#now THIS is an effortpost

Text

A few months ago, an article by Just Like Us about a survey of young UK adults regarding LGBT topics (and other articles on The Pink News and Gay Times UK that reported on that article) did the rounds on here.

The headline of the Gay Times article, written by Amy Ashenden (a cisgender butch lesbian and the interim CEO of Just Like Us, who hired the consultancy that conducted the survey) was "Lesbians being anti-trans is a lesbophobic trope"; of the results of the survey, she writes "I’m so glad that we finally have the research to demonstrate what most lesbians already knew: this narrative is completely false."

A lot of this initial reporting focused on the claims that "most anti-trans adults don’t know a trans person in real life" and "lesbians are the most supportive of trans people of any identity group, and it's a lesbophobic trope that they are anti-trans." These articles were written before the full report of the survey's data had been released.

The full report that these claims are based on is now out, for anyone who wants to take a closer look at the results for themselves. The pdf appears to be OCR readable but not image-described. The survey deals with many topics including being "out" and "feeling supported" at school and at work, but I'll just try to break down the evidence for the above-mentioned two claims.

How respondents were selected:

Just Like Us's report says that "Participants were drawn in partnership between Just Like Us and from Cibyl’s independent database of UK students and young adults" (p. 69). Cibyl offers "bespoke studies and focus groups," and says that "Using our Cibyl-ings student panel, we can source specific students to look at themes and topics important to you and ask the unique questions you want the answers to." This is rather vague.

Sample group and size:

3,695 young adults aged between 18 and 25. 86% cisgender and 12% transgender; 47% LGBT and 53% non-LGBT (used as a control group to compare LGBT responses to); 72% white; 79% students; 54% "female" (self-declared), 36% "male", 8% non-binary (pp. 69-70).

Support for the articles' central claims:

There is no full breakdown of the data resulting from the survey that would allow anyone else to do their own statistical analysis. Here's (what Just Like Us gives of) the data that the "most anti-trans people don't know a trans person in real life" claim is based on:

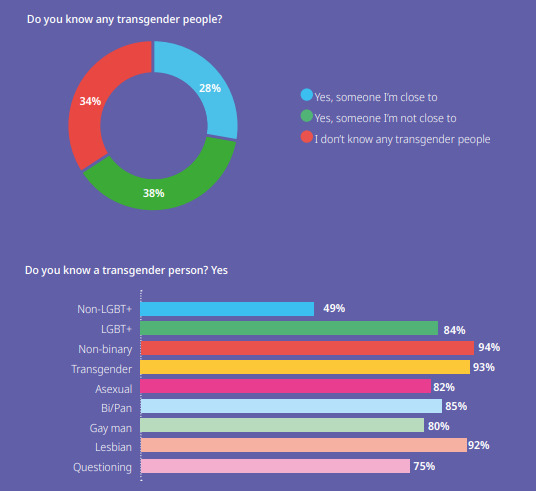

[ID: Headline reading "Attitudes towards transgender people. Question reading "How supportive are you of transgender people? Of people who "know a transgender person," 64% said "very supportive"; "supportive" 23%; "slightly supportive" 10%; "not supportive" 3%. Of those who "don't know a transgender person," 33% said "very supportive"; "supportive" 28%; "slightly supportive" 20%; "not supportive" 18%. Second question "Do you know any transgender people?" Result: 28% "Yes, someone I'm close to"; 38% "Yes, someone I'm not close to"; 34% "I don't know any transgender people." Further breakdown of the question "Do you know a transgender person?": 49% of "non-LGBT+" people said "yes"; 84% of LGBT+ people; 94% of non-binary people; 93% of transgender people; 82% of asexual people; 85% of bi/pan people; 80% of gay men; 92% of lesbians; 75% of questioning people. End ID]

The "do you know any transgender people" question is worded slightly differently each time—plus, the Just Like Us article and the report (p. 8) adduce the phrase "in real life" to "know a trans person," but this page doesn't—so I don't think we're getting the exact wording for that question that the survey respondents saw. The data for "how supportive are you of transgender people" isn't broken down according to whether the respondent said they were "close" or "not close" to the transgender person or people they knew; it also doesn't seem to be broken down into trans or nonbinary versus cisgender respondents.

"How supportive are you of transgender people?" was the only question dealing with this issue, and the responses "very supportive," "supportive," "slightly supportive," and "not supportive" were the only options available; there's nothing breaking down what "support" means in terms of policy (e.g. support versus non-support for consent-based clinics, national funding for transition care, non-discrimination laws, bathroom laws, &c. &c.). There is also no distinction made between "support" for trans women and trans men.

The claim "UK adults between the ages of 18 and 25 who answer 'not supportive' to the question 'How supportive are you of transgender people?' are several times more likely to also answer 'no' to the question 'do you know a transgender person' (or maybe 'do you know a transgender person in real life')" is supported, in my opinion. The sample size is large enough for that 3% to not be random noise.

The analysis in the Just Like Us article groups together "very supportive" and "supportive" when providing percentages of respondents of given identities who support trans people:

Of all LGBT+ identities, other than trans and non-binary people themselves, lesbian young adults were most likely to say they know a trans person (92%), and most likely to say they are “supportive” or “very supportive” of trans people (96%).

In comparison, 89% of LGBT+ people overall said they were “supportive” or “very supportive” of trans people, and just 69% of non-LGBT+ people said the same.

There is no full breakdown of how many people are "very supportive," "supportive," "slightly supportive" or "not supportive" of trans people by identity label. The relevant data is on p. 63 of the report:

"Looking at who was the most supportive of transgender people:

non-binary respondents were 97% supportive or very supportive with 1% of respondents indicating they were not supportive;

lesbian respondents were 95% supportive or very supportive [everywhere else in the report and in the reporting says 96%, so perhaps this is a typo] (3% were not supportive);

bi/pansexual respondents were 92% supportive or very supportive

(2% were not supportive).

Of respondents who were gay men, 82% were supportive or very supportive of transgender people, with 7% indicating they were not supportive.

Among non-LGBT+ respondents 69% were supportive of transgender people, with 12% indicating they were not supportive."

It's not clear to me how they dealt with e.g. lesbians who were also transgender. Pages 69-70 of the report go into the questions that people were asked to identify their identity label for the purposes of statistical analysis ("Is your gender identity the same as the one you were originally assigned at birth?"; and "What is your sexual orientation?"). The fact that these are separate questions (as they should be) tells me that there's overlap between groups throughout the study; any data that says e.g. "83% of lesbian respondents" is combining cis and trans lesbians, and any result that says "67% of trans people" is combining heterosexual and LGB trans people.

