#music for films

Text

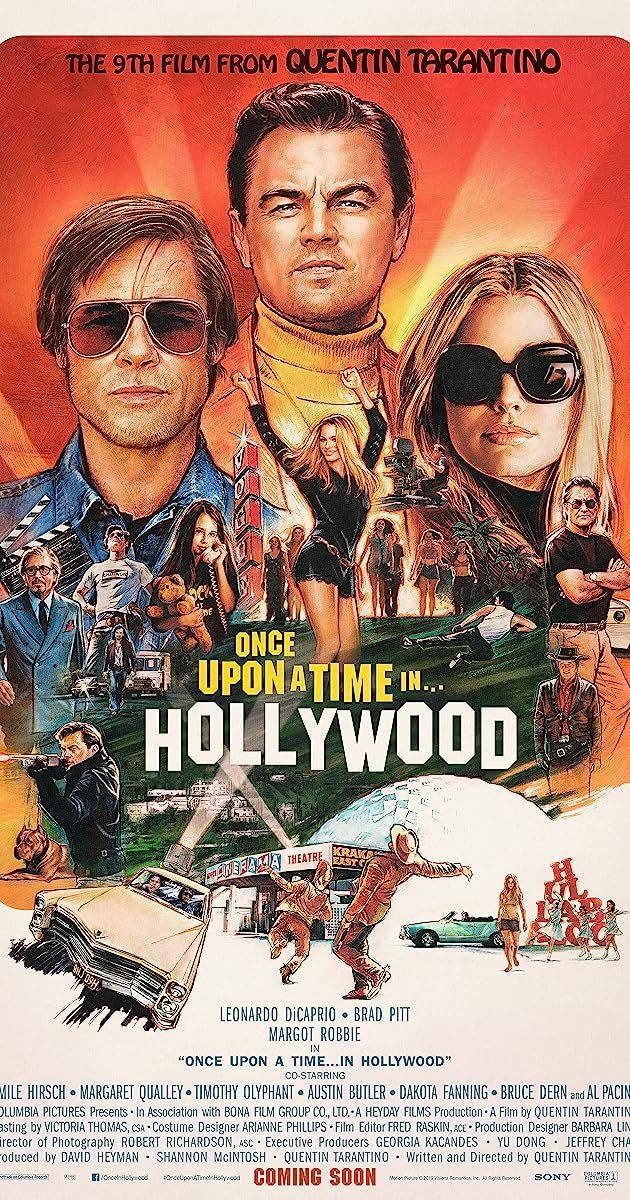

Music for Films, Vol. IV: Once upon a Time…in Benedict Canyon or, Tarantino, Redux

(N.B., I wrote an earlier piece in this series about Quentin Tarantino’s Death Proof [2007], which seemed to me to represent the apotheosis of that director’s postmodern sensibility, for cinema and for its use of pop music. That still seems accurate to me. But Tarantino’s Once upon a Time…in Hollywood [2019] turns out to be a much more interesting engagement with both of those aspects of his filmmaking, and with postmodernism, generally — and it’s also a film I admire a bit more. So we go around again. If, however, you are sick of Tarantino and of chatter about his films, I get it. For sure, he’s irritating as hell in interviews — and below, I start with some of my own irritation at his winking and ironical guffawing. But, as is the case with someone like Richard Hell, it’s useful to separate the man from the work, and if you can pull that off, the work can be pretty great.)

There are moments in Once upon a Time…in Hollywood at which Quentin Tarantino’s auto-referentiality tips over from risible cleverness into unsavory self-obsession. See the scene about 80 minutes into the film, during which Cliff Booth (Brad Pitt, effortlessly cool) finally picks up the always hitching and emphatically sexually available Pussycat (Margaret Qualley, breathlessly feral). After they connect on their shared histories with Spahn Movie Ranch, Pussycat settles into the Coupe de Ville’s massive bench seat and, inevitably, puts her feet up on the dash. Her toes smush into the windshield; the bottoms of her feet are filthy. You can just about feel Tarantino hyperventilating — or maybe he’s laughing his ass off at us. Tarantino and feet, it’s an exhausted punchline by now. And the moment is almost a direct quotation, a visually inverted rendition of the opening shot of the narrative portion of Death Proof, in which Butterfly’s (Vanessa Ferlito) feet rest on the dash of Shanna’s (Jordan Ladd) Honda Civic. Tarantino seems to want you to make the connection, and, perhaps, to feel a little bit gross about the fact that you can.

