#Ronald Blythe

Text

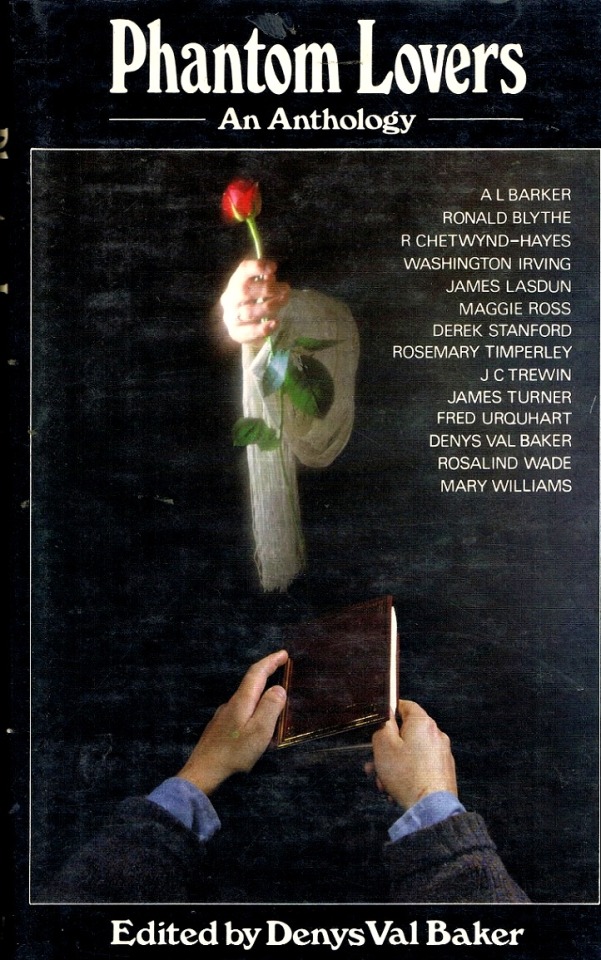

Denys Val Baker (editor) - Phantom Lovers - William Kimber - 1984

#witches#phantom lovers#occult#vintage#phantoms#lovers#william kimber#denys val baker#a.l. barker#ronald blythe#r. chetwynd-hayes#washington irving#james lasdun#maggie ross#derek stanford#rosemary timperley#j.c. trewin#james turner#fred urquhart#rosalind wade#mary williams#1984#anthology

29 notes

·

View notes

Photo

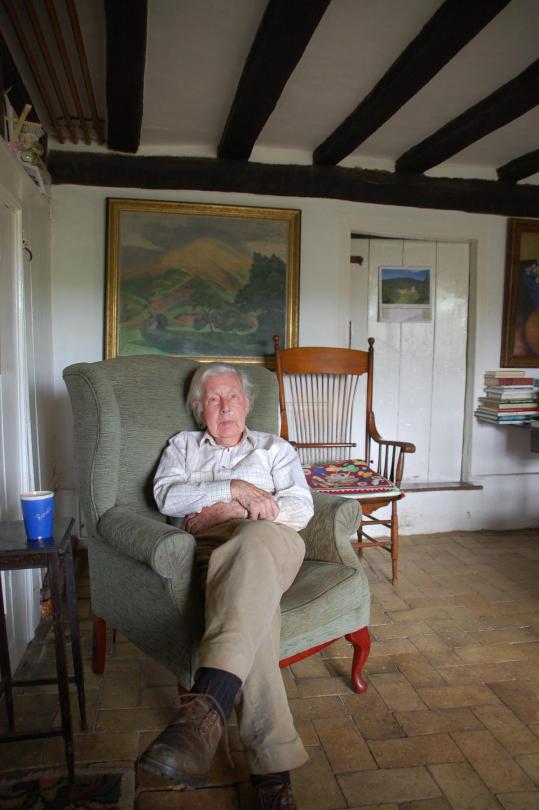

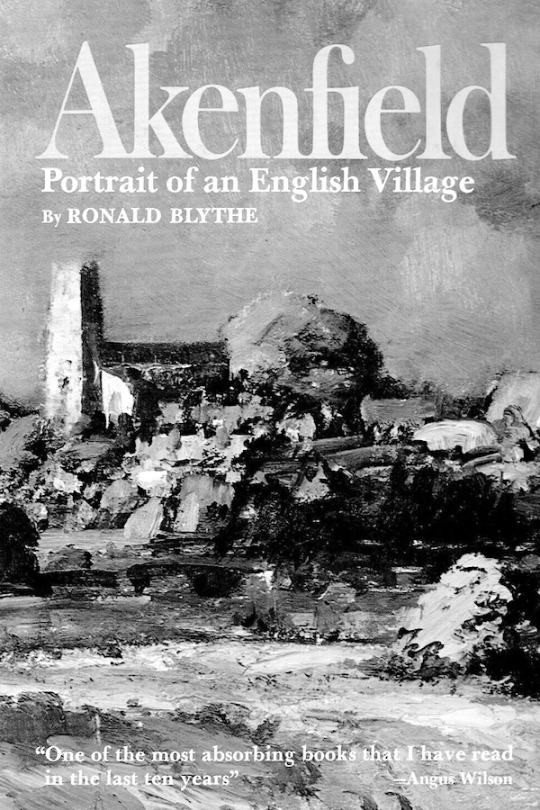

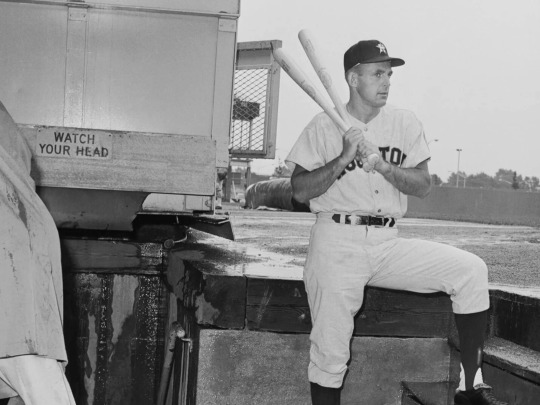

In the summer of 1967, Ronald Blythe cycled from his home in the Suffolk hamlet of Debach to the neighbouring village of Charsfield. There he listened to the voices of blacksmiths, gravediggers, nurses, horsemen and pig farmers. He gave them names from gravestones and placed them in a fictional village. Akenfield, a portrait of a rural life rapidly disappearing from view, was immediately acclaimed as a classic when it was published in 1969.

