#grignan

Text

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Karin Viard et Ana Girardot dans "Madame de Sévigné" biopic d'Isabelle Brocard - inspiré des échanges épistolaires entre Madame de Sévigné et sa fille Françoise de Grignan (XVIIe siècle) - mars 2024.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

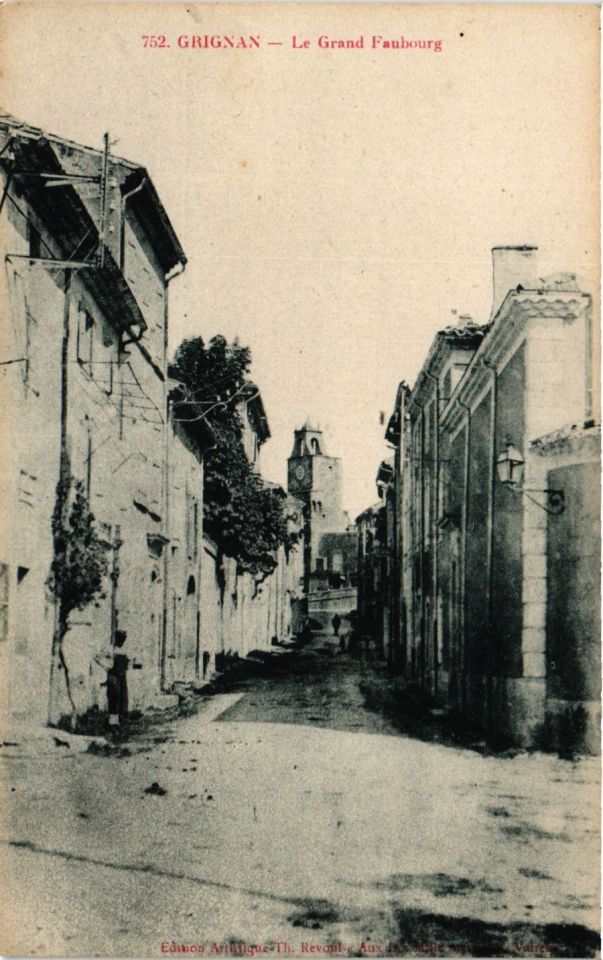

Château de Grignan, Provence region of France

French vintage postcard

#vintage#tarjeta#france#briefkaart#postcard#photography#region#postal#carte postale#sepia#provence#ephemera#chteau#historic#french#ansichtskarte#grignan#postkarte#château de grignan#postkaart#photo

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Je reprends mon projet de présenter la plupart de mes 52620 photos (oui, ça a encore augmenté !).

2006. Jean-Luc voulait retrouver Suzette dans le Vaucluse. On y va donc dans un automne doux et lumineux…

- les 3 premières : Avignon

- les 2 dernières : Grignan

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Mistral by Monty May (OBSERVE)

0 notes

Text

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

"In your life you have never seen the like"

We have many reasons to distrust what Louis Racine has said about his father. Only 6 when his father died, he could have had few personal memories of him, and no memories at all of his life as working playwright- which ended long before Louis was born. Being himself excessively pious and a convinced Jansenist, he was extremely touchy on the subject of his father's relationships with women, preferring to believe that his father "never was the slave of love", was never in love with Mlle Champmeslé, never wrote his tragedies "conforming to the style of declamation of his actress." Although it is easy to dismiss the sanctimonious Louis as a hagiographer, perhaps there is something to be learned from his insistence that Jean Racine felt obliged to give his actresses lessons in how to declaim his verses […]

According to Boileau, Racine also taught Mlle Du Parc the role of Andromaque and "had her repeat it like a pupil." Perhaps what these anecdotes reflect is Racine's desire to create a new style of tragic acting for plays that depended far more for their emotional affectivity on the appropriate inflection and melodious intonation of his carefully crafted verse than did the action-centered tragedies of Corneille and those who followed his prescription. The actor Jean Poisson supports this possibility when he notes that Mlle Champmeslé "sang a little" when she enchanted the court as Racine's heroines, but that "elsewhere she recited the Tragedies of the Celebrated M. de Corneille excellently & in a totally different manner."

