#piqueteros

Text

ça nous pique partout sauf dans la mémoire

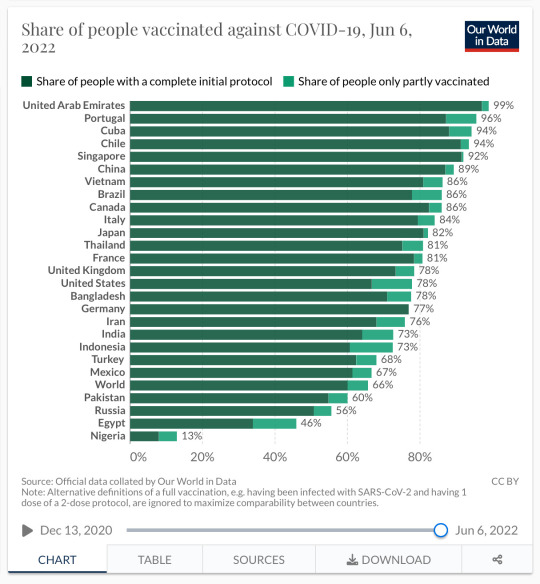

Cuba et le Chili ont administré en moyenne 3,3 doses par ciudadano. Le Canada (eh?) se tient à 2,2 doses par tête de pipe, les USA à 1,7 doses par obèse morbide. Et Schwab, Gates, Bourla et autres von der Leyen saints patientent.

VTFF, pétasse ripouse.

#johns hopkins university#stats officielles sur Piqouze 2.0 le nouveau logiciel de bill wtf gates#big pharma est toujours en bonne santé#piqueteros

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

El país que nos están dejando, "Piqueteros" cortando rutas y "Barras brava" abriendo el paso a los tiros, en medio de ese quilombo los pobres ciudadanos que debe concurrir a laburar por un sueldo de miseria

Ocurrió en ruta nacional 11 a la altura de la localidad de Tacuarendí.

No cabe más que decir políticos del "Orto", son una basura, no pueden manejar ni un triciclo, mándense a mudar por el bien de la gente...

#Piqueteros#Barra bravas#politicos#gente#ciudadanos#sueldo de hambre#Argentina fundida#mala gente#triciclo#manejar#basura#orto

0 notes

Photo

Tras su renuncia, Gustavo Beliz participó de una misa en la Basílica de Luján junto a los piqueteros oficialistas que piden “pan, tierra, techo y trabajo”

0 notes

Text

Ocho mitos sobre los movimientos sociales

Prácticamente desde su nacimiento, en 1996, el movimiento piquetero viene sufriendo un sinnúmero de acusaciones y ataques propinados desde el Estado y amplificados a través de los grandes medios de comunicación. Como un “deja vu” recurrente, las organizaciones sociales se ven expuestas a todo tipo de operaciones mediáticas que buscan deslegitimar y estigmatizar a los sectores desocupados o precarizados que se vienen organizando y luchando contra los altos niveles de exclusión y marginación a los que se los somete. Repasamos ocho mitos que, tras el discurso de la vicepresidenta Cristina Fernández de la semana pasada, volvieron a aflorar en la dirigencia política y las grandes empresas de la comunicación que construyen la agenda política local.

Mito 1: “Los piqueteros no trabajan, son vagos”

Las primeras puebladas que dieron surgimiento a las organizaciones sociales eran claras en su demanda: se le exigía al Estado trabajo genuino. El mismo que se les había arrebatado a partir de las privatizaciones y el desguace de las empresas públicas. La respuesta de los distintos gobiernos será otorgar programas de empleo, los cuales carecían de gran parte de los derechos fijados en los convenios colectivos de trabajo, así como salarios ubicados muy por debajo de la línea de pobreza.

Con esos planes y a lo largo de estos años, las organizaciones han puesto de pie cuadrillas de trabajo y productivos de todo tipo (herrerías, carpinterías, bloqueras y costuras, entre otros). Estos emprendimientos no solo han garantizado un empleo a cientos de miles de familias sino que además logran prestar servicios a barrios, villas y asentamientos donde el Estado solo se hace presente con la policía. Todas estas iniciativas se llevan a cabo sin bajar las banderas de trabajo genuino.

El reporte de agosto del año pasado del Registro Nacional de Trabajadores y Trabajadoras de la Economía Popular (ReNaTEP) mostró una radiografía de los oficios, género y tipo de organización que asumen unas 2.830.520 de personas que se inscribieron entre julio del 2020 y el 11 de agosto del 2021. El relevamiento segmenta los oficios en varias categorías que engloban distintas actividades. La más preponderante que se refleja con precisión es la concerniente a trabajador/a de comedores y merenderos comunitarios que contiene a 444.440 personas, de las cuales el 62,8% son mujeres y el 37,2% varones. “Servicios de limpieza” es otra de las actividades relevantes con 177.887 (el 88% son mujeres y 12% varones) y el tercero del podio es “agricultor/a” con 111.618(repartido en 46,9% mujeres y 53,1% varones) .

Foto: Télam.

Mito 2: “Les pagan por movilizar”

Este mito de antaño cae bajo su propio peso si se analiza, por ejemplo, la cantidad de personas que vienen movilizando el último tiempo. Solo la Unidad Piquetera ha movilizado a 300 mil personas en la última marcha federal.

