Text

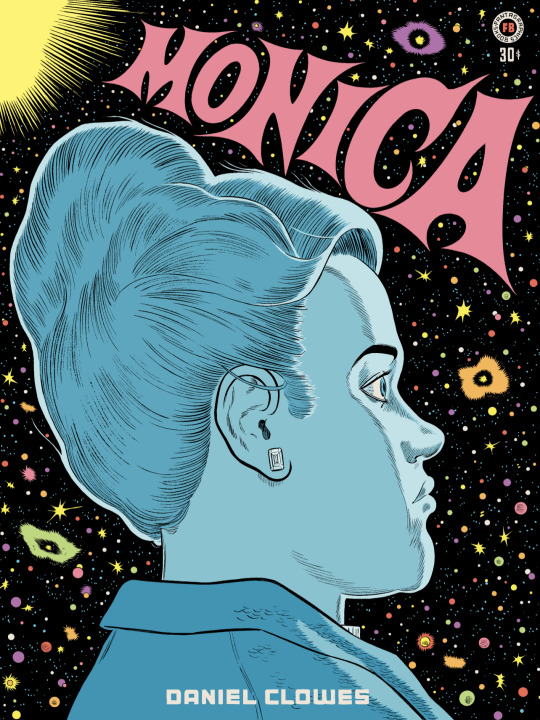

Source by Mark Doty

Manhattan: Luminism

The sign said immunology

but I read

illuminology: and look,

heaven is a platinum latitude

over Fifth, fogged result

of sun on brushed

steel, pearl

dimensions. Cézanne:

"We are an iridescent chaos."

•

Balcony over Lexington, May evening,

fog-wreath'd towers,

gothic dome lit from within,

monument of our aspirations

turned hollow, abandoned

somehow. And later, in the florist's window

on Second Avenue, a queen's display

of orchid and fern, lush heap

of dried sheaves, bounty of grasses ...

What's that? Mice

far from any field

but feasting.

•

The sign said

K YS MADE,

but what will op n,

if the locksmith's

lost his vowel

—his entrance,

edge, his means

of egress—

which held together

the four letters

of his trade?

City of consonants,

city of locks,

and he's lost

the E.

•

(A Mirror in the Chelsea Hotel)

Here, where odd old things have come to rest

—a lamp that never meant

to keep on going, a chest

whose tropical veneers

are battered and submissive—

this glass gives the old hotel room

back to itself in a warmer atmosphere,

as if its silver were thickening,

a gathering opacity held here,

just barely giving back ...

This mirror resists what it can,

too weary for generosity.

As if each coming and going,

each visitor turned, one night

or weeks, to check a collar

or the angle of a hat, left some residue,

a bit of leave-taking preserved in mercury.

And now, filled up with all that regard,

there is hardly any room for regarding,

and a silvered fog fills nearly all

the space, like rain: the city's lovely,

crowded dream, which closes you

into itself like a folding screen.

•

Almost nightfall, West 82nd,

and a child falls to her knees

on the cement, and presses

herself against the glass

of the video store,

because she wants to hold her face

against the approaching face,

huge, open, on the poster

hung low in the window,

down near the sidewalk:

an elephant walking toward

the viewer, ears wide to the world.

She cries out in delight,

at first, and her mother

acknowledges her pleasure,

but then she's still there,

kneeling, in silence, and no matter

what the mother does or says

the girl's not moving,

won't budge, though her name's

called again and again.

Could you even name it,

that longing—which suddenly seems

to rule these streets,

as if the underlying principle

of the city had been drawn up

from beneath the pavement

by a girl who doesn't know

any better than to insist

on the force of her wish

to look into the gaze which seems

to go on steadily coming toward her,

though of course it isn't moving at all.

•

I woke in the old hotel.

The shutters were open

in the high, single window;

the light gone delicate, platinum.

What had I been dreaming,

what would become of me now?

There were doves calling,

their three-note tremolo

climbing the airshaft

—something about the depth

of that sound, where it reaches in you,

what it touches. You've been abraded,

something exchanged or given away

with every encounter, on the street,

the train, something of you lost

to the bodies that unnerved you,

in the station, streaming ahead,

everyone going somewhere certain

in the randomly intersecting flow

of our hurry, until you could be anyone,

in the furious commingling...

But now you're more awake, aren't you,

and of course these aren't doves,

not in the middle of Manhattan;

a little harsher, more driven,

these pigeons, though recognizable

still in the pulse of their throats

the threnody of their kind, rising

to you or to that interior ear

with which you are always listening,

in the great city, where things are said

to no one, and everyone, and still

it's the same... You were afraid

you were edgeless, one bit

of light's indifferent streaming,

and you are—but in a way you also

are singled out, are, in the old sense,

a soul, because you have heard

the thrilling, deep-entering rumple

and susurrus of the birds, and now

a little cadence of sun in motion

on the windowsill's bricked edge,

where did it come from?

Moving with the same ripple... As if,

audible in the ragged yearning,

visible in this tentative assertion of sun

on the lip of a window in Chelsea,

is a flake of that long waving

long ago lodged in you. All this light

traveled aeons to become 23rd Street,

and a hotel room in the late afternoon

—the singular neon outside already

warm and quavering and you in it,

sure now, because of the song

being delivered to you, dealt to you

like an outcome, that there is

something stubborn in us

—does it matter how small it is?—

that does not diminish.

What is it? An ear, a wave?

Not our histories or who we love

or certainly our faces, which dissolve

even as were living. Not a bud

or a cinder, not a seed

or a spark: something else:

obdurate, specific, insoluble.

Something in us does not erode.

***

Paul's Tattoo

The flesh dreams toward permanence,

and so this red carp noses from the inked dusk

of a young man's forearm as he tilts

the droning burin of his trade toward

the blank page of my dear one's biceps

—a scene framed, from where I watch,

in an arched mirror, a niche of mercuried glass

the shape of those prosceniums in which still lifes

reside, in cool museum rooms: tulips and medlars,

oysters and snails and flies on permanently

perishing fruit: vanitas. All is vanitas,

for these two arms—one figured, one just beginning

to be traced with the outline of a heart—

are surrounded by a cabinet of curiosities,

the tattooist's reflected shelves of skulls

—horses, pigs?—and photos of lobes and nipples

shocked into style. Trappings of evil

unlikely to convince: the shop's called 666,

a casket and a pit bull occupy the vestibule,

but the coffins pink and the hellhound licked

our faces clean as the latex this bearded boy donned

to prick the veil my lover's skin presents

—rent, now, with a slightly comic heart,

warmly ironic, lightly shaded, and crowned,

as if to mean feeling's queen or king of any day,

certainly this one, a quarter-hour

suddenly galvanized by a rippling electric trace

firing adrenaline and an odd sense of limit

defied. Not overcome, exactly; this artist's

filled his shop with evidence of that.

To what else do these clean,

Dutch-white bones testify?

But resistant, still, skin grown less subject

to change, ruled by what is drawn there:

a freshly shadowed corazón

now heron-dark, and ringed

by blue exultant bits of sweat or flame—

as if the self contained too much

to be held, and flung out droplets

from the dear proud flesh

—stingingly warm—a steadier hand

has raised into art, or a wound,

or both. The work's done,

our design complete. A bandage,

to absorb whatever pigment

the newly writ might weep,

a hundred guilders, a handshake, back out

onto the street. Now all his life

he wears his heart beneath his sleeve.

***

Source

Id been traveling all day, driving north

—smaller and smaller roads, clapboard houses

startled awake by the new green around them—

when I saw three horses in a fenced field

by the narrow highway's edge: white horses,

two uniformly snowy, the other speckled

as though he'd been rolling in flakes of rust.