The whole scene is shot through with problematic erotic energies, generated less so by Pussycat’s directness (“Obviously I’m not too young to fuck you, but obviously you are too old to fuck me”), more so by Cliff’s reasons for not pursuing her (“What I’m too old to do is go to jail for poontang”). And Tarantino has Dee Clark’s “Hey Little Girl” lasciviously jangling from the Coupe de Ville’s radio: “Hey little girl in the high school sweater / Gee, but I’d like to know you better / Just a-swinging your books and chewing gum / A-looking just like a juicy plum.” Gee. I get the crassness of the choice, which provides an intensification of the more playful song accompanying Cliff’s first look at Pussycat on a different LA street (and about 63 minutes earlier in the film), Simon & Garfunkel’s “Mrs. Robinson.” With all the signaling, ogling and panting, it’s easy to forget the song that immediately proceeds “Hey Little Girl,” sonically framing the initial gestures of Cliff and Pussycat’s conversation.

youtube

The song is typical of Neil Diamond’s peculiar talent for constructing gravid schmaltz that is neither too serious nor too cloyingly mawkish (mostly, anyways). That emotional tonality seems a less than intuitive choice for Cliff and Pussycat’s encounter — until we remember why she wants a lift to Spahn Ranch, and who might be there to meet them. Diamond’s Brother Love is a religious huckster, a metaphysical con man, and so, in part, was Charles Manson, a wannabe acid-soaked Svengali who managed to bewitch more folks than seems believable. Pussycat’s passionate desire for Cliff to meet him (“Charlie is reeeeally gonna dig you”) suggests Manson’s poisonous influence over her. She is thus the fictional avatar of numerous women and girls, like Mary Brunner, Susan Atkins and Squeaky Fromme, who fell under Manson’s influence, utterly convinced of his psychic and prophetic powers.

Manson, as is widely known, was erstwhile friends with Beach Boy Dennis Wilson and with producer Terry Melcher. Manson first went to the house at 10050 Cielo Drive, where Manson Family members would eventually murder Sharon Tate and several others, looking for Melcher. Manson was attempting a career as sort of demented folksinger manque, and he wanted to bug Melcher about it. By 1969 Melcher was coasting on the rep he had built producing the Byrds’ hit records from 1965 and most of Paul Revere & the Raiders’ sides from 1965 to 1968 (and that band’s singer Mark Lindsay also briefly lived at 10050 Cielo), including this tune:

youtube

Watching Sharon Tate (Margot Robbie) bounce around the room is a charming experience, and Robbie’s still-youthful beauty is an interesting counterpoint to the aesthetic pleasures of Pitt’s middle-aged body. In truth, Robbie isn’t given all that much to do in Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood; mostly Tarantino seems to have told her, “Okay, be adorable” (though we should also note that it isn’t hugely easy to be adorable on demand). There may be an intent in that: to revise the dominant filmic profile on Tate, the sex kitten in Valley of the Dolls (1967) and half-naked beach bunny in Don’t Make Waves (1967), presentations underscored by a nude-photo-supplemented article on the actor in Playboy. Tarantino renders Tate beautiful — not much else one can do with Robbie — but never insists on her as a libidinally charged presence (save for a shot or two of her feet …).

Hence the smart choice of the Paul Revere & the Raiders tune. Their goofy costumes and bright vocal harmonies cast them very much in the mold of the British Invasion, with Beatles-ish overtones of mop-topped sweetness, and the explicitly anti-dope messaging of the band’s hit “Kicks” further associated them with a cleaned-up vibe, distinct from druggy counterculture. In the film, Tate teases Jay Sebring (Emile Hirsch), “Aw, what’s the matter? You afraid I’ll tell your friend Jim Morrison you were dancing to Paul Revere & the Raiders?” Morrison doesn’t appear in the movie, but in just another minute of screen time, Manson (Damon Herriman) does. Sebring stops him at the front door of 10050 Cielo, and when Tate approaches (walking past a massive reproduction of a poster for Don’t Make Waves, Tarantino just can’t help himself), Sebring tells her, “It’s okay, honey, it’s a friend of Terry’s.”

Of course, the arc of history tells us that it’s not okay. The sheen of good feeling and innocent kicks pop culture was attempting to sell in the late Sixties had been mussed up by all the “fucking hippies” that Cliff and Rick Dalton (Leo DiCaprio) continuously curse at as they drive the Strip. Even Spahn Ranch, in the film formerly the production site for Dalton’s hit cowboy show Bounty Law!, has been overrun by Manson’s accumulating freaks. That’s another historical fact that Tarantino lovingly recreates, reducing the Ranch to a relic, a dusty ghost town haunted by sweaty, fried, raggedy heads and a legion of young women, Pussycat among them (Dakota Fanning turns in a terrific performance as Squeaky: paranoid, overheated, drenched in weird, wanton ambiguities).

Their presence is disorienting, but it can’t entirely dislodge the visual logic of the cowboy film, the Western. In part, that’s due to the sheer amount of time the film devotes to painstaking reconstructions of Westerns, in cinema and TV, in LA and Italy; see especially all the minutes of Dalton on set, filming his guest appearance for the pilot of Lancer, a Western that ran on CBS through the late 1960s (and we should note that Bruce Dern, who portrays George Spahn in Tarantino’s film, did some work on Lancer early in his career). But the more interesting nods and allusions to the Western cluster around Cliff: buckling on a holster-style work belt when he fixes Rick’s TV antenna; staring down the line-up of Manson Family women who gather across the dirt lane in Spahn Ranch, like bandits inviting a gunfight; and most emphatically, his shoot-out-style stand-off with Tex Watson (Austin Butler, and more on that just below). Appropriately, when Cliff gets his first few minutes of solo camera time early on in the film, Tarantino scores it with a song that works through numerous tropes of the Western antihero.