Hagamos un ejercicio práctico, si a cada persona se le pagara $5000 para marchar estaríamos hablando de un gasto por movilización de $1500.000.000, cifra imposible de manejar para los movimientos y más aún si se la multiplica por la decena de marchas y concentraciones que se viene haciendo en el año.

Además, se niega una situación fundacional de las organizaciones y que tiene que ver que la gente se moviliza y lucha no solo por su situación de pobreza o desempleo sino también porque sabe que solo a través de la lucha puede llegar a percibir al menos un plan social. Desde los inicios de los programas de empleo, el Estado negó la universalización de dicho recurso ya que se utiliza como contención de conflictos puntuales. Difícilmente una persona de manera individual vaya a un ministerio, golpee una puerta y le den un beneficio solo por estar desocupada o ser pobre.

Mito 3: «Le sacan plata a la gente»

Al igual que lo hizo el gobierno de Eduardo Duhalde, la vicepresidenta Cristina Fernández y La Cámpora han montado una ofensiva aduciendo que las organizaciones se quedan con plata de la gente.

Se refieren a los aportes voluntarios que cada familia da al interior de la organización para sostener lo que el Estado no sostiene, como son los fletes, alquileres de locales, mantenimiento de las cooperativas, verduras para los comedores, ropa de trabajo y herramientas, entre otros elementos.

¿Cómo pretende Cristina que lleguen los alimentos a los barrios si no es con el pago de un flete? ¿Si el Estado solo manda polenta y salsa de tomate, como se piensa que debe garantizarse el servicio de los comedores populares? El mismo Estado que deja a la deriva a las personas, les cuestiona que se organicen para resolver sus problemas.

A su vez, existe en este planteo una connotación clasista, ya que dicha objeción no corre la misma suerte para con los militantes de La Cámpora que aportan un porcentaje de su salario por trabajar en el Estado o no pone en cuestión el diezmo de las iglesias. Cualquier organización de la sociedad civil que pretenda tener autonomía en sus decisiones debe tener autonomía financiera. Negar eso es ir contra la historia organizativa de la clase obrera.

Foto: Franco Fafasuli.

Mito 4: «Un beneficiario de un programa de trabajo cobra más de 100 mil pesos»

Este mito cae por su propio peso con los datos objetivos de los programas de empleo. En el caso del Potenciar Trabajo, que es la referencia principal de los planes, el monto que se cobra es de $19.000, cuestión que se rige en base a cómo evoluciona las definiciones del Consejo del Salario.

Incluso sumándole los ingresos por otras prestaciones sociales (como puede ser la Asignación Universal por Hijo), lo montos no llegan ni al 50% de lo que se plantea en el imaginario social.

Mito 5: «Nadie controla los recursos de las organizaciones sociales»

Esto es una mentira abierta e injustificable. Cada recurso que reciben las cooperativas de las organizaciones sociales deben ser justificados y rendidos en tiempo y forma.

En la actualidad, y a lo largo de la historia, el Estado tiene la plena potestad de hacer auditorías (y de hecho las ha hecho) que confirmen el destino de los recursos que transfiere a movimientos, municipios o asociaciones civiles.

Mito 6: «El programa de empleo es un subsidio y no un trabajo»

Este planteo surgió en las últimas semanas a partir de la arremetida de un sector del gobierno contra las organizaciones. Es falso y queda demostrado al calor de las distintas experiencias laborales que surgieron en las organizaciones sociales y de la contraprestación misma que se exige para percibir dicha remuneración.

Tal planteo además es realizado por los mismos funcionarios que avalan e impulsan que en las mediciones de los índices de desocupación se contabilicen los planes como empleo. De hecho, tal perspectiva le permitió al gobierno de Cristina Fernández en 2015 afirmar que Resistencia, Chaco, gozaba de pleno empleo.

Imagen: Télam.

Mito 7: «Los pobres, y más aún las mujeres, son usadas y explotadas en las organizaciones»

La vicepresidenta Cristina Fernández se refirió en estos términos a las personas que habitan las organizaciones. Desconoce, o prefiere omitir, que fueron las mismas mujeres las que pusieron de pie de las organizaciones, las que las sostienen y se ponen a la cabeza de la lucha.

Históricamente las asambleas barriales de las organizaciones han dado voz y lugar que las instituciones del Estado les niegan. De todas formas, no se puede negar la existencia de prácticas patriarcales en el seno de las organizaciones, las cuales no difieren de las existentes en todo tipo de organización de la sociedad civil.

El planteo realizado por Cristina Fernández niega la historia de construcción de un feminismo piquetero que tuvo uno de sus hitos en las asambleas de mujeres del Puente Pueyrredón en 2003, la existencia de comisiones de género en el grueso de los movimientos, o las cuadrillas de género que abordan a diario las situaciones de violencias, esas que el Estado define omitir.

Mito 8: «Con la intervención de la Anses y los intendentes se garantiza la transparencia»

El cobro del salario que implica el programa de empleo se hace a través de una tarjeta directamente a las personas “beneficiarias”, por lo que no hay mediación de las organizaciones en dichos fondos. El planteo que se pague a través de la Anses no modifica en nada la situación metodológica del cobro y lo que se expresa en definitiva es una disputa de la caja en cuestión.

