#Raffaello Baldini

Text

- Raffaello Baldini

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

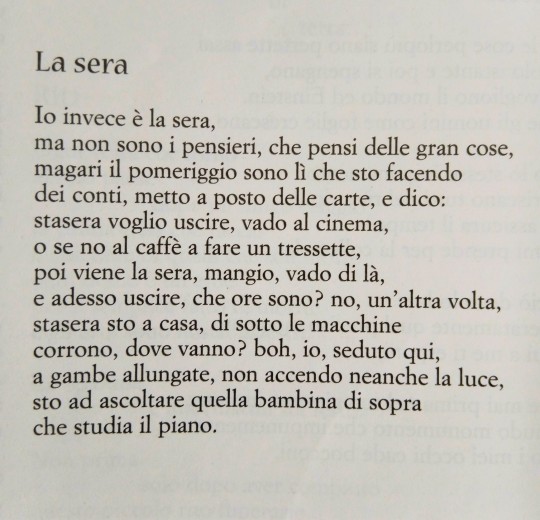

POETI

Raffaello Baldini ( 1924 - 2005 )

Le sue poesie sono vere e proprie narrazioni, immagini, in versi, spesso così taglienti da far male.

I personaggi sono coloro che non avrebbero mai voce, popolari, a volte fino al grottesco. Soli. Insoliti. Di una solitudine che si esprime in monologhi chiusi, di un’umanità spesso sghemba.

Frammenti di vite, ritratti in versi, spesso visionari, a volte struggenti.

Una su tutti, la mia preferita: in un dialetto che è il mio - il Romagnolo - (ma non è il mio, per una questione di suono, perchè ogni zona, in Romagna, ha pronunce e accenti diversi, oltre a differenti varianti della stessa parola) e che comprendo ma non saprei replicare con le stesse sonorità ma con le mie, [dialetto cesenate].

LA MAESTRA DI SANT'ERMETE

La mèstra ad Sant’Ermèid

dal vólti, e’ dopmezdè,

la s céud tla cambra e la zènd

una Giubek. La n fómma.

Stuglèda sòura e’ lèt

la guèrda ch’la s cunsómma.

U i pis l’udòur.

Dal vólti u i vén da pianz.

Traduzione:

La maestra di Sant’Ermete

delle volte, il pomeriggio,

si chiude in camera e accende

una Giubek. Non fuma.

Sdraiata sul letto

la guarda consumarsi.

Le piace l’odore.

Delle volte le viene da piangere.

(Raffaello Baldini, in La Nàiva Furistír Ciacri, Torino, Einaudi 2000, p. 14)

Quante volte ho immaginato quella sigaretta

Una sigaretta, come la solitudine, come la vita che consuma... che si consuma.

Amo questo tipo di poesia asciutta.

Che dice, che sa raccontare, che ti regala una storia a partire da una immagine.

A volte, con una sequenza di immagini che hanno la grazia dell’essenziale.

Come le fotografie.

Come una Mostra Fotografica.

Silenziosa sì,

ma che sa raccontare storie.

.

.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

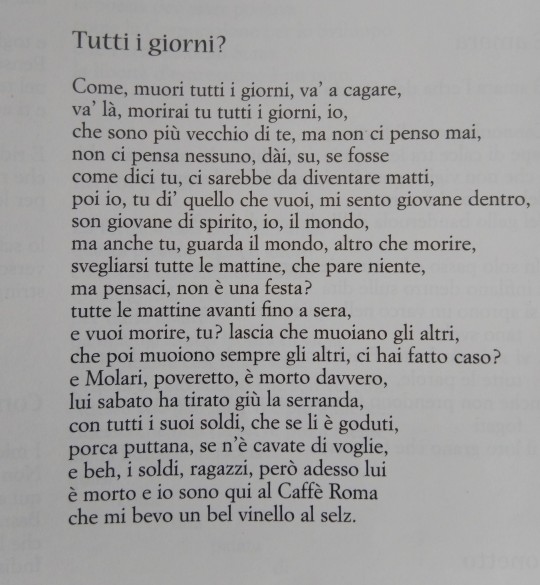

Il mondo

Secondo me si potrebbe, essere tanti, ma tanti, diciamo | che ci sono stati degli sbagli, la prima volta, si sa, | che non ne ha colpa nessuno, è andata così, | e ricominciare tutto da capo.

E’ mònd

Sgònd mè u s putrébb, ès ‘na gran mass, a gémm | ch’u i è stè di sbai, la préima vólta, u s sa, | ch’u n n’à còulpa niséun, la è ‘ndèda acsè, | e ‘rcminzé tótt da capo.

(Raffaello Baldini)

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

STAVO GUARDANDO IL PASSATO

Gli attrezzi del nonno sono ancora tutti lì, protetti dalle ragnatele non li tocca nessuno. Ogni cosa è al proprio posto: in un angolo del garage, sul piano da lavoro, dentro ai cassetti incrostati d’olio.

