#the witch hazel tree

Text

THE SPIDER PRINCE TRILOGY IS OUT NOW

In the town of Fairy Hill, Alberta, Canada, it’s easy to get cursed and difficult to break them. Author Wilshire, Edna Koch and Eddie Karpinski are all painfully aware of this truth. As they navigate young adulthood, they’re forced to deal with curses, battles, faerie royalty, powerful enemies, and misunderstood magic.

Alongside their friends, Nuisance, Pan, Darling, and the Spider Prince, the human trio embark on a journey of friendship, sacrifice, and love.

New Adult Fantasy! Faeries! Witches! Girls with swords! Queer characters & themes! Support an indie author!

The Spider Prince Trilogy by Leandra Inglis - all three books available NOW!!

#books#bookblr#fantasy books#new adult#new adult books#new adult fantasy books#indie author#independent author#faeries#fey#fae#fae fantasy#the spider prince trilogy#chaos and the spider prince#the witch hazel tree#spider spider bee#might actually pay to boost this post lmao#come through tumblr i'm counting on you <3

131 notes

·

View notes

Text

🖤🔮✨

#celtic tree zodiac#green witch#lunar witch#witchyvibes#gemini#witchy blog#magic#witchcraft#baby witch#elder#hazel#willow#reed#holly#adler#ash#oak#ivy#roman#hawthorn#vine#birch

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Botanical garden, Berlin

#rainy windy dark and cold#i was the only one walking outside#there were good shapes#the raindrops on the bare branches#bright spots of witch hazel#trees

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Betula Lenta - Cherry Birch Bark

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

How to Read the Tree Leaves

A Little Knowledge of Botany can be helpful, even if you’re an Amateur Gardener. Here are a few things you should know about what happens in the fall.

— By Margaret Roach | November 16, 2022 | The New York Times

Fallen leaves carpet the ground beneath a red maple (Acer rubrum) at the New York Botanical Garden, in the Bronx. Credit...New York Botanical Garden Photo

What’s going on out there — and why? Some version of that is the perennial question on any inquisitive gardener’s mind.

Fall provides plenty of dramatic subject matter along those lines, beyond the changing leaves. What is it exactly that gives the foliage of deciduous trees the signal to let go (except in the case of contrarians like certain oaks and beeches)?

Although we call them evergreens, the inner needles of many conifers show us otherwise each autumn. Why do they turn noticeably yellow and brown, in preparation for shedding?

And as the deep, cold of a Northern winter approaches, what gardener does not wonder how dormant buds and other tender-looking parts of plants survive intact?

A hunger to explain such phenomena led me to a beginning botany course and its accompanying textbook. In the decades since, I have revisited those lessons time and again.

Japanese maple leaves and other fallen foliage cover the ground at the New York Botanical Garden. Credit...New York Botanical Garden Photo

Apparently, I am not alone in my search for answers. The textbook used in that course, Brian Capon’s “Botany for Gardeners: An Introduction to the Science of Plants,” has sold more than 260,000 copies since it was published in 1990. In August, the fourth edition was released.

And the course itself, Introduction to Plant Science, is now given year-round at the New York Botanical Garden, virtually and in person, with up to 12 sessions a year and as many as 20 students in each. It is one of more than 700 annual offerings in subjects as diverse as botanical illustration, landscape design, psychedelic mushrooms and paleobotany — all part of the nation’s largest plant-focused adult continuing-education program.

Perhaps my biggest takeaway from the classes I attended: Putting some botany into our horticulture can help improve results in the garden. But best of all, it deepens our appreciation of how plants live their hard-working lives.

In the fall, the conservatory at the New York Botanical Garden is enlivened by honey locust trees (Gleditsia triacanthos). Shorter days and cooler weather trigger chlorophyll breakdown in the foliage, unmasking yellow and orange carotenoid pigments that had been there all along. Credit...New York Botanical Garden Photo

Batten Down the Hatches: Dormancy

Dormancy is a “virtual metabolic standstill,” wrote Dr. Capon, who died last year but was a professor of botany at California State University, Los Angeles, for decades.