Never out of print and read and studied around the world, Akenfield made Blythe famous and perhaps overshadowed the many other fruits of his long years of writing – short stories, poems, histories, novels and, in later life, luminous essays and a superb weekly diary that the Church Times published for 25 years until 2017. Blythe, who has died aged 100, is regarded by his peers and many readers as the finest contemporary writer on the English countryside.

The eldest of six children, Blythe was born in Acton, near Lavenham, into a family of farm labourers rooted in rural Suffolk. His surname comes from the Blyth, a small Suffolk river, but his mother and her family were Londoners. His mother, Matilda (nee Elkins), a nurse, passed to him her love of books. Although Blythe left school at 14, by then he had already established a voracious reading habit – “never indoors, where one might be given something to do,” he remembered – which became his education.

His father, Albert, had served in the Suffolk Regiment and fought at Gallipoli and Blythe was conscripted during the second world war. Early on in his training, his superiors decided he was unfit for service – friends said he was incapable of hurting a fly – and he returned to East Anglia to work, quietly, as a reference librarian in Colchester library.

He befriended local writers including the poet James Turner, who helped his passage into a bohemian, creative Suffolk circle that included Sir Cedric Morris, who taught Lucian Freud and Maggi Hambling and lived nearby with his partner, Arthur Lett-Haines. Blythe “longed to be a writer”, he said, and he listened and learned – inspired by the example of poet friends including Turner (the unnamed poet in Akenfield) and WR Rodgers of how to live with very little money. “It was a kind of apprenticeship,” he once recalled.

Most importantly, in 1951 he met the artist Christine Kühlenthal, wife of the painter John Nash. Kühlenthal encouraged his writing and championed him: Blythe edited Aldeburgh festival programmes for Benjamin Britten and even ran errands for EM Forster, who took a shine to the shy young man. Blythe helped Forster compile an index for Forster’s 1956 biography of his great-aunt, Marianne Thornton.

Blythe’s first, Forster-inspired novel, A Treasonable Growth, was published in 1960. He followed it in 1963 with The Age of Illusion, a social history of life in England between the wars. He earned money from journalism, being a publishers’ “reader” and editing a series of classics – including one of his heroes, the essayist William Hazlitt – for the Penguin English Library.

After a stint living in Aldeburgh, recalled in an elegiac and characteristically discreet memoir, The Time by the Sea (2013), he moved to a cottage in Debach. In the mid-1960s, he was befriended by the American novelist Patricia Highsmith. “I admired her enormously. She was a very strange, mysterious woman. She was lesbian but at the same time she found men’s bodies beautiful,” he remembered. One evening, after a Paris literary do, they slept together; he told a friend they were both curious “to see how the other half did it”.

Blythe said the idea for Akenfield (he took the name from the old English “acen” for acorn) arrived as he tramped the Suffolk fields pondering the anonymity of most farm labourers’ lives. His friend Richard Mabey remembers it being commissioned by Viking as the lead title for a short-lived series on village life around the world.

Over 1967 and 1968, he listened to the citizens of Charsfield, recreating authentic country voices while somehow adding a poetry of his own. The result was a portrait of the “glory and bitterness” of the countryside: the penury and yet deep pride of the old, near-feudal farming life, and its obliteration in the 60s by a second agricultural revolution alongside the arrival of the car and television.

The village voices were never sentimental about country life, and nor was Blythe: as well as stories of how to make corn dollies, there were quiet revelations of incest, and the district nurse recounted the old days when old people were stuffed into cupboards. Old labourers remembered the “meanness” of farmers who had treated their workers like machines because the big rural families delivered a seemingly endless supply of farm-fodder.

Ecstatic reviews of this “exceptional” and “delectable” book in Britain spread to North America, where Time praised it, John Updike loved it and Paul Newman wanted to film it. But some oral historians were suspicious that Blythe had not recorded his conversations.

Blythe turned down a film offer from the BBC but eventually accepted a pitch from the theatre director Peter Hall, a fellow Suffolk man. Blythe wrote a new synopsis inspired by the unfilmable book, and Hall asked ordinary rural people to improvise scenes with no script. Blythe oversaw every day of filming and played an apt cameo as a vicar. Nearly 15 million people watched Akenfield when it was broadcast on London Weekend Television in early 1975.

Blythe’s next book, The View in Winter (1979), was a prescient examination of old age in a society that did not value it, at a time when more people than ever reached it. The “disaster” suffered by the old, he wrote, is “nobody sees them any more as they see themselves”. Blythe regarded it as his best book. While he was writing it, Kühlenthal died, and Blythe moved into the Nashes’ old farm, Bottengoms, to look after the elderly Nash. When Nash died a year later, he left the house to Blythe. There Blythe lived for the rest of his life, writing beautifully about his home in At the Yeoman’s House (2011).

In later years, Blythe drew praise for his short stories and essays, including a series of meditations on the 19th-century rural poet John Clare. Many writers who were later grouped together as “nature writers” became his friends, including Mabey, Robert Macfarlane and Roger Deakin.

Blythe never married, never lived with anyone, and kept his personal life veiled. Interviewed by the Observer in November 1969, he was judged “intensely private”. He disclosed nothing in his published writing about his love affairs with men, or indeed his one-night stand with Highsmith.

He was almost as reticent about his faith, but his writing was deeply suffused in his Christian beliefs and his knowledge of the scriptures. He was a lay reader – deputising for vicars across several parishes – and became a lay canon of St Edmundsbury Cathedral, but turned down the chance to become a priest.

Rowan Williams, the former archbishop of Canterbury and an admirer of Blythe’s writing, believed Blythe used the Christian year of festivals as “a steady backdrop” for his writing and thinking, which was liberated by his faith. The writer Ian Collins, a good friend of Blythe in his later years, felt it was Blythe’s lack of formal education or “training” that liberated his original thinking and elegant prose style.

Blythe was politically radical throughout his life, a Labour voter who joined peace vigils outside St-Martin-in-the-Fields in London. Friends were surprised when he accepted a CBE in 2017, around the time he was gently “retired” from public speaking and writing as his short-term memory faded. When he reached 100, he was still well enough to sign 1,500 copies of a new compilation of his best Church Times columns.

The old people who thrived in The View in Winter were those, Blythe concluded, who were able to preserve their “spiritual vitality, a vividness, an imaginative sort of energy”. This credo served him well as he grew older, although he was mistaken in another respect. The old, he wrote, are “cared for, surrounded with kindliness, and people are often interested in what they say; but they are not truly loved and they know it”.

Blythe was much loved in later life. A roster of devoted friends he called his “dear ones” visited him daily, supplied him with hot meals and ensured he could live out his years at Bottengoms.

🔔 Ronald George Blythe, writer, born 6 November 1922; died 14 January 2023

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at http://justforbooks.tumblr.com

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Home movie — The filming of Akenfield by Ronald Blythe.

