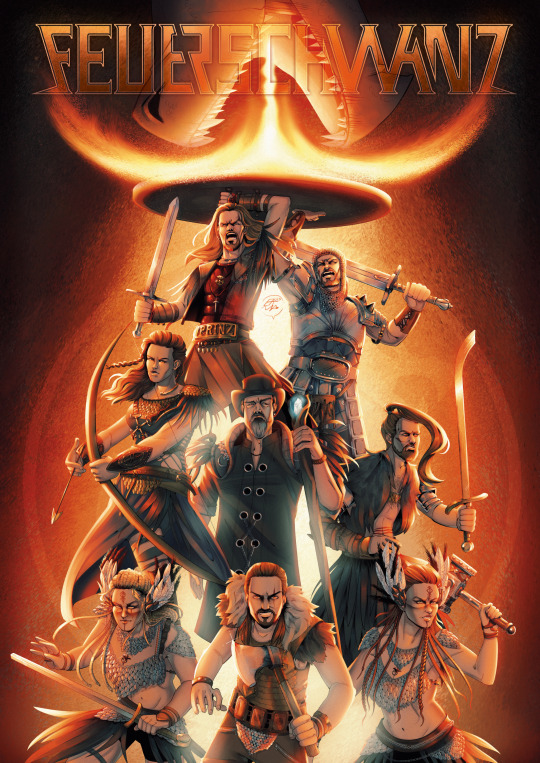

#peter henrici

Text

Fafnir, Hreitmars Sohn, Ich fürchte nicht den Tod und nicht dein Feuer!

[6 august 2023]

(Queueing old art everyday just for the sake of keeping this blog mildly updated).

#feuerschwanz#ben metzner#prinz hodi#peter henrici#hauptmann feuerschwanz#johanna von der vögelweide#hans platz#rolf hering#jarne hodinsson#jenny diehl#mieze musch-musch#mieze myu#folk metal#art#digital art#fan art#illustration#digital illustration#artists on tumblr#clip studio paint

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

One year old anniversary of Warriors of the World United by Feuerschwanz! (Manowar Cover)

youtube

On 6th of december, last year Feuerschwanz covered Manowar's Warriors of the World United from their album Memento Mori and I think this version is way better than the original track and that it has more energy and power.

In my opinion this is one of the best covers that I've ever heard, the day it came out I listened to it like 50 times... :D. The guest singers are great, and the mixing as well, because each singer is balanced and have their own part in the track. The video also turned out amazingly, the battling parts with Myu and Musch-Musch just added to the atmosphere of the song and it quickly became one of my favorites and possibly my number one favorite song. :)

Line-up :

• Prinz Richard Hodenherz III (Hodi) - Ben Metzner / vocals ( he is also the singer of the band DArtagnan)

• Hauptmann Feuerschwanz / Peter Henrici - vocals

• Johanna von der Vögelveide (Stephanie Pracht) - violin, hurdy-gurdy

• Hans der Aufrechte / Hans Platz - guitars

• Jarne Hodinsson - Bass

• Rollo H. Schönhaar - Drums

Guest singers:

• Melissa Bonny (Ad Infinitum, Rage of Light)

• Thomas Laszlo Winkler (ex-GloryHammer)

• Alea der Bescheidene (Saltatio Mortis)

#such a masterpiece#*chefs kiss*#feuerschwanz#warriors of the world united#manowar cover#folk metal#melissa bonny#thomas laszlo winkler#alea der bescheidene#saltatio mortis