In the temperate zone, “it’s an ecological adaptation for living in a cold environment, to survive the cold,” said Regina Alvarez, an assistant professor of biology at Dominican University New York, in Rockland County, and one of New York Botanical Garden’s botany instructors. “Depending on the life cycle and the form of the plant, they do it in different ways.”

Herbaceous plants have two choices: They can complete their life cycles and leave only their seeds behind for the following year (annuals), or their aboveground portions can die back, leaving the roots and storage organs like rhizomes, bulbs and corms to carry on when favorable conditions resume (biennials and perennials).

A Fern-Leaf Maple (Acer Japonicum Aconitifolium) in its fall glory at the New York Botanical Garden, with hot-colored foliar pigments taking center stage, after the chlorophyll that dominated the growing season recedes. Credit...New York Botanical Garden Photo

But woody plants can’t completely tuck in like that. Even those that drop their leaves as part of their overall defense have parts that remain exposed. Those include organs as small and seemingly vulnerable as the buds of next year’s leaves and flowers, or the growing tips of twigs and branches where elongation will resume again come spring.

In preparation, the undeveloped flowers, leaves or shoots may become encased in overlapping bud scales every autumn. Some species may also coat the covered buds in “a thick resin to protect them from the cold and wind,” said Leslie Day, the author of urban-focused natural history guides, including “Field Guide to the Street Trees of New York City,” and a plant-science instructor at the botanical garden.

It’s not just the buds that benefit from the waterproof sealant. Some insects do, too. Honey bees, for instance, mix the resin they scrape from bud scales and other plant parts with their saliva to produce propolis, which they use as a glue to seal cracks in their hives, Dr. Day said.

Another unexpected application for the antimicrobial sealant: “To embalm large intruders like mice and wasps that are too heavy to carry out after they sting them to death,” she said. Noted: Nature provides — and it wastes nothing.

In preparation for winter, many woody plants encase their undeveloped flowers, leaves or shoots in overlapping bud scales. Some species may also coat the covered buds in a thick resin for extra protection. Credit...Brian Capon

The Coloring Up, and the Letting Go

We watched the recent show, as shorter days and cooler weather triggered the breakdown of chlorophyll, the predominant pigment in most leaves. What was unmasked are known as the accessory pigments, Dr. Alvarez said, including yellow and orange carotenoids that were there all along, in a supporting role. Although hidden during the growing season, they were helping with photosynthesis.

The anthocyanin pigments that we perceive as red and purple in dogwoods, sumacs or red oaks, however, weren’t hiding. They are produced in fall, products of a chemical change involving an increased concentration of sugars in the leaves.

Then — no matter the color, but all too soon for our liking — the foliage on most deciduous trees takes flight. The big event’s timing is determined by changing chemistry in the tiny abscission zone, a narrow band of cells at the base of each petiole, or leaf stalk, where it attaches to the stem or branch.

“None of this would happen without the plant hormones,” Dr. Day said.

Which hormone is at work in leaf drop? Not abscisic acid, the one that “abscission zone” would seem to imply. That hormone tells the plant to form the bud scales, to stop certain aspects of growth ahead of dormancy and even to keep the seed dormant until the time is right for germination, Dr. Day said.

It is now understood instead that ethylene — better known for its role in ripening fruits — is the catalyst. (Fruit and flowers, with their own specialized abscission zones and timing, are likewise influenced by ethylene on when to drop.)

“It starts to break down the cell membranes and form this zone where the leaf eventually can just fall,” Dr. Day said, “sealing itself off and leaving a scar on woody plants.” A thin cork layer forms to prevent water loss and fungal invasions.

A scar left behind after the dropping of a northern Catalpa leaf (Catalpa speciosa). The letting go is controlled by chemistry in the tiny abscission zone, a narrow band of cells at the base of each leaf stalk, where it attaches to the stem. The distinctive scars can aid in winter tree identification. Credit...Regina Alvarez

The outline of each scar forms a shape like an oval or a heart, Dr. Alvarez said. Dots inside that outline mark where the plant’s vascular tissues, the xylem and phloem, were connected, and conducted fluids between stem and leaf.

