Note

Your post on Bechstein's "Hansel and Gretel" makes me think Humperdinck's opera must have been inspired more by that version than by the Grimms'. The opera also features a desperate mother instead of a wicked stepmother and has both parents happily reunite with the children in the end. It also has the Witch urge Gretel to look in the oven to "see if the gingerbread is brown yet" rather than to "feel if it's hot enough," and has Gretel be warned of the Witch's real intent (in the opera by Hansel) rather than guessing it herself.

Well if there are these elements, yes, the opera is DEFINITIVELY based on Bechstein's fairytale rather than the Grimm's.

Though ultimately we can say that the Grimm are still down there in the end, because Bechstein wasn't just aware of the Grimm as his direct predecessors - he was literaly inspired by them and when he originally wrote his versions of their fairytales (such as "Hansel and Gretel" here), it was mostly as an "answer"/expansion/continuation of the Grimm's own tales, so to speak. I think I said it before but the first editions of the brothers Grimm fairytales were not meant for your "average audience" - they were scholarly, "scientific" editions mostly aimed at folklorists and linguists and people who were interested in German culture. The brothers only realized people bought their book as an entertainment afterward, and then decided to re-edit and modify their book to become a more "regular" fairytale book.

Meanwhile, Bechstein directly aimed at writing a book that could be read by parents to their children, or casually enjoyed by the average reader not interested in small obscure nonsensical folktales - which not only explains the aim of his rewritings, but also why his book had an immediate success in Germany that overshadowed the Grimms, and why the Grimm's tales had to take their time to "build" themselves as the dominant "fairytales for children".

So yes, very likely the opera is based on Bechstein's version, especially since as I said Bechstein's tales were more well-known than the Grimms in Germany itself for quite some time (and we can still see this in a lot of German media which takes elements from Bechstein's variations rather than the Grimm's takes).

[That being said I do want to precise a little detail with Bechstein - I think twenty or so years after the publication of his fairytale collection, he ended up editing his book thoroughly. And what he did was add a bunch of new tales not originally present, but more importantly remove a good deal of others. And those removed tales included those that were too similar/overlapped too much with the Grimms. For example, I got my hands on a recent French translation of Bechstein's fairytales, complete and all, but the problem is that it is based on the later editions, so tales like "Hansel and Gretel" and "Little Red Riding Hood" are absent, and merely listed in appendices as tales that were cut from the book - so I had to go check them online to have the text. Might also explain why today we tend to forget they exist.]

#ask#hansel and gretel#bechstein's fairytales#ludwig bechstein#hansel and gretel opera#humperdinck's hansel and gretel#german fairytales

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

I will say this: the mini-series The 10th Kingdom, the comic book Fables, the book series The Sisters Grimm and the TV show Once Upon a Time are for me part of a same "set" of fairytale media.

More specifically, despite their differences, considering their similarities, these four media that mix the "fairytale-crossover world" with "fairytale urban fantasy" are also tied together, outside of the time context which makes them close to each other, by their very... "American-ness" I will say? Each one of them is VERY, very American, in their own different way.

It doesn't help that some of them literaly "feed" off each other (like Once Upon a Time out of Fables), but, while they are very different (and in fact it is interesting to compare where these works differ), they still kind of feel to me as part of a same specific whole, born out of a same time era, a same cultural context, a same American view of fairytales, and a same... "worldbuilding purpose" I will say?

I'm not going anywhere with this but for me these are somehow "linked" into a chain.

#the sisters grimm#the 10th kingdom#once upon a time#ouat#fairytale media#fables#fables comic book#fairytale series

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

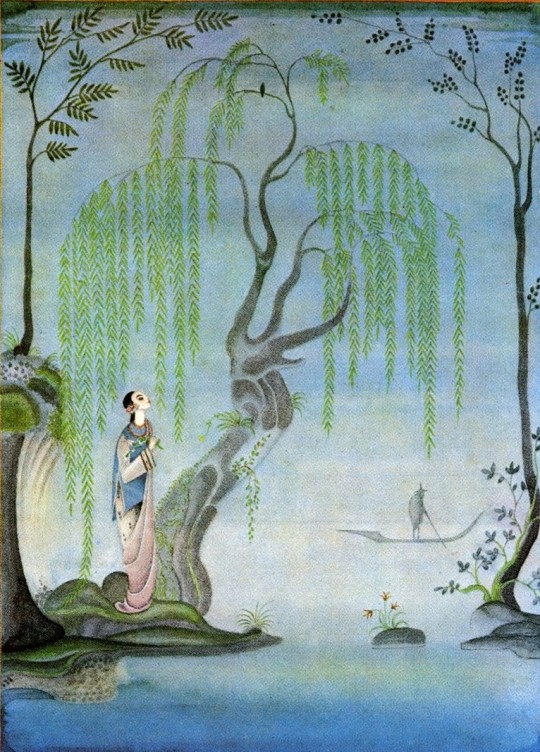

Illustrations from The Fairy Tales of Hans Christian Andersen by Kay Nielsen (1924)

641 notes

·

View notes

Text

I just noticed a recurring motif among these Sicilian fairy tales that is so incredibly well-suited for fanfic:

A princess sees a handsome young man (usually a prince in disguise) making eyes at her in the marketplace and begs her father the king to make him a royal servant, because he is so beautiful.

The king complies, because he's too fond of her to say no, and makes the hero a stable boy or gardener.

The princess now suddenly spends much more time out riding or requesting flowers, and then tells her father that the new servant is far too good for outside work and must become a servant in the castle.

The king complies, but soon enough the princess requests that the new manservant is made her personal page. By now the king is getting very nervous, but he still can't say no to his daughter.

The princess and the page manage to keep up the charade a little longer before the princess goes to the king and outright demands to let her marry her favourite.

