#Semitone Sounds

Text

pitched up Thom Yorke... if you even care...

#radiohead#audacity#this turned out WAY better than I expected lmao#I tried it with a Pearl Jam song originally and that sounded garbage. I think it has something to do with Thom's singing style#I almost pitched this up one more semitone but then I didn't like it that much anymore

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

i may have made another italy ai cover because it's fun :3 here's another one in italian. this is dove e quando by benji e fede.

#i've made so many of these i haven't posted if anyone was curious...... it's so much fun#hetalia#hetalia ai cover#ai cover#aph italy#hws italy#i also upped this by a semitone bc i thought it sounded overall more like him that way#if i wanted to change my mind its TOO LATE this took too long to edit out the glitchy parts to redo it#i might make a cover w/ america soon.... but who knows

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’ve decided to learn the clarinet and on one hand wow learning an instrument as an adult is so much easier than as a kid?? I’m two days in and feel confident with the fingerings of two octaves of G major (tone is... a work in progress).

On the other hand, coming from a flute, the register key and the SHEER NUMBER of keys on this thing break my brain. Why can I press two different sets of keys to open or close the same exact holes? I mean? Sure, it’s convenient while my hands are learning what to do but also WHY was that necessary in the first place? And this whole tipping your hand to cover one hole but hit a different key simultaneously? Then there’s the register key nonsense? You mean you use the same fingerings, plus opening this tiny little hole, to raise the pitch??

#Personal#flute#clarinet#and yes I have experience with music theory#and yes I understand the concept of transposing#and transposing instruments#But I've only ever played C instruments#And it FRUSTRATES me that if I play a C on my flute it does not sound the same as a C on the clarinet#I can do the whole transpose up by x semitones#or transpose from key of x to key of y#but for SOME REASON#I can't actually wrap my head around it with an actual instrument#I get half way there then break completely

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

i just got totally distracted by trying to figure out the notes to that chord at the start of the mario galaxy overture that scared the balls out of me as a little kid and i always button mashed to get out of the title screen before it played but now it fills me with severe emotions. i call it either a Bmaj7add#5 or simply an Eb triad played on top of a B triad, theyre both essentially the same thing it just kinda depends on how you interpret the voicing

#anyway it makes total sense that the chord freaked me out as a baby cause 1) a 10 yr old does not know how to deal with dissonance and#2) the voicing is very open and spread out and pretty which sort of masks the sharp 5th but i guess i heard it very clearly despite that#the overture has the mario cadence in it so it goes from I to bVII to bVI which is that B chord it lands on#which sounds relatively upbeat but the addition of the sharp 5th and the major 7th add TWO semitone relations in the same chord#and like its spread out but. still definitely there.#i do love it a lot#ive already looked into this chord on several occasions through the years but i think this is the most accurate ive gotten#not that its like IMPOSSIBLE CHORD TO CRACK OMG OMG whatsoever but the extremely wide voicing has always thrown me off skjghskh#i havent looked at it in a few yrs now so i guess the sharp 5th didnt really occur to me back then#musical woes#um. yeah

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

one thing about me and my vocal synth covering adventures im learning is that there is nothing i hate more on this earth than having to pitch down a song to a different key to fit a different voicebanks range better. if i cant drop it a full octave down or two and have it work i am going to run deep into the woods never to be seen again

#i dont like pitching instrumentals down!!!!! its hard to do without it sounding weird!!!!!!#i also probably wouldnt like doing it up but i dont think ive really had a reason to most of the time#i tend to use mid-to-low range voices more often than not and i like a lot of high pitched songs LOL#but either way. if i cant just put it up or down 12 semitones i scream and cry and throw up and explode HJKDSJKFD

0 notes

Text

does anyone else ever have a few days between season changes where everything sounds slightly off pitch, or am i a weirdo

#teaposts#not fandom#idk i'm trying to listen to music rn but it sounds like it's been transposed down by a semitone or something#this happens like 1-2 times a year (toward the start of summer and winter respectively) so i think it's related to weather#but i don't really know why that would be

0 notes

Note

Idk the legality of it but there are some ppl you can pay to remake instrumentals, they might do their own take on it but mostly I see other utaite/youtaite use that versus other synth covers

i'd say it's kind of yikes if done with a song the instrumental of which the producer clearly doesn't want distributed tbh,,, as for the utaite thing i don't KNOW anything but i always thot that they ask the producer for the instrumental transposed to a different key instead of making their own version lol

#also. money </3#if your voice or the vb you're using is outside of the song's range#you can simply change the pitch of the instrumental by a few semitones in a progrum and use that version instead#but it can sound weird sometimes#so in my head it makes sense that they ask the og producer for a slightly altered version since they can do it with like 2 buttons#but i literally never looked into it LOL thats just what makes sense to me#also a side note#nicokara my beloved. although the quality is often so bad it makes me cry#ask

1 note

·

View note

Text

@ music side of tumblr why do some songs sound better in different keys???

#rachel rambles#i lowered spark again by aimer about 5 semitones in garageband and Y'ALL#i mean the voice sounds kinda terrifying but otherwise it slaps#explain plz???

0 notes

Text

the answer to "how low is too low": anything below -5 semitones starts to sound incoherent

865 notes

·

View notes

Note

Thoughts on Owen? I’ve been rewatching the og 3 seasons and seeing the change from finalist to gag character is weird

Owen is my Roman Empire.

He started off as an actual character in Island, which is a given since he was pre-determined to be a finalist from the get-go. Owen's always been a big personality of the series, with his (sometimes overbearing) friendliness and boisterous attitude, accompanied by his many many character flaws. But, at least in Island, he was realistically written- or as realistic as the show could do, given its parameters. He gets to have moments where he actually forms bonds and friendships with others on screen, and where his character flaws actually impact the challenge instead of being played off as jokes (like him luring in a bear with his hunting stories).

Owen's character traits were gradually reduced from being an optimistic and somewhat naïve, but otherwise standard teenage boy (of the time) to being a flanderisation of a golden retriever. In World Tour especially, he's rarely given any lines that don't somehow relate to his love of food, his flatulence or his fear of flying. For the span of an episode or two, he gets to focus on his feelings for Izzy (and he also gets some throwaway lines about his friendship with Noah and his trust-turned-distrust of Alejandro), but otherwise he's pretty self-contained as comedic relief.

He stops being a multi-faceted character and starts being a one-dimensional imitation of himself. And it's a shame, since Owen's one of the funniest characters to both watch and write for, so stripping him of a lot of his substance for the sake of delegating him to the role of background character, instead of just eliminating him early (since he didn't really have any use in World Tour outside of his aerophobia "plotline" and Izzy's elimination), seems like a waste of both his character potential and the potential of others.

And, one thing I noticed upon re-watching Island, even his voice becomes a sort-of mockery of what it started out as. No shade to Scott McCord, he does a fantastic job with his VA work- especially on Total Drama, where his characters are all distinctly different sounding. But really, go back and listen to Owen in early Island, and then listen to him in WT or RR- that's an entirely different cadence. He loses a lot of the scratchiness in his voice, and it raises a solid three or four semitones into something almost childish- once again playing into Owen's erosion from a fairly normal teenage boy into the caricature of naivety he eventually becomes.

