#2020 emerging poets

Text

April 24, 2024: How Can Black People Write About Flowers at a Time Like This, Hanif Abdurraqib

How Can Black People Write About Flowers at a Time Like This

Hanif Abdurraqib

dear reader, with our heels digging into the good

mud at a swamp’s edge, you might tell me something

about the dandelion & how it is not a flower itself

but a plant made up of several small flowers at its crown

& lord knows I have been called by what I look like

more than I have been called by what I actually am &

I wish to return the favor for the purpose of this

exercise. which, too, is an attempt at fashioning

something pretty out of seeds refusing to make anything

worthwhile of their burial. size me up & skip whatever semantics arrive

to the tongue first. say: that boy he look like a hollowed-out grandfather

clock. he look like a million-dollar god with a two-cent

heaven. like all it takes is one kiss & before morning,

you could scatter his whole mind across a field.

--

From the poet:

“I was at a reading shortly after the [2016] election, and the poet (who was black) was reading gorgeous poems, which had some consistent and exciting flower imagery. A woman (who was white) behind me—who thought she was whispering to her neighbor—said ‘How can black people write about flowers at a time like this?’ I thought it was so absurd in a way that didn’t make me angry but made me curious. What is the black poet to be writing about ‘at a time like this’ if not to dissect the attractiveness of a flower—that which can arrive beautiful and then slowly die right before our eyes? I thought flowers were the exact thing to write about at a time like this, so I began this series of poems, all with the same title. I thought it was much better to grasp a handful of different flowers, put them in a glass box, and see how many angles I could find in our shared eventual demise.”

—Hanif Abdurraqib

Today in:

2023: Lit, Andrea Cohen

2022: Meditations in an Emergency, Cameron Awkward-Rich

2021: How the Trees on Summer Nights Turn into a Dark River, Barbara Crooker

2020: Ash, Tracy K. Smith

2019: Under Stars, Dorianne Laux

2018: Afterlife, Natalie Eilbert

2017: There Are Birds Here, Jamaal May

2016: Poetry, Richard Kenney

2015: Dreaming at the Ballet, Jack Gilbert

2014: Vocation, Sandra Beasley

2013: Near the Race Track, Brigit Pegeen Kelly

2012: from Ask Him, Raymond Carver

2011: Sweet Star Chisel, Dearest Flaming Crumbs in Your Beard Lord, John Rybicki

2010: Rain Travel, W.S. Merwin

2009: Goodnight, Li-Young Lee

2008: Bearhug, Michael Ondaatje

2007: Meditation at Lagunitas, Robert Hass

2006: Autumn, Rainer Maria Rilke

2005: On Turning Ten, Billy Collins

39 notes

·

View notes

Photo

On this day, 9 February 2007, Alejandro Finisterre, the anarchist poet and inventor of the Spanish version of table football (foosball) died in Zamora, Spain. He invented the game following injury during the Spanish civil war and revolution so injured children could still play football. Fleeing following the fascist victory, he ended up in Guatemala, where he played table football with Che Guevara. After the US-backed military coup in the country, he was kidnapped by Francisco Franco's agents and put on a plane to Madrid. However on board he went to the toilet, wrapped a bar of soap in newspaper and emerged shouting "I am a Spanish refugee" and threatening to blow up the plane. Supported by the crew and passengers, the plane landed and let him off in Panama. Learn more about the Spanish civil war in our podcast episodes 39-40. Available on every major podcast app or here on our website: https://workingclasshistory.com/2020/06/17/e39-the-spanish-civil-war-an-introduction/ https://www.facebook.com/workingclasshistory/photos/a.296224173896073/2205557866296018/?type=3

234 notes

·

View notes

Text

[T]hose who live and think at the shore, where the boundary between land and water is so often muddied that terrestrial principles of Western private property regimes feel like fictions, can easily understand how indebted we are to waterways. [...] [T]hese interstitial spaces underpin theories of not only liminality, but also adaptation, flow, and interconnection. Shorelines, indeed, do much to trouble the neat boundaries, borders [...] of the colonial imaginary [...].

Wading in the shallows long enough makes apparent that the shallows is not a place, but a temporal condition of submerging and surfacing through water. [...] And so thinking about shallows necessitates attention to the multiplicity of water, and the ways that tides, rivers, storm clouds, tide pools, and aquifers converse with the ocean to produce [...] archipelagic thinking.

For Kanaka Maoli, the muliwai, or estuary, best theorizes shoreline dynamics: It is not only where land and water mix, but also where different kinds of waters mix. Sea and river water mingle together to produce the brackish conditions that tenderly support certain plant and aquatic lives. It also informs approaches to aloha ʻāina, a Native Hawaiian place-based praxis of care. As Philipp Schorch and Noelle M.K.Y. Kahanu explain,

the muliwai ebbs and flows with the tide, changing shape and form daily and seasonally. In metaphorical terms, the muliwai is a location and state of dissonance where and when two potentially disharmonious elements meet, but it is not “a space in between,” rather, it is its own space, a territory unique in each circumstance, depending the size and strength or a recent hard rain. [...]

---

[T]he muliwai might be better characterized not as a space, but instead as a conditional state that undoes territorial logics. Muliwai expand and contract; withhold and deluge; nurture and sweep clean. It is not a space of exception. Rather, it is where we are reminded that places are never fixed or pure or static.

Chamorro poet Craig Santos Perez reminds us in his critique of US territorialism that “territorialities are shifting currents, not irreducible elements.” If fixity and containment limit, by design, how futures might be imagined beyond property, then the muliwai envisions decolonial spaces as ones of tenderness, care, and interdependence. [...]

---

But what do we make of the muliwai, the shoal, or the wake, when its movements become increasingly erratic, violent, or unpredictable? [...] The disappearing glacier and the sinking island have become visual bellwethers for the so-called Age of the Anthropocene [...]. Because water has the potential to trouble the boundaries of humanness, it may furthermore push us to think through [...] categorical differences [...]. What happens when we turn our attention to the nonhuman in order to track anthropogenic mobilities; not to flatten the categories of human, but, rather, to consider the colonial mechanisms that produced hierarchies of bodies to begin with? [...] When we linger with waters at the shore, we open ourselves up to evidence that lands and waters are not distinct from each other, that they both flow and flee, and that keeping good relations is fundamental [...].

It is worth returning to the muliwai and its lessons in muddiness, movement, and care to think about the possibilities that emerge from the conditions of change that allow new life to take hold [...].

---

Text by: Hi’ilei Julia Hobart. “On Oceanic Fugitivity.” Ways of Water series, Items, Social Science Research Council. Published online 29 September 2020. [Some paragraph breaks added by me.]

98 notes

·

View notes

Text

BIOGRAPHICAL SUMMARY ON RAFAEL CASAL

Rafael Santiago Casal is an American writer, rapper, actor, producer, director and showrunner originally from the San Francisco Bay Area. He is also an online creator of poetry, music, web shorts and political commentary.

Raised between Berkeley and Oakland in California, Casal was able to build a respectable career, starting his apprenticeship as a slam poet at HBO's Def Poetry Jam and moving on to various fields of entertainment.

In the past he was a two-time champion of the Brave New Voice Poetry Slam Festival.

Among his most famous poems we remember:

Barbie & Ken 101

A.D.D.

Monster

Rafael is also known for being the collaborative partner and longtime friend with Daveed Diggs, also from the Bay Area and best known for his role as the Marquis de Lafayette in the musical "Hamilton." Their first album "THE BAY BOY Mixtape" will be the beginning of a long series of musical featurings.

Furthermore, both are co-founders of the BARS Workshop: a theater program to hone the skills of emerging writers and actors through verse. The latest season dates back to 2020.

Casal and Diggs even collaborated as actors and screenwriters in the 2018 film "Blindspotting" and from which the TV series of the same name was subsequently based, divided into two seasons. (2021/2022)

Daveed Diggs and Rafael Casal in their respective roles of Collin Hoskins and Miles Turner in Blindspotting. (2018)

On a cinematic level, Casal is also known for playing a former student in the 2019 film "Bad Education" with Hugh Jackman as his old high school teacher and love interest. In the same year he debuted in the reboot of "Are You Afraid of the Dark?" in the guise of Mr. Tophat as the main villain of the series. In 2020 he plays a minor role in "The Good Lord Bird."

On October 6, 2023, he arrives for the first time in the Marvel Cinematic Universe as a minor antagonist in the second season of Loki.