I THINK THAT MY CHIEF SURPRISE is that it's all happening, as they say. The preliminaries have been so protracted and the idea so threatened by various aspects of the malaise affecting the film industry generally, that Peter Hall and my-self, glancing at each other across the farmyard, often find it amazing that we are actually shooting Akenfield. Initially I had great reservations about filming the book at all. In the first place, the tendency of film companies or television to want to turn every successful book into a picture is questionable. Writers are often mangled in the process. Anthony Burgess continues to protest about what occurred to his novel A Clockwork Orange when the film-makers got hold of it. My book presented unique difficulties inasmuch as it involved many friends and neighbours as well as deeply personal experiences drawn from a whole lifetime in the Suffolk countryside. Also, there was the problem of continuity; how did one film three generations in terms of work, belief, education and climate. For this is what Akenfield is really concerned with.

I met Peter Hall in London a few weeks after the book had been published and he told me of his Suffolk home; how my work had touched a deeply personal element in his life, and how, like all creative people, he felt a great need to express important things concerning himself and his family in artistic terms. He thought that a film based on Akenfield might achieve this. There would be no actors and as little as necessary of the general elaborations which accompany the making of a big film. That autumn I wrote a script based on the ideas in the book, on what people said and did. Roughly speaking, the pattern of this script involves a day in the past and a day in the present, a day of life and a day of death, and a day of summer and a day of winter. Within this pattern a century of Suffolk life works itself to a present-day conclusion.

It is a feature film and not a documentary, although every-body in it would be ploughing, shoeing, praying, marrying, harvesting, teaching, rook-scaring, factory-farming, digging up the past or concealing the present with all the actuality which the camera could catch. Peter Hall and I talked of Robert Bresson and his remarkable films of French country life. I even mentioned Man of Aran. A Suffolk friend of mine, Hugh Barrett, had accompanied Flaherty when he was making this classic. The script written, the agreements settled as to how we would resolve things generally, it took the super-human tact and imagination of a young producer named Rex Pyke to get our film financially and practically into motion. Then suddenly, after two years of negotiation—we started.

For myself it has meant starting off in hundreds of directions, returning, on the whole triumphantly, with the necessary spoils. Permissions to use old schools, fields, churches and chapels. Advice or artefacts from everybody within a thirty-mile radius and, most important of all, people. We auditioned scores of East Anglians for the little group of main roles and then literally went out into the highways and byways to collect country children, men and women for the large scenes. Many of the results deriving from this spontaneous casting have been a revelation to us all. I 'shall never forget seeing the first rushes of the 1900 village school scene and the forty or so local children miraculously slipping back in time (under the influence of hob-nailed boots, slate-rags, pinafores and thunderous iron desks) until they had become, by some mysterious chemistry better known to themselves than our costume department, the distant children in the sepia photographs which I had brought from our splendid Rural Industries Museum at Stowmarket.

The school building itself was fascinating. It lies just across the meadows from my house and was built in 1858, but has not been used for over thirty years. It was the little building which Edward Fitzgerald, the translator of Omar Khayyam, used to visit when he felt like instructing the children. Several of the old people in my book were educated there and after we had re-furnished it with all the things discovered in the East Suffolk Education Department's store at Ipswich, swept the chimney—full of jackdaws' nests—lit the fire in the massive Victorian grate and chalked 'Tuesday 3rd January 1900' on the blackboard, I thought of those neighbours of mine who had actually sat in this tall room and heard about the Boer War.

It was foolhardy, we realised later, to have begun filming Akenfield with a particularly elaborate and subtle scene involving seventy people, if one included such kind assistants as the Vicar's wife and the headmistress of the nearby primary school, but when we saw the results on a vast screen in a little cinema in Wardour Street, we were delighted that we took so bold a plunge. I think it was John Constable who said that 'a big canvas will tell you what you cannot do' and this first weekend of shooting, appropriately enough in Debach school, was a real education for everybody working on Akenfield. It did indeed tell us what we could not do in the circumstances of this unusual film, and this was never to go beyond the reality of what existed before our very eyes. The reality was the fun, the sadness, the poetry and the truth. And thus all the drama that we required.

The fun certainly came over in a big way—and accompanied by big-band music—when we held a 1943 village dance. Mr Arbon, who had blacked-out the hall for Hitler's war, blacked it out all over again for us. People of all ages, the Young Farmers' Club, farm workers and their families, teachers, every kind of person, danced to Glen Miller and the Inkspots, while the bombers from the nearby aerodrome (now the site of a vast mushroom factory) boomed overhead. Searchlights, sandbags, uniforms of the Suffolk Regiment, free beer from the Ipswich brewers whose wartime ads were mixed up with posters which said, 'Be like Dad, Keep Mum', and some drastic haircuts created the kind of nostalgia you could cut with a knife.

But the real test of filming Akenfield has been re-creating the old horse economy of Suffolk for the early scenes, finding those small fields of heavy clay, with their dense hedges, discovering workable forges which have not progressed from leather bellows to acetylene welding and, above all, searching out young farm workers who are able to do the old traditional crafts. We soon found out that the best way to do anything of this nature was not by appeals in the local press or on local television, although each of these mediums have given us the most generous help, but by good old bush telegraph. Not the least disturbance to my normally extremely quiet existence is the unknown voice on the telephone, full of Suffolk diffidence, saying, 'I hear you're looking for a man who can use a reaper...' Or giving me invaluable advice on costume, weather, hymns, pigs, stone-picking, battery chickens or just life itself as we aim to show it.

Perhaps our best scene, and certainly the one which most excites us, is the great harvest scene of about 1911, with the magnificent Suffolk waggons, the biggest in England, in the field and with heroic punches to draw them. We intend to cut two fields according to the old manner and have even arranged for them to be delightfully, if inefficiently, starred with poppies and scabious. We are praying for traditional harvest sun and moonshine so that we can capture something of those toiling idylls reflected in the Suffolk Photographic Survey, a wonderful collection of old pictures showing every facet of rural life in the county since the 1870s. The survey is the basis of our authority in such matters and I find it deeply moving to see these glimpses of Suffolk long ago brought into the present, as it were--principally by local faces. 'Hands last', said the blacksmith in my book. So do faces, of course. The youngster climbing out of his car, a bit awkwardly, for the old clothes are massive compared with jersey and jeans, takes the plough-reins and plunges off to the horizon behind delicately stepping shires, and, certainly for all the intents and purposes of our film, is his grandfather.

