing you’d see is a group of people in camouflage battle gear standing around a small white sedan, with a middle-aged woman and a couple of young girls off to the right. Unless you have hawk-like eyesight and an exceptional knowledge of obscure uniform insignias, I doubt you’d be able to tell “which side” any of the participants might be on. All you could say for sure is that the police wanted to search the family’s bodies and belongings, and the family looked very unhappy about it, but the police had guns and cameras, and that settled things. It’s interesting what conclusions different people might draw from a scene like that.

Later that night, after we get back to the Palm, I tell Mike about what we saw. He asks what we’d thought. “It was fucked up,” we say.

Mike sighs. “You should see Bethlehem.”

Jerusalem is so close to Bethlehem that you barely have time to wonder why all the billboards that advertise luxury condos use English instead of Arabic as the second language before you arrive at the wall.

The wall is the most hideous structure I’ve ever seen. It’s a huge, groaning monument to death. Tall grey rectangles bite into the earth like iron teeth, horribly bare, cold, sterile, a towering monstrosity. The wall makes the air taste like poison.

We’re in the car of Mike’s cousin Harun, who is Palestinian, but his car has Israeli plates so we aren’t searched at the checkpoint. We inch past the concrete barriers and armored trucks. Harun holds his identity pass out the window, a soldier waves us through, and a few seconds later we’re in Bethlehem, a short drive from where Jesus Christ was born. It feels like entering prison. I don’t say prison in the sense of an ugly and depressing place you’d prefer not to visit. I say prison in the literal sense: a fortified enclosure where human beings are kept against their will by heavily armed guards who will shoot them if they try to leave. This is what modern life is like in Bethlehem, birthplace of our Lord and Savior.

Looking at the wall from the Israeli side breaks your heart because of its naked ugliness. On the Palestinian side, the unending slabs of concrete have been decorated with slogans, signs, and graffiti, which break your heart for different reasons. One of the hardest parts is reading the sumud series. These are short stories written on plain white posters, plastered to the wall about 10 feet up. Each story comes from a Palestinian woman or girl, and most are written in English, because the only people who read these stories are tourists.

One in particular catches my eye, by a woman named Antoinette:

All my life was in Jerusalem! I was there daily: I worked there at a school as a volunteer and all my friends live there. I used to belong to the Anglican Church in Jerusalem and was a volunteer there. I arranged the flowers and was active with the other women. I rented a flat but I was not allowed to stay because I do not have a Jerusalem ID card. Now I cannot go to Jerusalem: the wall separates me from my church, from my life. We are imprisoned here in Bethlehem. All my relationships with Jerusalem are dead. I am a dying woman.

The flowers are what gets me, because my mother also arranges flowers at church. Hers is an Eastern Orthodox congregation in Minneapolis, about 20 minutes by car from my childhood home. That’s about the same distance between Bethlehem and Jerusalem, although there aren’t any military checkpoints or armored cars patrolling the Minnesotan highways. Until today, I would’ve been unable to imagine what that would even look like. The situation here is so unlike anything I’ve ever encountered in real life that all I can think is, “it’s like a bad war movie.” For the Palestinian people who’ve been living under an increasingly brutal military occupation for the last 70 years, an entire lifetime, I can’t begin to guess at the depths of their helpless anger. What did Antoinette think, the first time the soldiers refused to let her pass? What did she say? What would my mother say? There wouldn’t be a goddamned thing she could do, or I could do, or my father or my sisters, or anyone else. We’d all just have to live with it, the soldiers groping us, beating us, mocking us. No wonder Antoinette gave up hope. In her place, would I be any different? We walk in silence for a long time.

We end up in a refugee camp called Aida, where more than 6,000 people live in an area roughly the size of a Super Target. Here, the air is literally poison. Israeli soldiers have fired so much tear gas into the tiny area that 100 percent of residents now suffer from its effects. If they were using the tear gas against, say, ISIS soldiers instead of Palestinian civilians, this would be a war crime, since “asphyxiating, poisonous, or other gases” are banned by the Geneva Protocol. However, such practices are deemed to be acceptable in peacetime, since there’s no chance an unarmed civilian population would be able to retaliate with toxic agents of their own. Without the threat of escalation, chemical warfare is just crowd control.

Before we continue, there are three things you should know about Aida. The first is that there’s no clear dividing line between Aida and Bethlehem, so an unwary pedestrian can easily wander into the refugee camp without realizing it. The second thing is that it doesn’t look like a refugee camp, at least if you’re expecting a refugee camp to be full of emergency trailers, flimsy tents, and flaming barrels of trash. The third thing is that the kids who live there have terrible taste in soccer teams.

We meet the first group as soon as we enter the camp. There are five of them, all teenage boys. One of them is wearing a knockoff Yankees hat. They’re staring at us, and at once I’m very aware of my camera bag’s bulkiness and the blondeness of my fiancée’s hair. A loudspeaker crackles with the cry of the muzzein, and it’s only then that I realize how deeply we Americans have been conditioned to associate the Arabic language with violence and death. The boys exchange a quick burst of words, raising my blood pressure even higher, and cross the street toward us.

“Hello… what’s your name?” The kid who speaks first is tall and stocky, wearing the same black track jacket and blue jeans favored by 95 percent of the world’s male adolescents. He’s also sporting the Ronaldo haircut, as are several of his friends. Two of the kids start to pull out cigarettes, so I pull out my cigarettes faster and offer the pack to them. Is this a bad, irresponsible thing to do? Sure, and if you’re worried about the long-term health of these kids’ lungs, you should call the American manufacturers who supply Israel with the chemical weapons that are used to poison the air they breathe every day.

I tell the kid my name is Nick, and he shakes my hand. “Nice to meet you. I’m Shadi.” He’s carrying a rolled-up book, as are his friends, so I ask if he’s going to school. “Yeah bro, exams. We have three this week.” His friends laugh, and then engage in a quick tussle for the right of explaining that they’re heading to their math exam now, which is a boring and difficult subject, and I agree that it is, although at least you never have to use most of it after you finish school, a sentiment that earns me daps from Shadi and his friends, and we stand there giggling and smoking on the street corner of the refugee camp, though for a few moments we could be anywhere in the world.

