#Texas Spring Migration

Text

Ruby Throat Humming Bird - female. A first for me, hummingbird in the bird bath.

#birds#photographers on tumblr#texas#nature#wildlife#original photographers#texas spring migration#hummingbird

379 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thought I’d share these for anyone who hasn’t seen them :) They’re the official descriptions for each of the Anemoi albums on The Oh Hellos’ website!

Notos

Notos, the first installment in an ongoing series, is named for the ancient Greco-Roman god of the south wind, who brought storms in the summer. Musically, the record draws from the siblings' memories of summers spent exploring the Pacific Northwest with their grandparents, as well as their experiences with the frequent threat of hurricanes as they grew up on the Texas Gulf Coast. Thematically, the series considers the question: "where did our ideas come from?" Notos recounts a time when the duo weren't even aware there was a question to ask, and reflects on the backfire effect we experience when confronted with new information for the first time.

Eurus

Once that first question posed in the Notos EP is asked — "where did my ideas come from?" — it opens the floodgates to more. While wrestling with them all can ultimately lead to a fuller understanding of the world around you (and leave you with more empathy than you started with), it can also leave you feeling alienated from the communities you used to identify with. Eurus, released in early 2018 as the second installment in a series, is a continued interrogation of our own beliefs, and as Eurus was the wind most closely associated with autumn, the record seeks to capture the feelings of dark woods, dry branches, dead leaves, and wondering who had migrated — you, or your flock?

Boreas

Boreas, the northern wind, ushered in the harsh frosts of lonely winter. The arrangements of this third installment evoke images of snow-blanketed darkness, candlelight behind cupped hands, and a vast night sky ribboned with stars and auroras. As we wrote these songs, we found ourselves confronted with the ways we’ve personally and communally reflected the character of this wind — how we often avoid discomfort, even at the expense of others, until we are left cold, hard, and unfeeling. In this record, we ask the winter to instead kindle us into something warmer and softer than who we’ve been.

Zephyrus

The series concludes. Zephyrus, the final cardinal wind of this project, brought the gentle warmth of spring that summoned up a new year of growth rooted in the fertile ashes of all the structures that keep us isolated and unfeeling — the kind of growth we can see in ourselves, if we can muster the courage to be vulnerable. The arrangements mirror and embrace this shift, rising up like tender leaves breaking through concrete and cascading down like mountain rivers surging with the first thaw of the season. It’s been a long year; thanks for listening.

#i just discovered this website actually it has a lot of nice stuff about their albums! look it up if you’re curious#oh hellos#the oh hellos#music stuff#folk music#anemoi#anemoi albums#the four winds#four winds#the four winds albums#four winds albums#dear wormwood#through the deep dark valley#ttddv#Notos#Eurus#Boreas#Zephyrus#albums#fav albums

83 notes

·

View notes

Text

I Love Dick And Balls

The American woodcock (Scolopax minor), sometimes colloquially referred to as the timberdoodle,[2] is a small shorebird species found primarily in the eastern half of North America. Woodcocks spend most of their time on the ground in brushy, young-forest habitats, where the birds' brown, black, and gray plumage provides excellent camouflage.

The American woodcock is the only species of woodcock inhabiting North America.[3] Although classified with the sandpipers and shorebirds in the family Scolopacidae, the American woodcock lives mainly in upland settings. Its many folk names include timberdoodle, bogsucker, night partridge, brush snipe, hokumpoke, and becasse.[4]

The population of the American woodcock has fallen by an average of slightly more than 1% annually since the 1960s. Most authorities attribute this decline to a loss of habitat caused by forest maturation and urban development. Because of the male woodcock's unique, beautiful courtship flights, the bird is welcomed as a harbinger of spring in northern areas. It is also a popular game bird, with about 540,000 killed annually by some 133,000 hunters in the U.S.[5]

In 2008, wildlife biologists and conservationists released an American woodcock conservation plan presenting figures for the acreage of early successional habitat that must be created and maintained in the U.S. and Canada to stabilize the woodcock population at current levels, and to return it to 1970s densities.[6]

Description

The American woodcock has a plump body, short legs, a large, rounded head, and a long, straight prehensile bill. Adults are 10 to 12 inches (25 to 30 cm) long and weigh 5 to 8 ounces (140 to 230 g).[7] Females are considerably larger than males.[8] The bill is 2.5 to 2.8 inches (6.4 to 7.1 cm) long.[4] Wingspans range from 16.5 to 18.9 inches (42 to 48 cm).[9]

Illustration of American woodcock head and wing feathers

Woodcock, with attenuate primaries, natural size, 1891

The plumage is a cryptic mix of different shades of browns, grays, and black. The chest and sides vary from yellowish-white to rich tans.[8] The nape of the head is black, with three or four crossbars of deep buff or rufous.[4] The feet and toes, which are small and weak, are brownish gray to reddish brown.[8] Woodcocks have large eyes located high in their heads, and their visual field is probably the largest of any bird, 360° in the horizontal plane and 180° in the vertical plane.[10]

The woodcock uses its long, prehensile bill to probe in the soil for food, mainly invertebrates and especially earthworms. A unique bone-and-muscle arrangement lets the bird open and close the tip of its upper bill, or mandible, while it is sunk in the ground. Both the underside of the upper mandible and the long tongue are rough-surfaced for grasping slippery prey.[4]

Taxonomy

The genus Scolopax was introduced in 1758 by the Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus in the tenth edition of his Systema Naturae.[11] The genus name is Latin for a snipe or woodcock.[12] The type species is the Eurasian woodcock (Scolopax rusticola).[13]

Distribution and habitat

Woodcocks inhabit forested and mixed forest-agricultural-urban areas east of the 98th meridian. Woodcock have been sighted as far north as York Factory, Manitoba, and east to Labrador and Newfoundland. In winter, they migrate as far south as the Gulf Coast of the United States and Mexico.[8]

The primary breeding range extends from Atlantic Canada (Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, and New Brunswick) west to southeastern Manitoba, and south to northern Virginia, western North Carolina, Kentucky, northern Tennessee, northern Illinois, Missouri, and eastern Kansas. A limited number breed as far south as Florida and Texas. The species may be expanding its distribution northward and westward.[8]

After migrating south in autumn, most woodcocks spend the winter in the Gulf Coast and southeastern Atlantic Coast states. Some may remain as far north as southern Maryland, eastern Virginia, and southern New Jersey. The core of the wintering range centers on Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia.[8] Based on the Christmas Bird Count results, winter concentrations are highest in the northern half of Alabama.

American woodcocks live in wet thickets, moist woods, and brushy swamps.[3] Ideal habitats feature early successional habitat and abandoned farmland mixed with forest. In late summer, some woodcocks roost on the ground at night in large openings among sparse, patchy vegetation.[8]Courtship/breeding habitats include forest openings, roadsides, pastures, and old fields from which males call and launch courtship flights in springtime. Nesting habitats include thickets, shrubland, and young to middle-aged forest interspersed with openings. Feeding habitats have moist soil and feature densely growing young trees such as aspen (Populus spp.), birch (Betula spp.), and mixed hardwoods less than 20 years of age, and shrubs, particularly alder (Alnus spp.). Roosting habitats are semiopen sites with short, sparse plant cover, such as blueberry barrens, pastures, and recently heavily logged forest stands.[8]

Migration

Woodcocks migrate at night. They fly at low altitudes, individually or in small, loose flocks. Flight speeds of migrating birds have been clocked at 16 to 28 mi/h (26 to 45 km/h). However, the slowest flight speed ever recorded for a bird, 5 mi/h (8 km/h), was recorded for this species.[14] Woodcocks are thought to orient visually using major physiographic features such as coastlines and broad river valleys.[8] Both the autumn and spring migrations are leisurely compared with the swift, direct migrations of many passerine birds.

In the north, woodcocks begin to shift southward before ice and snow seal off their ground-based food supply. Cold fronts may prompt heavy southerly flights in autumn. Most woodcocks start to migrate in October, with the major push from mid-October to early November.[15] Most individuals arrive on the wintering range by mid-December. The birds head north again in February. Most have returned to the northern breeding range by mid-March to mid-April.[8]

Migrating birds' arrival at and departure from the breeding range is highly irregular. In Ohio, for example, the earliest birds are seen in February, but the bulk of the population does not arrive until March and April. Birds start to leave for winter by September, but some remain until mid-November.[16]

Behavior and ecology

Food and feeding

American woodcock catching a worm in a New York City park

Woodcocks eat mainly invertebrates, particularly earthworms (Oligochaeta). They do most of their feeding in places where the soil is moist. They forage by probing in soft soil in thickets, where they usually remain well-hidden. Other items in their diet include insect larvae, snails, centipedes, millipedes, spiders, snipe flies, beetles, and ants. A small amount of plant food is eaten, mainly seeds.[8] Woodcocks are crepuscular, being most active at dawn and dusk.

