#Ed Koch

Text

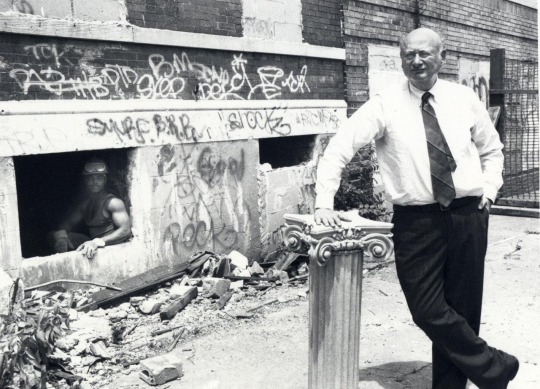

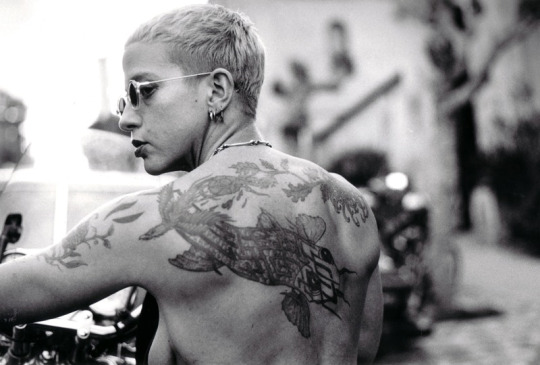

Photo, 1981, by Gary Lee Boas, from his book New York Sex 1979-1985 (Galerie Kamel Mennour, 2003).

#80s#nyc#lgbtq#guys#photos#gary lee boas#1980s#lucy's pork#street#culture#queer#gay#men#boys#queer history#urban#city life#ed koch#👽

248 notes

·

View notes

Text

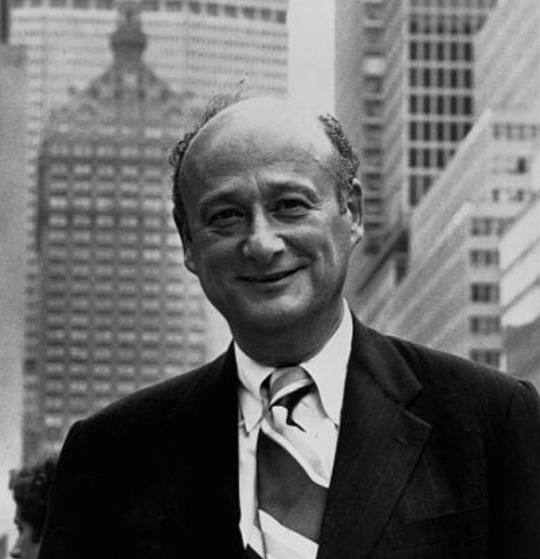

Ed Koch

#suitdaddy#suiteddaddy#suit and tie#suited daddy#men in suits#daddy#silverfox#silver fox#suitfetish#suited grandpa#suitedman#suit daddy#suited men#suited man#buisness suit#suitedmen#americans#democrats#nyc mayor#Ed Koch

26 notes

·

View notes

Photo

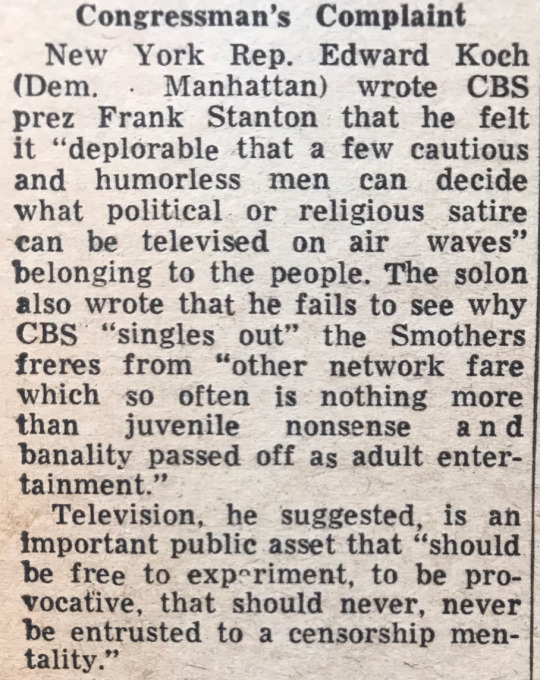

1969.

