Text

117. Rita Mae Brown (b. 1944)

I grew up in a society (communist Romania) that suppressed any reference to non-heterosexual desire other than as a psychological condition, an illness. Gay men were placed in psychiatric wards, and apparently there were no lesbians. So when I discovered Rita Mae Brown and her writings, it was a true revelation. I later came to fully appreciate the extent of her impact on the second wave feminist movement. This is a brief tribute to her contributions to enrich our understanding of patriarchy and her celebration of womanhood.

Rita Mae Brown was born in Pennsylvania and later abandoned to an orphanage, where an aunt and uncle retrieved and adopted her, eventually taking the family to Florida, where the Brown spent most of her childhood and youth. Her parents were active in local activities of the Republican Party during a period of time when segregation was still the norm.

Brown started college in 1962 and attended University of Florida just as the Civil Rights movement was getting off the ground. She was immediately drawn to the politics of anti-discrimination and human rights and started to organize, work with peers on campus campaigns against segregation, and was eventually expelled for her activities. After attempting to continue her education at a more inclusive institution in the South, she made her way to New York City in 1964, where she enrolled and completed a degree in Classics and English at New York University by 1969. She was scraping by, sleeping in cars and on friends’ couches.

Clearly passionate about the ways in which knowledge makers and cultural producers generated specific discourses about individual rights, democracy, and discrimination, she eventually earned further certificates and degrees in cinematography (the School of Visual Arts in NYC), literature (PhD from Union Institute and University) and political science (PhD from the Institute for Policy Studies). But for Brown knowledge was power only insofar as she could deploy it in the most public way; she did not aspire to academic glory or the security of an academic job. Instead, she remained fearlessly focused on being at the center of cultural fervor and political mobilization around the feminist movement.

Looking at Brown’s restless pattern of joining or starting specific groups and then leaving them behind, one might conclude she was someone who could never be pleased, either too radical or too irksome in her relations with others. Neither conclusion would be further from the truth. She joined the National Organization for Women with high hopes, but was marginalized and eventually kicked out by Betty Friedan because Brown insisted on the need to define patriarchal oppression and feminism in direct relation to their attitude towards lesbians and heteronormativity more broadly. Friedan wanted the organization she had started to remain “respectable” and represented Brown and other lesbian activists in NOW as “The Lavender Menace.” Before taking that derogatory term and turning it on its head, Brown first reached out to Friedan to ask her to reconsider. As I read her letter today, her request strikes me as eminently reasonable:

“There is contention among you [members of NOW], and fear that lesbian members will confuse your cause and the media. I ask you, have women ever been fairly represented in the media? Doesn’t the media, which is run by middle class males, always represent women unfairly? And isn’t the media’s image of women exactly what one of NOW’s goal is to change? Why not accept our help and the added force our identity brings so we can join our forces and double our strength together?... My interest is in the successful future of the feminist movement, and I hope that my remarks will persuade you to reconsider your position.”

Brown’s plea remained unanswered and she found herself rejected by other groups she worked with, inclusive of gay rights activists, because of various forms of prejudice and marginalization she considered to be at odds with the struggle against patriarchy and other forms of discrimination.

Resilient in her political passions, she turned away from organizing and mobilizing and towards writing and exposing. To date, she has published over 50 novels, 4 works of non-fiction, and has written more than 10 screenplays. Her first work of fiction made Brown a household name and reaffirmed her belief that good literature about lesbians was good literature that could change the attitude of many homophobes. Rubyfruit Jungle (1973) was partly based on Brown’s own experiences of growing up lesbian and her confrontation with heteronormativity, but focused primarily on the agency of the main character, walking the reader through her perception of the world, her traumas, the repeated humiliations and inequities she was exposed to by both open bigots and those she loved and cherished. The book was originally issued by a small press, but soon found a wide audience and was re-published to significant commercial success. It was the first lesbian novel to sell over 100,000 copies.

Though no longer the public face of “The Lavender Menace,” Brown continued her quest for exposing patriarchy and homophobia through the plots of her novels and screenplays, such as the documentary Mary Pickford: A Life on Film (1997). Pickford was the subject of a previous entry on this blog. Around the same time she published a memoir about her trials and tribulations with the feminist and lesbian communities, Rita Will: Memoir of a Literary Rabble-Rouser (1997). Today she lives on a horse farm in Virginia and continues to write successful mystery novels.

#rita mae brown#lavender menace#lesbian feminism#civil rights movement#writer#film#rubyfruit jungle#mary pickford#united states#century of women#national organization for women#betty friedan#homophobia

1 note

·

View note

Text

116. Lois Weber (1879-1939)

Lois Weber surrounded by members of her production company

Raised in the Pittsburgh area in the family of an upholsterer and street evangelist, Lois Weber grew up nurtured in her love of music. She was a very skilled pianist and singer and from early on used these talents to both assist the family’s financial needs as well as perform evangelizing social work. She came to see herself as a missionary who used music as a way to reach people and influence how they engaged with familial obligations, poverty, and other issues of social and moral concern, from alcoholism to birth control.

In her mid-20s, an accident on stage while she was performing on the piano (a key broke) led her to abandon music for the theater. She moved to New York City and began acting with several companies, but came to see this focus ill-suited for her aspirations as a social activist. By 1906 she quit the stage and got married.

During the next couple of years Weber sought a new outlet for her personal passion of advocating social and moral reform. A new opening came with the arrival in the United States of Alice Guy-Blaché (who was featured on this blog in a previous entry) and her husband, Herbert. Guy-Blaché was developing a film studio and vibrant career as a director in New York at that time. Weber worked for that company for a short period and got bit by the bug of film making. It is worth pointing out that, at that time, there was no Hollywood, no studio system and no “boys’ club” to shape this art form. There were only pioneers, and having a strong female director as an early experience with the medium must have emboldened Weber.

She first acted and then started writing scripts. Soon she was producing, directing, manufacturing sets and costumes, and developing film. In the early days, film making demanded a Jane-of-all-trades attitude and Lois Weber immersed herself in this adventure with body and soul. By 1911 Weber started to work together with her husband Wendell Smalley, with whom she collaborated very closely, for the Rex Company in New York City. They soon became the main movers and shakers of this company and moved to Hollywood in 1912, when Rex became a subsidiary of Universal, the company co-founded by Mary Pickford (also featured on this blog in a previous entry). Weber’s career took off at this time, as she became the de-factor manager of the Rex subsidiary and was given a great deal of freedom in her choice of themes and production techniques.

By 1914, she had gained the reputation of a hard working director (she directed 27 movies that year) as well as a trouble maker in the eyes of film censors. Having found in cinema the ideal outlet for her passion for social activism and evangelical preaching, Weber made films that tackled issues nobody else was making movies about: abortion; inter-religious love and marriage; and human trafficking. I would not characterize her outlook as explicitly feminist, but rather as deeply Christian, with elements of eugenicist thinking about what represented a social evil and what the remedies for such problems were. Extolling the virtues of love of family, care of others, and vilifying materialism and selfishness, Weber often painted women as fallen angels, agents of immorality, but also as individuals capable of great sacrifice and love. At the same time she supported birth control, having been influenced by Margaret Sanger’s contemporaneous crusade to decriminalize women’s access to safe birth control methods. In 1917 she made The Hand That Rocks the Cradle, which was released only after attempts to suppress it. It was a plea to consider women as worthy of making their own decisions when it came to becoming mothers, providing a sympathetic depiction of having an abortion on the part of women overburdened by other care-giving responsibilities.

Having experienced censorship of her films, in 1917 Weber decided to establish her own studio and to date is the only woman to have owned a major film studio in Hollywood and to have gained full control over the content, production, and distribution of her movies (though Ava DuVarnay is carving out a similarly independent path). Lois Weber studios was built through the financial resources she managed to acquire as the highest paid director in Hollywood at that time ($5,000 per week) and through her reputation as a director of vision and as an excellent team leader. Her prestige was further solidified when she was granted membership in the Motion Picture Directors Association, the only woman to become part of this important guild that influenced the Hollywood industry until the late 1930s.

