#of philosophical dread and despair

Text

Time Travel Temeraire snippet

At first, Laurence assumes he's dead.

It's a natural conclusion. He remembers dying, after all.

He and Tenzing were at a function hosted by Wellesley. They were mostly there to support the dragons. Temeraire had long abandoned them to quarrel with Perscitia in the courtyard, with half a dozen ferals watching like it were a jousting match. Wellesley had laid out his grounds to allow room for dragons and men to mingle, but a good portion of the guests retreated inside to avoid the raised voices of the dragons.

Laurence wonders how Temeraire felt about that, later. About not seeing.

He was stabbed. He barely remembers it – just a quick pulse of pain in his chest, looking down. Red blooming over his coat.

Then he was on the floor. People screamed. Tenzing appeared, grappling with a tall and finely-dressed man; he used a dinner-knife to punch a hole in the stranger's throat, in a fantastic spray of blood, and dropped the body at once to kneel by Laurence's side.

He remembers Wellesley barking orders – bandages, water, a hot knife. Have to cauterize it, he'd shouted. Keep pressure -

But Tenzing never spoke. Just pressed down on Laurence's chest, over the wound, without particular panic. Laurence still remembers the grim resignation on his face; Tenzing knew what was coming. Laurence was glad to have him there when he died.

Then Laurence woke up.

The world sways in a familiar way, a rhythmic motion that Laurence registers on a soul-deep level. He's on a ship. But why? Where is Tenzing, Temeraire? Why would they put him on a ship?

“I think the fever's breaking,” says a voice. A naval doctor, disheveled and salt-stained, with long scars down his bared arms. “Oh, and awake too!”

“Well thank Christ,” says another man. One Laurence recognizes.

It's Captain Gerry Stuart – but he looks different, younger than the last time Laurence saw him, with smooth skin and dark curly hair.

Gerry died two years ago.

“Well, Lieutenant! You gave us a scare – how are you feeling?” Gerry asks.

“It's Admiral,” Laurence corrects rather than all the other things he does not dare ask. He hates the title foisted upon him; but it's at least more comprehensible than Lieutenant, and he clings to that rather than demand where did you come from.

Stuart throws back his head to cackle, though the concern doesn't leave his face. “Still perhaps a bit feverish, I think!”

“That might be the laudanum,” says the doctor, also amused. “Why don't you sleep a bit more, Lieutenant?”

“But where is Temeraire? Or Tenzing?”

“I can only assume you had some very vivid dreams,” Stuart chuckles. “You were babbling and babbling for Temeraire – isn't that a ship?”

“Perhaps the flagship of his fleet,” suggests the doctor, and Stuart laughs again. “Get some rest, Mr. Laurence. Holler if you need me.”

They both exit the sick-berth. Laurence stares blankly at the door.

What?

Laurence pats his chest. No wound. He looks down, startled by the pale thinness of his fingers, his youth-soft skin.

Well; not soft. Callouses cover his hands. But even these patterns are different – hard skin in places where he would hold a sword, or pulls ropes. His hands should be more wrinkled, yes; but these callouses faded years ago.

“Where am I?” he asks when the doctor returns. “And what is the year?”

“The year? 1793. You don't remember?”

1793. Laurence was 19 in 1793. A lieutenant for two years, on the Shorewise.

The doctor narrows his eyes. “What's my name, lad?”

Laurence swallows. His stomach churns; for the life of him he can't remember.

The doctor rushes off to retrieve the captain.

_____________________________

Laurence is diagnosed with brain fever, and partial amnesia. Gerry is horribly guilty about laughing, earlier; Laurence could not care less. He is given strict orders to stay on bed-rest for another week, in hope his strength will recover – and his mind.

Laurence doesn't think he'll have any issues working – he's forgotten many of the people around him, true, but he may never forget the way to run a ship. He's far more concerned with learning what happened.

From all appearances, it is indeed 1793. France is undergoing riots, and declared war against Britain in February. Temeraire has not hatched. Napoleon is probably a corporal or general himself, at this point. If he exists at all. God knows, perhaps Laurence is only mad.

But he doesn't feel mad. His memories are too vivid to be mere fever-dreams. A man cannot dream up twenty years of life!

But neither can a man go back to his youth, and live it all again.

I have a dragon, he thinks of saying. There is no war, because I captured Napoleon – an unknown man who makes himself emperor.

Mad. It sounds mad even to Laurence himself. But to imagine that Temeraire was a fever-ridden dream... Tenzing and Granby and China, all of it...

Laurence doesn't share his turmoil with anyone – not even with Gerry, who checks on him fretfully. After a week the doctor declares him well enough, physically. He's paired always with another lieutenant for the first few days on duty, and his shipmates watch him carefully for signs of permanent debilitation; but aside from a moment or two of hesitance, Laurence competently resumes his duties. The oversight lessens.

Laurence thinks about writing letters.

He thinks about writing to Tharkay's late father, who ought to still be alive, inquiring after his son. He thinks of writing to Prince Mianning, asking about the health of Lung Tien Qian. He thinks of writing to young Midshipman Granby, his unwed brother, his dead father...

Not all of them would reply. But he could ask questions. Could verify the truth of things. Unless this, instead, is the delusion.

Is he in 1793, imagining the future? Is he in the future, imagining the past? Or maybe he is already dead, and this is the reality of hell. He came here burning with fever, and now he burns with fear. Surely that is it's own form of torture.

Laurence is ironically given the task of tutoring the midshipman and lieutenant-hopefuls more than any other duty as the weeks pass; his crewmates still look askance, and the more eager of the midshipman become protective. Laurence remains perfectly capable of command; it is only that he can't help but be absent-minded, sometimes, staring at all the crewmen that pass him like they are nothing but moving paintings. Images of a world that no longer matters.

One evening the midshipmen drag him away to a meal with the other officers. It's a noisy crowd; Laurence would find the friendly bustle comforting in another life.

One of the senior officers, Lieutenant Moore, waves him down as Laurence enters. Evidently they used to be friends, given his notably concerned behavior of late. Laurence can't remember the man, and has a sneaking suspicion he died too soon to make a lasting impression.Moore jostles him when Laurence sits at the long table. “Will! Did you get any letters with the last batch?”

A patrolling gunboat brought a satchel of letters just this morning. “I did not,” Laurence says. He's grateful for the fact. He'd found a few pieces of correspondence in his quarters that he dutifully sent on; he cannot imagine writing a letter now, in this confused state.

“Then you've had no news! Robespierre has gone mad. Madder than before, I suppose.”

“Robespierre?” asks Laurence blankly.

Lieutenant Moore double-takes, as does everyone else around them. “Good lord, Will, please tell me you remember Robespierre?”

Right... Robespierre's reign was brief, but this is when he led France. Some of the things the papers published...

Well, at least Laurence has a well-worn excuse for his ignorance. He plays up his malady: “Yes. I think I recall he was... French?”

Groans of horror mixed with amusement echo around the table. “...Well you aren't wrong,” says Moore, looking pained. “He has styled himself the 'President' of their Assembly, which is some stupid way of being king; the French are all mad about removing and adding words right now. I don't know how they expect anyone to hold a conversation.”

“We should... probably educate Mr. Laurence about the war at some point,” some midshipman mutters. Laurence doesn't recall his name.

Moore sighs again. “Anyway. Robespierre is a tyrant, of course. But he's elected someone else to rule France! Barely more than a boy, too.”

Laurence frowns; he doesn't remember what Moore's talking about. “Why would he do that? Did they capture one of the Bourbons?” Declaring himself regent of a child-prince would at least make sense.

“Well, at least you remember them. No; it is some nobody, a young soldier. Not even French! I cannot fathom it.”

