#political economy

Note

If management finds a way to automate jobs during a strike, is that scabbing?

Peripherally.

The automation itself is more part of the general category of management strategies to restructure workflow and production methods in order to reduce the need for, and thus the power of, labor. This dates back to the origins of Taylorism itself in the 1890s as an effort to “steal the brains from underneath the cap of labor” and through to the emergence of Human Relations and Industrial Psychology in the early 20th century as a means to better control workers. So I think you could see in as essentially equivalent to classic speed-up and stretch-out efforts to maintain production at as low a cost as possible during a strike, and thus break the union.

However, the dirty truth of automation is that there is no clean way to fully substitute machinery for labor. Due to the inherent limitations of technology at any stage of development, you need labor to repair and maintain and monitor automated systems, you need labor to install and operate the machines, you need labor to design and program and manufacture the machines. (This is one reason why the job-killing predictions around automation often fall flat, because the supposedly superior new technology often requires a significant increase in human labor to service the new technology when it breaks. For example, this is why automation in fast food has proven to be so difficult and partial than expected: it turns out that self-checkout machines are actually very expensive to operate in terms of skilled manpower.) And to the extent that a given automation contract or project is being undertaken during a strike in order to break that strike, that’s absolutely scabbing.

#labor#labor history#trade unions#unions#strikes#automation#Taylorism#political economy#economic history#scabbing#labor studies

131 notes

·

View notes

Text

September 11, 1973: On the 50th Anniversary of the Coup in Chile

Today marks the 50th anniversary of the coup d’état in Chile, when a fascist junta led by dictator Augusto Pinochet overthrew the democratically elected socialist government of Salvador Allende. For those of us who are on the left, the story should be familiar by now: Allende had charted a ‘Chilean way to socialism' ("La vía chilena al socialismo") quite distinct from the Soviet Union and communist China, a peaceful path to socialism that was fundamentally anti-authoritarian, combining worker power with respect for civil liberties, freedom of the press, and a principled commitment to democratic process. For leftists who had become disillusioned with the Soviet drift into authoritarianism, Chile was a bright spot on an otherwise gloomy Cold War map.

What happened in Chile was one of the darkest chapters in the history of US interventionism. In August 1970, Henry Kissinger, who was then Nixon’s national security adviser, commissioned a study on the consequences of a possible Allende victory in the upcoming Chilean presidential election. Kissinger, Nixon, and the CIA—all under the spell of Cold War derangement syndrome—determined the US should pursue a policy of blocking the ascent of Allende, lest a socialist Chile generate a “domino effect” in the region.

When Allende won the presidency, the US did everything in their power to destroy his government: they meddled in Chilean elections, leveraged their control of the international financial system to destroy the economy of Chile (which they also did through an economic boycott), and sowed social chaos through sponsoring terrorism and a shutdown of the transportation sector, bringing the country to the brink of civil war. Particularly infuriating to the Americans was Allende’s nationalization of the copper mining industry, which was around 70% of Chile’s economy at the time and was controlled by US mining companies like Anaconda, Kennecott and the Cerro Corporation. When the CIA’s campaign of sabotage failed to destroy the socialist experiment in Chile, they resorted to assisting general Augusto Pinochet's plot to overthrow the democratically elected government. What followed was a gruesome campaign of repression against workers, leftists, poets, activists, students, and ordinary Chileans—stadiums were turned into concentration camps where supporters of Allende’s Popular Unity government were tortured and murdered. During Pinochet’s 17-year reign of terror, 3,200 people were executed and 40,000 people were detained, tortured, or disappeared, 1,469 of whom remain unaccounted for. Chile was then used as a laboratory for neoliberal economic policies, where the Chicago boys and their ilk tested out their terrible ideas on a population forced to live under a military dictatorship.

It shatters my heart, thinking about this history. I feel a personal attachment to Chile, not only because my partner is Chilean (his father left during the dictatorship), but because I’ve always considered Chile to be a world capital of poetry and anti-authoritarian leftism. The filmmaker Alejandro Jodorowsky asks, “In how many countries does a real poetic atmosphere exist? Without a doubt, ancient China was a land of poetry. But I think, in the 1950s in Chile, we lived poetically like in no other country in the world.” (Poetry left China long ago — oh how I wish I’d been around to witness the poetic flowering of the Tang era!) Chile has one of the greatest literary traditions of the twentieth century, producing such giants as Bolaño and Neruda, and more recently, Cecilia Vicuña and Raúl Zurita, among others.

