#Russian folktales

Text

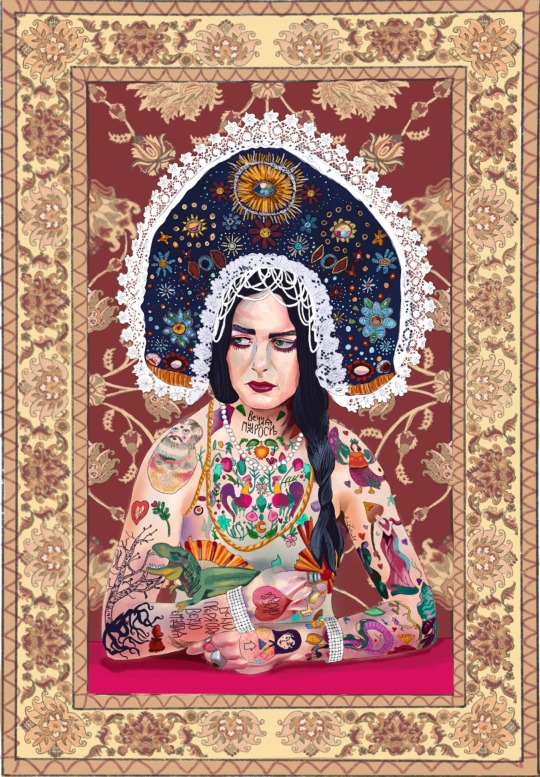

Vasilisa the Wise

If you'd like to support me, you can do so here <3

#digital art#art#original art#animation#slavic folkart#slavic folk art#slavic folklore#slavic#slavic art#russian folklore#russian#russian art#Russian folktales#vasilisa the wise#vasilisa#vasilisa the beautiful

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Yaga journal: Baba Yaga in Soviet movies

And we reach the final article I will translate from the “Yaga journal”: Baba Yaga sur l’écran soviétique (Baba Yaga on the Soviet screen), by Masha Shpolberg!

In 1979, the Soviet studio Soïuzmultfilm produced a three-part cartoon for the Olympic Games that had to happen the following year. The first episode opens with a choir of journalists proclaiming in all the languages of earth: “Micha the bear-cub was just elected Olympic mascot of Moscow”. Baba Yaga listens to this in her cabin, and becomes enraged: “Why him? Why him and not me?”. “Everybody agrees to it!” the journalists say. “And Baba Yaga is against it!” she says, before attacking the television screen with her broom. Throughout these three short episodes, the “Baba Yaga is against it!” cartoon tells the various attempts (and failures) of Baba Yaga and her assistants (Zmeï Gorynytch and Kachtcheï the Immortal) to prevent Micha from reaching the games. The plot relies on the omnipresence of Baba Yaga in the Soviet imagination, and her importance as a symbol of folk-culture. However Baba Yaga did not always have such a status. The witch and her tales were banned by the Soviet Union soon after its creation. Starting in 1918, the year of the creation of the komsomol or “union of Leninist-communist youth”, the Soviet Party reorgaized the educational system: it was decided that fairytales had no place in education. Its rural and pagan roots were problematic for a State which wanted to create an industralized and rationalized world. Galina Kabakova explained that on one side, the fairytale did not carry the values of the new society, and on the other the marvelous and fantastical was considered toxic for the minds of the youth that were to build socialism.

The persecution of the fairytale knew its peak in 1924, when Nadejda Krupskaïa , the companion of Lenine and the president of the Glavpolitprosvet, the Central Comity in charge of Political Education, demanded that all public libraries got rid of the books “with a negative emotional or ideological influence”, as well as the books that “did not conform the new pedagogic approach”. This included the fairytale books of Afanasiev. As the cultural historian Felix J. Oinas explains, in the beginning of the 20s several Soviet critics argued that the folklore was carrying the ideology of the dominant classes, which in turn led the proletarian literary organizations to receive very negatively folktales and fairy tales. A special section of the Proletkult for children even attacked fairy tales based on their “glorification of the tsars and tsarevitchs”, claiming that they were “reinforcing bourgeois ideals” and “causing unhealthy fantasies” in children. When the fairytale re-appeared in the middle of the 30s, it was because the Soviet political culture had decided to re-appropriate the Russian folklore for itself. Just like the Romantic nationalists of the pre-Revolutionnary era, this ideological turn aimed at melting the personal identity in a vaster, collective identity. And what was the best medium to do it? Cinema. Alexander Prokhorov, in his “Brief history of the Soviet cinema for children and teenagers”, explained that the cultural administrators of Staline changed their view on folk-culture, and the fairy tale became a legitimate cinema genre since it helped visualize the spirit of the miraculous reality proclaimed by the Stalinian culture. The end of the NEP, in 1928, also put an end to the importation of foreign movies, freeing the Soviet cinema from all competition - and of all commercial goals.

In 1934, during the first congress of Soviet writers, Samouil Marchak and Maxime Gorki insisted on the importance of childhood literature for the creation of a new Sovietic man, and in 1936 the Sovnarkom, the highest governemental authority, established two new studios out of the ancient Mejrabpomfilm: Soïuzdetfilm, for children movies, and Soïuzmutfilm, for cartoons. It is in this political and institutional context that the young moviemaker Alexandre Ro’ou (in English his name is spelled “Rou”) decided that, for his first film in 1937, he was to adapt a very famous fable, “Wish upon a Pike”. The success of this movie allowed here to adapt a fairytale, more complex on an ideological level: Vassilissa the Beautiful, in 1939. Through this movie he became the “founding father” of the genre of the cinematographic fairytale. It is in this movie that Baba Yaga made her first appearance in cinema, played by a man - Guéorgui Milliar. Throughout the next thirty years, Milliar would play Baba Yaga in three other movies of Ro’ou: in Morozko (1964), in “Fire, Water and Brass Pipes” (1968) and in “The Golden Horns” (1972).

In this article, the author will analyze the evolution of the character of Baba Yaga throughout these four movies - based on the social and political context. While always created by the same movie-maker, and played by the same actor, Baba Yaga is never the same character in these movies. Throughout the years she is slowly “domesticated”: from a macabre and intimidating force of nature, she becomes a vain hag, more superfical than wicked, from a relic of the past, she becomes a modern mascot. By analyzing the narrative and aesthetic choices causing this transformation, the author wants to analyze the allegories of each movie in their historical context.

I) Baba Yaga in the Stalinian era: Vassilissa the Beautiful (1939)

Vassilissa the Beautiful, a movie adaptation of the story “The Princess-Frog”, was conceived as much as an entertainment as a teaching tool. In the version of Ro’ou, Vassilissa is not a princess and Ivanouchka is not an idiot. The two are rather hard-working, intelligent, honest people. The brothers of Ivanouchka oppose the duo by the women their find as wives: an excentric aristocrat, and a gluttonous merchant’s daughter. The entire first part of the movie presents an allegory of the fight of the social classes. The brothers and the wives do nothing while Ivanouchka goes hunting and Vassilissa does the chores, and then they pretend to have done the honest workers job.

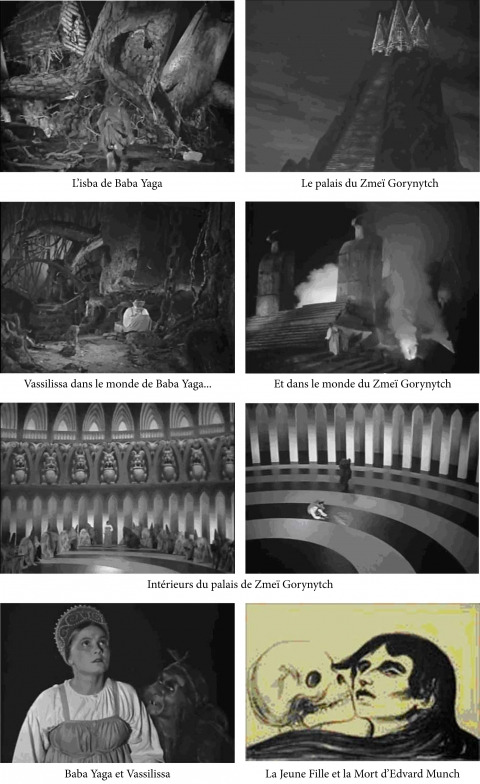

Baba Yaga only appears in the second half of the movie, when the wives burn the frog skin of Vassilissa, and the maiden is ravished by Zmeï Gorynytch. A title-card mentions “In the land of the Zmeï, Vassilissa the very beautiful was guarded by Baba Yaga”. Traditionally, the role of kidnapper in Russian fairytales is played by Kachtcheï the Immortal, who doesn’t appear in the movie - but the Zmeï here fills his role as “the rival of the male hero for the hand of the woman, usually a fiancée or a wife, sometimes his mother” and “the male counterpart of Baba Yaga”. So, as much in their home as in the magical land, Ivanouchka and Vassilissa must fight against oppressors that take away their goods and exploit their work. Jack Zipes noted that, according to the marxist reading of the fairytales, Baba Yaga symbolizes “the entire feodal system, where the greed and brutality of aristocracy are responsible for the hard living conditions. The murder of the witch is the symbol of the hatred felt by the peasants against this aristocracy, that hoards and oppresses.” However, in the Vassilissa movie of Ro’ou, Baba Yaga plays a more ambiguous role. Her skinny and nervous figure, the rags she wears, allows her to hide herself in nature. Her hunched back imitates the rocks, the way she spreads her arms and legs imitated tree branches. By fusing with the landscape, she can attack Ivanouchka without ever being seen by him. Often Ro’ou likes to superposition to allow Baba Yaga to appear and disappear suddenly. As a result she seems half-translucid in many scenes, suggesting that she is a force of nature - or even the personification of the forest.