These scars can be very distinctive. How have I never looked at them?

Plenty of garden downtime lies ahead for such exploration. The scars are a useful tool for winter tree identification, said Dr. Alvarez, who admits that she and Dr. Day “get obsessive over leaf-scar photos.”

Dr. Day explained: “You learn to look at the scars and say, ‘Oh, that’s an Ailanthus’ or ‘That’s a horse chestnut.’”

The horse chestnut (Aesculus hippocastanum), for example, with its big compound foliage, “leaves behind what looks like a little horseshoe or smiley-face scar,” she said.

A portion of the New York Botanical Garden’s Benenson Ornamental Conifers collection in winter. The often narrow foliage of conifers is winter-adapted: It is less vulnerable to the effects of ice, snow and wind than broader leaves, and coated in a waxy substance. Credit...New York Botanical Garden Photo

When Leaves Don’t Fall (at Least Not Right Away)

How can so much be governed by such a microscopic piece of real estate?

“The restriction of ethylene’s destructive effects only to cells in the abscission zone illustrates the precise control plants exercise over their hormone systems,” Dr. Capon wrote.

Nowhere is this engineering prowess more astounding than in the deciduous trees and shrubs that hold onto their dead leaves all winter, only to release them in spring. To accomplish that, they must manage to keep just that attachment point up and running — the junction of a dead leaf and a dormant twig. Preposterous.

The inner Needles of a White Pine (Pinus Strobus) preparing to shed. Conifers don’t complete an annual shed like deciduous trees, but a portion of their oldest needles do drop each year. How long each needle holds on is particular to the species, ranging from two years to four or more. Credit...Margaret Roach

The trait, called Marcescence, is common to some Witch-Hazels (Hamamelis) and certain Hornbeams (Carpinus), Beech (Fagus) and Oaks (Quercus), especially in the lower branches and in younger trees.

Scientists hypothesize that the persistent leaves may have developed long ago, as an adaptation against browsing by large animals the plants evolved alongside. A mouthful of dead leaf is a less-tasty target than a bare twig and tender buds, something today’s deer also seem to understand.

A bonus design tip for gardeners: A row of marcescent trees, although not technically evergreen, makes for an effective, nearly year-round screen.

A hybrid witch-hazel (Hamamelis x intermedia Jelena) in February bloom, still holding last year’s faded leaves. Some deciduous woody plants hold their dead leaves until spring, a trait called marcescence, by keeping just the tiny attachment points up and running. Credit...Margaret Roach

Those Yellow and Brown Inner Conifer Needles

For something evergreen, we often turn to conifers — although they aren’t technically evergreen. Their often narrow foliage is winter-adapted: less vulnerable to the effects of ice, snow and wind than broader leaves, and coated in a waxy substance that guards against the elements.

“They’re always green,” Dr. Alvarez said, “but that doesn’t mean it’s always the same needles.”

When she worked for the Central Park Conservancy, Dr. Alvarez heard the question regularly starting in the early fall, when the inner foliage of many conifers turned yellow and brown. “What’s wrong with the trees?” visitors wanted to know.

As part of their life cycle, conifers undergo leaf drop, too. But it’s a sequential one — not an annual process like that of deciduous trees, and not to be confused with discolored foliage throughout the tree or at the branch tips at other times, which may indicate disease or injury.

Each year, the oldest foliage fades and prepares to fall. How long each needle holds on before that is particular to the species, ranging from two years to four or more.

Admittedly, the process can look alarming.

There’s no need to panic, though. Nothing’s wrong — provided you know a little about how to read the tree leaves.