youtube

Some might assert that a Gram Parsons tune would better suit both the Western style and LA in 1969. But I’ll argue for the Seger song, even though it was recorded when he styled his band as the Bob Seger System, not yet the Silver Bullet Band (which would get us semiotically closer to the gun and the cowboy). “Ramblin’ Gamblin’ Man” (1969) is certainly a rhythmic match for Cliff, as he careens through the city’s streets and freeways in his beat-to-shit Karmann Ghia. And check out the lyrics: a tale of a “ramblin’ man” who left home at thirteen; a past-master of roulette and dice; rugged and a little ugly, but full of macho sexual confidence. All he needs is the horse. Most significant, the song’s lyric speaker eventually notes, “Gotta keep moving, never gonna slow down / You can have your funky world, see you around.” That’s Cliff to a tee, but it’s also Sergio Leone’s Man with No Name, who is always ready to ditch the scene when the civilized world becomes too much its petulant, cynical self. Better out in the bush, among the cacti and canyons. And while the usage of “funky” seems a poor fit for a cowboy’s mouth, it’s right on point for the film’s take on LA, as it lurches into counterculture’s violent dissolution.

It's unfair to counterculture to peg that dissolution to the Tate-Labianca murders. We can more meaningfully reference the 1970 explosion at 18 West 11th Street in NYC, or Eldridge Cleaver’s fugitive conversion to evangelical Christianity, or Altamont, or any number of other events, betrayals and tragedies. But the Manson Family’s perverted use of countercultural language (“revolution,” “the pigs,” “grokking”) is particularly galling in its confusions and lunatic bloody mindedness. Tarantino is tuned into it: see Sadie’s (Mikey Madison) deranged rant about “pigs” and “fascists.” Even a year earlier, other speakers were using the terms with much greater clarity, and many of those speakers were black.

So what do we do with this:

youtube

Black confronts white. Bad guys threaten good guy. The stand-off morphs into a massacre, but not before Cliff brings up the Western again, reminding us of Spahn Ranch and of Tex on his “horsie,” belittling him and adding to Cliff’s inability to take Manson’s minions at all seriously (Cliff, to Tex: “Uh, you are?” Tex, intoning: “I’m the devil, and I’m here to do the devil’s business.” Cliff, dismissive: “No, it was dumber than that…”). Soon Brandy the pit bull is chewing Tex and Sadie to pieces, and Cliff is hammering Katie’s (Madisen Beaty) head into any number of hard, angled surfaces. (Let’s not linger on Dalton’s flamethrower.) The violence is gratuitous, meaty, precisely staged and shot. It’s a Tarantino film, after all. And in this brutally antic sequence, the film and the director shift into another generic form, very dear to Tarantino: the revenge drama.

A number of Tarantino’s films have employed revenge plots: all of Kill Bill (2003, 2004), Death Proof (2007), Django Unchained (2012). Inglourious Basterds (2009, featuring a cartoonish but still satisfying performance from Pitt) expanded its revenge to world-historical scale, using film as a weapon for culture to take its vengeance on Hitler, and on the Nazi Party’s development of cinema as a vector for political propaganda. Once upon a Time…in Hollywood is less expansive but still has complex dimensions: American pop takes its revenge on Manson, rolling back his invasion of LA’s industrial and cultural turf and reversing — if only symbolically — his extinguishment of Tate and her career, of all the images and roles she might have given us.

But it’s possible to discern other layers to the vengeance, if one listens. Running throughout the fight sequence is the Vanilla Fudge’s bombastic, psych-rock rendition of “You Keep Me Hangin’ On” (1967), which is both a suitable and a strange choice. Suitable, in that its acid intensities resonate with Manson and with Cliff, who is tripping throughout the scene. Strange, though, in its lack of a clear thematic relation to the scene’s action, which seems to have guided other songs’ selections — certainly “Brother Love’s Traveling Salvation Show,” and “Hey Little Girl,” and “Ramblin’ Gamblin’ Man” and even, in its limited way, “Good Thing.” So why would Tarantino abandon that logic here, at the film’s big, bloody climax?

As ever, with Tarantino, the layers have histories.

youtube

“You Keep Me Hangin’ On,” of course, was first recorded and released by the Supremes, for whom it was a #1 charting single in 1966. There’s a sort of pattern suggested by the film, of utterances and meanings developed in black American culture that are quickly adopted and refitted, frequently rendered vanilla (hello) and commodified, by white culture. To be sure, the Supremes also produced a successful commodity with their version of the tune. But the play among those songs and vinyl sides suggests a more problematic set of appropriations — among them, Weatherman’s use of the revolutionary language developed by the Black Panthers and Stokely Carmichael, which Billy Ayers, Bernardine Dohrn and others spouted and spun out to fringe actors, like Manson, who degraded it, rendering it nearly meaningless.