Rafael Casal as Brad Wolfe/Hunter X-5 in "Loki Season 2." (2023)

On May 3, 2024 he will return to the cinema in the role of O.E. Parker in "Wildcat", a film based on the life and stories of American writer Flannery O'Connor.

Being also active in the world of music, Rafael Casal has released several solo mixtapes online: "As Good As Your Word" (2008), "Monster" (2009) and "Mean Ones." (2012)

While among the most recent singles we list:

"Bad Egg" (2017)

"Oxygen" (2019)

"Quicksand" (2021)

Rafael has demonstrated that he can also manage as a Youtuber, publishing the following Web Series:

The Away Team

Hobbes & Me

The Rafatics (As a political commentator)

Warnings:

This biography is nothing less than a brief summary, for more information see elsewhere.

You can follow Rafael Casal on:

Instagram

Twitter/X

YouTube

TikTok

Spotify

Soundcloud

#rafael casal#biography#welcome everyone#the rafanatics#singer#musician#songwriter#writer#showrunner#slam poet#poet#bay boy#producer#artist#bay area

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Big Reputations: Celebrity and Temporal Duration in/of Dickinson Lyrics by Elizabeth Dinneny

Source (x)

On December 10, 2020, Emily Dickinson’s 190th birthday, singer-songwriter-superstar Taylor Swift announced the surprise release of her ninth studio album, evermore. The release was a shock, as Swift had released her first surprise album, folklore, a short five months previous. Swift called folklore “a product of isolation,” made together with a small group of musicians during the first several months of the COVID-19 pandemic. Its aesthetic, which continues into evermore, evokes the newly-popular “cottagecore” trend.[1] Swift spoke of her inspiration for the album’s cover photograph with Entertainment Weekly: “I had this idea…that it would be this girl sleepwalking through the forest in a nightgown in 1830” (Suskind). In folklore’s black-and-white cover image, Swift is the sleepwalking girl wearing a custom Stella McCartney jacket (Grindell) in the year of Emily Dickinson’s birth. In evermore’s full-color image, Swift has emerged from the woods and looks back toward it—notably diverging from the look of her eight previous album covers, in which her face appears up close, front and center. Perhaps evermore contains Swift’s least autobiographical lyrics, as some critics have suggested (Petrusich), thus opening up even more possibilities for fictional and biographical inspiration.[2] But we might take a more critical approach. Using the term “autobiographical” risks feigning individual influence and a singular archive. Taylor Swift is certainly known for writing specific autobiographical elements into her lyrics, but we need not abandon autobiography in the face of evermore’s expansive archive. Rather, we should ask: how do these archives mediate the autobiographic? Where do we find Swift and Dickinson, together, in “these imaginary/not imaginary tales” (@taylorswift13)?

The two so-called “sister record[s]” (@taylorswift13) contain stories from myriad archives, including allusions to Romanticism and Swift’s own life. While folklore, with its mentions of Wordsworth and the Lake District, appears invested in the figures and motifs of British Romanticism (Ellis), evermore seems most influenced by one writer in particular: Emily Dickinson. As a result of popular culture’s recent increased interest in Dickinson, Taylor Swift fans knew enough about the poet to begin speculating about Dickinson’s presence in evermore almost immediately. Most conspicuous is the album’s title (and concluding) track, “evermore,” which meditates on a failed relationship whose “pain would be for / evermore” (Swift et al.). The song recalls the final line of a letter-poem written by Emily Dickinson to Susan Huntington Dickinson. The poem ends:

I spilt the dew –

But took the morn, –

I chose this single star

From out the wilde night’s numbers –

Sue _ forevermore!

(OMC 76)

The song and the poem differ significantly in tone, as “evermore” recounts the miscommunications of a past relationship, and Dickinson’s letter expresses an endless devotion to her sister-in-law and lover, Susan Huntington Dickinson. However, both texts share an investment in letter-writing for the articulation and navigation of an intimate relationship. In “evermore,” one narrator is found “writing letters / addressed to the fire,” indicating a failure in communication and the eventual demise of the relationship. Dickinson’s letter-poem to Susan, in addition to celebrating an enduring relationship, demonstrates the value of the letter (and lyric) as a form of intimate expression. Far from being “addressed to the fire,” Emily Dickinson’s letter-poems made their way into Susan Huntington Dickinson’s hands, “a hedge away,” (OMC 76) for decades.

The duet’s speakers also use metaphors of shipwreck to recall their relationship’s collapse. For example, Swift sings, “Hey December / Guess I’m feeling unmoored,” and, later, Bon Iver sings, “I’m on the waves, out being tossed / Is there a line that I could just go cross?” These lines are only a few of evermore’s broad nautical and temporal vocabulary; the album opens with the line, “I’m like the water / when your ship rolled in that night” (Dessner and Swift). In “long story short,” whose joyful tone matches that of Dickinson’s aforementioned letter-poem, Swift sings, “my waves meet your shore / ever and evermore” (Dessner and Swift). The speaker of “long story short” hopes to moor, for evermore, in the song’s addressee. Here, we turn to Emily Dickinson again; in her poem that begins “Wild nights – Wild nights!”, the speaker is “Done with the Compass - / Done with the Chart!” and wishes to “moor” in the poem’s addressee:

Wild nights - Wild nights!

Were I with thee

Wild nights should b

Our luxury!

Futile - the winds -

To a Heart in port -

Done with the Compass -

Done with the Chart!

Rowing in Eden -

Ah - the Sea!

Might I but moor - tonight -

In thee!

(Fr269A)

Both Dickinson and Swift invoke the shore as the site of a relationship’s convergence.[3] The speakers escape turbulent waters by finding stability in another person, on the shore, repeatedly. The comparison is complicated by the conditional temporality of “wild nights,” and the poem’s queer interpretations and theorizations cannot go unstated (Smith, Brinck-Johnsen), By reading Dickinson and Swift together, we see how both lyricists consider temporality and the potential of a “forevermore” in multiple forms, including that of an intimate romantic relationship.

The folklore/evermore “era,” to use a Swiftian term (Braca), embraces a cottagecore aesthetic, easily identifiable in the album’s lyrics, acoustic instrumentation, woodsy cover art, and promotional images. The cottagecore aesthetic combines the fable of Dickinson the genius recluse with Dickinson the R/romantic, complementing the conditions and themes of both Swift albums. Swift’s most cottagecore song, “ivy,” has received significant attention from a number of Dickinson fans, who believe the song is inspired by Emily and Susan’s relationship. The album’s tenth track, which has been described as “a folky, convoluted song,” (Pareles) involves a married speaker who falls in love with someone else. The speaker describes the three of them (speaker, lover, husband) in a room, possibly at a party:

I wish to know

The fatal flaw that makes you long to be

Magnificently cursed

He’s in the room

Your opal eyes are all I wish to see

He wants what’s only yours (Swift, Antonoff, Dessner)

Neither the speaker nor the “magnificently cursed” lover are assigned pronouns, leaving plenty of room for queer interpretations of this song about a forbidden, passionate relationship, which the speaker calls “the goddamn fight of my life” (Swift et al). In their own queer readings, Dickinson fans have made fan videos of “EmiSue” scenes set to the song, whose lyrics can be cleanly mapped onto their relationship.[4] In addition to biographical consistencies, the characters of “ivy” employ metaphors of death and augmented temporality that resonate affectively with much of Dickinson’s poetry. The song begins in a graveyard, or at least a metaphorical one: “How’s one to know? / I’d meet you where the spirit meets the bones / In a faith-forgotten land” (Swift et al.).[5] The graveyard functions as a safe place for the two to get together, removed from the public eye and from the expectations of “the living.” Among the dead, the illicit affair of “ivy” is allowed to flourish, as the speaker sings, “my house of stone / your ivy grows, / and now I’m covered in you” (Swift et al).

Using botanical imagery, the speaker describes an organic infiltration of the “magnificently cursed” lover, or unruly ivy, on the married, heterosexual home. Further, the speaker sings, “the old widow goes to the stone every day / But I don’t, I just sit here and wait / Grieving for the living” (Swift et al.). With its affinity for the dead, this secret relationship thus appears unconcerned with linear time and social realities. The speaker grieves for their living relationship, which has yet to end, then happily escapes to “your dreamland” (Swift et al.). Emily Dickinson wrote many poems about death, graves,[6] and privacy.[7] Although we push back on the idea of Dickinson as recluse, Dickinson’s life-long romantic relationship with Susan was certainly enjoyed in private. Similarly, the contentedly secret relationship of “ivy” defies heterosexual expectations of public interpellation. Rather than become legible to friends (as the three seem to travel in similar circles) and family, the two, “a goddamn blaze in the dark,” endure.

