#roger has aged like 20 years in the last six months and who can blame him.

Text

there he is... that's my boy

#ds liveblogging.#970.#MY FAVORITE NIECE. MARRIED. TO A PHOTOGRAPHER. THAT WEARS BLUE JEANS!#(and also was involved in a plot to bring some evil subterranean eldritch entities to power. or smth)#he would have flown home :'''') <3#ohhh his silver hairrr. .....#roger has aged like 20 years in the last six months and who can blame him.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Atlanta “Child Murders”

The curious and controversial string of deaths that sparked a two-year reign of terror in Atlanta, Georgia, has been labeled “child murders,” even though a suspect ultimately blamed for 23 of 30 “official” homicides was finally convicted only in deaths of two adult ex-convicts. Today, nearly two decades after that suspect’s arrest, the case remains, in many minds, an unsolved mystery.

Investigation of the case began, officially, on July 28, 1979. That afternoon, a woman hunting empty cans and bottles in Atlanta stumbled on a pair of corpses, carelessly concealed in roadside undergrowth. One victim, shot with a .22 caliber weapon, was identified as 14-year-old Edward Smith, reported missing on July 21. The other was 13-year-old Alfred Evans, last seen alive on July 25; the coroner ascribed his death to “probably” asphyxiation. Both dead boys, like all of those to come, were African-American.

On September 4, Milton Harvey, age 14, vanished during a neighborhood bike ride. His body was recovered three weeks later, but the cause of his death remains officially “unknown.” Yusef Bell, a 9 year old, was last seen alive when his mother sent him to the store on October 21. Found dead in an abandoned school November 8, he had been manually strangled by a powerful assailant.

Angel Lenair, age 12, was the first recognized victim of 1980. Reported missing on March 4, she was found six days later, tied to a tree with her hands bound behind her. The first female victim, she had been sexually abused and strangled; someone else’s panties were extracted from her throat.

On March 11, Jeffrey Mathis vanished on an errand to the store. Eleven months would pass before recovery of his skeletal remains, advanced decomposition ruling out a declaration on the cause of death. On May 18, 14-year-old Eric Middlebrooks left home after receiving a telephone call from persons unknown. Found the next day, his death was blamed on head injuries, inflicted with a blunt instrument.

The terror escalated that summer. On June 9, Christopher Richardson, 12, vanished en route to a neighborhood swimming pool. Latonya Wilson was abducted from her home on June 22, the night before her seventh birthday, bringing federal agents into the case. The following day, 10-year-old Aaron Wyche was reported missing by his family. Searchers found his body on June 24, lying beneath a railroad trestle, his neck broken. Originally dubbed an accident, Aaron’s death was subsequently added to the growing list of dead and missing blacks.

Anthony Carter, age 9, disappeared while playing near his home on June 6, 1980; recovered the following day, he was dead from multiple stab wounds. Earl Terrell joined the list on July 30, when he vanished from a public swimming pool. Skeletal remains discovered on January 9th, 1981, would yield no clues about the cause of death.

Next up on the list was 12-year-old Clifford Jones, snatched off the street and strangled on August 20. With the recovery of his body in October, homicide detectives interviewed five witnesses who named his killer as a white man, later jailed in 1981 on charges of rape and sodomy. Those witnesses provide details of the crime consistent with the placement and condition of the victim’s body, but detectives chose to ignore their sworn statements, listing Jones with victims of the “unknown” murderer.

Darren Glass, an 11-year-old, vanished near his home on September 14, 1980. Never found, he joins the list primarily because authorities don’t know what else to do with his case. October’s victim was Charles Stephens, reported missing on the ninth and recovered the next day, his life extinguished by asphyxiation. Capping off the month, authorities discovered skeletal remains of Latonya Wilson on October 28, but they could not determine how she died.

On November 1, nine-year-old Aaron Jackson’s disappearance was reported to police by frantic parents. The boy was found on November 2, another victim of asphyxiation. Patrick Rogers, 15, followed on November 10. His pitiful remains, skull crushed by heavy blows, were not unearthed until February 1981.