The king gives the hero three "impossible tasks" that are meant to kill him, but naturally he accomplishes them all through trickery or supernatural intervention and the clandestine lovers get their way.

The pining, the flirting, the sneaking around, the devotion— do you see my vision?

253 notes

·

View notes

Text

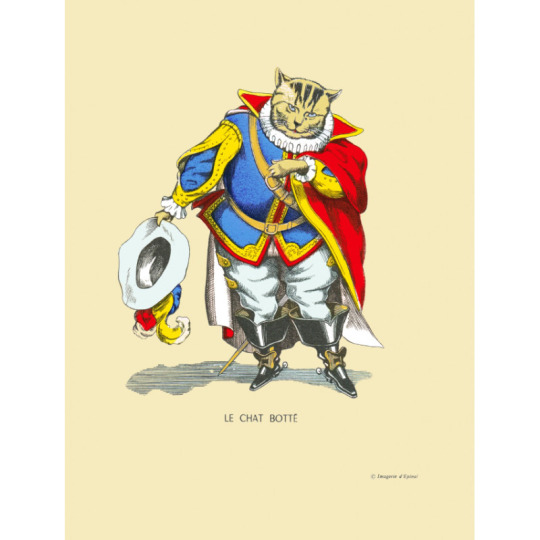

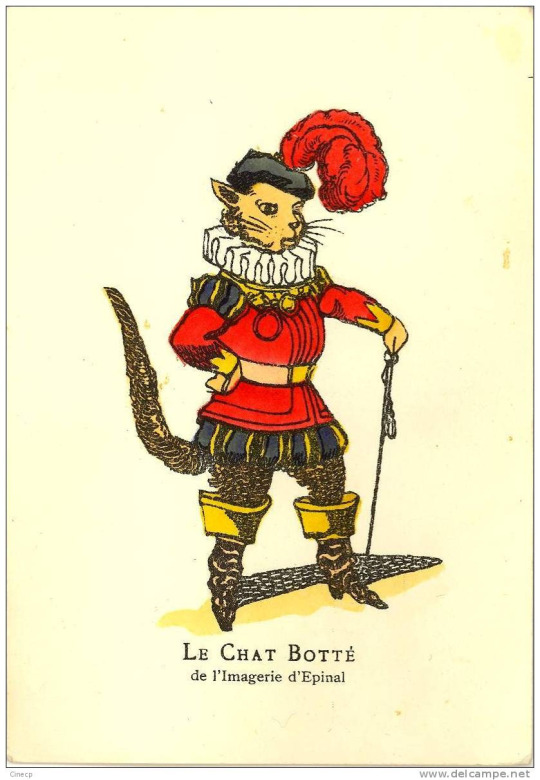

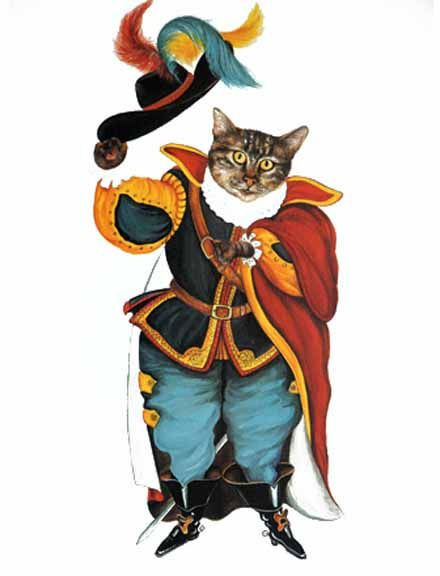

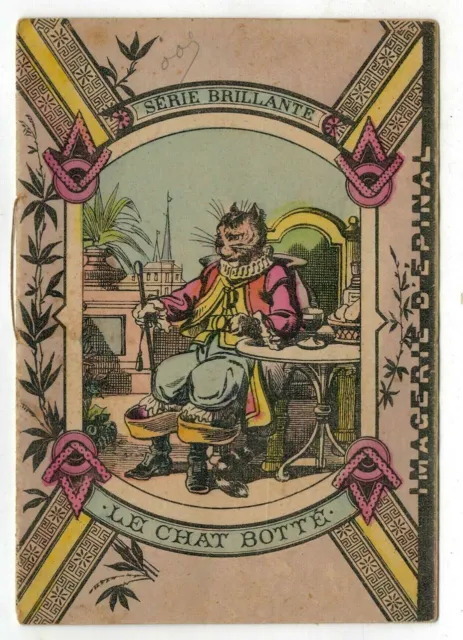

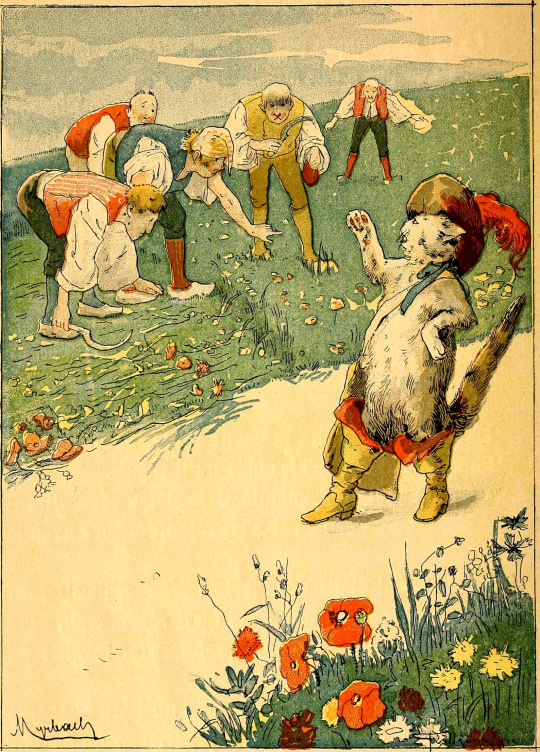

Various old depictions of Puss in Boots/Le Chat Botté (the one you see twice is especially famous as it is one of the most emblematic images of the imagerie d'Epinal industry - to the point Epinal used it as their official symbol for the imagerie d'Epinal card game and the image d'Epinal stamp).

