Text

Medium

I’ve migrated over to Medium. Here is my account.

I have found that more people read and engage with my content over there. I’m sure that will change someday and I’ll write somewhere else.

3 notes

·

View notes

Link

1 note

·

View note

Link

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

SREC Overview

*Photo Credit

For a job I had recently I was asked to research SRECs. Here’s the overview I came up with.

In 2003, Massachusetts established the Renewable Energy Portfolio Standard (RPS). RPS created a mandate for Retail Electricity Suppliers (utilities) to buy Renewable Energy Credits (RECs) to offset their environmental impacts. If utilities are unable to purchase enough RECs to meet their mandates, they make Alternative Compliance Payments (ACPs). ACPs are essentially fines that create a ceiling price for the REC market. Producers yield a profit by selling their RECs to utilities, generally through an aggregator for a fee. Utilities are required to offset a certain percentage of their production (which increases each year) with RECs, essentially creating a floor price.

Facilities that generate "renewable energy" create a corresponding amount of RECs (1 credit equals 1 MWh of production). Solar photovoltaic generation falls under RPS Class I. The ACP for this class started at $50 in 2003 and is now up to $67.07 in 2015, and should continue to increase slowly but steadily.

In 2010 Massachusetts created an extension to the RPS called the "Solar Carve-Out," often referred to as SREC (Solar Renewable Energy Credit). This program was designed to incentivize solar photovoltaics. The administration set a goal of installing 250MW of production by 2017, and SREC ACPs will last for 400MW of installed production. This program created ACPs for solar photovoltaics at a rate about a magnitude higher than previously seen. The ACPs launched at $600 in 2010, and will steadily fall to $330 by 2025, the end of SREC. These incentives were highly successful, and newly installed solar reached the 250MW goal by May of 2013, three and a half years ahead of schedule.

Building on the success of SREC, and coming in to prevent a cliff at its end, SREC-II debuted in 2014. The volume of SREC-II was set at three times greater than that of SREC: 1,200MW (often referred to as 1,600, because official documentation includes production already installed through SREC). The administration has a goal of reaching this number by 2020. The ACPs are lower than with SREC, starting at $375 in 2014, and falling to $244 by 2025. The program will run through 2030, although the ACPs for the later years of the program have not been set yet.

Facilities generate SRECs at various rates depending on their type. Residential systems under 25 kW can access the SREC program at a 1:1 ratio (1 MWh:1 SREC). Most residences choose to keep their systems smaller than 10 kW because of net metering* caps. Larger facilities are given smaller multipliers, decreasing roughly as the size of a facility increases, ranging from 0.9 to 0.7.

0 notes

Quote

For the most part Americans were the descendants of a multitude of peoples, tribes and nations who had lost or fled their original homelands, usually losing in the process their languages, their stories, their food, their songs, their etiquette, their clothing styles and their identities, all of which made these first immigrants feel alone and powerless. The possession of money became one of the prime tools that all displaced people could use to gain a feeling of power in such a villageless society where little else was ultimately respected. But the hollow place of their loneliness and lost identities were never filled by the percentage of people that finally achieved a full bank account.

The generations that followed of what could now be called Americans, though distant from their ancestral losses, still carried that emptiness, but never lost the habit of thinking money made them valuable.

Thus, accustomed to paying for everything they had, assuming as well that by paying they could obtain anything they wanted, they needed money, like soldiers needed guns, to equalize their power by its possession, money which did not reflect the possessors’ abilities, strength or experience and which in the end did nothing but anesthetize the rancoring desire for home, village and a spiritual purpose.

Page 345 of “The Toe Bone and the Tooth,” by Martín Prechtel

1 note

·

View note

Text

Christianity’s Quirks

I recently came across a piece on Aeon about the rise of Catholicism over the past half-century in the United States. I grew up in the Catholic church, and I’d kind of always assumed that being Catholic was always just part of being American. Not for everyone, but as part of the mainstream. Apparently I was wrong.

