#1984 band

Text

A (possibly) previously-unseen article about 1984

At least it's new to me :) Very interesting to see the band described as a "psychedelic" group, and there's some nice bits here from Brian and Tim too!

Originally printed in the 17 February 1967 issue of the Middlesex Chronicle. (Open in a new tab for better quality)

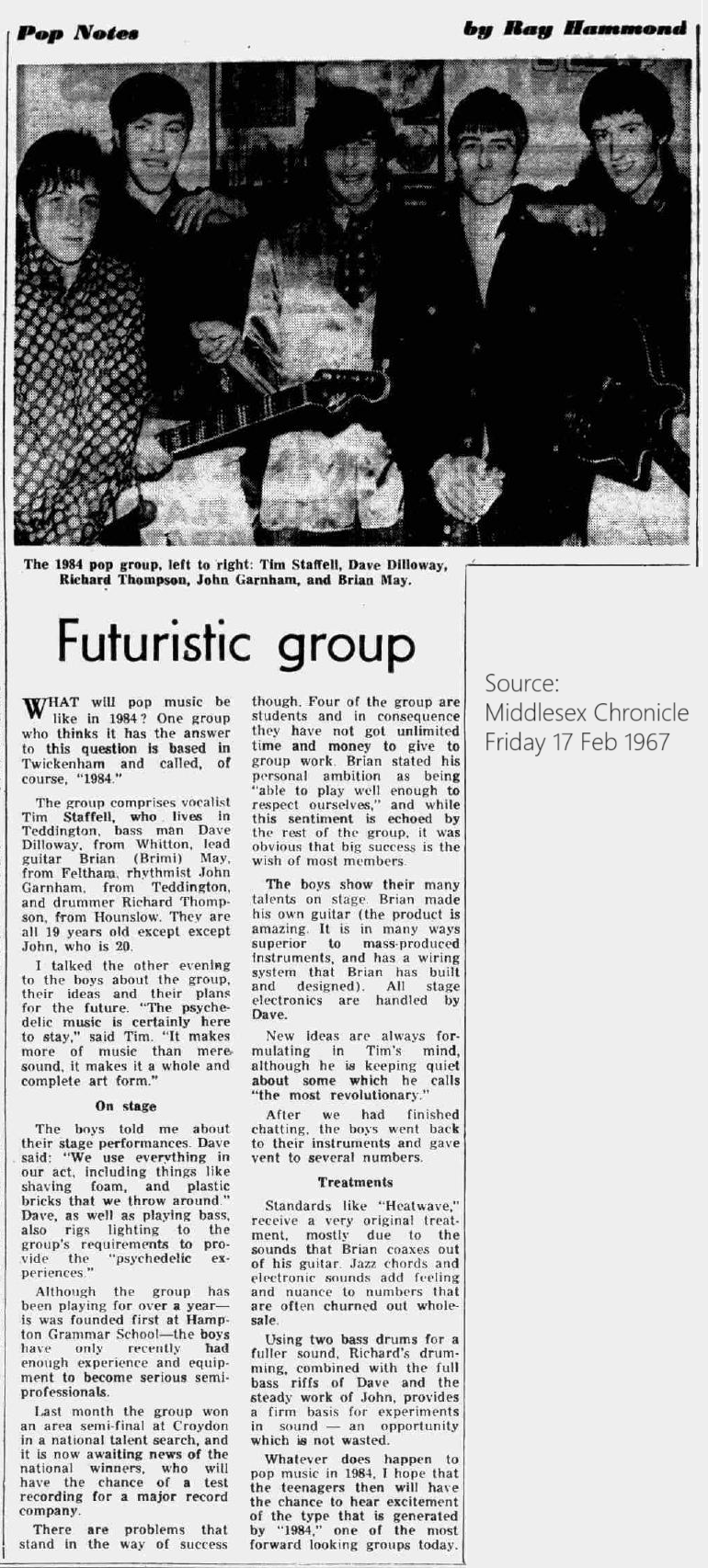

Pop Notes by Ray Hammond

(Image caption - The 1984 pop group, left to right: Tim Staffell, Dave Dilloway, Richard Thompson, John Garnham, and Brian May.)

Futuristic group

What will pop music be like in 1984? One group who thinks it has the answer to this question is based in Twickenham and called, of course, "1984".

The group comprises vocalist Tim Staffell, who lives in Teddington, bass man Dave Dilloway, from Whitton, lead guitar Brian (Brimi) May, from Feltham, rhythmist John Garnham, from Teddington, and drummer Richard Thompson, from Hounslow. They are all 19 years old except John, who is 20.

I talked the other evening to the boys about their group, their ideas and their plans for the future. "The psychedelic music is certainly here to stay," said Tim. "It makes more of music than mere sound, it makes it a whole and complete art form."

On stage

The boys told me about their stage performances. Dave said: "We use everything in our act, including things like shaving foam, and plastic bricks that we throw around." Dave, as well as playing bass, also rigs lighting to the group's requirements to provide the "psychedelic experiences".

Although the group have been playing for over a year - is [sic] was founded first at Hampton Grammar School - the boys have only recently had enough experience and equipment to become serious semi-professionals.

Last month the group won an area semi-final at Croydon in a national talent search, and it is now awaiting news of the national winners, who will have the chance of a test recording for a major record company.

There are problems that stand in the way of success though. Four of the group are students and in consequence they have not got unlimited time and money to give to group work. Brian stated his personal ambition as being "able to play well enough to respect ourselves," and while this sentiment is echoed by the rest of the group, it was obvious that big success is the wish of most members.

The boys show their many talents on stage. Brian made his own guitar (the product is amazing. It is in many ways superior to the mass-produced instruments, and has a wiring system that Brian has built and designed). All stage electronics are handled by Dave.

New ideas are always formulating in Tim's mind, although he is keeping quiet about some which he calls "the most revolutionary."

After we had finished chatting, the boys went back to their instruments and gave vent to several numbers.

Treatments

Standards like "Heatwave," receive a very original treatment, mostly due to the sounds that Brian coaxes out of his guitar. Jazz chords and electronic sounds add feeling and nuance to numbers that are often churned out wholesale.

Using two bass drums for a fuller sound, Richard's drumming, combined with the full bass riffs and the steady work of John, provides a firm basis for experiments in sound - an opportunity which is not wasted.

Whatever does happen to pop music in 1984, I hope that the teenagers then will have the chance to hear excitement of the type that is generated by "1984", one of the most forward looking groups today.

#brian may#brian harold may#tim staffell#queen#queen band#queen before queen#1984 band#text#long post //#brian#tim#stumbled across this wholly by accident while looking for articles about Merlin and Morgan#gonna go back and look for more 1984 specific articles now!

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

Brian May Brings Out the Stars

Steven Rosen, Guitar World, March 1984

The Queen guitarist brought together some heavies with Eddie Van Halen on guitar and Phil Chen on bass – for his Star Fleet Project.

BRIAN MAY emerges from one of the myriad cubicles housed within the Capitol Records tower, his six-foot-plus frame showing signs of fatigue due to overwork and a bout with the flu. He is in town finishing tracks for the upcoming Queen album (their twelfth), overseeing the release of his first jam-oriented solo record, coordinating a band video and frantically looking for a way to pick up his child at school. After much juggling and rearranging of schedules there appears to be a free moment and with that May settles his lanky frame into the divan, removes his clogs, and oh-so-calmly inquires "So, what would you like to talk about?"

And before word one is spoken there is a buzz on the lounge telephone. It is May's son informing him that he has arrived safely at home and, as if mentally checking off another responsibility taken care of, Brian settles even deeper into his seat and beams a wide smile.

May has much to smile about. Since the quartet's first album release in September, 1973, Queen has garnered eight gold albums (four of which went platinum), and recorded four singles reaching gold status (two of these went platinum). May, for the most part, has been the helmsman of the band's success. His unique approach to the multi-tracking and orchestrating of guitar parts has set the band apart from all others and the singularly distinctive sound he creates with a self-built guitar stamps Queen indelibly.

May's guitar architecture has been a process many years in the making. The son of a banjo playing father, Brian was taught a few chords by the elder May and after seeing a film of English rock idol Tommy Steele demanded a guitar of his own. It was a small-bodied instrument, owing to his then eight-year-old hands, and with great confusion he attempted to translate the four-string chords from the banjo to the six-string forms on the guitar.

