#yefet

Text

I wish Depa Billaba had a canonical birth year so that I figure out approximately when she was Mace’s padawan so I could figure out if it was feasible that he trained another padawan after her who would be the age that I want Yefet to be.

#The thing is that I need them to use Vaapad which is basically the more Jedi acceptable version of Maul's fighting style which Mace#literally invented and whom the only other practitioner was Depa. 😭😭😭#Not just that though cause I'm trying to conceptualize their history within the Order as being someone that kind of sort of slightly#makes the Council hear kill bill sirens in their minds and are clearly a little bit concerned about in their avoidant and useless way#for seeming a leetle bit too personally invested in injustices and a leetle too quick on the draw. Which I think is exactly the kind of#person they'd be like. Well if anyone can straighten this kid out it's Mace Windu. Lmfao#I think though it would be ideal if he wasn't their only Master and perhaps their first Master gets killed when they're already#pretty close to trials age which makes them considerably 'worse' and is probably when they become a concern in the first place#So then it's Mace who steps in to finish their training. Since his whole thing is funneling the 'dark' impulses into something 'light.'#Yeah. I really need to make a doc for them or something cause as of currently all the recorded information that exists for them is#in the paragraphs I've written on here 💀#yefet#sw

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

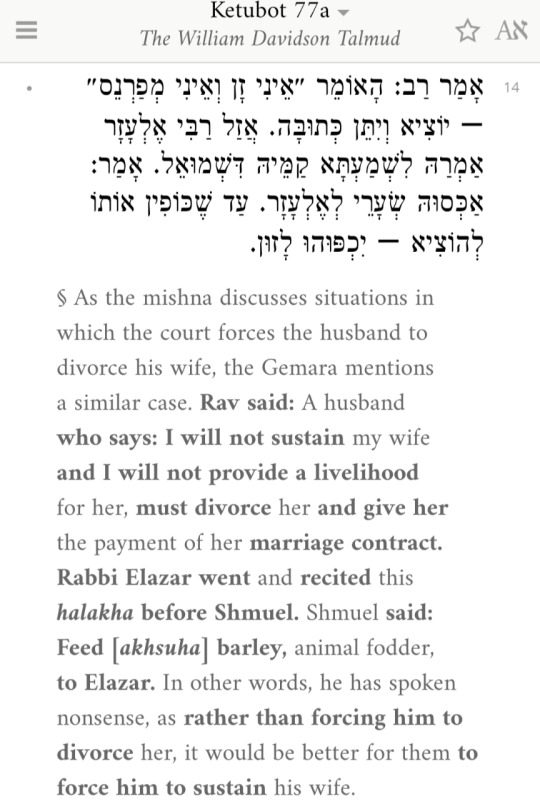

Wednesday 9/21, Ketubot 77: Barley Legal

I grabbed this passage because “Feed Elazar barley because he’s a herd animal” is a pretty “Great Murders tag” thing to say, BUT THEN

Imagine saying something your colleagues think is so stupid that it alters your diet.

Honestly it makes me glad I’m neither Sage, Rabbi, or Torah Scholar. I’ve said way dumber things than Rabbi Elazar without having my lunch replaced with hay.

#daf yomi#rav#rabbi elazar#shmuel#rabbi binyamin bar yefet#rabbi zeira#great murders of the talmud#tractate snacks

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

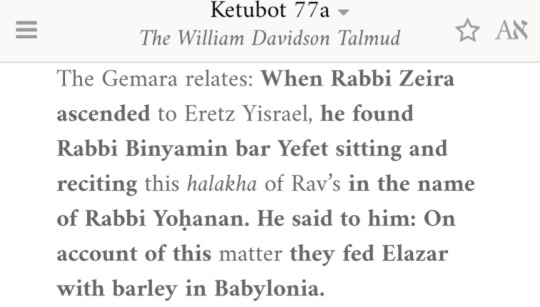

On this Yom Ha'Zikaron Le'Chalalei Ma'rachot Yisrael (Memorial Day for Israel's Fallen Soldiers and Terror Victims), I figured it's important to remember that Israeli victims did not exist solely on Oct 7. We have lost loved ones before and since. Here's a list with just one random victim to represent each year. Please scroll down the list to see how far back it goes.

(part 1/5, all parts in the reblogs)

2024: On Jan 7, we lost 19 years old Shai Garmai

2023: On Oct 7, we lost 28 years old Osama abu Madiam

2022: On Nov 23, we lost 18 years old Tiran Faro

2021: On May 12, we lost 5 years old Ido Avigal

2020: On Aug 26, we lost 39 years old Shai Ochayon

2019: On May 5, we lost 49 years old Zaid al-Chamamda

2018: On Dec 12, we lost Amiad Israel Yish Ran, who was murdered in his mother's womb

2017: On Nov 22, we lost 21 years old Hodaya Nechama Assoulin

2016: On Oct 25, we lost 14 years old Rami Namer abu Amar

2015: On Feb 17, we lost 4 years old Adelle Biton

2014: On Oct 22, we lost 2.5 months old Chaya Zissel Brown

2013: On Dec 24, we lost 22 years old Salech al-Din abu al-Atayef

2012: On Jul 18, we lost 28 years old Yitzchak Idan Kolangi

2011: On Apr 17, we lost 16 years old Daniel Aryeh Viplich

2010: On Feb 26, we lost 52 years old Netta Blatt Sorek

2009: On Apr 2, we lost 13 years old Shlomo Nativ

2008: On Mar 6, we lost 26 years old Doron Trunach Mahareta

2007: On Jun 17, we lost 85 years old Meir Cohen

2006: On Aug 10, we lost 4 years old Fatchi Assdi

2005: On Jul 12, we lost 16 years old Nofar Horvitz

2004: On Sep 29, we lost 2 years old Dorit Massarat Binsan

2003: On Sep 9, we lost 20 years old Naava Appelbom

2002: On Nov 10, we lost 4 years old Noam Levi Ochayon

2001: On Dec 12, we lost 42 years old Ester Avraham

2000: On Nov 21, we lost 19 years old Itamar Yefet

1999: On Jun 24, we lost 34 years old Tony Eliyahu Zanna

1998: On Dec 2, we lost 41 years old Osama Moussa abu Aisha

1997: On Mar 13, we lost 13 years old Natali Alkalai

1996: On Feb 25, we lost 57 years old Yitzchak Elbaz

1995: On Jul 24, we lost 60 years old Zehava Oren

As Tumblr limits a post to 30 images... part 1/5 - the next parts will be posted in the reblogs momentarily. Please check out the full list.

(for all of my updates and ask replies regarding Israel, click here)

#israel#antisemitism#israeli#israel news#israel under attack#israel under fire#terrorism#anti terrorism#hamas#antisemitic#antisemites#jews#jew#judaism#jumblr#frumblr#jewish#israelunderattack

217 notes

·

View notes

Note

loving your falafel research saga and just wanted to ask - something I remember hearing about falafel is that while Israeli culture definitely appropriated it, the concept of serving it in pita bread with salads, tahini etc. is a specifically Israeli twist on the dish. I wonder if you found/know anything about that?

The short answer is: it's not impossible, but I don't think there's any way to tell for sure. The long answer is:

The most prominent claim I've heard of this nature is specifically that Yemeni Jews (who had immigrated to Israel under 'right of return' laws and were Israeli citizens) invented the concept of serving falafel in "pita" bread in the 1930s—perhaps after they (in addition to Jews from Morocco or Syria) had brought falafel over and introduced it to Palestinians in the first place.

"Mizrahim brought falafel to Palestine"

This latter claim, which is purely nonsense (again... no such thing as Moroccan falafel!)—and which Joel Denker (linked above) repeats with no source or evidence—was able to arise because it was often Mizrahim who introduced Israelis to Palestinian food. Mizrahi falafel sellers in the early 20th century might run licensed falafel stands, or carry tins full of hot falafel on their backs and go from door to door selling them (see Shaul Stampfer on a Yemeni man doing this, "Bagel and Falafel: Two Iconic Jewish Foods and One Modern Jewish Identity," in Jews and their Foodways, p. 183; this Arabic source mentions a 1985 Arabic novel in which a falafel seller uses such a tin; Yael Raviv writes that "Running falafel stands had been popular with Yemenite immigrants to Palestine as early as the 1920s and ’30s," "Falafel: A National Icon," Gastronomica 3.3 (2003), p. 22).

On Mizrahi preparation of Palestinian food, Dafna Hirsch writes:

As Sami Zubaida notes, Middle Eastern foodways, while far from homogeneous, are nevertheless describable in a vocabulary and set of idioms that are “often comprehensible, if not familiar, to the socially diverse parties” [...]. Thus, for the Jews who arrived in Palestine from the Middle East, Palestinian Arab foods and foodways were “comprehensible, if not familiar,” even if some of the dishes were previously unknown to most of them. [...] They found nothing extraordinary or exotic in the consumption, preparation, and selling of foods from the Palestinian Arab kitchen. Therefore, it was often Mizrahi Jews who mediated local foods to Ashkenazi consumers, as street food vendors and restaurant owners. ("Urban Food Venues as Contact Zones between Arabs and Jews during the British Mandate Period," in Making Levantine Cuisine: Modern Foodways of the Eastern Mediterranean, p. 101).