Two days later after New Year’s, the elusive slayer picked off Lubie Geter, strangling the 14-year-old and dumping his body where it would not be found until February 5. Terry Pue, 15, went missing on January 22 and was found the next day, strangled with a cord or piece of rope. This time, detectives said that special chemicals enabled them to lift the suspect’s fingerprints from Terry’s corpse. Unfortunately, they were not on file with any law enforcement agency in the United States.

Patrick Baltazar, age 12, disappeared on February 6. His body was found a week later, marked by ligature strangulation, and the skeletal remains of Jeffrey Mathis were discovered nearby. a 13-year-old, Curtis Walker, was strangled on February 19 and found the same day. Joseph Bell, 16, was asphyxiated on March 2. Timothy Hill, On March 11, was recorded as a drowning victim.

On March 30, Atlanta police added their first adult victim on the list of murdered children. He was Larry Rogers, 20, linked with younger victims by the fact he had been asphyxiated. No cause of death was determined for a second adult victim, 21-year-old Eddie Duncan, but he made it on the list anyway, when his body was found on March 31. On April 1, ex-convict Michael Mcintosh, age 24, was added to the roster on grounds that he, too, had been asphyxiated.

By April 1981, it seemed apparent that the “child murders” case was getting out of hand. Community critics denounced the official victims list as incomplete and arbitrary, citing cases like January 1891 murder of Faye Yearby to prove their point. Like “official” victim Angel Lenair, Yearby was bound to a tree by her killer, hands behind her back; she had been stabbed to death, like four acknowledged victims on the list. Despite those similarities, police rejected Yearby’s case on the grounds that (a) she was a female-as were Wilson and Lenair-and (b) that she was “too old” at age 22, although the last acknowledged victim had been 23. Author Dave Dettlinger, examining police malfeasance in the case, suggests that 63 potential “pattern” victims were capriciously omitted from the “official” roster, 25 of them after a suspect’s arrest supposedly ended the killing.

In April 1981, FBI spokesman declared that several of the crimes were “substantially solved,” outraging blacks with suggestions that some of the dead had been slain by their own parents. While that storm was raging, Roy Innis, leader of the Congress of Racial Equality, went public with the story of a female witness who described the murders as the actions of a cult involved with drugs, pornograpthy, and Satanism. Innis led searchers to an apparent ritual site, complete with large inverted crosses, his witness passed two polygraph examinations, but by that time police had focused their attention on another suspect, narrowing their scrutiny to the exclusion of all other possibilities.

On April 21, Jimmy Payne, a 21-year-old ex-convict, was reported missing in Atlanta. Six days later, when his body was discovered, death was publicly attributed to suffocation, and his name was added to the list of murdered “children.” William Barrett, 17, went missing May 11; he was found the next day, another victim of asphyxiation.

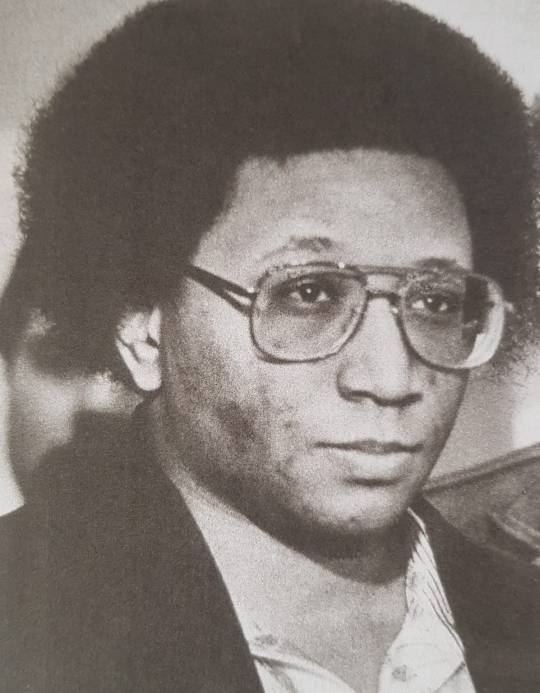

Several bodies had, by now been pulled from local rivers, and police were staking out the waterways by night. In the predawn hours of May 22, a rookie officer stationed under a bridge on the Chattahoochee River reported hearing “a splash” in the water nearby. Above him, a car rumbled past, and officers manning the bridge were alerted. Police and FBI agents halted a vehicle driven by Wayne Bertram Williams, a black man, and spent two hours grilling him and searching his car, before they let him go. On May 24, the corpse of Nathaniel Cater, a 27-year-old convicted felon, was fished out of the river downstream. Authorities put two and two together and focused their probe on Wayne Williams.