"I never had any tuition on the guitar," explains May. "I did have piano lessons from about twelve to fifteen but I got really impatient and didn't like practicing. I gave it up, which I really regret now."

In grammar school he was involved in a series of bands playing the lunch hours and in fact he started a guitar club which seemed to attract most of the "eccentrics" on campus. These primal bands never performed in public because it went against Brian's fundamentally academic background, a philosophy highly espoused by both parents. The musical muse had already touched the young May and he further set the wheels in motion by electrifying that first acoustic guitar.

"I wound some wire around some magnets," describes May, whose penchant for electronics and construction would later lead him to design his own guitar, "and I plugged that into a record player and that was my electric guitar. It was pretty bad but it's amazing how much you can learn from something as simple as that. You get so involved." He later built an instrument of his own. "My father and I set about it and came up with different designs and finally built it. Originally, I designed the pickups but I ditched them. And although they had a good sound they didn't have a uniform enough feel on top. So I threw them out and put Burns pickups which were commercially available at the time. And that's what I still use. And I fill them up with this epoxy to stop them from being microphonic. Apart from that they're standard."

The guitar – dubbed The Red Fireplace (due to its brickish color) by the Queen members – had a number of peculiarities allowing May to play on it in a fashion denied by other instruments. The tremolo assembly is a far-reaching unit designed to lower the bottom string over an octave. In an age where Floyd Rose and Kahler vibrato pieces are common hardware on most Stratocaster-influenced instruments, this octave-lowering ability seems inconsequential. However, May designed this well over ten years ago and in that period it did have special properties. The guitarist does look at it merely as an effect and has not integrated it into his style in the fashion of someone like Edward Van Halen.

"I like to do airplane noises and crap like that," chides May. "Any kind of cheap gimmick."

The guitar, he admits, is not an easy one to play. Other musicians have strapped on the instrument and while they were impressed with the concept, became depressed by the function. The switches – all bought stock from the hardware store – are positioned in strange fashion and even the playability left most other artists dumbfounded. The neck is fashioned from a piece of old mahogany removed from a fireplace and is treated with several coats of clear finish which gives the fretboard a plastic feel. The main stress points of the body (where the neck is attached to the body; the bridge attachment, etc.) are built from oak while several other types of softwood permeate the main body shell. A semi-acoustic body (no f-holes but an abundance of hollow areas) creates a very live sound and this, too, has proved bothersome to other players in attempting to eliminate feedback. All in all, the instrument is tailored strictly for May's needs.

May's needs live are quite far-reaching. Because he must duplicate – or attempt to duplicate – the tangle of guitar parts liberally sprinkled on virtually every Queen track, he has developed an amplifier setup linked to a series of echo units resulting in a veritable web of sound. In the earlier days of the band, the guitarist wheeled nine Vox AC-30's on stage but only two were actually used. Several other amplifiers were used to house the echo signal (supplied by a modified Echoplex) and in May's own words, this is how the system ran:

"I basically used two amps for the guitar and an Echoplex which was specially extended so I could get long delays. I modified that myself. The modification was to put in a long rail instead of a short one and to turn the feedback back to zero so it's just a single repeat. And the delay comes back into another two (amplifiers) and yet another delay which goes into another two. At the most there are six working at one time."

Most recently he has found that digital units are more technically capable of handling these echo chores and he also realized their durability was far greater than the rather moody – and primitive – Echoplexes. He now makes use of a Digital Recorder because it features the facility of setting time by hitting buttons rather than turning a knob. This frees him to set a rhythm, press once and press again, and lock in the time of the repeat in a single motion.

The only other effect used in a live setting is a self-made one-stage preamp booster producing more signal and increasing the lead gain. By May's standards it is the "crudest" preamp in existence and only offers a gain of about 10 and a very slight bass cut.

May used an abbreviated version of this same setup when he recently and informally jammed with Edward Van Halen; Phil Chen (former bassist with Rod Stewart and Jeff Beck); Alan Gratzer (drummer for REQ Speedwagon); and Fred Mandel (former keyboardist with Alice Cooper and auxiliary player with Queen), in Los Angeles' Record Plant studios. The event took place on April 21-22 of last year when May was in Los Angeles biding time between Queen projects. A long-time friend of Van Halen, May gave Edward a call, assembled the other musicians and brought them together for two days of simple jamming and playing. What resulted was a mini-album (three tracks) titled Brian May & Friends: Star Fleet Project, produced by May and self-described as "A relaxed set of people just laying back and enjoying the fresh inspiration of each other's playing."

This shot of new blood, as it were, was an injection the guitarist sorely needed. Queen had just completed a tour of Japan that previous November and for virtually five months the group had not spoken to each other.

"I realized a big gap in my life was not playing with other musicians. I wanted to get out and find out what it was like to do that. I had almost never done it. We've never been into the superstar thing of people guesting on the albums. In this case we really needed it because we got sorely fed up with each other. We decided we couldn't stand the sight of each other for a few months and we had to take a break. And we did. So we needed that new energy. Roger went out and did another solo album and Freddie did some stuff with various people, including Michael Jackson, and John did some playing with other people and this was my thing. I produced a group called Heavy Petting, played on a few sessions and did this thing. I still think that Queen is stronger than any of its parts; that's why there's still a band called Queen."

On the album Brian uses his array of Vox AC-30's along with The Red Fireplace and while the album is completely live (including May's vocals on an old composition entitled 'Let Me Out') the guitarist's sound is unmistakably present. Because of the live setting May is placed in a rather naked situation without benefit of overdub or second take. He does manage to tear off some stinging blues licks in 'Blues Breaker', a twelve-bar jam dedicated one of May's main influences, Eric Clapton.

"I was a huge Clapton fan," acknowledges May. "I was very, very impressed with Cream. I saw one of their very first shows at Eel Pie Island [an early English stamping ground for many of the then-emerging British bands]. It was obviously an adventure for them at that point. It was really electric and they were all feeling each other out. There was 'Clapton is God' scribbled on all the walls in those days."

Hence the dedication to Clapton on the May solo album. So strong was this attraction that one of Brian's early bands (Smile) covered several Cream compositions and the band itself comprised a guitar, bass and drums setup. Smile was composed of May on guitar, Tim Staffell on vocals and Roger Taylor on drums, and even at this early point the guitarist, a bachelor of science in physics, was experimenting with the guitar orchestration which would come to full fruition several years later on the Queen II album.

"The second album [Queen II] was much different. Then we had a chance to do with the studio all the things we wanted to do. The multi-part guitars and all that. 'Procession' is a completely guitar-orchestrated thing but when the song ['Father to Son'] comes in and you expect just the crunch of the guitar, there's awash of harmony guitars behind. I always wanted to do that and that fulfilled a dream. I wanted to get that on record. I was very upset because I heard Mike Oldfield was doing guitar orchestra things and I wouldn't let myself listen to it. Because I was afraid he was doing what I always wanted to do first. But it turned out to be very different. But that sort of stated what I was into. And when Queen II came out it really didn't connect with a lot of people. A lot of people thought at that time we'd already forsaken rock music. It just didn't relate in their head and they said 'Why don't you play things like "Liar" and "Keep Yourself Alive" which were on the first album. And we said, 'Give it another listen, it's all there, the hipness is there but it's all layered. And it's a new approach.' But nowadays people say Why don't you play like Queen II?' [laughter] A lot of our real close fans think like that. And I still like that album a lot. It's not perfect, it has the imperfections of youth and the excesses of youth, but boy, I think that's our biggest single step ever."

While there are flaws – Brian's parts on several tracks are painfully obvious and highly undramatic (particularly on 'Procession') and the quality of sound on a few of the solos ('Father to Son' has an instrumental passage which is both gritty and metallic) is embarrassing – it is the foundation for the mesmerizing May sound to come. Part of this deficiency in quality is owing to the album's sixteen-track format.

From the beginning, though, May had a vision in his approach to the composition of guitar parts. Part of Queen's stance was the denial of keyboards or other electronic equipment as embellishment to sound (each album was tagged with a "no synthesizers!" warning) and not until The Game did they include any instrument of this type. May saw the guitar as a far more human musical device than the cold steel sounds being generated by an ever-increasing numbers of synthesizers. He felt that every guitar part should embody the same tension and emotion as the main line.