C’è un barattolo di chiodi in bilico su una mensola, un fusto di vernice a terra, una piccola morsa in ghisa agganciata al tavolo, una sega a telaio in legno di faggio appesa alla parete come una minaccia. Da quel che so, è sempre stata lì, saldata all’eternità. A terra i trucioli di ferro e polvere scompaiono sotto una vecchia credenza. Lì accanto c’è un armadio sfondo, pieno di cappotti e naftalina. Tra 5 miliardi di anni, quando il sole si espanderà al punto da annientare ogni forma di vita, tutto ciò che è esistito non esisterà più, compresi i ricordi. Moriremo tutti e lo sapremo con 8 minuti di ritardo. È questo il tempo che impiega la luce per arrivare dal Sole alla Terra. Vivremo 8 minuti senza sapere di essere già morti. Quando guardiamo le stelle stiamo guardando il passato. Quando nonno Dino anneriva una lastra di vetro con una fiamma per permettermi, da bambino, di guardare un’eclissi di Sole, stavo guardando il passato. In base alla distanza da qualcosa o da qualcuno, tutto ciò che vediamo è già successo, magari qualche nanosecondo prima, ma è già successo. Quando nonna Elena è morta sul letto, era già successo. Il presente non esiste. L’unico modo per fermare il tempo è scattare una foto. Ne ho una di Elena e Dino sul mobile della TV. Sono in vacanza sulle Dolomiti. Nonno indossa un giubbotto di pelle nera e un maglione blu. Nonna ha una lunga gonna rossa e un golfino grigio. Non mi ero mai reso conto di quanto la foto fosse gialla. Una mattina ti alzi, la guardi: è gialla. È un processo d’invecchiamento talmente lento che sembra immediato. Un po’ come i ricordi. Quando muore una persona abbiamo sempre paura di dimenticarne la voce e il volto. Ma spesso tornano senza cercarli. Come il profumo della ragazza con cui stavi al Liceo, non lo senti per anni poi appare come uno schiaffo e riapre cassetti e meraviglie. Ci sono cose che saranno belle per l’eternità, come le carezze dei nonni o le loro parole, dette in una lingua tutta loro. Ci sono cose, diceva Raffaello Baldini, che succedono solo in dialetto. Per questo, quando Elena parlava nella sua lingua, ogni cosa prendeva colore e acquistava senso. In dialetto le cose erano più vere.

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

ZITTI TUTTI!

written by Raffaello Baldini

with Denis Campitelli

directed by Alberto Grilli

scenes and costumes

Maria Donata Papadia and Angela Pezzi

lights Marcello D'Agostino

production Teatro Due Mondi

with the support of the Emilia-Romagna Region

•

First studio of “Zitti tutti!”

A tribute to the poet and writer Raffaello Baldini. The theater show was written in Romagna dialect by Baldini in 1993, for the first time as the playwright for Ivano Marescotti.

... It's a monologue that changed the way Campitelli sees and hears the Romagna language, creating literature for the stage that was previously non-existent.

The main man lives while he speaks, but his words soon become the soul of an empty reality. When the flow starts, the mind and heart explode with loneliness and words choke in their throat, they can only react by screaming desperately: Everybody shut up! (Zitti tutti!)

0 notes

Text

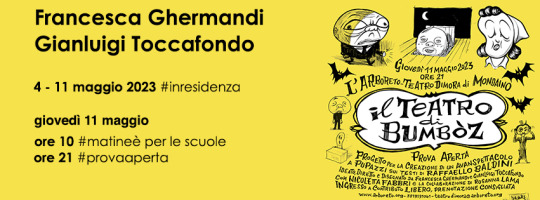

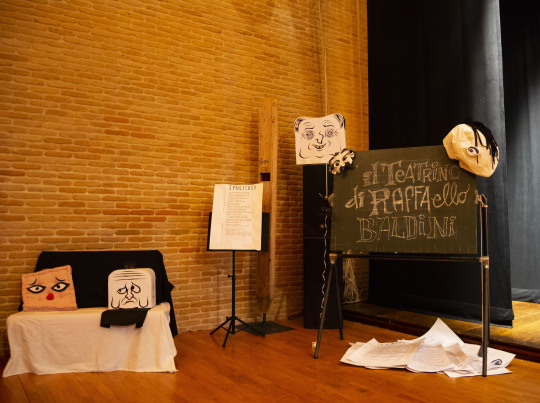

Ghermandi/Toccafondo in residenza per “Il Teatro di Bumbòz”

04 Maggio 2023 - 11 Maggio 2023

Inizia oggi la residenza creativa per la ricerca e la composizione del nuovo spettacolo di Francesca Ghermandi, Gianluigi Toccafondo, Nicoletta Fabbri e Rosanna Lama.

Durante la notte in un deposito abbandonato vagano pipistrelli e fantasmi. La loro danza è improvvisamente interrotta dall’arrivo del guardiano, un tipo strampalato che non riuscendo a cacciarli, capisce che l’unica maniera per rabbonirli è parlare con loro e rispondere a una telefonata dall’aldilà. Tutti vogliono dire qualcosa, ma non sembrano cattivi, solo un po’ logorroici: tra questi c’è il freddoloso, il lurido che vive in un bidone, la donna perennemente indecisa che racconta di un passato amore, il vecchio che scrive ai ladri perché non sa cosa gli hanno rubato, il giocatore che non riesce a fare il solitario con le carte del bar, buone solo a farci il brodo e tanti altri, che compaiono e scompaiono. Sotto gli occhi del guardiano prende vita lo scatenato teatrino di ‘bumbòz’, pupazzi scappati fuori dalle pagine di Raffaello Baldini.

**************************************************************************

Francesca Ghermandi è una fumettista. Le sue storie e i suoi disegni sono stati pubblicati da riviste italiane e straniere a partire dalla metà degli anni ’80. Ha pubblicato diversi libri a fumetti e illustrati tra cui Pasticca, ed. Einaudi; The Wipeout, Fantagraphics Books; Hiawata Pete, Grenuord, Coconino Press; Un’estate a Tombstone, Comix-Panini; Le Avventure di Ulisse di R. Piumini, Mondadori. Ha realizzato le scene animate dello spettacolo Mon Jour di Silvia Gribaudi.

