#translatio imperi

Text

be careful which music you play

(in front of friends)

#music#life#human#rule#radio#tumlbr#blog#keinjournalist#deutsch#german#english#englisch#energy#energie#power#kraft#idee#rat#musik#internet#welt#world#africa#billie jean#note#notiz#leben#egal#hashtag#translatio imperi

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Current status, sitting here with a handful of my pre-existing Erinaen worldbuilding, a tab for notes, multiple tabs on sounds made by rats an opossums, and a playlist of Artifexian's conlang videos

We'll see what I can do before I die

#i'm hoping to at least figure out the sounds in imperial erinaen#which- i already have various words and shit in erinaen but also much like argit's name those don't nessecarily have to be great translatio#so probably going to aim for a collection of sounds that can get you close to the given words but not nessecarily perfectly aligning#the fuckers trill their vowels there's only so much that can be done#i'm sure there's *better* channels to turn to but i'm just doing this for s&g and also i enjoy artifexian#it's amazing how many points you earn by going 'i do humans and human-like aliens because it's easier for me personally'#rather than acting like intelligent life is guaranteed to be humany because we're the pinnacle of possibility or some shit

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

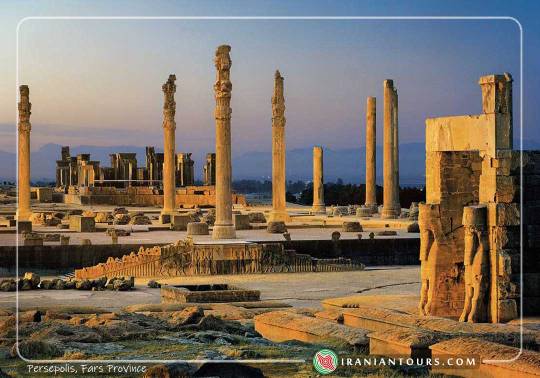

HISTORY OF ACHAEMENID IRAN

Tentative diagram of the 40-hour seminar

(in 80 parts of 30 minutes)

Prof. Muhammad Shamsaddin Megalommatis

Tuesday, 27 December 2022

--------------------------

To watch the videos, click here:

https://www.patreon.com/posts/history-of-iran-76436584

To hear the audio, click here:

-------------------------------------------

1 A - Achaemenid beginnings I A

Introduction; Iranian Achaemenid historiography; Problems of historiography continuity; Iranian posterior historiography; foreign historiography

1 B - Achaemenid beginnings I B

Western Orientalist historiography; early sources of Iranian History; Prehistory in the Iranian plateau and Mesopotamia

2 A - Achaemenid beginnings II A

Brief Diagram of the History of the Mesopotamian kingdoms and Empires down to Shalmaneser III (859-824 BCE) – with focus on relations with Zagros Mountains and the Iranian plateau

2 B - Achaemenid beginnings II B

The Neo-Assyrian Empire from Shalmaneser III (859-824 BCE) to Sargon of Assyria (722-705 BCE) – with focus on relations with Zagros Mountains and the Iranian plateau

3 A - Achaemenid beginnings III A

From Sennacherib (705-681 BCE) to Assurbanipal (669-625 BCE) to the end of Assyria (609 BCE) – with focus on relations with Zagros Mountains and the Iranian plateau

3 B - Achaemenid beginnings III B

The long shadow of the Mesopotamian Heritage: Assyria, Babylonia, Elam/Anshan, Kassites, Guti, Akkad, and Sumer / Religious conflicts of empires – Monotheism & Polytheism

4 A - Achaemenid beginnings IV A

The Sargonid dynasty and the Divine, Universal Empire – the Translatio Imperii

4 B - Achaemenid beginnings IV B

Assyrian Spirituality, Monotheism & Eschatology; the imperial concepts of Holy Land (vs. barbaric periphery) and Chosen People (vs. barbarians)

5 A - Achaemenid beginnings V A

The Medes from Deioces to Cyaxares & Astyages

The early Achaemenids (Achaemenes & the Teispids)

5 B - Achaemenid beginnings V B

- Why the 'Medes' and why the 'Persians'?

What enabled these nations to form empires?

6 A - Zoroaster A

Shamanism-Tengrism; the life of Zoroaster; Avesta and Zoroastrianism

6 B - Zoroaster B

Mithraism vs. Zoroastrianism; the historical stages of Zoroaster's preaching and religion

7 A - Cyrus the Great (Cyrus II) I A

The end of Assyria, Nabonid Babylonia, and the Medes

7 B - Cyrus the Great (Cyrus II) I B

The Nabonidus Chronicle

8 A - Cyrus the Great (Cyrus II) II A

Cyrus' battles against the Medes

8 B - Cyrus the Great (Cyrus II) II B

Cyrus' battles against the Lydians

9 Α - Cyrus the Great (Cyrus II) III A

The Battle of Opis: the facts

9 Β - Cyrus the Great (Cyrus II) III B

Why Babylon fell without resistance

10 A - Cyrus the Great (Cyrus II) IV A

Cyrus Cylinder: text discovery and analysis

10 B - Cyrus the Great (Cyrus II) IV B

Cyrus Cylinder: historical continuity in Esagila

11 A - Cyrus the Great (Cyrus II) V A

Cyrus' Empire as continuation of the Neo-Assyrian Empire

11 B - Cyrus the Great (Cyrus II) V B

Cyrus' Empire and the dangers for Egypt

12 A - Cyrus the Great (Cyrus II) VI A

Death of Cyrus; Tomb at Pasargad

12 B - Cyrus the Great (Cyrus II) VI B

Posterity and worldwide importance of Cyrus the Great

13 A - Cambyses I A

Conquest of Egypt and Cush (Ethiopia: Sudan)

13 B - Cambyses I B

Iran as successor of Assyria in Egypt, and the grave implications of the Iranian conquest of Egypt

14 A - Cambyses II A

Cambyses' adamant monotheism, his clash with the Memphitic polytheists, and the falsehood diffused against him (from Egypt to Greece)

14 B - Cambyses II B

The reasons for the assassination of Cambyses

15 A - Darius the Great I A

The Mithraic Magi, Gaumata, and the usurpation of the Achaemenid throne

15 B - Darius the Great I B

Darius' ascension to the throne

16 A - Darius the Great II A

The Behistun inscription

16 B - Darius the Great II B

The Iranian Empire according to the Behistun inscription

17 A - Darius the Great III A

Military campaign in Egypt & the Suez Canal

17 B - Darius the Great III B

Babylonian revolt, campaign in the Indus Valley

18 A - Darius the Great IV A

Darius' Scythian and Balkan campaigns; Herodotus' fake stories

18 B - Darius the Great IV B

Anti-Iranian priests of Memphis and Egyptian rebels turning Greek traitors against the Oracle at Delphi, Ancient Greece's holiest shrine

19 A - Darius the Great V A

Administration of the Empire; economy & coinage

19 B - Darius the Great V B

World trade across lands, deserts and seas

20 A - Darius the Great VI A

Rejection of the Modern European fallacy of 'Classic' era and Classicism

20 B - Darius the Great VI B

Darius the Great as the end of the Ancient World and the beginning of the Late Antiquity (522 BCE – 622 CE)

21 A - Achaemenids, Zoroastrianism, Mithraism, and the Magi A

Avesta and the establishment of the ideal empire

21 B - Achaemenids, Zoroastrianism, Mithraism, and the Magi B

The ceaseless, internal strife that brought down the Xšāça (: Empire)

22 A - The Empire-Garden, Embodiment of the Paradise A

The inalienable Sargonid-Achaemenid continuity as the link between Cosmogony, Cosmology and Eschatology

22 B - The Empire-Garden, Embodiment of the Paradise B

The Garden, the Holy Tree, and the Empire

23 A - Xerxes the Great I A

Xerxes' rule; his upbringing and personality

23 B - Xerxes the Great I B

Xerxes' rule; his imperial education

24 A - Xerxes the Great II A

Imperial governance and military campaigns

24 B - Xerxes the Great II B

The Anti-Iranian complex of inferiority of the 'Greek' barbarians (the so-called 'Greco-Persian wars')

25 A - Parsa (Persepolis) A

The most magnificent capital of the pre-Islamic world

25 B - Parsa (Persepolis) B

Naqsh-e Rustam: the Achaemenid necropolis: the sanctity of the mountain; the Achaemenid-Sassanid continuity of cultural integrity and national identity

26 A - Iran & the Periphery A

Caucasus, Central Asia, Siberia, Tibet and China Hind (India), Bengal, Deccan and Yemen

