#four lions

Text

Restaurant aesthetics 10/10 🪵

#restaurant#restomod#current mood#forest food#food plate#my aestetic#comfy aesthetic#aesteticphotography#old house#old aesthetic#cozyplaces#cozy aesthetic#cozyvibes#cozy#bar#place to visit#sremski karlovci#4 lava#four lions#serbiatourism#serbian food#serbia

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

help my teacher put on Four Lions in politics class and I'd forgotten how close Ballisters design is to Literally Riz Ahmed but with Ballisters eye scar.

#nimona#ish#also while i was talking about Kayvan Novak he asked if id seen WWDITS#which YES i have but this teachers such a boring asshole#who i DO NOT want to have interests in common with#Also was jumpscared by Adeel Akhter#like omg Wilson Wilson#i know everyone else ever probably watched four lions first but i genuinely didnt even know it existed before now#four lions

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

OMG THAST KAYVAN NOVAK !! WAJ I MISSED U SO MUCH <3

#four lions#what we do in the shadows#pleasant surprise seeing a few actors i know in wwdits#matt berry and kayvan novak so far

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

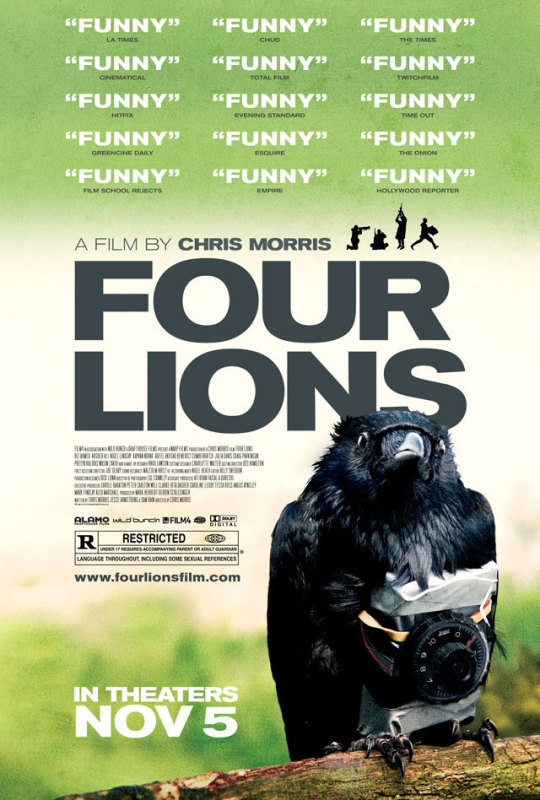

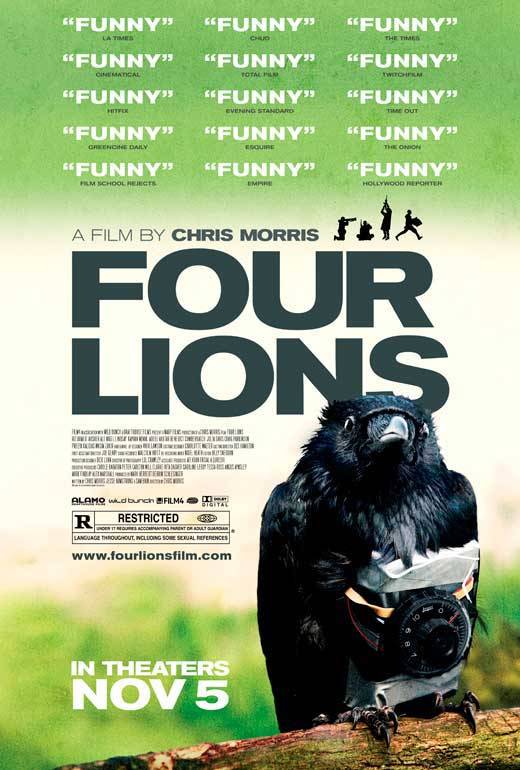

Four Lions (2010)

What do you think is strapped on that crow?

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

I just watched Four Lions. Hilarious. I wish Chris Morris had more of a following on Tumblr.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

i definitely dont talk enough about the immense love i have for riz ahmed!! this man is just so- <3

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#chris morris#four lions#movie poster#movie posters#film#films#riz ahmed#nigel lindsay#julia davis#movies#adeel akhtar#arsher ali

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Four Lions (2010)

This is a new fave movie!!!