Gianluigi Toccafondo è nato a San Marino nel 1965, ha studiato all’Istituto d’Arte di Urbino, vive a Bologna. Dal 1989 realizza cortometraggi di animazione con ARTE France, pubblicità negli Stati Uniti e Giappone, sigle per la televisione italiana e per la 56a Mostra d’arte cinematografica, loghi animati come Scott free, Fandango; è stato l’aiuto regista di Matteo Garrone per il film Gomorra e ha disegnato i titoli animati per il film Robin Hood di Ridley Scott. Per l’Opera lirica ha realizzato scene, video e costumi per Opera camion, Teatro dell’Opera di Roma.

0 notes

Text

Ivano Marescotti legge Raffaello Baldini (Che ora è?)

Dà i numeri del lotto il Campanile della Chiesa? Prima le due e mezzo, adesso suona le dieci, il mio fa le tre, è fermo, e la sveglia, figurarsi, segna le undici, si dev’essere scaricata la pila, aspetta, che di sopra hanno potato il pioppo, si vede fino al Torriazzo, questa è bella, fa mezzogiorno, sono diventati tutti matti gli orologi? “Caterina, che ore sono?”, “Non lo so mica, mi sono…

youtube

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

DESIGN THINKING///WEEK3///WHAT SHOULD DESIGNERS KNOW ? - II

From this point of view, which has its roots in the idea of “cultura del progetto” [design culture] from the Italian design tradition,... * 7 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------*7! “Cultura del progetto” is translated in English as “design culture,” but it must be considered that, in Italian, the term “progetto” has a deeper and more complex meaning than the one normally given to the English term “design.” See also: Andrea Branzi, Weak and Diffuse Modernity: The World of Projectsat the Beginning of the 21st Century(Milano: Skira, 2008); and Andrea Branzi, Introduzione al design italiano [Introduction to Italian Design] (Milano: Baldini & Castoldi, 1999).

...design culture can be defined as the “meaningful con- text” in which a new project is conceived and developed and in which new meanings are produced—meanings that, in some cases, can influence the very culture from which they grew. In reference to this meaningful context, when Julier talks about design culture as agency, he says that “... it takes context as circumstance but not as a given: the world can be changed through a new kind of design culture.” *8 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------*8! Julier, “From Visual Culture to Design Culture,” 71.

An Emerging Design Culture?

Given its origins and nature, design culture is not a single unit; in fact, we should speak of it as a plural entity that includes as many different cultures as there are arenas in which the question of design is investigated and discussed. Nevertheless, in certain places and moments converging factors create the conditions for particularly clear and recognizable meaningful contexts to emerge. This convergence enables us to talk about the European design cul- ture at the beginning of the past century, or American design cul- ture in the 1930s, Scandinavian design culture in the 1950s, or Italian design culture in the 1980s. Conversely, but for the same reason, talking about the culture of emerging design is difficult. In the following paragraphs we examine why.

Every design project (just like any human activity or prod- uct) exists both in a physical-biological world—where human beings live and artifacts are produced and function—and a socio- cultural world—where human beings interact through language and things assume meaning.*9 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------*9! Humbert R. Maturana, Francisco J. Varela, Autopoiesis and Cognition:

The Realization of the Living (Dordrecht, NDL: Reidel Publishing, 1980); Herbert R. Maturana, The Biological Foundations of Self-Consciousness and the Physical Domain of Existence (Milano: Raffaello Cortina, 1993).

Thus, describing a project by talking about its way of tackling and resolving a problem (i.e., describing it as a solution) means observing it in the first world. Conversely, describing the culture it emerged from, the quality criteria it adopts, and the meanings it carries means considering it in the sec- ond world. Therefore, every human activity and everything we produce always lives in both these worlds, even when one of these lives may not be evident.

Up to now, the life of artifacts in the socio-cultural world appears clear, and can easily become an object of discussion when we refer to material artifacts, whether armchair or washing machine, house or city: We have a language to talk about these artifacts’ meanings (because over time they have been socially constructed); we have quality criteria by which to judge them; and we have cultural references with which to compare them.

We cannot say the same of emerging design and its results. This is so for two reasons: First, the urgency and extent of the problems to be tackled drive us to a pragmatism that in the name of efficacy leaves no time for critical and cultural

reflection. Second, in emerging design, project results are complex, hybrid, dynamic entities, and we do not yet have language for talking about them, history to compare them with, or until now, arenas in which to discuss them. Consequently, recog- nizing the design culture from which they are emerging and which they are expressing is no easy matter. Therefore, the conver- sation tends to deflate into narrowly solution-oriented discourse— a mere narration of the techniques used and the effectiveness of its results, suggesting that this field is the only one on which discus- sion is possible.

It must be added that, in this same solution-oriented dis- course, some cultural issues do appear too: The more human-cen- tered is the problem, the more participative is the process of resolving it and the more socially innovative is the solution the more the cultural dimension of the problems tackled and the solu- tions found must be investigated in depth to understand people’s needs, their capabilities and motivations, and the social dynamics in which they are living. However, while this solution-oriented culture is indispensable in getting a clear focus on the problems and on stakeholder capabilities and motivations, it does not lead us to propose new qualities. It does not enable us to say how we can create a world that is richer in opportunities, more interesting, and, ultimately, more attractive.

