#Floyd United Methodist Church

Text

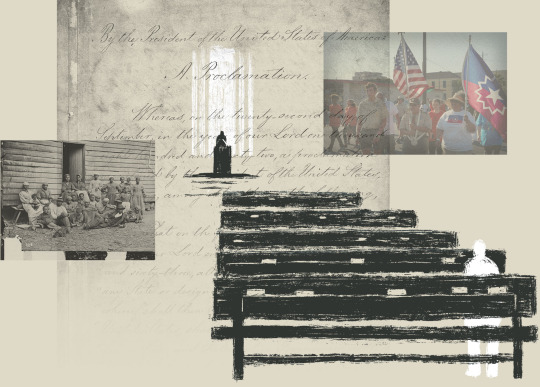

The cottonfields of Georgia were once worked by the enslaved. REUTERS/Tom Lasseter

WASHINGTON

We sat in the pews of a Methodist church last summer, my family and I, heads bowed as the pastor began with a prayer. Grant us grace, she said, to “make no peace with oppression.”

Our church programs noted the date: June 19, or Juneteenth, the day on the federal calendar that celebrates the emancipation of Black Americans from slavery. The morning prayer was a cue.

The kids were ushered from the sanctuary to Sunday school. My sons – one 11, the other 8 at the time – shuffled off to lessons meant for younger ears.

The sermon, delivered by a white pastor to an almost entirely white congregation, was headed toward this country’s hardest history.

“We are a nation birthed in a moment that allowed some people to stand over others,” she said from the pulpit, light flooding through the stained glass behind her. “We’ve all been a part of taking what we wanted. White people, my community, my legacy, my heritage, has this history of taking land that did not belong to us and then forcing people to work that land that would never belong to them.”

The pastor did not know that I was months into a reporting project for Reuters about the legacy of slavery in America. It was an idea that came to me in June 2020, shortly after returning to the United States after almost two decades abroad as a foreign correspondent.

We had moved to Washington just 18 days after George Floyd was killed by a white police officer in Minneapolis, and in our first weeks back, I found myself drawn to the steady TV coverage of protests from coast to coast. I read about the dismantling of Confederate statues on public land – almost a hundred were taken down in 2020 alone. I thought about my own childhood, about growing up in Georgia. And I wondered: Had this country, which I had yet to introduce to my sons, ever truly reckoned with its history of slavery?

REUTERS/Photo illustration REUTERS/Photo illustration

I wondered, too, about our most powerful political leaders. How many had ancestors who enslaved people? Did they even know? I discussed the idea with my editors, who greenlighted a sweeping examination of the political elite’s ancestral ties to slavery. They also raised another question: What might uncovering that part of their family history mean to today’s leaders as they help shape America’s future?

A group of Reuters journalists began tracing the lineages of members of Congress, governors, Supreme Court justices and presidents – a complicated exercise in genealogical research that, given the combustibility of the topic, left no room for error.

Henry Louis Gates Jr, a professor at Harvard University who hosts the popular television genealogy show Finding Your Roots, told me that our effort would be “doing a great service for these individuals.”

“You have to start with the fact that most haven’t done genealogical research, so they honestly don’t know” their own family’s history, Gates said. “And what the service you’re providing is: Here are the facts. Now, how do you feel about those facts?”

And there was more to the project, something I needed to do, if only out of fairness. As a native of Mississippi who grew up in Georgia, I would examine my own family’s history. A passing remark made by my grandfather long ago gave me reason to believe my experience wouldn’t be as joyous as the advertisements I saw for online genealogy websites. Instead of finding serendipitous connections to faraway lands, I suspected I would find slavery on the red clay of Georgia.

But all of that was for work. It wasn’t for Sunday church, I thought, sitting next to my wife. My mind wandering, I looked down at the Rolex on my wrist.

This is the story that I tell myself: Those are things that I earned, paid for with hard work. I am a high school dropout. My mother is a high school dropout. My father is a high school dropout. My sister is a high school dropout. My first home was in a southern Mississippi trailer park. My mother was pregnant with me at the age of 19. My dad left our lives early.

I got my GED. I moved from a community college to the University of Georgia, working as a short-order cook while earning a bachelor’s degree in journalism.

For me, church is a place that offers a soothing sense of order, of ritual. That morning, I didn’t feel comfortable. I resented the pastor. I was there to listen to the choir and contemplate a Bible verse or two, not to be lectured. Especially about a subject I was grappling with personally and professionally.

“We would swear with our last breath that we do not have a racist bone in our bodies,” she continued. “But some of us were born in a lineage of people who take land that is not ours and enslave other people.”

Her words would come close to the facts that my reporting surfaced in the months ahead. Still, on this Juneteenth, I was done listening.

After the service, I walked to the car with my wife and sons. I didn’t talk with them about the sermon as we headed to our home on the outskirts of Washington. Ours is a street of rolling green lawns and shiny Cadillac Escalades. On the edge of the U.S. capital, a city where some 45% of the population is Black, the suburb where we live is about 7% Black. It was an inviting place for a white man to escape the pastor’s message.

That cocoon soon started to unravel. I had begun a journey that would take me back to places I held dear but had not truly known. What I would come to learn in researching my ancestors didn’t tarnish my love for family. At times, though, I did worry that I was betraying them.

It also left me with two questions I have yet to answer. What do I tell my sons about what I found, and what does it say about their country?

Introducing America

Throughout 2022, our reporting team assembled family trees for Congressional members. We connected one generation to the previous, like puzzle pieces snapping one to another, extending years before the end of the U.S. Civil War in 1865. We learned to decipher census documents written in sometimes bewildering cursive. Enlisting the help of board-certified genealogists, we became comfortable with the types of inconsistencies that surface in the old papers: names slightly misspelled, ages off by a few years, children who disappear from households as they die between censuses or marry young.

For months, my attention was drawn to the complexity of the task, and I scoured websites for documents that went beyond census records: certificates of birth, death and marriage, obituaries, military service forms, family Bibles.

The work was painstaking, and a welcome diversion. Each time I thought about building out my own family history, I winced at the subject coming close. Those were my people, my history.

Eventually, I knew I had to get started.

My wife and I were born in America. Both of us are journalists. We met in Baghdad, there to cover the war in Iraq. We married later while living in Russia, had our first son in China, our next in India. After two years in Singapore, we decided it was time to take the boys home to America, a land they’d visited on summer trips to their grandmothers’ houses in Georgia and Virginia but hardly knew.

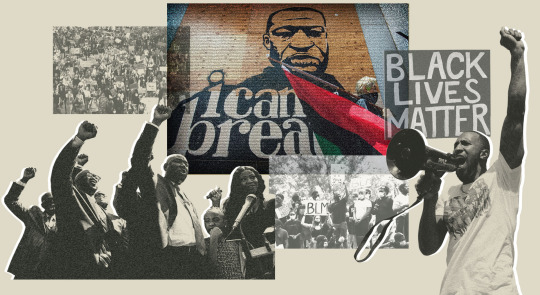

Their introduction began less than three weeks after the May 25 death of George Floyd, as soon as we rode in from the airport. As we approached shuttered stores and boarded-up windows in downtown Washington, our younger son looked at the graffiti and banners and asked what the letters BLM stood for. My wife and I spelled it out – Black Lives Matter – and told him about Floyd’s death. Six at the time, he had no idea what we were talking about. His older brother explained the protests were to help Black people. Then he reminded him that their uncle, my sister’s husband, is Black. Our little boy went quiet. In the wake of George Floyd’s killing, protesters took to the streets across America.

REUTERS/Photo illustration In the wake of George Floyd’s killing, protesters took to the streets across America. REUTERS/Photo illustration

Last spring I began to trace my family’s lineage in detail. I had gone through this process for dozens of members of Congress. Now I was looking at my own mom. As I started a family tree, I did not like typing her name – it felt like I was crossing a line. I opened the search page at Ancestry.com and entered the names of her parents, Harriet and Brice.

Brice was 69 or so when he visited us in Atlanta during the summer of 1994. I was a teenager. Joseph Brice James was my grandfather, but we just called him Brice. Like my own father, he hadn’t been part of our life. He lived in Chicago and had worked as a traveling salesman. The trip may have been one last effort by him to connect. He wasn’t well and would die about eight years later.

It would be that visit – really, just one line that Brice muttered – that came back to me in the summer of 2020 and started my own personal reckoning.

My Grandfather’s Words Joseph Brice James. (Courtesy: Tom Lasseter)

Here’s what I remember: Brice wanted to see the farm where his ancestors, our ancestors, lived. My mother drove, and my sister and I sat in the backseat of our family’s aged Toyota Corolla. The address Brice helped direct us to was about an hour out of Atlanta. My mother had been there before, too, but my ancestors had sold it off, parcel by parcel, starting around 1947. We pulled over in front of a clapboard farmhouse.

