#rentier class

Text

page 538 - birdie with a short beak.

I am so mad. And I'm pretty sure that other blogger is to blame.

I think.

#maximizing renewable resource rent#renewable#renewable resource#rent#rentier#rentier class#class war#value of sustainable yield#economic rent with biomass#biomass#harvest#harvesting#government#economics#economy#economis#the economist#bird#birdphotography#birds#birds captures#birds adored#ego#rivalry

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

1. Feudalist Logics

“Neo-reactionaries apart, virtually everyone who uses the term finds neo-feudalism deplorable, a throwback to an oppressive past. But what exactly is wrong with it? Here, as with Tolstoy’s unhappy families, those unhappy with neo-feudalism are all unhappy in their own way. The differences derive in part from the contested nature of the term ‘feudalism’ itself. Is it an economic system, to be evaluated in terms of its productivity and openness to innovation? Or is it a socio-political system, to be assessed in terms of who exercises power within it, how, and over whom? This is hardly a new debate—both medievalists and Marxists know it well—but these definitional ambiguities have crossed over into the nascent discussions about neo- and techno-feudalism.

For Marxists, the term ‘feudalism’ refers, above all, to a mode of production. The concept thus defines an economic logic through which surplus produced by the peasants—the linchpin of the feudal economy—is appropriated by the landlords. Of course, viewing feudalism as a mode of production does not mean that political and cultural factors did not matter. Not all peasants, lands and landlords were alike; all sorts of multi-level hierarchies and intricate distinctions—rooted in provenance, tradition, status, force—shaped interactions not only between classes but also within them. Feudalism’s own conditions of possibility were as complex as those of the capitalist regimes that succeeded it. For example, the peculiar nature of sovereignty under feudalism—as Perry Anderson emphasized, it was ‘parcelized’ among landholders, rather than concentrated at the top—left a major imprint. However, for all these nuances, important strands within the Marxist tradition have concentrated their efforts on deciphering the economic logic of feudalism, as a key to elucidating that of its successor regime, capitalism.

In its simplest version, feudal economic logic went something like this. The peasants possessed their own means of production—tools and livestock; access to common land—and so enjoyed some autonomy from the landlords in producing their subsistence. The feudal lords, facing few incentives to raise the peasants’ productivity, didn’t intervene much in the production process. The surplus produced by the peasants was openly appropriated from them by the landlords, most commonly by appeal to tradition or to law, enforced by the lord through the threat—and often the application—of violence. There was no confusion about the nature of such surplus extraction: the peasants were under no illusion about their freedom. Their autonomy in matters of production may have been considerable; their autonomy in general, however, was strictly circumscribed.

As a result, many Marxists—we can skip the internal disputes at this stage—held that, under feudalism, the means of surplus extraction are extra-economic, being largely political in nature; goods are expropriated under the threat of violence. Under capitalism, in contrast, the means of surplus extraction are entirely economic: nominally free agents are obliged to sell their labour power in order to survive in a cash economy, in which they no longer possess the means of subsistence—yet the highly exploitative nature of this ‘voluntary’ labour contract remains largely invisible. Thus, as we move from feudalism to capitalism, politically enabled expropriation gives way to economically enabled exploitation. The distinction between the extra-economic and the economic—one of many such dichotomies—suggests that, as a category in Marxist thought, ‘feudalism’ is intelligible only when examined through the prism of capitalism, commonly imagined as its more progressive, rational and innovation-friendly successor. And innovative it is: in relying solely on economic means of surplus extraction, it need not dirty its hands more than is strictly necessary; the ‘invisible Leviathan’ of the capitalist system does the rest.

For most non-Marxist historians, in contrast, feudalism was not a backward mode of production but a backward socio-political system, marked by bouts of arbitrary violence and the proliferation of personal dependencies and ties of allegiance, commonly justified on the most tenuous religious and cultural grounds. It was a system in which untamed private powers ruled supreme. As a result, it’s customary within this rather diverse intellectual tradition to contrast feudalism not to capitalism but to the law-respecting and law-enforcing bourgeois state. To be a feudal subject is to live a precarious life in fear of arbitrary private power; to tremble at rules that one had no role in creating and to have no possibility of appealing one’s guilty verdict. For Marxists, the opposite of the feudal subject, the peasant, is the fully proletarianized worker of the capitalist enterprise; for the non-Marxists, it’s the citizen of the modern bourgeois state, enjoying a plethora of guaranteed democratic rights.

Regardless of the paradigm, it should in theory be possible to identify the key features of the feudal system and examine whether they might be reoccurring today. For example, if we treat feudalism as an economic system, one such feature could be the parasitic existence of the ruling class, which gets to enjoy a luxurious lifestyle at the expense and misery of the class (or classes) it dominates. If we treat it as a socio-political system, it might be the privatization of power formerly vested in the state and its dispersion through opaque and non-accountable institutions. In other words, if we manage to associate feudalism with a certain dynamic, and if we can observe the recurrence of that dynamic in our own post-feudal present, we should at least be able to speak of the ‘re-feudalization’ of society, even if a full-blown ‘neo-feudalism’ is nowhere on the horizon. It’s a weaker claim, but it carries greater analytical clarity.

....

3. ‘Accumulation by Dispossession’?

... In the past decade, there have been many intriguing attempts to advance the argument that exploitation and expropriation have been—and still are—mutually constitutive. Two stand out in particular: the German sociologist Klaus Dörre’s theorization of the capitalist ‘land grab’, drawing on Rosa Luxemburg’s Landnahme and Nancy Fraser’s related work on the deep-rooted structural connection between exploitation and expropriation, with the latter creating—and constantly recreating—conditions of possibility for the existence of the former. Many of the methodological discussions unfolding on the left today—about the best ways to narrate capitalism in relation to climate or race or colonialism—still reflect the unresolved issues of the Brenner–Wallerstein debate.

A lot of this recent work builds on David Harvey’s influential concept of ‘accumulation by dispossession’, introduced in his 2003 book The New Imperialism. Harvey coined this term as he was unsatisfied with the qualifier ‘primitive’; he, as many others before him, saw accumulation as ongoing. Summarizing some of the recent scholarship on the issue in The New Imperialism, Harvey noted that ‘primitive accumulation, in short, entails expropriation and co-optation of pre-existing cultural and social achievements as well as confrontation and supersession.’ This was hardly the Brennerian account of ‘primitive accumulation’ as the process of breaking up the feudal ‘merger’ between the factors of production; Brenner’s capitalists were not ‘co-opting’ anything—they were ridding themselves, with some systemic help, of unproductive social practices and relations.

Alas, Harvey’s account of ‘accumulation by dispossession’, while promising so much, delivered very little: in the end, it became even more ambiguous than Marx’s account of ‘primitive accumulation’. If Harvey’s initial formulation was to be believed, the poor capitalists of the early 2000s could barely make money at all without dispossessing someone of something: Ponzi schemes, the collapse of Enron, raiding pension funds, the rise of biopiracy, the commodification of nature, the privatization of state assets, the destruction of the welfare state, the exploitation of creativity by the music industry—these are just some of the examples used to illustrate the concept in The New Imperialism. Seeing it everywhere, Harvey unsurprisingly concluded that ‘accumulation by dispossession’ had become the ‘dominant’ form of accumulation in the new era. How could it be otherwise, when every activity that did not directly involve the exploitation of labour—and even some that did—seemed to be automatically included in this category?