We have to shoot across the seasons, of course, so the making of the film is abnormally protracted. It is an enormous film, maybe two hours long and full of time and music, as well as work. Also love and death. Peter Hall calls it his home movie, thinking of his special involvement and of the weekend shooting schedules. In between filming, we all rush back to our 'normal' tasks, Peter to the National Theatre, the camera crew to various studios, the producer to cutting Pinter's The Home-coming, the designer, the make-up girls, wardrobe mistresses, and so on to a variety of professional quarters and myself to writing a book called The Art of the English Diary which makes a change. And our cast hurries back to keep half a dozen surrounding villages running.

If we succeed, we shall have challenged a lot of myths connected with the orthodox film industry, particularly those dealing with money. Our company, which we have registered as 'Angle Films', is really a co-operative from which nobody takes his usual professional fee until the film itself makes a profit. If its soul, or whatever, finally emerges into the un-common light of an East Anglian day, it will be due to the marvellous help of the country people themselves, who have been swift to recognise the special nature of the enterprise, and due a bit also to Peter Hall and myself coming from many generations of 'Suffolk'.

Home movie: The filming of Akenfield by Ronald Blythe. Reproduced here with the kind permission of both Ronald and The Countryman. First published in The Countryman, summer 1973.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Currently Reading

Ronald Blythe

AKENFIELD - PORTRAIT OF AN ENGLISH VILLAGE

0 notes

Link

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2023/jan/15/ronald-blythe-obituary

0 notes

Text

You know a (straight) ship is good when gay people who usually just prefer queer couples ship them too

Art by kasjophe on ig (the last one)

#lumax supremacy#lumax#lucas and max#lucas sinclair#max mayfield#stranger things#jim hopper#joyce byers#jopper#romione#ron weasley#ronald weasley#hermione granger#anne of green gables#anne with an e#gilbert blythe#anne shirly cuthbert#anne shirley#jily#jily supremacy#james potter#lily evans#marauders#marauders era#the marauders#fuck jkr#tangled#flynn rider#rapunzel#james fleamont potter

789 notes

·

View notes

Text

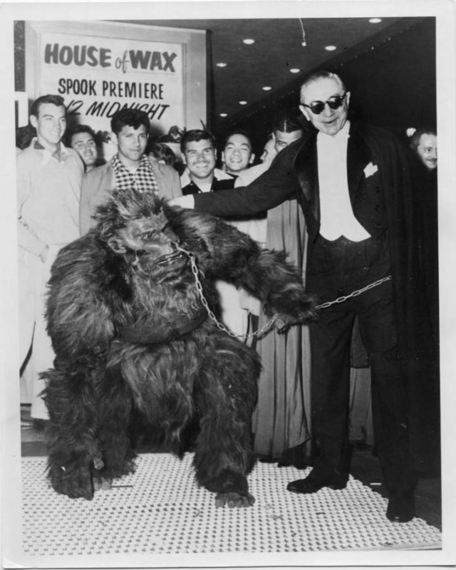

Bela Lugosi made an appearance at the premiere of the House of Wax at the Paramount Theater. He led actor Steve Calvert in a gorilla suit on a chain. His appearance was intended to promote publicity for The Atomic Monster, a proposed future role for Lugosi. The movie was eventually filmed by Ed Wood under the title of Bride of the Atom/Monster.

#Bela Lugosi#1953#Paramount Theater#House of Wax#Ronald Reagan#Ann Blyth#Richard Denning#Evelyn Ankers

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

MORE FUN FACTS ABOUT 1776 BECAUSE WHY NOT:

-William Duell stayed with the show the whole time it was on broadway and did not miss a single performance.

-previews were supposed to last longer on broadway, but it was cut short because on March 14th 1969 (55 years ago today) Howard Da Silva had a heart attack. The guys got him out of the theater and they revived him, they wanted to immediately take him to the hospital but he refused, and said he wanted to open the show, and then they could do with him as they pleased. So he opened the show with everybody, and then immediately as the curtain came down, an ambulance was waiting for him outside the theater and he got in, and he had surgery that night and was out of the show for MONTHS. Thank god they still had Rex Everhart from when the show was out of town because otherwise they would have been FUCKED. The cast did not have a party because of this whole incident. But unfortunately, the main three, Bill Daniels, Ken Howard and Howard da Silva, only did 5 shows together on broadway, Ken Howard would leave 3 months into the show, and the next time they’d all work together would be for the film.

-Howard Caine was “fired” by Jack Warner from the film because he kept complaining about the heat. When Peter Hunt found out about this, he went APE SHIT and got Caine back.

-there are many new actors for the 1776 film than original broadway cast themselves. Peter hunt got this all wrong. Yes, some of the original cast was there, but no everybody. The originals include David Ford, William Daniels, Howard Da Silva, Ken Howard, Ralston Hill, Emory Bass, Roy Poole, Ronald Holgate, William Duell, Virginia Vestoff, Jonathan Moore and Charles Rule. (John Cullum was in the Broadway production, but he didn’t originate Rutledge. Same with James Noble but he had been Hancock, not Witherspoon) the new actors include Donald Madden, Ray Middleton, Leo Leyden, William Hansen, Rex Robbins, Patrick Hines, Daniel Keyes, Howard Caine, John Myhers, Blythe Danner and Stephen Nathan. And also all the silent men in congress who don’t have any lines. So yeah, a LOT more new actors then OG cast members.

-when the broadway company went to do the show for Richard Nixon at the White House, the cast were persuaded to do it by the producers telling them they’d all get pay raises. That never ended up happening, and Bill Daniels was LIVID. They were lied to just to do a fucking show for Nixon, because 98% of the cast hated him. After that performance, Howard Da Silva joined an anti-war protest outside of the White House, still in full costume. He HATED Nixon with a PASSION because of his involvement of his blacklisting from Hollywood.

-Bill Daniels missed more performances than he thought he did. In his book, he mentions he only missed 2 shows out of his entire 2 year run. That isn’t true. Paul David-Richards, the OG Josiah Bartlett, understudied John Adams, and in his bio in the playbill, it says he went on at the very last second for Bill, and ended up doing 5 shows that week because Bill got sick. And Jonathan Moore also did one show as Adams.

-The cast referred to the song “Cool, Cool Considerate Men” as “Cool Conservative Men”

That’s it for now :)

13 notes

·

View notes

Note

please please PLEASE tell us what you think the easy boys' dnd classes would be! i agree with dick being a paladin and nix being a rogue 100% but i'd love to know what your take would be for everyone else!

Caveat: I'm not as well-versed at DND classes just yet (mostly because I haven't actually encountered a lot of them, and I've only ever played in 5E) so these are probably not the most creative of builds but I did my best! Also! These are classes, not DND races! Just assume everyone's a variant human... and also that everyone has the Soldier's background... Also don't come for me about which edition rules or game source I'm going by, we're playing it fast and loose, everyone.