#puss in boots#le chat botté#illustrations#images d'epinal#epinal images#imagerie d'epinal#epinal imagery#french things#fairytale aesthetic#fairytale art

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'd like to give props to this prince from the Sicilian fairy tale "Beautiful Angiola" for being in it for the long haul:

"Furious, [the witch] cast a curse on beautiful Angiola: "May your beautiful face be turned into the face of a dog!" she yelled. Within seconds Angiola's beautiful face was transformed into the face of a dog. The prince became very distressed and said, "How can I present you to my parents now? They'll never allow me to marry a maiden with a dog's face." He took her to a small cottage in which she was to live until the evil curse could be ispelled, and afterwards he returned to his parents and lived with them. However, whenever he went hunting, he visited poor Angiola."

(Gonzenbach, trans. Zipes, 2006, p. 51)

I absolutely adore the implication that it's genuinely only his parents' probable refusal that prevents him from marrying her anyway. Finally a proper Prince Charming. (He's proven right too, because when he presents her to his parents after the curse is broken, it's stated that they are immediately won over specifically by her beauty. Probably because she's a peasant girl without a dowry.)

Other fantastic details in this Rapunzel-like folktale:

The witch has a guard donkey for her garden

The witch's tower is furnished with living furniture and household objects that can speak and eat

The witch's own pet dog persuades her to break the curse on Angiola, arguing that she has been punished enough

140 notes

·

View notes

Photo

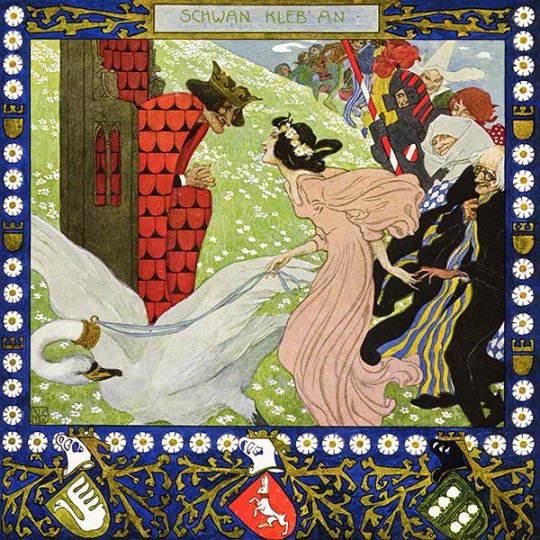

In Ludwig Bechstein’s fairy tale ‘Schwan, kleb an’, anybody who tries to pluck a feather from the beautiful swan will stick to it. The long parade of people stuck to the bird makes a princess who has never smiled laugh. The owner of the swan so wins her hand.

@VeraNijveld

28 notes

·

View notes

Note

I'll add something, @penguinofspades because I went really short and concise here - too short probably. I wish to say that I answered specifically about how Perrault depicted ogres in his fairytales - but it does not connect in an obvious way to how French people and French culture depicts ogres today. And I am not speaking of the American phenomenon of sticking "ogre" on what is very obviously an orc (or an oni in the case of manga and anime).

While yes Perrault wrote the ogres as I described above, there's a lot of things Perrault wrote that French mainstream culture/popular culture forgot entirely about. It is a bit like when you ask someone "How did the story of Sleeping Beauty went in Perrault's book"? Perrault's full story is not the one that is the mainstream reference today, or the one children are taught today - due to influences and overshadowing by the Grimm's Briar Rose and Disney's Sleeping Beauty, but also due to the mass-spreading of Perrault's text amputated from the whole second part. And with the ogres it is a bit of the same.

Because throughout the retellings and rewritings of the French classics, the influence of French folklore, the influence of fairytales from other cultures and the development of specific visuals for popular imagery (the famous "imagerie d'Epinal" which literaly shaped the way the fairytales were viewed for two centuries), the ogre of common, mainstream French culture does not fit Perrault's description anymore.

I won't make a full dissertation here, but some bullet points would be:

As I evoked above, ogres became giants in popular culture. It helped that in folktales (and in the writings of other authors like madame d'Aulnoy) they are giants - but today either an ogre is defined as a "man-eating giant", or is said to be much larger than a regular human being (Doré's illustrations helped)

A lot of elements from Perrault were lost such as the hooked nose, the grey eyes or the "magic" within ogres - the only magical thing people kept about them are the seven-league boots. The large mouth with pointy teeth does remain though.

A trait not present within Perrault but very common today is the hairiness of ogres. It is a common habit to depict the ogres with long, wild, shaggy hair and/or a big, bushy beard, and/or a very hairy body.

There's probably more to say but I just wanted to highlight this because I don't want you to imagine that the way Perrault described ogre is like a stone-engraved canon. The popular image of an ogre in France today actually uses Perrault's tale as merely one of its sources (and anyway, given ogres themselves are regularly confused and fused with other entities such as giants and bogeymen and ghouls and trolls ; and witches in the case of ogresses ; ogres end up being quite "fluid" today)

This might sound stupid, but what are the characteristics of fairytale ogres, particularly how Charles Perrault describes them?

There is no stupid question on this blog! (Except if someone really pisses me off, then all their questions will be stupid)

It is quite easy to answer this because we only have three ogres in all of Perrault's fairytales, so identifying the main traits is fast. They come from "Puss in Boots", "Little Thumbling" and "Sleeping Beauty". I'll recap shortly.