I wasn’t sure why we were there, or who might have once lived on the farm. Brice, a gaunt figure with closely cropped hair and large glasses, didn’t volunteer much. I walked alongside him in silence, across a field spotted with pine trees, on the edge of a lake. Then Brice paused, flicking his wrist toward an old well and said: “The slaves built that.” A moment passed and he kept walking, offering nothing further.

Those four words stayed with me, though, in the way that happens with some white families from the South: I now knew, if I wanted to, that somewhere in my history there was a connection to slavery. The farmhouse in Georgia, once owned by the ancestors of Reuters journalist Tom Lasseter.

REUTERS/Tom Lasseter

Where to begin? Before prying into Brice’s side, I decided to look somewhere more familiar. The census shows my mother’s maternal grandmother as Cornelia Benson. I grew up calling her Grandma Horseyfeather, a nickname given her by my mother’s generation, the product of a long-ago children’s tale.

Looking at the 1940 census, there was Cornelia Benson of Brooks County, Georgia. I knew Brooks County as a place of Spanish moss, where we caught turtles and lizards in my childhood. I loved Thanksgiving at 618 North Madison Street, where a dirt driveway led to the back stairs and then a kitchen with long rows of casseroles. Grandma Horseyfeather, born in 1898, spoke in a slow, deep drawl. She wore lace to church. I adored her and I adored Brooks County.

At home in Atlanta, I felt lost at times, my single, working-class mom stretching one paycheck to the next. But in Cornelia Benson’s house, I felt at ease. My identity was simple: I was a white kid descended from generations of white people from the deepest of south Georgia.

As a child, I did not ask what it meant to belong to a place like Brooks County. Now I wanted to know. Cornelia Benson with Tom Lasseter as infant (left); Tom Lasseter during a childhood visit to Quitman, Georgia. (Courtesy: Tom Lasseter)

A story came to mind. I was young, and the grownups were visiting at the dining table. Someone started to tell a story about life in Quitman, the town in Brooks County where Grandma Horseyfeather lived. It was about the Ku Klux Klan and its marches.

The Klan would saunter down the street, wearing hoods and sheets, thinking no one knew who they were. The story’s punchline: All the “colored boys” – meaning Black men – knew who was wearing those sheets. They could see the shoes the white men were wearing. And who do you think shined those shoes?

I remember a tittering of laughter ripple around the table.

It was a vignette I sometimes trotted out when discussing the South. I’d shake my head and show a rueful half-frown that communicated disapproval, but not too much. My Brooks County relatives didn’t quite fit the pastor’s words. I knew they had some racist bones in their body. Still, these were my people. They didn’t mean any harm.

Reading back over the story after I wrote it down last year made me wonder what I didn’t know. So I did something that had never before occurred to me: I looked up the history of Brooks County, Georgia. It did not lead anywhere good.

In 1918, at least 13 Black people were killed in a rash of lynchings by mobs in Brooks that cemented its reputation for bloodshed. A flag that hung from the NAACP national headquarters in New York City, 1920-1928 (Source: NAACP via Library of Congress). Lynchings in Brooks County, Georgia, in the early 20th century cemented its reputation for racism and bloodshed.

REUTERS/Photo illustration

“There were more lynchings in Brooks than any county in Georgia” at the time, according to a 2006 paper examining lynchings in southern Georgia. Among the 1918 victims: Near the county line, a pregnant woman was tied to a tree and doused with gasoline before her belly was slit open with a knife and her unborn child tumbled to the dirt. The woman was shot hundreds of times, “until she was barely recognizable as a human being.” And then both her and her fetus’ burial spots were marked by a whiskey bottle with a cigar placed in its neck, according to the paper – “Killing Them by the Wholesale: A Lynching Rampage in South Georgia” – published in The Georgia Historical Quarterly.

I toggled my Internet browser to census records. Cornelia Benson and her husband weren’t yet living in Brooks County as of the 1920 census. They moved there between 1920 and 1930. I felt relieved, clean. I didn’t know any of that history. No one had told me.

But the more I learned, the more I played out the possibilities, the more troubled I felt about the Ku Klux Klan anecdote.

One morning in my home office, I pulled out a cell phone to record my thoughts about those memories. As I did, I heard the wood floorboards creaking. It was one of my sons walking outside the room. I waited for him to go downstairs before starting. When I later listened to my recounting of the Ku Klux Klan story, I noticed I’d used the phrase “Black people” rather than “Colored boys.” Without thinking, I’d cleaned the story up around the edges, making it easier to tell.

‘Mules, Oxen…and The Following Negroes’

Brice died in 2001. I never learned anything else from him about that well on the property our ancestors owned. Having read through the Brooks County material, it was time to see what I might find out about Brice’s side of my family.

I knew my grandfather was born in Canada, but that his side of the family was somehow connected to that land in Georgia. Using Ancestry.com, I found a 1948 border crossing document for him, with the names of his father and mother. I took those names and found his parents’ 1921 marriage license in Fergus County, Montana.

I noticed that his mother’s maiden name was Lila M. Brice, and that her parents were Ethel Julian and Joseph T. Brice. I looked for Ethel Brice. There she was, in the 1910 census. She was living with her daughter Lila in Forsyth County, Georgia, after a divorce – back in the household of her father, a man whose name I had never before heard: Abijah Julian.

The trip to the farm house in 1994 was in Forsyth County. The old clapboard house was built in the 1800s. And the well that Brice mentioned, the one that he said enslaved people built, sat right next to the house.

From one census to the next, I followed Abijah, a name from the Old Testament.

Information about the Julian family wasn’t hard to find once I started looking.

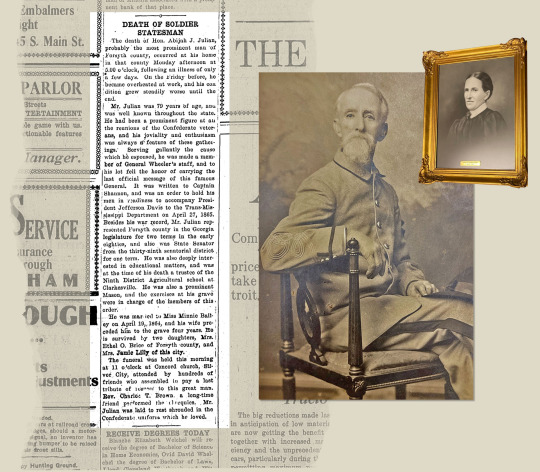

Working my way backwards, I learned Abijah Julian died in 1921. His passing was marked in The Gainesville News by an item headlined “DEATH OF SOLDIER STATESMAN.” Placed high in the article was the fact that Abijah Julian was part of a Confederate cavalry general’s staff during the Civil War, and that in his later years he “had been a prominent figure at all the reunions of the Confederate veterans.” The piece ended with these words: “Mr. Julian was laid to rest shrouded in the Confederate uniform which he loved.” Abijah Julian, seated, was buried in a Confederate uniform. In an account by his wife, Minnie Julian, she described him returning from war “broken in health and spirit. Negroes free, stock stolen and money – Confederate – valueless.” (Sources: Historical Society of Cumming/Forsyth County, Georgia. Newspaper clipping: The Gainesville News, June 1921)

He had served in Georgia’s state legislature for three terms. I looked for more details about him and his ancestors before the Civil War.

Abijah’s father, also a member of the state legislature, died in 1858 at home in Forsyth County, according to press reports. It was just a couple months before Abijah’s 16th birthday.

Some four years later, Abijah went to war against the United States. In 1864, a year before the Civil War ended, he married a woman in Alabama, the daughter of a doctor, who moved to the Julian farm. In an account by his wife, Minnie Julian, she described Abijah returning home after the war, “broken in health and spirit. Negroes free, stock stolen and money – Confederate – valueless.” In the very next sentence, however, she noted they still had 600 acres of land.

Her words signaled that Abijah had enslaved people. But I needed more proof.

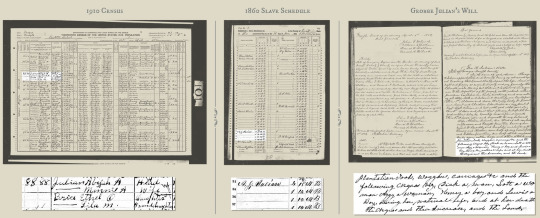

In addition to the usual household census forms, in 1850 and 1860 the U.S. government created a second document for the census takers to fill out in counties in states where slavery was legal. It’s referred to as a slave schedule, and it lists by name men and women who enslaved people, under the column “SLAVE OWNERS.” The form gives no names of the human beings they enslaved. Instead, it tabulates what the document refers to as “Slave Inhabitants” only by the person’s age, gender, color (B for Black or M for Mulatto, or mixed race) and whether they were “Deaf & dumb, blind, insane or idiotic.”

After you find a slaveholder on the household census form, matching them to the slave schedule can be complicated. In some counties, multiple men of the same or similar name enslaved people. And of course, not every head of household in a county enslaved people, so fewer names are listed on the slave schedule than on the population census. Fortunately, the households on the two documents are typically listed in the order they were counted by the census-taker – meaning if you see the same residents’ names close by, in the same sequence, you’ve likely found the same person on the two forms.