Breeding

In spring, males occupy individual singing grounds, openings near brushy cover from which they call and perform display flights at dawn and dusk, and if the light levels are high enough, on moonlit nights. The male's ground call is a short, buzzy peent. After sounding a series of ground calls, the male takes off and flies from 50 to 100 yd (46 to 91 m) into the air. He descends, zigzagging and banking while singing a liquid, chirping song.[8] This high spiralling flight produces a melodious twittering sound as air rushes through the male's outer primary wing feathers.[17]

Males may continue with their courtship flights for as many as four months running, sometimes continuing even after females have already hatched their broods and left the nest. Females, known as hens, are attracted to the males' displays. A hen will fly in and land on the ground near a singing male. The male courts the female by walking stiff-legged and with his wings stretched vertically, and by bobbing and bowing. A male may mate with several females. The male woodcock plays no role in selecting a nest site, incubating eggs, or rearing young. In the primary northern breeding range, the woodcock may be the earliest ground-nesting species to breed.[8]

Woodcock chick in nest

Downy young are already well-camouflaged.

The hen makes a shallow, rudimentary nest on the ground in the leaf and twig litter, in brushy or young-forest cover usually within 150 yd (140 m) of a singing ground.[4] Most hens lay four eggs, sometimes one to three. Incubation takes 20 to 22 days.[3] The down-covered young are precocial and leave the nest within a few hours of hatching.[8] The female broods her young and feeds them. When threatened, the fledglings usually take cover and remain motionless, attempting to escape detection by relying on their cryptic coloration. Some observers suggest that frightened young may cling to the body of their mother, that will then take wing and carry the young to safety.[18] Woodcock fledglings begin probing for worms on their own a few days after hatching. They develop quickly and can make short flights after two weeks, can fly fairly well at three weeks, and are independent after about five weeks.[3]

The maximum lifespan of adult American woodcock in the wild is 8 years.[19]

Rocking behavior

American woodcocks sometimes rock back and forth as they walk, perhaps to aid their search for worms.

American woodcocks occasionally perform a rocking behavior where they will walk slowly while rhythmically rocking their bodies back and forth. This behavior occurs during foraging, leading ornithologists such as Arthur Cleveland Bent and B. H. Christy to theorize that this is a method of coaxing invertebrates such as earthworms closer to the surface.[20] The foraging theory is the most common explanation of the behavior, and it is often cited in field guides.[21]

An alternative theory for the rocking behavior has been proposed by some biologists, such as Bernd Heinrich. It is thought that this behavior is a display to indicate to potential predators that the bird is aware of them.[22] Heinrich notes that some field observations have shown that woodcocks will occasionally flash their tail feathers while rocking, drawing attention to themselves. This theory is supported by research done by John Alcock who believes this is a type of aposematism.[23]

Population status

How many woodcock were present in eastern North America before European settlement is unknown. Colonial agriculture, with its patchwork of family farms and open-range livestock grazing, probably supported healthy woodcock populations.[4]

The woodcock population remained high during the early and mid-20th century, after many family farms were abandoned as people moved to urban areas, and crop fields and pastures grew up in brush. In recent decades, those formerly brushy acres have become middle-aged and older forest, where woodcock rarely venture, or they have been covered with buildings and other human developments. Because its population has been declining, the American woodcock is considered a "species of greatest conservation need" in many states, triggering research and habitat-creation efforts in an attempt to boost woodcock populations.

Population trends have been measured through springtime breeding bird surveys, and in the northern breeding range, springtime singing-ground surveys.[8] Data suggest that the woodcock population has fallen rangewide by an average of 1.1% yearly over the last four decades.[6]

Conservation

The American woodcock is not considered globally threatened by the IUCN. It is more tolerant of deforestation than other woodcocks and snipes; as long as some sheltered woodland remains for breeding, it can thrive even in regions that are mainly used for agriculture.[1][24] The estimated population is 5 million, so it is the most common sandpiper in North America.[17]

The American Woodcock Conservation Plan presents regional action plans linked to bird conservation regions, fundamental biological units recognized by the U.S. North American Bird Conservation Initiative. The Wildlife Management Institute oversees regional habitat initiatives intended to boost the American woodcock's population by protecting, renewing, and creating habitat throughout the species' range.[6]

Creating young-forest habitat for American woodcocks helps more than 50 other species of wildlife that need early successional habitat during part or all of their lifecycles. These include relatively common animals such as white-tailed deer, snowshoe hare, moose, bobcat, wild turkey, and ruffed grouse, and animals whose populations have also declined in recent decades, such as the golden-winged warbler, whip-poor-will, willow flycatcher, indigo bunting, and New England cottontail.[25]

Leslie Glasgow,[26] the assistant secretary of the Interior for Fish, Wildlife, Parks, and Marine Resources from 1969 to 1970, wrote a dissertation through Texas A&M University on the woodcock, with research based on his observations through the Louisiana State University (LSU) Agricultural Experiment Station. He was an LSU professor from 1948 to 1980 and an authority on wildlife in the wetlands.[27]

References

BirdLife International (2020). "Scolopax minor". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T22693072A182648054. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-3.RLTS.T22693072A182648054.en. Retrieved November 13, 2021.

The American Woodcock Today | Woodcock population and young forest habitat management. Timberdoodle.org. Retrieved on 2013-04-03.

Kaufman, Kenn (1996). Lives of North American Birds. Houghton Mifflin, pp. 225–226, ISBN 0618159886.

Sheldon, William G. (1971). Book of the American Woodcock. University of Massachusetts.

Cooper, T. R. & K. Parker (2009). American woodcock population status, 2009. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Laurel, Maryland.

Kelley, James; Williamson, Scot & Cooper, Thomas, eds. (2008). American Woodcock Conservation Plan: A Summary of and Recommendations for Woodcock Conservation in North America.

Smith, Christopher (2000). Field Guide to Upland Birds and Waterfowl. Wilderness Adventures Press, pp. 28–29, ISBN 1885106203.

Keppie, D. M. & R. M. Whiting Jr. (1994). American Woodcock (Scolopax minor), The Birds of North America.

"American Woodcock Identification, All About Birds, Cornell Lab of Ornithology". www.allaboutbirds.org. Retrieved September 27, 2020.

Jones, Michael P.; Pierce, Kenneth E.; Ward, Daniel (2007). "Avian vision: a review of form and function with special consideration to birds of prey". Journal of Exotic Pet Medicine. 16 (2): 69. doi:10.1053/j.jepm.2007.03.012.

Linnaeus, Carl (1758). Systema Naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (in Latin). Vol. 1 (10th ed.). Holmiae (Stockholm): Laurentii Salvii. p. 145.

Jobling, James A (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. p. 351. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

Peters, James Lee, ed. (1934). Check-List of Birds of the World. Vol. 2. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 278.

Amazing Bird Records. Trails.com (2010-07-27). Retrieved on 2013-04-03.

Sepik, G. F. and E. L. Derleth (1993). Habitat use, home range size, and patterns of moves of the American Woodcock in Maine. in Proc. Eighth Woodcock Symp. (Longcore, J. R. and G. F. Sepik, eds.) Biol. Rep. 16, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Washington, D.C.

Ohio Ornithological Society (2004). Annotated Ohio state checklist Archived 2004-07-18 at the Wayback Machine.

O'Brien, Michael; Crossley, Richard & Karlson, Kevin (2006). The Shorebird Guide. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, pp. 444–445, ISBN 0618432949.

Mann, Clive F. (1991). "Sunda Frogmouth Batrachostomus cornutus carrying its young" (PDF). Forktail. 6: 77–78. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 28, 2008.

Wasser, D. E.; Sherman, P. W. (2010). "Avian longevities and their interpretation under evolutionary theories of senescence". Journal of Zoology. 280 (2): 103. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2009.00671.x.

Bent, A. C. (1927). "Life histories of familiar North American birds: American Woodcock, Scalopax minor". United States National Museum Bulletin. Smithsonian Institution. 142 (1): 61–78.

"American Woodcock". Audubon. National Audubon Society. Retrieved October 5, 2023.

Heinrich, Bernd (March 1, 2016). "Note on the Woodcock Rocking Display". Northeastern Naturalist. 23 (1): N4–N7.

Alcock, John (2013). Animal behavior: an evolutionary approach (10th ed.). Sunderland (Mass.): Sinauer. p. 522. ISBN 0878939660.

Henninger, W. F. (1906). "A preliminary list of the birds of Seneca County, Ohio" (PDF). Wilson Bulletin. 18 (2): 47–60.

the Woodcock Management Plan. Timberdoodle.org. Retrieved on 2013-04-03.

[1]Paul Y. Burns (June 13, 2008). "Leslie L. Glasgow". lsuagcdenter.com. Retrieved October 21, 2014.

Further readingChoiniere, Joe (2006). Seasons of the Woodcock: The secret life of a woodland shorebird. Sanctuary 45(4): 3–5. Sepik, Greg F.; Owen, Roy & Coulter, Malcolm (1981). A Landowner's Guide to Woodcock Management in the Northeast, Misc. Report 253, Maine Agricultural Experiment Station, University of Maine.