"The guitar for me is an emotional thing and you consciously play it, you consciously mark out the notes and squeeze the string. But there's sort of an unconscious thing there too and the emotion comes from that. There are things going in there which you almost don't realize you're putting in. That's the thing about the guitar, it has this tension and this real emotion. And I wanted the orchestra behind the guitar, every part to have that tension and emotion in it. And that's when I thought you would get the maximum impact and effect. So I just didn't want someone hitting a chord on a keyboard and synthesizers were already beginning to be around and most of the synthesizers at that time were very cold and had no emotion. I wanted it all to be guitars and so that's why I did it. On every part I was out there and pulling everything into it I could. All the emotion and bending just where I thought it should be bent.

"And the thing about a lot of guitar harmonies that people still don't realize is that they shouldn't be parallel any more than vocal harmonies should be parallel. That's not the way to get the real feeling into it. They should do all this crossing over and little discords and all this weaving in and out. Just the same way people build up orchestral scores."

To further tattoo the May sound, the guitarist early on discarded conventional picks (heavy) for an English sixpence, a coin roughly the diameter of an American nickel but with serrated edges. May likes the flexibility of the attack to originate from the fingers and not the pick and he has found that by positioning the coin in a sideways fashion one can obtain a smooth attack owing to the basic malleability of the metal. Angling the pick results in a very raspy and metallic tone due to the serrated edges.

"I find it very sensitive. My fingers are just about touching the strings and you can feel everything that goes on between the string and your finger."

May went on to further develop this layered guitar technique on such songs as 'Killer Queen' (unique in that the three-part harmonized guitar had each line beginning on a different bar), 'Another One Bites the Dust', 'Bohemian Rhapsody', 'Rock It (Prime Jive)' and a list with too many entries to mention. Aside from the Star Fleet Project album, May has been working doggedly on a new Queen album scheduled for release about now and tentatively titled The Works. It will undoubtedly feature May in new and exciting situations and while the band has loosened its stranglehold on the application of synthesizers, Brian's description of the album as "heavy" is an assurance that his guitar will be the predominant instrument.

"I see it (The Works) as being a lot closer to the middle period than the last three or four albums. A lot closer to A Night at the Opera and News of the World and a little bit like The Game. But some of the writing is the next step beyond, it's not going back in time. Because we've integrated some of the modern technologies. But we haven't gone totally toward machine music because the fact is we don't like it.

"Everyone thought we had this huge monster plan, the Queen Machine, but it's an illusion. What happened was we followed our noses and we were lucky enough to find an audience who went along with us. It's as simple as that. We're very fortunate."

Retrieved from rocksbackpages.com

#interview#article#queen band#brian may#bri#1984#guitar world#star fleet project#queen before queen#1984 band#bri on red

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Depeche Mode (1984)

#depeche mode#martin gore#alan wilder#dave gahan#andy fletcher#80s bands#80s music#new wave#1980s#1984

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Other people: Who's your favourite band?

Me: *shows them this photo*

#freddie mercury#brian may#roger taylor#john deacon#roger meddows taylor#queen#queen band#i want to break free#i want to break free 1984

364 notes

·

View notes

Text

April 12th, 1985 - Queen Story!

Auckland, New Zealand, Queen during an interview the day before the concert

'Works!' Tour

#works tour#works tour 1984 1985#1985#zanzibar#legend#queen#brian may#john deacon#freddiebulsara#london#queen band#roger taylor#freddie mercury#new zeland#interview#auckland

132 notes

·

View notes

Text

Steven Patrick Morrissey of ‘The Smiths’ on stage at De Montfort Hall (1984)

#steven patrick morrissey#morrissey#the smiths#celebs#aesthetic#lovecore#1984#80s#80s icons#de montfort hall#leicester#uk#united kingdom#bands#punk#music#music hall of fame

321 notes

·

View notes

Text

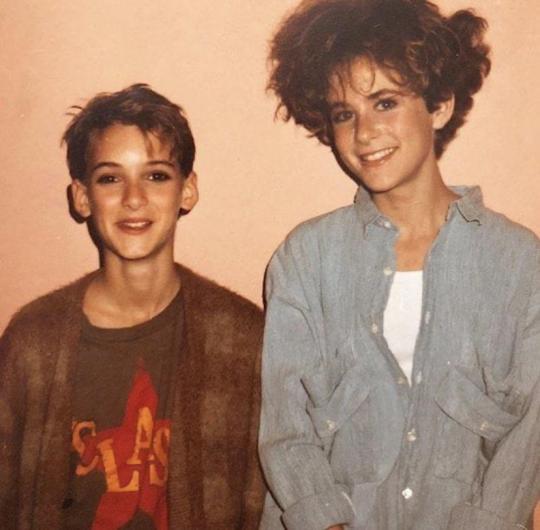

13-year old Winona Ryder (next to Allison Hart, another young actress of the mid-'80s) sporting a Clash t-shirt during her first movie audition back in 1984. According to the Reddit thread this was found on, the movie was Desert Bloom and she didn’t get the role but her audition tape made its way to an agency which led her to be cast in her first film Lucas.

Ryder has explained how she was considered 'different' during her high school years, when she used to sport a boy-ish short haircut and dress in menswear -which actually resulted in her getting horribly harassed and bullied at school: "…people thought I was a boy. At the time, I was obsessed with Bugsy Malone but also very into the Clash and the Replacements. I believe my friend cut my hair, and I remember reading somewhere that if you mixed beer and egg whites and put it in your hair, you could get it spiky like that."

(via & via)

111 notes

·

View notes

Text

106 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pretty❤️

#mine#sherlock holmes#granada holmes#granada sherlock#sherlock holmes 1984#the speckled band#the adventures of sherlock holmes#jeremy brett#brett holmes

147 notes

·

View notes

Text

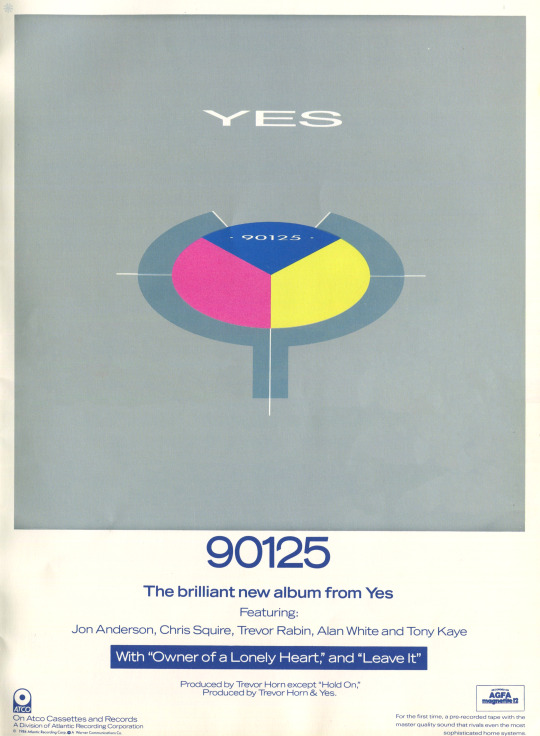

1984 Yes 90125 advertisement

From the 1984 Yes 90125 Tourbook

#Yes band#Jon Anderson#Chris Squire#Trevor Rabin#Tony Kaye#Alan White#vintage ad#prog rock#80's music#80's#1984#my scans

169 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Goodbye, and good luck, and believe me to be, my dear fellow,

very sincerely yours.”

#granada holmes#the final problem#the final problem 1985#the norwood builder#the resident patient#the speckled band#sherlock holmes#jeremy brett#sherlock holmes granada#sherlock holmes 1984#jeremy brett holmes#john watson#dr john watson#acd holmes#acd john watson#acd#acd watson#acd sherlock#acd sherlock holmes#acd johnlock#Johnlock#h/w#david burke watson#david burke#FINA#granada holmes gifset#sherlock holmes gifset#my gifset#my gifs#victorian husbands

717 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The Speckled Band" train scene from "The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes" with Jeremy Brett and David Burke (Granada, 1984)

#second one is like theyre on a seesaw#granada#sherlock holmes#the adventures of sherlock holmes#spec#the speckled band#holmes#granada holmes#granada sherlock holmes#jeremy brett#david burke#1984#gif set#hes wearing The Hat etc#gifset

153 notes

·

View notes

Text

Brian May

John Tobler, Stuart Grundy, The Guitar Greats (BBC Books), 1983

AT THE START of the 1980s, the rock band which was generally accepted, if not as the most popular group in the world, then as one of the top half dozen, was Queen.