In 1860, on a slave schedule in Forsyth, I found my ancestor listed on line 34 as A.J. Julian. He was 17-years-old at the time. There were four entries for his “Number of Slaves” column – four males, ages from 10 to 18.

There was more. When Abijah’s father, George Julian, died in 1858, he left a will.

One key to unlocking the identities of those who were enslaved is through the estate records of white families who claimed ownership of them. In many cases, wills give the first names of the Black men, women and children bequeathed from one white family member to another.

In his will, George listed property “with which a kind providence has blessed me.” To wife Adaline, George bequeathed “mules, oxen, cattle, hogs and other stock, and plantation tools, wagons, carriages and the following Negros…”

There were five enslaved people left to George’s wife, the will said, with the provision that “the negros and their increase” – that is, their children – would go to Abijah after his mother’s death. George Julian also left four enslaved children to Abijah, himself a teenager at the time.

And, in a separate item, Julian wrote that an enslaved woman and three children should “be sold” to pay his debts.

The will was difficult reading. Lumped in with oxen and kitchen furniture, plantation tools and wagons, were human beings. And “their increase.”

The will listed names of the enslaved kept by the family: Dick, Lott, Aggy, Henry, Lewis, Ellick, Jim, Josiah and Reuben.

The document was dated 1858 – close enough to emancipation that I might have a chance at tracing some of them forward, especially if they used the last name Julian. Perhaps there would be a chance of finding those same names in Forsyth in the 1870 census, when, finally free, Black people were listed by name and household.

Something kept happening, however, when I looked for those names. I’d see likely matches in one or two censuses, and then they disappeared after the 1910 census in Forsyth.

It took me a few minutes of research to figure out why I was losing track of the descendants of the people George Julian enslaved. It was a history drenched with blood, and it drew much closer to mine than I had realized.

The Search for Descendants of The Enslaved

ATLANTA

In 1912, Virginia native Woodrow Wilson became the first Southerner since the U.S. Civil War to be elected president. And the white residents of a county in Georgia, where my ancestors lived, unleashed a campaign of terror that included lynchings and the dynamiting of houses that drove out all but a few dozen of the more than 1,000 Black people who lived there.

The election was covered in the classrooms of the Georgia schools I attended. If the racial cleansing of Forsyth County was mentioned, I didn’t notice.

That history explains the difficulty I had looking for the descendents of the people enslaved by my ancestor Abijah. By 1920, their families and almost every other Black person had fled the county.

From left: The Forsyth County Courthouse in Cumming, pictured in 1907. Built in 1905, it was destroyed by fire in 1973. (via Digital Library of Georgia). The Atlanta Georgian newspaper reports on the lynching of Rob Edwards, September 10, 1912. (Source: Ancestry.com). U.S. President Woodrow Wilson.

They were forcibly expelled under threat of death after residents blamed a group of young Black men for killing an 18-year-old white woman in September 1912. A frenzied mob of white people pulled one of the accused from jail, a man named Rob Edwards, then brutalized his body and dragged his corpse around the town square in the county seat of Cumming. Two of the accused young Black men, both teenagers, were tried and convicted in a courtroom. They too died in public spectacle, hanged before a crowd that included thousands of white people.

There were also the night riders, white men on horseback who pulled Black people from their homes, leaving families scrambling and their houses aflame. The violence swept across the county, washing across Black enclaves not far from the farm where my ancestor, Abijah, lived at the time.

In 1910, the U.S. Census showed 1,098 Black people living in Forsyth. Ten years later, the 1920 census counted 30.

‘Night Marauders’

Until last year, I had never heard of this history. I had a dim memory of news reports about white residents in Forsyth attacking participants in a peaceful march for racial equality – not during the tumultuous Civil Rights era but in the 1980s. I watched video clips from an early episode of “The Oprah Show” – a telecast from 1987 when talkshow star Oprah Winfrey went to Forsyth to try to make sense of what was happening there. Some locals in the audience were unrepentant. Footage shows that crowds on the street and a man, to Oprah’s face, were not shy about using racial slurs on national television.

I learned about the 1912 violence in Forsyth after a genealogist who worked with Reuters sent me a note pointing out that my ancestor Abijah Julian appeared in Blood at the Root, a 2016 book that chronicled the bloodshed there. I already knew Abijah had enslaved people and adhered to the “Lost Cause” – the view that the South’s role in the Civil War was just and honorable.

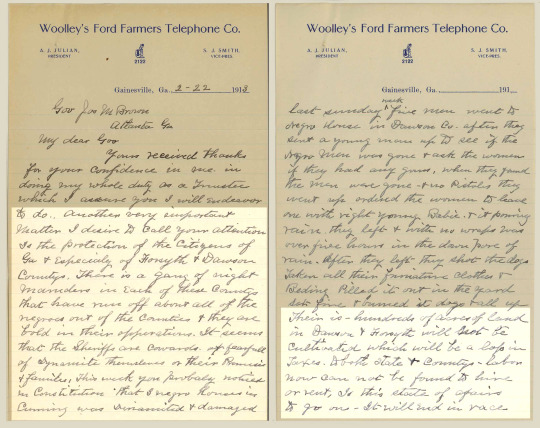

About four months after the terror in Forsyth began, Abijah wrote a letter to the governor of Georgia in February 1913. He was asking for help to quell the chaos unleashed by “night marauders” who had “run off about all of the negroes.” Here’s part of his letter: A letter Abijah Julian wrote to the governor of Georgia.

(Courtesy: Kenan Research Center at the Atlanta History Center.)

During that week alone, Julian wrote, “3 negro houses” in Cumming had been damaged by dynamite. The letter did not suggest any anguish for the Black people who’d been terrorized. What concerned Abijah Julian was his fields and who would farm them.

The Julian land stretched hundreds of acres across Forsyth and neighboring Dawson counties. Abijah told the governor that large swathes of land “will not be cultivated” because “labor now can not be found to hire...”

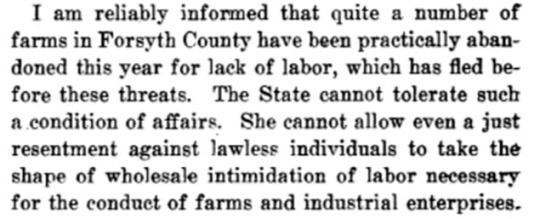

Gov. Joseph Mackey Brown referred to the situation Julian highlighted later in 1913, in a written message to members of the state senate:

After all, the governor continued, “there is no reason why farms should lose their productive power and why the white women of this State should be driven to the cook stoves and wash pots simply because certain people blindly strike down all of one class in retaliation for the nefarious deeds of individuals in that class.”

What happened in Forsyth was not unique. White people across the South had been pushing back against political and economic progress made by Black Americans after the end of slavery and would continue doing so.

In 1906, a white mob stormed downtown Atlanta, killing dozens of Black people and attacking Black businesses and homes. In 1921, a white mob destroyed a Black community in Tulsa, Oklahoma and, according to a government commission report, left nearly “10,000 innocent black citizens” homeless. The death toll was in the hundreds.

Once you begin to look, such violence stretches on and on, decade after decade.

Still hopeful that I might be able to somehow identify and locate living descendants of the people my family enslaved, I flew to Georgia last November.

‘Dick a Man, Lott a Woman’

While I was in Atlanta, I asked my mom and sister if they had time to talk about what I’d found. We sat one evening at the dining room table in my mother’s house, the same table on which we had once shared Thanksgiving dinners with Grandma Horseyfeather.

I had prepared two thick packets of documents that outlined our family tree, each with underlying records, to walk through the lineages of our slave-holding ancestors in three Georgia counties, including Forsyth.

I explained that my search began with a memory of walking with my mother’s father across some land our people used to own in Forsyth; and my grandfather casually remarking of the old well: “The slaves built that.”

“It added up from this one, just sort of little vague memory that I had of Brice gesturing at a well.”

The first question came from my sister, who is married to a Black man. Her voice was stretched thin with emotion. She asked: “Is there any possibility of doing the same for the people that our family enslaved?”

I’d found a man in Grandma Horseyfeather’s lineage who was a slaveholder and likely worked as an overseer in Jefferson County, Georgia. But neither I nor the genealogists we consulted could identify descendants of those he’d enslaved.

“So I’ve – I’ve tried,” I explained. “The issue is that the best details that we have are in Forsyth County, but in Forsyth County they forcibly expelled all of the Black people.”

There were, however, names of enslaved people who were bequeathed in the 1858 will of George Julian, Abijah’s father. At least two seemed to fit with a lineage I could trace.