Eat humans. That's the main trait of an ogre. They eat human flesh, though they don't eat all the humans they see on the spot, mind you. Ogres prefer the flesh when it is young, tender, fresh and pretty. So they prefer pretty young people (Sleeping Beauty) to ugly old ones (that's what spares the ogre's wife, her age, she is too old to be edible). And this is why they go crazy over children, which for them is the most delicious meat. Literaly: the ogres are repeatedly said to be literaly jumping on children as soon as they see them, and to always want to eat them on the spot. (Another ogre trait: they are not very patient beings, and they have a hard time waiting)

Even outside of eating humans, they tend to be food-obsessed people - ranging from Little Thumbling's ogre who eats enormous quantities of food (entire animals to himself), to the ogress-queen who insists on having the most fashionable and delicious sauces with her meals.

Ogres are wealthy, and powerful in a social or political way. People tend to forget this, but the ogres of Perrault range from a literal queen (who was married by the king because of her immense wealth) to a lord who owns so many lands even the king is amazed. We don't know the social class of Little Thumbling's ogre, but he still lives in a large mansion and owns a huge treasure. Insert your joke of "the rich eat the poor" (except ogres also eat the rich - see the Sleeping Beauty case)

Ogres have something magical to them, ranging from owning magical items (Little Thumbling's seven-league-boots) to having actual magical powers (Puss in Boots' ogre is a shapeshifter)

Ogres are wicked and bad people who collect all sorts of vices, but they are all painted as brutal bullies, and as cruel beings who delight in scaring people or making them suffer. Oh yes, and if you cross an ogre, they will hunt you down mercilessly to enact their revenge, because ogres are very vengeful (see the ogre's hunt for Little Thumbling and his brothers, or the ogress' decision to have everybody executed for deceiving her)

When ogres have a family, they have a... very bizarre and complicated set of relationships mixing fear and love and abuse and familial respect. On one side, we have an ogre who is an abusive husband (and yet told to be a good husband enough that his wife loves him very much), and adores his daughters (he only eats them by accident) ; on the other, an ogress who lives peacefully with her husband, who refuses to harm or upset her son (son who both loves her a lot and still fears her), but who wishes to kill on the spot her daughter-in-law and grandkids... Oh and they are known to apparently regularly invite over friends to share their meals (at least if they don't end up devouring the planned meal before the guests arrive)

Are ogres giants? In Perrault's fairytales, no. Everybody knows of Gustave Doré's famous illustrations depicting ogres as giants, but this comes from A) other authors depicting ogres as giants and B) oral/popular/folkloric fairytales and legends mixing ogres and giants. So by the time Gustave Doré illustrated the fairytales, ogres were thought of as giants - but Perrault never writes anything about them being giants, and in the first illustrations of his fairytales they are depicted human-sized. At most he implies that the ogres are big/large/tall/heavy beings, but no different from a big, tall man.

Unlike the modern idea that ogres are inhuman monsters - in Perrault's fairytales, everything indicates that ogres look a lot like humans, and are very close to them. They are inserted in the human society as kings and queens (unlike fairies for example who are "outside" elements), they can crossbreed with humans (and if Sleeping Beauty is any clue, half-ogres looks so much like humans you can't tell they're ogres), and in the case of the ogress-queen, only her intimates know about her ogress nature - the rest is just unconfirmed rumors running around the court. (And Gustave Doré had caught on this, which is why he had his ogres looking like almost regular people). Perrault himself defines ogres in his notes as "wild men/savage men".

The only physical traits Perrault indicates about ogres (beside them having booming voices, and possibly being quite large and big people), are facial traits. They all come from the little ogresses' descriptions in Little Thumbling. Three of them are said to make ogresses "ugly" by 17th century standard - a hooked nose, round grey eyes, and a very large mouth filled with long, spaced-out sharp teeth. A fourth however is said to make them pretty by those same standards - because their diet of meat and flesh gives them a "pretty skin tone/beautiful colors/a healthy skin color".

If the same Little Thumbling fairytale is to be believed, ogre-children start their cannibalistic diets by sucking up the blood of little children. Then they presumably move to eating the children - but in their early years they just bite like vampires.

Oh yes and how could I forget. THE other main defining trait with their gluttonous cannibalism: their sense of smell. Ogres can smell "fresh meat" (la chair fraîche is the consecrated French expression). It is how the ogre of Little Thumbling guesses there are children hiding in his house, he smells them, and the ogress-queen is also said to go randomly go in the courtyard to sniff out animals like a wild beast.

I think these are pretty much the big defining traits of ogres in Perrault's fairytales. Of course, I simplified stuff, but this is the core knowledge to have about what ogres ~ Perrault style ~ are.

72 notes

·

View notes

Text

An Epinal image illustrating La Fontaine's fable, The Wolf and the Lamb.

#image d'épinal#epinal image#illustration#la fontaine's fables#fables#la fontaine#the wolf and the lamb#le loup et l'agneau#french things