It feels like Laurence has been dunked in ice.

For a moment he can't respond. “What was his name? The soldier.”

“Napoleon Bonaparte. He has been chosen as head of their new heresy, the 'Cult of the Supreme Being,' they're calling it; and now de facto head of the government, too. Must be a priest? I don't know, nothing the French are doing makes sense. I expect his little group will be as short-lived as everything else about these riots.”

But Laurence doesn't think so. “...Excuse me; I'm feeling a bit poorly,” he says, rising on wavering legs.

“Yes, you look it! Go on, we'll tell you about the war later...”

Laurence flees.

#posting bc i have no idea where this is going or if I'll do anything with it#it's just a funny stupid idea#Laurence travelling in time: I have gone mad. I am plagued by visions. God is punishing me for my Sins. This is purgatory.#Why is this happening? What moral course of action can I take under these circumstances?#Napoleon travelling through time: No idea how this happened. Neat. Time to hijack a cult and rule my country even earlier.#basic concept is Laurence has an ongoing existential crisis about his Place In The Universe#but also he is determined to stop Napoleon#who is delighted and fascinated they BOTH came back and sort of indulgently lets him try#basically resulting in Laurence becoming Napoleon's unwilling advisor frantically trying to do damage control in between bouts#of philosophical dread and despair#“Poor Mr Laurence was loyal before the brain fever we swear”#meanwhile Laurence is in France just trying desperately to make Napoleon Stop#etc etc#Temeraire

98 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thoughts about the Banshees of Inisherin in no particular order because I'm insane and I spent at least a third of the screening with tears streaming down my face

Padraic starting out the film happy and one by one realising how few things he was relying on to stay that way, just the dreadful hit after hit as he loses his friend, his sister, his donkey and even the village idiot he couldn't get to leave him alone

Something which reminds me of the most painful moments of catcher in the rye or lord of the rings - having a protagonist who does not suffer stoically, does not repress his emotions until a breaking point, but laments and begs for help and reaches out again and again and is broken by the pain inflicted upon him and is not strong enough to survive through it

The most horrible sight to behold in our culture - a grown man crying

In general that whole scene. Padraic standing up to the shithole cop, getting assaulted, Colm wordlessly helping him up but refusing to comfort him once he broke down or stay with him past the crossing

Jenny being buried in padraic's blanket

The hooked stick.

The second confession scene containing both "kind of weird, but strictly speaking not a sin" and "you got me there"

"and what about the despair?" "It's back a bit" "but you're not going to do anything about it, are you?" "No, I'm not"

I wish I knew enough about Irish or English history to say something more about the civil war's significance to the story but I can at least say the faraway conflict gives an eerily absurd tone to Padraic and Colm's feud, like they are simultaneously squabbling over nothing and waging some great existential battle

Speaking of which I was absolutely astounded to see a genuine discussion about the meaning of life in like the first ten minutes of this film. Padraic represents my own belief that a life spent enjoying yourself and making others happy is well lived and valuable, while Colm is obsessed with being remembered and believes his life will only have been worthwhile if he does something remarkable, if he leaves something behind. I kind of wanted Padraic to ask him what it matters to him how someone will feel about him long after he's dead in the ground, but regardless this was a genuinely compelling and shockingly well laid out philosophical conflict

In general I'm stunned by how seamlessly and plainly the themes are interwoven with the story. It's hard to put into words exactly but it's some damn good scriptwriting

I called this movie a masterpiece of small scale tragedy on letterboxd and I fully stand by this. This microscopic in the grand scale of things drama - made to look even smaller by the fact that it's two grown men having it - is simultaneously shown very clearly to encompass padraic's entire world. The tiny island setting is used wonderfully to emphasise this

Speaking of which, I have a massive soft spot for stories where the location is a character unto itself, or in any case has a huge role to play. This is a perfect example of a story like that

And speaking of the tragedy genre, this is maybe the best example I have ever seen of comedy and tragedy/drama woven together completely seamlessly? I can't think of a single moment where the tone shift felt jarring or the mood felt inappropriate. One of the moments I remember most clearly as integrating humour with drama is when Siobhan sees the first finger and padraic's comically stunned reaction combines with her comically realistic one to create a genuine air of tragedy somehow. It's also a good example of the similarly seamless weaving together of naturalistic and stylised storytelling

Not only the horror of loving someone who hates you, but of having that person leverage your love for them in order to keep you away

In general, most heartbreaking film I think I've literally ever watched. 10/10 masterpiece probably will not watch again all the way through because it's too painful

547 notes

·

View notes

Text

Robespierre the elder must remember my firmness when, both working as judges in the episcopal hall of Arras, we condemned an assassin to death. He must remember, it seems to me, our philosophical and philanthropic debates, and even that it cost him much more than me to resolve to sign the sentence; however, I have more than him the soul exercised in sensitivity, in the love of humanity, I am a husband and father, he is not.

Censure républicaine, ou, Lettre d’A-B-J Guffroy, répresentant du peuple (1795), page 66.

The consideration my elder brother enjoyed in Arras, made him named a member of the criminal tribunal by the bishop of this city. This prelate had the nomination of these sorts of charges. He exercised the functions which had been confided in him with exemplary equity. But it always cost him to condemn. An assassin having one day come before the tribunal of which Maximilien was a member, against him the strongest penalty needed to be pronounced, and that was death. There was no way to modify this dreadful penalty; the charges were too damning. My elder brother returned home with despair in his heart, and took no food for two days. I know well that he is guilty, he always repeated, that he is a villain, but to put a man to death!!... This thought was insupportable to him; no longer wishing to have to fight between the voice of his conscience and the cry of his heart, he resigned from his functions as judge.

Mémoires de Charlotte Robespierre sur ses deux frères (1834) page 69. According to Herve Leuwers’ Robespierre (2014), Charlotte is wrong in that her brother resigned as a judge after this incident.

The two testimonies regarding Robespierre’s reluctance to the death penalty pre-revolution that we know of.

#robespierre#maximilien robespierre#charlotte robespierre#armand joseph guffroy#guffroy#french revolution

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Weilin has a very, very slim chance of becoming canon. [To my great and utter despair, but hey a ship don't have to be canon to be great] But if it were, here's how I, an inexperienced and completely biased amateur writer would go about it:

It's a couple of years after B4. I'd say like 4 or 5. Bolin and Opal have since amicably broken up [I never really cared for Bopal, I love both characters separately, but together they're about as interesting as mayo on white bread. ]

Remenants of the Earth Empire are stil slinking about the Earth Kingdom, causing trouble and a lot of Team Avatar and their other associates are having to step in.

Wei and Bolin get saddled with a mission together in which they have to travel around the Earth Kingdom for a couple weeks. [Because if Tolkien has taught me anything it's that gay road trips ALWAYS work]

Bolin is pretty ok with this arrangement. Sure, it's kinda awkward to travel the wilderness with your ex girlfiend's brother, but Wei is pretty cool, so he doesn't mind it that much.

Meanwhile, Wei has had a crush on Bolin for YEARS, but hasn't acted on it because Opal. This has evolved into a bit of resentment and he's sorta stressed about being in close proximity to Bolin for at least a month.

Bolin envies Wei for having a clearcut place in the world, while Bolin himself has yet to 'find himself'.

In return, Wei, who has been saddled with continuing Toph and Su's legacy since the moment him and Wing developed earthbending, envies Bolin's freedom to be whoever he chooses to be.

They butt heads often. Wei likes to poke and prod at Bolin and frustrate him. Bolin finds himself losing his cool more than ever, but also he finds that having little arguments with Wei helps him releive a lot of stress and tension.

This gay roadtrip would include:

Arguing about directions.