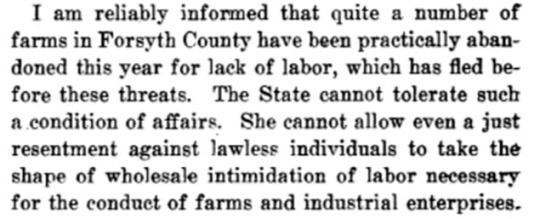

Listed in the will as “Dick a man” and “Lott a woman,” they looked like a possible match for a couple living three households from Abijah Julian’s uncle in the 1870 census. Their names were listed as Richard Julian and Charlotte Julian. Was Dick short for Richard? And was Lott short for Charlotte?

I noticed that Richard Julian had an “M” in the column for Color. The M stood for Mulatto, someone of mixed race. Charlotte was 32 years old in 1870, an exact match for a 22-year-old enslaved woman listed on the 1860 slave schedule as belonging to George Julian’s widow. Richard was listed as 30 in 1870, which did not line up as neatly with an 18-year-old enslaved man next to Abijah Julian in the 1860 slave schedule.

A comparison of the 1870 census and the 1880 census reinforces that Reuters journalist Tom Lasseter is following the same family from one decade to the next. (Source: Ancestry.com)

Still, based on the mention of the names Dick and Lott in George Julian’s will, I followed the Black family’s lineage from one census to the next.

In 1880, Richard was listed as Dick. Lott was there, too, as Charlotte. And their ages were close to what they should have been – about 10 years older than in 1870. The children listed in each census gave me confidence I was following the same family. In 1870, four children were listed. There were three girls and a boy. In 1880, the oldest child was no longer there; she would have been 19 or 20 and may have married. But the boy and the two other girls were there, names and ages matching. The Julians had added four children to the family since the previous census, too, the eldest 8.

My sister’s first question after I traced our family tree that night lingered: “Is there any possibility of doing the same for the people that our family enslaved?”

One of the children in the 1880 census would provide the path.

The Shacks

The day I arrived in Atlanta, November 1, I chatted with my mom about Forsyth and our family’s history there. She’d mentioned something that took me aback.

“When we were talking about the farm, you said there was a slave shack, a slave shed?” I asked her the next day. “What was that?

It turns out my mother had visited the Julian farm when she was a kid. Someone had pointed her to a pair of shacks on the farm and explained that they were where the families of the enslaved used to live.

“It was a structure – by the time we came along it was still on the property but it was, like, a wooden structure that was falling apart.” Her voice became low for a moment. “And that’s what we were told that it was. And I think – I don’t know.” She paused. “I know my grandmother talked about teaching people how to read, or people in her family having taught some of the slaves how to read.”

My mom, a slight woman with a calm voice who works as a nurse with organ transplant patients, was uncertain about the details. “I’m not sure what the – it was just information that she was sharing, maybe to make it feel better that they had slaves. I don’t know.”

I went to dinner with my mom at a Thai restaurant the following evening. I’d been in Forsyth that morning, looking at some documents about the Julian family. She asked me if I learned anything new. I told her about two murders in the family – a pair of sisters slain by the husband of one – that had been covered in the newspapers in the 1880s.

That’s not what she was asking about. My mom looked up from her tofu dish and said, “I am uncomfortable with how little attention was paid to what that was.”

Under her breath, she continued: “The shed.” She meant the slave sheds on the Julian farm.

She said nothing for a few moments. And then she explained, “I was 11.” It was her way of saying she was young at the time. What could she have known about such things? It was the same age as my eldest son.

Why was I putting this at her feet? I thought.

What did she have to do with a white man, dead now for a century, who got rich and enslaved Black people? Where was that money? Not in her pocket. She was working late shifts and driving a beat up Toyota with a side mirror attached to the car by duct tape.

But the feeling of indignation was mine. My mother, a child of the 1960s who took us to downtown Atlanta for parades on Martin Luther King Jr Day, wasn’t being defensive. She was trying to work through what it all meant.

An Unexpected Meeting

Just before Thanksgiving last year, I reached out to a young research assistant at the Atlanta History Center. I’d heard she was tracing descendants of people who fled Forsyth.

Over the phone, I told Sophia Dodd that I was looking for people with the last name Julian. She said she had someone in mind. But first, Dodd would need to check with the person; we arranged to meet in Atlanta later in the month. There was a possibility the person would join us, she said, “but I also know they’re in the midst of traveling so that’s a little up in the air right now.”

I met Dodd at her office a few days before Thanksgiving, ready to ask her questions about Forsyth County.

And then another woman walked into the Atlanta History Center: Elon Osby. She wore a cranberry-colored top and glasses with red cat-eye frames. The 72-year-old Black woman with gray hair shook my hand and said, yes, she would gladly take me up on a cup of coffee.

I hadn’t expected her. I’d not even known her name – Dodd had protected her privacy while Osby decided whether to meet me. But there Osby was, looking at me expectantly. The three of us headed to Dodd’s office.

Without my census forms in hand, I felt exposed. Those family history packets – the ones I shared with my mother and sister – were a way to guide the conversation. And this conversation was with a stranger whose history with my family may have involved slavery. I told Osby that I regretted not having materials to give her.

Osby looked me over. She got to the point. “Is it that you feel that your ancestors were slaveowners of mine?” she asked.

Because I hadn’t done a family tree for her, I explained, I couldn’t be certain. During months of examining the lineages of American politicians, we had held to a firm standard: a slave-owning ancestor needed to be a direct, lineal ancestor – a grandfather or grandmother preceded by a long series of greats, as in great-great-great-grandfather.

As I built my own family lineage, I knew that the Julians were slaveholders. But when I worked with the genealogists on our team to trace the enslaved people named in George Julian’s will, they urged caution. What wasn’t entirely clear: Exactly who had enslaved Richard and Charlotte? Was it George, or was it George’s brother, Bailey?

I offered Osby the abridged version. If she were a direct descendant of Richard and Charlotte Julian, “they were enslaved either by my direct ancestor, George H. Julian” – Abijah’s father – “or his brother.”

As I finished my sentence, I realized the distinction may have been important to the journalist in me. But in this context, it was meaningless. What mattered wasn’t in question: Someone in my family had enslaved hers.

Osby turned to Dodd, the young white woman who’d been helping her research her family.

“First of all, let me ask this.” Osby said. “Do any of these names that he mentioned ring a bell with what you’ve done?”

Dodd answered quickly. “Yes, so I think that it’s definitely very possible that Charlotte and Richard were enslaved by George,” she said.

I asked Dodd if she had an account with Ancestry.com and whether she could print some documents. Together, we navigated to the 1858 will for George H. Julian and the 1870 census forms that showed Richard and Charlotte Julian.

Osby had explained that her grandmother’s name was Ida Julian. And Ida Julian’s parents were Richard and Charlotte Julian of Forsyth County.

Ida. Daughter of Richard and Charlotte. I would see it later. Not in the 1870 census, because Ida hadn’t yet been born. But there she was, listed in the 1880 census. Ida Julian, age 6. Ida Julian, listed in the 1880 census as a young child. (Source: Ancestry.com)

I later found a marriage certificate showing that Ida Julian married a man named WM Bagley in 1889. She was young, perhaps 15. By 1910, the census showed them living in Forsyth County, the parents of three girls and a boy.

The youngest of their children, not yet a year old, was a girl recorded as Willie M. She would go by Willie Mae Bagley, get married, and become Willie Mae Butts – the mother of Elon Butts Osby. The former Ida Julian, now Ida Bagley, in the 1910 census. Her daughter, listed as Willie M., would become Elon Osby’s mother. (Source: Ancestry.com)

After we had worked through the small pile of papers that Dodd had printed, I asked Osby what it meant to see some of those documents.

“It makes people real now. It just makes all of this more real. And it has started a journey for me,” she said, adding that there’s “no telling where it’s going to go.”

I asked her what her family said about Forsyth County when they discussed it with her as a girl. “They didn’t. They didn’t talk about it,” she said.

It wasn’t until around 1980, when Osby was about 30 years old, that she heard her mother tell a reporter the story of her ancestors fleeing the county by wagon because white people were attacking Black families.

“There wasn’t any conversation about it,” Osby said. “But she did talk about her grandfather had this long hair, straight hair, and they would comb it.” That was Richard Julian, Osby’s great-grandfather, the man listed as a “Mulatto” on the 1870 census.

She paused and stared at my face for a moment.

‘I Don’t Think You Can Get Justice’

When Elon Osby’s grandmother, Ida Bagley, and her family fled Forsyth, they left behind at least 60 acres of land, she said.

They made their way to Atlanta after 1912, the year of the carnage. There, in 1929, her grandfather, William Bagley, bought six lots of land in a settlement of formerly enslaved people known as Macedonia Park, according to the local historical society.

It was located in Buckhead, long among the most expensive neighborhoods in Atlanta. The Black residents of Macedonia Park worked as maids and chauffeurs for white families in the area, as golf caddies and gardeners.

Osby’s grandfather made money as a cobbler and local merchant. Her parents opened a store and a rib shack. Her father was also a butler for a wealthy white family, her mother a cook. The area became known as Bagley Park, and her grandfather, according to a historical marker now at the site, was considered the settlement’s unofficial mayor. William Bagley, Elon Osby’s grandfather, was known as the mayor of Bagley Park, a Black enclave in Atlanta that was later razed by the county.