#Botany#Trees#Tree 🌴 🌲 Leaves 🍁 🍂 🍃#Amateur Gardener#Margaret Roach#The New York Times#Fallen Foliage#New York Botanical Garden 🪴#Needles of a White Pine 🌲#Marcescence | Witch-Hazels

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#catholic gardener#garden#gardening#personal photos#trees#autumn#mushrooms#flower#ginkgo#hazel#allium#onion#fungus#witches cap

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

spring starts as early as you want it to

1 note

·

View note

Text

0 notes

Text

Growing a Fragrant Year: February's Helpful Hazel and the Greenhouse Diaries

Witch hazel isslustration by Leonie Bell Circa 1960s

With a scent ranging from sweet yeasted bread to bubblegum, the centuries-old Hamamelis virginiana (aka the common witch hazel) kicks off Month #1 in this year’s Greenhouse Diaries series. In case you missed our introductory post last month, our theme for 2024 is a Fragrant Year, where we’ll be sharing twelve months of perfumed plants, flowers…

View On WordPress

#colonial gardens#featured#fragrant plants#Garden#gardening#greenhouse diaries#medicinal garden plants#medicinal plants#native plants#spring#spring trees#witch hazel#witch-hazel

1 note

·

View note

Text

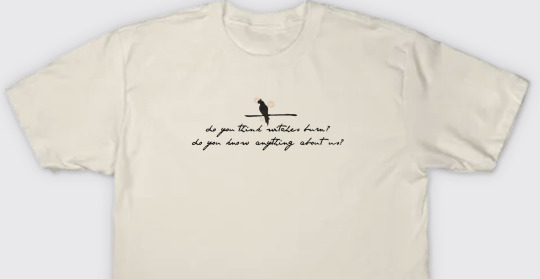

Are you a fan of the SPIDER PRINCE TRILOGY? Do you like supporting indie authors and stories? Say hello to the brand-new World of Faerie Merch Collection, featuring such hits as...

supporting a brand that doesn't exist in reality!

a slightly dated, but truly classic, meme!

the obligatory quote from the source material that could maybe pass as a random slogan!

and breaking the first rule of fight club!

If you want to vote on what the next piece of merch will be, head over the official lionofstone discord server, where there are three additional designs to choose from!

#the spider prince trilogy#chaos and the spider prince#the witch hazel tree#spider spider bee#leandra inglis#merch#we are Manifesting okay we are behaving as though this series is insanely popular and people really want merch for it#okay thank you goodnight (it's 11.24am)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hazel Tree Month Begins

In celtic druidry, the year is separated in to 13 months, each one sacred to a tree.

Today is the start of Hazel Tree month. Aug 5 - Sept 1 Those born under the Hazel are smart, intuitive, unique, and have an excellent eye for detail. However, they can be fussy and need to be careful to not appear arrogant. Their intelligent and detailed oriented nature means that they are typically very good at organising or fact finding. Those born under the Hazel are excellent thinkers, planners, and always find chances to learn new things.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Witch hazel/20.03.2023

#witch hazel#trees#botanical#spring#photography#beautiful#nature#landscape#floral#my photography#springtime#hello spring#myphone

1 note

·

View note

Text

There, in the sunlit forest on a high ridgeline, was a tree I had never seen before.

I spend a lot of time looking at trees. I know my beech, sourwood, tulip poplar, sassafras and shagbark hickory. Appalachian forests have such a diverse tree community that for those who grew up in or around the ancient mountains, forests in other places feel curiously simple and flat.

Oaks: red, white, black, bur, scarlet, post, overcup, pin, chestnut, willow, chinkapin, and likely a few others I forgot. Shellbark, shagbark and pignut hickories. Sweetgum, serviceberry, hackberry, sycamore, holly, black walnut, white walnut, persimmon, Eastern redcedar, sugar maple, red maple, silver maple, striped maple, boxelder maple, black locust, stewartia, silverbell, Kentucky yellowwood, blackgum, black cherry, cucumber magnolia, umbrella magnolia, big-leaf magnolia, white pine, scrub pine, Eastern hemlock, redbud, flowering dogwood, yellow buckeye, white ash, witch hazel, pawpaw, linden, hornbeam, and I could continue, but y'all would never get free!

And yet, this tree is different.