En paralelo, se intenta “transparentar” la situación transfiriendo la organización del trabajo a los intendentes y gobernadores. Vayamos a un ejemplo concreto. Durante el gobierno de Duhalde existieron unas 800 denuncias penales por irregularidades en los manejos de los planes “Jefes y jefas de Hogar” entre abril de 2002 y octubre de 2003. Lo paradójico es que las presentaciones judiciales no apuntaban a las organizaciones sociales sino que recaían en su totalidad contra intendentes, funcionarios municipales, concejales y miembros de consejos consultivos impulsados por el propio gobierno. Tal situación será admitida por el propio Duhalde años después.

La implementación del plan “Argentina Trabaja”, durante el gobierno de Cristina Fernández, resultó ser otra muestra de este tipo de irregularidades ya que afloraron denuncias por doquier contra intendentes y punteros ligados al aparato municipal. Los jefes comunales sobreexplotaban a las personas “beneficiarias” y desviaban constantemente los fondos correspondientes a la compra de herramientas e insumos para garantizar dichos trabajos.

Detrás de esta propuesta se encuentra la intención de devolverle poder territorial a los punteros y al aparato del Partido Justicialista que fueron perdiendo en la disputa con las organizaciones sociales desde 1996 a esta parte. Además se busca que los municipios realicen un fraude laboral disponiendo de mano de obra precarizada por fuera de los convenios municipales.

“La economía precarizada: ¿quiénes, dónde y de qué trabajan las casi tres millones de familias inscriptas en el ReNaTEP?”, Anred. Edición del 30/09/2021.

:::Nicolas Salas para ANRed:::

Read the full article

0 notes

Text

La falopa política del día:

Petovello, la ministra de "capital humano" (si Oceanía de 1984 viera eso diría "che paren un poco") y reikista, parece que quiere renunciar, aparentemente tuvo un brote de nervios después de una discusión con Caputo y ahora les dijo a los jefes piqueteros que vayan a marchar a la plaza y le pidan a él plata para los comedores. kinda based ngl. No puedo imaginar la reacción en LLA. Renuncia inminente.

Mientras el gobierno austero de Milei sigue poniendo más "expertos en comunicaciones" (o sea jefes de trolls en redes sociales, algunos como el inútil de John Doe de twitter) con sueldos millonarios, Iñaki, el libertario troll original, está atrincherado en su oficina en Casa Rosada, se rehúsa a que lo echen. Caputo analiza llamar a la policía.

Macri está presionando para quedarse con el PRO y poner ministros en el gobierno. Su mayor contrincante es Karina Milei que quiere poner a su gente. Mucho bardo, pero basta que sepan que Macri le dice "tarotista vende tortas" y que "no le va a poner los puntos".

Villarruel, la vicepresidenta, se reunió con gobernadores aliados en Salta y les dijo que apoyen a Macri. Todo parece indicar que está queriendo tomar el poder con Macri si cae Milei.

A todo esto, Milei está adicto a Twitter y se desconoce que está haciendo, exactamente. Aparemente está en delirios de dolarizar con Caputo y solamente habla con la hermana. Muy Fuhrerbunker todo.

Bueno, aparte de la vez que se reunió con Marco Rubio de EEUU con una foto ridícula donde parece un gnomo.

Todo parece indicar que Argentina ya no va a una recesión, sino a una depresión para marzo y abril. No les voy a hablar de esto porque lo pueden ver en la calle.

Todo lo de arriba pasó en el transcurso de ayer y hoy.

Al momento de este post, la presidencia de Javier Milei lleva 2 meses y 11 días. *click*

133 notes

·

View notes

Text

"hay que dejar gobernar" mira pedazo de catador de leche, no me están dejando vivir, te van a romper el orto y siempre somos nosotros los ~piqueteros marrones~ los que tenemos que salvarte a vos, desclasado de mierda.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapter 6. Revolution

How will a common, anti-authoritarian, ecological ethos come about?

In the long run, an anarchist society will work best if it develops a culture that values cooperation, autonomy, and environmentally sustainable behaviors. The way a society is structured can encourage or hinder such an ethos, just as our current society rewards competitive, oppressive, and polluting behaviors and discourages anti-authoritarian ones. In a non-coercive society, social structures cannot force people to live in accordance with anarchist values: people have to want to do so, and personally identify with such values themselves. Fortunately, the act of rebelling against an authoritarian, capitalist culture can itself popularize anti-authoritarian values.

Anarchist anthropologist David Graeber writes of the Tsimihety in Madagascar, who rebelled and removed themselves from the Maroansetra dynasty. Even over a century after this rebellion, the Tsimihety “are marked by resolutely egalitarian social organization and practices,” to such an extent that it defines their very identity.[107] The new name the tribe chose for themselves, Tsimihety, means “those who do not cut their hair,” in reference to the custom of subjects of the Maroansetra to cut their hair as a sign of submission.

During the Spanish Civil War in 1936, a number of cultural changes took place. In the countryside, politically active youth played a leading role in challenging conservative customs and pushing their villages to adopt an anarchist-communist culture. The position of women in particular began to change rapidly. Women organized the anarcha-feminist group Mujeres Libres to help accomplish the goals of the revolution and ensure that women enjoyed a place at the forefront of the struggle. Women fought on the front, literally, joining the anarchist militias to hold the line against the fascists. Mujeres Libres organized firearms courses, schools, childcare programs, and women-only social groups to help women gain the skills they needed to participate in the struggle as equals. Members of Mujeres Libres argued with their male comrades, emphasizing the importance of women’s liberation as a necessary part of any revolutionary struggle. It was not a minor concern to be dealt with after the defeat of fascism.