26 B - Iran & the Periphery B

Sudan, Carthage and Rome

27 A - The Anti-Iranian rancor of the Egyptian Memphitic priests A

The real cause of the so-called 'Greco-Persian wars', and the use of the Greeks that the Egyptian Memphitic priests made

27 B - The Anti-Iranian rancor of the Egyptian Memphitic priests B

Battle of the Eurymedon River; Egypt and the Wars of the Delian League

28 A - Civilized Empire & Barbarian Republic A

The incomparable superiority of Iran opposite the chaotic periphery: the Divine Empire

28 B - Civilized Empire & Barbarian Republic B

Why the 'Greeks' and the Romans were unable to form a proper empire

29 A - Artaxerxes I (465-424 BCE) A

Revolt in Egypt; the 'Greeks' and their shame: they ran to Persepolis as suppliants

29 B - Artaxerxes I (465-424 BCE) B

Aramaeans and Jews in the Achaemenid Court

30 A - Interregnum (424-403 BCE) A

Xerxes II, Sogdianus, and Darius II

30 B - Interregnum (424-403 BCE) B

The Elephantine papyri and ostraca; Aramaeans, Jews, Phoenicians and Ionians

31 A - Artaxerxes II (405-359 BCE) & Artaxerxes III (359-338 BCE) A

Revolts instigated by the Memphitic priests of Egypt and the Mithraic subversion of the Empire

31 B - Artaxerxes II (405-359 BCE) & Artaxerxes III (359-338 BCE) B

Artaxerxes II's capitulation to the Magi and the unbalancing of the Empire / Cyrus the Younger

32 A - Artaxerxes IV & Darius III A

The decomposition of the Empire

32 B - Artaxerxes IV & Darius III B

Legendary historiography

33 A - Alexander's Invasion of Iran A

The military campaigns

33 B - Alexander's Invasion of Iran B

Alexander's voluntary Iranization/Orientalization

34 A - Alexander: absolute rejection of Ancient Greece A

The re-organization of Iran; the Oriental manners of Alexander, and his death

34 B - Alexander: absolute rejection of Ancient Greece B

The split of the Empire; the Epigones and the rise of the Orientalistic (not Hellenistic) world

35 A - Achaemenid Iran – Army A

Military History

35 B - Achaemenid Iran – Army B

Achaemenid empire, Sassanid militarism & Islamic Iranian epics and legends

36 A - Achaemenid Iran & East-West / North-South Trade A

The development of the trade between Egypt, Anatolia, Mesopotamia, Iran, Turan (Central Asia), Indus Valley, Deccan, Yemen, East Africa & China

36 B - Achaemenid Iran & East-West / North-South Trade B

East-West / North-South Trade and the increased importance of Mesopotamia and Egypt

37 A - Achaemenid Iran: Languages and scripts A

Old Achaemenid, Aramaic, Sabaean and the formation of other writing systems

37 B - Achaemenid Iran: Languages and scripts B

Aramaic as an international language

38 A - Achaemenid Iran: Religions A

Rise of a multicultural and multi-religious world

38 B - Achaemenid Iran: Religions B

Collapse of traditional religions; rise of religious syncretism

39 A - Achaemenid Iran: Art and Architecture A

Major archaeological sites of Achaemenid Iran

39 B - Achaemenid Iran: Art and Architecture B

The radiation of Iranian Art

40 A - Achaemenid Iran: Historical Importance A

The role of Iran in the interconnection between Asia and Africa

40 B - Achaemenid Iran: Historical Importance B

The role of Iran in the interconnection between Asia and Europe

--------------------------------------

Download the diagram here:

#Achaemenid#Megalommatis#Ancient Iran#Old Achaemenid#Persia#Persians#Media#Orientalism#Medes#History of Ancient Iran

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Events 2.2 (before 1920)

506 – Alaric II, eighth king of the Visigoths, promulgates the Breviary of Alaric (Breviarium Alaricianum or Lex Romana Visigothorum), a collection of "Roman law".

880 – Battle of Lüneburg Heath: King Louis III of France is defeated by the Norse Great Heathen Army at Lüneburg Heath in Saxony.

962 – Translatio imperii: Pope John XII crowns Otto I, Holy Roman Emperor, the first Holy Roman Emperor in nearly 40 years.

1032 – Conrad II, Holy Roman Emperor becomes king of Burgundy.

1141 – The Battle of Lincoln, at which Stephen, King of England is defeated and captured by the allies of Empress Matilda.

1207 – Terra Mariana, eventually comprising present-day Latvia and Estonia, is established.

1428 – An intense earthquake struck the Principality of Catalonia, with the epicenter near Camprodon. Widespread destruction and heavy casualties reported.

1438 – Nine leaders of the Transylvanian peasant revolt are executed at Torda.

1461 – Wars of the Roses: The Battle of Mortimer's Cross results in the death of Owen Tudor.

1536 – Spaniard Pedro de Mendoza founds Buenos Aires, Argentina.

1645 – Scotland in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms: Battle of Inverlochy.

1653 – New Amsterdam (later renamed The City of New York) is incorporated.

1709 – Alexander Selkirk is rescued after being shipwrecked on a desert island, inspiring Daniel Defoe's adventure book Robinson Crusoe.

1814 – The last of the River Thames frost fairs comes to an end.

1848 – Mexican–American War: The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo is signed.

1850 – Brigham Young declares war on Timpanogos in the Battle at Fort Utah.

1868 – Pro-Imperial forces capture Osaka Castle from the Tokugawa shogunate and burn it to the ground.

1870 – The Seven Brothers (Seitsemän veljestä), a novel by Finnish author Aleksis Kivi, is published first time in several thin booklets.

1876 – The National League of Professional Baseball Clubs of Major League Baseball is formed.

1881 – The sentences of the trial of the warlocks of Chiloé are imparted.

1887 – In Punxsutawney, Pennsylvania, the first Groundhog Day is observed.

1899 – The Australian Premiers' Conference held in Melbourne decides to locate Australia's capital city, Canberra, between Sydney and Melbourne.

1900 – Boston, Detroit, Milwaukee, Baltimore, Chicago and St. Louis, agree to form baseball's American League.

1901 – Funeral of Queen Victoria.

1909 – The Paris Film Congress opens, an attempt by European producers to form an equivalent to the MPCC cartel in the United States.

1913 – Grand Central Terminal opens in New York City.

1 note

·

View note

Note

What exactly caused the great schism between western and eastern Christianity? Was it over some minor detail (ie what the cross should look like)? Or was it over something big?

Well, it’s worth noting that a lot of heresies within the Church throughout history have been over matters which might seem as a minor detail, but were regarded as serious matters of concern for the faithful. The hypostatic union of the Trinity is codified today, but in the early Church was a matter of fierce contention. To those who weren’t members of the Church, the difference between Miaphysitism, that Jesus had a human and divine nature that were united in a compound nature without division, and Monophysitism, that Jesus either had a singular divine nature or single nature of human and divine (thanks @racefortheironthrone), or Eutychianism which states the human nature was subsumed by the divine, seems completely esoteric and not worth excommunicating people over, but this was genuinely considered matters of spiritual life and death to honest contemplators and church theologians. So a “minor detail” might not be considered minor depending on the circumstances.

I’m no theologian, so any serious students of Roman Catholicism and/or Eastern Orthodoxy feel free to correct anything I missed, but the Great Schism is more correctly, in my view, as a boiling over of generations-long disputes, which wasn’t even seen as a schism initially, but then events continued to push and wedge them apart.

One of the principle ideas of dispute is political, regarding the doctrine of papal supremacy. According to the Roman Catholic position, the Patriarch of Rome or the Pope, the Pope claims spiritual leadership of the Church and can set doctrine, while the Eastern Orthodox position is that the power rests within the autocephalous patriarchs, of which the key five are the Patriarchs of Rome, Constantinople, Antioch, Alexandria, and Jerusalem, with the honorifics of the Patriarch of Rome being one primarily an honorific. Power to change church creed is vested within the ecumenical councils.

Nowhere was this doctrine more realized than in the Chalcedonian Church (those followers of the Ecumenical Council of Chalcedon which both Roman Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy adhere to and consider canon) with the Filioque controversy. One of the most prevalent early Christian heresies was Arianism, which asserted that God the Father was superior in being to God the Son, as God the Father begat God the Son, which was in direct opposition to the Chalcedonian conception of the Trinity. Arianism was quashed in Asia Minor, but Arian monks preached Arianism to the Gothic tribes who converted. According to the Catholic point of view The Pope added the clause “Filioque” to the Nicene Creed when sending missionaries to the Arians as an exercise of papal supremacy, to provide a clarification to the Arians that would stress the co-equal nature of God the Father and God the Son, to further eliminate Arian sentiment and bring the Gothic peoples into full communion with proper church doctrine. According to the Eastern Orthodox view, this is an unacceptable innovation of a critical piece of doctrine that can only be done within the context of an ecumenical council.