Raviv concurs and furnishes a possible mechanism for this borrowing:

Other Mizrahi Jewish vendors sold falafel, which by the late 1930s had become quite prevalent and popular on the streets of Tel Aviv. [...] Tel Aviv had eight licensed Mizrahi falafel vendors by 1941 and others who sold falafel without a license. [FN: The Tel Aviv municipality granted vending license to people who could not make their living in any other way as a form of welfare.] Many of the vendors were of Yemenite origins, although falafel was unknown in Yemen. [FN: Many of the immigrants from Yemen arrived in Palestine via Egypt, so it is possible that they learned to prepare it there and then adjusted the recipe to the Palestinian version, which was made from chickpeas and not from fava beans (ṭaʿmiya). Shmuel Yefet, an Israeli falafel maker, tells about his father, Yosef Ben Aharon Yefet, who arrived in Palestine from Aden [Yemen] in the early 1920s and then traveled to Port Said in 1939. There he became acquainted with ṭaʿmiya, learned to prepare it, and then went back to Palestine and opened a falafel shop in Tel Aviv [youtube video].]*

But why claim that Yemeni Jews invented falafel (or at least that they had introduced it from Yemen), even though its adoption from Palestinian Arabs in the early days of the second Aliya, aka the 1920s (before Mizrahim had begun to immigrate in larger numbers; see Raviv, p. 20) was within living memory at this point (i.e. the 1950s)? Raviv notes that an increasing (I mean, actually she says new, which... lol) negative attitude towards Arabs in the wake of the Nakba (I mean... she says "War of Independence") created a new sense of urgency around de-Arabizing "Israeli" culture (p. 22). Its association with Mizrahi sellers allowed falafel to "be linked to Jewish immigrants who had come from the Middle East and Africa" and thus to "shed its Arab association in favor of an overarching Israeli identification" (p. 21).

Stampfer again:

On the one hand (with regard to immigrants from Eastern Europe), [falafel] underscored the break between immediate past East European Jewish foods and the new “Oriental” world of Eretz Israel.** At the same time, this food could be seen as a link with an (idealized) past. Among the Jewish public in Eretz Israel, Yemenite falafel was regarded as the most original and tastiest version. This is a bit odd, as falafel—whether in or out of a pita—was not a traditional Yemenite food, neither among Muslims nor among Jews. To understand the ascription of falafel to Yemenite Jews, it is necessary to consider their image. Yemenite Jews were widely regarded in the mid-20th century as the most faithful transmitters of a form of Jewish life that was closest to the biblical world—and if not the biblical world, at least the world of the Second Temple, which marked the last period of autonomous Jewish life in Eretz Israel. In this sense, eating “Yemenite” could be regarded as an act of bodily identification with the Zionist claim to the land of Israel. (p. 189)

So, when it's undeniable that a food is "Arab" or "Oriental" in origin, Zionists will often attribute it to Yemen, Syria, Morocco, Turkey, &c.—and especially to Jewish communities within these regions—because it cannot be permitted that Palestinians have a specific culture that differentiates them in any way from other "Arabs." A culinary culture based in the foodstuffs cultivated from this particular area of land would mean a tie and a claim to the land, which Zionist logic cannot allow Palestinians to possess. This is why you'll hear Zionists correct people who say "Palestinians" to say "Arab" instead, or suggest that Palestinians should just scooch over into other "Arab" countries because it would make no difference to them. Raviv's conclusion that the attribution of falafel to Yemeni immigrants is an effort to detach it from its "Arab" origins isn't quite right—it is an attempt to detach it, and thus Palestinians themselves, from Palestinian roots.

"Yemeni Jews first put falafel in 'pita'"

As for this claim, it's often attributed to Gil Marks: "Jews didn’t invent falafel. They didn’t invent hummus. They didn’t invent pita. But what they did invent was the sandwich. Putting it all together.” (Hilariously, the author of the interview follows this up with "With each story, I wanted to ask, but how do you know that?")

Another author (signed "Philologos") speculates (after, by the way, falsely claiming that "falafel" is the plural of the Arabic "filfil" "pepper," and that falafel is always brown, not green, inside?!):

Yet while falafel balls are undoubtedly Arab in origin, too, it may well be that the idea of serving them as a street-corner food in pita bread, to which all kinds of extras can be added, ranging from sour pickles to whole salads, initially was a product of Jewish entrepreneurship.

Shaul Stampfer cites both of these articles as further reading on the "novelty of the combination of pita, falafel balls, and salad" (FN 76, p. 198)—but neither of them cites any evidence! They're both just some guy saying something!

Marks had, however, elaborated a little bit in his 2010 Encyclopedia of Jewish Food:

Falafel was enjoyed in salads as part of a mezze (appetizer assortment) or as a snack by itself. An early Middle Eastern fast food, falafel was commonly sold wrapped in paper, but not served in the familiar pita sandwich until Yemenites in Israel introduced the concept. [...] Yemenite immigrants in Israel, who had made a chickpea version in Yemen, took up falafel making as a business and transformed this ancient treat into the Israeli iconic national food. Most importantly, Israelis wanted a portable fast food and began eating the falafel tucked into a pita topped with the ubiquitous Israeli salad (cucumber-and-tomato salad).

He references one of the pieces that Lillian Cornfeld (columnist for the English-language, Jerusalem-based newspaper Palestine Post) wrote about "filafel":

An article from October 19, 1939 concluded with a description of the common preparation style of the most popular street food, 'There is first half a pita (Arab loaf), slit open and filled with five filafels, a few fried chips and sometimes even a little salad,' the first written record of serving falafel in pita. [Marks doesn't tell you the title or page—it's "Seaside Temptations: Juveniles' Fare at Tel Aviv," p. 4.]

You will first of all notice that Marks gives us the "falafel from Yemen" story. I also notice that he calls Salat al-bundura "Israeli salad" (in its entry he does not claim that European Jewish immigrants invented it, but neither does he attribute it to Palestinian influence: the dish was originally "Turkish coban salatsi"). His encyclopedia also elsewhere contains Zionist claims such as "wild za'atar was declared a protected plant in Israel" "[d]ue to overexploitation" because of how much of the plant "Arab families consume[d]," and that Israeli cultivation of the crop yielded "superior" plants (entry for "Za'atar")—a narrative of "Arab" mismanagement, and Israeli improvement, of land used to justify settler-colonialism. He writes that Palestinians who accuse "the Jews" of theft in claiming falafel are "creat[ing] a controversy" and that "food and culture cannot be stolen," with no reflection on the context of settler-colonialism and literal, physical theft that lies behind said "controversy." This isn't relevant except that it makes me sceptical of Marks's motivations in general.

More pertinent is the fact that this quote doesn't actually suggest that this falafel vendor was Yemeni (or otherwise) Jewish, nor does it suggest that he was the first one to prepare falafel in pitas with "fried chips," "sometimes even a little salad," and "Tehina, a local mayonnaise made with sesame oil" (Cornfeld, p. 4). I think it likely that this food had been sold for a while before it was described in published writing. The idea that this preparation is "Israeli" in origin must be false, since this was before the state of "Israel" existed—that it was first created by Yemeni Jewish falafel vendors is possible, but again, I've never seen any direct evidence for it, or anyone giving a clear reason for why they believe it to be the case, and the political reasons that people have for believing this narrative make me wary of it. There were Palestinian Arab falafel vendors at this time as well.

"Chickpea falafel is a Jewish invention"

There is also a claim that falafel originated in Egypt, where it was made with fava beans; spread to the Levant, including Palestine, where it was made with a combination of fava beans and chickpeas; but that Jewish immigration to Israel caused the origin of the chickpea-only falafal currently eaten in Palestine, because a lot of Jewish people have G6PD deficiencies or favism (inherited enzymatic deficiencies making fava beans anywhere from unpleasant to dangerous to eat)—or that Jewish populations in Yemen had already been making chickpea-only falafel, and this was the falafel which they brought with them to Palestine.

As far as I can tell, this claim comes from Joan Nathan's 2001 The Foods of Israel:

Zadok explained that at the time of the establishment of the state, falafel—the name of which probably comes from the word pilpel (pepper)—was made in two ways: either as it is in Egypt today, from crushed, soaked fava beans or fava beans combined with chickpeas, spices, and bulgur; or, as Yemenite Jews and the Arabs of Jerusalem did, from chickpeas alone. But favism, an inherited enzymatic deficiency occurring among some Jews—mainly those of Kurdish and Iraqi ancestry, many of whom came to Israel during the mid 1900s—proved potentially lethal, so all falafel makers in Israel ultimately stopped using fava beans, and chickpea falafel became an Israeli dish.

Gil Marks's 2010 Encyclopedia of Jewish Food echoes (but does not cite):

Middle Eastern Jews have been eating falafel for centuries, the pareve fritter being ideal in a kosher diet. However, many Jews inherited G6PD deficiency or its more severe form, favism; these hereditary enzymatic deficiencies are triggered by items like fava beans and can prove fatal. Accordingly, Middle Eastern Jews overwhelmingly favored chickpeas solo in their falafel. (Entry for "Falafel")

The "centuries" thing is consistent with the fact that Marks believes falafel to be of Medieval origin, a claim which most scholars I've read on the subject don't believe (no documentary evidence, + oil was expensive so it seems unlikely that people were deep frying anything). And, again, this claim is speculation with no documentary evidence to support it.