They were of graduated sizes

—small, medium, large— and two stood

to watch while the smallest waded

in a shallow pond,

tossing his head and taking

—it seemed unmistakable—delight

in the cool water around his hooves

and ankles. I kept on driving, I went into town

to visit the bookstores and the coffee bar,

and looked at the new novels

and the volumes of poetry, but all the time

it was horses I was thinking of,

and when I drove back to find them

the three companions left off

whatever it was they were playing at,

and came nearer the wire fence—

I'd pulled over onto the grassy shoulder

of the highway—to see what I'd brought them.

Experience is an intact fruit,

core and flesh and rind of it; once cut open,

entered, it can't be the same, can it?

Though that is the dream of the poem:

as if we could look out

through that moment's blushed skin.

They wandered toward the fence.

The tallest turned toward me;

I was moved by the verticality of her face,

elongated reach from the ear-tips

down to white eyelids and lashes,

the pink articulation

of nostrils, wind stirring the strands

of her mane a little to frame the gaze

in which she fixed me. She was the bold one;

the others stood at a slight distance

while she held me in her attention.

Put your tongue to the green-flecked

peel of it, reader, and taste it

from the inside: Would you believe me

if I said that beneath them a clear channel

ran from the three horses to the place

they'd come from, the cool womb

of nothing, cave at the heart

of the world, deep and resilient and firmly set

at the core of things? Not emptiness,

not negation, but a generous, cold nothing:

the breathing space out of which new shoots

are propelled to the grazing mouths,

out of which horses themselves are tendered

into the new light. The poem wants the impossible;

the poem wants a name for the kind nothing

at the core of time, out of which the foals

come tumbling: curled, fetal, dreaming,

and into which the old crumple, fetlock

and skull breaking like waves of foaming milk ...

Cold, bracing nothing, which mothers forth

mud and mint, hoof and clover, root-hair

and horse-hair and the accordion bones

of the rust-spotted little one unfolding itself

into the afternoon. You too: you flare

and fall back into the necessary

open space. What could be better than that?

It was the beginning of May,

the black earth nearly steaming,

and a scatter of petals decked the mud

like pearls, everything warm with setting out,

and you could see beneath their hooves

the path they'd traveled up, the horse-road

on which they trot into the world, eager for pleasure

and sunlight, and down which they descend,

in good time, into the source of spring.

0 notes

Text

Mordechai Schamz by Marc Cholodenko, translated by Dominic Di Bernardi

. . . . In conclusion, he concludes, one hardly is, and the little that one is, consists of what one is not. (p. 4)

***

While he is watching the passing cloud, which decomposes and recomposes upon itself, and again decomposes, constantly, up in the high wind, Mordechai Schamz says to himself, thus lending form to the discomfort inhabiting him: Undoubtedly I am watching this particular cloud but why does it seem to me that I do not really see it? Constantly must I make an effort to keep my eyes attached to it. Or rather I must constantly reattach them for, no sooner settled, they detach themselves. And all this to go where? To arrive back at myself, who yet has dedicated himself to contemplating this cloud. Am I so imperiously important that I do not have it in my power to be detached from myself for a few wretched instants? Important I cannot say; imperiously, there is not one second which, the need arising, would fail to bring me another proof of it. What to do about this, if not to relentlessly redirect toward the relinquished object the interest that is constantly returning to its source? Redirect, have I said? But does not the interest itself rebound upon arriving and immediately head back toward its object? For to attempt to remain within myself I have known nothing more successful than to try to fix myself upon the cloud. Thus I become the pole of attraction of my interest, for apparently it is in its nature to be repelled by the object one wishes to fix it on rather than to be attracted by the object from which one attempts to keep it at a distance. More than a faculty, whose functioning could be said to resemble a crane-grab, it is a back and forth motion regulating our relationship to the world, and we act exactly as do animals deprived of sight which regulate their movements according to the velocity at which the waves they emit are returned by surrounding objects. That strikes me as a security system just as indispensable for us as for them, concludes Mordechai Schamz. Indeed, if my interest were not to come back to me upon touching the object it aims for, I would forget myself and no doubt like to melt into a cloud so beautiful, I would leap through the window and—but who will tell me that in such case I would not be able to fly? (pp. 25-26)

***

Ah! Mordechai Schamz should be given a good slap. That would teach him quite a few things. Given a good slap often—every day, perhaps. Yes, every day he ought to be slapped, but not by just anybody, not by those who, in the street, with the looks of brutes, easily resort to violence, but rather by people who are calm and stable, even gentle, who are admirable, friendly, people he would admire and befriend. The blows attributed to fate would do nothing to humble his vain arrogance; on the contrary, they would harden it. What's needed for such pride are the blows of fellowmen, voluntary, regular, daily blows, nothing less. Maybe then he would learn at last what it is to be a man, among men and with men. These blows ought to signify their contempt and their rejection. However, it could just as well happen that they have the opposite effect. Could not Mordechai Schamz see in them an indubitable proof of their interest in him and even of their solicitude? He would be quite capable of this, and in one way, he would not be wrong. That several persons think about him every day, dedicate a few daily minutes to thrashing him, irrefutably indicates a concern they have about him and verges on the kind of treatment that eventually would risk confirming the morbid attention he pays to himself. No, the contempt should be displayed haphazardly and assume forms as savage as they are unexpected. After all, you can always expect the contempt of those you know, but if a worthy stranger stopped Mordechai Schamz in the street to spit in his face, now that would go a long way in sparking closer interest on his part in the shadowy facets of his personality. Is my vileness so apparent, he would be forced to ask himself, that it commands the indignation of a passerby? Be careful: now it's no longer even an ethical question, but rather one of simple safety. And that would be a good thing, for there are creatures, including Mordechai Schamz, who are happy to pass judgment on themselves and to keep their guilt hidden from the world, as if too precious, undoubtedly, to be shown, or too rare to be understood. (pp. 27-28)

***

It is not unusual for people in the street to smile at Mordechai Schamz. Are they smiling at me, he asks himself, or at the sight of me? It's worth raising the question because there is quite a difference between the two. If they are smiling at me it is because, in a certain way, they know me, and because they at least recognize in me something that pleases them or makes them happy; if they are smiling at the sight of me, it is simply because I amuse them. But how can they know me when I have never seen them before? They cannot, quite obviously. Therefore, the reason is that I amuse them. But exactly how, honestly, I could not say. From time to time I catch sight of myself and even take a look at myself, and never once has this brought the slightest smile to my lips. So couldn't it be said that I am the one who doesn't know myself, based on the fact that I am unable to see in myself what can make people smile—or, after all, make them happy—and that they, on the other hand, know me since they are able to see in me what can make people smile or happy? Their great number, as well as their inability to reach a consensus on this matter beforehand, pleads in their favor; but on the other hand, I see nothing that might support my cause. I am therefore forced to admit that there exists within me something quite visible and objective, something likeable or amusing, which my subjectivity renders invisible to my eyes. Here's yet another piece of evidence to add to the list of this irksome character's liabilities, as if there weren't enough already! Ah! Mordechai Schamz takes to dreaming, if it were only possible to unload oneself entirely on other people, how light life would be! You would only need to go up to the first person passing by and ask him, Am I cheerful, am I sad, is it beautiful, is it good or is it bad? And once the answer is given, you would be on your way, even lighter still, if possible. Considering only the case before me now, am I not, in the eyes of many, the most jolly sort of rake, a genuine public clown? Yes, but it is quite possible that those who do not smile at the sight of me, who are even more numerous, find me a rather glum specimen. So ought I not to be on the alert to change my mood according to whom I meet, not to mention that I would be unable to shirk the demands of individual consciousnesses in quest of their own reality as I am of my own? All things considered, concludes Mordechai Schamz, it is far simpler for me, after all, to subscribe to the feeling of the first person chance sends my way, and which is as valid as any other. (pp. 91-92)

0 notes

Text

The Siege in the Room by Miquel Bauça, translated by Martha Tennent

These smiling, timeless girls have never played pétanque. They leave that to their crude uncles who get drunk for no reason, or dress up as Knights Templar to terrify people in houses far from the center of town. Girls from Perpignan always have clean fingernails, and nowhere else in the world can you encounter girls with such consistent, uniform enamel. Of course, not everything is charming. A secret part of their body soon dries up. A fact not often divulged. (Carrer Marsala, p. 40)

Effortlessly, I jump over the enclosure, careful to avoid making obscure gestures that would mark me as an outsider. I leave the master keys behind. We have entered—all of us together—the civilization of risk. Good deeds are not the right approach. It's the effect that counts. We have to maintain the balance between effects and chairs. If this balance were broken, what would we glimpse, other than harrowing dawns, charred logs, dead leaves, end-of-party confetti? ... Yes, we would march, but no one would know who we were without a clear insignia. We would be despondent, unable to see the mountain. It would undoubtedly be there, but the fog, smoke, and misery would contradict the evidence.

