#this line from darwish’s poem just made me think about

Text

what resembles the grave but isn’t, anne boyer // i didn’t apologize to the well, mahmoud darwish (trans. fady joudah).

#words#anne boyer#mahmoud darwish#comparatives#*#w*#this line from darwish’s poem just made me think about#boyer’s iconic grave-defying poem

13K notes

·

View notes

Note

i've been collecting little things that remind me of n, and this one caught my eye because it made me think of suri and nate 🦋

"I used to dream of drinking tea with you at night, I mean, to be partners in happiness and in joy. Believe me, my dear, it warms my heart, even if you are far away. Not because I love you less, because I love you more."

(from a letter the palestinian poet mahmoud darwish wrote to his lover tamar ben-ami)

Hello, lovely friend! I have to say that my heart is completely full and I am just melting and hearts around my head about how beautiful all of this is.

I would love to know more about the other little things that remind you of N! This morning, I was at an arboretum that’s in the middle of their tulip bloom. Secluded, tucked away part of the state and it was just so breathtaking and gorgeous to in the middle of the flowers! Have you seen a tulip open in the sunlight? Nothing like it. Naturally, I thought of N while taking it all in.

This poem is so beautiful, so intimate, and it really does make me think of Nate and Suri, as well! Suri doesn’t read as much but she loves to peruse through books of poetry (mainly love poems). It’s a headcanon of mine that she finds a poem, writes it down in a note, and sneaks it to Nate. Or that she’ll recite it to him (the lines she can remember!) when they’re having a gentle, quiet moment.

And this poem in particular? Is just so meaningful. Mahmoud Darwish. The connection between them in language and in the type of domestic and romantic love and from an Arab poet. Is just making me so emotional in the very best sort of way!

Not because I love you less, but because I love you more

Thank you for this wonderful ask! For thinking of me and my sweet little detective! Hope you’re having a wonderful day!

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fake Hafez: How a supreme Persian poet of love was erased | Religion | Al Jazeera

This is the time of the year where every day I get a handful of requests to track down the original, authentic versions of some famed Muslim poet, usually Hafez or Rumi. The requests start off the same way: "I am getting married next month, and my fiance and I wanted to celebrate our Muslim background, and we have always loved this poem by Hafez. Could you send us the original?" Or, "My daughter is graduating this month, and I know she loves this quote from Hafez. Can you send me the original so I can recite it to her at the ceremony we are holding for her?"

It is heartbreaking to have to write back time after time and say the words that bring disappointment: The poems that they have come to love so much and that are ubiquitous on the internet are forgeries. Fake. Made up. No relationship to the original poetry of the beloved and popular Hafez of Shiraz.

How did this come to be? How can it be that about 99.9 percent of the quotes and poems attributed to one the most popular and influential of all the Persian poets and Muslim sages ever, one who is seen as a member of the pantheon of "universal" spirituality on the internet are ... fake? It turns out that it is a fascinating story of Western exotification and appropriation of Muslim spirituality.

Let us take a look at some of these quotes attributed to Hafez:

Even after all this time,

the sun never says to the earth,

'you owe me.'

Look what happens with a love like that!

It lights up the whole sky.

You like that one from Hafez? Too bad. Fake Hafez.

Your heart and my heart

Are very very old friends.

Like that one from Hafez too? Also Fake Hafez.

Fear is the cheapest room in the house.

I would like to see you living in better conditions.

Beautiful. Again, not Hafez.

And the next one you were going to ask about? Also fake. So where do all these fake Hafez quotes come from?

An American poet, named Daniel Ladinsky, has been publishing books under the name of the famed Persian poet Hafez for more than 20 years. These books have become bestsellers. You are likely to find them on the shelves of your local bookstore under the "Sufism" section, alongside books of Rumi, Khalil Gibran, Idries Shah, etc.

It hurts me to say this, because I know so many people love these "Hafez" translations. They are beautiful poetry in English, and do contain some profound wisdom. Yet if you love a tradition, you have to speak the truth: Ladinsky's translations have no earthly connection to what the historical Hafez of Shiraz, the 14th-century Persian sage, ever said.

He is making it up. Ladinsky himself admitted that they are not "translations", or "accurate", and in fact denied having any knowledge of Persian in his 1996 best-selling book, I Heard God Laughing. Ladinsky has another bestseller, The Subject Tonight Is Love.