I’ve also been reading the “Mists of Avalon” by Marion Zimmer Bradley. As an child, an ancient-looking copy of the book sat up on one of our book shelves. Recently a friend mentioned it to me again. And I saw that the author wrote a book review of “The Fifth Sacred Thing” [Starhawk]. And Isaac Asimov considers it the best retelling of Arthurian legend. So it seemed worth a read.

The Mists has a reputation as being about the sacred feminine or something, but I think it’s more a book about the negative manifestations of Christianity.

Anyways, with Christianity so much on my mind, I’ve been thinking about how much of it’s imagery, on the surface, is utterly bizarre.

Cross

First, there’s the cross. What kind of institution uses the symbol of cruel and unusual execution as it’s logo? The US government doesn’t use a Pakistani child being blown up by a drone missile as it’s logo. And, as John Michael Greer pointed out in one of his posts, the German National Socialist Party didn’t proclaim “Vote for Hitler so fifty million will die!” And yet that’s the vibe I get from the cross.

Wikipedia would have you know that, at the inception of Christianity, they had nothing to do with the cross. Around 200 AD, detractors started using the symbol to represent Christianity. Around 400 AD Christianity adopted the symbol. And then only by 600 AD did the crucifix [the cross with a dead Jesus on it] begin appearing.

Of course, Christianity didn’t invent the cross. It’s a very ancient symbol, used by many different cultures before Christianity.

Communion

Every time communion comes up [which is, at every service], Christians are presented with the “body” [bread] and “blood” [wine] of Christ, and instructed to eat it. On the surface, this appears as cannibalism. Which, overall, has been shunned in the “civilized” world for quite some time.

Of course, by consuming, we become. Maybe that’s the imagery they’re getting at.

Virgin Mary

Jesus’ mother, Mary, is considered to have conceived without a partner. Now that’s pretty weird. Sex is a natural part of reproduction in many species. Asexual reproduction is also common in some species. Homo sapiens are not one of these.

Old Testament and Judaism

Have you ever noticed the similarities between the Old Testament and the Torah? They go deep. Not only that, but Jesus was a Jew. Why be Christian when another religion already is on top of it?

Translation

The bible is a composite of many different texts from many different times. In order to actually understand the bible, you’d need to be fluent not only in a handful of ancient languages [Greek, Hebrew, Aramaic], but also be fluent in those ancient cultures. Meaning is relatable when there’s a common context. And we have anything but a common context with the authors and editors of the bible.

In other words, reading modern versions of the bible is like playing a two-millennia-long game of telephone. Understandably, we have no idea what the bible’s about, even though the Church would beg to differ. Sure, there’s still some good that can come of “Christian values,” but their intactness is highly doubtful.

-

This lists of the weirdness of Christianity goes on and on. I’ll stop here, but hopefully I’ve piqued your interest, and you’ll be thinking about this for weeks to come.

*Image Source

0 notes

Text

Reason to Intuition

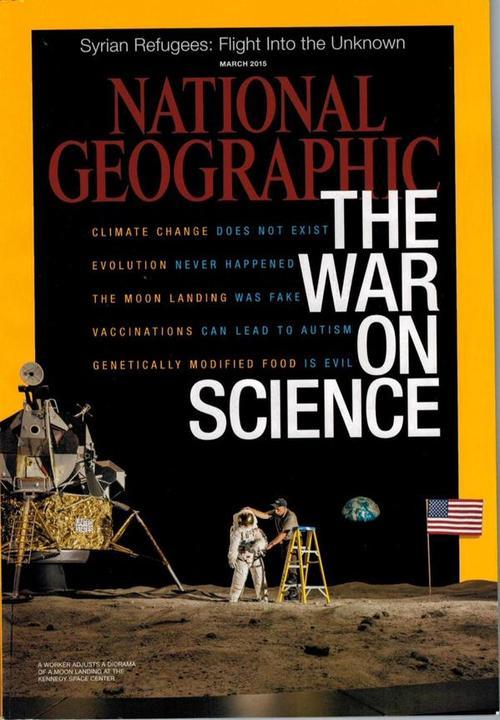

The cover article of the March 2015 National Geographic is entitled "The War on Science."