From the start, he made a most unlikely suspect. The only child of two Atlanta schoolteachers, Williams still lived with his parents at age 23. A college dropout, he cherished ambitions of earning fame and fortune as a music promoter. In younger days, he had constructed a working radio station in the basement of the family home.

On June 21, Williams was arrested and charged with the murder of Nathaniel Cater, despite testimony from four witnesses who reported seeing Carter alive on May 22 and 23, after the infamous “splash.” On July 17, Williams was indicted for killing two adults-Cater and Payne-while newspapers trumpeted the capture of Atlanta’s “child killer.”

At his trail, beginning in December 1981, the prosecution painted Williams as a violent homosexual and bigot, so disgusted with his own race that he hoped to wipe out future generations by killing black children before they could breed. One witness testified that he saw Williams holding hands with Nathaniel Cater on May 21, a few hours before the “splash”. Another, 15 years old, told the court that Williams had paid him two dollars for the privilege of fondling his genitals. Along the way, authorities announced the addition of a final victim, 28-year-old John Porter, to the list of victims.

Defense attorneys tried to balance the scales with testimony from a woman who admitted to having “normal sex” with Williams, but the prosecution won a crucial point when the presiding judge admitted testimony on 10 other deaths from the “child murders” list, designed to prove a pattern in the slayings. One of those admitted was the case of Terry Pue, but neither ide had anything to say about the fingerprints allegedly recovered from his corpse in January 1981.

The most impressive evidence of guilt was offered by a team of scientific experts, dealing with assorted hairs and fibers found on certain victims. testimony indicated that some fibers from a brand of carpet found inside the Williams home (and many other homes, as well) had been identified on several bodies. Further, victims Middlebrooks, Wyche, Cater, Terrell, Jones and Stephens all supposedly bore fibers from the trunk liner of a 1979 Ford automobile owned by the Williams family. The clothes of victim Stephans also allegedly yielded fibers from a second car-a 1970 Chevrolet-owned by Wayne’s parents. Curiously, jurors were not informed of multiple eyewitness testimony naming a different suspect in the Jones case, nor were they advised of a critical gap in the prosecution’s fiber evidence.

Specifically, Wayne Williams had no access to the vehicles in question at the times when three of the six “fiber” victims were killed. Wayne’s father took the Ford in for repairs at 9:00 A.M on July 30, 1980, nearly five hours before Earl Terrell vanished that afternoon. Terrell was long dead before Williams got the car back on August 7, and it was returned to the shop the next morning (August 8), still refusing to start. A new estimate on repair costs were so expensive that Wayne’s father refused to pay, and the family never again had access to the car. Meanwhile, Clifford Jones was kidnapped on August 20 and Charles Stephens on October 9, 1980. The defendant’s family did not purchase the 1970 Chevrolet in question until October 21, 12 days after Stephen’s death.

On February 27, 1982, Wayne Williams was convicted on two counts of murder and sentenced to a double term of life imprisonment, Two days later, the Atlanta “child murders” task force officially disbanded, announcing that 23 of 30 “List” cases were considered solved with his conviction, even though no charges had been filed. The other seven cases, still open, reverted to the normal homicide detail and remain unsolved to this day.

In November 1985, a new team of lawyers uncovered once-classified documents from an investigation of the Ku Klux Klan, conducted during 1980 and ‘81 by the Georgia Bureau of Investigation. A spy inside the Klan told BGI agents that Klansmen were “killing the children” in Atlanta, hoping to provoke a race war. One Klansman in particular, Charles Sanders, allegedly boasted of murdering “List” victim Lubie Geter, following a personal altercation. Geter reportedly struck Sander’s car with a go-cart, prompting Klansman to tell his friend, “I’m gonna kill him. I’m gonna choke the black bastard to death.” (Geter was, in fact, strangled, some three months after the incident.) In early 1981, the same informant told GBI agents that “after twenty black-child killings, they, the Klan, were going to start killing black women.” Perhaps coincidentally, police records note the unsolved murders of numerous black women in Atlanta in 1998-82, with most of the victims strangled. On July 10, 1998, Butts County Superior Court Judge Hal Craig rejected the latest appeal for a new trial in William’s case, based on suppression of critical evidence 15 years earlier. Judge Craig denied yet another new-trial motion on June 15, 2000.