My fiancée and I, both teachers by trade, start to pepper the kids with questions. Shadi says that he has one year left at the nearby high school, which is run by the UN refugee agency that was just stripped of half its funding by Trump. After he finishes, he plans to study at Bethlehem University. The other guys nod with approval, and speak of similar hopes. I ask them who their favorite footballer is, and they all say Ronaldo, at which I spit in disbelief, because everyone knows that Ronaldo sucks and Messi is much better, visca el Barça! Shadi and his friends break into huge grins, since few elements of brotherhood are more universal than talking shit about sports. Seconds later we’re howling with laughter as Shadi’s buddy makes insulting pantomimes about Messi’s diminutive size. A small part of my brain is loudly and repeatedly insisting that everything about this moment of life is batshit lunacy, that there’s no reason why I should be standing in a Palestinian refugee camp, yards away from buildings my country helped bomb into rubble, with my pretty fiancée and expensive camera, talking in English slang with a group of boys whose lungs are scarred with chemicals made in the USA, the exact kind of reckless young ruffians whose slingshots and stones are such a terrifying threat to the fearsome Israeli military, and the craziest thing of all is that here in the refugee camp, surrounded by derelict cars and rusty barbed wire and 6,000 displaced Palestinians, we are not in danger, at least not from whom you’d think. Here, in the refugee camp, we can joke around with people who speak our language and know our cultural references and actively seek to help us navigate their neighborhood. None of this is to say that Aida is a safe, comfortable, or morally defensible place to put human beings, but only that the people who live there treated us with such overwhelming kindness and decency that I have never been more ashamed at what my country does in my name. I tell Shadi and his friends to take the rest of my cigarettes, but they smile and decline.

“We, uh, have to go now,” says Shadi, as his friends start to walk up the street. “Do you have Facebook?” We do, because everyone does, and as we exchange information, I wish him good luck on his math exam. “No way, bro, I suck at math,” he says. We both laugh, and I pat him on the back.

“Fuck math. But hey, you’re gonna do great, Shadi.”

“Thanks bro. Fuck math.”

I hope he gets every question correct on his exam. I hope he goes to university and wins a scholarship to Oxford. I hope he invents some insanely popular widget and it makes him a billion dollars and he never has to breathe tear gas again.

We continue walking through Aida camp. The buildings are square, ugly, and drab, but the walls are decorated with colorful paintings of fish and butterflies and meadows (along with a somewhat darker array of scenes from the Israeli military occupation). We meet a group of cousins, aged four to 10, all girls, who ask if we can speak English. When we offer them a bag of candy, they take one piece each, and run away yelping when a man limps out the front door of their house. “Thank you,” he says, his face a mask of grave civility. Cars, all bearing green-and-white Palestinian plates instead of the blue-and-yellow Israeli ones, slow down so their drivers can shout “Hello!” We meet another group of kids, boys this time, who grab fistfuls of candy and make playful attempts to unfasten my wristwatch. We make a hasty retreat from this group. The streets are scorched in spots where tear gas canisters exploded. Narrow strips of pockmarked pavement lead us down steep hills and into winding alleys, and soon we’re lost.

This is how we meet Ahmed. He’s a tall man, about 40 years old, with a small black mustache and arms as thin as a stork’s legs. A yellow sofa leans against the concrete wall of the three-storey apartment building where he lives. Ahmed is sitting there with an elderly couple. He asks if we’d like a cup of tea, and although we’ve been warned about the old “come inside for a cup of tea” scam, we accept his offer. The elderly couple greets us in Arabic, and I try not to notice the large plastic bag of orange liquid peeking out from beneath the old man’s shirt.

While we climb the stairs to Ahmed’s apartment, he tells us that the old people are his parents. “They live here,” he says, pointing to the door on the first floor, “because they don’t walk very good. My mother has problems with her legs, my father is sick from the water.” He traces the pipes with his finger, and we see they’re coated in a thick reddish crust. “Here is the home of my big son,” he says when we reach the second floor. “He has a new baby.” We congratulate him on becoming a grandfather. “And I have a new baby, too! Come, I show you!” One more flight of stairs, and we arrive at Ahmed’s apartment.

It looks remarkably similar to a hundred other apartments we’ve visited. Framed photos of various family members hang on the living room walls, which are painted the same not-quite-white as most living room walls. There’s a beautiful red rug and a small TV. A woman is sitting on the sofa, nursing a baby as she folds socks. “My wife,” says Ahmed.

She speaks a little English too, and says that her name is Nada. She has a pale round face and long black hair. Her eyes are soft, kind, and completely exhausted. Yet if she’s annoyed or embarrassed by our presence, she doesn’t show it. She just hands the baby to Ahmed and goes to make the tea.

“I’m sorry for my house,” says Ahmed, cradling his son like a loaf of bread with legs. “We try to be clean, but…” There’s not so much as a slipper out of place, but I know what he means. “We rent this flat. And my son, and my parents. All rent. Before we have a farm, animals, olive trees, but now, we rent.” I ask about his job. He smiles and shakes his head. “I want a job,” he says, “I love to work. With my hands, with my mind. I love to work. But here, haven’t jobs.” For a second he looks like he’s going to continue this line of thinking, but he stops himself. “I help my wife, that is my job.” Ahmed laughs and passes his baby to my fiancée. “And he, he helps in the home?” She demurs while I protest in mock indignation. I do the dishes every morning before she even wakes up! Still laughing, Ahmed rubs his shins, and again it’s easy to forget we’re sitting in a refugee camp in Jesus’ hometown.

Then the baby wheezes. It’s a dry, scratchy wheeze. Ahmed squirms in his seat, looking embarrassed. The baby begins to cough. My fiancée rubs his back as the coughing turns wet and violent. Machine gun explosions blast from his tiny lungs. As an asthmatic, I recognize the sound of serious sickness. The baby writhes in my fiancée’s lap, struggling to breathe. He’s gasping and it’s getting worse fast. At moments like these, personal experience tells me that a nebulizer can be the difference between life and death. I don’t insult Ahmed by asking if he has one, because it’s clear that he doesn’t. All I can do is rub the boy’s chest with my finger, a stupid and useless massage. He kicks and stretches as if trying to wiggle away from the unseen demon that’s strangling him.

Nada hurries back with the tea. “I’m sorry,” she says, picking up the baby. She coos to him in Arabic and rubs his back, both of which are comforting but neither of which can relax the inflamed tissues of her infant’s lungs. “My baby…” Unable to find the words in English, she looks to her husband.

Ahmed rubs his cheek. “When she is pregnant, one night the soldiers come. They say the children throw stones. They always throw stones. So the soldiers shoot gas in all the houses. In the windows, over there.” His voice gets quieter. “And she is very sick. When the baby is born, he is sick too.” I ask him if it’s possible to find medicine. “Sometimes yes,” says Ahmed, “but very, very expensive.” For the first time, there’s a note of frustration in his voice. “Everything is expensive here. You see this,” and he picks up a pack of diapers, “it cost me thirty shekels. 10 dollars, almost. And the baby needs so many things. It is impossible to buy. I haven’t money for meat, how can I buy medicine?” He points to a plastic bag with four small pitas. “This is our food. One bread for my two sons, and two breads for my wife. She must make milk for our baby.” When I ask him what he eats, he holds up his cup of tea.