The “magical” part of the movie plays on the contrast between the domain of Baba Yaga (the forest) and the domain of the Zmeï (the mountain). The two realms are heavily inspired by the expressionist cinema of Germany (especially the sets of the Cabinet of Doctor Caligari, in 1920), but couldn’t be further from each other. The world of the Yaga is the one of the dark forest, confusing and threatening, but deeply organic and human. The world of the Zmeï, however, is an industrialized, hyper-sanitized, geometrical world. A post-human world, or one devoid of humanity: a fascist world. Indeed, the historical context of the movie invites an allegorical reading: the Germano-Sovietic Pact was signed the 23rd of August 1939, and the movie was released the 13th of May 1940, one year before the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union in june 1941. At the time, while Germany wasn’t an official enemy (and it is hard to imagine that Ro’ou selected this tale with a political purpose in mind). But the movie is a proof of the tension that existed at the time about the entire situation. Baba Yaga, who keeps turning and roaming around Vassilissa, reminds of the painting of occidental paintings, “Death near the Maiden”. It isn’t just the virginity of Russia (aka, the integrity of its frontiers) that are threatened - it is her very life that is at play.

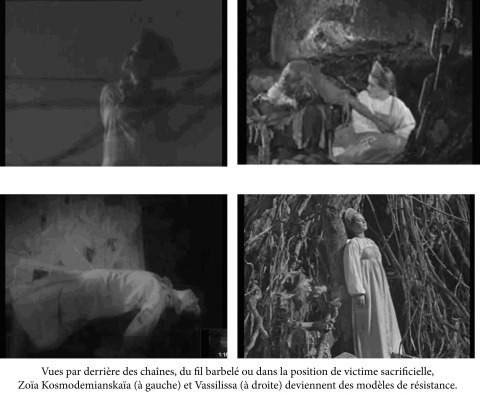

Vassilissa, a girl who is obedient and modest when she is free, becomes proud and rebellious in captivity. She is a model of resistance that anounces the true female heroes of the Second World War in Russia, such as Zoïa Kosmodemianskaïa (made famous by the movie of Leo Arnchtam in 1944). Just like Zoïa, Vassilissa is ready to sacrifice herself for the good of others, and to follow her own principles. When Baba Yaga discovers the hat of Ivanouchka in her isba she aks Vassilissa “Where is he? You say nothing? If you say nothing, I will make you talk. Maybe fire will make you more talkative.” Vassilissa is only saved from torture by the arrival of Zmeï Gorynytch.

The analogy between the monster and the foreign invader is reinforced by the third cinematographic fairytale of Ro’ou, Kachtcheï (Koschei). Filmed in the Altaï and the Tadjikistan in 1944, and released the day of the victory (9th May 1945), the movie tells “how Koschei the Immortal fell onto Russia like a thunder clap in a peaceful sky, burned out houses and our bread, massacred the population and took away thousands of women”. Even if the historical facts cannot allow us to read “Vassilissa” as a simple allegory of the war to come, the images still carry the possibility of an upcoming conflict. We can read it in the presentation of Vassilissa as a resistant-model, as much as in the glorification of the elements of folk-culture (aka, part of Russian culture). The movie is also preceeded by a prologue in which three bards introduce the tale by playing gousli (gusli), a traditional musical instrument. When Ivanouchka goes searching for Vassilissa, the text says “He wandered for a long time throughout his native earth” - even the typography of the title-cards reminds the medieval books. All these elements create throughout this movie a new “nationalist vocabulary”, and so unite a nation threatened by an external force. As Prokhorov explains, “The movies of Ro’ou, just like the kolkhoz musical comedies of Ivan Pyr’ev, were answered an official demand of art inspired by the narodnost (popular spirit/folk spirit)”, an art that “allowed the entire Soviet community to stay in touch with their popular spirit, as the metaphysical source of the communal strength”. The internationalism of the first years of the Soviet Union was slowly breaking down in front of this romantic and deeply essentialist view of the nation.

II) Baba Yaga throughout the Thaw: Morozko (1964), Fire, Water and Brass Pipes (1968) and The Golden Horns (1972)

The period that followed the war was once again difficult for the fairytales, and all those that studied folk-culture. Félix Oinas explains: “After the war, the Russian folklorists knew another series of trials, perhaps the most difficult of them all. The era of the ideological dictatorship of Jdanov, nicknamed Jdanovchtchina, started in 1946, and quickly became an anti-West witch hunt”. Vladimir Propp had just published “The historical roots of the fairy tale”, which was heavily criticize due to containing numerous quotes of Western folklorists, as well as comparativist ideas, not to say cosmopolite ones. In 1947, Soïzudetfilm was re-organized and became the Gorki studo: the studio however did not have any order or demand for children movie. In 1952, the situation led Constantin Simonov and Fedor Parfenov to publish an open letter in the Literaturnaïa gazeta “Let’s resurrect the cinematography for children”. However it was only in 1957, after the death of Staline and the succession of Khrouchtchev, that the minister of culture finally commissioned an augmentation of children movie production. In 1961, the Gork studio was named “Gorki central Studio of cinema for children and the youth”.

When Ro’ou produced Morozko, in 1964, it was in conditions very different and yet paradoxically very similar to the ones in which Vassilissa the Beautiful was produced. The first novelty was the use of color: the second half of the movie takes place in winter, which forces a restrained color palette, even in the makeup and costumes - it is limited to the red and pale blue of the traditional Russian paintings. The appearance of color makes the Baba Yaga younger, as well as more visible in the landscape - but it doesn’t make her more lively. When Ivan discovers the isba in the middle of the forest, and when said isba obeys his order for it to turn towards him, he is sincerely surprised. Baba Yaga gets out of the house yawning, and she asks grumpily “What do you want? Why, unexpected, uncalled, did you dare turn the cabin and wake up the crone?”. It is almost as if everyone in the story was forced in their part of the story against their will. If the Yaga of Vassilissa was jumping from tree-top to tree-top, but the Yaga of Morozko keeps complaining about back problems and she asks Ivanouchka to leave her alone. She only does magic because Ivanouchka forces her to, and her speech is filled with affective diminutives ending in -tchik. Ivanouchka, in the end, doesn’t need to vanquish Baba Yaga, he rather has to convince her to help.

The male equivalent of Baba Yaga, Morozko (Grandfather Forest / General Winter) turns out to be just as harmless as the witch. When he sees Nasten’ka, abandoned by her family to die of cold in the forest, he immediately comes to her help. The role of the two magical characters (Morozko and Baba Yaga) in the life of the young protagonists is limited to the one of a godfather or godmother. The equivalence of these two relationships is highlighted by a sequence which puts in parallel Morozko putting warm clothes on Nasten’ka and Baba Yaga doing the same for Ivanouchka. Another parallel can be found in the way the protagonists call their helpers: Ivanouchka calls Baba Yaga “Yagusia” or “Babulia-yagulia”, while Nastenka calls with affection Morozko “Morozouchka-batiouchka”. From villains, Morozko and Baba Yaga are transformed into helpers, the Donors of the Vladimir Propp’s functions.

The most important consequence of this transformation is the new nature of the “source of Evil”. Evil doesn’t come anymore from what is supernatural, but it rather comes from what is too natural: the flaws of ordinary humans. It is the jealousy of Nasten’ka stepmother and the boasting of Ivanouchka that cause their initial separation and the unbalance that Baba Yaga and Morozko try to remedy to. The qualities preached by Morozko are very close to the ones glorified by “Vassilissa the Beautiful”: hard-work, modesty, and intelligence. What is different is the goal of these virtues: the seriousness and gravity of “Vassilissa the Beautiful” is gone. In Morozko the characters are funny and light-hearted. Ro’ou was trying in “Vassilissa” to animate the visual popular culture, inherited from the lubok and illustrated movies. But in Morozko it all becomes a great show, a smooth surface without any depth. When Ivanouchka leaves his birth-house to go seek his fortune, he passes by a group of young girls that dance and sing when seeing him - these are traditional dances and songs, but the aesthetic is much closer to the one of a technicolor musical than a medieval fantasy.

“Fire, Water and Brass Pipes”, filmed by Ro’ou four years later, in 1968, goes even further in the idea of a show or entertainment. Caracterized by saturated colors and random explosions of music and dance, the movie is aiming at the audiovisual variety show at the cost of the stylistic coherence. This excess alos manifests at the narrative level: while Morozko reunited two distinct fairy tales (Morozko and Ivan-with-the-bear-head), “Fire, Water and Brass Pipes” is a sort of remix of elements taken from numerous myths, cultures and legends (not even all Russian!). The skeleton of the plot is roughly the same: as usual, Kachtcheï kidnaps the beloved of Ivanouchka, and he must undergo a series of trials to get her back. These trials, symbolized by the fire, water and brass pipes of the title, are so many occasions to introduce very different elements, ranging from Greek philosophers to the god Neptune.