For the next five years Weber was one of the dominant voices in film making. She continued to make films that engaged with difficult social issues while experimenting with new film, editing, and other production techniques. She nurtured the careers of many actors and was especially thoughtful in giving women writers and artists opportunities to work on her lot. She was a powerful model and provided hope for many women who wished to work in the film industry behind the camera.

But eventually Weber’s career began to falter. In her mid-40s and now divorced, Weber started to have difficulties in getting her message out, finding audiences interested in her serious films, and keeping up with some of the younger arrivals in Hollywood. Having rejected the big studios, she had to shoulder the financial difficulties of this decline on her own and was unable to continue. She still worked as a director off and on until her death in 1939, hired most often through the intervention of people whose careers she had helped launch or nourish, such as Frances Marion. But she came to be seen increasingly as a passé director without a good feel for audiences coming of age in the 1930s. She died from a long-term stomach ailment, destitute, and was buried with funds provided by Marion. The location of her ashes remains unknown.

Weber remained forgotten for a long time, but starting in the 1970s, film historians began to re-examine her legacy and bring into focus her important contributions to cinema. A 1996 study concluded: “Along with D.W. Griffith, Weber was the American cinema's first genuine auteur, a filmmaker involved in all aspects of production and one who utilized the motion picture to put across her own ideas and philosophies.” In 2017, through the efforts of several women intent on rejuvenating female production companies in Hollywood, the documentary Yours Sincerely, Lois Weber, recaptured the achievements of this pioneering film director.

#lois weber#cinema#united states#evangelical#production company#film director#alice guy-blaché#frances marion#margaret sanger#eugenics#hollywood#century of women#ava duvernay

1 note

·

View note

Text

115. Sophie Taeuber-Arp (1889–1943)

Sophie Taeuber, Portrait with Dada-Head, 1920

Sophie Taeuber was born in Davos, Switzerland, into the bourgeois family of a pharmacist (her father) and entrepreneur (her mother). Her father passed away when she was a toddler and her mother went into business as the owner of a pension, while also taking care of her family. Sophie proved very talented in the arts and her mother enrolled her in a trade school that admitted girls and taught textile design. In 1906, when Taeuber started, few art schools around the world allowed young women to enroll and crafts trade schools were often the only option. Their focus was on training future skilled workers, rather than artists and designers. But these trade schools became a place towards which many future female artists and designers gravitated, as my previous blogs on Hannah Höch and the McDonald sisters have shown.

Over the next decade, Taeuber spent time training in a number of design schools in Hamburg, Munich, and eventually returned to Switzerland to join the Schweizerischer Werkbund design group in 1915. She also trained as a dancer at the Laban modernist dance school in Zurich and in Ancona, Italy.

By 1915 Zurich had become a mecca for many avant-garde artists from around Europe who sought to escape the Great War and wished to respond to the madness of that conflict through new, explosive forms of art and performance. Taeuber joined the Dada movement at its very beginning and became one of the major players in this experiment and eventually in the constructivist modernist art and design movement. Though less well known than Piet Mondrian and Kasimir Malevich, by 1916 Taeuber had developed an original constructivist aesthetic that combined highly stylized geometric shapes with contrasting bright colors into compelling compositions. She also began teaching textile arts at the Zurich University of the Arts.

Taeuber also joined the band of Dada artists at the Cabaret Voltaire, where together with Emmy Hemmings and Hannah Höch, she provided a powerful counterpoint to the male-dominated experiments of the group. Taeuber was an intellectual force in the group and helped shape the Dada Manifesto that was published in 1918. She was a copious contributor to the body of work produced by the group during that period, from the Dada heads she became well known for, to textiles and graphic art. She also took part in the performances on the stage of the Cabaret Voltaire, at one point dressed in a costume and masque designed by Marcel Janco, suggestive of the Kachina dolls from the Zuni Pueblo.

After the war and now married to the artist Jean Arp, Taeuber-Arp moved to France and lived first in Strasbourg and eventually Paris. In France she continued to be an active leader in non-figurative constructivist art circles, exhibiting with others and generating art publications. She also gained several important commissions in interior design, which enhanced the scale of her work and rendered it visible and appreciated by a much wider public. In Strasbourg she helped design the interior of the Café de l'Aubette, which was later dubbed the “Sistine Chapel of Abstract Art.” The Café prefigured many themes of postwar modernist design.

During World War II, Taeuber-Arp moved from occupied to Vichy France and eventually back to Switzerland, when the art colony she had founded with Sonia Delaunay and Alberto Magnelli, among others, became threatened by the wartime authorities. She died in 1943 from accidental carbon monoxide poisoning.

Though her art ended up in many modernist collections around the world, her contributions to the development of abstract art and interior design have yet to be fully incorporated into the history of the modernist movement. Several retrospectives of her work were staged in the 1970s and 1980s. In a more recent nod to her important contributions to Swiss art, since 1995 she has appeared on the Swiss 50-franc note.

The interior of Café de l'Aubette as designed by Sophie Taeuber-Arp in 1926-28

#sophie taeuber-arp#switzerland#france#artist#modernism#dada#interior design#cabaret voltaire#dada manifesto#marcel janco#hannah hoch#sonia delaunay#piet mondrian#kazimir malevich#alberto magnelli#century of women#cafe de l'aubette#emmy hemmings#constructivism

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

114. Shulamit Firestone (1945–2012)

Born Shulamith Bath Shmuel Ben Ari Feuerstein into a strict Orthodox Jewish family in Ottawa, Canada, she grew up as one of the six children of a devout but profoundly sexist father. The family moved to St. Louis when Shulamit was a small child and anglicized the family name to Firestone. Subjected to treatment as an inferior class of off spring because of her gender, she rebelled against her family from early on and became a loner for the rest of her life.

Firestone attended a rabbinical college before going to the prestigious Washington University in St. Louis, where she received a BA in 1967. She also attended the Chicago Art Institute and received a BFA in painting. This was a period of deep radicalization of the feminist movement alongside and eventually in conflict with the male dominated leftist groups developing around the same time. Firestone joined the struggle, first intent on working with the National Conference for New Politics. The Black Panthers were welcomed with open arms at the 1967 gathering. But when Firestone and her colleagues in the New York Radical Women’s group sought the floor to add several points about gender justice to the discussion, she was patted on the head (literally) and asked to go back to her corner: "Cool down, little girl; we have more important things to talk about than women's problems."

Firestone responded by writing the radical Dialectic of Sex: The Case for Feminist Revolution (1970), which minced no words about the nature of patriarchy and placed the task of feminist activists squarely in the area of reclaiming women’s bodies and sexualities. Building on the Marxist analysis of class oppression, she concluded that patriarchy was inextricably connected to the attempt to control reproductive work and women’s power rested in denying men this control. Her analysis looked into the possibility of a future where reproduction would be separate from sex and sex separated from reproduction. For Firestone, “the end goal of feminist revolution must be, unlike that of the first feminist movement, not just the elimination of male privilege but of the sex distinction itself: genital differences between human beings would no longer matter culturally.”

The Dialectic of Sex was received with both enthusiasm among a small group of radical feminists, as well as mostly shock and disapproval by most other so-called progressives who believed they were fighting the establishment or “the man,” even as they derided uncompromising feminists like Firestone. Her activism also rubbed other radical feminists the wrong way. Over the late 1960s she had numerous conflicts with other activists in the New York Radical Women’s brigades and eventually was thrown out of her own group.

A series of familial conflicts further estranged Firestone from her family and left her more and more isolated. By the mid 1970s she was suffering from schizophrenia and had become unmanageable. People like Kate Millett tried to offer support, but the efforts of her few remaining friends failed to put Firestone on a path towards coping with her illness. When she died in her apartment in August 2012, nobody knew about it for about two weeks after it happened. Her heartbreaking end was a tragic coda to a life of passion and strife on behalf of a goal that many of us still hope for in our lifetime.

