#owen tudor

Text

♕ @dailytudors: TUDOR WEEK 2023 ♕

Day Five: Most Used Tudor Related Resource >> My slowly expanding collection of Tudor nonfiction books.

#tudorweek2023#margaret beaufort#owen tudor#jasper tudor#margaret tudor#mary tudor#katherine of aragon#anne boleyn#jane seymour#anne of cleves#kathryn howard#catherine parr#my edits#dailytudors#yes I know i don't own any of the latter generation/s but I did have a huuuuge bookdepository wishlist before it shut down#any recommendations for a website like that please let me know

217 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tudor Week 2023

To celebrate our belated three-year anniversary we are hosting Tudor Week 2023. This is going to be hosted from Monday the 31st of July to Sunday the 6th of August.

The week will go as follows:

Day 1 - Monday, 31st of July : Favourite Tudor Rivalry

Day 2 - Tuesday, 1st of August : Favourite Female Tudor Family Member

Day 3 - Wednesday, 2nd of August : Best Tudor Myth

Day 4 - Thursday, 3rd of August : Favourite Male Tudor Family Member

Day 5 - Friday, 4th of August : Most Used Tudor Related Resource

Day 6 - Saturday, 5th of August : Favourite portrayal of a Tudor Family Member

Day 7 - Sunday, 6th of August : Favourite Tudor Mentor and Mentee relationship (can be a Tudor familial relationship, or a Tudor and a courtier relationship)

This can cover all events and media that a Tudor family member is present, so from Owen Tudor to Elizabeth Tudor, and may include spouses and acknowledged children of direct members of the Tudor family (if unsure who we cover please check our Family page). We have attempted to make it as broad as possible and no pressure if you are late with some of the days, we will still reblog.

Previous Years: 2021, 2022

Be sure to tag your posts TudorWeek2023 and DailyTudors, looking forward to seeing your posts!

- The Team at DailyTudors

#tudorweek2023#henry vii#henry viii#edward vi#mary i#elizabeth i#owen tudor#catherine de'valois#edmund tudor#margaret beaufort#jasper tudor#catherine woodville#elizabeth of york#arthur prince of wales#katherine of aragon#margaret queen of scotland#james iv of scotland#archibald douglas#henry stuart#anne boleyn#jane seymour#anne of cleves#kathryn howard#catherine parr#mary queen of france#louis xii#charles brandon#henry fitzroy#announcement

138 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mystery also surrounds Owen Tudor's marriage, but there is no question as to its validity or the legitimacy of his offspring. Richard III's proclamations described Tudor as a bastard; his marriage, however, was not disputed.

Ralph Griffiths, "Tudor, Owen [Owain ap Maredudd ap Tudur] (c. 1400–1461)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004, updated 2008)

#I love that you can just say#“Catherine de Valois and Owen Tudor were married and their children legitimate source: Richard III himself”#but ricardians will still be mad and argue about it#owen tudor#catherine de valois#edmund tudor#jasper tudor#historian: ralph griffiths

32 notes

·

View notes

Photo

❝ The effigy that lay on Catherine of Valois’ coffin at her funeral can still be seen in Westminster Abbey, dressed in her red painted shift, while her body lies under the altar in Henry V’s chantry. Sadly, however, Owen Tudor, with whom this story also began, is nowhere remembered. After the monastery of Greyfriars was dissolved in 1538, his tomb vanished. The ancestor of all the Tudors monarchs, and every British monarch since, now lies in a grave beneath a 1970’s housing estate. Perhaps, like Richard III, he will find someone willing to find him a more dignified place. For those who lived under the Tudor kings and queens, what mattered was not their Welsh origins of the Tudors, but the royal marriage of the union of the rose to which James was proclaimed heir in 1603: the symbol of peace, harmony and stability. For us, however, the name of the rose is Tudor, and the family story that began with Owen ends with a salute to the memory of a clumsy servant, who with a pirouette and a trip, fell into the lap of English history.Leanda de Lisle, Tudor: The Family Story (casting idea by @ourgraciousqueen)

291 notes

·

View notes

Quote

It is [Katherine of Valois]'s refusal to submit to male authority, as much as her wish to remarry, that lays her open to the accusation that she was governed by her lust, because her behaviour, from the lords’ perspective, was unwise, ill-advised, and reckless. In addition to Katherine’s disobedience they likely also felt disappointed in her. She had been married to a revered king, around whose memory an intense culture of commemoration flourished. Even without the potential problem of an influential stepfather for Henry VI, Katherine’s wish to marry any man, let alone a mere Welsh squire, was a profound betrayal of Henry V’s memory.