In this movie, Ro’ou also modifies the traditional structure of his cinematic fairytales in another way: instead of beginning by the human drama which starts the plot, he begins by the presentation of the magical beings. It is in this “prologue” that we have a full humanization of Baba Yaga: she becomes a mother, and is shown to be able to feel empathy and sorrow. The movie opens with Baba Yaga flying through the sky, rushing to the wedding of her daughter with Koschei the Immortal (also played by Milliar). When she arrives, she is humiliated twice. First, she fails to land properly, implying she can’t move as she used to. Then, nobody recognizes her at the court except for her own daughter and Koschei. This is quite revealing that in this context she introduces herself not as Baba Yaga, but as a relative of the happy couple: she joyfully says (rhyming in Russian), “I am the mother of the bride, Koschei the Immortal is my son-in-law”. This image of Baba Yaga as a mother is not taken out of nowhere: already in the story of Afanassiev called “Baba Yaga and Small-One”, the witch had forty-and-one daughters, that died by her hand. In the movie of Ro’ou, a new importance is given to her maternity as well as to her physical problems (she handles her mortar badly, she falls every time she tries to dance): it all indicates that maybe the life of a witch can be affected by the flow of time. This Baba Yaga is implied to have always been as she is now: she lived a period of youth, and now she is aging. So her life can have a beginning... and an end, like the life of all mortals.

The prologue that presents the maternity of Baba Yaga also has a role in the narrative of the movie: it explains why the Yaga is so willingly helping Vasia (the new name of Ivanouchka). Indeed, when Zmeï Gorynytch offers Koschei a magical apple that makes him young again, he sends away his bride, deeming her too old for him, causing a public humiliation. By helping Vasia defeating Koschei and freeing his beloved (Alionouchka), Baba Yaga is actually avenging her own daughter. She needs Vasia as much as Vasia needs her.

The Golden Horns, made in 1972, thirty-tree years after Vassilissa the Beautiful, was the last movie of Ro’ou that uses the character of the Baba Yaga. After being reduced to a second role in Morozko and “Fire, Water and Brass Pipes”, she finally regains a prominent role. Queen of the forest, she has no rival except for the deer with golden horns - as she complains to a group of hunter, the deer keeps undoing all of her traps and ruining her projects. She doesn’t have back problems anymore, and she is healthy enough to dance and sing. Indeed, throughout the movie she keeps insisting that she is still young. In the beginning of the story she is playing cards with a friend, Duraleï. When he accuses her of cheating and calls her “old hag”, she throws him away from the isba and she says to herself “He dares to call me hag, me, who everybody says has a young soul!”. The Baba Yaga of The Golden Horns isn’t wicked, but she is vain - she is a pretentious old woman that spends hours in front of her mirror. The three young lechïï that serve her constantly flirt with her, and calls her by the diminutive “Babou-yagusen’ka”, and the witch herself flirts with a group of hunter-robbers. Baba Yaga even has a musical number, a song throughout which she turns her hand-mirror into a guitar and sings “I can’t see her enough, Yaga the Fair / Oh my love, me, me me!”.

Beyond the changes brought to the very image of Baba Yaga, Golden Horns is different from the previous movies in two main aspects. The first: the question of the relationship between genders. In Golden Horns, it isn’t a young man who tries to save his beloved from the hands of Baba Yaga or Kachtcheï. It is rather a mother, Evdokia, who tries to save her children. The final conflict is one between two women: one a mother, the other (the Yaga) an old maid. As a result the values of the more are much more conservative in nature. The song of the young girls in the prologue, with the title-cards, compare Russia to a mother. “Always happy, and a bit sad / So is Russia, my mother. / Like the fairytale, intemporal and kind / So is Russia, my mother”. It is this same Russian earth that protects Evdokia in the final battle against Baba Yaga. As the Yaga takes weapons, Evdokia remembers a small bag of soil her neighbor gave her. “Native earth, protect me!” she screams as she throws the soil towards Baba Yaga. These two sequences insist on the sacred nature of the Russian land, “mother” of the people and symbol of maternity itself. The movie implies that it is Evdokia’s maternity that makes her invincible, and that it is the vanity (the “wrong use of her gender”) that dooms Baba Yaga. The absence of a father figure also helps the manifestation of more conservative political messages. It is possible to read Evdokia as a feminist figure: she is independant, and she goes searching for her two daughters without fear. She is intelligent and strong: she isn’t even shocked when she learns she must battle Baba Yaga in a sword-fight. However, she is continuously guided and helped by masculine figure in positions of authority: the Sun, the Wind, and Golden Horns. Golden Horns also offers the perfect example of a theory brought by Evgueni Margolit and summarized by Prokhorov: “Soviet cinema expressed the ideal community of the future as a land of children, where the government filled the role of the strong, order-giving father of the people”. Evdokia, the figure of the mother, is thus treated like a child by the figures of the Father.

In conclusion, this movie offers a new definition of the political action. Like in most fairytales, the movie starts with a transgression: the twin girls of Evdokia, Machen’ka and Dachen’ka, disobey their mother’s instructions and go too far in the forest. What they cannot know is that two wicked spirits trap them, and use them to start a revolution against the Baba Yaga’s tyranny. The movie ends with a tribunal, formed by the small children-wood spirits, alongside the former friend of Baba Yaga, Duraleï. Through a vote, they decide to punish Baba Yaga by banishing her to the swamp. The events of this tale must thus be understood in a wider context, that is seen at the beginning of the movie: this movie represents a shift of powers in the forest, and is the triumph of the humble people, of the simple folks against the monarchy.

Conclusion

In “Vassilissa the Beautiful” (1939), made before the movie, Ro’ou tries for the first time to give a cinematographic shape to the world of the folktales. Taking inspiration from the iconography of the lubok, of the illustrated book, and of the German expressionism, he creates a ciaroscuro universe filled with heavily connotated characters, all either wholly good or wholly evil. Baba Yaga, in this universe, like in the one of fairytales, according to the interpretation of Propp, is a liminal character, the guardian of the frontier between the known and the unknown. Often camouflaging herself in the forest and the rocks that surround the isba, she embodies the dark side of the nature. In a movie whose goal is to enrich the nationalist vocabulary of a land threatened by an external force, Baba Yaga becomes a problematic figure, at the same meant to be “one of us”, since she is part of the Slavic folklore, but also “one of them” since she is unpredictable and hostile.

In the three movies realized by Ro’ou one after the other during the period known as the “Thaw”, the Baba Yaga of Vassilissa is domesticated, becomes a satire, her fangs are removed to make people laugh. While these movies keep feeding from the imagery of Russian nationalism, and keep trying to maintain the authority of the State, they are aimed at being more of an entertainment than a mystical communion with the soul of the people. By giving to Baba Yaga a biography - children, love interests, a passion for clothes and other fashions - these movies remove her from the mythological world, and give her a place in the contemporary world. It is how she becomes, at the time of the Olympic games of 1980, a cult figure, a legitimate rival to Micha the bear-cub for the title of Soviet mascot.

#the yaga journal#baba yaga#russian fairytales#alexander rou#soviet movies#fairytale movies#censorship of fairytales#literary censorship#banning of fairytales#russian folktales#vasilisa the beautiful#the golden horns#morozko#fire water and brass pipes#georgy millyar#baba-yaga

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

oh Baba Yaga, we’re really in it now

#can you tell I have a slavic folklore midterm in an hour#I love this class but this is supposed to be the hardest test#mythology tag#russian folktales#eastern european folklore

1 note

·

View note

Text

Gothic Fantasy/Folk Horror Books: 10 Recommendations

Uprooted by Naomi Novik

Spinning Silver by Naomi Novik

Juniper & Thorn by Ava Reid

The Wolf and the Woodsman by Ava Reid

A Far Wilder Magic by Allison Saft

Down Comes the Night by Allison Saft

Not Good For Maidens by Tori Bovalino

The Bear and the Nightingale by Katherine Arden

Nettle & Bone by T. Kingfisher

The Gathering Dark: An Anthology of Folk Horror by Tori Bovalino and others

#juniper & thorn#the wolf and the woodsman#naomi novik#ava reid#t kingfisher#tori bovalino#gothic fantasy#folk horror#folktales#dark fairytale#fairytale retelling#eastern european#folklore#russian folklore#the bear and the nightingale#books#books and literature#book blog#ya books#book recs#book recommendations#bookish#booksbooksbooks#the brothers grimm#gothic books#dark fantasy#cozy fantasy#cozy books#polish folklore#jewish folklore

570 notes

·

View notes

Text

May Night, or the Drowned Maiden, Aleksandr Rou, 1952

#Aleksandr Rou#1952#May Night#May Night or the Drowned Maiden#1950s#Russian Cinema#Soviet Cinema#Folktale#Moon#Tree#Water#Water Lily

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

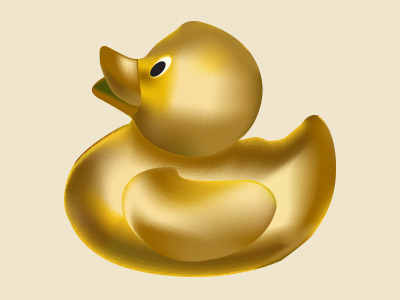

The Duck with the Golden Eggs

Here's an interesting take on the Golden Goose. This is a Russian Folktale about a poor man who finds a duck who lays golden eggs. He gets himself and his family out of poverty with these daily eggs. However, it's discovered that whomever eats the duck becomes Tsar (King). Russian and Slavic Folk tales have a reputation of being very brutal, but this is a very tame one.

