#Achaians

Text

I just had a look online to find if anyone had made a list of all the names of fighters in the Iliad, and I discovered that someone in fact had.

I had.

Me.

In 2015.

I have absolutely no memory of this.

I made a spreadsheet, and even wordclouds ffs.

It’s even got what side they’re on, where they’re originally from, their epithet and patronymic if they have one. Wow.

And, you can filter it by any of these to find which version of a character you need.

Oh my god I even put if they brought SHIPS? I made an excel spreadsheet of the CATALOGUE OF SHIPS. (I’m Dyscalculaic though so they might be wrong ha!)

Anyway, thanks, past-fugue-state-me?!

I’m sure I used it to make the Deaths in the Iliad infographic: https://www.tumblr.com/greekmythcomix/722650261704867840/death-in-the-iliad-an-infographic-originally

Anyway, the ‘names in the Iliad’ post is here with links to the spreadsheet: https://greekmythcomix.com/2015/07/21/fighters-in-the-iliad/

Have fun with it!

#Iliad#spreadsheet#greek mythology#greek myth#tagamemnon#homer#greek myth comix#Achaians#Trojans#I work in a fugue state#Achilles#patroclus#achilles and patroclus#research#classics#classical civilisation#ancient literature

906 notes

·

View notes

Text

WAS THE SCENE WHERE THE KENS FIGHT EACH OTHER A REFERENCE TO THE ILIAD OR AM I LOSING MY MIND ????

#barbie#the Kens landing on the shore like the Achaians??#Barbie watching them from the roof like Helen of Troy as they fight over her ??

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ts babe titfucking and masturbating

Blowjob from Indian wife of my Boss

I feel so hot in these ripped fishnet stockings JOI

Enchanting Amanda with great natural tits gets mouth abused

AVN Expo 2020 with Lexi Mansfield

Hot new Ebony Content from Lana Lava on OnlyFans & ManyVids

que rico culo que tiene mi polola

Busty tit fucking milf blows fat cock

Mi novia puta aprendiendo a mamarla

Mature mom fucks teen girl and evil angel sloppy blowjob Hot Family

#jobsearch#Shinnston#Oscarella#FMk#beshrewed#JO#quodlibetically#turboblower#predesertion#taegi#extrapolative#discouragement#outprice#undowered#muscovitized#Dikmen#panatella#Achaian#Hanover#flatteringness

0 notes

Text

"Achilles, prince of Phthia, swiftest of all the Greeks, best of the Achaian warriors at Troy. Beautiful, brilliant, born from the dread nereid Thetis, graceful and deadly as the sea itself."

"Then the best part of him died, and he was even more difficult after that."

"What was his best part?"

"His lover, Patroclus. He didn't like me much, but then the good ones never do. Achilles went mad when he died; nearly mad, anyway."

– excerpts from "Circe" by Madeline Miller

#achilles#patroclus#patrochilles#circe#odysseus#books#book quote#greek retelling#greek mythology#quotes#aristos achaion#animae dīmidium meae

95 notes

·

View notes

Note

do you have a favorite translation of the iliad? i want to read it but want an informed opinion on the best translation to read!!

This is actually a very timely question anon, because I got a new translation of the Iliad for Christmas (Emily Wilson's) and have been enjoying the hell out of it haha so it's on my mind.

In general, I think that the best translation depends on what experience you’re looking for! Homer in Greek is both archaic and formal, and also beautifully dynamic and rapid (like the oral delivery had amazing flow). So translations usually have to kind of pick between the two, and you can lean on whichever side feels best.

This is the Greek of the beginning if you want to read it out loud and get a sense of what two lines of the OG dactylic hexameter are like, and what they’re trying to match:

Mēnin aeide thea pēlēiadeō Akhilēos:

oulomenēn, he muri’ Akhaiois alge’ ethēke

Lattimore (1951) is probably the most ~acccurate~ line-for-line translation, I would use it in place of a dictionary if I was in a hurry sometimes haha it’s that loyal to the Greek if you want to know that that's like, but it's also a bit of a clunky slog to read, lacking poetry:

Sing, goddess, the anger of Peleus’ son Achilleus

and its devastation, which put pains thousandfold upon the Achaians,

Wilson (2023) that I just began today so far has been fresh and engaging, it begins like this:

Goddess, sing of the cataclysmic wrath

of great Achilles, son of Peleus,

which caused the Greeks immeasurable pain

Fagles (1990) has good flow without sacrificing too much accuracy. It was the first translation I read, and look what happened to me lmao. It starts like this:

Rage—Goddess, sing the rage of Peleus’ son Achilles,

murderous, doomed, that cost the Achaeans countless losses,

Fitzgerald (1974) is another popular choice, he has good poetic feel:

Anger be now your song, immortal one,

Akhilleus’ anger, doomed and ruinous,

Or if you want to feel like Keats, you can go hog wild and hit up some Chapman from the 1600′s:

Achilles’ banefull wrath resound, O Goddesse, that imposd

Infinite sorrowes on the Greekes, and many brave soules losd

Basically there's no real right answer, but if you came over to my house and asked to borrow a copy, I would hand you Fagles (1990) (pdf here if you want it).

#classics#hopefully useful answer haha#enjoy!!! nothing better than drinking from the ever-fresh source of western lit

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

I love that scene in Book 5 of the Iliad where Hera is like „Zeus, look at that lawless savage Ares, giving trouble to my precious Achaians! Aren't you angry at his mindless violence? Would you mind if I went down there, kicked his ass and made him run away from the battlefield?” and Zeus is like „Sure, whatever, but better have Athena kick his ass instead. You know she is the ultimate expert in that.”