In 2006, Brenner wrote a mixed review of The New Imperialism, chiding Harvey for his ‘extraordinarily expansive (and counterproductive) definition of accumulation by dispossession’, inflating the concept to an extent where it was no longer useful. He confessed that he found Harvey’s conclusion about the dominance of dispossession over capitalist accumulation ‘incomprehensible’. But was it? It would indeed be ‘incomprehensible’ if one assumed that we were still living in capitalism, which, at least to the Brenner of 2006, seemed unquestionable. But, if capitalism really was over and some other feudalism-like system was upon us, that statement would make more sense.

In later works, Harvey muddied the waters some more, making ‘accumulation by dispossession’ the main driver of neoliberalism, which he defined as a political project, redistributive rather than generative in outlook, that aimed to transfer wealth and income from the rest of the population to the upper classes within nations or from the poor countries to richer ones internationally. Here, there was no space for the Brenner-friendly interpretation of ‘accumulation by dispossession’ as something aimed at creating conditions for innovation—hence production and generation—at all. Without stating so explicitly, Harvey quietly joined the other side of the debate, while adding a host of other mechanisms of surplus transfer—rent extraction around intellectual property, for example—to those initially described by Wallerstein. Anyone steeped in the orthodox, Brennerian take on ‘primitive accumulation’ would immediately take issue with Harvey’s basic chronology of events; even for Wallerstein and his followers, trade-based primitive accumulation preceded and accompanied capitalist accumulation, it did not replace or overtake it.

Since Harvey’s initial formulation of the concept in the early 2000s, ‘accumulation by dispossession’ has been embraced by many scholars, not least those in the Global South, who use it to theorize new forms of rentier extractivism whereby corporations flex their political muscles to acquire land and mineral resources. There’s a certain logic to all of this: first dispossession, via extra-economic means; then rentierization, by leveraging property rights—including those over intellectual products—which shifts the operation back into the economic realm. Being in that realm, however, is no guarantee that we are in normal capitalism. Save for mining and agriculture, where some productive or at least extractive activities do need to be organized, the capitalist class appears to be simply reaping rents and enjoying a life of luxury, much like the landlords of the feudal era. ‘If everyone tries to live off rents and nobody invests in making anything,’ wrote Harvey in 2014, ‘then plainly capitalism is headed towards a crisis.’ But what kind of crisis? Harvey himself doesn’t flirt with neo-feudalist imagery—at least he hasn’t yet—but his analysis of contemporary capitalism makes it easy to draw the obvious conclusion: this is capitalism in name only; its actual economic logic is much closer to the feudal one. What other lesson could one draw from Harvey’s claim, as early as 2003, that redistributive dispossession had overtaken generative exploitation?

Cognitive multitudes

A similar message could be found in the work of those Italian and French theorists who prophesize the emergence of ‘cognitive capitalism’—yet another capitalism in name only. Inspired by the work of Toni Negri and other Italian operaistas, these thinkers—Carlo Vercellone and Yann Moulier-Boutang are among the best known—insist that the multitude, the successor to the working class, armed with the latest information technologies, is finally capable of autonomous existence. On this account, capital can’t—and doesn’t want to—control production, much of which now happens in a highly intellectualized manner beyond the gates of the Taylorist factory, which itself is no more (at least in Italy and France). Today’s capitalists simply establish control over intellectual property rights, while trying to limit what the unruly multitude can do with its newfound communicative freedoms. These are not the innovation-obsessed capitalists of the Fordist era; these are lazy rentiers, entirely parasitic on the creativity of the masses. Working from these premises, it’s easy to think that some kind of techno-feudalism is already upon us: if the members of the multitude are truly the ones doing all the work and are even using their own means of production, in the sense of computers and open-source software, then to speak of capitalism seems like a cruel joke.

One aspect of the ‘cognitive capitalism’ perspective has a particular bearing on contemporary debates about the logic—feudal or capitalist?—of today’s digital economy. Drawing on the Italian workerist tradition, Vercellone and his co-thinkers have hypothesized the obsolescence of the managerial class, supposedly defeated by the creativity of the multitude. Bosses may have had a role under Fordism, but modern cognitive workers need them no more. This is taken as a sign that the move from formal to real subsumption—i.e. from the mere incorporation of labour into capitalist relations to its structural transformation according to capitalist imperatives—has now been reversed, with capitalism moving backwards. Feudalism becomes visible, even if these theorists hope that communism will arrive first.

As George Caffentzis has pointed out in a perceptive critique, the possible irrelevance of managers to the organization of the productive process is in itself no proof that the revenues booked by capitalist enterprises come in the form of rent, rather than profit. After all, there are plenty of capitalist firms that are almost fully automated, with neither managers nor workers. Should they therefore be seen as rentiers? The answer of the cognitive-capitalism theorists seems to be ‘yes’: such firms must be parasitic on something, perhaps squeezing a patent portfolio, a real-estate holding or the General Intellect of humanity as such. Take, for example, an automated car wash. Is there a reason to believe that it is not capitalist simply because it does not employ anyone, and thus generates no surplus value? Or because, in order to automate the car wash, a few algorithms—undoubtedly using dead labour and congealed knowledge of previous generations, and maybe even a patent or two—were used?

Probably not. In line with Marx’s own writings on the equalization of profits across differently automated firms and industries, the car wash is simply absorbing the surplus value generated elsewhere in the economy. To present these automated firms as ‘rentiers’ rather than as proper capitalists is to strip Marx’s account of capitalist competition of its substance; it is precisely the constant drive to automate—to cut costs and boost profitability—which accounts for the constant flow of capital towards more productive firms. Workerism, the intellectual cornerstone of the cognitive-capitalism theory, remains trapped in the epistemology of the human worker: if no workers are present, the Italian theorists assume that no capitalist production takes place and that rentierism rules the day. In such accounts, ‘capitalism’ may live on as a label, but we are already somewhere in the No Man’s Land between feudalism and the putting-out system (Vercellone himself has noted the similarity).

4. Digital Fortunes

Theorists of techno-feudalism share the cognitive-capitalism assumption that something in the nature of information and data networks pushes the digital economy in the direction of the feudal logic of rent and dispossession, rather than the capitalist logic of profit and exploitation. What is it? An obvious explanation points to the tremendous growth of intellectual-property rights and the peculiar power relations that they institute. As early as 1995, Peter Drahos, an Australian legal scholar, warned about the looming ‘information feudalism’. Imagining the world of 2015 in the first half of his article—he got virtually everything right—Drahos argued in the second half that extending patents to abstract objects, such as algorithms, would result in the proliferation of private and arbitrary power. (Similarly Supiot’s critique of feudalization claims that intellectual-property rights allowed for the formal separation of the ownership of objects from their control—a throwback to the past.)

Another feature of the digital economy that seems to chime with feudal models—especially the Marxian, mode-of-production variety—is the strange, almost surreptitious way in which users of digital services are made to part with their data. As we all know, the use of digital artefacts produces data traces, some of which are then aggregated—potentially yielding insights than can help to refine existing services, finetune machine-learning models and train artificial intelligence, or be used to analyse and predict our behaviour, fuelling the online market for behavioural advertising. Humans are key to activating the data-gathering processes that envelop these digital objects. Without us, many of the initial data traces would never be produced. These days, we are creating them constantly—not just when we open our browsers, use gaming apps or search online, but in myriad ways in our workplaces, cars, homes— even our smart toilets.

