#spray-painting buildings in downtown Manhattan with poetic lines using the tag SAMO©. By the time he created The Death of Michael Stewart

Text

Jean-Michel Basquiat is too often under-curated. Consider the bland, context-less survey on view earlier this year at the Brant Foundation’s New York space, a private museum project of President Trump’s childhood friend Peter Brant, or the Brooklyn Museum’s 2018 “One Basquiat,” an “exhibition” consisting of a single $110.5-million-dollar painting. An easy reliance on the aura of this famous black artist with a high market value and a fatal heroin addiction often takes the place of any insightful narration. His name is enough to draw in hordes.

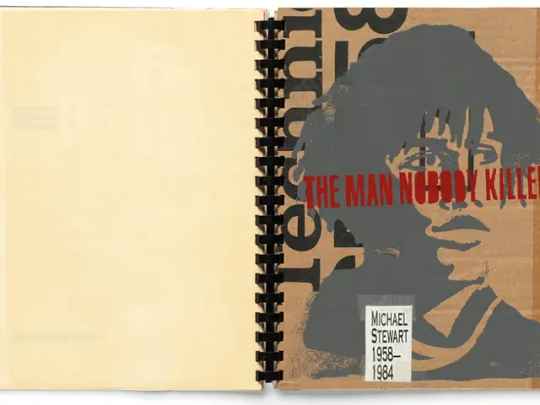

“Basquiat’s ‘Defacement’: The Untold Story,” an exhibition on view at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York through November 6, centers on the artist’s 1983 painting Defacement (The Death of Michael Stewart), which depicts an instance of police violence that occurred in September of that year. After allegedly tagging a wall in the East Village’s First Avenue subway station, Michael Stewart, a twenty-five-year-old black artist from Brooklyn, was beaten by the New York City Transit Police, put into a chokehold, and handcuffed to his bed while comatose at Bellevue Hospital in Manhattan. He died thirteen days later from cardiac arrest. The specifics of the attack are contested—Did Stewart attempt to flee? Did he become violent?—but to me, they don’t matter. Stewart is still dead. Stewart will always be dead. That matters.

And such mattering matters to the occasion of the exhibition itself. Chaédria LaBouvier, the show’s guest curator, is the first black person to single-handedly organize an exhibition at the Guggenheim, which was founded in 1939. There is no way the show would have been possible without Black Lives Matter, and the discussions around state violence and blackness that the movement mainstreamed. “Basquiat’s ‘Defacement’” could be seen as an attempt on the part of the Guggenheim to reach outside its spiral shell and address issues of racial injustice, or it could suggest opportunism and politicking.

In addition to the title painting, the impeccably researched exhibition features works by other artists, including David Hammons, Keith Haring, Lyle Ashton Harris, and Andy Warhol, that deal with Stewart’s death; archival materials like buttons, a protest flyer made by David Wojnarowicz, and posters for benefit performances and parties raising money for Stewart’s family to pursue legal action following his death and the officers’ acquittal; and paintings that Basquiat created in the years prior to the 1983 incident, including Irony of a Negro Policeman (1981), La Hara (1981), Untitled (Sheriff), 1981, and CPRKR (1982), that share themes concerning oppression and the violence engendered by racism and capitalism. The assortment of works on view makes the exhibition seem larger than its two rooms, but the focus and political angle feel so tight that the effect is almost suffocating.

There are two main reasons to step into this claustrophobic space, each compelling in its own right: The Death of Michael Stewart and the art of Michael Stewart. Soon after Stewart’s death, Basquiat, using acrylic paint and marker, made The Death of Michael Stewart on a wall of Haring’s studio. After Basquiat died, of an overdose at the age of twenty-seven, Haring cut the painting out of the wall, had it placed in an ornate frame, and hung it over his bed, where it remained until he died from AIDS complications in 1990. Depicting two baton-wielding pink-faced cops flanking a limbless black figure, the work is devoid of the signature Basquiat symbols that have been used for tattoos a million times over: the crowns, the African masks. Instead, we get the scrawled term ¿DEFACIMENTO©?—a questioning of the police account of Stewart’s death—and a deluge of white space, which make the painting feel all the more urgent. A small collection of Stewart’s own line-obsessed abstract sketches, of which no photographs are allowed, is encased in a glass vitrine. Would the art of Michael Stewart come to us without the death of Michael Stewart? Would his work be exhibited if it weren’t for the spectacle of his suffering and for his memorialization by Basquiat?

The Death of Michael Stewart was not originally meant to be viewed by the public. But Basquiat arguably always kept some sense of an audience in mind, even when he was working in relative anonymity at the start of his career, spray-painting buildings in downtown Manhattan with poetic lines using the tag SAMO©. By the time he created The Death of Michael Stewart, he must have known that, given his success, most of his work would eventually circulate. Perhaps he also knew that everyone loves a dead black man.

