#I think it's a very honest portrayal of queer identity struggles

Photo

#Dating Amber#movie poster#David Freyne#Fionn O'Shea#Lola Petticrew#Sharon Horgan#Barry Ward#Evan O'Connor#It has an emotional depth that the trailer really doesn't give away#Fionn O'Shea's and Lola Petticrew's perfomances are truly the heart of the movie#I think it's a very honest portrayal of queer identity struggles

0 notes

Text

Day 20: Song that reminds you of pride

Okay now to be honest, there's a fuck ton of songs that remind me of pride because I'm a struggling queer person and like relating songs to my circumstances lol,,, but there's a specific few that legit just make me think of the lgbt community and our strength and struggles sooooooo here we go hehe

libidO - OnlyOneOf

It's literally just gay? like straight up? and it's honestly a brilliant song I'm glad they made and released it it's quite meaningful I love it sm 😩

0X1=LOVESONG - Tomorrow x Together

Not quite as bold as libidO but also,,, just as bold. I dunno something about their portrayal and the iconic leslie cheungs mambo (the lil dance yeonjun did in the mv is actually from a gay icon who sang and acted in Hong Kong) it just really,,, f e e l s queer,,,, as a queer person myself,,,, and it also makes me devastatingly sad like omg anyways I know e x a c t l y how I relate it to pride and the community but I'll just save that in my brain for now

Pretty much the entirety of skz ngl they use very gender neutral language and the issues they talk about in their songs makes it v e r y easy to relate to them sjjsksks

ofc Holland's entire discography. I'm proud of him for having the strength to be an actual o u t gay idol TT

All In - MonstaX

honestly just watch the mv you'll understand,, 😩

New Heroes - Ten (NCT)

okay you might be a lil confused with this one since there's nothing in this song to suggest lgbt or pride or anything,,,, but the lyrics,,,, just like,,,, it's easy to imagine that those words are encouragement for the lgbt community to keep on despite the blatant hatred and mistreatment from those around us because if we make it through all this pain and hardship, we can be "the new heroes" and inspire young queer kids to keep fighting and one day we'll have the rights and respect that we deserve just like yall cishets do lol love you cishets

Taemin,,,, all of it,,,,, I aspire

I'm sure we all recall how much if a cultural reset this glorious piece of work was,,, I mean,,,, everything about it is just Confidence and Power and Androgyny without being overly aggressive with it you know. It's like he's defying stereotypes because that's who he is and not just to get attention. it's truly a blessing. that's what I wanted to say with Ten too,,, okay well maybe androgynous isn't how I would put it it's more,,,,,,, unrestricted by the bounds of societies expectations and the gender binary (!!!!! that's it :D) They both wear what they want and perform in a way that expresses who they are b e a u t i f u l l y and it's really amazing. I admire them (and ofc the many other idols who do this too) a lot for sticking up for who they are and not crumbling under the standards of society,,, that's exactly what we should be doing especially as queer folk. If we can find the strength to be open (at least to ourselves,,, don't push down what makes you you) and proud of ourselves and what makes us unique I know we can be happy and successful. after all, success isn't just defined by monetary stability right?

I KEEP ON RANTING ON THESE AND I NEVER GO BACK OVER TO MAKE SURE IT MAKES SENSE BEFORE POSTING IM SO SORRY EVERYONE I REALLY DONT THINK IVE HAD A SINGLE COHERENT THOUGHT IN MY LIFE BWUAHAHAH ANYWAYS I WAS JUST TRYNA SAY THAT THOSE SONGS MADE ME THINK OF PRIDE BECAUSE OF THE STRENGTH TO ADMIT WHO THEY ARE AS PEOPLE AND THE PERSEVERANCE THAT THEY PORTRAYED TO KEEP GOING EVEN THOUGH PEOPLE KEEP ON PUSHING YOU DOWN IT JUST MAKES ME THINK OF WHAT I PERSONALLY ASSOCIATE THE LGBT PRIDE TO BE ABOUT

Anyways y'all,,,, good night I love each and every one of you. If you ever need anything don't hesitate to message or if you just wanna talk about something random go ahead lol. I'm proud of you and how far you've already come in life and remember,,,, you're valid, your identity is valid, your thoughts are valid, your opinions are valid, and your struggles are valid. Stay safe, see you next time <<<33333

#lgbtq#lgbtq pride#shareyourpride#trans#transgender#kpop#stray kids#skz#taemin#shinee#nct#wayv#0x1=lovesong#tomorrow by together#txt#monsta x#onlyoneof#holland kpop#queer pride

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Russell T Davies on straight actors and gay characters.

I decided to put this here because I post a lot of Hilson stuff. As an actor, this article hit a nerve. However, as a defender of free speech, Davies is allowed to have his opinion without me thinking of him as insensitive. Just like I am allowed to have my own opinion and argument, and ask questions without being labeled “homophobic, intolerant” etc. (that would just make me laugh because have you SEEN my blog? Anyway, I’ve seen a few other websites covering this article. I am also very skeptical of everything I read, including the sources, and I try not to blindly believe everything. That being said, I felt like posting this to get other opinions and ask honest question to help my understanding. If this has already been covered on Tumblr, please feel free to send me the conversations! Some background on me: I graduated with a BA in Theatre and have worked both on and off the stage since I was twelve years old. I have directed plays and an audio play. Given my experience and dedication to my craft, I think my opinion is worth something.

Also, for the sake of this argument, I am leaving trans-actors out because that’s a whole different post. Here is the article:

https://news.sky.com/story/russell-t-davies-straight-actors-should-not-play-gay-characters-12185652

Okay, so first things first, let’s talk about this: “Speaking to the Radio Times, Davies compared a straight actor playing a gay character to black face.” Something that irks me is when one person tries to speak for a whole community and doesn’t reference people from said community who might disagree: whether it’s the LGBTQ+ community, a religious community, medical community, etc. The list goes on. Here, Davies is speaking on behalf of, or speaking for, both the LGBTQ+ community and the black community, is he not? I am genuinely asking because I would like to be more educated on this kind of speech.

Then Davies says, "I'm not being woke about this... but I feel strongly that if I cast someone in a story, I am casting them to act as a lover, or an enemy, or someone on drugs or a criminal or a saint... they are NOT there to 'act gay' because 'acting gay' is a bunch of codes for a performance.” Does that not discredit his whole statement? If any actor does a caricature version of anything and doesn’t take it seriously or really works to get into the role and the mindset of a character, they’re not a good actor. At least, they’re not an actor that I’d want to hire. Second, by the logic that a straight person shouldn’t play a gay character, should someone without a criminal record not be able to play a criminal character? Before you go off and say “it’s about identity and sexuality, and playing a criminal is about the choice to break the law” or other arguments, I hear you. I’m not talking about that. I’m talking about the experience. How can an actor who has never committed a crime play a criminal character authentically? They do their research: reading, interviewing, etc. I’m not saying that an actor with a few minor marks on his record shouldn’t be considered for the same role. I’m saying that in an audition setting, if both of these actors were auditing for the role and the non-criminal-record actor just happened to do a better job and fit what the director and/or writer wanted, is that a mark against the criminal-record-actor? Maybe personally because we don’t know what the director is thinking. But chances are, it’s not a mark against the other actor. The other one just happened to have a better audition. Or, a major factor when considering casting, said actor was easy to work with--I’ve seen a lot of talented actors lose a lot of roles because of their inability to take criticism or notes.

Plus, the whole “Breaking Bad” series?? I highly doubt the main actors were meth-making drug-lords. Or, a better example, “The Wire?” In that show, we see the constant battle and deals between drug-lords and cops.

Another point I’d like to make: “...is a bunch of codes for a performance.” That’s exactly right. The audience doesn’t want to know an actor is “performing.” We know that going in, with what is called “suspension of disbelief.” We know the whole show is a performance, but we also expect the actors to be truthful (unless it’s a comedy/farce, but again, that’s a different argument).

