#Austrian musicals

Text

call me old-fashioned but if someone called me "enchanted starchild/ verwunschenes Sternenkind " I too would let them suck all blood out of me

#tanz der vampire#tdv#dance of the vampires#the fearless vampire killers#Sarah Chagall#Graf von Krolock#Count von Krolock#German Musicals#Austrian musicals#european musicals#musicals#broadway#vampires#total eclipse of the heart#jim steinman#drew sarich#jan ammann#steve barton#thomas borchert#mark seibert#herbert von krolock

214 notes

·

View notes

Text

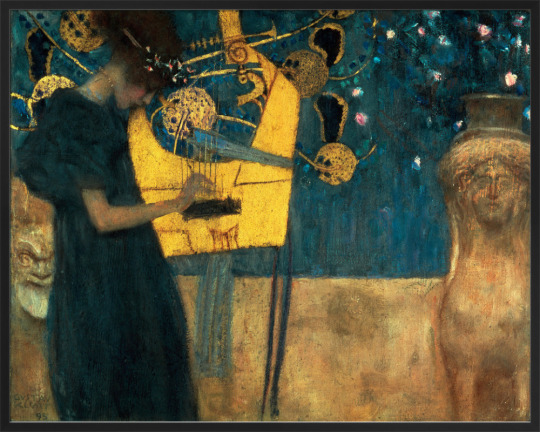

Gustav Klimt

Music

1895

#gustav klimt#austrian artist#austrian painter#austrian art#Austrian painting#aesthetic#beauty#music#music aesthetic#art aesthetic#art nouveau#modern art#art history#aesthetictumblr#tumblraesthetic#tumblrpic#tumblrpictures#tumblr art#tumblrstyle#artists on tumblr

537 notes

·

View notes

Text

Symphony of the Water Nymphs by Hans Zatzka (Late 19th - Early 20th Century)

#hans zatzka#art#paintings#fine art#19th century#19th century art#20th century#20th century art#academism#academicism#academic art#painting#austrian art#austrian artist#mythology#greek mythology#water nymph#naiad#music#classic art

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Joseph Urban (1872-1933), ''Poppyland'' by George Gershwin, 1920

Source

#joseph urban#austrian-american artists#poppyland#george gershwin#sheet music#vintage illustration#art deco