What exactly is going on here, capitalism-wise? One could argue, with the cognitive-capitalism theorists, that users are actually workers, with technology platforms living off our ‘free digital labour’; without our interaction with all these digital objects, there wouldn’t be much digital advertising to sell and the making of artificial-intelligence products would become more expensive. Another view, of which Shoshana Zuboff is the leading exponent, compares users’ lives to the pristine lands of a faraway, non-capitalist country, threatened by the extractivist operations of the digital giants. Condemned to ‘digital dispossession’, as she puts it in The Age of Surveillance Capitalism (2018), ‘we are the native peoples whose tacit claims to self-determination have vanished from the maps of our own experience.’ For clarity of exposition, this is not exactly Marx’s c-m-c. But the sentiment is clear.

Zuboff distances herself from theories of ‘digital labour’—in fact, from consideration of labour tout court. Accordingly, she doesn’t have much to say about exploitation; surveillance capitalists, it seems, don’t do much of this. Instead, she draws on Harvey’s ‘accumulation by dispossession’, presenting it as an ongoing process. Zuboff discusses at length Google’s elaborate procedures for the extraction and expropriation of user data. The term ‘dispossession’ appears almost a hundred times in the book, often in original combinations with other terms—‘dispossession cycle’, ‘behavioural dispossession’, ‘dispossession of human experience’, the ‘dispossession industry’ and ‘unilateral surplus dispossession’. For all its high-pitched language about users as ‘native peoples’, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism leaves little doubt that ‘dispossession’ is accomplished through modern technology and on an industrial scale—which supposedly makes it look capitalist. For Zuboff, however, ‘capitalism’ is something that companies ‘commit’, like a faux pas or a crime. If the formulation sounds strange, it is an accurate rendering of how she understands this particular -ism: by and large, ‘capitalism’ is what happens to humans when companies do stuff.

Reading Zuboff’s vivid descriptions of the symbolic and emotional violence, deception and expropriation that propel the Google-driven digital economy, one might wonder why she dubs it ‘surveillance capitalism’, rather than ‘surveillance feudalism’. On the very first page of the book she writes of ‘a parasitic economic logic’—not that far from Lenin’s famous analysis of the rentier profits underpinning ‘imperialist parasitism’. The Age of Surveillance Capitalism flirts with the ‘feudalist’ formulation in a couple of places, without ever fully embracing it. On closer examination, however, the economic system she describes is neither capitalism nor feudalism. It is what one might call, for lack of a better term, user-ism—in direct analogy to Italian workerism. The Italians could not imagine how non-rentier, labour-light capitalist firms could make capitalist profits merely by attracting surplus value produced elsewhere; as a result, they ended up introducing strained concepts like ‘free digital labour’. Zuboff, in turn, cannot imagine that human experience, congealed in data that is appropriated from the user at the point of contact with digital artefacts, is not the principal driver behind Google’s exorbitant profits.

User-ism posits that, from Google to Facebook, the bulk of the profits of these firms derives from their expropriation of user data. But does it? Could there be other explanations? If they exist, Zuboff doesn’t consider them, marshalling only evidence that will confirm her existing thesis: users give Google data; Google uses the data to personalize advertising and build data-intensive cloud services (an important part of Google’s business, of which Zuboff says very little). Therefore, it must be the user-data-advertising connection that accounts for Google’s windfall profits. What else could it be, given that she discusses no other aspects of Google’s operations?

...

5. Capitalism, Still?

Until recently, most of the serious literature on neo- and techno-feudalism from the left approached it—like Neckel and Supiot—as a socio-political rather than an economic system. The publication of Techno-féodalisme by the French economist Cédric Durand represents the most sustained attempt so far at a serious consideration of the economic logics involved. Durand earned his name with Fictitious Capital (2014), an insightful analysis of modern finance. Contrary to assumptions by some on the left, Durand argued, financial activities do not have to be ‘predatory’: in a well-functioning system, they could help to advance capitalist production by facilitating advance financing, for example. However, from the 1970s onwards, this accumulation-friendly feature of modern finance—Durand dubs it simply, ‘innovation’—was overtaken by two more sinister dynamics. The first, rooted in the logic of dispossession as theorized by Harvey, involved powerful financial institutions leveraging their connections to the state to redirect more public money towards themselves; here we are back to the ‘extra-economic’ means of extracting or, more accurately, redistributing value, backed by the close links between Wall Street and Washington. The second dynamic, rooted in the logic of parasitism theorized by Lenin in his analysis of imperialism, referred to the various payments—interest, dividends, management fees—that non-financial corporations have to render to financial firms, which stand completely outside the production process.

On Durand’s telling, the bailout measures following the 2008 financial crisis turbocharged the dynamics of dispossession and parasitism, suppressing those of innovation. ‘Is this still capitalism?’, he wondered, in the closing pages of Fictitious Capital. ‘This system’s death-agony has been heralded a thousand times. But now it may well have begun—almost as if by accident.’ This would not be the first ‘almost accidental’ transition to a new economic regime; Brenner once described the transition from feudalism to capitalism in England as ‘the unintended consequence of feudal actors pursuing feudal goals in feudal ways.’ So the idea that financiers, by taking the easy way out—dedicating themselves solely to politically organized upward redistribution and rent-supported parasitism—could accelerate the transition to a post-capitalist regime was not only highly intriguing but also theoretically plausible.

In his new book, Techno-féodalisme, Durand retains his focus on the looming end of capitalism but assigns the task of burying it to the tech firms. Fictitious Capital had already examined the so-called profit-investment puzzle: when capitalism is functioning well, higher profits should mean higher investments; the whole point of being a capitalist is to never stand still. And yet, from roughly the mid-1990s on, there was no such link: profits increased in the advanced-capitalist economies—with ups and downs—but investment stagnated or declined. Plenty of explanations have been adduced to explain this, including the maximization of shareholder value, growing monopolization or the toxic effects of ever-accelerating financialization. Durand did not come up with new causal factors. Instead, he chose to argue that ‘the enigma of profits without accumulation is, at least in part, an artificial one’—a statistical illusion, created by our inability to grasp the effects of globalization.

On the one hand, some firms had found ways of making more money without additional investment. Globalization and digitization allowed top firms in the Global North—think Walmart—to leverage their positions at the apex of global commodity chains in order to extract lower prices for final or intermediate goods from the actors lower down the chain. On the other hand, when capitalists from the Global North were making investments, these increasingly went to the Global South. Thus, looking at profit-investment dynamics through the lens of individual countries of the Global North—the us, for example—doesn’t tell us much. One needed a global view to see how exactly profits map onto investments.

With Techno-féodalisme, Durand joins the growing chorus who explain the profit-investment puzzle by emphasizing the role of intellectual-property rights and intangibles—including data holdings—in allowing the giant us firms to squeeze tremendous profits from their supply chains by focusing on those aspects that have the highest margins. To an extent, it’s an elaboration of Durand’s argument from 2014, but with much greater attention paid to the actual operations of global supply chains and the role that intellectual-property rights play in the distribution of power within them. For some of the firms he examines, the enigma of profits without investment is no longer artificial, as it was in Fictitious Capital: they really don’t invest much, at home or abroad, regardless of their profit levels. They either hand back their earnings to shareholders in dividends or buy back their own stock; some, like Apple, do both.