As for the specific modern toppings including the Yemeni hot sauce سَحاوِق / סְחוּג (saHawiq / "zhug"), Baghdadi mango pickle عنبة / עמבה ('anba), and Moroccan هريسة / חריסה ("harissa"), it seems likely that these were introduced by Mizrahim given their place of origin.

*You might be interested to know that, despite their Jewishness mediating this borrowing, Mizrahim were during the Mandate years largely ethnically segregated from Eastern European Zionists, who were pushing to create a "new" European-Israeli Judaism separate from what they viewed as the indolence and ignorance of "Oriental" Jewishness (Hirsch p. 101).

This was evidenced in part by Europeans' attitudes towards the "Oriental" diet. Ari Ariel, summarizing Yael Raviv's Falafel Nation, writes:

Although all immigrants were thought to require culinary education as an aspect of their absorption into the new national culture, Middle Eastern Jews, who began to immigrate in increasing numbers after 1948, provoked greater anxiety on the part of the state than did their Ashkenazi co-religionists. Israeli politicians and ideologues spoke of the dangers of Levantization and stereotyped Jews from the Middle East and North Africa as primitive, lazy, and ignorant. In keeping with this Orientalism, the state pressured Middle Easterners to change their foodways and organized cooking demonstrations in transit camps and new housing developments. (Book review, Israel Studies Review 31.2 (2016), p. 169.)

See also Esther Meir-Glitzenstein, "Longing for the Aromas of Baghdad: Food, Emigration, and Transformation in the Lives of Iraqi Jews in Israel in the 1950s," in Jews and their Foodways:

[...] [T]he Israeli establishment was set on “educating” the new immigrants not only in matters of health and hygiene, [77] but also in the realm of nutrition. A concerted propaganda effort was launched by well-baby clinics, kindergartens, schools, health clinics, and various organizations such as the Women’s International Zionist Organization (WIZO) and the Organization of Working Mothers in order to promote the consumption of milk and dairy products, in particular. [78] (These had a marginal place in Iraqi cuisine, consumed mainly by children.) Arab and North African cuisines were criticized for being not sufficiently nutritious, whereas the Israeli diet was touted as ideal, as it was western and modern. […] [T]he assault on traditional Middle Eastern cuisines reflected cultural arrogance yet another attempt to transform immigrants into “new Jews” in accordance with the Zionist ethos.

Thus, European table manners were presented as the norm. Eating with the hands was equated with primitive behavior, and use of a fork and knife became the hallmark of modernity and progress. (pp. 100-101)

[77. On health matters, see Davidovich and Shvarts, “Health and Hegemony,” 150–179; Sahlav Stoller-Liss, “ ‘Mothers Birth the Nation’: The Social Construction of Zionist Motherhood in Wartime in Israeli Parents’ Manuals,” Nashim 6 (Fall 2003), 104–118.]

[78. On propaganda for drinking milk and eating dairy products, see Mor Dvorkin, “Mif’alei hahazanah haḥinukhit bishnot ha’aliyah hagedolah: mekorot umeafyenim” (seminar paper, Ben-Gurion University, 2010).]

**On the desire to shed "old, European" "Jewish" identity and take on a "new, Oriental" "Hebrew" one, and the contradictory impulses to use Palestinian Arabs as models in this endeavour and to claim that they needed to be "corrected," see:

Itamar Even-Zohar, "The Emergence of a Native Hebrew Culture in Palestine, 1882—1948"

Dafna Hirsch, "We Are Here to Bring the West, Not Only to Ourselves": Zionist Occidentalism and the Discourse of Hygiene in Mandate Palestine"

Ofra Tene, "'The New Immigrant Must Not Only Learn, He Must Also Forget': The Making of Eretz Israeli Ashkenazi Cuisine."

#sorry for this but you should've known better than to ask me about falafel at this stage in my life#falafel research saga

146 notes

·

View notes

Link

0 notes

Text

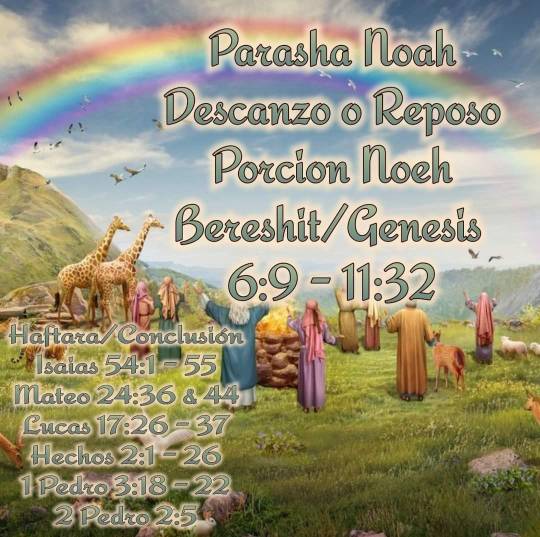

🍷Shabbat Shalum🍞

(Versión Natzarena)

📜Génesis/Bereshit 6:9-22

Parashah 2: Noah/Noach (Noé) Bereshit 6:9-11:32 Y éstas son las generaciones de Noaj. Noaj era un hombre recto y siendo perfecto en su generación, Noaj era bien placentero a YHWH.

[10]Noaj engendró tres hijos, Shem, Ham, y Yefet.

[11]La tierra estaba corrompida ante YHWH, la tierra estaba llena de violencia.

[12]YHWH tzebaot vio la tierra, y estaba corrompida; porque toda carne había corrompido su camino sobre la tierra.

[13]Y YHWH dijo a Noaj: "El tiempo de todo hombre ha venido ante mí, pues a causa de ellos la tierra está llena de iniquidad. Yo los destruiré a ellos y a la tierra.

[14]Hazte un arca de madera cuadrada; harás el arca con compartimientos y la cubrirás con brea por dentro y por fuera.

[15]Aquí está como la harás; el largo del arca será de 450 pies, su ancho setenta y cinco pies y su altura cuarenta y cinco pies.

[16]Estrecharás el arca cuando la estés haciendo, y en un cubito hacia arriba tú la terminarás. Pon una puerta a su lado, y la edificarás con piso de abajo, segundo y tercero la harás.

[17]"Entonces Yo mismo traeré la inundación de agua sobre la tierra para destruir de debajo del cielo toda cosa viviente que respira; todo en la tierra será destruido.

[18]Pero Yo estableceré un Pacto contigo; tú entrarás dentro del arca, tú, tus hijos, tu esposa y las esposas de tus hijos contigo.

[19]"Y de todo ganado y de todas las cosas que se arrastran y de toda bestia salvaje, aun de toda carne tú traerás por pares de todos, dentro del arca, para que puedas alimentarlos contigo; ellos serán macho y hembra.

[20]De cada clase de criatura que vuela, cada clase de animal de crianza, en cada clase de animal que se arrastra en la tierra, por parejas vendrán a ti, para que puedan mantenerse vivos.

[21]También toma de todas las clases de alimento, y recógelas para ti; será alimento para ti y para ellos."

[22]Esto es lo que Noaj hizo; él hizo todo lo que YHWH tzebaot le ordenó.

Génesis/Bereshit 7:1-24

[1]YHWH dijo a Noaj: "Entra en el arca, tú y toda tu familia; porque Yo he visto que tú en esta generación eres justo delante de mí.

[2]De todo animal limpio tomarás siete parejas, y de los animales inmundos, una pareja;

[3]y de las criaturas limpias que vuelan del cielo, por sietes, macho y hembra; y de las criaturas inmundas que vuelan, por pares, macho y hembra, para mantener zera en toda la tierra.

[4]Porque en siete días más Yo causaré que llueva sobre la tierra por cuarenta días y cuarenta noches; Yo raeré de la tierra a todo ser viviente que Yo he hecho."

[5]Noaj hizo todo lo que YHWH le ordenó hacer.

[6]Noaj tenía 600 años de edad cuando el agua inundó la tierra.

[7]Noaj entró en el arca con sus hijos, su esposa y las esposas de sus hijos, a causa de las aguas de inundación.

[8]De las criaturas limpias que vuelan, y del ganado limpio y del ganado inmundo, y de todas las cosas que se arrastran en la tierra,

[9]entraron y fueron a Noaj en el arca, como YHWH había ordenado a Noaj.

[10]Después de siete días el agua inundó la tierra.

[11]En el vigésimo séptimo día del segundo mes de los 600 años de la vida de Noaj todas las fuentes del gran abismo fueron rotas, y las ventanas del cielo fueron abiertas.

[12]Llovió en la tierra por cuarenta días y cuarenta noches.

[13]En el mismo día que Noaj entró en el arca con Shem, Ham y Yefet, los hijos de Noaj, la esposa de Noaj y las tres esposas de los hijos de Noaj que los acompañaban;

[14]y de toda bestia salvaje por su especie, todo animal de cría de todas las especies, toda cosa que se arrastra por la tierra de todas las especies, y toda criatura que vuela por su especie.

[15]Ellos entraron y fueron a Noaj en el arca, parejas de toda clase, toda carne, en los cuales hay aliento de vida, como YHWH ordenó a Noaj.

[16]Aquellos que entraron, macho y hembra, de toda carne como YHWH le había ordenado; y YA

YHWH los encerró adentro.

[17]La inundación estuvo cuarenta días en la tierra; el agua creció muy alto e hizo flotar el arca; así que fue levantada de la tierra.

[18]El agua inundó la tierra y creció más honda, hasta que el arca flotaba en la superficie del agua.