Solution-ism and Participation-ism If the discussion on emerging design focuses mainly in its func- tioning, it goes without saying that the technological, economic and managerial dimensions must play a central role in it, and that the necessary cultural contributions are also orientated in this direction. On the other hand, since as we said no human action can be free of the sense system it exists in, these solution-orien- tated technical and cultural actions also have a meaning, they emerge from and propose a design culture. In our case, the culture of today’s emerging design comes over as a tangle of solution-ismand participation-ism. Solution-ism. By this expression, which I have taken from Eugeny Morozov, though without necessarily sharing all that this author attributes to it, I mean a culture that starts from an approach that is in my view totally correct, reducing it to a reductive ideology that leads us, as Morozov writes, to recast “all complex social situations either as neatly defined problems with definite, computable solutions or as transparent and self-evident processes that can be easily optimized.” *10 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------*10! 10 Ibid., 5.

In my view, the correct initial approach is the one stating that the complexity of the world, and therefore of the problems it poses, should be tackled by identifying a multiplicity of less complex, smaller scale sub-issues. This approach, which comes from theoretical reflection on complex systems and from the prac- tical experience of social innovation, leads to the recognition that a big, complex problem should be tackled not by looking for a single, big, complex, unitary solution but by spreading the complexity over the various nodes in the system: “Rather than trying to control complexity through top down command-and-control hierarchies,” writes Josephine Green, “social innovation shows us how to embrace complexity.” *11 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------* 11! Josephine Green, Beyond20:21st Century Stories, http://www.growthintransition. eu/wp-content/uploads/Green-A-new- narrative.pdf (accessed December 2014).

It does so by developing local initiatives in which those directly affected—that is, those who know the prob- lem best and from close up—are directly involved. Given that, it must be observed that these solutions do not constitute the only terrain for action. Other kinds of design projects exist that are capable of integrating a multiplicity of local projects. For example, “planning by projects” and “acupunctural planning,”*12 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------*12! Ezio Manzini and Francesca Rizzo, “Small Projects/Large Changes: Participatory Design as an Open Participated Process,” CoDesign 7, 3-4 (2011): 199–215; Lou Yongqi, Francesca Valsecchi, and Clarisa Diaz, Design Harvest: An Acupunctural Design Approach Towards Sustainability (Gothenburg, Sweden: Mistra Urban Futures Publication, 2013), 202; Che Tarn Biggs, Chris Ryan, and John Wisman, “Distributed Systems: A Design Model for Sustainable and Resilient Infrastruc- ture,” VEIL Distributed Systems Briefing Paper N3 (Melbourne: University of Mel- bourne, 2010).

link up different local projects and different scales of inter- vention, and in doing so, have the power to influence and transform large institutions and entire territorial systems.

In addition, other design activities contribute to producing a more favorable environment for the birth and development of a multiplicity of other projects, even though they do not con- tribute directly and immediately to the solution of a specific prob- lem. For example, this group includes design initiatives that produce infrastructure, standards, and regulations; knowledge; visions; and shared values that together can increase the proba- bility that new solutions will emerge and can help them develop in greater synergy.

Therefore, if the first limit of solution-ism is in not taking account of all these possibilities, its second limit is in proposing to find solutions concentrating only on the way they function, on their economies, and on their practical results, while leaving in the shadows the critical discussion of their meaning and the qualities sought and produced. This lack of a deep cultural discourse can be found at all scales: from motivating the participation of the various stakeholders in local solutions, to feeding the broadest of social conversations about the future.*13 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------*13! In this sense, solution-ism can be seen as an updated vision of functionalism— functionalism in a world where what is designed consists not only of products but also of product networks, services, and communication. Participation-ism. Participation-ism is a sort of cultural aphonia that induces design experts to refrain from expressing themselves. In this case, too, the departure point is an extremely important idea: the recognition that every design process is co-design, and that it therefore must provide space for the point of views and active par- ticipation of many different actors. However, this original good idea has developed into an ideology that also is limited and limit- ing. In its adoption in co-design processes, the design expert’s role is reduced to a narrow, administrative activity, where creative ideas and design culture tend to disappear. Design experts take a step backward and consider their role simply as that of “process facilitators,” asking other actors for their opinions and wishes, writing them on small pieces of paper, and sticking them on the wall and then synthesizing them, following a more or less formal- ized process. We can call the results of this way of thinking and doing “post-it design.”

The problem is that, in moving from the intention of giving voice and an active role to different stakeholders, participation-ism and post-it design end up transforming design experts into admin- istrative actors with no specific contributions to bring—other than aiding the process with their post-its (and, maybe at the end, with some pleasing visualizations). In other words, in the participation- ism perspective, the design process is reduced to a polite conversa- tion around the tables, as stakeholders undertake some participatory design exercises. On the contrary, in my view, the social conversation on which the co-design process is based is much more complex than a participatory design exercise, and it requires design experts to be much more than administrative facil- itators and visualizers.