We do get to see some of his original characterisation shine through in certain moments- there's a few lines he has in WT where Owen gets to be a little sassy or even somewhat confrontational, which is such a breath of fresh air from his usual airheaded happiness or aerophobia-fuelled terror. But he loses a lot of his season one charm with his delegation to the background; show me the Owen who's fun-loving, sure, but also a bit of a menace! Show me the Owen who's more than just the butt of a joke (pun intended)!

#in summary: owen very good 👍 needed LESS screen time to preserve his character#which could also apply to a lot of the other characters tbf#total drama#td owen#ophe rambling#replies

65 notes

·

View notes

Text

the chromatic scale is so funny

we divide pitches up into 12 distinct classes because it turns out if a tone has exactly twice the frequency of another they sound basically the same to our ears. Then since we needed something to name them after we went with good ol reliable letters of the alphabet,

and then becaue we were obsessed with the number 7 because of rainbows and jesus or whatever, we decided "okay seven of these notes are gonna get top billing and the other 5 are gonna be like, basically just the note between two of these other notes. And we're gonna decide to notate them as "this note but a semitone higher" or "this note but a semitone lower" at complete fucking random"

and then we needed something to call these 7 notes, so we went with ol' reliable, the letters of the alphabet. But then we realised, we, counted wrong??? and were like "okay no actully we want the first note of the octave (made up of 7 notes plus the one from the next octave (which cover 12 semitones)) to be C, the third letter of the alphabet"

so there you go

C C♯ D E♭ E F F♯ G G♯ A B♭ B and C again

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

“It went tick-tock like any other clock. But somehow, and against all usual horological practice the tick and the tock were irregular. Tick tock tick... and then the merest fraction of a second longer before ... tock tick tock... and then a tick a fraction of a second earlier than the mind's ear was now prepared for. The effect was enough, after ten minutes, to reduce the thinking processes of even the best-prepared to a sort of porridge.”

Terry Pratchett, Feet of Clay

-

Joel growled and swung his sword against the floor. It thunk.

The sword, not the floor, but Joel wouldn’t be surprised if the floor could think. It seemed to be mocking him, like everything else in this place. White, but not so white it could be mistaken as clean, with a musty tint to the walls and half-hearted bulbs showing off how ugly everything was. This room was just… nothing. Nothingness but with paperwork.

The tip of his sword absentmindedly snaked along the floor, etching the concrete.

“Please do not mistreat the premises.” Grian’s voice echoed down from above, his words barely making it through the cloud of bossa nova.

And, oh, yes, the music. Joel grit his teeth.

It was sweet and harmonious and incredibly annoying, like honey that had somehow rot. It rattled through the speakers and hung onto his ears. It droned on and on and on and wrapped itself around time and cheerfully bored it to death.

“Get on with it!” He hollered up at Grian.

Grian coughed. “Sir, please do not harass employees, or I’ll have to inform the manager.”

“You ARE the manager!”

The music continued. At least one thing was consistent.

Joel shifted in his chair. If he tried hard enough he could pretend he was in his base and this music was just relaxing accompaniment and not the soundtrack of his misery.

And, for a while, he did.

Before it jumped, for a split second, stuttering and scratching and clawing at the walls like someone was in there saying please let them out—

“What was that?” He leapt from his chair.

And then the music was back, the notes ambling along and giving him a reassuring pat on the shoulder as they passed.

Grian’s giggle floated down.

Joel’s chest pounded. Had he just imagined it? He must’ve.

The melody continued to tango in the dark, easily stepping up and down in a monotone rhythm.

Hold. A misstep. It was unmistakeable. A wrong note. But that couldn’t be, this was a recording. Joel clenched his fist. The music hastily regained its balance, but then— another one, more egregious than the first. His heart clenched in annoyance and threatened to kick at his throat.

The record stuttered again, coinciding with a wrong note, creating a grating effect. Something was wrong.

Two wrong notes in a row, and then a longer stutter, and then a whole phrase that was off by just a semitone, and another stutter a fraction shorter, and then growing slower, growing faster, and then—

Joel panted in panic, clutching his head, unsure why the sounds were bothering him so much, just wanting it to stop.

All at once, it screeched to a halt.

“Joel,” Grian singsonged from upstairs.

Gripping the hilt of his sword so hard his fingers shook, Joel climbed up the stairs and collapsed in front of the counter.

“You had a pleasant wait,” Grian said.

“I’m sorry?” Joel’s eye twitched.

“You had a pleasant wait?” Grian said.

“No.”

Grian shrugged and looked down at the form. “Either way, there seems to be an error here. Unfortunately, I’m going to have to put you back on hold.”

He put the record in, and the music started.

-

#grian#smallishbeans#hermitfic#hermitcraft#hermitcraft smp#hermitcraft season ten#hermitcraft season 10#hermitcraft s10#hermitcraft 10#hermitblr#hc s10#hc 10#hc

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

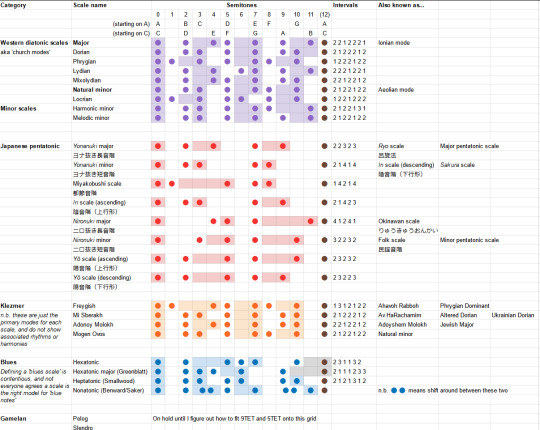

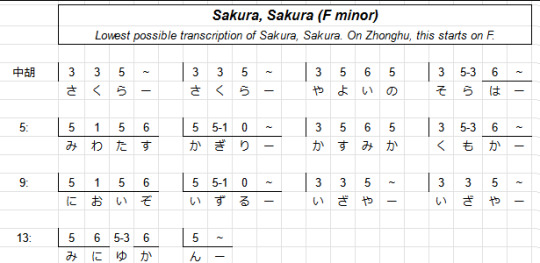

Music theory notes (for science bitches) - part 2: pentatonics and friends

or, the West ain't all that.

Hello again everyone! I'm grateful for the warm reception to the first music theory notes post (aka 'what is music? from first principles'). If you haven't read it, take a look~

In that stab at a first step towards 'what is music', I tried to distinguish between what's a relatively universal mathematical structure (nearly all musical systems have the octave) and what's an arbitrary convention. But in the end I did consciously limit myself, and make a beeline for the widely used 12TET tuning system and the diatonic scales used in Western music. I wanted to avoid overwhelming myself, and... 👻 it's all around us...👻

But! But but but. This is a series on music theory. Not just one music theory. The whole damn thing. I think I'm doing a huge disservice to everyone, not least me, if that's where we stop.

Today, then! For our second installation: 'Music theory notes (for science bitches)' will take a quick look through some examples that diverge from the diatonic scale: the erhu, Japanese pentatonic scales, gamelan, klezmer, and blues.

Also since the first part was quite abstract, we'll also having a go at using the tools we've built so far on a specific piece, the Edo-period folk song Sakura, Sakura.

Sound fun? Let's fucking gooooo

The story so far

To recap: in the first post we started by saying we're gonna be looking at tonal music, which isn't the only type of music. We introduced the idea of notes and frequencies by invoking the magic name of Fourier.