A much longer and very beautiful tribute to Shulamit Firestone, “Death of a Revolutionary,” can be found in the April 15, 2013 issue of the New Yorker, written by Susan Faludi.

#shulamit firestone#canada#united states#feminist#dialectic of sex#new york radical women#susan faludi#kate millett#orthodox jewish#century of women

0 notes

Text

113. Elise Ottesen-Jensen (1886−1973)

A leader in the anarcho-syndicalist movement in Scandinavia, Elise Ottesen-Jensen, also known as Ottar, dedicated her life to educating women about their rights, with the goal of empowering them in both public and intimate choices related to their sexual lives. She grew up in a rural Norwegian family of 18 children, her father a vicar with very narrow views on sexual matters. In particular, when Elise’s younger sister Magnihild became pregnant, their father sent her away to Denmark to force his daughter to give up the child, but the young woman understood nothing of her pregnancy before giving birth and eventually committed suicide. This traumatic experience played a pivotal role for Elise, who became radicalized in her views about the need to place sexual education and empowerment into the hands of women instead of paternalistic male figures and institutions.

In high school Ottesen had hoped to pursue medical education but suffered an accident that permanently damaged her fingers and thus turned towards journalism in college. While writing for left leaning papers she also sought to work as a socialist agitator, organizing working women. But the advice they sought was not so much about the factory floor as about their own bodies and specifically about birth control. During this period, sex advice columns were becoming more common in parts of Europe and North America, and Margaret Sanger was attempting to educate working class women about safe birth control methods. Ottesen switched her activism in that direction as well and embraced the anarcho-syndicalist movement, just as Sanger had done in the United States.

As the diaphragm and sponge were becoming used more widely after World War I (Marie Stopes had introduced the sponge in England around that time), Ottesen sought and found a Swedish doctor willing to work with her in providing good advice for women to both avoid pregnancies and also enhance their pleasure. Ottessen-Jensen (she had married by then) dedicated herself to writing frequently about these topics and travelling widely through the Scandinavian peninsula to speak to especially working-class women about their sexuality as a positive and empowering element of their existence, inclusive of same sex erotic relations. She was a sort of one-woman travelling sex clinic. By 1933 she became a founding member and the leader of the Swedish Association for Sexual Education, a position she retained until 1956. She continued to work with Sanger and other promoters of safe birth control methods for all women and in 1953 travelled to India for the inaugural conference of the International Planned Parenthood Foundation. In the earlier blog entry dedicated to Dhavanthi Rama Rau one can see Elise Ottessen-Jensen next to her and Sanger.

By 1945 Sweden became the first country to mandate sex education in its school system. This achievement, together with the rather open and positive view taken by Swedish sexologists on matters of reproduction and non-heterosexual erotic relations, should be viewed as legacies of Ottessen-Jensen’s arduous work along many decades. Among other awards and honors, in 1958 the University of Uppsala awarded her an honorary degree. She passed away in 1973, having suffered from uterine cancer for several years.

#elise ottessen-jensen#feminist#anarcho-syndicalist#norway#sweden#birth control#margaret sanger#sex clinics#international planned parenthood federation#dhavanthi rama rau#swedish association for sexual education#sexual education

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

112. Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander (1898–1989)

Image from the Delta Sigma Theta’s National Convention (1921). Dr. Sadie Alexander is the bespectacled woman on the right. She was the national President of the surority.

Sarah Tanner (later known as Sadie Alexander), was born into a prominent Philadelphia family that was known for its leadership in the African American community in religious matters (one grandfather was a Bishop in the AME Church) and as successful professionals. Raised primarily by her mother (her father abandoned the family when Sadie was a year old), Sadie was encouraged from early on to work hard in school and cultivate her intellectual gifts. She attended the excellent M street high school in Washington D.C. and was recruited to attend Howard University on a full scholarship, but her mother insisted that she return to Philadelphia and attend University of Pennsylvania starting in 1916.

Her experience as an African American woman in the overwhelmingly white environment at University of Pennsylvania was tough, but enabled her to better understand racism and fight it later on. She was a brilliant student and, although she earned a bachelor of science with honors in 2 years, she was denied entry into the honors society Phi Beta Kappa. Undeterred by these attitudes, she sought admission into graduate studies in the economics department at U. Penn. and 3 years later became the first African American woman to earn a Ph.D. in economics. She was only 23 years old.

If we were to compare her path after completing her PhD to that of a white American woman featured earlier in this blog, Mary Whiton Calkins (1863—1930), who was also a first in many ways, it becomes very clear what the color barrier meant in the United States in higher education during the 1920s. Calkins had been rejected repeatedly by Harvard, but found a welcoming environment at Wellesley, a women’s college, where she pursued a successful academic career as a researcher in her chosen field, psychology. After earning her PhD Sadie Alexander began working as an assistant actuary for an insurance company, a job she was clearly overqualified for. But for most African American women, even those of brilliant minds, waged work was a necessity and professional opportunities meager. Regardless of what Alexander hoped she would be able to do and what she was qualified to do, the society in which she lived saw her less through the lens of her mind and more through the lens of her skin color.

By 1924 she returned to Philadelphia to pursue a law degree at University of Pennsylvania, following in her father’s footsteps, who had been the first African American to graduate from that school. She was the first African American woman to do so and to also serve as the associate editor of the Law Review. In 1927 she graduated and passed the bar (the first African American woman to do so in Pennsylvania) and joined her husband’s firm to practice family and estate law. What followed was a lifetime of service in both private practice as well as public and professional service. She was a first in most of these appointments. She served as assistant public solicitor in Philadelphia for 14 years, as secretary of the National Bar Association for 4 years, and in 1947 was appointed by President Truman on the Committee of Civil Rights, the only African American woman member.

Alexander’s public service and much of her continuing private practice focused squarely on securing full civil rights for African Americans and defending individuals against racial and gender discrimination. She saw the Democratic Party as a defender of segregation and the Republicans as better allies, so her appointment by Truman appears even more remarkable. But Alexander was less preoccupied with party politics and more interested in bringing attention to the pervasive racist practices in employment, business, and access to public services among both parties and the white majorities they represented. She also worked with both government institutions and labor unions.

By 1970, the honor society Phi Beta Kappa finally saw its way to extending membership to Dr. Alexander. In 1977 she also received an honorary doctorate from her alma matter, and subsequently was honored with seven other such degrees. Today, the University of Pennsylvania has a professorship named in her honor. Alexander’s work on behalf of civil rights helped established the foundations that contributed essentially to the growth of the movement into the next decades. She passed away at the age of 91.

#sadie alexander#african american#economics#law#president's committee on civil rights#university of pennsylvania#civil rights#united states#mary whiton calkins#national bar association#philadelphia#century of women

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

111. Françoise Barré-Sinoussi (b. 1947)

Françoise Barré-Sinoussi is a French virologist who, together with her mentor Luc Montagnier (b. 1932), identified the human immunodeficiency virus and opened the door to finding a cure for AIDS. She was born in Paris and from early on had an abiding interest in the sciences. Initially she wanted to study and practice medicine, but eventually gravitated towards work in the laboratory as a virologist. In the mid-1960s women were generally not welcomed as peers in advanced science research and it would take a great deal of effort and time to break through that particular glass ceiling. Barré-Sinoussi figured out that working in a science lab on the ground floor would be the key to her being able to advance as a scientist and she knocked on many doors, offering to work as a volunteer, before someone said yes at the Pasteur Institute in 1970.

Her work in virology soon turned into a full-time passion that took her away from the classroom. She would show up for exams at the university based on notes other students shared with her and her own studies, while working in the lab, where she pretty much lived, like most other scientists dedicated to the sort of virological research she was passionate about. In 1975 she obtained a PhD in this specialization and began to work now as a full time researcher, first at the National Institute of Health in the U.S. and eventually back at the Pasteur, where she remained until her retirement a year ago (2017).