There were also cultural and ethnic concerns. The Greek East and Latin West drifted apart over plenty of issues, such as the use of unleavened bread in the Eucharist, and secular concerns between East and West. For a while the Popes were selected by various controllers of the Italian peninsula after the fall of Rome, first the Ostrogoths, then Byzantines, then Franks. The Pope had crowned Charlemagne as Holy Roman Emperor in 800 on Christmas Day, which rankled the Byzantine Empress Eirene, both individuals now claiming translatio imperii from the Roman Empire. This grew even further under the Imperial Holy Roman Empire started by Otto the Great whose dynasty would have such famous disputes like the Investiture Controversy. It all came to a head in the middle of the eleventh century. Churches practicing the Greek traditions were ordered to close or conform to Latin practices, which the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople, Michael I, retaliated by closing all Latin-practicing churches in Constantinople. A papal envoy, Cardinal Humbert (who was not a fan of Michael I or the Greek practices) came to Constantinople, ostensibly for secular talk against the Normans who had invaded southern Italy, but also to press the Emperor to reign in Michael I’s attacks on Latin practices according to the doctrine of caesaropapism which was commonly practiced by the Constantinople Church. Michael refused, Humbert laid down a papal bull of excommunication (hilariously enough, Pope Leo IX had died in the intervening time, making the bull of excommunication null and void). Michael responded by excommunicating the legates, though only the legates, not the Pope.

This wasn’t seen in contemporary times as a schism, more of a political dispute between the two most important bishops of the two most sacred cities in Christendom after Jerusalem. There was talk of reconciliation during the Papacy of Gregory VII and Urban II, especially in regards to the First Crusade which could have been used as a springboard to reunite much of the factional concerns between east and west both secular and religious. It didn’t pan out that way, and tension only got worse with the Massacre of the Latins in Constantinople, the sacking of Thessalonica by Norman invaders, culminating in the 1204 Fourth Crusade which saw the sacking of Constantinople and the establishment of the Latin Empire, among other events.

Thanks for the question, Anon.

SomethingLikeALawyer, Hand of the King

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Theory: The plot of Fallout 3 is actually a propagandized version developed by a dying Enclave.

Consider:

The main opposition of the Enclave in the Capital Wasteland is the East Coast Brotherhood, a splinter faction of a splinter faction of the U.S. military, and thus one of the only active groups that can claim a sort of translatio imperii from Old World America. When they achieve victory, the Brotherhood does so with a reclaimed superweapon that shouts bombastic Old American propaganda with every step it takes. Only a new America has the right to defeat the old America.

Municipalities outside Enclave control are very frequently portrayed as ineffectual and incompetent - see the Republic of Dave, Little Lamplight (a town run entirely by actual children), and Megaton (which just... ignores a man who sits around openly offering people money to blow everything sky-high, yet at the same time offers no resistance to a vigilante rolling in and blowing his head off) - or as hotbeds of slavery, madness, and cannibalism. All existing authority, all existing social contracts, are either corrupt, useless, or evil.

Tenpenny Tower presents a view of a world where corrupted, decadent humans cannot even conceivably coexist with a large population of ghouls. In any conflict, material or ideological, one side must slaughter the other - it is the only option.

The Lone Wanderer, in the original ending, must sacrifice themselves by entering a highly radioactive chamber, despite the presence of mutants and ghouls who could easily go in without suffering any ill effects. Non-humans will not help you.

To what end was this propaganda developed, though? The Enclave seems to be all but extinct after Fallout 3, with the only probable active groups located in the northern Midwest - another Brotherhood-controlled area, taking Tactics as broad-strokes canon.

But if we look at Fallout 4... we see a Brotherhood that is more authoritarian. A Brotherhood that categorically refuses to cooperate with Super Mutants or synths. A Brotherhood that, at some point, upgraded all their standard-issue power armor and developed the industrial and organizational capacity necessary to build a massive airship base.

This could all be coincidence. But consider this tidbit from the wiki:

By 2287, the East Coast Brotherhood had established contact with Lost Hills and has actively received support from the West. During this time, they began to make plans to establish control not only over the Capital Wasteland, but the entire Eastern Seaboard.

They contacted a bunker deep in NCR territory, to receive support from the devastated Western Brotherhood. This happened to coincide with an organization with isolationist (but, at least on the East Coast, generally benevolent) tendencies tilting into full-on imperialism within a generation.

Something to think about after the pre-War cryptofascist U.S. government seemingly drew its last breath.

135 notes

·

View notes

Text

tradnat self-care is going into palaeobotany on a government scholarship (riding the tiger) so you can identify the last cultivars of the ancient, textually attested haoma/soma plant of indo-aryan literature somewhere in shitfuck-pakhtunkhwa and smoke it while listening to tibetan bön-pop and realizing through sacred lemurian arithmetics that the roman imperial title lies, by principle of translatio imperii, with white mexicans

31 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Manners of address for popes, royalty, and nobility

Western Kim jong un read this page

Holiness Imperial and Royal Majesty (HI&RM) Imperial and Most Faithful Majesty Imperial Majesty (HIM) Apostolic Majesty (HAM) Apostolic King Catholic Monarchs Catholic Majesty (HCM) Most Christian Majesty (HMCM) Most Faithful Majesty (HFM) Orthodox Majesty (HOM) Britannic Majesty (HBM) Most Excellent Majesty Most Gracious Majesty Royal Majesty (HRM) Majesty (HM) Grace (HG) Royal Highness (HRH) Exalted Highness (HEH) Highness (HH) Most Eminent Highness (HMEH) Serene Highness (HSH) Illustrious Highness (HIll.H)

Sovereign and

mediatised families

Imperial and Royal Highness (HI&RH) Imperial Highness (HIH) Royal Highness (HRH) Grand Ducal Highness (HGDH) Grand Highness Highness (HH) Ducal Serene Highness (HDSH) Serene Highness (HSH) Serenity (HS) Illustrious Highness (HIll.H) Grace (HG) Excellency (HE)

Imperial Crown of the Austrian Empire

Imperial Crown

of the

Austrian Empire

Islamic

Amir al-umara Amir al-Mu'minin Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques Hadrat Sharif Sultanic Highness

Asian

Duli Yang Maha Mulia Great King Khan

Great Khan King of Kings Mikado Shogun Son of Heaven

See also

By the Grace of God

Divine right of kings Defender of the Faith (Fidei defensor) Defender of the Holy Sepulchre Great Catholic Monarch List of current sovereign monarchs

List of current constituent monarchs Sacred king Translatio imperii

Majesty - Wikipedia

0 notes

Text

In the opening chapter of the 1889 first volume of The Winning of the West, Theodore Roosevelt famously declared that “[d]uring the past three centuries the spread of the English-speaking peoples over the world’s waste spaces has been not only the most striking feature in the world’s history, but also the event of all others most far-reaching in its effects and its importance” (1). For Roosevelt, this “spread of the English-speaking peoples” signified both a translatio imperii from the British to the United States empires and a continuity between English speakers who, though living in different empires and far-flung locations, nevertheless shared a common language and culture. The fact that he referred to these peoples as “English-speaking” rather than Anglo-Saxon, English, or Anglo-American suggests that mutual Anglophone legibility was this inter-imperial assemblage’s defining principle.

--Marina Bilbija, “Whose Global Anglophone?” Modern Fiction Studies 64.3, Fall 2018

0 notes

Text

Tweeted

Translatio https://t.co/cHWDgpEBs5 Wow - this is very powerful. This is what English-only laws, Imperialism, colonization, & Ethnocentricism do. This is the cost of insisting embracing a new culture means giving up the old and yourself and your heritage.

— Jacqueline O Moleski (@JackieOMoleski) December 9, 2018

0 notes

Text

History of Civilization Research Paper has been published on http://research.universalessays.com/history-research-paper/world-history-research-paper/history-of-civilization-research-paper/

New Post has been published on http://research.universalessays.com/history-research-paper/world-history-research-paper/history-of-civilization-research-paper/

History of Civilization Research Paper

This sample History of Civilization Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. Like other free research paper examples it is not a custom research paper. If you need help with writing your assignment, please use research paper writing services and buy a research paper on any topic.