Before he was the Mayor of New York, Ed Koch came to the defense of the Smothers Brothers.

48 notes

·

View notes

Photo

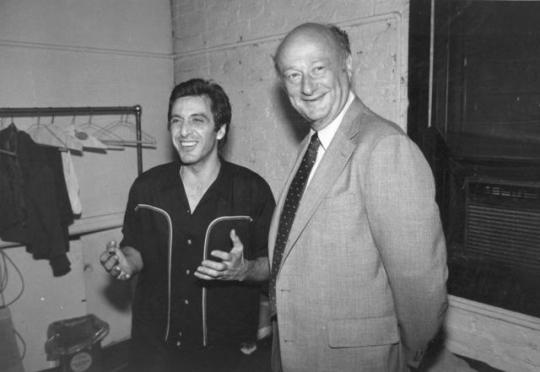

New York City mayor Ed Koch, right, visits backstage with actor Al Pacino at the Circle in the Square Theater in Greenwich Village, New York, on June 13, 1981 following a performance of the play "American Buffalo." (AP Photo)

23 notes

·

View notes

Link

By Stephen Millies

Six days after Israel invaded Lebanon, a million people came to New York City’s Central Park on June 12, 1982. They demanded a nuclear freeze and peace. But none of the speakers mentioned the slaughter in Lebanon.

The rally organizers thought it was more important to get the endorsement of racist New York City Mayor Ed Koch, a big supporter of Israel.

The refusal of the “official” U.S. peace movement’s leadership to denounce Israel’s invasion was repulsive. It broke down the anti-war movement.

The challenge today is NATO’s war against the Donbass republics and the Russian Federation. The U.S. and NATO instigated this war and are giving orders to Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky.

#Lebanon#invasion#Israel#nuclear freeze#protest#Ed Koch#racism#imperialism#antiwar#NoWarWithRussia#StandWithDonbass#StopNATO#Struggle La Lucha

8 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Still, old sources of angst occasionally encroached on Mr. Koch’s post-mayoral life. He shared an apartment building with Mr. Kramer, who mumbled to his dog about “the man who killed all of daddy’s friends” when they passed in the lobby.

The Secrets Ed Koch Carried

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ed Koch

#history#vintage#photography#photograph#ed koch#black and white photography#portrait#politician#political history#us history#american history#american politics#new york city#new york city history#new york#new york history

0 notes

Text

"A Young Girl" by Kathy Acker (High Risk)

So that's what all the fuss is about!

I never liked Kathy Acker. I suspect it might have been timing. I either read her too early, before I wanted to read experimental novels or too late when the "cool" books of my college years were a little embarrassing. I saw her interview William S. Burroughs and she seemed cool but she wasn't writing anything that I liked.

Until I read this story and holy fuck this is amazing. This is raw and crazy and moves along at a speedy clip. It has all the misogyny of a Burroughs book but with Acker, you know she's depicting the nasty and angry mediocre men that she's been dealing with. So it's like Andrea Dworkin writing about her experiences with abuse and her assumption about hateful men but without the essayist need to tell you what it means.

This is also a very 80s story in all the worst/best ways. Think Brett Easton Ellis without the smug cocaine stuff. Think the anger of AIDS victims knowing that the government is fucking them over. They aren't going to be singing on tables. They are living in the poorest neighborhoods but they aren't upset when the homeless people tell them to fuck off.

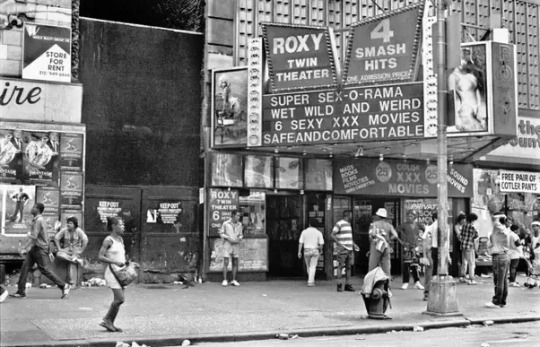

The young girl is being traded off between Mayor ______ and her dad. And who are we kidding, the mayor is obviously Koch who let the city go to Hell and bitched about graffiti. He wasn't the outright gentrification force of Giuliani kicking everyone out of their homes, but he was pushing for the gentrification process that Giuliani would complete. Also Koch was the gay mayor who hid his homosexuality and let the AIDS crisis get just as bad as the Reagan administration.