“Helter Skelter” was another of the Manson Family’s watchwords, and another of Manson’s nutty notions, alleging that the Beatles song was endowed with the power to launch a race war in America. Manson’s racism mixed paranoia with his megalomania. He envisioned an America in which blacks would murder all the white people, save for him and his followers. In his view, blacks were too incompetent to govern themselves; they would need a white leader, and it would be Manson. So while Ayers and Dohrn called cops pigs in an attempt to make common cause with black revolutionaries (who were deeply skeptical of the white kids and their enthusiasms), Manson and his minions called cops pigs out of a chaotic psycho-social melange of persecution, ressentiment and bizarre apocalyptic divination.

So maybe we should linger on Dalton’s flamethrower a bit, after all. He uses it to torch Sadie to death, the Mansonite most earnest in her identification of him as another “piggie.” Close to the film’s beginning, there’s an ersatz movie clip drawn from The Fourteen Fists of McCluskey, in which Dalton, as the fictive hero McCluskey, uses the same flamethrower to burn a bunch of Nazi officers to death. It’s another Tarantino callback, to the climax of Inglourious Basterds and the incineration of many, many more fascists (and that scene had the benefit of the fever dream of Shoshanna Dreyfus’s [Melanie Laurent] face, projected onto the celluloid-fed inferno and madly laughing, surely one of the best images Tarantino has ever concocted). But the visual synonymy identifies Sadie with the Nazis. She seems to be the fascist. She has certainly been infected by Manson’s racist manias and linguistic depredations.

That may be too clever, by half — but with Tarantino, that sort of playful cascade of images and associations that ends up feeling meaningful is generally what we get, and in this case, there is a sort of critique to be made. If the postmodern in part emerged amid the collapse of counterculture’s revolutionary agendas, Once upon a Time…in Hollywood directs its wrath at a symbol of that collapse, and of the resulting nightmares borne on dope, irrationally enraged agony (especially over Vietnam, news of which occasionally issues from car radios in the film) and harebrained political analysis by kids reading texts that had currency amid a very, very different conjuncture. While Tarantino’s revenge narrative morphs generic forms again at the end, into alternate history, there’s a way in which that mutation can be read as a useful provocation. Not just a thought experiment, or a gesture lionizing fiction’s weirding power, in some ironized celebration of relativist spectacle. But a reminder that while history has to happen the way it happens, our histories are constructions, and they tell very partial and very particular stories. It’s an old saw, now, to recommend postmodernity’s meta- moves and pop cultural saturations as testing grounds for our reading strategies, but that doesn’t make the assertion any less cogent. Perhaps, to burn through the layers of images, to burn down the funhouse of contemporary revisionisms and to fight the fascists, who continue to manipulate media, what we need is a powerful instrument: our minds, tempered by their interactions with tempting narratives that wish to tell us pleasant stories.

Or mavbe we just want to watch Sharon dance, Manson be damned.

youtube

Jonathan Shaw

7 notes

·

View notes

Audio

3:15 PM EST February 2, 2024:

Brian Eno - “Final Sunset”

From the album Music for Films

(October 1978)

Last song scrobbled from iTunes at Last.fm

–

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

ngl, I'm beginning to take issue with how in conversations about anti-intellectualism almost automatically, the face of girls and women will be slapped on the problem.

#'all those tiktok girls who only like marvel films and' - why do you always say girls and women? are the guys filling opera halls instead?#'women in their mid 20s who still only read YA novels' okay sure that's an example and relevant discussions can be had#but it reminds me of the mocking tone in which people speak of 'chick-lit' to use women's interest as an indicator of lower value#while in fact women are reading more than men in EVERY single genre of fiction. Women are doing a lot of (often unpaid) labour#supporting libaries supporting theatres supporting cultural events#meanwhile there is a pretty big overlap between toxic masculinity and anti-intellectualism#(especially misogyny and homophobia)#especially when it comes to things like ballet or opera or musical or generally dance#in fact it is often the female investment in specific things that makes them less 'valuable' in general consciousness#for thousands of years the theatre was well-respected and a high form of art - and now it's a 'wife-thing'#the father who will teach his son that theatre and dance are for girls - how is that never an example for anti-intellectualism

16K notes

·

View notes

Text

We’re looking back on this year and feeling like we just lived 13 lives? 🤯

Thanks for making it best year yet! 🫶 Also, since today is 123123, we gotta say it… 1, 2, 3, let’s go (to 2024), bitch!

#Taylor Swift#2023#Year in Review#Midnights (The Til Dawn Edition)#Karma (Feat. Ice Spice)#Speak Now (Taylor's Version)#1989 (Taylor's Version)#VMAs#Taylor Swift | The Eras Tour concert film#Spotify Top Global Artist#Apple Music Artist of the Year#Google Most Searched Songwriter#Happy New Year

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

The Sound of Music

dir. Robert Wise | 1965

#The Sound of Music#filmedit#filmgifs#classicfilmedit#userteri#usertennant#usersugar#henricavyll#tuserpris#underbetelgeuse#userveronika#userrlaura#tuserpolly#1960s#film#ours#by diana