(Courtesy: Elon Osby)

In the late 1930s and early 1940s, nearby white residents – members of a women’s social group – petitioned the county to condemn and raze Bagley Park, ostensibly for sanitary reasons. It had no running water or sewer system. The county, which had not provided those services, agreed, forcing the families to leave. They were compensated for the land, but it’s not clear how much, and in the process they lost real estate in what is a particularly affluent quarter of the city.

Osby’s family had again been pushed off its land. The settlement was demolished and replaced by a park, later named for a local little league umpire. Last November, the city of Atlanta restored the area’s name: Bagley Park.

In thinking about Osby’s family and my family, I found it was impossible not to compare them – and the role slavery played in our respective paths. In 1860, Osby’s ancestors were enslaved and working the fields of Forsyth County. In 1860, my ancestor Adaline Julian, widow of George and mother of Abijah, reported a combined estate value of $19,020. She was among the wealthiest 10% percent of all American households on the census that year. And that wealth didn’t include her son’s holdings. Then just a teenager, Abijah had a personal estate of $4,828, according to census records. That amount lay largely in the value of the enslaved people bequeathed to him by his father.

In 1870, Osby’s ancestor, Richard Julian – free for only about five years – was listed on the census as a farmhand, with no real estate or personal estate to report.

In 1870, Abijah Julian – despite having “lost” those he had enslaved – still had a combined estate of $4,655. That put him in the top 15% of all households in America, census records show.

Osby said her parents used the money they got from the government after being forced out of Bagley Park to buy land in a different part of Atlanta. They continued to work hard. Her father was hired as an electrician by Lockheed, and her mother ran a daycare business.

Osby spent a career working in administration. She said she started as secretary for the manager of the city’s main Tiffany & Co location in 1969, then worked in various city government offices, and now for the Atlanta Housing Authority.

After she’d finished telling me about her family and herself, I asked Osby whether she would mind me recording some video with my cell phone. I asked once again about her family’s reluctance to discuss Forsyth. She repeated that Black parents had long kept such things quiet. I noticed she added the words “rape” and “lynchings.”

But, she said, she has seen considerable progress during her life. Osby, whose family was forced out of Forsyth in 1912, was the keynote speaker in 2021 at a dedication event in downtown Cumming, where a plaque memorializing the bloodshed in Forsyth had been installed. And Osby, whose family was forced with others to leave their neighborhood in Fulton County, is now a member of the Fulton County Reparations Task Force. The group advises the county board and has sponsored research on what happened at Bagley Park, including a report documenting what Osby already knew: that “property owners in Bagley Park were forced to liquidate their real estate, a vital link in the chain of generating generational wealth.”

“There was a time when I didn’t feel that restitution or reparations was necessary” for the land taken from Black families after 1912 in Forsyth, and then what followed in Bagley Park, Osby said.

“I just want somebody to acknowledge it and say, you know, we’re sorry. But I have come to realize, or come to feel, that we do need to receive something in the form of restitution. I think that the main thing is, if you touch people in their purses they’ll think before they let something like that happen again. I think it’s mainly about [how] we can never let this happen.”

As for her enslaved ancestors, Osby had a different outlook on reparations. “I don’t want to think of slaves as property. And if I have to give you a value for a slave person so that you can, you know, give me reparations for that – then that’s making them property. That’s reinforcing that idea that they were a piece of property for somebody to own.”

I asked her what it meant to know that history – to know more about what happened during slavery in such personal terms. To know that my own ancestors enslaved people. Osby puckered her bottom lip, paused for a moment and sighed.

She pointed her left index finger at me and said it was a question for me to answer. How did I feel, she asked, when I found out my ancestors enslaved people?

‘What Does It Mean to Know This?’

I told her the story of the old well and my grandfather. I told her about the reporting project, about finding out that my family enslaved people not only in Forsyth, but at least two other counties as well.

Finally, I stopped talking. In my mind, I had run through the right things to say. In a blur, I wondered: Should I apologize to Osby, to her family on behalf of mine?

Instead, I decided to talk about what made me most comfortable: the journalism itself. “A lot of it has been just establishing, sort of, the facts – figuring out, this is who they were, this is what happened,” I said. “I guess sitting here right now I don’t have an answer for – I don’t have an answer for my question” on the value of discovering more about slavery.

She leaned back and laughed.

At some point, I lowered the camera from chin height to the table. My hands were trembling. I was based in Iraq for three years. I sat with militants in Afghanistan. I know what mortar and machine gun fire sound like, at very close range. But at this little table, before this woman, I felt nervous.

I kept talking. I talked about how we – meaning white people – choose to know but not know. I told her about my mom remembering the decrepit former slave sheds on the Julian farm.

Osby no longer was smiling.

She began to talk about something that circled back to her comments about her great-grandfather’s straight hair, her curiosity about possible Cherokee Indian heritage. And, also, to rape.

“Black people, we’ve always known either through the movies or if you’ve learned it, you know, from your family, about the interracial relationships that happened on these plantations or whatever,” she said. “My grandmother – very, very fair skinned. I have one picture of her where she, you know, looks like she’s white. And so, you know that somebody else was there. You know?”

Somebody else was there. It was a phrase with a passive structure common to the South, a way of not assigning blame to the person sitting across the small table from you in the corner of an office. The meaning nonetheless seemed clear to me: Did my ancestor rape her ancestor?

“I’m curious, and that’s one reason why I was excited about coming to speak with you because I want to find out about the Cherokee part,” she said. “And also, if there was a white person, you know, that was, her – whatever,” she said, cutting the sentence short and fluttering her hands in the air.

I told her that I’d done a DNA test online. She said she was considering taking one as well.

After we spoke, Osby asked me to go with her to the graveyard at Bagley Park. I followed her Mazda. Its license plate read MS ELON. Her grandparents were buried there, she said, but she couldn’t say where. The gravestones had been vandalized over the years, Osby explained, looking at the broken markers.

Panic and Questions

After we parted, I drove to Forsyth County and the Julian farm. I could see across the road to the spot where my mother described the slave shacks having once stood.

The door was locked, the farmhouse empty. I stood outside the white clapboard home and stared. The leaves crunched underfoot, down at the end of Julian Farm Road. I rested my forearms on a dark slat fence and scanned the property, a utility shed to the right and a patio to the left.

I did not see the well.

I walked to the front of the house and looked for it. The well wasn’t there. I went to the back edge of the land, which now sits on the shore of a man-made lake that flooded part of what was once Abijah Julian’s farm. Nothing. The waters of Lake Sidney Lanier near what was once a farm owned by Abijah Julian. The lake, created in the 1950s, flooded parts of that farm. REUTERS/Tom Lasseter

I felt panicky. The well, the totem of my memory and the genesis of this project – “The slaves built that” – was nowhere. Was it possible I had mixed up some other memory, that it was never at the Julian farm?

I walked over to a step behind the house and sat down. My thoughts about the well gave way to replaying parts of my meeting with Elon.

Should I have apologized to her? “I am sorry,” I could’ve said. “I am sorry that my ancestors brutalized your ancestors.” What had stopped me?

The next day, I sent a text message to the man who now owns the Julian property. Did he know anything about an old well? “Yeah, there was a well next to the house that was dried up. We covered it,” he replied. He sent me a photograph of the front of the house from a 2019 real estate listing. And there it was – the well I remembered, at the far right of the picture.

I peered at the photo. I read the listing. The lake that flooded part of the farmland had created 209 feet of waterfront that now featured four boat slips, according to the advertisement for the property. It noted the farmhouse was “originally built in the late 1800’s by the family of State Senator Abijah John Julian” and added another dash of history: the Julian family was “of the Webster line circa 1590 England.” There wasn’t a word about the other side of the Julian family history: slavery.

Instead, under the section for what the seller loved about the home, was this line: “Your own private plantation.”

What Should Be Handed Down?

In the months after my visit to Forsyth, I’ve looked at a video of the church service that I attended last summer on Juneteenth, the national holiday marking the end of slavery. At the time, I had bristled at the pastor’s remarks, which centered on the need for white people to face our history, to atone.

Toward the beginning of the service, the children had been sent to Sunday school. So my sons weren’t sitting next to me when the pastor said, “We’re asked to stay home and to reflect with those who we know and whom we love – we’re asked to … have the difficult conversations about race and status and prestige and wealth.”

There was another detail that I hadn’t associated with that day’s sermon. It wasn’t only Juneteenth; it also was Father’s Day. From a 2019 real estate listing. The well is seen at the far right in this photo of the front of Abijah Julian’s house.

I’ve thought more than once about all that I had missed. About what to tell my children about everything I’ve learned in the past year. About our family’s part in slavery and the descendants of those we enslaved. About my conversation with Elon Osby.

What should be handed down, and what should not?

