#thanks for the ask alexei! 💜

Note

Hello there, Master Bailey! I hope you are doing well old friend. I absolutely love the creativity you put into the Jedi ask game, so if it’s cool w you, could you please do 12, 27, 46 for Ahsoka? Thank you! May the Force be with you! 💜

HI ALEXEI!!!!! It’s so good to hear from you 🥹 I’m doing well and I sincerely hope you are too! 💜 I will happily answer these questions for you and I’m glad you chose Ahsoka because given all the clownery with the show, we could use some positivity! 🧡🤍💙 And May the Force be with you always my friend! ☺️

(Original Jedi Ask Game Questions linked down below!)

12-Favorite Kind Of Missions

Rescue Missions. Ahsoka seems to be the most passionate when it comes to rescuing people in need. We see it right off the bat when Plo Koon in the first few episodes of Clone Wars, with Barriss in weapons factory, saving Mandalore against Maul, helping the Rebels against Vader, and stopping Morgan’s evil reign against a town, etc. Hell, one of her famous quotes is all about helping people in need so I would for sure say rescue missions. She isn’t kill happy like Anakin and she’s not into politics/negotiation like Obi-Wan, she’s like somewhere in the middle.

27-What Are Her Feelings On Her Birth Culture?

Based on how Ahsoka dresses and the fact that she has the headdress that girls her age and species typically wear, it’s safe to say that she does respect and love where she comes from, but not enough to wear she’s like homesick or feels like she should be living in Shilli. I like to think that Shaak Ti and Ahsoka would go in field trips so that Ahsoka is educated on her roots. However, I believe Ahsoka is very content with her Jedi family which is why her decision to leave was so heartbreaking for her. Perhaps in the future, Ahsoka is able to visit Shilli and explore more of it when it’s safe to.

46-My Favorite Headcanon About Her

That Ahsoka is in love with Barriss and that they found each other again and Ahsoka got the apology she deserves and they were able to make amends. We may not have seen much of their relationship on screen but based on the few interactions we’ve seen of them, you would have to be blind not to see that they care deeply about the other. We can just ignore the bullshit that is the Wrong Jedi arc (that didn’t happen what are y’all talking about?!)Their facial expressions and actions towards the other say enough and for Force sake cant these girls just have peace and happiness for once!?And can’t we see a couple in Star Wars not in tragedy!?

Link to Ask Questions

9 notes

·

View notes

Note

Heyyy <333

Thoughts on bail and breha?

Gods yes, hello there! 💜

Bail and Breha are the couple and I don’t say it enough, but I love these two together! All they wanted was to raise a beautiful baby girl and that they did. I wish they were my parents and they are incredible together. Bail loves Breha even through her physical disabilities, what an absolute icon. Makes me want to binge / write / cry over some fic.

Thank you for the kind ask!

from this ask game!

#absolute duo#also their fashion sense is 😳🤌✨💜#i love your honour#thank you for the ask and have a wizard day#alexei asks

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hellohellohello!

I'm not even really here, but I just saw this, and you know me, I can't resist because I'm nosy AF. So:

⭐ ??? Go wild!

(Also, if you want: Which character was/is surprisingly difficult to write? Which one turned out be much easier than you anticipated?)

Heyyy J, thanks for once again giving me the go ahead to talking about my own writing 😁🥰

I'll start with the last questions:

Who was surprisingly difficult to write? Tony. Definitely Tony. Idk, I was already daunted and unsure when I first started writing him, but thought I could wing it by throwing in the sarcasm and one liners. And they do work, they just kinda turn him into a caricature, which I didn't want. I still think I'm not really getting him *right*, you know, but I couldn’t say why exactly.

The others that were also hard to write at first are Bruce and Thor, but since they were always minor characters and then basically disappeared from the story for a while, it wasn't so bad. Except now I'm post-Snap with writing and am reminded of all my shortcomings.

Who was surprisingly easy? The boring answer is Natasha, but I've talked about this extensively already. The other boring answer is Sam, but I haven't gotten to him yet with the posted chapters, so I'll withhold information on that for now.

So, I'll go with Fury! I was scared of the Secret Agent Talk, but I think he turned out pretty well. Same goes for Maria Hill actually. And Rhodey too. It's very comic book politics, but I ended up exploring the "realistic" parts of the MCU (ie politics and consequences of the on-screen actions) and that's really fun!

Okay, so with the commentary I picked a scene from chapter 28 of Hand of a Devil. I'm not sure if you've gotten to that already, so (very small) spoiler warning if you haven't! I'll put it under the cut, feel free to ignore it.

There's quite some rambling, but I hope it's at least a little fun to listen to read. Thanks again for the ask, I always appreciate it 💜

⭐️ And if anybody else wants a director's cut, please send me more asks! ⭐️

"What does he even want to be now, a superhero?" She huffs indignantly, her mind flashing back to Alexei in his Red Guardian uniform. "There's no such thing."

She can picture Clint raising his eyebrows as he replies. "Well, the three-year-old with the Captain America action figure sitting beside me would beg to differ."

Natasha knows the one he's talking about. Cooper loves Captain America. Cooper also loves Play Doh and Sesame Street.

"I never did understand what that was about," she tells Clint. Her most vivid memories of Captain America were the cartoons she and Yelena sometimes watched during their time in Ohio. "What does an army need a figurehead for? Blatant propaganda."

"He's much cooler than that, come on!" Clint sounds personally insulted. "With the shield and the attitude... The guy practically invented guerrilla warfare, and I read this biography once where –"

I love this scene for a lot of reasons. Not just because Clint and Natasha are always a joy to write together, but because I really enjoy throwaway comments and references like this.

With these lines in particular, what I was trying to do (and I think it worked pretty well) is show the different ideas that Clint and Natasha have about Steve Rogers and/or Captain America, due to their cultural backgrounds and upbringing, before anyone even discovered that Steve was still alive.

Natasha thinks of Cap as a figurehead. She only knows him as either propaganda or a character for children, like merchandise of the United States.

Clint, on the other hand, would've learned about Steve Rogers in history class, at least to some extent. He got taught the strategic value of what Cap and the Howlies did, not just the propaganda aspects. And my version of Clint in particular is kind of a history enthusiast, so he's a bit of a fan too.

And in a way, both are right! Clint's got the perspective on where Steve's coming from, Natasha on what people have turned him into during his absence, while he was in the ice. What's interesting (imo) is how this affects how they meet Steve when he comes back.

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

Sorry if this has been asked before but do the LIs have a favourite season (winter, spring, etc.)? Also thank you for answering our questions, we all appreciate it so much 💜

Leo - Summer

Brooklyn - Fall

Alexei - Spring

Tobias - Summer

Milo & Rory - You'll find out later!

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

We Were Something, Don’t You Think So? [Chapter 1: Tobolsk, Siberia]

You are a Russian Grand Duchess in a time of revolution. Ben Hardy is a British government official tasked with smuggling you across Europe. You hate each other.

This is a work of fiction loosely inspired by the events of the Russian Revolution (1917-1923) and the downfall of the Romanov family. Many creative liberties were taken. No offense is meant to any actual people. Thank you for reading! :)

Song inspiration: "the 1" by Taylor Swift.

Chapter warnings: Nothing...?! This might be a first for me.

Word count: 3.9k.

Link to chapter list (and all my writing): HERE.