Really funny that one of the few things they can agree on is that their son sucks.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

I.

Some general points when it comes to ancient Greek culture and certain attitudes relevant to the topic:

-both men and women were supposed to show self-restraint when it came to sex; it was a virtue, and furthermore, self-restraint and moderation (in all things, but especially this) was part of what made a man "manly", if you will. Women being modest and chaste were similar for them, and an extra step further than a man's "moderation".

-At the same time, women were considered "naturally" more sexual, and having less self-control (that was why it was extra important they exercise self-restraint and being chaste), which leads into the connected idea that a man who does not… becomes feminized.

(Something illustrated by Lucian of Samosata's A True Story, in the very first parts of it, and talked about below:)

For the Iliad specifically, Christopher Ransom in his Aspects of Effeminacy and Masculinity in the Iliad (2011) summarises up a couple other points:

"In the Iliad, childishness and effeminacy are often referred to in order to define masculine identity. Women and children are naturally not operative in the adult male world of warfare, and so can be clearly classified as ‘other’ within the martial sphere of battlefield insults. Masculine identity cannot be formed in a vacuum, and so the feminine or the childish is posited as ‘other’ in order to define the masculine by contrast."

and "Idle talk is characterised as childish or feminine, and is repeatedly juxtaposed with the masculine sphere of action."

as well as "Effeminacy is linked to shame […]; if acting like a coward is a cause for shame, and prompts Menelaos to call the Achaians ‘women’, then effeminacy is seen as shameful in the context of the poem."

And while neither dancing nor sex are something that a man who engages in will become effeminate for, the former is explicitly posited as a peace-time pastime only, and sex is only to be had at the right time (and in the right amount). So, in the Iliad's (as well as the whole war) circumstances, neither of those two activities are proper to prioritise, and are at points set up in juxtaposition and contrast to war and martial effort.

Additionally, physical beauty alone doesn't make a man in any way feminized - otherwise quite a few male characters would be effeminate! - and in fact, a well-born, "heroic" man will be beautiful because it befits his status. (Insert basically any big-name male character in Greek mythology here.) But, there's a limit and some caveats to this; physical beauty in a man (not a youth) must be balanced out against other "virtues", and if, in especially the context of war as in the Iliad, a man's martial ability is lacking, his handsomeness becomes a source of scorn instead, because he can't "back it up".

Here's our most notable "offenders":

Nireus of Syme, who in the second book of the Iliad is called the most beautiful among the Achaeans after Achilles, but "he was weak, and few men followed him". Syme is a small island, but I don't think the "few men" here is supposed to be assumed because of a lack of numbers on the island. His beauty is all there is to him, and no one wants to follow him because he's not sufficiently (manly) able in war.

Nastes and/or Amphimachus of Miletus, wearing gold in his hair "like a girl", which the narrator then calls him a fool for and that he will be stripped of those pieces of jewellery when Achilles kills him, and, again from Ransom's article; "Thus, the effeminised male, characterised by his feminine dress, is brought down by the ‘proper hero’, and the effeminate symbolically succumbs to the masculine."

Euphorbos, the man who first injures Patroklos - this is an edge-case, because the text itself isn't obviously condescending or condemning Euphorbos compared to Nastes/Amphimachus. It simply describes him wearing his hair in a style of hair ornaments that pinches tresses in at the middle. But, the narrator still goes to the effort to make this extra description, not just the more general/usual mention of the hair being befouled in the dust as the man killed falls to the ground.

(In the intent of being somewhat exhaustive, two other potential edge-cases:

Patroklos, who does perform some tasks at the embassy dinner in Book 9 that would usually be done by women. And it's not as if Achilles doesn't have women who could deal with the bread and similar. It's not remarked on, or marked in the text in any way, compared to the other characters previous.

Menelaos, even more of an edge case, but like Patroklos he's described as gentle, and by Agamemnon and Nestor's indictment doesn't act when he should, being more prone and willing to let Agamemnon take point. Could say it ties into how Helen in the Odyssey is the more dominant partner in terms of social interaction, as well.)

And then there's our last "offender", who we see more of in terms of his lacking in living up to proper (Iliadic) masculinity; Paris. Before going into that, though, I want to touch on something else.

II.

That being what the idea of the Trojans being "barbarians" does to the Trojans in later sources. In the Iliad itself, while the Iliad does have a pro-Achaean bias, the Trojans and their allies aren't really portrayed in the same way as happens later (but not consistently so), coming into shape during and after the Persian Wars. In summary, it's during this time the Trojans gain the negative stereotypes of the eastern "barbarian"; luxurious, slavish (but also tyrants! one basically ties into and enables the other), and effeminate.

Not all "barbarians" were considered the same, with the same stereotypes attached to them; northern (Scythians, etc.) barbarians were considered violent and warlike, "savage" if you will.

Edith Hall's book Inventing the Barbarian (1989), is all about this, but have a couple hopefully illuminating quotes about how these stereotypes were expressed, especially in drama/fiction:

So what happens is that all Trojans get tarred with this barbarism brush, as illustrated in the Aeneid (by a character, not the narrative); "And now that Paris, with his eunuch crew, beneath his chin and fragrant, oozy hair ties the soft Lydian bonnet, boasting well his stolen prize."

Notes here: 1. This is said by a character, not the narrative itself, and someone using this as an argument against Aeneas and his Trojans, but the stereotype itself isn't something new; 2. "That Paris" = Aeneas. While this might be more about Paris as a seducer and abductor of Helen, given the emasculation of the rest of the Trojans and then the additional effeminate touches with Aeneas' supposed dress and hair, I'd say it's not just about that; 3. The word translated here as "eunuch" (semivir, "half-man"), by a quick look in Perseus' word tool, is also straight up used about effeminacy, though of course a eunuch wasn't a "full"/proper man and often viewed as effeminate, too, so they're tied together.