Getting ready for a reporting trip last year, I was sifting through online documents from an archive in south Georgia.

I came across a photograph from 1930 of white men sitting in front of an American Legion post. They each wore a medal on the left lapels of their suit jackets. I zoomed in and saw what had caught my eye. It was the cross of military service, handed out by the United Daughters of the Confederacy to World War I veterans who were direct descendants of Confederate soldiers.

In a little white box on a shelf in my home office, I have that same cross. It had been given to my great-grandfather, from Brooks County. After my great-grandmother Horseyfeather died, my family gave it to me, the ever-faithful son.

I fished the cross from its box and turned the thing around in my fingers. The cross was decorated with an X formed by two stripes of stars immediately recognizable from the Confederate battle flag. Around the edge, in the background, are a Latin phrase and two dates: Fortes Creantur Fortibus 1861-1865. The years are those of the Civil War. I Googled the phrase. It means the strong are born from the strong.

I’d had that cross for about 25 years and always associated it with my great-grandfather’s service in World War I, its dates marked in the foreground. I had never stopped to look more closely.

Peering down at it now, I realize it also meant something more: a loyalty to the South when it was a land of slavery and secession.

I was holding on to a relic of the Lost Cause, a history of savagery cloaked in nostalgia. I was holding on to something that I needed to explain to my sons, and then to let go. As I type these words, I have yet to have that conversation. The medal remains on my shelf.

Apology and Absolution

I met with Elon Osby once more earlier this month. We walked again through the cemetery at Bagley Park, where somewhere her ancestors are buried, their gravestones long gone. We stopped at a picnic table. I asked her about the last time we met, reading some of our quotes out loud and talking through what each of us had meant.

There was rain coming, with dark clouds, then lightning. I told her that I’d been nervous during our initial conversation. She asked whether I thought the guilt had been passed down: “Most white people do not have ancestors that owned slaves,” she said. I pointed out that I have at least five.

I said that I’d wondered if I should have apologized. “No,” she said, “I don’t transfer the guilt. Or not the guilt, but the responsibility of it. I don’t do that.” I said with a nervous laugh that I wasn’t asking her to absolve me.

The lightning drew closer. It was time to leave. “We’ve probably covered everything,” Osby said, gesturing to get up.

But I wanted to say more. Ignoring the rain, I reached for the words I hadn’t found during our first meeting: “I’m very sorry that it happened. You know, that all of that happened. And I feel that every time I look through those wills and the language that they used. And that 1858 will – listing furniture and livestock and then human beings. You know, I can’t help but be sorry.”

Osby stopped and looked at me. Listening to the recording later, I could hear the wind and the rain in the background. And then her voice. “It doesn’t feel good at all when you see the horses and cows and slaves. You know, it doesn’t feel good at all,” she said. “But at the same time, it happened. It happened to my people. I don’t want to forget about it.”

She pointed at the packet of genealogical material I’d brought along, mapping our families and that terrible history long ago in Georgia. “This is good enough. What you’re doing for me and my family, bringing this information to me.”

She let a moment pass, and then said: “You’re absolved.” She threw her head back and let the laughter roll like thunder. As the rain fell, we walked to the parking lot together. We paused, then hugged before parting.

“The Slaves Built That”’

By Tom Lasseter

#georgia#slavery#slave records#reuters reporter explores his slave owning roots#“The Slaves Built That”#white supremacy#Blacks Enslaved in America#forsyth county#lynching#stolen land#stolen heritage#ancestral dna

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

OBIT: Allan Whiteside

Allan “Al” Whiteside, 75, of Charles City, passed away Sunday, April 7, 2024 at the Floyd County Medical Center in Charles City.

A funeral service for Al Whiteside will be held at 10:30 a.m. on Friday, April 12, 2024 at Trinity United Methodist Church in Charles City. Burial will be at 2:00 p.m. at Lynwood Cemetery in Clarksville, Iowa.

Visitation will be from 4:00 to 7:00 p.m. at the church on…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Entertainment calendar: March 8–14 | Entertainment

A LITTLE NOON MUSIC, 12:15 p.m. Wednesday, March 8, First United Methodist Church, 522 White Ave., violinist Alisha Bean, donations accepted, fumcgj.org, 970-242-4850.

“FLOYD COLLINS,” 7:30 pm. Wednesday, March 8, Mesa Experimental Theatre, Moss Performing Arts Center, Colorado Mesa University, 1221 N. 12th St., haunting musical based on the true story of a 1920s Kentucky caver, $24 adults, $20…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

Kathleen “Kitty” Short Kandalaft, daughter of the late Kenneth Short and Martha Lester Short, was born on August 17, 1930, in Indian Creek, West Virginia, and departed this life on April 7, 2022, at Saint Francis Medical Center in Cape Girardeau, Missouri, at the age of 91 years.

Mrs. Kandalaft was a former educator with the Sikeston Public School System in Sikeston, Missouri, where she taught third grade for 20 years. She was a member of the First United Methodist Church in Dexter, Missouri, and a resident of Dexter. She was a former member of the Dexter School Board and Missouri State School Board.

A lifelong learner, Kitty loved literacy, music, nature, and poetry. She began her college career at Concord College in Princeton, West Virginia before transferring to Bob Jones University in Greenville, South Carolina, where she learned to play the harp, and obtained her music degree. In 1957, she earned her master’s degree in education from Northeast Missouri State Teachers College. Aside from motherhood, one of the highlights of her life was obtaining her private airplane pilot’s license in 1971.

During her lifetime Kitty traveled extensively. She toured England, Rome, Venice, Paris, Spain, Portugal, Katmandu, Lebanon, Jordan, Amsterdam, Israel, Switzerland, and Germany. She visited Belgium via the Channel from England. Her favorite spot was Vienna, Austria, because of the musical influences, and because it was so clean.

While attending Bob Jones University, she met her first husband, Dr. Fuad Kandalaft and to this union four daughters were born, Victoria, Catherine, Patricia, and Leila. On April 14, 2007, she was then united in marriage to Dr. Floyd C. Northington. Dr. Northington preceded her in death on March 9, 2016.

She is survived by her daughters, Victoria Kandalaft of Germantown, Tennessee, Catherine Kandalaft Clippard of Ozark, Missouri, Patricia Kandalaft of Seattle, Washington, and Leila Kandalaft of Ludwigsburg, Germany; by her brother, Michael Short of Kentucky; by her sister, Patsy Harrington of Fayette, Missouri; and by seven grandchildren Arabella McGowan, Ayman McGowan, MarthaGrace Clippard, Luke Clippard, Leila Serene Heidsieck, Helena Stroetmann, and Alexander Stroetmann.

Other than by her husband and parents, she was preceded in death by her brother, Douglas Short and by her sister, Dorothy Short.

Visitation will be held at Mathis Funeral Home in Dexter on Sunday, April 10, 2022, from 5:00 p.m. until 7:00 p.m. Funeral services will then be conducted at the First United Methodist Church in Dexter on Monday, April 11, 2022, at 11:00 a.m. with Rev. Larry Lawman officiating. Interment will follow in the New Bethel Ezell Cemetery.

Memorials may be made to the Bethlehem Bible College, 614C South Business IH-35, New Braunfels, Texas 78130.

#Bob Jones University#Archive#Obituary#BJU Hall of Fame#BJU Alumni Association#2022#Class of 1950#Kathleen Short Kandalaft

0 notes

Text

Dear Gus & Magnus,

This morning I drove to Floyd for Mary Dean's funeral service -- here's a thing I wrote about what she means to me. I enjoyed being back in the church where I spent the first eight years of my life, where so many of the same people still sit in the pews, even after 35 years. It's fitting that I posted the photo of Kaia the other day because the guy standing behind Ronnie Dean is Paul Jenkins, the veterinarian who did his best to remove the tumor from that dog I loved so much.

After the funeral, I followed Monkel to his new abode in the woods and he gave me a tour. And then I stopped by Nancy's at her request. I enjoyed talking with each of them. Ever since Mum died, my number of interactions with them have dwindled. I don't think I realized that I've missed them.

Dad.

Floyd, Arkansas. 10.16.2021 - 10.53am.

#mike choate#ronnie dean#paul jenkins#bart jenkins#floyd united methodist church#funeral#mary dean#floyd arkansas

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Suffering from a blast of police pepper spray, the Rev. Laura Young, an ordained United Methodist elder, received care from bystanders during an anti-racism demonstration in Columbus, Ohio, on Saturday (May 30). “I was pepper sprayed in the face, intentionally, with no warning, by police,” said Young. “We as clergy need to be standing with the marginalized … If we’re going to put our faith into action, which is a phrase a lot of Methodists like to use, what better way to do it than when it’s really needed?” Young is known for her LGBTQ advocacy within the United Methodist Church. Photo by Monica Lewis.