The conventional record markets were comprehensively conquered at the end of the previous decade, while the group had effectively opened the door for rock music in South America – at one point, Queen were not only top of the charts in Argentina, but allegedly occupied the top ten positions in the hit parade. To single out one member of the quartet as particularly responsible for this remarkable popularity would be invidious – vocalist Freddie Mercury is the obvious focal point, but the musical heart of the band is undoubtedly Brian May, certainly one of the most innovative British guitar players of the rock era, and equally important in view of the stance of many of his peers, a modest, unassuming and immensely likable person, from whom many could learn...

Brian was born in Twickenham, Middlesex, on 19 July 1947. His father was an electronics engineer working on secret military projects for the Ministry of Defence, and this interest communicated itself to Brian, who nevertheless claims to lack his father's instinctive abilities relating to electronics, although he will admit to being well versed in the theory of the subject. More to the point, Brian's father was and is interested in music, and "a pretty good pianist. He taught me to play ukelele-banjo in the style of George Formby – it's a pretty good instrument that's tuned the same way as a ukelele, but has the same sort of sound vellum as a banjo, and from the chords I learnt on that, I taught myself the guitar."

Brian acquired his first guitar at around the age of seven. "It was a very cheap acoustic Spanish type guitar with steel strings, and was much too big for me when I got it. I can remember being dwarfed by this thing, getting it in bed on my birthday morning, and I thought it was very shiny and new and exciting. The strings were a long way off the fingerboard, and I thought for a long time about whether I should try to modify it, to make it easier to play, because I thought I might ruin it, but eventually I did carve down the bridge, and later, I put a pick-up on it, which my father and I made out of some button magnets with a coil wound round – it worked as well! We plugged it into a radio, into the auxiliary input, and it sounded pretty good, with a very sharp, penetrating clear sound, which I can't really get now.

"I found it quite easy to pick up playing the guitar – I was taking piano lessons at the time, which I never really enjoyed, because it was a chore to do the requisite half hour piano practice, and I always ended up banging the piano and swearing and walking away in disgust, whereas I always went to the guitar for pleasure, which is why, I suppose, my guitar playing progressed faster." And his early influences? "Lonnie Donegan, Tommy Steele, and the guy who played on the Rick Nelson records, James Burton. Soon after that, the Shadows came along, and they were a big influence, although I was always a bit snobby, like all the people at my school – we thought that somehow the Shadows were beneath us, because we could play better or faster or something, which was definitely a mistaken opinion. I was very keen on the Ventures, probably partly because of the American mystique – the Ventures were cool, but the Shadows weren't – but now I think Hank Marvin had the edge, although some of those Ventures things were very good, and very hard to play."

One of the legendary items for which Brian is famed is that during his teenage years, and with the help of his father, he built his own guitar. "We didn't really have the money to buy a proper guitar, and my school friends had things like Hofner Futuramas or Coloramas, and later a couple had Gibsons, which we couldn't afford, so we decided to make one. I'd played other people's, so I knew roughly what I wanted, and I had some theories about what sort of properties it should have – I wanted a cambered fingerboard which was very close and fast, and I wanted three pick-ups, and to be able to vary the combinations of the pick-ups, which I felt was very limited on the guitars that I'd tried, where you either had them all on or all off, and that was about it. I think I'd just seen Jeff Beck at the time I was building it, so I wanted to be able to make it feed back like he did, because I was amazed at all this violin sound stuff, which I thought was obviously going to be the direction in which guitar playing was going – I thought if you could get a really good sustain which was foolproof, didn't just come out now and again, and was actually controllable, you'd almost have a new instrument, something really like a violin, where you can put some expression into the notes. So I had this idea of putting acoustic pockets into the guitar, because I realised it had to feed back through the body of the guitar and the strings, rather than through the pick-ups, which gives a microphone whistle effect – most of the guitars I'd played would just whistle if you held them near the amplifiers. I also wanted a good tremolo, which returned to its zero position, and didn't go flat once you'd pushed it down a couple of times, so we had to find a tremolo design which didn't have much friction in it – my dad and I did lots of tests with a sort of mock up, a piece of wood with some strings stretched over it, to see what sort of strains were involved. We were very scientific about it, and measured the stresses of the strings – and we designed one tremolo, a sort of cylinder device, which didn't work very well, because here was too much friction, so we ditched that, and went with the knife edge design, which I don't think had been done at that time, although there are some designs like that now. So we had an actual knife edge, which was a mild steel plate with a little "V" groove in it, and into the groove fits a plate which has a point, and the plate which holds the strings can rock backwards and forwards. We did the thing properly and case-hardened the ridge so that it would almost never wear out, which it actually never has, although I've used it constantly for the last ten years.

"It's very hard for most people to play, but as I grew up with it, I find it easy, and in fact, it's the only thing I can play properly, and I'm still using it. The neck was actually part of a fireplace which was just lying around in a friend's house, and the friend was a woodworking man – it was a lovely piece of mahogany with dead straight grain, which had probably been lying in his house for fifty years, and he said he got it from his father."

Brian's early life was spent in the suburb of Feltham, not far from London Airport, and whether coincidentally or otherwise, the schools he attended had also educated several other notable musicians – Jimmy Page, Brian learnt, had attended the same infant's school in Feltham, while two of the Yardbirds, Jim McCarty and Paul Samwell-Smith, went to Brian's secondary school, Hampton Grammar School, which as a result became a fairly well-known nursery for rock musicians including Brian's own first group. Additionally, although neither of them knew it at the time, Freddie Mercury lived only a few hundred yards away..."I didn't know – obviously, we went to different schools, and I didn't know who he was until we were at college and he was friendly with Tim Staffell, who went to the same art college as Freddie, in Ealing." Staffell, in fact, was also a member of Brian's first group, 1984.

"1984 was purely an amateur band, formed at school, although perhaps at the end we once got fifteen quid or something. We never really played anything significant in the way of original material – it was a strange mixture of cover versions, some pop, Everly Brothers, Buddy Holly & the Crickets, some James Brown, 'Knock On Wood' by Eddie Floyd, all the things which people wanted to hear at the time. This was about the time that the Stones were emerging, and later on we did Stones and Yardbirds things...I was in the band for a couple of years, although it wasn't very serious – we did a few dances and things, but I was never happy about it. I left because I wanted to do something where we wrote our own material. I just thought that was necessary to progress, and that was the time I met Roger (Taylor, drummer with Queen). I advertised on a notice board at college for a drummer, because by this time, Cream and Jimi Hendrix were around, and I wanted a drummer who could handle that sort of stuff, and Roger was easily capable of it. Tim Staffell, who had been in 1984, was our singer, and we formed this group called Smile, which was semi-pro – we travelled around the country a fair bit, as far as Cornwall, and Liverpool, and although we did well in some places, we never felt we were getting anywhere, because if you don't have a record out, people tend to forget who you are very quickly, even if they like you on the night. We tried for a long time, and wrote a lot of material, a little of which was carried over into Queen, and we also did a lot of improvising. We did get a record contract – we got very big time, thinking that was it, and we signed with Mercury Records of England, who were just setting up, headed by Lou Reisner, as an English branch of American Mercury, and we recorded about half-a-dozen tracks for them, but they didn't release any of them in Britain. They did put out a single in America, but it didn't do anything. It was a very bad experience, and we also had a bad management experience as well at that time, and it was all very disillusioning."

It was also at this time that Brian first came across Freddie Mercury. "He was a friend of Tim's and came along to a lot of our gigs, and offered suggestions in a way that couldn't be refused! Like 'Why are you wasting your time doing this and that? You should do more original material, and be more demonstrative in the way you put your music across. It takes more than that, and you should put it across with more force – if I was your singer, that's what I'd be doing.' At that time, he hadn't really done any singing, and we didn't know he could – we thought he was just a theoretical rock musician. He was a big Hendrix fan, and he played me all these little bits of Hendrix that weren't obviously audible – he was really a fanatic."

At Imperial College in London Brian studied for an Honours Degree. "It was about 50 per cent mathematics, with a little bit of electronics and a lot of pure physics. I intended to be an astronomer, and I attended the infra-red astronomy department of Imperial, although I didn't actually do infra-red astronomy – what I did was optical interferometry, looking at dust in the solar system. I did that for four years with the idea of getting a Ph.D., but I never finished writing it up – I was about two pages away from finishing, but I never got the final conclusions done, although we did publish two papers with the results and a brief interpretation of them, but there was going to be a third paper which unfortunately never got done. It all got beyond me, and I ran out of money in the fourth year, because the grant only lasted for three years, so I decided to teach in the daytime to make the money to support myself and be able to keep on processing the results. I did that for a while, and worked at night doing the calculations for the results, but that got way too much – anyone who's taught knows that teaching's a full time job. I taught at a comprehensive in Stockwell, and I found that I had to prepare for an hour or more each night to keep on top, and I just became tired, so something had to go, and also at that time was the beginnings of Queen. We were rehearsing, considering whether we'd go into it full time, and around the time we were offered the chance to sign a contract, I decided to forget the academic side at least for a while to see if Queen could become a proper group."