Katherine J. Lewis, “Katherine of Valois: The Vicissitudes of Reputation” | Later Plantagenet and the Wars of the Roses Consorts: Power, Influence, and Dynasty (2023)

It is conceivable that Katherine’s actions were viewed by those lords as proof of her wrongheadedness and expressed by them in the misogynistic terms conveyed by the chronicler. While this may have been how Katherine was regarded by some at court, there is no evidence that this was how she was viewed more widely. As noted above, her marriage was not publicly known, and she was not in disgrace.

#catherine of valois#owen tudor#henry v#historicwomendaily#historian: katherine lewis#later plantagenet and the wars of the roses consorts

99 notes

·

View notes

Text

#owen tudor#jasper tudor#henry vii#arthur prince of wales#margaret tudor#henry viii#mary tudor#mary i#elizabeth i#edward vi#poll

43 notes

·

View notes

Photo

TUDOR WEEK 2022

DAY 5 MOST UNDERRATED TUDOR FAMILY MEMBER(S) → CATHERINE DE VALOIS

Catherine de Valois was the daughter of Charles VI and Isabeau of Bavaria. During the Hundred Years War, Catherine was contracted to marry Henry V of England as part of the peace treaty, known as the Treaty of Troyes. Their marriage was intended to pave the way for France and England to cease fighting with Henry V on the throne of England and France. This didn’t happen. Henry V died two years later leaving behind not only the widow Catherine, but their infant son, Henry VI. At some point after Henry V died, Catherine entered into a relationship with Owain Tudor. Owain ap Maredudd ap Tudur (or Owen Tudor) was a Welsh courtier from a distinguished family from Penmynydd. At the time of their relationship, Owain was installed as either the keeper of her wardrobe or household. Altogether, Catherine had three sons with Owain and the couple remained together until her death in 1437. Her sons Edmund and Jasper were close with their half-brother, King Henry VI. While there is usually doubt as to the legitimacy of Owain and Catherine’s marriage, an entry in the Parliament Rolls states that Edmund and Jasper (the two eldest sons of Owain and Catherine) were conceived and born within wedlock. This would suggest that some form of evidence or proof of marriage was the basis of this declaration.

For a family tree for Catherine and her children see this → post

I want to thank @richmond-rex for their helpful information on the legitimacy of Catherine and Owain’s marriage and their children. If you love Tudor content, go follow!

Image

1. Catherine of Valois by Edward Hargrave, 1842.

#tudorweek2022#dailytudors#catherine de valois#catherine of valois#owain tudur#owain tudor#owen tudor#house of tudor#tudorerasource#tudoredit#perioddramaedit#periodedit#perioddramasource#gifshistorical#userperioddrama#userbennet#historicwomendaily#women in history#historical ladies#historical women#henry v#henry vi#tudor history#gifs: mine#richmond-rex

259 notes

·

View notes

Note

After reading your article, marriages like Eleanor and Humphrey, Katherine and John, Henry VIII and Ambeline are described as women seducing men, and men being victims... But marriages like Owen Tudor and Catherine, Richard Woodville and Jacqueta in Luxembourg, will have completely ignored the subjective initiative of women, and the description of men seducing women should be class/gender discrimination?

Hi anon, I think you're asking about what kind of narratives there were around the marriages between men and women of significantly higher status, the inverse of the type of relationships I was talking about in this blogpost I made on my sideblog that focused on Eleanor Cobham, where women married men of much higher status than themselves.

There seems to be comparatively little scholarship in this area and it would be fascinating to see what commonalities and links a study would produce. The marriage of men to women of significantly higher status than themselves does appear to have been fairly common but does not seem to have generated the same amount of commentary and infamy as the relationships between women who married men of significantly higher status. I don't mean that they didn't contract comment but that there was little sustained comment - who remembers Alice de Lacey and Eubulus le Strange? Katherine Woodville and Sir Richard Wingfield? The only high profile case I can think of is Joan of Kent and Thomas Holland.

From what I could find, there does not seem to be the equivalent narrative of the man of lesser status seducing or bewitching the high-status woman into marriage. Instead, what seems to be the common theme is, as Katherine J. Lewis says, "a standard medieval antifeminist notion: that women were naturally inclined to lust and rendered irrational to it."

Lewis was talking specifically about the case of Catherine de Valois. One contemporary chronicler remarked that she was "unable to fully control her fleshly passions" when she married Owen Tudor and even chastises her for keeping the marriage secret "so she did not claim honourable title [of marriage] during her lifetime". Tudor was described by another chronicle as "no man of birthe nother of lyflode", implying his unworthiness. But there seems to have been little rancour or blame directed at Tudor.