We said music can be approximated (for now) as an idealised pressure wave, which we can divide into brief windows called 'notes', and these notes are usually made of a strong sine wave at the 'fundamental frequency', plus a stack of further sine waves at integer multiples of that frequency called 'overtones'.

Then, we started constructing a culturally specific but extremely widespread system of creating structure between notes, known as '12 Tone Equal Temperament' or 12TET. The main character of this story is the interval, which is the ratio between the fundamental frequencies of two notes; we talked about how small-integer ratios of frequencies tend to be especially 'consonant' or nice-sounding.

We introduced the idea of the 'octave', which is when two notes have a frequency ratio of 2. We established the convention treating notes an octave apart as deeply related, to the point that we give them the same name. We also brought in the 'fifth', the ratio of 1.5, and talked about the idea of constructing a scale using small-integer ratios.

But we argued that if you try and build everything with those small-integer ratios you can dig yourself into a hole where moving around the musical space is rife with complications.

As a solution to this, I pulled out 'equal temperament' as an approximation with a lot of mathematical simplicity. Using a special irrational ratio called the "semitone" as a building block, we could construct the Western system of scales and modes and chords and such, where

a 'scale' is kind of like a palette for a piece of music, defined by a set of frequency ratios relative to a 'root' or 'tonic' note. this can be abstract, as in 'the major scale', or concrete, as in 'C major'.

a 'mode' is a cyclic permutation of an abstract scale. although it may contain the same notes, moving them around can change the feeling a lot!

a 'chord' is playing multiple notes at the same time. 'Triad' chords can be constructed from scales. There are other types which add or remove stuff from the triads. We'll come back to this.

I also summarised how sheet music works and the rather arbitrary choices in its construction, and at the end, I very briefly talked about chord notation.

There's a lot of ways to do this...

I recently watched a video by jazz musician and music theory youtuber Adam Neely, in which he and Philip Ewell discuss how much "music theory" is treated as synonymous with a very specific music theory which Neely glosses as "the harmonic style of 18th-century European composers". He argues, pretty convincingly imo, that 'music theory' pedagogy is seriously weakened by not taking non-white/Western models, such as Indian classical music theories, as a foil - citing Anuja Kamat's channel on Indian classical music as a great example of how to do things differently. Here's her introductory playlist on Indian classical music concepts, which I will hopefully be able to lean on in future posts:

There's two big pitfalls I wanna avoid as I teach myself music theory. I like maths a lot, and if I can fit something into a mathematical structure it's much easier for me to remember it - but I gotta be really careful not to mathwash some very arbitrary conventions and present them as more universal than they are. Music involves a lot of mathematics, but you can't reduce it to maths. It's a language for expressing emotion, not a predicate to prove.

One of the big goals of this series is to get straight in my head what has a good answer to 'why this way?', and what is just 'idk it's the convention we use'. And if something is an arbitrary convention, we gotta ask, what other conventions exist? Humans are inventive little buggers after all.

I also don't want to limit my analytical toolbox to a single 'hammer' of Western music theory, and try and force everything else into that frame. The reasons I'm learning music theory are... 1. to make my playing and singing better, and be more comfortable improvising; 2. to learn to compose stuff, which is currently a great mystery. How do they do it? I do like Western classical music, but honestly? Most of the music I enjoy is actually not Western. I want to be able to approach that music on its own terms.

For example, the erhu... for erhuample???

The instrument family I'm learning, erhu/zhonghu, is remarkably versatile - there are no frets (or even a soundboard!) to guide you, which is both a challenge and a huge freedom. You can absolutely play 12TET music on it, and it has a very beautiful sound - here is an erhu harmonising with a 12TET-tuned piano to play a song from the Princess Mononoke soundtrack, originally composed by Joe Hisaishi as an orchestral piece for the usual Western instruments...

youtube

This performance already makes heavy use of a technique called (in English) 'vibrato', where you oscillate the pitch around as you play the note (which means the whole construction that 'a note has a fixed pitch defined by a ratio' is actually an abstraction - now a note's 'frequency' represents the middle point a small range of pitches!). Vibrato is very common in Western music too, though the way you do it on an erhu and the way you do it on a violin or flute are of course a little different. (We could do an aside on Fourier analysis of vibrato here but I think that's another day's subject).

But if you listen to Chinese compositions specifically for Erhu, they take advantage of the lack of fixed pitch to zip up and down like crazy. Take the popular song Horse Racing for example, composed in the 1960s, which seems to be the closest thing to the 'iconic' erhu piece...

youtube

This can be notated in 12TET sheet music. But it's also taking full advantage of some of the unique qualities of the erhu's long string and lack of frets, like its ability to glide up and down notes, playing the full range of 'in between' frequencies on one string. The sheet music I linked there also has a notation style called 简谱 jiǎnpǔ which assigns numbers to notes. It's not so very different from Western sheet music, since it's still based on the diatonic major scale, but it's adjusted relative to the scale you're currently playing instead of always using C major. Erhu music very often includes very fast trills and a really skilled erhu/zhonghu player can jump between octaves with a level of confidence I find hard to comprehend.

I could spend this whole post putting erhu videos but let me just put one of the zhonghu specifically, which is a slightly deeper instrument; in Western terms the zhonghu (tuned to G and D) is the viola to the erhu's violin (tuned to D and A)...

youtube

To a certain degree, Chinese music is relatively easy to map across to the Western 12-tone chromatic scale. For example, the 十二律 shí'èr lǜ system uses essentially the same frequency ratios as the Pythagorean system. However, Chinese music generally makes much heavier use of pentatonic scales than Western music, and does not by default use equal temperament, instead using its own system of rational frequency ratios. correction: with the advent of Chinese orchestras in the mid-20thC, it seems that Chinese instruments now usually are tuned in equal temperament.

I would like my understanding of music theory to have a 'first class' understanding of Chinese compositions like Horse Racing (and also to have a larger reference pool lmao). I'm going to be starting formal erhu lessons next month, with a curriculum mostly focused on Chinese music. If I have interesting things to report back I'll be sure to share them!

Anyway, in a similar spirit, this post we're gonna try and do a brief survey of various musical constructs relevant to e.g. Japanese music, Klezmer, Blues, Indian classical music... I have to emphasise I am not an expert in any of these systems, so I can't promise to have the most elegant form of presentation for them, just the handles I've been able to get. I will be using Western music theory terms quite a bit still, to try and draw out the parallels and connections. But I hope it's going to be interesting all the same.

Let's start with... pentatonic scales!

Pentatonic scales

In the previous post we focused most of our attention on the diatonic scale. Confusingly, a "diatonic" scale is actually a type of heptatonic scale, meaning there are 7 notes inside an octave. As we've seen, the diatonic scale is constructed on top of the 12-semitone system.

Strictly defined, a 'diatonic' scale has five intervals of two semitones and two intervals of one semitone, and the one-semitone intervals are spread out as much as possible. So 'diatonic scales' includes the major scale and all its cyclic permutations (aka 'modes'), including the natural minor scale, but not the other two minor scales we talked about last time!

However, whoever said we should pick exactly 7 notes in the octave? That's rather arbitrary, isn't it?

After all, in illustration, a more restricted palette can often lead to a much more visually striking image. The same is perhaps even more true in music!

A pentatonic scale is, as the name suggests, a scale which has five notes in an octave. Due to all that stuff we discussed with small-number ratios, the pentatonic scales we are about to discuss can generally be mapped quite easily onto the 12-tone system. There's some reason for this - 12TET is designed to closely approximate the appealing small-number frequency ratios, so if another system uses the same frequency ratios, we can probably find a subset of 12TET that's a good match.