The warden is intimidated. She no longer dares to tense the cord and trip me. Instead, she spreads the word that I am one of the most curious prisoners she has had ... She doesn't hold me captive. I'm the one with my hand on the rope. She'll leave as soon as it's dark, shamelessly announcing that she's going to take a look around the countryside. Does she think I could possibly imagine her among the shrubs? Lying is such a poor artifice! She won't deny that she's gone beyond the walls. Probably stopped at an inn where grease and soot cover the napkins and blankets, the backs of chairs. I won't tolerate any more deceit. I will be the first to deceive. I'll put on clean socks without her knowing. The soles of my feet will notice. Could she possibly say anything comparable to that? I am blind to nothing... I know she has a friend, a woman who's a saint. But where is the saint known? On the outskirts of town, in houses filled with vicious brothers-in-law who never go out. Always seated, legs spread to show off their woolen socks. This saint was canonized, held in higher esteem than she deserves... Not even the bay leaf in the stew adds any taste. Both women have to suffer through it, till the warden finally gives in and dozes off. Sundays with the saint are like this. The warden thinks I don't know.

I've endured... endured the dust and the grease. I'm rough, austere; I'm aware of it. I understand the enthymemes and litotes, in space. I'm restoring order... I know that to build a grape arbor you have to keep the branches neat and not over-harvest ... just a little each time. (The Warden, pp. 119-20)

0 notes

Text

The Caretaker by Doon Arbus

It was the last of its kind, saved from extinction, not by any intrinsic Darwinian attribute, but by the whims of chance. It had survived the sudden recent influx of bulldozers and cranes and construction crews that had done away with its original neighbors, leaving in their wake a motley assortment of competing ambitions: faceted tiers of glass in the shape of a defunct wedding cake reflecting fragments of cloud back at the sky, windowless concrete bunkers for exhibiting art, a rose-colored ziggurat, and a pair of leaning towers, as yet unoccupied. This bombastically revitalized environment imposed upon the lone survivor—an unprepossessing three-story red brick building—a look of baffled stoicism. In the absence of any noteworthy architectural feature to justify its continued existence in the face of all this change, it squatted there stubbornly on its bit of turf, a dwarfed, defiant anachronism.

At certain times of day, in certain bright or fading light—a wintry afternoon glare, or at dusk before the intrusion of the streetlights— the raised lettering on the brass plaque beside the front door was easily misread as ORGAN FOUNDATION, which is what the locals took to calling it. "Meet you across from the Organ," they'd say with the breezy nonchalance of the initiate. This nickname—conjuring up a medical lab harvesting body parts or an obsolete musical instrument factory—derived from the fact that the plaque's initial capital M had lost its sharp edges (possibly due to an error at the foundry or excessive polishing) and had begun to recede into the background, managing at times to achieve invisibility. The plaque's subtitle however identified the building as the home of THE SOCIETY FOR THE PRESERVATION OF THE LEGACY OF DR. CHARLES ALEXANDER MORGAN—a Morgan unrelated to, and not to be confused with, the renowned financier of the same name with his eponymous well-endowed uptown Library, although such confusion frequently occurred, invariably to the benefit of the former residence of Dr. Charles, about one third of whose visitors came because they had mistaken it for that other, more notable venue. This is not to say that Dr. Charles Morgan did not have his own legitimate coterie of devotees determined to compensate for his relative lack of fame by the intensity of their allegiance. Many of them, along with members of the Society and invited guests, meet at the Foundation twice a year to celebrate the anniversaries of their hero's birth (August 29) and death (January 11) with refreshments, readings, and spirited discussions.

Twice a day, six days a week, the caretaker conducts tours of the premises and its collections. If you happened to be curious enough to pay a visit on a Saturday morning, for instance—a Saturday similar to so many that have come and gone since the fall of 1989 when, with little fanfare, the Morgan Foundation declared itself open to the public—you might find other would-be visitors meandering down the block. They come singly; they come by twos or threes. Those venturing up the stoop will usually discover the front door slightly ajar, but since this seems less an invitation than an oversight, they hesitate for fear of trespassing. Peering inside does little to reassure them. They find no one there to greet them, just other uneasy, waiting visitors gathered in a makeshift vestibule, a room awkwardly truncated by the addition of a pair of mahogany sliding doors, currently closed.

The size of the group that assembles here—which, even in the Foundation's heyday just after Morgan's death, numbered less than twenty—has been steadily shrinking. There are still, from time to time, the small enclaves of foreign sightseers who speak scarcely any English but are nonetheless resigned to being led around and lectured to. There are the women, likely members of a cultural club on one of their regular excursions, helping themselves to the free leaflets on display. There is the occasional couple, young or not so young, hoping for an unorthodox romantic adventure, lured by the dim lighting and an anticipated atmosphere of reverence. There is the single parent with a reluctant teenager in tow; someone killing time between appointments in the neighborhood; the student doing research. Each new arrival is subjected by his predecessors to a surreptitious appraisal, a look verging on the xenophobic that seems to say: If you have chosen to come here, I must be in the wrong place.

By the time the caretaker makes his entrance—always punctual, never early—to rescue the room's occupants from themselves and one another, the waiting period has lulled them beyond impatience into resignation, a state just short of somnambulism, out of which the sliding doors' low reluctant groan startles them; they turn as one toward the sound. The figure in the doorway, an angular, somewhat off-kilter silhouette, greets them, cheerlessly, by rote. "Good morning all," he says, addressing no one in particular as he slides the doors shut behind him and proceeds to a table at the east wall.

He is a monochromatic man. Dust is his color. It envelops every aspect of his person, hair, skin, eyes, clothing, softening all distinctions. The furrows in his otherwise unspoiled face suggest an outdoor life, weathered by sun and wind, but his current pallor makes recent exposure to the elements unlikely. "Welcome to the home of Dr. Charles Alexander Morgan," he continues as he stations himself behind the table, absentmindedly realigning the cashbox, the stack of leaflets, and the portable credit card processor; fingering a roll of red tickets (the generic kind, available in any stationery store), and the leather-bound horizontal ledger serving as a guestbook. "I'm the caretaker. I'm here to be your guide." He pauses and with a sigh, as if this next disclosure were more a confession than a point of information, introduces himself by name.

Once the preliminaries have been dispensed with (admission fees in exchange for tickets—cash preferred, exact change if possible—and the ritual signing of the guestbook, address required, to facilitate future solicitation of funds), the caretaker will slide the door open once again and lead the way into the room beyond, pausing on the other side to supervise entry. One by one, as demanded by his staging, members of the group pass single file through the opening. They sidle past him obediently, heads lowered, as he stands to one side, rhythmically clicking the counter in his left hand, totting up the numbers (6,7,8...) to check and recheck as they move through the house, lest someone linger behind, disobeying the rules, secreting themselves in a dark corner, touching or rearranging the treasures of the place, or, worse still, pocketing something small. As they commence the tour, visitors find themselves in a wide windowless hallway, its walls adorned from floor to ceiling with an eclectic mass of artifacts, punctuated by the occasional glass cabinet, spotlit from above to theatrical effect, which nonetheless does little to improve the visibility of its contents. A long waist-level double-sided vitrine bisects the room, making navigation difficult.