Even with this development, in looking at the Iliad itself obviously not all Trojan characters would be equally easy to cast in an effeminate light. Again, we come back to the easiest target, the one who, by the way he's juxtaposed against another character who exemplifies the "war as (part of the) male gender performance" in the Iliad, stands outside of that. The one who basically, as he is portrayed in the Iliad, by the stereotype of the eastern barbarian becomes the archetypal "eastern barbarian Trojan".

Paris.

III.

So, let's talk about Paris!

At the very basic level when it comes to Paris and his place in the Iliad, is that he is the foil and contrast to his brother Hektor in specific, as a warrior and as a man. But in that specific reflection he is also the contrast against every other male character, Achaean and Trojan, in the Iliad.

What does this mean?

-Cowardice; he's slack and unwilling as Hektor accuses him of. No way to know if this is specifically because he's always afraid, as in the moment we see before his duel against Menelaos, since being unwilling to fight in deadly combat could be for many different reasons. (He is not always slack and unwilling, however; he is out there on the battlefield with the rest at the beginning of Book 3, and after Book 6 he is, as far as we know, out there with the rest of the Trojans, from beginning to end. His unreliability in his martial efforts is another angle.)

-He is one of, if not the worst, fighters among the commanders, on both sides. His martial prowess isn't up to snuff and as we see in Book 3 where Hektor calls him out on retreating, he notes that Paris' beauty would have the Achaeans believe Paris is one of the Trojans' foremost champions. But he's not, both because of his cowardice and his lack of martial ability, and tying into this, then, is;

-Paris' beauty. As noted earlier with Nireus, physical beauty not backed up by martial prowess makes you less than, and the epithet used for Paris to call him godlike is specifically about his physical looks. There are other epithets (also sometimes used of Paris) that mean "godlike" in a more general way, but the one most often used of Paris is specific. And, that particular word is what's used when Paris first leaps forward in Book 3; the narrative is using theoeides every single time Paris' name is used in that scene, and so we get something like this, from J. Griffin in his Homer on Life and Death (1980): "…the poet makes it very clear that the beauty of Paris is what characterizes him, and is at variance with his lack of heroism…" as well as from Ransom in his article: "Again the suggestion is that Paris’ beauty is empty, and that he is lacking the courage or other manly characteristics that would render it honourable. […] Paris is set against Menelaos, a ‘real’ man by implication, and he is told that his skill with the lyre and his beauty would be no help to him then."

-His pretty hair gets insulted at least once (by Hektor) and potentially twice, the second time by Diomedes in Book 11 (the phrase used is uncertain whether it's about Paris' hair or his bow; that it could be his hair, being worn in a particular style, has been an idea from ancient times). And we know what sort of fuss the Iliad makes of pretty hair in men who do not otherwise live up to being properly masculine according to its ethos.

-Being an archer. The bow wasn't the manliest weapon around, and the Iliad disparages its use on the battlefield (selectively!). Paris is basically our archetypical archer, who gets insulted for being an archer and less manly because of that.

-His focus on dancing and music, as brought up by both Hektor and Aphrodite (and, though in a more general insulting context with other sons being mentioned as well, by Priam). The problem is, again, of course not his skill or interest in and with these things, but that he is better at these than combat and that he shows more interest in them and probably puts more effort in when it comes to them, too.

-His sexuality. As noted earlier, a man should show moderation and self-restraint. Paris, giving in to his desires and having sex in the middle of the day and during a tense moment, even if the forces aren't supposed to be fighting at that very point in time (neither he nor Helen would know Athena has induced Pandaros into breaking the truce), is certainly not showing any sort of moderation. I can't emphasize enough how much this isn't some epitome of macho male sexuality and prowess. Rather, this is the epitome of feminized weakness to sex, and Paris throws himself whole-heartedly into it.

-Paris' physical presentation. There is a lot of focus on his dress and how it makes him look (Aphrodite practically objectifies him for Helen's pleasure when she describes him to her!), and that his clothes are gorgeus. Again, have a quote from Ransom about that Aphrodite-Helen scene: "This scene captures his essence perfectly. Once more Paris’ looks and dress are emphasised […] and, in Aphrodite’s speech, the poet explicitly disassociates him from his martial endeavour." Connected to this we have his first appearance earlier in this book, where he's described as not wearing full armour but a leopard pelt. Here's Griffin again: "[…] so he has to change into proper armour before he can fight - and we are to supply the reason: because he looked glamorous in it."

Now, I don't think it's that simple, because other people wear animal pelts in the Iliad; Agamemnon and Menelaos both do so, as does Diomedes and Dolon. However, Agamemnon and Menelaos both wear theirs as part of a full martial dress and they're clearly meant as part of a display of authority and martial prowess and Diomedes, though he's not otherwise fully armoured as this is part of his dress during the meeting before the night raid, is clearly meant to be similarly glorified (Dolon is more of a question, considering how he's portrayed otherwise). Paris is specifically not wearing a full set of armour, even if he apparently has it at home, so in the end I'd agree with Griffin that, given the other instances of Paris' clothing being extravagant/beautiful, this is indeed an instance of "because he looked glamorous in it".