Abstract

The concept of civilization as it is recognizable today, emerged with the rise of historical consciousness in Europe in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and achieved global spread in the twentieth century. Civilization came to constitute a primary unit of historical discourse, in association with cognate terms such as culture, quite apart from its indication of certain morphological features of human society, such as urbanism. Broadly conceived, the notion of civilization has served two schemas of world history, the one universalist and evolutionist and the other particularistic and vitalist. Both notions have ideological implications, and were often deployed in conflicts between universalist-progressivist and conservative nationalist political creeds, the former laying emphasis on the normative and morphological continuities in human societies, while the latter stressing openness to historical becoming as well as societal and historical transformism. Quite apart from the normative implications of both notions, one valorizing abiding resources of particularist national and civilizational character and the other speaking for an open notion of progress, recent historical research has rendered possible the concrete and properly historical consideration of the notion of historical continuity beyond the boundaries of the ideological commitment of the two notions of civilization that have profoundly marked the categorization of historical material and historical periodization in general.

Outline

Introduction

Prehistory

Word and Concept

Continuities: Relativism

Novelties: Universalism

Beyond Totality

Bibliography

Introduction

The concept of civilization is inextricably connected with the conditions of its emergence, most notably with the rise of historical consciousness in Europe in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, as well as the globalization of this form of historical understanding and correlative forms of intellectual practice. The concept is complex and imprecise in its definition, but ubiquitous in its uses, and inextricably imbricated with other categories by which historical materials are organized, such as culture, nation, and race. Apart from designating certain morphological features of human society, particularly with reference to urbanism and urbanity, civilization has been a schema for historical categorization and for the organization of historical materials. Here it has generally taken two forms, the universalist evolutionist, and the romantic particularist. The latter was tending to regain, in the ascendant context of identity politics, a certain hegemonic primacy worldwide at the close of the twentieth century. In all, the concept of civilization forms a crucial chapter in the conceptual, social, and political history of history; it, or its equivalents are presupposed, implicitly or explicitly, in the construal and writing of almost all histories.

Prehistory

The mental and social conditions for speaking about civilization in a manner recognizable in the year 2000 were not available before the middle of the eighteenth century. Hitherto, in Europe as elsewhere, large-scale and long-term historical phenomena, which later came to be designated as civilizations, had been categorized in a static manner that precluded the consciousness of directional or vectorial historicity as distinct from the mere register of vicarious change.

Hitherto, the succession of large-scale historical phenomena, such as Romanity or Islam, had been regarded (1) typologically, most specifically in the salvation-historical perspective of monotheistic religious discourse, in which successive events are taken for prefigurations and accomplishments of each other; (2) in terms of the regnal succession of world empires; and (3) in the genre of regnal succession, which started with the Babylonian king lists and the earliest stages of Chinese historical writing, and culminated in medieval Arabic historical writing. Not even the schema of state cycles evolved by the celebrated Ibn Khaldun (d. 1406), where civilization (’umrân) was quasisociologically identified with various organizational forms of human habitation and sociality, could meaningfully escape from this finite repertoire of possible historical conceptions.

In the perspective of typology, the continuity of historical phenomena was expressed in the repetition of prophecies successively reaffirming divine intent and inaugurating a final form of order whose telos would be the end of time. Thus the Jewish prophets repeat each other and are all figures for Abraham; Jesus is at once the repetition and termination of this unique cycle of terrestrial time and is prefigured in Jewish prophecies. Muhammad is the final accomplishment and the consummation of earlier prophetic revelations, prefigured in Jewish and Christian scriptures; his era inaugurates the consummation of time with the Apocalypse. The structure of time in the Talmud, in the Christian writings of Eusebius (d. 339), of Augustine’s Spanish pupil Orosius (fl. 418), of Bernard de Clairvaux (1153), as in Muslim writings such as Muhammad’s biography by Ibn Ishâq (d. after 761), or the universal histories of Tabarî (d. 923) and Ibn Kathîr (d. 1373) is homologous.

All but Jewish typology is independent of ethnic origin or geographical location, and construes historically significant units as religious communities of ecumenical description. This yields the second mode of organizing historical phenomena, the regnal. Thus, the regnal categorization of long-term historical phenomena of broad extent was expressed in terms of the succession of four ecumenical world empires, succeeding one another as the central actors in world history: the Assyrio-Babylonian, the Median-Persian, the Alexandrian- Macedonian, and the Roman. This perspective was shared by the Book of Daniel and by ecclesiastical works, especially Syrian and Byzantine apocalypses influenced by it, albeit with minor variations, as in Orosius’ substitution of the Carthaginian world empire for the Median-Persian. Muslim caliphs considered their own ecumenical world empire to be the fifth and final order of world history, a conception shared by Muslim apocalypticism and, with many complications and nuances, by universal histories written in Arabic, all of which regarded dynastic succession as both prophetic inheritance and as the renewal of ecumenical imperial ambition, transferred from one line to another.

Analogously, medieval Christian polities, Byzantine as well as Frankish, subscribed to the same theory of translatio imperii by regarding themselves as being in a direct line of typological continuity with Rome, variously through Byzantium, the ‘New Rome,’ or the Holy Roman Empire. In both, Romanity was the worldly cement of Christianity. This was a conception developed by Eusebius for his contemporary overlord Constantine, and was to remain effective until the dawn of modern times. In all cases, the past was understood to have been completed at its inception, with subsequent polities reenacting the foundational event.

Finally, mention must be made of the disjunction between these metahistorical and transcendental realms of typological continuity, and the all-too-human chaos of particular histories. No movement or qualitative change is discernible in the context of these, only the predictable succession of wars, rapine, pestilence, and occasionally of praiseworthy acts, without connection with an order of reality that might transcend the events themselves and render sense unto them.

Two roughly contemporary events heralded a new conception of history that made the modern notion of civilization conceivable. Both were specifically European, but their conceptual consequences were globalized in the course of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The first was Humanism, particularly in Italy, which for the first time broke the spell of Roman continuity by construing the immediate past as an age of darkness, and by confining Roman grandeur to the republican and early imperial ages. Thus Petrarch’s (d. 1374) project of classicism counterposed to living tradition; Flavio Biondo’s (d. 1463) anticipation of division of history into the classical, the medieval, and the modern; and Lorenzo Valla’s (d. 1457) refutation of medieval documentary forgeries such as the Donation Constantini, based on an argument from anachronism: together, these laid the ground for a view of history as the domain of change rather than of repetition.

Needless to say, the notion of translatio imperii was no longer tenable in this context. It is at this point that Humanism converged with the other event foundational of the modern historical consciousness, namely, the Reformation. Criticism of the Church by Wycliff (d. 1384) and Luther, and the historiographic expression of this antitraditionalist fundamentalism in John Foxe’s Acts and Monuments (1563), were in crucial ways congruent in their conception of the past with Humanism. The identification of the Pope with the Antichrist, the designation of the greater part of the history of Christianity as a history of falsehood, and the devalorization of the immediate past as abiding tradition and its construal as degeneration, also led to the rejection of the notion of translatio imperii, and the substitution of notions of Reformation and renovation to that of transfer in continuity.

Thus the ground was prepared for notions of rise, decline, and fall – most notably the decline and fall of Rome and the reclamation of Roman republicanist models in a spirit of revivalism – that were finally to mature in the eighteenth century, with Gibbon and Montesquieu among others, spurred along with the development and ultimately, in the late eighteenth and during the nineteenth centuries, the institutional transformation of philology and antiquarianism into history as a topic of research detached from rhetoric. This was far beyond the late flowering of medievalizing typology with Bossuet (d. 1704), and it made the past tangible in its having been (Vergangenheit), most graphically represented in the establishment of museums during the eighteenth century in many European capital cities.

With Voltaire and other eighteenth-century figures like Volney and Chardin, another notion crucial for speaking of civilization was developed. The notion of qualitative societal and cultural difference (les moeurs) – quite apart from the dynastic and the religious – was now available in the eighteenth century, as Europe was accounting for her differences from the Ottomans, the Persians, the Chinese, and tribal peoples in the Americas.

Whereas previously the notion of historical senescence may have been used in a tragical and rhetorical sense, the new notion of decadence required the correlative notion of progress and amelioration. These notions are the very conditions of possibility for conceiving of civilization as the accomplishment of a continuous line of historical development in which origins and beginnings are transcended rather than repeated.

Word and Concept

The terms civilization and culture are intimately related in their reference, and in many instances are used almost interchangeably, according to national and linguistic conventions. Both are terms of ancient vintage, which underwent a gradual lexical expansion until, in the eighteenth century, they came to designate meanings that are recognizable in 2001.