At first glance the display looks not so much haphazard as deliberately organized to confound comprehension. Ordinary domestic items (a wire hanger, a chewing-gum wrapper, locks with and without their keys, a broken hinge, a watch without a watchband, a toilet plunger, a plastic coffee lid) vie for position with a smattering of gilt-framed eighteenth-century oil portraits, a large multifaceted jewel, an African mask of teak and straw, a pair of pearl-handled dueling pistols aimed at one another. Nature has its place here, too: seashells, dried leaves, driftwood, lumps of coal, a human skull. Objects are fastened to the walls or occupy small specially designed shelves. It is almost possible to decipher the small numbers stenciled near each item, suggesting some sort of identification system. With no instruction, the newcomers begin to reassemble themselves shoulder to shoulder as if by instinct just inside the room, forming a squashed horseshoe. All along the dark plank floor, at a distance from the walls of about a foot, a strip of black tape symbolizes a barrier, the only obstacle between the curious and the many tantalizingly unprotected things confronting them. Some crane their necks to see. Others bend forward precariously, hands on knees. There is usually at least one unwitting transgressor, who obliges the caretaker to remonstrate.

"Keep your distance, please," he warns in an undertone all the more imposing for its lack of volume. "Mind the barrier. Touching is forbidden." (pp. 3-7)

***

"You will soon forget me," he says instead. "And I you. Just as those you love, on whose devotion you so fervently depend and who profess themselves incapable of going on without you will soon begin forgetting, too. Or, worse still, will misremember, only to lose you in a miasma of reverence or remorse. What else can you expect of memory, that flabby capricious muscle, so prone to distractions, self-justification, embellishment, delusion."

A fidgety little man at the rear of the group can restrain himself no longer. "I think I've had enough of this. I'm out of here," he announces in a startlingly high-pitched voice, cinching up the belt of his safari jacket as a demonstration of resolve and taking a few bold steps towards the door. The words are intended to stimulate action, not just his own, but that of his fellows; a few people go so far as to glance in his direction, but no one makes a move to follow. Paralysis prevails. It's as if the time they have spent in this place surrounded by Dr. Morgan's things in the company of Dr. Morgan's man has gradually instilled in them a state of passivity they are now incapable of throwing off, as if there were something in the vaguely fetid air hostile to free will, depriving them of any desire for independent action.

In the absence of confederates, the would-be defector's courage fails him, leaving him painfully conscious of his sudden self-imposed isolation from the pack, equally incapable of rejoining the others or of following through on his threatened departure. He lingers disconsolately on the island of carpet beneath his feet, stranded midway between his former comrades and his anticipated freedom, an outcast on the fringe of a lost opportunity.

The caretaker takes up the challenge anyway. "Go on, go then if you must," he says, addressing the entire group with a dismissive wave of the hand, as if he were in the act of making them disappear. "Or stay if you prefer. It hardly matters in the end. Even as you stand there, smugly swaddled in your swaddlings, propping up your fictional personas with freshly blackened hair or reddened lips or whatever transparent masquerade helps you pass for who you think you were or hoped to be, oblivion waits, smiling. Whatever made you think you could escape? Sooner or later we all wind up a pile of empty clothes and worthless keepsakes and sad, abandoned furniture, one last revenge on former friends and relatives now burdened with mounds of stuff to defile, destroy, or auction off. That's the ultimate legacy: whatever's left behind of you in everything you happen to have touched along the way, everything on which you've inadvertently leached away bits of yourself in passing—those flecks of dead skin, the stray hairs, the oily fingerprints, the sweat, the drool, the dried up blood and other fluids. That's what you'll inevitably become and what you will, with any luck, remain, thanks to the impressionable objects you've come into contact with—stone and wood and cloth and metal—things with no agenda, no cause to plead, no interest in you other than to do what they can't help but do: to simply hold you and to keep you and preserve you in all the ferocious tenderness of their sublime indifference."

He speaks with the impassioned equanimity of someone who has nothing left to lose, or more precisely, someone for whom any loss would be counted a kind of victory. He can harbor no illusions about the impending repercussions. Exposure is inevitable. He has finally gone too far. Complaints against him will be lodged with the authorities. His words will be misquoted, his transgressions reported on and perniciously embellished. Once more, he will be summoned before the Board like a delinquent schoolboy and called upon to defend his actions. Reprimands will have to be endured, some suitable form of punishment meted out. Even banishment, the ultimate threat, may be in the offing. All this no doubt he can foresee, but he no longer has the power to silence himself. Besides, it's probably too late for silence now. He presses on.

"Don't you even begin to get it yet? This is what lies at the root of the Doctor's reverence for the object: the unique unadulterated particles of history embedded in each one of them from the humblest paper clip or paper coffee cup to the rarest irreplaceable treasure. History's last hope rests here, in these mute, unborn, undead enemies of time. Without them and the place to keep and care for them as they deserve, we'd all wind up orphans of some interminable present with no past solid enough to cling to, no illusion of a future up ahead." His left eye has begun to twitch and while he speaks he rubs at it impatiently like a cranky child awakened from a sweaty summer nap.

"Where else do you think history resides? Do you really think it's about something as ephemeral as words? Do you actually believe the stories they've filled our heads with, those lies and mangled truths concocted in a futile effort to impose a reassuring pattern on the random by assembling disparate events into some arbitrary chronological chain of cause and consequence. Wake up, for god's sake! Look around you. Are you blind? Don't you see what the man has done here? Don't you feel the power radiating from the things inside this place—yes, partly on account of the simple fact that, despite their encroaching obsolescence, they threaten to endure and outlast all of us, these seething carcasses of what once was and is no longer—but also because of the terrible pull they exert on one another. Don't you feel it? Don't you feel how desperately the hammer craves the nail, how ardently the etching congeals itself around the contours of its frame, a magnetism so intense you could easily wind up an unintended casualty of the undertow."

He manifests the peculiar fluency of someone who has honed his conversational skills without the benefit of anyone to talk to, substituting for the more ordinary forms of verbal intercourse extensive monologues conducted solely with himself, unimpeded by interruptions or contradictory opinions or even so much as the implicit rebuttal on the face of a skeptical listener; someone in the habit of embracing with equal fervor any side of a complex, vexing question as a kind of exercise to keep the mind alert and test its intellectual flexibility, pitting one adopted viewpoint against another in a contest which—given the perfect parity of the participants—can only achieve victory by arriving at a stalemate.

"Look," he continues, "no one disputes the fact that every single object on display is first of all defiantly a thing unto itself, a gloriously purposeless, self-sufficient thing with all its own idiosyncratic physical attributes. But on the other hand, consider this: in the absence of a lock—or the concept of a lock—what is a solitary key but a sort of cripple, a strange lost incomprehensible entity yearning for a reason to exist? What can they possibly make of such a baffling artifact a thousand years from now when keys and locks have long since grown extinct? Relationships change everything. Below us in the rooms downstairs—could you have really failed to notice?—even though nothing moves and nothing speaks, a veritable riot is going on. The place is teeming with petty quarrels and competitions, with forbidden assignations, conspiracies, alliances, unlikely kinships, and attractions and repulsions. Didn't you catch the uncut diamond in its case winking impudently at the shiny lump of coal across the way? Or the virgin candle, conceived to be devoured slowly by a flame, inclining helplessly in the direction of the nearby unlit match, its doom and destiny? Weren't you even the slightest bit intrigued by the hourglass, the sundial, the cuckoo clock, and the rest of their kind clustered together in a corner of the second floor carrying on their interminable debate over the nature of time and how to measure it? The strategic distance between any one thing and the next—or the way they're poised in apposition or collusion—transforms them all. Isn't this how society itself purports to function? For better or worse, each member is made smaller, larger, darker, lighter, rounder, flatter, richer, poorer, stronger, weaker, plainer, queerer in contrast to whatever winds up in its vicinity. As, for that matter ..." He hesitates a moment on the brink of an unexpected twist in his disquisition before delivering his conclusion, "As are you, my friends."