It's thesis seems to be related to defending the worldview of reason. To stereotype, reason is about developing controlled frameworks that model linear systems. It's the worldview of separation and control; progress through "high" technology.

The article mourns the death of the Age of Reason, but without an eye towards the horizon.

Our author [Joel Achenbach] confuses reason with science. They aren't the same. For example, the article attempts to defend GMOs, claiming they have been proven not to harm human health through science. This is a misunderstanding of how science works. In order to prove this, millions of scientific experiments would need to be performed, which is beyond the scope of our ability. Achenbach even cedes this point, noting that science is, at best, a work in progress, and can't ever be sure about anything.

Achenbach also notes a positive correlation between the highly educated and doubt in the establishment. He seems to believe that the American populace should trust the experts, because the world is too complicated to ever come to our own opinions on. I think the world is complicated, but that's precisely why I think we need to avoid expert opinion, do our own research, and come to our own understanding.

Also, Achenbach claims that the web has democratized information. The web has changed very little about the distribution of information. Most Americans continue to get their news and ultimately their opinions from mainstream media, whether that be from Fox on the right or the New York Times on the left. Just like wealth distribution in this country, a very small percentage of Americans utilize the potential of the internet. And who knows, in a few years our internet might be locked down just like it is in many other countries.

Ironically, the article laments the fall of National Geographic as being a deeply respected American institution. My partner's father was under their employ for almost half a century, joining them at their pinnacle and leaving them when he'd given up on their relevance. They haven't kept with the times, and this article is ultimately just another example of their increasing irrelevance.

To make a broad, sweeping, and indefensible statement, we're passing from the Age of Separation [or Reason, depending on how you define it] into the Age of Interbeing. This new age is something entirely new. Although we can gain insights from looking back over the past 6,000 years of recorded history, this new age puts us into the next 6,000 year period [according the the Shivapuri Baba], which will step away from the values of progress and separation. By no means will this transition be over within a decade. I think it'll be at least a century, maybe longer, if we put the beginning of the transition at the Summer of Love.

The piece comes off as propaganda. The article could be a marketing piece for Monsanto.

As an after-note, if you too are wondering what underlying forces are causing this trend towards a general atmosphere of distrust, I highly recommend Kirby Ferguson's production, "This Is Not a Conspiracy Theory."

0 notes

Text

Leaving Facebook

In 2007 I was a student at a performing arts school. I’m a photographer, and no one was taking and sharing photos of shows [we had almost one show a week during the academic year]. My peers encouraged me to join Facebook, because they said it would be the perfect venue for me to share my photos. I was quite reluctant. I’ve always been a bit of a Luddite in the traditional sense of the word. Eventually I caved, due to a lack of better options.

They were right. Over the next few years, I uploaded over 100,000 photos to Facebook [I had close to 1,000 albums, many with hundreds of pictures in them]. I had literally millions of interactions with these photos, between comments, tags, likes, profile pictures, et cetera.

But times have changed. Facebook’s business model sees me and my friends as resources to be exploited. We’re not the client; we’re the raw materials. The clients are advertisers and the intelligence community. If Facebook was a paid, encrypted service, then I might have a different take on things, but that looks nearly impossible at this point.

And I no longer take so many photos. For my artistic stuff, I have a 500px account–a site for dedicated photographers that has extremely high user engagement. And when I’m asked to do a show, a wedding, a shoot, or something else, I can just file-share the photos with the organizers and they can use that material how they see fit.

So I recently left. I deleted [rather than deactivated] my account. And so far, only one person has noticed. Apparently Facebook isn’t that important to many other people either. Maybe half of my close friends either aren’t on Facebook, or don’t use their accounts.

I’ve been actively contemplating this move for over a year now. In the months leading up to my departure, I carefully tracked Facebook’s utility. I had over 1,500 friends on Facebook, but I have over 3,000 contacts in my address book, and almost 500 people through LinkedIn. So it’s not as though I’ll be losing my networks. The one way that Facebook has been valuable is that it supplies me with high-quality alternative news. But news isn’t that important anyways. And I’ve been able to follow a handful of people on Twitter and through email newsletters that get me maybe 80% of what I was seeing before in a fraction of the time, which is good enough for me.