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

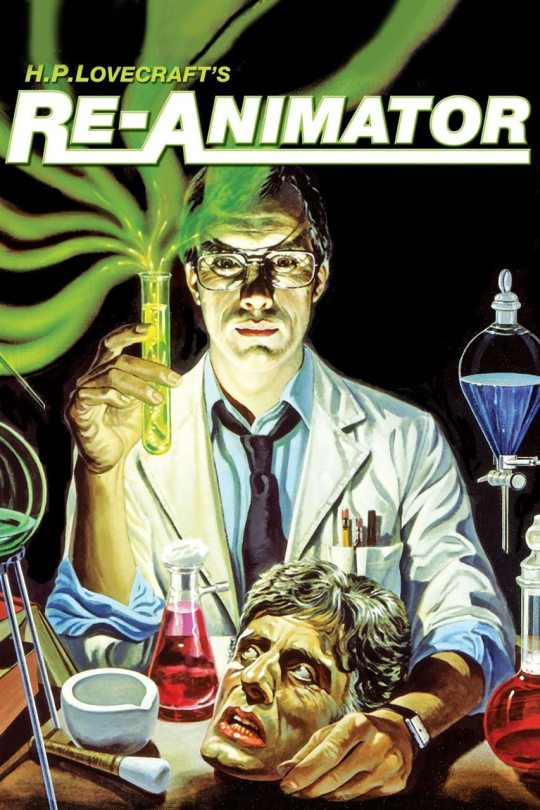

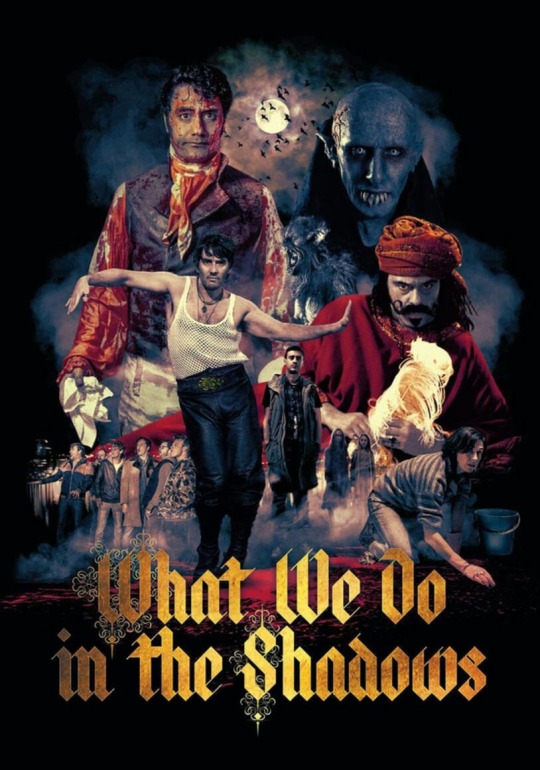

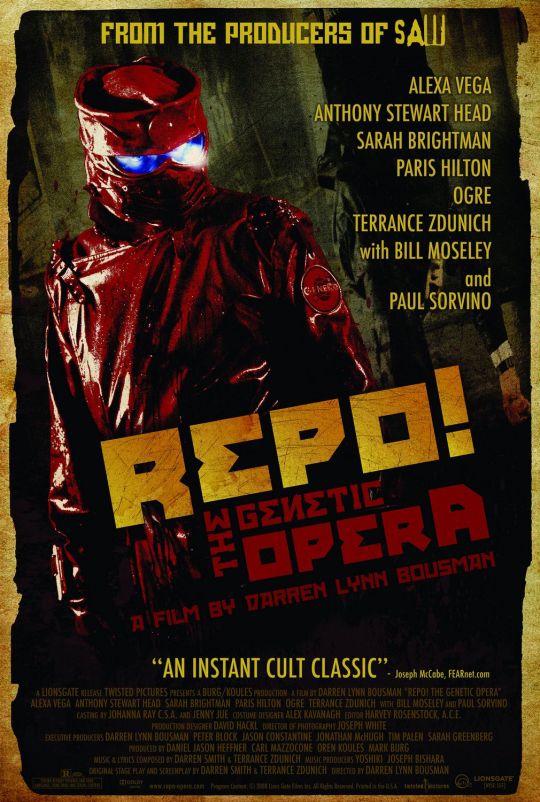

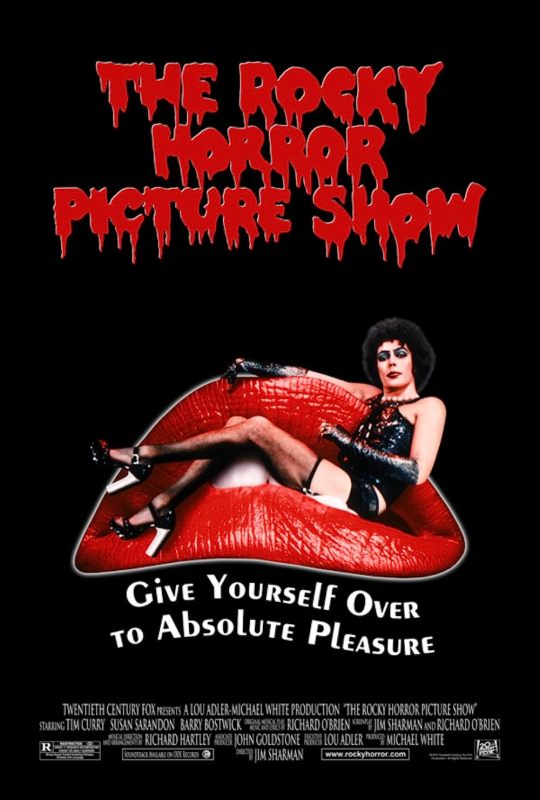

i don't know what this movie genre is called, but it's my favourite movie genre

#campy horror comedies? some of which are also musicals?#re-animator#renfield#renfield (2023)#beetlejuice#beetlejuice (1988)#what we do in the shadows#what we do in the shadows (2014)#the munsters#the munsters (2022)#repo! the genetic opera#little shop of horrors#the rocky horror picture show#bride of re-animator#movies#films

7K notes

·

View notes

Text

forever obsessed with dynamics between vampires, specifically that of a maker and fledgling, as a way to explore abuse. the creation of a vampire itself can so easily be a literalization of the lasting impacts of trauma and also much more simply the ways a perpetrator might shape their victim’s very identity. the extremes of isolation in the way that the new vampire, in most narratives, must cut all ties to their mortal life, or else go through an elaborate charade to maintain the facade of humanity, while forever still being removed from it. and the sheer dependence and vulnerability of being in an entirely new state of being, wholly uncertain of what it entails, and relying on another person to define… everything.

#or just the moral dilemmas#rewatching amc interview is kind of making me insane#that moment in episode two when louis is looking for a sort of assurance in the fact that lestat may actually have some good in him#look at how he cares about music look at the simple wondrous things that can bring him joy#and then the immediate dread when the opera performance turns out to be imperfect because he knows how lestat will react to *that*#I think there’s also something really interesting in the highlighting of lestat upbraids the less skilled singer before killing him#(slowly)#but also I will wait to watch more before I articulate my thoughts#vampires#interview with the vampire#amc interview with the vampire#i ramble sometimes#I do still find the lestat and claudia film and novel dynamic by far the most compelling for how she tries to usurp him but almost to be him#but I’m enjoying this#I’m very curious if I will like show claudia more on rewatch#the movie always resonated most with me (sue me lol) because there seemed to be more simultaneous fondness and attachment even at the end

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

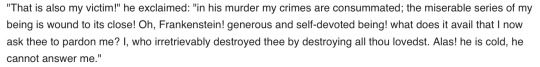

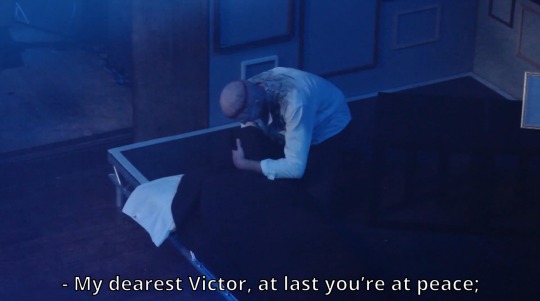

“Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus” by Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley (1818) // Frankenstein from the Royal Ballet (2016) // National Theatre Live: Frankenstein (2011) // Frankenstein: The Metal Opera (2014) // Frankenstein (TV Miniseries 2004) // Creature (TV Miniseries 2023)

Grief of the Creature across various adaptations

#I’m sorry I’m not done with this brainriot yet 🥺#Frankenstein#I like it when the Creature embraces Victor in the adaptations even though he doesn’t in the book#it feels right#he doesn’t do it in the vimeo musical or the 1994 film adaptation#he kinda does in the Puppet Opera but it’s hard to see on a screenshot

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Music for Films, Vol. III: Night of the Dying Punks

“Send more cops.”

youtube

Depending on how you’re ideologically situated, you may find that the funniest line in Dan O’Bannon’s Return of the Living Dead (1985). The joke skirts the boundary of transgression, with some surprising chutzpah. Return of the Living Dead is, after all, a gag film, among a spate of gory horror-comedy flicks that proliferated in the 1980s and ran an extensive gamut, from the brilliant American Werewolf in London (1982) to the bonkers Evil Dead 2 (1987) to the utterly demented Re-Animator (1985; and for reasons obvious to those who know the film, it’s hard to find a safe link to its most infamously tasteless — ahem — moment; giving head has never been more awfully literalized). O’Bannon’s movie doesn’t have the gonzo visual creativity or the semi-satiric incisiveness that characterize the comic energy of those other, better films. But Return of the Living Dead has a sense of its subgenre’s history that allows its lowbrow cultural orientation to exceed its own limitations, more frequently than it probably has any right to. And it has a well-selected soundtrack.

youtube

The film only incorporates a few seconds of “Eyes without a Face,” and it's hard to say how many ticketholders in those 1985 theaters would have been familiar enough with the song to appreciate the suggested pun: Flesh Eaters, har har. Of course, the pun’s obscurity may have been on point, since “flesh eater” is too broad a term. In the film’s iteration of the zombie mythos, the ghouls have a very specific appetite, rapturously intoning, “More brains!” The laffs cascade, and to be sure, Return of the Living Dead is often waggishly idiotic. The movie’s surface values are interested in satisfying simple, moronic pleasures, targeted to the young and primarily male audience attracted to horror flicks in the 1980s; see especially Linnea Quigley’s performance as young punk Trash, who spends nearly all her screentime naked or barely clothed. The gratuity of her nudity complements the lurid bloodshed, the dumb jokes and the movie’s revelry in its drooling, goofy trashiness.