[19]El agua sobrecogió la tierra con gran fortaleza; todas las montañas debajo del cielo fueron cubiertas;

[20]el agua cubrió las montañas por más de veintidós pies y medio.

[21]Todos los seres que se movían en la tierra perecieron - criaturas que vuelan, animales de crianza, otros animales, insectos, y todo ser humano,

[22]todas las cosas que tienen aliento de vida; cualquier cosa que había en tierra seca murió.

[23]El borró a todo ser viviente de la faz de la tierra - no sólo seres humanos, sino animales de crianza, animales que se arrastran y criaturas que vuelan. Ellos fueron raídos de la tierra; solamente Noaj fue dejado, junto con aquellos que estaban con él en el arca.

[24]El agua retuvo su poder sobre la tierra por 150 días.

Génesis/Bereshit 8:1-22

[1]Y YHWH se acordó de Noaj, de toda bestia salvaje y todo animal de crianza, y todas las criaturas que vuelan, y todas las cosas que se arrastran, tantas como había con él en el arca, y YHWH causó un viento pasar por sobre la tierra, y el agua se quedó.

[2]También las fuentes del abismo y las ventanas del cielo fueron cerradas, la lluvia del cielo fue restringida,

[3]y el agua regresó de completamente cubrir la tierra. Fue después de 150 días que el agua bajó.

[4]En el vigésimo séptimo día del séptimo mes el arca vino a reposar en las montañas del Ararat

[5]El agua siguió bajando hasta el décimo mes; en el primer día del décimo mes las cumbres de las montañas fueron vistas.

[6]Después de cuarenta días Noaj abrió la ventana del arca que él había edificado;

[7]y envió afuera al cuervo para ver si el agua había cesado, el cual voló y no regresó hasta que el agua fue seca de la tierra.

[8]Luego él envió una paloma para ver si el agua se había ido de la superficie de la tierra.

[9]Pero la paloma no encontró lugar para que sus patas descansaran, así que ella regresó a él en el arca, porque el agua todavía cubría la tierra. El la puso en sus manos, la tomó y la trajo a él en el arca.

[10]Esperó otros siete días y de nuevo envió la paloma desde el arca.

[11]La paloma vino a él al anochecer, y allí en su pico había una hoja de olivo, una ramita en su boca, así que Noaj supo que el agua había cesado de sobre la tierra.

[12]El esperó aún otros siete días y envió la paloma, y ella no regresó más a él.

[13]Para el primer día del primer mes del año 601 de la vida de Noaj el agua había menguado de la tierra; y Noaj removió la cubierta del arca cual él había hecho, y vio que el agua había menguado de la faz de la tierra.

[14]Fue en el vigésimo séptimo día del segundo mes que la tierra estaba seca.

[15]Y YHWH habló a Noaj, diciendo:

[16]"Salgan del arca, tú, tu esposa, tus hijos y las esposas de tus hijos contigo.

[17]Traigan con ustedes toda carne que tienen con ustedes - criaturas que vuelan, animales de crianza, y toda cosa que se arrastra en la tierra - para que ellos puedan proliferar en la tierra, ser fructíferos y multiplicarse en la tierra."

[18]Así que Noaj salió con sus hijos, su esposa y las esposas de sus hijos,

[19]todos los animales, toda cosa que se arrastra y toda criatura que vuela, lo que se moviera en la tierra, conforme a sus familias, salieron del arca.

[20]Noaj edificó un altar a YHWH. Entonces tomó de todo animal limpio y de toda criatura que vuela limpia, y ofreció ofrendas quemadas en el altar.

[21]YHWH olió el aroma dulce, y YHWH consideró, y dijo: "Yo nunca jamás maldeciré la tierra a causa de los hombres, puesto que las imaginaciones del corazón de la persona son torcidas desde su juventud; Yo no destruiré jamás toda criatura viviente como he hecho.

[22]Todos los días de la tierra, no cesará el tiempo de la siembra y de la cosecha, frío y calor, verano y primavera, y día y noche."

Génesis/Bereshit 8:1-22

[1]Y YHWH se acordó de Noaj, de toda bestia salvaje y todo animal de crianza, y todas las criaturas que vuelan, y todas las cosas que se arrastran, tantas como había con él en el arca, y YHWH causó un viento pasar por sobre la tierra, y el agua se quedó.

[2]También las fuentes del abismo y las ventanas del cielo fueron cerradas, la lluvia del cielo fue restringida,

[3]y el agua regresó de completamente cubrir la tierra. Fue después de 150 días que el agua bajó.

[4]En el vigésimo séptimo día del séptimo mes el arca vino a reposar en las montañas del Ararat

[5]El agua siguió bajando hasta el décimo mes; en el primer día del décimo mes las cumbres de las montañas fueron vistas.

[6]Después de cuarenta días Noaj abrió la ventana del arca que él había edificado;

[7]y envió afuera al cuervo para ver si el agua había cesado, el cual voló y no regresó hasta que el agua fue seca de la tierra.

[8]Luego él envió una paloma para ver si el agua se había ido de la superficie de la tierra.

[9]Pero la paloma no encontró lugar para que sus patas descansaran, así que ella regresó a él en el arca, porque el agua todavía cubría la tierra. El la puso en sus manos, la tomó y la trajo a él en el arca.

[10]Esperó otros siete días y de nuevo envió la paloma desde el arca.

[11]La paloma vino a él al anochecer, y allí en su pico había una hoja de olivo, una ramita en su boca, así que Noaj supo que el agua había cesado de sobre la tierra.

[12]El esperó aún otros siete días y envió la paloma, y ella no regresó más a él.

[13]Para el primer día del primer mes del año 601 de la vida de Noaj el agua había menguado de la tierra; y Noaj removió la cubierta del arca cual él había hecho, y vio que el agua había menguado de la faz de la tierra.

[14]Fue en el vigésimo séptimo día del segundo mes que la tierra estaba seca.

[15]Y YHWH habló a Noaj, diciendo:

[16]"Salgan del arca, tú, tu esposa, tus hijos y las esposas de tus hijos contigo.

[17]Traigan con ustedes toda carne que tienen con ustedes - criaturas que vuelan, animales de crianza, y toda cosa que se arrastra en la tierra - para que ellos puedan proliferar en la tierra, ser fructíferos y multiplicarse en la tierra."

[18]Así que Noaj salió con sus hijos, su esposa y las esposas de sus hijos,

[19]todos los animales, toda cosa que se arrastra y toda criatura que vuela, lo que se moviera en la tierra, conforme a sus familias, salieron del arca.

[20]Noaj edificó un altar a YHWH. Entonces tomó de todo animal limpio y de toda criatura que vuela limpia, y ofreció ofrendas quemadas en el altar.

[21]YHWH olió el aroma dulce, y YHWH consideró, y dijo: "Yo nunca jamás maldeciré la tierra a causa de los hombres, puesto que las imaginaciones del corazón de la persona son torcidas desde su juventud; Yo no destruiré jamás toda criatura viviente como he hecho.

[22]Todos los días de la tierra, no cesará el tiempo de la siembra y de la cosecha, frío y calor, verano y primavera, y día y noche."

Génesis/Bereshit 10:1-32

[1]Aquí está la genealogía de los hijos de Noaj - Shem, Ham y Yefet; hijos fueron nacidos a ellos después de la inundación.

[2]Los hijos de Yefet[38] fueron Gomer, Magog, Madai, Yavan, Elisha, Tuval, Meshej y Tiras.

[3]Los hijos de Gomer fueron Ashkenaz, Rifat y Torgamah.

[4]Los hijos de Yavan fueron Elishah, Tarshish, Kittim y Dodanim.

[5]De estos las islas de los Gentiles fueron divididas en sus tierras, cada una de acuerdo a su idioma, conforme a sus tribus en sus naciones.

[6]Los hijos de Ham fueron Kush, Mitzrayim, Put y Kenaan.

[7]Los hijos de Kush fueron Seva, Havilah, Savta, Ramah y Savteja. Los hijos de Ramah fueron Sheva y Dedan.

[8]Kush engendró a Nimrod, él comenzó a ser un gigante sobre la tierra.

[9]El fue un cazador gigante delante de YHWH - por esto la gente dice: "Como Nimrod, un cazador gigante delante de YHWH"

[10]Su reino comenzó con Bavel, Erej, Akkad y Kalneh, en la tierra de Shinar.

[11]Ashur salió de esa tierra y edificó a Ninveh, la ciudad de Rejovot, Kelaj,

[12]y Resen entre Ninveh y Kelah - esto es la gran ciudad.

[13]Mitzrayim engendró a Ludim, los Anamin, los Lehavim, los Naftujim,

[14]los Patrusim, los Kaslujim (de quien vinieron los Plishtim) y los Kaftorim.

[15]Kenaan engendró a Tzidon su primogénito, Het,

[16]los Yevusi, los Emori, los Girgashi,

[17]los Hivi, los Arki, los Sini,

[18]los Arvadi, los Tzemari y los Hamati. Después, las familias de los Kenaani fueron dispersas.

[19]El territorio de los Kenaani era desde Tzidon, en dirección a Gerar, hacia Azah; sigue hacia Sedom, Amora, Dama y Tzevoyim, hasta Lesha.

[20]Estos fueron los hijos de Ham, conforme a sus familias y lenguas, en sus tierras y en sus naciones.

[21]Hijos fueron nacidos a Shem, antepasados de los hijos de Ever y hermano mayor de Yefet.