Please let me know if you’d like to be added to the taglist! 💜

*** I'm going to tag like a bazillion people since this is the first chapter of a new fic, but I WILL NOT TAG YOU AGAIN unless you ask me to. I hope you are all doing well, wherever you are in the world. 🥰😘 ***

Tagging: @queenlover05 @someforeigntragedy @imtheinvisiblequeen @joemazzmatazz @inthegardensofourminds @deacyblues @youngpastafanmug @hardyshoe @tensecondvacation @madeinheavxn @whatgoeson-itslate @brianssixpence @simonedk @herewegoagainniall @babyzellodeacon @culturefiendtrashqueen @pomjompish @yourlocalmusicalprostitute @allauraleigh @im-an-adult-ish @rhapsodyrecs @queen-turtle-boiii @haileymorelikestupid @bohemianbea @hijackmy-heart @acdeaky @jennyggggrrr @some-major-ishues @okilover02 @girlafraidinacoma @misc-incorporated @brianmayspinkyring @littlespoiltthing @madeinheavxn @quarterback-5 @escabell @confusedhalfofthetime @queenborhaplovergirl @atwinklingsound @rest-is-detail @standing-onthe-edge @pattieboydwannabe @dinkiplier @adrenaline-roulette @fancybenjamin @itscale @thesunburntpotato @peculiareunoia @sparkleslightlyy @whatgoeson-itslate

“There is a man coming for you.”

Mother’s words are very soft, so our jailers can’t hear them, and in English, so they wouldn’t be able to understand anyway. The stained-glass lamp on the vanity illuminates her drawn face in amber, gold, bumblebee jasper, a sickly yellow like jaundice. She stands behind me, dragging the brush through my hair, as I lock eyes with her reflection in the mirror. I knew this was coming when she walked into my bedroom shortly before midnight, or at least that something important was; Mother rarely leaves her wheelchair these days, and certainly not to brush anyone’s hair. Well…perhaps if it was Alexei’s. I nod seriously, gravely even, because that’s how Mother sees this: as a matter of great consequence, of great responsibility. But deep down—beneath this nightgown of linen and lace, beneath this prickling skin, beneath these bones handed down through centuries by the ruling dynasties of Europe—I’m so ecstatic I could scream it from rooftops.

“You’ll know him by his accent,” Mother continues, still brushing. She absently hammers through the tiny knots her fingers stumble across. “He’ll be British, and fairly young. He’s one of Sir Buchanan’s staff.”

I nod again, ostensibly solemn, weighed down by the gravity that only comes to people with years, if it comes at all. My reflection impresses even me. We’re co-conspirators in this mission.

“So don’t be alarmed when he presents himself. He’ll do so when it is most opportune, likely within the next few days. And be ready to leave with him immediately. You may not have any warning. Have you finished hemming your dresses?”

By hemming my dresses, she means secretly sewing our family jewels into them. It’s something we’ve all been doing since we were brought to Tobolsk one month ago. At Alexander Palace in Saint Petersburg, where we were first detained after Papa’s abdication, life had been almost normal: little supervision, plenty of comforts, the retaining of most of our retinue. But it’s different here in Siberia, in the mansion of the former governor who was similarly expelled by the tide of what I’ve heard called revolution. Half of our servants have been dismissed. Papa still receives diplomats, but less often than ever before, and only the few that he can still call friends; one of them is Sir Buchanan, who has been the British Ambassador to Russia and a familiar face for as long as I can remember. The soldiers that the Provisional Government has taxed with guarding us roam the hallways, the walking paths, the shifting shadows of long rooms; they stalk like wolves, their eyes narrow and wary and hateful. And the comforts that remain in our hands feel as fragile as the dwindling Russian summer.

“My dresses are in immaculate condition, I can assure you,” I tell Mother. This is my attempt at humor; my stitching is notoriously hideous. She doesn’t seem to hear me.

“It has to be now,” Mother says, and her knobby, arthritic hands stop brushing. Her eyes have taken on a glassy, far-away quality. “It’s the first week of September. Soon it will be too cold for you to travel safely. And if they take any more from us, if they leave us with no privacy at all, no visitors…if they move us any farther east…we’ll never have another opportunity to get someone out.”

And that someone has to be me, the middle daughter, the third of five extraneous non-heirs. Olga is too timid, too anxious, her nerves could never survive the journey. She’d give herself an ulcer within days and spend the rest of the trip retching blood into rubbish bins. Tatiana is too beautiful; and that may seem like a ridiculous reason for her not to go, but it is also a genuine one, because she is the only Romanov daughter that the average Russian could pick out in a crowd. She is tall and willowy and has striking, wide-set eyes and flawless skin and is just generally an angel fallen to Earth and a rather sizable dent to the ego to have as a sister. Maria is too pliable, she bends when pushed and always has, like the branches of a weeping willow, shoved by the wind one way and then the other until every last leaf is stripped away. Anastasia is too young, only sixteen, and hopelessly wild as well. This task will require restraint, and strategy, and above all else patience. And little Alexei…even if he did not have hemophilia (which he does, an affliction from Mother’s side of the family, and that is a weight she has never stopped carrying), even if he was not only twelve years old, he is too valuable to risk on a gamble like this. He’s more valuable and more loved than I will ever be. But this doesn’t pain me, and never has, at least not in my recollection. I’ve always considered it less a tragedy than a stark and inevitable truth. There’s no point in wrestling with it. I’d be better off resenting the moon, the stars.

My parents still have a great deal of affection for me, for all of their children. They would empty their veins for any one of us. I have never felt alone, never felt abandoned, not once in my life. Even now, Mother or Papa would go in my place if they could, would bear this burden for me; but it’s impossible. They’re both far too recognizable, like Tati. They’re both watched far too closely by our lurking jailers. And their health—collectively, as if they were a single organism—has collapsed since Papa’s abdication. They could not travel without the care of servants. They are phantoms of their former selves.

But I, I…

I am the only Romanov suited for this undertaking, inconspicuous in looks and durable in temperament. The talent that I lack in needlework is made up for several times over in my proclivity for languages; my English is fluent, and nearly without any trace of a Russian accent. And among my siblings, I am Uncle George’s unabashed favorite, the only one he has never been able to refuse during our yearly visits with the British royal family: not when I asked to stay up late with the adults as they sat around smoking and chuckling and telling stories too coarse for children, not when I invited him to dance with me at Christmas balls, not when I begged for riding lessons on his own children’s prized Windsor Grey horses. King George V is known to be a hard man, but he smiles for me. And he alone has the power to free us.

I reach up to take one of Mother’s cool, pale hands, which have come to rest on my shoulders. She’s staring blankly into her own reflection, caught there like a bear with its foot in a trap of iron jaws. “I’ll make you proud, Mama.” She likes when we call her Mama, as if we were still small and unsteady, as if she could still patch all our wounds. “I’ll tell Uncle George how desperate the situation is. I’ll beseech him to let us take asylum there. He doesn’t understand yet, but he will. And then we’ll all be together again.”

“That Welshman is a ghoul,” she whispers bitterly. She means the British prime minister, the man who has somehow convinced Uncle George that taking us in would irrevocably injure his popularity and thus his own monarchy’s stability. And so negotiations between the Russian Provisional Government and the British Empire regarding what to do with us have broken down. “He’s a demon sent straight from hell.”

This is very colorful language for Mother. “It’ll all be over soon, Mama. I promise. We’ll spend Christmas in London with our cousins, singing and dancing and opening presents, and Alexei can eat his weight in that English sticky toffee pudding he loves so much.”

