#pico iyer

Quote

And if travel is like love, it is, in the end, mostly because it’s a heightened state of awareness, in which we are mindful, receptive, in dimmed by familiarity and ready to be transformed. That is why the best trips, like the best love affairs, never really end.

Pico Iyer

159 notes

·

View notes

Text

What more could one ask of a companion? To be forever new and yet forever steady. To be strange and familiar all at once, with enough change to quicken my mind, enough steadiness to give sanctuary to my heart. The books on my shelf never asked to come together, and they would not trust or want to listen to one another; but each is a piece of a stained-glass whole without which I couldn’t make sense to myself, or to the world outside.

—Pico Iyer

9 notes

·

View notes

Link

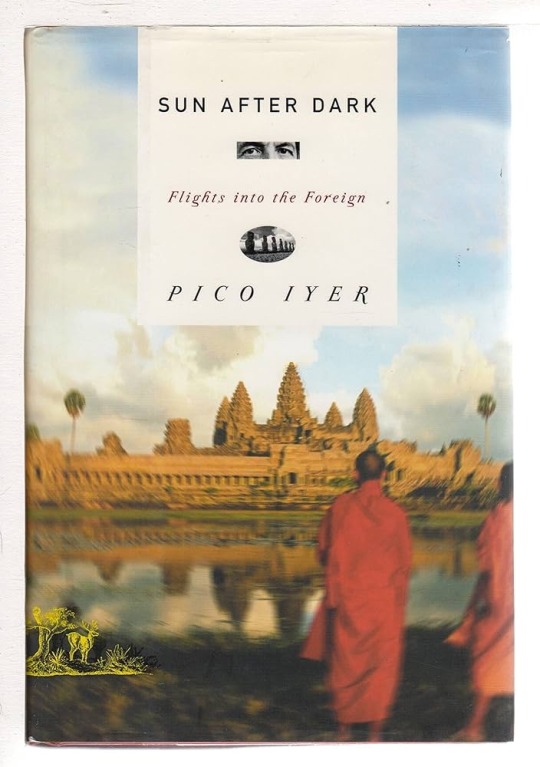

By Pico Iyer

[Mr. Iyer is the author, most recently, of “The Half Known Life: In Search of Paradise.”]

One day in my 20s, several decades ago, I got on a plane in New York City and flew across the world. It was dark when I arrived in Bali, but when I awoke the next day, a young man with a beautiful smile brought me fresh mango and strong tea to enjoy on the terrace of my bungalow. All around, playing amid bright flowers, were little girls with the faces of angels. Within hours, midwinter gloom had been transformed, as if by magic, into tropical sunshine. I was paying two dollars a night for a cottage of my own with a golden beach 45 seconds away, down a fragrant, palm-shaded lane.

I was in Eden, I decided. When night fell, however, I began to hear the clangorous and dissonant sound of gamelan orchestras, eerie, on every side of me. I saw boys with beautiful smiles stabbing themselves with daggers in a ritual dance that re-enacts a legendary battle between black magic and white. The little girls with angel faces were performing their dances while in a trance. Eden, I began to recall, is the place where it’s death to know too much.

All along the dusty streets were masks on sale, in front of dusty shacks. Smiling gods, grinning demons, mythical birds that glared at me so intently I had to hurry past. Finally I came upon a mask of an owl, red and yellow and green, that looked like the perfect thing to take home, an innocuous memento of the enchanted island. As soon as I got back to my apartment on East 20th Street, I put the mask on the wall — and within seconds I had to tear it down and put it away where I’d never see it again. There was a power to the object that reminded me that I couldn’t begin to understand the charged forces all around me on the island. Even what looked to be a child’s plaything was effectively a “No Trespassing” sign.

As a constant traveler for 49 years now, I sometimes feel I’ve been zigzagging from one “paradise” to the next. From Tahiti to Tibet, from the Seychelles to Antarctica, I’ve found tourist posters conspiring with travelers’ hopes to present every place as a kind of Eden. Yet often it’s our very notions of paradise that intensify divisions. In Sri Lanka I’d realized that the island has so often been taken to be Arcadia — Arabs saw it as “contiguous with the Garden of Eden,” and an Italian papal legate announced that the waters of paradise could be there — that the Portuguese, the Dutch, the British and millions of us tourists have all scrambled to grab a piece of it.