So, while narrowing the respondents down to just cisgender LGB people to compare their support for trans people would have been one way to analyse the data, I'm guessing they didn't do that (plus, there's the article's wording of "LGBT+ people overall"; it wouldn't make statistics-analytical sense to compare cis lesbians with all LGBT+ people, plus it would presumably make the higher support % of lesbians less stark, which seems like the opposite of what Ashenden wanted to do).

When the article says "other than trans and non-binary people themselves," they don't mean that they excluded trans and non-binary people from the percentages given; they mean "other than the number you get if you measure support for transgender people just from trans and non-binary people." We're not given the number that would result from doing this. The number we're given in the report for non-binary people is 97% supportive (this number is not included in the article); we are not given a number for just trans people, but we can probably assume it also approaches 100%.

This means that the 96% support presumably measures support from cis and trans lesbians; the 82% of "supportive" and "very supportive" gay men includes cis and trans men; &c.

There is a major statistics-analytical problem with acknowledging that trans and non-binary respondents have the highest rates of support for trans people, but then not controlling the results of this question for whether the respondent was cis or trans. If a higher percentage of lesbian respondents were trans than the percentage of gay men respondents that were trans, this would itself skew the numbers for lesbian support higher. There's no reason to suppose that this did happen, but there is not enough information given about the data that Just Like Us collected to rule it out. Again, at no point are we given information about overlap between LGB and trans groups or a breakdown of what that overlap looked like (how many trans respondents were heterosexual versus LGB, &c.).

As I mentioned above, some of the survey focused on whether respondents "felt supported" at home and at school. Some snippets on the results of these questions can be found on pages 45-49 of the report. "[M]ore than 1 in 4" LGBT+ respondents "felt unsupported" in school compared to "1 in 10" non-LGBT+ respondents; 37% of transgender respondents and 39% of nonbinary respondents said they felt unsupported in school. Despite the survey's focus on the outcomes of felt support, and despite all respondents being asked if they were "supportive" of transgender people, no question asked transgender respondents if they "felt supported" by cisgender LGB people.

Generalisability of claims:

The sampling of the data (which is drawn entirely from people in the UK aged 18-25, mostly students) also means that the claims are not generalisable to the entire UK population; you can't say the "majority of anti-trans adults don’t know a trans person in real life" (the headline of the Just Like Us article) or "Most anti-trans adults don’t actually know a trans person in real life" (the headline of the Pink News article), since the survey did not take a representative sample of all adults. You can't say "lesbians are not anti-trans" (the url of the Gay Times article), since the survey is not representative of all lesbians.

Funding sources:

The report was sponsored by Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Limited, a firm offering professional services (accounting, auditing, consulting, financial advisory, litigation consulting, and other services offered to businesses).

Cibyl, an independent research firm in the UK, "led on research design and delivery, then worked in partnership with Just Like Us to produce the report." They include the report ("Positive Futures") as an example of their work on their website. Their summary of the study focuses on the claim that "support in LGBT+ young adults’ teenage years" is necessary to the future development of their careers, and on what "employers and careers professionals can do to help LGBT+ young people feel safe and supported." This is the same kind of thing that Deloitte talks about when it comes to LGBT+ issues (namely, inclusion versus exclusion and support versus non-support in the workplace).

A video that Asheden produced with Mags Scott (partner at Deloitte) also focuses on how "support" for LGBT+ people "at home, in school, and in the workplace" leads to confidence in "career prospects" and ability to be onself "at work," and is necessary for LGBT+ people's mental wellbeing.

Just Like Us has an interest in promoting research that suggests that support for LGBT+ people in school will benefit them in their careers, since they sell training resources on forming LGBT+ groups, and talks with LGBT+ speakers, to schools. Just Like Us is a non-profit organisation.

Declaration of conflicts of interest and peer review:

This is an industry-sponsored study and not an academic one. There is no declaration of conflicts of interest required, and the study was not peer-reviewed.

Tl;dr:

Some breakdown of data was revealed in the report. The exact questions that respondents saw were not given. The data is not given with enough granularity to allow for anyone else to conduct statistical analysis based on it.

There is not enough evidence to say whether the study supports the claim that (cis?) lesbians are more supportive of trans people than any other identity group, since the survey was not clear what "support" means (someone may claim to support trans people as individuals while not supporting transition care, for example, due to some kind of "love the sinner, hate the sin" logic).

There is also a statistical problem with the support for this claim, since overlap between "transgender" and "cisgender" respondents is not controlled for. There is not enough data given in the report to allow anyone else to control for this factor. The results would hold if we assumed that similar percentages of e.g. lesbian, bisexual, and gay male respondents were transgender.

The results apply only to people in the UK aged 18-25 and cannot be generalised to all adults in the UK.

Summaries of this report given by the firms that funded and conducted it centre on the idea that "support" of LGBT+ people at home, at school, and in the workplace is necessary to allow them to thrive in the workplace. Just Like Us, who put out the report, sell LGBT+ talks and training to schools.

523 notes

·

View notes

Text

So, I didn't like the book "Abolish the Family" by Sophie Lewis very much

(Or, "wow, Corv, how did you manage to write over 5k words about a book that's got less than 100 pages?")

I read Abolish the Family: A Manifesto for Care and Liberation by Sophie Lewis and I.... well, to be gentle, I did not much care for it. And to be less gentle, I thought it was hot nonsense, and I kind of wanted to just put my thoughts down about it somewhere.

I picked up the book because I was curious about family abolition. I actually heard Sophie Lewis on a podcast ages ago, and I've seen some posts on Tumblr from people talking about family abolition, but I hadn't really heard it argued in full. I had some immediate concerns when I heard about! I mean, I agree that it's pretty fucked up to offload all the responsibility of caring for people who cannot care for themselves onto their families, which both enables abuse and also leaves people who don't have families shit out of luck. But what's the alternative? I assume it's not advocating for just letting all children run loose in the streets, but I don't know what it IS advocating for. If all children are to be raised collectively by the community, how will unique cultures and heritages be passed down? The way I see it, either we have diverse communities, and nobody gets to pass down history and culture and religious practices that are applicable to them but not to everyone (so either the white children in this community have as much claim to participating in the practices of, say, Native American tribes as any Native child, OR these practices are just dissolved entirely), or all these communities must be racially segregated. And isn't "abolishing families" what colonizing governments did to their native populations, when they forced their children to attend state-run residential schools? Are you just advocating that but for all children?

But these are concerns raised by someone who has only heard the name, really, and it's silly to get very mad trying to argue against what you imagine something to be without ever investigating what it actually is. That's not the kind of person I want to be! And surely someone who spends a lot of time thinking about and writing about this concept would have been able to anticipate my incredibly obvious and uninformed complaints about it. (In the same way that anyone advocating for police abolition MUST have an answer for the obvious "but then who will stop all the murderers?" question that people immediately respond with). I picked up this book in particular because, hey, it's a MANIFESTO! That must be the most distilled version of the idea, so surely it will answer my questions and tell me what I wanted to know!