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

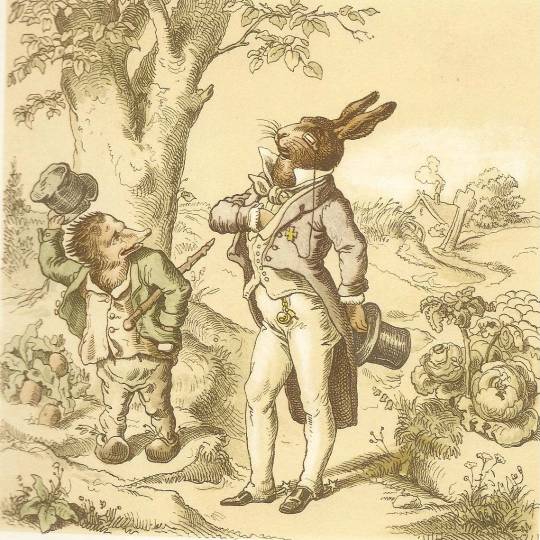

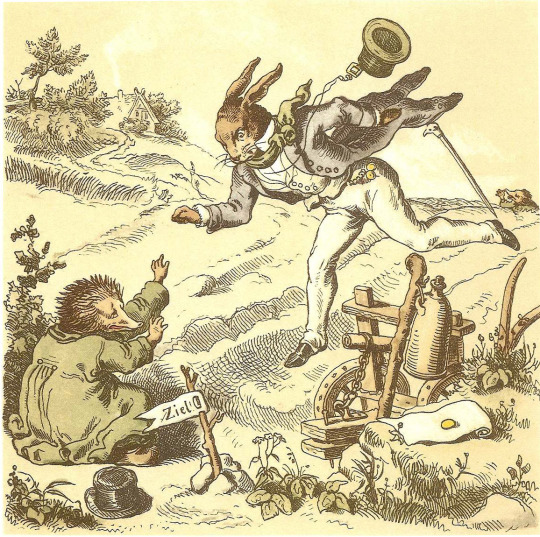

Gustav Süs - The race between the hare and the swineherd.

Cover and pages of a low-saxon edition published 1855 with illustrations by Gustav Süs.

The Hare and the Hedgehog or The race between the Hare and the Hedgehog (Low Saxon:"Dat Wettlopen twischen den Hasen un den Swinegel up de lütje Heide bi Buxtehude", German: "Der Hase und der Igel") is a Low Saxon fable. It was published 1843 in the 5th edition of Grimms' Fairy Tales by the Brothers Grimm in Low Saxon (KHM 187) and in 1840 in Wilhelm Schröder's Hannoversches Volksblatt under the full title Ein plattdeutsches Volksmärchen. Dat Wettlopen twischen den Hasen un den Swinegel up de lütje Heide bi Buxtehude. Ludwig Bechstein also published it in German in his Deutsches Märchenbuch (1853).

#reblog#fable#german fairytales#german fables#the hare and the hedgehog#illustrations#gustav süs#grimm fairytale#bechstein fairytales

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Richter, Adrian Ludwig: Titelblatt zu Bechsteins Märchen

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Do you know about Ludwig Bechstein? Well you should.

But do not worry: if you never heard of his name until now, it is perfectly normal. In a similar way to madame d'Aulnoy in France, Ludwig Bechstein was one of the great names and influential sources of the fairytale in Germany, but fell into complete obscurity due to being overshadowed in modern days by a contemporary (Charles Perrault for madame d'Aulnoy, the brothers Grimm for Bechstein).

Ludwig Bechstein was, just like the brothers Grimm, a German collector of fairytales (Märchen in German), and just like them he published an anthology of them. However, whereas the brothers Grimm started publishing their work in the early 1810s with re-editions later on, Bechstein published the first volume of his collection in 1845, and the second volume in 1856.

And here's the thing: Bechstein was MUCH, MUCH more well-known in Germany than the brothers Grimm, for the rest of the 19th century. While yes the brothers Grimm were a big success and a huge best-seller, Bechstein's fairytales were even more so. In fact his fairytales were THE de facto German fairytales of the 19th century - until the brothers Grimm's international celebrity (because their fairytales had crossed the Germanic frontiers into English and French-speaking countries, while Bechstein's had not) came back and made their own fairytales overshadow, and then completely eclipse/bury Bechstein's own fairytales.

Why is this important? Because Bechstein had in his collection several fairytales that overlapped with those of the Grimm: for example, as I will show above, both collections had an "Hansel and Gretel", and " Little Red Riding Hood". But while we know today the Grimm's version better, it was the Bechstein's version that the 19th century children knew about. And there is one big difference between the two sets of tales: while the brothers Grimm were obsessed with an "accuracy" of the stories (or what they believed was an "accuracy"), stitching stories together or writing them so as to create what felt like a traditional oral story as it would be told to you by a random German person, Bechstein allowed himself a more "literary approach". He never reached the level of an Andersen or a d'Aulnoy that would entirely rewrite a folk-tale into a long poetic epic... But he allowed himself to correct inaccuracies in the stories he collected, and to add personal details to make the story fit his tastes better, and to develop the dialogues into more than just nonsensical little rhymes, so while he kept short and simple stories like the Grimms, they definitively were more literary stories.

To give you two good examples of the differences, here are Bechstein's changes to the two stories I described above.

The main change within Little Red Riding Hood is Bechstein making the girl more intelligent and well-meaning than in the Grimms version, and the Wolf's deception even more devious. When the wolf tells the girl she could go pick up flowers and play outside of the path, like in the Grimm's tale, Bechstein's Riding Hood stops and asks roughly (not a quote I recap here): "Hey, mister Wolf, since you know so much about herbs and plants within this forest - do you know about any medicinal plant around, because if there is an herb that could heal my sick grandma, it would be super cool!". And the wolf jumps on the occassion, pretending he is a doctor - and he lists to her a whole set of flowers and herbs and berries she can pick up that would heal her grandmother... except all the plants he describes to her are poison, and the Wolf just mocks his intended victim. The joke also relies on the fact that all the plants he lists are named after wolves, with the beast convincing the girl it is because wolves are good and great things. (There's the wolf's-foot, the wolf's milk, the wolf's berries, the wolfswort - names which do correspond to real-like plants such as the spurge laurel or the aconit).

The ending is also slightly modified. The hunter is attracted to the grandma's house by hearing the unusually loud snoring of the wolf - he thinks something is wrong with the grand-mother, maybe she is dying, only to find the wolf in her place. He immediately grabs his rifle to kill it but then pause wondering "Hey, the little grandma is nowhere to be seen... and she was a scrawny woman... Better check if he did not eat her". And so he opens the wolf's belly (and the wolf is still asleep during all that, he really is a deep sleeper). When the humans decide to put stones in the wolf's belly, they explicitely reference in-universe the "Wolf and the seven goats" story, which gives them the idea. (Quite a fun and accurate detail since we know that the brothers Grimm attached the episode of the stone to the Little Red Riding Hood story by taking it from the "Wolf and the seven goats" one)

As for Hansel and Gretel, the witch is described differently from the Grimms (she is still a very, very old woman who has something wrong with her eyes, but she isn't red-eyed like the Grimm, rather she has "grass-green" rheumy eyes, and she has no cane or crutches, Bechstein rather insisting on her being a hunchback and havin a very, very large nose.) But the main difference occurs in the climax, which is very different from the Grimm.

