#youre just living your life and then BOOM THIS ENTIRE PLANET IS INCINERATED IN AN INSTANT

Text

star wars needs more actual space things. especially space horror. i know i'm biased but outer space is fucking terrifying. the characters need to reckon with that more. come face to face with the horrifying ordeal of being mortal

#you're on some remote planet and your hyperdrive breaks. guess what you're fucking stuck forever#LIKE if boba and fenenc hadnt shown up on tython. DIN WOULD BE STRANDED THERE#FOR WHO KNOWS HOW LONG. THATS SO TERRIFYING#i mean . assuming tython is like uninhabited#although even if there are a few scattered settlements. how the fuck is one guy going to traverse an entire planet on foot#so even if it isnt entirely uninhabited thats still terrible LOL#OR LIKE? GAMMA RAY BURSTS?#youre just living your life and then BOOM THIS ENTIRE PLANET IS INCINERATED IN AN INSTANT#do u think planets need to be evacuated sometimes because a nearby star is going supernova#or like. neutron star mergers. black hole mergers!!#pulsars. magnetars. etc etc#brot posts#sw posting#people ask me if i would ever want to be an astronaut and it's like#no fucking thanks lol. i love outer space but i am admiring it from afar. <3

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hi! Get ambushed with more scenes I’m never going to do anything with but that I kinda like as I explore my characters. Today on showcase: Adilus Dend

The ship was on fire, and the sensation of suspended death as the floor listed towards the planet brought was all too familiar to Adilus’s feet.

He grabbed a person by the arm as the man ran past. “Go to the shelters. Make sure the children make it to the escape pods.” He stared into the man’s eyes until certain the job would be done.

He took hold of the railing, using it to balance out his bad knee and hip as he made his way towards the bridge, fighting the tide of people streaming for the chance at life the pods held, as more of the ship succumbed to the void. A rolling volley struck the hull, and the drifting for the surface got faster. They were on course to plunge right into the planetary shields. The ship would be incinerated as it passed through, leaving nothing but droplets of molten metal to free fall to the surface.

He fumbled in his uniform for a key to the door, cursing his once-nimble fingers as he did. He pried it out, slid it over the barrier, and barged in. Surely enough, nobody was at their posts. Adilus rolled his eyes. Civilian liners. The slightest sign of trouble and discipline evaporated.

He made his way to where the propulsion panel usually was, only to find it contained a bank of environmental control modulators. The old bridge models worked perfectly, fine, why were they changing things around, when an old fool might be the only thing between a ship and disaster? He huffed.

Adilus found the proper controls on the far side of the room, and by the time he got to a chair his hip was fit to buckle. Instinct said to put all power to the forward engines, attempt to reverse the descent. Experience and training told him to make a bank job of it. He smiled, recalling the battle over Ghor, back when he still fought for the Empire. Simpler times. Darker times, but simpler. He shook himself. This was no time for reminiscing.

He pulled power from the stabilizing engines--stabilizing the ship wasn’t much good when it was actively in a planet’s gravitational lock, which would stabilize it just fine, and also falling. The diverted power was sent entirely to the right side of the ship, trying to turn their descent into an arc, at which point he could switch course and put them into orbit. If this worked, that is. If he failed, well, one sentimental old man was hardly a great loss. He could at least buy time for the rest of the people to get to escape pods.

He felt a tugging at his shirt, and his hands faltered on the controls as his eyes looked down away from the screen. The two watery brown eyes that met his belonged to a child, and now his heart faltered.

“Hey there little guy. Where’s your parents?”

“The-” the boy sniffed- “the boom...”

Adilus knew those words. He’d heard them before, from other distraught little ones, in the aftermath of other firefights. They were probably watching the stars out of a viewing port when the attack struck. As if cued by his thoughts, another rolling volley hammered through the ship. Another few and there wouldn’t be any engines left to work with. The child resumed sobbing, and suddenly Adilus was in grandfather mode, working his way out of the chair and, against his hip and knee’s protest, crouching down to look the child in the eyes, at the boy’s level. “I know this is all terribly too much, but we’ll get you back to them.” He reached out, almost choking on the lie, pulling the boy closer, letting the child bury his face in the old soldier’s broad shoulders. “Do you know how to get to the escape pods?” He knew the answer as soon as he asked the question, thinking of the maze of corridors it took to get there. And the kid was hardly in any state to wander off alone, with the alarm systems blaring as the scent of stale air crept in, the vents and doors across the ship sealing shut to try and prevent the air from leaking out.