The car breaking down and them having to fix it but they both suck at mechanics.

Sleeping in a tiny tent together or under the stars and long, philosophical talks before falling asleep

Cooking together over a firepit. Bolin cooks, because Wei almost set the campsite on fire the first time he tried to. Wei does the dishes.

Bathing together in a creek and ogling the other. Also splash fights and playing in the water and suddenly, (oh my!) they're naked and really, really close.

Fighting side by side. Nothin gayer. Saving the other from danger.

So much mutual pining and sexual tension. And almost kisses and much more touching the other than necessary.

Pabu having to suffer through witnessing the tedious and odd mating rituals of human himbos. [Pabu, Opal and Wing are the biggest Weilin shippers, you can't change my mind.]

Making plans for the future together and kinda dreading the moment their trip is over and they're supposed to part.

#do you see the potential#do you see my vision#they could be incredible#weilin#wei x bolin#bolin x wei#legend of korra#avatar#avatar legend of korra#wei#wei beifong#bolin#might write this after im done with the constellations series

17 notes

·

View notes

Note

💫 ghirahim 🤭 please!!

Needed to take a mental break from BBN, so Ghirahim it is! cw for hints of depression

Song: Haze by Tessa Violet

I met a boy who never knew the taste of haze

To him the whole world is a stage

While I am fifty shades of beige

"There." Ghirahim let the twisted shards of Link's sword fall against the floorboards with twin clanks, dusting his hands off in short, sharp arcs to emphasize his exasperation. "With that nonsense out of the way, perhaps you are at last capable of civilized conversation?"

Link's eyes clung to Ghirahim's movements with weary dread as he resisted the urge to step back, though he spared a quick, rueful glance for the broken weapon at his feet. That was Gondo's finest work lying mangled on the ground between them—not that Link had expected much more from the blade considering that only the Master Sword itself had ever come close to piercing the demon's iron skin, but he'd hoped it might last a bit longer than that. His mind struggled to come up with some other makeshift weapon that could stop Ghirahim from doing… what, exactly?

Irritation vanishing in a quicksilver shift of emotions, Ghirahim seemed in no real hurry now to enlighten him. His gaze wandered across the tiny interior of Link’s messy home with a silent curiosity that on its own was enough to set each of his hairs on end, lips twisted in a coy grin that said he relished in Link's uncertainty. Speeches bordering on monologues were always the expectation where Ghirahim was concerned. Silence was not.

“You’re alive,” Link heard himself say as if through a haze, unable to summon even a hint of surprise to color the dull monotone of his voice. He’d halfway expected this, even though month after month had passed with no outward sign of the man who had once seemed nearly omnipresent.

“As are you,” Ghirahim observed, his silent scrutiny shifting instead to the dirty dishes stacked beside a half-eaten loaf of bread gone stale on the table. Thin lips curled. “Barely."

Link wondered with dry despair whether he should apologize for the mess, and surprised himself by nearly snorting at the thought. Laughter had felt beyond him these past few months, and this hardly seemed the right time to rediscover it.

To his relief, Ghirahim made no move to close the distance between them, though he still loomed head and shoulders over Link in such cramped quarters. Instead, he strode slowly through Link's home with the satisfied air of a performer who knew that his every breath held his audience captive. He paused gracefully, glanced over his shoulder deliberately. Strands of pale hair fluttered in the light breeze blowing in from the window, the gem at his ear scattering the final glint of sunset across his sharply chiseled cheek.

"That sword was new, you know," Link said. He could not have said why he felt so compelled to fill this particular silence when he usually preferred to embrace it, though he wished he was filling it better. Ghirahim’s huff of disdain agreed.

"New and poorly made," he retorted. "You deserve no less for such an ill-mannered attack. How does that little creed of yours go again?" His appraising eyes shifted to Link, dark and unfathomable. "'Strike not the unarmed foe'?"

Link frowned at the familiar words, the unfinished phrase completing itself in his mind. Strike not the unarmed foe, for an executioner is no knight: a line from the ancient vows of the Knights of Hylia.

"Is a sword ever unarmed?" he muttered, shrugging beneath a plain woolen tunic that felt abruptly heavier than the green one it had replaced. Pipit had that dusty old manuscript memorized front to back, of course, though Link admittedly only remembered scattered passages. Such lofty words had held little practical use back when Skyloft's greatest "foes" were the Keese that clustered in the island's caves.

"A question for the philosophers, I'm sure," Ghirahim said, his painted lips twitching in a mysterious grin. "What of this one? 'Let your aid flow out to those who ask, given freely as the light above.'"

"Is that you asking for help?" Link quipped, utterly unprepared for Ghirahim’s response.

"Perhaps."

For a moment, Link could only stare at him dumbstruck, wondering how a day that had started like so many others had gone so far awry. With somebody else, he might have marveled at the audacity of daring to ask for a favor after causing… well, everything. With Ghirahim, he only wondered where the trap was hiding.

Shaking his head, Link opted for the truth.

"I'm not a knight," he said shortly, and felt the intensity of Ghirahim’s attention increase tenfold.

"…Do tell."

"I…" Flushing slightly, Link set his jaw, forcing himself not to break that gaze. Urging himself to remember the severity of his situation. "What is there to tell? I was a knight, and now I'm not, so all that chivalry stuff doesn't really apply anymore, does it? You’re better off searching… somewhere else."

None of his kitchen knives would so much as scratch Ghirahim’s fingernails, of course. Maybe the frying pan could—

"I'm sure even you could summon up a few more words than that."

Link closed his eyes. That sharp surge of adrenaline he'd felt when he'd first discovered Ghirahim lounging across his chair was fading fast, leaving him sagging beneath the all-too-familiar haze of dull exhaustion. It wasn't that he didn't care that Ghirahim had returned, apparently unharmed and eager to meddle in his life once more. Of course he cared—cared for what it meant for Zelda, and the surface, and all the little plans and developments she'd poured her heart into as Link felt his own ability to do so shrivel away.

Like so much else these days, though, he felt it only dimly, with a sick edge of helplessness from the realization that he had no way of stopping any of it. This strange conversation, whatever its purpose, could only delay the inevitable. A frying pan would do nothing where the Master Sword itself had failed.

"If you're here for revenge, you might as well get it over with," Link sighed, feeling oddly relieved at his own lack of options. No control meant no responsibility. "Just… don’t draw it out. And leave Zelda out of this," he added fiercely, eyes flashing with real heat for the first time that day. If Ghirahim didn’t listen… well, maybe with her divine powers restored, Zelda could succeed in defeating the demon where Link never had. “Do you hear me?”

Studying him intently, Ghirahim ignored Link’s outburst.

“This might work out even better than I’d hoped,” he murmured instead, seemingly to himself, and Link squinted at him suspiciously. “I’d not expected to find our situations so similar.” Tossing his head so his hair fanned out behind him, he fixed Link with an oddly mesmerizing stare. It had been months since Link himself had felt that level of... vitality. “Fascinating though this turn of events might be, my need remains the same regardless of your knighthood. I never put much faith in chivalry anyway, even for one as honorable as yourself—so perhaps something more along the lines of a simple deal? You help me, and I refrain from tearing your budding civilization apart at the seams. I'll even throw the spirit maiden's life into the mix while we're at it, since it’s always meant so much to you. What do you say?"

And he held out a blackened hand between them.

Link glared at Ghirahim wearily, ignoring his hand for the moment. His proposal was really more coercion than deal, though Link doubted he'd be offered anything better.

"What do you want me to do for you?" he asked, and Ghirahim smiled.

"Irrelevant for now."

"Are there any alternatives?"