After the inevitable finish of Smile, whose sole single coupled 'Earth' with 'Step On Me', came the eventual transition from that group into Queen. "Smile completely broke up, and we gave up, and I think we all thought that we wouldn't try again after that, but Tim was the first to get back into music, and went off with a group run by a folk singer named Jonathan Kelly, who was trying to get into more rock-oriented material."

With the departure of Staffell, Queen began to take shape, its initial members apart from Brian being drummer Roger Taylor and Freddie Mercury. "Freddie was the driving force for getting us back together – he told us we could do it, and said he didn't want to play useless gigs where no one listened, and that we would have to rehearse and get a stage act together – he was very keen for it to be an actual act – and we started again, taking a couple of songs from Smile and a couple of songs from groups he'd been in, like a band called Wreckage from which we stole bits that went into 'Liar' and a couple of other songs, and we set about it in a serious manner. We'd rehearse three or four nights a week in places like lecture theatres, and we managed to scrape together some equipment."

Despite a level of musical expertise and originality which, in retrospect, was plainly evident, Queen did not enjoy the smoothest of rides in Britain at the genesis of their career, largely due to their choice of name – at a time when glitter rock was in vogue, the name "Queen" seemed rather too obviously an attempt to cash in on someone else's fame...

"I think the name mainly came from Freddie, and I don't think I was too keen on it at the beginning – you toss around hundreds of names, and of all of them, that was the one that stuck, and in a way, the one which got the most argument. I'm not sure that Roger was that keen to begin with, either, but we felt it seemed to stick in the mind, and had a certain mystique and grandeur about it which we thought might catch people's imagination, so that was the one we kept."

It will not have escaped the attention of those familiar with Queen's work that thus far, only three names have been mentioned as members of Queen. "We did have a bass player, and we went through a few of them, but either the personality or the musical ability didn't fit, and it was a while before we found John, through some friends." The first Queen LP refers to John Deacon as "Deacon John" – what's that about? "We used to call him that, and it appeared like that on the album, but after that, he objected to it, and said he wanted to be called John Deacon. I don't really know why we called him Deacon John in the first place – just one of those silly things."

A discussion of Brian's guitar influences at the time of Queen's formation revealed some familiar names – Eric Clapton, Jeff Beck and Jimi Hendrix. "When Hendrix came along, it just seemed to be such a great opening of the doors – he seemed to push it along so fast in such a short time. When I first heard 'Stone Free', which was the B-side of 'Hey Joe', there was this solo I couldn't believe, and as a guitarist, I've a reluctance to admit another guitarist's as good as he is but there's still nobody who can approach him for inventiveness, technique, pure sound and style and everything.

One unique feature of Brian May's technique is the fact that he plays not with any kind of conventional plectrum but with a coin, in fact a pre-decimalisation sixpence, of which he has a large supply. "It's not crucial, because I can play with a new penny, or an American dime. I use coins because they're not flexible – I think you get more control if all the flexing is due to the movement in your fingers. You get better contact with the strings, and depending on how tightly you hold it, you have total control over how hard it's being played, and because of its round surface and the serration, by turning it different ways you can get different sounds, like a fairly soft sound, or a slightly grating sound on the beginning of the note which actually lends a bit of distinction to the notes, especially when you're using the guitar at high volume, as I generally do. Otherwise, the sounds tends to be very level and smoothed out."

Queen's early days were, perhaps predictably, nondescript in terms of progress until they were invited to "test" a new studio which had just been completed. "I did have one real contact, a guy called Terry who was working at the time for Pye Studios, but was moving to the new DeLane Lea studios, and he said they needed people in there to make some noise, because they were testing the separation between the three studios, and the reverberation times, and they wanted a group to do it and Roy Thomas Baker came to DeLane Lea, completely by accident, as far as I know, and said that he liked what we were doing very much, and I think it was through him recommending us to Trident that they finally gave us a contract."

The first Queen LP was made over a lengthy period at times when the recording studios owned by Trident were not booked by paying customers, which is not an ideal way for any band to make their first album – Brian confirmed that the group were less than happy about this arrangement, but added that since it was in the past, he felt it inappropriate to elaborate further on the subject.

At least a part of Queen had appeared on record shortly before any Queen product was released, in the shape of a single, 'I Can Hear Music'/'Goin' Back', credited to one Larry Lurex. "As I said, the album took ages and ages – two years in total, in the preparation, making and then trying to get the thing released – and meanwhile, Robin Cable, who we also knew in Trident Studios, was doing this thing which was a re-creation of the Phil Spector sound, and he was very keen for Freddie to be the vocalist. Once Freddie was in there, he suggested that it should have some of my guitar work in this instrumental space they'd left blank, after they'd tried to do it with synthesisers, but it didn't seem to be working out too well, so I did a solo, although I didn't play the acoustic guitars which are crashing through it, and they also used Roger to do some percussion overdubs, like the maraccas and tambourines, which is a part of the Phil Spector sound. I like that quite a lot, and I thought it was a good piece of work, and it was done before we'd finished our own LP, so it was put out under the name of Larry Lurex, which was a joke, but which unfortunately backfired, because a lot of people took exception to the fact that we seemed to be taking the mickey out of Gary Glitter, so a lot of people refused to play it because of that."

Even when the first Queen LP was finally completed, it was not immediately released. "After that, Trident had to go around all the record companies again to see what offers they could get for us, but unfortunately, they were selling us as part of a package of their production, which also included Eugene Wallace and Mark Ashton, and they wanted the package accepted as a whole. But suddenly, there was a move from EMI – Roy Featherstone sent us a telegram which asked us not to sign with anyone else until we'd talked to him, and he was very keen and he got us, and I think, in the end, he did sign the whole package of Mark Ashton and everything. But it had taken an awfully long time, partially because Trident had to do all the negotiations, as our hands were tied, and we actually put on the sleeve of the album that this was the result of three years work, because we were upset and felt that the record was old-fashioned by the time it came out. Lots of stuff had happened in the meantime particularly David Bowie and Roxy Music, who were our sort of generation, but who had already made it, and we felt that it would look like we were jumping on their bandwagon, whereas we'd actually had all that stuff in the can from a very long time before, and it was extremely frustrating."

In America, the story was a little different, as neither Bowie nor Roxy Music were as immediately successful as they had been in Britain. "We got a lot of FM radio play, and a lot of backing for that first album from people who played four or five tracks of it to death, and that gave us a really good grounding in America. We didn't tour in America, which was a shame, but we were just too busy doing other things at the time, and it's very much to the credit of Jack Nelson, who was brought in from America to manage us on Trident's behalf, and knew the American scene, that we toured America immediately after making our second album, supporting Mott the Hoople, and that was really one of the best things we ever did, and that was due to Jack."

Another item of interest on Queen's debut LP was a note on the sleeve proclaiming "No synthesizers", which was echoed on each new Queen album for several years. "The guitars were making some sounds which people might have thought were synthesizers – I was using pedals and the long sustain stuff; and harmony guitars in the background – and we did some John Peel sessions for the BBC, and a lot of people thought we used synthesisers, so we wanted to make sure people knew it was all guitars and voices, and that stuck with us for a long time. I think that for the first nine albums we made, there was never a synthesiser and never an orchestra, never any other player except us on the records."

While 'Keep Yourself Alive' was the outstanding track for most on the first Queen LP, 'My Fairy King' seems to have been a foretaste of what would become one of the group's best known hits, 'Bohemian Rhapsody'. "Yes, I think that was the first step in that direction, the first time we'd really seen Freddie working at his full capacity. He's virtually a self-taught pianist, and he was making vast strides at the time, although we didn't have a piano on stage at that point, because it would have been impossible to fix up, and we didn't want an organ sound. So in the studio was the first chance Freddie had to do his piano things, and we actually got that sound of the piano and guitar working for the first time, which was very exciting, and 'My Fairy King' was the first of those sort of epics where there were lots of voice overdubs and harmonies, and a quite complicated structure, which Freddie got into, and that led to 'The March Of The Black Queen' on the second album which is very much in that idiom, and then 'Bohemian Rhapsody' later on."