If Racine took it upon himself to reform acting, this could have made him unpopular with some actors. Raymond Poisson may have had Racine in mind when he created his Poète basque in 1668, a few months after the great success of Andromaque. Among Poisson's provincial poetaster's ideas for improving the Hôtel de Bourgogne is the following:

I am going to read it [his play La Seigneuresse] to you presently,

And this reading will be like your musical score.

I will mark there all the tones and the mutations,

The facial expressions and the actions:

When I’m not speaking observe my face,

You will see me pass from love to fury,

Then, by marvelous art, in a surprising return,

I will pass from fury to love.

In brief, I am going to show the right way to satisfy,

And what a great actor must do to be great.

Don’t miss my least movement,

For even the least is worth applause.

Of course, Racine may not have been the only playwright who thought he was a better actor than the actors.

From the audience's point of view, there seems little doubt that Mlle Champmeslé, whether because of or in spite of Racine's tuition, was considered the finest actress of her day even by those, like Mme de Sévigné, who preferred Corneille's plays to Racine's. In January 1672 she wrote to her daughter that Mlle Champmeslé:

"seemed the most marvelous actress that I have ever seen. She surpasses la Des Œillets by the distance of a hundred leagues; and I, who am thought rather good on the stage, I am not worthy to light the candles when she appears. She is nearly ugly, and I am not astonished that my son was suffocated by her presence; but when she speaks, she is adorable."

She is speaking of Mlle Champmeslé’s performance as Atalide in Racine’s Bajazet. Giving the lie, however, to Louis Racine’s remark that the actress was never as good in other playwrights’ plays, Mme de ́Sévigné reserves her most effusive praise for Mlle Champmeslé's appearance in the title role in Thomas Corneille’s Ariane. The actress is “so extraordinary that in your life you have never seen the like; it is the actress one goes to see and not the play; I saw Ariane only for her: that play is insipid, the actors are damnable; but when Champmeslé enters, there’s a murmur; everyone is transported, and we weep at her despair.”

We also owe Mme de Sévigné for our reasonable assurance that Racine was in love with Mlle Champmeslé. Writing about Bajazet, which she liked, although not very much, she added: “Racine writes plays for la Champmeslé; it is not for the centuries to come. If ever he is no longer young, and ceases to be in love, it will not be the same thing.” If fact, she was absolutely right. He grew older, grew disenchanted with the theatre, lost Mlle Champmeslé to other lovers, and reinvented himself, but not before he had written for her Monime in Mithridate and the title roles in Iphigénie and Phèdre.

By “for her” I do not mean to suggest that Racine wrote these plays either because he was in love with her or because he wanted her to love him. Rather, I want to underscore once more the likelihood that because he knew what she could bring to a role, both as an artist and as a stage persona, he chose certain stories and developed them in certain ways. This might be especially true of Iphigénie and Phèdre.

From the beginning of her career as Racine's leading actress, Mlle Champmeslé was known for her ability fo bring an audience to tears. Forestier quotes a British diplomat, Francis Vernon, who wrote that "all the entertainment of the town are the two new plays, both of them called Bérénice… of which that of Racine seems to take much, and the ladies melt away at it and proclaim them hardhearted who do not cry, so much they are concerned for the unfortunate Bérénice." This ability was nowhere more famously employed than in Iphigénie […]

As Boileau later reminds his readers, it was with the help of the actress that Racine achieved his effects on the audience:

How well you know, Racine, with the help of an Actor,

How to move, astonish, delight a Spectator!

Never did Iphigénie sacrificed in Aulis,

Cause as many tears to flow in the assembled Greece,

As were at the hapy spectacle to our eyes unfolded

Caused to flow by la Champmeslé…

Even when Ariane was reprised at the Guénégaud in 1679, Donneau de Visé was moved to write in the Mercure Galant that "Mademoiselle Champmeslé, that inimitable actress who haas transferred to the Faubourg Saint-Germain troupe, on several occasions drew tears from many of her spectators."

Virginia Scott- Women on the Stage in Early Modern France: 1540-1750.

#xvii#virginia scott#women on the stage in early modern france#jean racine#louis racine#la champmeslé#nicolas boileau#madame de sévigné#madame de grignan#pierre corneille#thomas corneille#francis vernon#donneau de visé

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Romtik

1.