"Of course!" Ghirahim snapped his fingers, and a sinister black dagger appeared midair to hover in between them, aimed pointedly at Link’s chest. No alternatives. No options. No information, and nothing but Link’s cooperation standing in the way between Ghirahim and whatever havoc he would wreak on the surface otherwise.

Staring at the outstretched hand, knowing he had no choice but to take it—for now—Link was filled with the overpowering desire… to roll over and go to sleep.

He sighed deeply.

“No rest for the wicked, I guess,” he muttered, reaching out unwillingly.

“As they say,” Ghirahim agreed, and Link flinched as his grip snapped shut. Choice or no choice, he had the sinking thought that he was going to regret this.

#ghirahim#writing prompt#tldr: ghirahim shows up to recreate the 'damn bitch you live like this?' meme

83 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dean's Pending resolution

we're turning over all the cards.

youtube

Death and the goddess, something took hold of the darkness; the dark side of the moon. The ego's searching light through the darkness that might reveal the garden within. Let the sun shine on your face, or the road to the garden. The foggy side of the moon. A rugaru in any other language is the beast we need to take down with the faith in our arm. Heh. There-- let's go there. Something that's never happened before. [spnwin 1x1, 1x3] The Patient. Trauma. I hate him. I hate this. I hate me. I hate us. I'm good with who I am. I'm good with Who We Are. Our lives, they're ours. Even if you had the chance to do it over again, would you? [Akrida Radio] The Tower, The Shadow, the Empty

OMITTED - the glass cliff

youtube

2. This has never happened before. There, let's go there, Cas. You've arrived, then. The answer to life's greatest question. Nothing gold can stay. Something too precious to let go. What is your Whole World. The good and the bad. It was done for one thing. Cas, there's something I have to say. It's in just saying it. [spnwin 1x13] Chariot, Aeon. Holy Grail. Ouroboros. Swing on the Spiral. If you had the chance to do it over again, would you? We're running out of time. What is Gold. Nothing Gold can stay.

youtube

3. Burn my dread, face myself. What do you fear. I know what you hate. I know who you love. A Half-Djinn son of two creatures from different worlds tried to help, but there was already a monster in his head. The Patient. Death is the infinite vessel. The Universe/The Whole World; what is your whole world. The Shadow, the thing that rules the empty. Humanity. Just like his father the serpent. I love you. It's a Supernatural love story. Tick tock, we're running out of time. It's in just saying it, in just Being. A Bond that saves the Whole World.

Death is an infinite vessel. My heart. That's not who I am. [cd scratch]

We already saved the Whole World once, this is just our Encore.

I don't have many regrets but the few I do still haunt me; empty is just... regrets. I don't think he has any regrets. The Great Seal. The Tzimtzum. Graveyard dirt, Angel Blood, A Human Heart, My own still coursing blood, and my The Final Breath. Death is an infinite vessel. The One True Thing. In Order to be In The Garden-- He's watching us. The whole world.

VITRIOL is an acronym for Visita Interiora Terrae Rectificando Invenies Occultum Lapidem which translates into “Visit the interior of the earth, and by rectifying what you find there, you will discover the hidden stone (philosopher’s stone)”.

Or, loosely translated, in order to be in the occultum, the occultum/garden must be in you. Let in the light, let the sun shine on the moon and raise mind to soul. And soul to mind. In the garden. Where we belong, and always did. What is real. People, families. Chuck only wins if you let life's machinations beat you down. That's the babysteps. Now keep moving.

Let man know that he himself is deathless, for the cause of Death is Love, but Love is The All.

youtube

The Truth, you don't want the Truth, humans want a world surrounded by fog. They see only what they want to see [tv glitch]

Do you want to see the cruel reality? Sorry partner, this is it for me. The shadows. You disturb what humans want to see in the midnight channel. The clock is in the dark hour.

You suffer only because of your search for the The Truth. The final card. Human potential, infinite yet empty. The 0, the wild card, the Fool's Journey at its end. A Supernatural Love Story, about a Bond that Saves The Entire World.

In the light you will find the road. Here, at the end of the road, was it all worth it? If you could turn it all back, would you? Who are you? Who am I? Who are you meant to be? My name is Dean Winchester. Sam is my brother. Mary Winchester is my mom, and Cas is... ... is...

But first, we must find The Truth, rather than Despair--the two titles of 15x18, by some coinkidink huh.

youtube

If only they'd open their eyes and look ahead, they could see it. The Truth. I'll dispell the fog that covers our path. I believe in the Thousand Truths ahead of us. You have lifted the fog. Whether that leads to happiness rests upon your shoulders.

Yeah, leave it to us. Children of man. Well done.

The moment man devoured the fruit of knowledge of Good and Evil from the Serpent in the Garden, he sealed his fate. The absence of the soul isn't evil, just absence of Good, the One True thing. But one thing divides us. Something promised to all forms of life.

Entrusting his future to the cards, man clings to a dim hope. The arcana is the means by which all is revealed.

#the fool#the empress#wake up#the lie in the fog#the truth#there is a fog#embrace the truth#the world#i don't want to be alone anymore#a rugaru in any other language#still a beast sealing itself away#the fog#dean's song#we're turning over all the cards#we became a real family#we were a family#i didn't want to lose that#all of it was because of you#i hate him and i love him#i hate you and i love you#the winchesters codex#i am not alone#the universe#this is it#you're it#i'll take that win#big win#the grudge#saturn#1x3

33 notes

·

View notes

Note

2,14,28,29!!! Gimme dat celine lore

♡ ▹ ⁘ ❪ from this ask. ❫

2. How easy is it for your character to laugh?

she pretty much would laugh at anything, but one of the specifics is when their ideals clash, considering how apathetic and cynical céline is with humanity in general? and how she bases her opinion on strong facts and her lifestyle and the corporate greed she’d witnessed? it’s so much fun for her to watch good-natural people fall into the same cynical standpoint but even more fun to watch them continue being the way they are only for her to think that such heroes will be forgotten in several years, or even less.

she’s neutral evil and can be sadistic when it comes to watching ‘naive’ (in her eyes) lead people to either their end or to miracles. because the world still stands because of those heroes and she loves to watch the fight against the dark reality within human nature.

she feels weird satisfaction in watching heroic-to-be people act and go against her views and ideals. it’s fun for her. and it’s even more fun for her to watch if they succumb to despair and accept her views.

so yeah. céline’s evil and it’s another reason why she is like that.

14. What animal do they fear most?

i don’t believe there’s any animal she is afraid of, but she is utterly disgusted at reptiles for no particular reason…

28. Would they prefer a lie over an unpleasant truth?

no matter how dreadful it is, she prefers unpleasant truth, because she believes by the end of the day, lies with eventually come back to light.

29. Do they usually live up to their own ideals?

yes, even most people won’t agree with her — céline will throw philosophical arguments, logical arguments, and emotional arguments but it doesn’t mean that she is correct from the knowledge standpoint, or moral standpoint. her actions are not righteous in many, many situations. HOWEVER, she will be a provocateur who will see how she can be agreed with or disagreed with because it’s a sadistic side of her that wants people to lose their arguments with the sheer power that she pushes to see who’s worthy of her time.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

“In this blog post, I examine the anti-natalist theory of the Norwegian existentialist philosopher Peter Wessel Zapffe (1899–1990). According to Zapffe, human nature is riddled with an inherent, irresolvable conflict, the result of which is that human lives are filled with too much suffering for procreation to be morally permissible. In contrast to the God of the Old Testament, who instructs us to “be fruitful and multiply and fill the earth,” Zapffe instructs us, in his 1933 essay “The Last Messiah,” to “be infertile and let the earth be silent after ye.”