214 notes

·

View notes

Text

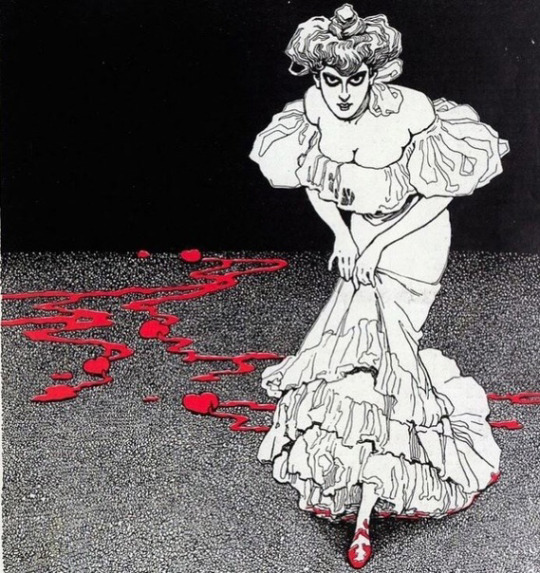

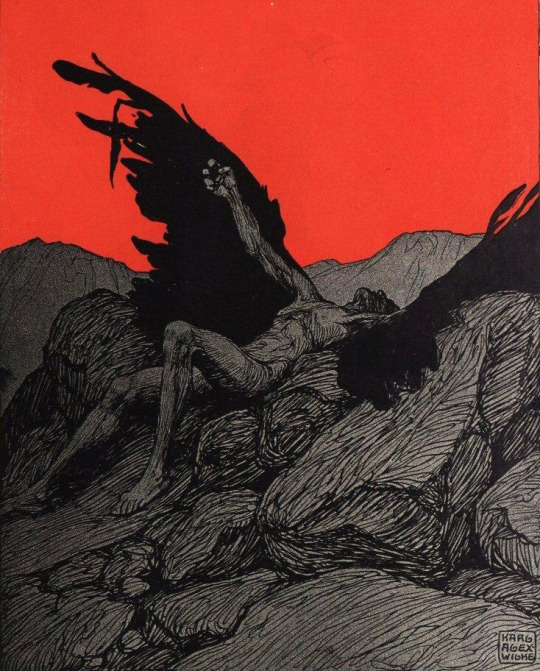

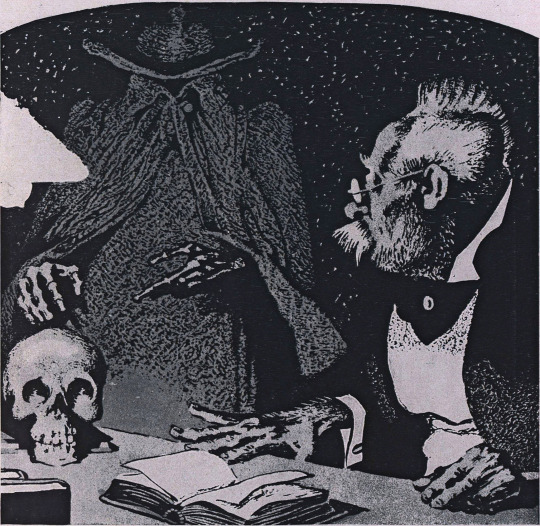

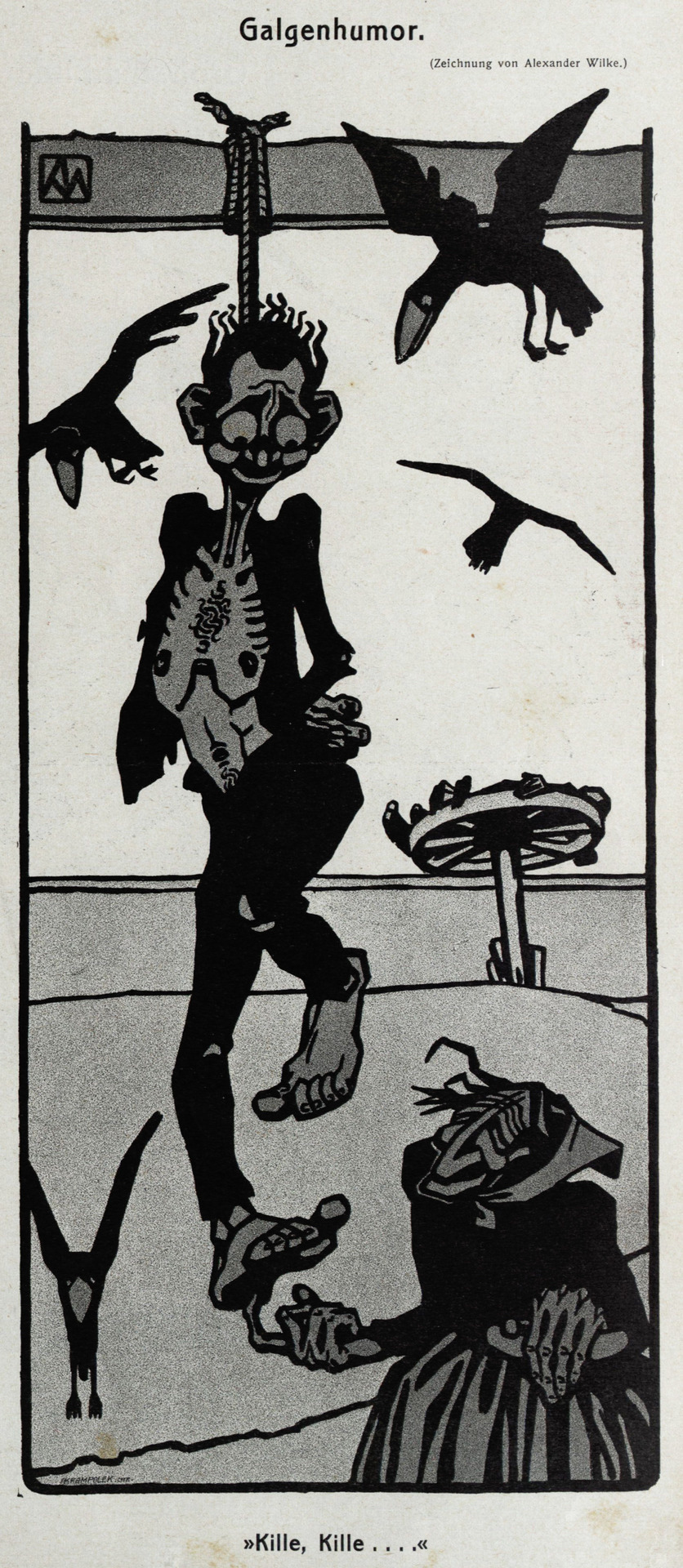

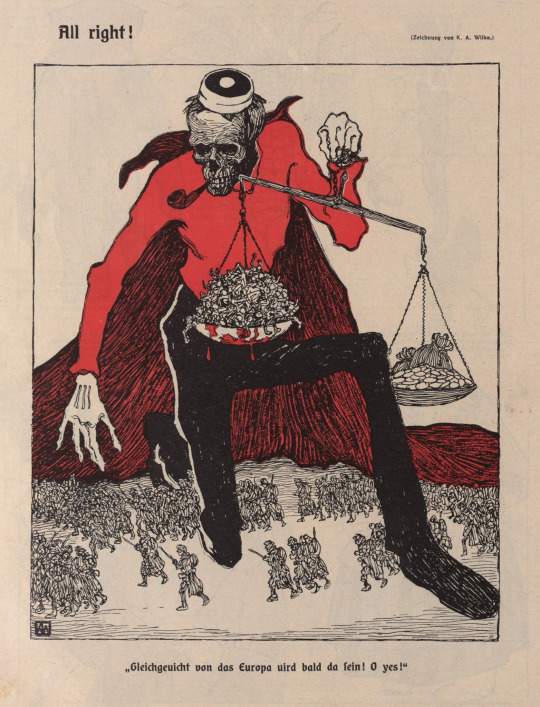

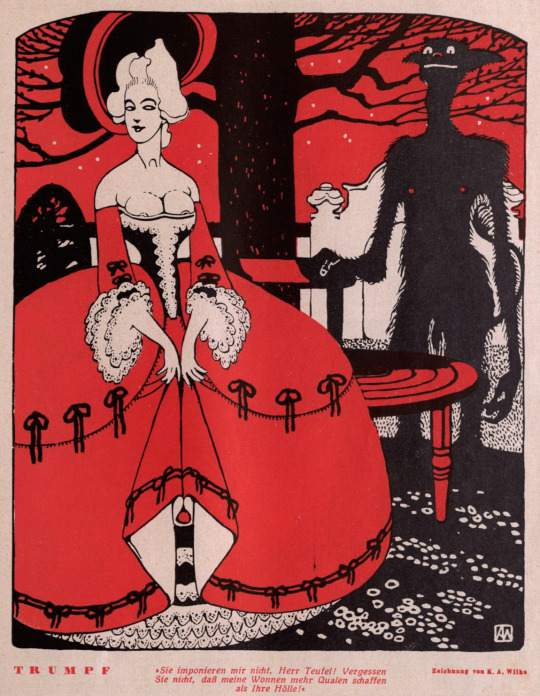

𝙺𝚊𝚛𝚕 𝙰𝚕𝚎𝚡𝚊𝚗𝚍𝚎𝚛 𝚆𝚒𝚕𝚔𝚎 (1879-1954) & 𝚑𝚒𝚜 𝚖𝚊𝚐𝚗𝚒𝚏𝚒𝚌𝚎𝚗𝚝 𝚎𝚗𝚐𝚛𝚊𝚟𝚒𝚗𝚐𝚜.

Karl Alexander Wilke (July 16, 1879 in Leipzig – February 27, 1954 in Vienna) was a German-Austrian painter, illustrator and stage designer. 🎭

#classicart #classicalart #classicpainting #classicalpaintings #zeitgenössischekunst #mfpretty #aesthetic #traditionalart #surreal @frenchpsychiatrymuderedmycnut #surrealart #surrealism #surrealismartcommunity #surrealist #surrealista #surrealistic #surrealisme #surreal_art #surrealismo #surrealpainting

Soundtrack: Opéra by Emmanuel Santarromana

#fucking favorite#karl alexander wilke#7/2023#classic art#surrealist#dark aesthetic#Austria#austrian painter#zeitgenössischekunst#contemporaryart#fable Core#fairy tail#mythology#x-heesy#music#now playing#spotify#music and art#engraving#illustrations#traditional art#österreich#european history

248 notes

·

View notes

Text