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

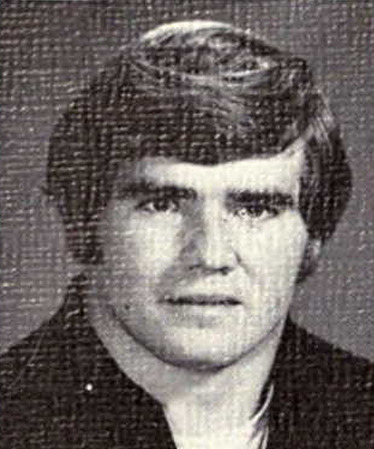

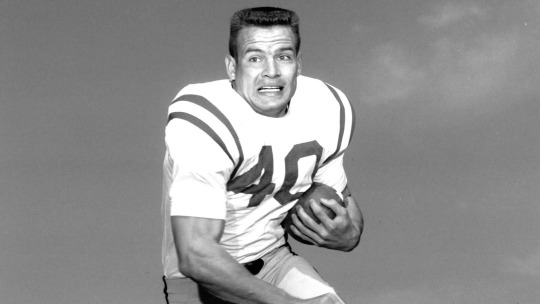

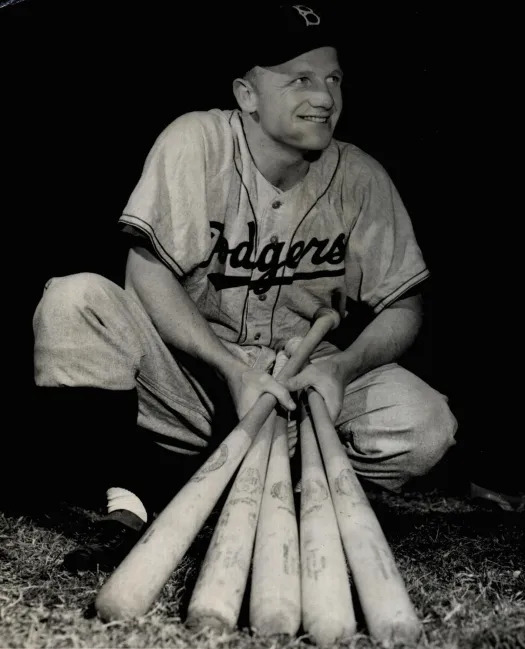

2023 In Memoriam Part 23

Mike Hoban, 71

Luigi Marcon, 88

Sergio Calderón, 77

Patricia Dainton Williams, 93

Margit Carstensen, 83

Cynthia Weil Mann, 82

Billy Adams, 84

Mike Batayeh, 52

Bobby Morgan, 96

Lamar Morris, 84

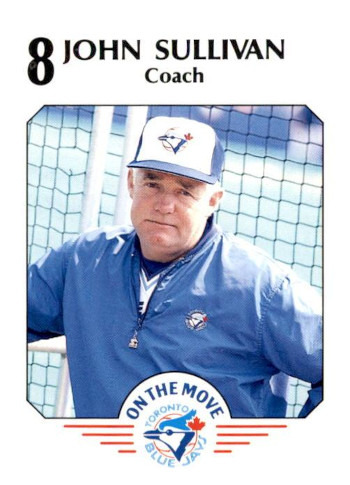

John Sullivan, 82

Willie Marshall, 92

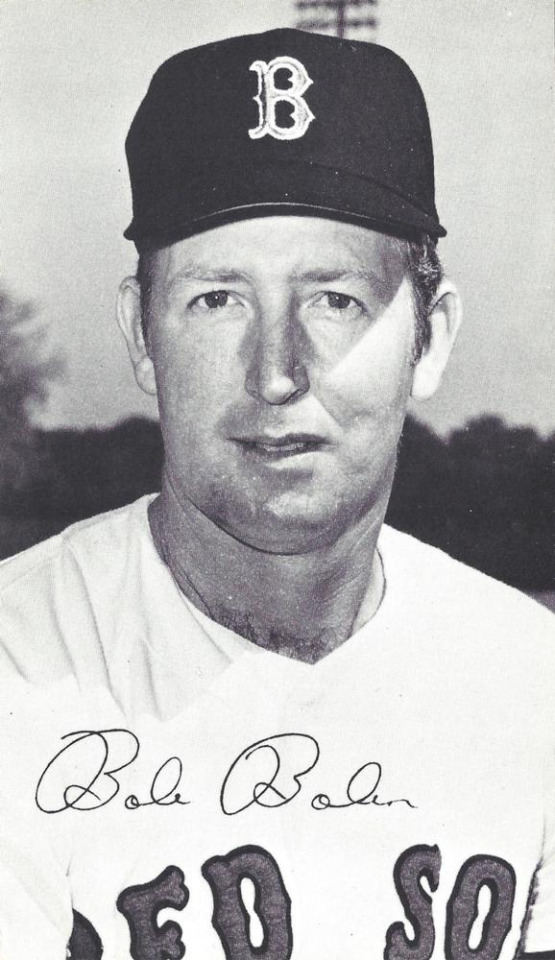

Bob Bolin, 84

Archbishop Michael Sheehan, 83

Jim Hines, 76

Bishop Macram Max Gassis, 84

Bishop Luigi Marrucci, 78

Roger Craig, 93

David Emery, 76

Norma Hunt, 85

Bishop Peter Henrici, 95

Jack Baldschun, 86

Françoise Gilot, 101

Jacques Murray, 103

Noreen Nash Whitmore, 99

(Cornelius) Neal Petties, 82

Richard E. Snyder, 90

Chye Lim, 103

Lisl Steiner, 95

Rev. Pat Robertson, 93

#Religion#Tributes#Celebrities#Sports#Football#Illinois#Hockey#Canada#Ontario#Movies#Mexico#U.K.#Germany#Music#New York City#New York#Alabama#Mississippi#TV Shows#Michigan#Baseball#Oklahoma#New Jersey#Pennsylvania#South Carolina#Kansas#New Mexico#Races#Arkansas#Sudan

0 notes

Photo

Hauptmann Feuerschwanz in all his glory his amazing light-up pauldrons.

From “Die Letzte Schlacht”, 29/01/2021

#feuerschwanz#Die Letzte Schlacht#hauptmann feuerschwanz#peter henrici#(at least that's what the metal encyclopedia gave me?)#metal

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Bromacker Fossil Project Part VII: Eudibamus cursoris, the Original Two-legged Runner

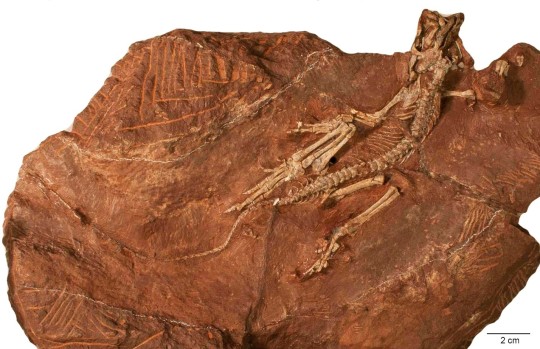

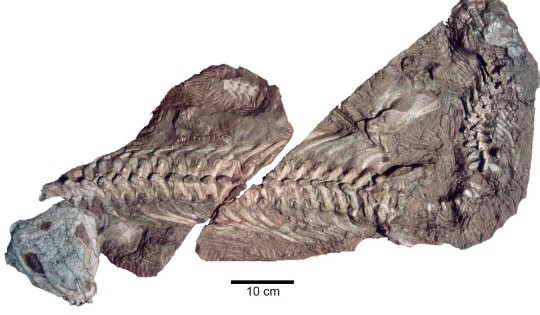

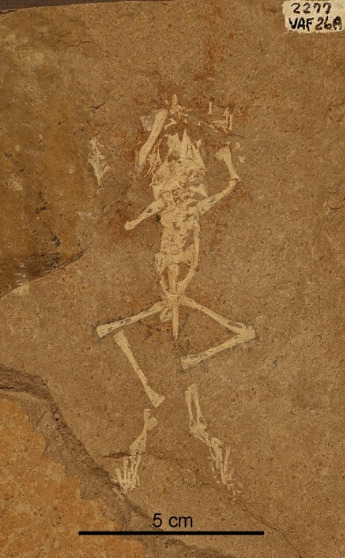

Holotype specimen of Eudibamus cursoris, the most complete bolosaurid reptile known. Photo by the author, 2013.

Stuart Sumida discovered some small bones in the Bromacker quarry in 1993, the same year that the holotype skeleton of Diadectes absitus was found. Dave Berman told me that when Stuart showed them to him, he couldn’t see anything because they were so small. Upon closer examination, Dave, Stuart, and Thomas Martens identified them as those of the captorhinomorph reptile Thuringothyris mahlendorffae. Thomas’ wife Stefani, whose maiden name is Mahlendorff, discovered the first specimen in the Bromacker in 1982, and Thomas and a colleague named it in her honor in a 1991 publication.

The fossil was exposed in several pieces of rock, which Thomas shipped to Carnegie Museum of Natural History (CMNH) along with the large block of rock containing Diadectes. I didn’t prepare the specimen until several years later, as other projects, including the Diadectes, overshadowed it. Once I began working on it, though, Dave and I realized that it was not Thuringothyris. Indeed, we had no idea what type of animal it was, and our puzzlement grew as I exposed more of it. The identity wasn’t revealed until I had uncovered some very unusual, tiny teeth, which under the high magnification of the preparation microscope appeared to have a bulbous cusp towering over a basin. They looked vaguely familiar to me, but because I couldn’t immediately put a name on them, I rushed to get Dave from his office. Once Dave saw the teeth, he realized that the specimen was a new genus and species in the rare, enigmatic reptile group Bolosauridae.

Tiny teeth of a bolosaurid reptile, Bolosaurus striatus, in lateral (side; left) and occlusal (chewing surface; right) views. The specimen is in the CMNH Vertebrate Paleontology collection. Photos by Spencer Lucas (Research Associate, CMNH).