Swift is known for leaving self-referential clues throughout her corpus, so it’s worth noting that evermore might not contain her first nod to Dickinson. repuation, Swift’s album most explicitly about her struggles with fame and social media, ends with the album’s most romantic and sole piano track, “New Year’s Day.” In the song, the speaker sings to another “you,” the morning after a New Year’s Eve party. A similar reflection on the duration of romantic relationships, Swift implores them, “Don’t read the last page,” and tells of what remains following the celebration:

There’s glitter on the floor

After the party

Girls carrying their shoes

Down in the lobby

Candle wax and Polaroids

On the hardwood floor

…you and me, forevermore

Here, again, Swift uses “forevermore” to describe hope for the endurance of an intimate relationship, just as she uses the phrase in “long story short” and “evermore.” “New Year’s Day” emerges as the album’s most cathartic moment. After numerous tracks about Swift’s most arduous years in the spotlight, “New Year’s Day” finishes the album as a song solely about her intentionally private relationship with current partner Joe Alwyn (Stanton). In addition to repeating the desire for a forevermore relationship, the more transparent “long story short” explicitly references these same reputation moments from Swift’s life and discography, offering a quick account of Swift’s romantic troubles and a longer reflection on Swift’s falling out of public favor. As one critic writes, “conceptually, it [“long story short”] retreads reputation ground,” (Ahlgrim and Larocca) featuring clear autobiographic elements and expressing a frustration with the attention and misogynistic demonization that accompanies fame: “And I fell from the pedestal / Right down the rabbit hole / Long story short, it was a bad time” (Dessner and Swift).

Rather than continue to pick apart evermore’s lyrics for possible references to Dickinson’s poetry (as there are plenty more[8]), we should turn to overlapping and interacting thematics and conditions of production. In social media posts and interviews, Taylor Swift emphasized the conditions of the sister albums’ production; that is, she underlined the fact that both were created “in isolation,” in relatively quick succession, and secretly amid a small circle of collaborators (@taylorswift13). Swift told Entertainment Weekly: “I wasn’t making these things with any purpose in mind. And so it was almost like having it just be mine was this really sweet, nice, pure part of the world as everything else in the world was burning and crashing and feeling this sickness and sadness. I almost didn’t process it as an album. This was just my daydream space” (Suskind). Emily Dickinson did not write her poetry during a global pandemic, but she did often write in a kind of isolation, disseminating her poetry among close friends and family with less regard for the expectations of print publishing (Smith). Isolation here means, of course, not the sequestration of the individual artist, but the cultivation of a small, trusted collective through which the artist’s work is circulated and workshopped. Their works-of-isolation now commercial and widely distributed art objects, both Dickinson and Swift have grown into infamous public figures, onto whom their readers, listeners, and critics project personalities, intentions, and rumors.

If Taylor Swift is a celebrity, then Emily Dickinson’s ghost is one as well. Dickinson’s ghost is the figure of Dickinson in and constructed by popular culture, shifting and disappearing into words and works like those discussed in this exhibition. By ghost, I mean the specter cast by fame, a formulation that Dickinson used in her own writing, “at a time when ghosts were ubiquitous within literary tourism and when a visit to the writer’s home or meeting with a celebrity was akin to a spiritual encounter” (Finnerty 34). Several speakers found in Dickinson’s poetry revere the dead like a fan might revere their favorite celebrity, visiting the star's birth place, home, and grave (Finnerty 45). The dead celebrity thus becomes a ghost, the product of public reverence or, to use a word from Swift’s lyrical vocabulary, the product of reputation. Though she did hope to publish, Dickinson ruminated on fame across many poems and letters, expressing a desire for it but also often a deep concern about the restrictions of print publishing (Reynolds, “I’m Nobody…”, Finnerty) and the potential misconstruing of the person by celebrity. Commercial publishing opens up the potential for a ghost, made immortal but out of the artist’s control, defined by critics, scholars, and other readers. In her lifetime, Dickinson’s handmade fascicles were self-published; she produced copies of poems, bound them together, and distributed them herself, but the fascicles on their own do not conjure the specters of Dickinson that we encounter today. Martin Greenup reads the inaccessible dead of Dickinson’s “Safe in their Alabaster chambers” as her own poems, the chambers her fascicles if she did not publish commercially (356). Without publishing, Dickinson and her poems would most likely not endure the unforgiving abyss of time, and her fascicles would remain untouched by generations of readers, safe but dead, we might say, “forevermore.”

Perhaps confirming her most serious anxieties and optimisms, Dickinson haunts writers and popular culture more than a hundred years after her death. Specters of her reputation emerge across these essays, making this exhibition a kind of graveyard of multiple Emily Dickinsons, none of them “true,” many of them contradictory. In Taylor Swift’s introduction to reputation, she writes that “gossip blogs will scour the lyrics” to explain the meaning of each song, connecting them to Swift’s ex-boyfriends and paparazzi photos. She concludes with a critique of celebrity and identity itself: “We think we know someone, but the truth is that we only know the version of them they have chosen to show us. There will be no further explanation. There will just be reputation” (Swift). Much of the same can be said about Emily Dickinson, whose poetry and larger archive has been scoured for evidence of male lovers, proof of her supposed isolation, and combed through for final, stable versions of her poems.[9] Despite these attempts at discerning the facts, there will only ever be Dickinson’s reputation, as constructed by her readers. We might respond to Swift’s assertion by asking what we do, then, with the archive. How should we interpret the archive of the living (or dead) person? Let us turn, one last time, to Dickinson’s own lyrics:

Fame is the one that does not stay —

It’s occupant must die

Or out of sight of estimate

Ascend incessantly —

Or be that most insolvent thing

A Lightning in the Germ —

Electrical the embryo

But we demand the Flame

The speaker is uninterested in fame, which remains at the mercy of cultural interest and the status of its dead occupant. Instead, the speaker urges us to “demand the Flame.” What Flame of Dickinson’s must we demand? Perhaps the Flame is another kind of ghost, but one that is much more difficult to make out. The Flame might be the stubborn specter that endures in spite of attempts at erasure or adjustment. Despite Mabel Loomis Todd, Higginson, and others’ efforts to shape Dickinson’s legacy into one more marketable, more heterosexual, and more conservative, there remains a stubborn ghost, a “goddamn blaze in the dark,” (Swift et al) deep in the archive. She appears only in flickers, but she endures, just as we must demand, over and over, to see her.

Swift’s evermore is only the most recent iteration of Dickinson in music; numerous artists and songwriters have been inspired by the poet. For a selection of these, explore the exhibition's curated Spotify playlist.

#gaylor#emily dickinson#literary references#evermore#folklore#ivy#reputation#new year's day#new years day#joe alwyn#gaylorarchive

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

professor's pet, pt. 3

The next semester, I signed up for the professor’s literature class. Several of my friends were in the class. We were loud and silly and everyone was trying to impress each other with their opinions on the texts the professor built his career on. But he had that special ability to make us feel comfortable enough to be our weird, nerdy selves. The class was a real-life Dead Poet’s Society, at least for the few weeks we were together.

He seemed unable to hide his focus on me. If I leaned my head over to rest, he’d lean into my ear to ask if I was okay instead of listening to the student speaking. During a guest lecturer’s speech, I got up to excuse myself and he followed just after, prompting an intimate moment translucent to the entire class, pressing to make sure I was okay. He gave me a box of Thin Mints and walked me out to the parking lot late when no one else was around and my car smelled like weed. He always held the door for me and never failed to provide a chivalrous hand to help me. One day, I remind him about something he forgot to send me, and he earnestly promised to be better to me, better for me. Surely, he’s naturally a gentleman, and all of these happenings are little things that happened to every other woman he had eyes for, but there was a slow flame burning between us.

And I’m not the only one who felt it.

Two of my friends approached me and asked what was going on between us. I don’t say that anything is, but I don’t say that anything isn’t either.

“I knew it! He treats you differently. It’s really noticeable.”

“I’ve never seen him act that way with anyone. I can’t even get him to answer an email.”

I wished I’d been more willing to see the warning signs. But as always, I was intoxicated with his obsession with me. I couldn’t help but continue to provide the temptation, continue playing the chess game.

Just before spring break, I borrowed an expensive book of his for a prospective project. It was March 2020. COVID destroyed the world overnight. I stayed in Florida and he went back to the Midwest. We didn’t see each other for two years.