The little face confirmed his worries with an emphatic shake of the head.

Adilus wrapped his arms around the boy, remembering his purpose in the room, lifting him up, again despite his knee and hips’ staunch protests. He retook his seat in the chair at the control panel, searching for something to do, anything to slow the ship’s descent. He could see little dots, support crew ships, maybe some planetary defense to fight the raiders, taking off on the ground. There was no way they would get there in time, not without turning off the planetary shield, and no sensible administrator would sign off on that with a Nebula-class warship actively firing on a civilian cruiser just above.

Adilus rested his hand on the little boy’s back, moving it in slow circles, as the tears continued to soak into his shoulder.

“Mister sir?” The little boy blubbered, “are we gonna crash?”

Dark sadness gripped Adilus’s heart. “It won’t be so bad.” It was a nonanswer, and they both knew it, even if the boy didn’t know the word for it. The little face buried itself back in his shirt.

Adilus felt another wave of shots rock the ship, and sure enough, the engine diagnostics were reporting no fewer than seventeen critical failure points. They were dead in the expanse. Or rather, they were without power. A jarring screech as the ship, build for space, began to groan louder under the force of gravity from the planet made it very clear they were moving. Just not in a good direction.

There was nothing more Adilus could do. He leaned back in his chair, trying to use his large form to offer the child what little comfort he could. It could never be enough. He closed his eyes.

It was all his fault. The Syndicate had been emboldened by him and Vendale, and now they were here, attacking a core world, a wealthy one, wealthy enough to afford a planetary shield no less, probably because of some tip that he, Adilus Dend, newly retired Grand Admiral of the Ravens, Chief Executive Emeritus of Dend Industries, former General of the Imperial Navy and the Galactic Confederation, one of the least valuable but most symbolic targets in the galaxy, was on board a little-armored and unarmed civilian cruiser. He could only hope that whatever rat let the secret loose would have his just penance, but he knew there was no justice in the galaxy. If not wasn’t for the little boy in his arms, why should there be any for him? He’d lived a good life. He’d used his luck already.

Dend had been counting the seconds until another barrage. It should have come already. He opened his eyes, looked out the massive window, and almost didn’t get time to register what he saw there before he was thrown out of his chair, the ship’s sudden fall halted by a massive tow cable, mounted to the rear of a liberated freight liner. The Stalemate was with them, gun banks seemingly on fire, and missiles were streaking though the intervening space between it and the Syndicate warship. The little escape pods were all clear and flying towards the planetary shield gate. Dend felt like standing up and whooping a victory cry, but he didn’t want to disturb the boy, who was now looking up, chin still firmly tucked into Dend, but he was looking up.

Dend stood slowly instead, hip pain still there but forgotten, and hobbled to the communications board, sending a hailing signal to the tow ship.

The captain of the vessel accepted the signal, and the smiling eyes of Commander Brynn met Adilus’s.

“Sorry it’s not much of a rescue, Grandpops, but we do what we can.” Brynn turned, shouting some orders to her own people, swarming around the ship.

“I’m just glad you’re here, my girl.”

“Don’t get sappy just yet, save that for when you’re back at the Roost. You should’ve seen Pops when when we got word you were under attack. “Retired my bullet,” “Get out there and teach those wastes of oxygen how things work in my stellar space,” “When that old man gets back here I’m never letting him retire again,” you know.”

Adilus settled back into his chair, putting his hand back on the little boy’s back, moving it in those slow circles again. “Yes, I do know.” He smiled. Retirement didn’t suit him anyway. “I do know.”

#scifi#old man doesn't wanna retire#I'm so sorry to everybody that follows me#but also I've never claimed to have a consistent theme and never will#this is a personal blog and I fuck around and post random shit quite a bit#anyway meet my second favorite old man