Literally why did I have to go and hyperfixate on Elisabeth at the same time as I caught the flu?? Now I wake up several times a night drenched in a cold sweat utterly convinced that I need to do something about the Hapsburg line of succession. This is several days in a row now, my brain can't think of any other material for its fever dreams. Help me.

#me throttling my own brain: SHUT UP ABOUT THE AUSTRIAN MONARCHY SHUT UP#emma talks#elisabeth das musical

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Saturday, it is -13C outside, and going to snow later, I am retailoring an old wool skirt from my grandmother so it fits me, and am making brokkoli creme soup from scratch, because I finally got a handmixer :)

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

'Reigen – Tanz, Musik, Liebe'. Alexander Rothaug. c. 1895.

239 notes

·

View notes

Text

Leopold Pollak (1806-1880)

"A little shepherd playing the oboe at the Claudia Aqueduct on the Roman Campagna" (1857)

Oil on canvas

#paintings#art#artwork#genre painting#male portrait#leopold pollak#oil on canvas#fine art#austrian artist#jewish artist#portrait of a boy#musical instruments#wind instrument#clothing#clothes#1850s#mid 1800s#mid 19th century

122 notes

·

View notes

Text

Just in case it's not Really Obvious from context clues

("What's the deal with the 'Pied Piper' in DSWL?'