Was it bad that, before 2020, some main characters in TV shows were portrayed as straight but the writers ended up “queer-baiting?” I am referring, of course, to House, M.D. (If you follow this blog, you’ll understand.) But I am also referring to the BBC Sherlock Holmes series. Yes, both pairs of characters (House and Wilson; Holmes and Watson) are assumed to be straight. However, some episodes allude that there could also be something more there. Even the actors have said in various interviews that they aren’t sure if it’s a true romance that the characters are afraid to face, or just a strong bond between best friends that blurs the line between platonic and romantic. I’m paraphrasing, but you get the picture. Therefore, should these characters have only been played by straight actors who are questioning their sexuality or feelings for a best friend? Would it have been disrespectful to gay people if these characters ended up becoming romantically involved? (If we ask the Hilson and Johnlock community, I’m guessing that’s a resounding “NO WAY! IT WOULD BE A DREAM COME TRUE!” xD <3)

“It's about authenticity, the taste of 2020.” *Cinema Sins sigh*

"You wouldn't cast someone able-bodied and put them in a wheelchair...” Again I say, directors and casting directors need to ALWAYS search for someone who is in a wheelchair, or deaf, or HOH, etc. before looking for an able-bodied actor to play a character with that disability (I’m iffy on the whole term “disability because of its negative connotations, but I’m using that word in order to keep this post as long as possible). But I give you the example of Rainman with Dustin Hoffman. Or A Beautiful Mind with Russell Crowe. Or the play and movie Proof, where the father had a mental illness? Anthony Hopkins was diagnosed late in life with Asperger’s Syndrome, but the father in Proof was written to allude more to schizophrenia. And yet, Anthony Hopkins did a tremendous job in that role. Or Even Forrest Gump with Tom Hanks. Many people today love Tom Hanks and laud him as a “woke” celebrity. But if he were to portray the role of Forrest Gump today, how many people would try to “cancel” him or at least have very strong words for the director not casting an actor with autism, due to the character’s autistic tendencies? A whole lot of people on the internet and Twitter, I’ll bet. As someone who struggles with anxiety and panic disorder, would I be upset if someone without that mental illness got cast in a role of a character struggling with that? Sure I would. But if they did an authentic job and approached the role respectfully, it would be hard to stay irritated. Besides, there are always more roles created practically everyday.

To continue on with Davies’ quote: “...you wouldn't black someone up.” Yikes. I’m sure he didn’t mean this in a cast-off kind of way, but that’s how it comes across. I can see now why he said he wasn’t “being woke about this,” because a more “woke” way of putting that would be...what, exactly? “You wouldn’t cast a non-black person in a black role.” That sounds better and less harsh. Or even “a white person in a minority role.” Which should be common sense, and I agree with both statements.

And then “Authenticity is leading us to joyous places." Oh! Look at that! There’s that word that I’ve been using and emphasizing throughout this whole post! Authenticity is one major brick in the foundation of good, credible acting.

“High-profile examples of straight performers playing LGBTQ+ characters include Rami Malek's Oscar-winning portrayal of Freddie Mercury in Bohemian Rhapsody, and Taron Egerton's Golden Globe-winning turn as Sir Elton John in Rocketman.”

I haven’t seen Rocketman, but I saw Bohemian Rhapsody and it was great! Why am I high-lighting this movie? Because it’s the perfect example of a straight actor playing a gay character and playing it authentically, while also looking a lot like the real person they’re portraying. If a look-a-like had been cast who also happened to be gay, but couldn’t act to save their life or couldn’t bring as much as Rami brought to the role, wouldn’t that kind of put a damper on the film? And yet, Rami Maleck both looked the part and brought an authenticity to the role that many Queen fans loved and appreciated. Even the remaining Queen band members said that he did an incredible job and Freddy would be proud. I wonder if Freddy would care that Rami wasn’t gay? I doubt it, but no one can know for certain.

Then there’s the whole term “gay face.” I personally don’t think this is the right term to use because it could possibly diminish the whole meaning and importance of “black face.” Even if Corden appeared to be mocking gay people (I never watched The Prom so I have no idea what his performance was like), calling it “gay face” takes away from and inadvertently belittles the whole dark history of “black face.” Black face’s whole history comes out of an even darker history of racist times filled with hatred and ignorance. I’m not saying that gay people haven’t had their own experiences with hate and intolerance, but isn’t kind of “un-woke” and “insensitive” to compare the hundreds of years of blatant, public racism against an entire race of people to the intolerance of homosexuals? (Again, I’m asking this genuinely because I want to learn and get other people’s opinions. I’m not trying to speak for any community, and I recognize that my personal opinion on this matter is just that: my opinion. And I could be better informed.)

Along the lines of the above paragraph, is it wrong to say or think that casting a non-minority actor in a minority role is a lot different from casting a straight actor in a gay role? Sexuality comes in all shapes, sizes, and colors; that is to say, every race has people with different sexualities. But I think it would be pretty cringe if a Caucasian actress was cast in a role meant for an Asian or African-American woman.

Director Joe Mantello told Sky News the casting was not intentional, but rather a "very fortunate series of events".

He continued: "That being said, I think having an out gay cast really did inform the work and it took on a particular kind of tone because of that, which is not to say that's the only way to approach this material. But for this particular group, it did something that I think is very, very special. There's a chemistry that they have."

And this man summed up my entire argument! He also put into simpler terms what I have been trying to express about the beauty of theatre: there will always be special casts, especially when there’s a great chemistry from a shared experience. A "very fortunate series of events,” indeed. “The casting was not intentional...” leads me to believe that the director didn’t set out to have an all out-gay-cast, but rather, each actor brought great performances to their auditions and were considered by the director to be perfect for the roles. These actors also just happened to be gay.

If you’re still here after all of that, let me take a moment to sincerely thank you for reading the whole thing! I know it’s a lot, but I’m very passionate about acting and giving each and every actor a fair chance. Let me know what you think, and please be respectful!

#russell t davies#straight actors and gay characters#opinion#article#actor#theatre#film#television#hilson#johnlock#bbc series sherlock holmes#the prom#bohemian rhapsody#forrest gump#tom hanks#rocketman#this took way longer than i expected and i'm not even going to submit this anywhere#i feel like i'm back in college writing an argumentative essay#woke#woke culture#wokeness

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

[Alright take-two on this damn post. First one got eaten by post editor right as I was ready to post. You see how long this is? Save to drafts, kids.]

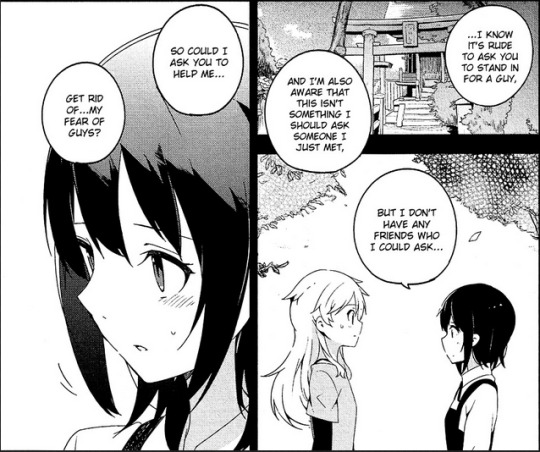

I’m here to shove a manga on you: Ookami Shounen Wa Kyou Mo Uso O Kasaneru (The Boy Who Cried Wolf Also Told a Lie Today). It’s a gender bending romance. Despite how awful that probably sounds, it’s actually really fucking good and I do not say that lightly.

(No spoilers, this is all in the first chapter)

A high school boy insecure about his intimidating face, Itsuki, has fallen for a shy loner girl, Tokujira, who does not seem specifically phased by his naturally scary face. So he takes a risk and confesses, but she turns him down brutally. Itsuki goes to his sister to lament his insecurities about his face, which he (more or less correctly) attributes as why he can’t make connections. To give him a new perspective on his appearance, his sister (trans btw) gives him a makeover while he’s sleeping and then kicks him to the curb of her salon - fully crossdressed. On his way home, Itsuki (♀) ends up bumping into Tokujira, and she mistakes him for a boyish girl. Under this misunderstanding, she asks "her” for a favor...

She has androphobia, and she has it bad. So much so she can’t even look at men without snapping violently or becoming physically ill. And Itsuki (♀) is just boyish enough to trigger her, but not enough to lock her down. So she asks for “her” help, to see if she can desensitize herself to her phobia. Itsuki’s in a bind for a couple obvious reasons, not the least being the guilt of deceiving Tokujira. But nonetheless, he genuinely wants to help her. So, he decides to continue crossdressing, diving into a lie that he soon finds he has no easy exit from.

I really recommend this manga. I cannot say that enough times. It is phenomenal, shattering tropes left and right in fun and interesting ways. Do yourself a favor and give this manga a try.