To commemorate the 50th anniversary of the coup, the Harvard Film Archive has been screening Patricio Guzmán’s magisterial trilogy, The Battle of Chile, along with a program of Chilean cinema. I watched part I and II the last two nights and will watch part III tonight. It’s no secret that I am a huge fan of Guzmán’s work, and even quoted his beautiful film Nostalgia for the Light in the conclusion of my book Carceral Capitalism, when I wrote about the Chilean political prisoners who studied astronomy while incarcerated in the Atacama Desert. Bless Patricio Guzmán. This man has devoted his life and filmmaking career to the excavation of the Chilean soul.

Parts I and II utterly destroyed me. I left the theater last night shaken to my core, my face covered in tears.

The films are all the more remarkable when you consider it was made by a scrappy team of six people using film stock provided by the great documentarian Chris Marker. After the coup, four of the filmmakers were arrested. The footage was smuggled out of Chile and the exiled filmmakers completed the films in Cuba. Sadly, in 1974, the Pinochet regime disappeared cameraman Jorge Müller Silva, who is assumed dead.

It’s one thing to know the macro-story of what happened in Chile and quite another to see the view from the ground: the footage of the upswell of support for radical transformation, the marches, the street battles, the internal debates on the left about how to stop the fascist creep, the descent into chaos, the face of the military officer as he aims his pistol at the Argentine cameraman Leonard Hendrickson during the failed putsch of June 1973 (an ominous prelude to the September coup), the audio recordings of Allende on the morning of September 11, the bombing of Palacio de La Moneda—the military is closing in. Allende is dead. The crumbling edifice of the presidential palace becomes the rubble of revolutionary dreams—the bombs, a dirge for what was never even given a chance to live.

#Patricio Guzmán#film#Chile#history#salvador allende#socialism#marxism#coup#coup d'etat#The Battle of Chile#revolution#cinema#fascism#communism#geopolitics#political economy#Cold War#chris marker#memory#neoliberalism#capitalism#politics

97 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Source: Ashley D. Farmer - Remaking Black Power: How Black Women Transformed an Era (2017: 24)

“I was a slave. I was part of the “paper bag brigade,” waiting patiently in front of Woolworth’s on 170th St., between Jerome and Walton Aves., for someone to “buy” me for an hour or two, or, if I were lucky, for a day. That is the Bronx Slave Market, where Negro women wait, in rain or shine, in bitter cold or under broiling sun, to be hired by local housewives looking for bargains in human labor. It has its counterparts in Brighton Beach, Brownsville and other areas of the city. Born in the last depression, the Slave Markets are products of poverty and desperation. They grow as employment falls. Today they are growing. They arose after the 1939 [sic] crash when thousands of Negro women, who before then had a “corner” on household jobs because they were discriminated against in other employment, found themselves among the army of the unemployed. Either the employer was forced to do her own household chores or she fired the Negro worker to make way for a white worker who had been let out of less menial employment. The Negro domestic had no place to turn. She took to the streets in search of employment – and the Slave Markets were born.” - Marvel Cooke - “I Was Part of the Bronx Slave Market” [The Daily Compass, January 8th, 1950]

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fanthropologists Episode 17: Conventions & Political Economy

Happy anniversary! A year ago we uploaded our first episode, and over a year ago we sat in the hallway of a convention center considering conventions and political economy. In this episode you'll find discussions of conventions as spaces for people on the margins, gender dynamics in conventions, and the sound of a trash truck!

Listen to the episode here!

Next episode: October 6th

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

#neoliberalism#political economy#critical pedagogy#anti capitalism#neoliberal capitalism#karl marx#marxism#thoughts#quotes#twitter quotes#avocado toast#enjoy your latte in peace#responsibilization#individualism

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

A man sits in some museum somewhere and writes a harmless book about political economy and suddenly thousands of people who haven’t even read it are dying because the ones who did haven’t got the joke.

-- Terry Pratchett - The Last Continent

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

An excellently written article. A few snippets:

President Milei began his assault on the Argentine state immediately upon taking office last December. Right before Christmas, he signed a “megadecree,” or omnibus executive order, that deregulated significant parts of the economy. It reduced severance compensations and transferred workers from union-assigned health care to a voluntary system; lifted ceilings on rent, credit card interests, land tenure, and private health insurance plans; pushed the privatization of state-owned companies (“All government companies should close down,” Milei has explained); paved the way for unregulated international fishing, indiscriminate mining, and unsupervised tactical burning of forests. On December 29 he sent Congress a sweeping “ley ómnibus” with 664 articles. One of them would grant him emergency executive powers, allowing him to unilaterally rule on fiscal and pension matters for up to two years, without Congressional approval. In some three months Milei has also closed or weakened the ministries of education, labor, human rights, women, and the environment.