'The 'sound of the pied piper' refers to the nationalist and antisemitic slogans of the warmongers and racists that began to rise in Vienna in the last decades of the 19th century.')

source

#musicals#theatre#elisabeth das musical#listen i know most people Know This but. i feel like a not inconsiderable people through fandom history have not dkkfkfkfkf#which is what makes people come up with takes like 'rudolf wanted to be king of hungary' and 'we should get rid of hass' 😭#i mean i guess theres something to be said about the point not being clear enough if the author needs to explain it outside the work#but its clear enough to ME#Like i've said before i think its because people who don't know german (the language) - or european/austrian history - will watch the show#but yeah its so deeply about antisemitism specifically!!! rudolf's sympathetic portrayal is in part meant as a condemnation of it!

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

no because she really is the Wunder, das mit der Wirklichkeit versöhnt <33

#Sarah Chagall#Tanz der Vampire#tdv#dance of the vampires#the fearless vampire killers#graf von krolock#count von krolock#Musical#german musicals#austrian musicals#vampires#jim steinman#Steve Barton#Diana schnierer#Cornelia Zenz

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Die Schatten werden länger

#elisabeth das musical#european musicals#musical theatre#is this austrian or german?#idk#der tod#kronprinz rudolf#uwe kröger#uwe tod#wait who played rudolf in the 1992 prod#andreas bieber#art#my art#digital art#fanart

150 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Karl Kohaut (1726-1784) - Concerto in F Major: I. Allegro ·

Hopkinson Smith · David Courvoisier · David Plantier · Chiara Banchini ·

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

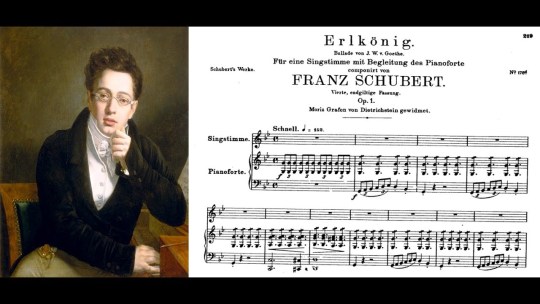

Franz Schubert: the enigma of the man and the musician

If I were to identify the distinctive emotion that pervades Schubert's music, I would say that it is a tragic but reconciled love: love not only for people in all their many predicaments, but also love for music, and especially for the music that was brought to him by his muse....When I think of Schubert's death, and lament that he did not live to the age of Mozart, I think of the love that he longed for and never obtained, and wonder yet more at a musical legacy that contains more consolation for our loneliness than any other human creation.

- Sir Roger Scruton on Franz Schubert (1797-1828)

The story of Austrian composer Franz Schubert (1797–1828) was one of the most tragic in classical music. Schubert died young. Really young. Younger than almost any other famous composer - younger than Mozart, Chopin, or Mendelssohn. He contracted syphilis at 25 and died at 31, which limited his life in many ways but also drove him to be an incredibly prolific composer. His personal life is shrouded in mystery and yet it greatly influenced his music. 2022 marks the 225th anniversary of his birth and perhaps then it’s good time to discuss the man and his music. Can unveiling his life bring into light the tortured genius of his musical compositions? Let us see.

Schubert wasn’t very keen on marriage for many possible reasons, perhaps because he didn’t have enough money, or because he was gay, or because he thought marriage was a bourgeois institution created to force conformity - or none of those things. In any case, he was a bachelor who lived a life of his own choosing. Schubert’s 20s were a lot like many artists’ and other urban dwellers’ 20s today: he was broke most of the time and lived with roommates, he hung out in pubs and drank heavily, he flirted with leftist political movements, and, most importantly, he had a close but ever changing group of friends to explore art, politics, religion, literature, and, of course, music.

Born in 1797 in Vienna, Schubert grew up with a strict schoolteacher father who encouraged his musical pursuits. Schubert first left home at the age of 11 to serve as a choirboy in the imperial court chapel, a position that included a scholarship to an elite school (“the principal Viennese boarding school for non-aristocrats” according to Grove Music Online). During Schubert’s five years there, he met the first members of what would become his adult circle of friends. Their help later proved instrumental in getting him out of his father’s house and off the path to becoming a schoolteacher, a low-level civil servant job, like his father.

Schubert didn’t just come from a strict family, he also lived in a rather strict society. In the aftermath of two successive defeats by Napoleon during Schubert’s childhood, Austria reverted back to a repressive political regime. He spent his entire adult life in a society with strict government censorship and powerful secret police, and he chafed under the limits of his freedom at various times. In 1816, a year after the passage of a law that barred men of lower social classes from marrying unless they had sufficient income, Schubert wrote a tortured diary entry disparaging marriage and the monarchy.