Personal feelings and meta analysis below the cut. It’s, uh, ungodly long, and will get very spoilery. But I will flag spoilers. And there will be pretty pictures?

(Also, no, I did not go into this planning to compare a manga about crossdressing to the abolitionist writings of Frederick Douglass, but reality deserves to be a bit absurd sometimes.)

Before you think I’m getting spoilery, with the intro I gave or anything I don’t mark as spoilers, I’m really not. Everything outside of spoilers is right on the package at the start. It sounds like I’m spoiling late-game stuff, right? That’s something that was really fantastic to me: this manga doesn’t spoon feed you. There’s no arcs of pure silent angst, even at the lowest point in the story. These kids are smart, they think and intuit on the spot, and they share what they’re feeling with each other like good friends do. Like that next panel down there with Itsuki introspecting about his confidence level while crossdressing? That’s from the first chapter! These kids are smart. And god damn that is so nice to see.

There was a lot I liked about this manga, but at the top is how compelling the protagonist and his internal conflict are. Right from the first chapter he’s already wracked with guilt about what he’s about to do: deceive this girl by pretending to be a safe space. But Tokujira told Itsuki (♀) she hopes to one day be able to fall in love, and Itsuki wants to ensure she can have that - even if it’s not him that gets to confess to her. He’s fully aware of exactly how fucked up what he’s doing is, and is appropriately beating himself up over it in a really realistic way. But although the guilt never fades, it slowly gains company in happiness. He enjoys this new, fragile life he has constructed around the two precious new friends he's made as a girl.

It was probably easy to gloss over in the synopsis, but arguably the biggest part of Itsuki (♂)’s conflict is his complex about his face. He looks dangerous, and because of that he is afraid to even lift his head or smile in front of others. But as Itsuki (♀), he smiles and laughs without fear. It becomes immediately clear to him on the first day that he's a more confident person while crossdressing. Happier in a way he can't be as a man.

Botan is easily my favorite character in the series. She’s introduced early on, as Tokujira’s first and only friend before Itsuki (♀). At the start she’s a dangerous third wheel, a serious threat to Itsuki’s ability to keep up his lie. And though the situation is (thankfully) defused rather quickly, she becomes a massive source of internal conflict for Itsuki. Nonetheless, she becomes a dear friend for both Itsuki ♂ and ♀. She’s just so...*chef’s kiss*

^This face is the repository of all my love and affection.

Mark my words, this is the first and I assume last time I will ever say this: love triangle good. You know it’s inevitable in a romance genre piece, but this manga approaches the trope in a new and compelling way. [Spoiler] Needless to say, it’s between Itsuki, Tokujira, and Botan. But...there’s two Itsukis involved, ♂ and ♀, and in the center of it all is this lie. His lie stops being about him: it's about not hurting these two girls he cares so much about. [/Spoiler]

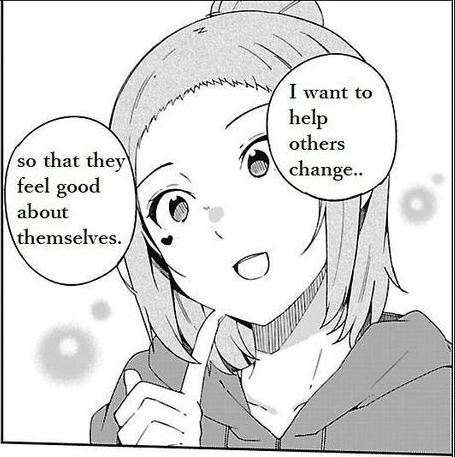

On a more personal note, I saw so much of myself in Itsuki’s older sister, Ibuki. She runs a salon, catering especially to crossdressers and transwomen. She’s a self-described “Youthling”, an alien from the planet Youth, obsessed with observing the exciting and turbulent lives of the youths of earth. For more or less for the same reasons most of us do: transpeople don’t tend to get the youths we want, if we allow ourselves to experience youth at all. So it’s nice to be able to enjoy it vicariously, through this younger generation that is able to more fearlessly pursue the lives we couldn't.

^Incidentally, one of my favorite interactions in the manga.

Despite getting Itsuki into this crossdressing mess, she’s someone he can always return to and confide in, and get good, helpful advice from. Her whole philosophy is to give young people agency to explore their identities and find themselves, and though she tells Itsuki the road he's taking is dangerous as soon as she learns what he's doing, she'll always support him however she can.

That, I feel, is what separates her from other, more creepy/pedophilic enabler types, like Sawako from K-On! or Lucoa from Dragon Maid. It’s a refreshingly honest and respectful portrayal of a quirky adult just trying to be a good older sister.

The last thing I want to say, and I’m not going to even mark this as a spoiler because of course it’s going to happen and if you can’t predict that then you’re not my problem, is that Itsuki of course eventually has to drop his lie. All I’ll say about it is that it is probably going to live in my head for years. Everything about it, the lead up, the execution, the fallout, and the recovery, are all so masterfully crafted for maximum emotional impact.

That’s all I want to say exclusively about my personal feelings. On to analysis. There will be a lot more contextual spoilers here that, even without reading the parts I’ve specially blocked off will probably leak through. Read at your own risk, but I would recommend revisiting after you have finished the manga.

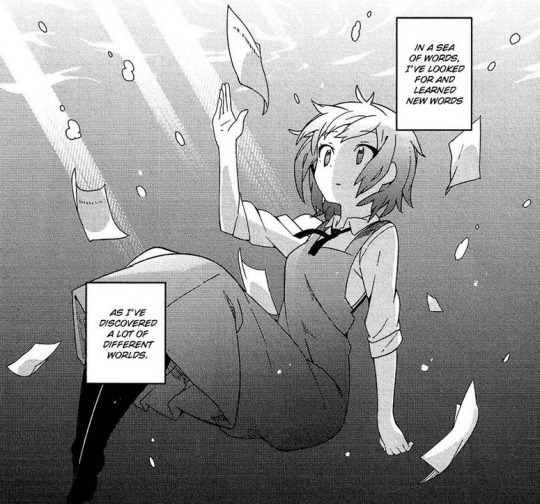

One thing I really want to talk about is language. That’s right, I’m going to compare a crossdressing manga to The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, the autobiography of a freed slave turned abolitionist. Douglass talks about a concept that has remained imprinted on my mind ever since I first read it: how and why slaves struggled to comprehend the concept of freedom. This wasn’t anything to do with fear or “racial inferiority” like pro-slavers would argue, but rather with a lack of vocabulary. They have all of these feelings and things they know to be true, but lack the words to make meaningful sense of them. For Douglass specifically, his life completely changed when he learned the word “abolition.” It was like a floodgate burst, as he was suddenly able to put meaning to feeling, create context from chaos.

And that’s right, we see that happen in a big way, with Tokujira. This should be an obvious development, but as it happens late in the manga I will mark it [Spoiler]. As Tokujira and Itsuki (♀) practice things like talking, eye contact, holding hands, etc., Tokujira naturally starts to fall for Itsuki (♀). But she doesn’t understand that. An important part of her character is that, growing up, she focused on expanding her vocabulary as much as humanly possible in the hopes of being able to better articulate herself. So words are very important to her. It’s not until she sees a work of lesbian fiction on display that she finally realizes that’s the word she’s looking for. The floodgate bursts, and all of her emotions suddenly make sense. She realizes she loves Itsuki (♀). [/Spoiler]

And I think that is a vital and underexplored concept when discussing LGBT youth, especially in countries where even knowledge of these concepts is taboo. The reason so many LGBT youth struggle with their identities, especially trans youth, is because we do not have the vocabulary to conceptualize our feelings. I am always excited to see this concept play out, especially in this context. It’s such an important thing that needs to be addressed more broadly.

Moving on, I want to talk about historical context of the genre as it relates to what the author did here. Notably, I want to talk about a specific trope rampant in Japanese queer fiction, specifically early lesbian fiction: the idea that queerdom is a meaningless, youthful phase that children will naturally and inevitably grow out of. It’s problematic for obvious reasons.