Of course, fitting 12TET doesn't mean it matches the diatonic scale, necessarily. Still, once you're on the 12 tone system, there's enough diatonic scales out there that you can often define a pentatonic scale in terms of a delta relative to one of the diatonic scale modes. Like, 'shift this degree down, delete that degree'.

Final caveat: I'm not sure if it's strictly correct to use equal temperament in all these examples, but all the sources I find define these scales using Western music notation, so we'll have to go with that.

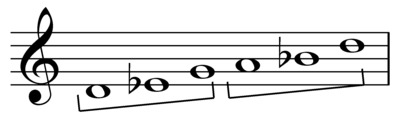

Sakura, sakura and the yonanuki scale

Let's start with Japanese music. Here's the Edo-period folk song Sakura, Sakura, which is one of the most iconic pieces of Japanese music¸ especially abroad:

youtube

This uses the in scale, also known as the sakura pentatonic scale, one of a few widely used pentatonic scales in Japanese folk music, along with the yo scale, insen scale and iwato scale... according to English-language sources.

Finding the actual Japanese was a bit difficult - so far as I can tell the Japanese wiki page for Sakura, Sakura never mentions the scale named after it! - but eventually I found a page for pentatonic scales, or 五音音階 goon onkai. So we can finally determine the kanji for this scale is 陰音階 in onkai or 陰旋法 in senpou. [Amusingly, the JP wiki article on pentatonic scales actually leads with... Scottish folk songs and gamelan before it goes into Japanese music.]

However, perhaps more pertinent is this page: ヨナ抜き音階 which introduces the terms yonanuki onkai and ニロ抜き音階 nironuki onkai. This can be glossed as 'leave out the fourth (yo) and seventh (na) scale' and 'leave out the second (ni) and sixth (ro) scale', describing two procedures to construct pentatonic scales from a diatonic scale.

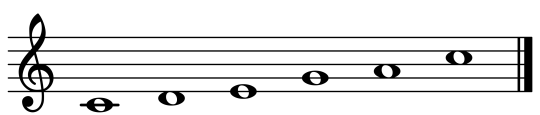

Let's recap major and minor. Last time we defined them using semitone intervals from a root note (the one in brackets is the next octave):

position: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, (8)

major: 0, 2, 4, 5, 7, 9, 11, (12)

minor: 0, 2, 3, 5, 7, 8, 10, (12)

From here we can construct some pentatonic scales. Firstly, here are your yonanuki scales - the ones that delete the fourth and seventh:

major: 0, 2, 4, 7, 9, (12)

minor: 0, 2, 3, 7, 8, (12)

Starting on C for the major and A for the minor (the ones with the blank key signature), this is how you notate that in Western sheet music. As you can see, we have just deleted a couple of steps.

The first one is the 'standard' major pentatonic scale in Western music theory; it's also called the ryo scale in traditional Japanese music (呂旋法 ryosenpou). The second one is a mode (cyclic permutation) of a scale called 都節音階 miyakobushi, which is apparently equivalent to the in scale.

In terms of gaps between successive notes, these go:

major: 2, 2, 3, 2, 3 - very even

minor: 2, 1, 4, 1, 4 - whoah, huge intervals!

The miyakobushi scale, for comparison, goes...

miyakobushi (absolute): 0, 1, 5, 7, 8, (12)

miyakobushi (deltas): 1, 4, 2, 1, 4

JP wikipedia lists two different versions of the 陰旋法 (in scale), for ascending and descending. Starting on C, one goes C, D, Eb, G, A; the other goes C, D, Eb, G, Ab. Let's convert that into my preferred semitone interval notation:

in scale (absolute, asc): 0, 2, 3, 7, 9, (12)

in scale (relative, asc): 2, 1, 4, 2, 3

in scale (absolute, desc): 0, 2, 3, 7, 8, (12)

in scale (relative, desc): 2, 1, 4, 1, 4

So we see that the 'descending form' of the in scale matches the minor yonanuki scale, and it's a mode (cyclic permutation) of the miyakobushi scale.

We've talked a great deal about the names and construction of the different type of scales, but beyond the vague gesture to the standard associations of 'major upbeat, minor sad/mysterious' I don't think we've really looked at how a scale actually affects a piece of music.

So let's have a look at the semitone intervals in Sakura, Sakura in absolute terms from to the first note...

sakura, sakura, ya yoi no so ra-a wa

0, 0, 2; 0, 0, 2; 0, 2, 3, 2, 0, 2-0, -4

and in relative terms between successive notes:

sa ku ra, sa ku ra, ya yo i no so ra-a wa

0, 0, +2; -2, 0, +2; -2, +2, +1, -1, -2, +2, -2, -4

If you listen to Sakura, Sakura, pay attention to the end of the first line - that wa suddenly drops down a huge distance (a major second - for some reason I miscalculated this and thought it was a tritone) and that's where it feels like damn, OK, this song is really cooking! It catches you by surprise. We can identify these intervals as belonging to the in/yoyanuki minor scale, and even starting on its root note.

Although its subject matter is actually pretty positive (hey, check it out guys, the cherry blossoms are falling!), Sakura, Sakura sounds mournful and mysterious. What makes it sound 'minor'? The first phrase doesn't actually tell you what key we're in, that jump of 2 semitones could happen in major or minor. But the second phrase, introduces the pattern of going up 2, then up 1, from the root note - that's the minor scale pattern. What takes it beyond just 'we're in minor'? That surprise tritone move down. According to the rough working model that 'dissonant notes create tension, consonant notes resolve it', this creates a ton of tension. This analysis is bunk, there isn't a tritone. It's a big jump but it's not that big a jump.

How does it eventually wrap up? The final phrase of Sakura, Sakura goes...

i za ya, i za ya, mi ni yu - u ka nn

0, 0, 2; 0, 0, 2; -5, -4, 2, 0, -4, -5

0, 0, +2; -2, 0, +2; -5, +1, +4, -2, -4, -1

Here's my attempt to try and do a very basic tonal/interval analysis. We start out this phrase with the same notes as the opening bars, but abruptly diverge in bar 3, slowing down at the same time, which provides a hint that things are about to come to a close. The move of -5 down is a perfect fourth; in contrast to the tritone major second we had before, this is considered a very consonant interval. (A perfect fourth down is also equivalent to going up a fifth and then down an octave. So we're 'ending on the fifth'.) We move up a little and down insteps of 4, 2, and 1, which are less dramatic. Then we come back down and end on the fifth. We still have those 4-steps next to 1 steps which is the big flag that says 'whoah we're in the sakura pentatonic scale', but we're bleeding off some of the tension here.

Linguistically, the song also ends on the mora ん, the only mora that is only a consonant (rather than a vowel or consonant-vowel), and that long drawn-out voiced consonant gives a feeling of gradually trailing away. So you could call it a very 'soft' ending.

Is this 'tension + resolution' model how a Japanese music theorist would analyse this song? It seems to be a reasonably effective model when applied to Japanese music by... various music theorist youtubers, but I don't really know! That's something I want to find out more about.

Something raised on the English wiki is the idea that the miyakobushi scale is divided into two groups, spanning a fourth each, which is apparently summarised by someone called Koizumi Fumio in a book written in 1974:

Each group goes up 1 (a semitone or minor second), then 4 (major third), for a total of 5 (perfect fourth). The edges of these little blocks are considered 'nucleus' notes, and they're of special importance.