In 1820, Schubert attended a party that was raided by the police. He spent the night in jail, and his friend the political activist Johann Senn was jailed for over a year and then exiled to his native Austrian Tyrol. Later on, Schubert worked on the opera Der Graf von Gleichen even though he knew its plot about bigamy had no chance of making it past the censors.

Schubert was subject to strong controlling forces during his lifetime so perhaps it was natural that of his many friends, the closest was Franz von Schober, a gregarious nobleman who had a reputation as a sort-of self-indulgent pleasure seeker. It seems that everyone who knew Schober either loved or hated him.

Many thought he was a bad influence on Schubert, and various mutual friends left negative characterisations of him. According to one, “Schober surpasses us all in mind, and even more so in speech! Yet there is much about him that is artificial, and his best powers threaten to be suffocated by idleness.” Schubert was much more dedicated to his creative work than Schober but he was irresistibly attracted to Schober’s uninhibited way of living. When Schubert first moved out of his father’s home to try to make his living as a musician, he moved into the Schober family flat in central Vienna, and Schober later took credit for liberating Schubert from the life of a schoolteacher.

Given that Schubert was something of a non-conformist, it’s ironic that he was most popular in his lifetime for domestic music. Written for amateurs, music for the home was part of the culture of cozy domesticity in Biedermeier Vienna. And like many Viennese, Schubert avidly participated in home music making throughout his life. He wrote and published many songs and short pieces for piano solo or duo (two people playing one piano). Schubert’s first big hit was Erlkönig. He wrote it in 1815 and it was performed five years later at a private home and then publicly soon after. It promptly exploded in popularity and was published as his Op. 1. A song about death pursuing a child, it features a vivid accompaniment portraying a horse trying to outrun death. The song is both totally genius and clearly written by a melodramatic 18-year-old.

In early 1821, around the time Erlkönig was starting to get noticed, Schubert’s circle of friends began to have their first official Schubertiads, a clever name they came up with to describe evenings devoted to Schubert’s music. Schober was one of the primary participants and they often took place at his home. These performances of Schubert’s music and the encouragement of his friends were major catalysts to his career.

Like most children growing up, I learned to play the piano and so from an early age I was always a fan of piano sonatas. With solo piano, there is nowhere to hide. Without the cover of an orchestra, the details of every part - melody, counterpoint, harmony, and rhythm - are all exposed. The genius of the work is thus revealed, as well as the personality of the composer.

Every note is a clue to who the writer is. Schubert may have been a shy and retiring gentleman, but he was full of mischief, mystery, and wonder. His piano sonatas are an incredible contribution to our heritage and reveal him as a man with a limitless interior landscape of emotion. There is enough polite, baroque gaiety to enjoy, but on closer examination, Schubert’s sonatas reveal sensitively expressed romance, pathos, and yearning.

The Fantasy in C, Op. 15, more commonly known as The ‘Wanderer’ Fantasy, was written for solo piano in 1822, and is one of Schubert’s most well-known and frequently performed works. It is considered one of the greatest compositions in the entire piano repertoire. This four-movement fantasy is linked by a unifying theme with each movement flowing into the next, starting with a variation of the opening phrase from a former composition ‘Der Wanderer.’ This lied (poem set to music) was originally composed in 1816 for piano and voice with lyrics and title derived from a poem by Georg Philipp Schmidt von Lübeck.

The ‘Wanderer’ Fantasy is considered his most challenging work; he is quoted to have barely the ability to play it himself. Composed during the post-Enlightenment, the fantasy alludes to the onset of changing tastes - the complexity, the sense of searching, and his contemporary time itself. Musically it is incredible; as a cultural reference, it is absolutely magnetic. In the song, the wanderer seeks a distant paradise but cannot find it anywhere among men: “Where are you, my dear land? Sought and brought to mind, yet never known. …” Searching for happiness, the wanderer asks, “where?” and a ghostly breath answers, “There, where you are not, there is your happiness.”

The ‘Wanderer’ Fantasy broke away from the classical form in that it was created to be performed without a break between the movements. Both the virtuosity and structure captivated other Romantic era composers, most intently the Hungarian composer Franz Liszt, who transcribed it for piano and orchestra. Editing Schubert’s original score, Liszt rearranged the final movement and added alternative passages into the fantasy.

There are over 900 works by Schubert to explore, ranging from traditional Viennese waltzes like the dreamscape ‘Serenade’ for full orchestra, viola, or cello to his poetic lieder. ‘Erlkönig’ (translated as ‘king of the fairies’) is one of Schubert’s more preeminent lieder. Set to Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s poem of the same name, it is a dramatic and challenging composition that is widely regarded as a masterpiece of the early Romantic era.