We gather around the tree as though surrounding the feet of a prophet. Among the couple dozen of us, only a few are much younger than forty. Even one of the younger men, who smiles approvingly and compliments my sharp eye when I identify herbs along the trail, has gray streaking his beard. One older gentleman scales the steep ridge slowly, relying on a cane for support.

The older folks talk to us young folks with enthusiasm. They brighten when we can call plants and trees by name and list their virtues and importance. "You're right! That's Smilax." "Good eye!" "Do you know what this is?—Yes, Eupatorium, that's a pollinator's paradise." "Are you planning to study botany?"

The tree we have come to see is not like the tall and pillar-like oaks that surround us. It is still young, barely the diameter of a fence post. Its bark is gray and forms broad stripes like rivulets of water down smooth rock. Its smooth leaves are long, with thin pointed teeth along their edges. Some of the group carefully examine the bark down to the ground, but the tree is healthy and flourishing, for now.

This tree is among the last of its kind.

The wood of the American Chestnut was once used to craft both cradles and coffins, and thus it was known as the "cradle-to-grave tree." The tree that would hold you in entering this world and in leaving it would also sustain your body throughout your life: each tree produced a hundred pounds of edible nuts every winter, feeding humans and all the other creatures of the mountains. In the Appalachian Mountains, massive chestnut trees formed a third of the overstory of the forest, sometimes growing larger than six feet in diameter.

They are a keystone species, and this is my first time seeing one alive in the wild.

It's a sad story. But I have to tell you so you will understand.

At the turn of the 20th century, the chestnut trees of Appalachia were fundamental to life in this ecosystem, but something sinister had taken hold, accidentally imported from Asia. Cryphonectria parasitica is a pathogenic fungus that infects chestnut trees. It co-evolved with the Chinese chestnut, and therefore the Chinese chestnut is not bothered much by the fungus.

The American chestnut, unlike its Chinese sister, had no resistance whatsoever.

They showed us slides with photos of trees infected with the chestnut blight earlier. It looks like sickly orange insulation foam oozing through the bark of the trees. It looks like that orange powder that comes in boxes of Kraft mac and cheese. It looks wrong. It means death.

The chestnut plague was one of the worst ecological disasters ever to occur in this place—which is saying something. And almost no one is alive who remembers it. By the end of the 1940's, by the time my grandparents were born, approximately three to four billion American chestnut trees were dead.

The Queen of the Forest was functionally extinct. With her, at least seven moth species dependent on her as a host plant were lost forever, and no one knows how much else. She is a keystone species, and when the keystone that holds a structure in place is removed, everything falls.

Appalachia is still falling.

Now, in some places, mostly-dead trees tried to put up new sprouts. It was only a matter of time for those lingering sprouts of life.

But life, however weak, means hope.

I learned that once in a rare while, one of the surviving sprouts got lucky enough to successfully flower and produce a chestnut. And from that seed, a new tree could be grown. People searched for the still-living sprouts and gathered what few chestnuts could be produced, and began growing and breeding the trees.

Some people tried hybridizing American and Chinese chestnuts and then crossing the hybrids to produce purer American strains that might have some resistance to the disease. They did this for decades.

And yet, it wasn't enough. The hybrid trees were stronger, but not strong enough.

Extinction is inevitable. It's natural. There have been at least five mass extinctions in Earth's history, and the sixth is coming fast. Many people accepted that the American chestnut was gone forever. There had been an intensive breeding program, summoning all the natural forces of evolution to produce a tree that could survive the plague, and it wasn't enough.

This has happened to more species than can possibly be counted or mourned. And every species is forced to accept this reality.

Except one.

We are a difficult motherfucker of a species, aren't we? If every letter of the genome's book of life spelled doom for the Queen of the Forest, then we would write a new ending ourselves. Research teams worked to extract a gene from wheat and implant it in the American chestnut, in hopes of creating an American chestnut tree that could survive.

This project led to the Darling 58, the world's first genetically modified organism to be created for the purpose of release into the wild.