#religion#christianity#protestantism#methodist#united methodist church#protest#george floyd#divinum-pacis

45 notes

·

View notes

Link

The Socialist Unity Party/Partido por el Socialismo Unido and Struggle-La Lucha newspaper condemn in the strongest possible terms the racist, sexist, fascist shootings in the Atlanta area that targeted mainly Asian women, but also Asian and Latinx men.

We express warm solidarity and class love to the families, friends and communities of the victims of this despicable attack: Delaina Ashley Yuan, Xiajie Yan, Daoyou Feng, Paul Andre Michels, and four others whose names have not been released at the time of writing. It is known that six of the eight people killed were women of Asian descent. A ninth victim, Elcias Hernandez-Ortiz, is in the hospital fighting for his life.

The killer, a 21-year-old white man named Robert Long, claims that his rampage was rooted in a “sex addiction,” and that he attacked three spas in order to “eliminate a temptation.” Georgia police officials are backing this as an excuse for mass murder. But to many, it’s clear that this violence is rooted in both patriarchal subjugation of women and, in particular, the racist fetishization of immigrant women.

It is crucial to understand the role of the state not just in these particular killings, but also the monstrous string of racist, fascist killings leading up to this. These include the murder perpetrated by, to name only a few: Dylann Roof, who murdered nine Black attendees at the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, S.C.; Robert Bowers, who murdered eleven Jewish attendees of the Tree of Live synagogue in Pittsburgh; Derek Chauvin, who murdered George Floyd in Minneapolis; Darren Wilson, who murdered Michael Brown Jr. in Ferguson, Mo., and; Jonathan Mattingly, Brett Hankison and Myles Cosgrove, who murdered Breonna Taylor in Louisville, Ky.

Like many of these racist murderers, Robert Long was apprehended and detained by police without incident. Police took Dylann Roof for a cheeseburger after he murdered nine innocent Black people. In contrast, the Black victims of police violence George Floyd, Michael Brown and Breonna Taylor were unarmed and not charged with anything.

The murders in Atlanta must be seen in the context of former President Donald Trump’s viciously racist anti-immigrant bile, in both words and policy, as well as his constant attempts to blame the COVID-19 pandemic on the Chinese government. President Joe Biden has continued this anti-China sentiment by escalating the Cold War-style provocations against China, which has also contributed to a rise in attacks on Asian Americans and Asian immigrants. According to a report by Stop AAPI Hate, nearly 3,800 racist incidents against Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders have been documented since last March.

The shootings must also be seen as a continuation of centuries of U.S. imperialist aggression in Asian countries. In the pursuit of profit, Washington perpetrated some of the most gruesome acts of inhumanity in history — bombing northern Korea flat, dropping two atom bombs on Japan, pillaging Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia, and committing genocide in the Philippines, only to name a few. Similar to its operations in Latin America, U.S. involvement creates refugees and forced migration. Often, migrants and refugees seek a better life in the United States only to be met with racist violence and exploitation.

In this context, it is impossible to deny the complicity of the capitalist state in racist vigilante killings. As we saw in Trump’s attempted coup on Jan. 6 in Washington, D.C., cops and fascists go hand in hand. Capt. Jay Baker, the Cherokee County sheriff’s spokesman, made this abundantly clear when he claimed killer Long was just having “a really bad day.” Baker had previously made social media posts blaming “CHY-NA” for the coronavirus pandemic.

The only answer to this is working class unity, proletarian internationalism, and the struggle for socialism.

#Atlanta shooting#Asian Americans#women#immigrants#racism#imperialism#massacre#COVID19#China bashing#Donald Trump#Joe Biden#capitalism#capitalist state#police#Struggle La Lucha

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sunday go to meeting: St. Andrew’s Anglican Church. This building was formerly home to St. Luke’s United Methodist Church and served the workers and families of the Chatillion/Tubize/Celanese textile mill in Floyd County. The current congregation is doing a great job of tastefully maintaining the building and grounds.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

subfluence merged in an ornamental lake

but these very subfluences 1

subfluence over boundaries or lands 2

subfluence which natural causes have on the limity of the reflection 3

subfluence, recording occurrences 4

subfluence over ennui. I had not the 5

subfluence. What do we do? What does the 6

subfluence, discoverable or unexplained 7

subfluence, at nights 8

subfluence in production or waste, used freely 9

subfluence literally incalculable, the principle on which 10

the heart-beat is subfluence. 11

subfluence diffused 12

subfluence full of romance 13

lies, and other caustic or irritant subfluence 14

subfluence, the signaling, the adjustment of huge mechanisms 15

subfluence merged in an ornamental lake 16

subfluences subdued 17

his special subfluence,

for he was an omnivorous reader, and had a picturesque and even romantic outlook on 18

subfluence, with the colors still 19

subfluence the entire cotton trade 20

subfluence spread far and wide. 21

subfluence, the possibility of human flight 22

subfluence for lack of language : error 23

Subfluenz-Prozesse 24

Subfluenz, einer varistischen 25

sources (most, and mostly OCR misreads)

1

OCR misread for “substances,”

at “Of points wherein we and Papists differ, viz., Transubstantiation, &c.,” in John Rawlet (1642-86 *), A dialogue betwixt two Protestants, in answer to a Popish Catechism (Third edition, corrected; London, 1686) : 82

2

ex “A sketch of the life and public services of Gen. William Henry Harrison.” in (Isaac Rand Jackson?), General William Henry Harrison, Candidate of the People for President of the United States (Baltimore, 1840) : 6

Harrison (1773-1841) would have a short (31-day) tenure as president, but had done enough damage in previous roles, particularly with regard to indigenous people.

see wikipedia

3

ex “Scripture and Geology” (by N), in The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction (Saturday, August 14, 1841) : 99-103 (100)

see wikipedia for its publisher John Limbird (1796?-1883)

4

ex “Druids and Bards,” being an extensive notice/review of three books — J. B. Pratt The Druids Illustrated (1861), John Williams, ed., Brut y Tywysogion (1860), and Godfrey Higgins, The Celtic Druids (1829), in The Edinburgh Review, 118 (American Edition; July 1863) : 20-36 (35)

5

ex “A Rolling Stone.” By George Sand, translated from the French by Carroll Owen, in Library of Famous Fiction 2 (1879) : 1-113 (109)

6

OCR cross-colum misread, involving M. H. Cobb, “Common Sense Applied to Living” (pp 5-7) and “A Parlor Drama, in Two Acts” by Augusta De Bubna (pp 7-13), in The Brooklyn New Monthly Magazine, Henry Morford (1823-81), editor and manager; 1:1 (January 1880) : 7

7

ex A. Ernest Sansom, “The Dyspepsia of Infancy,” in The New York Medical Times 19:2 (May 1891) : 33-37 (34)

8

involving obituaries (memorials) for James Holmes and David Wright, in the section “Connexional Biography” in The Primitive Methodist Magazine 73 - London, 1892) : 51

on “Connexionalism” (and its relation to “network”), this, from wikpedia —

“The United Methodist Church defines connection as the principle that ‘all leaders and congregations are connected in a network of loyalties and commitments that support, yet supersede, local concerns.’ Accordingly, the primary decision-making bodies in Methodism are conferences, which serve to gather together representatives of various levels of church hierarchy.”

9

ex “Brief Gleanings : The treatment of Leanness and Obesity” in The Medical Brief (A Monthly Journal of Scientific Medicine; J.J. Lawrence, Proprietor) 20:10 (St. Louis, Mo; October 1892) : 1240

10

ex W. Garden Blaikie, “St. Paul’s Pastoral Counsels to the Corinthians.” in Exegetical and Expository Section, The Homiletic Review 29:5 (May 1895) : 451-453

11

Aloysius O. J. Kelly, “Essential Paroxysmal Tachycardia — Report of Four Cases.” (Read October 14, 1896), in Proceedings of the Philadelphia County Medical Society 17 (Session of 1896) : 166-180 (171)

Kelly (1870-1911) obituary at Boston Medical and Surgical Journal (now NEJM) March 9, 2011) : 360

12

out of chronology (and unlinkable snippet, only), mea culpa, ex The Evangelical Magazine and Missionary Chronicle 21 (1813) : 328

13

snippet only, evidently from Chapter 9 “Signs and Tokens” of Charles Dickens, Bleak House (1852-53), here ex Works Volume 3 (1899) : 374

14

misread involving “Milk a Universal Antidote” and “School-Meals for Underfed Children” in The Dietetic and Hygienic Gazette (A monthly journal of physiological medicine) 16:1 (January 1900) : 20

15

ex Edward Nelson, “Electricity in Service on British Battleships,” in Electricity 29:23 (December 6, 1905) : 311-313

16

preview snippet only, at (Commonwealth of Australia) Parliamentary Debates 57 (1910) : 3207

17

ex index of volume, Proceedings of the American Society for Psychical Research (Section “B” of the American Institute for Scientific Research) vol. 5 (New York, 1911) : 771

18

ex entry (by “C. L. G.”) for Meredith White Townsend (1831-1911), in Dictionary of National Biography, edited by Sidney Lee. Second Supplement vol. 3, Neil – Young (New York, 1912) : 532