So it's the mayor and the artist fighting over this girl as she's watching and hearing them all be fucking horrible. The artist is the MALE artist who gets away with hurting women in the name of art. I'm thinking about Roman Polanski but there are so many of them in the world. And of course, he's one of those guys that fucks any woman he wants but if his wife steps out, he's violently divorcing her.

So the ending? The ending has the mayor helping the artist realize his vision of painting a dead or dying girl that looks like her daughter. The mayor claims that he found a corpse in the morgue but he just gets the daughter and ties her up in a car and sets it on fire. And her dad just draws and sketches and doesn't give a shit if it's her. She keeps saying that he doesn't see her, but more likely he sees her and doesn't care.

But the homeless rebel and she gets out and fuck those two.

I guess it's cool that Kathy Acker isn't immune to the happy ending. We've been dragging through the shit.

The one this this reminds me of is the Red Riding Quartet which is all about murder, murdering women, rape and violence with shitty protagonists doing stream of conscious vicious talk. Only the fact that a woman is writing it and the woman doesn't get sacrificed to the plot makes all the difference. I am reading Nineteen Seventy Seven and I love the way it's written but i hate myself for liking it. No such self-loathing with Kathy Acker.

#Kathy Acker#High Risk#Nasty#evil#New York#Mayor Koch#Ed Koch#artists#misogynists#nasty people#homeless#slums#blood art#we are all damned#sinners all

0 notes

Text

Jean-Michel Basquiat is too often under-curated. Consider the bland, context-less survey on view earlier this year at the Brant Foundation’s New York space, a private museum project of President Trump’s childhood friend Peter Brant, or the Brooklyn Museum’s 2018 “One Basquiat,” an “exhibition” consisting of a single $110.5-million-dollar painting. An easy reliance on the aura of this famous black artist with a high market value and a fatal heroin addiction often takes the place of any insightful narration. His name is enough to draw in hordes.

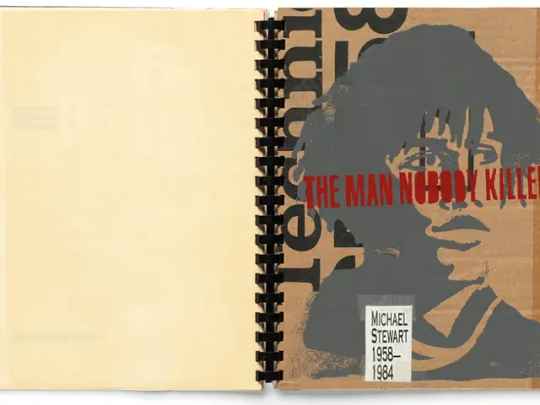

“Basquiat’s ‘Defacement’: The Untold Story,” an exhibition on view at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York through November 6, centers on the artist’s 1983 painting Defacement (The Death of Michael Stewart), which depicts an instance of police violence that occurred in September of that year. After allegedly tagging a wall in the East Village’s First Avenue subway station, Michael Stewart, a twenty-five-year-old black artist from Brooklyn, was beaten by the New York City Transit Police, put into a chokehold, and handcuffed to his bed while comatose at Bellevue Hospital in Manhattan. He died thirteen days later from cardiac arrest. The specifics of the attack are contested—Did Stewart attempt to flee? Did he become violent?—but to me, they don’t matter. Stewart is still dead. Stewart will always be dead. That matters.

And such mattering matters to the occasion of the exhibition itself. Chaédria LaBouvier, the show’s guest curator, is the first black person to single-handedly organize an exhibition at the Guggenheim, which was founded in 1939. There is no way the show would have been possible without Black Lives Matter, and the discussions around state violence and blackness that the movement mainstreamed. “Basquiat’s ‘Defacement’” could be seen as an attempt on the part of the Guggenheim to reach outside its spiral shell and address issues of racial injustice, or it could suggest opportunism and politicking.

In addition to the title painting, the impeccably researched exhibition features works by other artists, including David Hammons, Keith Haring, Lyle Ashton Harris, and Andy Warhol, that deal with Stewart’s death; archival materials like buttons, a protest flyer made by David Wojnarowicz, and posters for benefit performances and parties raising money for Stewart’s family to pursue legal action following his death and the officers’ acquittal; and paintings that Basquiat created in the years prior to the 1983 incident, including Irony of a Negro Policeman (1981), La Hara (1981), Untitled (Sheriff), 1981, and CPRKR (1982), that share themes concerning oppression and the violence engendered by racism and capitalism. The assortment of works on view makes the exhibition seem larger than its two rooms, but the focus and political angle feel so tight that the effect is almost suffocating.