Persians take poetry seriously. For many, it is their singular contribution to world civilisation: What the Greeks are to philosophy, Persians are to poetry. And in the great pantheon of Persian poetry where Hafez, Rumi, Saadi, 'Attar, Nezami, and Ferdowsi might be the immortals, there is perhaps none whose mastery of the Persian language is as refined as that of Hafez.

In the introduction to a recent book on Hafez, I said that Rumi (whose poetic output is in the tens of thousands) comes at you like you an ocean, pulling you in until you surrender to his mystical wave and are washed back to the ocean. Hafez, on the other hand, is like a luminous diamond, with each facet being a perfect cut. You cannot add or take away a word from his sonnets. So, pray tell, how is someone who admits that they do not know the language going to be translating the language?

Ladinsky is not translating from the Persian original of Hafez. And unlike some "versioners" (Coleman Barks is by far the most gifted here) who translate Rumi by taking the Victorian literal translations and rendering them into American free verse, Ladinsky's relationship with the text of Hafez's poetry is nonexistent. Ladinsky claims that Hafez appeared to him in a dream and handed him the English "translations" he is publishing:

"About six months into this work I had an astounding dream in which I saw Hafiz as an Infinite Fountaining Sun (I saw him as God), who sang hundreds of lines of his poetry to me in English, asking me to give that message to 'my artists and seekers'."

It is not my place to argue with people and their dreams, but I am fairly certain that this is not how translation works. A great scholar of Persian and Urdu literature, Christopher Shackle, describes Ladinsky's output as "not so much a paraphrase as a parody of the wondrously wrought style of the greatest master of Persian art-poetry." Another critic, Murat Nemet-Nejat, described Ladinsky's poems as what they are: original poems of Ladinsky masquerading as a "translation."

I want to give credit where credit is due: I do like Ladinsky's poetry. And they do contain mystical insights. Some of the statements that Ladinsky attributes to Hafez are, in fact, mystical truths that we hear from many different mystics. And he is indeed a gifted poet. See this line, for example:

I wish I could show you

when you are lonely or in darkness

the astonishing light of your own being.

That is good stuff. Powerful. And many mystics, including the 20th-century Sufi master Pir Vilayat, would cast his powerful glance at his students, stating that he would long for them to be able to see themselves and their own worth as he sees them. So yes, Ladinsky's poetry is mystical. And it is great poetry. So good that it is listed on Good Reads as the wisdom of "Hafez of Shiraz." The problem is, Hafez of Shiraz said nothing like that. Daniel Ladinsky of St Louis did.

The poems are indeed beautiful. They are just not ... Hafez. They are ... Hafez-ish? Hafez-esque? So many of us wish that Ladinsky had just published his work under his own name, rather than appropriating Hafez's.

Ladinsky's "translations" have been passed on by Oprah, the BBC, and others. Government officials have used them on occasions where they have wanted to include Persian speakers and Iranians. It is now part of the spiritual wisdom of the East shared in Western circles. Which is great for Ladinsky, but we are missing the chance to hear from the actual, real Hafez. And that is a shame.

So, who was the real Hafez (1315-1390)?

He was a Muslim, Persian-speaking sage whose collection of love poetry rivals only Mawlana Rumi in terms of its popularity and influence. Hafez's given name was Muhammad, and he was called Shams al-Din (The Sun of Religion). Hafez was his honorific because he had memorised the whole of the Quran. His poetry collection, the Divan, was referred to as Lesan al-Ghayb (the Tongue of the Unseen Realms).

A great scholar of Islam, the late Shahab Ahmed, referred to Hafez's Divan as: "the most widely-copied, widely-circulated, widely-read, widely-memorized, widely-recited, widely-invoked, and widely-proverbialized book of poetry in Islamic history." Even accounting for a slight debate, that gives some indication of his immense following. Hafez's poetry is considered the very epitome of Persian in the Ghazal tradition.

Hafez's worldview is inseparable from the world of Medieval Islam, the genre of Persian love poetry, and more. And yet he is deliciously impossible to pin down. He is a mystic, though he pokes fun at ostentatious mystics. His own name is "he who has committed the Quran to heart", yet he loathes religious hypocrisy. He shows his own piety while his poetry is filled with references to intoxication and wine that may be literal or may be symbolic.