[HELLA HELLA SPOILERS] My kneejerk reaction to the ending of this manga was that the author fell into this trope. In the end, Itsuki comes to the conclusion that he does not need to crossdress. So again, kneejerk. But...it really wasn’t like that. He never had any dysphoria; crossdressing was always just a necessity of his circumstance. Nonetheless he learned to analyze and value his experience crossdressing as a woman, and because of that grew as a man. And as part of his journey to understand his identity we, through him, see why some people crossdress. Along with his example, we see why his sister, a bona fide post-op transsexual, has made it a permanent change to her life. Likewise, we see Miyama, who crossdresses purely for the gender euphoria, but has no (stated) interest in going all the way. These are all presented as valid and meaningful. [/Spoiler]

Crossdressing, and gender nonconformity in general, is portrayed not as some one-dimensional fetish like cultural taboo would depict it to be, but rather a meaningful exercise for exploring and critically analyzing your own identity. For some, yes, it’s a phase, but an importantly transformative one when done right. While for others, it is a gateway to a new way of experiencing and enjoying life. Or, it’s fun just for the pragmatic reasons...

I honestly cannot recommend this manga enough. Tragically, I cannot imagine it ever getting an official english translation, so you’ll have to settle for a scanlation like the one I linked in the title up top (and here, again). It’s a really good translation, though the site is predictably sketchy. Warning for lots of NSFW ads.

Read it, and then come talk to me about it!!! There is basically zero fan community and I need to fangirl with someone!

#long post#and I mean REALLY long post#Ookami Shounen Wa Kyou Mo Uso O Kasaneru#The Boy Who Cried Wolf Also Told a Lie Today#the boy who cried wolf tells a lie today also#analysis

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Portrait of a Drag King - Critical Assessment Report

In the development stage of our project, I looked to the subject for inspiration. Knowing Mia and how they expressed themself enabled me to look deeper into their own world. Spending time with them and looking at them from an outside perspective I could really appreciate how visual they are in her gender and queer expression. Their aesthetics became a focus that all of us as a group wanted to capture. In this stage I began to research queer art and feminist theory, reading Women Don’t Owe You Pretty by Florence Given and watching drag documentaries like Trixie Mattel: Moving Parts, gave me understanding into the world of drag and queer community’s objectification. Also watching shows like Euphoria and We Are Who We Are gave me ideas for visuals and styles we could use in our film. The styles that these shows used to portray queer youth and coming of age resonated with our subject and our portrayal of her.

Our group being allies or members of the LGBTQIA community, made this process safe and open for expression during this stage. Our visual ideas and interview style choices worked together well, I think because we all had the same feeling towards Mia’s story and saw its importance as well how to tell it well. We wanted to tell her story set on a backdrop of grungy 90’s style B-roll with a rough but dynamic edge to the editing.

Our meetings discussing these choices always went well as the group riffed off each other, the entire process was exiting, and everyone agreed of our style choices. With Bethany and I, living close to Mia as well as knowing their personally we decided to take on the role as interviewers. With Rosie’s input we came up with scads of questions ranging from formal to informal.

With our interview questions planned Bethany and I went to St Andrews to film Mia’s Interview as well as their poetry. The interview went extremely well, and we had a great amount of interview archive to give to Rosie who was editing.

With Rosie reviewing the interview and cutting it down, we had a clearer vision of the B-roll we wanted to gather, a follow about style cut where Mia takes us through their living space, her art, St Andrews and their aesthetic expression. With this we went to film the B-roll.

Filming the B-roll proved to be quite challenging, however. Possibly a lack of clarity with the stock we wanted also our goal to overshoot so Rosie would have enough footage to edit, but it all turned out well as our footage emphasised the style choices we wanted, rough, unpolished, intimate and honest to the subject.

With this the footage was sent off and an amazing rough cut was made by Rosie. Adding in brilliant archive from Natalia and Katie made the entire thing come together in a really captivating way. Katie also creating animations of Mia added such amazing amounts of depth and heart to the stock, they were such an amazing addition to our film. The use of colour in our final edit portrayed the amount of vibrancy in the story and the subject. Rosie’s use of trippy 90’s overlays created this allusive tone of the mind space of gender dysphoria and how confusing and frustrating the experience is.

The film didn’t so much have an emphasis on sound as the visuals did. We kept a lot of focus on the interview and the poetry in connection to visual art. With the editing and Mia’s interview adding extra sound would possibly create a hectic and overpowering tone, taking you out of the subject.

Looking back on the film I find it incredibly engaging. I think the way we portrayed their story could really connect with people who struggle with queer expression and dysphoria. Without being bias I myself find Mia to be an incredibly interesting person that I admire a lot, I find her story, their personality and even how they present themself to be engaging. I’d love to think someone watching this film feels represented.

I feel Mia as a character was portrayed very successfully. With all of us engaging in what they were saying and relating to parts of her interview we really grasped their nature. I’ve wanted to make a film about Mia for a very long time, filming them in high school and using them in projects I understand how they expresses herself in performance, intelligence and aesthetics. Our group did an amazing job presenting them. Mia having struggled with dysphoria and her identity must have been a difficult thing to face whilst watching this film, but afterwards they said they were unbelievably happy with it and she felt represented which made this project so much more fulfilling. I loved collaborating with my group and Mia and I am extremely happy with the overall outcome of the film.

4 notes

·

View notes

Link

Booksmart slaps. It’s just a huge amount of fun to watch - the key word here for me is “good-natured”. This is a good-natured movie that teases and pokes fun at a lot of people - a lot of *kinds* of people, from the queer drama kids to the dopey jocks to the Gen Z overachieving feminist types who have pictures of Michelle Obama on their wall and can quote Susan B Anthony from memory - without ever making fun of anyone in a mean-spirited way, and highlighting that no one is ever “just” their tribe. The ending ties the story up neatly with a feel-good bow about how no one is really what they seem on the surface, especially not in high school, when everyone’s trying so hard to be invulnerable… which also means they can’t be *seen*. There’s a lot of great character work here that I think could’ve been fleshed out even more (the 1 hour 45 min runtime feels shockingly short in the day and age of Endgame) but still feels natural and sincere, and the huge array of secondary characters - real characters, not just insert-famous-cameos - gives this movie not just humor but so much life and buoyancy.

(Warning: light spoilers beneath cut)

What keeps it from reaching the top tier for me, though, is that it somehow still feels like something I’ve seen before, even though the window dressing is so different. It’s definitely rare to see female best-friendship displayed so frankly, genuinely, and *hilariously* on the big screen, and I can’t remember another movie where the nerdy valedictorian is a boss and knows it, not to mention one where one of them is a lesbian (my young baby lesbian Amy!! protect that cinnamon roll), but the story of two blood-sworn, childhood-, everything-friends reaching the last chapter of their adolescence together in fun and games and boozy celebration, all while the fear of how they’ll face the great unknown without the other is this silent undercurrent churning beneath… that feels familiar to me? That doesn’t keep me from loving this particular theme, because it IS a great one, I just mean it’s not as original as Ladybird, so it lends itself to comparison more easily.

Superbad, for instance. I actually kinda hate how every review (including the one linked here, which is totally in line with my sentiments) keeps calling this “the female Superbad”. Yes, it’s a coming-of-age comedy about two friends at the end of the senior year trying to go out with a bang together, and yes, it’s a little raunchy, and yes, it really is all about the friendship between the two main characters at its core… but the whole texture, color, and point of Booksmart are completely different.

By texture, I mean that even as the two girls are the “heroes” of this quest, it’s still interested in the characters outside them, such that you really get the sense that they are their own people, with their own lives and inner life. In the briefest of screentimes you grasp instantly why someone like Molly would be attracted to easygoing jock Nick (but then connects to the hopelessly-messy-but-sweet Jared), and why Amy likes the skatergirl with the big toothy grin. The other kids and love interests aren’t just vessels for Molly and Amy’s own awakenings. In fact, some of them have their own troubles, and they’re all really pretty good kids.

It’s interested in the way that the two mains are, in their own way, not the most perfect people. How the world’s really not out to get them; in fact, they’re the ones who have to learn to fit into it. I talk more about this below, but this was the part I liked the most, because it feels particularly true to life in a way that I don’t think I’ve seen in many other coming-of-age narratives, much less light-hearted comedies.

Speaking of light-hearted, the whole tone of the humor is waay different from Superbad’s too. It’s funny as hell, which is probably the most important thing at the end of the day — there were a few scenes that had me and my entire theater howling — but amazingly for a coming-of-age comedy, I remember very few of the jokes being gross-out or sexual, or even all that cringe. Booksmart mines a lot of physical humor just in their sheer facial expressions (if a picture is a thousand words, Beanie Feldstein’s face does the work of a thousand punchlines), but it’s mostly the little throw-away lines and hilarious sketches (the attempted robbery in the car! Amy’s overly-well-meaning parents! everything GiGi and Jared do) that string everything together and carry the day. That’s not to say that there aren’t serious moments that are given due weight too — Amy under the water, submerged in that song is just an absolutely beautiful shot.