1974 saw the second Queen LP, Queen II, released, which saw the first British breakthrough for the group. The track from that album which seems to most bear Brian May's mark is 'Father To Son', which seems in retrospect to betray elements of both the Who and Led Zeppelin. "They're probably in there somewhere, because they were among our favourite groups, but what we were trying to do differently from either of those groups was this sort of layered sound. The Who had the open chord guitar sound, and there's a bit of that in 'Father To Son' but our sound is more based around the overdriven guitar sound, which is used for the main bulk of the song, but I also wanted to do this business of building up textures behind the main melody lines. To me, Queen II was the sort of emotional music we'd always wanted to be able to play, although we couldn't play most of it onstage because it was too complicated, and so it was our first expedition into pure studio music. We were trying to push studio techniques to a new limit for rock groups, and we wore the tape literally to the point where you could see through it because we were doing so many overdubs. We were building up fifty piece choir type effects and loads of guitars to get this thick orchestra sound, and in a way, it was going over the top – it was fulfilling all our dreams, because we didn't have much opportunity for that on the first album, being stuck in at odd hours, and virtually reproducing what we could do on stage at that time, so the second album was an adventure into the world of what can be done and hasn't been done before, and in that sense it was over the top. We thought of it as almost baroque in some of the things we were doing, and in fact it went through our minds to call the album Over The Top."

While he is best known as a guitarist, Brian is also a notable songwriter, and it seemed appropriate to enquire about the lyrical inspiration of 'Father To Son'... "That was sort of a vision of things growing with the passage of time, not by overthrowing what's gone before, but by building on it – evolution as opposed to revolution, which is something I still believe in. So that was my little statement, although I don't know how much people actually get into lyrics."

The track from Queen II which first attracted attention in Britain was 'Seven Seas Of Rhye', which had also been included, in a very short version, on the first album. Roy Thomas Baker, who produced both the first two Queen albums, had suggested that 'Seven Seas...' was no better than 'Keep Yourself Alive', but had become a hit because it was featured on Top Of The Pops, whereas the earlier single had been less fortunate.

"The first version was just a little trailer, because the song wasn't actually finished then – the shape of things which might come, although it was very plain on the first album, with no vocals or orchestration. As to the Top Of The Pops thing, there's probably a lot of truth in that. And on 'Seven Seas Of Rhye' – the whole world happens in the first twenty seconds, and you've almost heard the whole song in that time. Great big swooping things, then the vocal launches straight in...maybe that had something to do with it, and it was a good, catchy record, but we were hot at the time, and that obviously helped."

Shortly after embarking on the American tour on which Queen supported Mott the Hoople, Brian was struck down with a serious case of hepatitis. "I really felt bad at having let the group down at such an important place, but there was nothing I could do about it. It was hepatitis, which I think you get sometimes when you're emotionally run down. And almost immediately after that, we were due to start recording the next album, Sheer Heart Attack, and I couldn't do much at the start. I seemed to recover, but then got ill again, and eventually, I couldn't eat anything and I was being sick all the time, which was sheer misery. They discovered that I'd had this ulcer business for fifteen years on and off, which had been aggravated by the hepatitis. So then I was stuck in hospital for a few weeks, and they did some stuff to me which was like a miracle, and it was like new life afterwards, because I thought I was dead. Being ill like that may even have been a good thing at the time, although it was pretty hellish going through it –I felt glad to be alive, and I became able to hold things in perspective more and not get so wound up and worried about them to make myself ill.

"With Sheer Heart Attack, it was very weird, because I was able to see the group from the outside, and was pretty excited by what I saw. We'd done a few things before I was ill, but when I came back, they'd done a load more, including a couple of backing tracks of songs by Freddie which I hadn't heard, like 'Flick Of The Wrist', which excited me and gave me a lot of inspiration to get back in there and do what I wanted to do. I also managed to do some writing – 'Now I'm Here' was done in that period, and came out quite easily, whereas I'd been wrestling with it before without getting anywhere. That song's sort of about experiences on the American tour, which really blew me away in more senses than one! I was bowled over, partly by the success we were having and partly by the amazing aura which surrounds rock music in America, which is hard to describe."

Another notable song from Sheer Heart Attack written by Brian is 'Brighton Rock'. "I like to think that showed how my style was evolving, particularly with the solo bit in the middle, which I'd been doing on the Mott the Hoople tour and has gradually expanded ever since, although I keep trying to throw it out, but it keeps creeping back in. That involved using the repeat device in time with an original guitar phrase, which I don't think had been done before that time. It's a very nice device to work with, because you can build up harmonies or cross rhythms, but it's not a multiple repeat like Hendrix or even the Shadows used, which is fairly indiscriminate, although it makes a nice noise, but just a single repeat which comes back, or sometimes a second repeat as well, so you can plan or experiment to produce a fugue type effect."

Roy Thomas Baker, who produced Sheer Heart Attack, has said that the album was designed to be more easily assimilable than its predecessor. "Yes, that's probably true, although we weren't going for hits, because we always thought of ourselves as an album group, but we did think that perhaps we'd dished up a bit too much for people to swallow on Queen II."

After the album was released, Queen embarked on their first trip to Japan which was a major occurrence. "Oh yes, that was a big thing for us. Suddenly we were stars – we'd had some success in England and America, but we hadn't had adulation and been adored, and suddenly, in Japan, we were pop stars in the same way as the Beatles or the Bay City Rollers, with people screaming at us, which was a big novelty, and we loved it and had a great time. The only drawback was that we were a sort of teenybop attraction, but it was some years ago, and when we go back to Japan now, we're lucky enough to have made a smooth transition to having a pretty normal rock audience in Japan of older people of both sexes, rather than just the little girls screaming. But it was an inspirational experience, and I think it brought out the acting ability in us, and made us a bit more extrovert on stage."

In the same period May received an offer from another group, Sparks, who were interested in his leaving Queen and joining them. "They thought that because I was ill, Queen was breaking up, which wasn't really happening, although things were obviously a bit shaky at the time. I got on very well with Ron and Russell Mael, and I still see them occasionally, but despite the fact that I quite like their music, I didn't feel it would be quite right. I also felt a loyalty to Queen and thought that we'd get our strength back in the end."

How does Brian feel his playing has developed during his years with the band? "I don't think I've progressed that much technically in terms of pure playing, and I could play almost everything I can play now when I was about sixteen. I sometimes think that's a bad thing, but I see it in lots of other people as well, Jeff Beck and Eric Clapton. You fairly quickly reach a stage when you're practising very intensely and where you can express most of what you want to play, and after that, I think, you become better as an all-round musician and your taste improves, but I don't think your technical ability gets that much better and you reach a plateau."

It must be, and has been, difficult for Queen to tour due to the enormous amount of amplification and lighting equipment they use on stage. "Yes, even in the beginning when we couldn't afford a light show, we used projector lamps for lights, and we just got through somehow, getting someone to drive us, or borrowing a bigger van – it was scraping through all the way. It's still a big problem organising everything, but we're very lucky in having some great people working for us, notably Gerry Stickells, who was Hendrix's road manager throughout his career, and is an amazing person who I'd say was the best tour manager in the world, without any doubt. He's able to get it together in any circumstances and organise everything, even in South America, where you have no help because people don't understand what you're trying to do. We can go anywhere and know that when we walk on stage for the sound check, it'll all be working, which is a wonderful feeling of security. We also have other people working for us in different capacities, because we now manage ourselves and in the end everybody leaves the decision to us, but we have Jim Beach, who negotiates with record companies, agents, and merchandising people, and Paul Prenter, who runs our day to day operation. It's not a big operation – people tend to think of the vast Queen machine swinging into action, but we only have four or five people actually working for us, and we pick up the rest when we go on tour, although there are certain people who we rely on getting, like Trip Khalaf, who's our permanent sound mixer, and James Devenney, our permanent monitor mixer – that's so crucial, and I think one of the most difficult jobs in the world, because it's equally important to have a good sound on stage as to get it good out front, and if either one's lacking, you do a bad show."

Between Sheer Heart Attack and their next LP, A Night At The Opera, a basic change occurred in Queen's operations when they left Trident and started the organisation described above.