In the cities of Catalunya, social restrictions on women lessened considerably. For the first time in Spain, women could walk alone on the streets without a chaperon — not to mention that many were walking down the streets wearing militia uniforms and carrying guns. Anarchist women like Lucia Sanchez Saornil wrote about how empowering it was for them to change the culture that had oppressed them. Male observers from George Orwell to Franz Borkenau remarked on the changed conditions of women in Spain.

In the uprising spurred by Argentina’s economic collapse in 2001, participation in the popular assemblies helped formerly apolitical people build an anti-authoritarian culture. Another form of popular resistance, the piquetero movement, exerted a great influence on the lives and culture of many of the unemployed. The piqueteros were unemployed people who masked their faces and set up pickets, shutting down the highways to cut off trade and gain leverage for demands such as food from supermarkets or unemployment subsidies. Aside from these activities, the piqueteros also self-organized an anti-capitalist economy, including schools, media groups, clothing give-away shops, bakeries, clinics, and groups to fix up people’s houses and build infrastructure such as sewage systems. Many of the piquetero groups were affiliated with the Movement of Unemployed Workers (MTD). Their movement had already developed considerably before the December 2001 run on the banks by the middle class, and in many ways they were at the forefront of the struggle in Argentina.

Two Indymedia volunteers who traveled to Argentina from the US and Britain to document the rebellion for English-speaking countries spent time with a group in the Admiralte Brown neighborhood south of Buenos Aires.[108] The members of this particular group, similar to many of the piqueteros in the MTD, had been driven to activism only recently, by unemployment. But their motivations were not purely material; for example, they frequently held cultural and educational events. The two Indymedia activists recounted a workshop held in an MTD bakery, in which the collective members discussed the differences between a capitalist bakery and an anti-capitalist one. “We produce for our neighbors... and to teach ourselves to do new things, to learn to produce for ourselves,” explained a woman in her fifties. A young man in an Iron Maiden sweatshirt added, “We produce so that everyone can live better.”[109] The same group operated a Ropero, a clothing shop, and many other projects as well. It was run by volunteers and depended on donations, even though everyone in the area was poor. Despite these challenges, it opened twice a month to give out free clothes to people who could not afford them. The rest of the time, the volunteers mended old clothes that were dropped off. In the absence of the motives that drive the capitalist system, the people there clearly took pride in their work, showing off to visitors how well restored the clothes were despite the scarcity of materials.

The shared ideal among the piqueteros included a firm commitment to non-hierarchical forms of organization and participation by all members, young and old, in their discussions and activities. Women were often the first to go to the picket lines, and came to hold considerable power within the piquetero movement. Within these autonomous organizations, many women gained the opportunity to participate in large-scale decision-making or take on other male-dominated roles for the first time in their lives. At the particular bakery holding the workshop described above, a young woman was in charge of security, another traditionally male role.

Throughout the 2006 rebellion in Oaxaca, as well as before and after, indigenous culture was a wellspring of resistance. However much they exemplified cooperative, anti-authoritarian, and ecologically sustainable behaviors before colonialism, indigenous peoples in the Oaxacan resistance came to cherish and emphasize the parts of their culture that contrasted with the system that values property over life, encourages competition and domination, and exploits the environment into extinction. Their ability to practice an anti-authoritarian and ecological culture — working together in a spirit of solidarity and nourishing themselves on the small amount of land they had — increased the potency of their resistance, and thus their very chances for survival. Thus, resistance to capitalism and the state is both a means of protecting indigenous cultures and a crucible that forges a stronger anti-authoritarian ethos. Many of the people who participated in the rebellion were not themselves indigenous, but they were influenced and inspired by indigenous culture. Thus, the act of rebellion itself allowed people to choose social values and shape their own identities.

Before the rebellion, the impoverished state of Oaxaca sold its indigenous culture as a commodity to entice tourists and bring in business. The Guelaguetza, an important gathering in native cultures, had become a state-sponsored tourist attraction. But during the rebellion in 2006, the state and tourism were pushed to the margins, and in July the social movements organized a People’s Guelaguetza — not to sell to the tourists, but to enjoy for themselves. After successfully blocking the commercial event set up for the tourists, hundreds of students from Oaxaca City and people from villages across the state began organizing their own event. They made costumes and practiced dances and songs from all seven regions of Oaxaca. In the end the People’s Guelaguetza was a huge success. Everyone attended for free and the venue was packed. There were more traditional dances than there had ever been in the commerical Guelaguetzas. While the event had previously been performed for money, most of which was pocketed by the sponsors and government, it became a day of sharing, as it had been traditionally. At the heart of an anti-capitalist, largely indigenous movement was a festival, a celebration of the values that hold the movement together, and a revival of indigenous cultures that were being wiped out or pared down to a marketable exoticism.