Until the discovery of Eudibamus cursoris, bolosaurids were represented in the fossil record by two genera, Bolosaurus and Belebey, which were based mainly on poorly preserved skull and fragmentary jaw fossils from Texas and Russia, respectively. Even though bolosaurids had been known since 1878, their relationship to other reptiles was not well understood. The nearly complete anatomy of Eudibamus allowed our team to determine that bolosaurids are the oldest member of the ancient group of reptiles called Parareptilia. This group has no living relatives, except possibly for turtles, a hypothesis that is highly debated by scientists.

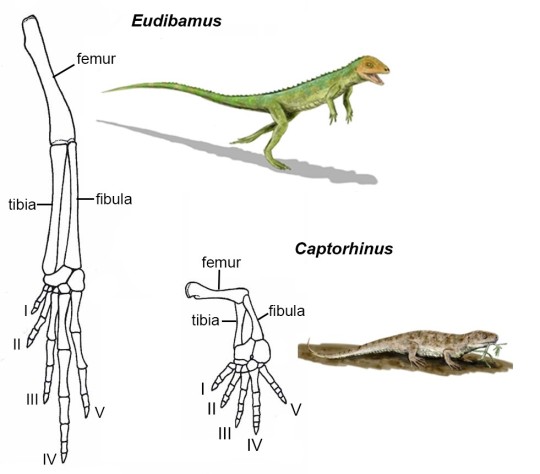

Closeup of front and hind legs of Eudibamus. The hind leg, folded upon itself, is considerably longer than the front leg. Photo by the author, 2013.

When our study of the fossil began, we realized that Eudibamus was very different than other reptiles from that time. Proportions of the limbs and positions of the articulation surfaces on the upper and lower hind leg bones indicated that, in terms of posture, Eudibamus resembled a bow-legged human with a bad back instead of a typical sprawling reptile on four legs. It could stand and locomote on its hind legs in an upright posture (bipedal) with its legs held close together and in the same plane (parasagittal).

Dave was in constant phone communication with team member Dr. Robert Reisz (Professor, University of Toronto at Mississauga). One day Robert called Dave to ask if all the tail had been exposed, because he learned that modern lizards that are able to run bipedally have a long tail to help maintain their balance. The specimen was in Dave’s office and he immediately uncovered more of the tail and then let me finish the task. The tail was indeed very long and extended close to the edge of the block, which I had previously reduced in size. Additionally, we determined that the third, fourth, and fifth toes of the hind foot also were greatly elongated through lengthening of some of the individual toe bones, and that the first and second toes were extremely shortened by the reduction in size of individual toe bones. We hypothesized that when Eudibamus ran bipedally, it would rise on its toes, so that only the tips of the third, fourth, and fifth toes would contact the ground.

Drawing of the hind leg of Eudibamus cursoris (left) and the roughly contemporaneous reptile Captorhinus (right). Leg drawings are scaled to the same torso length of the whole animal. Illustrations of the animals are not to scale. Hind leg drawings are modified from Berman et al., 2000 and animal illustrations are from Wikimedia Commons.

Eudibamus occurred at least 60 million years before other bipedal, parasagittally-running reptiles appeared in the fossil record. This is reflected in its scientific name, which is derived from the Greek “eu,” meaning original or primitive, and “dibamos,” meaning on two legs. “Cursoris” is Latin, meaning runner. Examples of other reptiles using this locomotion mode are the dinosaurs Allosaurus fragilis and Tyrannosaurus rex, which you can view in CMNH’s Dinosaurs in Their Time exhibition.

So, what was the advantage of being able to run bipedally instead of running on all four legs? Lengthening the hind leg and foot would greatly increase stride length, especially if only the tips of the toes contacted the ground, which is an efficient way to increase speed. Eliminating arm to ground contact while running removes forelimbs from the path of the long-striding hind legs. The bulbous teeth and jaw structure of Eudibamusindicate that it was herbivorous. It seems likely, then, that Eudibamus used its ability to sprint to avoid becoming a tasty meal for a pursuing predator.

Peter Mildner (exhibit preparator at the Museum der Natur, Gotha) made a surprise visit to the Bromacker one afternoon to show us a model of Eudibamus cursoris he’d made. This image shows the model in the present day Bromacker quarry, part of the region it inhabited 290 million years ago. Photo by the author, 2006.

One of our laments is that a fossil trackway preserving Eudibamus walking quadrupedally and then switching to a bipedal gait has yet to be found.

Next time you are at CMNH, make sure you see the cast of the fossil skeleton and a model of Eudibamus that are exhibited in the Fossil Frontiers display case in CMNH’s Dinosaurs in Their Time exhibition. Stay tuned for my next post, which will feature the herbivorous mammal-like reptile Martensius bromackerensis.

For those of you who would like to learn more about Eudibamus, here is a link to the 2000 Science publication in which it was described: https://science.sciencemag.org/content/290/5493/969.

Amy Henrici is Collection Manager in the Section of Vertebrate Paleontology at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

#Carnegie Museum of Natural History#Eudibamus cursoris#Reptiles#Fossils#Vertebrate Paleontology#Bromacker Fossil Project#Natural History

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

Daemonosaurus chauliodus

By José Carlos Cortés

Etymology: Demon Reptile

First Described By: Sues et al., 2011

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda

Status: Extinct

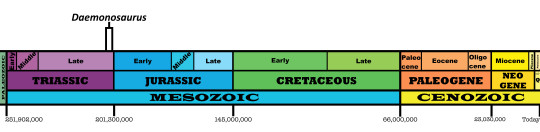

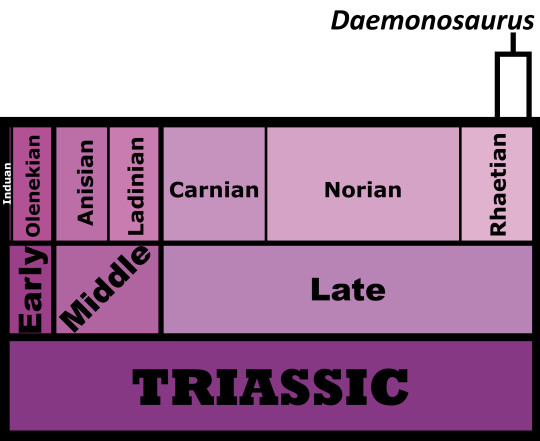

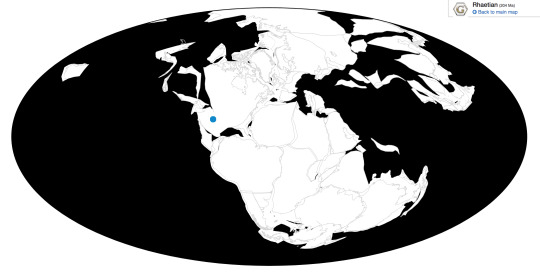

Time and Place: Between 205 and 202 million years ago, in the Rhaetian of the Late Triassic