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

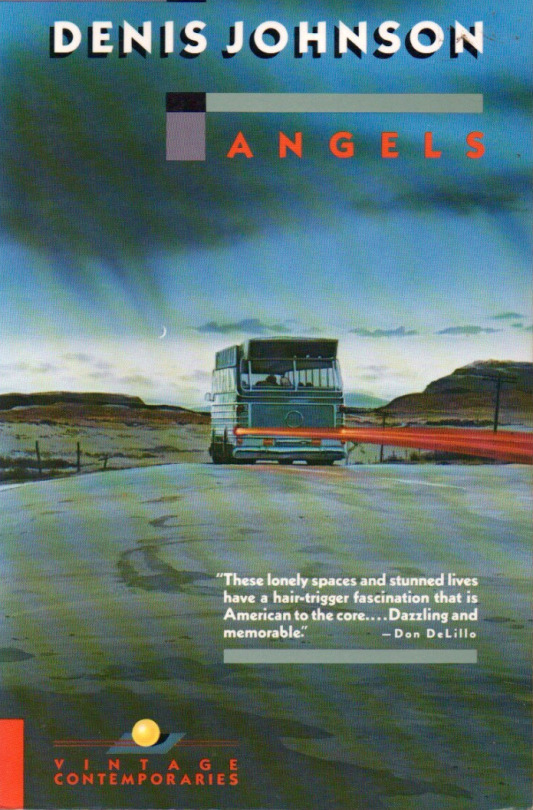

Angels by Denis Johnson

Of course Pittsburgh was colder and wearier than Oakland, but it wasn’t any filthier. What it seemed to lack that Oakland had was a sky. By day it looked like old newspapers had been pasted over the sun, and after dark the universe ended six feet above the tallest lamp. There were no dawns or sunsets in Pittsburgh; there were no heavens in which they might occur. (p. 18)

***

He rested with his back flat against a building, and had the sensation of lying down when he was standing up. The streets swung back and forth like a bell. No doubt about it, it was a dizzy life. Something was missing here. When he was dry, he believed it was alcohol he needed, but when he had a few drinks in him, he knew it was something else, possibly a woman; and when he had it all—cash, booze, and a wife—he couldn’t be distracted from the great emptiness that was always falling through him and never hit the ground. (p. 37)

***

Holding the can of beer between her knees, she took an amphetamine capsule from an envelope in her shirt pocket—a Black Beauty, courtesy of the youngest of the Houston brothers—and chewed it slowly. She’d gotten so she liked to break them up with her teeth, liked the bitter taste, the black taste—it was black beauty, wasn’t it? All I eat anymore.

The rear-view mirror returned her face to her, cavern-cheeked and bug-eyed, and when she drew her lips apart she looked into the image of canine hysteria, the teeth yielding a purple tint from days on end of red wine. Almost like a physical reality, somewhere in the upper left quadrant of her chest there lurked true knowledge of what she was doing; and in the remaining three-quarters of her psyche the word on chemical abuse was Fuck You. A person needs pills for the world and wine for the pills. Anything further I’ll let you know. (p. 106)

***

Wearing long trenchcoats, carrying shotguns and rifles, men on horses rode along a dirt road, passed into a forest, and made for a cabin in the clearing. Burris wished he could engage himself in their story—a story of men with guns, exactly like his own, except that nobody going to the movies ever guessed the essential, gigantic truth of it, which was that these men would trade everything they had for one clear minute of peace. (p. 128)

***

It wasn’t the punishment that hurt—it was the punishment’s failure to be enough. (p. 141)

***

The beat of things, their steady direction, had dissolved into nothing—this room wasn’t happening then, it isn’t happening now; maybe it’s a dream of what’s going to happen or what will happen never. The sound of her own voice injures her like a shock of electricity through her ears, but screaming herself to hoarse exhaustion is the only reprieve from breathing.

She looked up out of her voice and saw the angel.

He will have ears like a cartoon of organic growth. he is yellow with light but covered with mobile shadows, animated tattoos. His face kept changing. His voice will come from far off, like a train’s. His body is steady and beautiful and hairless, the wings white, incinerating, and pure, but the head changes rapidly—the head of an eagle, a goat, an insect, a mouse, a sheep with spiraling horns that turn and lengthen almost imperceptibly—and the entire message had no words. The entire message will be only the beat and direction of time. Yes is Now.

The angel who says, “It’s time.”

“Is it time?” she asked. “Does it hurt?” He will have the most beautiful face she has ever seen.

“Oh, babe,” The angel starts to cry. “You can’t imagine,” he said. (p. 157)

***

And while he paid no attention to what he feared, it happened. Slowly the time had been transformed, in the usual way that the passing of an evening transforms a street corner and a place of simple commerce there, like this gas station. And then abruptly but very gently something happened, and it was Now. The moment broke apart and he saw its face.

It was the Unmade. It was the Father. It was This Moment.