Somehow Nada has soothed the baby out of danger. His breathing is almost normal again, just a quiet raspy crackle. She’s still staring at him, her big brown eyes wide with worry. I don’t know how many times she’s done this before. I don’t know how many times are left before her luck runs out.

Somehow she’s keeping her baby alive with nothing but the sheer force of her love. I ask to use the toilet so I don’t have to cry in front of her.

(Continue Reading)

#politics#the left#current affairs#foreign policy#long article#long reads#worth it#Israeli Occupation#freepalestine#apartheid

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

I had a major clash with the staff of our literary journal today. I accused them, maybe a bit impulsively, of reifying neocolonialism through a pretty strict focus on the contemporary Western aesthetics of poetry. Like, our journal literally has the word "International" in it, and we made the conscious decision to brand ourselves as an international journal. And yet, our first issue was almost entirely American, with a smattering of some European writers. And here we are again, about to finalize our second issue with almost an exclusive focus on the most recent aesthetic trends of the "western" literary tradition. It’s all wonderful writing, but it’s also very monolithic.

We just received a selection of some translations of absolutely breathtaking poems by a Djibouti poet--one of the most renowned and respected in his tradition--and by a translator equally as respected. And almost the entire staff voted to reject them because they couldn't see or appreciate their value. Their only framework for consuming poetry comes from the contemporary American tradition; like they've simply never been exposed to other poetries, other trends, other aesthetics, and it's quite possibly the least-international framework from which to operate.

The thing that far too many readers and writers of modern English poetry (and prose, for that matter) seem to not understand is that contemporary American poetry, like poetries elsewhere, is marked by conventions and shibboleths that shape what we consider good poetry to be. For those raised on the conventions of American poetry, it can be tempting to see these conventions as inevitable or "right" rather than as culturally-contingent, and therefore it can become tempting to use these specifically modern, American conventions to judge other poetries--even those that have very different, equally as culturally-contingent sets of conventions. Many "non-Western" traditions (the various African poetries, Middle Eastern, etc) are much more tolerant of and interested in certain qualities; abstraction and sentiment, for instance, while shunned and seen as weak and inferior in contemporary American poetry, is celebrated. Consider these lines:

perdu dans le labyrinthe bruyant de son propre temps

il donne des noms à tant de choses

en témoignent les seins nus des étoiles

lost in the noisy maze of his own time

he gives names to so many things

beneath the bare-breasted stars

That last line as a reference to the double star in the constellation Cassiopeia? Holy shit it's so beautiful, and a perfect example of the poetics of heavenly bodies so common in Middle Eastern, North African, and Franco-Arabic poetry. But in contemporary American poetry it's seen as abstract, flowery, grand. Take one fucking poetry workshop and you'll quickly see what I mean. If you're not writing about the banality of common credences in American middle-class life--about the Pringles can bought for $2.89 at Harry's Corner Store (literally the line of a poem many people praised)--you're not writing good poetry.

In fact, there are so many dominant trends in modern American poetry that I find extremely troubling: the backlash against ethnic poets or the complaint that some poems are "too ethnic." The continuing distrust of imaginative and surrealist poetries. The general inability or refusal to think in terms of "poetries" rather than poetry, which would make our small neighborhood a bit larger, a bit better, a bit richer. Other traditions outside our own value the earthiness, the visionary, the need to speak of the deep winds, both light and dark, that roar around the heart with the voices of our ancestors. Where is this in our poetry? It’s workshopped the fuck out, that’s where.

It's also particularly telling that the staff of our literary journal is almost exclusively populated by English-only poets and fiction writers, and a few translators working almost exclusively within Romance languages. As a translator of Arabic poetry, and as someone who both reads this tradition of literature and writes from its inspiration, I'm currently the only exception. We have a Japenese translator on our staff, but he's been one of the biggest advocates for purging all of our submissions from things that seem "too foreign." He also fetishizes linguistic prescription, so.

And all this would be okay(ish) if we were just a literary journal without the pretense of being "international." I mean it still wouldn't be okay, but it's certainly not okay to position and promote ourselves as celebrating the international voice while simultaneously working to silence or homogenize it. That's textbook neocolonialism. And it's incredibly harmful. It's no small gesture to simply pass on poetries that don't fit a particular curated aesthetic; when you're building your journal as one of the few truly international journals, and you're only accepting a particular aesthetic, writers desperate for publication, who write from other traditions and with different aesthetics, will begin to modify their writing until it's publishable by these myopic contemporary western standards. And that pushes back against everything that poetry should stand for, now more than ever.

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

New Year, New-robi

Hello again rafikis,

Thanks for following my journey so far!

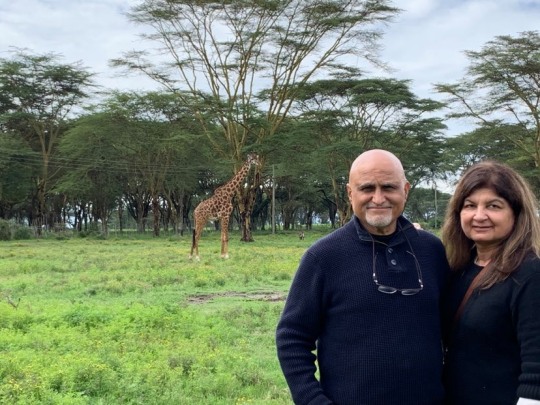

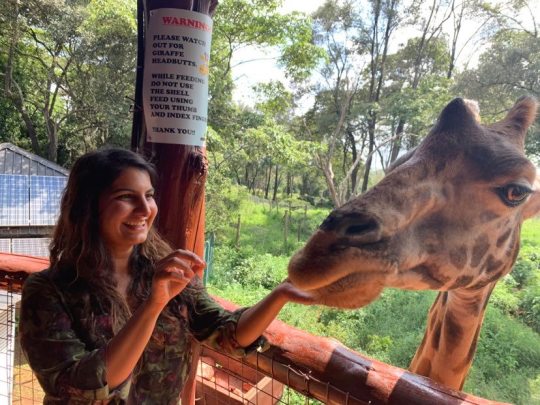

Although it feels like 2019 was yesterday, I’m about to ring in my 5-month anniversary here in Nairobi. Over the past couple of months, I’ve been lucky to welcome several visitors to this great country, spend more time in rural communities and local watering holes (not literally #TIA), and even just get accustomed to a mundane daily routine in this exoticized place where I used to be a wide-eyed visitor. All of this has helped me see Nairobi through new eyes and given me greater perspective on this fascinating metropolis.

Even if my observations aren’t any more insightful, I’m hoping that, at the very least, my Swahili has improved after spending a few months here. Although I won’t lie, most of these sayings are from the interwebs (except the last one which is a Papa Jamal classic).