While the Guelaguetza was reclaimed as a part of indigenous culture in support of an anti-capitalist rebellion and the liberatory society it sought to create, another traditional celebration was modified to serve the movement. In 2006 the Day of the Dead, a Mexican holiday that syncretizes indigenous spirituality with Catholic influences, coincided with a violent government assault upon the movement. Just before the 1st of November, police forces and paramilitaries killed about a dozen people, so the dead were fresh in everybody’s minds. Graffiti artists had long played an important role in the movement in Oaxaca, covering the walls with messages well before the people had seized radio stations to give themselves a voice. When the Day of the Dead and the heavy government repression coincided in November, these artists took the lead in adapting the holiday to commemorate the dead and honor the struggle. They covered the streets with the traditional tapetes — colorful murals made from sand, chalk, and flowers — but this time the tapetes contained messages of resistance and hope, or portrayed the names and faces of all the people killed. People also made skeleton sculptures and altars for each person murdered by police and paramilitaries. One graffiti artist, Yescka, described it:

This year on Day of the Dead, the traditional festivities took on new meaning. The intimidating presence of the Federal Police troops filled the air — an atmosphere of sadness and chaos hung over the city. But we managed to overcome our fear and our loss. People wanted to carry on with the traditions, not only for their ancestors, but also for all those fallen in the movement in recent months.

Although it sounds a bit contradictory, Day of the Dead is when there is the most life in Oaxaca. There are carnivals, and people dress up in different costumes, such as devils or skeletons full of colorful feathers. They parade through the streets dancing or creating theatrical performances of comical daily happenings — this year with a socio-political twist.

We didn’t let the Federal Police forces standing guard stop our celebrating or our mourning. The whole tourist pathway in the center of the city, Macedonio Alcalá, was full of life. Protest music was playing and people danced and watched the creation of our famous sand murals, called tapetes.

We dedicated them to all the people killed in the movement. Anyone who wanted to could join in to add to the mosaics. The mixed colors expressed our mixed feelings of repression and freedom; joy and sadness; hatred and love. The artwork and the chants permeating the street created an unforgettable scene that ultimately transformed our sadness into joy.[110]

While artwork and traditional festivals played a role in the development of a liberating culture, the struggle itself, specifically the barricades, provided a meeting point where alienation was shed and neighbors built new relationships. One woman described her experience:

You found all kinds of people at the barricades. A lot of people tell us they met at the barricades. Even though they were neighbors, they didn’t know each other before. They’ll even say, “I didn’t ever talk to my neighbor before because I didn’t think I liked him, but now that we’re at the barricade together, he’s a compañero.” So the barricades weren’t just traffic barriers, but became spaces where neighbors could chat and communities could meet. Barricades became a way that communities empowered themselves.[111]

Throughout Europe, dozens of autonomous villages have built a life outside capitalism. Especially in Italy, France, and Spain, these villages exist outside regular state control and with little influence from the logic of the market. Sometimes buying cheap land, often squatting abandoned villages, these new autonomous communities create the infrastructure for a libertarian, communal life and the culture that goes with it. These new cultures replace the nuclear family with a much broader, more inclusive and flexible family united by affinity and consensual love rather than bloodlines and proprietary love; they destroy the division of labor by gender, weaken age segregation and hierarchy, and create communal and ecological values and relationships.

A particularly remarkable network of autonomous villages can be found in the mountains around Itoiz, in Navarra, part of the Basque country. The oldest of these, Lakabe, has been occupied for twenty-eight years as of this writing, and is home to about thirty people. A project of love, Lakabe challenges and changes the traditional aesthetic of rural poverty. The floors and walkways are beautiful mosaics of stone and tile, and the newest house to be built there could pass for the luxury retreat of a millionaire — except that it was built by the people who live there, and designed in harmony with the environment, to catch the sun and keep out the cold. Lakabe houses a communal bakery and a communal dining room, which on a normal day hosts delicious feasts that the whole village eats together.

Another of the villages around Itoiz, Aritzkuren, exemplifies a certain aesthetic that represents another idea of history. Thirteen years ago, a handful of people occupied the village, which had been abandoned for over fifty years before that. Since then, they have constructed all their dwellings within the ruins of the old hamlet. Half of Aritzkuren is still ruins, slowly decomposing into forest on a mountainside an hour’s drive from the nearest paved road. The ruins are a reminder of the origin and foundation of the living parts of the village, and they serve as storage spaces for building materials that will be used to renovate the rest of it. The new sense of history that lives amidst these piled stones is neither linear nor amnesiac, but organic — in that the past is the shell of the present and compost of the future. It is also post-capitalist, suggesting a return to the land and the creation of a new society in the ruins of the old.

Uli, another of the abandoned and reoccupied villages, disbanded after more than a decade of autonomous existence; but the success rate of all the villages together is encouraging, with five out of six still going strong. The “failure” of Uli demonstrates another advantage of anarchist organizing: a collective can dissolve itself rather than remaining stuck in a mistake forever or suppressing individual needs to perpetuate an artificial collectivity. These villages in their prior incarnations, a century earlier, were only dissolved by the economic catastrophe of industrializing capitalism. Otherwise, their members were held fast by a conservative kinship system rigidly enforced by the church.