Daemonosaurus is known from the Siltstone Member of the Chinle Formation in New Mexico

Physical Description: Daemonosaurus is an interestingly little dinosaur, and an enigmatic one, with its placement within the dinosaur family tree holding significant importance for how dinosaurs organize themselves in their initial diversification. This was a small, bipedal dinosaur, only about 1.5 meters long and weighing no more than 22 kilograms. While its body was relatively normal of a dinosaur at that time - longer legs than arms, arms built for grasping, long tail and stout torso - its head was downright bizarre. The skull was very short and box-like, rather than long and narrow or long and rectangular like other predatory dinosaurs of the time. Daemonosaurus also featured very long and large teeth in the upper jaw, and teeth that projected forward out of the mouth from both jaws - in short, it looked fairly buck-toothed. It also had a slight notch in its jaws, which could have been used to grab hold of struggling food and trap it there. It also might be an example of paedomorphy - while the head seems fairly juvenile (including rather big eyes), the rest of the body has the fused bones of an adult. As a small dinosaur, Daemonosaurus would have been covered in fluffy protofeathers for thermoregulation.

Diet: Daemonosaurus would have primarily eaten small animals like early mammals and smaller reptiles, though baby dinosaurs from other species wouldn’t have been off the menu.

By Michael B. H., CC BY-SA 3.0

Behavior: Daemonosaurus, being a smaller theropod, wouldn’t have been a very bold predator. Instead, it probably waited in the shadows and undergrowth a lot, looking for a moment to strike at its prey. Hiding in the bushes, it was able to stay safe from larger predators, which frequented the environment. It probably would use its hands and mouth to grab struggling prey, and also defend itself from danger. With its very large eyes, it’s even possible it was somewhat nocturnal, and did most of its hunting in the safety of night. It probably took care of its young, though of course without fossil evidence of such it is hard to tell; and it would have been a fairly active, intelligent animal in its habitat.

Ecosystem: Daemonosaurus lived in the Siltstone Environment of the Chinle Formation, a famous ecosystem showcasing the rise of dinosaurs within North America at the end of the Triassic Period. Daemonosaurus is known from one of the later ecosystems of that formation, which makes its position as a fairly basal theropod somewhat surprising. This was a seasonally arid floodplain, with trivers that would occasionally flood and alternate between that and drying up completely. As such, the plantlife around the floodplain was mostly hardy ferns, ginkgoes, horsetails, and cycads - as well as a fairly dense forest of pine and other coniferous trees. Here Daemonosaurus shared its environment with many other Triassic weirdos, such as the Drepanosaur (lizard-monkey thing) Avicranium, ray-finned fish such as Hemicalypterus and Lophionotus, the phytosaur Redondasaurus, the small Aetosaur Stenomyti; and other Dinosauromorphs. There was the Silesaurid Eucoelophysis, the Lagerpetid Dromomeron, and another theropod dinosaur, Ceolophysis.

By Scott Reid

Other: Is Daemonosaurus a theropod? Probably. But its head is so weird - and its whole body, too - that the position of Daemonosaurus is a question within the early diversification of dinosaur group. Indeed, Daemonosaurus often changes how a phylogenetic tree turns out. This weirdness is something to keep an eye on for now, because the jury is still out - though basal theropod seems likely. And what a weird theropod lineage it represents!

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources under the Cut

Barta, D. E., S. J. Nesbitt, M. A. Norell. 2018. The evolution of the manus of early theropod dinosaurs is characterized by high inter- and intraspecific variation. Journal of Anatomy 232: 80 - 104.

Ezcurra, M.D. (2006). "A review of the systematic position of the dinosauriform archosaur Eucoelophysis baldwini Sullivan & Lucas, 1999 from the Upper Triassic of New Mexico, USA." Geodiversitas, 28(4):649-684.

Griffin, C. T. 2019. Large neotheropods from the Upper Triassic of North America and the early evolution of large theropod body sizes. Journal of Paleontology: 1 - 21.

Irmis, R. B. 2005. The vertebrate fauna of the Upper Triassic Chinle Formation in northern Arizona. p. 63-88. in S.J. Nesbitt, W.G. Parker, and R.B. Irmis (eds.) 2005. Guidebook to the Triassic formations of the Colorado Plateau in northern Arizona: Geology, Paleontology, and History. Mesa Southwest Museum Bulletin 9.

Nesbitt, S.J., Irmis, R.B., and Parker, W.G. (2005). "A critical review of the Triassic North American dinosaur record." In Kellner, A.W.A., Henriques, D.D.R., & Rodrigues, T. (eds.), II Congresso Latino-Americano de Paleontologia de Vertebrados, Boletim de Resumos. Rio de Janeiro: Museum Nacional/UFRJ, 139.

Sues, H.-D., S. J. Nesbitt, D. S. Berman, A. C. Henrici. 2011. A late-surviving basal theropod dinosaur from the latest Triassic of North America. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 278 (1723): 3459 - 3464.

Sullivan, C., X. Xu. 2016. Morphological Diversity and Evolution of the Jugal in Dinosaurs. The Anatomical Record 300 (1): 30 - 48.

Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; and Osmólska, Halszka (eds.): The Dinosauria, 2nd, Berkeley: University of California Press. 861 pp. ISBN 0-520-24209-2.

#Daemonosaurus chauliodus#Daemonosaurus#Dinosaur#Theropod#Prehistoric Life#Paleontology#Palaeoblr#Factfile#Prehistory#Carnivore#Triassic#North America#Theropod Thursday#dinosaurs#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature

319 notes

·

View notes

Text

Henry Purcell (c. 10 September 1659 – 21 November 1695)

English composer. Although incorporating Italian and French stylistic elements into his compositions, Purcell's legacy was a uniquely English form of Baroque music. He is generally considered to be one of the greatest English composers. (Wikipedia)

From our stacks: Illustration “Vera Effigies Henrici Purcell. Aetat. Suae XXIV. C. Grignion sculp.” from A General History of the Science and Practice of Music, By Sir John Hawkins. A New Edition, with the Author’s Posthumous Notes. Vol. I. London: Novello, Ewer & Co.; New York: J. L. Peters, 1875.

#henry purcell#purcell#music#composer#music history#charles grignion#grignion#book#books#old books#book illustration#illustration#baroque#baroque music#composers#neglish music#english composer#detroit public library

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

February 27 in Music History

1709 Birth of baritone Francois Lepage in Joinville.

1729 FP of J. S. Bach's Sacred Cantata No. 159 Sehet, wie gehn hinauf gen Jerusalem on Esto mihi Sunday in Leipzig, was part of Bach's fourth annual Sacred Cantata cycle on texts by Christian Friedrich Henrici, aka Picander. Season, 1728-29.