I, uh. I was wrong.

Before I get started with a lot of my thoughts about the actual book, I do want to say that this is not really a refutation of the idea of family abolition, so much as a complaint that this one book is incredibly poorly argued. I have heard compelling arguments for family abolition, and I am, at the very least, sympathetic to the idea. I was honestly coming into this hoping to be convinced by it, so I think it's kind of shocking how unconvincing this book was!

OKAY with all my scenes set and my disclaimers made, let's get into the good stuff.

Abolish the Family is a very short book (122 pages, the last 30 pages of which are footnotes), and is broken up into 4 chapters. I'm just going to go chapter by chapter chronologically, although I could probably go in any order, as I don't feel like they really build on each other well.

1. But I Love My Family!

Lewis opens the book by arguing why families are bad: they are the means by which society privatizes care (as I said earlier!), they perpetuate capitalist hegemony, they foster environments under which abuse can flourish. I don't really have any refutations to these points, but I feel like me trying to summarize them here makes them come across as better argued than they are. Lewis makes a lot of assumptions about the readers immediate willingness to agree with her, in my opinion. She imagines we will try to argue that we love our families, which is, admittedly, one of my first arguments. "But loving one's family in spite of a 'hard childhood' is pretty typical of the would-be family abolitionist," Lewis insists, "She may, for instance, sense in her gut that she and her family members aren't good for each other, while also loving them."

I suppose that is true, but when I object to the idea by saying that I love my family, I mean that I enjoy being around them and I think my life is frequently better for them being in it. My mom is one of my best friends, and one of the only adults in my life who cared about and tried to accommodate my disabilities. It's weird to me that the only real response to this objection is for Lewis to go “sure, you love your family, but you can admit they're bad people!” I could admit that, but I don't think it's true! And if I did think that was true, you wouldn't really have to be arguing to convince me, would you? I would already be agreeing with you.

Personally, I always struggle a little with the idea that you can “love” someone but not “like” them, or that you can “like” being around someone but not really “love” them. A lot of that, of course, is that there is no consistent definition of what love means, and I'm autistic, so these things that seem very instinctual to others are occasionally a little inscrutable to me. Lewis attempts to define loving another person as ”[struggling] for their autonomy as well as their immersion in care, insofar such abundance is possible in a world choked by capital.“ Using this definition, she suggests that a mother who REALLY loved their children would not seek to have any particularly special relationship with their child on the basis of being their ”real“ mother, and that you, as a child (”assuming you grew up in a nuclear household“, which is a parenthetical that's doing a LOT of heavy lifting, if you ask me), surely noticed how lonely and isolated your mother was, being confined to the home, so you should all understand that family abolition is truly the more ”loving“ option, as opposed to perpetuating the family structure.

My problem with this argument is that... well, none of these things were true about my mom? She did not ”restrict the number of mothers (of any gender) to which [I] had access.“ When my father got remarried, she was delighted there would be more people in my life to love and care for me. And I most certainly did not sense her loneliness and isolation, because she was neither lonely nor isolated. And I very much did not grow up in a nuclear family, as my parents divorced when I was still in preschool. All of the things Lewis is suggesting as reasons for abolishing the family are things that were achieved for me within the family, and without any special effort on the part of anyone. So why should I support abolition, as opposed to, say, better social safety nets or something? If you were arguing that we need to eliminate mosquitoes to stop the spread of malaria, the fact that you can get vaccinated against malaria WITHOUT eliminating all mosquitoes kind of undercuts your argument, doesn't it? Even if I agree the problems you've pointed out are bad, you haven't convinced me that yours is the best solution.

I also found that the way that Lewis brings up the issue of abuse comes across as kind of... callous, I guess? It's brought up as more of a gotcha towards people who think that families aren't inherently evil, as opposed to a real concern that she actually has compassion towards and is seeking to solve. Lewis writes, "The family is where most of the rape happens on this earth, and most of the murder. No one is likelier to rob, bully, blackmail, manipulate, or hit you, or inflict unwanted touch, than family. Logically, announcing an intention to “treat you like family” ... ought to register as a horrible threat." And that's about all she has to say on the subject of abuse, beyond one name drop of Arthur Labinjo-Hughes, an English 6-year-old who was murdered by his parents during the COVID lockdowns (which, frankly, I found both a little inappropriate to mention, and not even a good example of the thing Lewis is complaining about. The abuse this child was experiencing at the hands of his father and his father's girlfriend was reported by both his grandmother and his uncle, but social services chose not to investigate. While he was abused and subsequently killed by his family, his family also attempted to save him. So it's a little weird to use this as an argument for family abolition and for having some sort of government/non-family body be in charge of the safety and well-being of children, if you ask me.) It just strikes me as weirdly uncaring, to bring up the subject of abuse only in response to a common piece of advertising copy. "Oh, Olive Garden says 'when you're here, you're family'? Well, sometimes families rape each other. Betcha didn't think about that!" Like, yeah, Sophie, I guess I didn't. You owned me, with facts and logic. Congrats.

2. Abolish Which Family?

I'm gonna be honest, it's very possible that this chapter went a little over my head. I like to think I'm decently smart and whatnot, but I really couldn't parse some of the points of this chapter.

Lewis states that her purpose in this chapter is to argue why families must be ABOLISHED, and not reformed or expanded, and why THE FAMILY needs to be abolished, and not just "the white family" or "the bourgeois family". She starts off by bringing up what she imagines some of the criticisms to family abolition might be: do you really want to talk about families the same way we talk about things like prisons or police? How can we talk about "abolishing the family" for colonized people, like Palestine, when the occupying genocidal power has already pre-abolished the indigenous family? Isn't this just asking queer people to surrender their hard-won family rights to hospital visitation? "As you can see, I’m semi-fluent—almost impassioned— when it comes to reeling out points against becoming a partisan of “family abolition.”" Lewis writes, "They are compelling, these counterarguments, even to me."

But she doesn't really refute any of these points? At least, not directly, which seems odd, given that she introduced the chapter by bringing them up. Most of this chapter is a lot of Lewis quoting other writers, who were writing about how Black motherhood is "as radical and revolutionary, as spiritual and transformative" (Jennifer Nash), and "Black mothering is queer" (Alexis Pauline Gumbs). I have no problems with Black writers exploring the ways in which the Black family is fundamentally different from the White family, or in finding power and beauty in that. But I do think it's a little odd for Lewis, a White woman writing about how families ought to be abolished, to spend so much of this book talking about how Black mothers are so important and wonderful? I thought families were bad? I think the point she's trying to make, both with this section and her later transition back into talking about how families should not be, is that Black families are already inherently aligned with family abolition, as they exist outside of the societal ideal of "the family", which is White. But it still strikes me as odd, to take a long diversion to deify the figure of a Black matriarch before going back to talking about how it's bad that women feel like they must be mothers. Do we want them to be mothers or don't we?