But as Ruby Blondell puts it: "The destructive power of "feminine" beauty is most ostentatiously displayed, among mortals, in the person not of Helen but of Paris. In contrast to the veiling of her looks, Paris's dangerous beauty is displayed, glorified, and also castigated. […] His appearance is unusually decorative, even in battle. His equipment is "most beautiful" (6.321), glorious, and elaborate (6.504), and his outfit includes such exotic details as a leopard skin (3.17) and a "richly decorated strap (polukestos himas) under his tender throat" (3.371)." (Helen of Troy (2013))

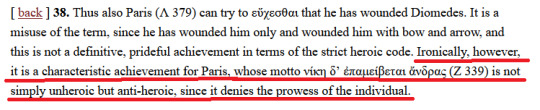

-His attitude towards the whole (Homeric) heroic ethos of the Iliad. Not just his unwillingness or lack of martial prowess, but rather the "personal motto" he expresses to Hektor in Book 6; "victory shifts from man to man". And, while I wouldn't say this is at all a typical mark of an effeminate man in terms of the Ancient Greek outlook on these matters, you do have to set it in connection to his other martial "failings". As Kirk in his The Iliad, a Commentary, vol. 1 (1985/2001) says: "He thus attributes success in battle to more or less random factors, discounting his personal responsibility and performance." and, another point of view from Muellner in The meaning of Homeric εὔχομαι through its formulas (1976) about this same "motto":

-As a brief little point, when it comes to his being a lyrist; that, too, was often edged in ideas of effeminacy, so while, of course, no man is effeminate just because they may take up the lyre at some point, if you dedicate your life to it, that starts to have an effect on how you're viewed.

So what you have, then, in sum is Paris being very much non-masculine - or at least not conforming to the martial and cultural expectations and mores of the Iliad's/the Homeric masculine ethos. Even if you add in/change some of how the Trojans might view things, Paris would without a doubt still be non-conforming. Myth-wise, he certainly is so, both before and after the Persian Wars and the changes to the Trojans' general perception at the hands of the Athenian tragedians happened.

Here's Christopher Ransom again, to tie things up: "If gender is performance, Paris is simply not playing his part; if ‘being a man’ requires a concerted effort and a conscious choice, it seems as though Paris’ choices are in opposition to those of his more heroic brother."

IV.

And lastly, some scattered quotes from ancient sources about Paris, roughly ordered from earliest to latest:

"No! my son was exceedingly handsome, and when you saw him your mind straight became your Aphrodite; for every folly that men commit, they lay upon this goddess, [990] and rightly does her name begin the word for “senselessness”; so when you caught sight of him in gorgeous foreign clothes, ablaze with gold, your senses utterly forsook you." (Euripides, Trojan Women)

-This one is pretty straightforward, especially keeping in mind all the above and Edith Hall's discussion of the words connected to eastern "barbarians" by this point.

"Vainly shall you; in Venus' favour strong,

Your tresses comb, and for your dames divide

On peaceful lyre the several parts of song;

Vainly in chamber hide

From spears and Gnossian arrows, barb'd with fate,

And battle's din, and Ajax in the chase

Unconquer'd; those adulterous locks, though late,

Shall gory dust deface." (Horace, Odes)

-Double focus on his hair, and through that, Paris' behaviour, all of it disassociating him from martial effort and into a more "feminine" sphere.

"[…]shall we endure a Phrygian eunuch hovering about the coasts and harbours of Argos […]" (Statius, Achilleid)

-Again, the "eunuch" here is "semivir", so Paris is explicitly emasculated and made out to be effeminate.

"And he washed him in the snowy river and went his way, stepping with careful steps, lest his lovely feet should be defiled of the dust; lest, if he hastened more quickly, the winds should blow heavily on his helmet and stir up the locks of his hair." and

"he[Paris] stood, glorying in his marvellous graces. Not so fair was the lovely son whom Thyone bare to Zeus: forgive me, Dionysus! even if thou art of the seed of Zeus, he, too, was fair as his face was beautiful." (Colluthus, Rape of Helen)

-I don't think I need to say much about that dainty description of Paris' behaviour and the care he takes to still look as put together and beautiful for when he reaches Sparta, do I?

The second quote, though, I think deserves some comment, because Collutus twice in short order compares Paris to Dionysos, and as we saw in Hall's book, Dionysus in the Bacchae is associated not just with a foreign man, but someone who would be tarred with the stereotypes of the eastern "barbarian". And Dionysos has long, of course, been portrayed with a particularly feminized beauty, not just in drama.

On top of this, much earlier than Colluthus we have Cratinus' Dionysalexandros, a satyr play where Dionysos takes Paris' place for both the Judgement and kidnapping Helen. To note is that while the satyrs are followers of Dionysos, their uses as chorus in satyr plays wouldn't necessarily have them attached to Dionysos (often, they seem in fact to have removed themselves from him). And in this circumstance, then, Paris isn't just compared to the effeminate Dionysos, Dionysos straight up (though disguised as Paris) replaces him for a part of the play.

It all starts in the Iliad, but it certainly doesn't end there, and by the end Paris' effeminacy is just all the more explicitly stated in text as effeminacy.

(While the other sources mentioned here would either have to be bought or found… in other ways /cough, Christopher Ransom's article can be read right here: https://www.academia.edu/355314/Aspects_of_Effeminacy_and_Masculinity_in_the_Iliad )

29 notes

·

View notes

Note

Since you have an interest in ancient texts... Have you thought about, in the future, making an IF that takes place on the past or, otherwise, involves an archeologist MC/RO's? Or maybe an IF inspired by an old text (for some reason I immediately thought about the Illiad, when the Odyssey is a significantly better option for an IF 💀). Also, how ancient are we talking about? Like, if I take sir Thomas Malory as an example, is he too modern for you? What about Chaucer? Like, should I go before the Middle Ages?