19

preview snippet only, ex The American Year Book 5 (1915) : 300

20

§ 816. Corners... in William Herbert Page, The Law of Contracts Second edition; revised, rewritten and enlarged with forms. Volume 2. (Cincinnati, 1920) : 1441

21

ex “Balboa Day, September 17th, 1919 in Honolulu,” in Bulletin of the Pan-Pacific Union (January 1920) : 6

22

misread, involving report on “The Langley Flying Machine” (and some controversy between S. P. Langley and the Wright brothers), and “The Impurity of Pure Substances” (review of A. Smits, Theorie der Allotropie (1921)) in Nature 108 (November 3, 1921) : 298

23

misread, involving Booth et al v. Floyd (No 2358) and Blackstone v. Nelson, Warden (No 2457) in The Southeastern Reporter 108 (August 27 - December 3, 1921) : 114

24

H. J. Behr, “Subfluenz-Prozesse im Grundgebirgs-Stockwerk Mitteleuropas.” Zeitschrift der Deutschen Geologischen Gesellschaft 129 (1978) : 283-318

25

K. Weber, “Das Bewegungsbild im Rhenoherzynikum Abbild einer varistischen Subfluenz.” Zeitschrift der Deutschen Geologischen Gesellschaft 129 (1978) : 249-281

referring to the Variscan Orogeny (wikipedia)

method

1

There is no word “subfluence,” or only barely one.

This started with the self-written biographical note of poet Jack Hirschman, in A Caterpillar Anthology (Clayton Eshleman, ed., 1971) —

“They are lyrical poems, in verse or free-form, as distinguished from the poems in this anthology, which are breath forms reflecting a more total slavery to the conditions of the spirit’s war-torn years. The major influences on my works are influence itself, in as many levels of order, disorder, disaster, paranoia, joy and ecstasy as the deathless magic of being alive permits a vessel now of fire, now of air, to spark, glow, flame and ember according to the law of nature.”

“Influence” — that word — led to thinking about variations, e.g., effluence, outfluence, pre-fluence... “subfluence” —

an underground stream

a less-than fluency (stammering, stuttering)

a brittleness?

Little — or nothing — surfaced in a google books search, save for errors — typically a “sub” at the end of one line, a “fluence” at the start of the next (in a different column). Quite enough for present purposes. And so these subfluence derivations are built around a word that isn’t quite a word. Some license has been taken with the text in this post: dispensing ellipsis or [brackets] where text is erased (or rather, dropped); in some instances, some words that preceded the subfluence, are moved to follow it.

2

And yet, the word does appear, in some (and only a few) geological texts, typically having to do with the geotectonic unterströmungshypothese (undercurrent) concepts — and field work done in the Northern Calcareous Alps — of and by Otto Ampferer (1875-1947). More on Ampferer to come. For now, these references —

Wolf-Christian Dullo and Fritz A. Pfaffle, “The theory of undercurrent from the Austrian alpine geologist Otto Ampferer (1875-1947) : first conceptual ideas on the way to plate tectonics,” Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 56 (2019) : 1095-11

here

Karl Krainer und Christoph Hauser, “Otto Ampferer (1875–1947): Pioneer in Geology, Mountain Climber, Collector and Draftsman,” in: Geo.Alp Sonderband 1 (2007) : 91–100

here (pdf)

wikipedia (in German)

Dr. Otto Ampferer. “Über das Bewegungsbild von Faltengebirgen” (On the movement pattern of folded mountains), in Jahr. Geol. Reichsanstalt (Yearbook of the Austrian Geological Survey), 56:3-4 (1906) : 539-622

“Mit 42 Zinkotypien im Text”

here

3

“Subfluence” also surfaces as a company name, social media handle, &c., &c.

—

all tagged subfluence

5 notes

·

View notes

Link

From Rev. Dr. Susan Henry-Crowe, the General Secretary of the General Board of Church and Society of The United Methodist Church:

The Bible is a sacred text for over a billion Christians around the world. Our churches are sacred sites for worship. The Bible is not a prop on a political stage.

On Monday evening, June 1, President Donald Trump asserted his authority to pervert the use of our sacred scriptures and violated the purposes of holy space. His action was an affront to the Christian community.

The President authorized the use of federal government power to disrupt the pastoral ministries of clergy and laity from St. John’s Episcopal Church using the Church for a photo opportunity.

With the use of the security personnel, senior members of his administration and Cabinet officers, he occupied the property of St. John’s Church. He used the St. John’s Church building and its signage to create the appearance of Christian endorsement of his views, as he raised a Bible as if it were a political decoration rather than as a sacred text to be read and studied prayerfully.

In addition to deploying the Bible as a prop for his calls for “law and order,” he failed to acknowledge the purpose of the protests or mention the name of Mr. George Floyd whose memory was the focus of the protests. Furthermore, the Holy Bible does not legitimize militarized police or calls for law and order.

We are grateful for the faithful witness of our sister, Mariann E. Budde, Episcopal Bishop of the Diocese of Washington who has decried this shameful abuse of a house of worship.

Today we stand in solidarity with all people of faith and our Christian sisters and brothers working to eradicate racism, white supremacy, violence and injustice.

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ramona Lee Robinette Milwood

Ramona Lee Robinette Milwood, 90, of Pacolet, SC died Tuesday, April 6, 2021 at Physical Rehabilitation and Wellness Center of Spartanburg. Born September 20, 1930 in Pacolet Mills, SC, she was the daughter of the late Amos Lloyd and Lucille Hodge Robinette and wife of the late Jack Ray Milwood Sr. A graduate of Pacolet High School, Mrs. Milwood loved her family, Jessie Wicks, dog, Bentley Alexander, longtime friends, and doing for others. She was a member of Pacolet United Methodist Church. Survivors include her son, Jack Ray Milwood Jr. (Linda) of Pacolet, SC; daughter, Dr. René M. Holden of St. Louis, MO; grandchildren, Wendy M. Rollins (Robert) of Campobello, SC, Jack R. Milwood III (Brenda Winchel) of Lorain, OH, Lee T. Holden of Miami, FL, and Nicholas S. Holden of Charleston, SC, and great-grandchildren, Samuel D. Rollins and Sophia Grace Rollins both of Campobello, SC. She was predeceased by son-in-law, Richard C. Holden Sr., and siblings, Carolyn Turner, Mary Jo Dillard, and Robert Robinette. No services are scheduled at this time. In lieu of flowers, memorials may be made to Pacolet United Methodist Church, P O Box 427, Pacolet, SC 29372 -0427. Floyd’s North Church Street Chapel

from The JF Floyd Mortuary

via Spartanburg Funeral

1 note

·

View note

Text

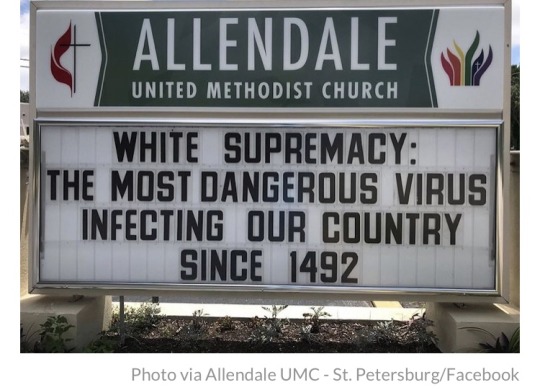

https://m.orlandoweekly.com/Blogs/archives/2020/05/27/george-floyd-was-lynched-today-central-florida-church-calls-out-white-supremacy-with-incredibly-accurate-sign

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Unimportant Ramblings

Alright so, in light of the recent murder IN MY HOME STATE of Minnesota in our largest city Minneapolis during a global pandemic wherein we got caught with our pants down having voted in the “Send in the Clowns” era of world leader, I am forced to consider why exactly it is I’m working for an ungrateful piece of shit inherited wealth drunk in a small town with a 40 minute commute for less money than I would make on unemployment when all I want to do is go and join the protests in the big city.

Like, why am I working for this smug old prick who inherited his earnings? In the public, exposing myself every day I work? For no job title, minimal recognition, just working “swing” or “support” for a business owned by an old homophobe?

I’d been having a pretty rough go of it even before George Floyd was murdered a scant 60 miles from my home town. By the police.

I come home every night either mad or just done with work. And then I go back the next morning and do it all again. For what? For the opportunity cost of not being able to protest? For the chance to get ignored by the owner, and praised by a manager whose so burnt out himself he’s taking more than a week off going into the first time the restaurant could be opened again?

I’m currently helping out in the Market/Deli, and just for context we’ve already lost 4 Market Manager’s in the 2 years the Plaza has been open. We’ve also lost 5-6 head chefs, depending on how you count it, and at least 3 butchers. We’ve had over 100 employees in the 2 years we’ve been open and we’re currently operating on a staff of 12 people.

And the worst part is? I like most of those people. I came back after layoffs for the last manager who walked out.