The start of Barré-Sinoussi’s career as a virologist coincided with the beginnings of the AIDS crisis and provided for her a research focus. It was a lucky combination for Barré-Sinoussi, the world of science, and most importantly the millions of people suffering from what was in the early 1980s a deadly but mysterious illness. Her lab in Paris became one of the most important sites for advancing knowledge initially about identifying the source of the virus, offering correct diagnoses, understanding its transmission, and eventually experimenting with various ways to cope with, slow down, and even eliminate AIDS. In 2008 she was awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine for her work.

While not the only important leader in this scientific quest, Barré-Sinoussi is remarkable also because of her commitment to do not just research, but also education and world-wide dissemination of information about the best ways to prevent the spread of the virus. In 2006 she was elected to the board of the International Aids Society and between 2012-16 served as its president. In this capacity she lobbied with governments, NGOs and even the Catholic Church to encourage the promotion of use of condoms as the most effective preventative form of reducing the spread of HIV. In 2009 she wrote an open letter to Pope Benedict XVI, harshly criticizing his remarks that condoms were not particularly effective in this regard. The Catholic Church subsequently changed its stance and acknowledge the effectiveness of condoms, though it has not actively supported this method, due to its dogmatic stance on any form of birth control.

In addition to her direct role in advancing science research, Barré-Sinoussi has also played a major role in encouraging younger generations and especially younger women to become scientists and to persevere in the face of sexism. She has been recognized both through the Nobel Prize in Medicine, as well as the Körber European Science Prize, and other important science awards. She has also been named an officer of the Legion of Honor and more recently elevated to Grand Officer, its second highest rank.

#francoise barre-sinoussi#virologist#biology#science#hiv#aids#nobel prize in medicine#korber prize#legion of honor#france#nih#century of women

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

110. Asma Jahanjir (1952–2018)

It breaks my heart to put this out as an obituary, rather than an appreciative biography of this amazing woman, who has been called “Pakistan’s social conscience.” But yesterday, her brave and generous heart stopped beating after she suffered a heart attack and we now must speak of her life in the past tense only.

Asma Jahanjir was born in Lahore in 1952, around the same time as Benazir Bhutto, whose biography can be found earlier in this blog. Though their biographies share some common elements, one very important quality separates Jahanjir from Bhutto: the desire for power. While Bhutto came to understand herself as the heir to her father’s political leadership, Jahanjir spent her entire adult life making sure that the voice of the most vulnerable people in Pakistan would get a fair hearing according to the rule of law and basic principles of democracy.

She grew up in a well-to-do educated family, with a father who served several jail sentences (including at the hands of Benazir Bhutto’s father) for his opposition to military rule in the name of democratic principles. Her mother was also well-educated and entrepreneurial, a role model for Asma and her siblings as an independent woman at a time when most women in Pakistani society preferred to embrace the traditional gender roles of this predominantly Muslim country. After completing her studies as a lawyer, Asma embarked upon a career that combined a private practice with civic activism. In 1980, together with her sister and a couple of other friends, Jahanjir opened the first all-female law firm in Pakistan, specializing on divorce and with a focus on defending especially the rights of vulnerable individuals (predominantly women).

Her experience with these cases opened up Jahanjir’s eyes even more widely to the brutally unjust treatment of women in her society and rendered her an unstoppable force in the quest for gender justice. Over time, the causes she supported through public activism and in taking on specific cases came to include other marginalized categories of people in Pakistan, such as the Christian minorities, who were severely discriminated in terms of freedom of speech. She also took aim at the growing authoritarian position of the military, especially in the last two decades of her life, by exposing their repeated acts of abuse.

Jahanjir paid dearly for her activism. In 1983 she was imprisoned together with other women activists who were protesting the new regulations that rendered women’s testimony in court less important than that of men. By 1986 she was forced into exile, because of repeated acts of aggression against her and her family. She spent 3 years in Geneva as vice-chair of the Defense of Children International, but eventually went back to Pakistan, where she believed her passion for human rights and her expertise would be most needed.

She co-founded the Human Rights Commission for Pakistan and became its leader, and eventually rose to the position of vice president of the International Federation for Human Rights as well as UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights. After her return to Pakistan, Jahanjir was relentless in her defense of basic human rights, the rule of law, and access to a fair, impartial judicial system for all people. She took on the cases nobody else wanted to touch, out of fear of “contamination.” Never someone to care about such issues, Jahanjir thought of herself as someone whose vocation was to support and guide those who were least equipped to assert their rights. For her actions, she became an object of intense hatred on the part of both the military establishment as well as the religious fundamentalist factions in the country. There were several attempts on her life and that of her family and staff, her daughters taken hostage at one point. In 2005 the police attacked her and tried to undress her in the street when she hosted a co-ed marathon aimed to bring attention to the violence against women. She was thrown in jail again in 2007 for speaking against the military dictatorship.

By the turn of the 21st century, Asma Jahanjir had become a symbol for women in South Asia and more broadly, giving hope to younger generations that women’s position in their societies could be improved by speaking out and acting with purpose. Though she passed away before her time, she left behind a rich and inspiring legacy. At the news of her death, Jahanjir’s co-national Malala Yousafzai stated: “The best tribute to her is to continue her fight for human rights and democracy.”

#asma jahangir#malala yousafzai#pakistan#feminist#human rights#divorce#islam#rule of law#lawyer#activist#century of women#bennazir bhutto

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

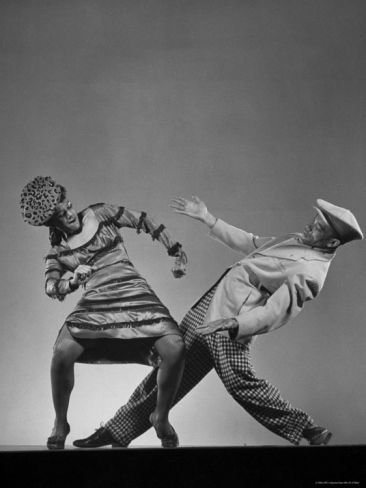

109. Katherine Dunham (1909–2006)

Katherine Dunham was born in Chicago and raised in nearby Joliet in a family of immigrants. Her mother was of French Canadian and Native American ancestry and her father’s parents came from West Africa and respectively Madagascar. She became interested in the arts when she was young, showing promise in both dance and creative writing. Her first short story was published at the age of 12. And she yearned to spread her love a dance to others very early on, opening a dance school when she was still in high school.

As she matured, Dunham followed her brother, whom she greatly admired, to University of Chicago. There he studied philosophy and she focused on anthropology as a means for better understanding the sources and development of African American culture, from music to dance. In that she resembled her equally talented contemporary Zora Neale Hurston (she was the subject of an entry earlier in this blog). Like Hurston, she became interested in researching Afro-Caribbean culture with a focus initially on Jamaica and later on other places, especially Haiti (1936). Dunham’s research settled primarily on the type of religious rituals developed around voodoo practices and, like Hurston, she also benefitted from a prestigious Guggenheim fellowship to conduct research.

During this period of intense studying and travels overseas, Dunham also nurtured her passion for dance as practice. In Chicago she met a Russian émigré, Ludmila Sperantzeva, with whom she first studied and eventually collaborated as teacher and choreographer. Sperantzeva’s syncretic knowledge of dance techniques from around the world had been a core component of her vaudeville dance troupe and fit very well with Dunham’s own sensibilities, for whom the separation between highbrow and lowbrow culture seemed quite limiting. Working with Spernatzeva while she also attended college, in 1933 Dunham opened a dance school, the Negro Dance Group. By 1934 she was also performing with the Chicago Opera in a star role, bringing with her members of her school.