Revealing more about my mysterious self. Now I’m a big reader, huge and I’ve read modern, early modern and pre-modern English works but only for fun, my interests lie in primarily Roman (republic, imperial) works, and Greek with some dabbling into Mesopotamia with the epic of Gilgamesh and the general Middle East with 1001 nights. So yeah give my the Historia Augusta any day

You know I go between which of the two is my fave, for a long time the odyssey was my favourite but I’ve been looking at the Iliad again and it’s too good, I feel like an IF could be made of it, if we also gather sources from the odyssey to what happens when the Achaians breach Troy

As to your question, yeah I’ve thought constantly about making an IF set in the distant past. Something kind of like what happened to Carthage by the Romans or influenced by the rise of Augustus to emperor

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some thought about the Iliad:

- I love how I haven’t seen Achilles in four books and they’re constantly like “this guy was the strongest/best one IF YOU FORGET ABOUT ACHILLES” or “oh and yeah Achilles is still being a little bitch alone on his boat

- agamemnon calling the Greek “achaians with good shinplates” is so funny to me cause it’s like yeah we protect our feet unlike some of us with certain fatal flaws concerning our feet hmmmmm

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

First lines

Tagged by the wonderful @aeide, who included first lines for both their published fics and their unposted WIPs. Y’all would be scrolling for years if I did both bc I have too many fics and WIPs so I’m just going to do the unpublished fics that I’ve worked on the last three months - and you’re still going to be scrolling a lot 😬 I’m sorry!

In the Shadow of Zeus: Kassandra’s years on Kephallonia, as seen from multiple perspectives. This probably won’t end up being the first chapter but the second, but it’s the first chronological snippet I have written.

“Alright, rub a little bit of dirt on your face,” Markos says as their first target comes into sight, “Not too much, just enough to make your tears more obvious. You sure you can cry on command?”

As she has the last two times he’s asked, Kassandra rolls her eyes at him and starts to rub some dust on her cheeks with a surprising lack of complaining for a girl who grew up in relative luxury. Or so he’s assuming, judging from the little he’s been able to figure out about his new ward, as she refuses to talk about anything that led to her washing up on that beach.

But with her Peloponnesian accent and that broken spear that barely leaves her side, he thinks it’s fair to say she’s got Spartan blood in her. Her family had money or power or both too, saying she can read and write better than he can. And for all that she’s only seven, she has some semblance of manners and grace that he’s only seen in the wealthy Achaians he used to serve before he bought his freedom.

If he had to guess, her father was a decently high ranking Spartan officer stationed in Achaia or Elis. Maybe even as far south as Arkadia, depending on how far north that storm managed to take her. And judging from the nightmares Kassandra has had every night for the last ten days, he’s dead, along with her mother and her brother.

Worse, he’s pretty sure Kassandra watched them die.

A Flap of an Eagle’s Wings: my second Odyssey time travel fix it, bc I have a problem, except in this one Kassandra comes back earlier, saves Alexios, and then fucks up the canon timeline with the help of a couple others who came back with her 😳

In the ruins of Atlantis, Kassandra closes her eyes and finally, finally, falls into the long awaited, welcome embrace of Death.

“Earth, mother of all, I greet you.”

There is a crack of thunder that shakes the earth and a strange pressure on her wrist as her body becomes weightless. Thanatos, perhaps, personally escorting her to face the wrath of the King of the Underworld.

She is not afraid though. She had been young and brash and foolish when she last faced Hades and still she had held him at her mercy and stolen his crown as a final insult before Poseidon whisked her away to Atlantis. And she is far more powerful now.

Then there is another rolling crack of thunder, the world goes white behind her closed eyes, and a bond that has been broken for almost two thousand years snaps back into place as she is thrown from Mount Taygetos a second time.

She opens Ikaros’ eyes to see the horror in Nikolaos’, the way he lurches forward as if to try and catch her and the way his face fills with grief when his hand grabs nothing but air. She watches her mother scream her name and nearly throw herself off the mountain after her, only to be stopped by Nikolaos and the other Spartans.

The last thing she sees before Ikaros forces her back to herself is the fury in Myrrine’s eyes as she steals her husband’s sword from his waist and lunges for his throat.

Untitled Alkibiades Time Loop fic: this idea came to me in like a fever dream or something and basically Alkibiades is stuck in a time loop of the day Phoibe and Perikles die trying to save them both. I have about 40/50 at least vaguely planned out and this is loop 7 as of now, the earliest chronologically written.

“Allie,” Kassandra sighs, her brows unfurrowing as she leans back onto the kline. She’s not much older than him to begin with, but she looks even younger as her brows unfurl. Softer. “You know I love you, but I barely have the time to sit right now, let alone - ”

“Phoibe and Perikles will die today.”

Confusion. Grief. Confusion again. Suspicion. He watches Kassandra’s face cycle through a thousand emotions in a second, before she settles on unfathomable rage. Quicker than he can blink, her spear is in her hand and her eyes are full of fire and it’s impossible not to see why so many call her a demigod.

“Start explaining. Now.”

Begin, Muse, When the Two First Broke and Clashed: Deimos’ thoughts, maybe chapter two will be Kassandra’s, at the Battle of Pylos. Aka a small snippet that I just haven’t been able to finish yet for some reason

Sparta has no walls. Sparta has no walls.

According to Pausanias’ foolish boasts, Sparta has no need of walls to protect her people as Athens does. Sparta’s walls are her people, every man from twenty to sixty, born and bred to die defending Lakonia from invaders.

They should build a fucking wall.

Deimos will admit that the Spartans are better trained than the Athenians that fight under his command, but to compare the two is to compare a rat to a mouse. A rat will fight for its life more viciously than a mouse will, a rat will bite harder to try and escape than a mouse will, and a rat will die just as easily as a mouse will.