1. Umoja ni nguvu: Unity is strength

For anyone who has moved from a small rural town to a big urban city, you’ll know that one of the most noticeable differences is the level of diversity - in race, language, income levels, religious beliefs, political views, food, fashion, architecture, you name it… and often, this diversity is unfortunately correlated with conflict, violence, or a clash of civilizations.

Countries in Africa tend to benefit (or suffer) from this diversity inherently, thanks to the colonial legacy of how land was divided on the continent. Homogenous tribes and cultures were separated by borders arbitrarily drawn by European colonialists, creating some of the most ethnically diverse countries in the world. Nairobi, being a large, cosmopolitan African city, embodies this diversity on many levels: not only through a mix of Kenyan ethnicities, cultures, and perspectives, but also a smattering of the colourful mosaic of people who have immigrated here from across Africa and the rest of the globe.

At the risk of sounding like I’m making a political statement, which I am certainly not qualified to do yet, I would say that these diverse groups seem to live here in relative harmony. I wouldn’t go so far as saying Nairobi is safe - pretty much everyone who lives here has a story about a robbery or mugging (myself, unfortunately, included). However, given that its bordering nation, Somalia, known to be one of the most homogenous in Africa, has suffered from decades of unrest and infighting, you could conclude that greater diversity does not necessarily mean greater conflict.

Gaining a deeper understanding of Nairobi’s complex history has helped me untangle the resulting tapestry of cultures that has developed here over time, from large Bantu tribes like the Kikuyu, to the not-so-lovingly-named Kenyan Cowboys who remained here since the British rule, to the Indian ancestors of the railway labourers brought over by the Brits, the Arab traders who moved inland from the Swahili coast, to the more recent Chinese settlements that have formed as a result of their investments in infrastructure. Interacting with a broader range of communities here has given me a more nuanced perspective on the divergence between conservative and progressive opinions on religion, politics, gender roles, relationships, sexual orientation, family structure, and values that exist in this city. At the same time, I’ve been fortunate to experience the culture and creative expression that blossom from this juxtaposition of traditional and edgy, in the form of music, art, comedy, and dance, while also revelling in the ability to flip seamlessly from nature reserve to bustling city a heartbeat and switch between wellness retreat to raging nightlife within just a short Bolt ride. Though diversity can be seen in all flavours and colours here, Nairobians prosper by recognizing that there is more strength in unity than conflict.

2. Adui wa mtu, ni mtu: The enemy of man is man

Of course, it’s not all sunshine and rainbows here (in fact, the rains had been non-stop for months!) - you can’t have a conversation about Kenyan life without addressing the vast inequalities and corruption that exist. For the billions of dollars invested in the country through grants, foreign aid, and impact investment, there are still gaping holes in infrastructure, healthcare and education that are yet to be tackled. It seems that politicians, public officials, donors, investors, and aid workers might be getting in their own way when it comes to making significant progress on the systemic issues that plague the country. The war on corruption makes daily headlines here yet many parts of policy making, procurement, regulation, and enforcement are driven by political agendas and misaligned financial incentives.

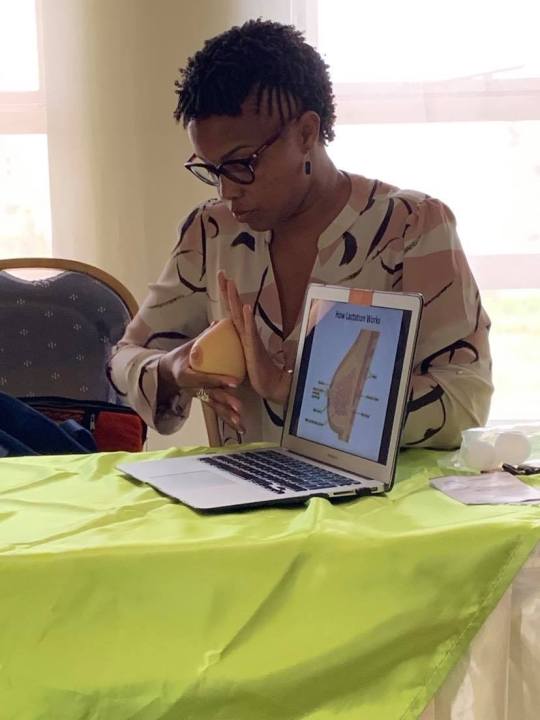

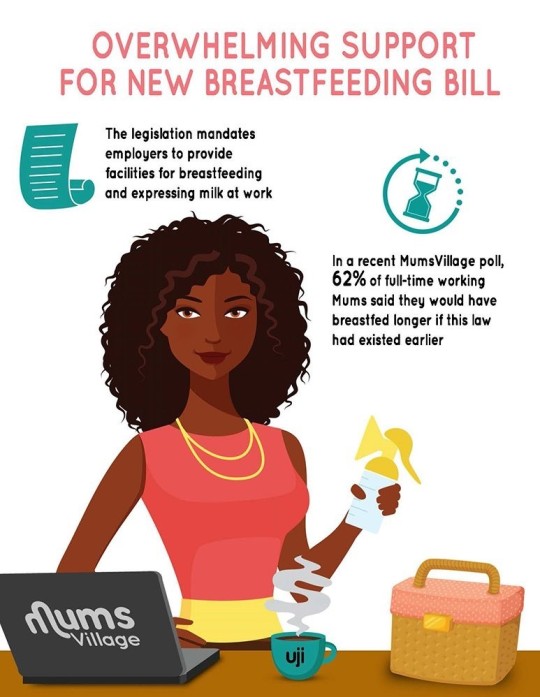

Even policy efforts that I generally support can by driven by a politicized PR angle. For example, Kenya’s ban on plastic bags, known to be the toughest in the world, took 10 years to implement and enforce successfully. While this policy has made a significant impact on waste management, animal health, and overall environmental protection, it was championed by a highly publicized race for implementation among East African governments. One could argue that the ends justify the means, now that 24 African countries have successfully banned plastic bag use, until you step back and consider the greater threats to environmental conservation like the widespread use of diesel fuel or practices like trash burning that are still prevalent in these countries. Similarly, and closer to home for me, much fanfare has been made about maternal employment and breastfeeding policies in local media, now that all employers are required to provide a lactation space for new mothers. However, due to their non-existent enforcement strategy, only 40 companies across Kenya have actually created lactation rooms so far.

While these political concerns may seem lofty, they can become significant considerations in making career choices and conducting daily life in this country. To commercialize a new breast pump in this market, I know I’ll need a well-connected network that spans government, regulatory bodies, distributors, retailers, healthcare providers, and key opinion leaders to counter the inevitable pressure to comply with the bribery and bureaucracy that often infiltrates these sectors. Many of the industry conferences I’ve attended aim to tackle these challenges by crowd-sourcing solutions within the community or, at the very least, encouraging key players not to concede to this systemic corruption.