Design Culture and Dialogic Design Co-design is a complex, contradictory, sometimes antagonistic pro- cess,...*14 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------*14! See the works cited in note 3, as well

as Carl DiSalvo, Adversarial Design (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2012);

and Erling Björgvinsson, Pelle Ehn, and Per-Anders Hillgren, “Agonistic Participa- tory Design: Working with Marginalised Social Movements,” CoDesign: Interna- tional Journal of CoCreation in Design and the Arts 8, no. 2-3 (2012): 127–44. ...in which different stakeholders (design experts included) bring their specific skills and their culture. It is a social conversa- tion in which everybody is allowed to bring ideas and take action, even though these ideas and actions could, at times, generate prob- lems and tensions. As a result, what makes a dialogic conversation in a design process is that the involved actors are willing and able to listen to each other, to change their minds, and to converge toward a common view; in this way, some practical outcomes can be collaboratively obtained. In short, these involved actors are will- ing and able to establish a dialogic cooperation—a conversation in which listening is as important as speaking.*15 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------*15! Richard Sennet, Together: The Rituals, Pleasures and Politics of Cooperation (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012). It comes that, in the dialogic design framework, the design experts’ capability to listen is a crucial one (and, of course, it is a particularly difficult one for those who are still bound to the past century’s tradition of “big-ego design”*16). ------------------------------------------------------------------------------*16! The big-ego design is left over from the last century’s demiurgic vision, in which design is the act of particularly gifted individuals capable of imprinting their personal stamp on artifactsand environments. Even though this perspective may still mean something in some very specific design fields, this way of thinking and doing becomes highly dangerous when applied to complex social problems. Nevertheless, it is also clear that, at the end of the day, the quality of the results largely depends on the quality of the ideas that come up in discussion. Therefore, to adopt a dialogic approach, design experts must learn to listen, but they must also learn to propose their own ideas and visions. And to do it in the most appropriate way. The obvious precondition for being able to do so is that these ideas, values, and visions exist. That is, that a design culture capable to generate and cultivate them exists. And here we have reached a crucial point: If, as we said, the emerging design culture is still weak and reductive, how can it be strengthened and

enriched? Where might we find an initial nucleus of ideas, values, and visions with which we might start? Although a complete answer to these questions is beyond the scope of this article, I con- clude with two very brief observations:

To answer the first question, the culture for emerging design will result from discussion in various design arenas and from stimuli encountered in interaction with other cultural worlds. Therefore, these discussions among peers must be started and occasions for generative interactions with actors endowed with dif- ferent cultures and experiences must be created.

The answer to the second question stems from both the transition and the social learning process in which we find our- selves. In this framework, society can be seen as a huge future- building laboratory—a laboratory that, amidst numerous contradictions, is already emitting signs of a new culture:...*17 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------*17! Anna Meroni, ed., Creative Communities. People Inventing Sustainable Ways of Living (Milan: Polidesign, 2007); Manzini and Tassinari, “Sustainable Qualities,” 217–32; and Ezio Manzini, “Making Things Happen: Social Innovation and Design,” in Design Issues 30, no. 1 (Winter 2014): 57–66.

...emerg- ing ideas and practices that are affecting the mainstream concep- tions of time, place, work, well-being, and, more generally, the quality of human relationships: ideas and practices that, in my view, are starting to weave the fabric of a new civilization and, hence, if we are able to recognize it, also of a new design culture.

DesignIssues: Volume 32, Number 1 Winter 2016

**TEXT 2 BY DONALD A. NORMAN

WHY DESINN EDUCATION MUST CHANGE

" Traditionally what designers lack in knowledge, they make up for in craft skills. Whether it be sketching, modeling, detailing or rendering, designers take an inordinate amount of pride in honing key techniques over many years. Unfortunately many of these very skills have limited use in the new design domains. " (Core 77 columnist Kevin McCullagh: (http://www.core77.com/blog/columns/is_it_time_to_rethink _the_t-shaped_designer_17426.asp)

I am forced to read a lot of crap. As a reviewer of submissions to design journals and conferences, as a juror of design contests, and as a mentor and advisor to design students and faculty, I read outrageous claims made by designers who have little understanding of the complexity of the problems they are attempting to solve or of the standards of evidence required to make claims. Oftentimes the crap comes from brilliant and talented people, with good ideas and wonderful instantiations of physical products, concepts, or simulations. The crap is in the claims. In the early days of industrial design, the work was primarily focused upon physical products. Today, however, designers work on organizational structure and social problems, on interaction, service, and experience design. Many problems involve complex social and political issues. As a result, designers have become applied behavioral scientists, but they are woefully undereducated for the task. Designers often fail to understand the complexity of the issues and the depth of knowledge already known. They claim that fresh eyes can produce novel solutions, but then they wonder why these solutions are seldom implemented, or if implemented, why they fail. Fresh eyes can indeed produce insightful results, but the eyes must also be educated and knowledgeable. Designers often lack the requisite understanding. Design schools do not train students about these complex issues, about the interlocking complexities of human and social behavior, about the behavioral sciences, technology, and business. There is little or no training in science, the scientific method, and experimental design. Related problems occur with designers trained in engineering, for although they may understand hard-core science, they are often ignorant of the so- called soft areas of social and behavioral sciences. The do not understand human behavior, chiding people for not using technology properly, asking how they could be so illogical. (You may have all heard the refrain: "if only we didn't have people, our stuff would work just fine," forgetting that the point of the work was to help people.) Engineers are often ignorant of how people actually behave. And both engineers and designers are often ignorant of the biases that can be unwittingly introduced into experimental designs and the dangers of inappropriate generalization. The social and behavioral sciences have their own problems, for they generally are disdainful of applied, practical work and their experimental methods are inappropriate: scientists seek “truth” whereas practitioners seek "good enough." Scientists look for small differences, whereas designers want large impact. People in human-computer interaction, cognitive engineering, and human factors or ergonomics are usually ignorant of design. All disciplines have their problems: everyone can share the blame.