These Spartans fall to him just as easily as every other man he’s ever faced.

Perhaps his so-called sister will prove to be more of a challenge for him. Otykos trained him the moment he could hold a sword in his hand and she killed him. The Monger had been a monster of a man and she had killed him. Deianeira and her cousin had been deadly for mere mortals and she had killed them. And she tears through his men as easily as he tears through the Spartans. He’d almost find it impressive, but . . . Rats and mice.

Untitled Depressing one shot: inspired by a comment on my HPxOdyssey crossover, this fic is about Barnabas and Herodotos trying to figure out what happened to Kassandra when she doesn’t come back from Atlantis.

They wait three days before they begin to worry.

Kassandra had told them she didn’t know how long her adventure in Atlantis would take when she left them. Aletheia hadn’t been very forthcoming on the details, she had complained, but she had promised them she’d be back soon as she hugged them goodbye. And since soon can mean anything from a few minutes to a few days when Kassandra says she'll be back soon, they had tried not to worry until the third day.

Herodotos finally drags him away when he tries to claw open those cursed doors to Atlantis with his bare hands, tearing his fingers to bloody shreds after he breaks half the swords and javelins on the Adrestia trying to pry those fucking doors open.

Cage the Songbird: a little inspired by the Elton John song of the same name, this is the fic I write when I’m in the middle of a depressive episode, about the last few months before Elpidios’ birth. Featuring a fling gone wrong, one sided Kassandra/Natakas, past Kassandra/Brasidas, Alexios and Kassandra learning how to be siblings without wanting to kill each other, and Barnabas and Herodotos being the best dads.

Natakas wakes up in the bed he made for two, alone, as he has every day for months now. It still hurts.

His father is awake already, sharpening his blade and occasionally stirring a pot of something meaty. He greets him with a warm smile, “Good morning, Natakas. Did you sleep well?”

“Yes, father. Is Kassandra up yet?”

Darius’ smile falls a little as he jerks his head up towards the roof. Kassandra has a hammock tucked away in a small corner in their home, but most nights she sleeps on the roof, on a thick mattress her captain brought her a month ago.

Natakas hates that mattress. He hates that it’s only big enough for her, he hates that it’s softer than the bed he made for the both of them to share, and he hates that when Barnabas brought it, the old man once again tried to convince her to go back to Sparta.

Untitled Alternate POVs: Because the Children of Kephallonia is written entirely from Kassandra’s perspective, something I’m not used to doing, I’m also rewriting parts of the fic from other POVs to help me better figure out the plot, characters, relationships, etc. Just for me right now, but I’ll probably post it on AO3 or my hypothetical patreon someday.

Brasidas has been sitting and half watching the Monger’s warehouse for the last hour or so. Just watching, unfortunately, because as much as he would like to rescue the captives held behind smuggled goods, he is only one man.

Hopefully, he’ll have collected enough information on the guards and their daily routines to bring five or so of his men and raid the warehouse within the week. He can’t afford to let the Monger run wild much longer.

He makes a note that the guard at the dock closest to him switches with a guard at the warehouse door and scrapes the last bit of food from his plate. When he looks back up, the guard at the dock is gone.

Strange.

For a moment, Brasidas wonders if the dock guard just walked a little further down he thought, but then he sees movement at the far end of the dock, a little bit east from where the first guard vanished. Someone comes out of the water and pulls a guard down in the span of seconds, before both disappear entirely.

Indiana Jones and the Staff of Hermes Trismegistus: aka I watched Indiana Jones 5 and have only one braincell and it’s dedicated to loving Kassandra. Also, I wanted to write her killing Nazis 🤷♀️

Immortality.

He’s not surprised that’s what the Nazis are after, again. What does surprise him is that they’re not going after something from Judeo-Christian tradition, again. But after their quests for the Ark of the Covenant, the Lance of Longinus, and the Holy Grail all ended with a bunch of dead Nazis and an increasingly enraged fuhrer, perhaps he shouldn’t be so surprised that they’ve decided to look for something even more ancient.

But the Staff of Hermes Trismegistus? Or all the myths to sink their hopes in, they’ve chosen one that the world knows nothing about?

As always, I’m tagging @auroralykos and @aetosavros and anyone else who wants to do this!

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

Achilles propaganda: His place in the story is to beget violence. His sitting out of the war allows for the continuation of more senseless death on both sides, and his battle frenzy and rage is his defining moment. I think he is very Slaughter because he is the perfect weapon for violence, and no matter what he does thats what he sows. His vengeance doesn't satisfy him; he continues to kill and defile and has to be taken out by the hand of the gods because he is the perfect killing machine.

"Sing, O Muse, the wrath of Achilles Peleus' son, the ruinous wrath that brought on the Achaians woes innumerable, and hurled down into Hades many strong souls of heroes, and gave their bodies to be a prey to dogs and all winged fowls; and so the counsel of Zeus wrought out its accomplishment from the day when first strife parted Atreides king of men and noble Achilles."

Achilles! Best of the Greeks!

.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

"There is, it is generally agreed, nothing in the [Iliad] that corresponds to a contemporary notion of rights as abstract principles. Rather, the closest Homeric term to rights is themis, which is understood as orally transmitted custom or tradition that is applied to particular, concrete cases...

Though themis is associated with a cosmic order, themis is not a statement of divine right, nor is it simply the prerogative of the king, as Benveniste (1973.382) suggests, as well. Rather, we see evidence of themis as extending into a set of political relationships within the community. Nestor will provide an important statement of the reciprocal set of obligations between the king and the people (laos) when he says to Agamemnon that 'Zeus has given into your hand / the sceptre and right of judgment (themistas), to be king over the people. / It is yours therefore to speak a word, yours also to listen, / and grant the right to another also, when his spirit stirs him / to speak for our good (agathon). All shall be yours when you lead (archêi) the way' (9.98-102).