Now Mother’s yellowed reflection smiles tenderly at me, and she bends down to kiss the crown of my head, smoothing my hair with hands gnarled by time and torment. “When you leave, a piece of me will go with you. I look forward to having it back where it belongs again.”

~~~~~~~~~~

There’s an old greenhouse behind the mansion at the end of a cobblestone path that snakes through a rugged, craggy Siberian garden. It’s rather overgrown now and the glass walls are cracked in spots, and there’s a family of Blakiston’s fish owls building a nest in the eaves, but I still like to read there. I throw a wool sweater over my dress and head out in the afternoons once the sun has warmed it a bit, and I sit in the quiet and the green with a book—written in Russian or English or Latin or French or Italian—and a kerosene lantern until it’s time to retreat back inside for dinner. Everyone knows I do this: Papa, Mother, my sisters (none of whom quite grasp the appeal, although I’ve invited them all to join me at one time or another), little Alexei, the servants, the guards. They rarely even send a man out to supervise me anymore, which is much appreciated, because when they do he complains incessantly about how dull it is. And the greenhouse is where Sir Buchanan’s man comes to collect me.

I’m just pulling open the glass door, my eyes skimming the clouds, an English copy of Tarzan of the Apes under my arm, when a hand closes roughly around my wrist and drags me into a grove of Siberian pea-shrubs. Instinctively, I want to shout, to scratch at him; because no one has ever touched me like that, not even the guards, not even Mother or Papa. No one. Then I remember Mother’s words—there is a man coming for you—and I can feel myself flushing, grinning with exhilaration. My grand adventure is about to begin.

“Follow me to the stables,” my rescuer commands in a British accent that is hushed and very, very deep. He’s young, like Mother said he would be, maybe twenty-five. He has prominent, impatient green eyes and high cheekbones and curls of blond hair escaping from beneath his black knit hat. His fair skin is delicate somehow, and ruddy from the wind. My own skin is on fire.

My adventure is beginning! And my rescuer is handsome!! And he’s holding my hand!!!

Well, perhaps more like clutching my hand, but still.

He hauls me through the shrubs as I struggle to keep up, lifting the hem of my dress over roots and stones and thorns, my skull a useless echo chamber of exclamation points. Inside the stables, there is no company that doesn’t have feathers or four legs. Horses stomp and nicker, pleading for apples or sugar cubes. Crows flap their wings up in the rafters. Open on the straw-strewn, stone floor is a large steamer trunk.

“Get in,” my rescuer instructs me. “There are air holes for you. And no matter what you hear, no matter what you feel, do not make a sound. Do you understand me?”

“Yes,” I manage, smiling at him.

His eyes flick down to where my left hand is grasping Tarzan of the Apes, my knuckles white. “Why do you still have that?!”

“I’ll need something to read on the journey,” I explain, as if this is obvious.

“Jesus Christ.” He shakes his head. “Just get in the trunk.”

I do, curling up against the bottom with my face near one of the air holes the size of a marble. I can feel the weight of the jewels in the fabric of my dress, diamonds and rubies and sapphires and emeralds not entirely unlike my rescuer’s urgent eyes. I can also feel another weight, a different sort of heaviness: a photograph of my family that I tucked into my bodice this morning, just in case today was the day. I clasp Tarzan of the Apes to my chest, my heart racing. I will see my family again soon, I know, and under much happier circumstances.

And I’ll have so many exciting stories to share with them!

My rescuer tosses some thin blankets on top of me—blotting out my vision—and then what sounds like several handfuls of shuffling papers. Then he closes the trunk. His footsteps recede out of the stables. I wait in the muffled sounds of horses and crows and the forthcoming Siberian autumn: chill wind and rustling leaves, the distant cries of migrating geese and the chopping of wood. Soon, the footsteps return, and there are more of them now. I listen to the clicking of hooves and the squeaking of wooden wheels.

“Careful with it,” my rescuer barks at someone in rather clumsy Russian. “Wait…”

To my horror, I hear him lift open the trunk lid. I hold my breath as he paws through the papers above me, feeling the pressure of his hands through the blankets. Finally, after what seems like forever, he grunts in approval and closes the trunk.

He continues, still in Russian: “Yes, I’ve got everything I need, thank you for waiting. I thought I might have forgotten some of my notes. Load it, please.”

And then I understand. He wants the guards to see he has nothing to hide, so that in a day or two when they realize I’m missing no one will say ‘hm, you know what, that handsome blond underling of Sir Buchanan left with a trunk just large enough to smuggle someone out in.’

The trunk rocks as it is lifted off the ground and loaded into the back of what I assume is a carriage. I brace myself against the sides of the trunk with the palms of my hands, gritting my teeth, biting back yelps like a tiny dog’s. Now I know how Anastasia’s Russian Toy feels when she yanks him around like she does, stroking his sable fur and nuzzling his floppy ears and kissing him ceaselessly.

Well, what’s an adventure without some discomfort? I mentally catalogue every detail to tell my family about later, perhaps around a roaring fireplace while sipping mugs of hot chocolate.

Soon the carriage is on the move, bumping along as we leave the mansion property and follow the dirt road that leads out into the wilderness. We travel for quite a while this way, for hours I suspect. Eventually, my rescuer begins whistling a tune I don’t recognize. It must be an English song. Even as the time lurches by uncertainly as I lay in the darkness of the trunk, I never become bored. I’m too busy envisioning all the fun we’re going to share together: sneaking through the countryside, outwitting the agents of the Provisional Government, exchanging stories and songs and the games of our respective childhoods, finally sailing triumphantly up the River Thames to Buckingham Palace. It feels like I could entertain myself forever with the promises of the coming weeks.

At last, the carriage comes to a halt. I hear my rescuer leap down onto the ground and the swishing as his boots displace crisp fallen leaves. He opens the trunk, lifts away the papers and blankets, and offers me his hand. It’s strong, I note, and latticed on top with faint lines like cross-stitching. I take it, beaming, my head swimming, and climb out of the trunk.

Once I’m on the ground—which is a patch of dirt off the road and concealed by rows of Scots pines—I see that we have been travelling not in a roomy carriage with velvet seats and a graceful arc of a roof, but rather a rickety open cart. Secured to the front is an ancient, scruffy-looking mule. I gawk in disbelief. “What is that?”

My rescuer waves to the mule. “That’s Kroshka. She’s excellent company.”

“…Where is the carriage?!”

He glances at the cart, then back at me, puzzled. “You’re looking at it.”

“No, see, this is not a carriage.” I speak very slowly, because my rescuer doesn’t seem all that bright. “This is a cart pulled by a mule. And not even a particularly attractive mule.”

Kroshka flattens her long, droopy ears and huffs. “She didn’t mean that,” Ben coos to the mule, scratching her forelock. “You are a lovely mule. Who’s a lovely mule? That’s right, you are. Yes you are.”

“I need to travel in a carriage,” I inform him, crossing my arms. Mother hates when we do this, but the occasion calls for it.