#atlanta child murders#african american children#wayne williams#child deaths#child murders#tw child death#death#murder#serial killer#such a long read#sad post#atlanta murders#so many innocent victims#tcc blog#tcc blogger#tcc community#tcc love#tcc post#tcc account#tcc writer#tcc#my serial killer addiction#new content#ku klux klan#innocent chilren#true crime#real crime#reblog

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nick Kyrgios Holds His Temper, and Australia Holds Its Breath

MELBOURNE, Australia — Nick Kyrgios was not willing to be hunted.

During the opening points of his Australian Open match against the wily veteran Gilles Simon — known for his ability to lure opponents into deadly traps with deceiving softballs and sudden bursts — Kyrgios did not take the bait.

Instead, on a hazy Thursday night, the mercurial Australian played the start of this second-round match in a way that belied his reputation. He was controlled, contained, comfortable, and mature.

The result, early on: perfection. It was Simon who made the errors, Simon who became the prey.

Kyrgios, 24, tall, rangy and slope-shoulderedtook the first set in a mere 27 minutes, 6-2.

At that moment, as Melbourne Arena trembled with cheers, it was hard not to jump ahead and wonder about how this tournament and this year could unfold for Nick Kyrgios.

With his nation struggling to contain wildfires that continue to char the countryside and smudge the air, could this be the Grand Slam tournament in which Kyrgios, tennis’s most combustible talent, tamps his emotions and finally makes a deep run, a semifinal or better?

You could feel that kind of excitement in the crowd, in their willingness to back their prodigal son, their eagerness to believe he could do anything over the course of this two-week stretch.

It felt as if every one of the 10,000 fans was behind him. It was a carnival. As the second set began, just as they’d done from the start, they chanted his name, serenaded him, waved the Australian flag, and sprang to their feet to cheer his 130-mile-an-hour aces.

Everyone knew how he’d crashed ignobly in the last half of 2019, behaving in tournaments with such lack of control and disdain for the sport that he ended up in counseling after being fined a total of $138,000 and put on probation for six months. Everyone knew, just as well, of the time he’d taken off from the tour grind, time enough to reflect, and of his leading role in the efforts to help victims of the terrible bushfires.

After Kyrgios said that the fires had given him a reason to play “for something more” than himself, a primary narrative during the first few days of the Australian Open was that the tough times and catastrophic blazes had given him wisdom.

Above the din, from the corner where I sat 20 rows above the sea blue court, I could hear a man two seats away speak excitedly to a friend. “It’s the new Kyrgios,” he said. “New and improved.”

Was it?

Tantalizing, Yet Tempestuous

There is nobody in professional tennis quite like Kyrgios.

Nobody with his range of magnetic talent and emotion, so often unmoored.

Nobody with his churlish disregard for the old (and often stuffy) conventions of pro tennis. Who among the top players tries to drill a ball into the gut of a class act like Rafael Nadal, and then laughs it off? Kyrgios, that’s who.

He does not walk gentlemanly to the court. He struts, preens, postures — his style a constant nod to the cool, hip African-American vibe of his favorite sport, basketball, and the N.B.A.

Largely because of that vibe, there is nobody, at least among the top men’s players, who so easily taps into the youthful fans that tennis is desperate to attract as its future lifeblood.

There is nobody harder to figure out, harder to pin down.

Is he the man of the people who has recently led the movement among players to donate their winnings and raise money for victims of the local fires?

Is he the warmhearted guy who, last summer, reeled off joyous games of table tennis with ball retrievers just minutes before defeating Daniil Medvedev in the final of an ATP Tour stop in Washington?

Is he the human tornado who touched down in Cincinnati last summer, smashing rackets into graphite bits, derisively calling an Irish umpire a “potato,” and spitting the umpire’s way?