...

Disinvestment in social support leads to a perverse populist conclusion: social spending itself is the problem, not that the spending isn't high enough.

It's a common criticism, justified in my view, that conservative voters often vote against their own self-interest. (I don't mean to imply by contrast that voting for the Dems is a panacea by any means.) In Strangers in Their Own Land - Anger and Mourning on the American Right, Arlie Russell Hochschild examines specific individual cases of working and middle class voters who, despite living in a polluted environment with high cancer rates, nevertheless arrive at the conclusion that we have to abolish the Environmental Protection Agency.

Through a combination of cynical intuition and programmatic dishonesty to hide their actual motives, Republicans routinely propose cuts to, among other things, Social Security and Medicare, in the hope that voters will blame these programs for being insufficient, forget that the insufficiency has actual perpetrators, and will then be amenable to free market "solutions."

A similar or identical logic seems to be at work in Argentina, and with predictable results:

Voters also became increasingly ambivalent about the benefits of the welfare state as its effectiveness dwindled. For most of the second half of the twentieth century, Argentina’s literacy rate was close to 95 percent, supported by a massive public education system. Today, for every hundred students who enter public primary school, only forty-six graduate passing the Pruebas Aprender—a standardized test in mathematics and Spanish. Just half make it to the end of high school, and a paltry sixteen pass the version of the test designed for that stage. Public hospitals were once the gems of the Argentine welfare state. As the middle and upper-middle classes absconded to the private system, however, the quality of care declined. Today half of lower-income patients have not visited a doctor in a year; those who do face waits two or three times longer than those in the private health care system. “Most of those funding public goods have abandoned them a long time ago,” the sociologists Javier Auyero and Sofia Servián have argued. “Those who use them feel them broken and shattered.”

...

The libertarian "free market" inevitably requires a great deal of coercion and the abrogation of basic rights. So, it's not surprising that a kind of moral inversion appears, a political transubstantiation where actual sources of oppression are transformed into victims, and the efforts to alleviate immiseration are vilified.

Even as he rails against the political caste, Milei has been careful to support the military. His vice president, Victoria Villarruel, is the granddaughter, daughter, and niece of members of the armed forces. Her uncle, the intelligence officer Ernesto Villarruel, worked at the clandestine detention center El Vesubio during the military dictatorship. Villarruel herself has set up the Center for Legal Studies on Terrorism and its Victims, which called for the release of many military figures imprisoned for torture, assassinations, and kidnappings. It’s an intervention that effectively redefines human rights. Villarruel presents “urban crime, state negligence or corruption, and traffic accidents” as human rights violations on par with the military’s crimes, Verónica Torras, executive director of the human rights organization Memoria Abierta, told me. “At the same time…[the government] moves towards an increasing criminalization of social and economic rights.”

Much more at the link (unfortunately behind a paywall).

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Instead of imagining a world without work that will never come to pass, we should examine the ways historical struggles posited an alternative relationship to work and liberation, where control over the labor process leads to greater control over other social processes, and where the ends of work are human enrichment rather than abstract productivity. furthermore, these struggles point toward the only vehicle for a liberation from capitalism: the composition of a militant struggling class that attacks capital in all its manifold domination, including the technological".

Breaking Things at Work: The Luddites Are Right About Why You Hate Your Job by Gavin Mueller

#book quotes#currently reading#capitalism#luddism#political economy#breaking things at work#gavin mueller#history#political history#labor#labor relations#class struggle#marxism#technology#politics#verso books#book rec#nonfiction#r/#book recommendations#writings

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

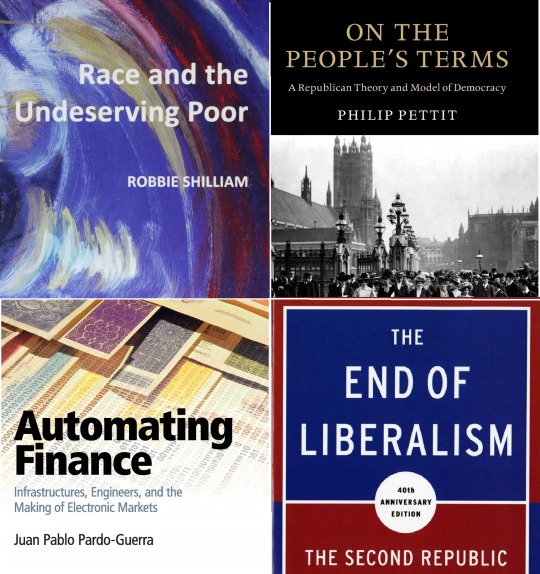

Read very interesting readings and recorded talks on various topics in Economic Sociology and Political Economy: The Administrative State | Automating Finance | Dependency Theory | Youth Unemployment | Spatial inequality | Fukuyama | More

10 notes

·

View notes

Note

Why do economists need to shut up about mercantilism, as you alluded to in your post about Louis XIV's chief ministers?