I have a number of ethical and practical problems with Facebook.

Facebook replaces real connection. Social media is anti-social. Rather than hang out with someone in-person, give them a call, or connect through a lengthy email or letter, Facebook encourages me to browse a few photos, give them a few likes, and leave things at that. Instead of directly interacting with my friends, I end up interacting with a certain curated image. In a way, everyone on Facebook becomes a celebrity, looking for fame, but lacking any true relationships. Not only that, but which posts get displayed and to whom is a total lottery. So even when I do have something that seems to makes sense to share on Facebook [such as that I’m going to be visiting a certain city and wondering who’s in town], many of the people that should be seeing that post never do.

I get that Facebook does have some unique utility for some people. But between a cell phone, text, and email, I can accomplish just about everything I used to do through Facebook. In addition, even for people that find Facebook useful, I don’t believe that the utility is worth the condonation of the large-scale human rights abuses Facebook performs.

What about people with Pages? I had a ton of them, and handed over administration of active pages to others years before leaving. On a large scale, I find email newsletters to be more useful and less time-consuming than Facebook pages. I’ve whittled down those that matter to maybe a dozen organizations, and I get, on average, one email a month from each of these. On Facebook, on the other hand, I “liked” over a thousand pages, and haphazardly got useful information from these pages while investing a lot of time hanging out on Facebook to be around to see these updates. In addition, whereas an organization might send out one email update a month, they’ll post something new to their Facebook almost every day; the quality of Facebook’s content is junk compared with email newsletters.

In summary: Facebook’s pretty bad; you should leave.

Next Steps

Recently I've been thoroughly researching how to go about assembling a secure suite of communication technologies. So far this process is incomplete. I've decided that moving incrementally is better than taking no actions at all, so this is what I've done for now. In a few months I'll probably put out a similar post with other discoveries and actions I've taken towards this end.

Further Reading

Get Your Loved Ones Off Facebook

NSA Files

Data Responsibility

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Money and Separation

I came across these two related articles today:

Separation and Addiction

Loneliness

The first suggests that addiction is a side effect of a lack of connection. The second suggests that isolation is a severe health risk.

Many believe that those with privilege/financial wealth are more likely to feel isolated [Robin William's suicide comes to mind].

I think there's a dynamic connecting all of these threads:

Money is created through separation. The reason that money can be used for anything is that it is abstract. And the only way to get an abstract entity in this world is violence: the removal of something from its context. Financialization [bringing things from this world into the world of money] has side effects on human participants such as depression and addiction.

So if we just go ahead and use money as it's usually used, we see horrible results. It's only when we try using money in new ways within a strong community of support that we see healthy dynamics surrounding money.

0 notes

Text

The Tragedy of the Market

I've recently been listening to David Bollier's "Think Like a Commoner," and he's got me thinking in some interesting directions.

Many people have heard of the "Tragedy of the Commons" thought experiment, coined by a man named Garrett Hardin in 1968. The issue with it? It's not about commons. It actually more closely resembles markets.

Which has gotten me thinking: conventional economics builds models based on supposedly "rational" human beings. And yet this is a terrible misuse of the word. An economy based on the principle of rationality wouldn't perpetuate global warming or racism. These behaviors are more adequately described as sociopathic, or even psychopathic. If you're a layperson, next time you hear an economist use the word rational, try substituting sociopathic, and see if that might better suit the context.

Is it coincidental that conventional economics leads to irrationality? I propose that it's unavoidable.

Natural systems have built in feedback loops. What is the economy? A layer of feedback on top of natural channels. And these additional feedback loops are inherently contrary to natural allocations of resources [otherwise we wouldn't need them]. In the short-term, the economy can cause anti-social and anti-ecological patterns. In the long term, nature always wins, but we might be able to keep trying to fool ourselves a bit longer.