In this case, leadership is based not simply on the power to command (kratos), as Agamemnon seems to suggest, but on the creation of a political space in which others may speak for the good of the community. It is a right that Diomedes, too, seems to regularize, as he phrases his sentence with an unconditional 'is': 'as is my right, lord, in this assembly' (hê themis estin, anax, agorêi) (9.33). There appear other explicit associations of themis to the assembly of the people. Patroklos, for example, is depicted as running toward the ships 'where the Achaians had their assembly (agorê) and dealt out themis' (II. 11.806-7). We see portrayed an unhealthy politics, as well, as Zeus is portrayed as punishing those who 'in violent assembly (agorêi) ... pass themistas that are crooked' (II. 16.387)."...

[Therefore,] more than just raising an individual grievance, Achilles, as we have seen, opens up the customary basis of Agamemnon's authority, namely, that of wealth and inheritance. It is a claim to kingship made by Agamemnon, and supported by Nestor. And it is an attack on the very foundation of the king's power, as Agamemnon recognizes immediately.

What comes out of this confrontation is a challenge to the notion of themis as a king's prerogative but what emerges, ultimately, is a notion of themis that is tied more explicitly to a set of relationships within a public space. For Agamemnon, in this opening dispute, themis is inseparable from one's might. So Agamemnon tells Achilles that he will take Briseis so 'that you may learn well / how much greater I am than you, and another man may shrink back / from likening himself to me and contending against me' (1.185-7). The consequence of this notion of themis is that the king is never able to separate his private desires from public claims to the distribution of resources. So, in responding to Achilles, Agamemnon claims that the Achaians must either give him a 'new prize / chosen according to my desire' or 'if they will not give me one I myself shall take her, / your own prize, or that of [Ajax], or that of Odysseus' (II. 1.135-8).

We see in the funeral games a departure from this notion of distribution as an act of largesse. Achilles sets the context for this transformation by making the question of themis a public one. By doing this, the question of distribution, contrary to the suggestions of Finley (1979.80-1, 110) and Edmunds (1989.28), is an issue of 'political justice.' And to that extent, disputes about distribution are taken before the community — whether in the active role of counselors (as in the shield) or leaders (23.573) or in the role of observation as one swears to Zeus before the whole people."

- Dean Hammer, from "The Politics of the 'Iliad.'" The Classical Journal, vol. 94, no. 1, 1998, pp. 1–30. JSTOR.

#dean hammer#homer#quote#quotations#the iliad#politics#rights#community#relationships#democracy#agamemnon#achilles#authority#leadership#justice

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

30 days of devotion: Nymphai

Day 4: A favourite myth or myths of this deity

There are uncountable myths that concern the nymphs, and picking my favourite among them feels impossible. There’s the chase of Daphne, of course, the story of Echo, and arguably in some cases, Kirke. I do think one nymph stands out to me, and I’ll talk of her down below. TW: Mentions of abduction/allusions to r//pe.

Thetis, (unwilling) wife of Peleus and mother of Achilles. She was a nereid, daughter of Nereus, 'the old man of the sea.'

A reason why I gravitate towards her (other than for the fact that my wife worships her) are several things; 1) she’s mentioned in the oldest piece of western literature and my favourite epic poem, 2) her unwavering love for Achilles and 3) her grief at his fate and her loss of him. Nymphs frequently beget heroes in mythology, but they often do not (have to) fulfil the other societal pressures and expectations put on mortal women in their roles as wife and mother. They are seen to take care of infants - but they are usually not their own. Thetis is an exception. She is a mother, not just a progenitor. Another reason she stands out to me, is illustrated in this quote below,

���In the Iliad, such encounters [of nymph and mortal man] happen only to the Trojans and their allies and are absent from the genealogies given for the Achaians [Greeks]. Apparently, the motif of the mortal herdsman who is loved by a local nymph was at first confined to Asia Minor; Griffin suggests it is in origin a variation of the union of the Great Goddess with a mortal consort. Unions between nymphs and mortals, however, were not unknown to the Achaians, for Achilles was born of Peleus and the unwilling Nereid, Thetis.” - Greek nymphs, Myth, Cult, Lore by Jennifer Larson

Why is Thetis the exception to the rule? I have no idea. I’m fascinated by her.

Another reason why I love her, especially in the Iliad, is the distinction in relationships between mortals and gods, and mortals and nymphs. The nymphs in hymns and poetry were called “my dear nymphs”, standing much closer to mortals than the distant Olympian gods did. You do not see (there are exceptions, for example the goddess Aphrodite) where they are talked of lovingly and intimately. Here is a quote of the Iliad, in which Achilles talks of Thetis,

“Mother tells me, the immortal goddess Thetis with her glistening feet, the two fates bear me on to the day of death.”

Besides the inherent tragedy of Thetis having to tell Achilles his fate; he calls her by the familial title of mother, first. I don’t have a scholarly reason for liking this so much. It just makes my heart soft.