At Aritzkuren as at other autonomous villages throughout the world, life is both laborious and relaxed. The residents must build all their infrastructure themselves and create most of the things they need with their own hands, so there is plenty of work to do. People get up in the morning and work on their own projects, or else everyone comes together for a collective effort decided on at a previous meeting. Following a huge lunch which one person cooks for everyone on a rotating basis, people have the whole afternoon to relax, read, go into town, work in the garden, or fix up a building. Some days, nobody works at all; if one person decides to skip a day, there are no recriminations, because there are meetings at which to make sure responsibilities are evenly distributed. In this context, characterized by a close connection to nature, inviolable individual freedom mixed with a collective social life, and the blurring of work and pleasure, the people of Aritzkuren have created not only a new lifestyle, but an ethos compatible with living in an anarchist society.

The school they are building at Aritzkuren is a powerful symbol of this. A number of children live at Aritzkuren and the other villages. Their environment already provides a wealth of learning opportunities, but there is much desire for a formal educational setting and a chance to employ alternative teaching methods in a project that can be accessible to children from the entire region.

As the school indicates, the autonomous villages violate the stereotype of the hippy commune as an escapist attempt to create a utopia in microcosm rather than change the existing world. Despite their physical isolation, these villages are very much involved in the outside world and in social movements struggling to change it. The residents share their experiences in creating sustainable collectives with other anarchist and autonomous collectives throughout the country. Many people divide each year between the village and the city, balancing a more utopian existence with participation in ongoing struggles. The villages also serve as a refuge for activists taking a break from stressful city life. Many of the villages carry on projects that keep them involved in social struggles; for example, one autonomous village in Italy provides a peaceful setting for a group that translates radical texts. Likewise, the villages around Itoiz have been a major part of the twenty-year-running resistance to the hydroelectric dam there.

For about ten years, starting with the occupation of Rala, near Aritzkuren, the autonomous villages around Itoiz have created a network, sharing tools, materials, expertise, food, seeds, and other resources. They meet periodically to discuss mutual aid and common projects; residents of one village will drop by another to eat lunch, talk, and, perhaps, deliver a dozen extra raspberry plants. They also participate in annual gatherings that bring together autonomous communities from all over Spain to discuss the process of building sustainable collectives. At these, each group presents a problem it has been unable to resolve, such as sharing responsibilities or putting consensus decisions into practice. Then they each offer to mediate while another collective discusses their problem — preferably a problem the mediating group has experience resolving.

The Itoiz villages are remarkable, but not unique. To the east, in the Pyrenees of Aragon, the mountains of La Solana contain nearly twenty abandoned villages. As of this writing, seven of these villages have been reoccupied. The network between them is still in an informal stage, and many of the villages are only inhabited by a few people at an early point in the process of renovating them; but more people are moving there every year, and before long it could be a larger constellation of rural occupations than Itoiz. Many in these villages maintain strong connections to the squatters’ movement in Barcelona, and there is an open invitation for people to visit, help out, or even move there.

Under certain circumstances, a community can also gain the autonomy it needs to build a new form of living by buying land, rather than occupying it; however though it may be more secure this method creates added pressures to produce and make money in order to survive, but these pressures are not fatal. Longo Maï is a network of cooperatives and autonomous villages that started in Basel, Switzerland, in 1972. The name is Provençal for “long may it last,” and so far they have lived up to their eponym. The first Longo Maï cooperative are the farms Le Pigeonnier, Grange neuve, and St. Hippolyte, located near the village Limans in Provence. Here 80 adults and many children live on 300 hectares of land, where they practice agriculture, gardening, and shepherding. They keep 400 sheep, poultry, rabbits, bees, and draft horses; they run a garage, a metal workshop, a carpentry workshop, and a textile studio. The alternative station Radio Zinzine has been broadcasting from the cooperative for 25 years, as of 2007. Hundreds of youth pass through and help out at the cooperative, learning new skills and often gaining their first contact with communal living or non-industrial agriculture and crafting.

Since 1976 Longo Maï has been running a cooperative spinning-mill at Chantemerle, in the French Alps. Using natural dyes and the wool from 10,000 sheep, mostly local, they make sweaters, shirts, sheets, and cloth for direct sale. The cooperative established the union ATELIER, a network of stock-breeders and wool-workers. The mill produces its own electricity with smallscale hydropower.

Also in France, near Arles, the cooperative Mas de Granier sits on 20 hectares of land. They grow fields of hay and olive trees, on good years producing enough olive oil to provide for other Longo Maï cooperatives as well as themselves. Three hectares are devoted to organic vegetables, delivered weekly to subscribers in the broader community. Some of the vegetables are canned as preserves in the cooperative’s own factory. They also grow grain for bread, pasta, and animal feed.

In the Transkarpaty region of Ukraine, Zeleniy Hai, a small Longo Maï group, started up after the fall of the Soviet Union. Here they have created a language school, a carpentry workshop, a cattle ranch, and a dairy factory. They also have a traditional music group. The Longo Maï network used their resources to help form a cooperative in Costa Rica in 1978 that provided land to 400 landless peasants fleeing the civil war in Nicaragua, allowing them to create a new community and provide for themselves. There are also Longo Maï cooperatives in Germany, Austria, and Switzerland, producing wine, building buildings with local, ecological materials, running schools, and more. In the city of Basel they maintain an office building that serves as a coordinating point, an information hub, and a visitors’ center.

The call-out for the cooperative network, drafted in Basel in 1972, reads in part:

What do you expect from us? That we, in order not to be excluded, submit to the injustice and the insane compulsions of this world, without hope or expectations?