The caretaker scrutinizes the small amorphous blob of humanity in front of him, which keeps shifting, contracting, reformulating itself in the manner of a single living organism. Its eight component parts, as if dissatisfied with the degree of their proximity, have been steadily closing ranks, seeking warmth or comfort or a semblance of safety, while the solitary ninth member lingers in their wake, like a drop of spume cast off by the undulating sea. At this point, the entity can shrink no further without risking inadvertent physical contact with itself. Even now, breaths commingle. A shoulder is in danger of brushing up against a powdered cheek; a finger must contort itself to avoid an unprovoked encounter with a stranger's thigh.

From the standpoint of invidious comparisons, the nine people do not fare terribly well in the eyes of their host. One man's distinctive nose becomes an unfortunate parody of all other noses. The sumptuousness of a woman's dark complexion turns everyone else ghostly. Each individual set of characteristics serves as a tacit rebuke to the very nature of someone else's, making oddities of them all. The entire spectacle strikes the caretaker as simultaneously comic and pathetic, sending him into a fit of soundless laughter, which leaves him momentarily helpless, nearly doubled over at the waist, his torso trembling in an effort to suppress the outburst. "Sorry," he gasps, when at last he manages to regain his composure. "But really, you know, you'd best beware your neighbors." (pp. 78-83)

0 notes

Text

Our Philosopher by Gert Hofmann, translated by Eric Mace-Tessler

Our philosopher has died suddenly. Our hearse collected him. The hearse drivers—no one knows who had them come—drove up to his place Monday morning on rubber wheels, silently, and they sprang from their box. We saw it ourselves.

We're leaning against Höhler's garden fence and aren't making ourselves dirty. The hearse drivers pull the coffin meant for Herr Veilchenfeld out of their large-wheeled, solemn and rickety hearse with a remarkable scraping noise that carries the length of Heidenstrasse, and disappear, after having tapped in passing on the feather-tufted neck of their little horse. Surely they don't want to go and get Herr Veilchenfeld? Yes, they are getting Herr Veilchenfeld! Only yesterday, around eight in the evening in middling weather, I saw him in his back garden, pale but standing amidst the lilac bushes. He was behind, not in front of, his garden wall, but we could see through the cracks. For, although it was known in our town that after his release Herr Veilchenfeld had moved out to us, and now lived in Heidenstrasse without connections (Mother), in the house with the bay window, he was more and more seldom to be seen in the last days.

Does he really still live here? we ask Father.

Yes, says Father, he is upstairs.

And what does he do?

He sits at his table.

And why doesn't he come down?

Because I feel more secure amongst my books than amongst my fellow countrymen, Herr Veilchenfeld always said to Mother across the narrow bit of garden, which he retraced with short steps time and again, and, under the brim of his black hat, he smiled at her out on the street. (pp. 3-4)

***

It isn't true that history can teach nothing; it is merely that there are no students. (p. 15)

***

If you consider that Herr Veilchenfeld is already over sixty and isn't the healthiest person either, says Father, who examined him one Monday morning in Heidenstrasse and diagnosed a bad heart and then prescribed little white pills, although they probably won't help him. If you consider...

Yes? I ask.

Instead of the sixty kilos Herr Veilchenfeld should weigh, he doesn't even weigh fifty and he keeps losing more and he will, despite the greatness of his mind, soon disappear and be rapidly forgotten.

And, I ask, if you consider this?

Exactly, Father says. (p. 29)

0 notes

Text

Vertigo by Boileau-Narcejac, translated by Geoffrey Sainsbury

At two he was waiting at the Etoile. She was always punctual.

'Ah!' he exclaimed. You're in black today.'

'I love black. If I had my own way I'd wear nothing else.'

'Why? It's a bit mournful, isn't it?'

'Not at all. On the contrary, it gives value to everything; it makes all one's thoughts more important and obliges one to take oneself seriously.'

'And if you were in blue, or green?'

'I don't know. I might think myself a river or a poplar... When I was little, I thought colours had mystical properties. Perhaps that's what made me want to paint.'

She took his arm, with an abandon that almost submerged him in a wave of tenderness.

'I've tried my hand at painting too,' he said. 'The trouble is, my drawing's always so weak.'

What does that matter? It's the colour that counts.'

'I'd love to see your paintings.'

'They're not worth much. You couldn't make head or tail of them: they're dreams really... Do you dream in colour?'

'No. Everything's grey. Like a photograph.'

'Then you couldn't understand. You're one of the blind!'

She laughed and squeezed his arm to show him she was only teasing.

'Dreams are so much more beautiful than the stuff they call reality,' she went on. 'Imagine a profusion of interweaving colours which penetrate right into you, filling you so completely that you become like one of those insects which make themselves indistinguishable from the leaf they’re resting on. . . Every night I dream of… of the other country.’

‘You too!’ (pp. 63-64)

0 notes

Text

Sum of Every Lost Ship by Allison Titus

The Nineteenth Century

Across the meadow the doeskin sack waits empty

no cord of wood stacked clean.

The news is old and the news gets older.

I while away the dormant season

with the broken Casio and rolling

papers I found in your jacket

or was it your desk. Thief or witness:

I do not boast.

Tragedies rummage the most appropriate dress

from the attic

those that lengthen darkly

and trail behind the heels.

Elbows in: there are observances to make,

gifts each mouth must summarize.

Wrist to wrist and steady

your small hand open;

Here. Like this she said,

and the news got older. The last light

trundled from the carriage

waits empty,

wilting flax and temper, bearing

down. All the evers resign to the dark

rooms, spinning wool to yarn

one foot on the pedal.

These bargains

wagered with the night.

The sheep's head bartered to the captain

under the silence, the skirt of dusk unpleating

the porch as bats hover and feast.

If anything is left to abandon, then we are eloquent

in our parting; restlessness a suitcase

full of long white gloves.

No thumbprints on the door

sash. No disturbance in the leaves.

0 notes

Text

The Dead and the Living by Sharon Olds

Things That Are Worse Than Death

(for Margaret Randall)

You are speaking of Chile,

of the woman who was arrested

with her husband and their five-year-old son.

You tell how the guards tortured the woman, the man, the child,

in front of each other,

"as they like to do."

Things that are worse than death.

I can see myself taking my son's ash-blond hair in my fingers,

tilting back his head before he knows what is happening,

slitting his throat, slitting my own throat

to save us that. Things that are worse than death:

this new idea enters my life.

The guard enters my life, the sewage of his body,

"as they like to do." The eyes of the five-year-old boy, Dago,

watching them with his mother. The eyes of his mother

watching them with Dago. And in my living room as a child,

the word, Dago. And nothing I experienced was worse than death,

life was beautiful as our blood on the stone floor

to save us that—my son's eyes on me,

my eyes on my son—the ram-boar on our bodies

making us look at our old enemy and bow in welcome,

gracious and eternal death

who permits departure.

***

Miscarriage

When I was a month pregnant, the great

clots of blood appeared in the pale

green swaying water of the toilet.

Dark red like black in the salty

translucent brine, like forms of life

appearing, jelly-fish with the clear-cut

shapes of fungi.

That was the only appearance made by that

child, the dark, scalloped shapes

falling slowly. A month later

our son was conceived, and I never went back

to mourn the one who came as far as the

sill with its information: that we could

botch something, you and I. All wrapped in

purple it floated away, like a messenger

put to death for bearing bad news.

***

The Forms

I always had the feeling my mother would

die for us, jump into a fire

to pull us out, her hair burning like

a halo, jump into water, her white

body going down and turning slowly,

the astronaut whose hose is cut

falling

into

blackness. She would have

covered us with her body, thrust her

breasts between our chests and the knife,

slipped us into her coat pocket

outside the showers. In disaster, an animal

mother, she would have died for us,

but in life as it was

she had to put herself

first.