Anyway, if anyone else has read this book and can come up with a more coherent thesis for this chapter in particular, let me know. It's definitely the one I struggled with the most.

3. A Potted History of Family Abolitionism

In this chapter, Lewis lists every prominent writer that has written in support of family abolition (by her own metrics, as some of them did not identify themselves or their political pursuits to be attempting to abolish the family). This was honestly my favorite chapter of the book! A lot of the people she listed sounded very cool, and I will be reading more from some of them. I'm not going to talk about everyone Lewis mentions in this chapter, but I will go through a few of the ones I had the most to say about:

Charles Fourier

A French philosopher from the late 18th/early 19th century, he is the man who coined the word "feminism" and wrote about utopias (including insisting that, in his imagined utopia, the seas would lose their salinity and turn to lemonade. So I'm gonna put his ideas of utopias in the "maybe" pile). He imagined a world in which people lived in "phalanxes" of 1600 people, with universal basic income, covered walkways to protect from bad whether, a guaranteed sexual pleasure minimum, and communal kitchens, where all cooking and eating would be done by everyone. Lewis refers to some of these ideas as "unquestionable sensible" (particularly the removal of private kitchens in favor of communal cooking), and I, personally, DO question how sensible the idea is, actually! This is an incredibly common talking point amongst my fellow radical leftists of all stripes, to which I always want to respond with: have you ever known anyone with a severe allergy, or dietary restrictions, or an eating disorder, or or or or? I have ARFID, and there are very few things I can eat. Are we going to require the entire community change their diets to match mine, or, under this utopian society where I am not allowed access to a kitchen for only my food, am I simply not allowed to eat? Given how hostile people are to those with peanut allergies, even when it does not impact them in the slightest, I find it hard to believe that everyone would be happy never using peanuts in their cooking ever again when someone with an allergy joins the community. Maybe it makes me an unforgivable lib or something, but I don't believe capitalism is the sole reason behind man's unkindness to man, and I don't believe it will disappear after we build communism.

I also have some concerns about this supposed "guaranteed sexual pleasure minimum", but it doesn't seem like Lewis is going out of her way to defend that part, so I suppose I will have to let it slide in service of brevity. Which I know is funny to say, considering how long the rest of this post is. But, well, you decided to read it, so this is at least partially on you.

The Queer Indigenous and Maroon Nineteenth Century

This part's good! Lewis talks a lot about how, pre-colonization, Indigenous tribes did not organize property along the lines of the biological family, and the idea of "the family" was something that was imposed upon them by colonization. Taking property ownership out of the hands of the collective and putting it under the control of the heads of households - which is to say, men in general and husbands/fathers in specific - was a way for colonizing governments to dissolve the tribal identity. In this way, family abolition is actually a protection AGAINST colonialism, because it would be allowing people to return to ways of structuring communities that were not imposed by the colonizers.

Lewis goes on to talk about the similar experience of the people newly emancipated from chattel slavery in the U.S. Given the circumstances under which slaves were forced to live, the structure that we recognize as "the family" was not available to them, and once slavery was abolished, former slaves did not immediately organize themselves along family lines, and retained “diversity of relationship and family structures greater than their white contemporaries on farms or in factories" (Lewis quoting M.E. O'Brien). Lewis adds, "But the American state’s policing of the post-Reconstruction Black marital bed laid the basis for twentieth-century welfare officers’ “man-in-the-house” rule, which denied benefits to any mother caught “living” (even just for a couple of hours) with a member of the opposite sex. If you, a Black woman, had a “man in the house” of any kind, the law declared, then that man, not the state, ought to be the one paying your child support."

Overall, I thought this section was great! Very informative. Wish the whole book was like this.

Wages for Housework and the National Welfare Rights Organization

This is my favorite section in the whole book. While I don't think that Lewis herself adds much to the discussion, I do think that everything mentioned and quoted in this section is incredibly good and compelling. She first discusses the Wages for Housework movement in Italy which was, as the name would suggest, demanding financial compensation for the household labor traditionally expected of women. “They say it is love,“ Wages for Housework said, ”We say it is unwaged work.“ To quote Lewis:

”Pointedly, they did not deny that unwaged childcare, eldercare, housekeeping, sex, emotional labor, wifehood, might be a manifestation of love. Rather, the militants argued that “nothing so effectively stifles our lives as the transformation into work of the activities and relations that satisfy our desires.” Put differently: the fact that caring for a private home under capitalism often is an expression of loving desire, while at the same time being life-choking work, is precisely the problem. That the “they” of the dictum—bosses, husbands, dads—are not wrong about this illustrates the insidiousness of the violence care-workers encounter (and mete out) in the family-form. It’s the reason paid and unpaid domestics, and paid and unpaid mothers, still have to fight just to be seen as workers."

Meanwhile, in America, and frequently in collaboration with Wages for Housework, the late 1960's saw the formation of the National Welfare Rights Organization, which at its peak represented as many as one hundred thousand people, the majority of which were Black women, agitating for reforming America's welfare infrastructure. One of its founding members was Johnnie Tillmon, a self-described "middle-aged, poor, fat, Black woman on welfare," who said, in an article for Ms. magazine in 1972:

"For a lot of middle-class women in this country, Women’s Liberation is a matter of concern. For women on welfare, it’s a matter of survival. ... [Welfare] is the most prejudiced institution in this country, even more than marriage, which it tries to imitate…. A.F.D.C. (Aid to Families with Dependent Children) says if there is an “able-bodied” man around, then you can’t be on welfare. If the kids are going to eat, and the man can’t get a job, then he’s got to go. Welfare is like a super-sexist marriage. You trade in a man for the man. But you can’t divorce him if he treats you bad. He can divorce you, of course, cut you off anytime he wants. But in that case, he keeps the kids, not you. The man runs everything. In ordinary marriage, sex is supposed to be for your husband. On AFDC, you’re not supposed to have any sex at all. You give up control of your own body. It’s a condition of aid. You may even have to agree to get your tubes tied so you can never have more children just to avoid being cut off welfare."

At a time when most feminists were focusing on getting more women into the workplace, Tillmon and her comrades were demanding the freedom to NOT work, “the aspiration that women’s lives would no longer be dictated by husbands, employers, government bureaucrats, and clerks,” in the words of Wilson Sherwin and Frances Fox Piven.