It reminds me a little of Bo Burnham’s Eighth Grade, which I think is a more interesting comparison than Superbad here. Booksmart tries to capture some of that raw realness that Eighth Grade had, underneath all the silliness and humor; it is, in many ways, about how hard it is to be vulnerable to someone else, even (especially) the people you love. It pulls at a lot of strands and among them are the idea that this is what high school is really like, that to be honest all these boys (and girls!) who hold your heart in their clumsy, sweaty fingers will be like leaves in the wind years from now, that standing on the entrance to adulthood isn’t a physical change, it’s not about booze, or losing your virginity, or getting accepted by your peers. Becoming an adult is inner work, alright, but it’s also not work you can do on your own. Because it’s about how you treat yourself, but it’s about how you treat other people too.

But I think where Eighth Grade really succeeds is this it has this kind of specificity to it — it really, really is about this awkward girl, and her lonely existence, and about being a girl who is becoming a woman in a certain context. And that specificity gives it a kind of honesty that rings painfully true to me. Booksmart — probably because it is trying to avoid stereotypes and do something entirely new here, which is totally commendable — almost feels a little too universal. It feels like you could replace Molly and Amy here with dudes, and it wouldn’t be a huge change in dynamics outside the pussy hats and Malalia worship, because these two are defined more by their identities as “overachieving party-pooping best-friend NERDS” than by being girls per se. These are two whipsmart dorks who are best friends, and happen to be female, rather than a portrayal of female best friendship per se. And the other kids treat them that way too: no one gives a shit Molly’s chubby or Amy’s a lesbian, they give a shit that they’re exasperating know-it-alls.

Which is REALLY refreshing. I’m being unfair here — it’s *because* it’s so rare to see female friendships or just girls in general depicted this way on screen that I think it doesn’t quite “fit” my own intuitions about real life. But I’m a weird case of someone who really struggled in high school, and definitely didn’t have friends much less deep ones like theirs, and I bet other women would recognize themselves in these two and their relationship much more. The frank vagina talk and the fact that Molly and Amy are actually really self-assured and even pretty damn well-liked are just super freakin’ cool anyways. In particular I LOVE the way they’re still dorky, in a way I so rarely see female characters allowed to be because female characters written by dudes tend to be so poised and “above” the main male protagonist (probably because the screenwriters are thinking back to their own high-school crushes, who must’ve seemed so mature and unattainable to a nerdy teenage boy).

It goes back to what I said about this being an affectionate, feel-good movie where everyone turns out to be pretty decent in the end. It doesn’t set out to be much more than that, and I’m not sure if I wanted it to be, but I think it’s that fact they didn’t go all out that keeps it from being a 10/10 for me. It’s just very sweet and knowing and funny and always making sure to laugh with these oddball kids, but that same gentleness keeps it from being something great; it’s like you need some claws to expose something “real”.

It’s a little strange to me, for example, that the movie dishes out a lot of high-school tropes — all the kids are playful representatives of some stereotype — but doesn’t seem to have any real bullies, and happily accepts the two not-very-outcasted outcasts at the party with open arms. And the girls each get their heart crushed, but only for like five minutes before they (tbqh) each get an upgrade. Every Gen Z tribe gets represented — from the failing stoner who actually has an offer from Google to the misunderstood school slut to poor Jared, my sweet beautiful mess of an unloved richboy — in this kind of Glee grab-bag kinda way, but without Glee’s sense that what ties us all together is this fucking shared suffering called high school; Booksmart’s high school is more like a utopia where everyone wears what they want and gets to be quirky and different and much cooler than you think in their own individualistic way. (They even have Jessica Williams as a teacher! UGH, so jelly.)

There’s something that’s actually really subversive about this, because 1) no one’s a villain and 2) to the extent that Molly and Amy are unpopular, it’s kinda brought on by themselves. *They* were the ones who chose never to hang out with the other kids, because studying was more important. *They* are the ones who have to learn something. Molly was the one who judged everyone by the school they got into, even as the others never gave a shit about it. Amy came out two years ago, but the reason she’s never had a kiss isn’t so much because she’s a lesbian, but because she’s too timid and unassertive as a person. Molly’s character arc is discovering that she’s too freaking judgey and she needs to stop assuming she knows everything from the cover, Amy’s is to realize herself as her own person outside of the (admittedly powerful) centrifugal force of her best friend.

Those are GREAT ideas for arcs, it’s just that the execution of them didn’t completely land for me — maybe because the jokes were competing so much with the serious bits for screentime, it had to scramble at the end for the moment of character growth. So it didn’t feel fully “earned” to me, even as it worked on the thematic level of truly seeing people when you aren’t blinded by your own assumptions.

Still, it’s a really satisfying movie with a different take on a common trope, and packed with killer lines and secondary characters like Jared that are just so great (he’s one that feels especially on-point to me because I recognize one of my old classmates in him — a great kid, just… swimming through life in a different lane). The cameos by the adult actors — Jessica Williams, Lisa Kudrow, Jason Sudeikis, Will Forte — were predictably fantastic. In fact all the acting and casting was SO GOOD (I found out later that the casting director was the one who did Freaks and Geeks!). I’m impressed by Olivia Wilde in her directorial debut here, it’s clear that she has an ear for comedic beats and some of the shots were wonderful — in a lot of comedies the camera is just kinda static and it’s all talking heads, but here the angles, the POV shots, the longer takes that move in and out of sound add so much dynamism. Excited for what she does next.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

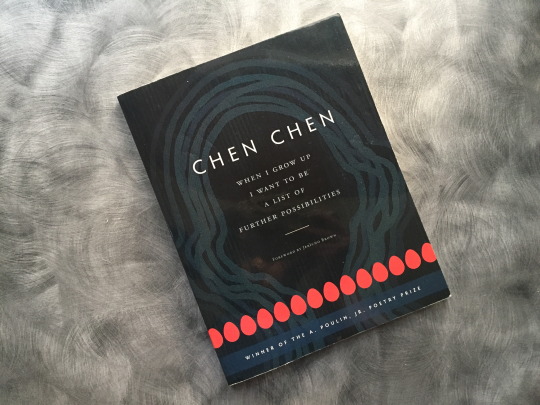

Conversation: Chen Chen Writes.

Congratulations to Chen Chen, whose When I Grow Up I Want to Be a List of Further Possibilities was longlisted in the Poetry category of the 2017 National Book Award!

In honor of the publication, which also won the A. Poulin Jr. Poetry Prize, we are now releasing the full version of the interview we conducted with Chen for Issue #5 of sinθ magazine, which was abridged in the print edition. In dialogue with our web editor Emily Chen, the poet discusses the power of lyric and language in activism, lox in a box, & what it means to write in diaspora.

© 2017 Sine Theta Magazine: [available for purchase here]

“I’m no mango or tomato. I’m a rusty yawn in a rumored year. I’m an arctic attic.

Come amble & ampersand in the slippery polar clutter.”

– “Self-Portrait as So Much Potential”

The opening poem in Chen Chen’s debut publication When I Grow Up I Want to Be a List of Further Possibilities, “Self-Portrait as So Much Potential” sets an ambiguous, exploratory tone for the A. Poulin Jr. Poetry Prize-winning collection. At turns contemplative and daring, regretful and irreverent, Chen’s poetry traces themes of family, sexuality, memory, and bitefuls of Chineseness.

A current PhD student in English and Creative Writing at Texas Tech University, Chen is dedicated to voicing the experiences of queer Chinese-American individuals through writing brimming with reflective vision, humor, and love.

Last month, I had the opportunity to speak with Chen about poetry, identity, and his still-baby pug.

Emily Chen: As someone who arrived in the U.S. at a young age, do you feel as though there are unexplored possibilities of who you could have been or become if your connection to Chinese culture was different?

Chen Chen: Great question. And it’s hard to say because hypotheticals like this tend to be idealized; Iend up thinking about all the positive things that might’ve happened, if my parents had decided to stay in China. Like maybe I’d feel more confident in my body image because I’d see so many more people who look like me on screen. Maybe I wouldn’t have internalized white beauty standards at an early age and then have to unlearn, constantly, all these things that make me want to be someone else. Plus, I could always go to a barber who knew exactly how to cut my hair!