According to Peter Wessel Zapffe, human life is inescapably very bad, the central reason for which is that there is an irresolvable conflict inherent in our nature. What does this conflict consist of? On the one hand, Zapffe explains, we humans are biological beings that, due to the evolutionary forces that have shaped us, are constantly prompted to act in ways that promote our own survival and reproduction. Having become the dominant species on Earth, we have, in evolutionary terms, been successful. One of the central explanations of our success, Zapffe suggests, is our advanced cognitive capacities. While cheetahs gain an evolutionary advantage by being fast and bears by being strong, we humans gain an advantage by being smart: The human intellect enables us, among other things, to make tools and traps, to cook, to plan, to communicate effectively, and to adapt quickly to changing environments.

Zapffe suggests, however, that the human intellect comes with a very significant downside: It confronts us with our frailty, with the suffering and death that eventually awaits us, with the vastness of suffering on Earth, and with our own cosmic insignificance—and these insights, he writes, are apt to fill us with “world-angst and life-dread.” While “in the beast, suffering is self-confined, in man, it knocks holes into a fear of the world and a despair of life.” One reason for fear and despair is that we humans grasp not just what is right before us; due to our “creative imagination” and “inquisitive thought,” “graveyards wrung themselves before [our] gaze, the laments of sunken millennia wailed against [us] from the ghastly decaying shapes.” Another reason is that, as beings with an intellectual nature, we crave justification, and thus we are uniquely confronted with, and pained by, the meaninglessness and injustice of suffering. This, Zapffe holds, is a secular truth behind the myth that we humans have “eaten from the Tree of Knowledge and been expelled from Paradise.”

(…)

Zapffe concedes that his bleak outlook on life is likely to strike many as counterintuitive. This is so, he suggests, not because life is in fact tolerably good, but because we have developed elaborate strategies to prevent ourselves from seeing the horrors of life. He argues that such strategies, which he calls strategies of suppression, “proceed practically without interruption as long as we are awake and in action, and provide a background for social cohesion and what is popularly called a healthy and normal way of life.”

Echoing ideas from early psychoanalytic theory, Zapffe lists three central strategies of suppression: Isolation, anchoring, and distraction. Isolation is the process of isolating ourselves from unpleasant impressions by institutionalizing taboos and by ostracizing those who break them. This is most evident, he suggests, in how we protect children from the harsh realities of life: We tell them that, in the end, all will be fine and good, even though we know that, in the end, we will suffer and die, and, eventually, be forgotten. Anchoring is the process of entertaining fictions that tell us that we belong in a certain stable place, such as a family, a home, a church, a state, or a nation. “With the help of fictitious attitudes,” Zapffe writes, “humans are able to behave as if the outer or inner situation were different from what honest cognition tells us.” Finally, distraction is the process of filling our waking hours with tasks that distract us from existential dread. We keep our “attention within the critical limit by capturing it in a ceaseless bombardment of external input.”

Zapffe suggests that these mechanisms of suppression are needed to keep us from being paralyzed by fear. He maintains that one of the crucial functions of any culture is to provide effective suppression, and that many psychiatric disorders should be understood as results of a breakdown of the mechanisms of suppression.

In addition to isolation, anchoring, and distraction, Zapffe lists a fourth strategy: sublimation. Sublimation is the process whereby the tragedy of human life is given aesthetic value. The production and appreciation of art, Zapffe writes, is perhaps more properly called a mechanism of “transformation rather than repression.”

The reason is that while isolation, anchoring, and distraction work by trying to push suffering out of sight, sublimation confronts suffering head-on and seeks to transform suffering into beauty.

(…)

Although art can give us consolation, however, it cannot save us from suffering, the reason for which is that the source of suffering is too deep. We suffer, Zapffe suggests, because of our very nature as humans. Insofar as we use our intellect, which, as humans, we must do in order to sustain ourselves, we are bound to suffer. Insofar as we suppress our intellectual capacities, we reject our humanity and undermine the faculty that is most crucial to our mode of survival. Humanity, therefore, is confronted with the grim fundamental alternative of having to choose either death or suffering.

This is a gravely pessimistic view of the world.

How, then, does Zapffe get from this argument for pessimism to the conclusion that procreation is immoral? One premise on the path to this further conclusion is that life is not just filled with suffering, but is filled with so much suffering, and with so little happiness, that human lives tend not to be worth living. Another premise is that nothing short of extinction can bring human suffering to an end. To appreciate why he holds this premise, notice that in Zapffe’s philosophy, there is no hope that social reform can solve the problem of suffering. Although social reform might perhaps alleviate some of the suffering, he takes the core problem to lie, not in the way in which society is organized, but in human nature. The problem, we might say, lies not in the rules of the game but in the internal nature of the game pieces, and therefore, we cannot expect to be able to solve the problem by changing the rules of the game. The third and last premise, which is implicitly assumed rather than explicitly stated by Zapffe, is that it is immoral to create lives that one cannot reasonably expect to be worth living. If we accept all three of these premises, we have reached the anti-natalist conclusion that it is immoral to procreate.”

#zapffe#peter wessel zapffe#pessimism#antinatalism#suffering#morality#benatar#david benatar#schopenhauer#norway

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

June 26, 2023

Hm. It does, in fact, seem that I have expelled most of my terror into that last post. Now it kind of sits as a numb, low hum at the back of my mind instead of endless, tormented howling. Figuratively, of course. Anyway, the worry is still there, here, but just not as dreadfully centered.

My photo-friend, a former psychology major, once told me several years ago that catharsis was fake. That there was no such effect documented scientifically. That me journaling my negative emotions was only making them stronger, not somehow releasing them. Time and time again, I feel that I must be proving scientific literature wrong. But hey, that’s what a scientist does, right?

Now, I confess, I have, some winters, felt so dreadful that I listened to nothing but sad and angry music and isolated myself for months. That was not catharsis. That was wallowing. A depression somewhat aided by the shorter, colder days, in addition to personal and/or international despair.

Maybe, then, true catharsis is just for me. Some secret method of shedding the negative. When I’m not in a self-created environment of it, that is. If I’ve filled the box I’m in with negativity, shedding the negative from my skin won’t remove it from me, but add to the scenery.

Okay, enough with the philosophizing.

I finished watching Manifest with my dad, and I think the ending really, really delivered. I mean, the show was textbook Lost-esque: large ensemble cast of unique characters experiences a mystery-riddled ordeal together, somehow isolated from the rest of the world. There are clues and connections and buildups and twists and throwbacks and central characters and peripheral characters, all of whom we grow to know and care about. I think the main difference between the ending of Manifest and Lost is that the characters in Lost were suck on that stupid island (I mean it was an interesting island, but it was, by nature, isolated). Anything they did was stuck on that island. There was literally (pretty much) no impact on the outside world once they boarded that plane. They were all unknowingly fighting for a spot to be the protector of some special island that was only important, from my recollection, because Jacob said it was. Because it contained the Man In Black and kept him from destroying humanity like some sort of Pandora’s Box, or something. But, in its finale, Manifest demonstrated that the ensemble’s ordeal had a greater purpose that clearly and actually impacted themselves and their world. I think I teared up when Lost ended because those iconic final few shots with Jack and seeing the cast all together again and happy after seasons of trials was a little emotional. Sure there was some growth: Sun and Jin, most notably, Hurley... But the characters in Manifest all grew and exhibited their growth clearly in those final minutes. Sure, the show got a little wacky, just like Lost did, in mixing science and reasoning with magic and faith, but it was entertaining and interesting, with an ending that was heartwarming and, in my opinion, beautifully satisfactory (though my father did guess what would happen after they boarded the plane that final time, but he’s seen a lot more television than I have). Four seasons is a reasonable length (it’s the only show I’ve watched from the beginning of college to its end, actually), and I would recommend it to Lost-lovers.