Yet, we kept in touch, even though there was no reason. He remembered texted me each year on my birthday and Thanksgiving and even early on Christmas morning when the last thing on his mind should be a student. I have a distinct memory of him saying he didn’t do things like that because he too often forgot. We talked occasionally about my thesis and Ph.D. applications.

He started texting me late at night. But no boundaries were crossed, yet.

We talked about seeing each other when he came back. I decided to stay at Another University for another degree, hopeful I’ll be able to establish a long-term career and finally achieve job stability. I take classes and teach online, staying concerned and vigilant about COVID long after the rest of the world decided to leave it behind.

During the time the professor and I were separated, I met my friend Jane. We quickly became close, she moved to Florida, and we started hanging out regularly.

*

In the spring, the professor returns.

I still work remotely, but Jane sees the professor often. She tells me they talk about how wonderful I am, and how we should hang out with her and her husband. I told her nothing about the seemingly endless slow burn.

She comes over to my house one night, gushing.

“Isn’t he so cute? And single? I almost can’t believe it…”

“Yeah, he’s a mystery! No denying that.”

Jane pauses, lighting another cigarette and sipping on a condensed glass of wine.

“Have I told you I’m in an open relationship?”

I’m caught off guard; I don’t expect this.

“Oh…that’s interesting!”

“Yeah—our rules are ‘don’t ask, don’t tell,’ unless it’s important or an emergency.”

“And that’s worked for you?” I already knew it hadn’t, or it wouldn’t forever.

“Oh yeah! Being open makes the marriage so much better.” She has that devil look in her eyes. “I’ve had a few boyfriends since we’ve been married. And now, I might have my sights set on a new one…”

“______?” His name burns on my tongue. I’ve always hated saying it.

“Of course! If I can ever figure him out. I think he’s flirting back at me, but I can’t tell if that’s just his personality.”

I smile, not really wanting to continue the conversation but trying to look unbothered.

“What is it?” she drags the cigarette stub. “I can tell there’s something you want to say.”

At this moment, I trust her, I think she’s my friend.

And in a lapse of judgment, I tell her about our flame.

I explain the situation to her with as much ration as I can. And that’s what it is—a situation between a student and professor quickly nearing sticky territory. I tell her the situation is confusing for me and there’s something unexplainable about the connection. I tell her I can’t deny my attraction to him and I’m not sure where this will ever end up.

“Hmm,” she says after I finish. She holds herself in that way I’m unsure of. “Well, I wouldn’t take him too seriously.” She finally puts out the cigarette, burnt through the filter.

“But I’m still gonna try to fuck him anyway.”

I should have known at this moment to cut her off.

#creative nonfiction#creative writing#memoir#writeblr#writers on tumblr#writing#academia#graduate school

1 note

·

View note

Text

In the introduction to Together in a Sudden Strangeness, an anthology of American poems written into the cataclysm of 2020, editor Alice Quinn, another student of Emily Dickinson, quotes the lines “There’s been a Death in the Opposite House, / as lately as Today—”: words with increased resonance in that first Covid spring, when poets across the land were writing their way through fear and illness. Some, we learn in the anthology’s pages, were also working doctors on the front lines; some were teachers learning to Zoom; many were mourning the systemic inequalities the pandemic brought urgently to the fore. It’s hard to choose just one from this vivid congress of poets; we offer a trio on the theme of communication in isolation.

Corona Diary

by Cornelius Eady

These days, you want the poem to be

A mask, soft veil between what floats

Invisible, but known in the air.

You’ve just read that there’s a singer

You love who might be breathing their last,

And wish the poem could travel,

Unintrusive, as poems do from

The page to the brain, a fan’s medicine.

Those of us who are lucky enough

To stay indoors with a salary count the days

By press conference. For others, there is

Always the dog and the park, the park

And the dog. A relative calls; how you doin’?

(Are you a ghost?) The buds emerge, on time,

For their brief duty. The poem longs to be a filter, but

In floats Spring’s insistence. We wait.

If Indeed I Am Ill, Brother,

by Julia Guez

Tell me about London, the weather there

in spring outside the walls of the Great Hall.

These things matter less to me than the sound

of your summary, shadows cast on the watery

surfaces of my mind by invisible fingers

whose energy is everything, as you know.

These sonatas, these scores, tell me

what of them will last when everything falls away—

Tea for You, Too

by Ron Padgett

My friends,

I want to tell you

that in general things

are all right with me,

relatively speaking.

Just a second, here’s Einstein

asking where the tea is.

I reassure him

it will be ready soon,

relatively speaking,

and he shuffles back

to the room that holds him,

with plenty of space

for that cup of tea,

even though the cup

is twelve feet in diameter,

about the same size

as my thinking of you

this morning.

. .

More on this book and author:

Learn more about Together in a Sudden Strangeness edited by Alice Quinn.

Browse other books by Cornelius Eady, Julia Guez, and Ron Padgett.

Visit our Tumblr to peruse poems, audio recordings, and broadsides in the Knopf poem-a-day series.

To share the poem-a-day experience with friends, pass along this link.

#TogetherAudio#together audio#poem-a-day#knopf poetry#knopfpoetry#national poetry month#poem#books#knopf#poetry#PadgettAudio#Together in a sudden strangeness#guezaudio#eadyaudio

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Erotic Things

there is no self just rapture

By Rajiv Mohabir

The texture of wet clay on a throwing wheel

The blue of an eastern bluebird when spring crashes on the heels of winter

Keats’s negative capability has the potential

*

Mistaking your lover for someone else when he turns his back

Exotic sounds like exotic. But not when people call me this

*

The erotic makes sense when we think of jouissance and how that means there is no self just rapture. When I say jouissance, I like the eroticism of it being in French with that final nasal and sibilant. Doesn’t this sound like how a romance novelist would write it—and to me my own auto-colonial reading is not erotic, of French that is. Of English and Spanish too—they sound like colonial coercion, and that’s not erotic.

*

The pharmakon: how snake venom poisons, how the antidote distills from that very venom

The space of indeterminacy

*

Dark-skinned men in short shirts and shorts, men with bubble butts and thick thighs

*

“Another important way in which the erotic connection functions is the open and fearless underlining of my capacity for joy.” —Audre Lorde

*

Queers and not fitting in one envelope or one’s shorts

But maybe eros is exotic, and by this, I mean the very textural gesture of the word, what it points to, what we hide in clothes or words

*

The texture of language

The linguistic texture of Bhojpuri, Creolese, and English brush up together—living their taboos together—through the act of emergence despite repression

Secret languages that we speak to each other in

*

The lips when they bite strawberries, how they envelop the red

Swollen strawberry guava. The smell as they rot on the ground—like wine. I remember tramping through a sprawling forest path at Kuli‘ou‘ou Ridge where the forest floor practiced its winemaking. The entire climb was perfumed and that was erotic, the emerald of the mountain, the cloud cover like fog and the turning of sugar into liquor.

Rajiv Mohabir is the author of Cutlish (Four Way Books 2021, finalist for the 2022 National Book Critics Circle Award, longlisted for the 2022 PEN/Voelcker Award for Poetry), The Cowherd’s Son (Tupelo Press 2017, winner of the 2015 Kundiman Prize; Eric Hoffer Honorable Mention 2018), and The Taxidermist’s Cut (Four Way Books 2016, winner of the Four Way Books Intro to Poetry Prize, finalist for the Lambda Literary Award for Gay Poetry in 2017), and translator of I Even Regret Night: Holi Songs of Demerara (1916) (Kaya Press 2019) which received a PEN/Heim Translation Fund Grant Award and the 2020 Harold Morton Landon Translation Award from the Academy of American Poets.

His essays can be found in places like Asian American Writers Workshop’s The Margins, Bamboo Ridge Journal, Moko Magazine, Cherry Tree, Kweli, and others, and has been a “Notable Essay” in Best American Essays 2018. His memoir Antiman (Restless Books 2021, finalist for the PEN Open Book Award, and the 2022 Publishing Triangle Randy Shilts Award and the Lambda Literary Award for Gay Memoir), received the 2019 Restless Books Prize for New Immigrant Writing. Currently he is an assistant professor of poetry in the MFA program at Emerson College and the translations editor at Waxwing Journal.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

6.3 Transcriduction

This translation is inspired by Charles Bernstein’s contribution to Chain 10, which used a source text culled from an email from his Chinese translator, and translated that into multiple languages. It is also of course inspired by the final procedure in Mónica de la Torre’s Repetition Nineteen which translates a conversation by group of translators collectively translating de la Torre’s Equivalencies/Equivalencias into Russian. Outranspo is also currently preparing a transcsritranslation of their translation of the Chinese poem “Lion-Eating Poet in the Stone Den” (pp.)