The folks that built the soundtrack struck the right set of tones, matching that trashy sensibility. 45 Grave, the Damned and the Cramps are all represented, bands that operated on punk’s periphery and were as interested in campy humor as they were in aggro, hard-knuckled rock intensities. 45 Grave had always been more goth than punk, and the Damned was following a similar trajectory in 1985. But perhaps more than any other act on the soundtrack, the Cramps fit the film’s giddily queasy aesthetic. In 1985, the band was riding as high (in numerous senses of the word) as they ever would. Recently freed from legal wrangling with IRS Records that had prevented them from releasing new music for a few years, and fresh off a tour of the UK, where they were hugely popular, the Cramps had good reasons for happiness. But “Surfin Dead,” their contribution to Return of the Living Dead, is at best an inane confection, more honestly evaluated as a grab for quick cash. The song pales lifelessly in contrast with the kind of libidinally anarchic rock the band was capable of producing.

youtube

“Tear It Up,” popularized by Johnny Burnette in 1956, is among the rockabilly and rhythm-and-blues tunes the Cramps transformed into feral rave-ups and torch-song nightmares: Ricky Nelson’s “Lonesome Town” (1958); Mel Robbins’ “Save It” (1959); Hasil Adkins’ “She Said” (1964); Elvis Presley’s “Do the Clam” (1965); the Groupies’ “Primitive” (1966); the list goes on, at some length. The band’s interest in the pop detritus of an earlier period in rock music tracks alongside some of the more interesting cinematic aspects of Return of the Living Dead, whose young punks and middle-aged characters—notably Clu Gulager as medical supply huckster Burt and Don Calfa as mortician Ernie, in a nimble performance, by turns slyly funny and soulful—grapple with a mounting plague of zombies. As they struggle and bicker, their tactics and debates track alongside the plot and character tropes of another key text from the 1960s’ cultural underground, George Romero’s Night of the Living Dead (1968).

The references to Romero’s film start early in Return of the Living Dead. When medical supply workers Frank (James Karen) and Freddy (Thom Matthews) head down into a warehouse basement to gawk at some not-yet-animated corpses, O’Bannon quotes directly from Romero: the basement door, the wooden staircase, the lighting, the camera’s vantage all recall with precision a shot near the end of Night of the Living Dead, when Ben (Duane Jones) locks himself in the besieged and soon overrun farmhouse’s cellar. O’Bannon, who also wrote Return of the Living Dead’s screenplay, references other crucial moments from the earlier film: Ben and Harry Cooper (Karl Hardman) arguing over whether it’s best to retreat into a space with a single entry and exit point; Tom (Keith Wayne) and Ben exiting the farmhouse in a doomed attempt to retrieve an escape vehicle. None of it ends well, in either film.

youtube

Numerous critics and film historians have read that closing sequence of Night of the Living Dead as a lynching, a forceful response to the unsettled cultural anxieties intensified by the late-1960s radicalization of the Civil Rights movement. It appears to be a more serious engagement among pop culture, strongly coded symbolics and America’s repressed terrors when contrasted with the Cramps’ psycho-sexual freak-outs—but listen to Lux Interior work it out on “Fever” or “The Natives Are Restless” and the contagions may not seem so dissimilar. In any case, Romero’s additional zombie films incorporated satiric elements, some of them broadly comic (see Dawn of the Dead’s antic renditions of consumer culture) others sharper and more bitter. Day of the Dead, Romero’s third zombie movie and surely his bleakest, was released less than a month before Return of the Living Dead, in July 1985. It is certainly Romero’s most spectacularly violent film, in which an underground tunnel system full of scientists and military servicemen is invaded by a horde of ghouls. The climactic scenes of evisceration and intestine-munching carnage are prolonged and painstakingly horrendous.

Those images from Day of the Dead have an apocalyptic feeling, in tune with the film’s grim bunker mentality. It very much typifies its doomstruck, late-Cold War social context, when Reagan’s anti-Soviet rhetoric and enthusiastic support for nuclear missile systems intensified the superpowers’ antipathies. The film’s tunnel system may put you in mind of the underground warrens envisioned by some in Pentagon, through which mobile MX missile deployment technologies might move, evading Soviet tactical bombing assaults. Return of the Living Dead was made in the same context and atmosphere, and its response is much more emphatic.

youtube

It is also a good deal clumsier, a violent tonal shift that is out of proportion with the movie’s own representations of violence. Those are largely cartoonish, characterized by explicitly silly gross-out enthusiasms. For the flick’s first 80 minutes, the bloody effects and occasional chills are in tune with the dominant atmosphere of dippy frivolity and cheap thrills. The sudden turn to social critique fails to instill either fear or rage. Put it this way: Imagine the Cramps attempting a straight cover of Bob Dylan’s “Masters of War,” and you’ll have some sense for the weirdly wincing, mostly flat affect generated by the mushroom cloud in Return of the Living Dead. It wants to be horrific, or at least outrageous, but it ends in a shrug.