[edit: one thing about Manifest though, and maybe it’s just that I was raised Christian and live in a Christian-dominant culture, but I found an interesting Christian-y bend to the show. And I’m not talking just about Angelina’s character background or the whole Romans(?) 8:28 thing near the beginning, but across the show and even in the finale, the idea of a sort of eternal, infinite punishment for finite crimes is a very Christian thing. Now, don’t get me wrong in the slightest, seeing unequivocally bad, unrepentant people suffer feels immensely satisfying. That’s because I’m human. It’s that instant reaction. But, after thinking about it just a little, it’s just kind of unfortunate, honestly. I think a less satisfying but, perhaps, more just ending would have been those bad people not being able to recall or in any way use the growth that could have occurred during those five years, unlike the protagonists. But to an audience, and as a piece of fiction, it might have seemed too lenient.]

Lost changed the game in television. But it’s hard to maintain a position as both the first and the best as time goes on.

Today I’m really, really thankful that I feel less worried.

1 note

·

View note

Text

I watch a lot of period shows and one of my favorite pastimes is to daydream about being a time traveler that can reveal the future to the characters. Who will ask what? What do I reveal? What do I keep hidden?

This was fun with anything pre-1920 as I can just stick to stuff within their lifetimes. They won’t ask questions relevant to today because nothing they know is within living memory.

Stranger Things is the first period show I’ve been into that is set within my lifetime and this little exercise has quickly become less of a fun “wait till you guys hear about disco!” fantasy and more of a “ok what CAN I tell them about the last 30 years that won’t fill them with with a cold, heavy feeling of dread and despair?” philosophical quandary.

#my brain won’t let me just enjoy things#I’m making soup and my brain is like what if you had to explain climate grief to argyle#what about that huh#wouldn’t that suck?#my life was easier when I was a downton abbey stan is all I’m saying#stranger things#time travel au

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Grief is just love with nowhere to go

starter for @ironifiicd

Grief is just love with nowhere to go.

Despite having read hundreds of books by enlightened philosophers and Masters of the Mystical Arts alike, what unexpectedly came to Quinn’s mind in that moment was a Doctor Who quote: painfully honest in its simplicity, it defined Quinn’s pain and didn’t offer any useless platitude.

Many people had offered Quinn their condolences, but they had all slid off of him like water off a rock - maybe because that for all that Ben had been loved by all, the Snap had caused so many victims no one could spare the young apprentice more than a brief moment of sorrow.

The human mind, for its own sake, had a limited capacity for pain before it became numb, and those times were testing everyone’s limits.

Thing was, Quinn had been beside Ben when it happened. They’d been sparring, with the apprentice outrageously sassing his master in an effort to distract Quinn long enough to land a hit. Ben had been commenting on Quinn’s failure at romance when he’d suddenly stopped and just -

He’d looked at Quinn, eyes wide like a spooked horse, a grimace of pain on his face, and then he’d started to dissolve into dust. Quinn had immediately jumped to his help, throwing a spell of protection, hoping to cut Ben off from whatever magic was affecting him, but to no avail: in the span of a few seconds his beloved apprentice was no more.

No warning, no noise, no nothing. Just the terrified look in Ben’s green eyes as he’d looked at Quinn, silently begging his master to save him.

Quinn’s first reaction had been rage. He’d stormed off, rallying their ranks against the invisible enemy, only to discover that the same had happened to other people in the London Sanctum - and when he’d ran to Kamar-Taj, he’d discovered that it happened universe-wide.

The first few days that same rage had fuelled Quinn as he joined his brothers and sisters into trying to find a solution. They’d pulled off the shelves pretty much all the books in their libraries, hoping to find some solution in the writing of their ancestors, both human and not, they’d reached out to similar Orders on other planets, but to no avail.

As the days went on and it dawned that they couldn’t do shit to bring their loved ones back, the anger dimmed and despair rose. Wong, their new Supreme Sorcerer, was helping the Avengers locate Thanos, so that they could take the Gauntlet and the Infinity Stones back and reverse the Snap, but Quinn had a sick feeling of dread even as he grasped at the straws of his rage.

(Rage was so much easier to handle than sorrow.)

All over the world people had funerals for the Snapped. The Order had a commemorative ceremony as well, where all the names of their lost ones had been inscribed in stone in Kamar-Taj, but even as Wong gave a speech about not losing hope, deep down Quinn had already known that there was none.

Then the Avengers really did find Thanos, and discovered that the Titan had destroyed the Stones.

And just like that, Ben was really gone forever.

Ever the stubborn man, Quinn had refused to crumble under the weight of his grief. He’d maintained his British stiff upper lip and he’d thrown himself into his duties as Master of the London Sanctorum. He’d kept the place running despite being half-staffed, training the remaining Sorcerers to fill the gaps in their ranks, supporting and helping his grieving brothers and sisters, offering to help Wong with whatever he needed. If he kept himself busy enough, eventually the sorrow would pass on its own, surely.

He couldn’t afford to be weak when his Order needed him to be strong.

Eventually, Wong had taken him up on his offer - but instead of asking him to protect Earth from some extraplanet or extraplanar enemy, the Supreme Sorcerer had asked Quinn to help with the rehabilitation of Tony Stark, the Ironman.

Apparently, the man had been stranded for way too damn long on a spaceship drifting through space and was now little more than a corpse with a pulse. Because that was a thing that could happen, apparently.

Quinn had jumped on the chance to distract himself and he’d accepted, of course. He was no doctor with a PhD like Stephen had been, but he was versed in the magical arts of healing body, soul and mind.

The first few times he’d met Tony Stark, the man had been almost comatose. Quinn had conferred with Stark’s personal doctor, thankfully an enlightened woman who’d easily accepted his magical help, and together they’d drafted a plan to get the man back to health.

When he’d finally been able to talk to his new patient, Quinn had been surprised to discover that pretty much everything he’d ever heard about Tony Stark was a lie. He wasn’t arrogant as much as he was very self-confident: he wasn’t a conceited asshole, he wasn’t mean to people around him. He was actually pretty funny, with a humour very in line with Quinn’s.

What had endeared him to the Sorcerer, though, had been how Stark - Tony, actually, they quickly switched to first-name basis - wore his guilt.

It was a feeling Quinn could relate to all too well.

And that day…

That day Quinn had forced himself to finally go into Ben’s room at the London Sanctorum to box his things.

The place had been left untouched. There had been a layer of dust on everything: the floor, the nightstands, the desk, the shelves, the books, the knick-knacks.

And under the dust of abandonment, the room felt jarringly lived-in. Ben’s dirty clothes were still in the hamper beside the door. His laptop was still charging. The bed was still unmade, sheets rumpled and his PJs lying around.

Ben was never coming back.

In the privacy of that empty room, Quinn had broken. He’d crumpled on the bed, crying his heart out, grief ravaging him until he was shaking and trembling and sobbing.

The claws of a Dauij demon had left some impressive scars on Quinn’s chest, but the physical pain of those wounds had nothing on the way his whole body hurt from Ben’s death.

Forcing himself to stand up and box everything Ben had owned was perhaps the single hardest thing Quinn had ever done in his life. Tears running down his cheeks, he pulled all the clothes out of the closet, the books off the shelves, the posters off the walls, the knick-knacks off the desk, and neatly put them in cardboard boxes.

He remembered the day Ben had come to the Order, a lost stray off London streets.

He remembered the first time Ben had managed a portal, his infectious excitement.

He remembered all the times they had tea in the middle of the night because neither could sleep, in quiet company and perfect harmony.