Dunham’s troupe toured extensively throughout the United Sates and eventually overseas (57 countries). It became known for Dunham’s effervescent dancing and the type of innovative choreography the group promoted. In particular, Dunham was extremely skilled at translating various forms of traditional African and Caribbean dance into modern versions that retained the emotional intensity of these rituals but rendered them legible to a more secular audience with little knowledge about these traditions. Her abilities as a choreographer landed Dunham (and her company) credits in a number of Hollywood productions and on television. Her face and dancing moves became familiar to millions of viewers. Her work was at once teaching and performance, and audiences overall responded enthusiastically to Dunham’s vision. The only negative reception happened in parts of the United States, where some racist audiences rejected her celebration of African culture. Dunham reacted by taking the troupe on the road for nearly 20 years primarily outside the U.S.

After retiring from this intensive touring lifestyle in 1960, Dunham was asked by the Metropolitan Opera in New York to work as choreographer for a production of Aida. She was the first African-American woman to reach this level of appreciation at the premier opera company in the United States. Other commissions as a choreographer followed, but she retired by 1967.

But Dunham was by no means retired from public life. In 1945 she had founded the Katherine Dunham School of Dance and Theater in New York. The roster of the students who attended this institution reads like a who’s-who list of famous personalities in the Hollywood world, among them Eartha Kitt, James Dean, Shirley Mclaine, Sidney Poitier, Gregory Peck, and Jose Ferrer. The accompanying musicians included Charles Mingus and Marlon Brando. In short, between the mid-1940s and late-1950s the Dunham School was the place to be in New York City. Just as importantly, the school became known for its innovative breathing and movement techniques that have significantly reshaped the training of future generations of professional dancers. Several of her students still teach this technique and the Alvin Ailey company has also made use of the Dunham techniques.

In the mid-1960s Dunham made a dramatic life choice that can only be explained by her fundamental and unswerving commitment to fight racial discrimination: she moved away from New York and settled in East Saint Louis, a predominantly African American city across from St. Louis. Like other talented African Americans of her generation, Dunham had more than her share of humiliating experiences at the hand of racist audiences. When performing in the South, her troupe was not allowed to stay in certain hotels and often her audiences were all white, as African Americans had been prevented from purchasing tickets for her performances. Even when traveling abroad, in places like Brazil, they were no allowed to stay in the same high class hotels that white American businessmen stayed at.

Dunham’s reaction to these acts of racism was consistently to reject future working relationships with such agencies and individuals and to expose these attitudes as publicly as the media was willing to go. Because of that, she gave up a number of contracts in Hollywood, in various states in the South, and the financial support of the State Department when touring overseas. But she became a legend among those who saw a symbol of love and respect in all her public actions.

As a resident of East St. Louis, Dunham became deeply involved in local activism, both political and especially cultural. She opened the doors of her school to the most vulnerable children of that community, those whose poverty and family circumstances put them on a path towards gang life. She also used the academic appointment she received at nearby Southern Illinois University in Edwardsville to develop a curriculum that integrated the arts with the humanities in a holistic approach to college education and especially integrating African American studies, a pioneering endeavor at that time.

During the latter period of her life Dunham remained active in social activism both at home and overseas, especially in Haiti. Having travelled there many times for research, she eventually came to think of the country as a second home. In fact, she owned a house and extensive property in Port-au-Prince and spent many winters on the island, often working with local people on various cultural projects. That is why, in 1992 she decided to go on a hunger strike to protest the treatment of Haitian refugees by the U.S. government. She was 83. After 47 days of the very well-publicized strike and at the personal request of Jesse Jackson and Jean-Bertrand Aristide, Dunham ended her strike, out of fear for her life. Unfortunately, the record of the U.S. leadership with human disasters in Haiti and with Haitian refugees has continued to be appalling.

In addition to winning the Kennedy Center Medal of Honor and the National Medal of Honor, Dunham received many other awards from various national and international dance organizations, as well as from anthropology organizations and over a dozen honorary doctorates from various American universities, a combination I believe is unique for anyone in the twentieth century. She also won informal honors, such as the designation of “Katherine the Great Dancer” and “Matriarch of Black Dance." Her life has been an inspiration for generations of dancers and activists and her contributions to advancing African American culture and the rights of African Americans are a gift we all enjoy today, whether we know it or not.

#katherine dunham#dance#coreography#anthropology#african american#united states#haiti#racism#zora neale hurston#voodoo#century of women#ludmila sperantzeva

0 notes

Text

108. Lee Miller (1907–1977)

Lee Miller is second from the right, photographed during her deployment with the U.S. troops in Europe during World War II

To say that Lee Miller had an unusually rich and complicated life is an understatement by any measure. Her biography is a flashpoint for the history of art, journalism, gender relations, and sexual violence in the twentieth century, defined first and foremost by her strong will and embrace of adventure in the riskiest possible terms, with a “take no prisoners” attitude about herself and her interests. It is hard to imagine what she could have become, had she lived before the twentieth century.

But she was born early into the century into an upper middle-class family in Poughkeepsie, New York. Her father was an engineer and amateur photographer, so taking pictures and being in front of the camera were routine events at the Miller house. Young Elizabeth (she took the name Lee only in her twenties) was marked from early on by her close relationship with her father and the attention he lavished on her as both an artist and as a model, inclusive of nude photos that some observers have identified as bordering on the inappropriate. Just as importantly, at the age of 7 the young girl was raped by an acquaintance during a visit to Brooklyn and contracted gonorrhea, which resulted in lifelong physical and psychological problems.

A weaker soul might have been crushed by such violence so early in life. Miller was not. She worked through the physical pain by separating her experience of sexuality or sexual related sensations (such as caring for her STD) from her emotional investment in people. Love and sex seem to have been two separate realms for Lee, and she managed to keep that relationship clear enough in her own mind to enable her to enjoy both, despite the trauma of sexual violence experienced in childhood.

As she matured into a breathtakingly beautiful young woman, she began to model in New York City. Her experience with nude photography for her father rendered her a cool professional by the age that most other young women were still struggling with their appearance, even clothed. She eventually moved to Paris in 1929, at a time when surrealism ruled the day and other American expats, like the anarchist artist Man Ray, were riding the last wave of the roaring twenties, before the Great Depression would finally make it crash.

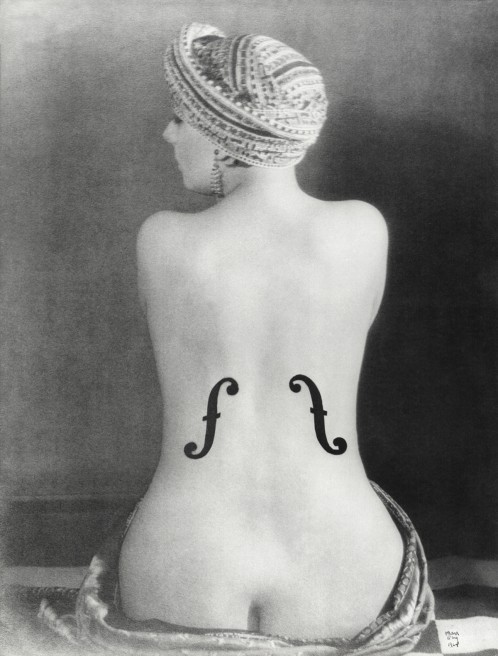

Miller made a huge impression on the Parisian art scene. Some knew her already from the pages of Vogue, where she had appeared for years. Others fell at her feet as soon as they met her. Miller embodied the cool blonde beauty that was all the rage at that time. She became a muse for Jean Cocteau and was featured in his films. She moved in with Man Ray and the two of them embarked upon a complicated relationship as artists. She posed for him and became the most frequent person photographed in his surrealist series that today are present in the best-known modernist collections in the world. In fact, it is likely that those images, such as the violin one at the bottom of this blog, are how most people know Lee Miller.