In that way, “Nothin’ for You,” the TSOL song on the movie’s soundtrack, ends up being oddly apt. “Nothin’ for You” found its way onto TSOL’s Revenge (1986), one of the records the band made while it coped with Jack Grisham’s departure and attempted a turn toward hard rock, aping the energies of younger Sunset Strip bands like Guns N’ Roses. One could note that the obvious TSOL song for Return of the Living Dead’s soundtrack would seem to be “Code Blue,” the necrophiliac anthem from the band’s death rocking LP Dance with Me (1981). But that song is distasteful in too confrontational a fashion. The vanilla, hair-metal-adjacent tones of “Nothin’ for You” are much more appropriate to the movie’s real imperatives: lascivious shocks, mild scares and lots of ticket sales.

So Return of the Living Dead provides a useful — if sort of unfortunate — index for the situation of transgressive cultural forms like horror cinema and punk music in the mid-1980s. Some genuinely interesting and intense horror films were being made; see Gerald Kargl’s Angst (1983), Brian DePalma’s Body Double (1984) and Day of the Dead for a selection among international, major studio and independent productions. And records by the Crucifucks, Black Flag and Butthole Surfers were continuing to move punk into discomfiting, vexing and exciting shapes. But the schlock was also arriving, in ever-increasing proportions that had the effect of diluting and even sanitizing the forms’ inherent sickness and threat. And when you’re working with already commodified genres, conceived at their core as commercial media, the dominant (and ultimately confining) logic of the culture industry can be hard to resist.

youtube

Jonathan Shaw

#music for films#night of the living dead#jonathan shaw#dusted magazine#return of the living dead#the flesh eaters#the damned#the cramps#punk#horror cinema#tsol

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

5:28 AM EST January 19, 2024:

Brian Eno - "Sparrowfall (2)"

From the album Music for Films

(October 1978)

Last song scrobbled from iTunes at Last.fm

--

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Note: this list references the 1961 version of West Side Story and the 1954 version of A Star Is Born.

#american film institute#afi#musical film#movie musical#old hollywood#old films#old movies#vintage movies#technicolor#classic film#classic cinema#singin in the rain#west side story#west side story 1961#the wizard of oz#the sound of music#cabaret#mary poppins#cabaret 1972#my fair lady#an american in paris#meet me in st. louis#1930s movies#1940s movies#1950s movies#1960s movies#1970s movies#movie polls#a star is born#a star is born 1954

944 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thinking about film scores & concept albums & auditory storytelling

#grrr argh bite#it's so!!!!!#i love you film & tv composers you're my world#film scores#songwriting#narratives#music#film#leitmotifs#media analysis#themes#motifs#she speaks!#id in alt text#15k

19K notes

·

View notes

Photo

THE SOUND OF MUSIC (1965)

dir. Robert Wise

#tsomedit#the sound of music#filmedit#filmgifs#musicalsgifs#romancegifs#dailyflicks#fyeahmovies#cinematv#filmtv#dailytvfilmgifs#**#film: the sound of music#1k#2k

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

Might as well dance a tango to hell. At least I'll have tangoed at all.

#rent 2005#rent movie#anthony rapp#tracie thoms#mark cohen#joanne jefferson#rentedit#rent the musical#musicaledit#userbbelcher#userstream#cowboycoven2#chewieblog#filmtv#cinemapix#cinematv#fyeahmovies#moviegifs#filmedit#filmgifs#2005#mine*#films#tango

755 notes

·

View notes

Text

#polls#personally i dont like it but thats only because i dont like fandom. the type of stuff that gets the most attention#in fandom usually just annoys me idk. how to explain it in a way that wont come off as me saying#fanfic or whatever is evil its just the fact that it just bombards alot of the conversations?#i prefer it when the thing i like has 10 fans and theyre all on one message board or forum#like for example mtvs downtown is getting popular but apart from annoying#'me and the mid nerd guy i copped by being weird and sexy' posts its not awful....#but then smth like... clone high or smth i suddenly cant remember ppl just got so annoying abt that show??#like i cant stand it i dont even bother watching it anymore plus its just weird to me now like i can't watch it regardless#im just rambling but personally i do not like it. like i dont want what i like to get a revival#i dont want anything new! i just want to enjoy the thing and move on 😭#fandom seems to prioritize shipping and memes over evaluating or simply just enjoying something!#this goes for anything. music film tv books....

948 notes

·

View notes

Text

Josephine Baker

French postcard. Photo: Roger Viollet. Caption: Josephine Baker (1906-1975) American music-hall artist, May 1926.

2K notes

·

View notes