The most sublime part of Hafez's poetry is its ambiguity. It is like a Rorschach psychological test in poetry. The mystics see it as a sign of their own yearning, and so do the wine-drinkers, and the anti-religious types. It is perhaps a futile exercise to impose one definitive meaning on Hafez. It would rob him of what makes him ... Hafez.

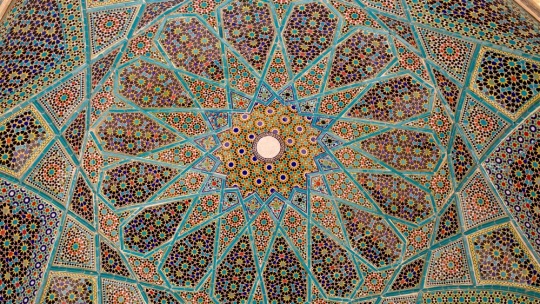

The tomb of Hafez in Shiraz, a magnificent city in Iran, is a popular pilgrimage site and the honeymoon destination of choice for many Iranian newlyweds. His poetry, alongside that of Rumi and Saadi, are main staples of vocalists in Iran to this day, including beautiful covers by leading maestros like Shahram Nazeri and Mohammadreza Shajarian.

Like many other Persian poets and mystics, the influence of Hafez extended far beyond contemporary Iran and can be felt wherever Persianate culture was a presence, including India and Pakistan, Central Asia, Afghanistan, and the Ottoman realms. Persian was the literary language par excellence from Bengal to Bosnia for almost a millennium, a reality that sadly has been buried under more recent nationalistic and linguistic barrages.

Part of what is going on here is what we also see, to a lesser extent, with Rumi: the voice and genius of the Persian speaking, Muslim, mystical, sensual sage of Shiraz are usurped and erased, and taken over by a white American with no connection to Hafez's Islam or Persian tradition. This is erasure and spiritual colonialism. Which is a shame, because Hafez's poetry deserves to be read worldwide alongside Shakespeare and Toni Morrison, Tagore and Whitman, Pablo Neruda and the real Rumi, Tao Te Ching and the Gita, Mahmoud Darwish, and the like.

In a 2013 interview, Ladinsky said of his poems published under the name of Hafez: "Is it Hafez or Danny? I don't know. Does it really matter?" I think it matters a great deal. There are larger issues of language, community, and power involved here.

It is not simply a matter of a translation dispute, nor of alternate models of translations. This is a matter of power, privilege and erasure. There is limited shelf space in any bookstore. Will we see the real Rumi, the real Hafez, or something appropriating their name? How did publishers publish books under the name of Hafez without having someone, anyone, with a modicum of familiarity check these purported translations against the original to see if there is a relationship? Was there anyone in the room when these decisions were made who was connected in a meaningful way to the communities who have lived through Hafez for centuries?

Hafez's poetry has not been sitting idly on a shelf gathering dust. It has been, and continues to be, the lifeline of the poetic and religious imagination of tens of millions of human beings. Hafez has something to say, and to sing, to the whole world, but bypassing these tens of millions who have kept Hafez in their heart as Hafez kept the Quran in his heart is tantamount to erasure and appropriation.

We live in an age where the president of the United States ran on an Islamophobic campaign of "Islam hates us" and establishing a cruel Muslim ban immediately upon taking office. As Edward Said and other theorists have reminded us, the world of culture is inseparable from the world of politics. So there is something sinister about keeping Muslims out of our borders while stealing their crown jewels and appropriating them not by translating them but simply as decor for poetry that bears no relationship to the original. Without equating the two, the dynamic here is reminiscent of white America's endless fascination with Black culture and music while continuing to perpetuate systems and institutions that leave Black folk unable to breathe.

There is one last element: It is indeed an act of violence to take the Islam out of Rumi and Hafez, as Ladinsky has done. It is another thing to take Rumi and Hafez out of Islam. That is a separate matter, and a mandate for Muslims to reimagine a faith that is steeped in the world of poetry, nuance, mercy, love, spirit, and beauty. Far from merely being content to criticise those who appropriate Muslim sages and erase Muslims' own presence in their legacy, it is also up to us to reimagine Islam where figures like Rumi and Hafez are central voices. This has been part of what many of feel called to, and are pursuing through initiatives like Illuminated Courses.

Oh, and one last thing: It is Haaaaafez, not Hafeeeeez. Please.