It's not until the 16th century where the image of Catherine as governed by her lust became the dominant narrative around her remarriage, perhaps because the rise of the Tudor dynasty and Henry VIII's marital life lent itself to it. One notable example is Edward Hall, who in 1548 described Catherine as:

beyng young and lust, folowyng more awne appetite, then frendely counsaill and regardyng more her priuate affecion then her open honour

He describes Tudor, on the other hand, as a "goodly gentilman & a beautyful person, garnished with many Godly gyftes, both of nature & of grace" - so the issue here is not that Tudor is a social-climber but that Catherine is at the mercy of her sexual desires. Probably the most extreme example of this is Nicholas Fox's claim that Catherine "bey[ed] like a very dronkyn whore" in bed with Tudor - a factoid often gleefully repeated by historians and commentators to proclaim Tudor's sexual prowess despite the fact that Fox made the claim in 1541 and is far from a reliable source. The fact that it has been almost universally used to celebrate Tudor by demeaning Catherine shows how long-lasting this type of narrative is. Polydore Vergil similarly describes Catherine dismissively as "yonge in yeres, and thereby of lesse discretion to judge what was decent for estates" and then focuses on Tudor's lineage and good qualities. Kavita Mudan Finn notes that he "succeeds in suppressing what on the surface to appears to be her agency - a second marriage of her own free will - by literally changing the subject to Owen, and by extension, Henry, Tudor". This same suppression of Catherine's agency appears again in Michael Drayton's Englands Heroicall Epistles where Catherine appears to be acting on her own initiative, wanting Tudor for herself, but Drayton has Tudor displace Catherine's agency by citing destiny as the impulse behind their union. Catherine "is reimagined as a 'a Royall Prize' for Tudor to claim", per Finn. In short, Catherine appears to be cast as oversexed and/or uncontrollable while Tudor's individual qualities and descent are celebrated and their union is seen as governed by destiny and fate.

Joan of Kent has fared similarly to Catherine in that she is primarily remembered as governed by her lust. Famously described as Froissart as "a woman more beautiful and amorous than any in the realm" and by Adam of Usk as a "woman given to slippery ways", Joan had married Thomas Holland clandestinely, then been convinced by her family to marry William Montagu (the son of the Earl of Salisbury). Around eight years later, Holland then petitioned the papacy to return Joan to him, resulting in a public scandal. When Holland died in 1360, Joan made another shocking match, this time marrying Edward of Woodstock, Edward III's eldest son and heir known to history as "the Black Prince". Joan was sometimes referred to the "Fair Maid of Kent" or "the Virgin of Kent", probably sarcastically. Thomas Austin's wife was alleged to claim that Joan's son with the Prince, Richard II, was "nevere the prynses son and ... his moder [i.e. Joan] was nevere but a strong hore". Froissart recorded a conversation between Richard and his usurper, Henry IV, where Henry alleged that a bastard gotten in adultery. W. Mark Ormrod also suggested that various narratives about Joan in the Peasants Revolt built on her carnal reputation and may have reflected even more salacious tales floating around. Thomas Walsingham emphasises Joan's other alleged, inordinate appetites around the time of her death - gluttony ("hardly able to move about because she was so fat") and a love of luxury.

It is, however, very difficult to determine how much of Joan's reputation was shaped to her marriage to a man of significantly lower status or how much it was shaped by her marriage to the man, at the time, was to be the next king of England and to whom her marriage was both scandalous and unconventional. Likely, her reputation was formed by both marriages, both feeding the other. The deposition of her son also meant that her reputation was used as a way of slandering him. Thomas Holland, on the other hand, barely seems to be mentioned, let alone criticised - even if he was in his mid-20s when he married the 12 year old Joan. In fact, Henry Knighton's chronicle positions Holland as seduced by her, crediting Holland's "desire for her" as the cause that she had been divorced from her second husband, Montagu.