He laughs at me, and not politely either. He cackles in loud, hysterical peals. “You thought…you thought we were going to sneak you to the railroad station in a…a…a carriage? Like, a royal carriage?! Why don’t you just paint a sign to hang around your neck? ‘Princess on the run, busy committing espionage, please don’t interfere.’ Bloody hell!”

“I’m not a princess.” The thrashing heat in my cheeks is no longer elation. It’s annoyance, it’s indignation. “I’m a grand duchess. I’m ranked higher than the princesses of any other kingdom.”

“It’s a pleasure to meet you. I’m Ben.” He extends his hand, and I take it with a frown. It’s an awkward gesture; I’ve never shaken hands before, only watched from a distance as men did. “Benjamin Hardy.”

I give him my name in return, still frowning. He releases my hand and I re-cross my arms over my chest.

“Well, we definitely can’t call you that,” Ben says. He pulls a hand-rolled cigarette out of his coat pocket, clamps it between his front teeth, and lights it. He exhales a mouthful of smoke into the cold twilight air. “You need a new name.”

“Oh, oh! A new identity, how exciting! Can it be something whimsical? Please? Something elegant and romantic? Maybe…Katerina? Or Valentina? Or Alexandra, like Mother?”

Ben appraises me, taking meditative drags off his cigarette. “Lana,” he decides.

“Lana?!” I’m crushed. “No, absolutely not, I hate that name. It’s so pedestrian. It’s uninspired. It doesn’t even sound like a real name, it sounds like a nickname. It’s not a name for grand adventures. And we had a goat named Lana growing up and she was awful, she ate three of my hats.”

Ben grins. “Lana it is.”

“Can it at least be Svetlana? That’s a real name.”

“No.” He begins unloading the cart: feed for the mule, canteens of water, a small tent to be assembled. He flings a loaf of crusty bread at me and I almost drop it. “Go on, eat.”

“What, for a meal?!”

“Yeah. You’ve had bread before, haven’t you, Your Majesty?”

It’s actually Your Imperial Highness, but I don’t correct him. “No meat? No cheese?” I peer into the trees. “Can’t you chop some wood and build a fire and cook something for us? Some stew? Maybe some rabbit?”

Ben stops setting up camp and stares at me. “What do you think this is, the Waldorf Hotel?”

“The what?”

He points to the bread. “Just eat. We’re not building a fire tonight. We’re still too close to Tobolsk. We aren’t going to advertise our location. We are going to exercise an abundance of caution.”

“Do you think they’ll come after us when they discover I’m missing?” That’s a scary thought, but it’s terribly thrilling too. My heart leaps in my chest. An adventure! What an adventure!

“I don’t think they will,” Ben says. He struggles with the tent. “Someone, probably one of your sisters, is going to go out tomorrow and toss a kerosene lantern into the greenhouse. Then they’ll tell the guards you were inside and must have had an accident while reading and perished in the fire.”

“Oh!” I gasp, stunned. “How grisly.” I picture my family steeped in feigned mourning for me, drifting through the mansion halls in black, dabbing at imaginary tears. How strange. “But I suppose that will give us some advantage.”

“Yes.”

“What is our route, exactly?”

He recites it as the tent begins to take shape: “Tobolsk to the Trans-Siberian Railroad. The railroad to Moscow. Another railroad from Moscow to Saint Petersburg. And then a ship from Saint Petersburg out to the Baltic and south to London.”

I consider Ben as he labors. Perhaps I have judged him (and the mule) too harshly. After all, he is still my rescuer. “I would like to formally thank you for your service, Mr. Benjamin Hardy. For the great personal risk you have assumed in order to extend Christian goodwill to us in our hour of need. On behalf of the entire Romanov family, I thank you.”

He snorts a laugh. This one is incredulous, bitter even. “I’m not doing this for your family.”

Everything sinks in me, like a stone through water. “…You’re not?”

“No.”

“Then why are you doing it?”

“Because Sir Buchanan asked me to,” he says. “Because he’s in poor health and retiring soon, so this will likely be my last chance to repay him for all that he has done for me. And because when I deliver you to King George, I expect to receive a substantial monetary reward. Then I’ll cross the Atlantic, secure employment with the New York Times, and publish an internationally acclaimed article about my experience smuggling the former tsar’s daughter out of wartime Russia. And I’ll live happily ever after.”

“Oh,” I reply softly. It’s all I can think to say. This adventure is not unfolding quite as I had planned.

“There, the tent is ready.” Ben shows me, opening the front flaps.

“Surely we’re not going to sleep in there together!” It’s a small tent. A very small tent.

“Indeed we are. And you’ll be thankful for that when you see how cold it gets out here at night. Sleeping together will keep us warm.”

“It’s indecent,” I say firmly.

Ben stands and rests his hands on his waist. “Look, I’m not going to touch you. That’s my whole job, to get you to London safe and…how would your people put it? Undefiled. You have to still be tradeable stock in the royal marriage market, right? So that’s what I’m going to do. I have no desire nor intention to make any advances upon you. God’s honest truth.”

I glower at him, mistrustful and unsure and suddenly very, very tired. The rush of today’s excitement has bled out and left me empty, drained down to the bones.

Ben adds: “Also, you’ll catch your death out here if you don’t sleep in the tent. And then I definitely won’t get paid.”

“I suppose there’s no use fighting it, in that case.” I plop down on a felled tree trunk and gnaw at my bread morosely, studying the dirt between my shoes as Ben bustles around the campsite: feeding and watering the mule, brushing her down, covering her with a blanket, devouring his own loaf of bread, consulting a map and compass, all the while humming songs I couldn’t name.

I wash myself as best I can with water from a canteen, change into one of the heavy cotton nightgowns that Ben brought for me, and stow my dress safely in the trunk where the jewels and photograph won’t be found. Then I crawl into the tent, hugging the north side while Ben clings to the south. He has a flashlight and is sprawled on his stomach, scribbling down what I presume are the events of the day in a leather-bound notebook. He’s true to his word, because he doesn’t touch me. He doesn’t even look at me.

I squeeze my eyes shut and shiver beneath thin blankets and wish for my mother’s hands, chasing dreams of home as Ben’s pen scratches rivers of black ink into his notebook.

128 notes

·

View notes

Note

For character aesthetics:

Some that could just be fun and chaotic: Hooty and Adrian Pimento

Some that are more... Traditional: Sam Wilson, Raine Whispers, Alexei Shostakov, Jemma Simmons

Don't have to do them all, just options for characters I'd like to see

Thanks for the ask! 💜

I tried making a chaotic one for for Pimento and it was very different than anything I've done before but I gotta say it was fun

And I made a proper one for Raine because I love them sooooo much

Hope you like them!! 💓

14 notes

·

View notes

Note

Good afternoon, Maddy! I hope your day has been wizard so far. For the wip ask game I’m curious to know what MIDDLE AGED POLYCULE OF AWESOMENESS is, and if you have already answered that one, then the mysterious wip by the name of 0 intrigues me lol. Thank you! 💜

Hey Alexei! I did actually answer that one twice already, here and here. People seem to be into it. I should probably finish writing it!

As for the mysterious wip named 0... I wrote chapter 1 and then I decided it needed some context. It's sort of a foreword? Setting up the history of the alternative council (of bastards and bad bitches), the members, and how it formed. Have a snippet!

Their numbers grew quickly, those with ‘concerns’, those who were troubled by the direction the Order was taking.

Some said that they had no choice.

Plo knows there was a choice, but it was taken from them. There were many choices, over the years. Many assumed it was the Senate who took that from them. They were wrong.