The views expressed in this article are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera's editorial stance.

This content was originally published here.

241 notes

·

View notes

Text

Richard Wehrenberg

Richard Wehrenberg was born in Akron, Ohio and is the author of Abracadabrachrysanthemum (2018), Hands (2015), and River (2014), co-written with Ross Gay. Their work has been published in The Academy of American Poets, Peach Mag, Bad Nudes, Monster House Press, & elsewhere. They are a poet, writer, artist, & designer living in Bloomington, Indiana.

I want to start with the cover. I admire its minimalism but also the way that minimalism allows the title to speak for itself, carrying the reader along as they go to the next page. What are some of your favorite book designs? How has your own design aesthetics changed since you first started designing chapbooks and websites over ten years ago? Do you have any sort of codified process for your design work?

I perceive Text as Image and Image as Text, in a kind of infinite stirring/reworking. My aesthetic/process for design feels necessarily influenced by how my specific body-form perceives/reads the world, via its various miracles and supposed ‘deficiencies’—ie. having one barely-able-to-see (left) eye and one incredibly-over-achieving (right) eye, as well as having benign hand tremors (ie. my hands shake, inexplicably).

I understand designing as the praxis of ‘de-signing' (ie. removing the signs from) this Earth/traditions/meanings/images. To quote one of my fav poets, Mahmoud Darwish—“I love your love / freed from itself and its signs,” which to me means: I love you ‘best’ when we shed the layers/masks/images that bury us in stories, when we dwell in our original and base-form—which of course has to be, for me—Love—the desire to see the world as un-riven, as One, despite everything working against the infinite forms love embodies. I feel my design aesthetic as ‘spiritual,’ or at least to me it feels like it springs enigmatically from a spiritual impulse/condition/base. All to say—my style/praxis is mysterious, even to myself, and my design depends on this kind of unknowability/improvisation.

For Abracadabrachrysanthemum (and Three Crises by Bella Bravo, which share almost identical design elements), I viewed the circle on the covers to be a kind of gravitational wormhole into the book’s work, like you implied. A simple entranceway that has, like a planet or black hole, its own gravity to pull/cull others in, to merge and connect worlds.

As far as design influences—I love love love Quemadura’s work (who you probably know as Wave Books’ designer.) I remember seeing their stark, simple, text-based covers as a younger poet/designer and being moved by space they allow for the text (exterior and interior) to become its own image/meaning apart from other visual suggestions. Also, Mary Austin Speaker’s work—who does design for Milkweed Editions—is always so precise, gorgeous, and enchanting. Outside of the poem-world, I am constantly inspired by fellow Bloomington designers/friends Aaron Denton and Sharnayla. The beauty they channel is astounding.

Since I began designing, I feel that I’ve just become better and faster at designing, and my core aesthetic has mostly stayed the same. Being self-taught, you kind of just pick up little preferences, skills, and potentialities randomly along the path of work. I’m in a constant state of knowledge-acquisition re design and thus my process is really just experimentation. One codified process I do have is to meditate on a book’s content, to summon its image by intentionally dwelling on it within an unconscious states of meditation, dream, trance, etc. Usually I can call up a color palette, or image/font/et al that each individual book/design is calling for via these means. I believe in this kind of prayer/listening in my work, and I cite the unconscious as my main source of artistic capacity and production. I’ve also dreamed book covers before. That’s the best.

Many of the poems in this collection have geographic allusion, descriptive precision, and a general sense of place becoming character. This reminds me in many ways of your book RIVER, co-authored with Ross Gay. While that was prose and this is poetry, this is something I have noticed in your writing. How would you describe your aesthetic connection to geography? nature? environment? This book seems to expand beyond America in ways previous writing of yours doesn’t...

I can’t not attempt to constantly locate my Self in this World—can’t not see/feel/attempt to understand where/how/who/why I am in relation to ‘others’—to the land, rivers, oceans, to other animals, to the incredible manifold instantiations of plants, to the water with which without we would vanish, to all the ostensibly separate “I’s” on this shared Earth/consciousness/World surviving, dwelling, praying, creating—Being. I am an empath and embed/imbibe my surroundings almost automatically/unconsciously into myself. I become wherever I am. And thus its violences and gorgeousnesses alike become my own. And thus I speak for them, to them, of them, with them, in service and toward the healing of them/us/I/we. I unbecome my self to reset my churning and lumbering around this planet, to geographize ‘my’ position within this unpositioned House we find our selves.