Lewis argues that the work of the NWRO and Wages for Housework were works of family abolition "on the basis of their simultaneously (or combined) non-maternal and non-workerist accounts of what it is that a poor single mom needs and wants." I'm not really sure I agree, or I think that, were I to agree, then I once again have no idea what does and does not constitute "family abolition." If acknowledging that some single mothers would rather not work is an implicit endorsement of family abolition, that isn't all leftism inherently family abolitionist? I imagine that Lewis would argue that, yes, true leftism IS inextricable from family abolition, but she sure spends a good amount of this book talking about how many leftists DON'T support family abolition. If wanting universal basic income, for example, is wanting family abolition even if I don't say I'm advocating for family abolition, then how can you lament that I don't support family abolition? Am I overthinking this? Probably.

As I said, there were other sections in this chapter that I skipped over, because they were less interesting to me, or I had less to say about them: some arguments that Marx and Engels supported family abolition, some writings from a Soviet family abolitionist (who later, it seems, sacrificed a lot of her own ideals to support Stalin), dismay that Gay Liberation movements had been advocating for family abolition and the expanded rights of children but backed away from it to focus on surviving AIDS, and discussion of second-wave feminist Shulamith Firestone, whose utopian vision in her magnum opus, The Dialectic of Sex, involved mechanical uteruses in which all human fetuses would be gestated, resulting in no one even knowing who they were biologically related to any longer (and, by Lewis's own admission, segments of this book were pretty racist, and featured absolutely no mention of queerness. Ain't that just the way).

4. Comrades Against Kinship

We're almost done! In this chapter, Lewis finally answers the question I've had since I first heard the words "family abolition": but what does that look like? As you can imagine from my frustrations overall with this book, she does not have a coherent response. I would say she gives three answers to this question:

First, quoting Michèle Barrett and Mary McIntosh, she says, "Any critique of the family is usually greeted with, ‘but what would you put in its place?’ We hope that by now it will be clear that we would put nothing in the place of the family." Which is frustratingly dismissive, in my opinion. Obviously, there would be SOMETHING to replace the family. We're not very well going to just let all infants roam free in the streets!

Her second answer is, she doesn't know.

“It is very, very difficult,” wrote Linda Gordon, “to conceive of a society in which children do not belong to someone or ones. To make children the property of the state would be no improvement. Mass, state-run day care centers are not the answer.” Do we have answers? Do we know yet which kinds of relation are outside capitalist accumulation? Lou Cornum: “If the answer today is none, let us devise some by tomorrow.”

And her final, most concrete answer is: Camp Maroon, the months-long 2020 tent encampment in Philadelphia. Just copying from the book directly once again:

What was Camp Maroon? An occupation, complete with a kitchen, distribution center, medical tent, substance use supply store, and even a jerry-rigged standing shower—a militant village led by unhoused Philadelphians and working-class rebels like the indomitable, one-in-a-million Jennifer Bennetch (rest in power). The encampment was composed of hundreds of people willing to live together side by side, in tents, to struggle for free housing, migrant freedoms, the right to the city, and more. Even I, standing on the periphery, felt transformed. It was that summer that taught me this: all beings exploited by capital and by empire are basically homeless. All of us have been driven from the commons. Everywhere, humans have woven enclaves and cradles of possibility, relief, and reciprocity in the desert. But the thing that would make our houses home —in a new, true, common sense of the word—is a practice of planetary revolution.

It might seem a bit vertiginous to draw such huge conclusions from a localized camp-out in the middle of Pennsylvania’s capital city. But if you have experienced, even just for a few days, the alternate social world that brews in the utopian squatting of a city boulevard, you probably know. It’s trippy: people acquire a tiny taste of collective self-governance, of mutual protection and care, and suddenly, the list of demands, objectives, targets and desires becomes much longer and more ambitious than simply “affordable housing.” That’s why M. E. O’Brien thinks “the best starting point to abolish the family” is the protest kitchen: “Form self-organized, shared sleeping areas for safety. Set up cooperative childcare to support the full involvement of parents. Establish syringe exchanges and other harm reduction practices to welcome active drug users.” Expand from there, and never stop expanding.

There's also a lot of waffle about Aufhebung, a concept popularized by Hegal (which Lewis refers to as "the word abolition’s weighty original German form", even though the word "abolition" did not at all originate from Aufhebung, but instead from the Latin abolitionem. But now I'm nitpicking, I suppose), and a strange implication that actually, unhoused people in 2020 were better off than people who had to move back with their families, which I'm not sure really holds up to scrutiny overall. The final paragraphs of this alleged manifesto bring up a heretofore unmentioned point about how family abolition does NOT support the policy of separating families of "illegal aliens" at the border; family separation is actually another way of enforcing the importance of the family unit, as it uses the removal of family as a punishment and the (alleged) respect for the integrity of the family as a reward. Personally, I was always taught that the conclusion of a book or paper isn't really the right time to bring up new points, but I guess I'm just not as smart as Sophie Lewis.

Conclusion:

Let's see how many of my initial questions and concerns were addressed in this book!

If all children are to be raised collectively by the community, how will unique cultures and heritages be passed down? - Kind of answered, but not really. In the first chapter of the book, Lewis states "Like a microcosm of the nation-state, the family incubates chauvinism and competition. Like a factory with a billion branches, it manufacturers "individuals" with a cultural, ethnic, and binary gender identity; a class; and a racial consciousness. Like an infinitely renewable energy source, it performs free labor for the market. ... For all these reasons, the family functions as capitalism's base unit." (Emphasis mine) So, I guess, unique cultures and heritages won't be passed down, and she thinks that's good? She doesn't address this specifically, but I don't think you can put "imbues people with a cultural and ethnic identity" on a list between "incubating chauvinism" and "performing free labor for the market" and say that you weren't trying to imply that it's bad and the world will be better without it.

And isn't "abolishing families" what colonizing governments did to their native populations, when they forced their children to attend state-run residential schools? - Answered, genuinely! No, it's different, because it would be abolishing the idea of what a family is/ought to be that was imposed upon native populations, and would allow them to go back to doing whatever they want.

What's the alternative? - Answered, but the answer was "nothing. why would we abolish families if were were just gonna do families again?" so. Not really answered, if you ask me. And by reading this, you are implicitly asking me. There is no clear answer to what the world would look like if Lewis got her way, beyond, I guess, something like the tent city she visited in 2020. But that doesn't really answer my question of: in Lewis's ideal world, what happens to a baby after it's born? If I give birth to a baby, do I get to keep it? If I want to have children, do I get to have them at all, or is this work entirely offloaded to mechanical wombs (that I guess will have been invented by then)? Is it someone's entire job in this society to just gestate and birth children? Do I get to fuck freely and then give birth, but my baby is raised in some sort of state-run nursery or community-owned crèche? I don't know. I didn't know before I started this book, and, if anything, I somehow know even less now.