In part due to their supposed intellectual descent from Adam Smith and the other classical economists, contemporary economists are pretty uniformly hostile to mercantilism, seeing it as a wrong-headed political economy that held back human progress until it was replaced by that best of all ideas: capitalism.

As a student of economic history and the history of political economy, I find that economists generally have a pretty poor understanding of what mercantilists actually believed and what economic policies they actually supported. In reality, a lot of the things that economists see as key advances in the creation of capitalism - the invention of the joint-stock company, the creation of financial markets, etc. - were all accomplishments of mercantiism.

Rather than the crude stereotype of mercantilists as a bunch of monetary weirdos who thought the secret to prosperity was the hoarding of precious metals, mercantilists were actually lazer-focused on economic development. The whole business about trying to achieve a positive balance of trade and financial liquidity and restraining wages was all a means to an end of economic development. Trade surpluses could be invested in manufacturing and shipping, gold reserves played an important role in deepening capital pools and thus increasing levels of investment at lower interest rates that could support larger-scale and more capital intensive enterprises, and so forth.

Indeed, the arch-sin of mercantilism in the eyes of classical and contemporary economists, their interference in free trade through tariffs, monopolies, and other interventions, was all directed at the overriding economic goal of climbing the value-added ladder.

Thus, England (and later Britain) put a tariff on foreign textiles and an export tax on raw wool and forbade the emigration of skilled workers (while supporting the immigration of skilled workers to England) and other mercantilist policies to move up from being exporters of raw wool (which meant that most of the profits from the higher value-added part of the industry went to Burgundy) to being exporters of cheap wool cloth to being exporters of more advanced textiles. Hell, even Adam Smith saw the logic of the Navigation Acts!

And this is what brings me to the most devastating critique of the standard economist narrative about mercantilism: the majority of the countries that successfully industrialized did so using mercantilist principles rather than laissez-faire principles:

When England became the first industrial economy, it did so under strict protectionist policies and only converted to free trade once it had gained enough of a technological and economic advantage over its competitors that it didn't need protectionism any more.

When the United States industrialized in the 19th century and transformed itself into the largest economy in the world, it did so from behind high tariff walls.

When Germany made itself the leading industrial power on the Continent, it did so by rejecting English free trade economics and having the state invest heavily in coal, steel, and railroads. Free trade was only for within the Zollverein, not with the outside world.

And as Dani Rodrik, Ha-Joon Chang, and others have pointed out, you see the same thing with Japan, South Korea, China...everywhere you look, you see protectionism as the means of achieving economic development, and then free trade only working for already-developed economies.

#political economy#mercantilism#economic development#early modern state-building#early modern period#laissez-faire#classical liberalism#classical economics#economics#economic history

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

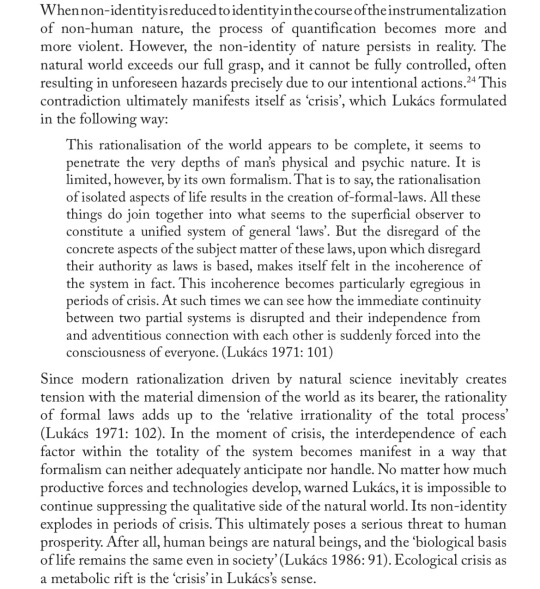

—Kohei Saito, Marx in the Anthropocene: Toward the Idea of Degrowth Communism

See “solastalgia”, a term coined by an Australian philosopher to “describe the existential melancholy induced by environmental change.”

Apparently geologists will soon vote on whether to accept the claim that we are in the geological epoch known as the Anthropocene.