[22]Los hijos de Shem fueron Elam, Ashur, Arpajshad, Lud y Aram y Keinan.

[23]Los hijos de Aram fueron Utz, Hul, Geter y Mash.

[24]Arpajshad engendró a Keinan y Keinan engendró a Shelaj, y Shelaj engendró a Ever.

[25]A Ever le nacieron dos hijos. Uno fue dado el nombre de Peleg [división], porque durante su vida la tierra fue dividida. El nombre de su hermano fue Yoktan.

[26]Yoktan engendró a Almodad, Shelef, Hatzar-Mavet, Yeraj

[27]Hadoram, Uzal, Diklah,

[28]Avimael, Sheva,

[29]Ofir, Havilah y Yoav - todos fueron hijos de Yoktan.

[30]El territorio de ellos se extendía desde Mesha, continuaba hacia Sefar, a las montañas en el este.

[31]Estos fueron los hijos de Shem, conforme a sus familias y lenguas, en sus tierras y sus naciones.

[32]Estas fueron las tribus de los hijos de Noaj, conforme a sus generaciones, en sus naciones. De ellos las islas de Gentiles se esparcieron en la tierra después de la inundación.

Génesis/Bereshit 11:1-32

[1]Toda la tierra usaba la misma lengua, las mismas palabras.

[2]Sucedió que ellos viajaron desde el este, y encontraron una llanura en la tierra de Shinar y vivieron allí.

[3]Ellos se dijeron uno al otro: "Vamos, hagamos ladrillos y los horneamos en el fuego." Así que tuvieron ladrillos por piedra y asfalto por mortero.

[4]Ellos dijeron: "Vamos, edifiquemos una ciudad con una torre que tenga su cúspide llegando al cielo, para podernos hacer un nombre para nosotros mismos y no seamos esparcidos por la tierra.

[5]Y YHWH descendió para ver la ciudad y la torre que la gente estaba edificando.

[6]YHWH dijo: "Mira, la gente se ha unido, ellos tienen una misma lengua, ¡y mira lo que están empezando a hacer! ¡A este ritmo nada de lo que se han empeñado en hacer será imposible para ellos!

[7]Ahora, pues, descendamos y confundamos su lenguaje, para que no pueda entenderse el habla del uno al otro."

[8]Así que de allí YHWH los esparció por toda la faz de tierra, y ellos dejaron de edificar la ciudad y la torre.

[9]Por esta razón es llamada Bavel [confusión] - porque allí YHWH confundió los labios de toda la tierra, y de allí YHWH los esparció por toda la tierra.

[10]Aquí está la genealogía de Shem. Shem era de 100 años de edad cuando engendró a Arpajshad dos años después de la inundación.

[11]Después que Arpajshad nació, Shem vivió 500 años y tuvo hijos e hijas y murió.

[12]Arpajshad vivió 135 años y engendró Keinan.

[13]Después que Keinan nació, Arpajshad vivió otros 430 años y engendró hijos e hijas y murió. Y Keinan vivió 130 años y engendró Shelaj; y Keinan vivió después que Shelaj nació 330 años y engendró hijos e hijas y murió.

[14]Shelaj vivió 130 años y engendró a Ever.

[15]Después que Ever nació Shelaj vivió otros 330 años y engendró hijos e hijas y murió

[16]Ever vivió 134 años y engendró a Peleg.

[17]Después que Peleg nació, Ever vivió otros 370 años y engendró hijos e hijas y murió.

[18]Peleg vivió 130 años y engendró a Reu.

[19]Después que Reu nació, Peleg vivió 209 años y engendró hijos e hijas, y murió.

[20]Reu vivió 132 años y engendró a Serug.

[21]Después que Serug nació, Reu vivió otros 207 años y engendró hijos e hijas, y murió.

[22]Serug vivió 130 años y engendró a Najor.

[23]Después que Najor nació, Serug vivió otros 200 años y engendró hijos e hijas, y murió.

[24]Najor vivió 79 años y engendró a Teraj.

[25]Después que Teraj nació, Najor vivió otros 129 años y engendró hijos e hijas, y murió.

[26]Teraj vivió setenta años y engendró a Avram, a Najor y a Haran.

[27]Aquí está la genealogía de Teraj. Teraj engendró a Avram, a Najor y a Haran; y Haran engendró a Lot.

[28]Haran murió en la presencia de su padre Teraj en la tierra donde nació, en el país de los Kasdim.

[29]Entonces Avram y Najor tomaron esposas para ellos mismos. El nombre de la esposa de Avram era Sarai, y el nombre de la esposa de Najor, Milkah la hija de Haran. El fue el padre de Milkah y de Yiskah.

[30]Sarai era estéril - ella no tenía hijo.

[31]Teraj tomó a su hijo Avram, a Lot el hijo de su hijo Haran, y a Sarai su nuera, la esposa de su hijo Avram; y salió de Ur de los Kasdim para ir a la tierra de Kenaan. Pero cuando llegaron a Haran, ellos se quedaron allí.

[32]Y todos los días de Teraj en Haran fueron 205 años, y Teraj murió en Haran. Haftarah Noaj: Yeshayah (Isa_52:13 - Isa_55:5) Lecturas sugeridas del Brit Hadashah para la Parashah Noaj: Mattityah (Mat_24:36-44); Luc_17:26-37; Hch_2:1-16; Hch_1:1-26 Kefa (1Pe_3:18-22); 2 Kefa (2Pe_2:5)

👑HalleluYah👑

1 note

·

View note

Text

Divorce and Female Vulnerability in American Society

American society has made substantial progress in achieving gender equality in many aspects of social life. However, these efforts are still insufficient as females remain a vulnerable group due to the existing regulations, policies, and social norms. U.S. women face numerous challenges in such spheres as marriage and divorce (Yefet, 2020). Exit from marriage is associated with diverse issues…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Link

When Tanzanian community developer and environmentalist Fabian Bulugu began a master’s degree program at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem in 2017, he wanted to spend his spare time learning how Israelis work their magic in the desert soil.

“I was very interested in agriculture because Israelis came to Tanzania in the 1960s to help us grow crops at Lake Victoria with Israeli irrigation technologies,” he explains to ISRAEL21c. “I visited those sites and the farmers are still thankful to the Israeli people to this day.”

He heard about a hydroponic gardening project at the Jerusalem Botanical Gardens run by Kaima, an organization that uses organic farming to give Israeli high-school dropouts an income and a fresh start on life.

“It amazed me to see how engaged the youth were,” Bulugu tells ISRAEL21c.

He began volunteering there once a week and then at Kaima Beit Zayit, the flagship farm of the NGO, which now encompasses four “sister” farms in other Israeli locales. “With my interest in climate change and in youth empowerment I felt I needed to do something to help youth,” he said.

Inspired by the successful work of Kaima founder Yoni Yefet-Reich, Bulugu is now piloting a Kaima sister farm in his native country in coordination with local and international NGOs.

“Fabian came as a volunteer for almost a year once or twice a week, and at the end of the year he came to me and said, ‘Now I know what I want to do. I want to take this to Tanzania,’” Yefet-Reich recalls.

A gift from Israel

Bulugu tweaked the model to fit the situation in the eastern African country of 55.5 million.

“In Tanzania we have only mandatory schooling up to age 15 and so we don’t really have dropouts,” he explains.

“We have different problems, especially with youth unemployment after the age of 15 after primary school ends. They have no skills to prepare them for a profession. So I wanted to bring a gift from Israel to empower these youth.”

Tanzania is blessed with lakes, rivers and arable land perfect for agriculture. In addition to produce such as tomatoes, Bulugu plans for his Kaima Village to raise maize, rice and sunflowers.

“After the youth learn the basics on our farm for about a year, we want to set them up with microfinancing and guidance so they can establish their own farms and other young adults can learn from them. It’s a cascading model.”

He applied for NGO status in Tanzania, secured a plot of land and necessary certifications, and recruited four additional founding members to start getting the farm set up and known in the community.

Bulugu then returned to Israel early this year to complete his degree in Glocal Community Development Studies and to complete onsite training at Kaima Beit Zayit, where he excitedly shared pictures of the farm plot with the staff and young farmers.

“Fabian has a very good connection with people; all the youth here love him,” Yefet-Reich tells ISRAEL21c.“He has lots of experience with NGOs in Tanzania so I knew he had the ability to do this. When he came back here to finish his degree we started working hard to make it happen.”

Yefet-Reich accompanied Bulugu to meetings at the Jewish Agency, Tevel b’Tzedek and other potential partners to gauge interest in helping get the Kaima Tanzania youth empowerment program off the ground.

“It’s something we always wished would happen — to see our model duplicated all over the world. We’re so happy about it,” says Yefet-Reich.

“Our own team hopes to send Kaima Beit Zayit alumni and our newly formed Kaima Center for Economic Development and Educational Training staff to Tanzania, possibly in the summer or fall, to assess the model’s implementation.”

As part of his master’s program, Bulugu also interned with the Israeli NGO Fair Planet. “They do wonderful work training farmers and improving agricultural practices in Ethiopia. Israeli people are hard workers,” he says.

Upon his return to Tanzania in April, Bulugu began formal recruiting of young employees. He also drew up long-term plans.

“I want this to be something the government will want to be involved in, so we want to have data to show the government that it’s worth funding. We will look at data such as the cost of production per tomato, for instance, and also data on outcomes for participants after a few years,” says Bulugu.

