#milenko

Text

As They Covered The Sun With Swords They Had Bloodied, I Found Your Eyes Like A Worship Song of Old

A Tamnana centric spin-off to @ilyamatic‘s pirate au.

Set during the first decades of the XVIII century, Aelius Anatole, or Inti Ankuwilla, as history might or might not remember him, meets a certain Tamryn Olenev as his family relocates from Poland to Venice. In meeting each other and falling for each other, the two of them will discover a kingdom of their own, where they can figure out what it is to exist despite all odds telling you not to.

Tamryn & the Olenevs belong to @valhallanrose. This piece is for you too.

This work is one complete piece of 16k words, but for easier reading I will be dividing it in parts. You can also find footnotes at the end.

Author’s notes, important references and content warnings: Just like Abby’s series this is set in the historical XVIII century, that means this work contains depictions, implications and allegories to racism towards black and indigenous peoples, anti-semitism, islamophobia, and LGBTQ people.

Despite none of these are the central focus of the work, this does include allusions to legitimate aspects of colonial violence in what we now know as Latin America. Reader discretion is advised. This piece also contains mild lemon content, so minors DNI.

However, like everything else I write about Anatole and his family, it is a testament that solidarity can be built, and our lives can be full of joy despite all odds.

While this work has footnotes where it’s needed, the following resources are some of the material used for it: Saphi.Quechua, Diksionaryo de Ladino a Espanyol, A Rainbow Thread: An Anthology of Queer Jewish Texts from the First Century to 1969, (Article, behind a paywall) Medieval Hebrew Poets 'Come Out of Closet' in New Anthology, Life is with People: The Culture of the Shtetl, Las Venas Abiertas de América Latina (*).

If you find any typos or inaccuracies, or have other sources you want to throw my way, please do so. I welcome them in DMs.

PART 1 (4K WORDS) | PART 2

The Olenevs arrived from Kraków with few personal belongings, yet they carried all the books they could with them, as if Evalina’s chemistry or Galen’s studies of the human body were as important as food and clothes themselves.

Anatole understood.

They arrived speaking yiddish, having left their Shtetl for reasons they only half-said, therefore only half-existed to the rest of the world that weren’t them. Nor the Cassano nor the Tesfaye needed them to say them out loud: they already knew that the details might change but the stories of displacement were always the same. Besides, their contact had given them all the information they needed that the Olenevs couldn’t provide themselves.

They were a family of bright, determined people, and Galen and Evalina themselves had said “a little sun from the south might as well do wanders” in broken, accented venetian. They had heard what the Cassano did for Jews seeking to escape Spain and Portugal, that was auspicious enough for them.

The only reason Anatole was there was his habit of tagging along to whatever Milenko was doing, as long as he didn’t have his own responsibilities to attend to or something more pressing urging for his attention. It was a day like any other, years before his first real contracts, before he became the accountant of Andrico’s Solanaise II, during the eve of the year he would defend theses and finally become a Doctor of Philosophy.

Perhaps there had been a reason for him to be there, after all. It was one of the days where he looked perfectly fine, but the toil of everything that had come with his choice of formal education weighed him down. Stared him down until he felt like he would sink into the claws of something which would harm him; stared him down with the unfeeling eyes of Gods and Saints and Priests which looked nothing like him or the hatred of cultures that despised him just because he existed.

So before bitterness could poison him (he would not take it, he would not be fed the insidious poison of the Conquistador. No, he would be better), he followed his cousin, searching for something to remind him why they, his family, did what they did, why he did what he must.

To some of these people the Cassano meant protection and kinship. Offering to help the Tesfaye with the new family that had just arrived to their community was a good way to take his mind off that day, when he felt his own head working against him and like his knees would falter.

When breathing in the sun didn’t help dispersing the simmering hatred he didn’t want to have inside him, when nothing he did could disperse ghosts of European tongues speaking behind his back, he followed Milenko.

They met the Olenevs in one of the parlours of Amar and Zipporah Tesfaye’s small printing business. Evalina, the mother, a chemist; Galen, the father, a jewish convert and a doctor; Zelda, his apprentice, and Him. Standing there, next to a window, tracing his fingers over a sculpture on a shelf next to it.

First there was his face: fair but with life to it, housing two bright blue eyes like some stolen, precious stone or a new brand of royal blue he wished became fashionable so he could see his eyes everywhere. Anatole had never found blue eyes interesting, most of them were pale and limpid, as if the men and women from Europe were all one pink blob of flesh and fair hair.

Not his. Him who turned towards the sound of his voice, towering over him and had delicate, embroidered flowers on his clothes. His blonde curls like the sunlight over water, crowning his beautiful face like honey dripping from the sun itself. His hands were soft and shook his own with a gentle squeeze.

This was the earth itself turning on Anatole for almost succumbing to hating it.

“This is Tamryn, he’s our eldest,” Evalina said.

“It’s a pleasure to meet you,” he said in a deep voice that was polite and pleasant and hopeful like the sun-rays at dawn.

Zelda noticed how Anatole’s hand lingered.

“He was also the prettiest boy in our Shtetl,” she said, with a cheek that reminded Anatole of his cousin Amparo. “At the age of 18 there were families lining up to ask for his hand in marriage for their daughters, but-”

“Zelda!”

Anatole felt his cheeks warm. A true feat of character for he rarely did so. Even if he suspected she might become the death of him, because of the way she seemed to see right through him, he liked Zelda already. Still, part of him that was always alert, always vigilant frantically wondered why she would say something like that. Was it recognition or was it a threat?

“What? It’s true! Men were always his type, especially, if they’re as pretty as our new friend and I was more than content with entertaining the daughters—”

“A week, Zelda, couldn’t you have waited a week before you made declarations like that?”

She looked unrepentant and Anatole laughed. He had nothing to worry about, and even if he did, he was in Venice, after all: nowhere in the world he was freer than here, under the protection of his family, where he felt like he could be nothing but a sun-kissed, perfumed boy with a bright future ahead of him.

Perhaps that was all he needed to be that day, to remember.

“Then I will do my best to live up to expectation, as long as Tamryn and your parents allow it.”

Framed by his furious blush, Tamryn’s eyes looked even prettier.

* * *

Tamryn was a soft, gentle man. Inventive, ingenious and with a hunger for knowledge and learning that Anatole felt outdid his own. Unassuming, like the winter winds announcing new life, he had crept into his heart just as easily as his sister did; but where friendship had grown for Zelda, love was growing for Tamryn. He couldn’t say when it happened: one day he just knew he wanted to make a home inside him. One day he just knew no one was as dear to him as Tamryn.

Yet sometimes, fear hounded him like a war-dog. Fearing the loving relationship he had always wanted for himself to find would skip him, slip away from his fingers entirely. That there was always going to be something preventing it. He had loved other men before: there had been Navneet, who had come and had gone, there had been fucking Andrico, whom he had pursued for two years with no indication that he was opposed to it until the night Anatole had gone to kiss him and Andrico said he had always thought of him like a younger brother.

He understood they had grown up together, but Anatole did not know in what world putting a flower on the ear of a man, while being yourself a man, was not an obvious sign of romance. Granted, Andrico’s forte was being pretty, it wasn’t being smart.

(You’re missing Decimo, a sabotaging voice in his head said. He said he loved you.

That wasn’t love, Anatole told himself. I was made to be worshipped.