In Jerusalem, like every other visitor, I’d been vividly reminded that the city of faith has always been a city of conflict. Not just between the three great monotheisms whose sacred spaces stand only a few hundred yards from one another, but within each one of the faiths. I’m not Muslim or Christian or Jewish, but I’ve seldom encountered a more moving and magnetic site. Day after day I find myself drawn, regardless of my plans, back to the Church of the Holy Sepulcher. Yet within that soul-shaking building, where Christ is said to have been buried, the six Christian orders that share space go after one another with brooms if one of them so much as steps across another’s territory.

In Kashmir, I’d sat on a houseboat in the sun — nothing to be heard but the sound of kingfishers’ wings above a lotus pond — as locals in little boats paddled past, offering aromatic spices and exquisitely carved small boxes. I was truly in Heaven — so long as I forgot that, minutes across the water, army roadblocks and encampments spoke for the more than half a million soldiers trying to maintain peace in a bitterly contested territory claimed for more than 70 years now by both India and Pakistan. In Ladakh, the kind of pristine Himalayan region that might have inspired the notion of Shangri-La, I discovered more peace and beauty than I dared to dream of — along with local kids who reminded me that the real paradise was that place called California.

Besides, if I really did come upon a calm and self-contained Eden, what would it have to gain from me? I, like any visitor, could only be the serpent in the garden.

One day I found myself standing amid the floating bodies and unceasing roar of the River Ganges in Varanasi, the holy city of Hinduism. Flames to both the north and the south were reducing dead bodies to ash around the clock. The narrow lanes behind me were almost impassable with families rushing corpses along on stretchers to be committed to the water or the fires. Naked ascetics, smeared in ash, were expressing their contempt for simple notions of right and wrong by living in graveyards and drinking from skulls. The holy waters the faithful were gratefully imbibing contained hundreds of times the maximum level of coliform bacteria the World Health Organization has deemed safe for drinking.

As I surveyed the chaos, I heard someone call my name. It was an American monk I know who would soon be appointed by the Dalai Lama to be the abbot of a Tibetan Buddhist monastery in southern India. When I turned around to greet him, I noticed he could scarcely contain his delight.

“Isn’t it glorious?” I recall him saying. Here was the whole human pageant, vital and human and irreducible. I, though entirely of Hindu blood, was perplexed, unsettled by the confusion; he, from a very different tradition — I’d last bumped into him hurrying along Fifth Avenue — could see that this was none other than the only life we had. All our paradise, our only hopes, had to be uncovered here, in the midst of real life — and in the face of death.

Glorious? Well, it may take me a while to advance to that level of clearsightedness. But if paradise is anywhere, I was coming to see, it couldn’t be anywhere but where I stood.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Books Read in June:

1). Postcards from Surfers (Helen Garner)

2). Dedications (Iran Sanadzadeh)

3). The Lagoon and Other Stories (Janet Frame)

4). Every Day Is for the Thief (Teju Cole)

5). The Questions That Matter Most: Reading, Writing, and the Exercise of Freedom (Jane Smiley)

6). The Dutch House (Ann Patchett)

7). Perfume: The Story of a Murderer (Patrick Süskind)

8). How Fiction Works (James Wood)