External linksAmerican woodcock species account – Cornell Lab of Ornithology American Woodcock – Scolopax minor – USGS Patuxent Bird Identification Infocenter American Woodcock Bird Sound Rite of Spring – Illustrated account of the phenomenal courtship flight of the male American woodcock American Woodcock videos[permanent dead link] on the Internet Bird Collection Photo-High Res; Article – www.fws.gov–"Moosehorn National Wildlife Refuge", photo gallery and analysis American Woodcock Conservation Plan A Summary of and Recommendations for Woodcock Conservation in North America Timberdoodle.org: the Woodcock Management Plan Sepik, Greg F.; Ray B. Owen Jr.; Malcolm W. Coulter (July 1981). "Landowner's Guide to Woodcock Management in the Northeast". Maine Agricultural Experiment Station Miscellaneous Report 253. vte

Sandpipers (family: Scolopacidae)

Taxon identifiers Wikidata: Q694319 Wikispecies: Scolopax minor ABA: amewoo ADW: Scolopax_minor ARKive: scolopax-minor Avibase: F4829920F1710E56 BirdLife: 22693072 BOLD: 10164 CoL: 6XXHP BOW: amewoo eBird: amewoo EoL: 45509171 Euring: 5310 FEIS: scmi Fossilworks: 129789 GBIF: 2481695 GNAB: american-woodcock iNaturalist: 3936 IRMNG: 10836458 ITIS: 176580 IUCN: 22693072 NatureServe: 2.105226 NCBI: 56299 ODNR: american-woodcock WoRMS: 159027 Xeno-canto: Scolopax-minor

Categories:IUCN Red List least concern speciesScolopaxNative birds of the Eastern United StatesNative birds of Eastern CanadaBirds of MexicoBirds described in 1789Taxa named by Johann Friedrich Gmelin

The American woodcock (Scolopax minor), sometimes colloquially referred to as the timberdoodle,[2] is a small shorebird species found primarily in the eastern half of North America. Woodcocks spend most of their time on the ground in brushy, young-forest habitats, where the birds' brown, black, and gray plumage provides excellent camouflage.

The American woodcock is the only species of woodcock inhabiting North America.[3] Although classified with the sandpipers and shorebirds in the family Scolopacidae, the American woodcock lives mainly in upland settings. Its many folk names include timberdoodle, bogsucker, night partridge, brush snipe, hokumpoke, and becasse.[4]

The population of the American woodcock has fallen by an average of slightly more than 1% annually since the 1960s. Most authorities attribute this decline to a loss of habitat caused by forest maturation and urban development. Because of the male woodcock's unique, beautiful courtship flights, the bird is welcomed as a harbinger of spring in northern areas. It is also a popular game bird, with about 540,000 killed annually by some 133,000 hunters in the U.S.[5]

In 2008, wildlife biologists and conservationists released an American woodcock conservation plan presenting figures for the acreage of early successional habitat that must be created and maintained in the U.S. and Canada to stabilize the woodcock population at current levels, and to return it to 1970s densities.[6]

Description

The American woodcock has a plump body, short legs, a large, rounded head, and a long, straight prehensile bill. Adults are 10 to 12 inches (25 to 30 cm) long and weigh 5 to 8 ounces (140 to 230 g).[7] Females are considerably larger than males.[8] The bill is 2.5 to 2.8 inches (6.4 to 7.1 cm) long.[4] Wingspans range from 16.5 to 18.9 inches (42 to 48 cm).[9]

Illustration of American woodcock head and wing feathers

Woodcock, with attenuate primaries, natural size, 1891

The plumage is a cryptic mix of different shades of browns, grays, and black. The chest and sides vary from yellowish-white to rich tans.[8] The nape of the head is black, with three or four crossbars of deep buff or rufous.[4] The feet and toes, which are small and weak, are brownish gray to reddish brown.[8] Woodcocks have large eyes located high in their heads, and their visual field is probably the largest of any bird, 360° in the horizontal plane and 180° in the vertical plane.[10]

The woodcock uses its long, prehensile bill to probe in the soil for food, mainly invertebrates and especially earthworms. A unique bone-and-muscle arrangement lets the bird open and close the tip of its upper bill, or mandible, while it is sunk in the ground. Both the underside of the upper mandible and the long tongue are rough-surfaced for grasping slippery prey.[4]

Taxonomy

The genus Scolopax was introduced in 1758 by the Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus in the tenth edition of his Systema Naturae.[11] The genus name is Latin for a snipe or woodcock.[12] The type species is the Eurasian woodcock (Scolopax rusticola).[13]

Distribution and habitat

Woodcocks inhabit forested and mixed forest-agricultural-urban areas east of the 98th meridian. Woodcock have been sighted as far north as York Factory, Manitoba, and east to Labrador and Newfoundland. In winter, they migrate as far south as the Gulf Coast of the United States and Mexico.[8]

The primary breeding range extends from Atlantic Canada (Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, and New Brunswick) west to southeastern Manitoba, and south to northern Virginia, western North Carolina, Kentucky, northern Tennessee, northern Illinois, Missouri, and eastern Kansas. A limited number breed as far south as Florida and Texas. The species may be expanding its distribution northward and westward.[8]

After migrating south in autumn, most woodcocks spend the winter in the Gulf Coast and southeastern Atlantic Coast states. Some may remain as far north as southern Maryland, eastern Virginia, and southern New Jersey. The core of the wintering range centers on Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia.[8] Based on the Christmas Bird Count results, winter concentrations are highest in the northern half of Alabama.

American woodcocks live in wet thickets, moist woods, and brushy swamps.[3] Ideal habitats feature early successional habitat and abandoned farmland mixed with forest. In late summer, some woodcocks roost on the ground at night in large openings among sparse, patchy vegetation.[8]Courtship/breeding habitats include forest openings, roadsides, pastures, and old fields from which males call and launch courtship flights in springtime. Nesting habitats include thickets, shrubland, and young to middle-aged forest interspersed with openings. Feeding habitats have moist soil and feature densely growing young trees such as aspen (Populus spp.), birch (Betula spp.), and mixed hardwoods less than 20 years of age, and shrubs, particularly alder (Alnus spp.). Roosting habitats are semiopen sites with short, sparse plant cover, such as blueberry barrens, pastures, and recently heavily logged forest stands.[8]

Migration

Woodcocks migrate at night. They fly at low altitudes, individually or in small, loose flocks. Flight speeds of migrating birds have been clocked at 16 to 28 mi/h (26 to 45 km/h). However, the slowest flight speed ever recorded for a bird, 5 mi/h (8 km/h), was recorded for this species.[14] Woodcocks are thought to orient visually using major physiographic features such as coastlines and broad river valleys.[8] Both the autumn and spring migrations are leisurely compared with the swift, direct migrations of many passerine birds.

In the north, woodcocks begin to shift southward before ice and snow seal off their ground-based food supply. Cold fronts may prompt heavy southerly flights in autumn. Most woodcocks start to migrate in October, with the major push from mid-October to early November.[15] Most individuals arrive on the wintering range by mid-December. The birds head north again in February. Most have returned to the northern breeding range by mid-March to mid-April.[8]

Migrating birds' arrival at and departure from the breeding range is highly irregular. In Ohio, for example, the earliest birds are seen in February, but the bulk of the population does not arrive until March and April. Birds start to leave for winter by September, but some remain until mid-November.[16]

Behavior and ecology

Food and feeding

American woodcock catching a worm in a New York City park

Woodcocks eat mainly invertebrates, particularly earthworms (Oligochaeta). They do most of their feeding in places where the soil is moist. They forage by probing in soft soil in thickets, where they usually remain well-hidden. Other items in their diet include insect larvae, snails, centipedes, millipedes, spiders, snipe flies, beetles, and ants. A small amount of plant food is eaten, mainly seeds.[8] Woodcocks are crepuscular, being most active at dawn and dusk.

Breeding

In spring, males occupy individual singing grounds, openings near brushy cover from which they call and perform display flights at dawn and dusk, and if the light levels are high enough, on moonlit nights. The male's ground call is a short, buzzy peent. After sounding a series of ground calls, the male takes off and flies from 50 to 100 yd (46 to 91 m) into the air. He descends, zigzagging and banking while singing a liquid, chirping song.[8] This high spiralling flight produces a melodious twittering sound as air rushes through the male's outer primary wing feathers.[17]

Males may continue with their courtship flights for as many as four months running, sometimes continuing even after females have already hatched their broods and left the nest. Females, known as hens, are attracted to the males' displays. A hen will fly in and land on the ground near a singing male. The male courts the female by walking stiff-legged and with his wings stretched vertically, and by bobbing and bowing. A male may mate with several females. The male woodcock plays no role in selecting a nest site, incubating eggs, or rearing young. In the primary northern breeding range, the woodcock may be the earliest ground-nesting species to breed.[8]

Woodcock chick in nest

Downy young are already well-camouflaged.

The hen makes a shallow, rudimentary nest on the ground in the leaf and twig litter, in brushy or young-forest cover usually within 150 yd (140 m) of a singing ground.[4] Most hens lay four eggs, sometimes one to three. Incubation takes 20 to 22 days.[3] The down-covered young are precocial and leave the nest within a few hours of hatching.[8] The female broods her young and feeds them. When threatened, the fledglings usually take cover and remain motionless, attempting to escape detection by relying on their cryptic coloration. Some observers suggest that frightened young may cling to the body of their mother, that will then take wing and carry the young to safety.[18] Woodcock fledglings begin probing for worms on their own a few days after hatching. They develop quickly and can make short flights after two weeks, can fly fairly well at three weeks, and are independent after about five weeks.[3]

The maximum lifespan of adult American woodcock in the wild is 8 years.[19]

Rocking behavior

American woodcocks sometimes rock back and forth as they walk, perhaps to aid their search for worms.