Something in him had sharpened after that. Something in him had changed. Something in him had become like the very sun above his head, sizzling and burning, giving life no longer.

A misplaced Greek Chorus, re-imagined by modern ópera sang: Ccollanan Pachacamac ricuy auccacunac yahuarniy hichascancuta.) (1)

It was the festering bitterness that told him men who learnt to speak like him, and therefore learnt him existed only in his imagination.

Then, one day, unprompted, Tamryn said: “My sister tells me you sign all your letters as Inti Ankuwilla, Aelius Anatole Radosevic-Cassano. What does Inti Ankuwilla mean? I am butchering the language like a gruesome steak hanging in some store, am I? We do dual names too, I am Tamryn, but in shul I answer to Feivel ben Chaim v’Elisheva-”

He went on talking and asking questions, connecting them with other things Anatole had said about him, as if everything that was confessed to him was a gift of its own, but finding himself in want of more of it, he sheepishly came to ask if he could have some more. Yet his voice quieted as he noticed Anatole wasn’t replying.

He was too busy looking at him in stunned silence.

“I was asking too much wasn’t I? I’ve heard about your family, about what you do, and every chance I have to talk to you, you're always so interesting and always care about what I have to say. I— I shouldn’t have asked. I’m sorry-”

“No!” Anatole said, snapping back to his present circumstance as if the earth had zapped him with lightning, “don’t apologise. I, I love your questions. I just didn’t expect you to care about that.”

Tamryn sat up to his full sitting height, brow furrowed. He slouched again, eyes darting everywhere but towards Anatole as his tell-tale blush began to show up against his skin. He bounced his leg and squeezed the back of his neck with his hand.

Finally he found his words, which came out in a confused wisp of his voice: “Have I done something to make you think I don’t care? Please let me apologise.”

Oh no, Anatole thought. This was almost as mortifying as Andrico calling him “little brother”, but definitely worse overall. The last thing Anatole wanted was Tamryn to think he had caused him offence when he brought him so much joy.

“No, no, never,” he said, giddy and apologetic as he fidgeted with his hands. He took a deep breath, exhaling with a huff. Before he could convince himself otherwise, he pushed himself to sit next to Tamryn, gently shoving his elbow against him in what he hoped came out as comfort.

He dared not touch him more, but he noticed the neck of his shirt was crooked.

“Here,” he said, reaching out to fix it, “let me help. You have done nothing to cause me offence, and I realise how mean that sounded. I’m sorry, even if I’m surprised, I’m glad you asked. It’s just complicated, at times. To find people who care, that is. Actually care.”

“I do care.”

“Well, as long as you know I also care about you.”

Tamryn blushed again, shifting uncomfortably in his own clothes. “Why?”

“Seriously? After what you just said, are you seriously asking me—”

“Well, I don’t know! I guess I am. I never claimed to be very smart!”

“Oh, that’s some bullshit.”

“Anatole!”

“It is what it is! Do you want me to answer your question or not?”

“Yes please, sorry.”

Anatole rolled his eyes affectionately. “That is the name my mother gave me. ‘Inti’ is the Sun, our God of the Sun; ‘Ankuwilla’ means he who sacredly resists. Dual name, for a man who transited into being one. She— when she was taken from her community, I don’t want to go into how, a couple from Spain gave her another name, Luisa. She learnt it comes from German, something along the lines of ‘‘great battle’. Well, she decided it would be quite ironic to name me Ankuwilla.

“Everyone called me ‘Lilu’ while growing up, when they weren’t calling me Inti. Because as you can obviously tell, despite what I may project, I am not particularly tall. My father is almost as tall as you, and everyone else I grew up with was taller than me.

“My parents didn’t want me to go through anyone, here or in what they call the Indies, to choose my name for me. So I chose Aelius Anatole so it kept the meaning: my mother named me after the Sun, so I named myself after the Sunrise. It’s happened to a lot of us after the fucking Spanish decided to come in uninvited. One thing is what we call each other, and another is, well— I’m more than sure that you get it.”

“Is that why you didn’t introduce yourself like that outright?”

“Besides the fact most Europeans refuse to acknowledge my name?”

“Well, yes.”

“Most people I’ve met pronounce Runasimi horrendously.”

Tamryn laughed, and Anatole found himself laughing with him.

“Your father speaks it, though, doesn’t he?”

“Yeah, he learned from my mother. Actually, most of my family whom you’ve met speak it too, and when I wasn’t in Venice, the commune we stayed in also had a couple of Runasimi speakers. Like, my mother’s best friend, Zia Solange speaks Yoruba, so I speak a little Yoruba as well. We managed.”

“If I ever asked, would you teach me?”

“What, Yoruba? I don’t think I know enough to teach you—”

“No, I mean, Runasimi.”

Anatole was doomed.

* * *

From then on, every time he was in Venice, he would show up every second day at the doorstep of the Olenevs, around the same time, with the same question:

“Evalina, Galen, I wanted to know if I could take a walk with your son.”

Zelda teased them both, uncaring for either of their teasing about Amparo Cassano’s clear predilection for her, or how she would be asked why didn’t she have a Patron, as an actress and dancer, and Amparo wittily replying why have one when so many adored her performances, while her sea-glass green eyes stopped for Zelda and Zelda alone.

“One day,” she told her cousin, “I will relocate with Zelda to the Caribbean, and I’ll dance with my sword only, to the song of Freedom alone. Me and Zelda.”

She paused. “You should ask the same of Tamryn.”

Anatole hardened against his own desires. “I couldn’t. I can’t deprive his family of him and vice versa.”

“Have you ever thought they could be of great help?”

“It’s too dangerous.”

“Zio Vlad isn’t in the frontlines.”

“But we are.”

“This isn’t like you.”

“I’m sure he thinks I’m too young.”

“That’s a lie and the worst excuse I’ve ever heard.”

“He despises violence.”

“You don’t like it that much either. Since when are you synonymous with it?”

“He’s not the one who’s signing our Contracts of Accountancy. His life shouldn’t be one of our collaborators. He deserves soft mornings, fluttering kisses. Someone who can spoil him rotten. Someone who won’t might-not-come-home one day.”

“You’re being impossible. You’re being so deliberately obtuse, you’re starting to sound like someone who knows nothing of Hebrew peoples. What on earth would make them different from Zia Aurora or Zia Zipporah? Of Zio Amar, Sisay Lior or Tafari? What makes him different from Milan himself?”

(In his mind, Anatole can see his cousin, his soft, joyful cousin, trying to soothe the surviving people who from a Slave Ship.

Through the sound of the lapping water of the Venetian canals, he could hear his voice:

Piénsalo, Milan voice echoed, desha ke se vayan. Tú tienes tu alforría, pa’ que kyerría la nuestra.

The guard was crying inconsolably. How his cousin could do that, Anatole didn’t know. ¡Dejádme! ¡O he de llamar al Almirante y él verá qué hacer con vosotros!

Desha ke se marchan—

His voice was soft, but the guard’s was not. ¡Cállate, hereje hijep—!

Anatole kicked the guard behind his knees, covered his mouth with his hand and pressed his pistol against the guard’s temple. Vuelve a hablarle así y te vuelo la cabeza.

Later, Milan would tell him that wasn’t necessary. Anatole knew he was teasing him because he said he wouldn’t forgive him if he bloodied his good shoes, and Anatole knew that was a lie. Milenko never lied so he knew he was teasing. Anatole didn’t laugh, Milan worried.