I did say Dick was an Oath of Redemption Paladin-- mostly as a joke, because of the whole healing-Blythe's-combat-blindness thing. But now that I think about it, it doesn't really fit him very well. Something about Dick could drive him to be very vindictive, I think. He's definitely very petty. Story-wise, since he's so young in-show you can explain this away as a young Paladin picking a path and learning the ways and the discipline that comes with it... But he can also very well be Oath of Devotion Paladin, since Dick is very big on honor and duty. I also see him being Oath of Glory, mostly because something about Dick always strives to be the best, and that man has a lot of self-discipline.

You know who else is a Paladin? Ronald Speirs.

Listen. I know people would automatically think: oh, Ronald is a Rogue. And while that's what I think Ron would like to think of himself as (and maybe he multiclasses-- though I have no idea how that'd work), this bitch is a fucking Paladin through and through. Oath of Vengeance? maybe, but not quite. Oath of Conquest? oh, yes, that fits very well. Listen, a Paladin does not garner divine power from their Faith in their god-- that's a cleric. No, no, a Paladin garners divine power from their devotion. Try and look me in the eye and tell me Ronald Fucking Speirs wouldn't have the ability to divine smite someone simply because he has strong opinions about something. You can't. Did ya'll just forget *points at the interrogation scene in episode 10.* GIRL. He can multiclass, of course, but I feel like he's like. Locked the fuck in, ya know?

Or if you really wanna lean into the strange-and-off-putting vibe, we could borrow from Critical Role and he could definitely be a Blood Hunter. Ronald would be the kind to become a Blood Hunter. Order of the Lycan, because he's from DOG company, and I like to think I'm funny, but also that'd play excellently with both the almost animal-like way he moves and thinks + his care for easy as a whole (pack).

Ron could also be a monk. But I like him better when he has a weapon in his hands.

Lewis is a rogue though, and mostly because he's an Intelligence Officer, but also knowing his family background, it fits. I do love the idea of him being an Arcane Trickster, mostly because in my mind he could definitely multiclass as a Shadow Sorcerer (because let's be real, New Jersey would be the type of place to house a Shadow Sorcerer bloodline) because of his Nixon name + Charisma, which he has in spades. But only until like... level 3 or 4 because Lew would be the type to forgo magic-- since it's not something he can precisely control + it's his bloodline, so it's not like he worked for it-- to opt for something he can control and work toward perfecting. But another subclass he could fall under is Inquisitor Rogue. That's literally his job description.

Or Lew could be a College of Whispers Bard! That'd be fun, too, especially since Nix doesn't do much combat, but he would have a ton of Bardic Inspiration.

Wouldn't it be so funny if tiny Harry Welsh was a Path of Wild Magic Barbarian? I think it would be funny. Idk if it would fit, mostly because I think he's a Fighter, but it would be so funny.

David Webster, this bitch would be a College of Lore Bard for sure. But I did think for a bit that he might've been a School of Evocation or Order of Scribes Wizard (who multiclassed Bard), just for the high intelligence, low wisdom joke. It would be so funny if he was School of Evocation though-- can he cast spells? Yes? Gracefully and subtly and with finesse? Oh, gods no. He's a mess.

Web and George Luz are probably the only Bards in the whole company. George could be either College of Eloquence or College of Swords........ but if you want to up the angst potential, how about College of Spirits Bard? Oh, he watched his friends die in front of him? Let's make his survivor's guilt WORSE by making him have the ability to talk to ghosts!!

Shifty Powers, obvious. Ranger, of course, and in numerous subclasses, too. Though I did toy with the idea of him multiclassing as Arcane Archer, but then I figured that's more for Earl McClung, ya know (because, historically, he was a better shot than Shifty-- even Shifty says this)? The class in itself is fairly weak though, so I imagine Earl'd multiclass Arcane Archer (Fighter subclass) with a Ranger, though what kind of subclass is still up in the air for me, too. Truthfully, much like Shifty, he could be any, so take your pick. I'm partial to Horizon Stalker; but Hunter/Monster Hunter would be good, too. Also? Just imagine casting Arcane Shot on a gun instead of a bow-&-arrow. Magnificent.

Shifty and McClung could also be Circle of Land Druids, but then they wouldn't be as proficient in combat, so we'll stick with Ranger.

Eugene Roe could be a Life Domain Cleric, of course. But I feel like that's a bit too obvious. Grave Domain Cleric, maybe? Way of Mercy Monk sounds more appropriate for his character, since he's easily the kind of character to strive for inner spiritual balance, the way monks do-- let's just pretend he focuses more on healing than he does combat. Though both these classes do have the abilities to go on the offensive.

Ralph Spina strikes me as a non-magic user healer, though, so I think he'd be a Thief Rogue with a focus on the medicine skills + an extensive Healer's Kit, since thief rogues have like... more object interaction (I think?) per turn than anyone else. Though that would also fit Eugene, too, if you want non-magic user!Eugene, since he's often described as having a sixth-sense for when people need him, then appearing outta nowhere + the whole scissors thing. And the looting for supplies.

Carwood Lipton could go like... 3 ways. Fighter, Cleric, or Monk. I'm partial to him being a Light Domain Cleric, though, since that's the first thing that popped into my head. He could multiclass as Bard too, for the Bardic Inspiration, but idk, there are other subclasses that have the Suggestion spell in their back pocket, and he would use that extensively in Bastogne to keep morale up.

Malarkey is a Wild Magic Sorcerer. Mostly for the angst potential. Can you imagine him losing control of his magic when Skip and Penkala die? I know I shouldn't torture this man, but alas, it's just too good.

I also think Joe Liebgott would be a Divine Soul Sorcerer, though. That literally popped into my head first thing the second I saw this ask. He'd have some Healing Word by Level 2, and I think that works best for scenes like the one where Tab gets stabbed and also the one where he's comforting Tipper.

I can't shake the image of Artillerist Artificer Pat Christenson, Skip Muck, and Alex Penkala out of my head. They're on machine guns and the mortar rounds, respectively, so it fits for me.

......... an evil part of me wants Buck to be some sort of Warlock, he just hides it very well? But, again, that's mostly for angst potential. Realistically, he'd be a Fighter and/or a Barbarian. But a Warlock in the Military, though, wouldn't that be something? Of course the military would never allow it, because the Patron would take precedence above all else, but who says he can't hide that by claiming to multiclass as a Wizard? Idk how that would help in any way the plot, but the vibes are immaculate.