American woodcocks occasionally perform a rocking behavior where they will walk slowly while rhythmically rocking their bodies back and forth. This behavior occurs during foraging, leading ornithologists such as Arthur Cleveland Bent and B. H. Christy to theorize that this is a method of coaxing invertebrates such as earthworms closer to the surface.[20] The foraging theory is the most common explanation of the behavior, and it is often cited in field guides.[21]

An alternative theory for the rocking behavior has been proposed by some biologists, such as Bernd Heinrich. It is thought that this behavior is a display to indicate to potential predators that the bird is aware of them.[22] Heinrich notes that some field observations have shown that woodcocks will occasionally flash their tail feathers while rocking, drawing attention to themselves. This theory is supported by research done by John Alcock who believes this is a type of aposematism.[23]

Population status

How many woodcock were present in eastern North America before European settlement is unknown. Colonial agriculture, with its patchwork of family farms and open-range livestock grazing, probably supported healthy woodcock populations.[4]

The woodcock population remained high during the early and mid-20th century, after many family farms were abandoned as people moved to urban areas, and crop fields and pastures grew up in brush. In recent decades, those formerly brushy acres have become middle-aged and older forest, where woodcock rarely venture, or they have been covered with buildings and other human developments. Because its population has been declining, the American woodcock is considered a "species of greatest conservation need" in many states, triggering research and habitat-creation efforts in an attempt to boost woodcock populations.

Population trends have been measured through springtime breeding bird surveys, and in the northern breeding range, springtime singing-ground surveys.[8] Data suggest that the woodcock population has fallen rangewide by an average of 1.1% yearly over the last four decades.[6]

Conservation

The American woodcock is not considered globally threatened by the IUCN. It is more tolerant of deforestation than other woodcocks and snipes; as long as some sheltered woodland remains for breeding, it can thrive even in regions that are mainly used for agriculture.[1][24] The estimated population is 5 million, so it is the most common sandpiper in North America.[17]

The American Woodcock Conservation Plan presents regional action plans linked to bird conservation regions, fundamental biological units recognized by the U.S. North American Bird Conservation Initiative. The Wildlife Management Institute oversees regional habitat initiatives intended to boost the American woodcock's population by protecting, renewing, and creating habitat throughout the species' range.[6]

Creating young-forest habitat for American woodcocks helps more than 50 other species of wildlife that need early successional habitat during part or all of their lifecycles. These include relatively common animals such as white-tailed deer, snowshoe hare, moose, bobcat, wild turkey, and ruffed grouse, and animals whose populations have also declined in recent decades, such as the golden-winged warbler, whip-poor-will, willow flycatcher, indigo bunting, and New England cottontail.[25]

Leslie Glasgow,[26] the assistant secretary of the Interior for Fish, Wildlife, Parks, and Marine Resources from 1969 to 1970, wrote a dissertation through Texas A&M University on the woodcock, with research based on his observations through the Louisiana State University (LSU) Agricultural Experiment Station. He was an LSU professor from 1948 to 1980 and an authority on wildlife in the wetlands.[27]

References

BirdLife International (2020). "Scolopax minor". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T22693072A182648054. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-3.RLTS.T22693072A182648054.en. Retrieved November 13, 2021.

The American Woodcock Today | Woodcock population and young forest habitat management. Timberdoodle.org. Retrieved on 2013-04-03.

Kaufman, Kenn (1996). Lives of North American Birds. Houghton Mifflin, pp. 225–226, ISBN 0618159886.

Sheldon, William G. (1971). Book of the American Woodcock. University of Massachusetts.

Cooper, T. R. & K. Parker (2009). American woodcock population status, 2009. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Laurel, Maryland.

Kelley, James; Williamson, Scot & Cooper, Thomas, eds. (2008). American Woodcock Conservation Plan: A Summary of and Recommendations for Woodcock Conservation in North America.

Smith, Christopher (2000). Field Guide to Upland Birds and Waterfowl. Wilderness Adventures Press, pp. 28–29, ISBN 1885106203.

Keppie, D. M. & R. M. Whiting Jr. (1994). American Woodcock (Scolopax minor), The Birds of North America.

"American Woodcock Identification, All About Birds, Cornell Lab of Ornithology". www.allaboutbirds.org. Retrieved September 27, 2020.

Jones, Michael P.; Pierce, Kenneth E.; Ward, Daniel (2007). "Avian vision: a review of form and function with special consideration to birds of prey". Journal of Exotic Pet Medicine. 16 (2): 69. doi:10.1053/j.jepm.2007.03.012.

Linnaeus, Carl (1758). Systema Naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (in Latin). Vol. 1 (10th ed.). Holmiae (Stockholm): Laurentii Salvii. p. 145.

Jobling, James A (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. p. 351. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

Peters, James Lee, ed. (1934). Check-List of Birds of the World. Vol. 2. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 278.

Amazing Bird Records. Trails.com (2010-07-27). Retrieved on 2013-04-03.

Sepik, G. F. and E. L. Derleth (1993). Habitat use, home range size, and patterns of moves of the American Woodcock in Maine. in Proc. Eighth Woodcock Symp. (Longcore, J. R. and G. F. Sepik, eds.) Biol. Rep. 16, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Washington, D.C.

Ohio Ornithological Society (2004). Annotated Ohio state checklist Archived 2004-07-18 at the Wayback Machine.

O'Brien, Michael; Crossley, Richard & Karlson, Kevin (2006). The Shorebird Guide. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, pp. 444–445, ISBN 0618432949.

Mann, Clive F. (1991). "Sunda Frogmouth Batrachostomus cornutus carrying its young" (PDF). Forktail. 6: 77–78. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 28, 2008.

Wasser, D. E.; Sherman, P. W. (2010). "Avian longevities and their interpretation under evolutionary theories of senescence". Journal of Zoology. 280 (2): 103. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2009.00671.x.

Bent, A. C. (1927). "Life histories of familiar North American birds: American Woodcock, Scalopax minor". United States National Museum Bulletin. Smithsonian Institution. 142 (1): 61–78.

"American Woodcock". Audubon. National Audubon Society. Retrieved October 5, 2023.

Heinrich, Bernd (March 1, 2016). "Note on the Woodcock Rocking Display". Northeastern Naturalist. 23 (1): N4–N7.

Alcock, John (2013). Animal behavior: an evolutionary approach (10th ed.). Sunderland (Mass.): Sinauer. p. 522. ISBN 0878939660.

Henninger, W. F. (1906). "A preliminary list of the birds of Seneca County, Ohio" (PDF). Wilson Bulletin. 18 (2): 47–60.

the Woodcock Management Plan. Timberdoodle.org. Retrieved on 2013-04-03.

[1]Paul Y. Burns (June 13, 2008). "Leslie L. Glasgow". lsuagcdenter.com. Retrieved October 21, 2014.

Further readingChoiniere, Joe (2006). Seasons of the Woodcock: The secret life of a woodland shorebird. Sanctuary 45(4): 3–5. Sepik, Greg F.; Owen, Roy & Coulter, Malcolm (1981). A Landowner's Guide to Woodcock Management in the Northeast, Misc. Report 253, Maine Agricultural Experiment Station, University of Maine.

External linksAmerican woodcock species account – Cornell Lab of Ornithology American Woodcock – Scolopax minor – USGS Patuxent Bird Identification Infocenter American Woodcock Bird Sound Rite of Spring – Illustrated account of the phenomenal courtship flight of the male American woodcock American Woodcock videos[permanent dead link] on the Internet Bird Collection Photo-High Res; Article – www.fws.gov–"Moosehorn National Wildlife Refuge", photo gallery and analysis American Woodcock Conservation Plan A Summary of and Recommendations for Woodcock Conservation in North America Timberdoodle.org: the Woodcock Management Plan Sepik, Greg F.; Ray B. Owen Jr.; Malcolm W. Coulter (July 1981). "Landowner's Guide to Woodcock Management in the Northeast". Maine Agricultural Experiment Station Miscellaneous Report 253. vte

Sandpipers (family: Scolopacidae)

Taxon identifiers Wikidata: Q694319 Wikispecies: Scolopax minor ABA: amewoo ADW: Scolopax_minor ARKive: scolopax-minor Avibase: F4829920F1710E56 BirdLife: 22693072 BOLD: 10164 CoL: 6XXHP BOW: amewoo eBird: amewoo EoL: 45509171 Euring: 5310 FEIS: scmi Fossilworks: 129789 GBIF: 2481695 GNAB: american-woodcock iNaturalist: 3936 IRMNG: 10836458 ITIS: 176580 IUCN: 22693072 NatureServe: 2.105226 NCBI: 56299 ODNR: american-woodcock WoRMS: 159027 Xeno-canto: Scolopax-minor

Categories:IUCN Red List least concern speciesScolopaxNative birds of the Eastern United StatesNative birds of Eastern CanadaBirds of MexicoBirds described in 1789Taxa named by Johann Friedrich Gmelin

The American woodcock (Scolopax minor), sometimes colloquially referred to as the timberdoodle,[2] is a small shorebird species found primarily in the eastern half of North America. Woodcocks spend most of their time on the ground in brushy, young-forest habitats, where the birds' brown, black, and gray plumage provides excellent camouflage.