Techno-féodalisme argues that the rise of intangibles, usually concentrated at the most profitable points of the global value chain, led to the emergence of four new types of rent. Two of them—legal intellectual-property rents and natural-monopoly rents—look familiar: the first refers to the rents derived from patents, copyrights and trademarks; the second to rents derived from the ability of Walmart-like firms to integrate the whole chain and to furnish infrastructures needed within it. The other two—dynamic-innovation rents and intangibles-differential rents—sound more complex. But they, too, capture relatively clear and distinct phenomena: the former refers to valuable data sets that are the exclusive property of these firms, while the latter refers to the ability of firms inside a single value chain to scale up their operations (firms that own predominantly intangible assets can do this faster and more cheaply).

Durand’s taxonomy is elegant. Armed with these categories, he begins to see rentiers everywhere—not unlike the theorists of cognitive capitalism whom he chided, mildly, in Fictitious Capital—and capitalists nowhere. ‘The ascent of the digital’, he concludes, ‘feeds a giant economy of rent’, because ‘the control of information and knowledge, that is, intellectual monopolization, has become the most powerful means of capturing value.’ With a nod to McKenzie Wark’s recent speculations on the subject, Durand returns to the question he asked in 2014: is this still capitalism? It was the imperative to invest in order to improve productivity, cut costs and raise profits that ensured the dynamism of the capitalist system. That imperative was due to capitalists operating under the pressures of market competition, with the fungibility of commodities, labour and technology—the result, as Brenner argued, of breaking up the ‘merger’ of these three factors under feudalism.

The rise of intangibles—but especially of data—reverses the capitalist break-up of that merger, Durand argues: if digital assets are indissociable from the users that produce them and from the platforms wherein they are made, then we can read the digital economy as once again ‘merging’ the main factors of production, so that their mobility is impeded. In simpler terms, we are stuck inside the walled gardens of the tech companies, our data—carefully extracted, catalogued and monetized—tying us to them forever. This weakens the productivity-inducing effects of market competition, giving those who control the intangibles an impressive ability to appropriate value without ever having to engage in production. ‘In this configuration,’ writes Durand, ‘investment is no longer oriented towards the development of the productive forces, but to the forces of predation.’

Parasitism and dispossession may no longer be part of Durand’s vocabulary in Techno-féodalisme—they are replaced by ‘predation’, as Harvey and Lenin are dismissed in favour of Thorstein Veblen, and finance gives way to the technology industry—but the logic is not so different from that of Fictitious Capital. What gives the digital economy its peculiar neo- and techno-feudal flavour is that, while workers are still being exploited in all the old capitalist ways, it is the new digital giants, armed with sophisticated means of predation, who benefit most. Analogously to the feudal lords, they manage to appropriate huge chunks of the global mass of surplus value without ever being directly involved in labour exploitation or the productive process. Durand draws on Zuboff’s work to show the hidden domination exercised by the ‘Big Other’ of Big Data, arguing as she does that the secret of Google’s success lies in its ability to extract, assemble and profit from a variety of data sets. It enjoys an effective monopoly due to network effects and impressive economies of scale: it will benefit more from any new data sets than a start-up could, making competition much harder.

There is much wisdom, as well as basic common sense, in such conclusions. But the overall tenor of the argument veers too much towards user-ism, as Durand, like Zuboff, ignores the crucial role played by indexing in Google’s overall operation. It is harder to invoke concepts like ‘intellectual monopolization’ here, for the third-party pages to which Google links to produce its search-result commodity remain the property of their publishers; Google doesn’t own the results that it indexes. In theory, any other well-capitalized firm could build the web-crawling technology for indexing them. It might be extremely expensive, but one shouldn’t confuse such barriers for a rent-like situation: what is expensive for a Berlin start-up might be relatively affordable for Japan’s SoftBank, with its $100 billion Vision Fund. Google’s extensive data holdings are a different matter; they do merit a discussion of rent. But one cannot pretend that its business is all about these data holdings, as if Google were a mere rentier—and not also a standard capitalist firm.

...

In the past twenty years, a new approach to political economy known as Capital as Power (CasP), has emerged to do just that, introducing the concept of ‘differential accumulation’ to describe such dynamics. Its adherents, concentrated mostly at York University in Canada, have criticized both Marxist and neoclassical economics—using some solid and convincing arguments—for overlooking these ‘sabotage’ dynamics and ignoring the constitutive role of power in capitalism as a whole. This approach has informed some interesting recent research on the technology industry, including empirically rich work on techno-scientific rent and assetization, with insights from Science & Technology studies.

The difficulty of fitting Marx and Veblen into a single analytical framework here—something Durand also attempts in a recent essay—is that Marx saw predation and sabotage as part and parcel of feudalism, not capitalism. For Veblen, these are instincts present in all capitalists, even if those with control over intangible assets may be better positioned to act upon them. Marx, however, ultimately saw capitalists as productive; if one could speak of sabotage, this would only be possible at the systemic level of capitalism as a whole and not at the level of individual capitalists. Durand clearly wants to stay with Marx rather than Veblen. However, that would require spelling out just what exactly these ‘forces of predation’ are and how they relate to accumulation and all the thorny debates on ‘primitive accumulation’—a theoretical challenge that Durand, having engaged with ‘accumulation by dispossession’ in Fictitious Capital, knows all too well. Otherwise, it’s not clear why Marxist theory would need this highly ambiguous theoretical carapace of ‘predation’, when its own categories—of profit and capitalist production, as well as rent and rentierism—suffice to explain Google’s success.

Marx himself was unequivocal about the fact that fully automated capitalist firms not only appropriate surplus value derived elsewhere—on this, both Foley and Durand agree—but that they do so as profits, not rent. These automated firms are as capitalist as the firms that exploit wage labour directly. As Marx writes in Volume 3:

A capitalist who employed no variable capital at all in his sphere of production, hence not a single worker (in fact an exaggerated assumption), would have just as much an interest in the exploitation of the working class by capital and would just as much derive his profit from unpaid surplus labour as would a capitalist who employed only variable capital (again an exaggerated assumption) and therefore laid out his entire capital on wages.

The techno-feudal thesis stems not from the advance of contemporary Marxist theory, but from its apparent inability to make sense of the digital economy—of what, exactly, is produced in it and how. If one accepts that Google is in the business of producing search-result commodities—a process that does require massive capital investment—there is no great difficulty in treating it as a regular capitalist firm, engaged in normal capitalist production. This is not to say that the digital giants do not engage in all sorts of other tactics to consolidate their power, leverage their patent portfolios, lock in their users and obstruct any possible competition, often by buying challenger start-ups, in addition to the fortunes spent on winning the support of lawmakers on Capitol Hill.

Capitalist competition is a nasty business and it may be even nastier when digital products are involved. But this is no reason to fall into the analytical swamps of cognitive capitalism, user-ism or techno-feudalism. Both Veblen and Marx may be needed if we want to understand the tactics of individual firms and the systemic consequences of their actions; in that sense, there’s much that Marxists can learn from the ‘Capital as Power’ school. But for either approach to make great strides forward, one needs to be at least clear about the business models of the firms in question. Fixating on aspects of them—simply because one detects an excess of intellectual-property rights, or signs of financialization, or some other disturbing process—is not going to provide a comprehensive view of those models.

7. Enter the State

As well as lack of analytical clarity, another major problem with the techno-feudalist framework is that it risks taking the state out of the picture. Durand’s Techno-féodalisme has very little discussion of the driving role of the American state in the rise of Alphabet, Facebook or Amazon; the same goes for many other shorter texts on techno-feudalism. Durand’s critique of what he dubs the Californian Ideology makes much of the cyber-libertarian orientation of the ‘Magna Carta of Cyberspace’, its foundational text. But he neglects to mention that one of that document’s four authors, the prominent investor Esther Dyson, also spent years on the board of the National Endowment for Democracy, America’s finest regime-change outlet.