Jacquetta and Richard Woodville do not seem to have drawn the same level of commentary. Lynda J. Pidgeon notes that "the marriage ... aroused no comment from English chroniclers until after the couple’s daughter, Elizabeth, married King Edward IV in 1464". though it was recorded in by continental chronicles, such as Enguerrand de Monstrelet, who recorded recorded:

In this year [1436], the duchess of Bedford, sister to the count de St. Pol, married, from inclination, an English knight called sir Richard Woodville, a young man, very handsome and well made, but, in regard to birth, inferior to her first husband, the regent, and to herself…

This has similar echoes to Hall's and Vergil's comments about the marriage of Catherine and Owen Tudor - Jacquetta marries from "inclination" a man inferior to herself but who is otherwise "very handsome and well-made". Hall includes the story of their marriage immediately after his account of Catherine and Tudor, which, as Finn says, "hints at a growing interest - and indeed, anxiety - about women's desires". Like Catherine, Jacquetta is described as marrying Woodville "rather for pleasure then for honour" and "without coū∣sayl of her frendes". Her family is said to disapprove but can do nothing - sentiments also found in Monstrelat and Jean de Wavrin. Rather than dwelling on Woodville's qualities as he does with Tudor's, Hall describes Woodville "lusty" and notes that he was made Baron Rivers, which may indicate . He does, however, mention the marriage of their daughter, Elizabeth, to the future Edward IV, a subject which he promises to return to.

The continuation of Monstrelet's chronicle links Jacquetta and Woodville's marriage to that of their daughter, Elizabeth Woodville's marriage to Edward IV, "thus linking these two unorthodox women together", per Finn. Here's what this continuation says:

After the death of the duke, his widow following her own inclinations, which were contrary to the wishes of her family, particularly to those of her uncle, the cardinal of Rouen, married the said lord Rivers, reputed the handsomest man that could be seen, who shortly after carried her to England, and never after could return to France for fear of the relatives of this lady.

It is likely that Jacquetta's unconventional second marriage helped render Jacquetta's reputation suspect and tempting to speculate that that it rendered her vulnerable to the accusations that she had used witchcraft to make Edward IV marry her daughter, Elizabeth Woodville. The unpopularity in France and Burgundy of her first marriage to John of Lancaster, Duke of Bedford and Regent of France may have also played into this view. Ricardians have certainly framed her as her as a seductress and her family as scheming, power-hungry social climbers in that regard - while also treating her as driven by her lust for Woodville. However, there is no evidence that this was the view of Jacquetta at the time, either in England or in France.

Richard Woodville is unique amongst the three men I've mentioned in that he seems to have been reviled as a man "brought up from nought", along with the rest of his and Jacquetta's prodigious offspring. This view has been spurred on by Ricardian historians that have reviled Elizabeth Woodville, where the entire family is depicted as a brood of grasping social climbers. An invasive species, if you will. I think it is likely that Jacquetta and Richard Woodville's marriage has helped furnish this view, particularly for Woodville himself. However, this particular image of Woodville and his children only seems to emerge with Elizabeth's marriage to Edward IV and the tensions between Edward, Woodville, George, Duke of Clarence and Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick ('the Kingmaker'), rather than Woodville's marriage to Jacquetta.

In short: the tendency seems to be depict the high-status woman as indulging in her own sexual desires and acting on her own will, disregarding reason, counsel and sense, while the man of lesser-status is considered handsome but bears little or no responsibility for seducing the woman. He is of less interest to contemporary chroniclers. Woodville seems to be an exception, rather than the norm, in being seen as guilty of social climbing and there it is the marriage of his daughter, not his own marriage, that gave that reputation. Owen Tudor, as the patriarchal originator of the Tudor dynasty, was celebrated by Tudor-era writers for his qualities and Welsh lineage - it would be easy to conclude that had he not been the grandfather of Henry VII, he would be entirely forgotten.

There do not seem to be any contemporary claims than Tudor, Holland or Woodville seduced, bewitched or raped their wives, whatever historical fiction novelists or pop historians claim. However, it should be noted that there are many cases where other high-status women could be abducted and forced into marriage. One example is Alice de Lacey, Countess of Lancaster. For those cases, I suggest reading Caroline Dunn's Stolen Women. It is far too long and complicated subject to summarise in a tumblr post.

Sources:

Caroline Dunn, Stolen Women in Medieval England: Rape, Abduction, and Adultery, 1100–1500 (Cambridge University Press, 2017)

David Green “‘A woman given to slippery ways’? The reputation of Joan, the Fair Maid of Kent”, People, Power and Identity in the Late Middle Ages: Essays in Memory of W. Mark Ormrod (Routledge, 2021, eds. Gwilym Dodd, Helen Lacey, Anthony Musson)

Katherine J. Lewis, “Katherine of Valois: The Vicissitudes of Reputation”, Later Plantagenet and the Wars of the Roses Consorts: Power, Influence, and Dynasty (eds. J. L. Laynesmith and Elena Woodacre, Palgrave 2023)

Kavita Mudan Finn, The Last Plantagenet Consorts: Gender, Genre, and Historiography, 1440-1627 (Palgrave Macmillan, 2012)