The witch still tries to push Gretel in the oven, but she doesn't ask the girl to check if it is "hot enough". Rather she put bread in it to go with her Hansel-roast, and she asks the girl to check if the bread is brown yet. And Gretel is about to obey... when the snow-white bird that led them to the house reappears and warns her of an upcoming danger with human words. The girl immediately guesses the trick, and pushes the witch in the oven. Second big change: the "treasures" the children obtain are not the witch's, nor do they find it on their own. As they exit the house, the treasure literaly rains on them - because all the birds of the forest arrived and dropped the precious items on them while singing "For the crumbs of bread / Pearls an gems instead". As the children understand, the birds were grateful for what they believe was food offered to them (the bread crumbs) and reward the children with the treasure.

Oh yes and the mother (no stepmother here) doesn't die. Rather she and her husband are miserable in their house because they regret leaving their kids, so they are very happy when they return, and with the treasure they all are certain to never go hungry again. Happy end. (Because here the mother isn't a bad person like in the Grimm - she just really, REALLY was a desperate woman who didn't want to see her own children die before her eyes)

#little red riding hood#hansel and gretel#german fairytales#ludwig bechstein#bechstein fairytales#brothers grimm#grimm fairytales#grimm fairy tales#german fairy tales

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Illustration from The Wind's Tale for Hans Christian Andersen's Fairy Tales by Dugald Stewart Walker (1914)

659 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shapeshifting Dragons

I sometimes see people wonder if the idea of a dragon that can take on a fully human appearance is a modern fantasy invention. Or solely inspired by (East) Asian dragons, which are almost invariably noble and frequently appear human. Because European folklore is more well known for “dragon slayer tales”, in which the dragons are purely beastly. But! Slavic folklore absolutely has dragons who are capable of transforming themselves into (beautiful) humans!

The dragons from Slavic fairy tales still have typical “western” dragon characteristics (wings, scales, claws, maw), but they often act far more human than animalistic. They frequently live in castles, use weapons, sometimes even ride horses, write letters, or get married to humans. And some are described as fully shapeshifting into humans:

Dawn, Evening, and Midnight (Afanasev, 1866, trans. Guterman, 1946)

Three princesses are abducted by a whirlwind and three brave brothers Evening, Midnight and Dawn set out to find them. Dawn finds the youngest princess in an underground realm in a castle. She greets him, feeds him, gives him strengthening magic water and then: “At this moment a wild wind arose, and the princess was frightened. ‘Presently,’ she said, ‘my dragon will come.’ And she took Dawn by the hand and hid him in the adjoining room. A three-headed dragon came flying, struck the damp earth, turned into a youth.” The princess puts sleeping potion in the dragon’s wine, picks the lice from his hair (implies he is still human) until he falls asleep. She calls Dawn and he cuts off the dragon’s three heads (implies he’s full dragon again) and burns the body. He then rescues her sisters from a six- and twelve-headed dragon. The three princesses marry the three brothers.

The Footless Champion and the Handless Champion (Afanasev, trans. Guterman)

Two champions, Marko and Ivan, decide to steal a priest’s daughter to be their sister and housekeeper. Once they go on a week long hunt and when they return the girl looks ill and thin. “She told them that a dragon had flown to her every day and that she had grown thin because of him. ‘We will catch him,’ said the champions. (…) About half an hour later, the trees in the forest suddenly began to rustle and the roof of the hut shook: the dragon came, struck the damp earth, turned into a goodly youth, sat at table, and asked for food.” Ivan and Marko seize him and thrash him until he begs for mercy, promising to show them the water of life and the water of death. He tries to trick them into jumping into the lake of death, so they throw him in “and only smoke was left of him.” They do bring the priest’s daughter back home before carrying on with their other adventures. [The concept that a dragon’s presence can drain a maiden of her life force shows up in other stories too, but in this particular context it almost seems like the dragon is just? eating her portion of the food? Also the fact that she was abducted from her home by the two supposed heroes and the dragon is only visiting and asking for lunch really puts this into a weird perspective.]

King Bear (Afanasev, trans. Guterman)

A tsar’s son and daughter are abducted by the King Bear but eventually escape with the help of a magical bullock who conjures a lake of fire that the bear cannot cross. They live by its shore for a while in a fine house and Ivan hunts for their food. “Meanwhile Princess Maria went to the lake to wash clothes. As she washed, a six-headed dragon came flying to the other shore of the lake of fire, changed into a handsome man, saw the princess, and said to her in a sweet voice: ‘Greetings, lovely maiden!’ ‘Greetings, good youth!’ ‘The old wives say that in former times this lake did not exist; if a high bridge spanned it, I would come to the other side and marry you.’ ‘Wait! A bridge will be here in a trice!’ answered Princess Maria and waved her towel. In that instant the towel spread out in an arc and hung above the lake like a high and beautiful bridge. The dragon crossed it, changed into its former shape, put Prince Ivan’s dog under lock and key, and cast the key into the lake; then he seized the princess and carried her off.” When Ivan finds his sister missing and his dog locked up he goes to ask help from Baba-Yaga, finds the dragon, kills him, and takes his sister home. [This story ends with the standard “they began to live happily and prosper”, but it really seems like Ivan should have asked Maria if she was even in need of rescuing.]