Save for a few contrarian accounts—among them, Linda Weiss’s excellent America Inc.? Innovation and Enterprise in the National Security State (2014)—the role of the American state in the rise of Silicon Valley as a global techno-economic hegemon has been greatly understated. Reading these developments through the lens of techno-feudalism—which assumes that states are weak, with sovereignty ‘parcelized’ among many techno-lords—can only obfuscate this further. All the recent techlash hysteria about the power of technology companies—as ‘giants’ or ‘robber barons’, or just one monolithic ‘Big Tech’ bloc—has entrenched the notion that the rise of digital platforms has come at the cost of the state’s disempowerment.

This may be the case for weaker European or Latin American countries, all but colonized by American firms in recent years. But can the same be said for the United States itself? What of the longstanding links between Silicon Valley and Washington, with Google’s former ceo, Eric Schmidt, leading the Defense Innovation Board, an advisory body to the Pentagon itself? What about Palantir, the company co-founded by Thiel which provides essential links between the us surveillance state and American tech? Or Zuckerberg’s argument—apparently effective so far—that breaking up Facebook would embolden the Chinese technology giants and weaken America’s standing in the world? Geopolitics is barely visible within the techno-feudalist perspective: Durand’s few mentions of China are mostly to scold its Social Credit system, an instrument of algorithmic governmentality.

Could this lack of attention to the constitutive role played by the state in the consolidation of the American tech industry be the result of the analytical, Brennerian framings of capitalism that seek to deduce its ‘laws of motion’ by observing it in action? It is impossible to grasp the ascendancy of the American tech industry if one brackets out the Cold War and the War on Terror—with their military spending and surveillance technologies, as well as the global network of American military bases—as extraneous, non-capitalist factors, of little importance to understanding what ‘capital’ wants and what it does. Could one make the same mistake today, when the ‘rise of China’ and climate catastrophe are coming to occupy the system-orienting role once played by the Cold War? If so, we can also forget about comprehending the rise of what some have dubbed ‘asset-manager capitalism’, which seeks to delegate the state’s task of fighting climate change to the likes of Blackrock, Vanguard and State Street.

From the Brennerian vantage point, any systemic intervention by the state into the ongoing operations of capital might appear as an example of ‘political capitalism’—rather than properly functioning ‘economic’ capitalism, driven by its own laws of motion. For Brenner himself, the long-term stagnation of the us economy in conditions of global manufacturing over-capacity has led powerful elements of the American ruling class to abandon their interest in productive investment and turn instead to the upward redistribution of wealth by political means. In this, strangely, left and right appear to converge. After all, detecting the corrosive effects of ‘political capitalism’ everywhere is much more typical of liberal and neoliberal economics, concerned as they are with rent-seeking by public officials and the resurgence of personalistic networks intervening in the operations of capital. It was this kind of concern about ‘political’ rather than ‘economic’ capitalism that gave rise to Public Choice and the fetishization of anti-corruption by Chicago economists such as Luigi Zingales. Durand himself repeatedly engages with Mehrdad Vahabi, a Public Choice scholar, citing him favourably on predation.

Perhaps it is now time to ask whether the Brenner–Wallerstein debate is in for some definitive resolution. Arguably, the unresolved ambiguities of that debate have created the analytical and intellectual openings through which the techno-feudalist thesis now appears plausible to creative young Marxian economists like Durand. After all, it is only because ongoing expropriation, and the political power that it presupposes, cannot be easily reconciled with the exploitation-driven account of capitalist development that one needs extraneous concepts like Harvey’s ‘accumulation by dispossesion’, Veblen’s ‘predation’, Vercellone’s ‘cognitive rent’, or even Zuboff’s ‘extraction of behavioural surplus’.”

- EVGENY MOROZOV, “CRITIQUE OF TECHNO-FEUDAL REASON.” New Left Review. 133/134. Jan/Apr 2022.

#evgeny morozov#new left review#techno-feudalism#capitalism#political economy#big data#surveillance capitalism#accumulation by dispossession#sabotage capitalism#neoliberal capitalism#workerism#fictious capital#academic quote#literature survey#feudalism#rentier class

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

They're handing out patents for "inventions" that don't exist

Today (Oct 16) I'm in Minneapolis, keynoting the 26th ACM Conference On Computer-Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing. Thursday (Oct 19), I'm in Charleston, WV to give the 41st annual McCreight Lecture in the Humanities. And on Friday (Oct 20), I'm at Charleston's Taylor Books from 12h-14h.

Patent trolls produce nothing except lawsuits. Unlike real capitalist enterprises, a patent troll does not “practice” the art in its patent portfolio — it seeks out productive enterprises that are making things that real people use, and then uses legal threats to extract rents from them.

One of the most prolific patent trolls of the twenty-first century is Landmark Technology, whose U.S. Patent №7,010,508 nominally covers virtually anything you might do in the course of operating an online business: having a homepage, letting a customer login to your site, or having pages where customers can view and order products.

Landmark shook down more than a thousand productive businesses for $65,000 license-fees it demanded on threat of a patent lawsuit.

But that reign of terror is almost certainly over. When Landmark tried to get $65,000 out of Binders.com, the victim’s owner, NAPCO, went to court to invalidate Landmark’s patent, which never should have issued.

A North Carolina court agreed, and killed Landmark’s patent. Landmark faces further punishments in Washington State, where the attorney general has sued the company for violating state consumer protection laws in a case that has been removed to federal court.

Landmark’s patent contains “means-plus-function” claims. These a rentier’s superweapon, in which a patent can lay a claim over an invention without inventing or describing it. These claims are almost entirely used in software patents, something that has been blessed by the Federal Circuit, America’s most authoritative patent court.

A means-plus-function patent lets an “inventor” patent something they don’t know how to do. If these patents applied to pharma, a company could get a patent on “an arrangement of atoms that cure cancer,” without specifying that arrangement of atoms. Anyone who actually did cure cancer would have to pay rent to the patent-holder.

-A Major Defeat For Technofeudalism: We euthanized some rentiers.

My next novel is The Lost Cause, a hopeful novel of the climate emergency. Amazon won't sell the audiobook, so I made my own and I'm pre-selling it on Kickstarter!

#technofeudalism#rentiers#class struggle#capitalists hate capitalism#unity#patent trolls#means-plus-function

774 notes

·

View notes

Text

moderation wage labor is inhumane and this is one functional reason social media is a fundamentally insolvent concept

#not that other wage labor isn't categorically inhumane (basically all wage labor under capitalism is inhumane)#but moderation labor... look i can both think facebook sucks institutionally *and* think nobody should have to look at the shit there#especially when they're being paid an absolute pittance and aren't being offered therapy. and especially with graphic gore and csam etc#like look. anyone who does meaningful moderation labor should own a share of the platform they help maintain.#and this is basically never going to happen as long as the owner/rentier/capitalist class exists and owns these platforms#moderation#labor#capitalism#social media#alienation of labor

69 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Remember, kids, no matter what economic model you believe in, landlords are the worst.

#economics#socialism#capitalism#georgism#anti-landlords#brought to you by me learning that keynes also railed against the rentier class#as he called it#you say passive income? i say reaping where you do not sow

31 notes

·

View notes

Note

Could the Iron Throne be able to issue bonds, to finance its expenses, instead of going to the Iron Bank for a loan?