Everybody else, though, to me are either Artificers, Fighters, Barbarians, Clerics, or Monks, of course with multiclassing in between!

......... uh. yeah! that's it!

#ask#band of brothers#bob hcs#bob aus#thanks for this anon this was fun#and if anyone wants to fight me about it... don't do it. i cry easily

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

George Villiers 1st Duke of Buckingham in Fiction - a partial summary

CW: discussions of biphobia and homophobia in historical fiction and current historiography.

Feeling both inspired and outraged in equal measure by the upcoming Mary&George series, and having been fascinated with this remarkable man since forever, I have decided to post this partial overview of portrayals of George in fiction. The ones in bold are the ones I have read. Feel free to add to the list.

The Three Musketeers, Alexandre Dumas

The Honey and The Sting, Elizabeth Freemantle

My Queen My Love, E.M Vidal

Cavalier Queen, Fiona Mountain

The Dangerous Kingdom Of Love, Neil Blackmore

The Fallen Angel, Tracy Borman

Wife Of Great Buckingham, Hilda Lewis

Darling Of Kings, P J Womack

The Queens Dwarf, Ella March Chase

The Smallest Man, Frances Owen

The Spanish Match, Brennan Purcell

Captain Alatriste, Arturo Pérez-Reverte

The Cardinal and The Queen, Evelyn Anthony

Earthly Joys, Philippa Gregory

Myself My Enemy, Jean Plaidy

Charles The King, Evelyn Anthony

The Young And Lonely King, Jane Lane

The Fortunes Of Nigel, Walter Scott

The Crowned Lovers, E Barrington

The Minion, Raphael Sabiniti

The Murder In The Tower, Jean Plaidy

A Net For Small Fishes, Lucy Jago

The Arm and the Darkness, Taylor Caldwell

Les Gloires et les perils (?), Robert Merle

And a few I’m not so sure about where George is mentioned in passing: .

Viper Wine, Hermionie Eyre

John Saturnalls Feast, Lawrence Norfolk

Rebels and traitors, Lindsay Davis

The Assassin, Ronald Blythe

Some observations, in no particular order:

Novels set mostly in James reign often have George as a rival to Robert Carr and will attempt to foreshadow how much worse he will be compared to Carr.

The ones that feature Henrietta Maria as Protagonist or at least POV character, where George is normally a baddie trying to sabotage HM and Charles I's relationship, and his death is often portrayed as some sort of salvation for HM. In these books George will often be lamed for things which were IRL Charles's fault such as the expulsion of HMs French household in 1626.

Three Musketeers is practically a category in its own right due to all the film/tv adaptions but has had relatively few clones or imitators in English which is something of a surprise

George is only a protagonist in one of these books (Darling of Kings, P J Womack) in the rest he's a cameo or a villain

Rumours that I suspect authors know is nonsense are repeated verbatim such as Tracy Borman's baseless speculation about G offing the Manners brothers, king James, and his rumoured involvement with the occult.

Georges relationships with James and Charles respectively are mentioned but not meaningfully explored. neither are any other personal relationships he had.

The insights and shifts in terms of post 1970s revisionist and post revisionist scholarship esp. Roger Lockyer's bio of George have not found their way into any fiction set in this era. Georges capability as an administrator and manager of patronage is more often than not totally absent.

the general view of George and why he's often shown in such a negative light is pretty much "well, he was willing to god knows what with that dirty old man James; who knows what other depravities he was capable of" and its female authors who really seem to lean into this, which I find fascinating and disturbing.

EDIT (can’t believe I forgot this) George’s murder in 1628 is always the result of some sort of aristocratic conspiracy rather than the act of terrorism it was IRL. I do get why authors do this - the amount of world building and foreshadowing needed to make it seem plausible rather than random in universe. However making it the result of personal grudge rather than ideological violence detracts from why it was so shocking and important.

#Well this is longer than I intended#tedious drivel#CW biphobia#CW: Homophobia#george villiers#duke of buckingham#mary & george#mary and george#Charles I#James I#Henrietta Maria#I need something better to do with my time

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anne of the Island - Chapter XXVI

Enter Christine

The girls at Patty's Place were dressing for the reception which the Juniors were giving for the Seniors in February. Anne surveyed herself in the mirror of the blue room with girlish satisfaction. She had a particularly pretty gown on. Originally it had been only a simple little slip of cream silk with a chiffon overdress. But Phil had insisted on taking it home with her in the Christmas holidays and embroidering tiny rosebuds all over the chiffon. Phil's fingers were deft, and the result was a dress which was the envy of every Redmond girl. Even Allie Boone, whose frocks came from Paris, was wont to look with longing eyes on that rosebud concoction as Anne trailed up the main staircase at Redmond in it.

Anne was trying the effect of a white orchid in her hair. Roy Gardner had sent her white orchids for the reception, and she knew no other Redmond girl would have them that night -- when Phil came in with admiring gaze.

"Anne, this is certainly your night for looking handsome. Nine nights out of ten I can easily outshine you. The tenth you blossom out suddenly into something that eclipses me altogether. How do you manage it?"

"It's the dress, dear. Fine feathers."

"`Tisn't. The last evening you flamed out into beauty you wore your old blue flannel shirtwaist that Mrs. Lynde made you. If Roy hadn't already lost head and heart about you he certainly would tonight. But I don't like orchids on you, Anne. No; it isn't jealousy. Orchids don't seem to BELONG to you. They're too exotic -- too tropical -- too insolent. Don't put them in your hair, anyway."

"Well, I won't. I admit I'm not fond of orchids myself. I don't think they're related to me. Roy doesn't often send them -- he knows I like flowers I can live with. Orchids are only things you can visit with."

"Jonas sent me some dear pink rosebuds for the evening -- but -- he isn't coming himself. He said he had to lead a prayer-meeting in the slums! I don't believe he wanted to come. Anne, I'm horribly afraid Jonas doesn't really care anything about me. And I'm trying to decide whether I'll pine away and die, or go on and get my B.A. and be sensible and useful."

"You couldn't possibly be sensible and useful, Phil, so you'd better pine away and die," said Anne cruelly.

"Heartless Anne!"

"Silly Phil! You know quite well that Jonas loves you."

"But -- he won't TELL me so. And I can't MAKE him. He LOOKS it, I'll admit. But speak-to-me-only-with-thine-eyes isn't a really reliable reason for embroidering doilies and hemstitching tablecloths. I don't want to begin such work until I'm really engaged. It would be tempting Fate."

"Mr. Blake is afraid to ask you to marry him, Phil. He is poor and can't offer you a home such as you've always had. You know that is the only reason he hasn't spoken long ago."