In the course of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the meaning of the term culture expanded, in English, French, and German (as Kultur) from a medieval sense indicating the cultivation of land and of the religious cult, figuratively to denote the maintenance and cultivation of arts and letters. This figurative sense was further extended in the course of the eighteenth century to encompass the nonmaterial life of human societies in a very broad sense encompassing the refinement of manners no less than intellectual and artistic accomplishments associated with the Enlightenment – the former sense still persists in terms such as haute couture and Kulturbeutel (vanity case).

The term was used both locally and in contrast to societies adjudged still living in a state of nature, although in German the accent had been on an esthetic of the lofty and the sublime as distinct from the crassly material, in association with a correlative emphasis on cultivation, Bildung, both individual and collective. In this way, the term was opened up to impregnation by the emergent notion of progress, the progress of individual societies as of humanity in general regarded both as a process natural to human society and as a principle of normative ranking among societies.

Not dissimilarly, and in imitation of ‘culture,’ in the eighteenth century the term civilization underwent – especially in France and somewhat later in England – a figurative expansion in its lexical reference from the Latin civilis, life under reputable forms of government, to the broader designation of order, civil, and governmental. This order befitted developed societies that might regard themselves as civilized in contradistinction to other, barbarian or savage, yet-to-be-civilized societies. The contrastive connotations of ‘civilization’ were far more accentuated than those of ‘culture,’ which was more commonly used in Germany, a land then with little or no experience of the world outside Europe. ‘Culture’ also came to be used in France and more saliently in England, as in Germany, decidedly to signal social distance and social distinctions within particular countries.

In all cases, these two terms increasingly came to be associated with a developmental perspective on history: not only the linear and cumulative course traversed by historical phenomena in time but also of languages, geological layers, plant and animal species, and human societies generally (and later, races), toward greater differentiation, complexity, and accomplishment. Correlatively, the meanings conveyed by these terms were implied by other terms or by none at all, as, for example, with Rousseau and Voltaire.

The nineteenth century witnessed a complicated relationship between ‘culture’ and ‘civilization’ whose fields of connotation and denotation shade into each other in a manner that has not helped the distinctive clarity and definition of either. The crucial player here was Germany, where Kultur took a decidedly romantic-nationalist turn in the early nineteenth century, dwelling on national uniqueness and individuality, and buttressed by the emergence of Kulturwissenschaft as a discipline and by studies of folklore.

The further developments of this politicocultural impulse toward the end of the nineteenth century led not only to the profuse discourses on decadence, Entartung, (‘disnaturation’) but also to the extension to France of this particularitic understanding of culture – and of civilization – under the influence of de Joseph de Maistre and the Catholic Counter- Enlightenment. As a result of Franco-German conflicts and of the severe stresses within France, a battle was waged between the advocates of ‘culture,’ upholders of national particularism, and of ‘civilization,’ champions of Enlightenment universalism accused by their detractors of crass materialism, a battle that reached its apogee during the First World War in the polemics between Romain Rolland and Thomas Mann.

Yet ‘civilization’ itself had been increasingly more receptive to particularism and nationalism, most specifically in historical writing. Books on the civilization of France, Germany, Europe, Italy, and England, emerged from the second quarter of the nineteenth century, and in certain ways, the very currency of the term made it open to divergent uses. Toward the end of that century, the term came to be used under the influence of the German notion of Kultur, a term often rendered as ‘civilization’ in French translations of German works. One additional but decisive factor was English anthropology, with the appearance in 1871 of Edward Tylor’s Primitive Culture (1958), and the subsequent predominance of the term ‘culture’ to designate a condition, on a ladder leading from savagery to barbarism and finally to civilization, in Anglo-Saxon anthropology. With the discovery and mystique of classical Greece toward the end of the eighteenth century, of the unity of the ‘West’ from Greece, through Rome, on to the Romano-Germanic peoples in the Middle Ages, culminating in modern European civilization, was to become the locus classicus of this notion of civilization.

In the later part of the nineteenth century and throughout the twentieth century, both the terms and conceptions outlined were subsequently taken over and became crucial instruments of historical categorization in India, China, and the Arab countries and elsewhere. In Arabic, thaqafa, an equivalent to the German Bildung, came to stand for culture, normally taken to designate intellectual and artistic life in a manner strongly elitist in character, and hadara was used for civilization, taken as a more general concept indicating the entire life of society including material life.

Continuities: Relativism

Linear developmentalism had, in general, underlain the entire body of diverse discourses on civilization and of its sister concept of culture. This developmentalism bifurcated along lines that may be characterized broadly as German and French in original inspiration.

Of the two, the former had been more intimately associated with romantic national and, the latter, with civilizational particularism, producing a natural history of human groups regarded in analogy to organic species. These human groups were thus conceived of as self-subsistent, continuous over time, largely impermeable, essentially intransitive, and according to many representatives of this view, almost congenitally given to conflict and war.

Originating in conservative reactions to the Enlightenment, with a strong anti-Gallic political impulse, this theory of historical and social development was associated with figures such as Johann Gottfried Herder in Germany and Edmund Burke in England, although it did have a strong representation in France among royalist, Catholic, and other antirevolutionary (1789, 1848, 1871) currents represented by figures such as de Maistre, Gobineau, and Gustave Le Bon. The principal conceptual feature of this antimechanistic concept of history was insistence on individuality in the histories of different nations, races, and civilizations – terms often conflated in various combinations, in analogy with biological organisms, and perhaps best captured in the capacious semantic field of the German word Volk. In this sense, one may speak of continuity with pre-Enlightenment concepts of a social organism modeled upon the integrated somatic unity of the human body, as had been previously thought in medieval Arabic historicopolitical writings and in medieval European conceptions from the time of John of Salisbury (d. 1180). The fear of decline and decadence, conceived as a breakdown of a natural order, was the specific point at which continuity with medieval organismic concepts of the historicopolitical order made itself evident and conceptually formative. This was at a time when the idea of progress – and in contrast to it – had become a genuinely historical category, involving a consequential conception of change, of evolutionism, of the temporality specific to events (Verzeitlichung), and of a distanciation correct between human and natural histories.

The course of a particular history was seen to reside in a number of essential features, which Herder termed Kräfte, resulting in a history which, increasingly elevated and evolutive in the course of time as it may be, was still governed by principles that were, in essence, changeless, principles that imparted individuality upon these intransitive histories.

Whereas the Enlightenment provided, and the nineteenth century elaborated, a notion of genetic development along an axis of cumulative time to which civilizations and other historical masses are subject, the organismic, particularist notion conceived of a civilization as bound to a self-enclosure inherent in its origins. Although this did not necessarily lead to a historical cyclism, it constituted its conceptual condition of possibility, and facilitated culturalist notions of nationalism that spoke in terms of ‘revival.’

It was a cyclical notion of the history of cultural and civilizational circles, Kulturkreise, according to Ernst Troeltsch (1920) that was made conceivable by the manifold discourses on decadence, malfunction, and historical pathology, notions that implicitly involve a measure against a more consummate state of organic health and well-being implicit in the foundations of each. It was the systematic elaboration of the decadence/normalcy structure that led to great schemas of world history, divided into intransitive civilizations, of Oswald Spengler’s Untergang des Abendlandes (Spengler, 1922) and of the Spenglerian heresy represented by Arnold Toynbee’s A Study of History (Toynbee, 1934–1959).

Described by Claude Chaunu (1984 as ‘a samsara of historical forms,’ these vitalist theories of the rise and inevitable decline of civilizations constitute a naturalistic morphology of historical becoming. From this perspective, civilizations were seen as historical phenomena that are perpetually in conflict with one another, each endowed with a particular ethos or animating principle. Such were Spengler’s (1922) Magian culture (the Perso-Islamic) and Promethean culture (the European). Such were also Toynbee’s (1934–1959) Syriac and other civilizations, although with this latter author the inner definition of civilizations was less clearly predetermined, and founded on a firmer and far more scrupulous empirical foundation than with Spengler. Nevertheless, Toynbee does characterize civilizations in terms of particularistic impulses, such as the estheticism of Greek civilization, the religious spirit of the Indian, and the mechanistic ethos of the West. Each of these is an integrated pattern of daily life, on attitude toward the holy, a style of jurisprudence, a manner of government, an artistic style, and much more.