A government issuing bonds is the same thing as the government taking out a loan. The main difference is that, in the case of issuing a bond, the government is spreading out its borrowing between many lenders by selling bonds on the open market to anyone who wants to buy them rather than having that loan owed to a single entity like the Iron Bank. This means that the government is less beholden to any one creditor and it's less likely that the government's creditors can use their economic leverage to affect government policy.

The second advantage of structuring government debt through bonds is that it allows the government to break its total borrowing needs into smaller, more affordable units. Very few financial institutions would have had the capital to finance the £1,200,000 that made up the government's inaugural loan at the Bank of England in 1690 - but a lot more people could afford to lend the government £10, £25, £50, or £100 pounds.

Between this and later innovations in marketing bonds to the general public, the market for government debt was massively expanded. Not only did this create a class of rentiers who were now personally invested in the government's success, but it also immediately deepened the capital markets by creating a large supply of stable assets that could be bought and sold and borrowed against. While some of the shortcomings of the Hamilton musical and Chernow's biography have become more obvious in hindsight, they're not wrong about the impact of Hamilton's policies as Treasury Secretary on the development of the American economy.

The difficulty facing the Iron Throne in adapting an early modern system of government finance is that it doesn't have the state capacity to run this kind of an operation: it doesn't have a central bank to act as the government's marketer, issuer of banknotes, and lender of last resort; it doesn't have a sinking fund to manage the level and price of debt; it hasn't issued charters to merchant's guilds or joint-stock companies that could combine the small capital of individuals and thus more easily afford to buy bonds; and it doesn't have enough literate people who've studied accounting to staff a royal bureaucracy large enough to coordinate and keep records of all of this economic activity.

#asoiaf meta#asoiaf#medieval banking#medieval economics#medieval finance#early modern finance#westerosi economic development#early modern economy#central banking#westerosi economic policy#early modern state building

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

forcing people to read marx at gunpoint so we can avoid the question "does owning the means of your production make you bourgeois?" when it's really a class relation typically and predominantly defined by the employing or other capital-holding classes, such as rentiers

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sorry I’m still thinking abt that white woman calling a struggling Chinese immigrant run laundromat an evil bourgeois rentier capitalist business and bootlicking for the fucking IRS of all entities and going “it’s class analysis sweetie”. Lord

114 notes

·

View notes

Text

All in the family

I finally broached the subject of Fox News and the Big Lie with my Trumper sister. As I suspected, being a Fox-only viewer, she had never even heard of the Dominion lawsuit and exposure of Fox and its 'talent' as bald-faced liars. Here's what I wrote her in response:

I know it must be hard to realize there is a TV network that to all outward appearances is a normal news outlet but is in actuality a sophisticated propaganda operation. Trump, as Joseph Goebbels before him, knew that if you repeat a lie enough times people will believe it because...well...they've heard it so many times it just must be true. Fox follows the same strategy.

Trump's inauguration had the biggest crowd ever. Remember that? The lying started on the first day. Crime is rising and out of control. Cities are too dangerous to go out at night. Lies. NYC is safer than Tallahassee and Atlanta. You'd never know that watching Fox News. Convoys of criminals are swamping the border. False. In any event, the US needs immigration. Who will clean the pools and pick the strawberries? Yes, current laws are a mess, but that's because the GOP torpedoes every attempt to fix them. Why solve a problem that provides such a juicy cudgel to beat your opponent with?

The US is a broken system right now and I'm not sure it can be fixed. One side is trying to conduct business as usual, even if they are flawed humans and make mistakes. Bridges and roads are finally getting repaired. LGBTQ+ problems are being addressed instead of condemned. Do I agree with every policy the Dems have? Christ I don't even understand some of them. I have to stop and do a mental walk-through to get it straight in my head what a trans woman is. But the other side is destruction and division. Marginalize the poor. Restrict women's right to control her own body. Banning books? The people in history who have done that never come out as the good guys.

Turn away the refugee, despite what their Good Book says. Look the other way when thousands of innocent children are mowed down into grotesque chunks of meat by weapons of war in the hands of other children. It's not 'mental health', it's not 'too soon' to talk about it. It's too many guns of a kind that should never be in civilian's hands.

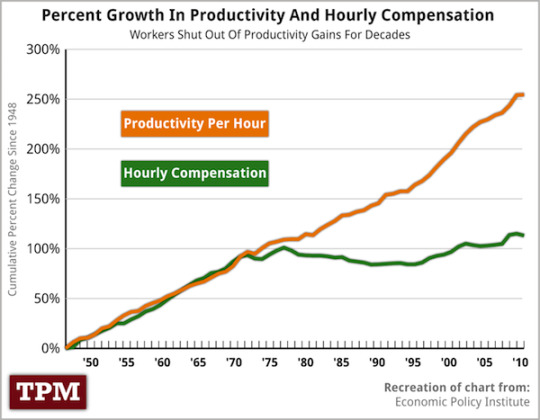

I have to include one chart, but it pretty much explains why the country you and I grew up in is no longer. The ability to raise a family, buy a house, send your kids to college, and take a vacation every year on one income is long gone. Why? Here's your answer:

Yes, the chart ends in 2010 but the damage had already been done. What it shows is that the profit made by producing goods and services was diverted away from the people producing them and taken instead by the 'rentier' class -- the owners. How? Well, Reagan broke the unions in his first months in office. (Air traffic controllers strike). The SEC bowed to pressure and for the first time allowed stock buy-backs, meaning companies could direct profits straight to the owners, bypassing the workers. The new oligarchs discovered they could buy the lawmakers and the courts and cut taxes drastically. The gap between the two lines in the chart represents trillions of dollars that were diverted from the workers to the owners. They should have just stuck to share-and-share alike and not gotten so greedy.

I could go on for a long time. There has been so much damage done...

As Jon Stewart said -- I guess I'm woke. I just thought I was good in history.

She basically replied "both sides are dirty" and told me to fuck off.

Oh well.

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

"At Future of Freedom Foundation, Jacob Hornberger writes: “America’s welfare state way of life is based on the notion that the federal government is needed to force people to be good and caring to others.”

Um, no. America’s welfare state way of life is based on the notion that, since the capitalist state redistributes massive amounts of income and wealth upwards from producers to rentiers as profit, rent, and interest, compensatory state action — namely, returning a tiny fraction of that income to the neediest — is necessary to preventing capitalism from collapsing from social disorder or insufficient aggregate demand.

The welfare state did not come about as the result of any idealistic “notion” on the part of do-gooders and bleeding-hearts. Such people may have helped sell it politically, but the architects of the welfare state were hard-headed capitalists who rightly understood its necessity for keeping capitalism to sustainable levels of extraction. Of course the capitalist state was motivated in part by the grass-roots activism of the destitute and unemployed, but the specific form the welfare state took was determined by policy elites understanding of the system’s survivability needs.

Ironically, no one understands the need for a powerful interventionist regulatory and welfare state better than capitalists. And nothing would destroy capitalism faster than right-libertarians who, if given free rein, would balance the federal budget, pay off the debt, and eliminate the welfare state.

Way back in the 1860s, Karl Marx characterized the Ten-Hour Day legislation passed by the British Parliament as employers acting through their state to limit the exploitation of labor to sustainable levels. The length of the working day in 19th century Britain presented capitalists with a problem akin to the prisoner’s dilemma.