Is he the wayward soul who has played large chunks of matches by simply going through the motions, essentially quitting?

Or is Kyrgios the game competitor who, in 2014, at age 19, announced himself to the tennis world by beating Nadal on his way to the Wimbledon quarterfinals?

He has beaten not only Nadal, but also Roger Federer and Novak Djokovic. Few can say that. But his ranking of 26 remains mired in the broad no-man’s land that exists just outside the top 10. Despite constant talk that he was capable of stepping to the fore and upending the Big 3 hierarchy in men’s tennis, his last trip as far as a quarterfinal in a major was in 2015.

It’s hard to watch Kyrgios — with his wide smile, his style, his penchant for pulling off trick shots, his fierce serve and searing forehand, his oh-so obvious talent — and not fall for him.

And it is hard, at the same time, not to be left wanting and disappointed.

Game. Set. Match.

Kyrgios seemed utterly in control for a very long swath against the 35-year-old Simon.

But then the finish line drew near. Just a few games from the clean sweep of a three-set win, Kyrgios’s lesser self emerged. Soon, he was missing easy shots. Suddenly, he radiated tightness.

He had already chirped at the umpire when admonished for delaying play, and mockingly mimicked Nadal’s time wasting tic of tugging on his shorts and tussling with his hair. The message was clear, and brought to mind the pleadings of a child: Nadal gets away with it — why can’t I?

Now, Kyrgios looked and sounded equally petulant as he began heaping a barrage of barbs at friends and advisers near the court, as if they were to blame for his shoddy play down the stretch.

The general look among the faces in the overwhelmingly Australian crowd became one of stricken, nervous worry. They want to believe in Kyrgios the way they believe in the women’s top seed, another of their own, Ashleigh Barty. The difference is they can count on Barty. They know what to expect: unwavering effort, quiet humility. They don’t know what they’ll get with Kyrgios. They had seen him self destruct plenty of times before.

“He’s on the edge now, of something not good happening,” said one of the commentators on Australian TV. The commentator was John McEnroe, who of course is as expert as any at diagnosing the fraying emotions of a player on the verge of losing control.

Sure enough, the wheels wobbled all the way off. Simon rose up and snatched the third set. What seemed like a sure thing was now a fight.

The match marched forward, and as the games went on in the fourth set, Kyrgios’s mood only got worse. He would describe himself after the match as being close to going to entering a “dark place.”

But something interesting happened along the way. Watching closely, you could see him change. He stopped looking up at the stands, put an end to the salty barbs. His sloping posture straightened. His face grew focused, serious, intent. He began playing with just enough control to be dangerous again.

He dug deep, centered himself, and found his footing.

Soon enough he edged ahead, the front-runner once more, just in time.

Match point.

The crowd roared, insisting he end it. He tossed the ball toward the pitch-dark sky, struck it with as much force and clarity as any ball he had struck all night.

Ace.

Game, set, match, Kyrgios: 6-2, 6-4, 4-6, 7-5.

Nothing is ever certain when he takes the court. Maybe he will flame out in the next round. Maybe he will keep going, perhaps all the way to the last weekend. Nadal potentially awaits in the fourth round. What a contrast. The ultimate professional versus the ultimate question mark. There does not appear to be much love between them. It would be one of the most anticipated matches of the tournament.

The potential of that was enough on this raucous evening to savor the moment, to fall for the full range of the quixotic and talented Kyrgios as he found his way to a spirit-lifting win.

from WordPress https://mastcomm.com/sport/nick-kyrgios-holds-his-temper-and-australia-holds-its-breath/

0 notes

Photo

A Driver’s License Can be Revoked for the Elderly, but Artistic License? Never.

She was due for retirement. Try telling her that.

Louise Fili, the designer behind logos for Tiffany & Co., Good Housekeeping, Paperless Post, and Sarabeth’s was, as always, a font of great ideas. “I think you should be focusing on the great octogenarians out there — Seymour Chwast, George Lois, Ed Sorel, R.O. Blechman, Bob Gill, Henrietta Condak, Sara Giovanitti…there are so many,” she said in her graceful decline to be a part of this story. “I will be happy to participate when you update the article in, say, 20 years.” Fili is 65, the touchstone — albeit arbitrary — retirement age. Time will tell. But that’s an offer she can make confidently.