Ke pasa? His cousin asked.)

“I would never forgive myself if something happened to him because of me.”

Amparo looked at his cousin with tenderness and understanding. There were four of them that worked together, all of them too young to do what they did, but this was the life they had. Lives which were worth fighting for, tooth and nail, all the wit and irreverence in the world. Theirs was a family of Others, and with Others they had made their life ever since the times of Arianamenzi. Artemisia, Amparo’s younger sister and Milenko weren’t similar at all but in one thing: they were sensitive beings, of hearts that beat like birds or wells.

Amparo knew that Anatole and Milenko went together, the sun and the moon of their family, just like she and Artemisia always would —a tie like a string, like hands which would not unlink themselves no matter what— Anatole and her were the same in the same way Artemisia and Milenko were. While Milan and Artemisia’s lives were about finding themselves, Amparo and Anatole were beings of excellence.

They defied expectations, they found a way to achieve the impossible and they did things twice as well. They lived with passions burning like a thousand suns, like a bubbling volcano. Like the earth shaking its core or like life which was reborn in winter and came to die in spring. They both were excellent: no one danced like Amparo, no one sang like Amparo, no one acted like Amparo, and white girls who had their sex handed to them, instead of having to make it for themselves hated her for it.

Anatole spoke 11 languages, he played the harp and the piano. He had been the best qualified and the most competent person within his studies, and yet it was never recognised, as a “lesson in humility and Christian values” from pasty, powdery white monks and academics that knew nothing of him and saw in him whatever they wanted to see. They had no problem using him as a tale of exceptionalism while leaving him in the open field for wolves to bite. No one thought like him, no one found a way to connect people like he did, no one wrote as well as he did. No one knew the classics and the poets from Asia like he did.

In another world, a world which didn’t hate them, he would’ve been the greatest politician of his century. Instead, they paid him with a knife to his back.

They both were forces to be reckoned with, and if these people didn’t acknowledge it, they’d make themselves impossible to ignore, like the feeling of Death luring in the corner, breathing your same breaths because every breath people took was a breath closer to their last one. They were that. Cunning, young and full of edges.

Efficiency and excellence had made them ruthless, yet inside them there was softness. Amparo was all soul. Deep down, a quiet girl who enjoyed thinking about ghosts and chasing stories. A girl who danced because her heart was too big, beat too loud inside her chest, heavy with her sorrows. Anatole was the sun. Inti Ankuwilla. He was hopeful dawns, wells full of ideas, Atlas triumphant, Atlas loving, Atlas unwavering. A polite man who just wanted to help people and took only what he needed for himself. A lover of art and soft fabrics, who liked singing and playing the pianoforte and the harp.

Amparo thought he deserved better than his own doubts.

“Listen. I know better than trying to convince that stubborn head of yours, but I think we deserve our happiness. I think, or I want to think, that we deserve to be chosen like we choose our fights. With bravery, with rebelliousness, with inventive might of the little chances we might have of having a life of our own.”

“Our lives are our own.”

“They are. You know better than I that we don’t do what we do because we’re bitter, but because we dare not have a life and not live it at all. As long as we’re loved, I want to think we cannot die in any way that matters.”

She kissed her cousin’s crown. “Don’t deny yourself that chance.”

* * *

In the sunset, Tamryn looked as if gold had had a love affair with roses.

They were talking to each other in an empty alleyway, adjacent streets seemingly just as empty, and there were no boats in sight. The sounds of the sestieri were muffled and distant as they reached them. They were standing close enough for their hands to brush as they spoke, close enough for Anatole to be able to see Tamryn’s eyelashes bat against his skin.

Their alleyway felt like it was a Kingdom of their own.

That day was the second anniversary of their meeting. Tamryn knew Anatole now, he knew his thoughts, he got letters from him. He knew some of his fears, he knew his perfume and the scent of his hair oil. He knew his favourite flower and all the dreams he tried to fulfil despite living in a world insisting he shouldn’t. If that could be said of Tamryn, the same could be said of Anatole.

He would recognise Tamryn anywhere and noted all of his absences. He knew his preferences and his fears, he knew the warmth he radiated when we walked into a room. He knew he wanted to ask his opinion on things, even when it wasn’t necessary, just to have an excuse to talk to him. He saw him in the Caribbean sea when he was away, he saw him with closed eyes when he was sleeping in his own bed in Venice, wishing he was there beside him.

If Anatole’s strength were ever to run out and Death were to come to his doorstep he hoped Death had the mercy of wearing Tamryn’s face. He had no intention of dying —his hopes were set on living— but if he were to die before he wanted to, he would follow Death gladly if it wore the face of his Dearest Friend, because his Dearest Friend was the most beautiful man he’d ever known.

Tamryn’s hand rested in the crook of Anatole’s arm. His lips looked pink and soft as they smiled at him. He licked his lips before speaking, and Anatole could see just a flash of his pink tongue against him. He wondered how it tasted. Would it be warm against his own? Would their lips fit each other like he often daydreamed of?

Anatole wanted to kiss him.

Perhaps it was because he would have to leave for the Caribbean. He had a new contract to sign, he had work to do, and all the work he could get done in Europe was done with. Perhaps it was how Tamryn let him press him against the wall when they heard footsteps go by, even if they were a false alarm and no one came. Perhaps it was how he looked. Perhaps it was his own heart. Perhaps it was Amparo’s words finally getting to him.

He wanted to kiss him, so he did.

He kissed him as if Odysseus had given into the Sirens, letting the creatures and Homer’s wine-dark sea devour him in fantasies. He kissed him as if either one of them was Venus sprung from the seafoam. He kissed him like Milenko’s Sufi poets spoke of how love must be. He kissed him like the sun kissed the Andes every morning, and the rain the valleys where harvest used to grow. He kissed him as if he was the sole centre of the world.

As if Kepler and Copernicus knew nothing and the world orbited around him, only if Tamryn was like a dipped in honey sunray, then perhaps they did understand something after all.

Tamryn had never been kissed so indecently. By the time they pulled apart, he was breathless and had completely forgotten where they were. Never before had he wanted to be kissed again by someone so badly.

“You kissed me.”

“I’m— oh, no, Tamryn I’m so sorry, I wasn’t thinking I— I’m so sorry.”

“No, where- why are you moving back? No, no I’m sorry, I shouldn’t have said anything.” Tamryn looked like he might cry.

“Just please let me explain-”

“Please tell me you don’t regret it. Please kiss me again.”

“I— What? You want me to kiss you?”

“Since the first month we met.”

“But I’m—”

“So am I.”

“That’s not what I—”

“Changes nothing.”

“But—”

“With Elohim as my witness, please kiss me again, please.”

He was doomed, this man would be the death of him. This man would drive him crazy; maybe he had already, because as surely as the Sun rises and Wiraquchan gave his people life force, he kissed him again.

* * *

When they arrived back at Olenev’s home, Anatole’s uncles, Valeriy and Atanasie, were waiting for him.

No, Anatole thought, I haven’t told him I love him yet.

His uncle Valeriy, his father’s brother, cupped his cheek. “Inti, mana chaniyuq kaqtinqa manan kaypichu kayman.” (2)

“Moram mu reći da ga volim.” (3)

Anatansie squeezed his shoulder. “Let us explain.”