It was in the interest of the capitalist class as a whole that the exploitation of labor be kept to sustainable levels, but in the interest of capitalists severally to gain an immediate advantage over the competition by working their own laborers to the breaking point. The capitalist state solved the problem by limiting the working day on behalf of employers collectively, so that individual employers could not defect from the agreement. In the chapter on the Ten-Hour Day in Capital, he wrote:

These acts curb the passion of capital for a limitless draining of labour power, by forcibly limiting the working day by state regulations, made by a state that is ruled by capitalist and landlord. Apart from the working-class movement that daily grew more threatening, the limiting of factory labour was dictated by the same necessity which spread guano over the English fields.

Marx referred, later in the same chapter, to a group of 26 Staffordshire pottery firms, including Josiah Wedgwood, petitioning Parliament in 1863 for “some legislative enactment”; the reason was that competition prevented individual capitalists from voluntarily limiting the work time of children, etc., as beneficial as it would be to them collectively: “Much as we deplore the evils before mentioned, it would not be possible to prevent them by any scheme of agreement between the manufacturers…. Taking all these points into consideration, we have come to the conviction that some legislative enactment is wanted.”

The smarter capitalists, similarly, support a welfare state for two main reasons. First, the capitalist state’s upward distribution of income in the form of economic rents creates a maldistribution of purchasing power, which in turn results in chronic tendencies toward underconsumption and idle production capacity — tendencies which periodically almost destroyed capitalism (most notably in the Great Depression of the 1930s). Redistributing a small portion of this income to at least the poorest part of the population, and otherwise bolstering aggregate demand, is necessary in order to prevent depression.

Second, if the worst forms of destitution are not addressed, starvation and homelessness will reach levels that threaten political radicalization, disorder, and violence.

At every step of the way, the primary architects of the 20th century mixed economy were hard-headed capitalists. There is enough historiography on this theme by James Weinstein, Gabriel Kolko, G. William Domhoff, and Frances Piven to keep Hornberger busy for many months.

If anything destroys the average person’s faith in freedom, it is the pretense of people like Hornberger that the capitalist system they defend is the product of freedom rather than of massive state violence, and the association in the popular mind of the language of “freedom” with the system they experience daily as a boot on their neck."

-Kevin Carson, "Capitalism, Not Welfare, Has Destroyed Faith in Freedom"

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

page 538 - Imagine there could be resources that were in abundance?

It would be pretty cool. There would be no profit margin to be had if supply was infinite, no matter the demand.

I wonder how many false shortages there are? Monopolies and market makers in the background limiting supplies to get everyone freaking out, worried that they won't get theirs.

#maximizing renewable resource rent#renewable#renewable resource#rent#rentier#rentier class#class war#value of sustainable yield#economic rent with biomass#biomass#harvest#harvesting#government#economics#economy#economis#the economist#false shortage#corruption#democrat#tyranny#hypocrisy

14 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Prevention of the re-imposition of New Deal rentier repression has long been a priority of both US political parties. Right-wing populism is just one inchoate reflex against financialization’s street-level consequences. The “establishment Republicans” are still committed to the rentier class, or what’s left of establishment Republicans after Trumpism. Likewise, the toothless, gerontocratic Democratic and Labor parties (now tactically “woke”) still carry water for finance capital, too.

Stan Goff

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Washington State's capital gains tax proves we can have nice things

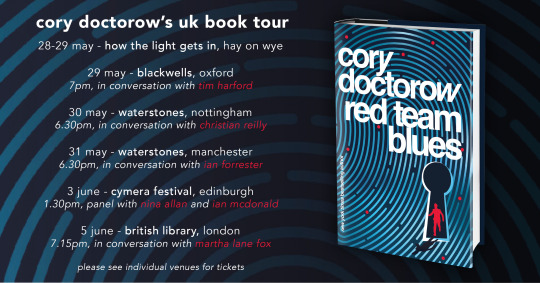

Today (June 3) at 1:30PM, I’m in Edinburgh for the Cymera Festival on a panel with Nina Allen and Ian McDonald.

Monday (June 5) at 7:15PM, I’m in London at the British Library with my novel Red Team Blues, hosted by Baroness Martha Lane Fox.

Washington State enacted a 7% capital gains tax levied on annual profits in excess of $250,000, and made a fortune, $600m more than projected in the first year, despite a 25% drop in the stock market and blistering interest rate hikes:

https://www.theurbanist.org/2023/06/01/lessons-from-washington-states-new-capital-gains-tax/

Capital gains taxes are levied on “passive income” — money you get for owning stuff. The capital gains rate is much lower than the income tax rate — the rate you pay for doing stuff. This is naked class warfare: it punishes the people who make things and do things, and rewards the people who own the means of production.

The thing is, a factory or a store can still operate if the owner goes missing — but without workers, it shuts down immediately. Everything you depend on — the clothes on your back, the food in your fridge, the car you drive and the coffee you drink — exists because someone did something to produce it. Those producers are punished by our tax system, while the people who derive a “passive income” from their labor are given preferential treatment.

The Washington State tax is levied exclusively on annual gains in excess of a quarter million dollars — meaning this tax affects an infinitesimal minority of Washingtonians, who are vastly better off than the people whose work they profit from. Most working Americans own little or no stock, and the vast majority of those who do own that stock in a retirement fund that is sheltered from these taxes.

(Sidebar here to say that market-based pensions are a scam, a way to force workers to gamble in a rigged casino for the chance to enjoy a dignified retirement; the defined benefits pension, combined with adequate Social Security, is the only way to ensure secure retirement for all of us)

https://pluralistic.net/2020/07/25/derechos-humanos/#are-there-no-poorhouses

Washington’s tax was anticipated to bring in $248m. Instead, it’s projected to bring in $849m in the first year. Those funds will go to public school operations and construction and infrastructure spending:

https://www.seattletimes.com/seattle-news/politics/was-new-capital-gains-tax-brings-in-849-million-so-far-much-more-than-expected/

That is to say, the money will go to ensuring that Washingtonians are educated and will have the amenities they need to turn that education into productive work.

Washington State is noteworthy for not having any state personal or corporate income tax, making it a haven for low-tax brain-worm victims who would rather have a dead gopher running their states than pay an extra nickel in taxes. But places that don’t have taxes can’t fund services, which leads to grotesque, rapid deterioration.

Washington State plutes moved because they relished living in well-kept, cosmopolitan places with efficient transportation, an educated workforce, good restaurants and culture — none of which they would have to pay for. They forgot Karl Marx’s famous saying: “There’s no such thing as a free lunch.”

The idea that Washington could make up for the shortfalls that come from taxing its wealthiest residents by levying regressive sales taxes and other measures is mathematically illiterate wishful thinking. When the one percent owns nearly everything, you can tax the shit out of the other 99% and still not make up the shortfall.

Meanwhile: homelessness, crumbling roads, and crisis after crisis. Political deterioration. Cute shopping neighborhoods turn into dollar store hellscapes because no one can afford to shop for nice things because all their income is going to plug the gaps in health, education, transport and other services that the low-tax state can’t afford.

Washington State’s soak-the-rich tax is ironic, given the propensity of California’s plutes to threaten to leave for Washington if California finally passes its own extreme wealth tax.

There’s a reason all these wealthy people want to live in California, Washington, New York and other states where there’s broad public support for taxing the American aristocracy: states with rock-bottom taxes are failed states. All but two of America’s “red states” are dependent on transfers from the federal government to stay in operation. The two exceptions are Texas, whose “free market” grid is one nanometer away from total collapse, and Florida, which is about to slip beneath the rising seas it denies.