Can we see this in action if we look at Sakura, Sakura? ...ehhhh. I admit, the way I think of the song is shaped by the way I play it on the zhonghu; I think of the first two two-bar phrases as the 'upper part' and the third phrase as the 'lower part', and neither lines up neatly with these little groups. Still. I suspect Koizumi Fumio, author of Nihon no ongaku, knows a little more about this than I do, so I figure it's worth a mention.

Aside: on absorbing a song

Sakura, Sakura is kinda special to me because it's like the second piece I learned to play on zhonghu (after Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star lmao). I can't play it well, but I am proud that I have learned to play it at least recognisably.

The process of learning to play it involved writing out tabs and trying out different ways of moving my hand. I transcribed Sakura Sakura down to start on F, since that way the open G string of the zhonghu could be the lowest note of the piece, and worked out a tab for it using a tab system I cooked up with my friend. Here's what it looks like. The system counts semitones up from the open string, and it uses an underline to mark the lower string.

(Also, credit where it's due - I would never have made any progress learning about music if not for my friend Maki Yamazaki, a prodigiously multitalented self-taught musician who can play dozens of instruments, and also the person who sold me her old zhonghu for dirt cheap, if you're wondering why a white British girl might be learning such an unusual instrument. You can and should check our her music here! Maki has done more than absolutely anyone to make music comprehensible to me, and a lot of this post is inspired by discussing the previous post with her.)

When you want to make a song playable on an instrument, you have to perform some interpretation. Which fingers should play which notes? When should you move your hand? How do you make sure you hit the right notes? At some point this kind of movement becomes second nature, but I'm at the stage, just like a player encountering a new genre of videogame, where I still don't have the muscle memory or habituation to how things work, and each of these little details has to be worked out one by one. But this is great, because this process makes me way more intimately familiar with the contours of the song. Trying to analyse the moves it makes like the above even more so.

More Japanese scales

So, to sum up what we've observed, the beautiful minor sounds of Sakura Sakura come from a pentatonic scale which can be constructed by taking the diatonic scale and blasting certain notes into the sea, namely the fourth and the seventh of the scale. But what about the nironuki scale? Well, this time we delete the second and the sixth. So we get, in absolute terms:

major nironuki (abs): 0, 4, 5, 7, 11, (12)

major nironuki (rel): 4, 1, 2, 4, 1

minor nironuki (abs): 0, 3, 5, 7, 10, (12)

minor nironuki (rel): 3, 2, 2, 3, 2

Hold on a minute, doesn't that look rather familiar? The major nironuki scale is a permutation, though not a cyclic permutation, of the minor yonanuki scale. And the minor nironuki scale is a cyclic permutation (mode) of the major one.

Nevertheless, these scales have names and significance of their own. The major one is known as the 琉球音階 ryūkyū onkai or Okinawan scale. The minor one is what Western music would call a 'minor pentatonic scale'. It also mentions a couple of other names for it, like the 民謡音階 minyou onkai (folk scale).

We also have the yō scale, which like the in scale, comes in ascending and descending forms. You want these too? Yeah? Ok, here we go.

yō scale (asc, abs): 0, 2, 5, 7, 10, (12)

yō scale (asc, rel): 2, 3, 2, 3, 2

yō scale (desc, abs): 0, 2, 5, 7, 9, (12)

yō scale (desc, rel): 2, 3, 2, 2, 3

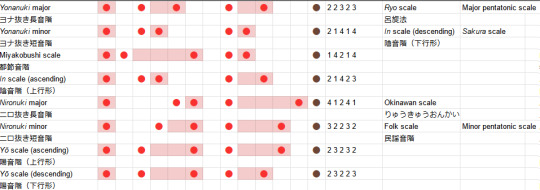

The yō scale is what's called an anhemitonic pentatonic scale, which is just a fancy way of saying it doesn't have semitones. (The in scale in turn is hemitonic). The ascending form is also called the 律戦法 ritsusenpou. Here's the complete table of all the variants I've found so far.

So, in summary: Japanese music uses a lot of pentatonic scales. (In a future post we can hopefully see how that applies in modern Japanese music). These pentatonic scales can be constructed by deleting two notes from the diatonic scales. In general, you land in one of two zones: the anhemitonic side, where all the intervals between successive notes, are 2 and 3, and the hemitonic side, where the intervals are spicier 1s and 4s and a lone 2. From there, you can move between other pentatonic scales by cyclic permutations and reversal.

If you analyse Japanese music from a Western lens, you might well end up interpreting it according to one of the modes of the major scale. In fact, the 8-bit music theory video I posted last time takes this approach. This isn't wrong per se, it's a viable way to getting insight into how the tune works if you want to ask the question 'how does this conjure emotions and how do I get the same effects', but it's worthwhile to know what analytical frame the composers are likely to be using.

Gamelan - when 12TET won't cut it

Gamelan is a form of Indonesian ensemble music. I do not at this time know a ton about it, but here's a performance:

youtube

However, if you're reading my blog then it's likely that if know gamelan from anywhere, it's most likely the soundtrack to Akira composed by Shōji Yamashiro.

youtube

This blends traditional gamelan instrumentation and voices with modern synths to create an incredibly bold and (for most viewers outside Indonesia!) unfamiliar sound to accompany the film's themes of psychic awakening and evolution. It was an inspired choice, adding a lot to an already great film.

'A gamelan' is the ensemble; 'gamelan' is also the style of music. There are many different types of gamelan associated with different occasions - some gamelans are only allowed to form for special ceremonies. Gamelan is also used as a soundtrack in accompaniment to other art forms, such as wayang kulit and wayang wong (respectively, shadow puppetry and dance).

Since gamelan music evidently uses quite a bit of percussion, and so far we've been focused on the type of music played on strings and wind instruments - a brief comment on the limitations of our abstractions. Many types of drums don't fit the 'tonal music' frame we've outlined so far, creating a broad frequency spectrum that's close to an enveloped burst of white noise rather than a sharply peaked fundamental + overtones. There's a ton to study in drumming, and if this series continues you bet I'll try to understand it.

But there are tonal percussion instruments, and a lot of them are to be found in gamelan, particularly in the metalophone family (e.g. the ugal or jegogan). The Western 'xylophone' and 'glockenspiel' also belong to this family. Besides metalophones, you've got bells, steel drums, tuning forks etc. Tuning a percussion instrument is a matter of adjusting the shape of the metal to adjust the resonant frequency of its normal modes. I imagine it's really fiddly.

In any case, the profile of a percussion note is quite different from the continual impulse provided by e.g. a violin bow. You get a big burst across all frequencies and then everything but the resonant mode dies out, leaving the ringing with a much simpler spectrum.

Anyway, let's get on to scales and shit. While I have the Japanese wikipedia page on pentatonic scales open, that it mentions a gamelan scale called pelog (written ᮕᮦᮜᮧᮌ᮪, ꦥꦺꦭꦺꦴꦒ꧀ or ᬧᬾᬮᭀᬕ᭄ in different languages) meaning 'beautiful'. Pelog is not strictly one scale, but a family of tunings which vary across Indonesia. Depending on who you ask, it might in some cases be reasonably close to a 9-tone equal temperament (9TET), which means a number of notes can't be represented in 12TET - you have that 4 12TET semitones would be equivalent to 3 9TET semitones. From this is drawn a heptatonic scale, but not one that can be mapped exactly to any 12TET heptatonic scale. Isn't that fun!