W. Mark Ormrod, "In Bed With Joan of Kent: The King's Mother and the Peasants Revolt", Medieval Women: Texts and Contexts in Late Medieval Britain (ed. Jocelyn Wogan-Browne, Rosalynn Voaden, Arlyn Diamond, Ann Hutchison, Carol Meale, and Lesley Johnson, Brepols 2000)

Lynda J. Pigdeon, Brought Up Of Nought: A History of the Woodville Family (Fonthill 2019)

#god i hope this makes sense as i'm tired and i've been working on this for too long#also i don't know a lot about the woodvilles so most of my discussion of them is drawn from a quick research session so#jacquetta of luxembourg#richard woodville#joan of kent#thomas holland#catherine de valois#owen tudor#asks#anonymous#text posts

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

→ history + owen tudor and catherine of valois

requested by anonymous

Queen Catherine, being young and lusty, following more her own wanton appetite than friendly counsel and regarding more private affection than prince-like honour, took to husband privily a gallant gentleman and a right beautiful person, imbued with many goodly gifts both of body and mind, called Owen Tudor. — Raphael Holinshed, Chronicles of England, Scotland, and Ireland

#historyedit#owen tudor#catherine of valois#medieval history#15th century#english history#house of tudor#house of valois#historical fancast#*history#*requests#*mine#*historical couples#cw: blood#sorry for the delay!

265 notes

·

View notes

Text

She speaks English well but her accent marks her out, he speaks English well but his accent marks him out. They are outsiders, strangers in a land not their own. Her fingertips ache to touch him, to hold his hand and feel that she is not alone.

the world anew by heartofstanding

This one line is a rather beautiful summation of why the beginnings of Catherine de Valois and Owen Tudor's relationship is so relatable. It is so human, that need for connection in a strange land.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

On this day: February 2th, 1461: the battle of Mortimer's Cross

The battle of Mortimer's Cross was fought at the end of winter and was rooted in Welsh politics. It was fought at the border between Wales and Herefordshire.

On the one side, the new duke of York since the execution of his father a month ago: Edward Plantagenet. Edward was Earl of March before, a huge lordship in Wales and the Welsh Marches, commanding many retainers. Two of its most prominent retainers were there with him: William Herbert and Walter Deveureux.

William Herbert was an ambitious Welshman, and Walter Devereux was a prominent Hertfordshire knight, both dedicated to the House of York.

Facing them, the Lancastrian faction was led by Jasper and Owen Tudor. Jasper, as Earl of Pembroke and half-brother of the king, commanded great influence in southern Wales. His brother Edmund clashed with Devereux in 1456 as York tried to rise in influence in the region. James Butler was with them as Earl of Wiltshire and Ormond. The Butler family was powerful in Ireland and headed the Lancastrian faction in an unstable island where Yorkist influence was prominent. He fought with the Tudors. However, his marriages with the Beauchamp and Beaufort families gave him lands and interests in the Welsh Marches and the West Country, making him a powerful magnate outside of Ireland.

The stakes were high. Edward IV was the only adult Yorkist alive capable of championing the Lancastrians. More locally, Jasper and Owen had a grudge against Deveureux and Herbert, who waged war against their interest in 1456.

The Lancastrians were probably less numerous than the Yorkists, but their aggressive strategy gave them a shot at beating them.

Butler attempted an aggressive encirclement of the left flank, forcing Devereux to retreat. Meanwhile, Pembroke faced the duke of York. Owen's attempt at crushing Herbert and forcing an encirclement could have changed History, but it failed, and his 'battle' began to rout. Herbert's decisive hold allowed a Yorkist victory and the capture and execution of Owen Tudor.

This victory would mean much for the Yorkist. Everyone on the Yorkist side was eventually promoted. Deveureux and Herbert would become lord in 1461, just like Sir Humphrey Stafford, who fought with them. York would become king of England a few months later. The reverse was also true, as Jasper Tudor lost his earldom in favor of the Herberts (1469) and Butler lost his life a few months later and his family lost his earldom of Wiltshire with it. Jasper would regain his lands only after the battle of Bosworth twenty-four years later, in which Walter Deveureux, as lord Ferrers, would die fighting for Richard III.

Sun Dog in the Nuremberg Chronicle.

Edward IV would use the battle as a neat piece of propaganda. A parhelion was seen on the eve of the battle, and Edward IV would say those three suns represented the three surviving sons of York (Edward, George, and Richard). It would symbolize the dawn of a new dynasty for England, but the collision of the three stars would allow Tudor's sun to rise.