The lied tells the story of a father who swiftly rides home on horseback, holding his anxious and feverish son. As the story unfolds, the child experiences “hallucinations” of the malevolent spirit of the Erlking (personification of death) that tries to lure the boy. As they race through the forest, the frightened father tries to console his child by defining the supernatural experiences as mere natural causes: a streak of fog, rustling leaves, and the shimmering willows. When they reach home, the father discovers that his son has died.

Schubert was only 18 years of age when he created this evocative and theatrical composition in 1815. Composed for vocals and piano accompaniment, the song features four characters - narrator, father, son, and the Erlking - all sung by a single vocalist. All characters are sung in the minor key except the Erlking, whose character is sung in the major key.

‘Erlkönig’ is an extremely unusual composition in several ways. There are features that, taken abstractly, would seem to demonstrate a lack of familiarity with the musical conventions of the early 19th century. And while there are many possible poetic interpretations of these moments, they often fall short of explaining why Schubert departed so far from the style of his time. The accompaniment, with its incessant vibrations, is strange piano writing. The resulting music could be taken as an illustration of the horse’s clopping hooves - at least an abstract illustration, since a horse has (obviously) four legs, not three or six, as the triplet motion would suggest. (The song ‘Gretchen at the Spinning Wheel,’ for example, sounds far more ‘realistic.’)

In the setting of the line “My son, it’s a wisp of fog,” the dissonance, on the word “son,” is so irregularly composed as to be provocative. A naked major second is resolved upwards (wrong!) to a unison (wrong!!!!). In the musical language of the early 19th century, it was impossible to treat a dissonance more incorrectly.

The ending is unusually abrupt. The boy’s suffering is portrayed vividly in music, but his death itself is not illustrated. There’s a brief phrase, quasi recitativo, a pair of piano chords, and nothing more. The chords are long, not staccato, and there is no fermata.

In Schubert’s time, death was conventionally illustrated by a grand pause in all the instruments. It is extremely unlikely that he wasn’t aware of this - even if he had never explicitly learned the rhetorical device, he would certainly have had enough experience of this convention as listener. A grand pause would have been the obvious choice for this moment, and it’s striking that Schubert didn’t make that choice. The key to the interpretation of the work lies in this decision.

To understand Schubert’s compositional choices, let’s return to the original poem. What is the text really about? There is strong evidence that the poem is describing the rape of a child - from the perspective of the perpetrator.

Goethe gives the most space in his poem to the emotions of the Erlkönig, who is responsible for the child’s death. The pain of the father, who holds his expiring son in his arms, is also explored thoroughly. Yet the suffering of the child himself seems barely worth mentioning to Goethe. He devotes little space to the boy’s pain, and when he does speak, his words feel strangely artificial - he says, “Erlkönig has done me harm.” This oddly formal phrase sounds hollow coming out of a child’s mouth.

Erlkönig says to the boy, “I love you, I’m charmed by your beautiful form.” (Charmed, in German, is reizen, which can also mean excited or even aroused.) Erlkönig has a crown and a symbolic, phallic tail.

Erlkönig then threatens, “If you’re not willing, I’ll have to use force.” (Force is Gewalt, which can also mean violence, and which forms the centre of the word for rape, Vergewaltigung.) This line is abhorrent to our contemporary ears, trained as we are in the inviolability of sexual consent.

But it’s worth remembering that this would have sounded different - even routine - in Goethe’s time. Rape within marriage was legal and socially acceptable; the distinction between seducing and forcing someone to do something was far more blurred; weaker groups in society had little recourse to justice. Goethe himself wrote a line saying “I loved boys, but prefer to love girls / If I’ve had my fill of them as girls, I’ll avail myself of them as boys,” without fear of censure. We must assume that these girls, if they were unwilling to be used anally, were taken for this purpose by force.

Schubert’s setting of ‘Erlkönig’ is mostly free, associative. Besides the return of the introductory triplet motive, there are few formal connections or structures to be found. That makes the harmonic and melodic parallels between the lines “He holds him secure, he holds him warm” and “Erlkönig has done me harm” impossible to overlook. The harmonies are exactly the same - they haven’t even been transposed - and only a single chord is left out.

Here, the melodic material that kept the boy secure and warm becomes the cry of the dying - or arguably, raped - child. Schubert is perhaps telling us who the perpetrator is. The secure, warm touch of the father becomes the suffering he inflicts on his son. And the strange dissonance set to the word “son” takes on a new meaning. Clearly, something is not right. This father-son relationship is distorted, perverted.

There is a sexual image in the accompanying right-hand triplet figure. Imagine the right hand, playing the constant up-and-down vibrations of Schubert’s triplets, taken away from the keyboard and rotated 90 degrees so that the thumb is facing away from the body; now imagine this same motion performed on the penis. It is the motion of masturbation. Here, Schubert pushes his naturalism to its limits. If we assume that the perpetrator was right-handed, which he very likely was (85% of people are), then he would have masturbated with his right hand. And the way Schubert builds his song to its climax is analogous to the male orgasm.