She had to do whatever he

told her to do to the children, she had to

protect herself. In war, she would have

died for us, I tell you she would,

and I know: I am a student of war,

of gas ovens, smothering, knives,

drowning, burning, all the forms

in which I have experienced her love.

***

The Takers

Hitler entered Paris the way my

sister entered my room at night,

sat astride me, squeezed me with her knees,

held her thumbnails to the skin of my wrists and

peed on me, knowing Mother would

ever believe my story. It was very

silent, her dim face above me

gleaming in the shadows, the dark gold

smell of her urine spreading through the room, its

heat boiling on my legs, my small

pelvis wet. When the hissing stopped, when the

hole had been scorched in my body, I lay

crisp and charred with shame and felt her

skin glitter in the air, her dark

gold pleasure unfold as he stood over

Napoleon's tomb and murmured This is the

finest moment of my life.

***

The Elder Sister

When I look at my elder sister now

I think how she had to go first, down through the

birth canal, to force her way

head-first through the tiny channel,

the pressure of Mother's muscles on her brain,

the tight walls scraping her skin.

Her face is still narrow from it, the long

hollow cheeks of a Crusader on a tomb,

and her inky eyes have the look of someone who has

been in prison a long time and

knows they can send her back. I look at her

body and think how her breasts were the first to

rise, slowly, like swans on a pond.

By the time mine came along, they were just

two more birds in the flock, and when the hair

rose on the white mound of her flesh, like

threads of water out of the ground, it was the

first time, but when mine came

they knew about it. I used to think

only in terms of her harshness, sitting and

pissing on me in bed, but now I

see I had her before me always

like a shield. I look at her wrinkles, her clenched

jaws, her frown-lines—I see they are

the dents on my shield, the blows that did not reach me.

She protected me, not as a mother

protects a child, with love, but as a

hostage protects the one who makes her

escape as I made my escape, with my sister's

body held in front of me.

0 notes

Text

The Pause Between Inhale and Exhale by Roselyn Elliott

Myth

It's my first week in the heart unit and

my patient resembles my mother, plump,

a curly haired pleaser. Only the irregular beat

when I press the stethoscope hard

under her left breast, tells me she is sick.

On white sheets taut across her bed,

she sleeps serenely on her side.

Next morning in the morgue, I stand

at the back in a huddle of classmates.

The pathologist makes a few smart cuts, lifts her heart

high in both hands toward the overhead light.

We gape. Like a dumb flock we stare

upward, at the kind heart, glistening

and pliant in his hands.

The smell of viscera invades my future,

vision blurs, fingers tingle.

What keeps me from falling is friends,

their warm bodies, pressing

toward the center of our crowd,

warm breath, brushing my ears.

Not one of us faints during the lecture

beneath her severed heart,

but in the brilliant light I see the lie

about our work: how each day

is its own interlude of denial,

how the story will tell itself over and over

until the end of time.

***

Summer Lights

Fireflies seeding the backyard

your first evening away for work.

The trees and underbrush are alive

with this party. Choreographed

to attract a mate, or prey, each one

emits its green flare the second

another switches off.

And this sultry June evening,

the private universe of my right eye

showers my vision with commas,

half-moons, parallel gnats dancing

to retinal lightning. At the window

I turn my head quickly, catch

the next shape, the next. Eye flashing

with each small shift, floaters collide

with fireflies. Sitting on this smooth bed

I remember you'll be gone a week,

reading papers, your eyes straining

with students' cursive. I picture you

bent over the table of notebooks,

think of your patience in all things

all these years, even when I don't see

what you mean, or when I don't look

at you long enough. Fireflies

between trees, pierce the humid dusk

with yellow beads, green stars

lingering into the night.

***

On the Way to the Clinic, We Pass a Small Country

Two or three feet across,

beside a public school

where chain-link fences meet:

plastic cups, burger wrappers

old watch with a broken band,

chicory in blue bloom.

Ants burrow up, claim

dead insects. A sparrow balances

on a single stalk of timothy.

In this city of fumes and noise,

between brick walls, moss

grows on one side of stones.

On the way to treatment

for these wild-growing tumors

in my right breast,

I claim for myself

this tiny triangular wasteland,

this small autonomous nation.

***

Night Rumors

Tonight, my son molds himself

into the couch and bites the remainder

of his fingernails, kept worn and sore.

He rises abruptly

to go out with his friends.

When he stands, he is a tall man,

grown to that altitude

where life is deadly,

bright and irregular.

I've seen them on the street in little crowds.

He has told me they sit around

at someone's house, seeking substance

of the mind, or for the mind,

hunting a certain mellow knowledge.

This is what a parent learns:

In the dark our children find themselves.

All night, shining and laughing

above some shapeless maw,

they coax the thing until they hear it moan,

then tempt it with their life light,

tempt it further,

then come home.

***

The Separation of Kin

Bovine distress bristles the countryside.

The calling is unbearable:

their constant blatting across our yard.

What could our neighbor be thinking,

selling the babies to the other neighbor

where they cry for their mothers

in the field beside our house?

Young throats open, offspring

question parents, and the cows' reply

with a low keening, answered ten seconds later.

All night

their pleadings echo over pastures,

reverberate through our rooms,

spread through the dark woods, tree trunk to tree leaf,

rise above the canopy into morning.

Tomorrow

hoarse from exhaustion and despair,

a deep acquiescence unknown to humans

will have overtaken these sentient beasts,

but this day our only choice

is to endure this loss surrounding us,

rivet our gaze in the amber light,

and imagine silence.

0 notes

Text

The True Deceiver by Tove Jansson, translated by Thomas Teal

For years, people had come to Katri and asked her to help them with sums they couldn't do themselves. She handled difficult calculations and percentages with complete ease, and the answers fell into place and were always correct. It began while Katri was doing the storekeeper's ordering and paying his bills. It was then she acquired a reputation for being shrewd, penetrating and good with figures — she discovered that several merchants in town were cheating. Later, she found the storekeeper in the village doing the same thing, but no one knew about that. Katri Kling also had an unerring sense for how sums should be justly allocated and for unambiguous solutions to knotty problems requiring a different kind of arithmetic. The villagers began coming to her with their tax declarations or to talk about bills of sale, wills and property lines. There was a lawyer in town, of course, but they had more faith in her, and why throw money away on a lawyer?

"Give them the meadow," Katri said. "You can't do anything with it anyway; it isn't even good pasture. But put in a clause that says it can't be developed, or sooner or later you'll have them living next door. And you don't like them."

Then she told the opposing party that the meadow was worthless, but they could use it for peace of mind by putting up a fence and a 'No Trespassing' sign so they wouldn't constantly have to hear the neighbours' kids. Katri's advice was widely discussed in the village and struck people as correct and very astute. What made it so effective, perhaps, was that she worked on the assumption that every household was naturally hostile towards its neighbours. But people's sessions with Katri were often followed by an odd sense of shame, which was hard to understand, since she was always fair. Take the case of two families who had been looking sideways at each other for years. Katri helped both save face, but she also articulated their hostility and so fixed it in place for all time. She also helped people to see that they'd been cheated. Everyone was highly amused by Katri's decision in the case of Emil from Husholm. He'd contracted severe septicaemia that had cost him a lot of money and kept him from working for quite some time, and Katri said it was a job-related accident and called for workman's compensation. His employer would have to apply to the employment office on his behalf.

"Well, not really," Emil objected. "It didn't happen while I was building a boat. I was just cleaning some cod."

And Katri said, "When will you learn? Work is work. A cod or a crowbar — it's all the same. Your father was a fisherman, wasn't he? And he worked for the fishery, didn't he? How many times did he injure himself at work?"

"Now and then."

"Of course. And he got no compensation. The government cheated him more times than he knew, so this makes it even."

People could cite many examples of Katri Kling's perspicacity. She seemed to make all the pieces fit together. If people doubted her, they could always have their important papers checked by the lawyer in town. But so far he had never questioned Katri's judgement. "What kind of wise old witch do you have out there? Where did she learn all this?"