There are two main reasons to step into this claustrophobic space, each compelling in its own right: The Death of Michael Stewart and the art of Michael Stewart. Soon after Stewart’s death, Basquiat, using acrylic paint and marker, made The Death of Michael Stewart on a wall of Haring’s studio. After Basquiat died, of an overdose at the age of twenty-seven, Haring cut the painting out of the wall, had it placed in an ornate frame, and hung it over his bed, where it remained until he died from AIDS complications in 1990. Depicting two baton-wielding pink-faced cops flanking a limbless black figure, the work is devoid of the signature Basquiat symbols that have been used for tattoos a million times over: the crowns, the African masks. Instead, we get the scrawled term ¿DEFACIMENTO©?—a questioning of the police account of Stewart’s death—and a deluge of white space, which make the painting feel all the more urgent. A small collection of Stewart’s own line-obsessed abstract sketches, of which no photographs are allowed, is encased in a glass vitrine. Would the art of Michael Stewart come to us without the death of Michael Stewart? Would his work be exhibited if it weren’t for the spectacle of his suffering and for his memorialization by Basquiat?

The Death of Michael Stewart was not originally meant to be viewed by the public. But Basquiat arguably always kept some sense of an audience in mind, even when he was working in relative anonymity at the start of his career, spray-painting buildings in downtown Manhattan with poetic lines using the tag SAMO©. By the time he created The Death of Michael Stewart, he must have known that, given his success, most of his work would eventually circulate. Perhaps he also knew that everyone loves a dead black man.

Jean-Michel Basquiat is too often under-curated. Consider the bland, context-less survey on view earlier this year at the Brant Foundation’s New York space, a private museum project of President Trump’s childhood friend Peter Brant, or the Brooklyn Museum’s 2018 “One Basquiat,” an “exhibition” consisting of a single $110.5-million-dollar painting. An easy reliance on the aura of this famous black artist with a high market value and a fatal heroin addiction often takes the place of any insightful narration. His name is enough to draw in hordes.

“Basquiat’s ‘Defacement’: The Untold Story,” an exhibition on view at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York through November 6, centers on the artist’s 1983 painting Defacement (The Death of Michael Stewart), which depicts an instance of police violence that occurred in September of that year. After allegedly tagging a wall in the East Village’s First Avenue subway station, Michael Stewart, a twenty-five-year-old black artist from Brooklyn, was beaten by the New York City Transit Police, put into a chokehold, and handcuffed to his bed while comatose at Bellevue Hospital in Manhattan. He died thirteen days later from cardiac arrest. The specifics of the attack are contested—Did Stewart attempt to flee? Did he become violent?—but to me, they don’t matter. Stewart is still dead. Stewart will always be dead. That matters.

And such mattering matters to the occasion of the exhibition itself. Chaédria LaBouvier, the show’s guest curator, is the first black person to single-handedly organize an exhibition at the Guggenheim, which was founded in 1939. There is no way the show would have been possible without Black Lives Matter, and the discussions around state violence and blackness that the movement mainstreamed. “Basquiat’s ‘Defacement’” could be seen as an attempt on the part of the Guggenheim to reach outside its spiral shell and address issues of racial injustice, or it could suggest opportunism and politicking.

In addition to the title painting, the impeccably researched exhibition features works by other artists, including David Hammons, Keith Haring, Lyle Ashton Harris, and Andy Warhol, that deal with Stewart’s death; archival materials like buttons, a protest flyer made by David Wojnarowicz, and posters for benefit performances and parties raising money for Stewart’s family to pursue legal action following his death and the officers’ acquittal; and paintings that Basquiat created in the years prior to the 1983 incident, including Irony of a Negro Policeman (1981), La Hara (1981), Untitled (Sheriff), 1981, and CPRKR (1982), that share themes concerning oppression and the violence engendered by racism and capitalism. The assortment of works on view makes the exhibition seem larger than its two rooms, but the focus and political angle feel so tight that the effect is almost suffocating.