But who were any of them to question the directives of the Grandmaster?

They could not meet in person. They would lose all standing in the Order. Their Mastery might be stripped from them, and then who would they be able to save?

They talked over encrypted comms, only Cin knew everyone’s true identity. They plotted and they planned and they mitigated and they tried to help as many people as they could.

Everything changes yet again when Plo was left to die.

Plo burned when a voice, belonging to a man and child both, said "but we're just clones, Sir."

Plo burned with the knowledge that he and his men were left to die as if they were nothing, and that the Order he had given his life to did nothing to save him.

They say that the first cut is often the deepest, but not in Plo’s case.

In Plo’s case it was the final blow that landed hardest. Of all the emotional beatings he endured over the years, it was the knowledge that he was abandoned by the Republic he served, and that the Order he dedicated his life to did nothing to prevent it, that finally tore him from the moorings. Hours upon hours, waiting for a cold and painful death he was certain he could not escape. Neither could he prevent it for the men who looked to him like he was some kind of god, put him on a pedestal he could never hope to live up to, but he had committed himself to his last breath to try.

For them.

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello there, Bailey! How we feeling about Ahsoka Part Five?????? I am so unwell, I loved every bit of it and I was wrecked emotionally 😭😭😭 💜

ALEXEI!!!!! Oh my god you have no idea how big of a smile I get on my face whenever you inbox me, I love it 🥰 And I’m with you, I’m still recovering emotionally from it 😭

Anyhow, I will admit that Ahsoka part 5 is the best episode of the series so far. For once I wasn’t angry or disappointed (I must admit I’m not a hard core Rebels fan so everything up to this point has been frustrating for me) because I was finally seeing the one thing that I think many of us have been dying to see which is Ahsoka reconnecting with Anakin post ROTJ. I absolutely loved the flashbacks and I loved every moment of Ahsoka and Anakin together, I only wished we had more! I love that we got to see teenage Ahsoka with the mind of a much older Ahsoka realizing how distressing her past really was, etc and finally making peace with it. Absolutely beautiful and I was smiling from ear to ear just seeing all the Clone Wars characters again from Rex, to Ahsoka in her Padawan outfit and green lightsaber, to Anakin in his Clone Wars armor. Just amazing and it hits so good when you’ve been watching the Clone Wars since you’ve been a kid! Seeing animated stuff come to live action is truly something.

With that being said, there are a few things I wish we could see (that I doubt we’ll see in this show and that’s fine but I’d love to see it nonetheless). One, I wish Anakin would apologize to Ahsoka for all the trauma he’s inflicted on her as Vader and for all that the Clone Wars have put her through. We saw Obi-Wan apologize to Anakin in the Kenobi show (and let’s be honest here, the only one responsible for Anakin’s fall is well ultimately Anakin), so I’m not sure why that has yet to happen with Ahsoka. She deserves all the apologies but I digress maybe we’ll see it elsewhere because I do believe Anakin and Ahsoka have much to talk about still. Two, I wanna see Barriss! Barriss is such a HUGE part of her past and literally changed the trajectory of her life so why it’s still never discussed is a mystery to me. However again, I think that’s not relevant to this show but when it comes to the story of Ahsoka as a whole, I do believe Barriss needs to return. Like you can’t have a Obi-Wan show without Darth Vader, so why not have Ahsoka make peace/amends with Barriss? Omg can you imagine a live action Clone Wars flashback with Ahsoka AND Barriss?! 😍 Oh I would be in happy tears! ☺️

What did you think my friend? And to everyone else out there, I’d love to hear your thoughts! 😁

#alexei 💜#thank you for the ask! 💚💙#ahsoka spoilers#ahsoka tano#anakin skywalker#barriss offee#the clone wars#star wars

15 notes

·

View notes

Note

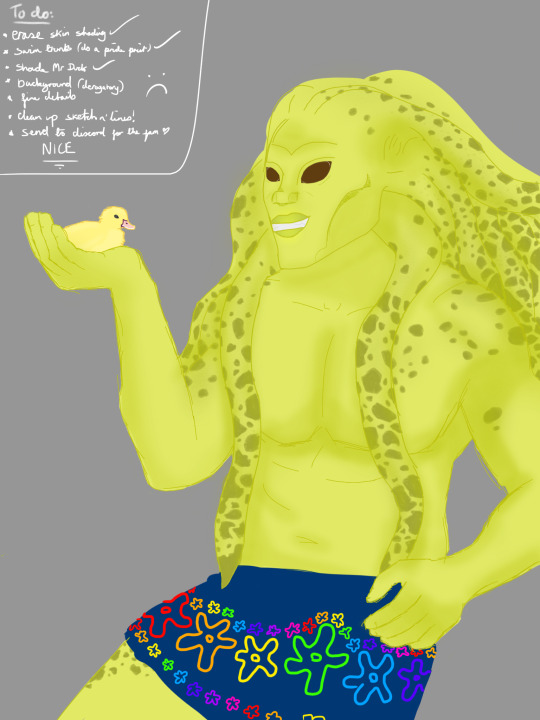

hey alexei! a kit fisto pinup calendar 👀👀👀👀

Hello there, Zip! Feast your eyes on the part of a pinup calendar event a friend and I are doing!

[as always, click for better quality!]

I had way too much fun with his speckles and splotches lol.

Thank you for the ask! 💜

from this ask game!

#kit fisto#alexei draws#he’s for the month of June aka USA pride month#so he has the rainbow SpongeBob shorts lmao#also a duckie for good measure#he isn’t going to eat it that would be yoda#star wars#god i hope the link works I entered it manually for a change

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

We Were Something, Don’t You Think So? [Chapter 3: The Trans-Siberian Railroad]

You are a Russian Grand Duchess in a time of revolution. Ben Hardy is a British government official tasked with smuggling you across Europe. You hate each other.

This is a work of fiction loosely inspired by the events of the Russian Revolution (1917-1923) and the downfall of the Romanov family. Many creative liberties were taken. No offense is meant to any actual people. Thank you for reading! :)

Song inspiration: “the 1” by Taylor Swift.

Chapter warnings: Language, references to historical topics like violence and disease, a very relaxing train ride (just kidding).

Word count: 5.4k.

Link to chapter list (and all my writing): HERE.

Taglist: @im-an-adult-ish @imtheinvisiblequeen @okilover02 @adrenaline-roulette @youngpastafanmug @tensecondvacation @deacyblues @haileymorelikestupid @rogerfuckintaylor @yourlocalmusicalprostitute @someforeigntragedy @mo-whore @mellowyellowfellow @peculiareunoia @mischiefmanaged71

Please let me know if you’d like to be added to the taglist! 💜

In my dreams, I’m always home; and home I’ve found is not a place like the former governor’s mansion in Tobolsk or Alexander Palace or the Winter Palace or the Priory Palace on the shore of the Black Lake, home is not anywhere I could find on a map. Home is not walls or coordinates, staircases or gardens or ballrooms or city squares, stationary structures built by the hands of God or men. Home is wherever my family is.

I dream of Papa bellowing laughter and lifting me as high as he can, back when I was young enough to believe I could pull the cotton-ball clouds from the sky with my reaching fingers; I dream of chasing fireflies with my sisters on summer nights, our bare feet skating over slick grass, shrieking and wheeling and colliding with each other, smiling until my cheeks ache; I dream of sitting with Alexei in the sunshine and reading him stories of pirates and princes and heroes to distract him from his own distinct lack of heroism; I dream of sled rides through powdery snow and my hands nestled in fur mittens and hot chocolate by the fireplace; I dream of Anastasia’s puppy licking my palms; I dream of Tati teaching me what styles of dresses would suit me best, concealing my shortcomings without ever making me ashamed of them; I dream of Papa kissing Mother’s forehead and trying clumsily to fix her hair when it falls out of its pins. Most of all, I dream of Mother standing behind me and impassively brushing my hair on that night when she told me about Ben, that night when I was bubbling over with childish anticipation that swelled and swelled until it burst. I dream of a million reasons I have to endure this journey and the enigmatic, ill-tempered man I share it with.

But here’s what worries me, here’s what gnaws at me when I wake up with a bone-deep pounding around my temples and drag myself out of the tent for another day of typing and reading and gazing off into evergreen nothingness: when I ask my mother to meet my eyes as her reflection flickers in the dying ochre lamplight, she never does.