Untangling his fingers from Tamryn’s was the hardest thing he had ever done, but the moment both of them explained why they had come, Anatole knew he would’ve had to let go of Tamryn’s hand regardless, that his feelings would have to wait.

Not because they didn’t matter but because not only was there a lead on someone trying to capture his new Contract. He was to take over his Zia Solange’s, Captain of the Solanaise, accounts. She had passed her title to none other than Andrico himself who, for some reason, had taken uncommonly long in talking accounts with the Cassano. Solange, her husband Mustafa (both of them former pirates) and their family weren’t just friends and collaborators of the Cassano, they were their most important clients when it came to sabotaging both Imperial supply chains and Slave ships.

The lead pointed to someone Anatole had sworn to chase out of the world if he ever had the chance: Decimo Lemione.

Anatole had to leave. All he could do was promise Tamryn he’d come back.

* * *

FOOTNOTES

(*) The Venas link leads to the whole book in PDF in its original Spanish. I believe this is what Galeano himself would’ve wanted.

(1) “ Ccollanan Pachacamac ricuy auccacunac yahuarniy hichascancuta”: Meaning ‘Pacha Kamaq, witness how my enemies shed my blood’, according to several sources these were the last words of Tupac Amaru I before his execution. Anatole, as half-quechua man, would keep track of the several attempts of rebellion in what was formerly the Inca Suyus and from Spanish colonies in general.

My decision to quote him was based on having better access to account of his and Tupac Amaru II’s lives. However, Anatole predates the latter for a couple of decades, and he would be well into his middle age or older for his rebellion and execution.

(2) The conversation between Milenko, the Sailor he reduced to tears and Anatole translates to:

[Milenko] “Think about it. Let them go, you already have your freedom, why do you want ours as well?”

“Shut up! Shut up or I’ll go get the Admiral and he’ll know what to do with you!”

[Milenko] “Let them go”

“Shut up, son of a--”

[Anatole] “Talk to him like that once more and I’ll blow your brains out”

Milan here is speaking Ladino.

(3) “Inti, mana chaniyuq kaqtinqa manan kaypichu kayman”: “I wouldn’t be here if it wasn’t important”

(4) “Moram mu reći da ga volim.”: “But I have to tell him that I love him”; while Anatole here is speaking Croatian, I am pretty sure most languages in the yugoslav balkans were not standarised yet, but I’m not entirely sure.

#my writing#jules' originals#aelius anatole#tamryn olenev#milenko#zelda oleneva#the olenevs#tamnana#a worship song of old#--> that'll be the tag for this piece

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

AERIALS

Even in the depths of hell and purgatory, they found something they were missing...in each other

(these two make me cry SO MUCH)

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

#mine#art tag#oc tag#milenko#original character#oc#digital art#art#artists on tumblr#furry#furry art#anthro#icp#insane clown posse#the great milenko#<- tags bc my sona is based off of icp milenko#side note happy birthday shaggy 2 dope

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

a dump of drawings of my OCs. if anyone wants to ask about them that's cool

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

hi bweirdoctober day 10 bc yeah. the little guy at the bottom makes living shadows from the goop in his head and the four beings around him r silly shadows. teehee

0 notes

Text

my really really good regretevator fanart (trust)

#these took at most 4 minutes#i know colors arent right but idgaf i do what i want#regretevator#unpleasant gradient#unpleasant regretevator#milenkos handicraft#<- sure.why not . peggle make phone calls

390 notes

·

View notes

Text

psychopathic records 🌚🎟

The Great Garfield Milenko

#insaneclownposse#420buds#the great milenko#woop woop#juggalo#icp#violent j#the duke#shaggy 2 dope#psychopathic records#garfieldpathic records

154 notes

·

View notes

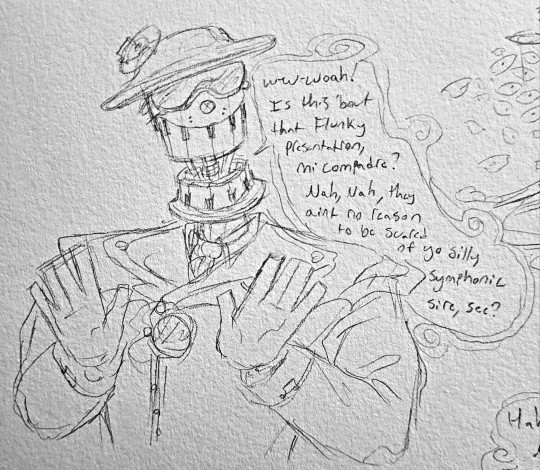

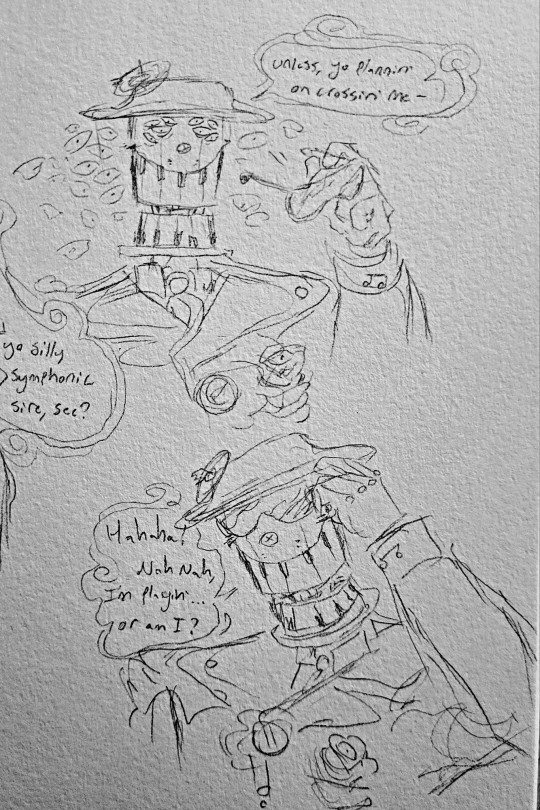

Note

OH BOY Dave sure can! Do THAT!

Was that presentation a one time thing or does he do that for kicks

Translation: SHOULD I BE SCARED OF HIM

Itsa one time thang, babe, dontchu worry 'bout it, aight? ~

Unless you's plannin on crossin' me- hahaha! Just playin', or am I?

#Dave only gave the presentation as an example of what happens to slimy snitches and double crossers#as long as you don't have any plans on crossing him or anyone he cares about you'll be fine x3#Dave's a chill dude when he ain't upset#he enjoys playing around; he's gotten more into fun times than messy ones since he's been hanging around toons and cogs#he's a creative cool cat you can trust him#ttcc#toontown corporate clash#toontown: corporate clash#imagionary rambles#ttcc au#dave brubot#major player#sorry if the art seems a bit rushed I needed to leave to feed and hang out with our tiny kitty bootsey#also besides; he's got his Hollywoods to calm him down before anything like the Flunky situation happens (not presentation style)#only two people his Hollywoods can't calm him down about me thinks are Saul and Fonz Milenko#they have a knack for uhm;; making him unreasonably upset;;

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

Stupid ass cowboy. featuring @detectivedog 's character

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

As They Covered The Sun With Swords They Had Bloodied, I Found Your Eyes Like A Worship Song of Old (Part 2)

A Tamnana centric spin-off to @ilyamatic's pirate au. Tamryn & the Olenevs belong to @valhallanrose.

You can find Part 1 here.