In the beginning, people wanted to pay Katri for her services, but when that met a frosty reception, they stopped mentioning compensation. It seemed odd that a person who understood so much about other people's difficulties with out-of-the-ordinary situations should have been so unable to deal with the people themselves. Katri's silence made everyone uncomfortable. She responded to matter-of-fact questions, but she didn't talk. And, worst of all, she didn't smile when she met people, didn't encourage them, didn't help, didn't socialise at all.

"But why do you go to her?" said the elderly Madame Nygard. "Yes, she puts your business to rights, but you no longer trust anyone when you come back. You're different. Leave her alone and try to be nice to her brother."

People did sometimes ask about Mats, but not even that made her more agreeable. She just looked past them with her yellow slits of eyes and said, "Fine, thank you." And when they moved on, it was with a sense that they'd been prying, and they felt very small. So people brought her their problems and then slunk away as quickly as they could. (pp. 28-31)

***

"But where is everything? How did you find the space?"

"We didn't," Katri said. "We carried a lot of it out on the ice, and Liljeberg took the rest of it to the auction house in town. He'll bring you the money if they can sell it. Though it probably won't be much."

"Miss Kling," said Anna, "are you sure you haven't acted a bit high-handedly?"

"Could be," Katri said. "But think about it, Miss Aemelin. What if we had presented you with every piece of discarded furniture, every single one of those sad objects, all those meaningless things? You would have stood there and tried to decide what should be saved or thrown out or sold. Now everything's decided and settled. Isn't that good?"

Anna was silent. "Probably," she said, finally. "But all the same, it was very high-handed."

Far out on the ice lay a dark pile of rubbish waiting for the ice to break up, a monument to Mama and Papa's complete inability ever to get rid of possessions. How remarkable, Anna thought. The ice will go, and everything will sink, just go straight down and disappear. It's bold, it's almost shameless. I have to tell Sylvia. Later it occurred to her that maybe it wouldn't sink, not all of it. Maybe it would float to another shore and someone would find it and wonder where it came from and why. In any event, it was not even the least bit Anna's fault. (pp. 76-77)

***

It was during this period that Anna began to be aware, in a new and disquieting way, of what she did with her time and what she didn't do. She began observing her own behaviour more and more with every day that passed — the days that had passed unexamined for so long. When Anna lived alone, she had not noticed how often she let the daylight hours vanish in sleep. Letting sleep come closer, soft as mist, as snow; reading the same sentence again and again until it disappeared in the mist and no longer had any meaning; waking up, finding your place on the page, and reading on as if only a few seconds had been lost. Now suddenly it was clear to Anna that she had slept, and for quite a long time. No one knew, no one disturbed her, but still the simple and irresistible need to vanish into a nap became a forbidden thing. She would wake up with a start, open her eyes wide, grab her book, and listen. It was completely quiet. But someone had walked across the floor upstairs. (pp. 79-80)

***

Madame Nygard sat quietly waiting with her hands clasped on her stomach. Finally Anna took up the conversation to speak about something that had been bothering her for quite some time — the fact that she had begun speaking ill of people. "I never used to do that," she said. "Believe me, I never did. Someone came to Mama once and said, 'Your daughter is unusual; she never speaks ill of anyone. I remember it, I remember it quite clearly. But why? Did I trust everyone? Or was it only that I forgave them?"

"Well, well," said Madame Nygard. "That snow fell a long time ago, did it not?"

"But you trust people, don't you?"

"Yes, I suppose I do. Why shouldn't I? One sees and hears a great deal about the way people behave, but that's their problem. One doesn't want to make things worse by not believing that they mean what they say."

"It's beginning to get dark," Anna said. "I don't want to keep you too long."

"I'm in no hurry," said Madame Nygärd. "Those days are over. But I think I should be going in any case. Sometimes it's not wise to say too much all at once."

That night the dog stopped howling. (pp. 163-64)

1 note

·

View note

Text

To the Lighthouse by Virginia Woolf

'Nature has but little clay,' said Mr. Bankes once, hearing [Mrs. Ramsay's] voice on the telephone, and much moved by it though she was only telling him a fact about a train, 'like that of which she moulded you.' He saw her at the end of the line, Greek, blue-eyed, straight-nosed. How incongruous it seemed to be telephoning to a woman like that. The Graces assembling seemed to have joined hands in meadows of asphodel to compose that face. Yes, he would catch the 10.30 at Euston. (pp. 32-33)

***

They came to [Mrs. Ramsay], naturally, since she was a woman, all day long with this and that; one wanting this, another that; the children were growing up; she often felt she was nothing but a sponge sopped full of human emotions. (p. 36)

***

How then, [Lily] had asked herself, did one know one thing or another thing about people, sealed as they were? Only like a bee, drawn by some sweetness or sharpness in the air intangible to touch or taste, one haunted the dome-shaped hive, ranged the wastes of the air over the countries of the world alone, and then haunted the hives with their murmurs and their stirrings; the hives which were people. Mrs. Ramsay rose. Lily rose. Mrs. Ramsay went. For days there hung about her, as after a dream some subtle change is felt in the person one has dreamt of, more vividly than anything she said, the sound of murmuring and, as she sat in the wicker arm-chair in the drawing-room window she wore, to Lily's eyes, an august shape; the shape of a dome.

This ray passed level with Mr. Bankes's ray straight to Mrs. Ramsay sitting reading there with James at her knee. But now while she still looked, Mr. Bankes had done. He had put on his spectacles. He had stepped back. He had raised his hand. He had slightly narrowed his clear blue eyes, when Lily, rousing herself, saw what he was at, and winced like a dog who sees a hand raised to strike it. She would have snatched her picture off the easel, but she said to herself, One must. She braced herself to stand the awful trial of someone looking at her picture. One must, she said, one must. And if it must be seen, Mr. Bankes was less alarming than another. But that any other eyes should see the residue of her thirty-three years, the deposit of each day's living, mixed with something more secret than she had ever spoken or shown in the course of all those days was an agony. At the same time it was immensely exciting. (pp. 58-59)

***

For now [Mrs. Ramsey] need not think about anybody. She could be herself, by herself. And that was what now she often felt the need of — to think; well not even to think. To be silent; to be alone. All the being and the doing, expansive, glittering, vocal, evaporated; and one shrunk, with a sense of solemnity, to being one-self, a wedge-shaped core of darkness, something invisible to others. Although she continued to knit, and sat upright, it was thus that she felt herself; and this self having shed its attachments was free for the strangest adventures. When life sank down for a moment, the range of experience seemed limitless. And to everybody there was always this sense of unlimited resources, she supposed; one after another, she, Lily, Augustus Carmichael, must feel, our apparitions, the things you know us by, are simply childish. Beneath it is all dark, it is all spreading, it is unfathomably deep; but now and again we rise to the surface and that is what you see us by. Her horizon seemed to her limitless. (pp. 70-71)

***

Everything seemed possible. Everything seemed right. Just now (but this cannot last, [Mrs Ramsey] thought, dissociating herself from the moment while they were all talking about boots), just now she had reached security; she hovered like a hawk suspended; like a flag floated in an element of joy which filled every nerve of her body fully and sweetly, not noisily, solemnly rather, for it arose, she thought, looking at them all eating there, from husband and children and friends; all of which rising in this profound stillness (she was helping William Bankes to one very small piece more and peered into the depths of the earthenware pot) seemed now for no special reason to stay there like a smoke, like a fume rising upwards, holding them safe together. Nothing need be said; nothing could be said. There it was, all round them. It partook, she felt, carefully helping Mr. Bankes to a specially tender piece, of eternity; as she had already felt about something different once before that afternoon; there is a coherence in things, a stability; something, she meant, is immune from change, and shines out (she glanced at the window with its ripple of reflected lights) in the face of the flowing, the fleeting, the spectral, like a ruby; so that again to-night she had the feeling she had had once to-day already, of peace, of rest. Of such moments, she thought, the thing is made that remains for ever after. This would remain. (pp. 119-20)