Ducks in Magic tend to have connections to emotions as these birds are well known to swim, thus connecting them to the water element. Serving duck related items promotes Emotional Clarity, Emotional Comfort, and Emotional Exploration. It also promotes Affection, Communication, and Opportunities.

Once upon a time there lived an old man named Abrosim, with his old wife Fetinia: they were in great poverty and want, and had a son named Ivanushka, who was fifteen years of age. One day the old man Abrosim brought home a crust of bread for his wife and son to eat; but hardly had he begun to cut the bread than Krutchina (Sorrow) sprang from behind the stove, snatched the crust out of his hands and ran back. At this the old man bowed low to Krutchina, and begged her to give him back the bread as he and his wife had nothing to eat. Old Krutchina answered: “I will not give you back the bread; but I will give you instead a duck, which lays a golden egg every day.”

“Well and good,” said Abrosim; “at all events I shall go to bed without a supper to-night; only do not deceive me, and tell me where I shall find the duck.”

“Early in the morning, as soon as you are up,” replied Krutchina, “go into the town and there you will see a duck in a pond; catch it and bring it home with you.” When Abrosim heard this, he laid himself down to sleep.

Next morning the old man rose early, went to the town, and was overjoyed when he really saw a duck in the pond: so he began to call it, and soon caught it, took it home with him, and gave it to Fetinia. The old wife handled the duck and said she was going to lay an egg. They were now both in great delight, and, putting the duck in a bowl, they covered it with a sieve. After waiting an hour, they peeped gently under the sieve and saw to their joy that the duck had laid a golden egg. Then they let her run about a little on the floor; and the old man took the egg to town to sell it; and he sold the egg for a hundred roubles, took the money, went to market, bought all kinds of vegetables, and returned home.

The next day the duck laid another egg, and Abrosim sold this also; and in this way the duck went on, laying a golden egg every day, and the old man in a short time grew very rich. Then he built himself a grand house, and a great number of shops, and bought wares of all sorts, and set up in trade.

Now, Fetinia had struck up a secret friendship with a young shopman, who did not care for the old woman, but persuaded her he did to make her give him money. And one day, when Abrosim was gone out to buy some new wares, the shopman called to gossip with Fetinia, when by chance he espied the duck; and, taking her up, he saw written under her wing in golden letters: “Whoso eats this duck will become a Tsar.” The man said nothing of this to Fetinia, but begged and entreated her for love’s sake to roast the duck. Fetinia told him she could not kill the duck, for all their good luck depended upon her. Still the shopman entreated the old woman only the more urgently to kill and cook the duck; until at length, overcome by his soft words and entreaties, Fetinia consented, killed the duck and popped her into the stove. Then the shopman took his leave, promising soon to come back and Fetinia also went into the town.

Just at this time Ivanushka returned home, and being very hungry, he looked about everywhere for something to eat; when by good luck he espied in the stove the roast duck; so he took her out, ate her to the very bones, and then returned to his work. Presently after, the shopman came in, and calling Fetinia, begged her to take out the roast duck. Fetinia ran to the oven, and when she saw that the duck was no longer there she was in a great fright, and told the shopman that the duck had vanished. Thereat the man was angry with her, and said: “I’ll answer for it you have eaten the duck yourself!” And so saying he left the house in a pet.

At night Abrosim and his son Ivanushka came home, and, looking in vain for the duck, he asked his wife what had become of her. Fetinia replied that she knew nothing of the duck; but Ivanushka said: “My father and benefactor, when I came home to dinner, my mother was not there; so, looking into the oven, and seeing a roast duck, I took it out and ate it up; but, indeed, I know not whether it was our duck or a strange one.”

Then Abrosim flew into a rage with his wife, and beat her till she was half-dead, and hunted his son out of the house.

Little Ivan betook himself to the road, and walked on and on, following the way his eyes led him. And he journeyed for ten days and ten nights, until at length he came to a great city; and as he was entering the gates, he saw a crowd of people assembled, holding a moot; for their Tsar was dead, and they did not know whom to choose to rule over them. Then they agreed that whoever first passed through the city gates should be elected Tsar.

Now just at this time it happened that Little Ivan came through the city gates, whereupon all the people cried with one voice: “Here comes our Tsar!” and the Elders of the people took Ivanushka by the arms, and brought him into the royal apartments, clad him in the Tsar’s robes, seated him on the Tsar’s throne, made their obeisance to him as their sovereign Tsar, and waited to receive his commands. Ivanushka fancied it was all a dream; but when he collected himself, he saw that he was in reality a Tsar. Then he rejoiced with his whole heart, and began to rule over the people, and appointed various officers. Amongst others he chose one named Luga, and calling him, spoke as follows: “My faithful servant and brave knight Luga, render me one service; travel to my native country, go straight to the King, greet him for me, and beg of him to deliver up to me the merchant Abrosim and his wife; if he gives them up, bring them hither; but if he refuses, threaten him that I will lay waste his kingdom with fire and sword, and make him prisoner.”

When the servant Luga arrived at Ivanushka’s native country he went to the Tsar, and asked him to give up Abrosim and Fetinia. The Tsar knew that Abrosim was a rich merchant living in his city, and was not willing to let him go; nevertheless, when he reflected that Ivanushka’s kingdom was a large and powerful one, fearing to offend him, he handed over Abrosim and Fetinia. And Luga received them from the Tsar, and returned with them to his own kingdom. When he brought them before Ivanushka, the Tsar said: “True it is, my father, you drove me from your home; I therefore now receive you into mine: live with me happily, you and my mother, to the end of your days.”

Abrosim and Fetinia were overjoyed that their son had become a great Tsar, and they lived with him many years, and then died. Ivanushka sat upon the throne for thirty years, in health and happiness, and his subjects loved him truly to the last hour of his life.

#Food and Folklore#Russian fairytale#Fairytale#Duck#golden duck#golden egg#Tsar#folktale#Kitchen Witch#Kitchen Witchcraft#pagan#October#Klickwitch#witch#story