Römischer als Rom: die Provence. In Barmen sieht man noch mehr vom Flair westdeutscher Fußgängerzonen der sog. Nachkriegszeit, weil der beste Konservator immer noch diejenige Konjunktur ist, die entweder ausbleibt oder an einem Ort vorbeizieht und ihn verschont. Vielleicht ist deswegen die Provence römischer als Rom. Das Chateau Grignan ist dabei eine geradezu irre gradlinige Verkörperung dessen, was Panofsky im Plural die Renaissancen genannt hat. Nicht nur, dass die Schlossterrasse das Dach der gigantischen 'Dorfkirche' ist. Während wie im Keller die Leute an den Hostien knabbern, kann man oben im Freien gut frühstücken. Von dort hat man auch über ungefähr 20 km einen unverbauten Blick auf den Mont Ventoux. Dieser Blick fasst nichts, was nicht älter als 500 Jahre ist. Nur die dem Blick erahnbaren Bauten oben am Mont Ventoux erinnern daran, dass nach 1500 noch etwas passierte und die Geschichte weiter ging. Das ist nur der Blick nach Süden, blickt man Norden, Richtung Lyon, spült die Moderne gleich ins Auge. Das Chateau wächst aus dem Felsen, das Dorf wie Pilze am Stammsitz der gründlich und technisch, künstlich veredelten Leute im Schloss. Nackte Wände, an denen Bilderfahrzeuge hängen, am schönsten im Salon der Madame von, denn da hängen die Bilder des Schreibzeugs, der Tafeln, Stühle und Stifte, der Tabellen, Notizblöcke, Geschäftsbücher und einer Uhr. Das Pendulum ist ein Polobjekt, neben dem Globus und der Tabelle (einer minderen Tafel) ist sie das Polobjekt der Verwaltung schlechthin, sie ermöglicht es, eine Bewegung zu operationalisieren, in der Kehren, Kippen oder Wenden vorkommen und die als Zeit messbar ist. Die Zeit geht mit den Leuten durch und damit wie sie und ihre Dinge von hier nach da, immer vorübergehend strömend.

2.

Warburgs Polarforschung und seine Rechtswissenschaft zapfen alle möglichen Wissenschaften an, um über den Strom der Leute und Dinge, besser gesagt den Leutenstrom und Dingenstrom mehr wissen und sagen zu können, auch die Naturwissenschaften des 19. und 20. Jahrhunderts, auch die Wissenschaften von der Energie, der Elektrizität und der Ladungen. Das ist und bleibt aber bei Warburg eine epistemologische Praxis aus dem Geist einer niederen Kanzleikultur, dabei desjenigen Wechselgeschäftes, das so recht in Webers Vorstellung von Bürokratie nicht repräsentiert scheint. Das ist eine unbeständige Verwaltung, die Warburg mit seiner von ihm sog. Gestellschieberei auf eine Weise fortführt, dass man sagen kann, dass sei nachahmend und vorbildlich in einem. Das Strömen ist der Gegenstand dieser Praxis, die Ladung, das Pendeln, das Kehren, das Polarisieren, der Schlängeln, das Schlingen, der Verzehren und Verkehren. Was Gegenstand einer Wissenschaft ist, ist immer auch übersetzt, ist immer schon reproduziert und ein Ersatz: auch die Energie, auch der Strom, auch der Mensch und das Gesetz. Kein Wunder, dass Warburg ein hohen Berufsbezeichnungsverbrauch hat.

0 notes

Text

Fables et fabulistes : Pauline de Grignan ( fille de la comtesse de Sévigné)- La Pescheuse (1676-1737 )

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Canapé sur tuiles

Fenêtre sur ciel

Tableau naturel

Où ruisselle mon huile

0 notes

Text

The Correspondence Festivale of Grignan 2015

(Festival de la correspondance de Grignan/fb)

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Street scene in Grignan, Provence region of southern France

French vintage postcard

#street#historic#photo#briefkaart#vintage#region#provence#southern#sepia#grignan#photography#carte postale#scene#postcard#postkarte#france#postal#tarjeta#ansichtskarte#french#old#ephemera#postkaart

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Nouveau retour à mon projet de présenter la plupart de mes 55500 photos (et des brouettes). Plus trop loin du présent….