We refuse to continue this unwinnable battle. We refuse to play a game that has already been lost, a game whose only outcome is our criminalization. This industrial society goes doubtlessly to its own downfall and we don’t want to participate.

We prefer to seek a way to build our own lives, to create our own spaces, something for which there is no place within this cynical, capitalist world. We can find enough space in the economically and socially depressed areas, where the youth depart in growing numbers, and only those stay behind who have no other choice. [112]

As capitalist agriculture becomes increasingly incapable of feeding the world in the wake of catastrophes related to climate and pollution, it seems almost inevitable that a large number of people must move back to the land to create sustainable and localized forms of agriculture. At the same time, city dwellers need to cultivate consciousness of where their food and water come from, and one way they can do this is by visiting and helping out in the villages.

#organization#revolution#anarchism#daily posts#communism#anti capitalist#anti capitalism#late stage capitalism#anarchy#anarchists#libraries#leftism#social issues#economy#economics#climate change#anarchy works#environmentalism#environment#solarpunk#anti colonialism#acab

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Me dan ganas de pegarle un corchazo a mi abuelo, no puede ser tan cabeza cerrada y decir que hay que matarlos a todos (los piqueteros) y mi mamá le dice que hay estudiantes de la UBA ahí, y él responde: "Todos comunistas."

#argieposting#🇦🇷#argentina#es literalmente el meme del viejo que parece copado y que dice cosas que te hacen quedar como: 😀?#en fin...#mi post

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

"hoy estaba hablando con mis compañeros de laburo de q korra 100% le voto a bullrich" i hate thisss

Bueno pero es verdad o no es verdad 🤨 si es canon que le encanta reprimir piqueteros

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Everything that is subordinated to capital is brutally exploited. Capitalism, more than ever, produces life for death. Its own mode of accumulation structurally generates exclusion. The moment of greatest productivity in the history of humankind is also that of the most misery.

On the other hand, the strength of struggles increasingly lies in their tendencies to become autonomous from capital’s command. Whole networks of Indigenous culture, of peasants, and direct producers develop an increasingly powerful counter-power at the grassroots level of society.

Colectivo Situaciones

#anarchism#capitalism#colectivo situaciones#south america#quote#communism#socialism#police#state#ill will

24 notes

·

View notes

Link

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Being a Clannibal shipper AND an Argentinian makes you realize that "running away to Argentina" isn't really the happy ending no-Argentinians fans think it is. I feel very bad for Clannibal. I'm 100% sure Hannibal went insane the first year of living here. Clarice probably became a serial killer of Piqueteros.

73 notes

·

View notes

Note

Los canas son unos miserables. Yo vivo en Córdoba y esta no es una respuesta normal de la policía a una protesta con corte total de calzada. Yo caminaba con 13 años entre manifestaciónes con cortes y bombas de estruendo y mi vida nunca corrió riesgo. Los piqueteros nunca me tocaron un pelo. Gracias a Llaryora, ahora la protesta pone en riesgo la vida de los trabajadores. Me cago en Bullrich y su "orden", quiere gente lesionada y muerta.

La protesta era totalmente pacífica, y eran apenas 30 policías que hicieron una represión tremenda. Los videos están en twitter y C5N. Tengo como la sospecha que en algún momento los canas dijeron "hora de aplicar El Protocolo" y se mandaron.

Lo único que están haciendo es calentando a la gente.

31 notes

·

View notes

Note

los europeos llorarán todo lo que quieran, pero les pasamos cumbia villera en su casa y en su cancha y le dejamos los métodos piqueteros a qatar encima, nos pueden sancionar todo lo que quieran pero ya ganamos por partida triple

encima esos que quieren repetir el partido 🤌🏻🤌🏻🤌🏻 tanto les gusta perder? dejame 'e jodé

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapter 6. Revolution

How will communities decide to organize themselves at first?

All people are capable of self-organization, whether or not they are experienced in political work. Of course, taking control of our lives won’t be easy at first, but it is imminently possible. In most cases, people take the obvious approach, spontaneously holding large, open meetings with their neighbors, co-workers, or comrades on the barricades to figure out what needs to be done. In some cases, society is organized through pre-existing revolutionary organizations.

The 2001 popular rebellion in Argentina saw people take an unprecedented level of control over their lives. They formed neighborhood assemblies, took over factories and abandoned land, created barter networks, blockaded highways to compel the government to grant relief to the unemployed, held the streets against lethal police repression, and forced four presidents and multiple vice presidents and economic ministers to resign in quick succession. Through it all, they did not appoint leadership, and most of the neighborhood assemblies rejected political parties and trade unions trying to co-opt these spontaneous institutions. Within the assemblies, factory occupations, and other organizations, they practiced consensus and encouraged horizontal organizing. In the words of one activist involved in establishing alternative social structures in his neighborhood, where unemployment reached 80%: “We are building power, not taking it.”[101]

People formed over 200 neighborhood assemblies in Buenos Aires alone, involving thousands of people; according to one poll, one in three residents of the capital had attended an assembly. People began by meeting in their neighborhoods, often over a common meal, or olla popular. Next they would occupy a space to serve as a social center — in many cases, an abandoned bank. Soon the neighborhood assembly would be holding weekly meetings “on community issues but also on topics such as the external debt, war, and free trade” as well as “how they could work together and how they saw the future.” Many social centers would eventually offer:

an info space and perhaps computers, books, and various workshops on yoga, self defence, languages, and basic skills. Many also have community gardens, run after school kids’ clubs and adult education classes, put on social and cultural events, cook food collectively, and mobilise politically for themselves and in support of the piqueteros and reclaimed factories.[102]