But if I really think about this parallel reality, where I grew up in China, I’m sure it’d be much more complicated than I’d initially imagined. I don’t know enough about modern Chinese history to know how I would be shaped and how I would respond to the whole sociopolitical environment there. I’ve visited my extended family, but only during summer breaks. I don’t know what it’s like to live there all the time, as someone who was raised and educated there. So I don’t want to make assumptions.

It would be nice, though, to be able to speak fluent Mandarin and also fluent Xiamenese (a form of Hokkien my whole family speaks). My Mandarin is decent, but I need to seek out more opportunities to practice it.

EC: Languages open doors to the idiosyncrasies of cultures, identities, and creative opportunity. Yiyun Li writes in her essay To Speak is to Blunder, “One’s relationship with the native language is similar to that with the past. Rarely does a story start where we wish it had, or end where we wish it would.” What would you consider your native language, and how has your relationship with it evolved throughout your time as a writer?

CC: So, as I sort of hinted at in my first answer, my first language was Xiamenese and then soon after that, Mandarin. But yeah, I came to the States when I was three and picked up English very quickly. I don’t primarily speak or write in the languages I learned first. I identify with English. I write poetry in English. On occasion, I’ve used Mandarin in my poems, but I doubt I’d ever write entire poems in Mandarin. For me, Mandarin and the tiny bits of Xiamenese I’ve relearned tend to be languages I speak with my parents and relatives.

Recently, though, I’ve wanted to expand and reshape my relationship to a Chinese identity. That is, I’ve wanted to stop thinking so much that my Chineseness is always or primarily tied to my (biological) family. Because I’m gay and my parents have not been very accepting, I’ve had negative associations with being Chinese. My parents have repeatedly expressed the idea that being gay is just a “Western” or “American” thing, which is absurd. They’re doing better these days, but definitely still learning about LGBTQ issues.

The thing is, I know that there are many Chinese and Chinese American people who are also queer or who accept queer people and are allies in the fight against homophobia. So I want to seek out more LGBTQ Chinese and Chinese American community, more accepting and also politically engaged folks. I used to believe I had to choose being one or the other—gay or Chinese—but now I see how these identities and experiences are intertwined, inseparable.

A friend of mine, who also identifies as queer and Chinese American, sent me some LGBTQ-related YouTube videos in Mandarin and I started crying, watching one of them, because growing up I just never heard someone talk about supporting LGBTQ people in this language. I wish these videos had existed before. I’m glad they do now. I don’t want to deny any part of who I am. So maintaining my Mandarin and at least some bits of Xiamenese remains important to me.

EC: You discuss the importance of media representative of different identities, particularly being LGBTQ and Chinese American. What makes poetry, as a form of media, an effective means of activism?

CC: Poetry, at its best, can alleviate or converse with the loneliness of those on the margins. When a high school English teacher introduced me to the work of Li-Young Lee, I realized that Chinese American poets exist—and that I could be one, too. Poetry can also expand and queer our sense of what’s possible for our worlds and futures. The work of fellow queer writers of color constantly moves and delights and pushes me.

All this said, I don’t think poetry alone can tackle the myriad and interlocking oppressions that we face. Collective actions like protests and boycotts and creating our own community spaces are necessary. Poetry can contribute to how we imagine and practice these actions. Poetry can also provide forms of nourishing joy that allow us to rest and to remember why we struggle.

EC: Your poem “First Light” was featured on Sine Theta Magazine’s online arts blog. It includes the lines: “the China of my first three years / is largely make-believe, my vast invented country, / my dream before I knew the word ‘dream’.” How have your conceptions of China and your first departure changed? As part of the Chinese diaspora, how have you come to understand China as a real body of people and political thought?

CC: I read a lot. I took classes in college. I ask my parents and relatives about things. But I still don’t know a lot about China, to be honest. It’s such a big country with such distinct regions with such a long history that I doubt, unless I did another advanced degree and lived there for an extended period of time (maybe), that I’d ever feel like I had a strong grasp on the country as a whole. A part of me just wants to laugh when white classmates or friends ask me something about China because how much do I know, really? I’m still learning and I’ll always be learning. I grew up in the States. I’m very American.

I used to have this deep longing for China, like if I came to understand China, I’d really understand myself. But now I feel like I don’t need China to hold these “answers” to who I am. There’s no final, singular, purely “true” me, ultimately. There’s a big complicated mess and I’m getting more comfortable with the messiness. Writing definitely helps because if I’m writing in an open-hearted way that feels right, the process tends to reveal how messy and ~alive~ life actually is.

EC: That makes a lot of sense. As members of the Sino diaspora, our understandings of the countries that were our homes, or were the homes of our parents, or are the homes of the friends and family we are meant to hold dear are often politicized and influenced by upbringings away from “home.” Why has writing been such a powerful tool for your movement away from nostalgia for China as a foundational part of understanding yourself?

CC: Writing is a way into the scary particular and the vast uncharted and the unchartable unnavigable underside of what I “know.” Every time I sit down to write, it seems impossible, this poetry thing. If I’m doing it right, I don’t know what poetry is and I keep not knowing until the poem seems to know something. I just have to feel a sort of tingle, a kind of itch, a hum, and an hankering for the words to exist. So, the movement away from nostalgia for China and towards a more complicated relationship with homeland and nationality—this movement came about through writing. I couldn’t think my way out or in. I had to write my way through. I still get nostalgic for an imagined place. But now I understand the process—the act of writing—that can dialogue with that nostalgia and that imagination.

EC: Your parents likely have a much different view of and relationship with Chineseness than you do. How has their outlook impacted your portrayal of familial ties and any resultant burdens in your writing?

CC: My parents continue to identify as more Chinese than American, though they’ve spent basically the same amount of time here as I have. Part of this has to do with the fact that they left China when they were already adults—my mother in her mid-twenties and my father in his thirties. I think my mother, though, has been more comfortable adopting American attitudes and ways. My father, for example, still doesn’t like eating salad because he distrusts things that are uncooked. He believes that cold and raw things are bad for you. But maybe that’s just my father and not a “Chinese” thing.

Another reason my parents still identify so strongly as Chinese is that they didn’t really plan to stay in the United States. My father came here to study and my mother and I followed after his first year at an American university. At first the plan was that he’d finish his doctorate within a few years and that’d be it. But the doctorate took much longer and my father also wanted to have more children (this was when China’s one child rule was in full effect) and he wanted us to be educated in the States because he thought that’d make us more competitive and lead to high-paying jobs (surprise, my two brothers and I all became artists/teachers, oops).

The story’s more complicated than this, but I think I’m better at exploring it in poetry. The important facts for the purpose of this interview are: the fact that my father was the one who decided to come and then stay in United States, which led to conflict between him and my mother, who didn’t want these things and took a long time to adjust… and the fact that I, the eldest son, did not turn out the way my parents wanted me to—not just the artist/teacher part, but the gay part. Obviously. So, family has been the source of a lot of tension and sorrow and anger and arguing over fish ball soup.

My book traces these two main conflicts: the one between my father and my mother over moving to America and the one between my parents and me over my sexuality. The latter conflict mostly has to do with my mother and me, because I’m closer to her than to my father, so it’s just a lot more emotionally difficult. And poetry, I’ve found, gravitates toward the unresolved issues, the unanswerable questions. I’ve written happier family poems, too, that celebrate the (messy, messy) people my parents are, and my brothers. I keep returning to the subject of my family, but (I hope) from different angles and with different aesthetic approaches.

EC: Moving to the United States and raising children to both survive the new and remember the old, while doing the same themselves, must have been challenging for your parents. Poetry is a compelling medium of exploration of difficult feelings. Speaking more broadly, how is art useful for breaching generational culture gaps, especially in immigrant families?

CC: I don’t know if my art is useful in this way. I hope it can be. But I do know of a project called “Mother Tongues,” which is one of Kundiman’s amazing projects. As the website puts it, “Mother Tongues recovers diasporic narratives by chronicling the lives and experiences of mothers across three Asian American generations. Interviews, poetry and performances combine to form an archive that documents the triumphs and challenges of building lives in America.” I think this is so important: how the project involves interviews and the voices of Asian American elders.