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

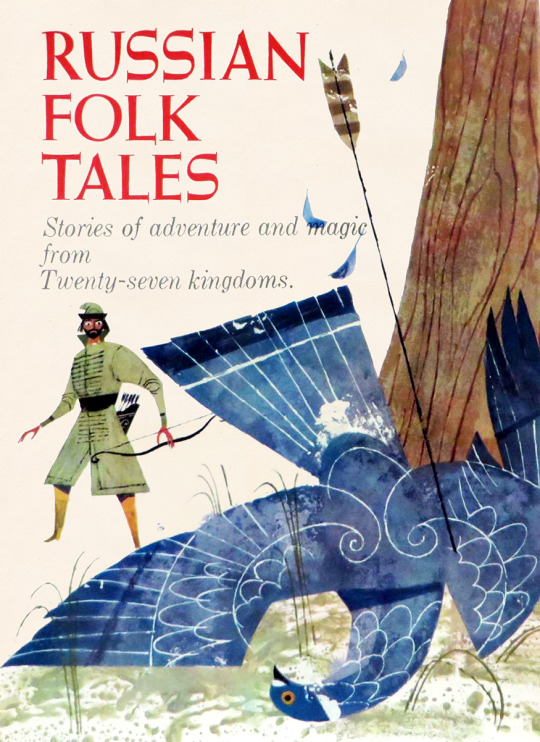

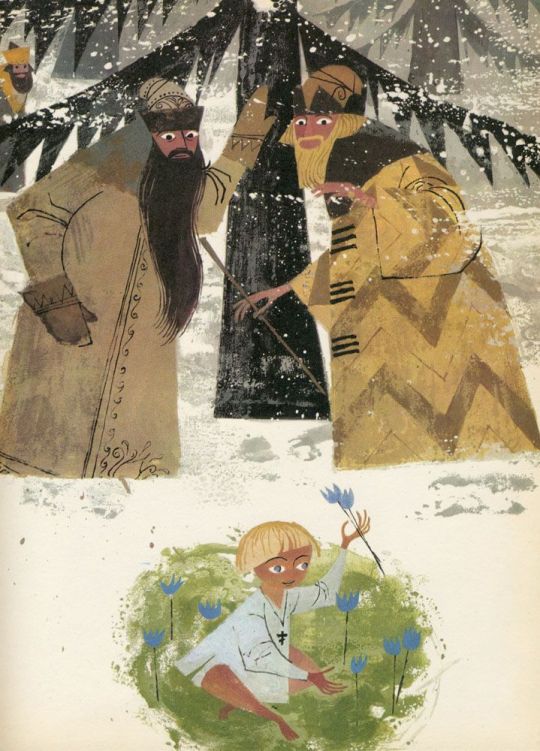

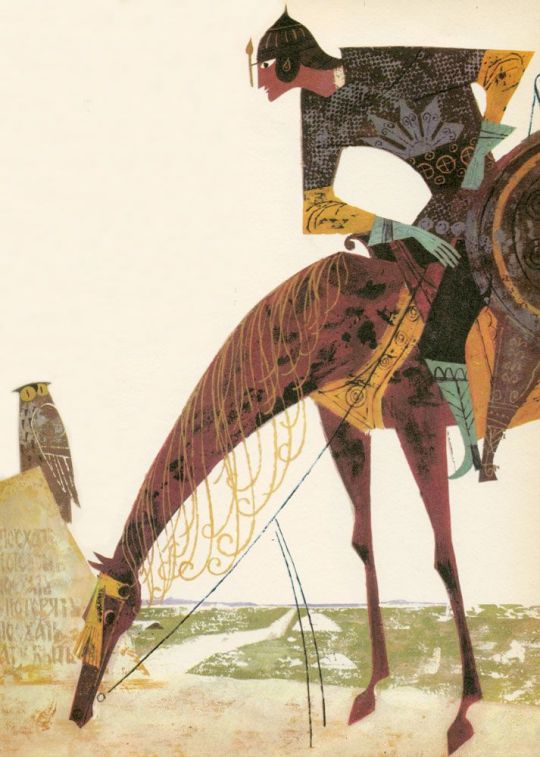

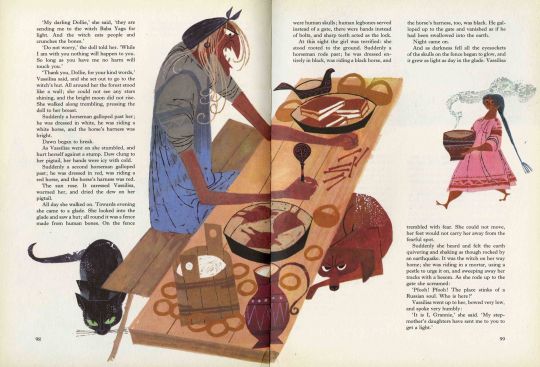

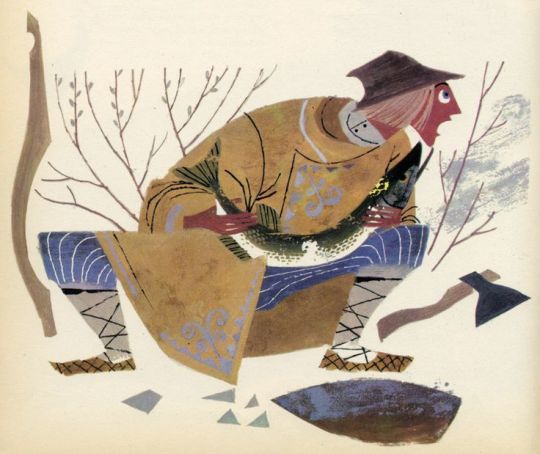

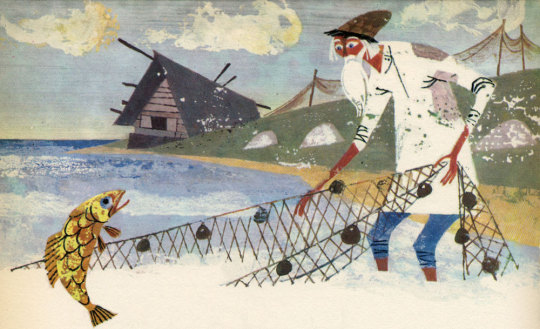

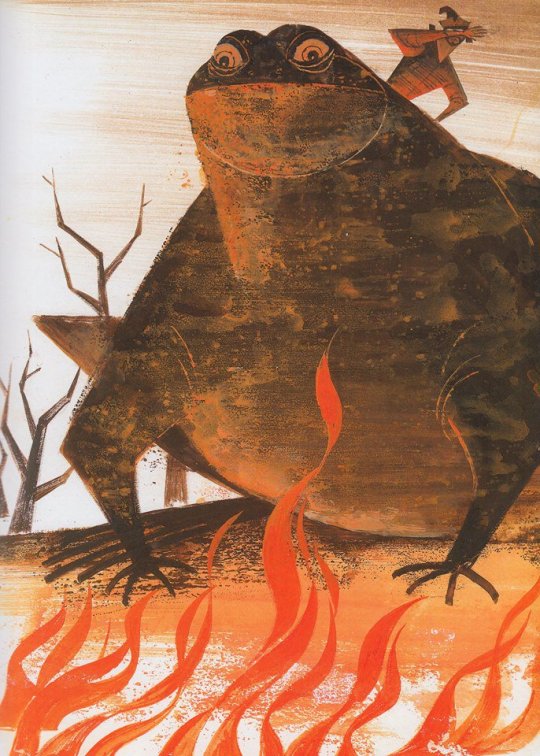

Russian Folk Tales: Stories of Adventure and Magic from Twenty-Seven Kingdoms (1967) by Aleksander Lindeberg (1917-2015)

Born in Russia, Lindeberg was a Finnish illustrator who illustrated several books for children during the 60s and on.

via Ward's Morgue File on twitter

+ a few more illustrations from the Finnish Illustration Society & around the web.

+ an Alphabet book by Lindeberg

#Aleksander Lindeberg#vintage childrens books#vintage illustration#russian folk tales#ward's morgue file#finland#finnish#finnish illustrator#finnish childrens book#folktale#illustrator#illustration#vintage#art

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

MORE INTELIGENT THAN THE KING

@themousefromfantasyland @tamisdava2 @softlytowardthesun @princesssarisa @faintingheroine @professorlehnsherr-almashy @lord-antihero @lioness--hart @thealmightyemprex @greektragedydaddy @natache @adarkrainbow @inevitablemoment @shelleythesapphic @the-gentile-folklorist

(A folktale from Turkestan and Russia)

Pamir was the name of that mountain that was on the border of China, near the beautiful kingdom of Afghanistan. But the name of the king who lived on that mountain no one knows more about who it was. All we know is that he was very fair, brave and generous, and he wisely managed the immense riches of his kingdom. Therefore, all the people strange when one day the royal heralds proclaimed in corners, squares and market of all villages an announcement that seemed incomprehensible:

“His Majesty, our noble and beloved king, orders the following: someone must go to the palace, but he cannot be dressed or undressed, he cannot arrive neither on horseback nor on foot, and he must address the word to the king while neither inside nor outside the palace. If there is one person capable of accomplishing all this, the kingdom will be saved."

After hearing the proclamation, people commented on different types of things. Some thought it must be a bad joke, or that it was a charade, or even, who knows, that the king had gone mad. For some time no one could understand any of those words, until the matter was almost forgotten. One day, the daughter of a peasant who lived in a faraway place in the kingdom learned of that royal order and waited for his father to return home, late at night, sitting on the doorstep.

“My father, tomorrow I must go to the palace. I know what needs to be done to save our people.”

The poor peasant was worried, but the young woman reassured him. In the morning next, he said goodbye and took the road towards the capital of the kingdom. Two days afterwards, the king was in his chambers when he heard a commotion outside and someone called him.

“Lord great king, come out of the palace, I am here to save the kingdom.”

Said a young woman's voice full of firmness. The king descended the stairs and appeared in the main courtyard at the entrance to the palace. He saw a young woman lying on the ground, across the gate, with her legs out and head and arms in.

“Here I am, Your Majesty, and I speak to you neither from within nor from outside the palace.”

The king approached her and noticed that she had a net over her body, so that she was not wearing any clothes but also her body was not naked, since that the net covered him.

“But how did you get here?”

Asked the king.

“I tied a rope around the neck of a mountain goat and left that she led me to the capital. When I got close to the palace I lay down on the ground holding the rope and the goat dragged me here. So I didn't even come on horseback, nor on foot, and therefore fulfilled the demands of its proclamation.”

The king was very pleased and invited the young peasant woman to accompany him to the throne room.

“You must know,” he said, “that there is yet another part of this story that I will tell you yet. A terrible demon appeared in the palace a long time ago. some time and I have no power over him. The devil has tormented me in every way, and at night he sleeps high in a tree in the garden. I spent countless nights without sleep, standing in front of my bedroom window, thinking on how to beat him. I once noticed that he talks in his sleep. I was looking at its monstrous figure squirming among the branches of the tree that serves as its shelter, I heard his words clearly. He said that only a person who was capable of doing certain strange things, the ones I talked about in my proclamation, could save the kingdom from his dominion. He didn't know that I heard him, and when he appeared in the throne room to threaten me one last time, he challenged me with some riddles. In three days he will come back for the answers. If I do not manage to discover them, I will be under his power and he will dominate not only me, but the whole kingdom forever.”

“Well, I came to help. What are the questions?”

said the young woman peasant.

“The first is like this: How many stars are there in the sky?”