2016. Marseille en octobre,

- les 3 premières : vers la place Halle Delacroix

- Rue Paradis

- le Temple Protestant de la rue Grignan (Christine y est en terre connue !)

#souvenirs#marseille#marché#couleur#vitrail#vitraux#piments#rue paradis#classique#christine#temple protestant#croix huguenote#rue grignan#noaililes

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Thomas Jefferson in the nineteenth century wrote to his daughter that childbirth was "no more than a jog of the elbow," when his wife had died in childbed, as this daughter was to do two months later. Much more honest was the anxiety evinced by Madame de Sévigné, when her beloved only daughter suffered three pregnancies in the first two years of her marriage, including a severe miscarriage. In a furious letter she warned her son-in-law that "the beauty, the health, the piety and the life of the woman you love can all be destroyed by frequent occurrences of the pain you make her suffer" threatening him, "I shall take your wife from you! Do you imagine I gave her to you so that you might kill her?" Françoise survived this pregnancy, but her mother's fears were not at an end. Immediately after the delivery she dashed off a hasty warning not to rely on breast-feeding to prevent conception:

"if after your periods start again, you as much afarink of making love with M. de Grignan, you may consider yourself already pregnant, and if one of your midwives tells you differently, then your husband has bribed her!"

The position of the husband in this all-too-common situation, caught between the options of lethally selfish sensualist or reluctant celibate, was not a happy one. He would, however, survive his sex life: very many women did not. And as the modern age with its much-vaunted progress and prosperity broke about the ears of women in the West, they had the disconcerting experience of discovering that childbirth became worse, not better; for in one of the decisive power struggles that were to touch all women's lives, men finally won their long fight to take over the management of women in labor. Male attacks on women healers were nothing new —one facet of the witch hunts had been the determination of university-trained male physicians to eliminate the female opposition. But with the advent of drugs, obstetrical forceps, anesthesia and formal medical training, male practitioners were finally able to usurp women's age-old role as birth attendant and present themselves as the chief accoucheur.

Armed with the authority of the expert, the new men had no difficulty putting down the old women, even when they were horribly in the wrong. On his own admission "the great William Smellie," the mold-breaking "Master of British midwifery" when learning his trade once slashed a baby's umbilical cord so clumsily that the child almost bled to death. Smellie informed the suspicious midwife, whom his arrival had displaced, that this was a revolutionary new technique designed to prevent convulsions in the newly born. Privately, though, as he later disclosed, he was never so terrified in all his life.

With the advent of chloroform and disinfectant in the West, medical science began at last to make headway against its own darkest prejudices that the suffering and death of women in childbirth were no more than a "necessary evil" to be seen "even as a blessing of the Gospel," as one leading British gynecologist wrote in 1848. Elsewhere, though, it seemed that nothing could dislodge the fatalistic attitude toward the loss of female life, nor change the habits and customs that promoted those deaths. From India, a British woman surgeon, Dr. Vaughan, sent this despairing report in the last days of the Raj:

On the floor is the woman. With her are one or two dirty old women, their hands begrimed with dirt, their heads alive with vermin... the patient has been in labor for three days, and they cannot get the child out. On inspection, we find the vulva swollen and torn. They tell us, yes, it is a bad case, and they have had to use both feet and hands in their efforts to deliver her... Chloroform is given, and the child extracted with forceps. We are sure to find holly-hock roots which have been pushed up inside the mother, sometimes string and a dirty rag containing quince seeds in the uterus itself... Do not think it is only the poor who suffer like this. I can show you the homes of many Indian men with university degrees whose wives are confined on filthy rags and attended by these bazaar dhais.

With great clarity, Vaughan saw that the root cause of this suffering, infection and death lay not with the dhais who ministered to the women, but in the attitudes of the husbands.”

-Rosalind Miles; Who Cooked The Last Supper? The Women’s History of the World

#who cooked the last supper#reproductive rights#pregnancy#herstory#womens history#womens rights#radblr#radfem#radical feminism#radical feminist safe#radical feminists do interact#radical feminists do touch#radical feminists please touch#feminism#feminist literature#radical feminists please interact#radical feminist community#radical feminist literature#radical feminst#radical feminist theory

4 notes

·

View notes