I find it problematic, the idea that it’s always the younger generation who must tell the stories of the past on behalf of the elders. This idea assumes that the elders can’t speak for themselves—or that any language barrier is just insurmountable. I don’t want to claim that I’m speaking for my parents or for any of my elders, blood or chosen. When I write, I’m very much sharing things from my perspective. And I struggle with this issue. At the end of “First Light,” I shift to my mother’s voice—but I hope it’s clear that I’m constructing my idea of what she would say. The younger generation’s imagination of and engagement with older generations’ experiences is important, but these texts should not be the only ones. I also don’t think we should over-valorize “literary” forms of sharing immigrant experiences. After all, white folks tend to consume (tokenized) writing by immigrant writers and then claim to understand “The ___________ Experience.” Just because something has received a literary stamp of approval doesn’t mean it’s more valuable or true. So, more projects like “Mother Tongues” need to happen. We need more subversive work that questions codified narratives of generational identity and diaspora making.

EC: How does poetry function as an agent of intersecting identity? Why do you think language contains the power to package the odds and ends of something as complex as individuality into a comprehensible, legible thing that can often be shared?

CC: What a beautiful set of questions. Hmm. Well, it occurs to me that language that doesn’t make sense, not complete sense. Like, the spelling of the English language is just a terrible, terrible mess. Sometimes people like to pretend it’s phonetic but it’s really not. I mean, even the word “phonetic” is wonky. How do a “p” and an “h” come together to give birth to an “f”? WTF? Don’t get me started on “night,” one of my favorite words and also bizarre with its silent “g” and “h.” I guess those letters used to be pronounced but then one day they weren’t and yet people just held onto them, anyway? Whatever. Language is super weird, even when you do have phonetic spelling and clearer, firmer grammar rules. And language is weird because people made language and people don’t make sense, not complete sense. But then it makes so much sense, doesn’t it, that language has the capacity to explore and articulate human complexities?

Even if it doesn’t have that capacity (and sometimes I doubt language can really do it all), I still love language. I still love poetry. Specifically, it seems to me that poetry is the weirdest of genres. Probably all writers feel this special way about their genre. But poetry is pretty damn weird. Poetry can open up to complexity, to intersecting identity, to queerness, to the unsayable, to the power structures pinning us down, to a caterpillar who just wants to dance like nobody’s watching, to a kiss on the forehead of the drunken sea.

EC: What inspires?

CC: Anything. Last night I was at the supermarket and saw this product called “Lox in a Box.” Meaning: lox, with everything you need to consume it with delight, including cream cheese, crackers, a knife, and a napkin. The box said, “Ready where you are, work or play.” A poem is a sort of “lox in a box”—ideally, everything you need to experience the wackiness of life, plus a napkin (printed poems can double as this; online poems not so much; I love reading poetry online though; online journals are the bomb).

EC: Oftentimes, the poetic themes derived from past experiences, trauma, and failures can hinder the creative process with the magnitude of their emotional impacts. How do you overcome memory and employ it in writing?

CC: I tend to wait until I have enough distance from an experience that I don’t feel so overwhelmed trying to write about it. Or, I write about something closer to the actual event because I feel a pressing need to do so, and then I wait before revising it and finally sending it out to journals. The oldest poem in my book, the long narrative poem in section one called “Race to the Tree,” started as some not-great drafts in college. I felt like I finally knew what I needed to do with that poem in the middle of graduate school, three years later. Then a year after that, following further revision, it appeared in my first chapbook, in 2015. And now it’s in my book, after more revision. I was revising “Race to the Tree” up until the last minute, when I had to turn in my final version of the book manuscript to my publisher.

That poem—about the night I almost ran away from home after a physical fight with my mother over my queerness—was one of the most emotionally difficult for me to write. So, returning to it was hard, but it did get easier over time. I don’t think there are any shortcuts to this process, if you’re writing something that deeply matters to you. You just have to be patient and make the mistakes you need to make and trust that the poem is smarter than you are and taking you where you need to go. Having smart and compassionate readers by your side helps, too.

EC: I remember reading “Race to the Tree” for the first time so long ago! Do you find that, as you temporally move away from the experience itself during long-term revision processes, the outlook and perspective of the writing change?

CC: Definitely. Sometimes I forget what I was going for in a piece and that can be good. A new trajectory arises. Other times I feel too distant from the originating spirit of a poem and then I might over-revise or revise out something crucial. It can be difficult to tell what my precise relationship to a poem is, after a long “break” from it. We have to sit down again, poem and poet, ideally over some oolong tea. We have to re-establish trust and openness and rhythmic giddiness. I have to explore the person and the writer I’ve become. Often this means creating a poem that looks like a horrid lampshade or revising an older poem into an unrecognizable beast. I try to remind myself, though, that growing as a writer means getting uncomfortable, over and over. I still freak out. A lot.

EC: For whom and for what do you write?

CC: I’m trying to write for other LGBTQ Asian Americans and in particular other young gay Chinese American men whose families have disapproved of them. Maybe that seems like a small subset of my potential audience, but I think it’s white supremacist ideology that always tells us that and wants us to believe that white cishet men should have every work of art and bit of representation cater to them. Also, I don’t think my writing is as alive when I think about a big, general audience. For my process, it’s better that I think I’m writing for myself or to a good friend. I want that intimate and vulnerable voice to come through. If other folks want to listen in, too, that’s great.

EC: Writing for a specific group of people can be challenging, since others will inevitably consume it as well. Are you ever worried that people who are not LGBTQ Asian Americans may view or share your work in ways that detract from the narrative of the struggles of your own identity and the collective struggles of queer Asian Americans?

CC: The way I try to think about audience is that maybe the general audience won’t understand everything I’m trying to do and that’s okay. They’ll still understand a good amount—and this seems to be the case with the reviews and the overall response I’ve gotten so far. And then maybe the more specific audience of LGBTQ Asian Americans will understand more or understand differently or maybe not. I don’t really know. But I want to write with LGBTQ Asian Americans in mind and heart and language. I want to communicate something specific.

Some reviewers have said that I do the thing where poetry reaches the universal through the particular. I don’t think I believe in the universal or in universality, at least not as some free-floating, ahistorical and apolitical ideal. Too often, the “universal” is equated with how much a text appeals to white cishet people and mainly white cishet men. Like, “oh this book is about a trans woman of color but actually it’s about human beings!” Um, no. Saying a book is about a trans woman of color is already saying it is about humans.

As I say in a poem toward the end of my book, “I already write about everything.” I’d rather keep asking the question, “Why is this book about sad white people in suburbia supposed to be automatically universal?” I’d rather keep writing the poems I need to write than give a damn about readers who want to stay boring.

EC: How has the release of When I Grow Up I Want to Be a List of Further Possibilities into literary consumption affected your feelings about the compilation? Does knowing that others read, analyze, and interpret your work with their unique lenses change how you view your own writing?

CC: I try not to think about reviews or other people’s perceptions of my first book while I work on the new poems. But of course, I can’t help thinking of all that, to some degree. I try to listen to the reviews and comments that I find useful for pushing me further in my writing practices. All the reviews so far have been super positive, but the ways in which some reviews hone in on certain aspects of my work are helpful. Like when a review highlights my anaphora, as a strength, I think 1) it’s great that they noticed I was employing that device for intentional effects, 2) maybe I should cut back on using anaphora so much, 3) if I use anaphora again, I should use it in a very different way.

My favorite reviews have been by fellow Asian American poets. In particular, Michael Schmeltzer’s review in International Examiner (which is also an Asian American publication!) and Victoria Chang’s review in Tupelo Quarterly. I appreciate how they both get at the heart of my book and seem to understand it on a deeply felt level. The way Schmeltzer discusses my “dream-logic” and my politicized sense of humor is so precise and delightful. And I love the way Chang discusses my relationship to traumatic memory and how the book circles back to the scene first introduced in “Race to the Tree” (and further explored in poems like “First Light” and “Poplar Street”). These reviewers make me feel like I really said what I needed to say with this book. They also make me feel like I should keep leaning into writing for Asian Americans. Reviewers who identify in other ways have picked up on these aspects of my book, but it moves me so deeply to see Asian Americans understand and enjoy these poems. Also, Schmeltzer and Chang are phenomenal writers themselves; their talents show in their reviews, too.

I grew up feeling lonely; I had few Asian American friends in high school. The other Asian Americans I met didn’t seem interested in writing. Or, sometimes, I didn’t want to be friends with them because I was afraid they would be homophobic, like my parents. So it means a lot to me, to be in the company now of Asian Americans who also love poetry and who are writing so thoughtfully and beautifully about my poetry. I’m filled with a joy I didn’t think possible.