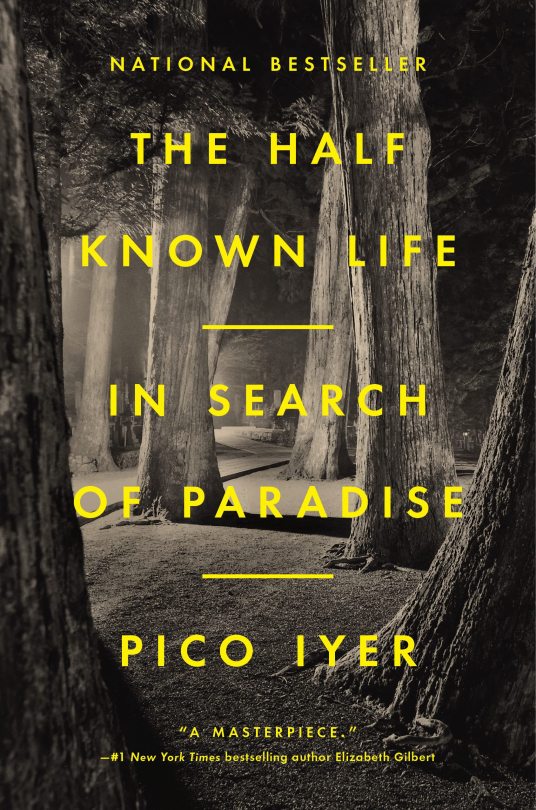

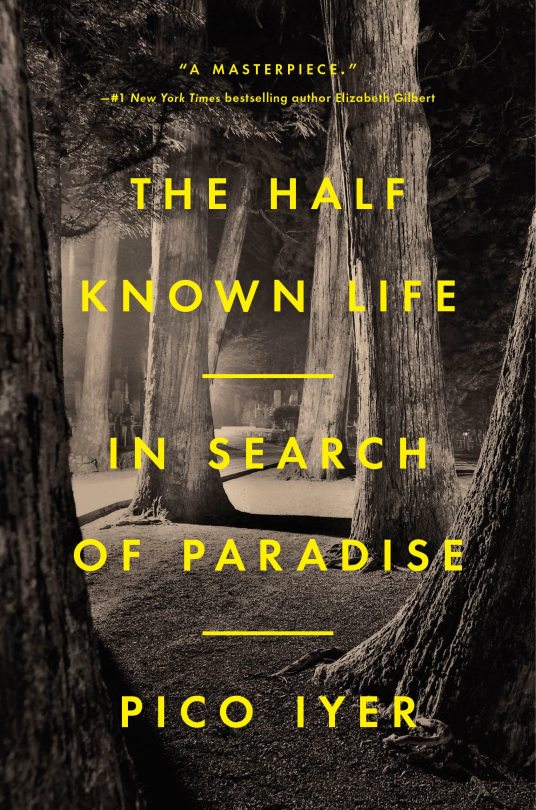

9). The Half Known Life: In Search of Paradise (Pico Iyer)

10). Best of Friends (Kamila Shamsie)

11). Adventures in Pen Land: One Writer’s Journey from Inklings to Ink (Marianne Gingher)

12). Dress Your Family in Corduroy and Denim (David Sedaris)

#my literary life#booklr#book list#adult booklr#helen garner#iran sanadzadeh#janet frame#teju cole#jane smiley#ann patchett#patrick süskind#james wood#pico iyer#kamila shamsie#marianne gingher#david sedaris#(had a sort of prickly conversation about how many books is too many books#when does devouring literature become something close to considering art consumable?#anyway. that’s what this month’s substack is about)#((if unclear: i was the prickly one because defensive))

5 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Sometimes, when I don't intend to, or am just walking down the road, or reading a biography of the incorrigibly licentious Lord Rochester, I think about what I seek at mealtime. It's not the tastes I savour; it's the setting, the circumstances, the company. I would rather, as Thoreau might have muttered, eat a hunk of bread with a friend over good conversation, in a place of beauty such as this, than suffer through a multicourse opera at El Bulli. The food is a means to happiness, a sense of peace; and the true meaning of happiness, as Socrates told me yesterday morning, is not to have more things but to need less.

Pico Iyer, “Daily Bread”; from “A Moveable Feast: Life-Changing Food Adventures Around the World” edited by Don George

#pico iyer#don george#a moveable feast: life-changing food adventures around the world#quotes#what i’m reading#this this this this

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Not many years ago, it was access to information and movement that seemed our greatest luxury; nowadays it’s often freedom from information, the chance to sit still, that feels like the ultimate prize. Stillness is not just an indulgence for those with enough resources—it’s a necessity for anyone who wishes to gather less visible resources. Going nowhere, as Cohen had shown me, is not about austerity so much as about coming closer to one’s senses. Going nowhere … isn’t about turning your back on the world; it’s about stepping away now and then so that you can see the world more clearly and love it more deeply.”

―Leonard Cohen and the Art of Stillness: Pico Iyer on What the Monastic Musician Taught Him About Presence

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

LIMINAL LIVING - Prelude

I started a weekly feature following in the steps of Sharon Astyk’s now-completed “Independence Days” project (June-Aug 2022), which offered a flexible weekly framework for recognising and sharing actions related to building resiliency, community, and accountability (in and out of the garden), things that can make our lives better now and in the future. Over time, I modified some of her…

View On WordPress

#alive#being alive#dying#heterotopias#identity#Independence Days#life and death#liminal life#liminality#living#living and dying#love#Luca Davis#mortality#pico iyer#Sarah McLaen#seeking light#the hours#the ritual of existence#thresholds#waiting#way-stations

0 notes

Text

Stoga je u doba ubrzavanja najuzbudljivije ići sporo. U doba odvlačenja pažnje najveći je luksuz obraćati pažnju. A u doba stalnoga kretanja od najveće je važnosti sjediti mirno.

― Pico Iyer

0 notes

Text

In an age of speed, I began to think, nothing could be more invigorating than going slow. In an age of distraction, nothing can feel more luxurious than paying attention.