1740 FP of Handel's oratorio L'Allegro, il Penseroso, ed il Moderato at Lincoln's Inn Field, in London.

1814 FP of Beethoven's Eighth Symphony in Vienna.

1839 Birth of tenor Victor Capoul in Toulouse.

1846 Birth of Spanish light opera composer Joaquin Valverde.

1848 Birth of English composer Charles Hubert Hastings Parry in Bournemouth.

1856 Birth of Italian baritone Mattia Battistini in Rome.

1867 Birth of Swedish composer Wilhelm Olof Peterson-Berger in Ullånger.

1870 Birth of German composer Louis Coerne.

1877 Birth of English pianist Adele Verne in Southampton.

1887 Death of Russian composer Alexander Borodin.

1897 Birth of American contralto Marian Anderson in Philadelphia, PA.

1888 Birth of German soprano Lotte Lehmann in Perleberg.

1890 Birth of Salvadoran composer María de Baratta in San Salvador.

1891 Birth of French composer Georges Migot in Paris

1892 Birth of mezzo-soprano Maartje Offers in Koudekerke, Holland.

1894 Birth of Russian conductor Issay Dobrowen.

1908 FP of Amy Beach's Piano Quintet. Hoffmann Quartet and Beach, piano at Boston's Potter Hall.

1909 Birth of mezzo-soprano Ruth Michaelis in Posen.

1913 FP of Walter Damrosch's opera Cyrano de Bergerac at the Metropolitan Opera in NYC.

1915 Death of tenor-baritone Rudolf Berger.

1915 FP of N.Myaskovskys Symphony No. 3, in Moscow.

1920 Birth of soprano Vilma Bukovec in Trebinje.

1926 Death of soprano Elena Theodorini.

1928 Birth of Austrian conductor and recorder player Rene Clemencic.

1928 Birth of bass Arne Tyren in Stockholm.

1935 Birth of Italian soprano Mirella Freni in Modina.

1935 Birth of tenor Alberto Remedios in Liverpool.

1936 Birth of tenor Ricardo Cassinelli in Buenos Aires.

1937 Birth of American composer Lynn Kurtz.

1938 Birth of soprano Margaret Curphey in Douglas, Isle of Man.

1940 Death of soprano Margaretha Abler.

1940 FP of William Schuman's String Quartet No. 3. Coolidge Quartet at Town Hall in NYC.

1944 Birth of baritone Erland Hagegard in Brunskog.

1945 FP of Amy Beach's opera Cabildo.

1947 FP of Paul Hindemith's Piano Concerto. Cleveland Orchestra, George Szell conducting, with pianist Jesús Maria Sanromá.

1947 Birth of violinist Gidon Kremer in Riga Latvia.

1947 FP of Peter Mennin's Symphony No. 3. New York Philharmonic, Walter Hendel conducting.

1949 FP of Elliott Carter's Cello Sonata & Woodwind Quintet in NYC.

1949 FP of William Schuman's Symphony No. 6. Dallas Symphony, Antal Dorati conducting.

1960 Birth of Swedish composer Reine Jönsson in Näsum.

1965 Birth of German violinist Frank Peter Zimmermann.

1969 Death of soprano Alida Vane.

1971 Death of mezzo-soprano Elsa Margarethe Gardelli.

1981 Death of soprano Germana Di Giulio.

1984 FP of Libby Larsen's Parachute Dancing.

1985 Death of baritone Benvenuto Franci.

1999 FP of Peter Lieberson's Horn Concerto, soloist William Purvis with the Orpheus Chamber Orchestra at Carnegie Hall.

2003 Death of English composer and ballet conductor John Lanchbery.

2004 FP of Michael Gordon´s Gotham. Multimedia presentation with the American Composers Orchestra, Sloan, conducting, at the Ridge Theater, Zankel Hall, NYC.

2013 Death of pianist Van Cliburn.

0 notes

Text

Vishay Intertechnology, Inc. (VSH) CEO Gerald Paul on Q1 2019 Results

Vishay Intertechnology, Inc. (VSH) CEO Gerald Paul on Q1 2019 Results

Seeking Alpha – Vishay Intertechnology, Inc. (NYSE:VSH) Q1 2019 Earnings Conference Call May 9, 2019 09:00 ET Company Participants Peter Henrici – SVP, Corporate Communications

Source: New feed

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

memento mori, bis der tod die messer wetzt!

[11 january 2023]

(Queueing old art everyday just for the sake of keeping this blog mildly updated).

#feuerschwanz#ben metzner#prinz hodi#peter henrici#hauptmann feuerschwanz#johanna von der vögelweide#hans platz#rolf hering#jarne hodinsson#jenny diehl#mieze musch-musch#mieze myu#so many tags for so many people but i love my silly germans#folk metal#art#digital art#illustration#digital illustration#digital portrait#clip studio paint

15 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Brenn' kleine Kerze. Du bist so schön.

Peter Henrici

#Peter Henrici#kerzenschein#kerze#dark#finsternis#hoffnung#schön#licht#lichtlein#brennen#klein#kerzen#blutxmeer

0 notes

Photo

From “Die Letzte Schlacht”, 29/01/2021

Feuerschwanz feat. Angus McFife of Gloryhammer

______________________

Oh gods, that’s all of them. Whew.

#Die Letzte Schlacht#feuerschwanz#gloryhammer#Prinz R. Hodenherz III#hauptmann feuerschwanz#angus mcfife#Ben Metzner#Peter Henrici (musician)#thomas winkler#I have decided to just sign all of them from now on since most gifs require resizing anyway#I wish the thing also let me put them somewhere in the corner though

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Bromacker Project Part IV: Diadectes absitus, A Project-Saving Fossil

This post will be the first of a series focusing on notable fossil animals discovered in the Bromacker quarry. I selected Diadectes abisitus, a member of the ancient group Diadectomorpha, to present first because, had it not been discovered in the first year of the collaborative field work, the project might not have continued.

Dave Berman and his colleague Stuart Sumida (California State University, San Bernardino) joined Thomas Martens for five weeks of field work in the summer of 1993. They dug a quarry over six feet deep in their search for fossils, while working in a mix of hot and humid or near freezing temperatures, with plenty of rain. It wasn’t until the second-to-last day of the field season that the Diadectes specimen was discovered. By then, as Dave later told me, he was so discouraged by the lack of fossils that he assumed this would be his first and last field season in Germany. I should mention that Stuart had previously uncovered a few small vertebrae, but because the vertebrae resembled an animal described from the Bromacker in 1991, the team was not very excited about the discovery. They couldn’t have been more wrong in their field identification of the vertebrae, however, but more on that in a later post.

The 1993 quarry shortly before discovery of Diadectes absitus. Pictured are Stuart Sumida standing in the quarry and Thomas Martens crouched to his right. The Diadectes fossil was found in the corner opposite Stuart’s left shoulder, which is out of sight in this image. Photo by Dave Berman, 1993.