There are two main reasons to step into this claustrophobic space, each compelling in its own right: The Death of Michael Stewart and the art of Michael Stewart. Soon after Stewart’s death, Basquiat, using acrylic paint and marker, made The Death of Michael Stewart on a wall of Haring’s studio. After Basquiat died, of an overdose at the age of twenty-seven, Haring cut the painting out of the wall, had it placed in an ornate frame, and hung it over his bed, where it remained until he died from AIDS complications in 1990. Depicting two baton-wielding pink-faced cops flanking a limbless black figure, the work is devoid of the signature Basquiat symbols that have been used for tattoos a million times over: the crowns, the African masks. Instead, we get the scrawled term ¿DEFACIMENTO©?—a questioning of the police account of Stewart’s death—and a deluge of white space, which make the painting feel all the more urgent. A small collection of Stewart’s own line-obsessed abstract sketches, of which no photographs are allowed, is encased in a glass vitrine. Would the art of Michael Stewart come to us without the death of Michael Stewart? Would his work be exhibited if it weren’t for the spectacle of his suffering and for his memorialization by Basquiat?

The Death of Michael Stewart was not originally meant to be viewed by the public. But Basquiat arguably always kept some sense of an audience in mind, even when he was working in relative anonymity at the start of his career, spray-painting buildings in downtown Manhattan with poetic lines using the tag SAMO©. By the time he created The Death of Michael Stewart, he must have known that, given his success, most of his work would eventually circulate. Perhaps he also knew that everyone loves a dead black man.

#Black Ghosts: Basquiat’s “Defacement” at the Guggenheim#Defacement#Basquiat#Jean Michel Basquiat#Michael Stewart#cops#nyctc#nyc#ed koch#fuck koch#street Artists#Graffiti#The Death of Michael Stewart was not originally meant to be viewed by the public. But Basquiat arguably always kept some sense of an audien#spray-painting buildings in downtown Manhattan with poetic lines using the tag SAMO©. By the time he created The Death of Michael Stewart#most of his work would eventually circulate. Perhaps he also knew that everyone loves a dead black man.

0 notes

Text

youtube

#nyc#documentary#the coolest year in hell#1977#blackout#son of sam#hip hop#bboys#rock steady crew#the bronx#queens#manhattan#ed koch#graffiti#vh1#Youtube

0 notes

Text

Mentally, I'm always noshing.

- Mayor Ed Koch

0 notes

Text

Footnote 3 in “My Government Means To Kill Me” is all about the New York Mayor who missed the moment.

0 notes

Text

A little Tim and Ed story: while in Australia they went to an Aussie Rules game between the two worst teams. Tim tried to teach Ed the rules but Ed says he doesn't think Tim actually knew them either. Anyway, about 10 minutes into the game they started loudly discussing their top 5 musicals instead.

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

Con-Tinual: Action and Adventure!

It’s Action! It’s Adventure! Join Stuart Jaffe, A. L. Kaplan, Gini Koch, Ed McKeown, and host James P. Nettles loading their rucksacks for some of their favorite adventures on the page and screen, and how it’s made its way into their own work!

#ConTinual #fandom #action #adventure #movies #tv #film #books #novels

Watch It Here!

MARK OF THE GODDESS

Sometimes a blessing can be a curse.

Young…

View On WordPress

#A. L. Kaplan#Action#Action and Adventur#adventure#books#ConTinual#Ed McKeown#Fandom#Fantasy#Gini Koch#James P. Nettles#movies#novels#Science Fiction#Stuart Jaffe#tv

0 notes

Quote

Edward I. Koch looked like the busiest septuagenarian in New York.

Glad-handing well-wishers at his favorite restaurants, gesticulating through television interviews long after his three terms as mayor, Mr. Koch could seem as though he was scrambling to fill every hour with bustle. He dragged friends to the movies, pursuing a side career in film criticism. He urged new acquaintances to call him “judge,” a joking reference to his time presiding over “The People’s Court.”

But as his 70s ticked by, Mr. Koch described to a few friends a feeling he could not shake: a deep loneliness. He wanted to meet someone, he said. Did they know anyone who might be “partner material?” Someone “a little younger than me?” Someone to make up for lost time?

“I want a boyfriend,” he said to one friend, Charles Kaiser.

It was an aching admission, shared with only a few, from a politician whose brash ubiquity and relentless New York evangelism helped define the modern mayoralty, even as he strained to conceal an essential fact of his biography: Mr. Koch was gay.

The Secrets Ed Koch Carried

0 notes