Looking farther into the future, he hopes Kaima Tanzania will expand to include a fish farm.

“Fish is very expensive in Tanzania. If we set up a site on our farm, they can use the water for irrigation and to raise fish as an added value. Everything is possible,” Bulugu says.

For more information, click here

11 notes

·

View notes

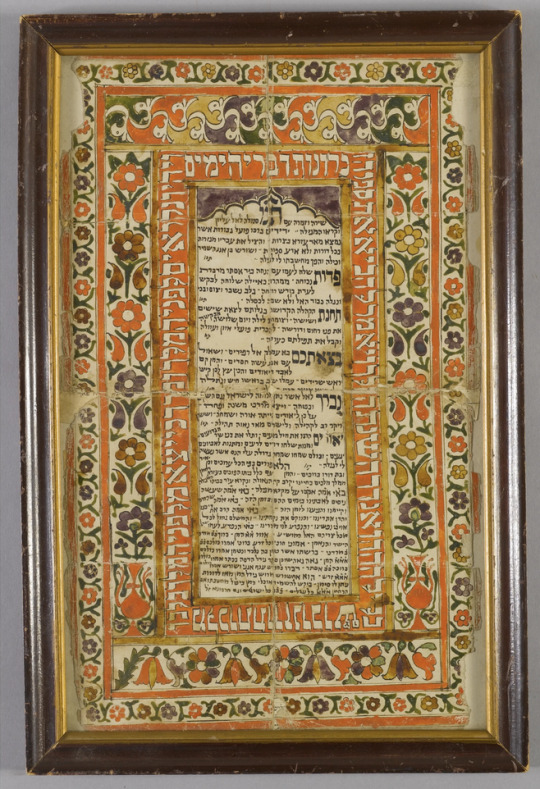

Photo

Tenu Shira (Hymn for Purim holiday), [Iranian Kurdistan: early 20th century]

On the holiday of Purim, before the reading of the Esther Scroll, members of the Iranian Kurdish Jewish community recited a special pizmon (liturgical hymn) authored by the poet Yefet Benaya. The title of the hymn, Tenu Shira, is derived from the words of the first stanza "Give song and chant, O chosen people, To God supernal."

83 notes

·

View notes

Text

Isratine : journal d'Israel / Palestine

Début avril 2018, je me lance un défi : rouler de Tel-Aviv Jaffa à Ramallah en vélo. Outre l’insolation, les courbatures, et une fatigue extrême, ce périple m’offre un nouveau regard sur la Cisjordanie, et en fin de course, une rencontre.

-----

Vélo dans une main, téléphone portable dans l’autre, je dévale péniblement les escaliers d’un petit immeuble typique de Jaffa. Une bâtisse centenaire aux plafonds immenses usés par le temps. Je traverse la cour intérieure, des braillements d’enfants résonnent sur fond de bruits de casserole. Situé au sud du quartier Ajami, le secteur est très familial. Depuis un mois, je partage un appartement avec Ameed et Khaled. Originaires de Nazareth, les deux cousins se sont installés ensemble il y a des lustres. Mais depuis quelques temps, l’ambiance est froide dans l’appartement. Trop différents, ils ne veulent clairement plus vivre ensemble. Telle un Casque bleu posté à la frontière entre le Liban et Israël, ma présence semble apaiser les tensions.

Au dehors, l’humidité lèche mes narines. La sensation de rosée matinale flotte dans l’air et caresse mon visage. Elle éveille des souvenirs de lendemain de camping derrière la maison de ma grand-mère maternelle. Cette délicieuse époque qu’est l’enfance, où dormir hors de mon lit résonnait comme une incroyable odyssée. Aujourd’hui, une tout autre aventure se dessine devant moi. Une idée qui semble absurde : rouler à vélo de Tel-Aviv à Ramallah. D’après mes souvenirs, une soixantaine de kilomètres sépare les deux villes. Rien d’insurmontable pour quiconque bouge ses gambettes de temps à autres. Mais relier ces deux localités à vélo semble dépasser toute logique. J’en ai parlé à quelques collègues de la chaîne dans laquelle je travaille : “énorme connerie” d’après eux. Ils ont sûrement raison, mais leurs remarques m’ont un peu plus motivée dans mon projet. Surtout parce qu’elles viennent des gens de la chaîne.

En sortant du bâtiment, je repense à mon besoin constant de réaliser de nouveaux défis (aberrants pour certains), me dépasser, et un peu dépasser les autres aussi. Trois ans plus tôt, déjà installée en Israël pour un stage de quelques mois, j’avais tenté Haïfa-Tel-Aviv à pied. Je m’étais arrêtée à Atlit, épuisée. Bien tenté, Ines... Aujourd’hui, ce nouveau défi est plus que bienvenu. J’ai débarquée en Israël deux mois plus tôt, assoiffée de renouveau, persuadée que Paris n’avait rien à m’offrir après 6 mois de grisaille émotionnelle. Mais je commence à tourner en rond. L’euphorie des premières semaines est un peu retombée. Je me sens censurée par mon supérieur (celui qui s’assure qu’on ne dise pas COLONIE ou OCCUPATION à l’antenne), dont l’attitude me met mal à l’aise. Et mon ex me manque. Un bon Tel-Aviv-Ramallah à deux roues s’impose donc.

Je sors du bâtiment, comblée de m’être réveillée de bonne heure pour faire autre chose que poser mes fesses sur les plages tel-aviviennes. Les deux litres d’eau enfouis dans mon sac clapotent au rythme de mes pas. J’ai préparé une salade, comme toujours, noyée dans un amas de fruits secs et quelques affaires de rechange. Je compte dormir à Ramallah. “Peut-être chez Ahmad”, me dis-je. Seule personne avec qui j’entretiens encore des contacts réguliers à Ramallah (la ville se trouve en Cisjordanie, où j’ai vécu en 2014). Il m’a convié à une soirée le soir même et il sait que je n’ai nul part où dormir. En réalité, en arrivant, je vais découvrir que non, je ne dormirai pas chez Ahmad. Et cela va tout changer pour moi. Je pose le vélo le long d’un mur, j’ouvre les trois-quatre feuilles de papier déjà broyées par mon légendaire toucher délicat. J’ai imprimé à la va-vite le trajet à suivre pour me rendre à Ramallah. En Israël, je n’aurai aucun problème d’orientation. Il suffit de rouler dos à la mer et je suis sûre de me rendre en Cisjordanie. Mais par quel checkpoint passer? Quelles routes emprunter un fois arrivée en territoires palestiniens? Sont-elles toutes ouvertes? (checkpoint fermé le mardi? Caprice de l’armée? Regain de violences? Barrière en béton? Interdit aux Palestiniens? Aux Arabes? Aux non-juifs? Aux Chinois?...). La Cisjordanie est un gruyère incompréhensible. Mais adepte du bordel, de l’improvisation totale, je n’ai pas préparé grand chose. Seulement ce vieux plan imprimé d’une encre hideuse. Il m’indique d’emprunter le checkpoint de Rantis, puis de descendre la Cisjordanie, direction Ramallah.

Sur mon téléphone, Google Maps n’annonce pas le chemin à suivre. Ou plutôt, il me recommande de rouler… pendant 3 jours. Nombreuses sont les routes palestiniennes qui n’ont pas été enregistrées par l’application. D’une ville à l’autre, c’est toujours le même scénario : elle fait passer voitures et vélos par des détours impossibles, une perte de temps effroyable. J’utiliserai donc ma bonne vieille carte, à l’ancienne. Mon téléphone me servira pour repérer ma position en cas de problème.

J’empoigne mon deux-roues d’une motivation d’acier. Premier coup de pédale, début du périple. Le vent frais marin frappe mon visage d’une claque délicieuse. Un doux début d’avril à 8 heures du matin à Jaffa. Il fait un peu froid, mais c’est agréable. La rue Yefet, habituellement chargée à bloc, n’est pas encore tout à fait réveillée. Après une demi-heure de route, je sors de la ville, petite en largeur. Tel-Aviv est bien la cité des vélos. Mais en quittant la mégalopole, j’entre dans une tout autre réalité. Je sillonne une voie étroite. Aucune place pour les deux roues sur le bas côté. Les voitures me frôlent en passant. Au loin, j’essaye déjà d’apercevoir les collines palestiniennes de Cisjordanie, mais impossible. La route semble infinie. De chaque côté, des champs s’étalent. Le paysage prend des couleurs jaune paille et verdâtre. “On dirait la Lorraine en moins beau”, me dis-je. Le temps nuageux et l’effet de pollution n’arrangent pas les choses. Une pensée stupide traverse mon esprit : “C’est pour ça qu’ils se sont battus il y a 70 ans?”.

Outre l’absence d’espace peu commode, la route est facile. Du plat à l’infini. Au total, il me faut deux heures pour traverser Israël. En milieu de matinée, les premières côtes se dessinent. Mes mollets déjà bien formés doivent redoubler d’efforts. Plusieurs kilomètres comme ça, et toujours pas de checkpoint. Je m’arrête, saisis mon téléphone : je n’ai pas encore passé la ligne verte (ligne de démarcation entre Israël et la Cisjordanie). Je reprends la route, et soudain, les petites cabanes du checkpoint se dessinent de chaque côté de la chaussée. Trois ou quatre soldates israéliennes discutent. Les battements de mon coeur accélèrent. Je crains qu’elles ne m’arrêtent, abasourdies de voir une cycliste se rendre en Cisjordanie. Mais il ne se passe rien. Elles remarquent à peine ma présence. Avec ma tête (blanche, blonde aux cheveux frisés), j’entre dans la catégorie des physiques types israéliens. D’ailleurs, les gens me prennent souvent pour une Russe dans la rue (les Russes sont très nombreux en Israël, notamment depuis leur arrivée en masse après la chute de l’URSS). Checkpoint passé, ça y est : je suis en Palestine.