It was perhaps no coincidence that Queen's producer, Roy Thomas Baker, also left Trident during this period, and ironically followed Queen to their next manager, John Reid, who also manages Elton John. "We went round and talked in person to a few managers, and it was quite an exciting time really, although depressing in some ways, because we felt very locked in. We thought if we could find someone who it was our idea to approach, then at least they'd be able to help us get out of our other situation, and we saw a lot of managers, all of whom had something useful to say, but John Reid seemed to be the only one we could all agree about – we liked his approach and the style of his operation, so we gave it to him, and told him to do the negotiating and get us out, and we'd go away to make the album. He did take the burden off our shoulders at that time, which was crucial, and allowed us to make that all important album.

"We later bought ourselves out of John Reid as well, but it was more out of a feeling that nothing was happening any more – it wasn't so much a conflict as a feeling that we weren't getting any further in the relationship, and the creative management thing wasn't there as much as it had been at the start. We obviously owe some of our success to both Trident and to John – Trident got us making records and hits, for instance – but the whole John Reid time was a period when we made very big strides."

A Night At The Opera was an extremely successful LP, perhaps largely due to the inclusion of the track which has become Queen's "signature tune", the epic 'Bohemian Rhapsody'. "That was really Freddie's baby from the beginning – he came in and knew exactly what he wanted. The backing track was done with just piano, bass and drums, with a few spaces for other things to go in, like the tic-tic-tic on the hi-hat to keep the time, and Freddie sang a guide vocal at the time, but he had all his harmonies written out, and it was really just a question of doing it. He even knew pretty much what he wanted in the way of guitar, although there's always a bit of freedom to do what I want on the guitar side, and I could do the solo as I wanted really, but it was very much Freddie's thing which was mapped out. It took a week just to do the vocals, and that was efficient working as well – we already had our methods well worked out, where the three of us would sing a line, then double or maybe treble track it. There were nine parts to some of those vocal pieces."

Brian was responsible for writing no less than three standout tracks on the album, 'The Prophet's Song', 'Good Company' and '39'. "'The Prophet's Song' had been around for quite a long time, and I finished the lyrics off when we were making this album. I don't know exactly what inspired the words, because I don't pretend to have any supernatural vision of any kind – it was really just my feelings, and I had a dream about some of it, which I put into the song, but that's not my usual inspiration for songwriting. I'm not a very prolific writer, and I can never just sit down and write a song – there has to be something there, and usually, I get a couple of lines of lyrics and melody together, and then the rest of it's really working very hard, searching the soul, to see what should be in there, but then some of the stuff I've done without taking it too seriously, I've been more pleased with it in the end.

"With 'Good Company', I indulged a little fetish of mine – all the things that sound like other instruments, like trumpets and clarinets, were done with guitar. To get the effect of the instruments, I was doing one note at a time with the pedal and building them up, so you can imagine how long it took. We experimented with mikes and various tiny amplifiers to get just the right sound, and I made a study of the kind of things those instruments could play to try to get that authentic flavour. It was a bit of fun, but a semi-serious piece of work because so much time went into it. '39' was different again, kind of a folky thing, close to skiffle, which probably comes from my Lonnie Donegan days. There was such a wide variety on those albums – Fred doing a really quite slushy ballad, then a heavy rock thing, then something else – and we were willing to try everything because we always wanted to expand our range.

"Recently, we've become more selective, I think, and we try to make albums which don't go in so many directions at once – for example, The Game album was really pruned, and the others refused to include a couple of things I wanted on, because they said they were too far outside the theme of the album, and that we should be trying to make a slightly more coherent album. '39' is a science fiction story I made up, it's a story about someone who goes away and leaves his family, and because of the time-dilation effect, where the people on earth have aged a lot more than he has when he returns, he's aged a year and they've aged a hundred years, so instead of coming back to his wife, he comes back to his daughter, in whom he can see his wife. I think I also had in mind a story by Herman Hesse, which is called "The River", I think, where a man leaves his hometown and travels a lot, then comes back and observes it from the other side of a river, and sees it in a completely different light because of his experiences. I felt a little like that about my home at the time, having been away and seen this vastly different world of rock music, which was totally different from the way I was brought up. People may not generally admit it, but I think when most people write songs, there's more than one level to them – they'll be about one thing on the surface, but underneath, they're probably trying, maybe even unconsciously, to say something about their own life, their own experience – and in nearly all my stuff, there's a personal feeling."

The 1976 Queen album, A Day At The Races, continued the Marx Brothers title fetish, but in the opinions of many, was somewhat less impressive than A Night At The Opera. "I wish in some ways that we had put the two albums out together, because the material for both of them was more or less written at the same time, and it corresponds to an almost exactly similar period in our development, so I regard the two albums as completely parallel, and the fact that one came out after the other is a shame, because it was looked on as a follow-up, whereas really it was sort of an extension of the first one."

The period after the release of A Day At The Races saw Queen retreating into a kind of cloistered privacy from which they rarely departed, especially to speak to the media. "This was imposed on us in a way – we had never really got on with the press and had a lot of enemies there, but by that time, just about everyone in the press was against us, and quite blatantly so. So our silence wasn't through choice, it was really having no one to talk to who was going to write anything which would be of any use to us, so we thought it best not to bother, although reluctantly, particularly in my case, because I like talking to people and I think there's always something to gain from it. I know it happens to everybody else as well, and it's a normal consequence of success in England – a lot of people resent your success, and a lot of people also resented Fred's demeanour on stage, interpreting it as a sort of arrogance in his private life, which he doesn't have. He's a performer first, and off stage, he's pretty shy on the whole."

The mention of Mercury was appropriate at this point, as the 1977 Queen LP, News Of The World, saw Freddie less well-represented than usual as far as songwriting went, which led to some of the same press people to whom the group weren't talking to assume that a split of some kind in the group might be imminent. "There was nothing like that really, except that possibly Fred was then getting interested in other things, and a bit bored with being in the studio, because we did studios to death with the previous two albums, when we'd be in there for months on end, just working away, although we weren't particularly inefficient, it was just that there was a lot to be done. We all felt we'd done enough of that for the time being, and wanted to get back to basics and do something simpler, but Fred got to the point where he could hardly stand being in a studio, and he'd want to do his bit and get out."

Of the tracks on the record written by Brian, perhaps the most interesting is 'Sleeping On The Sidewalk', which evokes memories of the British R&B boom of the 1960s. "That was the quickest song I've ever written – I just wrote it down, and I'm quite pleased with it as well, because it's not highly subtle, but it leaves me with a good feeling. It was the sort of thing any guitarist who had played a bit of blues would do, and I could very well have had Eric Clapton in the back of my mind...It was a one take thing as well, although I messed about with the take a lot, chopped it around and rearranged it, but we basically used that first take, so it has a kind of sloppy feel, but that works with the song.

'It's Late', on the same LP, comes across as a typical Queen song. "There's not much I can say to that – I suppose that's as close to typical Queen as you can get, and there's a kind of style in there, which I've often thought about, which is somewhere between my kind of thing on 'It's Late', and one of Freddie's, something like 'We Are The Champions'. It's so easy for us to do, and we can slip into it almost without thinking, on stage and on record. Once Freddie starts playing E flat and A flat on the piano, which he very often does, it has a particular sound, and those are very strange keys for a guitarist to play in, so the songs being in those keys actually produces something different out of me, but as soon as that's happening, that formula's there, and we can do that sort of Queen sound all night and all day."

The release of News Of The World more or less coincided with the rise of punk rock in general, and the Sex Pistols in particular, leading to Queen's fall from popularity being freely predicted in the media.

"We didn't really feel threatened, because we saw that it was still the same people attracting large crowds, like Genesis, Zeppelin and the Who, and even us, and we knew that the man in the street was still aware that music could have different forms, and that it didn't have to be one thing at a time, which is what I don't like about England, if you like. Going back to punk, that era took a lot of backward steps, like the idea that it was bad to put on a show because that wasn't musically valid, but the end result was good, as a sort of clearing out system, and it was a good time for people to reassess themselves, but I do wish it hadn't eventually destroyed the Sex Pistols – I would have loved to be able to talk to them, although I'm sure they wouldn't have listened at the time, because we were something which punk was reacting against."

1978 saw the release of Jazz, perhaps Queen's most controversial LP, and one whose title was inspired by a spray painting on a wall seen by Roger Taylor. It marked a reunion with producer Roy Thomas Baker, with whom the group hadn't worked since A Night At The Opera, having produced the two intervening albums by themselves. What did Queen hope to gain from the reunion? "An easy life? No, I'm kidding – we thought it would be nice to try again with a producer on whom we could put some of the responsibility. We'd found a few of our own methods, and so had he, and on top of what we'd collectively learned before, we thought that coming back together would mean that there would be some new stuff going on, and it worked pretty well."