#War of the roses#Owen Tudor#Jasper Tudor#Edward IV#Walter Deveureux#William Herbert#Humprhey Stafford#James Butler#parhelion#War of the Roses#long post#there is so much I wanted to talk on#local cities' involvment#Owen's weird execution#cycle of revenge clearly starting

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

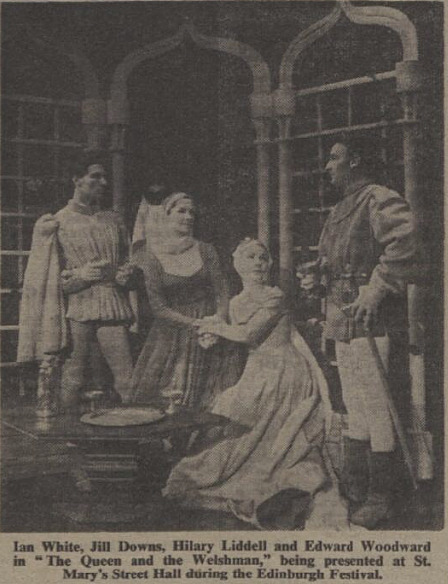

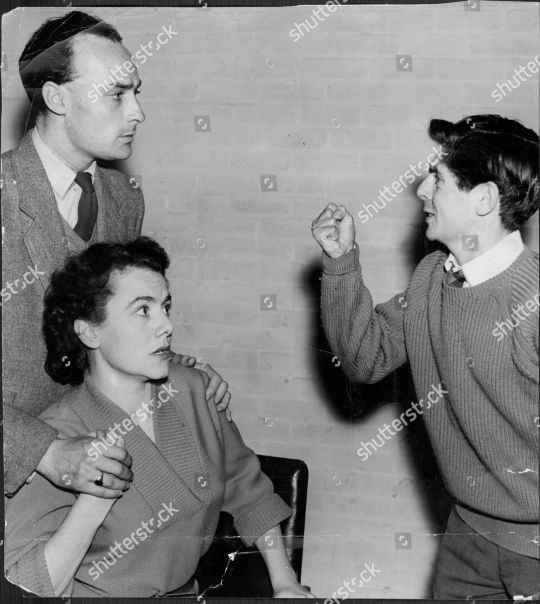

The Queen and the Welshman

I read Rosemary Anne Sisson’s novelisation of this earlier in the year & planned to investigate the theatre & TV versions as best as I could and see what I could put together for history fandom here on tumblr (because it seems to still be the only filmed version of the story of Catherine de Valois and Owen Tudor). Then I kept discovering slightly different versions (it was restaged! it went on tour! there was also a radio play version!), so it got a little more complicated, but anyhooo, here are my findings about the original theatre play that started it all!

It was Sisson’s first play and her big break, and something she seems to have returned to several times over the years, hence all the different versions, but the original was performed by the London Club Theatre Group in August 1957 for the Edinburgh Fringe Festival.

It was an odd success story, as the piece was distinctly old-fashioned for the era (”history in watercolour” as one of the critics put it), but it was a hit with Festival audiences - it fared better than most of the main Festival pieces that year - and as a result launched Rosemary Anne Sisson’s career. She was a Cambridge graduate, who had previously lectured for a US University, and had written the play after being inspired by Shakespeare’s history plays to find out what happened next to Catherine de Valois. She would go on to write for many period dramas, familiar to fandom here, including The Six Wives of Henry VIII, Elizabeth R, and The Shadow of the Tower.

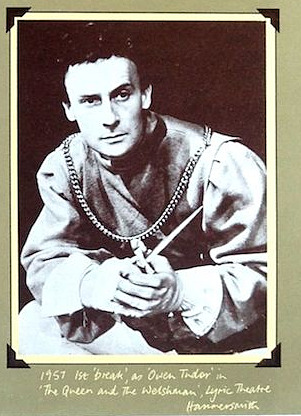

It also provided a break for its leading man - Owen Tudor was played by Edward Woodward, later to find fame as Callan and The Equalizer. (The cast seems to have been pretty good, and included a young Frank Finlay as the gaoler.)

It’s hard to find many details about the story of the play, but as it includes the same original characters as her later novelised version, it’s probably safe to assume that it follows a similar path - and reviews would seem to back up that impression. (The book starts in Henry V’s wars, where Owen meets fellow soldier Villiers, later to be an embittered enemy of his, and takes a French hostage, Rainault - a rather d’Artagnan-esque Gascon noble - who remains with him, due to his uncle finding it more convenient to let his ransom go unpaid, and who eventually inadvertently betrays Owen and Katherine, plus Katherine’s maid in waiting, Margaret (who has an affair with Rainault). John of Bedford and Humphrey of Gloucester are also two major roles, as the authorities who will come down hard on the pair if they uncover their romance (Bedford reluctantly, Gloucester happily).