The ending is direct and illustrative. Instead of the grand pause that would appropriately depict the child’s death, we get music and words that are analogous to the end of a rape. Excuse the blunt language: in “He reaches the farmhouse with effort and urgency,” the father ejaculates; in “In his arms the child,” he pulls his pants up; and finally, in “was dead,” he zips up his fly, completing the act.

It seems improbable that Schubert used this song to directly process childhood trauma. But it’s obvious that he is, at least unconsciously, reporting from a harrowing experience. In his famous short story “My Dream,” he writes the following: “…My father took me once again into his favourite garden. He asked me if I liked it. But the garden was wholly repellent to me and I dared not say so. Then, flushing, he asked me a second time: did the garden please me? Trembling, I denied it. Then my father struck me and I fled.”

Could it be that the garden his father was so fond of, that was so abhorrent to little Franz, was the genital region of his father, with an overgrowth of pubic hair? In “My Dream,” a heartrending passage follows the story of the garden. “When I would sing of love, it turned to pain. And again, when I would sing of pain, it turned to love. Thus love and pain divided me,” Schubert wrote. If Schubert did suffer abuse as a child, this would take on an entirely new meaning. Instead of alluding to some diffuse sense of romantic melancholy, it would be a document of the abuse he suffered; and, moreover, of the stunted emotional life to which he was condemned. That’s just one interpretation that I’ve come to mull over after being provoked by other more musically qualified friends versed in classical music and in particular the life and works of Schubert himself.

Another of my favourite pieces by Schubert has been String Quartet No. 14, also known as ‘Death and the Maiden’. This was composed in 1824 after Schubert learned of his imminent death. In 1822, the now-successful, well-received Schubert contracted syphilis, which would go on to destroy his health, his good spirits, and ultimately his life. It was during this period of decline that he created his String Quartet No. 14, slotting ‘Death and the Maiden’ into the quartet’s second movement. He was in a much gloomier place in life, he confessed in a March 1824 letter to his friend, Leopold Kupelwieser.

“I find myself to be the most unhappy and wretched creature in the world. Imagine a man whose health will never be right again, and who in sheer despair continually makes things worse and worse instead of better; imagine a man, I say, whose most brilliant hopes have perished, to whom the felicity of love and friendship have nothing to offer but pain at best, whom enthusiasm (at least of the stimulating variety) for all things beautiful threatens to forsake, and I ask you, is he not a miserable, unhappy being? ‘My peace is gone, my heart is sore, I shall find it nevermore,’ I might as well sing every day now, for upon retiring to bed each night I hope that I may not wake again, and each morning only recalls yesterday’s grief.”

The quartet was inspired by one of his earlier lieder, using the same title, and was originally set to a poem by German poet Matthias Claudius. The theme of the quartet is a death toll about the terror of dying and the hopeful anticipation of the comfort and peace that follows. In the dialogue between the maiden and death, the young woman fearfully casts death away, crying out: “Go, savage man of bone! I am still young - go!”

The verse sung by “Death” in Schubert’s lied reads:

“Give me your hand, you fair and tender creature;

I am a friend and do not come to punish you.

Be of good cheer! I am not savage,

Gently you will sleep in my arms.”

And yet, his Quartet No. 14, ‘Death and the Maiden,’ came from that place. Which, to me, explains how, and why, the quartet has such power. And, as you’ll come to hear, it’s a world apart from his 1817 song.

The second movement of the quartet is nuanced, mysterious, heartbreaking, and, curiously, utterly seductive, with its two distinct voices. And, surely, far more personal to Schubert than the song had been. Because now, battling illness, depression, the realities of an illness that gets treated with mercury, whereby you either die or syphilis or mercury poisoning, Schubert gets it. It’s not just the maiden that Death is after. It’s Schubert.

Here’s the Borromeo Quartet (Nicholas Kitchen and Kristopher Tong, violins; Mai Motobuchi, viola; Yeesun Kim, cello) in a fabulous rendition:

youtube

Despite Schubert’s illness and depression, he continued to write tuneful, light music that evoked warmth and comfort. The String Quartet No. 14 was first played privately in 1826 and not published until 1831, three years after his death.

To make time to write The ‘Wanderer’ Fantasy for the wealthy patron Carl Emanuel Liebenberg von Zsittin, Schubert stopped writing what would come to be known as the ‘Unfinished Symphony.’ Unfortunately, the ‘Unfinished Symphony’ remained unfinished, and The ‘Wanderer’ Fantasy wasn’t performed in public until 1832, long after the composer’s death.