Time to change design education

Where once industrial designers focused primarily upon form and function, materials and manufacturing, today's issues are far more complex and challenging. New skills are required, especially for such areas as interaction, experience, and service design. Classical industrial design is a form of applied art, requiring deep knowledge of forms and materials and skills in sketching, drawing, and rendering. The new areas are more like applied social and behavioral sciences and require understanding of human cognition and emotion, sensory and motor systems, and sufficient knowledge of the scientific method, statistics and experimental design so that designers can perform valid, legitimate tests of their ideas before deploying them.

Designers need to deploy microprocessors and displays, actuators and sensors. Communication modules are being added to more and more products, from the toaster to the wall switch, the toilet and books (now called e-books). Knowledge of security and privacy, social networks, and human interaction are critical. The old skills of drawing and sketching, forming and molding must be supplemented and in many cases, replaced, by skills in programming, interaction, and human cognition. Rapid prototyping and user testing are required, which also means some knowledge of the social and behavior sciences, of statistics, and of experimental design.

In educational institutions, industrial design is usually housed in schools of art or architecture, usually taught as a practice with the terminal degree being a BA, MA, or MFA. It is rare for in design education to have course requirements in science, mathematics, technology, or the social sciences. As a result the skills of the designer are not well suited for modern times.

The Uninformed Are Training the Uninformed

My experience with some of the world's best design schools in Europe, the United States, and Asia indicate that the students are not well prepared in the behavioral sciences that are so essential for fields such as interaction and experience design. They do not understand experimental rigor or the potential biases that show up when the designer evaluates their own products or even their own experimental results. Their professors also lack this understanding. Designers often test their own designs, but with little understanding of statistics and behavioral variability. They do not know about unconscious biases that can cause them to see what they wish to see rather than what actually has occurred. Many are completely unaware of the necessity of control groups. The social and behavioral sciences (and medicine) long ago learned the importance of blind scoring where the person scoring the results does not know what condition is being observed, nor what is being tested.

The problem is compounded by a new insistence by top research universities that all design faculty have a PhD degree. But given the limited training of most design faculty, there is very little understanding of the kind of knowledge that constitutes a PhD. The uninformed are training the uninformed.

There are many reasons for these difficulties. I've already discussed the fact that most design is taught in schools of art or architecture. Many students take design because they dislike science, engineering, and mathematics. Unfortunately, the new demands upon designers do not allow us the luxury of such non-technical, non science-oriented training.

A different problem is that even were a design school to decide to teach more formal methods, we don't really have a curriculum that is appropriate for designers. Take my concern about the lack of experimental rigor. Suppose you were to agree with me – what courses would we teach? We don't really know. The experimental methods of the social and behavioral sciences are not well suited for the issues faced by designers.

Designers are practitioners, which means they are not trying to extend the knowledge base of science but instead, to apply the knowledge. The designer's goal is to have large, important impact. Scientists are interested in truth, often in the distinction between the predictions of two differing theories. The differences they look for are quite small: often statistically significant but in terms of applied impact, quite unimportant. Experiments that carefully control for numerous possible biases and that use large numbers of experimental observers are inappropriate for designers.

The designer needs results immediately, in hours or at possibly a few days. Quite often tests of 5 to 10 people are quite sufficient. Yes, attention must be paid to the possible biases (such as experimenter biases and the impact of order of presentation of tests), but if one is looking for large effect, it should be possible to do tests that are simpler and faster than are used by the scientific community will suffice. Designs don't have to be optimal or perfect: results that are not quite optimum or les than perfect are often completely satisfactory for everyday usage. No everyday product is perfect, nor need they be. We need experimental techniques that recognize these pragmatic, applied goals.

Design needs to develop its own experimental methods. They should be simple and quick, looking for large phenomena and conditions that are "good enough." But they must still be sensitive to statistical variability and experimental biases. These methods do not exist: we need some sympathetic statisticians to work with designers to develop these new, appropriate methods.

When Designers Think They Know, But Don't

Designers fall prey to the two ailments of not knowing what they don't know and, worse, thinking they know things they don't. This last condition is especially true when it comes to human behavior: the cognitive sciences. Designers (and engineers) think that they understand human behavior: after all, they are human and they have observed people all their lives. Alas, they believe a "naive psychology": plausible explanations of behavior that have little or no basis in fact. They confuse the way they would prefer people to behave with how people actually behave. They are unaware of the large experimental and theoretical literature, and they are not well versed in statistical variability.

Real human behavior is very contextual. It is readily biased by multiple factors. Human behavior is driven by both emotional and cognitive processes, much of which is subconscious and not accessible to human conscious knowledge. Gaps and lapses in attention are to be expected. Human memory is subject to numerous biases and errors. Different memory systems have different characteristics. Most importantly, human memory is not a calling up of images of the past but rather a reconstruction of the remembered event. As a result, it often fits expectations more closely than it fits reality and it is easily modified by extraneous information.

Many designers are woefully ignorant of the deep complexity of social and organizational problems. I have seen designers propose simple solutions to complex problems in education, poverty, crime, and the environment. Sometimes these suggestions win design prizes (the uniformed judge the uninformed). Complex problems are complex systems: there is no simple solution. It is not enough to mean well: one must also have knowledge.