The American woodcock is the only species of woodcock inhabiting North America.[3] Although classified with the sandpipers and shorebirds in the family Scolopacidae, the American woodcock lives mainly in upland settings. Its many folk names include timberdoodle, bogsucker, night partridge, brush snipe, hokumpoke, and becasse.[4]

The population of the American woodcock has fallen by an average of slightly more than 1% annually since the 1960s. Most authorities attribute this decline to a loss of habitat caused by forest maturation and urban development. Because of the male woodcock's unique, beautiful courtship flights, the bird is welcomed as a harbinger of spring in northern areas. It is also a popular game bird, with about 540,000 killed annually by some 133,000 hunters in the U.S.[5]

In 2008, wildlife biologists and conservationists released an American woodcock conservation plan presenting figures for the acreage of early successional habitat that must be created and maintained in the U.S. and Canada to stabilize the woodcock population at current levels, and to return it to 1970s densities.[6]

Description

The American woodcock has a plump body, short legs, a large, rounded head, and a long, straight prehensile bill. Adults are 10 to 12 inches (25 to 30 cm) long and weigh 5 to 8 ounces (140 to 230 g).[7] Females are considerably larger than males.[8] The bill is 2.5 to 2.8 inches (6.4 to 7.1 cm) long.[4] Wingspans range from 16.5 to 18.9 inches (42 to 48 cm).[9]

Illustration of American woodcock head and wing feathers

Woodcock, with attenuate primaries, natural size, 1891

The plumage is a cryptic mix of different shades of browns, grays, and black. The chest and sides vary from yellowish-white to rich tans.[8] The nape of the head is black, with three or four crossbars of deep buff or rufous.[4] The feet and toes, which are small and weak, are brownish gray to reddish brown.[8] Woodcocks have large eyes located high in their heads, and their visual field is probably the largest of any bird, 360° in the horizontal plane and 180° in the vertical plane.[10]

The woodcock uses its long, prehensile bill to probe in the soil for food, mainly invertebrates and especially earthworms. A unique bone-and-muscle arrangement lets the bird open and close the tip of its upper bill, or mandible, while it is sunk in the ground. Both the underside of the upper mandible and the long tongue are rough-surfaced for grasping slippery prey.[4]

Taxonomy

The genus Scolopax was introduced in 1758 by the Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus in the tenth edition of his Systema Naturae.[11] The genus name is Latin for a snipe or woodcock.[12] The type species is the Eurasian woodcock (Scolopax rusticola).[13]

Distribution and habitat

Woodcocks inhabit forested and mixed forest-agricultural-urban areas east of the 98th meridian. Woodcock have been sighted as far north as York Factory, Manitoba, and east to Labrador and Newfoundland. In winter, they migrate as far south as the Gulf Coast of the United States and Mexico.[8]

The primary breeding range extends from Atlantic Canada (Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, and New Brunswick) west to southeastern Manitoba, and south to northern Virginia, western North Carolina, Kentucky, northern Tennessee, northern Illinois, Missouri, and eastern Kansas. A limited number breed as far south as Florida and Texas. The species may be expanding its distribution northward and westward.[8]

After migrating south in autumn, most woodcocks spend the winter in the Gulf Coast and southeastern Atlantic Coast states. Some may remain as far north as southern Maryland, eastern Virginia, and southern New Jersey. The core of the wintering range centers on Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia.[8] Based on the Christmas Bird Count results, winter concentrations are highest in the northern half of Alabama.

American woodcocks live in wet thickets, moist woods, and brushy swamps.[3] Ideal habitats feature early successional habitat and abandoned farmland mixed with forest. In late summer, some woodcocks roost on the ground at night in large openings among sparse, patchy vegetation.[8]Courtship/breeding habitats include forest openings, roadsides, pastures, and old fields from which males call and launch courtship flights in springtime. Nesting habitats include thickets, shrubland, and young to middle-aged forest interspersed with openings. Feeding habitats have moist soil and feature densely growing young trees such as aspen (Populus spp.), birch (Betula spp.), and mixed hardwoods less than 20 years of age, and shrubs, particularly alder (Alnus spp.). Roosting habitats are semiopen sites with short, sparse plant cover, such as blueberry barrens, pastures, and recently heavily logged forest stands.[8]

Migration

Woodcocks migrate at night. They fly at low altitudes, individually or in small, loose flocks. Flight speeds of migrating birds have been clocked at 16 to 28 mi/h (26 to 45 km/h). However, the slowest flight speed ever recorded for a bird, 5 mi/h (8 km/h), was recorded for this species.[14] Woodcocks are thought to orient visually using major physiographic features such as coastlines and broad river valleys.[8] Both the autumn and spring migrations are leisurely compared with the swift, direct migrations of many passerine birds.

In the north, woodcocks begin to shift southward before ice and snow seal off their ground-based food supply. Cold fronts may prompt heavy southerly flights in autumn. Most woodcocks start to migrate in October, with the major push from mid-October to early November.[15] Most individuals arrive on the wintering range by mid-December. The birds head north again in February. Most have returned to the northern breeding range by mid-March to mid-April.[8]

Migrating birds' arrival at and departure from the breeding range is highly irregular. In Ohio, for example, the earliest birds are seen in February, but the bulk of the population does not arrive until March and April. Birds start to leave for winter by September, but some remain until mid-November.[16]

Behavior and ecology

Food and feeding

American woodcock catching a worm in a New York City park

Woodcocks eat mainly invertebrates, particularly earthworms (Oligochaeta). They do most of their feeding in places where the soil is moist. They forage by probing in soft soil in thickets, where they usually remain well-hidden. Other items in their diet include insect larvae, snails, centipedes, millipedes, spiders, snipe flies, beetles, and ants. A small amount of plant food is eaten, mainly seeds.[8] Woodcocks are crepuscular, being most active at dawn and dusk.

Breeding

In spring, males occupy individual singing grounds, openings near brushy cover from which they call and perform display flights at dawn and dusk, and if the light levels are high enough, on moonlit nights. The male's ground call is a short, buzzy peent. After sounding a series of ground calls, the male takes off and flies from 50 to 100 yd (46 to 91 m) into the air. He descends, zigzagging and banking while singing a liquid, chirping song.[8] This high spiralling flight produces a melodious twittering sound as air rushes through the male's outer primary wing feathers.[17]

Males may continue with their courtship flights for as many as four months running, sometimes continuing even after females have already hatched their broods and left the nest. Females, known as hens, are attracted to the males' displays. A hen will fly in and land on the ground near a singing male. The male courts the female by walking stiff-legged and with his wings stretched vertically, and by bobbing and bowing. A male may mate with several females. The male woodcock plays no role in selecting a nest site, incubating eggs, or rearing young. In the primary northern breeding range, the woodcock may be the earliest ground-nesting species to breed.[8]

Woodcock chick in nest

Downy young are already well-camouflaged.

The hen makes a shallow, rudimentary nest on the ground in the leaf and twig litter, in brushy or young-forest cover usually within 150 yd (140 m) of a singing ground.[4] Most hens lay four eggs, sometimes one to three. Incubation takes 20 to 22 days.[3] The down-covered young are precocial and leave the nest within a few hours of hatching.[8] The female broods her young and feeds them. When threatened, the fledglings usually take cover and remain motionless, attempting to escape detection by relying on their cryptic coloration. Some observers suggest that frightened young may cling to the body of their mother, that will then take wing and carry the young to safety.[18] Woodcock fledglings begin probing for worms on their own a few days after hatching. They develop quickly and can make short flights after two weeks, can fly fairly well at three weeks, and are independent after about five weeks.[3]

The maximum lifespan of adult American woodcock in the wild is 8 years.[19]

Rocking behavior

American woodcocks sometimes rock back and forth as they walk, perhaps to aid their search for worms.

American woodcocks occasionally perform a rocking behavior where they will walk slowly while rhythmically rocking their bodies back and forth. This behavior occurs during foraging, leading ornithologists such as Arthur Cleveland Bent and B. H. Christy to theorize that this is a method of coaxing invertebrates such as earthworms closer to the surface.[20] The foraging theory is the most common explanation of the behavior, and it is often cited in field guides.[21]

An alternative theory for the rocking behavior has been proposed by some biologists, such as Bernd Heinrich. It is thought that this behavior is a display to indicate to potential predators that the bird is aware of them.[22] Heinrich notes that some field observations have shown that woodcocks will occasionally flash their tail feathers while rocking, drawing attention to themselves. This theory is supported by research done by John Alcock who believes this is a type of aposematism.[23]

Population status

How many woodcock were present in eastern North America before European settlement is unknown. Colonial agriculture, with its patchwork of family farms and open-range livestock grazing, probably supported healthy woodcock populations.[4]

The woodcock population remained high during the early and mid-20th century, after many family farms were abandoned as people moved to urban areas, and crop fields and pastures grew up in brush. In recent decades, those formerly brushy acres have become middle-aged and older forest, where woodcock rarely venture, or they have been covered with buildings and other human developments. Because its population has been declining, the American woodcock is considered a "species of greatest conservation need" in many states, triggering research and habitat-creation efforts in an attempt to boost woodcock populations.