The girl smiled and replied:

“There are exactly as many stars in the sky as there are hairs in your demon head. If he doubts, ask him to count each star and, at the same time, pull out the strands of your hair one by one.”

“The second is a very difficult riddle,” said the king, somewhat discouraged.

“Pay attention: the brother is white, the sister is black. Every morning the brother kills the sister. Every evening, the sister kills the brother. And the two never die.”

“Just that?”

Said the young woman.

“It's very easy, this demon is not good at riddles. The brother is the Sun and the sister is the Moon.”

The king was very amazed at the young woman's skill and was already much older. relieved when he told the third challenge, which was a riddle:

“What is greater than God, worse than the devil, that if a living person eats, she dies, and that's what dead people eat?”

"Nothing," the young woman replied without blinking.

“Nothing, how?” asked the king, somewhat confused. He hadn't made it as fast as the young lady.

“Your Majesty, nothing is greater than God, nothing is worse than the devil, if a person eats nothing she dies, and what do dead people eat? Nothing.”

The king laughed as he had not done for a long time, and waited quietly in the sight of the devil. When he heard the king's answers, the demon was enraged. "But you still haven't gotten rid of me," he said in a booming voice.

“I will stay in the palace garden until someone appears who is able to help me. to kill. And that is impossible, because I can only be killed by someone who is neither man or beast, anyone who tries to kill me day or night, give a gift that is not a gift, that is neither fasting nor eating something, and that causes my death with something that is not even metal, iron, rope, fire, water or stone.”

Then he left and went to sleep under the tree in the garden. During sleep he raved, saying incomprehensible things. When the young peasant woman was called by the king and learned of the conversation with the demon, she remained serene as ever. She rolled up her sleeves and asked the king to sleep peacefully that night. The next day, she would go to the garden to find the devil, because she needed to prepare, provide a small detail very simple. In the twilight hour, there she was right under the tree where the demon was.

“Time to wake up,” she yelled, “monster, vampire, genie, demon, whatever you are. You better open your eyes, at least you'll die awake. now is the twilight time, nor day, night; and I am a woman, not a man, not an animal. I also bought this gift for you.”

The young woman extended her closed hands to him and, when he went to take the present, she opened her hands and inside there was a little bird that flew before the demon could grab it.

"But you must be eating, or fasting," said the monster.

“Neither one nor the other,” said the young woman with an amused look.

“I am chewing on a piece of bark.”

The demon gave such a fearful cry that it was heard in the villages of surroundings. In his immense fury he lost his balance and fell from the top of the tree. O The noise was deafening, and the fall was fatal. It wasn't sword, arrow, poison, gallows, fire or water that killed him. He died buried under the weight of his own anger. When the young woman looked away from that misshapen and mangled mountain halfway across the garden, she looked up and saw the king, beaming, standing before her.

“I still need to ask you one last thing,” he said.

“Are you able to Guess what I'm thinking right now?”

“I wish Your Majesty were thinking of asking me to be your queen,” said the young woman, blushing for the first time in front of the king, for the first time with downcast eyes and a trembling voice. The feasts that followed were the greatest the kingdom had ever seen. A commemoration of the demon's death, the marriage of the king to the beautiful and intelligent, occupied the life of those people for many, many days. When the King and Queen finally found themselves alone in their chambers, the young woman took a parchment from a small chest and handed it to her husband.

“I have only one request to make, my lord king. That your majesty signs this document now, where it is written that if one day I am sent away from this palace, I can take with me only one thing that I will choose as the most precious thing to me.”

The king signed the paper without giving the slightest importance to that request, after all the the last thing on his mind at that moment was to part with that young woman. extraordinary. Time passed and the two together ruled that kingdom with great wisdom, being very happy. But the royal advisors had more and more jealousy of the queen, because it was always her word that the king heard first. They began to conspire against her and did so much that they managed to poison the king's heart, telling him a lot of lies about the queen. One day, blinded by mistrust, the king quarreled with his wife and expelled her. from the palace.

“It is well, my lord king,” said the queen, unaffected.

“Tomorrow I will go away, but I wish we could say goodbye tonight and have dinner together.”

The king consented, and during dinner the queen filled his cup with water many times. wine, so that sleep took over him, even before he went to bed. The next day, when the king awoke to sunlight streaming in through the window, he didn't know where he was. That wasn't his bed, it wasn't his walls. room. He ripped off the covers, startled.

“What is this place? How did I get here?”

The door opened and the queen entered.

"Your Majesty remembers that document she signed when we married? For according to the words written there, I could take with me that that I liked best in the palace, in case I was sent away. So last night, I asked some servants to transport him in the royal carriage to my father's house. father, in the middle of the forest, and deposited him here. What I like most about the palace, my greatest treasure, is Your Majesty. That's why I brought you with me to my new abode, and here is the parchment that legitimizes my act.”

When the king and queen returned together to the palace that same day, they arrived embracing inside the carriage, talking about the children they wanted to have and the children their children would have, thinking their story would never be forgotten.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Round 2 Side B: The Russian Ballet

LEFT: Angelina Ballerina from Angelina Ballerina

Description:

"literally one of my favorite characters as a child. i mean a mouse who does ballet!!"

RIGHT: The Mouse from “The Giant Turnip” (Russian folktale)

Description:

This little mouse gave just enough extra strength to finally help the family in the folktale pull the giant turnip out of the ground. Even the smallest of efforts can make a big difference!

#books#angelina ballerina#childrens books#folktales#русский#the giant turnip#russian#mice#mousejoust tournament#mousejoust r2sb#tumblr polls

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

rip to kate bush not knowing what "babooshka" meant when she was 22, in primary school one year, our class (and teacher??) had got bored of doing a nativity play every christmas, so instead we got to do a play (allegedly??) based on a russian folktale abt an old woman who isn't interested in the christmas star bcos she's too busy cleaning her house, that i still get the songs from stuck in my head now 👍

#looking it up it seems like it might have just been something made up by an american to sound like a russian folktale#but it was still a fun change of pace 😆

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ivan Tsarevich Fighting the Dragon

by Victor Vasnetsov

#ivan tsarevich#fighting#dragon#russian#folklore#heroes#tsarevich#russia#folktales#tsar#victor vasnetsov#art#dragons

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

.

#someday I will figure out how to do a vault era fic involving the Russian folktale 'The Death of Koschei the Deathless'#the hero's wife (the awesome warrior princess Marya Morevna) has left him at home while she goes and does some battles#warning him that Koschei the Deathless is shut in the closet and he mustn't let him out#being an idiot the hero does open the door#he feels sorry for Koschei and gives him a drink of water#which restores his powers and he goes zooming off and kidnaps Marya Morevna#and then a lot of fairy tale stuff happens that isn't so relevant#I just think Missy would find that plot beat Extremely Funny

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Yaga journal: Baba Yaga in the lubok

Our next article in the Yaga journal (again, I skip a few which are honestly no fun or not interesting to translate) is “Baba Yaga in the luboks” by Galina Kabakova.

There has been research about Baba Yaga ever since the first publication of Russian fairytales. People kept debating the origins and symbolism of the character: is she tied to an initiation ritual, with death or birth, as Vladimir Propp said? Or is she rather a figure of the earth, or fertility? But all those questions are based on the analysis of folktales and oral fairytales. This article rather proposes to take a look at the folk-iconography of Baba Yaga, to study the way the character was drawn and illustrated to explore new roads and theories about the character - more specifically the article studies the Russian luboks of the 18th and 19th centuries.

I) Baba Yaga and her companions

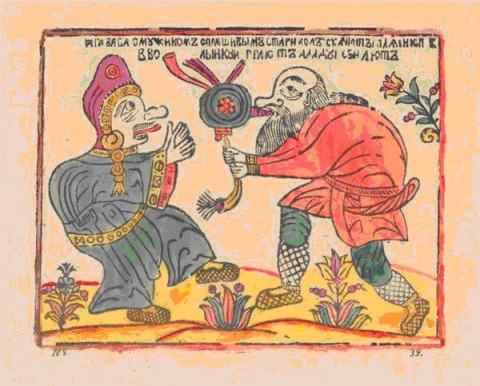

When it comes to studying “popular illustrations”, two drawings keep popping up. One is “Yaga-baba goes to fight the crocodile”. The second is “Yaga Baba with a moujik, an old bald man, they jump while dancing”. Both images date from the 1760s and appear in the catalogue of Dimitri Rovinski.

The first picture appears in two different versions. The first has an inscription saying “Yaga-Baba goes to fight the crocodile, riding a pig, with a pestle in her hand. They have a bottle of wine under the bush.”

The second version has a different inscription: “Baba Yaga wooden-leg goes to fight the karkadil while riding a pig, armed with her pestle. There is wine.”.

These two pictures are fascinating because they depict a character ignored by Russian folklore: the crocodile. The book of Konstantine Bogdanov “Crocodiles in Russia” talks about the place this animal has in the Russian culture, and it insists on its “exotic” connotations. The korkodil or karkodil appears in medieval bestiaries and symbolizes either the devil, either hypocrisy (hence the expression “crocodile tears”). However these bestiaries depict the crocodile as he appears in real life, while the luboks rather paint a much more fantastical creature: it has the mane and legs of a lion, the tail of a wolf, the claws and beard of the devil.