To represent scales that don't exactly fit the tuning of 12TET, there's a logarithmic unit of measure called the 'cent'. Each 12TET semitone contains 100 cents, so in terms of ratios, a cent is the the 1200th root of 2. In this system, a 9TET semitone is 133 cents. Some steps in the pelog heptatonic scale would then be two 9TET semitones, and others one 9TET semitone. However, this system of 'semitones' does not seem to be how gamelan music is actually notated - it's assumed you already have an established pelog tuning and can play within that. So it's a little difficult for me to give you a decent representation of a gamelan scale that isn't approximated by 12TET.

From the 7-tone pelog scale, whatever it happens to be where you live, you can further derive pentatonic scales. These have various names, like the pelog selisir used in the gamelan gong kebyar. I'm not going to itemise them here both because I haven't actually been able to find the basic pelog tunings (at least by their 9TET approximation).

Another scale used in gamelan is called slendro, a five tone scale of 'very roughly' equal intervals. Five is coprime with 12, so there's no straightforward mapping of any part of this scale to the 12-tone system. But more than that, fully even scales are quite rare in the places we've looked so far. (Though apparently within slendro, you can play a note that's deliberately 'out of place', called 'miring'. This transforms the mood from 'light, cheerful and busy' to one appropriate to scenes of 'homesickness, love missing, sadness, death, languishing'.)

The Western musical notation system is plainly unsuited for gamelan, and naturally it has its own system - or rather several systems. In one method, the seven tones of the pelog are numbered 1 through 7, and a subset of those numbers are used to enumerate slendro tuning. You can write it on a grid similar to a musical staff.

But we could wonder with this research - is the attempt to map pélog to 'equal temperament' an external imposition? Presented with a tuning system with seven intervals that are not consistently equal temperament, averaging them to construct an equal temperament hypothesis on that basis, and finally attempting to prove that gamelan players 'prefer' equal temperament... well, they do at least bother to ask, but I'm not entirely convinced that 9TET or 5TET is the right model. Unfortunately, most of the literature I'm able to find on gamelan music theory with a cursory search is by Western researchers.

There's a fairly long history of Western composers taking inspiration from gamelan, notably Debussy and Saty. And of course, modern Indonesian composers such as I Nyoman Windha have also been finding ways to combine gamelan with Western styles. Here's a piece composed by him (unfortunately not a splendid recording):

youtube

Klezmer - layer 'em up

If you've known me for long enough you might remember the time I had a huge Daniel Kahn and the Painted Bird phase. (I still think he's great, I just did that thing where I obsessively listen to one small set of things for a period). And I'd also listen to old revolutionary songs in Yiddish all the time. Because of course I did lmao. Anyway, here's a song that combines both: Kahn's modern arrangement of Arbetlose Marsch in English and Yiddish:

youtube

That's a style of music called klezmer, developed by Ashkenazi Jews in Central/Eastern Europe starting in the late 1500s and 1600s. It's a blend of a whole bunch of different traditions, combining elements from Jewish religious music with other neighbouring folk music traditions and European music at large. When things really kicked off at the end of the 19th century, klezmer musicians were often a part of the Jewish socialist movement (and came up with some real bangers - the Tsar may have been shot by the Bolsheviks but tbh, Daloy Politsey already killed him). But equally there's a reason it sounds insanely danceable: it was very often used for dances.

The rest of the 20th century happened, but klezmer survived all the genocides and there are lots of different modern klezmer bands.

The defining characteristics of klezmer per Wikipedia are... ok, this is quite long...

Klezmer musicians apply the overall style to available specific techniques on each melodic instrument. They incorporate and elaborate the vocal melodies of Jewish religious practice, including khazones, davenen, and paraliturgical song, extending the range of human voice into the musical expression possible on instruments.[21] Among those stylistic elements that are considered typically "Jewish" in Klezmer music are those which are shared with cantorial or Hasidic vocal ornaments, including dreydlekh ("tear in the voice"; plural of dreidel)[22][23] and imitations of sighing or laughing ("laughter through tears").[24] Various Yiddish terms were used for these vocal-like ornaments such as קרעכץ (Krekhts, "groan" or "moan"), קנײטש (kneytsh, "wrinkle" or "fold"), and קװעטש (kvetsh, "pressure" or "stress").[10] Other ornaments such as trills, grace notes, appoggiaturas, glitshn (glissandos), tshoks (a kind of bent notes of cackle-like sound), flageolets (string harmonics),[22][25]pedal notes, mordents, slides and typical Klezmer cadences are also important to the style.[18]

So evidently klezmer will be relevant throughout this series, but for now, since we're trying to flesh out the picture of 'how is tuning formed', let's take a look at the notes.

So it's absolutely possible to fit klezmer into the 12TET system. But we're going to need to crack open a few new scales. Though the Wikipedia editors enumerating this list caution us: "Another problem in listing these terms as simple eight-note (octatonic) scales is that it makes it harder to see how Klezmer melodic structures can work as five-note pentachords, how parts of different modes typically interact, and what the cultural significance of a given mode might be in a traditional Klezmer context."

With that caution in mind, let's at least see what we're given. First of all we have the Freygish or Ahavoh Rabboh scale, one of the most common pieces, good friend of the Western phrygian but with an extra semitone. Then there's Mi Sbererakh or Av HaRachamim which is a mode of it, that's popular around Ukraine. Adonoy Molokh or Adoyshem Molokh is the major scale but you drop the seventh a semitone. Mogen Ovos is the same as the natural minor at least on the interval level.

Which means, without the jargon, here are the semitones (wow wouldn't it be nice if you had tables on here?):

position: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, (8)

freygish: 0, 1, 4, 5, 7, 8, 10, (12)

deltas: 1, 3, 1, 2, 1, 2, 2

mi sberakh: 0, 2, 3, 6, 7, 9, 10, (12)

deltas: 2, 1, 3, 2, 2, 1, 2

adonoy m.: 0, 2, 4, 5, 7, 9, 10, (12)

deltas: 2, 2, 1, 2, 2, 1, 2

mogen o.: 0, 2, 3, 5, 7, 8, 10, (12)

deltas: 2, 1, 2, 2, 1, 2, 2

...that's a big block of numbers to make your eyes glaze over huh. Maybe this 'convert everything to semitone deltas' thing isn't all it's cracked up to be... or maybe what I need to do is actually visualise it somehow? Some kinda big old graph showing all the different scales we've worked out so far and how they relate to each other? ...hold your horses...

[It seems like what I've done is reinvent something called 'musical set theory', incidentally.]

OK, having enumerated these, let's return to the Wikipedian's caution. What is a pentachord? Pretty simple, it's a chord of five notes. Mind you, some people define it as five successive notes of a diatonic scale.

In klezmer, you've got a bunch of different instruments playing at once creating a really dense sound texture. Presumably one of the things you do when you play klezmer is try and get the different instruments in your ensemble to hit the different levels of that pentachord. How does that work? Well, if we consult the sources, we find this scan of a half-handwritten PDF presenting considerably more detail on the modes and how they're played. The scales above are combined with a 'motivic scheme' presenting different patterns that notes tend to follow, and a 'typical cadence'. Moreover, these modes can have 'sub-modes' which tend to follow when the main mode gets established.