I looked at the GoodReads reviews for this book, and saw several people saying that they were generally fans of Lewis' work, but that this one was unusually bad, so I might try checking out her other book. If any family abolitionists read this post and have any recommendations, please let me know. I assume this can't possibly be the best articulation of the idea, because it is honestly borderline inept. For her self-described manifesto, Lewis sure doesn't ever make clear what she's hoping to manifest!

If this IS the best articulation of family abolition, then I think it's probably poorly thought out, at the very least. I don't want to veer into any naturalistic fallacies here, but it seems like this entire perspective hinges on the idea that humans are somehow not animals. That pregnancy and child-rearing are labor, and only labor, interchangeable with my data entry job. If a person gets pregnant, gives birth, and then feels a special bond with the child they birthed that they would like to maintain, it is a result of societal brainwashing at best and active selfishness at worst. A true leftist would surrender their baby to the nearest community government official, so it can be cared for by someone more capable, and then said leftist should get back to their life, same as it was before. Now, I've never had any children, but neither has Lewis, so we're both just talking about what we reckon and what we've heard. And from everything I've heard from friends and loved ones of mine who have borne children, this perspective is entirely out of touch with reality, or, at the very least, is an experience of pregnancy that is very much not universal. And, personally, I find it kind of disgusting.

So, uh, no. I guess this book didn't convince me to embrace family abolition. Which, again, is notable, because I went into it with the explicit purpose of being convinced to embrace family abolition. Ah, well. They can't all be winners.

#my writing#effortposting#family abolition#Sophie Lewis#ok now i have to throw this book away from me so i can stop saying more#if theres any point i make here that isnt clear please let me know i would be happy to clarify or rephrase#sometimes i fear that my leaps in logic dont always make sense to the outside#anyway. uh. ive been threatening this post for a while. so here it is.

26 notes

·

View notes

Note

Alec Baldwin, huh.

(in reference to my tags on this post)

I don't agree with the sentiment, I'm just SAYING if you write media analysis like this, you're a moron:

For those of you who can't watch videos, it's the famous speech Alec Baldwin gives in the cinematic masterpiece Glengarry Glenn Ross. Baldwin's character -- whom you assume is the villain -- addresses a room full of dudes and tears them a new asshole

As smarter people have pointed out, the genius of that speech is that half of the people who watch it think that the point of the scene is "Wow, what must it be like to have such an asshole boss?" and the other half think, "Fuck yes, let's go out and sell some goddamned real estate!"

Or, as the Last Psychiatrist blog put it: "If you were in that room, some of you would understand this as a work, but feed off the energy of the message anyway, 'this guy is awesome!'; while some of you would take it personally, this guy is a jerk, you have no right to talk to me like that, or -- the standard maneuver when narcissism is confronted with a greater power -- quietly seethe and fantasize about finding information that will out him as a hypocrite.

Here are some quick indicators you can disregard someone's media opinions, whether you've seen whatever they're describing or not

They tell YOU what you'll assume about a character

They tell YOU what the "correct" read of a character is

They think there's two primary reads of the story and they flatten down to "my interpretation is smart and says something good about myself, all other interpretations are superficial and evidence of a pathetic lack of self-awareness"

They talk about award-winning, complex media like a storybook for small children. This guy is actually the villain! This guy is actually the hero!

They're so so so certain that they know exactly how everyone else interpreted the movie

Take American Psycho - when I finally watched it, I *did* find takes I disagreed with, and I *did* find takes that I felt misunderstood certain characters. But very few, if any, disagreements were due to the other person's perception of characters as purely heroic or otherwise. I found takes that I didn't object to exactly, but came from viewpoints I felt too ignorant to fully grasp or comment on. I found gaps in my own understanding, gaps I don't think I'm capable of filling (I don't get music, sorry).

It wasn't 50% dudebros who wished they were/wanted to suck off Patrick Bateman and 50% wise women smartly explaining why the racist misogynist is in fact a bad person. The most annoying, shallowest takes I've found I'm most hostile to are those "you aren't patrick bateman, you don't even wash your face/teen girls with a skincare routine understand American psycho more than any dudebro could" memes. The take with actual effort that I bristled at the most was an essay that seemed oblivious to how severe homophobia was in the 80s.

I haven't watched Glen Glennie Ross, I'm just saying this guy's read of it lends me to believe he's not a reliable source.

#now granted _I_ talk a lot about villains and assumptions but I'm only reading low-grade comics for teens#niche effortposts#american psycho

48 notes

·

View notes

Note

Ellie and Ysayle

DANG got hit right out of the gate with an NPC Ellie definitely has thoughts and feelings about, but I haven't actually thought about it yet dshfaklfjgs so this is all off the cuff!!

(and ofc it got long so...)

---------------

Ellie did not easily settle into the role of Warrior of Light; it felt ill-fitting and sometimes wrong, especially as she grew in notoriety and renown and started having people worship the ground she walked on for supposedly worshipping and being "blessed" by Hydaelyn. Never did she feel she could bring it up with her friends, not even her co-Warriors of Light Lily and Mia.

But an enemy... She knew the truth, she thought, she knew primals are an existential threat and cannot be suffered to live... but the Lady Iceheart was the first person who was able to put words to the unease roiling within her. It's likely "we who gods and men have forsaken shall be the instruments of our own deliverance!" dominated her thoughts until the bloody banquet pushed them out. How much agency does she truly have as a Warrior of Light -- is she bound to Hydaelyn's will? To the Scions'? She (and Mia and Lily) are the ones here in this amphitheatre fighting for...what, if not their own ideals? The Empire was such an easier villain to abhor in contrast.

When Alphinaud suggested appealing to Iceheart, she leapt at the chance because it felt like something within her own power -- her own will. And as she grew to know Ysayle Dangoulain proper, she found common ground in the distrust of those who consider themselves superior, who believe they have the right to use their powers -- their blessings, their Echoes -- as their own political pawns.

Mia had made overtures since the bloody banquet, but Ysayle was the first person Ellie felt truly understood her. Especially since she couldn't well speak of the hypocrisy of harming innocents in her quest for justice, because Ellie had very much made the same mistakes battling the primals in Alliance lands, if not on so grand a scale.

And as a person in her own right... she admired how strong Ysayle and her convictions were, to the point she found herself doubting if her own could stand up (but she found great pleasure in discovering that armor could be chipped by Petting Fluffy Moogle). The more they spent time together on the journey to Hraesvelgr, the more moments of softness, vulnerability, and warmth she found in a woman supposedly made of ice, and the more she grew to admire her. She found herself drawn to Ysayle almost as she had been with Minfilia, for a similarly earnest heart below a masking exterior -- she might very well have fallen in love if she wasn't still so raw with grief from the bloody banquet.