With both authors, the historical phenomena, respectively, designated as ‘cultures’ and ‘societies,’ obey an iron law of rise and decline, of glory and senescent atrophy, the terminal phases of which Spengler, in keeping with German usage of the day, derisively termed ‘civilization.’ It is noteworthy that this morphology of historical masses, be they called civilizations, cultures, or societies, that this monocausal description in terms of basic traits such as the Promethean or the esthetic, was congruent with certain developments in anthropology, particularly in American anthropology in the first half of the twentieth century (Franz Boas, Alfred Kroeber, Ruth Benedict, and Edward Sapir), which identified separate societies according to self-consistent and intransitive personality profiles that they ostensibly gave rise to. This had a decisive influence on the introduction of organismic thinking into the human sciences in general. After a long period of disrepute, the ‘culturalized’ notions of human collectivities, of self-enclosure, and of continuity have come back to center stage at the close of the twentieth century, correlatively with the politics of identity worldwide.

The organismic and vitalist notion of civilization was, and still is, extremely effective in the writing of history and in the late twentieth century has had a certain political salience in terms of Samuel Huntington’s ‘war of civilizations’ and the mirror-image riposte in terms of the ‘dialogue of civilizations.’ It denies the possibility of a general human history, which it regards, in the words of Ernst Troeltsch (1920), as being ‘violently monistic,’ and construes the task of a history of civilizations as separate histories of Europe, China, India, Islam, Byzantium, Russia, Latin, and Protestant Europe, and others, in various possible permutations and successions, as separate cultural and moral spheres that are merely contiguous in space. Correlatively, this constituted the conceptual armature of certain forms of violently particularistic history that was mirrored or endogenously paralleled, among others in India, for instance (Savarkar, 1969), or in the writings of radical Muslim ideologues.

Novelties: Universalism

The deficit in historicity evident in romantic and vitalist historism, with its emphasis on organic continuity, was to a great extent made up in the more consistently evolutionist accounts of historicism. It was this conception of history, at once evaluative, evolutive, and vectorial, which bore the burden of the universalist notion of civilization. Whereas in historism the bearers of civilization – or rather of ‘culture’ – were particular peoples or individual historical itineraries, such as the West or Islam, the whole of humanity partook of the development of civilization, which, in the historicist perspective, was universal and continuous.

Several versions of this were in evidence, of which two are of particular note due to their wide conceptual incidence and the social and political influence they exercised through worldwide social movements, both revolutionary and gradualist, inspired by the Enlightenment. According to this conception of a universal civilization, human societies pass through a uniform series of progressive developments, which result in intellectual and moral elevation. They also result in superior social, economic, and political levels of development, marked by a higher and wider order of rationality, social differentiation, and control over nature whose instrument is science.

The more consistently universalist of these versions – exemplified, among others, by Jean Marquis de Condorcet, Auguste Comte, and Herbert Spencer, and in the evolutionist anthropology of Tylor (1958) – saw the whole of humanity as being predisposed to this upward movement. Nevertheless, according to this view some peoples may still subsist in a condition that others (Europe) had already surpassed, being still captive to superstition, to a weak organization of society and the economy, and to undeveloped political institutes (despotism, as in the case of Orientals, or otherwise various forms of acephalic organization, as is the case with primitive societies). The only caveat here is that many theorists of the evolution of human societies did not see human improvement as uniform in developed societies themselves, but that developed societies were not only internally differentiated in the levels of accomplishment attained by different social groups, but also liable to fall far below the moral ideals that development makes possible. Nevertheless, much writing on the history of universal civilization, especially in countries influenced by Marxism, such as the Soviet Union or the People’s Republic of China, saw the historical itineraries they led as crucial and exemplary steps in the development of humanity at large. In this way, the histories of Russia and China come to recuperate and tap world history at large by acting as the vanguard and exemplar of its future consummation.

Correlatively, the other conception of universalism, and this is one of profound conceptual and political importance, recognized the past contributions of various civilizations – the Mesopotamian, Egyptian, and Islamic, and in some instances the Indian and the Chinese as well – to the course of human civilization, which eventually lodged itself in Europe, defined as the abode of Romano-Germanic history, or even in small parts of Europe, such as France or Prussia. This writing of universal history, much in evidence in the plethoric literature of universal histories both popular and learned, was expressed in what is perhaps its most accomplished general formulation by Georg Hegel (1956) in the nineteenth century, and by Karl Jaspers (1949) in the twentieth – the latter is little read today, but he is the one who, nevertheless, captures this notion with special clarity.

Not infrequently, this second type of universalist history is allied to an important element derived from the romantic theory of the history of civilizations treated in Section Novelties: Universalism, namely, the presumption of very long-term individual continuity. Thus the point is habitually made, with varying shades of emphasis and nuance, that universal civilization made Europe its eventual home because of some abiding characteristics possessed ab initio by ‘the West,’ such as rationality, the spirit of freedom, vigor, and dynamism. This changeless West is counterposed to an eternal East, such as Mesopotamia, Egypt, and Islam, which, their relative erstwhile merits apart, constitute, in a categorical degradation, a mere prehistory to fully developed civilization. East and West – not to speak of Islam, the name of a religion transmuted into an atopic location – are metageographical notions that do not allow, except with anachronistic violence, for projection into the antique and late antique worlds. However, this does not disturb the ideological coherence of this notion of civilization.

Beyond Totality

Writing about civilization according to the manners outlined contained both large-scale abstraction and a great deal of precise empirical historiography. Under the influence of Marxism, acknowledged as such as well as implicit, historical scholarship, and most specifically social and economic history in the traditions of Max Weber and of the Annales school, produced specifications regarding material and other aspects of civilization that allayed, to a considerable degree, the rhetorical force of thinking civilizations in terms of purely moral and ideological continuities, betokening exclusive sociohistorical groups. The notion of a Judeo-Christian civilization, as distinct from textual typology within the Bible, is an excellent illustration of this, having been born and expanded in specific circumstances following the Second World War.

In this way, civilizations for contemporary historical writing have come to comprise the total historical conditions that exist in a specific place and time: functional and organizational forms of the state; the longue durée of demographic, agricultural, economic, social, urban, ecological, climatic, and other forces underwritten by geographical structures and relations; and non-material culture, such as arts, letters, cognitive structures, and religions. The possibilities of a total history of a civilization is, it must be stressed, an expansion of a previous and more limited form of the cultural history of a particular epoch, exemplified by Jakob Burckhardt’s studies of Constantine and Renaissance Italy (Burckhardt, 1955: Vols. 1 and 3).

As a result, since about 1950 it has become possible historically to specify the material elements that constitute the history of a civilization; however, its temporal and geographical boundaries may be defined. Correlatively, it has become possible to conceive of the specific differences between histories – China and Europe for instance, as in the work of Jacques Gernet (1988) – beyond a discourse on immobility and other immanent characteristics ascribed to this history or that, and to think of specificity in proper historical terms, such as the relative weight of various elements of the rural economy, the relation between state and the economy, the impact of metallurgy, and much more.

In this context, civilizational continuities came to be reconsidered in terms of historically determinant factors of a predominantly geographical nature, not so much in the spirit of geographical determinism as described by the German school of Friedrich Ratzel (1895), but with a greater degree of temporal specification, mediated by Lucien Febvre’s (1925) consideration of historical geography and culminating in Fernand Braudel’s study of the Mediterranean (1972–73). By the same token, it has become possible squarely to face the nominalist caution required in thinking about civilizations, and to think of their constitution, specification, and collapse in terms of the concrete historical investigation of demography, economy, and society without recourse to the metaphysical rhetoric of decline (Tainter, 1988).

These specifications apart, it remains true that the construal of civilizational intransitivity, with Braudel as with others, still needs to resort to a new redaction of the rhetoric of permanence, most particularly with regard to nonmaterial culture, now underscored and almost overdetermined by considerations of relief, soil, water supply, and means of transport – all of which are undeniable factors, albeit ones that modern technology and economy, most poignantly the postmodern economy, have rendered questionable.

Nevertheless, recent historical research has made it concretely possible to tap the genial formulations made by Marcel Mauss in 1930 (Febvre et al., 1930) concerning the categorization of historical masses: of civilizations as a ‘hypersocial systems of social systems,’ as transsocietal and extranational units of historical perception and categorization. These are conceived of in opposition to specific social phenomena, and this conception of civilization valorizes the distinction between civilization, society, and culture, freeing the first of the deterministic and totalizing rhetorical glosses of metahistory, and making possible a veritable history of civilizations. Civilization may thus be considered as at once a particular instance of historical becoming, and a specific ideological redaction of the past whose relation to historical reality can be questioned and rendered historical. In this context, the historian may also be able to valorize the extremely expansive longue durée implied by such theories as Dumézil’s (1958) Indo-European trifunctionalism without recourse to organismic and totalizing figures of particularity and continuity (Le Goff, 1965). A historian may be similarly able to valorize recent studies that stress the occurrence and communicability of recurrent phenomena of the imaginary order across vast spaces, cultures, histories, and times, as instanced by Carlo Ginzburg’s study of the European witch hunts (Ginzburg, 1990). Finally, given the accent on complexity, one might be able to take the precise and nuanced study of levels and modes of socio-economic, political, institutional, ideational, and other instances of complexity – rather than criteria of simple continuity – as crucial to the delimitation of historical phenomena that one designates as ‘civilizations.’