~~~~~~~~~~

“Come on,” Ben says as he reshuffles the deck of cards. “I’ll show you how to play.”

“I’m busy.” My chin is resting in my palm, my elbow propped on the small wooden table that folds out from beneath the window. The train rumbles along, heading northwest, sailing on metal wings through an ocean of taiga and forests and flat, featureless steppes. We boarded this afternoon and settled into our own compartment off the main corridor: a rectangular little room with a sliding door and two red velvet benches, one for me and one for Ben. Our luggage is tucked away either beneath the seats or above us on metal racks. The mule—what is Ben always calling her, Kristina? Kroshka?—is presumably enjoying a welcome reprieve and all the hay she can eat in one of the stockcars towards the end of the train, behind the passenger carriages. Ben has been occupying himself with card games between slow, leisurely tastes of his hand-rolled cigarettes. He’s never asked if it bothers me, but each time he lights one he cracks the window and lets the vicious cold air flush out the smoke like a letter burned to ash. Meanwhile, I peer doggedly out the window. The view has admittedly gotten worse since the sun dipped below the horizon and blurry, distant stars replaced the clouds.

“Busy staring into the vast Siberian nightscape…?” Ben asks. “I know you can’t possibly see anything.”

“Perhaps I have disturbingly good eyesight.”

“Yes, perhaps you are part owl. Perhaps that is the good breeding you keep referencing.”

I turn my head to glare at him. Ben tosses back a baiting smile, showing his teeth like a wolf.

We’ve barely spoken in days. It’s something like a dance. First I’ll try to make amends, and he’ll pitch back brusque responses until they’re stacked up in a wall between us like bricks; then, inevitably, he’ll extend an olive branch for me to set light to. We can’t seem to get on the same page. This annoys me quite a lot, although it shouldn’t, because within a few weeks I will in all likelihood be courting a crown prince in London and Ben will be boarding an ocean liner to what was once called—with beckoning and cryptic reverence—the New World. We aren’t the sort of people who should keep track of each other after all; I was wrong about that. We are ships passing fleetingly on our voyages to very different shores.

“Seriously,” Ben says. “Let me show you how to play. It’ll make the time go by faster.”

“I know how to play patience,” I tell him, rolling my eyes. Who doesn’t know how to play patience?

Ben stops shuffling. “Really?”

“Of course. Papa taught us that summer we took a cruise to the Isle of Wight.”

“How picturesque. I bet he wishes he’d stayed there.”

I frown and resume my staring out the night-black window. Ben begins a new round of patience, laying queens on kings and jacks on queens and tens on jacks, on and on all the way down the multicolored monarchal food chain.

After a while, Ben says, still meticulously placing his cards: “So, you wanted to end up in Italy or Greece. Although now you might be promoted to future queen consort of the king of the British Empire, only time will tell. Dear simple Maria was likely to marry a German…at least before they became the great menace of our age.”

“Indeed.”

“What about your other sisters?”

I cast him a cagey glance. He raises his eyebrows encouragingly. “I’m not going to entertain you,” I reply, mimicking his voice which is deep and dark and heavy and subterranean and—I hate to admit—rather inescapably alluring.

He pretends to be innocent. He presses one sturdy hand to his heart, and for the second time I notice the faint white lines that crisscross the back of it like a trellis. “I’m entertaining you, Your Majesty! I’m giving you the opportunity to talk about your favorite topic: your perfect, glamorous, beloved, well-bred family.”

I roll my eyes again. Still, this is inarguably better than staring silently out the window all night. “Anastasia is always falling into these whirlwind infatuations with soldiers. Very scandalous, it concerns Mother terribly. She wants to marry someone as lively and fearless as she is. Maybe a prince who served in the war, or a naval officer who’s seen the world, someone athletic and loud who can keep up with her. If she ends up with a solemn intellectual type, I suspect she’ll drive him into a madhouse within six months. Olga likes serious men, mature men. She needs someone steady and wise and caring to lean on. Someone like Papa.”

I look at Ben, daring him to challenge me. He doesn’t. “Go on,” he says nonchalantly.

“Olga used to want to marry a Russian, because she was so dreadfully afraid of having to be away from Mother and Papa. She’s a very nervous person, and the idea of leaving them, having to learn a new language, a new religion, adjusting to a new climate and culture all alone…it’s not something that would be easy for her. I can honestly say it might kill her, and if it didn’t she would need regular nips of laudanum to keep her ulcers at bay. But now that Mother and Papa will be in Britain, Olga will want to stay there too. Maybe she could marry one of Uncle George’s younger sons, or some superfluous prince from a large family somewhere who would be willing to settle in Britain with her. And Tati…” I pause, considering. “Actually, I can’t recall Tatiana ever having much interest in men of any variety. Which is ironic.”

“Ironic how?” Ben asks.

“Well, because she’s the most beautiful one and therefore the greatest prize.”

Ben’s brow furrows, as if he takes issue with this. Then he recovers. “Do you miss them much?”

“Constantly.” My voice comes out in a quiver, which I had not anticipated. We sit in awkward quiet for a moment, avoiding each other’s eyes.

“Solitaire,” Ben pivots, meaning the cards. He’s shuffling to begin a new game. “That’s what the Americans call it.”

“Why America?” I reply with genuine curiosity. “Of all the places you could go, why do you want to start over there?”

“It’s the land of opportunity, isn’t that what everybody says?” He lays out his cards like a fortune teller; and I only know what a fortune teller is because I’ve read about them, not because I ever would have been permitted to see one. God, no. Mother would have a stroke. “Anyone can make it big there. You don’t need a title. You don’t need good breeding. They’ve never had kings or queens or tsars. And perhaps wealth sometimes forms its own sort of monarchy, but that’s unavoidable I suppose, isn’t it? I want to be a part of a country like that. Somewhere young and ambitious. And once I’m set up there, I’ll bring over my mum and my siblings, and they’ll be able to start over too.” He smirks to himself. “Also, I doubt I’d be able to find any Western European newspaper willing to publish an article so blatantly critical of royals.”

“That’s how you’d characterize your article?” I inquire tersely.

His hands—strong, rough, scarred—pause as they dole out the playing cards. His green eyes flick up at me. “Would you rather me lie to you? Because I can do that. I’d rather not, but I can.”

“No.” I peer out the murky void of the window, my jaw rigid. “The truth is fine.”

Someone—their shadow towering on the other side of the cloudy glass panel—raps on the sliding door with their fist, and Ben and I both leap in our seats. Ben’s hand flies to where I know he keeps the pistol on his belt.

“Uzhin! Desyat minut!” a gruff voice calls through the door, and then the shadow departs to continue down the corridor. Just an announcement from the train conductor. Thank God.

“I don’t think I caught that,” Ben says shakily, settling back into the red velvet bench, running his fingers through his blond hair. It’s very odd to see him afraid. It makes him seem so normal, so young, as if he isn’t some fortified, brick-wall type, daunting, almost-stranger but perhaps a boy who I’ve grown up with, a son of a family friend or distant relative, a boy who sits on the edge of the pier to fish with me and my sisters and kicks his feet lazily as he dips them into the cool, clear, sparking lake water.

“They’re summoning us for dinner. It’ll be ready in ten minutes.”

“Oh, well that’s good news! Our first hot meal in days. It’s like Christmas. It’s like Christmas and New Years and Easter all rolled into one.” He points at me. I’m wearing—grudgingly, without any enthusiasm whatsoever—another outfit of his creation: a nondescript cream blouse, a long brown skirt belted at my waist, ugly boots of course. My hair is shoved up into a rather tattered red plaid hat. “They probably won’t allow hats in the dining car. You should braid your hair or something. Keep it simple, anonymous, middle-class. You look too much like your portraits with your hair down. I don’t think anyone here would recognize you, but I’m not interested in taking any unnecessary risks. Are you?”

“No, I’m not either.” I touch my hat self-consciously. “But…I…I don’t…I’m not sure…”

“It either needs to be tied back or cut off, your choice.”

I cover my face with my hands, mortified, defeated. This is more ammunition for Ben’s ridicule. There’s always more, it never ends. “I don’t know how.”

“You don’t know how to what?”

I peek at him through my fingers. “To braid my hair.”

He blinks at me. “Are you serious?”

“Someone else always did it for me! Mother, or Tati, or Olga, or one of the servants…”

Ben groans out a tremendous sigh. “Right. Come over here.”

“What? Why?”

He holds up his own hands, as if they are an explanation.

“You know how to braid a woman’s hair?” A bolt of something I don’t quite recognize hits me in the gut: below my heart, above the cradle of my hips. Scandal? Jealously? Who has he practiced on? Who has he touched?

“My sister taught me,” Ben explains. And he might be faintly amused, but I can’t tell for sure. “Many years ago. Back when I was a boy.”