"I suppose so," agreed Phil dolefully. "Well" -- brightening up -- "if he WON'T ask me to marry him I'll ask him, that's all. So it's bound to come right. I won't worry. By the way, Gilbert Blythe is going about constantly with Christine Stuart. Did you know?"

Anne was trying to fasten a little gold chain about her throat. She suddenly found the clasp difficult to manage. WHAT was the matter with it -- or with her fingers?

"No," she said carelessly." Who is Christine Stuart?"

"Ronald Stuart's sister. She's in Kingsport this winter studying music. I haven't seen her, but they say she's very pretty and that Gilbert is quite crazy over her. How angry I was when you refused Gilbert, Anne. But Roy Gardner was foreordained for you. I can see that now. You were right, after all."

Anne did not blush, as she usually did when the girls assumed that her eventual marriage to Roy Gardner was a settled thing. All at once she felt rather dull. Phil's chatter seemed trivial and the reception a bore. She boxed poor Rusty's ears.

"Get off that cushion instantly, you cat, you! Why don't you stay down where you belong?"

Anne picked up her orchids and went downstairs, where Aunt Jamesina was presiding over a row of coats hung before the fire to warm. Roy Gardner was waiting for Anne and teasing the Sarah-cat while he waited. The Sarah-cat did not approve of him. She always turned her back on him. But everybody else at Patty's Place liked him very much. Aunt Jamesina, carried away by his unfailing and deferential courtesy, and the pleading tones of his delightful voice, declared he was the nicest young man she ever knew, and that Anne was a very fortunate girl. Such remarks made Anne restive. Roy's wooing had certainly been as romantic as girlish heart could desire, but -- she wished Aunt Jamesina and the girls would not take things so for granted. When Roy murmured a poetical compliment as he helped her on with her coat, she did not blush and thrill as usual; and he found her rather silent in their brief walk to Redmond. He thought she looked a little pale when she came out of the coeds' dressing room; but as they entered the reception room her color and sparkle suddenly returned to her. She turned to Roy with her gayest expression. He smiled back at her with what Phil called "his deep, black, velvety smile." Yet she really did not see Roy at all. She was acutely conscious that Gilbert was standing under the palms just across the room talking to a girl who must be Christine Stuart.

She was very handsome, in the stately style destined to become rather massive in middle life. A tall girl, with large dark-blue eyes, ivory outlines, and a gloss of darkness on her smooth hair.

"She looks just as I've always wanted to look," thought Anne miserably. "Rose-leaf complexion -- starry violet eyes -- raven hair -- yes, she has them all. It's a wonder her name isn't Cordelia Fitzgerald into the bargain! But I don't believe her figure is as good as mine, and her nose certainly isn't."

Anne felt a little comforted by this conclusion.

#anne of the island#anne of green gables#anne shirley#philippa gordon#christine stuart#gilbert blythe#quotes

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Excerpt from Ronald Hutton’s Station’s of the Sun:

During the early modern period, information upon harvesting increases, and most of it is summed up in three different sets of verses, spread across the span between 1570 and 1650. The earliest is Thomas Tusser’s famous rhyming treatise on farming, the first edition of which appeared in 1573. He described how a good employer gave gloves to his field-hands, how the latter cried for ‘largesse’, and how a “harvest lord” was appointed to lead and supervise the work. Tusser attached expecial importance to the food and drink given during the reaping and the entertainment at the end:

In harvest time, harvest folke,

servants and all,

should make all togither good

cheere in the hall:

And fill out the black boule of

bleith to their song

and let them be merie all harvest

time long.

Once ended thy harvest, let none

be begilde,

please such as did helpe thee, man,

woman and childe.

Thus dooing, with alway such

helpe as they can,

thou winnest the praise of the

labouring man.

He added that on the departure each “ploughman” should be presented with a “harvest home goose”.

The author of the late Elizabethan ballade “The Mery Life of the Countriman”, which has been much quoted earlier in this book, was as concerned to celebrate the process as Tusser was to give practical advice upon it:

When corne is ripe, with tabor and

pipe, their sickles they prepare;

and wagers they lay how muche in a

day they meane to cut downe there.

And he that is quickest, and cutteth

downe cleanest the corne,

a garlande trime they make for him,

and bravely they bringe hime home.

And when in the barne, without any

harme, they have laid up their corne,

In hart they singe high praises to him

that so increast their gaine.

And unto the parson, their pastor,

and teacher also,

With harts most blyth, they give their

tyth--their duties full well they knowe.

The standpoint of this writer, detached, external, and preoccupied with hierarchy and obligation was occupied in the early seventeenth century by a genuine poet, in a famous piece of literature. Robert Herrick’s “The Hock-cart, or Harvest home”, was pointedly dedicated to an earl and so concerned with the dues to a secular lord rather than to a clergyman. It depicts the cart carrying the last load from the fields, “dressed up with all the country art”, and followed by adults crowned with ears of corn and a whooping “rout of rural younglings”. A piper accompanies a harvest-home song. “Some bless the cart, some kisss the sheaves; some prank them up with oaken leaves”. the landowner has prepared a feast at his seat for them, of beef, mutton, veal, bacon, custard pies, boiled wheat and beer. The peopldrink first to his health, and then to “maids with wheaten hats” and to a succession of agricultural tools. The poem ends with a homily in favour of social deference and against drunkenness at the feast.

21 notes

·

View notes

Photo

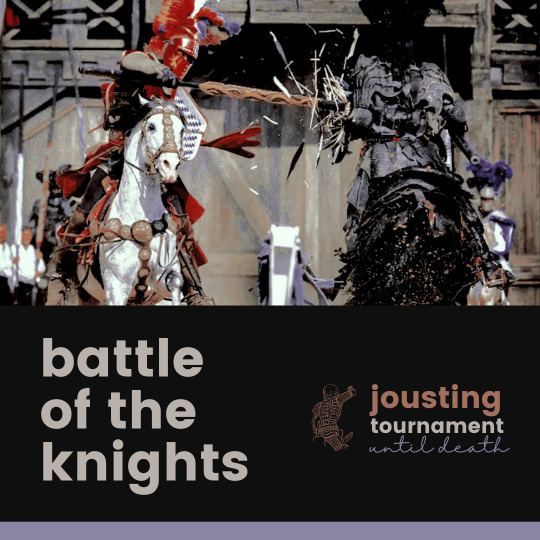

the list of competitors is nailed to the walls outside the arena . it goes as follows :

tommen lannister , aeron dayne , daemon targaryen , cassian lannister , rohan stark , aster tyrell , stefan baratheon , aegon targaryen , emir stark , blythe martell , sila targaryen , olyvar tyrell , colton coldwater , godric brune , braxton brax , xenophilius flint , gregory buckler , ronald ambrose .