Materials.

• A text for translation, ideally something that will inspire conversation.

• A transcription surface (pen and paper or computer); alternatively the conversation can be recorded and transcribed later, but there is also something interesting about what the transcriber hears and is able to translate.

Players.

• Translators, at least two.

• A transcriber, at least one.

Steps

• Translators translate, talking through their choices, doubts, hesitations etc. as they go.

• The transcriber transcribes what they hear

• The group collectively rereads the transcription, potentially editing.

Examples

This example is taken from a workshop I lead in 2020 with the participants in the Diplôme Universitaire pour les animateur.ice.s des aterliers d’écriture creative, a University certificate program at the Université Paul Valéry Montpellier 3 that trains creative writing workshop guides.

Traduire « Equivalencies/Equivalencias » de Monica de la Torre

Atelier de traduction créative du 30 septembre, 2020

dans le cadre du DU d’animateur.ice.s d’ateliers d’écriture créative

Est-ce qu’il y a quelqu’un qui arrive à lire ça

One silence flare

Flare c’est quoi

J’ai pas compris

On lit les deux phrases

Qu’est-ce que ça veux dire flare

C’est le nez

Ça c’est une traduction créative

C’est l’intuition

C’est appeler

On va regarder sur internet

Mais c’est féminin

C’est féminin un flare

Il y a des mots qui sont féminins en espagnol et en français

Une fusée ils disent

Attend je vais vérifier

Tu as regardé sur DeepL ?

Non sur Google Translate

C’est peut-être un appel

Un appel ?

Ben voilà

On n’est pas obligé de traduire

Un appel un silence

Une fusée une éclatée

J’ai pas envie de traduire

Est-ce que le but c’est de traduire de façon créative

Je mets juste hakuna matata

Je vais prendre les notes là

T’es sur Deep Lie ?

Qui c’est qui sait ce que veux dire un flare

J’ai un truc avec le cancer

C’est un quoi un sin

C’est un vice

Un vice de café c’est bizarre

Je comprends rien

Un un silence

C’est

Un sin of coffee

A sip c’est une gorgée de café

Avant qu’il soit amer

Avant que ce soit amer

Une gorgée de café avant qu’il soit froid

ou amer

enfin caféine

La flare je trouve une poussée

Moi je veux pas traduire

Je veux pas faire ça

Un silence une lueur

Ah bon

Si Google arrive pas j’arrive pas

La réaction de llamarada en parenthèses flare

Quand tu traduis en français c’est une poussée

Se manifeste par tumorale

Il faut voir le sens qui se recouvre avec l’espagnol

Burning light

Attract attention in an emergency

Bright burning light

Une fusée éclairante. Ou bien une flambée

Une fusée

On continue à traduire la suite et on choisira

Mais ça fait vachement longue

avant l’amertume

Un soupçon peut-être

Toute la question c’est est-ce qu’on est créatif ou est-ce qu’on est fidèle

On peut dire c’est un trou

Un trou c’est rigolo

Un espace dans un trou

Un gouffre

Faut trouver un autre mot à part trou

J’aime bien trou

Translate

Un truc dans un machin

Un trou dans un trou

Une lacune dans un trou

C’est bien un trou dans un trou

Oui mais ça appauvri par rapport à l’original

C’est pas sûr

C’est prétentieux

Et en espagnol

Un espace un écart

C’est vraiment un espace

Ça fait plus un espace dans un trou

DeepL il dit une lacune dans un trou

Une lacune

Ça peut être un manque

Oui ça peut être un manque

On met quoi

Mais on met tous collectivement quelque chose

Un manque dans un trou je préfère parce qu’il y a deux mots différent

Un manque dans un trou c’est assez joli

Ça me plait

Un manque dans un trou pourquoi pas

Ou un trou dans un manque

Le trou fait débat

Il nous reste flare

Mais non c’est lueur

C’est soit lueur soit éclat

Un silence un éclat

Un un silence un éclat

C’est à la fois la lueur et une poussée

Un un silence un éclat

On s’était pas mis d’accord

Après ça peut être un soupçon de café

Toi tu dirais avant l’amertume

Avant qu’il soit amer

De sens

Soit amer quoi

Je garderais ça

Ça complète le sens

On vote

La dernière vous avez dit quoi

Je trouve ça pas très jolie

Un trou dans un manque

Ah ben non

L’original c’est l’espagnol ou l’anglais en fait

C’est pas hoyo

J’arrive pas à lire

C’est quoi on sait pas là

Hoyo c’est trou

C’est un trouillot dans un trou

Un rouillot a dentro

T’as le g qui vient dessus

C’est quoi la lettre

Rouillot ou trouillot

La dernière strophe du poème peut nous aider

Et oui on ne l’a pas même pas lu en entier

Ah ben on est obligé de traduire

J’arrive pas à traduire là

Je comprends pas ce qu’il faut traduire

Moi je reste en mode médiéval

Je vais ramener mon phlegme

C’est une bouée dans un trou

Une oreille l’hoyo

Je vais essayer de traduire la suite

Espace

C’est les yeux oyos

Espace en espagnol

C’est un h

Ben oui c’est un h

Un trou dans un trou

Un trou dans le vide

Les deux

Un trou dans le vide ça vous va pas ?

Comment dire espace en espangol ?

Agujero c’est quoi ?

Alors le vide c’est vraiment très créatif

Il n’y a rien rempli

Un trou dans le néant

En espagnol il y a des o partout

Il y a un vide dans ton cours

Un trou dans le vide c’est pas mal ça

Un silence un un silence

Du coup gap c’est pas vraiment trou c’est écart distance intervalle l’omission le vide

Ça c’est joli

Alors ce serait un espace dans le vide

S’il y a vide

Vide intervalle manque

Vide dans un trou

Les deux mots veulent dire trou

Ah vous voulez créer ben si vous voulez créer

Je trouve que le mot intervalle est joli

Un intervalle dans le vide

The gap between intervalle entre

Ecart un écart dans le vide

Un espace sinon

Les trous dans le vide c’est joli

Trou dans le vide est mieux que l’espace dans le vide

Mais c’est moche le mot trou

Moi je préfère trou dans le vide

Alors on vote

Ce sera plus rapide

Alors on vote

Ça vide dire trou vide

Venez on vote sinon on va rester quatre cents ans

Attends on vote entre quoi et quoi

Il y avait un manque dans un trou

C’est super glauque

Il y a un trou dans un trou

Un espace dans le vide

Un manque dans un trou

Il y avait quoi je ne me souviens plus

Un intervalle dans le vide

Dans le vide ? Toujours dans le vide

Ben il y avait trou

Là tu tombe là

Là on fait un écart en plus

Bon allez c’est l’espace dans le vide qui a gagné

C’est fossé aussi

Qui s’oppose à l’espace dans le vide

Moi je m’oppose dans un manque dans un trou

C’est la majorité qui gagne

Allez ça marche

C’est un peu tirer sur les cheveux

C’est le coffee le coffee trou le trou noir

Le coffee trou

C’est pas dans le vide ça peut être dans le vide

Oui mais on est créatif donc on passe par le vide parce que ça sonne mieux

Alors on vote sur le ou un ?

En français on dit le on dit pas un

Un grand vide ça fait répétition c’est pas très joli

C’est ce qu’elle fait elle répète

Ça contient un truc super

Dans les deux ce qu’elle fait c’est répéter

On est d’accord soyons fidèles

On ne sait pas

Dans le sens espagnol

Oui

Alors ça donne quoi

Un espace dans le vide un espace dans un vide

Si on met un espace au vide ça va pas

Espace vide voilà

Café amer on se dépêche

Ça donne quoi

J’ai un. Un silence. Je ne sais pas. Un éclat

Oui un éclat

Une gorgée de café avant qu’il soit amer ou avant l’amertume

Vous préférez un soupçon

Ah non ah non je ne suis pas d’accord

Ah oui c’est mieux un soupçon une gorgée ça n’a pas le même sens

Un zeste !

Qui gorgée !

Qui veut gorgée de café !

Qui veut soupçon

Ben c’est proche

On n’a pas compté

Non ben on a gagné

Avant l’amertume !

Ah non avant qu’il soit amer !

Avant qu’il ne supprime l’amertume !