The Darling 58 chestnut is not immune, the presenters warned us. It does become infected with the blight. And some trees die. But some live.

And life means hope.

In isolated areas, some surviving American Chestnut trees have been discovered, most of them still very young. The researchers hope it is possible that some of these trees may have been spared not because of pure luck, but because they carry something in their genes that slows the blight in doing its deadly work, and that possibly this small bit of innate resistance can be shaped and combined with other efforts to create a tree that can live to grow old.

This long, desperate, multi-decade quest is what has brought us here. The tree before me is one such tree: a rare survivor. In this clearing, a number of other baby chestnut trees have been planted by human hands. They are hybrids of the Darling 58 and the best of the best Chinese/American hybrids. The little trees are as prepared for the blight as we can possibly make them at this time. It is still very possible that I will watch them die. Almost certainly, I will watch this tree die, the one that shades us with her young, stately limbs.

Some of the people standing around me are in their 70's or 80's, and yet, they have no memory of a world where the Queen of the Forest was at her full majesty. The oldest remember the haunting shapes of the colossal dead trees looming as if in silent judgment.

I am shaken by this realization. They will not live to see the baby trees grow old. The people who began the effort to save the American chestnut devoted decades of their lives to these little trees, knowing all the while they likely never would see them grow tall. Knowing they would not see the work finished. Knowing they wouldn't be able to be there to finish it. Knowing they wouldn't be certain if it could be finished.

When the work began, the technology to complete it did not exist. In the first decades after the great old trees were dead, genetic engineering was a fantasy.

But those that came before me had to imagine that there was some hope of a future. Hope set the foundation. Now that little spark of hope is a fragile flame, and the torch is being passed to the next generation.

When a keystone is removed, everything suffers. What happens when a keystone is put back into place? The caretakers of the American chestnut hope that when the Queen is restored, all of Appalachia will become more resilient and able to adapt to climate change.

Not only that, but this experiment in changing the course of evolution is teaching us lessons and skills that may be able to help us save other species.

It's just one tree—but it's never just one tree. It's a bear successfully raising cubs, chestnut bread being served at a Cherokee festival, carbon being removed from the atmosphere and returned to the Earth, a wealth of nectar being produced for pollinators, scientific insights into how to save a species from a deadly pathogen, a baby cradle being shaped in the skilled hands of an Appalachian crafter. It's everything.

Despair is individual; hope is an ecosystem. Despair is a wall that shuts out everything; hope is seeing through a crack in that wall and catching a glimpse of a single tree, and devoting your life to chiseling through the wall towards that tree, even if you know you will never reach it yourself.

An old man points to a shaft of light through the darkness we are both in, toward a crack in the wall. "Do you see it too?" he says. I look, and on the other side I see a young forest full of sunlight, with limber, pole-size chestnut trees growing toward the canopy among the old oaks and hickories. The chestnut trees are in bloom with fuzzy spikes of creamy white, and bumblebees heavy with pollen move among them. I tell the man what I see, and he smiles.

"When I was your age, that crack was so narrow, all I could see was a single little sapling on the forest floor," he says. "I've been chipping away at it all my life. Maybe your generation will be the one to finally reach the other side."

Hope is a great work that takes a lifetime. It is the hardest thing we are asked to do, and the most essential.

I am trying to show you a glimpse of the other side. Do you see it too?

#american chestnut#hope#climate change#biodiversity crisis#climate crisis#trees#plantarchy#learning to imagine the future

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

Just agreed to go to the garden store with my housemate later today. Was that a mistake? Maybe. But having potential barriers makes it more fun tbh. Might not be saying that when it drops while we’re buying our plum tree, but also we’re gonna have a plum tree, so…

#trees are 50% off#and hydrangeas are 40% off#so far I’ve gotten a witch hazel tree a fun dogwood bush with bright red bark and a cherry tree out of this sale#good times

0 notes

Text

Base Structures of 150 year old Tulip Poplars

#they get large fast!#tulip poplar#tree#the second one has a stream going through it#and some witch hazel

3 notes

·

View notes