He remembered showing Ben countless planets and interdimensional planes, the wonder in the boy’s eyes and the way his smile made him shine.

And throughout it all, Quinn had never told Ben that he was like a son to him, that he loved him.

Grief is just love with nowhere to go.

When all the boxes had been taped close and put in the basement, Quinn had desperately needed to do something useful: he felt restless, his grief eating him from the inside, and he feared that if he were to try and train or practice magic in that state he'd hurt someone - probably himself.

So Quinn had opened a portal and had gone to visit his patient in the United States, even if there was no visit scheduled for that day. Tony could do with one more check-up, considering how he always tried to push his limits.

“Hello, Master St. John,” F.R.I.D.A.Y.’s voice greeted Quinn when he stepped out of the portal in the Avenger Compound’s lobby - it was basic Sorcerer etiquette not to portal directly into someone’s apartment. “I’m informing Mister Stark of your arrival. Please take the elevator on your right.”

“Thank you Friday.” A.I. or not, his ma had raised him with good manners.

Up the elevator he went.

4 notes

·

View notes

Link

0 notes

Text

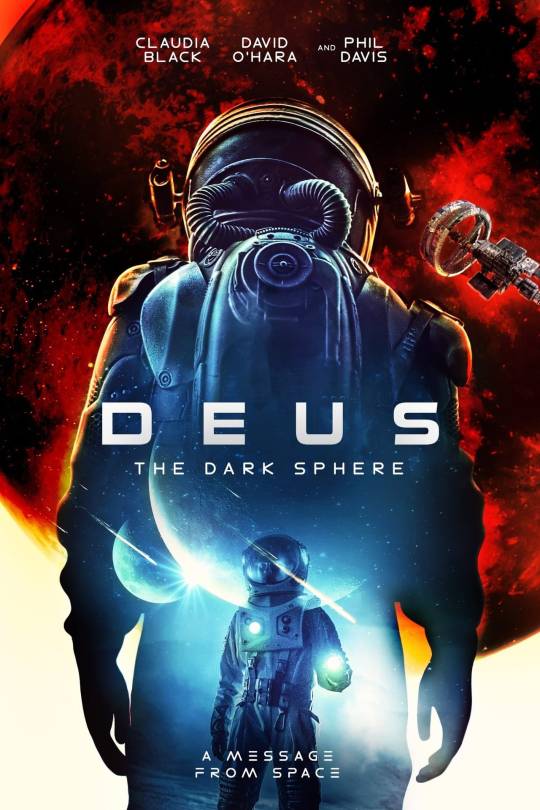

DEUS (2022)

Deus (2022): Space Junk or Cosmic Gem? ✨

So, what's the deal with Deus?

Title: Deus (duh!)

Genre: Sci-fi thriller (with a dash of existential despair)

Runtime: 1h 37m (Strap in, but don't get too comfy)

Country: UK (think rainy skies and accents thicker than the black hole at the movie's core)

Year: 2022 (Fresh outta the pandemic oven)

The Plot: A spaceship crew stumbles upon a mysterious black sphere whispering "God" in every language known to man (and probably some Martian dialects too). Naturally, things get weird.

Cinematography: Not gonna lie, some shots are stunning. Deep space vistas, sleek ship interiors, and that sphere... it's like a goth disco ball of existential dread.

Memorable Scene: There's a trippy sequence where the crew gets all mind-melted by the sphere. Think 2001: A Space Odyssey on a budget, but hey, points for originality!

Overall Review: Listen, Deus had potential. The premise screams "mind-blowing sci-fi epic," but it trips over its own philosophical beard. The story fizzles out faster than a spacewalk without a jetpack, and the acting, well, it's about as average as a lunar crater.

Personal Rating: 2/5 stars. It's not the worst space junk I've seen, but it could've been a supernova instead of a flickering flashlight.

This space flick had me hyped like a rocket taking off, promising whispers of mind-blowing cosmic mysteries. But then, just when I was strapped in and ready for blastoff, it fizzled out faster than a faulty thruster. It's like I wandered into a black hole of potential, only to get spat out feeling as lost as an astronaut with a busted compass.

Don't get me wrong, the visuals were stellar. Deep space vistas, sleek ship interiors - it was eye candy for any space junkie like me. And that sphere? Imagine a goth disco ball whispering existential dread - talk about intriguing! But sadly, the story itself was thinner than a napkin after a galactic food fight. It tossed around hints of mind-blowing revelations, then threw a tantrum and collapsed into a narrative black hole.

The acting? About as average as a lunar crater. Not bad, not amazing, just kinda... there. Like, I could tell they were trying, but those lines were drier than space dust. I swear, the ship's AI had more personality.

Bonus Trivia: Apparently, while filming the zero-gravity scenes, director Steve Stone got so motion sick he almost hurled lunch into the void. That's dedication, or maybe space food poisoning. ♀️

So, should you watch Deus? If you're a die-hard sci-fi fan down for a space mystery, sure, give it a whirl. But if you're expecting the next Interstellar, buckle up for disappointment. This space odyssey might leave you feeling more lost than an astronaut with a broken compass.

P.S. I'm secretly hoping for a Deus sequel where the crew gets possessed by sentient space furniture. Now that's a movie I'd pay good space credits to see!

#movie#sci fi#drama#deus 2022#DeusButMeh#CosmicDiscoBallOfDread#LostInTranslationInSpace#AstronautFoodWasDrier#MaybeTheAIWasTheRealStar#MemeMaterialToTheStars

0 notes

Text

get lost

Sometimes when you go looking for yourself you get more lost than you were before. And sometimes that’s a good thing.

“I feel lost.” We often utter these words with a sense of anxiety and existential dread. Especially if you’re in your 40’s and 50’s because apparently, we’re suppose to have life figured out by then.

But if you look at this with a different set of eyes, you might find that to be lost is to be surrounded by possibilities, a myriad of roads less travelled, each begging you to take a step. It’s as though you’re standing in Jorge Luis Borges' “Library of Babel,” surrounded by an infinite number of books containing every possible combination of letters. Choice is your blessing and your curse; every action, a foreshadowing of existential consequence.

Consider the irony. To look for yourself implies a separation - an “I” searching for another “I,” a seeker and a sought. Who’s the “who” doing the searching, charting the unknown terrains of the psyche, trying to place a “You Are Here” sticker on your soul? Philosophers like Descartes wrestled with this duality. “Cogito, ergo sum,” he asserted. I think, therefore I am. Yet, the more you think, the more the boundaries blur, the self becomes a construct, an abstract notion as elusive as time.

Getting lost can be beneficial. To be lost is to abandon the beaten path of societal expectations, religious doctrine, and cultural norms. Every wrong turn a lesson. Every detour reveals another layer of your being. I’ve lost count of how many times I’ve been lost. Stripped of the familiar, blown around like a seed in the wind, free to take root in new pursuits, unhindered by preconceived notions and habits of being.

To be lost is to invite psychological tension between comfort and growth. You can sense Kierkegaard’s ghost looming in the background warning you against the paralysis of too many choices, too much freedom. But you push into the dark anyway hoping to stumble upon undiscovered parts of yourself. Maybe you might unearth some hidden fears or awaken your dormant dreams, or discover your hidden potential.

Sometimes being lost is not an end, but a beginning of an evolution, a chance to redraw the borders of “self,” to rewrite the narrative of who you are and who you could be. Wander long enough and you might just find that to be lost is to be truly free - free to question, to explore, to become.

So let yourself get lost. In the chaos of the unknown, you might find beauty; in the confusion, you might find harmony; and in despair, you might find meaning. It’s the ultimate gamble in the casino of life, where the stakes are high, but the rewards are unparalleled - a deep understanding, a richer experience, and a life lived in the colour of curiosity and wonder, rather than in the mere black and white of conformity and comfort.