Arrivée au sommet d’une petite colline, je la dévale à toute vitesse. L’histoire des heures à venir. Une lutte acharnée pendant 30 minutes à chaque montée, et la jouissance de la descente… qui dure 30 secondes. Durant la course, le vélo m’offre plus de temps pour observer, me connecter avec l’environnement et les structures urbaines, symptomatiques de la situation politique. Avec leur structure carrée à la Wisteria Lane et leurs toits orange, les colonies israéliennes sont immanquables. Les villages palestiniens, eux, sont reconnaissables grâce aux minarets des mosquées, et sont plutôt construits au pied des montagnes. Une scène se répète sans fin : à chaque fois, les colonies israéliennes sont implantées au sommet des collines. Postés dans leurs confortables miradors, les colons scrutent toute la région. Les agissements des Palestiniens sont visibles de partout et de très loin. Aussi anodins qu'ils puissent paraître, l'urbanisme et l'architecture sont les premiers outils du contrôle israélien dans la région.

En contraste à la première partie de mon voyage en Israël, le paysage est remodelé. D’une piètre médiocrité entre Tel-Aviv et Rantis, il se transforme en une petite merveille méditerranéenne. Le gris vert des oliviers plantés entre les roches sèches, envahit mes yeux. Le soleil, qui s’est soudain levé, éblouit ce tableau coloré. En dévalant une longue pente, j’admire la région. Sans trop savoir pourquoi, une vive émotion s’empare de moi : “c’est tellement beau, putain”.

Le soleil frappe mon crâne à mesure que les heures passent. Durant une pause méritée sous un olivier, j’entoure ma tête d’un châle. Je me regarde dans l’appareil photo de mon téléphone : “J’ai vraiment l’air d’une colon…”. En entrant en Cisjordanie, j’ai quitté une relative “normalité”. Ici, je m’expose à bien plus de tensions. Or, mon physique me classe directement dans la case Israélienne. En reprenant la route, lorsque certaines voitures me frôlent, la crainte traverse mon esprit : “et si un Palestinien me prenait pour une colon israélienne? Ca serait vraiment trop con…”. Mais les heures défilent, et il ne se passe rien.

Sur le chemin, je rencontre des Israéliens bien plus apeurés que moi. Une voiture militaire m’arrête dans ma course : “vous faites quoi?”, me demande une soldate avec la légendaire “douceur” locale (équivalente à une claque donnée à l’aide d’un cactus). Je réponds en anglais : “je… fais du vélo. Il y a un problème? Je ne parle pas hébreu”. Elle regarde son collègue, d’un air un peu ébahi. Elle continue, en hébreu, bien sûr : “du vélo? Ici ?” Le reste, je ne le comprends pas. Je hausse les épaules, la regarde d’un air gêné : “but, it is not forbidden…” Elle ne répond rien, et l’air exaspéré, retourne dans sa camionnette militaire. Pédaler à vélo dans la rue, un acte surréaliste dans ces territoires. Je reprends ma course. Le cagnard devient insupportable. Le soleil perce ma peau avec violence, mon visage a viré au rouge. J’ai le sentiment que ma tête va éclater sous la chaleur. Je m’arrête près d’une heure et demie. Sur le côté du sentier, j’ai repéré un arbre assez grand pour protéger mon mètre 70 du soleil brûlant. Cette pause me fait un bien fou. Une envie dingue de m’endormir pour les 10 heures à venir me submerge. Après cette vague tentative de me remettre d’un début d’insolation, je reprends la route sans grande motivation. Je n’ai pas le choix, il me reste un bon morceau à parcourir. J’enfourche le deux-roues en soufflant : “Pourquoi je n’ai pas de vélo électrique, déjà?”. Je repose mes fesses avec peine sur la selle anormalement dure. Mon popotin doit se réhabituer au supplice. “Bordel, quel enfer”. Les trois heures suivantes, les mêmes paysages se succèdent. Mais plus aucun émerveillement dans mes yeux. Je ne pense qu’à une chose… enfin débarquer dans cette foutue Ramallah. Sur le chemin, deux voitures aux plaques vertes et blanches (palestinienne) me dépassent en se foutant de moi. Le fait qu’ils me prennent pour une colon doit les motiver. Même si je suis au bout de ma vie, je les comprends un peu. J’ai vraiment une sale tronche. Étant donnés les rapports plus que tendus entre Israéliens et Palestiniens en Cisjordanie, s’ils peuvent s’offrir le plaisir de se moquer d’une galérienne de colon israélienne… why not.

Sur le chemin, une voiture, plaque jaune et bleue (israélienne) s’arrête : “Shalom” me lance un homme : “Shalom, ani lo medaveret ivrit (je ne parle pas hébreu)”. L’homme acquiesce, l’air compréhensif : “heu… vous allez bien? Vous avez besoin d’aide?” cela ressemble plus à une affirmation qu’à une question. Mon visage, rouge feu, semble exploser. Je souris : “non, merci, je fais un tour à vélo. Il fait juste un peu chaud”. “Vous allez où?”, je réponds, l’air un peu gêné : “heu… un peu plus loin, j’en ai pour 10 minutes à peine”. Il enchaîne : “Pourquoi faire du vélo?! C’est dangereux!” Je réplique : “tout va bien merci!” Il remonte dans sa voiture, en me lançant un dernier regard inquiet. “Honnêtement, non”, me dis-je, “tu as vu juste, je ne vais pas très bien”. Mais j’ai de l’énergie. J’ai encore espoir de terminer mon parcours à vélo. “Et puis j’imagine que tu n’as pas très envie de me déposer à Ramallah.”

Une heure (et des montées de collines infernales) plus tard, une bifurcation s’ouvre sur la droite. Un panneau immense est planté à l’entrée de la chaussée, avec, écrit en lettre blanche sur fond rouge en arabe, en hébreu et en anglais : “cette route mène vers la zone A, sous autorité palestinienne. L’entrée est interdite aux Israéliens, elle représente un danger pour leur vie et elle est contraire au droit israélien.” Je regarde mon Google maps, je compare avec ma carte : je dois tourner. Si je continuais tout droit, je serais toujours sur une route de la zone C (contrôle administratif et sécuritaire israélien). Moderne, lisse, agréable, séparée par des petits pointillés jaunes, et même ensoleillée. Pas un seul trou. Mais à droite, la voie est criblée de culs de poule. Grise-noire, délabrée, il semble même que le soleil ait déserté le chemin (zone A, interdite aux rayons de soleil dans le droit israélien?)

La colline mène sur une dizaine d’habitations. Elle est particulièrement pentue. Je suis déjà désabusée. Après quelques mètres, une voiture palestinienne s’arrête. Quatre hommes sortent du véhicule : “Hello! Vous avez besoin d’aide?” me demandent-il en anglais. Je suis en zone A, ils ont donc tout de suite compris que j’étais Européenne. “YES! Please!”

Enfin, je pose les pieds à Ramallah. Finalement, je n’aurai pas fait tout le chemin à vélo. Une dizaine de minutes en voiture ont achevé ma course. Je l’avoue, pour la première fois dans ce texte. J’ai toujours omis cette dernière partie de mon voyage, trop fière d’assurer que “oui, bien sûr, j’ai fait tout le chemin sans aucune aide”, ravie de voir les yeux impressionnés de mes interlocuteurs.

Je me pose dans le premier café sur le chemin. Un lieu plutôt hype, décoré comme un jardin à l’anglaise. Mal habillée, mal coiffée, toujours aussi rouge, l’air desséchée, je pue. Je suis aux antipodes des codes ramallawis et des codes arabes en général. Avec un petit air honteux, je m’assois loin des autres clients. Mon vélo est resté dehors, sans cadenas. Ce n’est plus Tel-Aviv, ici, “personne ne le prendra”, m’affirme un serveur. Ahmad débarque, le sourire éclatant. Plus de trois ans sans le voir. Je refuse de le prendre dans mes bras : “I smell so bad !” Il s’assoit, curieux de découvrir le café où nous nous trouvons, trop “girly” pour lui. Il est bien plus branché bars à bières. Pendant une heure, on se refait les trois ans passés et les 10 heures de presque enfer que je viens de vivre : “Ahmad, can I take a shower at your place please?” il répond : “Of course! But tonight, you cannot sleep there, my cat did shit in the room. Anyway… you will sleep in an apartment with French people. Is it ok?” Je réponds, juste soulagée de pouvoir prendre une douche d’ici peu : “oh yeah yeah! That’s nice from them!”

La soirée est organisée à Birzeit, un petit village chrétien coquet à 10 minutes en voiture de Ramallah. En quatre roues, cette fois, pas à vélo. Plus jamais. Comme une sensation de gueule de bois, je refuse de penser à cet objet maudit pour les heures qui viennent. “Who is organizing the party?” Ahmad me répond : “German people studying in Birzeit”. Outre le petit village, Birzeit est surtout connue pour son immense université, légèrement excentrée. Un programme de langue arabe y accueille des étrangers venus du monde entier.