***

And it struck [Lily], this was tragedy — not palls, dust, and the shroud; but children coerced, their spirits subdued. (p. 169)

***

What is the meaning of life? That was all — a simple question; one that tended to close in on one with years. The great revelation had never come. The great revelation perhaps never did come. Instead there were little daily miracles, illuminations, matches struck unexpectedly in the dark; here was one. This, that, and the other; herself and Charles Tansley and the breaking wave; Mrs. Ramsay bringing them together; Mrs. Ramsay saying 'Life stand still here'; Mrs. Ramsay making of the moment something permanent (as in another sphere Lily herself tried to make of the moment something permanent) — this was of the nature of a revelation. In the midst of chaos there was shape; this eternal passing and flowing (she looked at the clouds going and the leaves shaking) was struck into stability. Life stand still here, Mrs. Ramsay said. 'Mrs. Ramsay! Mrs. Ramsay!' she repeated. She owed this revelation to her. (pp. 183-84)

***

One must hold the scene — so — in a vice and let nothing come in and spoil it. One wanted, [Lily] thought, dipping her brush deliberately, to be on a level with ordinary experience, to feel simply that's a chair, that's a table, and yet at the same time, It's a miracle, it's an ecstasy. The problem might be solved after all. Ah, but what had happened? Some wave of white went over the window pane. The air must have stirred some flounce in the room. Her heart leapt at her and seized her and tortured her. (p. 230)

***

[Mr. Ramsey] was reading very quickly, as if he were eager get to the end. Indeed they were very close to the Lighthouse now. There it loomed up, stark and straight, glaring white and black, and one could see the waves breaking in white splinters like smashed glass upon the rocks. One could see lines and creases in the rocks. One could see the windows clearly; a dab of white on one of them, and a little tuft of green on the rock. A man had come out and looked at them through a glass and gone in again. So it was like that, James thought, the Lighthouse one had seen across the bay all these years; it was a stark tower on a bare rock. It satisfied him. It confirmed some obscure feeling of his about his own character. The old ladies, he thought, thinking of the garden at home, went dragging their chairs about on the lawn. Old Mrs. Beckwith, for example, was always saying how nice it was and how sweet it was and how they ought to be so proud and they ought to be so happy, but as a matter of fact James thought, looking at the Lighthouse stood there on its rock, it's like that. He looked at his father reading fiercely with his legs curled tight. They shared that knowledge. 'We are driving before a gale — we must sink,' he began saying to himself, half aloud exactly as his father said it. (pp. 231-32)

0 notes

Text

Brief Notes on the Art and Manner of Arranging One's Books by Georges Perec, translated by John Sturrock

But literature is not an activity separated from life. We live in a world of words, of language, of stories. Writing is not the privilege exclusively of the man who sets aside for his century a brief hour of conscientious immortality each evening and lovingly fashions, in the silence of his study, what others will later proclaim, solemnly, to be 'the honour and integrity of our letters'. Literature is indissolubly bound up with life, it is the necessary prolongation, the obvious culmination, the indispensable complement of experience. All experience opens on to literature and all literature on to experience and the path that leads from one to the other, whether it be literary creation or reading, establishes this relationship between the fragmentary and the whole, this passage from the anecdotal to the historical, this interplay between the general and the particular, between what is felt and what is understood, which forms the very tissue of our consciousness. (Robert Antelme or the Truth of Literature, pp. 2-3)

***

To begin with, it all seems simple: I wanted to write, and I've written. By dint of writing, I've become a writer, for myself alone first of all and for a long time, and today for others. In principle, I no longer have any need to justify myself (either in my own eyes or in the eyes of others). I'm a writer, that's an acknowledged fact, a datum, self-evident, a definition. I can write or not write, I can go several weeks or several months without writing, or write ‘well' or write ‘badly’, that alters nothing, it doesn't make my activity as a writer into a parallel of complementary activity. I do nothing else but write (except earn the time to write), I don't know how to do anything else, I haven't wanted to learn anything else... I write in order to live and I live in order to write, and I've come close to imagining that writing and living might merge completely: I would live in the company of dictionaries, deep in some provincial retreat, in the mornings I would go for a walk in the woods, in the afternoons I would blacken a few sheets of paper, in the evenings I would relax perhaps by listening to a bit of music…

It goes without saying that when you start having ideas like these (even if they are only a caricature), it becomes urgent to ask yourself some questions.

I know, roughly speaking, how I became a writer. I don't know precisely why. In order to exist, did I really need to line up words and sentences? In order to exist, was it enough for me to be the author of a few books?

In order to exist, I was waiting for others to designate me, to identify me, to recognize me. But why through writing? I long wanted to be a painter, for the same reasons I presume, but I became a writer. Why writing precisely?

Did I then have something so very particular to say? But what have I said? What is there to say? To say that one is? To say that one writes? To say that one is a writer? A need to communicate what? A need to communicate that one has a need to communicate? That one is in the act of communicating? Writing says that it is there, and nothing more, and here we are back again in that hall of mirrors where the words refer to one another, reflect one another to infinity without ever meeting anything other than their own shadow.

I don't know what, fifteen years ago when I was beginning to write, I expected from writing. But I fancy I'm beginning to understand, at the same time, the fascination that writing exercised — and continues to exercise — over me, and the fissure which that fascination both discloses and conceals.

Writing protects me. I advance beneath the rampart of my words, my sentences, my skilfully linked paragraphs, my astutely programmed chapters. I don't lack ingenuity.

Do I still need protecting? And suppose the shield were to become an iron collar?

One day I shall certainly have to start using words to uncover what is real, to uncover my reality.

Today, no doubt, I can say that that's what my project is like. But I know it will not be fully successful until such time as the Poet has been driven from the city once and for all, such time as we can take up a pickaxe or a spade, a sledge-hammer or a trowel, without laughing, without having the feeling, yet again, that what we are doing is derisory, or a sham, or done to create a stir. It's not so much that we shall have made progress (because it's certainly no longer at that level that things will be measured), it's that our world will at last have begun to be liberated. (The Gnocchi of Autumn or An Answer, pp. 26-29)

***

To question what seems so much a matter of course that we've forgotten its origins. To rediscover something of the astonishment that Jules Verne or his readers may have felt faced with an apparatus capable of reproducing and transporting sounds. For that astonishment existed, along with thousands of others, and it's they which have moulded us.

What we need to question is bricks, concrete, glass, our table manners, our utensils, our tools, the way we spend our time, our rhythms. To question that which seems to have ceased forever to astonish us. We live, true, we breathe, true; we walk, we open doors, we go down staircases, we sit at a table in order to eat, we lie down on a bed in order to sleep. How? Where? When? Why?

Describe your street. Describe another street. Compare.

Make an inventory of your pockets, of your bag. Ask yourself about the provenance, the use, what will become of each of the objects you take out.

Question your tea spoons.

What is there under your wallpaper?

How many movements does it take to dial a phone number? Why?

Why don't you find cigarettes in grocery stores? Why not?

It matters little to me that these questions should be fragmentary, barely indicative of a method, at most of a project. It matters a lot to me that they should seem trivial and futile: that's exactly what makes them just as essential, if not more so, as all the other questions by which we've tried in vain to lay hold on our truth. (Approaches to What?, pp. 32-33)

***

2.1. Ways of arranging books

ordered alphabetically

ordered by continent or country

ordered by colour

ordered by date of acquisition

ordered by date of publication

ordered by format

ordered by genre

ordered by major periods of literary history

ordered by language

ordered by priority for future reading

ordered by binding

ordered by series

None of these classifications is satisfactory by itself. In practice, every library is ordered starting from a combination of these modes of classification, whose relative weighting, resistance to change, obsolescence and persistence give every library a unique personality.