On a daily basis, while it’s impossible not to confront your privilege as a foreigner living here, it is also difficult to know how to maximize your positive impact: do you donate to your favorite charity, give cash directly to the people begging on the street, volunteer for programs in the informal settlements, or advocate for further policy change and enforcement through your network? The complex system of incentives and unintended consequences make it impossible to calculate the net impact of your every action. Organizations like “Give Directly” have extensive research on the positive impact of unconditional direct cash transfers to individuals living in extreme poverty, which eliminate the potential bureaucratic redundancies of social interventions targeted at these communities. My personal conclusion is that as long as we aim to ensure that man does not become the enemy of his own good intentions in these efforts, we can work towards making a net positive social impact.

3. Haba na haba hujaza kibaba: Little by little fills the pot

Whatever qualms you might have with Kenyan society, if there’s one thing you can commend Nairobians for it’s their hustle. Everyone from your housekeeper to your manager is likely rocking a side-gig, whether its delivering Jumia orders or semi-professional stand-up comedy. Before Nairobi became a hotbed for entrepreneurship and terms like ‘impact investing’ were even invented, Kenyans had been pitching tents to sell their farm’s produce on the street and exporting their handicrafts around the world. Since then, strategic public and private sector efforts have continued empowering these entrepreneurs; for instance, through significant investments in enabling technology such as mobile payments.

All that to say, when it comes to innovative ideas and self-employment, I have known Nairobians to be extremely optimistic and perseverant. Which is why I am always pleasantly surprised to hear those three words that every girl dreams of, after I describe my business to any Kenyan: “It will work.”

This simple phase hits on a very special insight that is an important ingredient in the makings of every entrepreneur: an unabashed optimism that things will work out. And if they aren’t quite working yet, it’s only a matter of time and hard work until they do. Little by little, we will all get where we need to go.

When you are starting to build the foundation of a business and testing the assumptions that are the basis of your idea, this type of encouraging and frequent reassurance can make a world of difference. While it’s important to be realistic, or even borderline cynical, about the positive market feedback you receive in contrived research settings like focus groups, sometimes it’s just nice to take a moment and indulge in some external validation from a total stranger that you’re not totally out of your mind - “it will work”.

And this is the way we all support each other and survive here in our little bubble of dreamers and doers. Things are not always easy and sometimes you bump into cultural clashes or politics and bureaucracy, but these are all just hurdles in the rat race that we idealists happily skirt around in pursuit of our nobler ambitions. Knowing that we are all hustling and working towards the same broader goals, we gladly go out of our way to lend a hand, partner with each other, subsidize our services, and give free advice. Despite not living in an affluent country, people here are rich with positivity, tenacity, and generosity.

Asanteni sana! Until next time,

Sahar

0 notes

Text

Eddie Izzard:’ Everything I do in life is trying to get my mother back’

Transgender hero Eddie Izzard has done standup in French and German, guide dozens of marathons, and is now in a period drama with Judi Dench. But, he divulges, his can-do position has a melancholy source

There was a literal turning point in Eddie Izzard’s lifelong pursuit of personal freedom. It came one afternoon in 1985 when he had gone out for the first time in a dress and ends and full makeup down Islington high street. He was 23 and “hes been” contriving- and evading- that minute for just about as long as he had been able to remember. The turning point came after he was chased down the road by some teenage girls who had caught him changing back into his jeans in the public toilets and wanted to let him know he was weird. That seek purposed when eventually, faced with the screamed doubt” Hey, why were you garmented as the status of women ?”, he ended simply to stop running and pas and explain himself.

He spun around to give an answer, but before he got numerous words out the girls had run in the opposite attitude. The experience schooled him some things: that there was ability in meeting fright rather than eschewing it; and that from then on he would never let other beings define him. After that afternoon, he says, he is not simply felt he could face down the things that feared him, he went chasing after them: street perform, standup slapstick, marathon operating, political activism, improvising his stage show in different languages- all these things detected relatively easy after that original coming out as what he calls” transvestite or transgender “.” You recollect, if I can do something that hard, but positive- perhaps I can do anything .”

The ” anything” he has been doing most recently is to take over the challenges facing playing opposite Judi Dench and Michael Gambon. In Stephen Frears’s interpretation of the real fib of Queen Victoria’s late-life relationship with an Indian servant, Victoria& Abdul , Izzard plays a full-bearded, tweed-suited Bertie( later Edward VII ), reining in his comic impulses to occupy the scandalize and scheming of a son accompanying his mother apparently making a buffoon of herself. Izzard has done abundance of cinemas before- he was in Ocean’s Twelve and Thirteen alongside George Clooney and Brad Pitt and the rest- but good-for-nothing that has required fairly this level of costume drama imprisonment. He loved it.

Watch a trailer for Victoria& Abdul .

He and Dench are old friends. She has been a regular at his stage shows and has been in the habit, for reasons forgotten, of sending a banana to his dressing room each opening night, with” Good fluke !” written on it. Discovering her path Victoria at close quarters was a daily masterclass. The cinema was shot partly at Osborne House on the Isle of Wight( the first time any cinema crew had been allowed inside by English Heritage) and the throw would give their mane down in the evenings. One hour, Izzard recalls:” I was dancing with Judi to Ray Charles’s’ What’d I Say ‘. She felt like a young woman, a young teenage girlfriend nearly. Judi has this amazing activated of vitality that traces all the way back to her youth .”

Watching the movie, you’re so ready to see Izzard slip into one of his rebellious moves of consciousness that for a while it seems odd that he stays on dialogue. Does it feel that lane to him more?

” Not now ,” he says.” My early effort as an actor wasn’t very good because I merely swopped all my slapstick muscles off, and I didn’t know what to replace them with. I guess I have learned more how to just’ be’ on movie now. It is just like knowing how to both razz a bicycle and drive a car. If you are in a car you don’t want to lean sideways to turn a reces. You know the difference .”

Ever since he bunked off institution and conned his way into Pinewood Studios as a 15 -year-old and wandered the film sets for a epoch, he has imagined himself an actor. The first thing he did when his humor finally taken away from after years of trying and often is inadequate to acquire people laugh was to get himself a drama agent and see if he could haunt a twinned career. He has never been satisfied with precisely doing one thing, and it is suggested that determination to diversify has only grown. He’s 55, and because of his running- which peaked at 43 marathons in 57 daytimesin the UK and 27 in 27 daylights in South africans for Sport Relief– he appears lean and almost alarmingly bright-eyed. We are talking in a inn chamber in London, and he is garmented sharply in” son with eyeliner” mode. He works on the notion, he says, that human beings were never made to sit still or decide, but to place themselves in defying places, and then work up how to cope.

” World campaign two is an excellent example ,” he advocates.” People went descent behind enemy lines with no suggestion of what they were going into. They had to learn to do a great deal under extreme pres and on the move. And they substantiated we are able to. In a most varied mode, I guess coming out as transgender allowed me to put myself in other frightening situations and labor them out formerly I was in them. I knew I would get through the bad, terrifying bit- and there was a lot of that when I was a street performer- and eventually get to a more interesting place .”