The team’s collective attitude changed when Stuart knocked off a chunk of bone-bearing rock from a bench in the quarry corner while shoveling away rock rubble. Careful examination of the fragment revealed part of the top of a roughly five-inch-long skull. We have since joked that Stuart gave it a lobotomy. While collecting the large block of rock containing the remainder of the skull, another piece of rock popped off the the edge of the block adjacent to the quarry wall. This piece had vertebrae in it. The team then realized that only the front portion of the animal was in the block freed from the quarry. The rest of the fossil skeleton remained in the quarry wall. Thomas later excavated the rest of the specimen and shipped it separately to Carnegie Museum of Natural History (CMNH).

You can watch Dave and Stuart excavate the fossil-bearing block by clicking on the video link at the end of this post.

Based on the shape of both the exposed teeth in the broken skull and the exposed vertebrae, Dave and Stuart were able to identify the fossil animal as the genus Diadectes. Thomas had already collected a juvenile skull and other bones of Diadectes before his collaboration with Dave, but the specimen discovered in 1993 was by far the most complete and best preserved.

Skeleton of Diadectes absitus. Some of the limb bones are preserved on the underside of the block. Photo provided by Thomas Martens.

Once my preparation of the specimen was completed, which took a little over a year, Dave, Stuart, and Thomas begin their detailed study and description of the fossil. They determined that it represented a new species, which they named Diadectes absitus. “Absitus” is Latin for distant or far, in reference to the species being the first occurrence of Diadectes outside of North America. The generic name Diadectes was coined in 1878 by the famous paleontologist Edward Drinker Cope, and is a combination of the Greek “dia,” meaning crosswise, and “dēktēs,” meaning biter, in reference to its broad teeth. Other species of Diadectes occur in similar-aged rocks in the American southwest, and a few specimens are known from the Tri-State area of Pennsylvania, Ohio, and West Virginia.

Diadectes is a member of the group Diadectomorpha, which has oscillated between being considered a member of Amphibia or Amniota. Amphibians lay their eggs in water, which then hatch into tadpoles that later undergo metamorphosis. Today this group includes frogs, salamanders, and caecilians (limbless, worm-like burrowing amphibians). In contrast, amniotes either lay their eggs on land, like reptiles and birds do today, or the embryo develops sufficiently in the mother for live birth, as in most mammals. Except in rare cases, the type of developmental pathways of fossil animals cannot be determined because they are rarely preserved with their eggs or fetuses. Paleontologists instead study a variety of preserved features to determine group membership. As an example, amphibians typically have four fingers, whereas amniotes generally possess five.

Diadectes and its close relatives were herbivorous, that is, they ate plants. Their spatulate, incisor-like front teeth project forwards and were adapted for cropping vegetation. Longitudinal, parallel striations on their broad cheek teeth suggest that Diadectes could move its lower jaw fore and aft to grind plant matter against its upper jaw teeth, a motion called propalinal.

Skull of Diadectes absitus in right lateral (= right side) aspect. Notice the forward-angled front teeth and the bulbous cheek teeth. A black pen was used to mark the boundaries of individual bones in the skull, which aided study of the animal. Modified from photo provided by Thomas Martens.

The presence of an enlarged torso and teeth adapted for grinding tough vegetation are evidence that Diadectes absitus likely consumed a diet of high-fiber plants. Animals that eat high fiber plants, such as cows, have enlarged torsos framed by a rounded rib cage to hold large guts for processing plant cellulose through fermentation by microorganisms.

Diadectes absitus lived at a time when herbivores were just beginning to evolve. One of the oldest known herbivores is the diadectomorph Desmatodon hollandi, which lived about 305 million years ago, whereas Diadectes absitus lived roughly 290 million years ago. We discovered a surprisingly high number of herbivores at the Bromacker.

Teeth of one of the oldest known herbivores, the diadectomorph Desmatodon hollandi. This specimen was discovered in Pitcairn, PA by Percy E. Raymund (Assistant Curator, Section of Invertebrate Paleontology) in 1907 and named in honor of Dr. William Holland, the second Director of CMNH. The teeth of Desmatodon are very similar to those of Diadectes absitus. Photo by the author, 2018.

A cast of the skeleton of Diadectes absitus is exhibited in the Fossil Frontiers display case in the Dinosaurs in Their Time exhibition. Be sure to look for these once the museum re-opens. And stay tuned for my next post, which features another diadectomorph, Orobates pabsti.

Photograph of a model of Diadectes absitus made by the Museum der Natur, Gotha exhibit preparator Peter Mildner. Photo provided by Thomas Martens.

Dave and Stuart excavate the fossil-bearing block (video)

Amy Henrici is Collection Manager in the Section of Vertebrate Paleontology at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

Western Bird, Eastern Waters

If you enter Bird Hall from the Grand Staircase Balcony, the first taxidermy mount you’ll encounter is an American Avocet, an elegant species commonly associated with the shallow margins of western lakes. The life-like preserved remains of the 20-inch high, long-legged, and long-billed bird occupy the lower-right position within a display case visually dominated by a flamingo. “Adaptations for Feeding” is the comparative theme for the display’s six preserved birds, a select group the Avocet earned membership among by virtue of its long, reed-thin, and slightly up-turned bill.

The species, known to science as Recurvirostra Americana, feeds by swinging its bill scythe-like through the water to capture small invertebrates. Remarkably, on a recent evening, I was able to observe an Avocet demonstrate the technique in waters less than three miles from the museum.

American Avocet (lower left) downstream from boats moored at the South Side Marina. Credit: Amy Henrici.

On July 24, a local birder used an online forum to share a lunchtime sighting of an avocet in the shallow waters of Monongahela River near the Birmingham Bridge. The report enabled other birders to make quick plans for riverside visits, and by 7:00 p.m. I was among a handful of binocular-bearing observers who watched the bird for 30 minutes from a South Side path before it flew upstream and out of sight.

American Avocet in Monongahela waters. Credit: Amy Henrici.

In the following days I tried to retroactively enrich the firsthand observation. I read the American Avocet account on the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s informative All About Birds website, re-read relevant passages in The Wind Birds, author Peter Matthiessen’s 1967 tribute to the diverse tribe of species collectively termed “shore birds,” and finally, made a narrowly-focused visit to Bird Hall.

Kneeling on the marble floor in front of the avocet, I was able to inspect a key physical feature that days earlier had been concealed by murky Monongahela waters – the species’ fully webbed feet. Studying anatomical details on taxidermy mounts can enhance field observations of wildlife. This statement can be something of a mantra for natural history museum educators.