Critics found the play well-written, with a sensitivity to the period, “quiet sympathy and no attempt to force.” They were also taken with the historical romance it was centred around, which most of its audience had been unaware of previously. It was low-key, or perhaps a tad too “underdramatic” and one critic noted one weak scene, but it was “fastidiously” produced, well-played, with no cod-historical nonsense, and drew in and pleased its audiences; attracting attention to a promising new female playwright (the only woman to have written a play for that year’s Festival) and an actor to watch in its Owen Tudor.

[From Age for Stock; image of Hilary Liddell as Katherine de Valois.]

Hilary Liddell, who played Queen Katherine, continued to work until at least 1979, and was married to actor Bernard Hepton. She and Edward Woodward (as part of the London Club Theatre Group responsible for the production) had also acted opposite each other previously in another of the Group’s productions, The Telescope.

[Image from Shutterstock, of Edward Woodward and Hilary Liddell in The Telescope.]

Critics concluded it was a “gracious and beautifully acted play” and praised Edward Woodward especially. The Evening News saw Owen’s farewell to Katherine towards the end of the play as the highlight of the evening:

"Very occasionally in the theatre an actor achieves by a single gesture an effect that wings straight to the heart of an audience. Mr Woodward did so last night when, as he held the Queen in his arms for the last time, he gave her a long, slow, silent smile in which affection and brave confidence perfectly blended. It was a magic moment".

[Image taken from a scan of his music album online labelled “1957 1st ‘break’ as ‘Owen Tudor’ in ‘The Queen and The Welshman’, Lyric Theatre Hammersmith”.]

The play then transferred to the Hammersmith Lyric Theatre that autumn (with the same cast) - and after that, it went on tour, was broadcast on radio, and made into at least two TV plays, and a novel, so had a long afterlife.

Rosemary Anne Sisson evidently never forgot this first version, or its leading man. When she turned the play into a novel twenty years later, she dedicated it to Edward Woodward:

“... who long ago helped me to create Owen Tudor, and since then to prove, in twenty years of friendship, that human love and trust exist and endure, and give some meaning to life.”

sources: frankfinlay.net (Evening News & The Scotsman clippings); The Stage, The Birmingham Daily Post, Birmingham Weekly Post (BNA); IMDB (Hilary Liddell info.)

#the queen and the welshman#rosemary anne sisson#catherine de valois#owen tudor#catherine de valois x owen tudor#edward woodward#hilary liddell#frank finlay#british newspaper archive#newspapers#1950s#theatre#edinburgh festival#period drama#tudors

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Who is interested in a Tudor Week 2023?

#henry vii#henry viii#edward vi#mary i#elizabeth I#owen tudor#catherine de'valois#edmund tudor#margaret beaufort#jasper tudor#catherine Woodville#elizabeth of york#arthur prince of wales#katherine of aragon#margaret queen of scotland#james iv of scotland#archibald douglas#henry Stuart#anne boleyn#jane seymour#anne of cleves#kathryn howard#catherine parr#mary queen of france#louis xiii#charles brandon#henry fitzroy

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

I've been thinking about how Katherine J. Lewis made this remark about Catherine de Valois and Isabeau of Bavaria

It is often claimed, without supporting evidence, that Isabeau was notoriously promiscuous, sometimes in discussions of Katherine. Strickland strongly implies this, calling Isabeau a “wicked woman” and a “degraded woman.” None of the scholarship on Katherine has explicitly drawn comparisons with her mother. Yet the two have received parallel treatment because the claim that Katherine was governed by her fleshly passions is taken at face value, without acknowledgement of the ideological implications of such obviously gendered criticism. (x)

Because while scholarship doesn't make this comparison*, there's Denise Giardina's Good King Harry and Brenda Honeyman's Good Duke Humphrey, where Catherine is presented as the young and beautiful version of her mother - conniving, evil, promiscuous. Since Giardina describes Isabeau in quite grotesque terms, there's also the implication that Catherine will one day become as monstrous in appearance as her mother, her exterior finally matching her interior.

However, the vast majority of novels about Catherine are sympathetic and view her 'notorious promiscuity' as an unfair and untrue slander that denies Catherine's status as a romantic heroine. These novels are frequently positioned as interventions, reclaiming Catherine's story as a tale of true love.