Then it ended, but it couldn’t end. Now there was a world in which a man got into his blue Volkswagen, thanking the attendant as he did so, and closed its door solidly. It was a world in which one fluorescent lamp arched out over the service station, and another lay flat on the pool of water and lubricant beneath it. It was a world he might be lifted out of by a wind, but never by anything evil or thoughtless or without meaning. It was a world he could go to the gas chamber in, and die forever and never die.

There was some daylight now. He looked through wire mesh, intended to withstand the heat of a blowtorch, at a world awash in a violet peace. He felt as if his feet had found the shore. This is your eternal life. This is for always. This happens once. (pp. 158-59)

***

That he might spend only three weeks in prison now seemed one of the worst parts of his punishment. It was inside the level, uniform dailiness of these surroundings that the wonder of life assailed him. Minute changes in the desert air, the gradual angling of supposedly fixed shadows along the dirt as the seasons changed, the slow overturn of all the familiar people around him—they spoke of a benevolent plot at the heart of things never to stay the same. But on the streets events jumped their lanes. Everything turned inside out, flew back in his face, left him wide-eyed but asleep. He’d never known himself on the streets. It was here at the impossible core of his own accursedness that they were introduced. (pp. 177-78)

***

“Talking Richard Wilson Blues,” he said. “By Richard Clay Wilson.” And he read in a Baptist sing-song:

I felt like a man of honor and substance,

but the situation was dancing underneath me—

once I walked into the living room at my sister’s

and saw that the two of them, her and my sister,

had turned sometime behind my back not exactly

fatter, but heavy, or squalid, with cartoons

moving across the television in front of them,

surrounded by laundry, and a couple of Coca-Colas

standing up next to the iron on the board.

I stepped out into the yard of bricks

and trash and watched the light light

up the blood inside each leaf,

and I asked myself, Now what is the rpm

on this mother? Where do you turn it on?

I think you understand how I felt.

I’m not saying everything changed in the space

of one second of seeing two women, but I did

start dragging her into the clubs with me. I insisted

she be sexy. I just wanted to live.

And I did: some nights were so

sensory I felt the starlight landing on my back

and I believed I could set fire to things with my fingers—

but the strategies of others broke my promise.

At closing time once, she kept talking to a man

when I was trying to catch her attention to leave.

It was a Negro man, and I thought of black limousines

and black masses and black hydrants filled

with black water. I thought I might smack her face, or spill

a glass,

but instead I opened him up with my red fishing knife

and I took out his guts and I said, “Here they are,

motherfucker, nigger, here they are.”

There were people frozen around us. The lights had just come on.

At that moment I saw her reading me and reading me

from the end of the world where I saw her standing,

the way the sacred light played across her face.

Right down the middle from beginning to end

my life pours into one ocean: into this prison

with its empty ballfield and its empty

preparations. If she ever comes to visit me

to hell with her, I won’t talk to her.

God kill you all. I’m sorry for nothing.

I’m just an alien from another planet.

I am not happy. Disappointment

lights its stupid fire in my heart,

but two days a week I staff

the Max Security laundry above the world

on the seventh level, looking at two long roads

out there that go to a couple of towns.

Young girls accelerating through the intersection

make me want to live forever,

they make me think of the grand things,

of wars and extremely white, quiet light that never dies.

Sometimes I stand against the window for hours

tuned to every station at once, so loaded on crystal

meth I believe I’ll drift out of my body.

Jesus Christ, your doors close and open,

you touch the Maniac Drifters, the Fireaters,

I could say a million things about you

and never get that silence. That is what I mean

by darkness, the place where I kiss your mouth,

where nothing bad has happened.

I’m not anyone but I wish I could be told

when you will come to save us. I have written

several poems and several hymns, and one

has been performed on the religious

ultrahigh frequency station. And it goes like this. (pp. 191-93)

***

He was in the middle of taking the last breath of his life before he realized he was taking it. But it was all right. Boom! Unbelievable! And another coming? How many of these things do you mean to give away? He got right in the dark between heartbeats and rested there. And then he saw that another one wasn’t going to come. That’s it. That’s the last. He looked at the dark. I would like to take this opportunity, he said, to pray for another human being. (p. 207)

***

It was Fredericks’s understanding that the prisoners had a story: that each night for months, at nine precisely, a light had burned in a window in the town, where the men on one cellblock’s upper tier could see it and wonder, and imagine, each one, that it shone for him alone. But that was just a story, something that people will tell themselves, something to pass the time it takes for the violence inside a man to wear him away, or to be consumed itself, depending on who is the candle and who is the light. (p. 209)

0 notes