The same problems arise in doing experimental studies of new methods of interaction, new designs, or new experiences and services. When scientists (and designers) study people, they too are subject to these same human biases, and so cognitive scientists carefully design experiments so that the biases of the experimenter can have no impact on the results or their interpretation. All these factors are well understood by cognitive scientists, but seldom known or understood by designers and engineers. Here is a case of not knowing what is not known.

Why Designers Must Know Some Science

Over the years, the scientific method evolved to create order and evaluation to otherwise exaggerated claims. Science is not a body of facts, not the use of mathematics. Rather, the key to science is its procedures, or what is called the scientific method. The method does not involve white robes and complex mathematics. The scientific method requires public disclosure of the problem, the method of approach, the findings, and then the interpretation. This allows others to repeat the finding: replication is essential. Nothing is accepted in science until others have been able to repeat the work and come to the same conclusion. Moreover, scientists have learned to their dismay that conclusions are readily biased by prior belief, so experimental methods have been devised to minimize these unintentional biases.

Science is difficult when applied to the physical and biological world. But when applied to people, the domain of the social sciences, it is especially difficult. Now subtle biases abound, so careful statistical procedures have been devised to minimize them. Moreover, scientists have learned not to trust themselves, so in the social sciences it is sometimes critical to design tests so that neither the person being studied nor the person doing the study know what condition is involved – this is called "double blind."

Designers, on the whole, are quite ignorant of all this science stuff. They like to examine a problem, devise what seems to be a solution, and then announce the result for all to acclaim. Contests are held. Prizes are awarded. But wait-- has anyone examined the claims? Tested them to see if they perform as claimed? Tested them against alternatives (what science calls control groups), tested them often enough to minimize the impact of statistical variability? Huh? say the designers: Why, it is obvious – just look - What is all this statistical crap?

Journals do not help, for most designers are practitioners and seldom publish. And when they do, I find that the reviewers in many of our design journals and conferences are themselves ignorant of appropriate experimental procedures and controls, so even the published work is often of low quality. Design conferences are particularly bad: I have yet to find a design conference where the rigor of the peer review process is satisfactory. The only exceptions are those run by societies from the engineering and sciences, such as the Computer-Human Interaction and graphics conferences run by the Institute of Electronic and Electrical Engineers or the Computer Science society (IEEE, ACM and the CHI and SIGGRAPH conferences). These conferences, however, favor the researcher, so although they are favorite publication vehicles for design researchers and workers in interaction design, practitioners often find their papers rejected. The practice of design lacks a high quality venue for its efforts.

Design Education Must Change

Service design, interaction design, and experience design are not about the design of physical objects: they require minimal skills in drawing, knowledge of materials, or manufacturing. In their place, they require knowledge of the social sciences, of story construction, of back-stage operations, and of interaction. We still need classically trained industrial designers: the need for styling, for forms, for the intelligent use of materials will never go away.

In today's world of ubiquitous sensors, controllers, motors, and displays, where the emphasis is on interaction, experience, and service, where designers work on organizational structure and services as much as on physical products, we need a new breed of designers. This new breed must know about science and technology, about people and society, about appropriate methods of validation of concepts and proposals. They must incorporate knowledge of political issues and business methods, operations, and marketing. Design education has to move away from schools of art and architecture and move into the schools of science and engineering. We need new kinds of designers, people who can work across disciplines, who understand human beings, business, and technology and the appropriate means of validating claims. Today's designers are poorly trained to meet the today's demands: We need a new form of design education, one with more rigor, more science, and more attention to the social and behavioral sciences, to modern technology, and to business. But we cannot copy the existing courses from those disciplines: we need to establish new ones that are appropriate to the unique requirements of the applied requirements of design.

But beware: We must not lose the wonderful, delightful components of design. The artistic side of design is critical: to provides objects, interactions and services that delight as well as inform, that are joyful. Designers do need to know more about science and engineering, but without becoming scientists or engineers. We must not lose the special talents of designers to make our lives more pleasurable.

It is time for a change. We, the design community, must lead this change.

***MY OPINION IN DISCUSSION FORUM ABOUT WHY RIGHT NOW IT IS MORE IMPORTANT THAN BEFORE TO APPLY A NEW KIND OF DESIGN THUNKING.

Nowadays the world is changing in many ways: technological, political, economic, social, cultural ..and all these processes require a new reflection, a new design vision that adequately reflects the times, however, for now design schools suffer from the lack of a clearly constructed strategy and methodology on how to make this happen. This is also the main idea in the Manzini / Norman articles where they give some suggestions to solve this problem.

EZIO MANZINI talks about the lack of a cultural dimension of design as a serious limitation that must be covered by the new interpretations for design of the XXI century. The approach to this new design must now include not only designers and experts, but also end users. It emphasizes design culture as the result of a kind of global forum, reflecting the views of differently localized designers, which would improve both individual and collective life. The focus of this new design culture is the human being with his abilities, socialization and motivation. But since the participants in the different regions have specific cultural needs, and a deep cultural discourse on a unified vision for the future is missing, the vision of product functionality, as part of the global technological and communication network in which we live, could be reconsidered.

The work process itself should not be administered

/automated/ by the experts/designers/, but to be considered primarily as part of a social dialogue /conversation/ in which everyone gives ideas and has freedom of action (even if this creates certain work problems). It is also a way to avoid the dictates of the "big ego" that is typical of a small group of prominent designers in the recent past.