So there we are! Proper folklore roots for all our mysterious strangers with a hint of scales around their flickering eyes~

#reblog#dragons#russian fairytales#afanassiev fairytales#dragons in fairytales#fairytale princes#shapeshifters

319 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thank you so much for doing this breakdown! This book is only available to me in bookshops, but I had refused myself to buy it because from what I could see it just looked like someone had taken the exact text of the stories and just changed the pronouns - and even with pretty pictures added to this, I wasn't going to pay as big a sum of money as they asked me for something I could type on my own X)

So it is very useful to have someone else's thorough notes and experience to be able to better judge the book

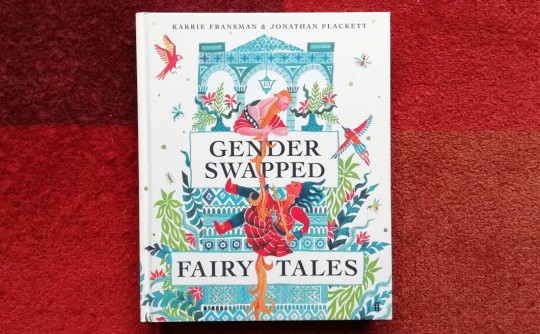

Gender Swapped Fairy Tales

by Karrie Fransman & Jonathan Plackett (2020)

My mother-in-law got this book and for obvious reasons she lent it to me. I have far more thoughts about it than I expected, so I thought I'd do a little ramble review for those of you that are interested in looking at fairy tales from a gender perspective:

Firstly: I think this is a very interesting, well introduced project

Fransman and Plackett, who are married, explain in the introduction that they didn't want to retell fairy tales but specifically chose to simply swap out all relevant gendered words (with a computer program created by Plackett) in an attempt to "illuminate and disrupt the gender stereotypes woven into the stories we've been told since childhood". This is also the reason, they explain, why they've stuck to a very binary approach to gender, not just changing "princess" to "prince" etc, but also changing "dress" to "suit" and so on. They used the text from the Langs' Fairy Books and tried to change as little as possible, to show how different it would be to have Cinderella's actions attributed to a man and Hansel's to a girl. It's a solid concept and I appreciate the effort they put into it.

Second: It's a beautiful book with gorgeous illustrations

Just look at these takes on Rapunzel and Beauty and the Beast, delightful!

So, if this looks like something that's your thing, I encourage you to check it out!

But of course I also have many nitpicky folklore feelings about this, so for anyone who is interested I will put those under the cut~

So, folklore feelings and ruffled fairy tale feathers:

This is a project with a very specific concept (complete binary gender swap, but edit as little as possible besides) and it's unfair to fault it for sticking to it, but I do think that not every fairy tale is equally well suited for such a treatment. I also think that the authors cheat a little here and there and if you start cheating then why not do it to make things a little more elegant?

Here are my thoughts on the gender swapped fairy tales this book contains:

Handsome and the Beast (Beauty and the Beast)

This one works very well, I think. Having a female merchant be the protagonist of the first half of the story and a male romatic hero the willing captive of a female beast changes the feel of the story completely while leaving all its main elements intact. It's interesting to see a female character lose her monstrous characteristics through the dutiful devotion of a man and it also highlights the uncomfortable parts of the story by recontextualizing them. I like it!

Cinder, or the Little Glass Slipper (Cinderella, or the Little Glass Slipper)

From a story perspective this one is as good as the previous one. It's fun to have an evil stepfather and stepbrothers obsessed with beauty, a fairy godfather, and a beautiful boy who longs for a ball. However, I really don't think "Cinder" has the same feel as "Cinderella" as a name. In the Langs' translation the protagonist is called both Cinderella and Cinderwench, which they swapped for Cinder and Cinderboy. This isn't quite right. "Wench" is a much nastier word than "boy" and "Cinder" is just the full noun not made into a name. If more editing was allowed, I would have taken inspiration from Norwegian fairy tales about Askeladden and called the protagonist "Ashlad".

How to Tell a True Prince (How to Tell a True Princess / The Princess on the Pea)

This one is silly, but so is the original. You can really tell that this is a literary fairy tale. But honestly the nonsense of it call is kind of the point and a princess looking for a dainty prince who bruises like a peach is a story worth telling.

Jacqueline and the Beanstalk (Jack and the Beanstalk)

There is nothing wrong with this one at all, but I don't like it much because there are plenty of trickster tales with women as the protagonists. Changing Jack into a girl doesn't really have much bearing on the story for me and it doesn't create a sort of story that's all that new. If I wanted to a girl defeating a giant I could also read Molly Whuppie. But I do see that Jack's characterisation of being silly and thoughtless, brave and brazen is unusual to see for a heroine, so there is that.

Gretel and Hansel (Hansel and Gretel)

Similar to the previous one I don't think this particularly benefits from a gender swap. Hansel and Gretel are both clever in their own way. There is a clear difference in Gretel being the one who cries more and has to do chores for the witch, but still. It does make me think though, because the male witch/wizard wanting to eat Gretel makes me more uncomfortable. One thing I find very funny in this one is that they didn't just change the duck they meet along the way into a drake (as in male duck, but now seems like a dragon), they also have the wizard call Hansel a "silly gander" instead of a "silly goose".

Mr Rapunzel (Rapunzel)

Now here I get very picky. I think "Mr Rapunzel" is a ridiculous way to solve for the fact that leaving it unchanged would make it seem like the same fairy tale. In fairy tales people are hardly ever addressed with titles like Mr or Mrs and it completely breaks the tone. I would have just kept it Rapunzel, as they do in the actual text of the story. What I do appreciate is the complete ambiguity in this version as to whether it is the husband or the wife who gives birth to the baby. But here is also the first moment of cheating: they have Rapunzel grow a long beard. That is a decided change. A boy could grow long hair just as well as a girl, it did not need to be altered. But it is an amazing image. I'm all for it. But if you make this change because it's cool, you can change more things. The dynamic between the Evil Wizard, Rapunzel and the Princess is very interesting with swapped genders though.