The assemblies set up working groups, such as healthcare and alternative media committees, that held additional meetings involving the people most interested in those projects. According to visiting independent journalists:

Some assemblies have as many as 200 people participating, others are much smaller. One of the assemblies we attended had about 40 people present, ranging from two mothers sitting on the sidewalk while breast feeding, to a lawyer in a suit, to a skinny hippie in batik flares, to an elderly taxi driver, to a dreadlocked bike messenger, to a nursing student. It was a whole slice of Argentinean society standing in a circle on a street corner under the orange glow of sodium lights, passing around a brand new megaphone and discussing how to take back control of their lives. Every now and then a car would pass by and beep its horn in support, and this was all happening between 8 pm and midnight on a Wednesday evening![103]

Soon the neighborhood assemblies were coordinating at a city-wide level. Once a week the assemblies sent spokespeople to the interbarrio plenary, which brought together thousands of people from across the city to propose joint projects and protest plans. At the interbarrio, decisions were made with a majority vote, but the structure was non-coercive so the decisions were not binding — they were only carried out if people had the enthusiasm to carry them out. Accordingly, if a large number of people at the interbarrio voted to abstain on a specific proposal, the proposal was reworked so it would receive more support.

The asamblea structure quickly expanded to the provincial and national levels. Within two months of the beginning of the uprising, the national “Assembly of Assemblies” was calling for the government to be replaced by the assemblies. That did not occur, but in the end the government of Argentina was forced to make popular concessions — it announced it would default on its international debt, an unprecedented occurrence. The International Monetary Fund was so scared by the popular rebellion and its worldwide support in the anti-globalization movement, and so embarrassed by the collapse of its poster child, that it had to accept this stunning loss. The movement in Argentina played a pivotal role in accomplishing one of the major goals of the anti-globalization movement, which was the defeat of the IMF and World Bank. As of this writing, these institutions are discredited and facing bankruptcy. Meanwhile, the Argentine economy has stabilized and much of the popular outrage has subsided. Still, some of the assemblies that made a vital niche in the uprising continue to operate seven years later. The next time the conflict comes to the surface, these assemblies will remain in the collective memory as the seeds of a future society.

The city of Gwangju (or Kwangju), in South Korea, liberated itself for six days in May, 1980, after student and worker protests against the military dictatorship escalated in response to declarations of martial law. Protestors burned down the government television station and seized weapons, quickly organizing a “Citizen Army” that forced out the police and military. As in other urban rebellions, including those in Paris in 1848 and 1968, in Budapest in 1919, and in Beijing in 1989, students and workers in Gwangju quickly formed open assemblies to organize life in the city and communicate with the outside world. Participants in the uprising tell of a complex organizational system developed spontaneously in a short period of time — and without the leaders of the main student groups and protest organizations, who had already been arrested. Their system included a Citizen’s Army, a Situation Center, a Citizen-Student Committee, a Planning Board, and departments for local defense, investigation, information, public services, burial of the dead, and other services.[104] It took a full-scale invasion by special units of the Korean military with US support to crush the rebellion and prevent it from spreading. Several hundred people were killed in the process. Even its enemies described the armed resistance as “fierce and well-organized.” The combination of spontaneous organization, open assemblies, and committees with a specific organizational focus left a deep impression, showing how quickly a society can change itself once it breaks with the habit of obedience to the government.

In the Hungarian Revolution of 1956, state power collapsed after masses of student protestors armed themselves; much of the country fell into the hands of the people, who had to reorganize the economy and quickly form militias to repel Soviet invasion. Initially, each city organized itself spontaneously, but the forms of organization that arose were very similar, perhaps because they developed in the same cultural and political context. Hungarian anarchists were influential in the new Revolutionary Councils, which federated to coordinate defense, and they took part in the workers’ councils that took over the factories and mines. In Budapest old politicians formed a new government and tried to harness these autonomous councils into a multiparty democracy, but the influence of the government did not extend beyond the capital city in the days before the second Soviet invasion succeeded in crushing the uprising. Hungary did not have a large anarchist movement at the time, but the popularity of the various councils shows how contagious anarchistic ideas are once people decide to organize themselves. And their ability to keep the country running and defeat the first invasion of the Red Army shows the effectiveness of these organizational forms. There was no need for a complex institutional blueprint to be in place before people left their authoritarian government behind. All they needed was the determination to come together in open meetings to decide their futures, and the trust in themselves that they could make it work, even if at first it was unclear how.

#organization#revolution#anarchism#daily posts#communism#anti capitalist#anti capitalism#late stage capitalism#anarchy#anarchists#libraries#leftism#social issues#economy#economics#climate change#anarchy works#environmentalism#environment#solarpunk#anti colonialism#acab

6 notes

·

View notes

Note

ey en serio le van a sacar planes a los piqueteros? tenemos chances como pais 😁😁😁

el que va a cobrar planes soy yo cuando me garche a tu viejo y le de un hijo del que pueda estar orgulloso

#porque no te sacas el anon?#o acaso tenes miedo de que sepan que sos libertario? y si. deberias#argentina

4 notes

·

View notes