Series Summary: 16k words. Set during the first decades of the XVIII century, Aelius Anatole, or Inti Ankuwilla, as history might or might not remember him, meets a certain Tamryn Olenev when his family relocates from Poland to Venice. In meeting each other and falling for each other, the two of them will discover a kingdom of their own, where they can figure out what it is to exist despite all odds telling you not to.

Part 2: 6k words. After sharing a furtive kiss on a deserted alleyway in Venice, Anatole’s job catches up to them. With the promise of returning, Anatole sets off to the Caribbean and upon his return, he decides to face Tamryn’s parents before confessing his feelings to him. Meanwhile, Tamryn frets, prays and finds a strange form on solidarity in Milenko.

Content warnings: Minors DNI. This is a piece of historical fiction set in the early XVIII century, during the golden age of piracy. As such it may contain depictions, allusions and episodes of racism towards black and indigenous peoples, anti-semitism, islamophobia, and LGBTQ people, as well as legitimate aspects of colonial violence.

Footnotes can be found at the end of the piece if applicable. Check part 1 for the main references and background research used for this piece.

Late at night, Tamryn had been going over the same detail of his project over, and over again.

“Alright honey, I think it’s time for you to go to bed,” Evalina said.

Tamryn kept going over his project.

“Tamryn.”

His mother called his name again: “Tamryn.”

Only when she gently shook his shoulder, he realised she was talking to him.

Tamryn grew more and more distracted as days passed. Half agony, half hope, altogether dreading Anatole might regret what he did. He knew he had held his hand, he could still hear him promising he would come back but that wasn’t enough to calm his fears, especially when the fear of him changing his mind about him hid a fear much, much worse: that Anatole might not come back.

Tamryn hadn’t told his family what had happened between him and Anatole yet. Part of him wanted to, longing the familiar feeling of crying to his parents (as he had the honour to have good parents who understood him) and them comforting him about it. He could almost hear their voices telling him it would be just fine, he just had to be patient. For his own reasons he had opted not to say a thing yet, at least not to them.

His gut twisted at the idea it might end up in nothing, having a kiss under the golden light of the early evening to haunt him for the rest of his life. Tamryn didn’t know if he could forget that kiss, let alone the man who delivered it.

To no avail, he wondered often what Anatole must be doing. News of him was scarce. The Olenevs didn’t know a lot of details about what the Cassano did exactly. A House of accountants, some public servants, some scholars, musicians, artists, people of science, printers; at least on the outside. Eccentric as they were, they were good people. They also knew that was not all there was to them.

They helped people they knew as much, that’s how they have come to know them: another family that needed to make haste to leave Kraków, also for their own security and wellbeing, had been helped by the Cassano before. They knew their methods weren’t particularly straightforward, nor orthodox, but they got things done. Tamryn didn’t doubt Anatole was helping people, but ignorance wasn’t bliss, it was a torment.

The Cassano were also extremely private. During the five months Anatole was away, Tamryn learnt it was less due to mistrust (even if that was a considerable element) and more due to protection of their clients, closest friends, associates and collaborators.

Some of their clients were easy to locate and identify. The Cassano ran their business and lent their service with a public facade of acceptability and exceptional skill at plausible deniability. Plenty of people required help keeping account of their affairs for which they felt professional help was better than house servants.

Yet, Tamryn and his family had learnt that their most important clients had, for all effects and purposes, no names: they kept their identities with an iron grip. Even Anatole’s father, who liked to bounce ideas back and forth with Evalina on his own blueprints, never made explicit what they were for, if they were commissions or just silly drawings he indulged himself with. Nor did Anatole’s mother, Qhispi Sisa. She often talked about approaches to medicine with his father and Zelda, but now that Tamryn thought about it, she had never said what she used it for, nor who, beyond their usual house visits.

Tamryn had always missed Anatole when he was away, but at least the other times there had been letters. On this occasion there was none. Not even a note. He had tried to ask Amparo one day, when she came to see Zelda, only to be met with a gentle refusal to answer questions about her cousin, which differed from Amparo’s purposeful reluctance to explain herself.

Milenko was no different. Tamryn knew him and Anatole had been abroad together more than once during these last two years, so perhaps he would spare details about Anatole’s business. It wasn’t that Tamryn didn’t respect his privacy, it wasn’t that he didn’t understand Anatole not giving him information yet was a way to keep him safe (the thought that Anatole was taking care of him, no matter the distance, made him feel dizzy), but he just wanted something to hold onto. Some indication that he might be alright.

When he mustered the courage to ask him, Milenko knew what Tamryn would say before he even said it. “You’re in love. Nothing I say will ease your heart, Tamryn. You will worry anyway.”

“But you’ve been with him, while working.”

“Nothing that I say about myself in that regard will ease your heart either. Let it float away in the water. I like to think it carries my prayers so he is safe. There is life in water, Yhwh is the water.

“I know what it’s like when the heart misses the name spoken for it,” Milenko paused, taking just a little pity on him. He sighed. “Alright, it’s not news, precisely, but are you familiar with Rabbi Al-Harizi?”

“I’m afraid not.”

“Suspected as much,” Milenko said with warmth and an audible smile. “Part of my family lived in Spain before we were driven away from it. My nono’s family went there all the way from Aksum and Ethiopia; but mi vava’s family was from the peninsula, but you know what happened there. As it may, Al-Harizi could have some verses which you might appreciate. Would you like to borrow the book so someone else might read it for you?”

“I don’t mind if you do”

Milenko thanked him, and read:

If the son of ‘Amram had seen the face of my beloved, his ringlets, and his gloriously beautiful face blushing whilst imbibing alcohol, he would not have written in his Torah, “…and with a man”(1)

Tamryn would feel his face heat up. “I don’t think that helps. At all.”

Milenko took his hands in his, laughing as he squeezed them. “Be thankful I’m not pulling out The Conference of Birds or any Attar at all.”

“You’re worse than Amparo.”

“Believe me I am not, but What do all seek so earnestly? 'Tis Love. / What do they whisper to each other? Love. / Love is the subject of their inmost thoughts. / In Love no longer "thou" and "I" exist, / For Self has passed away in the Beloved!” (2)

All he could do for Anatole was to include him in his prayers. So Tamryn prayed for him, for his safe return, for more time. That Anatole may come back and kiss him again, or if not, at least that they could talk about it. Every time he said his name Tamryn felt the ghost of Anatole’s lips against his own. He hoped that too was a prayer. A prayer crowned with the sentiment that anything was worth it if it was for love, like his father said.

He should’ve expected Zelda noticing the way he muttered Anatole’s name between his prayers.

“That’s the third time you mention him. Did something happen? You look more lost than usual even since he left.”

“Hey.”

“I know you care about him, I just want to make sure you’re alright, and you’re not keeping anything inside that dumb big heart of yours, when it should be said out loud.”

His mouth became a waterfall of words. He had never been good at keeping things from his family, but he had always been notoriously bad at keeping them from Zelda.

* * *

Somewhere in the Atlantic ocean, Decimo Lemione’s body sunk and rotted in the water, his skull shattered with several pistol shots.

Anatole didn’t think he ought to be pitied. Yes, the ocean was big, but he wouldn’t be alone: he would have half his family to make him company.

* * *

Andrico was late. Of course he was late. Anatole had no time to waste. He needed to find the papers from the Casa de Contratación and get the fuck out of there. Decimo might have been dead, but that didn’t mean they couldn’t still be ambushed.