Loping one of many marathons for Sport Relief in July 2009. Photograph: Alfie Hitchcock/ Rex

He has, of late, paused to reflect on the motivations behind that compulsion, firstly in a documentary film, Believe: the Eddie Izzard Story , made by his ex-lover and long-term collaborator Sarah Townsend, and then in an autobiography, Believe Me: A Memoir of Love, Death, and Jazz Chickens . The first two elements of that latter subtitle largely guided Izzard back to his mother, who died of cancer when he was six years old. Constituting the film, Townsend came to suggest that all Izzard’s inspired digressive attires clique around this true, and in his journal, in opening chapters very harrowing to read easily, he expands on that thought.

” Toward the end of the cinema, I started talking about my mother …” he remembers.” And I said something revelatory:’ I know why I’m doing all this ,’ I said.’ Everything I do in life is trying to get her back. I think if I do enough events … that maybe she’ll come back .'” When he said those statements, he says, it felt like his unconscious speaking. The thought stood with him that” I do feel I started performing and doing different kinds of big, crazy, ambitious acts because on some degree, on some childlike magical-thinking height, I contemplated doing those things might raise her back .”

I wonder, having got those happens out into the public, nearly half a century on, if it has changed how he thinks about himself?

” I certainly appear I am in a better place ,” he says- but also it has given him a sense of his own strangeness.” There is that circumstance where people say wow about the marathons or whatever. And I kind of say wow very, because there are some things I did that, looking back, I don’t know how I did them. Running a double marathon on the last day in South Africa. It was 11 hours of not recreation. And about five minutes of euphoria. I’m not sure how I did that .”

One of the things about marathons- even if you are running, as he was some of the time in the UK, followed by an ice-cream van reverberating the Chariots of Fire theme- is that there is an horrid spate of day for reputing. Does his attention ever pause for breather?

” I have a lucky situation ,” he says,” which is that I am interested in any question- how did we get here? all the religions. I can think about anything. For instance when I did the 43[ marathons] I moved past a signed saying’ the Battle of Naseby: 1 mile’ and I’m immediately off thinking about Cromwell and Fairfax, Prince Rupert perhaps, and how this road I was loping on would have been a track back then and maybe the cavalry came down it, how did they get cannon round that stoop, all that, at every moment …”

Campaigning for Labour during the general election in 2015. Photo: Dominic Lipinski/ PA

Talking to Izzard, and watching him perform, you feel he has a kind of need of not ever wanting to miss any scrap of ordeal. It’s partly, he shows, why he has increased his range of doing standup in different languages in recent years.

” German has been the more difficult in so far ,” he says. He is doing Arabic next, scheduling a show in the Yemen( he was born in Aden, where his father worked for a meter for BP) to draw attention to the harsh civil campaign there, and after that, Mandarin Chinese. As he shows this, blithely, I’m reminded both of the moves in his notebook where he writes about the strategies he developed to overcome severe dyslexia as small children, and his uneasy relation with his late stepmother, Kate. The antithesis of performing as a younger soul for the recollection of his mother was a refusal to be limited by Kate’s efforts to control him. She required him to be an controller because he was good with quantities, if not with learning. He recollects her once telling him:” You’ve got to understand that you are a cog in the machine. As soon as you understand that, they are able to fit in and get on with life .” You can only imagine how that went down. Does he ever think he will become more accepting of restrictions?

” I have a very strong sense that the government only on this planet for a short duration of period ,” he says.” And that is only originating. Religious parties might think it goes on after death. My sentiment is that if that is the case it would be nice if just one person came back and tell us know it was all fine, all proven. Of all the thousands of millions of people who have died, if just one of them could come through the gloom and say, you are familiar with,’ It’s me Jeanine, it’s brilliant, there’s a really good spa ‘, that would be great .” He delays.” Although what if heaven was simply like three-star, OK-ish. You know,’ Some of the taps don’t work …'”

He puts his success down not to any particular knack, but to his being” brilliantly accepting. Some parties are perhaps brilliantly fascinating. But I have the opposite talent .” That, and stamina, and that inexhaustible interest about the world.

For a BBC series about pedigree he went to Africa to marks percentages per of his genetic make-up that was Neanderthal. It reinforced his sense that there was nothing brand-new under the sun, that people had always been the same.” We never think of cavemen being spiteful of the neighbours with the better cave, but no doubt they were ,” he says.

In hamlets in Namibia, girls were fascinated by his nail varnish; some of “the mens”, very.” You know if you have a football and some tack polish and a smile you can walk into any village in the world and find pals ,” he says.” “Theres” 7 billion of us on countries around the world now and we should be relation up more. Ninety-nine per cent of us would be live-and-let-live and’ Hi and how are you ?’. But the 1% aren’t happy with that, they want to actively budged it up and tell us that is not the way to go on .”

Convening the Bakola Pygmy in Cameroon for a BBC series to marks his genetic make-up. Photo: BBC

Talk of politics is a reminder of Izzard’s involvements in last year’s referendum expedition, in which he tried to use its own experience of doing humor in French and German and Spanish as an example of how Europe might be a place where you could share culture, rather than be defensive about it. In those fevered weeks, his arguments were sometimes made to look naive; the Mail and the rest cooked him after an awkward encounter with Nigel Farage on Question Time .

He admits that he is sometimes still learning in politics, but is unrepentant about his efforts to try to advance a cause that he has been engaged in as a performer for a long while.

” Running and disguising from Europe cannot be the way forward for us ,” he says.” The sentiment that Britain can go back to 1970 and it will still be all the same just can’t be an option .”

Does he think there is still hope for Remainers?

” It seems to me parties are always capable of being either brave and curious or fearful and suspicious. If you track humanity all the way through, the periods of success for civilisation are those periods where we have been brave and strange .”

There is plenty of anxiety and feeling in the world though. How does he think it “il be going”?

” I don’t know. If you look at the 1930 s there are obviously clear examples of how individuals can twisting this type of dreads and twist them, and then you get what historians frequently announce mass-murdering fuckheads in superpower .”

He has long has spoken of looking to run as a Labour MP in the elections. Is that still the speciman?

” Yes, the program was always to run in 2020, though Theresa May has changed that with her failed superpower seizure. So now it’s the first general election after 2020.”

He will likewise apply himself forward for Labour’s national executive committee at the party discussion this year. He didn’t make it last-place hour, though he got 70,000 votes. And if and when he has become a MP, he will give up playing and acting?

” I would. It’s like Glenda Jackson; she gave up acting for 25 years to concentrate on it, then she grows up back as King Lear .”