Bibliography:

Allawi, A.A., 2009. The Crisis of Islamic Civilization. Yale University Press, New Haven, CT.

Auerbach, E., 1984. Figura. Auerbach E Scenes from the Drama of European Literature. University of Minnesota Press, MN.

Bénéton, P., 1975. Histoire des Mots: Culture et Civilisation. Fondation Nationale des Sciences Politiques, Paris.

Braudel, F., 1972–73 (S. Reynolds, Trans.). The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean World in the Age of Philip II, 2 vols. Collins, London.

Braudel, F., 1993. Grammaire des Civilisations. Flammarion, Paris.

Burckhardt, J., 1955. Renaissance Italy. Gesemmete Werke, vols. 1 and 3. Schwab, Basle, Switzerland.

Chaunu, P., 1981. Histoire et Décadence. Librairie academique Perrin, Paris.

Collingwood, R.G., 1946. The Idea of History. Clarendon Press, Oxford, UK.

Dumézil, G., 1958. L’idéologie Tripartie des Indo-Européens. Collection Latours, Bruxelles, Belgium.

Enciclopedia Einaudi, 1977–84. G. Einaudi, Torino (s.v. ‘Cultura materiale’, ‘Civilit’).

Encyclopædia Universalis, 1968. Encyclopædia Universalis France, Paris (s.v. ‘Civilization’ ‘Culture et civilization’).

Encyclopedia of Religion and Ethics, 1980. T and T Clark, Edinburgh, UK (s.v. ‘Civilisation’).

Febvre, L., 1925. A Geographical Introduction to History. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co., London.

Febvre, L., Mauss, M., Tonnelat, E., Nicophoro, A., 1930. Civilisation. Le Mot et l’Idée. Renaissance du Livre(Premire Semaine internationale de Synthèse, Fascicule 2), Paris.

Fehl, E. (Ed.), 1971. Chinese and World History. The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong.

Ferguson, N., 2011. Civilization: The West and the Rest. Penguin Press, New York. Gat, A., 2006. War in Human Civilization. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Gernet, J., 1988. A History of Chinese Civilization (J.R. Forster, Trans.). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

Ginzburg, C., 1990. Ecstasies: Deciphering the Witches’ Sabbath. Hutchinson, London.

Hegel, G.W.F., 1956. Philosophy of History (G. Sibree, Trans.). Dover, New York.

Herder, J.G.von, 1968. Reflections on the Philosophy of History of Mankind (Abridged by F. Manuel). University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London.

Herder, J.G.von, 1969. J.G. Herder on Social and Political Culture (F.M. Barnard, Ed. and Trans.). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

Jaspers, K., 1949. Vom Ursprung und Ziel der Geschichte. Artemis Verlag, Zrich, Switzerland.

Kemp, A., 1991. The Estrangement of the Past. A Study in the Origin of Modern Historical Consciousness. Oxford University Press, Oxford and New York.

Khaldun, Ibn, 1958. The Muqaddimah: An Introduction to History (F. Rosenthal, Trans.). Pantheon Books, New York.

Kosellek, R., Widmer, P. (Eds.), 1980. Niedergang. Studien zu einem geschichtlichen Thema. Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart, Germany.

Kroeber, A.L., 1963. An Anthropologist Looks at History. University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles.

Kroeber, A.L., Kluckhohn, C., 1952. Culture: A Critical Review of Concepts and Definitions. The Peabody Museum, Cambridge, MA.

Le Goff, J., 1965. La Civilisation au l’occident médieval. Arthaud, Paris.

Lewis, M.W., Wigen, K.E., 1997. The Myth of Continents. A Critique of Metageography. University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles.

Marrou, H.I., December 1938. Culture, civilization, décadence. Revue de Synthèse 133.

Nasr, S.H., 2003. Islam: Religion, History, and Civilization. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco.

Ratzel, F., 1895. Anthropogeographische Beitrage. Duncker und Humblot, Leipzig, Germany.

Rsen, J., Gottlob, M., Mittag, A. (Eds.), 1998. Die Vielfalt der Kulturen. Erinnerung, Geschichte, Identität, 4. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main, Germany.

Savarkar, V.D., 1969. Hindutva: Who Is a Hindu?, fifth ed. Veer Savarkar Parakashan, Bombay, India.

Schlanger, J.E., 1971. Les Métaphores de l’Organisme. Vrin, Paris.

Searle, J.R., 2010. Making the Social World: The Structure of Human Civilization. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Solomon, S., 2010. Water: The Epic Struggle for Wealth, Power, and Civilization. Harper, New York.

Spengler, O., 1922. Der Untergang des Abendlandes, 2 vols. W. Braumller, Vienna and Leipzig.

Tainter, J.A. (Ed.), 1988. The Collapse of Complex Societies. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

Toynbee, A., 1934–1959. A Study of History, 12 vols. Oxford University Press, London.

Troeltsch, E., 1920. Der Aufbau der europäischen Kulturgeschichte. Schmollers Jahrbuch für Gesetzgebung, Verwaltung, und Volkswirtschaft im Deutschen Reiche 44 (3), 1–48.

Tylor, E.B., 1958. Primitive Culture, 2 vols. Harper, New York.

Wells, S., 2010. Pandora’s Seed: The Unforseen Cost of Civilization. Random House, New York.

Zureiq, K., 1969. Nahnu Wa’t-tarikh. Dar al- Ilm lil-Malayin, Beirut, Lebanon.

See also:

History Research Paper Topics

History Research Paper

World History Research Paper

0 notes

Text

Events 2.2

506 – Alaric II, eighth king of the Visigoths, promulgates the Breviary of Alaric (Breviarium Alaricianum or Lex Romana Visigothorum), a collection of "Roman law".

880 – Battle of Lüneburg Heath: King Louis III of France is defeated by the Norse Great Heathen Army at Lüneburg Heath in Saxony.

962 – Translatio imperii: Pope John XII crowns Otto I, Holy Roman Emperor, the first Holy Roman Emperor in nearly 40 years.

1032 – Conrad II, Holy Roman Emperor becomes king of Burgundy.

1141 – The Battle of Lincoln, at which Stephen, King of England is defeated and captured by the allies of Empress Matilda.

1207 – Terra Mariana, eventually comprising present-day Latvia and Estonia, is established.

1438 – Nine leaders of the Transylvanian peasant revolt are executed at Torda.

1461 – Wars of the Roses: The Battle of Mortimer's Cross results in the death of Owen Tudor.

1536 – Spaniard Pedro de Mendoza founds Buenos Aires, Argentina.

1645 – Scotland in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms: Battle of Inverlochy.

1653 – New Amsterdam (later renamed The City of New York) is incorporated.

1709 – Alexander Selkirk is rescued after being shipwrecked on a desert island, inspiring Daniel Defoe's adventure book Robinson Crusoe.

1814 – The last of the River Thames frost fairs comes to an end.

1848 – Mexican–American War: The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo is signed.

1850 – Brigham Young declares war on Timpanogos in the Battle at Fort Utah.

1868 – Pro-Imperial forces capture Osaka Castle from the Tokugawa shogunate and burn it to the ground.

1870 – The Seven Brothers (Seitsemän veljestä), a novel by Finnish author Aleksis Kivi, is published first time in several thin booklets.

1876 – The National League of Professional Baseball Clubs of Major League Baseball is formed.

1881 – The sentences of the trial of the warlocks of Chiloé are imparted.

1887 – In Punxsutawney, Pennsylvania, the first Groundhog Day is observed.

1899 – The Australian Premiers' Conference held in Melbourne decides to locate Australia's capital city, Canberra, between Sydney and Melbourne.

1900 – Boston, Detroit, Milwaukee, Baltimore, Chicago and St. Louis, agree to form baseball's American League.

1901 – Funeral of Queen Victoria.

1909 – The Paris Film Congress opens, an attempt by European producers to form an equivalent to the MPCC cartel in the United States.

1913 – Grand Central Terminal opens in New York City.

1920 – The Tartu Peace Treaty is signed between Estonia and Russia.

1922 – Ulysses by James Joyce is published.

1922 – The uprising called the "pork mutiny" starts in the region between Kuolajärvi and Savukoski in Finland.

1925 – Serum run to Nome: Dog sleds reach Nome, Alaska with diphtheria serum, inspiring the Iditarod race.