EC: What should we await from you this coming year?

More issues of Underblong, the poetry journal I edit with my bestie, Sam Herschel Wein.

Sam and I are also working on a joint chapbook called Gesundheit! & other poems. We keep talking about going on tour eventually and the tour will be called Achoo and at the end of readings we’ll say Bless you to the audience. But first we have to finish editing the collection!

I’m also working on poems—a lot of prose poems, in fact—for a second full-length collection, tentatively titled Your Emergency Contact Has Experienced an Emergency. I just love sentence titles and long titles. This one’s a bit shorter, though, which will probably be a relief to the cover designer.

EC: Finally, and undoubtedly most importantly, how is Mr. Rupert Giles doing?

CC: He’s doing very well, thank you for asking! He’s just over a year old now and has all this way-too-excited puppy energy (Mr. Rupert Giles is my pug dog, in case readers are wondering; and yes, he is named after the British librarian dude from Buffy the Vampire Slayer). My partner Jeff and I went to PetSmart today and it was clear from the hyper-giddy way Mr. Giles was wagging his tail and sniffing everything that he wanted us to buy ALL THE FOOD and ALL THE TREATS.

Design by Elisabeth Siegel

Photograph by Emily Chen

Interview conducted by Emily Chen

Sine Theta Magazine is a print-based, creative arts magazine made by and for the Sino diaspora.

PURCHASING OPTIONS:

BLURB

TICTAIL

More issue information available at sinetheta.net/5.

Instagram | Facebook | Blog | Donate | Submissions guidelines

#chen chen#asian american poetry#asian american literature#lgbt asian americans#lgbt poetry#issue5#ec

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

How Love, Victor Accurately Portrays The American LGBTQ Experience

https://ift.tt/eA8V8J

This article contains spoilers for Love, Victor season 2.

When it was announced that the iconic 2018 rom-com Love, Simon would receive a spinoff TV series, many worried it wouldn’t be able to find its own unique portrayal of sexual orientation awakening. In the hands of thoughtful showrunners Isaac Aptaker and Elizabeth Berger and the endearing lead performance from Michael Cimino, Love, Victor is able to cast a wide net of LGBTQ perspectives for the audience to learn and connect to.

That’s why Hulu’s teen romance series has developed a niche, but rabid fanbase in the past year. As an audience, getting to follow along with Victor Salazar (the aforementioned Cimino) on his journey has been an honest and raw reflection of so many viewers’ experiences with their own sexuality. With the second season having premiered on June 11, excitement has been building to see where the title character goes now that he has a boyfriend and has come out of the closet to his family.

No piece of media can ever be an all-encompassing overview of one group’s experience, but this show has really turned into a unique survey of the gay landscape, from sexual questioning, to sexual awakening, self-acceptance, and finally learning to live in a world where others don’t respond well to you being your true self.

There are many stereotypes in media about what it means to be gay, and too often they depict a white, upper-middle class character with family and friends who have no qualms about queerness. The happy-go-lucky approach does not show outsiders just how tumultuous and heartbreaking it often is to grapple with being non-straight. Love, Victor engages the viewer and invites them to learn about a wide variety of LGBTQ struggles. Victor is Latino, lower-middle class, Catholic, and dealing with the upsides and downsides of being a gay man who skews more masculine than feminine.

Victor has internalized homophobia throughout the first season, taking awhile to figure out that it is indeed okay to like men, no matter what his conservative Latinx parents have taught him in the past. When he reveals his sexuality to his mom and dad in the second season, the audience is treated to the juxtaposition of the parents’ differing reactions. Victor’s father has an easy time putting his love for his son ahead of his ingrained value system; Victor’s mother has a much harder time grappling with whether to put her religion or her son first, but the payoff in that journey is something to behold (and will make you cry). This decision from the writers gives the show a way to relate to the widest array of watchers in the target audience, and shows that love can trump bigotry if you have a decent heart and adore your family.

Arguably the most tasteful analysis the show pulls off is its depiction of the limbo you are placed in as a gay person, particularly a gay man, where you are stuck between two different worlds based off of your gender expressions. Victor is traditionally masculine, one of the stars of his high school basketball team, yet his teammates feel uncomfortable with him in the locker room. For those who think this type of homophobia is an outdated trope, take a peek at any of the comments on social media at the beginning of Pride celebrations when any male sports teams lend their support to the equality movement. To a sizable portion of the population, being gay is still synonamous with being less masculine, and Victor feels the pain of his being outcasted from the guys he hoops with in a very raw way.

He then quits the team in the third episode of the second season, only to be poked fun of for being a “former, straight-acting jock” by his boyfriend’s gay friends. In one of the most revelatory lines in the whole series, Victor asks his teammate Andrew (played by Mason Gooding), an eventual ally, what is the perfect amount of gay to satisfy everyone? Too gay to play sports and not gay enough to hang out with more traditionally queer folk, where exactly is he supposed to turn to find his true family? This question is the most daring one that Love, Victor asks of its audience. The show expects you to examine your own opinions on gender norms and expressions regardless of sexual orientation, and teaches everyone that there is no one way to structure your identity. Victor as a character is a canvas for a myriad of interests and personalities, demonstrating the diversity of the Western LGBTQ+ experience.

This variety is also dissected in what is likely to be the most controversial storyline of the latter half of season 2, when new character Rahim (played by Anthony Keyvan), a closeted classmate of Victor’s, reaches out for some support. As Victor’s relationship with Benji (played by George Sear) starts to go awry, Rahim becomes a confidant, a close friend, and possibly something much more than that. The love triangle that develops as the finale closes will irk many viewers, but that might be in line with the writers’ intentions.

Benji represents many of the privileges that exist in pop culture with gay men: white, rich, and possessing socially liberal parents, he doesn’t fully understand many of the hardships in Victor’s life. On the other hand, Rahim is an Iranian Muslim, with enough flamboyance to match well with much of Victor’s traditional machismo. They are kindred spirits in many ways, and all of their different gayness meshes in a way that is aptly described by Rahim as “magical”. Comparing and contrasting a mixed race relationship (white person with a racial-minority person) with one where both parties are non-white gives the audience a lot to chew on. All of the intricacies of race, gender expression, and sexuality intertwine when Victor and Rahim are together, forcing the narrative to dig deeper and making the show something truly special.

The sheer amount of side characters and the short runtime (each episode clocks in at around 30 minutes each) leaves some stories feeling a little rushed, which would be one of the only flaws in the show’s exploration of teenage sexuality. With the time that is given, you don’t always get the full picture on the peripheral of the main plot, but relationships like Victor and his best friend, Felix, and the bond that he shares with his ex-girlfriend, Mia, are also valuable to the portrayal of a gay man’s inner circle.

Victor and Felix (played by Anthony Turpel) are a beacon of hope that a gay man and straight man can remain as tight after the coming out process as they were before. There is no sexual tension and absolutely no insecurities from Felix that Victor may come on to him; the latter issue is one of the preeminent reasons so many queer people have for holding off on being themselves, as they don’t want their friends to view them any differently than before (I, for instance, had an aunt who dropped one of her longest friendships when she found out the woman was a lesbian). They talk about their sex lives, go to each other for relationship advice, and just have a whole lot of fun; they’re bros (or bone brothers, according to Felix). Victor and Felix do not represent the majority of gay/straight friends, rather they portray the idyllic potential of this scenario in a world that will hopefully become fully comfortable with it some day soon.

As the first season came to a close, Mia (played by Rachel Hilson) is heartbroken after Victor cheats on her in the process of figuring out his sexuality and the showing of her forgiveness in the second season is one of the highlights of the series. Gay men keeping their friendships with ex-girlfriends after coming out is a common stereotype, but it’s rarely shown with such tenderness as in this series. The Victor/Mia bond demonstrates the ways platonic love can be so powerful it can confuse those engaged in it. This makes figuring out one’s sexuality even more confusing for many in the LGBTQ community, and the interpretation of this trope is very warm as seen in these two characters.

When making a TV show that represents a group of people who have been traditionally discriminated against, it is not enough for the characters to simply exist; these folks need to be a reflection of the society that they are fictionalizing. Unfortunately, depictions of the LGBTQ community on screen have long been restricted to one-dimensional sidekicks (the Gay Best Friend trope, examined perfectly here by The Take) and cheap stereotypes (Carol on Friends was used to insult Ross’s masculinity, insinuating that he turned her lesbian because he wasn’t man enough for her).