0 notes

Text

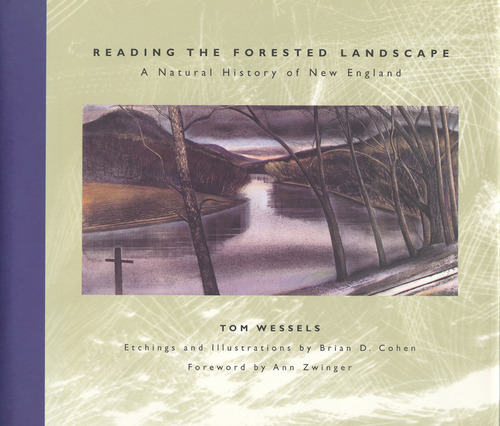

Reading the Forested Landscape

The following is a book review of "Reading the Forested Landscape: A Natural History of New England." It was written by Tom Wessels and published in 1997.

I loved reading this book! I feel very at home in New England, and this book deepened this sense. I'm an amateur landscape-reader, and found that this book helped me know what's next in building this skill. By becoming more observant, we grow closer to our environment.

Interesting Tidbits

Almost all of the stone walls in New England were build between 1810 and 1840, and were a minimum of four-and-a-half feet tall! The traditional method of fencing used split rails, but deforestation led to a shortage of lumber for such use. This period was known as Sheep Fever, as a severe economic bubble formed around merino wool. New England became home to millions of merino sheep during this brief period.

Riparian areas were home to forests similar to the Redwoods in California: four-hundred-plus-year-old white pines over two-hundred feet tall.

Beavers went extinct for a while in New England due to the fur trade. Along with Native Americans, beavers were the other primary keystone species, transforming landscapes with their lifestyles.

New England was covered by a glacier up until 15,000 years ago. And yet we didn't arrive at today's rough forest composition until 3,000 years ago!

Sugar maples are susceptible to crown die-off due to salt. This is quite unfortunate, as the largest and most-accessible sugar maples tent to be adjacent to roads.

Types of disturbance:

Fire

Pasturing

Logging

Blights

Beaver activity

Blowdowns

0 notes

Text

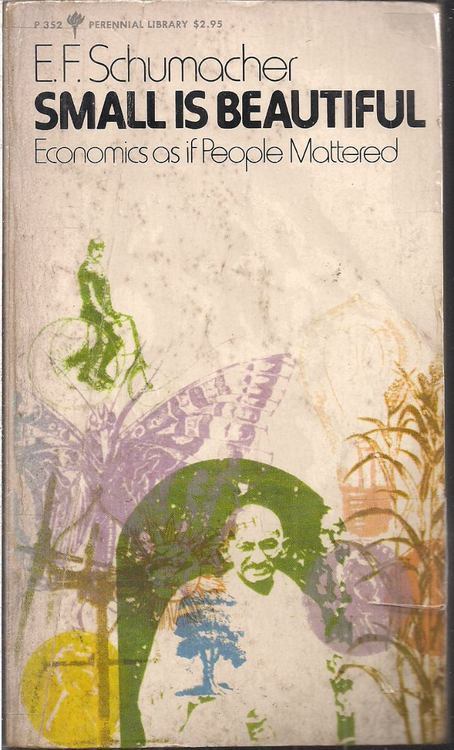

Small is Beautiful

This is a book review of E. F. Schumacher's 1973 title, "Small is Beautiful: Economics as if People Mattered."

Author

With the reputation that preceded the book, I thought that Schumacher was some kind of hippy. And after reading it, I still think that he is. But he was also an "insider," serving on the British Coal Board for many years.

Background

I've been attending Slow Money's National Gatherings since 2010. It seems like every time I see Woody Tasch speak [its founder], he quotes Schumacher. I recently went to the opening of Slow Money Vermont, and heard yet another Schumacher reference. So I finally went to one of my local used-book stores and picked up a copy. Fittingly, I finished the book on the plane to the Louisville National Gathering about a week ago.

Reception

I can say that the book is as good as Woody would have you believe. I'll just start diving in with excerpts:

I think it was the Chinese, before World War II, who calculated that it took the work of thirty peasants to keep one mane or woman at university. If that person at the university took a five-year course, by the time he had finished he would have consumed 150 peasant-work-years.