the tournament begins with the presentation of the knights , and the competitors ride in in full house colours - draped in the finest armour that might protect them . the announcer calls them forth , and they begin to ask for their favours .

prince aegon requests the favour of his wife , princess daella , referring to her as his true queen . / accepted .

prince daemon , requests the favour of lady shaera - telling her it will be the first of many crowns . / accepted .

lord tommen requests the favour of his bastard child , whose mother - the lady nymeria - accepts on her behalf , leading to many mumbles of distaste within the crowd . / accepted .

lord theodore asks lady karina for her favour , confessing for all eyes to see that she brings light to his darkness . / accepted .

princess blythe asks the lady talia for her favour to commemorate their paths crossing once more . / accepted .

lord stefan , to the distaste of many , asks the lady emmelyne for her favour - claiming he can at long last wear it unhidden . / accepted .

lord olyvar , to the surprise of the crowd , asks for the favour of the widowed lady evelyn , stating he will do all he must to be a better man deserving of her . / accepted .

lord rohan makes his request to the lady poppy , declaring that he would have her as his lady wife of winterfell to the awe of the crowd . / accepted .

lord aster asks the widowed princess aerea , stating he does it so honour her dearly departed husband . / accepted .

when it comes time for lord cassian to request a favour , many believe he might choose a woman of the court at random - looking to gain both her favour and her heart - if not his betrothed , but none could have expected him to ride to the targaryen’s stand , eyes twinkling . it is the favour of the queen that he requests , to the shock of the crowds . / accepted .

princess sila asks the lady dilara for her favour when lord cassian does not , bringing murmurs throughout the crowd once more . / accepted .

the lord aeron requests the favour of his betrothed , lady elif , with sweet words and an endearing smile . / accepted .

lord colton coldwater requests the favour of the lady dyanna on her late brother's hehalf , claiming he wishes to fight for his memory . / accepted .

lord godric brune asks for the lady aemma's favour , claims of the targaryens it is a pity the most lovely is the one without a title . / accepted .

lord braxton brax asks for the favour of the lady genna - claiming it is such a pity his liege lady is without champion at such an age . / refused , insulted him publicly .

lord xenophilius flint requests the favour of who he considers the true lady of the north - emel hightower - claiming his loyalty is with her always . / accepted .

lord gregory buckler pleads for the favour of the newly single lady jeyne , claming he will gladly fight for her when the one who should have done will not - requests that if he win he may be granted her first dance at the feast . / accepted .

lord ronald ambrose , shy as ever , requests the favour of the lady alysane - confessing to having watched her as her loveliness has only grown . / accepted .

disappointment and excitement reign within the audience , as many ladies of the court tucked away their own favours - made with love . still , as the first day of competitors is announced - their cheers are loud .

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Child in the Country,

Colin Ward

English literature abounds in the kind of autobiographical novel in whose opening chapters our young hero (for it is seldom a heroine) is seen in the ancient small-town grammar school, daydreaming of the woods and fields, while his elderly teacher is droning on about Latin declensions.

Once let out of school, his real life begins – wandering by the river banks and up through spinney and copse to the hilltops, observing nature with a learning eye and absorbing the wisdom of shepherd and gamekeeper, forester and farrier, from the lovable old poacher with a heart of gold and from the scary old hermit whose tumbledown cottage is really a treasure trove of country lore and bygones.

In the urban equivalent our hero is rather lower down the social scale. Once released from his stern mentors in the board school, he is out and down the street like a shot, everybody’s friend in the market, besieging the old lady in the sweetshop on the corner, begging orange boxes from the greengrocer, nicking coal from the railway yard, all as a rough-and-ready apprenticeship to the life of the city. Years later (for such stories are always set in the past) these stereotypes have become successful citizens, and when they unbend to the young graduate seeking the hand of their favourite daughter, they usually confess that, ‘I was educated in the School of Life’, The point that they and their creators are making is the truism that our homespun philosophers invariably call it, is no substitute for Life Itself. The stereotypes are, of course, intensely literary in origin. The first owes a great deal to Wordsworth and his immense influence on the British imagination, with the long shadow of Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s cult of the ‘natural man’ behind it, and the second belongs to a picaresque tradition stretching back through Dickens to Defoe. Teachers of English have for years sought to democratize and update these stereotypes of the separateness of urban and rural experience. Think of the whole series of excellent books with which vast numbers of children have been made familiar as they became set books for examination purposes. I am thinking of texts like Flora Thompson’s evocation of Victorian rural childhood in Lark Rise, Alison Uttley’s Edwadian The Country Child, Laurie Lee’s idyll of the years after the First World War, Cider With Rosie, and Ronald Blythe’s assemblage of his neighbours‘ recollections in Akenfield. Excellent books, all of them, in their examination of the relationship between children and their environment, but I often wonder if their popularity among teachers is precisely because they promote a picture of a purified identity of rural childhood, uncontaminated by urban influences which muddy and confuse the image. In exactly the same way, travellers returning from Polynesia report that secondary school pupils there are obliged to read Margaret Mead’s Growing Up in New Guinea and Coming of Age in Samoa, the fruit of her research in the nineteen-thirties, to learn about the world they have lost.

Read

0 notes

Text

2023 In Memoriam Part 3

Col. Dr. Harriet Hall, 77

Bob Harrison, 92

Charles Kimbrough, 86

Lisa Presley, 54

Robbie Bachman, 69

Lt. Col. Harold Brown, 98

Lee Tinsley, 53

Robbie Knievel; Jr., 60

Julian Sands, 65

Madeleine Attal, 101

Country Boy Eddie, 92

Bill Davis, 80

(James) Yoshio Yoda, 88

Carl Hahn, 96

Ronald Blythe, 100

Wally Campodonico aka Wally Campo, 99

Juhann Af Grann, 78

Devin Willock, 20

Chandler Lecroy, 24

(Wayne) Gino Odjick, 52

Ted Savage; Jr., 85

Ed Beard, 83

George McLeod, 92

Dr. Lloyd Morrisett, 93

Ruslan Otverchenko, 33

Frank Thomas, 93

Luigia Lollobrigida, 95

Brian Perry, 78

Sister André, 118

Chris Ford, 74

Bishop John Bura, 78

#Religion#Tributes#Celebrities#Planes#Missouri#Washington#Sports#Baseball#Indiana#Movies#TV Shows#Minnesota#Music#Tennessee#Canada#Manitoba#British Columbia#Ohio#Kentucky#Arizona#Montana#Nevada#U.K.#France#Alabama#Japan#Cars#Germany#Books#Finland

0 notes