I am also quite of the mind that we are indeed both Here and Not Here. This Not Here is completely devoid of the drama of the body/ego, which we so often encounter and identify with today (and have since arriving on Earth.) My body, it’s specific forms and desires, languages and impulses, with yours, in conflict with theirs, with the scarcity, the low amount, the abundance, the never-ending forsaken nothing-everything, all of it, all the time, ever, ever, never-enough or always-too-much, the never-quite-right. You compared to me, thine in yours with mine of we. In spirit realm, there is no time and ID like we think here. Both Here and Not Here are real/valid places—the corporeal realm and the spirit realm—and I know, at least for now, I live in both places.

I realized recently one of my main hopes for my writing is for it to re-embed the divine into the every day, re-pair it with the quotidian—to reunite these worlds-torn.

What I mean is: I identify heavily with wherever I am in this 3D reality called life, and also identify heavily with the spirit realm as an (un)geographic place where I also reside. Over-identification with either realm leads to misery/suffering or disassociation/location, to paraphrase A Course In Miracles.

There is a sense of unity between the voice of these poems and everything else in the world, seen best, in my opinion, in “Signifying Brown Bear” wherein a stuffed animal becomes a virtual tunnel into all sorts of real human and existential experiences. Do you think something fundamental has changed in contemporary consumer society from ancient or medieval or even early modern societies, in which we have too many outlets for our emotions and experiences? Maybe too many is good (whatever "good" means)? In this poem, the stuffed bear almost represents your own yearning to connect as fully as you already are with universe around you. It has many of the conceits of a love poem and, at times, a tongue-in-cheek tone. In the end, the poem is what makes us think. You have turned a mirror on the reader. Was this your intention? How do you decide when to write in second-person versus first person etc.? Is any of this interpretation at all on point?

In “Signifying Brown Bear,” I am referring to an actual brown bear (ie. Ursus arctos) and the poem is just kind of about how people/entities who I become close with can begin to feel like sweet-tender-almost-cryptozoological-creatures to me and I want to also just be a sweet-tender-almost-cryptozoological-creature—or hell, I’ll settle for even a plant or a rock—back to them. Anything but this warbling, incomplete, stammering-maunderer of a human being! (Exaggeration.) I do not want my humanity at times—my human-being-ing—which has been categorized, documented, and shrink-wrapped for societal use and relation, who is part of the decimation of Earth via capital. I want the freedom (and I’m sure we could say unfreedom) of the brown bear who is in relation to the Sycamore by the river, and the salmon floating above the stones, the water gliding over, ever-thinning rock into sand granules—slowly—and back again—and back. I don’t want to be (and can’t be, is perhaps my thesis) relegated to the realm of signifiers and signs imposed via any of the manifold categorization machines we navigate on the daily to obfuscate these kind of otherworldly, ancient connections I feel as Real.

To decimate that last paragraph—I also believe in becoming fully-embodied/present in the form we are in in this life, too. So, it’s confusing, this ever-always-transforming-ing perceptioning. The confusion about what energy/thing I am and what you are is a little about what that poem is about, too.

I was reading Agamben’s The Use of Bodies and came across this ancient Greek word, poiesis, which appears in the poem and means, “the activity in which a person brings something into being that did not exist before.” I love that idea, and think it is what we are here to do, in part. So often for me the unprecedented-something we are trying to bring into existence is ourselves and the art/energy we carry in us must be made into song.

I want to always make the reader aware of their presence in my writing—to me writing is a collective act and readers are always existent, even if they never ‘read’ your work. The imagined, the dead, the unborn, the spiritually uncanonized, the already-gone-never-was reader, writer, seeker, be-er. I switch between tense often and freely, because in poetry, at least for me, we feel/fall into each word/line we write and there’s less of a need to be ‘coherent’ in the sense of the popular notion of storytelling/fiction, which (I might have another thesis here) feels like a symptom of capitalism, too. Of course it feels really nice to have a coherent story. I love television and pop culture. I want to write for television. I want to be perceived as coherent. But I want to say too: the ‘incoherence’ of poetry is a kind of coherence, a prayer toward a ‘new’ form, if you will, despite being so old itself. Poetry coheres to a perhaps more experimental way of telling a story, a precedentless next-ing, and this variation is vital—these unforeseen forms, stories, ways of being. We are a species that evolves, and because the mouth/mind is the site of evolution now, I am playing accordingly.