He heard someone approach the room.

“Oh, you’re not who I’m expecting.”

Anatole hated when things got violent for no reason (“It was just a little trespassing,” he muttered to himself after the second, third guard had come to check why the first, then second, person who had come to check on this room wasn’t returning). He hated it as much as he hated being inconvenienced. Only the fourth guard recognised him, but he was dealt with before he finished saying his name.

“Very rude, I am trying to keep a semblance of privacy—” a fifth person came in. “Oh, where the fuck is Andrico.”

He showed up 15 minutes after the fifth, and hopefully last guard had been dealt with, coming into the room with Jean-Marc, his Quartermaster, when Anatole was finding something to clean his sword, Dawn Piercer, with.

Anatole shot him a murderous look. “Glad to see the Solanaise II is sailing again, glad to see you’re in one piece. Far less glad to see you’re fucking late, El-Saieh. I’ve been waiting here for forty-five minutes.”

“Forty-five,” he repeated, hissing through his teeth.

“What are you doing here? I’m supposed to meet— No. You’re my accountant?”

“For someone who had the audacity to be three-quarters of an hour late, you have no right to be that irritated.” Anatole turned to Jean-Marc, walking over a dead body to hug him. “Marco! You, however, I am glad to see.”

Jean-Marc whistled. “I always knew you’d be one to watch out for.”

“Flattery will get you nowhere, but thank you.”

“So Zia Solange didn’t tell him?”

“She sure fucking didn’t.”

Anatole snorted, not even trying to hide how amused he was. Still, he was a professional, and the sooner he was done with this, the sooner he went over the Solanaise II’s accounts and routes, the sooner he could go back to Venice.

“Look, Andrico I know last time we saw each other we didn’t part on the best of terms, but this is different. You know it is. I am willing to set that aside for the sake of the contract, if that’s alright with you. My plan is to keep you alive for long enough, and I don’t think Solange asked for me to see your accounts only to piss you off.”

“Put what aside?” Drico asked, cocking his head to the side, in the same way Anatole’s dogs did. “I apologised for that! You’re the one who hasn’t accepted my apology for offering you friendship—”

Anatole sighed. “You’re worse than dealing with Christians.”

“Excuse me.”

Jean-Marc pinched the bridge of the nose. “Andrico, Anatole, the contract.”

“He called me worse than a Christian!”

“And I’m going to call you something even worse if you keep making me waste my time where we could be easily ambushed. Again.”

Andrico eyed the dead people, then Anatole. In many ways, before him stood someone he had known forever; in many ways, before him stood someone he had never met before. “You changed.”

“If you say so.”

“You’re impossible.”

“Andrico, the contract.”

He grabbed Anatole’s hand and shook it, despite feeling like somehow this would come back to bite him on the ass. “Deal.”

“Excellent! First of all, as your accountant,” Anatole said with something akin to murderous politeness, “next time you’re this late, or late in any unjustifiable manner whatsoever, I’ll feed you to the Mami Wata myself. Second of all, I found the papers from the Casa de Contratación and I have this,” Anatole showed them a signet ring. “It's only a matter of leaving it in the right place now and to get out of here. And thank all Gods-I-don’t-have-contempt-for that you brought Marco with you. I know you’re terrible with accounts when you’re in a sulky mood.”

“I’m not sulking.”

Jean-Marc groaned.

Once they were back at the Cassano’s safe-house, while Andrico was too busy proving him right by being taciturn and ill-tempered about his circumstances, Jean-Marc made conversation with Anatole. He told Anatole about his travels, and Anatole told him about his. The sooner he was done here, he had said, the quicker he could go back.

“So soon?”

“I left some, hm, business unfinished, and I want to be done with that before I come back in a more permanent fashion.”

“I see. With this business you mention, that is. Or alone?”

Anatole smiled at him and told him nothing.

* * *

It had been five months and a couple of weeks since he had last seen Tamryn, five months and a couple weeks since he had kissed him. Hadn’t it been because he wanted to wash his hair properly before he drove himself crazy and speak with his parents about what he was about to do, Anatole would’ve docked off in Venice and gone straight towards the Olenevs’ house.

His lips had haunted his every hour, as if the kiss itself had been as long as his exile. Yet, if the desire to see him again had pushed him forward, now that he was in the same place as him, his heart threatened to escape his chest through his mouth out of nerves alone.

What if he was angry at him for not writing? What if he had changed his mind? What if Evalina and Galen didn’t approve of him like this? Anatole thought they did, they both seemed to be both aware and protective of both Tamryn’s and Zelda’s choices in companions, as long as they were good for them.

It didn’t matter. All the reasons he had used to give himself hope and grit when he was away, all the beautiful things in nature, in his quarters, in the island, in people; all those beautiful details that he longed to show and tell Tamryn about were whisked away, as if they were trunks he had left on the ship and only now realised so.

The idea of being rejected made him physically ill. He knew his skin was intact, but he felt it crawl out of his body. Anatole hated this feeling. He hated how, despite feeling it all of his life, he still couldn’t get used to it, nor stop it, nor anticipate it. He had been learning, slowly, how to deal with it, but it made him overwhelmed and queasy.

The feeling itself had nothing to do with Tamryn and everything to do with Anatole’s mind. His mind has never known how to stop thinking, how to stop doing things, how to stop bouncing off the walls and digging his claws into certain things. For good or for evil.

He made a whining noise. His three dogs, three pomeranians he had “borrowed'' during one of his working seasons a couple of years ago named Duke, Zapa and Astrid, echoed it. His mapachitli tried to climb him, which Anatole had to stop by holding him in his arms, lest he damaged the fabric of his favourite suit.

Some of the people who had tried to capture Andrico (hired swords, privateers, bastards overall) when he was waiting for the latter had him in a miniscule pen. Before leaving, Anatole had released it, but it refused to go back to the wild, following Anatole instead. No matter how many times he tried to release it, the mapachitli came back.

The witty little thing even followed him to the ship. Anatole did the only thing he could think of: washing him, drying him, and taking care of it.

Now it was there, between his arms as Anatole was on the brink of a nervous breakdown. “I’m going to die.”

“No you’re not, Inti,” his father said as he kissed his brow.

“I am.”

“You are,” his mother said as she also gave him a kiss, “but not now. It will be alright, and we’ll be right behind you. Are you taking the dogs?”

“I think it’s more of a matter of the dogs not letting me get out of their sight.”

If it weren’t because his grit and determination were stronger than his nerves, he would’ve never made it out of the house. He looked at himself in the nearest mirror one last time: instead of his usual working attire of boots, fitted trousers with buttons to secure the waist-band, a shirt and perhaps a cravat that had been embroidered by his mother, he opted for one of his more formal suits. A fitted coat that reached his knees over a vest, a carefully crafted white shirt with lace details. While he still wore fitted trousers that reached his calves (mostly because he hated the feel of breeches’ clasps around his legs), he opted for dress shoes.

He pressed his coat against his skin, where the inner breast pocket should be. Right, he could do this.

He still wanted to vomit, but it was better to do things while his bones threatened to vibrate out of his flesh than not do them at all.

* * *

Evalina and Galen greeted Anatole in their foyer, exchanging pleasantries and asking him about his journey: if it had been good, if he was in good health, if the weather was agreeable for sea-travel and if his nondescript obligations had been alright.