With Ali Fazal, Judi Dench and administrator Stephen Frears for a screening of Victoria& Abdul at the Venice film festival. Photograph: Pascal Le Segretain/ Getty Images

I wonder if another desire, to eventually have children, still applies?

” I always said kids in my 50 s. But I too always felt that I had to do stuffs firstly. Get this substance done. But yes, I haven’t given up on that .”

For someone who was treated an early reading about the fragility of life, his long-term contriving musics strange. Does he feel that inconsistency?

” I think we should all choose a year we would like to live to, and do everything we can to manufacture that the project works. I signify it could all go wrong at any point, obviously. But we also know that if we don’t get ill or get hit by a bus we are able ourselves by sucking enough liquid and continuing as fit as you were when you were a kid. As we get older and we get a bit creaky we take that as a signed to stop doing trash. My sense is we should push through creaky. I was appearing a bit sluggish lately, about a month ago, I believed right, I’ll do seven marathons in seven days. And off I proceed. The first four were a bit rubbish, but you push on through that .”

He must have good seams?

” I mutilated my knee up a while ago, trying to startle over a barricade ,” he says.” But it healed up, and now it grumbles only when I don’t use it enough .”

Is there some genetic cause for his intensity?

” Dad desired football, played until his late 30 s. I don’t know about Mum. She liked singing and comedy and Flanders and Swann but I’m not sure about play .”

I sounds his expres escape just slightly. Izzard still can’t really talk about his mother easily, at the least not in an interview. In his volume he describes how in the immediate consequence of her fatality he and his daddy and two brothers screamed together for half an hour and then stopped in case they went on for ever. In situate of rehabilitation dad bought his sons a simulation railway set and they improve it in the spare area and immersed themselves in it. The create recently resurfaced when Izzard had it reinstated and donated it to a museum in their home town of Bexhill-on-Sea, another part of his excavation of that time.

” Dad spurred us with it after Mum died ,” he says, by way of rationale.” He made a counter for the americans and we expended hours and hours building it. Then in 1975 my stepmother, Kate, came along and it was put away into chests and never came out again. It proceeded from Dad’s attic to my brother’s attic, and he didn’t know what to do with it. I imagined, why not give it to the museum in Bexhill? I guessed there might be plenty of representation railway lovers in Bexhill, and they rebuilt this thing, it’s kind of a collector’s item. They are now going to build another one, a Christmas version. We had a grand opening and Dad came down to see it .”

He likes the facts of the case that he is in a position to stir these kinds of things happen. Is he happier now than ever?

” I ever wanted the various kinds of profile that they are able to leveraging to do the things you crave ,” he says.” There is no path into it. You have to work out how you get there- over the wall, or tunnel your method in. I ever considered doing the same thing was actually going backwards. And if you start saying’ Hi, I like chicken’ on some advert, you know you have probably contacted that degree .”

You hesitate a little to ask him what he is working on next, but I do anyway.

” I’ve written my first film ,” he says.” It is called Six Minutes to Midnight , set in the summer of 1939. I’m developing a show in French in Paris. This December I am going to be on a boat, just below Notre Dame, doing two indicates nightly. What else? I’m not a good reader but I always wanted to read all of Dickens, so I have found someone who will let me read them as audiobooks- I have done a third of Great Expectations and it took four periods. So: 12 eras. And then there is the premiere of Victoria& Abdul for which Dad is coming up from Bexhill to spend his 89 th birthday with Judi Dench …”

Out of all the things he has done, I question, of what is he proudest?

” Mostly I hope I have done things that help other people to do them ,” he says.” That was the thing with coming out as transgender, and “its been” the same thing doing the marathons, or memorizing its own language. I hope parties might conceive, well if that moronic can do it, why can’t I? I symbolize, I’m just some guy, right. Nothing special ?”

I’m not quite convinced.

Victoria& Abdul is released on Friday 15 September. Guess Me issued by Michael Joseph( PS20 ). To ordering a replica for PS17 go to guardianbookshop.com or announce 0330 333 6846. Free UK p& p over PS10, online tells only. Telephone tells min p& p of PS1. 99

Read more: www.theguardian.com

The post Eddie Izzard:’ Everything I do in life is trying to get my mother back’ appeared first on vitalmindandbody.com.

from WordPress http://ift.tt/2ywee5U

via IFTTT

0 notes

Text

Learning together: Catching up on the adventures of connected learners and teachers via ED677

Over three years now, during the spring, I have taught ED677 at Arcadia University’s School of Education, a “connected course” focused on seeking equity in connected learning and teaching. Final projects for ED677, or what we call our final “makes,” are something we design that emerges from our inquiry and supports our work beyond the 15 weeks of the course. The goal is that each project explicitly focus on building towards equity and connected learning, building off the framework of Connected Learning, and contributes to making interest-driven, production centered and connected opportunities for all a reality in the world (in big and small ways).

These projects have been great and there is much to learn from what folks end up designing to support connected learning in their context. And I was curious to learn what happened since! Therefore this past semester, I invited several folks who participated in the past to come and share with my current class about their work and reflections on Connected Learning and teaching. I also had a chance recently to hear from several of past ED677ers in a panel discussion at Arcadia University in relation to a meeting on Connected Learning in Teacher Education. Below then is a set of compiled thoughts, notes and quotes from this work and those discussions.

Robert Sidelinker, a teacher at Warwick Elementary, participated in ED677 in 2016 and now teaches his students in a 1-6 STEM class called QUEST (Questioning and Understanding through Engineering, Science, and Technology). Throughout his time in ED677 he blogged about an inquiry project he was working on throughout the semester, a making and game design/play unit he co-designed with his students and colleagues. What I like the best about his posts are the ways power shifts to the students as he describes the unfolding of this project:

It’s funny. Weeks ago, as my team and I created the inquiry questions that would help lead us into this unit of study, the questions seemed to be directed at us, the teachers. Now that our students have begun their work, it seems that the questions apply to them, not the “educators.” …

… Throughout the experience, students have been blogging about the game and blogging about ways to persuade teachers to allow their students to play.

In a reflection on this work he writes “As a teacher, I don’t think I’ve ever attempted a learning activity that is so social. Students are now making original creations that were born from commonly shared ideas!”

Now a couple years later, and while participating in this recent panel discussion, Robert continues to think about this work and how best to support his colleagues from his position as a QUEST teacher and educational technology coach at his school. In a reflection on his own journey in becoming a more connected teacher, he says that moving from a deliverer of content to a facilitator/manager has had one of the biggest impacts on him. And so in his role as a coach, he works to support his colleagues from where they are in this process. He reflects that “a lot of teachers are really uncomfortable with not knowing the answer … but in today’s society the answer [to not knowing] should be “let’s look it up” .. you’re not forfeiting their authority; you are preparing [students] for the future.”