Beyond the two versions of the Yaga with the crocodile, we also have the famous depiction of the Yaga with the Moujik:

This other companion of Baba Yaga, the moujik (note: in French it is “moujik” but in English I guess it is spelled “mujik”, the same way we call “loubok” the thing English spell as “lubok”), with his bagpipe, is dressed like a true peasant, with typical Russian shoes - the lapti. His bald head implies he is old. The Baba Yaga is represented very differently from one image to the next, and two depictions can even contradict each other - but all in all, she usually doesn’t look like the way she is described in fairy tales. The famous “bone leg” does not appear. She looks like a woman, but with exaggerated traits. She has a big, large nose that is curved upward while also being hooked, and in the three pictures above we see her enormous tongue coming out of her mouth. Plus, the dancing Baba Yaga is depicted as a hunchback.

In these engravings, Baba Yaga is dressed like rich Russian women of the 16th and 17th centuries. Her outfit is similar to the letnik, with embroidered sleeves and belts. She wears an earring and a necklace, indicating again a hgher status. Her cap is the one of a married woman (or of a widow) - but she is sometimes depicted with her hair uncovered and untied (such as in the second picture), which was thought to be indecent at the time. The Baba Yaga of the images 2 and 3 wear the lapti, just like the peasant-mujik, which creates a strange incoherence in her outfit, mixing rich and poor elements. In fact, some people point out that, with her cap, she looks like she is wearing a traditional Finnish woman outfit.

Just as interesting are the attributes of the Baba Yagas. The mortar of the broom that she uses in fairytales are absent here, and she rather rides a pig or a boar. In the two first picture, she is seen holding both feminine and masculine items: the comb (feminine) and the axe (masculine). We also see the pestle she holds in her hand. In fact, the pestle used as a weapon in found in other luboks - and it is used by Baba Yaga in fairytales (for example in “Fedor Vodovitch and Ivan Vodovitch”, she hits an old man with her pestle). The pestle is also the weapon of the wicked woman in the lubok - in a book of the 18th century we find a popular image depicting an evil wife chasing her husband out of the house, holding in her hands a pitcher and a pestle.

The strange couple formed by the crocodile and Baba Yaga has other interesting attributes: the bottle of wine near the crocodile, and a little boat that appears on the water. The symbolic landscape is also formed of flowers and branches - to signify a springtime flora. These depictions have been a mystery for the universities since more than a century. If the Baba Yaga of the luboks looks so little like her fairytale self, isn’t it rather an entire other character hiding under the name of the witch?

Dimitri Rovinski was the first to theorize that these images might be a political satire of the first Russian emperor, Peter the Great, and his wife. The boat would symbolize the passion the tsar had for the marine, which led him to build a new sea-side capital (Saint Petersburg). The Finnish outfit of the woman would be a reference to the origins of his second wife, the empress Catherine the First. The wine would denounce their known love for alcohol, and the marital position of the wife would be to evoke their tumultuous relationship. Rovinski suggested that these drawings and engravings were created by “old believers” that had a strong hatred of the imperials as their sworn ennemy, and thus called the emperor names such as “cat” and “crocodile”. Other popular images could be interpreted as a satire against Peter the Great: such as the cat in “Kazan’s cat, or The funeral of the cat by the mice”.

This interpretation was repeated several times by several searchers, and is still used to this day. But it opens quite a few questions. If the crocodile is indeed Peter, what would the beast’s large beard means, since Peter was known to hate and forbid beards? On top of that, the engravings we have come from the 1760s, and we have no proof that the originals were created half a century before. Diane Farrel in “Popular prints in the cultural century of the eighteenth-century Russia”, had doubts about the political context of thos pictures. She suggested that maybe the characters were tied to a carnivalesque world. Konstantin Bogdanov also insisted on a value of “pure entertainment” for those drawings, that are part of a long tradition of comical scenes depicting drunks and brawlers. These three engravings also seem to be part of an anti-feminist theme, to not say misogynistic, depicting women (especially young wives) as always trying to humiliate and abuse their husbands - sometimes this satire was aimed more precisely at foreign women.

II) Searching for the origins of Baba Yaga

When the author of the article prepared an anthology of etiological fairytales (it was published in 2005 as “Contes et légendes de Russie”, “Folktales and legends of Russia”), they found a very short tale recorded in Eastern Russia - in the valley of Kama, a region noticeable by a high percentage of “old-faith believers”. The story goes as such: A devil decided to create Baba Yaga. He gathered the twelve most wicked old women, and he cooked them in his cauldron. He tastes the result, then made them cook a little more. He tasted a second time, and he sneezed so hard all the door flew open. He ate a spoon of the brew, and spit. From the cauldron, Baba Yaga then sprung forth.

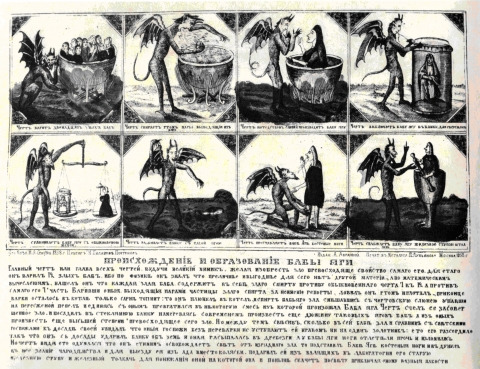

While the text appears in the Index of fairytale-types of Western Slavic tales (under the number SUS 1169), it stays an isolated phenomenon because no other version was recorded in Russia, and it is not present in either Bielorussia or Ukraine. It was after publishing this text that the author of the article discovered a lubok page, made of eight mages, forming a sequence depicting the creation of Baba Yaga. The fairytale quoted above seems to be an abbridged version of the tale depicted by the lubok.

This lubok is quite rare, as it does not appear in the catalogue of folk-images of Dimitri Rovinski. One copy of it is kept at the Museum of religious history in Saint-Petersburgh, another at the National Library of Saint-Petersburgh, and a final at the National Library of France. It is this last copy that was reproduced above, in the monography of Catherine Claudon-Adhémar, “Imagerie populaire russe” (Russian folk-imagery), 1977. Here is the full text of the legend:

Origins and formation of Baba Yaga. The devil in chief, or leader of all devils, while being a great chemist, decided to invent an evil that would be greater than his own power. In this goal, he cooked twelve wicked women, because physics taught him that it was the best and most profitable way. After mathematic calculations, he understood that each wicked woman contains bad alcohol, compared to a regular devil, in the proportion of seven against twelve, and against his own person a seventh. By cooking the particles of the bad alcohol he set them free with the steam, but since he had nothing to contain them, he caught them with his mouth and swallowed them. At the end of the cooking, there was in the cauldron only burned matter ; he spit in the cauldron, and the alcohol mixed with the saliva of the devil fell onto the ashes, and all of this fusing together, created Baba Yaga.The devil considered her to be the ultimate evil, and he placed her in a jar, wanting to create afterward a dozen more Baba Yaga like her, and by cooking them together greating an even more perfect evil. But by weighing the evil that she contained, and comparing it to the evil present in the high-society women, he realized, disappointed, that these ladies, even without cooking, were not outweighed by her. This made him so angry that, out of dejection, he threw the jar onto the ground, and it broke in a thousand pieces, and the legs of Baba Yaga were ripped and broken. This made the devil return to his senses: understanding he was freeing the world of a great evil, he quickly gave to Baba Yaga legs of bones, he taught her wtchcraft, and so she could leave hell he gave her for a drive an old iron mortar that was laying around in his laboratory, and an iron pestle to lead the mortar - and she is still using them to this day to travel the world, doing evil wherever she goes.

This is a clearly satirical text that insists on the “scientifical” aspect of the creation of Baba Yaga, invoking mathematics, chemistry and physics. But it is clear that this lubok was clearly aiming to mock the wickedness of women. Even though for once, upper-class women are more clearly the target. This satire can have roots in a Western model: there is the famous Lustucru series in France where the smith by the same name tries to re-shape women, and he even uses an alchemical still to do so. The motif of creating life reminds the homonculus of the Middle-Ages, while Baba Yaga and the upper-class woman being weighed together reminds the religious icons such as “Saint Michael and Satan weighing the souls of the sinners.”

But there are also several motifs typical of etiological tales, such as saliva being used to create a human figure (usually the divine saliva helps build clay figurines that become the first humans). In the oral tradictions, there are tales that depict the devil as a creator: for example, sometimes he is responsible for creating the different nations. An Ukrainian tale depicts him in this role, and the story is quite similar to the one of the lubok above: the devil puts herbs and pitch in his cauldron, and cooks them. After it cooked enough, he first takes out of it an Ukrainian, then a German, then a Tatar, then a Jew - and the latter is considered by the devil as the most successful of the four. Even if this tale is supposedly etiological, we find back here the permanent trait of the devil: he is a misfortunate creator, he tries to create man but fails, or he tries to imitate the work of God but ends up creating something else entirely. And in the case of those stories, he tries to create something new that could harm much more than he does, and in the end he merely re-creates the already wicked women of the world.