Population trends have been measured through springtime breeding bird surveys, and in the northern breeding range, springtime singing-ground surveys.[8] Data suggest that the woodcock population has fallen rangewide by an average of 1.1% yearly over the last four decades.[6]

Conservation

The American woodcock is not considered globally threatened by the IUCN. It is more tolerant of deforestation than other woodcocks and snipes; as long as some sheltered woodland remains for breeding, it can thrive even in regions that are mainly used for agriculture.[1][24] The estimated population is 5 million, so it is the most common sandpiper in North America.[17]

The American Woodcock Conservation Plan presents regional action plans linked to bird conservation regions, fundamental biological units recognized by the U.S. North American Bird Conservation Initiative. The Wildlife Management Institute oversees regional habitat initiatives intended to boost the American woodcock's population by protecting, renewing, and creating habitat throughout the species' range.[6]

Creating young-forest habitat for American woodcocks helps more than 50 other species of wildlife that need early successional habitat during part or all of their lifecycles. These include relatively common animals such as white-tailed deer, snowshoe hare, moose, bobcat, wild turkey, and ruffed grouse, and animals whose populations have also declined in recent decades, such as the golden-winged warbler, whip-poor-will, willow flycatcher, indigo bunting, and New England cottontail.[25]

Leslie Glasgow,[26] the assistant secretary of the Interior for Fish, Wildlife, Parks, and Marine Resources from 1969 to 1970, wrote a dissertation through Texas A&M University on the woodcock, with research based on his observations through the Louisiana State University (LSU) Agricultural Experiment Station. He was an LSU professor from 1948 to 1980 and an authority on wildlife in the wetlands.[27]

References

BirdLife International (2020). "Scolopax minor". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T22693072A182648054. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-3.RLTS.T22693072A182648054.en. Retrieved November 13, 2021.

The American Woodcock Today | Woodcock population and young forest habitat management. Timberdoodle.org. Retrieved on 2013-04-03.

Kaufman, Kenn (1996). Lives of North American Birds. Houghton Mifflin, pp. 225–226, ISBN 0618159886.

Sheldon, William G. (1971). Book of the American Woodcock. University of Massachusetts.

Cooper, T. R. & K. Parker (2009). American woodcock population status, 2009. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Laurel, Maryland.

Kelley, James; Williamson, Scot & Cooper, Thomas, eds. (2008). American Woodcock Conservation Plan: A Summary of and Recommendations for Woodcock Conservation in North America.

Smith, Christopher (2000). Field Guide to Upland Birds and Waterfowl. Wilderness Adventures Press, pp. 28–29, ISBN 1885106203.

Keppie, D. M. & R. M. Whiting Jr. (1994). American Woodcock (Scolopax minor), The Birds of North America.

"American Woodcock Identification, All About Birds, Cornell Lab of Ornithology". www.allaboutbirds.org. Retrieved September 27, 2020.

Jones, Michael P.; Pierce, Kenneth E.; Ward, Daniel (2007). "Avian vision: a review of form and function with special consideration to birds of prey". Journal of Exotic Pet Medicine. 16 (2): 69. doi:10.1053/j.jepm.2007.03.012.

Linnaeus, Carl (1758). Systema Naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (in Latin). Vol. 1 (10th ed.). Holmiae (Stockholm): Laurentii Salvii. p. 145.

Jobling, James A (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. p. 351. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

Peters, James Lee, ed. (1934). Check-List of Birds of the World. Vol. 2. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 278.

Amazing Bird Records. Trails.com (2010-07-27). Retrieved on 2013-04-03.

Sepik, G. F. and E. L. Derleth (1993). Habitat use, home range size, and patterns of moves of the American Woodcock in Maine. in Proc. Eighth Woodcock Symp. (Longcore, J. R. and G. F. Sepik, eds.) Biol. Rep. 16, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Washington, D.C.

Ohio Ornithological Society (2004). Annotated Ohio state checklist Archived 2004-07-18 at the Wayback Machine.

O'Brien, Michael; Crossley, Richard & Karlson, Kevin (2006). The Shorebird Guide. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, pp. 444–445, ISBN 0618432949.

Mann, Clive F. (1991). "Sunda Frogmouth Batrachostomus cornutus carrying its young" (PDF). Forktail. 6: 77–78. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 28, 2008.

Wasser, D. E.; Sherman, P. W. (2010). "Avian longevities and their interpretation under evolutionary theories of senescence". Journal of Zoology. 280 (2): 103. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2009.00671.x.

Bent, A. C. (1927). "Life histories of familiar North American birds: American Woodcock, Scalopax minor". United States National Museum Bulletin. Smithsonian Institution. 142 (1): 61–78.

"American Woodcock". Audubon. National Audubon Society. Retrieved October 5, 2023.

Heinrich, Bernd (March 1, 2016). "Note on the Woodcock Rocking Display". Northeastern Naturalist. 23 (1): N4–N7.

Alcock, John (2013). Animal behavior: an evolutionary approach (10th ed.). Sunderland (Mass.): Sinauer. p. 522. ISBN 0878939660.

Henninger, W. F. (1906). "A preliminary list of the birds of Seneca County, Ohio" (PDF). Wilson Bulletin. 18 (2): 47–60.

the Woodcock Management Plan. Timberdoodle.org. Retrieved on 2013-04-03.

[1]Paul Y. Burns (June 13, 2008). "Leslie L. Glasgow". lsuagcdenter.com. Retrieved October 21, 2014.

Further readingChoiniere, Joe (2006). Seasons of the Woodcock: The secret life of a woodland shorebird. Sanctuary 45(4): 3–5. Sepik, Greg F.; Owen, Roy & Coulter, Malcolm (1981). A Landowner's Guide to Woodcock Management in the Northeast, Misc. Report 253, Maine Agricultural Experiment Station, University of Maine.

External linksAmerican woodcock species account – Cornell Lab of Ornithology American Woodcock – Scolopax minor – USGS Patuxent Bird Identification Infocenter American Woodcock Bird Sound Rite of Spring – Illustrated account of the phenomenal courtship flight of the male American woodcock American Woodcock videos[permanent dead link] on the Internet Bird Collection Photo-High Res; Article – www.fws.gov–"Moosehorn National Wildlife Refuge", photo gallery and analysis American Woodcock Conservation Plan A Summary of and Recommendations for Woodcock Conservation in North America Timberdoodle.org: the Woodcock Management Plan Sepik, Greg F.; Ray B. Owen Jr.; Malcolm W. Coulter (July 1981). "Landowner's Guide to Woodcock Management in the Northeast". Maine Agricultural Experiment Station Miscellaneous Report 253. vte

Sandpipers (family: Scolopacidae)

Taxon identifiers Wikidata: Q694319 Wikispecies: Scolopax minor ABA: amewoo ADW: Scolopax_minor ARKive: scolopax-minor Avibase: F4829920F1710E56 BirdLife: 22693072 BOLD: 10164 CoL: 6XXHP BOW: amewoo eBird: amewoo EoL: 45509171 Euring: 5310 FEIS: scmi Fossilworks: 129789 GBIF: 2481695 GNAB: american-woodcock iNaturalist: 3936 IRMNG: 10836458 ITIS: 176580 IUCN: 22693072 NatureServe: 2.105226 NCBI: 56299 ODNR: american-woodcock WoRMS: 159027 Xeno-canto: Scolopax-minor

Categories:IUCN Red List least concern speciesScolopaxNative birds of the Eastern United StatesNative birds of Eastern CanadaBirds of MexicoBirds described in 1789Taxa named by Johann Friedrich Gmelin

#pro rq 🌈🍓#radqueer#rq#rq community#rq please interact#rq safe#rq 🌈🍓#rqc🌈🍓#transid#pro radqueer#radqueers please interact#radqueer safe

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Window strikes are an issue in almost every major U.S. city. Birds don’t see clear or reflective glass and don’t understand it’s a lethal barrier. When they see plants or bushes through windows or reflected in them, they head for them, killing themselves in the process.

Birds that migrate at night, like sparrows and warblers, rely on the stars to navigate. Bright lights from buildings both attract and confuse them, leading to window strikes or birds flying around the lights until they die from exhaustion — a phenomenon known as fatal light attraction. In 2017, for example, almost 400 passerines became disoriented in a Galveston, Texas, skyscraper’s floodlights and died in collisions with windows.

“Unfortunately, it is really common,” said Matt Igleski, executive director of the Chicago Audubon Society. “We see this in pretty much every major city during spring and fall migration. This (the window strikes at McCormick Place) was a very catastrophic single event, but when you add it all up (across the country), it’s always like that.”

[...] Window strikes and fatal light attraction are easily preventable, said Anna Pidgeon, an avian ecologist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Building managers can simply dim their lights, she said, and architects can design windows with markings in the glass that birds can easily recognize. People can add screens, paint their windows or apply decals to the glass as well.

New York City has taken to shutting off the twin beams of light symbolizing the World Trade Center for periods of time during its annual Sept. 11 memorial ceremony to prevent birds from becoming trapped in the light shafts. The National Audubon Society launched a program in 1999 called Lights Out, an effort to encourage urban centers to turn off or dim lights during migration months. Nearly 50 U.S. and Canadian cities have joined the movement, including Toronto, New York, Boston, San Diego, Dallas and Miami.

Chicago also participates in the Lights Out program. The city council in 2020 passed an ordinance requiring bird safety measures in new buildings but has yet to implement the requirements. The first buildings at McCormick Place were constructed in 1959.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Unofficial Black History Book

Juneteenth (June 19th, 1865)

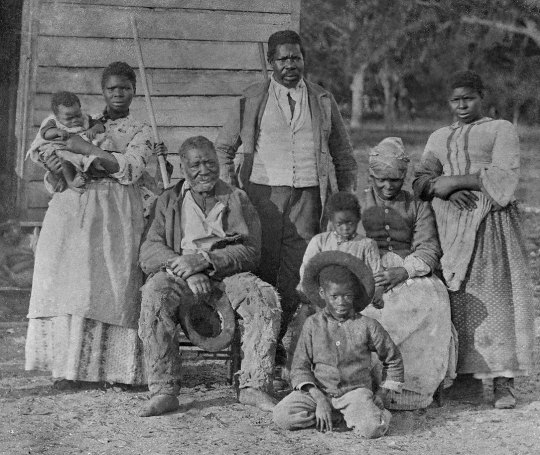

Everyone knows Juneteenth as the holiday commemorating the end of slavery in the United States.