The controversial aspect of the album concerned two tracks, 'Fat Bottomed Girls' and 'Bicycle Race' – it was decided to combine the ramifications of these titles to produce a live action video, which showed three hundred naked young ladies riding bicycles around Wimbledon Stadium, something which many might consider beneath Queen's dignity... "It was just a bit of fun really – we thought the two songs went together, and the album was sort of European flavoured. We'd never recorded in Europe, and we absorbed some of the feeling, and talked about how to sell the album, eventually opting for something which was really crass and blatantly commercial. That's what we did, and I can't make any apology for it, but it was fun at the time. Now I'm pretty indifferent to it – I don't think it made much difference either way, to be honest. It alienated a few people, won over a few others, but on the whole, it was a pretty small thing."

The 1979 Queen LP was a double live album, Queen Live Killers. "Live albums are inescapable, really – everyone tells you you have to do them, and when you do, you find that they're very often not of mass appeal, and in the absence of a fluke condition, you sell your live album to the converted, the people who already know your stuff and come to the concerts. So if you add up the number of people who've seen you over the last few years, that's very roughly the number who'll buy your live album, unless you have a hit single on it, which we didn't – maybe we chose the wrong one, which was 'Love Of My Life' in England and America."

One interesting track which highlighted Brian's guitar was 'Get Down, Make Love', on which there appear some peculiar effects. "That's a harmoniser thing which I've used really as a noise more than a musical thing. It's controllable because I had a special little pedal made for it, which means I can change the interval at which the harmoniser comes back, and it's fed back on itself so it makes all these swooping noises, and it's just an exercise in using that, together with noises from Freddie – a sort of erotic interlude."

1979 also saw Queen active, appropriately enough, in live situations, which were however abnormal, first when they played smaller venues, and at the end of the year, when they assisted a number of other star names in a week of concerts whose proceeds were designed to provide relief to the people of Kampuchea.

1980 saw a departure as far as Queen's records are concerned in the shape of The Game. "We approached that from a different angle, with the idea of ruthlessly pruning it down to a coherent album rather than letting our flights of fancy lead us off into different ideas. The impetus came very largely from Freddie, who said that he thought we'd been diversifying so much that people didn't know what we were about any more, so if there's a theme to the album, it's rhythm and sparseness – never two notes played if one would do, which is a hard discipline for us, because we tend to be quite over the top in the way we work. So the whole thing has a very economical feel to it, particularly 'Another One Bites The Dust', 'Crazy Little Thing Called Love', 'Dragon Attack', 'Suicide' – a very sparse feel to all of them, and for us, a very modern sounding album."

One new element in the recipe was an engineer/co-producer simply known as Mack. "He had a great deal to do with the way the album sounds. His name's Reinholdt Mack, and he's the greatest of the unknown engineers, although he's now becoming known and quite rightly so. He's done a lot of work for ELO, and worked with all sorts of people like Deep Purple and Led Zeppelin, but he's been stuck there in Munich, and nobody seems to have given him a thought that much – the typeface used for his name was always rather small – so we thought that having found him, we should make a big thing of him because he's really quite a phenomenon.

One important aspect of The Game to longtime Queen aficionados was that finally the group used synthesisers. "Actually, they overflow from the Flash Gordon album, because we were working on that at the same time. Roger's really the guy who introduced us to synths, because he had this OBX which he was playing around with, which obviously produced some good sounds, and synths had advanced an awful long way since those early days. You can now get polyphonic synths with a device for bending the notes which is much closer to the feel of a guitar than ever before, so now we use the synth, but sparingly, I think, particularly on The Game – there's very little there, and what there is merely complements what we'd used already, so there's no danger of the synth taking over, which I would never allow to happen, although I'm much happier using them than I used to be. I get a good feeling from playing the guitar which you don't get with anything else – a feeling of power, and a type of expression."

The Game was a remarkably successful LP, spawning no less than four top 20 singles in Britain, two of which Brian talked about in greater depth. "'Crazy Little Thing Called Love' was very untypical playing for me, and Mack actually persuaded me to use a Telecaster, which I'd never used on record before, and a Boogie amplifier, which I'd never have considered using. It's a very sparse record, and it was done with Elvis Presley in mind, obviously – I thought that Freddie sounded a bit like Elvis, but somebody's done a cover of it who sounds absolutely like Elvis, and the whole record sounds like a Jordanaires/Elvis recreation...A lot of people have used 'Another One Bites The Dust' as a theme song – the Detroit Lions used it for their games, and they soon began to lose, so they bit the dust soon afterwards, but it was a help to the record – and there's been a few cover versions of various kinds, notably 'Another One Rides The Bus', which is an extremely funny record by a bloke called Mad Al or something, in the States, and you should hear it, because it's hilarious. We like people covering our songs in any way, no matter what spirit it's done in, because it's great to have anyone use your music as a base, a big compliment."

Flash Gordon has already been mentioned, and was in fact an album of soundtrack music to the 1980 science fiction film of that name, with the music performed and written by Queen. "It was in our minds that we would be up for writing a soundtrack if the right one came along. We'd been offered a few, but most of them were where the film is written around music, and that's been done to death – it's the cliché of "movie star appears in movie about movie stars" – but this one was different, in that it was a proper film and had a real story which wasn't based around music, and we would be writing a film score in the way anyone else writes a film score, which is basically background music, but can obviously help the film if it's strong enough. That was the attraction, because we thought that a rock group hadn't done that kind of thing before, and it was an opportunity to write real film music. So we were writing to a discipline for the first time ever, and the only criterion for success was whether or not it worked with and helped the film, and we weren't our own bosses for a change, which was quite interesting."

The album contained a track which became a hit single, 'Flash', but rather more intriguing was 'The Wedding March', which seemed to be in the vein of Jimi Hendrix playing 'Star Spangled Banner' at Woodstock. "Things like that go back a long way with us – we did 'God Save The Queen', the beginning part of 'Tie Your Mother Down', and there's 'Procession' on the first album – those little guitar pieces. I'd heard Hendrix's thing, but his approach was very different, because he put down a line and then improvised another one around it, and the whole thing works on the basis of things going in and out of harmony more or less by accident – it's very much a free form multi-tracking thing, whereas my stuff is totally arranged and planned, and I treat it like you'd give a score to an orchestra. It lacks the improvisation part, but it's a complete orchestration, so it's a different kind of approach."

The major new Queen-related item in 1981, a year which also saw a Greatest Hits LP, a Queen video and a book of photographs about the group, was a single titled 'Under Pressure', a collaboration between Queen and David Bowie, which not surprisingly, topped the UK singles chart. "He lives near the studio we bought, in a little town close to Montreux, and when we were there, he'd often come over to see us, to chat and have a drink. Someone suggested that we should all go into the studio and play around one night, to see what came out, which we did, playing each other's old songs and just fiddling around. The next night, we listened to the tapes, because we'd left the tape recorder running, and picked out a couple of pieces which seemed to be promising, and then we just worked on one particular idea, which became 'Under Pressure', for a whole night...an extremely long night."

Otherwise, the album which eventually contained 'Under Pressure' – Hot Space – reflected a different method of creating songs from that which Queen had previously used, although there were some similarities in the evolution of The Game. "We were thinking about rhythm before anything else, so in some cases, like 'Dancer', the backing track was there a long time before the actual song was properly pieced together. We would experiment with the rhythm and the bass and drum track and get that sounding right, and then very cautiously piece the rest around it, which was an experimental way for us to do it. In one track called 'Backchat', there wasn't going to be a guitar solo, because John Deacon, who wrote the song, has gone perhaps more violently black than the rest of us. We had lots of arguments about it, and what he was heading for in his tracks was a totally non-compromise situation, doing black stuff as R&B artists would do it with no concessions to our methods at all, and I was trying to edge him back towards the central path and get a bit of heaviness into it, and a bit of the anger of rock music. So one night I said I wanted to see what I could add to it, because I was inspired by the backing track, which is very rhythmic and aggressive, but I felt that the song as it stood wasn't aggressive enough – it's 'Backchat', and it's supposed to be about people arguing and it should have some kind of guts to it. He agreed, and I went in and tried a few things."