The simplicity of the drawing makes the author think that the one who created this lubok did not copy a Western engraving (unlike other lubok - such as the one of a couple fighting each other to know who is going to wear the pants). The artist is quite clumsy. The devil looks like a man, but with the typical attributes of a Russian devil: a tail, horns and a goat’s beard, rooster claws, but also wings to remember his celestial origin (this last detail is not constant in the depictions of Satan). Is the great similarity in the designs of the devil, the women and Baba Yaga an intended detail? The author rather thinks it is because of the lack of talent of the engraver. It should also be noted that Baba Yaga and the upper-class women are depictedwth a great simplity: no sign of their status, no sign of vanity. The only details that form the portrait of the wicked witch are her two legs (instead of one in the folklore) of bone, and her mortar with its pestle.

Searching for the origins of the mysterious lubok led the author of the article into the world of peddling literature, which had a heavy role in adapting and re-creating folktales. This “lubok literature” existed long before the “scientific” publication of the fairytales in the 19th century. Alexandre Afanassiev used numerous books of lubok of the second half of the 18th century, because he believed they were the closest to the oral folktales. And as such, the author managed to find the text of the lubok in a fairytale called “Tale of the sir Zaolechanine, brave in service of the prince Vladimir” which is part of the “Russian tales” in 10 volumes of Vassili Levchine (published in 1780). This text, unlike the one of the lubok, mentions the term of alchemy “caput mortuum” (mummy-brown), which allows to create the worst of all creatures, Baba Yaga:

Of the origin of Baba Yaga. The devil in chief, or the devil above all other devils, who was a great chemist, cooked twelve evil women, hoping to obtain from them an essence of evil that would outdo him in wickedness. Physics had taught him that it was the best and most profitable material. According to his mathematical operatons, each wicked women contained bad alcohol in a proportion of 7 against 22 (against a regular devil) - against him, it was an 11th, and this is why he cooked twelve. But since the still hadn’t been invented, he caught with his own mouth the alcohol particles that escaped from the steam. At the end of the cooking, was only left in the cauldron “caput mortuum”. The devil spit in the cauldron, the alcohol mixed to the saliva of the devil fell on the caput mortuum and the devil saw something that was beyond all of his expectations, as Baba Yaga appeared out of the cauldron.

In the tale of Levchine, this text is under a drawn portrait hanging on the wall of an enchanted castle, and it ends with a warning: “This tale is told to you, o curious reader, from someone who is protecting your savior. But, as it is agreed that the mystery revealed against the will of a woman must be punished, for your disobediance be transformed into Baba Yaga”. And indeed, when the character tells of his discovery to others, he is turned into a dragon.

III) Baba Yaga in the lubok literature

In the lubok literature, we find back the same motifs as oral tales, but some are modified, and others added. For example the motif of cannibalism: let’s take the fairy tale type ATU 327C, “The devil brings back home a child in a bag”. In the Russian version of the tale, it is always the witch Baba Yaga who captures a child and tries to cook them in her oven. In popular versions of this tale, such as in “Hansel and Gretel” of the brothers Grimm, it is the witch or her daughter or both that end up burned into the fire by the clever child. In lubok literature, things are very different. For example, in “The tale of sir Zaolechanine”, the witch not only successfully captures a six-year old child, but she also manages to roast him and eat him. The assimilation between Baba Yaga and the dragon, who is the antagonist of the hero in the tale, is also quite different from oral tradition. In “The second tale of Ivan Tsarevitch”, from the Russian Fairytales of Piotr Timofeev (1787), the dragon-king Erakski captures Maria Morevna, and then goes to war against Baba Yaga, which allows Ivan Tsarevitch to save Maria whila the dragon is away. Usually, in fairytales, it is the job of the hero to fight and kill the wicked dragon. Simlarly, in the “Tale of Leviane the brave”, from the anonymous book “The Narrator of Russian fairytales” (1787), it isn’t the hero that is asked to keep the fabulous horses of Baba Yaga, unlike in the popular fairytale “The magical horse” (ATU 302C), it is rather Kachtchej the Immortal, another fearsome antagonist, that must take on this job.

In the “Tale of sir Zaolechanine”, we also discover some “romantic” themes invented by the author: Baba Yaga adopts the female protagonist, and she falls in love with the winged dragon, who doesn’t love her back. However she visits him every day, and sometimes goes back to her house in tears, and sometimes in “great anger that always ends up in sigh”. And to end, when Baba Yaga dies, “her petty soul leaves her miserable body and falls into hell”. But it is especially in the descriptions that we find elements absent from oral versions. For example, in “The second tale of Ivan Tsarevitch”, the witch lives in a palace protected by an iron barrier - instead of a hut on top of chicken legs. In an anonymous version of “The fire-bird and the gold-mane horse”, published in Moscow in 1860, we have a description of the witch as having the head of a pig, the tail of the crow or a tail of bones” - or she has “two horns, a dog head, a goose’s nose, a tin tail”. And other times, it is written “the awful Baba Yaga with long teeth, a bone leg, a cast-iron head and a clay tail.” It must be remembered that the folkloric character of Baba Yaga is barely described, and when she is it is another set of traits that is put forward. In folklore it is her traits tied to the world of the dead or the reptile that are brought forward: she only has one leg, and it is a leg of bones (or a bony leg, aka a very skinny one). Her nose is sometimes so long it touches the ceiling. Other times, the traits described are about an hypertrophied feminity: breasts so enormous they cannot be hold in the room and overflow out of the door. Finally, there are also a few mix-and-match details, such as a nose made of iron or a face made of clay.

To conclude this study of iconography and engraving of legends, the author says that the lubok takes the character of the fairytales, this popular character of oral tradition, not to retell its story faithfully, but to mock through it the weaknesses and flaws of women, focalizing especially on upper-class women and foreign women. Folk-imagery is thus very revealing of social, racial and gender prejudices very common at the time.

#the yaga journal#baba yaga#russian folklore#russian folktales#lubok#russian fairytales#antisemitism in fairytales#misogyny in fairytales

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

𝕾𝖎𝖗𝖎𝖓

The Russian Sirins ( All linked to each of my DeviantArt works respectively)

The mountains and forests of Japan have long been the domain of the legendary Tengu, one of the most famous and ubiquitous creatures in Japanese folklore. The Tengu was a shape-shifting bird-like creature of the sky and trees, and they were seen as a protector of the mountains. The spirits Alkonost, Gamayun and Sirin are a mythical Tengu like creature with halve bird bodies in Russian Folktales. Similar to their neighboring Japanese folktales, these winged spirits possess a great deal of power when provoked.

Sirin

Sirin is a mythological creature of Russian legends, with the head and chest of a beautiful woman and the body of a bird (usually an owl). According to myth, the Sirins lived "in Indian lands" near around the Euphrates River.

These half-women half-birds are directly based on the Greek myths and later folklore about sirens. They were usually portrayed wearing a crown or with a nimbus. Sirins sang beautiful songs to the saints, foretelling future joys. For mortals, however, the birds were dangerous. Men who heard them would forget everything on earth, follow them, and ultimately die. People would attempt to save themselves from Sirins by shooting cannons, ringing bells and making other loud noises to scare the bird off. Later (17-18th century), the image of Sirins changed and they started to symbolize world harmony (as they live near paradise). People in those times believed only really happy people could hear a Sirin, while only very few could see one because she is as fast and difficult to catch as human happiness. She symbolizes eternal joy and heavenly happiness.

The legend of Sirin might have been introduced to Kievan Rus by Persian merchants in the 8th-9th century. In the cities of Chersonesos and Kiev they are often found on pottery, golden pendants, even on the borders of Gospel books of tenth-twelfth centuries. Pomors often depicted Sirins on the illustrations in the Book of Genesis as birds sitting in paradise trees.

Sometimes Sirins are seen as a metaphor for God's word going into the soul of a man. Sometimes they are seen as a metaphor of heretics tempting the weak. Sometimes Sirins were considered equivalent to the Polish Wila. In Russian folklore, Sirin was mixed with the revered religious writer Saint Ephrem the Syrian. Thus, peasant lyrists such as Nikolay Klyuev often used Sirins as a synonym for poet.

PS: Btw it really sucks that tumblr doesn’t let people upload gifs with less than 10mb, makes us optimize our gifs and even then it optimizes them even further in theyr servers to 3mb i believe

#Mythology#russian#sirins#sirin#myth#folklore#greek#persian#indian#gods#syrian#kiev#treeoflife#creature#legendary#bird#japan#tengu#folktales#saints#genesis#mountains#art#artist#surreal#trippy#glitch#8thcentury#paradise#photomanipulation

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

art nouveau my beloved inspiration for art!

#also now. apparently. ivan bilibin’s illustrations of russian folktales#they’re so pretty#they do remind me of art nouveau. same time period. but i don’t think it’s necessarily the same genre#however both his art and the works of mucha. for example. have shared inspiration from japanese woodblock prints#so. they do look similar in that regard.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

hide away with me in the blue of night

close up✨

#illustration#illustrator#illustration on tumblr#fantasy#gay#lesbians#folktale#firebird#gay romance#digital art#a reimagining of a Russian folktale#mine art

3 notes

·

View notes