Artists exist in careers without reply-all emails about the break room fridge, or dress codes, or — and most importantly — without punch clocks. They are timeless talents.

In 1972, at 90 years old, Pablo Picasso painted “Facing Death,” a self-portrait; he died the next year, having painted since 1891, when he was 9. I.M. Pei, the architect, is set to turn 100 this year as he works on 28 projects in six countries; he’s been working since his designs first caught fire in 1949. “I know how lucky I am,” Roger Angell, then 93, wrote in The New Yorker in 2014, “and secretly tap wood, greet the day, and grab a sneaky pleasure from my survival at long odds.” He has been contributing to the august magazine since 1944, most recently about the Chicago Cubs’ World Series victory, their 108-year championship drought being one of the few things in this world that predate him.

Now 94, Norman Lear is rebooting his 1975 sitcom classic One Day at a Time for Netflix, a Latina spin anchored by Rita Moreno, the 85-year-old EGOT superstar, who plays a 73-year-old sexualized grandmother. Hayao Miyazaki, the anime demigod, has came out of retirement to turn a 12-minute short film titled into a feature-length project, as you do at 76 years old.

There is an element to vocation beyond Western raison d’être, the French “reason for being” mired in Enlightenment sensibilities, that approaches the looser Japanese concept of ikigai, which can be translated as “a reason to get up in the morning” but was best described in a 1990 article in the Japanese business publication The Nikkei (formerly The Nihon Kaizai Shinbun) as “the process of allowing the self’s possibilities to bloom.” That process is itself a craft. Sorry, Tim Ferriss, there is no Four-Hour Ikigai.

These are all-work-and-all-play lives lived in the livelihood of humanity’s lifeblood: art, creativity, design. “To create is to live twice,” Albert Camus famously mused. While that wisdom may have been a gesture at the metaphysical immortality of fame and legacy and the stuff of lifetime achievement awards, it can also be taken literally as the doubling — or more — of creative professional lives as compared to the workaday world’s corporate drones, to say nothing of the relatively fleeting glories afforded professional athletes, dancers, and porn stars. A driver’s license can be revoked for the elderly, but artistic license? Never.

“To create is to live twice.”

“It’s not about doing something well over and over. It’s about doing something new over and over,” said Ivan Chermayeff, the 84-year-old graphic designer behind iconic logos for Barneys, Mobil, National Geographic, NBC, and the Smithsonian. “People who want to retire want to do other things. Travel. Plant a garden. I don’t. I’ve been doing those things every day my whole life. It’s a good racket,” he added from his office, with Wally, his Australian labradoodle barking in agreement at his feet.

Ivan Chermayeff, image courtesy of Chermayeff.

Chermayeff noted the physical costs of activity outweigh the mental and emotional costs of lethargy. “I have a bad knee but thankfully it has very little bearing on graphic design abilities,” he said.

“I was a professor, a teacher. I just stayed in offices. It was awful,” said the prolific architect Daniel Libeskind, 70. “I have lived in reverse, my active period coming after the introspective, reflective period. With architecture, I fell into a new dimension. I made my first building when I was 52! Instead of withering me, time gave me a sense of flowering, of growing. To be honest, I don’t think of aging. There is an immortality to being creative. You are like God, who is the poetic symbol of creation, the poetry of creativity. As your work continues, you become younger. You discover youthfulness — braver, bolder, more confident, more adventurous. You discover possibilities.”

Daniel Libeskind at the Roca London Gallery. Photo courtesy of Libeskind.

Not that it’s easy. “You have to make a conscious decision early on that the suburbs and its finished basements aren’t for you. I had an illegal apartment for ten years, 1971 to 1981, $50 a month in a garret at 55th and 7th. I paid another $50 a month for a work space. So I was free,” said Larry Hama, 67, the comics superhero who single-handedly revived the series G.I. Joe and Wolverine, among other feats. “I’ve had years without any work. But I still did what I wanted. The only difference is I got paid during the working years, which was nice, but it wasn’t the reason I worked.”

There are, of course, life hacks to this Fountain of Youth.