But Miller was also a partner in the artistic innovative adventures that Ray was involved with. First intent on being his student, she eventually joined him in the dark room side by side. The two played with various photographic techniques and perfected what is known as “solarization,” or the partial/total reversal in tone of the light in a print. In fact, she took thousands of photographs herself and experimented with the circle of surrealist friends that she joined for those few years. The Paris adventure came to an end in the mid-1930s, when she fell in love with and married an Egyptian engineer and took off with him to Cairo.

By 1937, restless as always, Miller had tired of the desert and returned to Europe, where she began a relationship with a British artist. She continued, however, to be interested in photography more than anything else, and during the war became the first accredited woman photojournalist with the U.S. army, traveling to the front in the company of soldiers on assignment with Vogue. She was there when Paris was liberated. She was among the first journalists to be allowed to photograph Dachau, and her pictures of that death camp became iconic images connected to the horrors of the Holocaust. She even took a photograph in Hitler’s bathtub as her personal moment of triumph over evil. After the war she lingered throughout Europe, as if the rush of this type of extreme photojournalism had become an addiction. When she finally returned to London, she was diagnosed with clinical depression.

Though she continued to take pictures, she eventually gave up photography as a professional pursuit, describing herself as being haunted by images she had taken. After dealing with depression through drinking and other means of self-medication, she was finally able to bring some peace to her life by reinventing herself as a gourmet chef. She had the means to host her famous friends at her country home in England and seems to have been somewhat content in feeding them and enjoying their company. For a while, she was also investigated by the British intelligence agency MI5 as a possible Soviet spy.

Miller died in 1977 from cancer, and by then she had been largely forgotten by the art world. It was only after her death and through the efforts of her son that her enormous photographic archive was brought into the public eye. But her contributions to photography and photojournalism remain poorly integrated in the history of these two important 20th century professions.

#lee miller#photography#photojournalism#solarization#man ray#united states#model#surrealism#jean cocteau#world war ii#holocaust#vogue#depression#century of women#sexual violence#chef

0 notes

Text

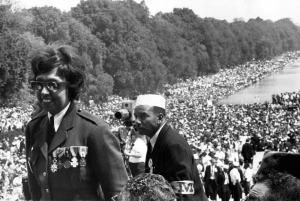

107. Josephine Baker (1906–1975)

Josephine Baker at a Civil Rights march in Washington, 1963. She is wearing the awards conferred by the French government in World War II. For more information about her, see the link below.

Today’s biography of the larger than life Josephine Baker comes from the blog hosted by the Women’s History Network and was written by Sophie Munro. The images she provides along the text are wonderfully evocative of the complexity of Baker’s life in relation to both her birth country, the United States, as well as her adoptive country, France: https://womenshistorynetwork.org/josephine-baker-1906-1975/.

#josephine baker#dancer#cabaret#african american#racism#world war ii#civil rights movement#united states#france#rainbow tribe#naacp#segregation#french resistance#sophie munro#century of women#women's history network

0 notes

Text

106. Nellie Neilson (1873–1947)

Born into an affluent family in Philadelphia, Nellie Neilson benefitted from many opportunities opening up to women when she was growing up. She attended the newly founded all-girl college Bryn Mawr for her undergraduate and graduate degrees and received her PhD in history in 1899, with a thesis on Medieval history of agrarian relations in Britain. She was offered a position at her alma matter and within a few years she went on to teach at Mount Holyoke, another distinguished women’s college, which at that time was developing a reputation for very high standards among its faculty. By 1911, a decade after Neilson was appointed there, 34 of its 90 faculty members held PhDs, a very impressive ratio at that time.

The faculty at Mount Holyoke were expected to uphold high academic standards as both researchers and teachers. However, they were neither paid as well as men at similar institutions, nor were they supported in their research in similar ways. While Neilson worked there, sabbaticals at half pay were introduced and helped researchers take some time off. But those who were not as well to do as she was, based on her father’s generosity, could hardly afford to take off for a research trip to Europe, for instance.

While studying for her PhD Neilson became active in the Royal Historical Society in England and acquainted with some of its luminaries, with whom she would later collaborate. Among them was Eileen Power, who would rise to prominence as an economic historian of Medieval Europe after World War I. (I blogged about Power on this site at some point in the past.)

Neilson went on to become chair of her department and a very active member of both the Royal Historical Society as well as the American Historical Association and the American Political Science Association. Her books and articles focused on the relationship between local custom and English common law in rural areas. She became a sophisticated analyst of the primary sources others used and introduced new types of historical evidence in her research. She is not known to have had an interest specifically in women’s history.

The most prominent recognition of her work and its impact came with her election as the first female president of the American Historical Association (AHA) in 1943. She had also been the first woman to have an article published in the American Historical Review, the chief publication of the AHA and the “journal of record” for that organization. In the early 1930s she was nominated for the presidency for the first time but did not succeed in the election. In the end, her election happened in great part because of the relentless lobbying on the part of the Berkshires Conference of Women Historians for four years. It may also be that, with many men off to war, 1942 was a bit more balanced in terms of the voting constituency.

Unfortunately, by 1943 Neilson was quite ill and half blind, so her victory was bitter sweet. She continued to be active in the organization until her last days. She passed away in 1947.

#nellie neilson#history#medieval#english#agrarian#mount holyoke#bryn mawr#american historical review#american historical association#royal historical society#eileen power

1 note

·

View note

Text

105. Victoria Tauli-Corpuz (b. 1951?)

This is a shorter entry than I would have wanted and I hope to enhance this biography over time. But I wanted to include Victoria Tauli-Corpuz because of her remarkable work for decades on behalf of Indigenous persons’ rights, first in the Philippines and more recently at the global level.

She was born into the Kankanaey Igorot group who live in the northern part of the Philippines, most likely in 1951. In 1969 she graduated from high school in Quezon City and in 1976 she completed a nursing bachelor’s degree at the University of the Philippines, Manila. By then she had already made the choice to become an activist and had helped organize the Indigenous people’s movement in the Cordillera region, where she originally hailed from. During this period, the Filipino authorities had decided to build a hydroelectric dam on the Chico River, where many of the Indigenous groups of the region lived, and who would be displaced by this action. Their traditions, livelihood, and safety were not subject of much research and their voices were not consulted when the government decided to take up this project. The World Bank was a partner and supporter of this type of ‘development’ as a form of progress, ushering new opportunities for the Filipino economy, regardless of the human and environmental costs on those most directly affected.

Tauli-Corpuz was one of the leaders of what emerged as an early form of Indigenous rights environmental movement. She also fought the Cellophil Resources Corporation, which had won permission from the corrupt Marcos dictatorship to begin logging in the same region, again with no regard for the environmental, cultural, and socio-economic impact on the local Indigenous tribes in the region. To her credit and that of other leaders who helped organize local, national, and international protests against these enterprises, both projects were cancelled.

Subsequently Tauli-Corpuz rose to international prominence as a global leader in the struggle to bring about greater awareness regarding the exploitation of Indigenous people. She founded a number of international NGOs, such as the Tebtebba International Center, whose advisory council includes Rigoberta Menchu-Tum and Winona La Duke, both of them subject of earlier entries in this blog. The majority of the members of this advisory group are also feminist activists.

The most remarkable achievements of Tauli-Corpuz after her successful actions to block potential environmental disasters in the Philippines have been in the U.N. In 1993 she helped draft the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and spent over two decades to get it adopted by the U.N. in 2007. Four countries opposed this declaration: Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United States. Since then, she and other leaders of Indigenous people’s rights have been working with these countries to overturn their position, succeeding in the case of Australia and Canada, but without any formal recognition on the part of the U.S. and New Zealand to date.

Between 2005 and 2010 she served as Chair of the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues. She was then promoted to the position of U.N. Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and worked with Christiana Figueres and other environmental feminist activists to make sure that the interests of Indigenous people and especially women’s concerns would be well represented at the Paris meeting in 2015 that developed the text of the U.N. Convention on Climate Change. It is in no small measure because of Tauli-Corpuz’s presence, insistence, and skillful collaboration with various NGOs that references to the rights and safety of Indigenous persons are present in the final document of this Convention.