If there was any doubt about Schubert’s pure emotionality, the drama of the ‘Unfinished Symphony,’ also known as Symphony No. 8, will quickly dispel all doubts. Although the symphony is missing its finale, which would complete the musical form, it is not lacking in any other sense. Due to the lyrical drive of the dramatic structure, the unfinished Symphony No. 8 is often referred to as the very first Romantic symphony, which cements Schubert’s place in the annals of music history. The bold symphonic scope of Schubert’s music as well as its dramatic power and emotional tension celebrate him as a “romantic” who influenced the next group of musical legends such as Franz Liszt and Richard Strauss.

Yet, even at the height of the Schubertiads, when his songs and piano pieces were selling, Schubert wanted to make his name outside the publications that fueled the home music market. In addition to composing nine symphonies, working on a handful of operas that he left in various stages of completeness, and writing string quartets and piano trios, he also worked to bring the smaller genres that he was famous for into the concert hall. He made them longer, more ambitious, and more virtuosic. One such example is “Lebensstürme,” a movement for piano duo. It may have been intended as the first movement of a four-movement work (the name ‘Lebensstürme’ - Storms of Life - was added after Schubert’s death).

Over all then, Schubert is difficult to characterise. Schubert disdained many aspects of traditional bourgeois life, particularly regular employment, institutional religion, conformist thinking, and marriage. Freedom - political, personal, professional, and creative - was extremely important to the way Schubert sought to live his life. And yet he held strong anti-establishment views while profiting from the celebration of “hearth, heart, and home” that was Biedermeier Vienna. He composed tirelessly and still found time for a very active social life.

It’s also hard to get a sense of his personality from his friends’ reminiscences of him. Many who knew him described him as having a dual nature. One example, and probably the harshest, was by Josef Kenner, who said that Schubert’s “body, strong as it was, succumbed to the cleavage in his - souls - as I would put it, of which one pressed heavenwards and the other bathed in slime.” Quotes like that raise more questions than they answer but they point to the fact that Schubert lived a marginal existence in a society that celebrated loyalty to the family and the state.

If Schubert the man was hard to fathom, there is no doubt about Schubert the musician composer. t’s easy to see why his work is considered in the same league as the works of Mozart, Bach, or Beethoven. Schubert’s compositions are still being discovered by audiences that appreciate its depth and emotive expression.

I just wish he had known that we would still know his name almost 200 years later. Nearly 200 years after his death, he remains an enigma.

#schubert#franz schubert#quote#music#scruton#roger scruton#composer#musician#austria#austrian#society#piano#symphony#goethe#poem#song#arts#culture#biography

67 notes

·

View notes

Text

𝒯𝒽𝒶𝓃𝒳 𝓂𝓎 𝒷𝑒𝓁𝑜𝓋𝑒𝒹 𝒮𝑜𝓊𝓁: 𝐿𝒶𝒹𝓎 𝒮𝒽𝓎 🇦🇹

𝒲𝒽𝒶𝓉 𝒜 𝒲𝑜𝓃𝒹𝑒𝓇𝒻𝓊𝓁 𝒲𝑜𝓇𝓁𝒹 𝒷𝓎 𝐿𝑜𝓊𝒾𝓈 𝒜𝓇𝓂𝓈𝓉𝓇𝑜𝓃𝑔 🇲🇽

#l o v e#lady shy#x-heesy#iphonography#photographer#1/2024#travelingwithoutmoving#México#heaven is on earth#traveling#female artists#Austrian photographer#🇲🇽#fine photo art#now playing#music and art#contemporaryart#nature#architecture#Mayas#passion#what a wonderful world#oasis#heavenly#history

36 notes

·

View notes

Photo

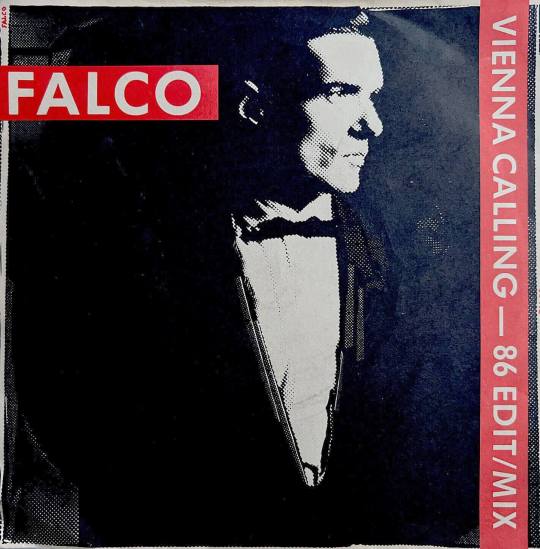

youtube

Falco “Vienna Calling” vinyl sleeve. Listen to the Tourist Version in our video above.

Song facts and lyrics at Simply Eighties

23 notes

·

View notes