Ah ça c’est poétique

Un café avant la mer avant la mer et la montagne

Qu’il soit amer j’ai l’impression

Moi seule

Ensuite on remonte

J’ai juste une question

J’ai juste une question à Lily, on fait une traduction littérale ou on fait une interprétation

A mon avis le plus simple c’est de faire une traduction littérale parce que si on fait une interprétation le consensus sera beaucoup plus difficile

C’est le verbe être au passé ?

Après taste il y a l’idée du gout

Ça veut dire supprime

Avant qu’il ne supprime l’amertume

C’est lourd

Ben non c’est DeepL

Quoi non

Je ne sais pas pourquoi il traduit comme ça

Il y en a qui disent ça

Bon on a tout

Non pas du tout

Je ne sais toujours pas

Moi c’est l’amertume

On a dit qu’on soit fidèle au texte

Ça n’existe pas la fidélité au texte

Ne supprime pas

Qu’il avait un gout amer

Avant qu’il ait un gout amer

Oui mais Google

C’est plus français

C’est supprime

C’est pas un l c’est un i

Dans la poésie ça suggère ça dit pas mot à mot le truc

Un poème c’est censé être un peu joli quand même

Je vous lis pour voir si ça fait un peu de sens

Avant qu’il je trouve que ça cloche

Mais il y a pas le gout amer

Mais on s’en fiche on adapte

C’était plus fluide

Avant l’amertume

On a le taste on a tout

C’est pas mal

Moi je trouve qu’au niveau du rythme c’est plus fourni

L’amertume c’est un peu sec

Vous préférez un deux ou trois

C’est le troisième l’amertume

En anglais before it tasted il n’y a pas que que que

C’est à l’oreille

Qu’est-ce qui nous plaît

Je crois que chacun

Il faut voter

Je refais

DeepL Translation into English

Is there anyone who can read this

One silence flare

What is flare

I don't understand

We read the two sentences

What does flare mean

It's the nose

This is a creative translation

It's intuition

This is calling

We'll look it up on the internet

But it's feminine

It's feminine a flare

There are words that are feminine in Spanish and in French

A rocket they say

Wait, I'll check

Did you check on DeepL?

No on Google Translate

Maybe it's a call

A call?

Well, that's it.

We don't have to translate

A call a silence

A rocket a burst

I don't want to translate

Is the point to translate creatively

I just put hakuna matata

I'll take the notes here

Are you on Deep Lie?

Who knows what a flare means

I got a thing about cancer

It's a what a sin

It's a vice

A coffee vice is weird

I don't get it

A silence

It is

A sin of coffee

A sip is a sip of coffee

Before it is bitter

Before it's bitter

A sip of coffee before it is cold

or bitter

finally caffeine

The flare I find a push

I don't want to translate

I don't want to do that

A silence a glow

Oh well

If Google doesn't come I don't come

llamarada's reaction in flare brackets

When you translate in French it is a push

Is manifested by tumoral

It is necessary to see the sense that overlaps with the Spanish

Burning light

Attract attention in an emergency

Bright burning light

A flare. Or a flare

A flare

We continue to translate the rest and we will choose

But it is really long

before the bitterness

A hint maybe

The question is whether we are creative or faithful

You can say it's a hole

A hole is funny

A space in a hole

An abyss

You have to find another word besides hole

I like hole

Translate

A thing in a thingy

A hole in a hole

A gap in a hole

It's a hole in a hole

Yes, but it's poorer than the original

It's not safe

It's pretentious

And in Spanish

A space a gap

It's really a space

It's more like a gap in a hole

DeepL it says a gap in a hole

A gap

It can be a gap

Yes it can be a gap

We put what

But we all collectively put something

A gap in a hole I prefer because there are two different words

A lack in a hole is quite nice

I like that

A lack in a hole why not

Or a hole in a hole

The hole is debated

It remains us flare

But no, it's glow

It is either glow or glare

A silence a glare

A silence a glare

It's both a glow and a push

One silence one burst

We didn't agree

Afterwards it can be a touch of coffee

You would say before the bitterness

Before it was bitter

Of sense

Be bitter what

I would keep this

It completes the meaning

We vote

The last one you said

I find it not very pretty

A hole in a gap

Oh no

The original is Spanish or English in fact

It's not hoyo

I can't read it

What is it we don't know

Hoyo is hole

It is a hole in a hole

It's a hole in a hole

You've got the g on it

What is the letter

I'm not sure if it's a hole or a rouillot

The last stanza of the poem can help us

And yes we haven't even read it all

Ah well we are obliged to translate

I can't translate it now

I don't understand what to translate

I'll stay in medieval mode

I'll bring my phlegm

It is a buoy in a hole

An ear the hoyo

I'll try to translate the rest

Space

It is the eyes oyos

Space in Spanish

It is an h

Yes, it's an h

A hole in a hole

A hole in the void

Both of them

A hole in the void doesn't suit you?

How to say space in espangol?

What is Agujero?

So the void is really very creative

There is nothing filled

A hole in the void

In Spanish there are o's everywhere

There is a void in your course

A hole in the void that's not bad

A silence a silence

So gap is not really hole it's gap distance interval omission the void

That's nice

Then it would be a space in the void

If there is a void

Void interval lack

Void in a gap

Both words mean hole

Ah you want to create well if you want to create

I think the word interval is nice

An interval in the gap

The gap between interval between

Gap a gap in the void

A gap otherwise

The gap in the void is nice

Hole in the void is better than space in the void

But it's ugly the word hole

I prefer hole in the void

So we vote

It will be faster

So we vote

It means empty hole

Come on, let's vote or we'll stay four hundred years

Wait, we vote between what and what

There was a gap in a hole

It's super creepy

There's a hole in a hole

A space in the void

A gap in a hole

There was what I can't remember

A gap in the void

In the void? Always in the void

Well there was a hole

There you fall

There we make a gap in addition

Well, it's the space in the void that won

It's ditch too

Who opposes the space in the void

I oppose myself in a lack in a hole

It is the majority which wins

Go it works

It is a little drawn on the hair

It is the coffee the coffee hole the black hole

The coffee hole

It's not in a vacuum it can be in a vacuum

Yes but we're creative so we'll go with the void because it sounds better

So we vote on the or a?

In French we say le we don't say un

A big empty space that makes repetition it is not very pretty

That's what she does, she repeats

It contains a super thing

In both what it makes it is to repeat

We agree let's be faithful

We don't know

In the Spanish sense

Yes

Then it gives what

A space in the void a space in a void

If we put a space in the void it will not go

Empty space, that's it

Bitter coffee we hurry

What does it look like?

I have a. A silence. I don't know. A burst

Yes, a burst

A sip of coffee before it's bitter or before the bitterness

You prefer a sip

Ah no ah no I don't agree

Ah yes, it's better a sip a sip doesn't have the same meaning

A zest!

A sip!

Who wants a sip of coffee!

Who wants a sip

Well, it's close

We didn't count

No well we won

Before the bitterness!

Oh no, before it is bitter!

Before it removes the bitterness!

Ah that's poetic

A coffee before the sea before the sea and the mountain

That it is bitter I have the impression

I alone

Then we go back up

I have just one question

I have just one question for Lily, do we do a literal translation or do we do an interpretation

In my opinion, it's easier to do a literal translation because if you do an interpretation, the consensus will be much more difficult

Is it the verb to be in the past tense?

After taste there is the idea of taste

It means to remove

Before it removes the bitterness

It is heavy

No, it's DeepL

What no

I don't know why he translates like that

Some people say that

Well, we have everything

No we don't

I still don't know

I'm bitter

We said we would be faithful to the text

There is no such thing as being faithful to the text

Do not suppress

That it had a bitter taste

Before it had a bitter taste

Yes but Google

It is more French

It's deleted

It's not an l it's an i

In poetry it suggests it doesn't say the thing word for word

A poem is supposed to be a little pretty

I read you to see if it makes sense

Before I find out it's not right

But there's no bitter taste

But we don't care, we'll adapt

It was more fluid

Before the bitterness

We got the taste we got it all

It's not bad

I think that the rhythm is more complete

The bitterness is a bit dry

You prefer a two or three

It's the third bitterness

In English before it tasted there is not that that

It is to the ear

What we like

I believe that each one

It is necessary to vote

I do it again

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Poetry as Survival

In the Special Section “Inspiration” in the Jan/Feb 2020 Poets&Writers Magazine, several of the poets used the word “survival” when talking about how their collection began.