Shayla Amenra has served as an educator and artist in schools and afterschool programs and now operates HAPPISPACE; an education services company specializing in out-of-school time (OST), mobile makerspaces, and curriculum development. During her participation in ED677 Shayla was also participating in an inquiry group with TAG (Teacher Action Group) Philly. Her work with other iTag educators focused on developing an African-American history curriculum. Since the focus on ED677 is to connect our work in class with work we are doing in the world, she submitted the website that she made as part of her final make that semester.

As an educator and an artist, Shayla actively integrates her making work (she is a jeweler; see HAPPIMADE) into the way she thinks about learning and education, always working to connect her networks, her interests, and available resources. During the recent panel discussion, she talked about how this supports her connecting her students to those things that they are interested in -- a focus that she puts front and center to all of her teaching.

... when you are student focused, student centered, and you are connecting them to what they are interested in, they show up! They are interested, they are engaged … they ask those questions [that] even you [as an educator] are taken back -- Wow, I didn’t even think of that! ... For me it’s always amazing. There hasn’t been a project that I haven't done where allowing students to talk and explain where their interest is within their project where I’m not surprised by the end … I map out every single thing, I’m a super planner; I’ll have every scenario for every scenario, and then the student will still find that one thing that I hadn’t even thought of. And it’s amazing. It’s always about the students for me.

Helga Porter was also a participant in this same panel discussion. She is a math teacher and since her participation in ED677 in spring 2015, has become the S.T.E.M. liaison for her building, “encouraging teaching and learning with a social conscience for all” she writes. As an advocate for increasing S.T.E.M. in the classroom, she is an active member of the district’s Strategic Planning Committee with a specific focus on their transformative curriculum pathways work.

During the panel discussion, Helga talked about the ways that the schools she works with are using the framework of Connected Learning to describe and talk about the work they are doing. She describes the framework as helpful language that helps modernize what they were already striving for in the district. She also shared how projects they have started, such as a mobile makerspace cart for each school building, are becoming sustainable as they use them. After upfront costs, she explains, … students bring things in to add to it. “They’re realizing they don’t need money - they can do something with the materials they already have.”

Helga reflected on her experience in the program at Arcadia and described how its loose parameters really challenged her:

I tried to figure out what [the instructors] wanted. Then we realized [the looseness] was all by design - they’re evil people. We were supposed to learn this is what our students and colleagues are experiencing. We need to take risks, too. We’re not just facilitators. That was the aha moment for me. Learning about ourselves, learning to take risks, fall, fall forward, and recover.

“They were evil in how they did it, but we forgive you.” she added, looking with a smile at me and Meenoo Rami, the two instructors of the main connected learning courses at Arcadia. Several others concurred!

Kathy Walsh was another participant in this panel and also came to visit my class during the spring of 2017. She took ED677 with Helga that first “evil” spring semester, and during that time she set up this blog space and related maker-activities. Although she didn’t continue the blog itself past that one semester, she does continue to support her students in blogging and connecting to others in ways that allow them to create their own pathways forward. For example, this past semester she describes working working on a unit of study about chemical reactions where students blogged about their interests and research while Kathy worked to connect them to experts in the field.

Kathy is currently a teacher at Building 21 in Philadelphia and the founder of Youth Engineering and Science where she organizes summer youth STEM programming for youth. During a visit to ED677 this past semester she declared “Connected Learning, to me, is all about social justice.”

I work in a public high school in North Philadelphia and we do project-based learning and so one of the most important things is trying to find a way to make the work relevant for students and the best way to do it is to connect them to what really is going on in their community, in their future employment and future college and career pathways. So this is what I try to do in all my projects. ... Becoming a connected learning [myself] has been essential because I can do it now. I have the tools.

While Lana Iskandarani, an Arabic language instructor at a local university, was in ED677 during the spring 2016 she shared what she described as a small move in her classroom that had big consequences on a class she was teaching at the time:

When I assigned projects to my students last semester and the years prior, they were individual pieces of work. I gave them some freedom to choose what they want to learn about, but not completely. There were some rules and constraints to follow in completing their work. Every student worked privately on their project and they had their own presentation in the classroom. The only audience for those pieces of work were my students and I. The students reflections were done orally after every presentation.

This semester, by implementing the connected learning principles and making small changes every week, I prepared my students to be more flexible with collaboration inside and outside the classroom. It became evident they were responsible and curious about the subjects at hands, more able to do their research, and more open to share their work with peers and other interested people out of the classroom. The final projects were examples of their improvement, and the results came out phenomenal.

This idea of small changes, or “small moves” as we also referred to them and as per our core text Teaching in the Connected Learning Classroom, was very influential on Lana. And ultimately Lana’s experience and description of the ways she thought about these moves, was very influential on me. Lana has since described her work making Connected Learning framework a key piece of her curriculum project as she finishes her graduate work as well as a core part of her classroom and still references the ways that small changes can make a significant impact in her classroom, even with a fairly structured language learning context.

Tracey Dean is a high school Art teacher in the Radnor Township School District and also created a website as part of her final make in ED667 during this past spring 2017. This site focuses on the work created by students she works with and underscores Tracey’s frequent moniker “Art Matters.” In the recent panel discussion, she continued to emphasis this direction:

Connected Learning needs to involve everyone. Our students did art in the halls so everyone could see. It initiated conversations. Bringing art out of the classroom. Art students shared their digital portfolios with teachers of other subjects, because sometimes teachers only know what their students are like in their single class.

I am really excited to see Tracey’s work unfold in the coming year. During this same panel discussion, she described a discovery over the last semester that has made her rethink how she wants to organize her classroom in the coming fall. Whereas previously she felt she was giving her students choice in their work, a value she expressed as critical to connected learning, the students shared that they didn’t feel that they had real choice in her class. After puzzling the disconnect for a bit in ED677, she then talked about the way she is moving towards setting up makerspace and stations in her classroom instead of doing whole class instruction followed by choice, which is how she had things previously organized.

The questions and tensions exist in this however, and Tracey talked about the ways that it can be really scary:

I guess my biggest fear with this whole thing and where it could go wrong, I am expected to present this work at District Art Month in in March. .. What’s the work going to look like? .. That’s where it’s terrifying to me about it. Also those conversations at home: ‘What are you learning? Oh, whatever we want -- Ms. Dean is letting us chose this year.’ I don’t want them saying that at the dinner table! So those are the two things I’m going to have to figure out.

After a third semester of ED677, and the chance to have follow-up discussions with the educators above, my attention now turns to the ways that they can continue to take leadership in the Arcadia Connected Learning program as well as ways we can continue to network ourselves together to support this challenging but ultimately critical work. We are in this together.

Thank you to Robert, Shayla, Helga, Kathy, Lana and Tracey for sharing their work and learning. Wishing you all the best in your endeavors forward … and looking forward to learning more with you along the way.

0 notes