“Oh.” That isn’t so bad. I yank off the hat and shake out my hair, which is long and wild and not as thoroughly combed as I’d prefer and probably has leaves and sticks and God knows what in it. I scoot around the small table and cross over to Ben’s bench. I sit down beside him, tense and jittery, wringing my hands in my lap, not knowing where to look. Ben turns my face away from him and buries his hands in my hair, separating it into three thick strands. It’s the first time he’s ever touched me kindly. There’s a sensation like someone dragging their fingertips up the length of my spine; goosebumps climb my arms like ivy. Ben doesn’t seem to notice. He hums as he works, a song I don’t know. “So, your sister conscripted you to arrange her hair?” I ask to fill the thin space between us, willing myself to stop panicking like an idiot.

“Yes. Louise. She was four years older than me, and then there was another gap between me and all the little kids, so she didn’t have the luxury of a sister to help her with things like that. Mum was always working, always. She spent twelve hours a day at the textile mill. We barely saw her. So I learned how to braid hair and place pins, and in return Louise learned how to tie ties and shine shoes and shave burgeoning beards.” I can hear the smile in his voice; not a teasing smile, not a sarcastic smile, but a real one. A soft one.

“You had a lot of siblings, then,” I say, prompting him to continue, not wanting him to lose that tenderness that barely sounds like him at all.

“Had.” I can feel his knuckles against back of my neck as he plaits my hair into a braid. More goosebumps, more blood crashing in my cheeks. Then he lists them off: “Louise, Franklin, Luther, Willis, Cecil, Leo, Opal, Kathryn, August.”

“What did your father do?”

“Fuck prostitutes and drink Mum’s wages away, apparently.”

I stare at the wall with huge eyes and regret asking.

“He disappeared before August was born. I’m not sure if he ran off with some other woman or died in a ditch somewhere, and honestly I don’t really care either way. He was no help when he was around. Louise and I did everything. Cooked, cleaned, stomped the rats to death, looked after the little kids. And then we got jobs just like Mum, as soon as Frankie was old enough to take over at home. Louise worked in a bakery. That’s where she met her husband James. I found a man at the local newspaper office who was willing to take me in as an apprentice. Mum was thrilled, she was over the moon. One less mouth to feed, right?”

“Right,” I agree, suddenly feeling dazed and heavy and very, very sad.

Ben finishes my braid and ties it off with a rubber band fished from his pants pocket. “Leo, Opal, Kathryn, and August are still at home. Frankie is serving in the British Army. He writes me letters when he can. He was at Verdun, and he survived that. Now he’s in Passchendaele. I’ve heard it’s hell on earth, that men drown in craters of mud and gore. I dream about it sometimes, but in my dreams Frankie’s never a man. He’s always a kid again, he’s eight or nine years old and he’s asking me to teach him how to load his rifle and fix his bayonet. Luther won’t have to enlist, thank God. He’s got a club foot, and in any case he’s already in school for dentistry. He’s the clever one. Willis and Cecil caught pneumonia when they were just babies. They died within a week of each other. It was unimaginable, it was like someone snuffed out the sun like a candle. And then we lost Louise when I was eighteen, as I told you.”

“In childbirth,” I reply quietly, remembering.

“That’s right.”

I turn around to look him in the eyes. They’re just as green as I remember, but they’re something else too, something new. They’re gentle. “I’m so sorry for your losses, Ben. I would take it all back if I could.”

“It’s not death that bothers me. Death comes for us all, it’s the most natural thing in the world. But the inequity of the wheel of fortune is one hell of a blade.” He stands and rolls open the sliding door. “Now, let’s go to dinner.”

The dining car has cramped little tables set up along either side of a narrow red aisle, and no amount of crisp white tablecloths or miniature chandeliers or tiny vases of roses can make it elegant. Nonetheless, we devour borscht, shashlik, pelmeni swimming in butter and sour cream, warm rolls of rye bread, and pastila until my stomach feels like it will rupture and spill out onto the stained, worn carpet. This is the food I have grown up with—a rather prosaic version of it, anyway—and it brings me memories of countless meals with Papa and Mother and my sisters and brother around massive tables that never run dry. For the first time in my life, I am acutely aware of the fact that I have never lost any of them. I am fortunate; it is rare even in aristocratic families to have not a single child claimed by accident or illness. It rushes over me like a wave. I miss them, desperately, consumingly. My hands ache to hold them again.

“You alright?” Ben asks, sipping his red wine, narrowing his eyes at me. He’s allowed us only one glass each, which I consider to be very despotic of him. Even Mother lets us older girls have two or three on special occasions. My reality is barely dulled at all, and I could use something to smooth over those edges tonight.

Before I can nod a reply, I overhear the conversation at the table next to us. There is a middle-aged woman in a plain maroon dress shoveling pierogis into her mouth and telling her husband between bites, in an unsophisticated sort of Russian: “I heard some horrible rumor about the Romanovs.”

“Oh? What’s that?” her husband responds, equally engrossed in his bowl of ukha.

“I heard that one of the daughters died in a freak accident. In a fire of some sort. One of the middle ones. The guards weren’t watching her and a lantern tipped over or something and she went up in flames, the poor thing. There was nothing left. The whole family is devastated, just utterly aghast. They don’t even have bones to bury.”

Ben shoots me a furtive wink. The plan must have worked; the Provisional Government thinks I’m dead, and if I’m dead then I certainly can’t be escaping though the countryside on a highly illegal secret mission, now can I? I smile back at Ben. No one will know I’m gone. Not until I’ve secured my family’s release and we’re safe and united again, and then it won’t matter anyway.

Across the aisle, the husband says bitterly: “Good. Let that bastard Nicholas have a taste of his own medicine. Blood for blood.”

My stomach drops like a brick. My skin goes clammy. My smile evaporates.

“Boris!” the wife chastises, still gobbling her pierogis. “For Christ’s sake. The girls had nothing to do with any of that. Certainly we can agree that the children are innocent, aren’t they?”

“Sure. And the people’s children are innocent too. Our children are innocent. But that wouldn’t have stopped Nicholas from ordering them to be gunned down on Bloody Sunday. It didn’t stop him from sending them off to be butchered in the Great War, a war we had no business getting involved in. And it didn’t stop him from enjoying his palaces and cruises and holidays while we scraped by on moldy bread crusts and unanswered prayers. So let him suffer some, at long last. Let them all suffer. Let them have a bite of the misery we’ve been feasting on for centuries.”

“Mmm,” the wife concurs contently around a mouthful of pierogis.

“Better times are ahead of us,” the husband insists with a spirited wave of his spoon. “The tsar is a prisoner. Soon he’ll be headless in an unmarked grave where he belongs. Perhaps a day will even come when there are no kings or princes left anywhere in the world. And we can show them the way. We can be a beacon for all nations. Because now Russia can truly be great.”

“I’ll drink to that!” a young man at a nearby table shouts, and cheers and toasts spread through the dining car, contagious.

I stare down at the white tablecloth with my guts twisted in knots, my lips trembling, my hands cold and clasped together so forcefully they throb. I count the wayward drops of red wine I’ve spilled to distract myself. I know I need to behave normally, I know I can’t allow their venom to poison me; but it’s already working its black magic in my blood.

I want to go home. I don’t want to do this anymore. I don’t want a grand adventure, I don’t want to be here with these strangers who pretend they know us. I just want to go home.

Suddenly, Ben reaches across the table and takes my hands in his: smooth in rough, icy in warm. He might not understand every word of what the other passengers said, but his Russian is good enough to catch most of it. He doesn’t speak, he just looks at me, and smiles tightly beneath sympathetic eyes as if to say: I know it’s hard. I’m sorry. I’m here. And I find myself feeling just the tiniest bit better. I do, I do.