What ended up happening with MHP? Why did you decide to stop active involvement in it? What are you doing now in terms of day-to-day life?

Monster House Press has evolved through many forms. In 2010, it began, semi-naively, as a collective publisher of zines and chapbooks in the eponymous punk house. It then expanded and evolved into a project I was maintaining, mostly on my own, from 2012-2016 in Bloomington, Indiana. In the summer of 2016, MHP rose again as a officially collective project—an amorphous mass, as we liked to call it—primarily because the workload had become unsustainable for me to do on my own, and we were doing more and more, gaining recognition, et cetera.

We decided to lay MHP to rest at the end of the 2018, as many of us involved in keeping it going are moving onto graduate school and/or starting new projects/lives. It felt apt to end this specific instantiation in my career-form of publishing, as I have moved away from the punk/DIY scene from which it was born, and the name itself has too become divorced from its origin and who I/we was/were then.

I’m sure I’ll always be editing, publishing, reading, designing and helping steward others’ work in this world, as that impulse is something part and parcel of my being, this collaboration; however, the terms and boundaries within this specific modality as MHP have expired to me.

In my day-to-day life, I am a freelance graphic designer, artist, editor, and writer. I usually sit at my house with my dog, working on whatever project I have in my docket at the time, or go out to a coffee or tea house to do work. I also just finished auditing a graduate poetry workshop called Joy & Collaboration with Ross Gay, which was, in a word, divine—and I currently spend my days/time helping out with the growing at a communal greenhouse as well as generally just reading/writing/watching/listening to the Earth/Universe, hoping to be of service, use, and care.

What future projects are you working on? Do you still play music with organized groups? Have you thought of writing long-form fiction?

I’m hoping to start my MFA in Poetry next year.

As far as writing projects—I’m writing a collection of sonnets about my alcoholism/being an alcoholic in the United States. (I’ve been sober for 5 years now.) The sonnets are these kind of little, tender love-songs to my alcoholic/former self (who I can never fully extinguish) which—I hope—also reckon with and help shed light on addiction, malevolent masculinity/whiteness, and which also seek to forgive and release—to heal.

I also have this big, kind of far off ditty of a dream to open a Poetry Center one day, in the Midwest ideally, kind of a little like Poets House in NYC, where events, workshops, reading, writing, and magic can happen. A hub for poetics/healing/joy/collaboration. There will probably be an herbal/plant element too, somehow, as I love working with/growing plants. And music!

I haven’t played music in an organized group in a while, but enjoy being able to play piano and saxophone here and there, when I can, however that happens. I helped transpose, sing, and record a score for a little art movie project, along with Ross Gay and Lauren Harrison, which was super delightful. Music is the literal heart of the world, imo. I listened to 36 days of music this year, ie. for 1/10 of the year I was listening to music, which was kind of staggering and incredible for me to realize.

I love writing long and short form fiction, but have found it removes me from the world too intensely, which, I feel I am supposed to stay more rooted/involved in the World in a proactive sense, so I tend to write poetry and other forms over fiction. I am interested in the hybrid essay form—with poetry hidden inside—and creating/seeking new hybridized forms. There’s so much potential for greatness—and so much to come.

#richard wehrenberg#monster house press#hybrid essay#fiction#poetry#ross gay#lauren harrison#music#midwest#mfa#graphic design#wave books#andrew duncan worthington#bloomington#indiana#cleveland#akron

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Week 4 Writing Exercises

1. In “To a Young Poet” by Mahmoud Darwish, the opening lines stuck with me the most:

“Don’t believe our outlines, forget them

And begin from your own words.

As if you are the first to write poetry

Or the last poet.”