“The AWG [Anthropocene Working Group] will present a proposal to make the Anthropocene official to the Subcommission on Quaternary Stratigraphy later this summer. If the subcommission’s members agree with a 60% majority, the proposal will then pass on to the International Commission on Stratigraphy, which will also have to vote and agree with a 60% majority for the proposal to move onward for ratification.” What will be the outcome of the vote?

#political philosophy#philosophy#kohei saito#marx#marxism#communism#anthropocene#capitalocene#ecology#environment#solastalgia#capitalism#political economy#theory#metabolic rift#Lukács

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

we know rhat nonviolence will never work in place of revolution, not just from modern protests and their ineffectiveness, but all of history as a whole. there is no way you can “peacefully”conduct social revolution. even on a non-scientific approach, do you really think you’ll get the bourgeoies to enforce proletarian policies that actively destroy their class with vandalism and mean words? the only reason we have so-called “humane capitalism” certain countries ( i.e social democracy) is because of revolution in other countries! read a book.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Historical Materialism Course

I've spent years reading and watching things about history. Eventually I decided to compile all the useful things I've watched into a course for history from a Marxist perspective. Of course I'm limited to what videos I can find, so not everything is covered as well as I'd like, and many videos are made by liberals or even reactionaries, who may make an important point in the video, but leave out important further context. That said, I feel like video documentaries are how a lot of younger people absorb history now, so we might as well compile resources that are actually good for them.

I've broken up the videos into a series of playlists covering various periods of history. It goes from the beginning of the universe to the beginning of the Cold War. (Cold War history from a socialist perspective is so complicated and full of misinformation that at that point you really just have to delve into the books and primary sources yourself. Summary videos won't suffice.)

#history#historical materialism#dialectical materialism#revolutionary history#class struggle#Marxist theory#Marxism#communism#socialism#capitalism#feudalism#economics#economic history#archaeology#anthropology#sociology#political science#political economy#Marx#Youtube#education#dialectics#complexity theory#complex systems#Bronze Age#Iron Age#Stone Age#colonialism#imperialism#settler-colonialism

24 notes

·

View notes

Quote

I didn’t leap at all! I was a worker, yes, but to me I was a writer who had a job as a worker. I said to myself, “Ooh la la, what a learning opportunity.” It was very important for me to be a worker. I worked at a radio station in Haiti as well, and I also had a very small salary from Petit samedi soir, a newspaper there. In fact, they didn’t pay us in money, they gave us copies of the paper that we had to sell ourselves in order to be paid. I found a guy to sell them for me and we split the proceeds. I guess I have a strange rapport with money. The worst job I ever had in Haiti was at a bank. I had no idea what a bank even was. Banks are wary of poor people; I was the opposite. So I quickly gained a reputation among poor people and prostitutes as the cashier to see. There was always a lineup of people to meet with me because they’d heard that I didn’t need to see any paperwork. My guiding principle was that poor people don’t cheat. It wasn’t a romantic idea—it’s simply too complicated for them to cheat, they can’t cheat a bank. Only rich people can cheat the bank. And in the whole time I worked at the bank, I never had a single problem, or bounced check, or bad deposit. They would come and deposit or withdraw their tiny sums with their bank book. All the prostitutes from the crossroads would come see me to send money to the Dominican Republic to their families and children. Those people never cheated. But because I wasn’t a good banker, I never managed to balance my own numbers. It always took me so long that I’d end up going home late in the evenings, well after everybody else had checked out. As a result, they had to pay me overtime for those extra hours, so I ended up making almost as much money as the bank’s director. All because they didn’t understand how incompetent I was. Finally, somebody realized that it was my own fault, so they stopped paying me overages. But it was an early example of my relationship with money. If you don’t know how to do things properly, I learned, you will be paid better than those who know how to do it and who will go home on time.

Dany Laferriere

Adam Leith Gollner - Working in the Bathtub: Conversations with the Immortal Dany Laferière (2020)

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

People who say "X job is for teenagers, that's why it shouldn't pay a living wage" sound exactly like nineteenth century British factory owners who quite literally said "this new machine we have doesn't really require a full grown man to operate it, so we can fire him and get a teenager to work with it instead and pay them only a fraction of the adult salary".

#source - The Capital fourth edition volume 1. chapter thirteen. parts 3 and 4 (but it's also all over the place there)#(apparently it's chapter fifteen in the english edition? I'm a bit confused)#so I guess it's okay to tag it as#karl marx#marxism#communism#socialism#?#what are tumblr tags for political theory?#political economy#???#this looks unnatural here

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

60 notes

·

View notes