It might be better that she hadn't, because the very same grief and pain she suffered from losing Minfilia struck her regardless as she witnessed Shiva's form dissipating and a lone blue-robed Elezen plummeting to her doom through the clouds, and she found herself cursing whatever higher powers steer their fates even more. It also instills an even deeper distrust of Hydaelyn -- what exactly is She demanding of Her servants, of people with warm hearts like Minfilia and Ysayle? Of people like her? That sort of distrust isn't well and truly dispersed until she meets Venat in Elpis -- and I think (way more than I used to) Ysayle's memory lingers in Ellie's mind the entire time.

...that was way more than I expected holy shit lol, thanks for the ask @ubejamjar!!

#ffxiv#final fantasy xiv#ask games#my ocs: ellie wiltarwyn#ysayle dangoulain#ellie's effortposts#i think that's my tag now for these kinds of lore/character-building posts lol#and it sure was effort because i went and rewatched the cutscenes to remind myself (and take those shots) sghsdalfjk#and having written all that now I. literally cannot believe I haven't made Ysayle a bigger part of Ellie's story.#they have so much more in common than I realized!!#brb I have *so much* rewriting to do @.@;#oc loreposting

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

I finished worm and I have no idea what to do with myself anymore

#i spent like an hour talking to Robin about it so I don’t have the brain juice for an effortpost right now but rest assured they’re incoming#op#wormblr

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Though none of the other Orokin we've seen so far seem to have defined pupils either, the way Ballas' eyes are rendered in this specific piece of art for the Zariman portraiture reminds me of cataracts. Some related information to follow (though this is just me musing on a headcanon, not something I think is definitively true).

In The Sacrifice, the Vitruvians are how we learn more about Excalibur Umbra's origins and the origins of all Warframes. They're spoken aloud, which makes me think that Ballas' eyes were already going, and he dictated most of his "writings." (the Prime trailers are in video form, so of course they're spoken aloud, but I believe they count for this also)

Additionally, during the Sacrifice: When Margulis, who was blind as mentioned by The Second Dream (during the third dialogue choice after waking up, you can say "she was brave" and your Operator will mention she was "blinded and sick by her work with us") said "Love looks not with the eyes, but with the mind," perhaps she was trying to reach out through this commonality.

Also, Ballas was an executioner, one who employed the Jade Light. Cataracts can be caused by radiation, also specifically by UVB, which is part of why one covers their skin and eyes while welding. The Jade Light is described as a "flash" and "blinding" by the Crewman Synthesis imprint, would it be so much of a stretch to believe that it was damaging to eyesight on prolonged or repeated exposure?

#Sidereal Sacramentary#2#3#4#5#ballas#Not maintagging this the innocents of the wf tag do not need my effortposting about Balls Ass#Also now that I have a personal tag (woo) i can post things and find them again

12 notes

·

View notes

Note

CONGRATS ON THE QUITTING!!!!! 🥳✨🎉

thanks, beloved mutual!!!!! ✨

i am incredibly McTired and i only quit after months of waiting to talk to the eeoc and exhausting every available option to work things out internally or externally, in the hopes that the poor schmuck after me might have an easier time. and in the end i didn't manage to permanently change anything, since i doubt my hr complaints will go anywhere. and i am worn out. but hey! now i have a new life experience! and am not being discriminated against!

so yea. tired, gonna be processing a lot, but it is definitely a celebratory time. have had some delicious food and dessert and have a nice few days of Relaxation Time planned and i much appreciate you celebrating with me :)

#The Dog Problem#now that the federal government is not paying for my lawyer and the eeoc has declined to take my case (long story)#(will consider making an effortpost about it at some point)#i can actually go back through my fragile madman era and mood tags and label 'em with the first ba degree job tag#and complain!#because damn this was a lot.#anyways. yes. I QUIT MY JOB :DDDDD#thanks again for the confetti babe <3

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

worm shipping chart is giving me new horrible ways to poke my favourite blorbos with a stick

#i'm wrong but i have to poke them to find out#will answer asks and make effortposts later just had to get this down Right Now. it's doing things to my brain...

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

favorite songs last week

#1 - i had this list a little different before sunday night, but then i saw jhariah live again (i saw them for the first time during their i believe first tour in '21), and this song live is really special - to them, i presume, given the fanfare they give it, but also to me. it's not quite the same as when it was performed for a group of people so small it couldn't be reasonably called a crowd, but it still means a lot to me. i didn't want to put two songs from the same concert on here, so this beat out reverse (also fantastic to hear live) because of the personal significance. these are both some of his older works, and he expresses that he thinks he could do way better with them if they made them today instead of when they were in high school, but i don't know, i think they're really good as is. i acknowledge that i have nostalgia goggles on. i've just been into them since before any of their newer shit that they like better came out, and s/r in particular helped get me through a really rough patch in late '21 after the show.

#2 - g-d, danny brown is such a good artist. he had, apparently, been adjacent to my music taste for years and has featured on a number of songs that i loved in high school and really early adulthood without realizing it, but i didn't really start listening to him until i saw him live during the scaring the hoes tour last year (i'd liked him on that album a lot, but i'd listened to it for peggy). i now... have my issues with peggy, but the two of them put on what was almost certainly the best show i've ever been to. he's a captivating performer, and i always love live music more, but even without that, he's got a fantastic backlog of music & is basically always putting out cool and creative shit. i love the sound of this song. it's much softer in sound than a lot of music i tend to seek out these days, but i do need a break from all the shit i put in my ears that's designed to be abrasive now and then. i think it's great, the production is great, q-tip is obviously a powerhouse, and danny's always fantastic. this one is mostly my track of his of the week because i hadn't paid attention to it before. i'm so put out that he's not coming back to my area for the quaranta tour.

#3 - i'm a huge clipping.head. everyone knows this. i'll like to love anything they put out. this is no exception. it's probably my most played track of the week (and the week before last). i played it enough in the first day after i heard it that i immediately forgot what the original sounds like. i've relistened to it, and i prefer this version. the b-side midnight is also a pretty cool little project. though not as earwormy as the first part, lol.

#4 - this one's another cover. i like covers, okay? i like when they sound different than the original. i'm very taken with this one. spotify recommended black alley to me recently. i don't remember why and i don't know what the context of it was, but this was the first song of theirs i heard and i really enjoy it. i'll be going through their original music shortly.

#5 - paramore is good. i like paramore.