All the while, however, these novels stick to the traditional view of Isabeau of Bavaria. She is still "conniving, evil, promiscuous", fat and thus grotesque, and an abusive mother (this characterisation also pops up in novels about Isabelle de Valois too, though Isabelle's reputation is for tragedy, not romance or promiscuity). Typically, Isabeau terrorises Catherine as a child, coldly pimps her out once she's of an age to be married, and always derides her. Isabeau, often depicted as physically repulsive because of her obese, aged body, is also frequently jealous of Catherine for her youth and beauty. Giardina presents Isabeau on the other hand as being absolutely deluded about her appearance, imagining herself to be as beautiful and as sexually desirable as Catherine to the point where she offers herself sexually to her son-in-law upon hearing Henry V has quarrelled with her daughter. The scene makes clear her delusion by focusing on Henry's revulsion of her physical body which she has exposed to him a grotesque attempt at seduction.

While the purpose Isabeau serves in these narratives is both a matter of perceived "historical accuracy" (though some of these books were published after the historical reassessments of Isabeau by the likes of Tracy Adams and Rachel Gibbons) and to render Catherine as sympathetic as possible (setting the scene for her "rescue", usually by either Henry V or Owen Tudor, both serving as her romantic hero), it also feels like Isabeau is being used as to refute Catherine's reputation for "notorious promiscuity", presenting Isabeau as the most monstrous iteration of that so that the behaviour that earns Catherine that reputation is always considered a far lesser, if not wholly unproblematic, infraction.

In other words, Isabeau is the dark mirror of Catherine. Isabeau's sexual desires are about the physical, not the personal. She is insatiable and undiscerning, concerned only with her own gratification. She's at the mercies of her uncontrollable lust, bestial, and ultimately shallow. But Catherine? Catherine is driven by only pure emotions. She's in love, she's a romantic. Catherine doesn't fuck, she makes love. Catherine is the furtherest thing from a slut - a woman searching for true love. If you want to see a real slut, look at Isabeau. Not Catherine, a martyr to true love.

(Or Eleanor Cobham, who often serves as an antagonist to Catherine after Catherine is widowed - though, unlike Isabeau, Eleanor's scandalous sexuality is often suppressed. She coldly uses her sexuality to advance, unlike Isabeau, who is overcome by lust, or Catherine, who is in love. Eleanor, it could be argued, serves a dark mirror of Owen Tudor - the lover of lesser status who advances through the sexual conquest of a high status individual.)

None of these women's reputation for promiscuity is particularly warranted by modern standards. Isabeau's alleged adulteries come from Burgundian propaganda that aimed to undermine her and Louis, Duke of Orleans, or else developed in the years after the Treaty of Troyes to discredit Charles VII's claim to the throne. There is no evidence that this was anything more than slander. Catherine's reputation was borne from the fact she secretly remarried after Henry V's death to a man of lower status in defiance of the minority council. Eleanor's one known sexual relationship was with a man she later married and who probably should be considered estranged from his wife at the time. Eleanor could be considered as a homewrecker (though I would argue such a label ignores the political circumstances in which Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester's first marriage fell apart) but not necessarily promiscuous. But even if they were promiscuous, isn't time we moved on from demonising women for their sexuality?

* Well, John Ashdown-Hill calls Isabeau of Bavaria "something of an nymphomaniac" and says it's "possible that Catherine inherited her mother's strong sexuality", but I hardly count him as a scholar and you can't inherit sexuality, wtf.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

they’re a twenty but they're weirdly obsessed with people who died 500 years ago

#henryvii#tudor#reginald pole#anne boleyn#elizabeth i#cecily neville#margaret beaufort#owen tudor#jasper tudor

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

The tragedy of Edmund [Tudor]'s early death (he was still in his mid-twenties) and Jasper's arrival and energetic campaign focused attention in Wales on the Tudor family once again: as the first Welshmen to enter the English peerage, as representatives of the Lancastrian monarchy, and as blood relatives of King Henry VI. They were regarded as the most distinguished and loyal Welshmen of their generation. According to one Carmarthenshire poet of the day, Lewis Glyn Cothi, Edmund was "brother of King Henry, nephew of the Dauphin [King Charles VII of France] and son of Owen"—and in that order. When Owen Tudor was captured in battle by the Yorkists and executed in 1461, poets from all parts of Wales lamented his death as the father of the two young noblemen who were half-brothers of the king.

— R. A. Griffiths, "Henry Tudor: The Training of a king" | King and country: England and Wales in the fifteenth century

14 notes

·

View notes