P&W Collage #19 – Survival

Heidi Andrea Restrepo Rhodes who wrote The Inheritance of Haunting (assoc link) said, “This book emerged as a result of poetry as a mode of survival and healing at the intersections of my own…

View On WordPress

#April challenges#April PAD Challenge#Blogging A to Z Challenge#collage#NaPoWriMo#National Poetry Month#new poem#poetry#poetry forms#poetry immersion#portable MFA#prompts#writers#writing

0 notes

Text

April 29, 2023: June, Alex Dimitrov

June

Alex Dimitrov

There will never be more of summer

than there is now. Walking alone

through Union Square I am carrying flowers

and the first rosé to a party where I’m expected.

It’s Sunday and the trains run on time

but today death feels so far, it’s impossible

to go underground. I would like to say

something to everyone I see (an entire

city) but I’m unsure what it is yet.

Each time I leave my apartment

there’s at least one person crying,

reading, or shouting after a stranger

anywhere along my commute.

It’s possible to be happy alone,

I say out loud and to no one

so it’s obvious, and now here

in the middle of this poem.

Rarely have I felt more charmed

than on Ninth Street, watching a woman

stop in the middle of the sidewalk

to pull up her hair like it’s

an emergency—and it is.

People do know they’re alive.

They hardly know what to do with themselves.

I almost want to invite her with me

but I’ve passed and yes it’d be crazy

like trying to be a poet, trying to be anyone here.

How do you continue to love New York,

my friend who left for California asks me.

It’s awful in the summer and winter,

and spring and fall last maybe two weeks.

This is true. It’s all true, of course,

like my preference for difficult men

which I had until recently

because at last, for one summer

the only difficulty I’m willing to imagine

is walking through this first humid day

with my hands full, not at all peaceful

but entirely possible and real.

--

(June is my birthday month and also the best month. Sorry, I don’t make the rules.)

More like this:

» Steps, Frank O'Hara

» After Work, Richard Jones

» Dolores Park, Keetje Kuipers

» Awaking in New York, Maya Angelou

» A Step Away From Them, Frank O'Hara

Today in:

2022: Poem to My Child, If Ever You Shall Be, Ross Gay

2021: Choi Jeong Min, Franny Choi

2020: Earl, Louis Jenkins

2019: Kul, Fatimah Asghar

2018: My Life Was the Size of My Life, Jane Hirshfield

2017: I Would Ask You To Reconsider The Idea That Things Are As Bad As They’ve Ever Been, Hanif Abdurraqib

2016: Tired, Langston Hughes

2015: Democracy, Langston Hughes

2014: Postscript, Seamus Heaney

2013: The Ghost of Frank O’Hara, John Yohe

2012: All Objects Reveal Something About the Body, Catie Rosemurgy

2011: Prayer, Marie Howe

2010: The Talker, Chelsea Rathburn

2009: There Are Many Theories About What Happened, John Gallagher

2008: bon bon il est un pays, Samuel Beckett

2007: Root root root for the home team, Bob Hicok

2006: Fever 103°, Sylvia Plath

2005: King Lear Considers What He’s Wrought, Melissa Kirsch

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

Remembering King Von: A Legacy of Authenticity and Artistic Brilliance

In the realm of hip-hop, certain artists leave an indelible mark on the genre, not only with their music but also with their authenticity, storytelling, and raw talent. King Von, with his gritty lyrics, street narratives, and undeniable charisma, emerged as a force to be reckoned with in the world of rap. Though his life was tragically cut short, his impact on the music industry and his devoted fanbase endures as a testament to his artistic brilliance and uncompromising authenticity.

The Rise of a Street Poet:

Born Dayvon Daquan Bennett on August 9, 1994, in Chicago, Illinois, King Von's early life was marked by the harsh realities of street life. Growing up in the notorious O'Block neighborhood, he experienced firsthand the struggles, violence, and hardships that would later become the focal points of his music. Turning to rap as a means of self-expression and catharsis, King Von honed his craft with an authenticity and rawness that resonated deeply with listeners.

Authenticity in Artistry:

What set King Von apart from his contemporaries was his unwavering commitment to authenticity in his music. Drawing inspiration from his own experiences and the realities of street life, he painted vivid portraits of survival, betrayal, and redemption through his lyrics. His storytelling prowess and ability to capture the nuances of life in the inner city earned him widespread acclaim and a devoted following.

A Voice for the Streets:

King Von's music served as a voice for the streets, shedding light on the struggles and complexities of life in urban America. From his breakthrough mixtape, "Grandson, Vol. 1," to his acclaimed album, "Welcome to O'Block," he captivated audiences with his vivid storytelling and unfiltered honesty. Tracks like "Crazy Story" and "Took Her to the O" became anthems for a generation, cementing King Von's status as a rising star in the rap game.

Tragic Loss, Enduring Legacy:

On November 6, 2020, tragedy struck when King Von was fatally shot during a dispute outside a nightclub in Atlanta, Georgia. His untimely passing sent shockwaves through the hip-hop community, leaving fans and fellow artists mourning the loss of a true talent. Despite his premature departure, King Von's legacy lives on through his music, which continues to resonate with listeners around the world.

Honoring a Legend:

In the wake of his passing, tributes poured in from fans and fellow artists alike, honoring King Von's impact on the music industry and the lives he touched. From heartfelt social media posts to tribute songs and murals, his memory lives on as a reminder of the power of authenticity, storytelling, and artistic brilliance.

Conclusion:

Though King Von's life was tragically cut short, his legacy as a street poet and lyrical genius endures. Through his music, he immortalized the struggles and triumphs of life in the inner city, leaving behind a body of work that continues to inspire and resonate with listeners worldwide. As we remember King Von, we celebrate not only his artistic brilliance but also his unwavering commitment to authenticity and truth in a world often marked by illusion and artifice. Rest in power, King Von. Your voice lives on.

0 notes

Text

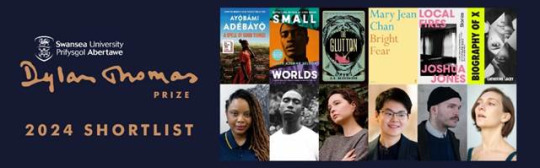

Independent publishers dominate Swansea shortlist

The shortlist for the world’s largest and most prestigious literary prize for young writers – the Swansea University Dylan Thomas Prize – has been revealed, featuring six emerging voices whose writing plays with formal inventiveness to explore the timeless themes of grief, identity and family.

Comprising of four novels, one short story collection and one poetry collection – with five titles belonging to independent publishers – this year’s international shortlist is:

A Spell of Good Things by Ayòbámi Adébáyò (Canongate Books) – novel (Nigeria)

Small Worlds by Caleb Azumah Nelson (Viking, Penguin Random House UK) – novel (UK/Ghana)

The Glutton by AK Blakemore (Granta) – novel (England, UK)

Bright Fear by Mary Jean Chan (Faber & Faber) – poetry collection (Hong Kong)

Local Fires by Joshua Jones (Parthian Books) – short story collection (Wales, UK)

Biography of X by Catherine Lacey (Granta) – novel (US)

Worth £20,000, this global accolade recognizes exceptional literary talent aged 39 or under, celebrating the international world of fiction in all its forms including poetry, novels, short stories and drama. The prize is named after the Swansea-born writer Dylan Thomas and celebrates his 39 years of creativity and productivity. The prize invokes his memory to support the writers of today, nurture the talents of tomorrow, and celebrate international literary excellence.

Namita Gokhale, chair of Judges, said: “The Swansea University Dylan Thomas Prize has an important role to play in recognizing, supporting and nurturing young writers across a rich diversity of locations and genres. The 2024 shortlist has authors from the United States, United Kingdom, Hong Kong, Nigeria and Ghana, and it has been a truly rewarding adventure to immersively read through this creative spectrum of voices.”

The only debut on this year’s shortlist is the astonishing new Welsh talent Joshua Jones, who is in the running for his highly acclaimed short story collection Local Fires – a stunning series of multifaceted stories inspired by real people and real events that took place in his hometown of Llanelli, South Wales.

The sole poet in contention this year is Mary Jean Chan – who was previously shortlisted for the Prize with their debut Fleche in 2020 – and is now recognized for the collection Bright Fear, which fearlessly explores themes of identity, multilingualism and postcolonial legacy.