Since then, she has continued to speak strongly on behalf of the same principles, most recently in relation to U.S. government actions towards Native American interests at Standing Rock and Bears Ears National Monument.

In 2009, Tauli-Corpuz was the recipient of the first Gabriela Silang Award, conferred by the National Commission on Indigenous Peoples in the Philippines.

#victoria tauli-corpuz#philippines#indigenous people#environmentalism#feminism#declaration on the rights of indigenous people#igorot#kankanaey#christiana figueres#winona laura horowitz#winona laduke#rigoberta menchú

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

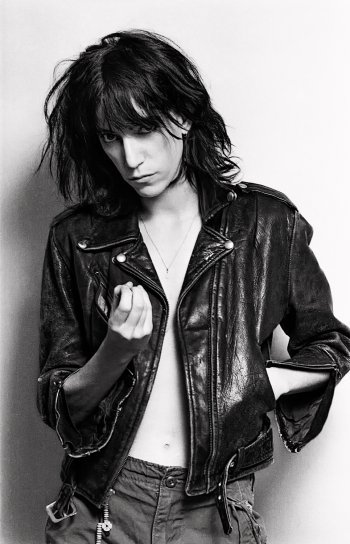

104. Patti Smith (b. 1946)

This is the hardest entry I have had to write for this blog up to now. When someone is still vibrantly putting out new books, recordings, performances, statements, to select which of their acts have been the most significant up to now is virtually impossible, because eclecticism has been a core component of that output up to now. How can one honor this eclecticism while also making sense of it?

I came to appreciate Patti Smith especially after reading her fabulous autobiography Just Kids (2010), and much of what I have to say about her is inspired by her words. I rely on her so heavily because of the combined unvarnished honesty of that text and the poetic qualities of her descriptions. Her words are more evocative to me than anything I’ve read that was written about her by others.

Patti Smith was raised in a working-class family from the Midwest, who moved out east—Philadelphia and then New Jersey—as she was growing up. Her mother was quite religious and that affected Smith’s own approach to some big moral questions, such as whether to have an abortion or give up the child for adoption. But her mother also placed in front of Patti some very influential music selections, especially early recordings by Bob Dylan. After graduating from high school, Smith did what many other working-class young women of that generation did—she worked in a factory. She also got pregnant and decided not to have an abortion and instead give up the child for adoption, a difficult choice she writes about with aching honesty in Just Kids.

Smith’s life took a radical new direction when she decided to try her luck in New York City in 1967 and met Robert Mapplethorpe. The two had a lot in common in terms of their familial background and they were both intensely interested in figuring out how to be part of the cultural effervescence that defined the city. They lived on the edge of homelessness and in poverty for years, but they became extremely rich in the connections they made with the art, music, and literary world. They experimented with everything, from words to sex. And they remained committed to an honest exploration of their obsessions, dreams, fears, and messiness of life.

Smith became involved with many projects that combined her deep love of poetry and the spoken word with performances on stage, in films, and in many happenings, some of them better documented than others. In the late 1960s she moved towards experimenting with music, even though she had not grown up with any training in this area. But during that period many artists experimented with every genre of musical performance and Smith transitioned seamlessly towards writing songs and performing with various rock musicians. She became a regular at CBGB and eventually put out the album Horses (1975), which has been hailed by many music critics as one of the top 100 albums of the century. A combination of punk rock and spoken word, Horses was highly original, encapsulated her creative spirit, and made Smith famous. She began to tour intensely and to write more music, but eventually had an injury that forced her to take a break and re-evaluate her priorities.

Smith took a hiatus from performing music in public, but she continued to live through music and poetry as she made a family and raised two children. She also had her share of tragedies, from Mapplethorpe’s death in 1989, to the death of her husband and then her brother. But by the mid-1990s she returned to the recording studio and began to make more appearances at festivals and for various social and political causes, such as the Green Party. She also began to publish autobiographical writings, first Just Kids and more recently M Train (2015). She has become a global celebrity, popping up on TV series, at festivals and ceremonies, and on occasion joining other artists on their own tours. In December 2016 she represented Bob Dylan as the awardee of the Prize in Literature through a performance of his song, “A Hard Rain's a-Gonna Fall,” for the Nobel Prize ceremony in Stockholm.

At 71, Patti Smith seems to be riding a wave of fame and appreciation, using her celebrity to speak on behalf of causes such as freedom of speech, pacifism, environmentalism, and anti-authoritarianism. There is no sign she is slowing down, and I may have to come back and revise this blog at some point. I look forward to watching and hearing her speak truth to power as she has always done, undeterred by critics.

#patti smith#robert mapplethorpe#horses#just kids#musician#poet#perfromance art#green party#bob dylan#punk rock#cbgb#united states#century of women

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

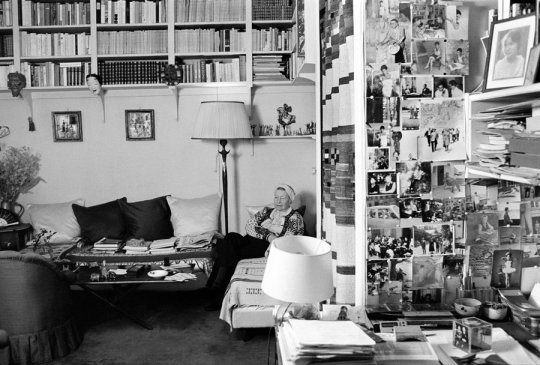

103. Simone de Beauvoir (1908–1986)

If there is one globally prominent name associated with feminism in the twentieth century, it is Simone de Beauvoir. Her book, The Second Sex, has been translated in over 40 languages and has reached billions of readers worldwide since its publication in 1949. It virtually framed the big questions that would animate the second wave feminist movement starting in the 1960s.

Simone de Beauvoir was a lifelong Parisian, born into a lower middle-class family that aimed to preserve their bourgeois status while struggling economically. Her father worked as a legal secretary, while her mother raised the couple’s two daughters and inspired in them deep religious faith. Later on, she summarized the impact of her upbringing as follows: “My father's individualism and pagan ethical standards were in complete contrast to the rigidly moral conventionalism of my mother's teaching. This disequilibrium, which made my life a kind of endless disputation, is the main reason why I became an intellectual.”

As an intellectually precocious girl, Simone was sent off to a prestigious convent school, an educational environment that initially greatly reinforced her sincere Catholicism. She went on to complete her baccalaureate at 17 and initially enrolled in the Catholic Institute of Paris, later moving on to study philosophy at the Sorbonne. She was a brilliant mind and often awed both students and the professors (the latter exclusively men) with her ability to develop philosophical arguments. One needs to remember that at that time, only a handful of other women had attended the Sorbonne and the philosophical canon did not have much respect for women philosophers. Within three years of graduating from high school she had earned the equivalent of an MA degree in philosophy at the Sorbonne. She was 20.

She moved on to take the aggregation soon after, a highly competitive exam that placed individuals on nationally ranked list of potential civil workers, such as teachers. Though she had not enrolled officially in the École Normale Supérieure, where the preparation for the exam took place, de Beauvoir placed second in the nation, barely overtaken by the person placed first, Jean-Paul Sartre. At 21, de Beauvoir was the youngest person to pass the exam and likely the most impressive in terms of her gender and placement, given the educational structures and opportunities that universally discriminated against women.

Subsequently she worked as a high school teacher until she was able to begin earning enough to live off her writing. She also took up living with Sartre, though de Beauvoir’s personal life was far more complex (as was Sartre’s): over time, she had many lovers of both genders and shared some of them with Sartre. She also engaged in erotic relations with women who were her high school students, in essence a sexual predator by today’s standards. Some of her love interests later wrote of these abusive relations and depicted de Beauvoir as a dangerous seductress.