#reverse live made me feel a little sick (in a good way). felt.#anyway. hi. i am not going to keep myself to a schedule of doing this weekly. lol. we all saw how quickly i threw away the sotd thing. but#i like to share music. so i might throw together little lists of my favorites of what i'm listening to right now on occasion.#effortposting#personal#music#sotd#Spotify

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Okay but I think I know why we've all got beckory brainworms these days. And yes, this'll be an effort post over something completely silly its not like I'm supposed to go to sleep before work tomorrow lmao.

Okay. As many people have pointed out, Tony's descriptions of his friends kinda sounds like he's crushing on them. Calling Ellis the best looking of the three amigos. And commenting that some girls at their school had called Gregory cute. I remember periodically seeing jokes about this, both on Tumblr and Twitter. Eslecially when Bobbiedots conclusion first released. Because... it is a little suspect. As Puhpandas has pointed out, this is kinda just down to poor writing- the authors of the pizzaplex books (and presumed frights. Though I've read none of those and can't say for sure.) Just. Aren't that good at organically weaving in character descriptions. So a lot of the protags (considering these books are in third person limited) dump description in one, focused chunk and just sound kinda gay/bi/like theyre planning on making a polycule.

I think that was the seed. But a seed without water can't grow. And neither could Tony- lmao got him- because he's. Kinda implied to be doomed at the end of GGY. Story over, main character dead. Kinda hard to ship him and Gregory unless it's like the most doomed toxic thing ever.

Except people didn't want him to be dead. I think the first fic I saw that went 'hey actually he could've survived that.' Was Aftermath. And more stories with Tony surviving somehow appeared after that. And that was the water- alive!Tony au's.

It just took people a hot minute to put two and two together, and now we've all got brainworms. The end.

#summerly talks#im not sure if i should tag this lmao because. i know i said its an effortpost. but really its just a shitpost#with slightly more effort#anyway i can now get some sleep nighty night

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

i love david ward.....

#ive written the beginnings of multiple eskew effortposts tonight but this is all you get for now. beloved character.#i just got to the part where he says in order to stop forgetting things/losing time he's giving up on sleep.#and just dissociating his 'day' and 'night' selves into two different personalities he feeds in order to stay awake. literally incredible<3#txt

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Given the amount of work they put us through for the masters courses before this I def think I'm not working enough

#they'd have me going through a paper a week#now i just sort of sit around imagining things#fuck it effortpost incoming

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

personally I’m more interested in what this transfer means for BW as a whole - since anthem (and one could argue, since at least ME3), BW has shown consistent mismanagement in their dev cycles (and iirc a lot of upper management turnover?).

there’s an anthem post-mortem out there that discusses how BW’s main studio ignored BW Austin’s advice and experience regarding running a multiplayer game/creating an engaging endgame, and how it was EA that told BW to include mechanics like flying, one of the few things praised in the game. pair that with the news that DA4 went through, what, two restarts during development, tried to be a live-service game, and now may or may not utilize AI writing in place of human writers, the one thing BW has always been known for. I’ve heard that BW Montreal also didn’t receive the help they’d requested from Edmonton during ME:A’s dev cycle, but I’m not 100% certain of that. the studio’s probably on thin ice, and it’s kind of their own fault.

(whether EA is partially to blame is another topic. personally, I think BW is far more to blame than EA, since its problems all seem internal rather than imposed from the outside. a lot of criticism that should be leveled at BW gets passed over by fans as “EA sucks!” but like, there’s more to it than that, and BW has been coasting off that perception for too long.)

what I mean is: BW is in more danger than SWTOR is, and moving SWTOR to another studio under the EA umbrella might very well be a precautionary measure by EA to keep the game running in case BW (Edmonton especially) gets shut down, which will likely be determined by DA4, a game that looks more and more troubled as time passes.

#swtor#also mmos changing studios is not unheard of and most actually do well afterwards too!#LOTRO’s gone through two or three studios and receives a lot of regular updates (more than SWTOR for sure)#but like BioWare’s poor management has been an issue for at least a decade at this point lol I have hope for the game under new management#I might make a longer effortpost about bioware edmonton and the myth of modern BW magic at some point but this’ll do for now

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’ve emotionally processed my worries and fears from the last few days, and I’ve decided I’m impressed with my friend’s response. He will have the last word on this.

#I’ve resisted making footnoted analysis of tumblr posts at 2am until now and will continue in that vein unless strongly motivated otherwise#maybe i should do a pre research effortpost on ai generative tech re: art because im honestly curious#about what is going on

0 notes

Text

Since it is the 6th of December, Independence Day, and I've recently been into march music for whatever reason here's my top six military marches of White Finland (= excluding Communist marching songs, "civilian" marches and movements from "serious" music) ranked by musical merits only. Recordings on Youtube are linked.

Jääkärimarssi, Op. 91a (Jäger March) by Jean Sibelius. It's got a great tune and arrangement, what can you say. The Finnish Civil War started the day after the première which is a bummer.

Porilaisten marssi (Swedish: Björneborgarnas marsch = March of the Björneborgers/Pori Regiment). The tune is probably of 18th c. French origin. It's the official honorary march of the Finnish Defence Forces and the President of the Republic as well as the unofficial national march of Finland. It's played on the radio and television when Finnish athletes win gold in the Olympics. The commonest arrangement includes a delightful cannon fire imitation on the bass drum in the third strain.

Narvan marssi (Narva March). Trad. Swedish funeral march, tune probably from Scotland or Ireland. Often played at Finnish and Estonian military funerals. The name comes from the Battle of Narva in 1700 where it was supposedly played as troops slowly marched through snow. There's an unrelated Swedish slow march also called Narvamarsch by Anders von Düben the Younger.

Suomalaisen ratsuväen marssi 30-vuotisessa sodassa (March of the Finnish Cavalry in the Thirty Years' War). Trad. Swedish cavalry march from the time of the Thirty Years' War. Entered into Prussian military music repertory and remains popular in German-speaking Europe. This is one of the six tunes played by the carillon of the Munich New Town Hall (thanks, Wikipedia).

Karjalan jääkärien marssi (March of the Jägers of Karelia). The introduction is the Finnish "lights out" bugle call (or "Taps") which is also incorporated as a countermelody on the da capo.

Suomi-marssi. According to Wikipedia this very Prussian sounding march was written in 1837 by a Finnish military officer called Erik Wilhelm Eriksson and gifted to Frederick William III of Prussia by Nicholas I of Russia. In Prussia it was called Marsch aus Petersburg.

#now there's a cringe ''patriotic'' independence day post to balance the war crimes post#effortpost#music

1 note

·

View note

Text

algorithms are bad, actually.

im sure someone smarter than me has said it a better way but being shown things that r specifically catered to me has fucked up the way i interact with people irl, exacerbated by staying in the house because of the pandemic, and i. do not like it. and im sure im not the only person thats dealt w this

0 notes