0 notes

Text

Bertrand Russell on the Salve for Our Modern Helplessness and Overwhelm

“To be a good human being is to have a kind of openness to the world, an ability to trust uncertain things beyond your own control,” philosopher Martha Nussbaum concluded in considering how to live with our human fragility. And yet in the face of overwhelming uncertainty, when the world seems to splinter and crumble in the palm of our civilisation’s hand, something deeper and more robust than blind trust is needed to keep us anchored to our own goodness—something pulsating with rational faith in the human spirit and a profound commitment to goodness.

That is what Bertrand Russell (May 18, 1872–February 2, 1970) explores in the out-of-print treasure New Hopes for a Changing World (public library), composed a year after he received the Nobel Prize, while humanity was still shaking off the dust and dread of its Second World War and already shuddering with the catastrophic nuclear threat of the Cold War.

Observing that his time, like ours, is marked by “a feeling of impotent perplexity” and “a deep division in our souls between the sane and the insane parts,” Russell considers the consequence such total world-overwhelm has on the human spirit:

“One of the painful things about our time is that those who feel certainty are stupid, and those with any imagination and understanding are filled with doubt and indecision.”

And yet, with his unfaltering reasoned optimism, he insists that there is an alternate view of our human destiny—one that vitalises rather than paralyses, based on “the completest understanding of the moods, the despairs, and the maddening doubts” that beset us; one that helps mitigate the worst of Western culture—“our restlessness, our militarism, our fanaticism, and our ruthless belief in mechanism”—and amplifies the best in it: “the spirit of free inquiry, the understanding of the conditions of general prosperity, and emancipation from superstition.” He examines the root of our modern perplexity, perhaps even more pronounced in our time than it was in his:

“Traditional systems of dogma and traditional codes of conduct have not the hold that they formerly had. Men and women are often in genuine doubt as to what is right and what is wrong, and even as to whether right and wrong are anything more than ancient superstitions. When they try to decide such questions for themselves they find them too difficult. They cannot discover any clear purpose that they ought to pursue or any clear principle by which they should be guided. Stable societies may have principles that, to the outsider, seem absurd. But so long as the societies remain stable their principles are subjectively adequate. That is to say they are accepted by almost everybody unquestioningly, and they make the rules of conduct as clear and precise as those of the minuet or the heroic couplet. Modern life, in the West, is not at all like a minuet or a heroic couplet. It is like free verse which only the poet can distinguish from prose.”

This torment, Russell argues, is simply the growing pains of our civilisation. When we reach maturity, we would attain a life “full of joy and vigour and mental health.” Building on his lifelong reckoning with the meaning of the good life and the nature of happiness, he writes:

“The good life, as I conceive it, is a happy life. I do not mean that if you are good you will be happy; I mean that if you are happy you will be good. Unhappiness is deeply implanted in the souls of most of us.

[…]

A way of life cannot be successful so long as it is a mere intellectual conviction. It must be deeply felt, deeply believed, dominant even in dreams.”

He offers a lucid and luminous prescription for attaining the good life, individually and as a society:

“What I should put in the place of an ethic in the old sense is encouragement and opportunity for all the impulses that are creative and expansive. I should do everything possible to liberate men from fear, not only conscious fears, but the old imprisoned primeval terrors that we brought with us out of the jungle. I should make it clear, not merely as an intellectual proposition, but as something that the heart spontaneously believes, that it is not by making others suffer that we shall achieve our own happiness, but that happiness and the means to happiness depend upon harmony with other men. When all this is not only understood but deeply felt, it will be easy to live in a way that brings happiness equally to ourselves and to others. If men could think and feel in this way, not only their personal problems, but all the problems of world politics, even the most abstruse and difficult, would melt away. Suddenly, as when the mist dissolves from a mountain top, the landscape would be visible and the way would be clear. It is only necessary to open the doors of our hearts and minds to let the imprisoned demons escape and the beauty of the world take possession.”

Complement New Hopes for a Changing World with the poetic scientist Lewis Thomas on how to live with ourselves and each other and Virginia Woolf on finding beauty in the uncertainty of time, space, and being, then revisit Russell on the four desires driving all human behaviour and how to grow old.

Source: Maria Popova, themarginalian.org (10th August 2023)

#quote#love#life#happiness#meaning#existential musings#all eternal things#love in a time of...#intelligence quotients#depth perception#understanding beyond thought#essential thinking#perspective matters#please be philosophical#great minds#this Is who we are#stands on its own#elisa english#elisaenglish

0 notes

Text

Running: A Haunting Discontent

Two weeks had passed since the grueling half-marathon race. And yet, as I stood before the digital scales, the news it displayed was nothing short of disheartening. The numbers revealed a sad truth: I had added another dreaded kilogram to my weight. Instead of the familiar 69-70 kg that had been my fixed weight for the past 3 months, I now weighed a disheartening 71 kg.

I once experienced the joy of a lighter weight after a fasting month, my body hovering at a much-desired 66-67 kg. Alas, those days felt like a distant memory, a far cry from my present predicament. Perhaps the burdens of life had taken their toll, my stress levels rising to unprecedented heights. It was during this time of self-doubt that I found myself clinging to a quote, attributed to a philosopher that never truly existed: "mando, ergo sum, I eat so I exist." As if seeking solace in the act of eating, I grappled with the notion that sustenance was my sole reassurance of existence in this world.

In a world where worries find solace in the depths of one's mind, I convince myself that a long, unwavering run shall suffice to diminish the weight that burdens me. But, as you well know, those who immerse themselves in athletic pursuits often fall victim to the sly trickery of their overrated workout regimes. They believe they have bestowed upon their bodies the utmost care, and that their relentless efforts are enough to satiate the needs of their physical beings. Alas, they remain far too certain that their workout routines alone shall shed the pounds and stabilize their weight, neglecting the most crucial factor: their dietary habits.

Should I care more? The only certainty that I can muster in this relentless battle against the haunting problem is by extending the distance of my weekly running regimen. Yet, lurking before me stands the most formidable of all challenges: shall I dare to venture further in curbing my eating habits? Which aspect of nourishment must I forsake: the hearty breakfast, the fulfilling lunch, or the comforting dinner that graces my evenings? And what of those unexpected brunches that I so cherish, scattered throughout the day like precious morsels of delight?

In the realm of my thoughts, I had once vowed solemnly that my fervent running would remain untainted by the allure of any frivolous goal, such as shedding unwanted weight. The truth is, the only motive I could deem acceptable for my tireless pursuit is to preserve my sanity - no other reason could be deemed worthy. To remain sane, in this convoluted reality, is to persist in living, resisting the temptation to hang myself in the midst of this wretched world, where the essence of existence is overrated.

Like a solitary pilgrim, I lace up my running shoes and embark on my daily pilgrimage, where the rhythmic pounding of my feet serves as a soothing mantra for my troubled mind. Each step offers a momentary escape from the shackles of this mundane existence, where chaos and uncertainty intertwine with our very souls.

In the enigma of life, the act of running becomes my sanctuary, a refuge where I can find fleeting solace. It is the fine line that separates the realms of sanity and despair, and I traverse it with unwavering determination, seeking that elusive state of equilibrium amidst the cacophony of existence.

So, I continue to run, not for the sake of vanishing pounds, but to preserve the fragile balance that keeps me afloat in this swirling sea of overrated reality. With every stride, I hold onto my sanity like a lifeline, navigating the currents of this disorienting world, striving to find my place within its intricacies and enigmas. For as long as I run, I remain tethered to the realm of the living, a glimmer of hope in the midst of this shitty, overrated world.

0 notes