Patrick McShea works in the Education and Visitor Experience department of Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Bromacker Project Part VI: Seymouria sanjuanensis, the Tambach Lovers

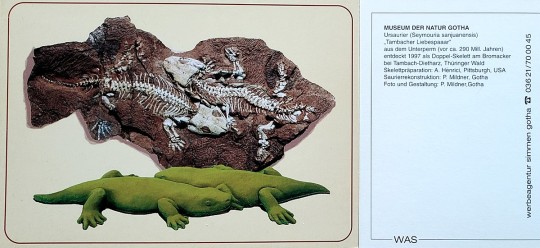

Two exquisitely preserved, nearly complete adult skeletons of Seymouria sanjuanensis that were discovered in the Bromacker quarry in 1997. Photo by Dave Berman.

At lunchtime on the last day of the 1997 field season, Thomas Martens discovered the two exquiste specimens shown above, the only fossils found that year. Thomas had uncovered a piece of the hip region with some attached vertebrae that resembled, once again, those of the ancient amphibian Seymouria. Because our work time was limited, we estimated the length of the specimen and rushed to extract it from the quarry. When we flipped the block over, a few pieces of rock fell out, revealing a series of vertebrae of a second individual in the block. We were thrilled to learn that Thomas had discovered two specimens of Seymouria. We put the rock pieces back in place and quickly finished plastering the block. There was just enough time for Dave, Stuart Sumida, and I to return to our hotel, clean up, quickly pack, and meet Thomas, his family, and his fossil preparator Georg Sommer for a celebratory dinner. What a great way to end the field season.

Working in tight quarters to quickly extract the Seymouria specimens discovered at lunchtime on the last day of the field season. Clockwise from right: Georg Sommer, Dave Berman, and the author. Photo by Stuart Sumida, 1997.

Seymouria had already been known from the Bromacker quarry. Thomas had discovered and identified two skulls in 1985, fossils he brought with him when he came to Carnegie Museum of Natural History (CMNH) in 1993 to study for six months with Dave Berman under a CMNH-financed fellowship. Both skulls were of juvenile individuals. Of the two known species of Seymouria, Dave and Thomas were excited to discover that the Bromacker skulls were nearly identical to those of Seymouria sanjuanensis. The 1997 lunchtime discovery of the two complete adult specimens confirmed the identification of the Bromacker Seymouria as S. sanjuanensis.

The first discovered species of Seymouria was Seymouria baylorensis, from near Seymour, Baylor County, Texas, from which its name was derived. Seymouria sanjuanensis was first found in San Juan County, Utah, by Dave Berman and the field team he was leading as a graduate student at the University of California, Los Angeles. Dave’s advisor, Dr. Peter Vaughn, named it Seymouria sanjuanensis in reference to the county of discovery. Another discovery of five specimens of this species preserved together was made by Dave in New Mexico in 1982.

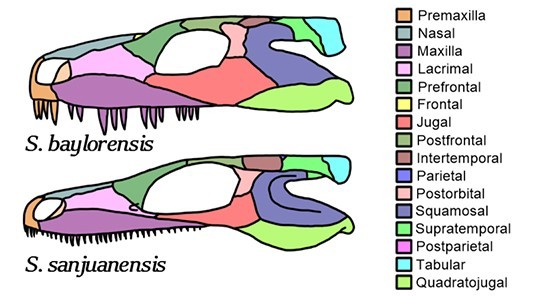

Comparison of the skulls of Seymouria baylorensis (top) and S. sanjuanensis (bottom). The individual bones of the skull are color coded. Skulls scaled to same size. Image from Wikimedia Commons.

Seymouria baylorensis is geologically younger than S. sanjuanensis and has a more robust skull, larger and fewer teeth of variable size, and a subrectangular postorbital bone compared to the chevron-shaped postorbital of S. sanjuanensis.

Seymouria is considered a terrestrial amphibian that only returned to water to breed. Its strongly built skeleton provided the support needed to move on land. With its numerous, slender, pointed teeth, S. sanjuanensis most likely ate insects and small land-living vertebrates. We know that the Bromacker Seymouria didn’t consume fish, because not a single fish fossil, scrap of fish fossil, or fish coprolite (fossil poop) has ever been found at the Bromacker quarry. Study of the rock deposits preserving the fossils at the Bromacker indicate a lack of permanent water, which would explain the absence of fish.

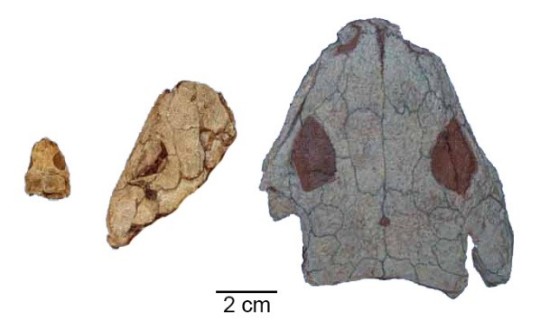

Growth series of skulls of Seymouria sanjuanensis from the Bromacker Quarry showing (left to right) early juvenile, late juvenile, and adult growth stages. Photos by the author, 2006.

Conditions for breeding must have been favorable in the Tambach Basin, the ancient basin where sediments preserving the Bromacker fossils accumulated, because several juvenile specimens of Seymouria are known. The smallest is a skull measuring about 3/4 of an inch long. In a study led by our colleague Josef Klembara (Comenius University, Slovak Republic), we determined that the smallest individual was post-metamorphic—in other words, no longer a tadpole—based on the presence of certain ossified bones in the skull. In tadpoles, these skull elements are cartilaginous; that is, they haven’t yet turned to bone.

Five skeletons of Seymouria sanjuanensis preserved together were discovered in north central New Mexico by Dave Berman in 1982. These specimens are on display in CMNH’s Benedum Hall of Geology, in the “What is a Fossil?” case. Photo by the author, 2013.

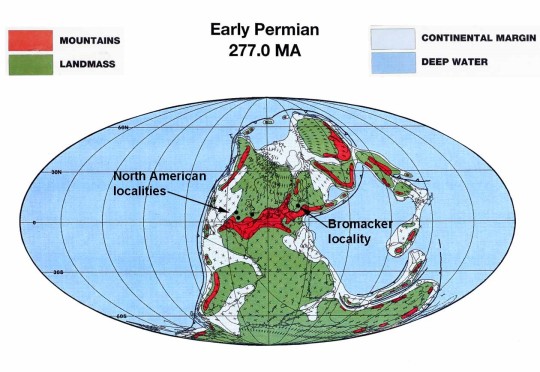

The discovery in Germany of the same species of Seymouria previously known only from New Mexico and Utah has important implications in terms of paleobiogeography (the study of the distribution of species in space and time). At the time S. sanjuanensis was alive, the continents were merged to form the supercontinent Pangaea. The presence of S. sanjuanensis across Pangaea, north of a roughly east-west trending mountain range, indicates that climatic or physical barriers (e.g., deserts, inland seas, mountain ranges) didn’t prevent its dispersal.