But not everyone knows that the slaves weren't officially free.

This is the story.

Juneteenth National Independence Day, also known as Black Independence Day, Emancipation Day, Freedom Day, Jubilee Day, and Juneteenth Independence Day, is a holiday commemorating the end of slavery in the United States, observed annually on June 19th.

Juneteenth honors the end of slavery in the United States and is considered the longest-running African-American holiday.

Juneteenth, short for "June Nineteenth," marks the day in 1895 that Federal troops arrived in Galveston, Texas, to take control of the state and ensure that all slaves were freed. The troops' arrival came almost two and a half years after the Emancipation Proclamation.

Two months earlier, Confederate General Robert E. Lee had surrendered at Appomattox Courthouse in Virginia, but slavery had remained relatively unaffected in Texas -- Until U.S. General Gordon stood on Texas soil and read General Orders No. 3: "The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a Proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free."

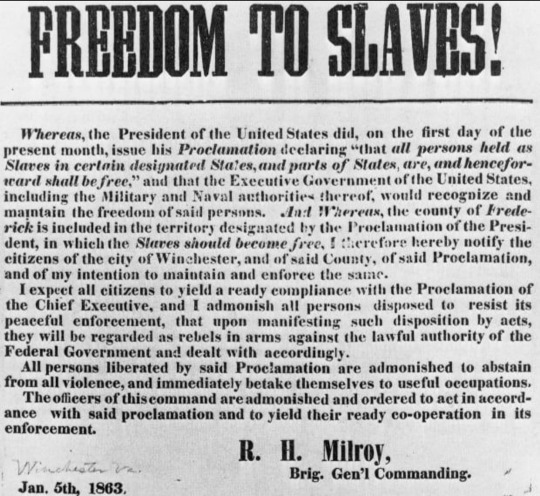

The Emancipation Proclamation

On January 1st, 1863, The Emancipation Proclamation was issued by President Abraham Lincoln. It established that all enslaved people in the Confederate state in rebellion against the Union "shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free."

However, The Emancipation did not immediately set the slaves free.

The Proclamation only applied to places under Confederate control and not to slave-holding border states or rebel areas already under Union control. But when Northern troops advanced into the Confederate South, many slaves fled behind Union lines.

In Texas, slavery continued as the state experienced no large-scale fighting or a significant presence of Union troops. Many slave masters from outside of Texas had moved there, as they viewed it as a safe haven for slavery.

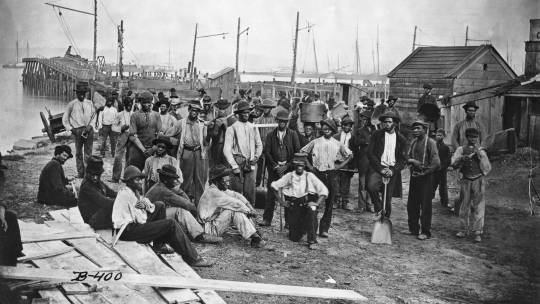

After the war ended in the spring of 1865, General Granger's arrival in Galveston the following June signaled freedom for the 250,000 slaves in Texas. Although emancipation didn't happen for everyone, slave masters withheld the information until after harvest season.

Celebrations broke out among newly freed African-Americans, and that was the beginning of Juneteenth. The following December, slavery in America was formally abolished with the adoption of the 13th Amendment.

On June 19th, 1865, freedmen in Texas organized the first annual "Jubilee Day". In the following decades, Juneteenth celebrations featured barbecues, music, prayer services, and other activities, and as African Americans migrated from Texas to other parts of the country, so did the Juneteenth tradition.

In 1979, Texas became the first state to make Juneteenth an official holiday, other states followed over the years. In June 2021, Congress passed a resolution establishing Juneteenth as a national holiday. On June 17th, 2021, President Biden officially signed it into law. 160 years later, it officially became a federal holiday.

__

Previous

Janet Collins

Next

Mary Beatrice Davidson Kenner

__

My Resources

#juneteenth#black history matters#black history 365#black history is american history#black culture#black history#know your history#learn your roots#freeish#black history facts#history#human rights#freeish since 1865#freedom day#writers on tumblr#the unofficial black history book#black female writers#writing community#black stories#black tumblr#black activism

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Discovering the Optimal Season: The Best Time to Experience Big Bend Texas

Nestled along the Rio Grande in the vast expanse of West Texas, Big Bend National Park stands as a testament to nature's grandeur. Spanning over 800,000 acres, this rugged wilderness offers a myriad of outdoor adventures, from hiking through towering canyons to stargazing under the vast desert sky. But when is the best time to visit this remote and awe-inspiring destination? Let's unravel the seasons of Big Bend and discover the optimal time to experience its wonders.

Spring: March to May

As winter loosens its grip and the desert begins to bloom, spring emerges as one of the prime seasons to visit Big Bend. Temperatures are mild, ranging from comfortable highs in the 70s to cooler evenings. Wildflowers carpet the desert floor in a riot of color, creating a stunning backdrop for hiking and photography. Spring also marks the peak of bird migration, making it a paradise for birdwatchers.

Summer: June to August

While summer in Big Bend brings scorching temperatures, reaching well over 100 degrees Fahrenheit, it also offers unique opportunities for adventure. For those willing to brave the heat, summer presents the chance to explore the park's trails and waterways with fewer crowds. Early mornings and late evenings provide a reprieve from the intense sun, allowing visitors to experience the park's beauty in relative solitude. Just be sure to stay hydrated and seek shade during the hottest hours of the day.

Fall: September to November

As summer wanes and the temperatures begin to cool, fall unveils its splendor in Big Bend. Crisp mornings give way to pleasant days, making outdoor activities all the more enjoyable. Fall also brings the annual Monarch butterfly migration, as well as opportunities to witness the changing colors of the desert foliage. With fewer visitors compared to the spring season, fall offers a tranquil and immersive experience amidst the rugged beauty of Big Bend.

Winter: December to February

While winter may not be the most popular time to visit Big Bend, it holds its own charm for those seeking solitude and serenity. Daytime temperatures are mild, ranging from the 50s to 60s, perfect for hiking and exploring the park's diverse landscapes. Clear skies and low humidity create ideal conditions for stargazing, offering unparalleled views of the Milky Way against the backdrop of the desert night.

In conclusion, the best time to visit Big Bend depends on your preferences and tolerance for weather extremes. Whether you're drawn to the vibrant blooms of spring, the solitude of summer, the colors of fall, or the tranquility of winter, each season offers its own unique opportunities to experience the magic of this remote wilderness. So pack your bags, prepare for adventure, and embark on a journey to discover the wonders of Big Bend, Texas, no matter the season.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

New York mayor 'shocked' that migrant children as young as nine months secretly sent to his city

New York's mayor said he was shocked that at least 239 minors arrived incognito after being separated from parents on the Mexican border.

While Donald Trump signed the end of a policy of separation of families at the border that provoked outrage in the United States and abroad, Democratic Mayor Bill de Blasio went into a a reception center for migrant children in Harlem, where a television crew had filmed the previous night some girls arriving secretly, apparently separated from their parents at the border.

The segregated minors included a nine-month-old baby and traumatized children, many with lice, bedbugs or contagious diseases.

Mr De Blasio emerged from the reception centre saying he was "shocked to learn" how many children separated from their parents had been sent to New York, explaining that this single center in Harlem had received 239 children without the knowledge of city authorities.

"How is it possible that none of us knew that there (were) 239 kids right here in our city?" he said. "How is the federal government holding back that information from the people of this city and holding back the help that these kids could need?"

"The mental health issues alone, they made clear to us, are very real; very painful," De Blasio stressed.

The Cayuga Center, which has classrooms in a six-story building across the street from an elevated train line, has a federal contract to place unaccompanied immigrant children in short-term foster care. Officials at the center did not immediately return phone calls seeking comment.

Mr De Blasio said the staff there told him it has taken in about 350 children since President Donald Trump's administration implemented its "zero tolerance" policy this spring calling for the criminal prosecution of all adults caught crossing the border illegally.

He is off to join other US mayors Thursday in Texas to visit a childcare center and denounce the migration policy of the Trump administration.

#New York mayor 'shocked' that migrant children as young as nine months secretly sent to his city#new york#migrants

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sen. Ted Cruz, R-Texas, released a graphic video highlighting the brutality of what he calls the "Narco slave trade" at the U.S.-Mexico border.

The video begins with Cruz and border officials tending to a group of migrants who crossed the border late in the night. He highlights that the vast majority of migrants are being economically exploited by the drug cartels bringing them into the U.S.

"These children come in in debt to vicious cartels thousands and thousands of dollars. The teenage boys work for the gangs in every city in America, and the teenage girls experience a hell worse than that, with far too many of them human trafficked into sex slavery," Cruz says in the video. "Joe Biden and Kamala Harris are responsible for the worst plague of slavery in America since the Civil War."