Jean-Michel Basquiat is too often under-curated. Consider the bland, context-less survey on view earlier this year at the Brant Foundation’s New York space, a private museum project of President Trump’s childhood friend Peter Brant, or the Brooklyn Museum’s 2018 “One Basquiat,” an “exhibition” consisting of a single $110.5-million-dollar painting. An easy reliance on the aura of this famous black artist with a high market value and a fatal heroin addiction often takes the place of any insightful narration. His name is enough to draw in hordes.

“Basquiat’s ‘Defacement’: The Untold Story,” an exhibition on view at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York through November 6, centers on the artist’s 1983 painting Defacement (The Death of Michael Stewart), which depicts an instance of police violence that occurred in September of that year. After allegedly tagging a wall in the East Village’s First Avenue subway station, Michael Stewart, a twenty-five-year-old black artist from Brooklyn, was beaten by the New York City Transit Police, put into a chokehold, and handcuffed to his bed while comatose at Bellevue Hospital in Manhattan. He died thirteen days later from cardiac arrest. The specifics of the attack are contested—Did Stewart attempt to flee? Did he become violent?—but to me, they don’t matter. Stewart is still dead. Stewart will always be dead. That matters.

And such mattering matters to the occasion of the exhibition itself. Chaédria LaBouvier, the show’s guest curator, is the first black person to single-handedly organize an exhibition at the Guggenheim, which was founded in 1939. There is no way the show would have been possible without Black Lives Matter, and the discussions around state violence and blackness that the movement mainstreamed. “Basquiat’s ‘Defacement’” could be seen as an attempt on the part of the Guggenheim to reach outside its spiral shell and address issues of racial injustice, or it could suggest opportunism and politicking.

In addition to the title painting, the impeccably researched exhibition features works by other artists, including David Hammons, Keith Haring, Lyle Ashton Harris, and Andy Warhol, that deal with Stewart’s death; archival materials like buttons, a protest flyer made by David Wojnarowicz, and posters for benefit performances and parties raising money for Stewart’s family to pursue legal action following his death and the officers’ acquittal; and paintings that Basquiat created in the years prior to the 1983 incident, including Irony of a Negro Policeman (1981), La Hara (1981), Untitled (Sheriff), 1981, and CPRKR (1982), that share themes concerning oppression and the violence engendered by racism and capitalism. The assortment of works on view makes the exhibition seem larger than its two rooms, but the focus and political angle feel so tight that the effect is almost suffocating.

There are two main reasons to step into this claustrophobic space, each compelling in its own right: The Death of Michael Stewart and the art of Michael Stewart. Soon after Stewart’s death, Basquiat, using acrylic paint and marker, made The Death of Michael Stewart on a wall of Haring’s studio. After Basquiat died, of an overdose at the age of twenty-seven, Haring cut the painting out of the wall, had it placed in an ornate frame, and hung it over his bed, where it remained until he died from AIDS complications in 1990. Depicting two baton-wielding pink-faced cops flanking a limbless black figure, the work is devoid of the signature Basquiat symbols that have been used for tattoos a million times over: the crowns, the African masks. Instead, we get the scrawled term ¿DEFACIMENTO©?—a questioning of the police account of Stewart’s death—and a deluge of white space, which make the painting feel all the more urgent. A small collection of Stewart’s own line-obsessed abstract sketches, of which no photographs are allowed, is encased in a glass vitrine. Would the art of Michael Stewart come to us without the death of Michael Stewart? Would his work be exhibited if it weren’t for the spectacle of his suffering and for his memorialization by Basquiat?

The Death of Michael Stewart was not originally meant to be viewed by the public. But Basquiat arguably always kept some sense of an audience in mind, even when he was working in relative anonymity at the start of his career, spray-painting buildings in downtown Manhattan with poetic lines using the tag SAMO©. By the time he created The Death of Michael Stewart, he must have known that, given his success, most of his work would eventually circulate. Perhaps he also knew that everyone loves a dead black man.

#Black Ghosts: Basquiat’s “Defacement” at the Guggenheim#Defacement#Basquiat#Jean Michel Basquiat#Michael Stewart#cops#nyctc#nyc#ed koch#fuck koch#street Artists#Graffiti#The Death of Michael Stewart was not originally meant to be viewed by the public. But Basquiat arguably always kept some sense of an audien#spray-painting buildings in downtown Manhattan with poetic lines using the tag SAMO©. By the time he created The Death of Michael Stewart#most of his work would eventually circulate. Perhaps he also knew that everyone loves a dead black man.

0 notes