Rich people claim they’d be happy to live in low-tax states, and even tout the benefits of a desperate workforce that will turn up to serve drinks at their country clubs even as a pandemic kills them at record rates. But when the chips are down, they don’t want to depend on a private generator to keep the lights on. They don’t want to have to repeatedly replace their luxury cars’ suspension after it’s wrecked by gaping potholes. They don’t want to have to charter a jet to fly their kids out of state to get an abortion.

This is true globally, too. As Thomas Piketty pointed out in Capital in the 21st Century, if the EU and OECD created a wealth tax, the rich could withdraw to Dubai, the Caymans and Rwanda, but they’d eventually get sick of shopping for the same luxury goods in the same malls guarded by the same mercenaries and want to go somewhere, you know, fun:

https://memex.craphound.com/2014/06/24/thomas-pikettys-capital-in-the-21st-century/

We’re told that Americans would never stand for taxing the ultra-rich because they see themselves as “temporarily embarrassed millionaires.” It’s just not true: soak-the-rich policies are wildly popular:

https://balanceourtaxcode.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/WA-State-Wealth-Tax-Poll-Results-3.pdf

The Washington tax windfall is fascinating in part because it reveals just how rich the ultra-rich actually are. Warren Buffett says that “when the tide goes out, you learn who’s been swimming naked.” But Washington’s new tax is a tide that reveals who’s been swimming with a gold bar stuck up their ass.

It’s not surprising, then, that Washingtonians are so happy to tax their one percenters. After all, this is the state that gave us modern robber barons like Bill Gates and Jeff Bezos. And then there’s clowns like Steve Ballmer, star of Propublica’s IRS Files, the man whose creative accounting let him claim $700m in paper losses on his basketball team, allowing him to pay a mere 12% tax on $656m in income, while the workers who made his fortune on the court paid 30–40% on their earnings.

https://pluralistic.net/2021/07/08/tuyul-apps/#economic-substance-doctrine

Ballmer’s also a master of “tax loss harvesting,” who has created paper losses of over $100m, letting him evade $138m in federal taxes:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/04/24/tax-loss-harvesting/#mego

These guys aren’t rich because they work harder than the rest of us. They’re rich because they profit from our work — and then, to add insult to injury, pay little or no taxes on those profits.

Washington’s lowest income earners pay six times the rate of tax as the state’s richest people. When the wealthy squeal that these taxes are class warfare, they’re right — it is class war, and they started it.

Catch me on tour with Red Team Blues in Edinburgh, London, and Berlin!

If you’d like an essay-formatted version of this post to read or share, here’s a link to it on pluralistic.net, my surveillance-free, ad-free, tracker-free blog:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/06/03/when-the-tide-goes-out/#passive-income

[Image ID: The Washington State flag; the circular device featuring George Washington has been altered so that it is now the head of a naked man clothed in a barrel with two wide leather shoulder straps.]

#pluralistic#steve ballmer#irs files#washington state#soak the rich#capital gains#taxes class war#euthanasia of the rentier

425 notes

·

View notes

Text

NEO-LIBERALISM AT THE CROSSROADS — WHAT NEXT?

Despite the global crisis of neo-liberal capitalism, what alternatives are being proposed? This is the question that must be faced.

Neo-liberalism is not a solution for the working and poor masses. It has forced labour into retreat through flexible labour markets characterised by outsourcing, subcontracting, labour brokerage and mass firings. It has weakened the organisational power of the working class, and promoted the proliferation of unorganised, vulnerable employment and an expanding informal sector. Meanwhile the commodification of welfare, the removal of subsidies, and rising taxes and prices, have hit the masses hard.

In the face of the challenges, the MTUC and the Malaysian labour movement need to revise its organising and political strategy. It is important to build a counter-movement that can replace the existing rentier and predatory state system with a participatory democracy from the bottom-up, based on the principles of equality and social justice as envisioned by the anarchists and the “Chicago Martyrs.”

#Malaysia#May Day#social movements#labor#Malaysian politics#anarchism#resistance#autonomy#revolution#community building#practical anarchism#anarchist society#practical#anarchy#daily posts#communism#anti capitalist#anti capitalism#late stage capitalism#organization#grassroots#grass roots#anarchists#libraries#leftism#social issues#economics#anarchy works#environmentalism#environment

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The third reason is semantic, but not merely. During the Revolution the words 'bourgeois' and 'bourgeoisie' are highly uncommon in speeches, debates and newspapers. I have sought for them in Robespierre, in Brissot, in Loustalot, in Marat and in Hébert: I have found 'the rich', 'hoarders', 'aristocrats', 'plotters', 'monopolists', 'rogues', 'rentiers', but scarcely a single 'bourgeois'.

This rarity of the word, to my mind, means something very clear, expressing the absence of the thing. The bourgeoisie did not exist as a class. There were certainly rich and poor people, haves and have-nots, but this does not amount to a bourgeoisie and a proletariat. Was the revolution bourgeois or not? That is a question I refuse to ask, as it basically has no meaning.

A People's History of the French Revolution, Eric Hazan

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

"What can humans do that machine learning can't? Can you prove it? Prove that machine learning can't!" I've seen a lot of versions of this question now, and it's often framed like the progressive take, like someone who can't consider the shiny AI future is the close-minded one. What makes humans special basically. This is the question. This is called science now. And we all agree here that underpaying artists and propagating stereotypes via AI is bad, but this specific question is personally really hard to actually answer. Lack of intent and responsibility and dependence on plagiarism are answer enough for me, but it's fuzzy. I want a stainless steel discussion devourer.

The computational linguist Dr. Emily Bender has written a lot on the limits of large language models, and if anyone has a definitive answer, I thought it'd be her. But she doesn't. When it comes to the outright question, she actually refuses. "I'm not going to converse with people who won’t posit my humanity as an axiom in the conversation." (interview with Elizabeth Weil, New York Magazine) I was disappointed at first, but I've since processed this as the mark of a professional at asking the right questions. The wrong question is the provable difference between a human and a computer; the right question is why so many people are asking that wrong one. The right answer to the right question is labor.

"Eighteen-century race theory saw, within the human category, a hierarchy of races. And of course, the architects of this theory were white Europeans, so they modestly placed themselves at the very pinnacle of the human category. The lower edges of the human category merged into the apes, according to this way of looking at things." -David Livingstone Smith (interview with Neal Conan, NPR). He discusses in the same interview slavery, nazis calling Jews rats, and ancient Mesopotamian political dehumanization. Animals are cheaper labor and are easier to slaughter. When there is profit and conquest to be had, people start asking if there really is a difference between those other people and animals. This was called science then.

These "other people" can't be pointed out so publicly now. And yet, thanks to advancements in neoliberal theory, the bigotry persists along the scenic route. It goes like: dehumanize all humans without regard to race, but especially humans' labor, which targets the working class, and therefore the rich get richer anyways. Diversity win! It starts with art and prose, but these arguments are being wheeled out to underpay people in every industry. I thought the question inconveniently annoying when it seemed useful for rentiers and ceos. Now I believe the ruling class indirectly created the question. So I refuse to answer it too. Except to say this: Humans are already doing the work, all of it. Human labor is proven.

#ai#capitalism#if no one's still thinking about this that'd be the best news of my day but it's been bothering me since this tech blew up#i can finally sleep at night maybe#tech

3 notes

·

View notes