These, in my opinion, were the most memorable because they gave me a bit of advice as a rapper. The Torah asks “who is wise?” Then tells that it is he who is wise is one who learns from all. When I listen to a song – whether Hip-Hop or other – I listen partially from the standpoint of any other listener trying to vibe to a smooth melody or relate to the tone of the musician’s voice. From another point of view, I listen as a scholar trying to find foreign vocabulary, finding which words, syllables, and consonants flow together, and more. For example, the letters B, T, D and P all fit well with lyrics that you want an aggressive sound, whereas letters like s, m, l and h are for softer, deeper flows. After listening to and studying so much music, one starts to hear the same lines being said repeatedly. If it’s a club song: “shake that ass/” If it’s braggadocios rhymes, “My ice cold/” Every country song ever seems to have some reference made to a break up or a beer. The point is, there are so many songs and musical pieces that lines are bound to be repeated. While keeping this in mind, I try to avoid using the oft-repeated vernacular and terminology as much as I can. If I want to talk about my ice (jewelry), I could say it has “got its jacket zipped” instead of simply saying it’s ‘cold.’ If I want to talk about a big booty, I could spit “that mass stretches back to Saturn / imagine a basketball 5 times larger than regulation / get two of ‘em and that’s her tushy.” Once we know what has been said – as well as said too many times – we can start to progress and pave the way for new ways of illuminating the same subjects and concepts.

I also like this excerpt because it tells you to not let this mindset bog you down too much; it allows for balance. Let’s just say that nobody had ever talked about a break up in a song before. Being the first one to try, how would I go about it? I might have thought it to sound like another song, but what if it turned out radically different? Even if it did have an identical line as another song, maybe the context around mine was different or the tone of the tunes fell in two different categories. If I hadn’t let my creative juices flow freely, I may have never made the wonderful piece in the first place. Even the term “getting my creative juices flowing is an entirely overused terminology, but it still does the job so we keep using it.

2. I read the poem “A Song and The Sultan” by Mahmoud Darwish and the most powerful lines to me were: “That songs like tree trunks may die in one land

but sprout in every country

The blue sun was an idea

the Sultan tried to submerge

but it became the birthday of an ember.”

I like this the best because it shows that good and peace will always find its way. In a literal sense, if you cut down a tree, five more will grow in the same area in due time. If you shoot down a bird, five more will fly over. The one bad part about this truth is its opposite: that which is bad can return. For example, if there is a dictator in a country that is awful and mean and terrible, someone assassinates him. But then the dictator that comes to rule following the murder is even worse, the evil returns. I think it’s more applicable to the good still.

This poem is also cool because it makes indirect comparisons to Messiahs. Whether it be someone like Joan of Arc, Moses, Jesus, or someone else with radical ways of considering the world, the natural response of the people is to freak out, call them a witch and try to kill them. The sad reality is a Messiah (or in my belief, many) Messiahs can be walking amongst us right now, but if they said anything they’d be crucified and called crazy as the never-ending search for the Messiah continues. As if it’s just one. As if a man that came to free the people can no longer be found in this world. The only reason we can’t split red seas and turn water into wine is because we don’t believe we can. And because we have no good reason to. For thousands of years we have been told to be like the almighty and the ones in his stories, but never have these stories tried to convince one that they have the same capabilities. It’s more than difficult to change one’s religious views as one grew up with the mindset and ideology and conformed to it in some way. Imagine trying to change the thinking and followings of thousands of years’ worth of scholarly articles, religious texts, artifacts, and personal beliefs. You can’t even teach a dog new tricks and they only live for 15 years! The Messiahs are not coming; they have not come. They are here, and will continue to be as long as we exist. Know this, and more becomes possible than ever before.

0 notes

Link

Nice job!” says someone who’s come up behind me at the line for the bathroom.

I turn around — they’re smiling at me. A white friend of a white MFA classmate. Sara without an h, friend of Thom with an h. But I’m confused: what have I done to deserve this praise, however generically phrased? What is the job I’ve performed nicely? It’s intermission at a graduate reading and we’re standing on the second floor of a house that a group of MFA classmates share. Maybe I’m being praised for how patiently I’m waiting here to pee.

When I don’t say anything, h-less Sara adds, “That was a wonderful reading!”

And then I want to say, “Wait, whose friend are you, again?”

I want to ask, “You think I’m the one who just read? When I was in the audience, like you? You watched another Asian American writer for twenty whole minutes and then came to congratulate me? Because there can only be one?”

I have trouble remembering how I actually responded. A part of me tries to explain the incident away: Sara saw me from behind; registered my height, skin tone, and hair; made a quick guess. Still, the other Asian American writer’s hair was longer than mine, and wavy. We were also wearing different shirts, pants, shoes. I was wearing glasses. The house was brightly lit. I turned around after hearing “Nice job!”