Which he follows with two quotes:

I sit on a man’s back, choking him, and making him carry me, and yet assure myself and others that I am very sorry for him and wish to ease his lot by any means possible, except getting off his back. - Leo Tolstoy

Much will be expected of the man to whom much has been given. More will be asked of him because he was entrusted with more. - St. Luke

This degree of perspective, broad yet deep, often isn't achieved. The peasant-year analogy is no different today. Although the relationships are less obvious. The US has the biggest economy in the world not because of our own "production," but because of how we take advantage of people and natural resources in developing countries. Each year of my life as an American might be eating up something on the magnitude of thirty years of the lives of those in Brazil, China, or Africa.

As the violence is forgotten, so is the privilege. If a comparison was warranted, the ways we eat up fossil fuel might be argued to be even more irresponsible; at least people are renewable.

Schumacher sees beyond all of this to the underlying systems. Here's one of his inclusions that hints at this:

War is a judgement that overtakes societies when they have been living upon ideas that conflict too violently with the laws governing the universe…Never think that wars are irrational catastrophes: they happen when wrong ways of thinking and living bring about intolerable situations. - Dorothy L. Sayers

And, more to the point:

If I hold a rather negative opinion about the usefulness of “automation” in matters of economic forecasting and the like, I do not underestimate the value of electronic computers and similar apparatus for other tasks, like solving mathematical problems or programming production runs. These latter tasks belong to the exact sciences or their applications. Their subject matter is non-human, or perhaps I should say, sub-human. Their very exactitude is a sign of the absence of human freedom, the absence of choice, responsibility and dignity. As soon as human freedom enters, we are in an entirely different world where there is great danger in any proliferation of mechanical devices.The tendencies which attempt to obliterate the distinction should be resisted with the utmost determination. Great damage to human dignity has resulted from the misguided attempt of the social sciences to adopt and imitate the methods of the natural sciences. Economics, and even more so, applied economics, is not an exact science; it is in fact, or ought to be, something much greater: a brach of wisdom.

My favorite word in this passage is "sub-human." Earlier in the book Schumacher starts sketching out the thresholds between "divergent" [real] and "convergent" [abstract] thinking. Here's an excerpt from Darwin's autobiography:

Up to the age of thirty, or beyond it, poetry of many kinds…gave me great pleasure, and even as a schoolboy I took intense delight in Shakespeare, especially in the historical plays. I have also said that formerly pictures gave me considerable, and music very great, delight. But now for many years I cannot endure to read a line of poetry: I have tried lately to read Shakespeare, and found it so intolerably dull that it nauseated me. I have also lost almost any taste for pictures or music … My mind seems to have become a kind of machine for grinding general laws out of large collections of fact, but why this alone should have caused the atrophy of that part of the brain alone, on which the higher tastes depend, I cannot conceive… The loss of these tastes is a loss of happiness, and may possibly be injurious to the intellect, and more probably to the moral character, by enfeebling the emotional part of our nature.

In other words, Darwin's thought patterns eventually turned him into a machine, unable to access the hallmark emotional center of the human experience.

And today, we too have become machines. Our treatment of economics as a science has converted us all into cogs in the machine, as the cliche goes. Well, it's not that simple; we could get into spirituality. And Schumacher does:

The Buddhist point of view takes the function of work to be at least threefold: to give a man a chance to utilize and develop his faculties; to enable him to overcome his ego-centerness by joining with other people in a common task; and to bring forth the goods and services needed fro a becoming existence…To organize work in such a manner that it becomes meaningless, boring, stultifying, or nerve-racking for the worker would be little short of criminal; it would indicate a greater concern with goods than with people, an evil lack of compassion and a soul-destroying degree of attachment to the most primitive side of this worldly existence. Equally, to strive for leisure as an alternative to work would be considered a complete misunderstanding of one of the basic truths of human existence, namely that work and leisure are complementary parts of the same living process and cannot be separated without destroying the joy of work and the bliss of leisure.

Mid-way through the book Schumacher presents us with some nice axioms:

The amount of real leisure a society enjoys tends to be in inverse proportion to the amount of labour-saving machinery it employs.

The prestige carried by people in modern industrial society varies in inverse proportion to their closeness to actual production.