1934 – The Export-Import Bank of the United States is incorporated.

1935 – Leonarde Keeler administers polygraph tests to two murder suspects, the first time polygraph evidence was admitted in U.S. courts.

1942 – The Osvald Group is responsible for the first, active event of anti-Nazi resistance in Norway, to protest the inauguration of Vidkun Quisling.

1943 – World War II: The Battle of Stalingrad comes to an end when Soviet troops accept the surrender of the last organized German troops in the city.

1954 – the Detroit Red Wings played in the first outdoor hockey game by any NHL team in an exhibition against the Marquette Branch Prison Pirates in Marquette, Michigan.

1959 – Nine experienced ski hikers in the northern Ural Mountains in the Soviet Union die under mysterious circumstances.

1966 – Pakistan suggests a six-point agenda with Kashmir after the Indo-Pakistani War of 1965.

1971 – Idi Amin replaces President Milton Obote as leader of Uganda.

1971 – The international Ramsar Convention for the conservation and sustainable utilization of wetlands is signed in Ramsar, Mazandaran, Iran.

1980 – Reports surface that the FBI is targeting allegedly corrupt Congressmen in the Abscam operation.

1982 – Hama massacre: The government of Syria attacks the town of Hama.

1987 – After the 1986 People Power Revolution, the Philippines enacts a new constitution.

1989 – Soviet–Afghan War: The last Soviet armoured column leaves Kabul.

1990 – Apartheid: F. W. de Klerk announces the unbanning of the African National Congress and promises to release Nelson Mandela.

1998 – Cebu Pacific Flight 387 crashes into Mount Sumagaya in the Philippines, killing all 104 people on board.

2000 – First digital cinema projection in Europe (Paris) realized by Philippe Binant with the DLP CINEMA technology developed by Texas Instruments.

2004 – Swiss tennis player Roger Federer becomes the No. 1 ranked men's singles player, a position he will hold for a record 237 weeks.

2005 – The Government of Canada introduces the Civil Marriage Act. This legislation would become law on July 20, 2005, legalizing same-sex marriage.

2007 – Police officer Filippo Raciti is killed when a clash breaks out in the Sicily derby between Catania and Palermo, in the Serie A, the top flight of Italian football. This event led to major changes in stadium regulations in Italy.

2012 – The ferry MV Rabaul Queen sinks off the coast of Papua New Guinea near the Finschhafen District, with an estimated 146–165 dead.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Events 2.2

506 – Alaric II, eighth king of the Visigoths, promulgates the Breviary of Alaric (Breviarium Alaricianum or Lex Romana Visigothorum), a collection of "Roman law".

880 – Battle of Lüneburg Heath: King Louis III of France is defeated by the Norse Great Heathen Army at Lüneburg Heath in Saxony.

962 – Translatio imperii: Pope John XII crowns Otto I, Holy Roman Emperor, the first Holy Roman Emperor in nearly 40 years.

1032 – Conrad II, Holy Roman Emperor becomes king of Burgundy.

1141 – The Battle of Lincoln, at which Stephen, King of England is defeated and captured by the allies of Empress Matilda.

1207 – Terra Mariana, eventually comprising present-day Latvia and Estonia, is established.

1438 – Nine leaders of the Transylvanian peasant revolt are executed at Torda.

1461 – Wars of the Roses: The Battle of Mortimer's Cross results in the death of Owen Tudor.

1536 – Spaniard Pedro de Mendoza founds Buenos Aires, Argentina.

1645 – Scotland in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms: Battle of Inverlochy.

1653 – New Amsterdam (later renamed The City of New York) is incorporated.

1709 – Alexander Selkirk is rescued after being shipwrecked on a desert island, inspiring Daniel Defoe's adventure book Robinson Crusoe.

1814 – The last of the River Thames frost fairs comes to an end.

1848 – Mexican–American War: The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo is signed.

1850 – Brigham Young declares war on Timpanogos in the Battle at Fort Utah.

1868 – Pro-Imperial forces capture Osaka Castle from the Tokugawa shogunate and burn it to the ground.

1870 – The Seven Brothers (Seitsemän veljestä), a novel by Finnish author Aleksis Kivi, is published first time in several thin booklets.

1876 – The National League of Professional Baseball Clubs of Major League Baseball is formed.

1887 – In Punxsutawney, Pennsylvania, the first Groundhog Day is observed.

1899 – The Australian Premiers' Conference held in Melbourne decides to locate Australia's capital city, Canberra, between Sydney and Melbourne.

1900 – Six cities, Boston, Detroit, Milwaukee, Baltimore, Chicago and St. Louis, agree to form baseball's American League.

1901 – Funeral of Queen Victoria.

1909 – The Paris Film Congress opens, an attempt by European producers to form an equivalent to the MPCC cartel in the United States.

1913 – Grand Central Terminal opens in New York City.

1920 – The Tartu Peace Treaty is signed between Estonia and Russia.

1922 – Ulysses by James Joyce is published.

1925 – Serum run to Nome: Dog sleds reach Nome, Alaska with diphtheria serum, inspiring the Iditarod race.

1934 – The Export-Import Bank of the United States is incorporated.

1935 – Leonarde Keeler administers polygraph tests to two murder suspects, the first time polygraph evidence was admitted in U.S. courts.

1942 – The Osvald Group is responsible for the first, active event of anti-Nazi resistance in Norway, to protest the inauguration of Vidkun Quisling.

1943 – World War II: The Battle of Stalingrad comes to an end when Soviet troops accept the surrender of the last organized German troops in the city.

1959 – Nine experienced ski hikers in the northern Ural Mountains in the Soviet Union die under mysterious circumstances.

1966 – Pakistan suggests a six-point agenda with Kashmir after the Indo-Pakistani War of 1965.

1971 – Idi Amin replaces President Milton Obote as leader of Uganda.

1971 – The international Ramsar Convention for the conservation and sustainable utilization of wetlands is signed in Ramsar, Mazandaran, Iran.

1980 – Reports surface that the FBxI is targeting allegedly corrupt Congressmen in the Abscam operation.

1982 – Hama massacre: The government of Syria attacks the town of Hama.

1987 – After the 1986 People Power Revolution, the Philippines enacts a new constitution.

1989 – Soviet–Afghan War: The last Soviet armoured column leaves Kabul.

1990 – Apartheid: F. W. de Klerk announces the unbanning of the African National Congress and promises to release Nelson Mandela.

1998 – Cebu Pacific Flight 387 crashes into to Mount Sumagaya in the Philippines, killing all 104 people on board.

2000 – First digital cinema projection in Europe (Paris) realized by Philippe Binant with the DLP CINEMA technology developed by Texas Instruments.

2004 – Swiss tennis player Roger Federer becomes the No. 1 ranked men's singles player, a position he will hold for a record 237 weeks.

2005 – The Government of Canada introduces the Civil Marriage Act. This legislation would become law on July 20, 2005, legalizing same-sex marriage.

2007 – Police officer Filippo Raciti is killed when a clash breaks out in the Sicily derby between Catania and Palermo, in the Serie A, the top flight of Italian football. This event led to major changes in stadium regulations in Italy.

2012 – The ferry MV Rabaul Queen sinks off the coast of Papua New Guinea near the Finschhafen District, with an estimated 146–165 dead.

0 notes

Text

Events 2.2

506 – Alaric II, eighth king of the Visigoths, promulgates the Breviary of Alaric (Breviarium Alaricianum or Lex Romana Visigothorum), a collection of "Roman law".

880 – Battle of Lüneburg Heath: King Louis III of France is defeated by the Norse Great Heathen Army at Lüneburg Heath in Saxony.

962 – Translatio imperii: Pope John XII crowns Otto I, Holy Roman Emperor, the first Holy Roman Emperor in nearly 40 years.

1032 – Conrad II, Holy Roman Emperor becomes king of Burgundy.

1141 – The Battle of Lincoln, at which Stephen, King of England is defeated and captured by the allies of Empress Matilda.

1207 – Terra Mariana, eventually comprising present-day Latvia and Estonia, is established.

1438 – Nine leaders of the Transylvanian peasant revolt are executed at Torda.

1461 – Wars of the Roses: The Battle of Mortimer's Cross results in the death of Owen Tudor.

1536 – Spaniard Pedro de Mendoza founds Buenos Aires, Argentina.

1645 – Scotland in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms: Battle of Inverlochy.

1653 – New Amsterdam (later renamed The City of New York) is incorporated.

1709 – Alexander Selkirk is rescued after being shipwrecked on a desert island, inspiring Daniel Defoe's adventure book Robinson Crusoe.