Three of the four novelists have also gained their second nomination for the Swansea University Dylan Thomas Prize: British-Ghanaian author Caleb Azumah Nelson is in contention for his second novel, Small Worlds, in which he travels from South London to Ghana and back again over the course of three summers to tell an intimate father-son story exploring the worlds we build for ourselves; Nigerian novelist Ayòbámi Adébáyò is shortlisted for her dazzling story of modern Nigeria, A Spell of Good Things, and two families caught in the riptides of wealth, power, romantic obsession and political corruption; and US author Catherine Lacey is celebrated for the genre-bending Biography of X, a roaring epic and ambitious novel chronicling the life, times and secrets of a notorious artist.

Completing the shortlist is British novelist AK Blakemore, recognized for her darkly exuberant novel The Glutton, which – set to the backdrop of Revolutionary France – is based on the true story of a peasant turned freakshow attraction.

The 2024 shortlist was selected by a judging panel chaired by writer and co-director of the Jaipur Literature Festival, Namita Gokhale, alongside author and lecturer in Creative Writing at Swansea University, Jon Gower, winner of the Rooney Prize for Irish Literature in 2022 and Assistant Professor at Trinity College Dublin, Seán Hewitt, former BBC Gulf Correspondent and author of Telling Tales: An Oral History of Dubai, Julia Wheeler, and interdisciplinary artist and author of Keeping the House, Tice Cin.

The winner of the Swansea University Dylan Thomas Prize 2024 will be revealed at a ceremony held in Swansea on 16 May, following International Dylan Thomas Day on 14 May.

Previous winners include Arinze Ifeakandu, Patricia Lockwood, Max Porter, Raven Leilani, Bryan Washington, Guy Gunaratne, and Kayo Chingonyi.

0 notes

Text

Why Did More Than 1,000 People Die After Police Subdued Them With Force That Isn’t Meant To Kill?

— In Partnership With: Associated Press (AP)

— March 28, 2024 | Frontline | NOBA — PBS

— By Reese Dunklin | Ryan J. Foley | Jeff Martin | Jennifer McDermott | Holbrook Mohr | John Seewer

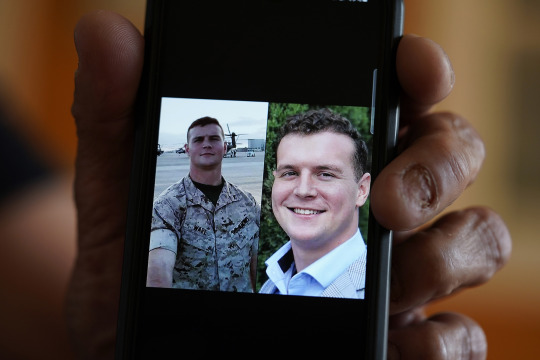

This combination of photos shows, top row from left, Anthony Timpa, Austin Hunter Turner, Carl Grant, Damien Alvarado, Delbert McNiel and Demetrio Jackson; second row from left, Drew Edwards, Evan Terhune, Giovani Berne, Glenn Ybanez, Ivan Gutzalenko and Mario Clark; bottom row from left, Michael Guillory, Robbin McNeely, Seth Lucas, Steven Bradley Beasley, Taylor Ware and Terrell "Al" Clark. Each died after separate encounters with police in which officers used force that is not supposed to be deadly. (AP Photo)

Carl Grant, a Vietnam veteran with dementia, wandered out of a hospital room to charge a cellphone he imagined he had. When he wouldn’t sit still, the police officer escorting Grant body-slammed him, ricocheting the patient’s head off the floor.

Taylor Ware, a former Marine and aspiring college student, walked the grassy grounds of an interstate rest stop trying to shake the voices in his head. After Ware ran from an officer, he was attacked by a police dog, jolted by a stun gun, pinned on the ground and injected with a sedative.

And Donald Ivy Jr., a former three-sport athlete, left an ATM alone one night when officers sized him up as suspicious and tried to detain him. Ivy took off, and police tackled and shocked him with a stun gun, belted him with batons and held him facedown.

Each man was unarmed. Each was not a threat to public safety. And despite that, each died after police used a kind of force that is not supposed to be deadly — and can be much easier to hide than the blast of an officer’s gun.

Every day, police rely on common tactics that, unlike guns, are meant to stop people without killing them, such as physical holds, Tasers and body blows. But when misused, these tactics can still end in death — as happened with George Floyd in 2020, sparking a national reckoning over policing. And while that encounter was caught on video, capturing Floyd’s last words of “I can’t breathe,” many others throughout the United States have escaped notice.

Over a decade, more than 1,000 people died after police subdued them through means not intended to be lethal, an investigation led by The Associated Press found. In hundreds of cases, officers weren’t taught or didn’t follow best safety practices for physical force and weapons, creating a recipe for death.

This story is part of an ongoing investigation led by The Associated Press in collaboration with the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism programs and FRONTLINE (PBS). The investigation includes the Lethal Restraint interactive story, database and the documentary, Documenting Police Use Of Force, premiering April 30 on PBS.

These sorts of deadly encounters happened just about everywhere, according to an analysis of a database AP created. Big cities, suburbs and rural America. Red states and blue states. Restaurants, assisted-living centers and, most commonly, in or near the homes of those who died. The deceased came from all walks of life — a poet, a nurse, a saxophone player in a mariachi band, a truck driver, a sales director, a rodeo clown and even a few off-duty law enforcement officers.

Explore: Lethal Restraint

The toll, however, disproportionately fell on Black Americans like Grant and Ivy. Black people made up a third of those who died despite representing only 12% of the U.S. population. Others feeling the brunt were impaired by a medical, mental health or drug emergency, a group particularly susceptible to force even when lightly applied.

“We were robbed,” said Carl Grant’s sister, Kathy Jenkins, whose anger has not subsided four years later. “It’s like somebody went in your house and just took something, and you were violated.”

AP’s three-year investigation was done in collaboration with the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism programs at the University of Maryland and Arizona State University, and FRONTLINE (PBS). The AP and its partners focused on local police, sheriff’s deputies and other officers patrolling the streets or responding to dispatch calls. Reporters filed nearly 7,000 requests for government documents and body-camera footage, receiving more than 700 autopsy reports or death certificates, and uncovering video in at least four dozen cases that has never been published or widely distributed.

Medical officials cited law enforcement as causing or contributing to about half of the deaths. In many others, significant police force went unmentioned and drugs or preexisting health conditions were blamed instead.

Video in a few dozen cases showed some officers mocked people as they died, laughing or making comments such as “sweaty little hog,” “screaming like a little girl” and “lazy f—.” In other cases, officers expressed clear concern for the people they were subduing.

The federal government has struggled for years to count deaths following what police call “less-lethal force,” and the little information it collects is often kept from the public and highly incomplete at best. No more than a third of the cases the AP identified are listed in federal mortality data as involving law enforcement at all.

When force came, it could be sudden and extreme, the AP investigation found. Other times, the force was minimal, and yet the people nevertheless died, sometimes from a drug overdose or a combination of factors.

In about 30% of the cases, police were intervening to stop people who were injuring others or who posed a threat of danger. But roughly 25% of those who died were not harming anyone or, at most, were committing low-level infractions or causing minor disturbances, AP’s review of cases shows. The rest involved other nonviolent situations with people who, police said, were trying to resist arrest or flee.

A Texas man loitering outside a convenience store who resisted going to jail was shocked up to 11 times with a Taser and restrained facedown for nearly 22 minutes — more than twice as long as George Floyd, previously unreported video shows. After a California man turned silent during questioning, he was grabbed, dogpiled by seven officers, shocked five times with a Taser, wrapped in a restraint contraption and injected with a sedative by a medic despite complaining “I can’t breathe.” And a Michigan teen was speeding an all-terrain vehicle down a city street when a state trooper sent volts of excruciating electricity from a Taser through him, and he crashed.

In hundreds of cases, officers repeated errors that experts and trainers have spent years trying to eliminate — perhaps none more prevalent than how they held someone facedown in what is known as prone restraint.

Many policing experts agree that someone can stop breathing if pinned on their chest for too long or with too much weight, and the Department of Justice has issued warnings to that effect since 1995. But with no standard national rules, what police are taught is often left to the states and individual departments. In dozens of cases, officers disregarded people who told them they were struggling for air or even about to die, often uttering the words, “I can’t breathe.”

What followed deadly encounters revealed how the broader justice system frequently works to shield police from scrutiny, often leaving families to grieve without knowing what really happened.

Officers were usually cleared by their departments in internal investigations. Some had a history of violence and a few were involved in multiple restraint deaths. Local and state authorities that investigate deaths also withheld information and in some cases omitted potentially damaging details from reports.