As he did every time he stepped inside their home, Anatole left his cane —the one that had a stiletto rapier inside— by the door. The Olenevs already knew his dogs, the three of them trained enough to be decent guests and not to bark at Pomarańczowy, Evalina’s cat. The mapachitli had stayed back home. It was too small still to roam by the dogs, and in case of an emergency, Anatole needed to be able to manoeuvre a sword.

Sometimes he thought paranoia and overthinking would kill him, but they hadn’t yet. He supposed there was something auspicious about that.

Evalina and Galen had never seen him like this. He looked pale, despite clearly having acquired a slight tan that made his skin deeper and more freckles when oversea. He was shaking and spoke in circles, with a nervous verbosity they had never witnessed in him. They had heard him talk to his heart's content about things he was passionate about, but the way he spoke in the throes of academic passion was not the way he was speaking himself into a spiral now.

“If you came for Tamryn, I’m afraid he’s not home, but you’re always welcome to wait with us.”

“It’s not Tamryn who I want to see,” he said, fidgeting with his own hands. “I mean I do, I just mean right now, as in right-now-immediately.” He sat down, he sat up, he circled one of their sofas, he sat back in it by swinging his legs over the back of it. “I,” he paused, exhaling a nervous breath, “I need to speak to you both, as a matter of fact.”

Galen and Evalina exchanged a look between each other that, in itself, was an entire conversation, in the way only people who had been together for years could. Evalina offered him tea, hoping it will give him pause so he may speak freely, saying they will be happy to hear what he has to say.

Galen, however, offered him a light teasing smile. “Oh no,” he said, “I wonder what it is.”

Evalina whacked his arm, chastising him in Yiddish. Anatole didn’t speak the language very well yet, so he only understood something along the lines of “tea”, “offer”, and “tease him”.

In the time he was away he had prepared a speech in his head. He had even written it down, afraid his mind would consume itself with something else and he would forget it. He brought it out of one of his inner pockets, only to fold and unfold the parchment as he read none of its contents.

The only thing he managed to say before crying was “I”.

This is it, I have ruined all my chances for not being able to be better, as I know I ought to be, he thought, forgetting his hosts felt nothing but kindness for him. How could they not when he was so caring of their son.

Galen brought tea, which Anatole tried to drink but one of his dogs had made it to his lap.

“No, Astrid, get down.”

Impervious to her human, she tried to lick his tears.

“We’ve never asked, what kind of dogs are they?” Galen asked, offering him a reassuring smile, hoping speaking about something else would help him calm his nerves.

Anatole managed to wrangle Astrid down, but now he couldn’t stand up as all three of his dogs decided to perch themselves against his legs, trying to comfort him. He appreciated the change of topic as he, shakily, took the cup of tea.

“We know you only like spiced tea.”

“Thank you,” he sniffled. “I’m sorry. They’re pomeranians.”

Evalina and Galen both raised a curious, alert eyebrow. “You mean Polish spitzes? Those Pomeranians?”

“Yes.”

“How did you even manage to get a hand on three of them?”

“If I want to be completely honest, I stole them,” he laughed. Before his nerves could undermine him any further, he stopped himself from thinking the watery chuckle sounded pathetic. He was trying his best. He wasn’t pathetic. He was brave and strong, and he was around people whom he trusted.

With slow breaths, he calmed down somewhat and took a tiny sip of tea. “In truth, I don’t think certain types of people deserve good things… but I didn’t come here to talk about my job, or my political opinions, at least not just yet.”

At the same time as Galen told him he could take his time, Antole said: “I’m in love with Tamryn.”

Silence fell on the room.

“So tell him that?” Evalina said, tentatively. Anatole stared at her as if she had begun speaking in tongues.

“That’s not the point, though. I mean, I do plan to ask him to m—, rather, I mean, tell him, if that’s okay with you. Please do let me finish before I ruin the impression you have of me again. I want to ask him but I refuse to ask him before I talk to the two of you, no matter if I cry or if my voice shakes. As long as you allow me the audience I need to speak to you before I do that.

“I don’t think there’s more important people in this world, to Tamryn, than his family and his community. Even if I didn’t know Tamryn as I do, I would know how important community is for you, not because it is also important for me and the likes of me, but because I see it in Milenko and Zia Aurora and her siblings. The Tesfaye are nothing without their community.

“My job is dangerous, my job involves travelling at sea back and forth. I will tell Tamryn, but you must know first: my family does a lot of things, but our most important guild is not the ones we make public, but those which we don’t speak of. We administrate and protect several pirate communities. These pirate communities actively sabotage Imperial ships. It matters not the empire: what matters is this. Justice.

“Conquistadores take African peoples from their land and lives, in vile kidnapping as if they didn’t deserve their freedom. They take our lands and exploit our people to die in mines like Minas Gerais and Potosí and Nueva España, like we were nothing but things to be crushed under their ambition and their cruelty. Things to be re-educated, when what they mean is ‘eliminated’.

“We refuse to let that stand. I refuse to let that stand. This is not something I will stop doing and you have to know it because I do not love Tamryn to leave him here while I have a life away from him. I want him to occupy every waking thought I have and share with him every waking hour. I want to live with him and love him as if he were my husband. I know you suspect I rather entertain men, and everything I have seen in you makes me think you also know it about Tamryn.

“Not only that but I can tell you respect it, that you even protect it, instead of pushing him into a union with a woman that would’ve made him unhappy or unfulfilled, not because there was something wrong with the woman in question but because he did not like women. If I could, were I allowed to exist and love as a man and to marry other men, I would’ve come here today to ask your son’s hand in marriage, hoping toI propose to him and that he said to me: ‘yes’.

“But,” his voice shook again, yet he kept on going forward, “I cannot. Not because of lack of wanting, not for lack of the most profound love I have ever felt for someone. But despite all my fears, nerves, overthinking or doubts, I am yet to find something I allow these people, who think they know anything about people like us when they do not, to rule over my life. So I ask, because I love him more than I have ever loved any other man, and I plan to love him from this day forward for as long as he has me, as long as he has me.

“I cannot swear or promise this on the same grounds of your faith in your God, not because it’s a problem to me, but because you see me as I am. I am a half Quechua man, and I please ask you to understand I want no religion to claim me, because the one which could’ve was taken from me when my mother was severed from her own people. Perhaps even before.

“But I will do whatever I must that I’m either allowed or obliged to do under it as long as it is custom, so I can show you I truly do love your son. I know a bit, but I also know you do things differently from my Milan, but I am willing to learn him, just as I know he is willing to learn me.

“I can offer him protection, and as long as I’m able nothing will be lacking if he wants it, and we will visit if he wishes to come with me, and I will do everything in my power to keep him safe, because if nothing else convinces you, please take my word when I say I would never forgive myself if something happened to him because of me.

“I do not want to deny myself the chance that he may love me as I love him, because I had been doing that ever since I met him, and I love him too much to hide it.”

Somewhere mid speech he had begun petting Zapa’s fur in self-soothing motions. Now that he had said his piece, he was still nervous but what was done was done: he had spoken truthfully, and few things were as important to him as his own word. Now he waited, moments seeming longer than they were as Galen and Evalina shared another of their knowing looks.

Without words, Evalina asked Galen if there was something he wanted to say. Without words, he indicated to her that she should speak first.