De Beauvoir became an intellectual superstar in part because of her relationship with Sartre, whose star started to rise in the early 1950s. But she earned her reputation to a much greater extent because of her extraordinary qualities as a thinker and writer. She wrote philosophy, travel journals, and novels. And her talents became recognized through both critical and popular acclaim. In 1954 she became only the 3rd woman to win the prestigious Prix Goncour, the highest honor in France for fiction writing. She was awarded the prize for the novel The Mandarins (1954), which followed the lives of a circle of intellectuals in France at the end of World War II. The book was a loosely veiled autobiographical exploration of de Beauvoir’s complicated relationships with Sartre, Albert Camus, and Nelson Algren (for some time de Beauvoir’s lover). It also delved into the socio-political and cultural aspects of gender norms in France at that time, in essence a vehicle for de Beauvoir’s existentialist feminism. In essence, the book explored some of the same themes as those developed in The Second Sex, but in a freer fictional form. I personally find The Mandarins a much better read than The Second Sex and remember very clearly reading it when I was a teenager and starting to understand the profoundly masculinist epistemological foundations of intellectual life in Europe at that time (and into my time, which was the 1980s Romania).

But it was The Second Sex that put de Beauvoir on the firmament of most influential feminist thinkers of the twentieth century. When the book was translated into English in 1953, it fired up the imagination of many women. Betty Friedan, in her Feminine Mystique (1963), singled the book out as an inspiration. Germaine Greer and Kate Millett, both luminaries of the second wave feminist movement, also described de Beauvoir as deeply influential for their ideas. Later on, Judith Butler and other feminists who developed queer theory, also mentioned de Beauvoir’s notion that “one is not born, but rather becomes, a woman” as an important pioneering framework for critiquing the essentialism of thinking of gender as a biological fact, rather than socio-cultural construct.

By the writing of this blog, de Beauvoir has had several generations of critics and admirers. I have never enjoyed reading The Second Sex, which I found both poorly written and at times poorly argued, with some self-contradictory claims that do not make for a persuasive argument. I also found her critique uninspiring in terms of moving beyond patriarchy. But, given the expansive size of the book and the massive undertaking it represents in terms of research and synthesis, it does offer some very impressive elements of a feminist theory. And given the fact that it was written in 1949, when virtually no other philosopher wrote in that way, it is highly original. As such, it can be indeed seen as a landmark in the history of feminist thinking. For those who have read The Second Sex but not her fiction, I highly recommend starting with The Mandarins. It is a lively and captivating read that delivers some of the same feminist points as her philosophical work, but with a lot more flavor.

Besides her writings and activities as a well-regarded public intellectual in France, de Beauvoir did relatively little in relation to the feminist movement. One important public action she is known for, however, is to have signed the Manifesto of the 343 (1971). The document aimed to expose the hypocrisy of the French legislature for resisting the legalization of abortion as a form of birth control. The Manifesto was a form of civil disobedience, as it provided clear evidence that the signatories had engaged in a criminal act punishable with jail time. Like other famous women in France, de Beauvoir outed herself to expose the prevalence of the practice and absurdity of the law. The gamble succeeded in putting pressure on the legislature, and in 1975 abortion was decriminalized.

During her last years, De Beauvoir wrote mostly travel journals and short stories, and edited the correspondence she had with Sartre and other prominent intellectuals around the world. Many of these personal writings came out after her death in 1986 from pneumonia. The revelations they have unearthed about de Beauvoir’s personal life and ideas keep scholars revising their view of this complicated writer’s life.

#simone de beauvoir#feminism#france#existentialism#the mandarins#manifesto of the 343#abortion rights#betty friedan#kate millett#germaine greer#jean-paul sartre#century of women#philosophy#catholic#judith butler

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

102. Carolee Schneeman (b. 1939)

Carolee Schneeman, Eye Body: 36 Transformative Actions for Camera, photo series, 1963.

Raised in rural Pennsylvania in the family of a doctor, Carolee Schneeman showed an interest in drawing and nature early on. She was fascinated with the human body and wanted to explore it through art. Though her parents did not favor attending art school, Schneeman applied to Bard and, having received a scholarship, became the first woman in her family to attend college. Later on she took classes at Columbia as well and spent a few years at University of Illinois completing an MFA. She soon returned to New York City, where her husband and creative partner, James Tenney, had just received an appointment as a computer musician with Bell Laboratories.

Schneeman was initially interested in painting as a medium and has remained active in it. But she started to explore other ways of artistic expression, from photography to film and performance art. The early 1960s was a period when performance art became increasingly favored by some of the more avant-garde as well as politically motivated younger artists. Her turn away from Abstract Expressionism was also motivated by Schneeman’s vibrant feminism. Like many other women artists at that time, she came to see this movement as a boys’ club and became interested in moving in new, unexplored directions that reflected more directly her own passions and artistic vision.

Having moved to New York and into relationships with some of the avant-garde artistic circles there, Schneeman began collaborating with a number of groups, among them dancers and theater performers at the Judson Dance Theater. The experience moved Schneeman in the direction of “kinetic theater” art performances that would soon render her a figure of much controversy in both the art world and among feminist movements. Schneeman was and remains deeply interested in human sexuality as a non-voyeuristic experience. But the specific articulations of this artistic vision often appeared exploitative or narcissistic to her viewers, and few in the early 1960s or even the mid-1970s were fully prepared to see Schneeman’s visual performances through the artist’s own perspective.

In 1964 she created Meat Joy, which treated human sexuality playfully, satirically, and without a tinge of voyeurism, in part by having the performers clad in bathing suits. The performance thus is rendered more of a ballet and the performativity of the participants is marked clear as both about sex as well as non-sexual. The ironic interspersing of sexual movements with chunks of meat further upsets any expectations about eroticism. Subsequently she created Fuses, which represented an attempt to depict sexual pleasure as non-objectifying, especially in relation to women’s bodies. With a cat as the only observer and the camera running without any authorial eye directing angles and the framing of the action, the film is disorienting, unclear, jarring, and yet it carries a raw and authentic quality about the sexual acts presented that enables the viewer to adopt a variety of perspectives in relation to the images.

By far the most controversial and for a while criticized piece was Interior Scroll, a work she staged and performed at a feminist festival in East Hampton, New York, in 1975. Situating herself on a table, Schneeman began by disrobing, marking her naked body with traces of paint, and reading while taking on various poses. Initially, she read out loud part of a book she had written. Eventually she took on a slightly flexed position, began pulling a scroll out of her vagina, and started reading the text on the scroll. This part proved to be both the most controversial, but also the most inspiring among Schneeman’s feminist artistic expressions. The literalness of the act of creating with the vagina and connecting words, images, and the site of giving life have inspired generations of artists. The performance has been re-enacted by a number of other artists. It was also a powerful source of inspiration for the Vagina Monologues.

Many established artists and collections shunned Schneeman’s work for a period of time, seeing it as either too feminist or inauthentically feminist and exploitative of the female body. She seems to have been moved by neither of these criticisms and continued to do her work. More recently, as the art world has moved to embrace feminist artists, Schneeman’s star has risen. Her work is now part of major museum collections throughout the world and in 2017 she received a lifetime award at the Venice Biennale, bringing renewed attention to Schneeman’s contributions to the art world over the past half century.

#carolee schneemann#interior scroll#vagina monologues#performance art#united states#feminist#century of women#meat joy

1 note

·

View note

Text

101. Celia Cruz (1925–2003)

Once in a while, another blog focusing on the women I am interested in presenting here provides the biographical sketch I would have written. This one, penned by Maria Quintana, provides an excellent overview of Celia Cruz’s remarkable career as a musician and trendsetter in Latino culture over the second half of the twentieth century: http://www.blackpast.org/gah/cruz-celia-1925-2003. For more biographies of other remarkable women of color in the history of the United States, visit the blackpast.org website.

0 notes