Map showing the arrangements of the continents in the Early Permian. The locality where Seymouria occurs in present-day New Mexico, Texas, and Utah and the Bromacker locality in present-day Germany are indicated. Map modified from Scotese, 1987.

The two Seymouria specimens preserved together were a big hit in the local region in Germany. Museum der Natur (MNG) exhibit preparator Peter Mildner nicknamed them the “Tambacher Liebespaar” (“Tambach Lovers”) after a painting entitled “Gothaer Liebespaar” (“Gotha Lovers”) on exhibit in the Herzogliches Museum of the Stiftung Schloss Friedenstein (also the parent organization of MNG). This name caught on and is fondly used by our German friends and colleagues. Peter even made a fleshed-out model of the two Seymouria specimens in their death pose. The proprietor of the hotel in which we stayed hung a copy of the model of the Tambach Lovers and a framed collage of newspaper articles featuring the Bromacker on a wall in one of the hotel rooms, which she named the “Präparation Suite” (i.e. “Preparation Suite” in reference to the preparation of fossils). I often stayed in this room.

The painting entitled “Gothaer Liebespaar” (“Gotha Lovers”), which is on display at Herzogliches Museum of the Stiftung Schloss Friedenstein, Gotha, Germany. Image from Wikimedia Commons and provided by Thomas Martens.

Postcard showing the Tambach Lovers. The postcard was made for and sold by the Museum der Natur, Gotha. Photo of the postcard by the author, 2020.

Stuart Sumida (left) and Heike Scheffel, proprietor of the Hotel Wanderslaben where we stayed (right), with the model of the Tambach Lovers in the “Präparation Suite.” The framed collage to the right of the model holds newspaper articles featuring the Bromacker project. Photo by the author, 2003.

A cast of the Tambach Lovers specimen and a model of Seymouria sanjuanensis are exhibited in the Fossil Frontiers display case in CMNH’s Dinosaurs in Their Time exhibition. Be sure to look for them once the museum re-opens. And stay tuned for my next post, which will feature the unusual bipedal reptile Eudibamus cursoris.

For those of you who would like to learn more about Seymouria sanjuanensis, here is a link to the publication describing the 1997 specimens: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1671/0272-4634(2000)020%5B0253%3AROSSSF%5D2.0.CO%3B2.

Amy Henrici is Collection Manager in the Section of Vertebrate Paleontology at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

#Carnegie Museum of Natural History#Bromacker Quarry#Seymouria sanjuanensis#Fossils#Paleontology#Vertebrate Paleontology

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Eorubeta: A Mysterious Ancient Frog Revealed

By Amy Henrici

I recently completed a project on fossil frogs from east central Nevada that my collaborators and I identified as the enigmatic Eorubeta nevadensis Hecht, a species that was originally based on a single, poorly preserved specimen that had been discovered in a well core.

The new collection of Eorubeta came from the Sheep Pass Canyon area about 12.5 miles northeast of the well core site. Peter Druschke discovered fossil frogs here in 2005 while working on his PhD dissertation on a rock unit known as the Sheep Pass Formation. Peter and fellow University of Nevada Las Vegas graduate students Josh Bonde and Aubrey Shirk and colleagues Dick Hilton and Tina Campbell (of Sierra College in Rocklin, California) collected additional fossil frogs in subsequent years. I was very fortunate to be invited to join the team, and we collected over 60 specimens for Carnegie Museum of Natural History in 2012, 2013, and 2016.

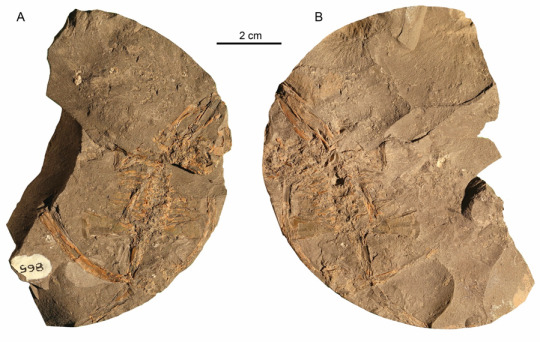

Part (A) and counterpart (B) of the first-known specimen of the fossil frog Eorubeta nevadensis. This specimen resides in the Vertebrate Paleontology collection of the American Museum of Natural History in New York.

The field site lies in the South Egan Range Wilderness Area of east central Nevada. Being a wilderness area, we could only drive on existing roads, and had to hike nearly a mile to the fossil-producing slopes. The climate in Nevada is challenging to work and camp in, with temperatures reaching over 100 degrees Fahrenheit during the July 2013 field season and nighttime temperatures dipping into the high 20s during the November 2016 season.

Road into the South Egan Range Wilderness area, White Pine County, Nevada. The area burned three months prior to the 2012 field season. The fire cleared vegetation from the fossil-producing slopes, making it easier to find fossils, though burnt tree branches left us streaked with charcoal.

When Eorubeta was originally named, the rock unit from which this frog came (Member B of the Sheep Pass Formation) was thought to date to a time interval known as the Early Eocene (56–47.8 million years ago). More recently, however, Peter has determined that this unit was probably latest Cretaceous–Paleocene (72.1–56 million years ago) in age instead. It is thus possible that Eorubeta spanned the Cretaceous–Paleogene boundary (66 million years ago) and survived the infamous asteroid impact that caused the extinction of non-avian dinosaurs and many other animal and plant species.

Two of the recently-collected specimens of Eorubeta nevadensis.

Peter determined that the beds in which the fossil frogs were preserved were part of a very high-elevation lake system (1.4–2.2 miles in elevation), similar in this way to today’s Lake Titicaca located in the Andes Mountains on the border of Bolivia and Peru. To date, Eorubeta is the only fossil frog known to have inhabited such a high-elevation environment. Most fossil frogs from this time come from prehistoric river and lake systems situated on coastal plains. The discovery of Eorubetasuggests that ancient frogs probably inhabited a greater variety of environments than the current fossil frog record indicates.

The first specimen discovered by Peter in 2005 indicates that Eorubetamay have reached a considerable size, though the fossil’s extremely weathered condition makes its identification uncertain. An analysis of the relationships of Eorubeta to other frogs reveals that it is more archaic than spadefoot toads, Neobatrachia (a group known as modern frogs), and their relatives.

Top: the largest known specimen of Eorubeta. Bottom: Peter Druschke, the team geologist who discovered the specimen.

To learn more about Eorubeta, please follow this link to our paper recently published online in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/02724634.2018.1510413.

Amy Henrici is the collection manager for the Section of Vertebrate Paleontology at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

#Carnegie Museum of Natural History#Eorubeta#Paleontology#Vertebrate Paleontology#Sheep Pass Canyon#Frog#Ancient Frog

13 notes

·

View notes