She sat beside him, gently ushering Anatole’s dogs so she wouldn’t step on them by accident. Just as gently he took his hands and just as gently she spoke: “It is said in the shtetl that Elohim calls out the name of the one a boy is meant to marry upon his birth, and that to find the one that he has willed for us is one of the greatest fulfillments of the divine will.

“It is a bond meant to endure forever, it is our joy, it is our completion when we find the one decreed for us by heaven. If Elohim has called you for our son, sweet boy, if you are the one to make him happiest in this world and the next, then we will not interfere - we will celebrate you loudest of all.”

He must be hearing things. He surely must become nervous enough for his mind to become delirious, surely that must be it. Yet, Evalina cupped his face and kissed his brow like she did with her own children. A dog barked, all dogs barked as Galen had to widen his steps because they insisted on walking between his legs.

Galen squeezed his shoulder affectionately. “But you should be telling our son. You are going to tell our son, right?”

Reality caught up with him. They were giving him their blessing to tell Tamryn what he felt for him. If smiles could dazzle and momentarily blind, like the sun the eyes after stepping out of a tunnel did, Anatole’s smile would’ve dazzled Evalina and Galen into seeing spots.

He tried to speak but all he could do was smile.

Evalina squeezed his hands. “I assume he will, won’t you darling? If you’re still undecided, I have more to say to convince you. I am very persuasive.”

“She is.”

“But if you don’t, we will need to have a conversation.”

Anatole frowned as he tried to think. “Wait, did he tell you something?”

Evalina and Galen exchanged curious looks. “Should he have told us something?”

Anatole’s cheeks lit up with a blush that felt alien on his cheeks. With a laugh, Tamryn’s parents said they didn’t need to know.

* * *

Anatole’s heart stopped with the sound of the door opening. It remained suspended when it closed, frantically starting to beat again when Tamryn’s voice came through the hallway. That he was home, that Zelda would come back later because she had made way to the Cassano’s house, that the commission they had gotten was delivered with no problem. That he even helped one of their neighbours with a faucet that wouldn’t work.

Evalina and Galen smiled at Anatole, then called out to their son: “We’re in the drawing room.”

Anatole stood up, being unable to wait a minute longer, but Evalina ushered him to do so, whispering to him that it’ll be a nice surprise. In the foyer, Tamryn shuffled with his things, peeling layers of clothing and who knew what else. To him, it was another day of arriving home after running errands.

Anatole’s dogs weren’t as patient as their owner, three sets of paws announcing their way through the hallway, excitedly greeting Tamryn who greeted them just the same, in the most adorable cooing voice Anatole had ever heard.

“Why are you three paying us a visit? Are Vlad and Sisa at home?”

He was expecting his parents to reply to him, but it was someone else’s voice that reached him. A voice that felt like a dream or a memory, a voice that came with footsteps that stopped after a couple steps.

“No, no yet,” Anatole said. “They will later, but for now it’s just me.”

A sharp breath came out of Tamryn. He had been lingering around the docks, trying to get news of ships, but he must have gotten his information wrong because the sailors there told him the weather wasn’t in the best condition from timely arrivals. Tamryn had always liked the sounds of the waves against the shore, the sounds of birds flying up high —free and unrestrained— and the sounds of people who worked there going on with their daily jobs; but he wanted to think maybe the wind would carry news of his Anatole.

Not directly, of course, he knew as much. Anatole had been a ghost in the docks, his purpose hidden from official records or unwanted questions, but ships came carrying produce and people from the west all the time. He wanted to think that the auspicious news he heard was about him. Now he was here, close enough that all Tamryn needed to do was walk towards him.

Tamryn tried not to cry. He was unsuccessful.

“I’m sorry I didn’t write. There was a,” Anatole came closer to him, “a lead on a potential capture on Andrico, my Client. I didn’t want a letter to accidentally end in the wrong hands. Not when,” he was close enough to reach out to him now, “not when I would never forgive myself if harm came to you because of me.”

“What, what does that mean?”

“That I’m in love with you and if that’s agreeable to you, for as long as you’ll have me, I want to, I’d like to—”

Anatole couldn’t finish his sentence. Tamryn reached for him, holding him between his arms in the warmest, safest embrace Anatole had ever experienced. He held onto him as if he might disappear at any moment, lifting him and spinning him around in the tight hallway of his parents house.

“All I have wanted is for you to come back safe, and you’re here, you’re here.”

In their spinning Tamryn hit the wall with his back, making him tumble. He didn’t let go of Anatole, who managed to keep himself somewhat upright by freeing one of his arms from Tamryn’s hold and frantically trying to reach the opposite wall.

“Solnishko, are you alright?”

With eyes closed, he buried his face in Tamryn’s chest. He never wanted to leave it.

“I’ve never been better.”

* * *

FOOTNOTES

(1) This is the source used for the translation here. Al-Harizi was an Andalusian jew and if there is one thing you can trust them with, is the gayass medieval poetry, everyone say thank you Rabbi Al-Harizi. One of the works referenced in part 1 (A Rainbow Thread) speaks more of him.

(2) Attar of Nishapur, "Intoxicated by the Wine of Love" as translated by Margaret Smith.

Because I am not really writing Milan if Attar of Nishapur does not make an appearance.

#my writing#a worship song of old#jules' originals#aelius anatole#tamryn olenev#tamnana#milenko#zelda oleneva#the olenevs#nana having dogs began as an inside joke of him making fun of europeans by stealing their stuff and now i cannot picture him without several#dogs and his pet raccoon

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

totally very original non-inspired object ocs that are NOT inspired by artists/bands/songs/albums i like ermmmmmm

#osc#object oc#tagging everything fuck it#frank zappa#lemon demon#spirit phone#pleasantries#tiny heart's core#nelward#insane clown posse#the great milenko#jack stauber#hilo#nate.art#i might make more whenever i feel like it#(also sadly they dont have names yet srry LOL)

366 notes

·

View notes

Text

#juggalo#goth makeup#icp art#juggalette#juggling#insane clown posse#im actually insane#nonbinary#bisexaul#clown boy#clown girl#clown moment#clown makeup#clown oc#shaggy 2 dope#violent j#great milenko#black and white#photography#photo edit#photoblog#Spotify

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

but what if i got buck naked. and then walked through the streets winking at freaks. and what if i also had a 2 liter stuck in my butt cheeks

#RAAAAGRSGSGSGRAGAAAAGGSGARAHHSG#gear diary#icp#i can’t fucking stop listening to great milenko. it’s like mana in my most dire time of need

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

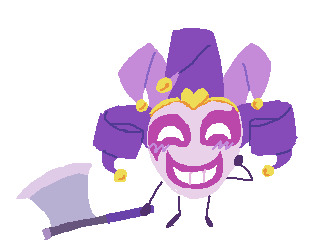

JUGGALOS AND JUGGALETS I BRING YOU THE GREAT MILENKO!!!

#Hokus pokus#clowns#insane clown posse#art#icp#juggalo#Juggalo art#shaggy 2 dope#Violent j#hatchet man#the great milenko#digital art#artist on tumblr#the skrunkly

269 notes

·

View notes

Text

Guys my 7 year old daughter is afraid to "whoop whoop" because she thinks people won't like her so can we reblog and give the signal for her so she knows she's not alone?

#icp#i love icp#insane clown posse#juggalo#juggalette#family#The Great Milenko#homies#whoop whoop#help a mom out#icp love#juggalo family#shaggy#violent Jay#wicked clowns

15 notes

·

View notes