Throughout the entire book our author confronts the dissonance between our abstract modern cultural constructions and our deeper human attributes. Between the operationalized financial economy and the dynamic natural world. He settles on an integrative perspective, exploiting the polarizing dualism of the mainstream worldview:

Anything we do under the heading of ‘production’ is subject to the economic calculus, and anything we do under the heading of ‘consumption’ is not. But real life is very refractory to such classifications, because man-as-producer and man-as-consumer is in fact the same man, who is always producing and consuming at the same time.

As a systems thinker, he's at home with mythology. "We have become confused as to what our convictions really are.” In other words, failures of civilization are failures of mythology.

In some ways I found the book rather discouraging. If it was published today, many might say it's representative of the cutting edge of alternative economics. And yet it was written over forty years ago. Has our situation improved? Well, the natural world is certainly more strongly in decline. But the bastions of creative culture seem to be growing stronger.

Conclusion

An excellent book about economics, development, and systems thinking. Grounded in cosmology.

0 notes

Text

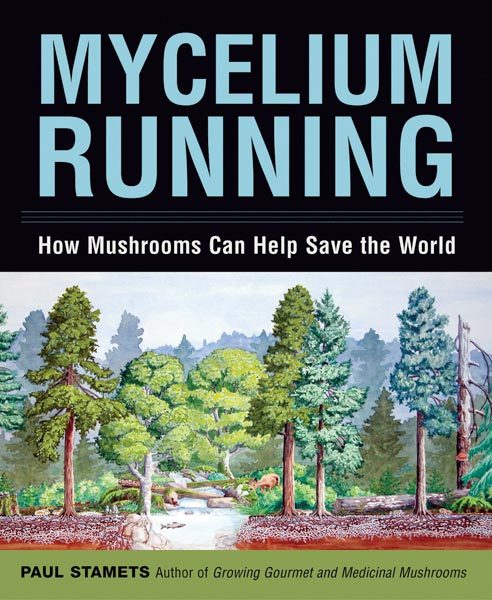

Mycelium Running

This post is a book review of Paul Stamets' 2005 book, "Mycelium Running: How Mushrooms Can Help Save the World."

Overview

Four kinds of mushrooms:

Saprophytic - decomposers [primary, secondary, tertiary]

Parasitic - “blights of the forest or agents for habitat restoration?"

Mycorrhizal - “fungus and plant partnerships"

Endophytic - mutualistic, fungal partnerships

Mycorestoration:

Mycofiltration - filtering out manure

Mycoforestry - preventing parasitic fungi with other fungi

Mycoremediation - restoring logging roads, digesting diesel fuel, collecting radiation and heavy metals

Mycopesticides - ant-proofing your house

Growing Mycelia and Mushrooms:

Inoculation Methods: Spores, Spawn, and Stem Butts

Cultivating Mushrooms on Straw and Leached Cow Manure

Cultivating Mushrooms on Logs and Stumps

Gardening with Gourmet and Medicinal Mushrooms

Nutritional Properties of Mushrooms

Magnificent Mushrooms: The Cast of Species

Reception

I absolutely loved this book. It's basically an overview of what a first grader should know about the fungal kingdom. Unfortunately, probably only about 1% of the US population have a rudimentary understanding of mushrooms.

For people who like science: this is your book. Genus and species. Scientific papers. This book is full of science.

For permaculturists: you should read this too. Restoration agriculture. Bioremediation. Ecology.

And for herbalists and healers: mushrooms are your allies! Mushrooms can cure pretty much anything.

Mushrooms are the Wild West right now. Compared to other sectors of the natural world, we know almost nothing about them. Join the pioneers and become a mycologist!

In summary, the subtitle of this book is right on; mushrooms could save the world.

79 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Anything we do under the heading of ‘production’ is subject to the economic calculus, and anything we do under the heading of ‘consumption’ is not. But real life is very refractory to such classifications, because man-as-producer and man-as-consumer is in fact the same man, who is always producing and consuming at the same time.

On page 112 of “Small is Beautiful: Economics as if People Mattered,” by E. F. Schumacher

0 notes