I’ve been socialized to seek alternative explanations for white people’s erasure of me. I’ve been taught to see isolated mistakes, not a pattern of harm that began long before graduate school, a history of harm long before I came into the world. At the same time, white readers expect me to write about this harm. White writers say to me that they wish they had this kind of suffering to write about, since it’s what’s “hot” in publishing right now.

White writers say to me that they wish they had this kind of suffering to write about, since it’s what’s “hot” in publishing right now.

I wish the racism were not so predictable. I don’t want to seem predictable in my response. I fear that I’m playing into the image of the Suffering Minority that tends to garner praise from white readers. “Nice job!” Do they mean my wistful stare? My famously Asian stoic resilience? Do they even mean me, or do they mean someone else who looks like me — since all they’re paying attention to is a general, generic Asianness? I worry that even when I write with humor, with sarcasm and absurdity, a white reader will see only the Racial Woe. I worry that even when I write of delight and tenderness and pug dogs, a white reader will still proclaim, “This is clearly about how hard it was to immigrate.”

After a recent reading, a white attendee came up to tell me how they were on their way to their Chinese friend’s place to make dumplings. They highlighted a poem of mine in which a mother and son make dumplings together; they were definitely going to mention this poem to their Chinese friend. On the one hand, I was glad this person found something to connect with in my work and I could tell they were excited by the coincidence — my poem, their plans for the rest of the evening. On the other hand, I’d thought the poem was investigating a much more complicated relationship to Chineseness, one that acknowledges the role of pop culture and texts like The Joy Luck Club, one that is hesitant to include a dumpling-making scene because of an awareness of white readers’ expectations.

I worry that even when I write of delight and tenderness and pug dogs, a white reader will still proclaim, “This is clearly about how hard it was to immigrate.”

I’d intended the poem to subvert such expectations. Instead, this white audience member seemed to feel that their expectations had been met. To them, the dumplings were an example of straightforward Chineseness, something that bonded two generations in their immigrant hardship. This interpretation felt like another instance of “Nice job!” — a form of praise that is about the white reader’s relationship to otherness, rather than about what the writer of color is exploring in their relationship to an identity category and the associated set of cultural practices.

How anyone ends up interpreting my work is out of my hands, of course; I can’t expect in-depth analysis every time, especially after just one reading event. I believe in the complexity of what I’ve created; I hope that readers will, in their own time, discover that. But here, too, is a pattern, a history: white readers tend to be the ones commenting on or asking about the obviously Chinese references in my work. Rarely am I asked by white readers about my references to Pablo Neruda or to Audre Lorde or to, in that same poem with the dumplings, Mahmoud Darwish. I don’t always expect close reading or listening. I’m asking for reading, listening. When I think back to that dumpling-loving white audience member, I wonder if they would’ve said exactly the same thing to Amy Tan, after a reading of hers. Is “I’m going to make dumplings with my Chinese friend” just a thing one says to any writer of Chinese descent?

When ‘Good Writing’ Means ‘White Writing’

We do students of color a disservice by imposing the style of an overwhelmingly white canonelectricliterature.com

When I tweeted the other week about some of these issues — in particular, how white writers say they wish they had racial suffering to write about, to get published for — I got another type of response that I’ve come to anticipate: “Those writers are just jealous of your success!” And this response was coming from white writers who seemed to understand my overall argument. I mention the “just jealousy” explanation here because it inadvertently implies that white writers are not really saying or doing racist things; they’re expressing an emotion that, while bad, is human. So once again white writers get to be fully human, full of emotions. The “just jealousy” explanation makes me think of all the times I’ve confided in a white colleague that someone said something racist and then the colleague said, “Oh they must be upset because…” or “They’re only acting like that because…” as though the problem is not racism but a personal issue, and I’m supposed to empathize.

I don’t want to do that emotional labor. And I don’t want to do a “nice job.” I want to keep digging into the messiness that is my relationship to race, as well as sexuality, as well as the napping rhino at the Seneca Park Zoo in Rochester, New York. I’m working toward a language that’s accurate about and embracing of the kinds of joy I feel, the kinds of sorrow, the kinds of emotion not visible to the white gaze. I want to say, this poem starring a napping rhino is an Asian American poem; in fact, despite it not being about how hard it was to immigrate, it is the most Asian American poem I have ever written.

0 notes