Arrivés à destination, je descends des petits escaliers en suivant Ahmad. Un chemin étroit mène sur une terrasse noyée de plantes. Au milieu, une grande table est installée pour accueillir une vingtaine de personnes. “Ines!” s’écrit Ahmad, “those are the French people”.

Je me dirige vers la terrasse, quand un mec m’arrête : “Hi! I am Adam!” Pas d’une beauté frappante, mais plutôt mignon. Je souris : “Hi! My name is Ines”. Son accent laisse penser qu’il est américain. Mais sa tête : totalement british. Des petits yeux malicieux, un nez imparfait, une bouche légèrement charnue. La peau blanche, une masse de cheveux sombre en bataille. Il n’est pas très grand. “Where are you from?” Il répond d’un air fier : “From Palestine”. Je suis surprise. Je n’y étais pas du tout. On parle un peu, de banalités, de politique, il est plutôt drôle, assez sûr de lui. Je suis sa proie ce soir. Je ne comprendrai les habitudes de drague de ce mec que bien plus tard. Je finis par m’éclipser pour passer à table avec les autres. Je ne lui reparlerai plus de la soirée. Jusqu’à comprendre que les “French people” chez qui je vais dormir sont ses colocataires.

La soirée achevée, retour à Ramallah. Moi, les “French people” (Rebecca et Ghali) et Adam. Arrivés à l’appartement, les deux Français filent dans leurs chambres respectives, épuisés. Je m’assois sur le canapé avec Adam. Je ne sais plus de quoi on parle, mais il installe un petit jeu de séduction. Dans la conversation, la question de son âge survient : “j’ai 22 ans.” C’est idiot, mais mon souffle se coupe net. J'acquiesce en souriant d’un air un peu faux, tout en pensant : “ça va pas le faire. Trop jeune pour moi. J’aurais 26 ans dans un mois...” Derrière ses grandes lunettes, ses yeux ne trompent pas. Je sens qu’il en a envie. Il croit que c’est réciproque. Mais non. 22 ans, bordel. Et ce n’est pas tout. Il ne me plait pas spécialement. J’observe son jeu de séduction avec un peu d’arrogance. Ce dédain qu’on a tous connu un jour : savoir que l’autre ne pense qu’à cela, et se dire : “mouais... pourquoi pas…” Sentir qu’on a le contrôle sur la situation. Au milieu du numéro de drague, son colocataire sort de la chambre : “hum, please, can you go to the kitchen to speak?” Je souris, et me tourne vers Adam : “I will go to sleep.” Il ne se passera rien. Tant mieux, je ne suis pas déçue. Presque soulagée que son pote ait débarqué pour nous dire de la mettre en sourdine. Mais finalement, un mois plus tard, ce mec, Adam, deviendra MON mec. Pour les deux années à venir. L’effort du vélo en valait sûrement la peine.

#Israel#Palestine#Cisjordanie#Palestiniens#Israéliens#voyage#journalisme#amour#vélo#montagnes#politique#société#jeunesse#moyenorient

4 notes

·

View notes

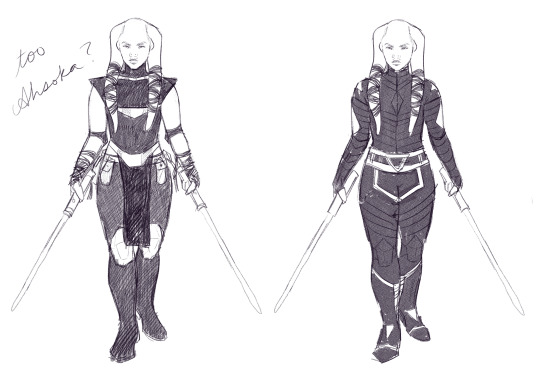

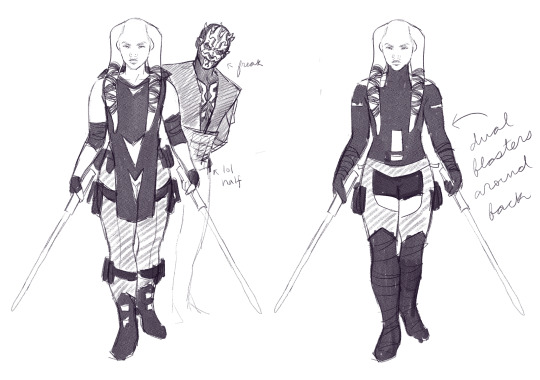

Photo

Had a little bit left in me before my hand disintegrated so I also played around with trying to design an outfit for my oc 💜

#Im like 90% sure I am not actually using any of these for them but. I am nothing if not an amateur fashion designer#myart#yefet#sw

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

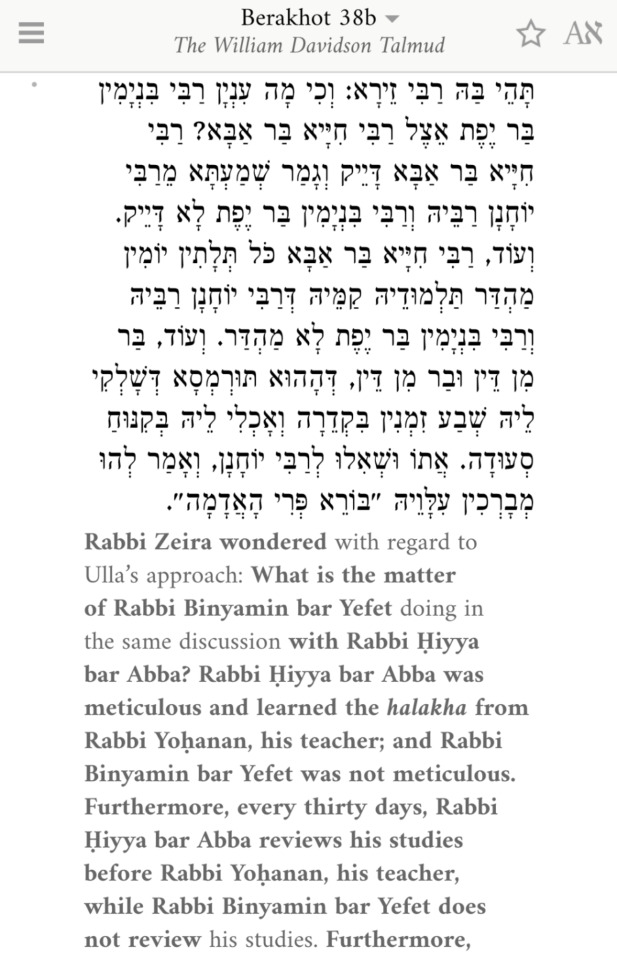

Monday 2/10, Berakhot 38: Just witnessed a murder in the Talmud

Imagine being immortalized in one of the most important sacred books in your faith and it's for being a shitty student. I mean, my imposter syndrome in grad school was bad, but at least I knew the Talmud itself wasn't going to call me out for the next THOUSAND YEARS.

#daf yomi#study#great murders of the talmud#Rabbi Zeira#Rabbi Binyamin bar Yefet#Rabbi Hiyya bar Abba

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ah yes, the three sons of Comfortable. Name, Hot, and Yefet.

#פאקינג שיטפוסט#אני בשיעור תנך והייתה לי הארה#ישראבלר#טמבלר ישראל#דג מלוח#טאמבלר עברי#ישראל#טאמבלר ישראלי#טאמבלר ישראל#טמבלר עברי

423 notes

·

View notes

Text

Haroset for Passover: an Adeni recipe

Haroset is eaten as part of the Passover Seder in all Jewish families. It symbolises the bricks and mortar used by the Israelites when they were slaves in Egypt. There are almost as many recipes for Haroset as there are Jewish communities, and each family seems to have its own variation. This recipe comes from Aden (with thanks: Sarah):

Video made by Sarah Ansbacher, with help from Chen Yefet and Mony Arovo. Recipe by Sara Arovo.

Recipe for Adeni Duka (Haroset)

Duka is the Adeni name for this delicious traditional Haroset recipe from Aden for the Pesah seder. Here is the recipe and a short video so you can make it too.

Ingredients:

Dates (Recommend Medjool)

Crushed walnuts

Wine

Lemon juice

Ginger

Cinnamon

Sugar (optional)

Method:

Put whole dates in a pot. Add a bit of hot water and simmer on a low heat and mix until it

has the consistency of porridge. Mix every so often to prevent it burning and add more water as needed. Then add wine, a dash of lemon juice, ginger, cinnamon (sugar, if you want) and crushed walnuts. Taste and add more of any ingredient as needed to taste. Cook for a further 10 minutes or so to infuse all the flavours.

Cover and cool. Then refrigerate in a sealed container.

חג פםח שמח!

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

1

דָּלִיּוֹת רֶגֶל

שָׁם בְּ-וְיָהּ דָּלָה רוֹזֶה -

הָאַגְנוֹסְטִיקָן

2

יֶפֶת הַשָּׂעִיר

שְׂעַר רֹאשׁוֹ הַקָּצוּץ -

דְּלִילָה נָחָה

1

Varicose veins

there in Via Dolorosa

the agnostic’s pain

2

The beautiful Yefet

his hair head’s is cut off -

Delilah rests

1 note

·

View note