For Libeskind, it is thermodynamics: A body in motion stays in motion. “I’ve lived in 18 cities,” he said. “Sometimes without knowing the language. Sometimes without having a job. Warsaw, Berlin, New York, São Paolo, Milan. They contribute so much energy to your mind. I’ve never been one for the beach or solitary walks in the woods.”

“As your work continues, you become younger. You discover youthfulness — braver, bolder, more confident, more adventurous.”

For Jonas Mekas, 94, the filmmaker who founded Film Culture magazine in 1954 and what would become the Anthology Film Archives in the 1960s, it is cultivating prickliness — not antisocial, just countersocial. “I was an urchin, a sea urchin, covered in spikes. Society could not swallow me. I did not fall into its holes. And those of us who escape enjoy a camaraderie. We don’t have to talk or get together. But we show other people what life is. We lure them into life with the things we make,” he said.

“You want what? That I go to the beach? I hate the beach. For one thing, it’s hard to get an espresso at the beach. And what is there? Ugly, grotesque people indulging their laziness while they cook and bake in the sun like slugs. That is joy? That is freedom? I don’t blame them for retiring at 65 because they have lived as robots in mechanical, menial, tedious tasks. They deserve a few years trying to feel human after all of that. They took my humanity and my youth in the camps. I was 17 in Lithuania and the next day, on the other end of the war, I was 27 in Brooklyn. I will never lose my youth again. I’ve worked too hard all my life to be this young,” Mekas says.

For abstract artist Carmen Herrera, as she puts it, “my bus was slow in coming.” She first sold her paintings in 2004, when she was 89. But what a ride it has been since then. Last year, at 101 years old, she had her first museum retrospective, at the Whitney Museum of American Art. Her secret is her stealthiness. “I was liberated by being ignored,” she said. “I was free to do as I wish.” Not to suggest too much whimsy; asked her morning routine, she laid out her breakfast: “Cafe con leche, toast, butter and jam, orange juice, and work.” And work. As if it were a chewy bagel or bowl of porridge. She devours it. And it nourishes her. But at her own pace. She takes all week to read the Sunday New York Times, favoring the alchemy of its stories over the checklist of the task. Asked what advice she would give youngsters — y’know, people with mere double-digit ages — she spoke in her native Cuban Spanish: “Patience, darling, patience.”

Carmen Herrera in her New York studio. Image courtesy of Herrera.

For Hama, it was saying yes. “Whenever the train got into the station, I got on board. And wherever it took me, when I got there I didn’t want the guided tour,” he said. “I was in an elevator in 1974 and a woman asked me if I was an actor. I said no and she asked ‘Do you want to be?’ And later that day I was in an off-Broadway production of Moby Dick put together by the starlet Jean Sullivan. I was on M*A*S*H and Saturday Night Live. They needed guys and I raised my hand.”

How do you retire from saying yes? “I can’t imagine retiring, and I have a great imagination,” he said. “If I go to the beach and try that, after an hour or so I just feel inert. Life is for action. Wander. Wonder. Surprise yourself. That’s the only adventure. You can’t win the lottery if you don’t buy a ticket. I’ve done, I think, 239 issues of G.I. Joe and never ended with a coming attractions of the next issue because I never knew. I don’t know what’s on page three until I’m halfway through writing page two. And I guess I’ve lived my life like that, too,” Hama says.

“Life is for action. Wander. Wonder. Surprise yourself. That’s the only adventure.”

When he was a child, Mekas’ home would be visited by an old man who climbed his roof and stood on his head on the chimney. He was 100 years old and his upside-downness had a profound impact on Mekas.

“You’re asking all the wrong questions. You’re asking why I’m active at 94. But why are people living like they are already dead at 60? Or 40? Even 30?” he said. “I am not the abnormal one. I am normal. I am alive. This is life. They are the abnormal ones. They just don’t see it because they happen to be the majority, sadly. They believe in patterns that suck out their energy — ads and transactions and labels and paperwork and technology that all tell them they are not enough, that they are behind, that they are lacking. What is retirement or even vacation except a stupid trap built to justify the first trap of this draining existence? I reject it! Instead I choose art! Art and the avant garde is the difference between making a life and mirroring one.”

0 notes