To me reading this, I can kind of imagine the process of composing/improvisation within this system almost like a state machine. It's not just that you have a scale, you have a certain state you're in in the music (e.g. main mode or sub-mode), and a set of transitional moves you can potentially make for the next segment. That's probably too rigid a model though. There's also a more specific aspect discussed in the book that a klezmer musician needs to know how to move between their repertoire of klezmer pieces - what pieces can sensibly follow from what.

Ultimately, I don't want to give you a long list of stuff to memorise. (Sure, if you want to play klezmer, you probably need to get familiar with how to use these modes, but that's between you and your klezmer group). Rather I want to make sure we don't have any illusion that the Western church modes are the only correct way to compose music.

Blues - can anyone agree?

Blues is a style of music developed by Black musicians in the American south in the late 1800s, directly or indirectly massively influential on just about every genre to follow, but especially jazz. It's got a very characteristic style defined by among other elements use of 'blue notes' that don't fit the standard diatonic scale. According to various theorists, you can add the blue notes to a scale to construct something called the 'blues scale'. According to certain other theorists, this exercise is futile, and Blues techniques can't be reduced to a scale.

So for the last part of today's whirlwind tour of scales, let's take a brief look at the blues...

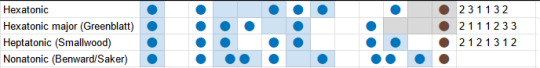

There are a few different blues scales. The most popular definition seems to be a hexatonic scale. We'll start with the minor pentatonic scale, or in Japanese, the minor nironuki scale - which is to say we take the minor diatonic scale and delete positions 2 and 6. That gives:

minor nironuki (abs): 0, 3, 5, 7, 10, (12)

minor nironuki (rel): 3, 2, 2, 3, 2

Now we need to add a new note, the 'flat fifth degree' of the original scale. In other words, 6 semitones above the root - the dreaded tritone!

hexatonic blues (abs): 0, 3, 5, 6, 7, 10, (12)

hexatonic blues (rel): 3, 2, 1, 1, 3, 2

Easy enough right? Listen to that, it does sound kinda blues-y. But hold your horses! Moments after defining this scale, we read...

A major feature of the blues scale is the use of blue notes—notes that are played or sung microtonally, at a slightly higher or lower pitch than standard.[5] However, since blue notes are considered alternative inflections, a blues scale may be considered to not fit the traditional definition of a scale.

So, if you want to play blues, it's not enough to mechanically play a specific scale in 12TET. You also gotta break the palette a little bit.

There's also a 'major blues' heptatonic scale which goes 0, 2, 3, 4, 7, 9, according to one guy called Dan Greenblatt.

But that's not the only attempt to enumerate the 'blues scale'. Other authors will give you slightly longer scales. For example, if you ask Smallwood:

heptatonic blues (abs): 0, 2, 3, 5, 6, 9, 10, (12)

heptatonic blues (rel): 2, 1, 2, 1, 3, 1, 2

which isn't quite a mode of any of those klezmer scales we saw previously, but nearly!

If you ask Benward and Saker, meanwhile, a Blues scale could actually be nonatonic scale, where you add flattened versions of a couple of notes to the major scale.

nonatonic blues (abs): 0, 2, 3/4, 5, 7, 9, 10/11, (12)

There's also an idea that you should play notes in between the semitones, i.e. quarter tones, which would be a freq ratio of the 24th root of 2 if you're keeping score at home.

The upshot of all this is probably that going too far formalise the blues is probably not in the spirit of the blues, but if you want to go in a blues-y direction it will probably mean insert an extra, flattened version of a note to one of your scales. Muck around and see what works, I guess!

Of course, there's a lot more to Blues than just tweaking a scale. For example, 'twelve bar blues' is a specific formalised chord progression that is especially universal in Jazz. What it means for chords to 'progress' is a whole subject, and I think that's the next thing I'll try to understand for post 3. Hopefully we'll be furnished with a slightly broader model of how music works as we go there though.

To wrap up, here's the spreadsheet showing all the 12TET scales encountered so far in this series in a visual way. There's obviously plenty more out there, but this is not ultimately a series about scales. It's all well and good to have a list of what exists, but it's pointless if we don't know how to use it.

Phew

Mind you even with all this, we haven't covered at all some of the most complex systems of tonal music - I've only made the vaguest gesture towards Indian classical music, Chinese music, Jazz... That's way beyond me at the moment. But maybe not forever.

Next up: I'm going to try and finally wrap my head around chords and make sense of what it means for them to 'progress', have 'movement' etc. And maybe render a bit more concrete the vague stuff I said about 'tension' and 'resolution'.

(Also: I definitely know I have friends on here who are very widely knowledgeable about music theory. If I've made any major mistakes, please let me know! At some point I hope to republish this series with nicer formatting on canmom.art, and it would be great to fix the bugs by then!)

#Youtube#music theory#music notes#music#notes#japanese music#gamelan#chinese music#klezmer#blues#i took my new adhd meds and hyperfocused on this all day instead of working ><

121 notes

·

View notes

Text

you know about musical tuning right? harmonics? equal temperament? pythagoras shit? of course you do (big big nerd post coming)

(i really dont know if people follow me for anything in particular but im pretty sure its mostly not this)

most of modern western music is built around the 12-EDO (12 equal divisions of the octave, the 12 tone equal temperament), where we divide the octave in 12 exactly equal steps (this means that there are 12 piano keys per octave). we perceive frequency geometrically and not arithmetically, as in that "steps" correspond to multiplying the frequency by a constant amount and not by adding to the frequency

an octave is a doubling of the frequency, so a step in 12-EDO is a factor of a 12th root of 2. idk the exact reason why we use 12-EDO, but two good reasons why 12 is a good number of steps are that

12 is a nice number of notes: not too small, not too big (its also generally a very nice number in mathematics)

the division in 12 steps makes for fairly good approximations of the harmonics

reason 2 is a bit more complex than reason 1. harmonics are a naturally occurring phenomena where a sound makes sound at the multiples of its base frequency. how loud each harmonic (each multiple) is is pretty much half of what defines the timbre of the sound

we also say the first harmonics sound "good" or "consonant" in comparison to that base frequency or first harmonic. this is kinda what pythagoras discovered when he realized "simple" ratios between frequencies make nice sounds

the history of tuning systems has revolved around these harmonics and trying to find a nice system that is as close to them while also avoiding a bunch of other problems that make it "impossible" to have a "perfect tuning". for the last centuries, we have landed on 12 tone equal temperament, which is now the norm in western music

any EDO system will perfectly include the first and second harmonics, but thats not impressive at all. any harmonic that is not a power of 2 is mathematically impossible to match by EDO systems. this means that NONE of the intervals in our music are "perfect" or "true" (except for the octave). theyre only approximations. and 12 steps make for fairly close approximations of the 3rd harmonic (5ths and 4ths), the 5th harmonic (3rds and 6ths) and some more.

for example, the 5th is at a distance of 7 semitones, so its 12-EDO ratio is 2^(7/12) ~= 1.4983, while a perfect 5th would be at 3/2=1.5 (a third harmonic reduced by one octave to get it in the first octave range), so a 12-EDO fifth sounds pretty "good" to us

using only 12-EDO is limiting ourselves. using only EDO is limiting ourselves. go out of your way, challenge yourself and go listen to play and write some music outside of this norm

but lets look at other EDO systems, or n-EDO systems. how can we measure how nicely they approximate the harmonics? the answer is probably that there is no one right way to do it