We leave the dining car not long after. Back in our own compartment, Ben closes the sliding door as I crawl onto my velvet bench and huddle against the window, laying the side of my face against the cold glass as Siberia races by, gazing unseeingly out into endless dark oblivion. The corridor outside is silent and still. Most of the passengers are still at dinner. Ben waits patiently for me to say something. He waits for a long time. And, at last, I do.

“I don’t know how to reconcile the kind, compassionate, indescribably gentle father I knew with this monster that other people say he is. I can’t understand their rage. I can’t even fathom it.”

Ben’s voice is low and calm. Wise, even. “It is entirely possible that Nicholas II is an excellent husband and father, and yet simultaneously an abject failure of a tsar. And that’s the problem with monarchies, isn’t it? People end up in positions of power they have no acumen for. And their mistakes are measured not in lost profit or customers but human lives. Innumerable lives.”

I raise my head from the glass and study him. “You are opposed to all monarchies, then? To monarchy as an institution?”

“I believe they are unjust and ineffective by nature. I don’t mean to offend you, but that is my educated opinion.”

“You do offend me. You offend me down to the bones I’m built of.”

“That’s tragic.” He’s sardonic now. He searches through his pockets and sighs irritably. “I lost my lighter. I’m going to go see if I can buy one off somebody in one of the other carriages. Stay here, don’t speak to anyone, don’t go anywhere. Alright?”

“Sure,” I mumble, resting my face against the window again, refusing to look at him.

Once Ben is gone, I decide to find my copy of Tarzan of the Apes to read until I can fall asleep. I tug the steamer trunk out from underneath Ben’s bench (with some difficulty), lift open the lid, and paw through loose papers and heaps of blankets until I find the book. I set it on the table. But as I close the trunk lid, I glimpse my dress that I stowed there, the one with the jewels sewn inside of it, the one from home. I pull the dress halfway out of the trunk and slip my fingers into the bodice to find the photograph of my family I left there for safekeeping. Their black-and-white faces are somber and regal and unchanging. I ghost my thumb across them, as if I can erase their expressions and make them show me new ones, make them chuckle and wave at me. But this photograph isn’t a window. It’s just a piece of paper and plastic.

“I miss you,” I whisper in Russian to Papa and Mother and my sisters and Alexei. To nobody.

The compartment door slides open, and Ben fills up the doorway. “What is that?” he asks.

“Nothing.” I clutch the photograph face-down to my chest.

He lunges, wrestles it away from me, soaks it in with furious, glinting eyes. “I can’t believe you,” he hisses.

“Ben, it’s just—”

He storms out of our compartment and down the corridor in the opposite direction from the dining car, headed for the door at the end that leads out onto an open-air platform with a metal railing. I can hear him ripping the photograph once, twice, again and again.

“Ben, wait!”

I tear after Ben and follow him out onto the platform, slamming the carriage door shut behind me. The wind is frigid and ferocious as the train barrels through the night; the sharp metallic scent of snow is in the air.

Wasn’t it just summer? Wasn’t I just home where I was supposed to be? What happened? What in God’s name happened?

The platform rocks and jolts beneath my boots, the wheels screaming against the tracks. Amber sparks fly as metal grinds metal. I grip the railing for dear life. The next carriage is close enough to reach out and touch, bolted to ours by a coupling. No one has lowered the walkway that can be used to connect them. Ben hurls a flurry of scraps—all that’s left of the photograph of my family—into the night air; and then they’re gone.

“What’s wrong with you?!” I scream over the deafening noise of the train and the wind and the world that has somehow become so disorienting, ceaselessly cruel.

“What’s wrong with me?! I asked if you had anything I didn’t know about and you lied, you lied right to my face!”

“It was just a photograph, it was the only one I had, and now it’s gone—”

“You don’t fucking get it!” Ben rages. The wind ravages his hair and rubs his cheeks an angry, bloody pink. “Don’t you know what’s going to happen to you if someone figures out who you are?!”

“It’s not like you’d care!” I shout back, tears searing in my eyes like cold fire. “You don’t care about me! All you care about is the money you’re going to get, and going to America, and scribbling in your stupid goddamn notebook—!”

“Hey, princess—”

“I’m a grand duchess!”

“You’re nothing, don’t you understand that?!” he roars. “You’re nothing, because nobody wants you! Your own fucking country doesn’t want you! That notebook is going to be worth more than you someday! You’re just a useless relic of a dying, archaic institution and I’m the only thing standing between you and a hundred million people who want to rip you apart with their bare hands, so you better learn how to listen to me before you get us both killed!”

I flee back inside the train carriage, down the empty corridor, into our compartment. I slam the sliding door shut and collapse onto the floor, sobbing violently into my sleeves.

I don’t want to be here. I don’t want to be here. I want to go home.

But home is wherever my family is. And I can only save them if I make it to London.

I can’t do this. I just can’t.

But I have no choice.

It feels like forever passes before Ben comes back, but it must be no more than an hour. My eyes are swollen and painful. My body is completely spent. I’m curled up on my bench under one of the thin blankets from the trunk, shivering, trying to imagine I’m sleeping next to Mother or Tati or Alexei or anyone who doesn’t wish I was dead. I hear the door slide open when Ben enters.

“I’m sorry,” he says. “I shouldn’t have yelled at you. I shouldn’t have said those things to you. You don’t know any better, you don’t really grasp what’s at stake here. You don’t understand the risks. Nothing horrible has ever happened to you.”

I reply without looking at him. My throat is raw, my voice gravelly. “My great-grandfather was murdered by anarchist assassins. They used a bomb. His own children carried him—pieces of him, anyway—into the Winter Palace where he died. Seven years later, my grandfather was travelling in the Imperial train when it derailed and the roof collapsed. He held the debris up on his own shoulders, like Atlas, so that his children could escape alive. He never recovered from the physical trauma. He developed a disease of the kidneys and died in his wife’s arms. That same year, Papa married Mother. He knew they needed to produce an heir. Not for his own sake, nor for Mother’s, no, they loved us girls plenty, they wanted us, even if the nation greeted each new daughter with escalating disappointment. When Olga was born, Papa said: ‘I am glad that our child is a girl. Had it been a boy he would have belonged to the people; being a girl she belongs to us.’ Still, Russia needed an heir. Mother had babies, one after the other, until she was nearly destroyed from childbearing. And at last, she had Alexei. But even then it wasn’t enough, because he’s a hemophiliac. It’s a royal disease, it lies dormant in the bloodlines until it strikes, until a previously perfect newborn baby suddenly starts hemorrhaging from their navel. Alexei is going to die young. That’s a certainty. And he knows it, too. He talks about heaven all the time. He asks about if they have puppies there, if they have snow, if they have sticky toffee pudding, if he’ll be able to look down and see us from the clouds. Have you ever met a twelve-year-old who talks so much about heaven? It’s because he knows his life is as fragile as a spider’s thread, and every bump and bruise that cripples him with excruciating pain for weeks is a reminder of that. Sometimes heaven sounds better than what he has to look forward to here on earth. Two years ago, Papa and Mother decided their children needed to learn about the true price of warfare, so Olga and Tati were sent to work with the Red Cross treating wounded soldiers. They stayed there until Tati caught dysentery and Olga had a nervous breakdown. She still has nightmares about it, wakes up moaning about men with no eyes, no legs. And now, now…now we’ve been dethroned, and imprisoned, and soon we’ll be refugees in a strange land, and all of that sacrifice through the generations was for nothing, and my parents’ bodies and spirits are ruined, and I’m stuck here with you. So don’t say we’re unfamiliar with horror. It’s not the same as what you’ve been through, I know that. I’m not saying that it is. But suffering is no stranger to us. The Romanov demons may wear different faces than yours, but that doesn’t mean we don’t have any.”

I drag the blanket over my head and wait for a dreamless sleep to numb me to the bones.

70 notes

·

View notes