Snowdrop (Snow White)

I wanted to yell about unnecessarily changing the name again, but Andrew Lang was the one that changed the name from Snow White to Snowdrop, so my yelling is directed at him. In this story the gender language program comes up with some changes I just don't like the sound of. "My Lady Queen" turns into "My Gentleman King", while I think "My Lord King" would work a bit better, and "My noble King" a lot better. It also changes the Princess' bodice being laced up so tight it nearly kills her to the Prince's shirt. That's one hell of a shirt. The preoccupation with beauty is interesting with a king and prince though, and the female dwarves are fun.

Little Red Riding Hood (Little Red Riding Hood)

This certainly is interesting, because it's one of the versions where both Grandmama (so Grandpapa in this version) and Little Red Riding Hood get eaten and never rescued. I would have liked to see a brave female woodcutter, but having this story of straying off the path and getting preyed upon for it be centered around a boy is definitely impactful. The wolf is introduced as "Mistress Wolf", which I don't love but since the Langs' originally chose "Gaffer Wolf", I can't really argue with that. I do argue with the way the wolf is illustrated though. Because they gave her a head of blonde hair on top of her fur and a red lipstick mouth.

The Sleeping Handsome in the Wood (The Sleeping Beauty in the Wood)

This is very interesting with the genders swapped. (Again could be read as the King giving birth, fun.) I'm all for armoured princesses climbing towers and falling to their knees at the sight of slumbering princes. This is also the Perrault version with the second plot where the in-laws want to eat the new spouse and the royal children, which adds the dynamic of the young Queen going to war while the beautiful King stays home and is endangered. The title irks me though. While I fully supported the use of "Handsome" as a name in the Beauty and the Beast story, I do not like it here. I'm sure there is something patriarchal about the way "beauty" can be used as a noun describing a person, while "handsome" cannot, but "the handsome in the woods" just sounds very jumbled to me.

Frau Rumpelstiltzkin (Rumpelstiltzkin)

Again with the unnecessary name change. "Frau" is an interesting pick, perhaps they were inspired by Frau Holle, but it's really not needed and it looks very forced. I don't like this story as much as most of the others, but mostly because it's not a very nice fairy tale to begin with. The romance isn't romantic, the kindness isn't kind, and changing the genders doesn't change that. The young king fighting to save his baby daughter is very charming though.

Mistress Puss in Boots (Puss in Boots)

Listen. If you insist on having a different title for it, go all the way with the old-fashioned language for animals and make it Pussy in Boots. Or go with the "Madame Puss" that is used in the story since the Langs' decided to use "Monsieur Puss" (hilarious). But the gender changes are fun in this. The Prince falling head over heels for the freshly-fished-from-a-ditch miller's daughter is very good.

Thumbelin (Thumbelina)

Another one by H.C. Andersen and very clearly a literary fairy tale. I really like the name change to Thumbelin and having a single (?) man wishing for a child and finding one in a flower is very lovely. I've always liked Thumbelina's aesthetic but rather disliked the story, everyone is forever trying to marry her against her will. I don't like the story more with a boy in the same position, but the change does hit hard because it.

If I had to pick a favourite from this book, I think it's Handsome and the Beast, but Cinder is also very fun with the genders reversed. I like this book very much as an experiment, but while I agree with the choice not to make it actual retellings, I wish a few more tweaks were allowed to make some parts flow more smoothly.

#reblog#gender swapped fairy tales#karrie fransman#jonathan plackett#fairytales with a twist#gender-swapped fairy tales#genderbent fairytales#book review

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

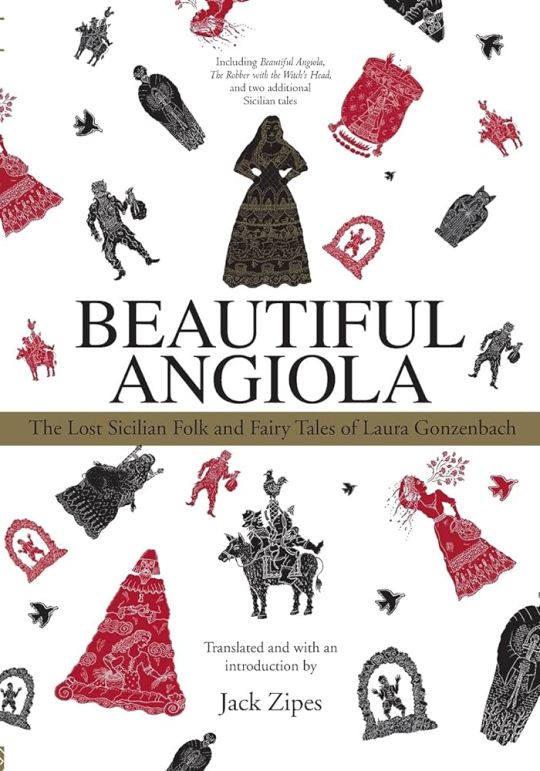

I just got Jack Zipes 2006 translation of Laura Gonzenbach’s 1870 Sicilianische Märchen (Sicilian folktales) and I’m jittery with excitement

There are 94 stories in this book and Gonzenbach collected most of them directly from (primarily) working class women in Sicily! And while we sadly know little about how she edited the tales, they are much less sanitized than many 19th century folklore collections and it’s likely she stayed much closer to the oral source.

Of course this is an English translation of a German text based on stories originally written down from a telling in Sicilian dialect, but the care and attention that has gone into them is almost tangible. I wish I could read it front to back right now instead of working

#reblog#hey look it is the book i told you all about remember#laura gonzenbach#sicilian fairytales#fairytale collections#references#fairytale book#jack zipes

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

The absolute details of this film are just insane. 😩

1K notes

·

View notes