"This is not compassionate. This is not humane. This is barbaric," Cruz adds as the footage cycles graphic photos of migrants who have died attempting to cross the border.

President Biden's administration has presided over record-breaking border crossings in both 2021 and 2022.

The administration has repeatedly attempted to dismiss border surges as a yearly pattern, but while the southern border has seen a pattern of increases in migration each spring, the surges in both 2021 and 2022 far outpaced previous years.

Biden claimed in March 2021 that the border surge was "what happens every year." The U.S. saw 1.7 million border crossings by the end of that year, an all-time record.

2022 is expected to break that record, however.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ladderbacked Woodpecker - South Llano River State Park, Junction TX

Thanks to @zipzilla for catching my caption error!

225 notes

·

View notes

Text

Do American robins migrate?

american robins bird migration

Spring singer or snow sentinel?

The best known of the songbirds is the American robin, also known as the bird of North America. It is usually more common in winter. Now the question is: do robin birds migrate?

The answer is yes and no.

We usually say robins are winter birds but they are able to adapt to warm as well. But that doesn't mean they are immune to winter weather.

Winter Strategy

The opposite of Hummingbird is a native of far Durant. They are concentrated in the south most of the time. They usually react during winter in two ways.

Robins can also tolerate very cold weather. Many are moving south. The northern Canada robin vacates many wintering flocks of birds as far south as Texas and Florida. Birds that come and go are not used to hot weather. They have a similar body structure and add warm, downy feathers to their plumage.

As food decreases in warmer weather, they begin to search for food supplies due to the scarcity of insects and insects. Food is usually the main motivation of such birds.

Declining insect or invertebrate numbers aren't a problem for everyone - and a good number tend to be in the north, which is another way robin birds respond to winter.

They took observations in southern Canadian provinces and US state locations in January. They are seen occupying several important places.

By changing the diet they usually turn to vitamin-rich invertebrates and winter fruits including juniper, holly, crabapple and hawthorn.

During summer and spring robin birds aggressively defend their territory and raise their young. During the winter season they become nomadic and engage in intense quest to regain their beloved cold weather.

Robins speed up in the weather, too. They can confirm their position in case of heavy snowfall.

Robin bird also roams around stealing jays in winter and these jays which may number hundreds or thousands. In summer and spring, the birds form opposite territorial pairs.

Flocking offers important benefits:

A group of them have large eyes that can quickly spot any predator. They are one of the most adept at discovering food.

Finally, robins usually make little noise in winter. They all live together. As spring arrives, they begin to sing and produce mating hormones. They usually maintain a flexible presence.

For some changes and and dramatically reduces the profile of robins or their populations, making them common and leading some people to assume their absence.

So how do robins decide whether to stay or leave for the winter?

This is not precisely answered but gender may play a role. Male birds are more likely than females, usually in northern areas. It clearly provides territorial advantages that allow men to be preemptively inserted into chiefdoms everywhere.

Spring actually causes northern flocks of robins to disperse and resume their invertebrate diet. such as picking and eating earthworms and other vertebrates from the soil. At the same time the robins with migraines return from the southern region. Males usually arrive two to three weeks earlier than females. Males on both sides sing very loudly as they begin to defend territory. The result?

when american robins are everywhere?

People think robins are everywhere now.

Save the Robin

Like other birds, the robin seems to have greatly benefited the development of birding and agriculture. Population is increasing which is a threat to any adaptation Yajna tribes are vulnerable to many of the same factors. Moreover, pesticide poisoning poses an important threat to their conservation. Because the American robin roams lawns and other open spaces that are often poisoned areas and eats. Although DDT has been banned in the United States, it is known as a toxic chemical.

Examples include neonicotinoids, chlorpyrifos and glyphosate (used in the well-known herbicide Roundup) still in use. Insecticides kill earthworms, which are a major part of the bird's diet. Because American robins mostly forage and feed on the ground, they pose a major threat to feral cats.

Moreover, the cars, towers and various electrical things and the current modern age of cars and networks are making their lives more difficult.

Various organizations have adopted this policy and are coming forward to help protect them from the dangers. It is better to save them to protect them in the society. Because many birds that are beneficial to society are leaving us and disappearing due to various reasons. Various ornithological organizations are working for birds.

Read the full article

0 notes

Text

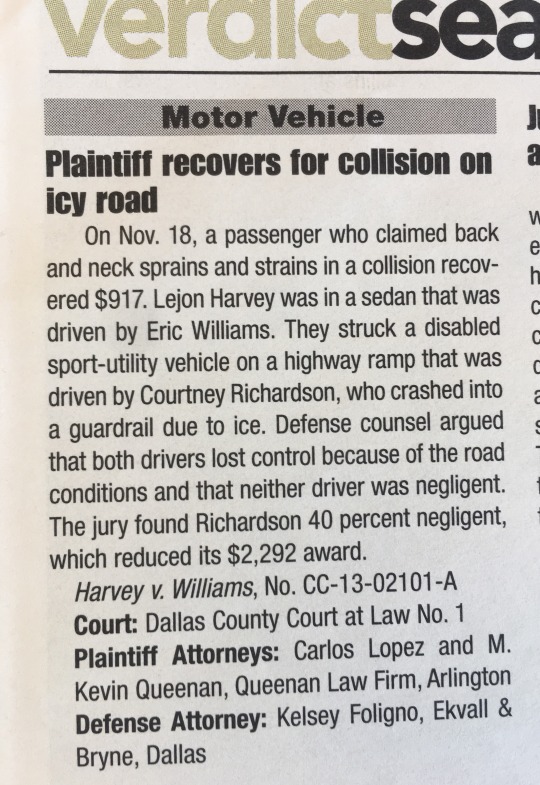

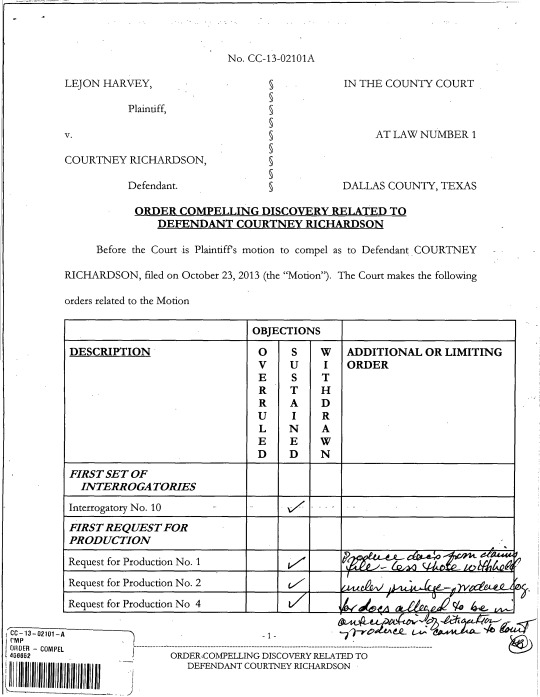

Court: Dallas County Court at Law No. 1

CC-08-09410

CC-13-05556-A

CC-13-02101-A

TEXAS RULES OF EVIDENCE 609 (F) REQUEST FOR NOTICE BY PLAINTIFF'S INTENT TO IMPEACH BY EVIDENCE OF CONVICTION OF A CRIME

02/07/2014 ORDER - COMPEL

COSTS

CC-13-01948-E

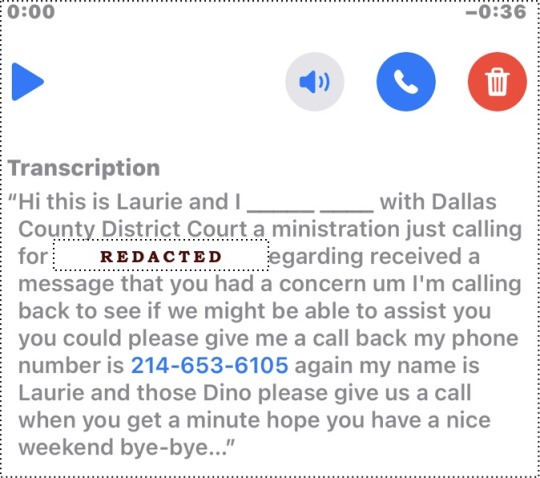

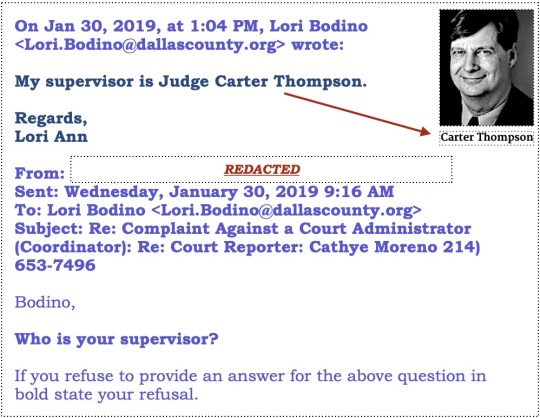

ANY QUESTIONS CALL GILBERT 214-653-7556

dallasnews.com

Bungled rollout of Dallas County software has clouded court activity

We’ve long had concerns about the work ethic of Dallas County’s felony court judges.

Their slow progress at chipping away at the huge backlog of cases amassed during the pandemic has been the topic of several editorials in the last two years.