Thirdly, I also respect her for her willingness to fight a fate she did not want for herself. Gods and mortals alike cannot change “the will of Zeus” (fate), but she did give it her best shot when,

“Out of all the sea goddesses, he [Zeus] subjected me to a man, Aiakos’ son Peleus, and I endured the bed of a mortal man, though I was completely unwilling.” (Iliad, Homer)

She changed into varying (terrifying) shapes to loosen his hold on her, and eventually gave up, though not for lack of trying. She fits into one of the most common motifs in later myths throughout Europe of the ‘swan maiden’ here, where a man captures a bird maiden by stealing her coat of feathers while he watches her bathe. She struggles, fails to break free, and silently fulfils the duty of mother and wife, until she eventually regains possession of the coat and disappears, usually still periodically checking up on her children after. In Thetis’ case, she was a nereid, changing into sea animals. This fascinates me, because besides her being a mother of an Achaian hero, here too she is the exception, being one of only two figures* in ancient Greek mythology who bear a similar fate of forced marriage with a mortal man by holding her down as she struggles and then gives in (while later in folkloric tales about neraïdes, it is a much more common motif)**.

And lastly, a reason already listed above for adoring the myth of Thetis, is that when she couldn’t sway the end the Fates had in store for her son, Achilles, she tried to immortalise him in fire anyway (talked of in the Argonautica, by Apollonius of Rhodes). She failed, as none could sway the will of the Fates, but she attempted it anyway, just as much as she fought against Peleus’ grip.

She tried making Achilles immortal by placing him in the fire during the night (Achilles was a child, and Thetis still lived as Peleus’ wife with him) and anointed him with ambrosia during the day. The attempt fails when Peleus happens to see his son’s immersion in the flames, and gives out a terrible cry, whereupon Thetis throws the boy down, goes away herself, and does not return. Peleus was bound to find her and stop the process of immortalisation, as Achilles wasn’t destined to become a god. She tried her best, though. I have to give her that.

*The other example is of Aiakos, Peleus' father, funnily enough, with another nereid called Psamathe. Psamanthe, whose name means "sea sand," had turned into a seal to escape his grasp (and failed). She had a son called Phokos, "seal."

**There are several reasons why this was less common in ancient Greece (for example, people finding it repugnant that a deity, any deity, was subservient to a mortal, unless it be by the will of Zeus, or by the influence of European fairy-capture stories).

Extra note: my favourite art of Thetis can be found here.

Sources used: Greek Nymphs, Myth, Cult, Lore, by Jennifer Larson, The Iliad by Homer, Pindar, and the Argonautica by Apollonius of Rhodes.

#thetis#thetis worship#the nymphs#nymphai#nymph cults#helpol#hellenic reconstructionism#hellenic polytheism#30 days of devotion

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

O beautiful and kindly divinities, be gracious, powerful ones,

whether you are counted among the goddesses of heaven or of the

Underworld, or are called shepherd nymphs. Come, nymphs, sacred

offspring of Ocean, in answer to our need show yourselves clearly

to us, goddesses, and reveal some source of water in a rock or some

holy spring bubbling up from the earth, with which we may douse

the ceaseless fire of our thirst. If ever we sail back safe to the Achaian

land, then among the foremost goddesses we shall offer you in

gratitude countless gifts of libations and feasts.

(Apollonius of Rhodes, Jason and the Golden Fleece (Argonautica), 4.1411-1420).

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Homer's Hera is sooooooo jealous and that's why, when Zeus lists several women he's slept and had children with just before he and Hera have sex, her reaction is to take issue with the idea of having sex outdoors where anyone could see them and to ssuggest that they should go home in order to sleep together in private.

I feel like people, including scholars sometimes, approach the Iliad with the established belief that Hera is just so very jealous, so they interpret everything she does based on that preconception. How else can one get to claim sexual jealousy as the reason Hera is upset with the discussion of Zeus and Thetis in Iliad I when there isn't any indication of him having a sexual interest in Thetis in the poem and, more importantly, when Hera makes it clear what her problem is, namely that Zeus does not consult her when he makes decisions and that his promise to Thetis spells out trouble for the Achaians?

Hell, I once read the claim that Homer must not have known of Zeus' union with Themis, otherwise there is no way that Hera would have been so civil to her as she is in the Iliad. It is fucking ridiculous.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

“And now Aineias, lord of men, would have perished there, if Zeus' daughter Aphrodite had not quickly seen it, his mother, who had conceived him to Anchises, when he was herding cattle. She threw her white arms round her dear son, and held the fold of her shining robe in covering over him, to shield him from the spears, so that no fast-horsed Danaan should cast a bronze spear in his chest and take the life from him. She then began to carry her dear son out of the fighting. And Kapaneus' son did not forget the instructions given him by Diomedes, master of the war-cry, but held back his own strong-footed horses away from the roar of battle, tying their reins to the chariot rail, and ran out and drove Aineias' lovely-maned horses away from the Trojans back to the well-greaved Achaians, andgave them to Deipylos to drive to the hollow ships his dear friend, whom he valued most of all men of his own age, because their minds thought alike. Then the hero Sthenelos mounted his own chariot and took up the shining reins, and eagerly set the strong-footed horses at once to follow the son of Tydeus. He was pressing after Aphrodite Kypris with the pitiless bronze, knowing that she was a god without strength, and not one of the goddesses who have mastery in men's battles, not Athene or Ares, the sacker of cities. But when he came up with her in his pursuit through the masses of men, then the son of great-hearted Tydeus sprang at her and lunging with his sharp spear stabbed at the wrist of her soft hand, and the spear pierced straight through the skin, through the immortal robe which the Graces themselves had made for her, above the base of the palm: and immortal god's blood dripped from her, ichor, which runs in the blessed gods' veins - they do not eat food, they do not drink gleaming wine, and so they are without blood and called immortals. She shrieked loud and let her son fall from her arms.”

The Iliad.

#study.#greek myth tag to be added.#okay but the idea that actually aphrodite is very protective of her half god daughter zelda? yes

2 notes

·

View notes