– Pico Iyer

1 note

·

View note

Text

Finished reading The Half-Known Life by Pico Iyer the other day and wrote something inspired from it!

1 note

·

View note

Text

Jose Basso, 1949 -

Chilean artist. :: The Other Side Of Art

* * * *

In the altogether magnificent The Open Road: The Global Journey of the Fourteenth Dalai Lama (public library), writer Pico Iyer — who has known the beloved spiritual leader since adolescence and, by the time he began writing this book, had visited him in his exile home for nearly thirty years — describes how the Dalai Lama begins each day:

[By] nine a.m. … the Dalai Lama himself had already been up for more than five hours, awakening, as he always does, at three-thirty a.m., to spend his first four hours of the day meditating on the roots of compassion and what he can do for his people, the “Chinese brothers and sisters” who are holding his people hostage, and the rest of us, while also preparing himself for his death.

Compressed into this humble and humbling morning routine is the entire Buddhist belief that life is a “joyful participation in a world of sorrows.”

[from Brain Pickings]

Life is joyful participation in a world of sorrows. I think that sums things up rather beautifully.

#quotes#The Open Road#Pico Iyer#Dalai Lama#Joyful Participation#world of sorrows#Jose Basso#Chilean artist#The Other Side Of Art

17 notes

·

View notes

Photo

In Search of the Sacred: Pico Iyer on Our Models of Paradise

"The thought that we must die... is the reason we must live well."

https://www.themarginalian.org/2023/02/04/pico-iyer-the-half-known-life/

0 notes

Text

Pico Iyer's 'The Half Known Life' upends the conventional travel genre

January 10, 2023

“In Jerusalem, humans were so sure of their gods that each drew, in rough bold strokes, its own image of paradise on top of somebody else’s. It was dangerously easy to believe that what we do with heaven is even more important than what heaven does to us.”

'Seeing the expulsion of Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden as a necessary fall, and the Buddha's departure from his princely estate as a conscious acceptance of human frailties, Iyer concludes that a true paradise is only attainable through displacement."

READ MORE https://www.npr.org/2023/01/10/1148033914/pico-iyer-the-half-known-life-book-review-travel

"In 1974, when Pico Iyer was a teenager, he traveled to India, where his father was meeting with the Dalai Lama. There the boy and the most exalted monk in Buddhism began a friendship that has deepened over nearly half a century.

This friendship is not narrowly built around Buddhism. Iyer’s father was an Indian philosopher and political theorist who moved his family to California, where he joined a think tank and started teaching at the University of California, Santa Barbara. His mother is a religious scholar. Their son’s education was just as international: Eton, followed by Oxford, then a master’s degree in literature at Harvard. And then, for decades, journalism: 100 articles a year for Time, with more for other top-drawer publications. Books? 15 so far. And four TED talks that have been viewed more than 10 million times. The frequent topic: travel.

The subtitle of his memoir, “In Search of Paradise,” evokes “White Lotus.” Iyer seeks the exact opposite. “The pursuit of happiness,” he writes, “made deepest sense in context of the Buddhist principle that suffering is the first truth of existence.” It follows that the desire for paradise isn’t a solution to our problems. It is the problem: “What kind of paradise can ever be found in a world of unceasing conflict — and does the search for it not simply aggravate our differences?” Clearly, this is not like any other travel book you’ve read.

And then there’s traveling with the Dalai Lama. Iyer was by his side for every hour of his working day on ten trips to Japan in twelve years. The Dalai Lama, he reports, “had no interest in wishful or romantic notions… true to the example of what he called his “big boss,” the Buddha, he always seemed to see himself as a doctor of the mind.” Asked in a public lecture what to do after you’ve been disappointed in a worthy dream, “the Dalai Lama looked at the questioner with great warmth and said, ‘Wrong dream!’”

It’s in the final chapters that Iyer delivers the book’s gold. Many of us see life through screens, reducing fellow humans to two dimensions. The half known life — the phrase comes from Herman Melville — is where so many of our possibilities lie: “everything half known, from love to faith to wonder and terror, that determines the course of our lives….Everything in life that we can’t begin to make sense of… that’s what opens the door to a sense of something beyond us, and a useful humility….We can never begin to guess what will happen next. The world is always more complex than our ideas of it.”

-<>-amazon.com 5 star review

0 notes

Text

“What if? points in both directions.”

― Pico Iyer, The Art of Stillness: Adventures in Going Nowhere

1 note

·

View note