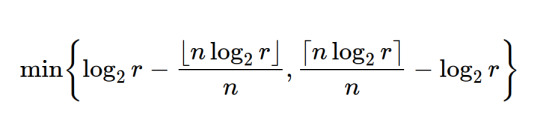

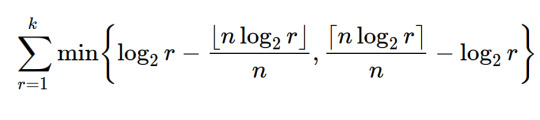

one way we could do it is by looking at the first k harmonics and measuring how far they are to the closest note in n-EDO. one way to measure this distance for the rth harmonic is this:

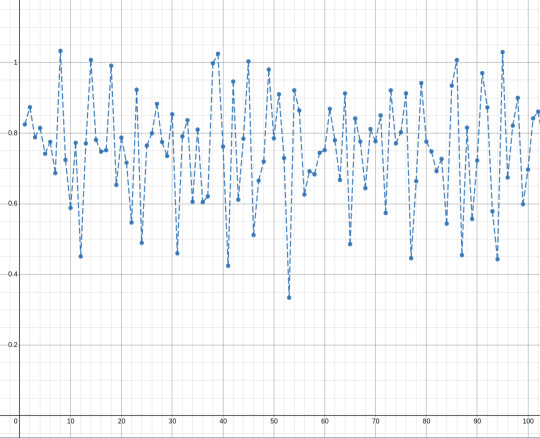

adding up this distance for the first k harmonics we get this sequence of measures:

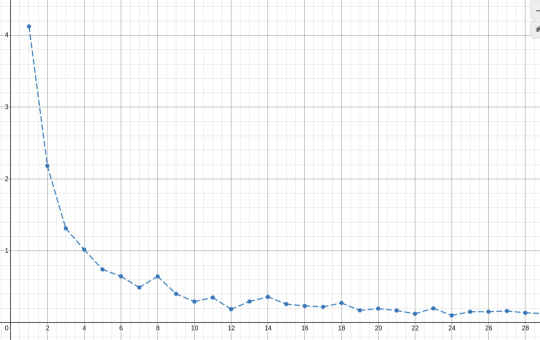

(this desmos graph plots this formula as a function of n for k=20, which seems like a fair amount of harmonics to check)

the smallest this measure, the "best" the n-EDO approximates these k harmonics. we can already see that 12 seems to be a "good" candidate for n since it has that small dip in the graph, while n=8 would be a pretty"bad" one. we can also see that n=7 is a "good" one too. 7-EDO is a relatively commonly used system

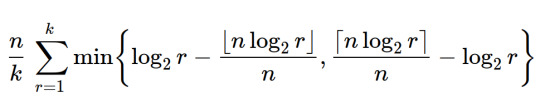

now, we might want to penalize bigger values of n, since a keyboard with 1000 notes per octave would be pretty awful to play, so we can multiply this measure by n. playing around with the value k we see that this measure grows in direct proportion to k, so we could divide by k too to keep things "normalized":

plotting again, we get this

we can see some other "good" candidates are 24, 31, 41 and 53, which are all also relatively commonly used systems (i say relatively because they arent nearly as used as 12-EDO by far)

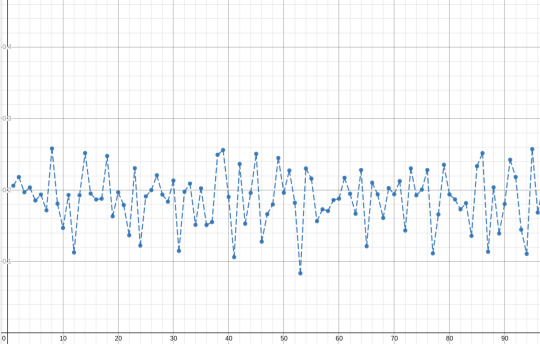

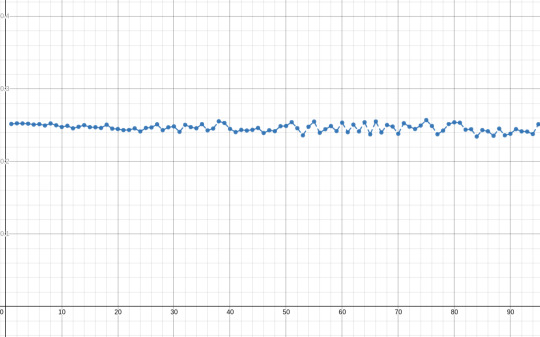

increasing k we notice something pretty interesting

(these are the same plots as before but with k=500 and k=4000)

the graph seems to flatten, and around 0.25 or 1/4. this is kinda to be expected, since this method is, in a very weird way, measuring how far a particular sequence of k values is from the extremes of an interval and taking the average of those distances. turns out that the expected distance that a random value is from the extremes of an interval it is in is 1/4 of the interval's length, so this is not that surprising. still cool tho

this way, we can define a more-or-less normalized measure of the goodness of EDO tuning systems:

(plot of this formula for k=20)

this score s_k(n) will hover around 1 and will give lower scores to the "best" n-EDO systems. we could also use instead 1-s_k(n), which will hover around zero and the best systems will have higher scores

my conclusion: i dont fucking now. this was complete crankery. i was surprised the candidates for n this method finds actually match the reality of EDO systems that are actually used

idk go read a bit about john cage and realize that music is just as subjective as any art should be. go out there and fuck around. "music being a thing to mathematically study to its limits" and "music being a meaningless blob of noise and shit" and everything in between and beyond are perfectly compatible stances. dont be afraid to make bad music cause bad music rules

most importantly, make YOUR music

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alex Savior & Alex Turner

Alexandra Savior in a 2016 interview to NME

“And opening up to a realm where there’s a bar– and there’s nobody in it, it’s dark, and there’s just a dark red light in the corner.”

“And then there’s a woman crooning in a long, black dress”

youtube

"Shades" music video vs "TBHC" music video moment...

- The shabby film... (sorta homemade)... in both videos...

On directing the video for the "SHADES": I recorded it with a camcorder and edited it myself—that's why it's so shitty. [laughs] ... I had no concept. It wasn't like, "Oh, what aspect of this was inspired by the song?" or anything. It was just that my best friend and I wanted to go to Death Valley for free. I was like, "I can write this off on my taxes!" So we went to Goodwill and bought a cheap suit and a wig.

- the red fucking light that she refers to 2016 interview...

- crooning singer? Lounge singer-shimmer?

- “Dress me like the front of a casino, push me down another rabbit hole” Alexandra Saviour - Mirage

- "Handsome dictator of my crimes I can't tell if they're yours, I can't tell if they're mine." Alexandra Savior - Howl

youtube

I honestly don't know what I'm trying to say...

Just need your demons to respond to mine I guess...

- Has he inspired her? Has she inspired him?

- Was she the reason for TBHC's haunted sound?

- Why so many parallels?

- Where does Miles fit in this all? Taylor?

- Is it me or does Alexandra look suspiciously like Louise Verneuil?

Do you know what her stage name was to begin with...? Fucking sitting down? Alexandra Semitone

"I can lift you up another semitone" Arctic Monkeys - 4 stars out of 5

And this is a milex blog... and will stay that way... but do you see the logic in my madness?

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

23 notes

·

View notes