On the other hand, DONALD A. NORMAN is more focused on the practical application of creating a new type of design thinking. He emphasizes that the effectiveness of the design cannot consist in its aesthetic presentation and spectacular appearance, because modern design is part of the problems in a complex, multidimensional, dynamic and rapidly changing information-technological world and only a good knowledge of it can guarantee the required quality.

Unfortunately, according to him, most of today's designers are not ready to meet this challenge, relying only on temporary opportunistic solutions without considering the problems in the necessary depth.

One of the main reasons for this is the lack of an idea of the social interconnection between human behavior and technology and business, as well as the lack of knowledge about the different sciences and the interaction between them. Experimentation, comparison, statistics, and alternative testing are also not part of the curriculum in design schools, resulting in a general lack of awareness among designers. If in the 60s and 70s the design focus was mainly on form and function, as well as on materials and production, nowadays we talk about interaction design, and experience design, which are not so related to the design of physical objects , as much as with knowledge of social sciences and the interaction between them. There is also a need for appropriate methods to validate them in practice… And with all this, the creative and unique artistic characteristic of the design should be preserved.

0 notes

Text

ventiquattro novembre

Mino Maccari, Conversazione, 1960

Giardino d’inverno

Sono i disegni crudi dei rami

gli anni che mi ritrovano,

nuda d’ogni promessa.

Inaridito seme non germogli,

non t’illude amor di vita.

Cerchi nell’onda delle nevi,

nel ritmico sopore delle cose

il lampo vivo di due occhi fanciulli.

Li sigillò la neve

nel silenzio lungo degli anni.

Restano quei disegni

d’alberi desolati,

or…

View On WordPress

#Ahmadou Kourouma#Arundhati Roy#Baruch Spinoza#Carlo Carabba#Carlo Collodi#Donata Doni#Emir Kusturica#Erich Scheurmann#Gianni Farinetti#Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec#Inge Feltrinelli#John De Andrea#Laurence Sterne#Luigi Ontani#Lynn Chadwick#Mino Maccari#Raffaello Baldini#Ricardo Piglia#Scott Joplin#Serge Chaloff#Teddy Wilson

0 notes

Link

#Raffaello Baldini#monologo#teatro#coglionaggine#consigli#humor#umorismo#ironia#satira#post#blog#mixmic.it

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

- Raffaello Baldini

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

VOCI D'AUTORE

Ivano Marescotti

legge Raffaello Baldini

.

youtube

.

.

.

.

.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Non lo faccio mai, ma. Scoperto in un piccolo cinema di Bologna dove proiettavano Strane storie - Racconti di fine secolo. Amato per tutto, in particolare per le meravigliose letture delle poesie di Raffaello Baldini. Ciao Ivano ❤️

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

D’estate caldo, un sudaticcio, zanzare,

no, mi piace l’inverno a me, quelle belle giornate

col sole, un’aria che taglia,

le pozzanghere ghiacciate,

e gli alberi senza foglie, che ogni tanto

tra i rami si vede un nido.

(Raffaello Baldini)

73 notes

·

View notes

Photo

incontro sull’oralità nella poesia del novecento: 7 ottobre allo spazio pagliarani

0 notes

Photo

Nella residenza creativa di Ghermandi/Toccafondo

“Uno così schifiltoso non l'ho mai visto.

Tutto il giorno era dietro a lavarsi le mani.

Teneva il manico della tazza del caffè

verso l'alto, dritto al naso,

beveva dove non beveva nessuno.

D'estate l'aranciata

la prendeva sempre con la cannuccia.

E anche nelle baldorie

guai a sbagliare bicchiere,

aveva schifo di tutti, un ultimo dell'anno,

che gli era caduto per terra il cucchiaino,

ha lasciato lì a metà la zuppa inglese.

Non stringeva la mano a nessuno,

con la gente stava sempre un po' lontano,

e quando qualcuno si riscaldava

nel parlare e gli veniva troppo vicino,

e per di più magari sputacchiava un po',

lui si strisciava una mano sulla faccia,

come non volendo, come se si grattasse

la barba, e poi invece la mano

se la fermava aperta sotto il naso,

contro la bocca.

Che mettersi a sedere su una sedia calda

da cui s'era appena alzato qualcuno

preferiva piuttosto stare in piedi.

Quando viaggiava in treno

non toccava mai niente, e nello scendere

si prendeva alla maniglia con due dita.

Ogni tanto si faceva rapare a zero

per rinforzare i capelli, ma anche

perché i capelli erano un ricetto

di polvere, di porcheria, di microbi.

Aveva sempre paura delle infezioni,

di prendere le malattie, che gliele attaccassero.

Nominava spesso la Tina di Zioli,

che da ragazza

nel grattarsi un foruncolo con le mani sporche

s'era fatta venire il sangue

e tre giorni dopo aveva quaranta di febbre

e non c'è stato niente da fare.

A un cane non ha mai fatto una carezza,

nello spaccio non l'hanno mai visto leccare

un francobollo.

Era sempre pulito, anche un po' profumato

perché il profumo in fondo disinfetta.

E col tempo la gente ha capito,

non gli stavano vicino,

il barbiere aveva un rasoio solo per lui,

non gli domandavano in prestito nemmeno il

giornale.

Ma non è bastato. È morto tisico a trent'anni.”

Raffaello Baldini, Lo schifiltoso

#Francesca ghermandi#residenza creativa#il teatrino di Raffaello Baldini#gianluigi toccafondo#nicoletta fabbri#scuola elementare#poesia italiana

4 notes

·

View notes