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

#Marcus Garvey#Jamaica#politics#activist#actor#mosiah#same name#UNIA#ONH#Eurovision#four lions#broadchurch#political#activism#Stella

1 note

·

View note

Text

youtube

Four Lions (2010)

A jihad satire following a group of homegrown terrorist jihadis from Sheffield, South Yorkshire, England, staring Riz Ahmed, Kayvan Novak, Nigel Lindsay, Arsher Ali and Adeel Akhtar.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

riz ahmed babe

#riz ahmed#i love this man#sound of metal#trishna#four lions#girls#Mogul Mowgli#oscars#give me a mic

3 notes

·

View notes

Link

Now that the chair Rabbi Charlie Cytron-Walker threw at his hostage-taker is headed to the Weitzman National Museum of American Jewish History in Philadelphia, I hope it isn’t too rude to note that numerous all-too-quickly-memory-holed questions remain about January’s crisis at Congregation Beth Israel in Colleyville, Texas. Those unknowns all suggest the type of farce that ensues when supposedly crackerjack national spy agencies get tangled up in the comic-book plots of inept jihadis, who most likely would never have made it out their own basements if the aforementioned security agents hadn’t given them that final and just-as-often initial boost they needed to live out their dreams. Given the complexities involved, it should come as no surprise that this kind of elaborately witting-unwitting collusion can sometimes go horribly wrong. On one side of the equation are people who seem to be barely able to master the basics of what most of us understand to be everyday reality—perfect marks for those who believe themselves to be the protectors of that reality, a role they pursue with light oversight and fewer legal limits on their tactics and behavior than citizens in a democracy might hope for.

…

There is nothing but loose circumstantial evidence tying the Colleyville siege to any level of U.S. law enforcement, but the evidence is always only circumstantial until the truth comes out. A right-wing militant plot to kidnap Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer, one of the most politically salient of recent American terror cases, turned out to have been hatched by FBI agents and informants, greatly complicating the bureau’s investigation of an incident that broke just weeks before the 2020 election. Earlier this month, prosecutions against four of the alleged plotters resulted in two acquittals and two hung juries. There’s a long post-9/11 tradition of American sting operations carried to self-defeating extremes, ranging from the Liberty City Seven to the Fort Dix Five, to other fiascos with less memorable nicknames.

…

Why does the FBI spend its time and resources playing these silly yet socially destructive games? Who knows. I’m not a spy, but perhaps spies have bills to pay, just like I do. And perhaps, as the English satirist and filmmaker Christopher Morris noted in a 2019 interview with Britain’s Channel 4, “The FBI have stumbled across the fact that it’s harder to find a real terrorist than it is to make up your own.”

Morris wrote and directed the greatest comedy ever made about FBI counterterror entrapment, The Day Shall Come, a film so bleak and withering that barely anyone in America saw it. Perhaps in mid-2019, with Trump still in office and the fizzled Mueller report a bitter recent memory, the time simply wasn’t right for a foreign independent film that made the FBI look like naked buffoons. Or maybe the movie, which is about a bureau agent who uses a fake ISIS sheikh to manipulate a harmless Black nationalist into purchasing fake uranium from fake Nazis, was too dark and too tonally muddled to generate the word-of-mouth interest that a limited release needs in order to break through to a larger audience. On the other hand, 2010’s Four Lions, Morris’ previous film, is rightly considered a modern classic—and it’s a comedy about a successful jihadist attack on the London Marathon.

It’s possible The Day Shall Come went unseen, with U.S. box office totals barely touching five figures, because it pressed on a rawer and more complicated source of anxiety than Four Lions, at least for American audiences. Riz Ahmed’s Omar, the jihadi protagonist of Four Lions, is a Raskolnikov-like amoral idealist caught between his own inner evils and the possibility of some ultimately redemptive acceptance of the cosmic order. Four Lions, with its reassuringly distant English accents and setting, probed the comedic absurdity of believing you’re ideologically obligated to commit mass murder.

Morris’ second film, set in the U.S., was instead about the possibility that the American national reality is being manufactured for us by idiots, a likelihood that is too terrifyingly real and immediate to serve as a basis for mass entertainment. Kendra Glack, the patriotic, well-meaning, and not entirely unconflicted FBI agent played by Anna Kendrick in The Day Shall Come, is someone we don’t really understand and would rather not even think about, someone whose existence in the real world might raise disquieting questions about what kind of country and society and world we really live in.

…

A comedy about jihadist terrorism was a natural next step for a humorist who’d played fast and loose with jokes about physical attacks on the queen and who once produced a wildly controversial half-hour Brass Eye special lampooning British neuroses related to pedophilia—which is as far as the envelope could go on mid-’90s U.K. television, and probably much further than it could go now. Still, if Morris cared only about provocation, his career would look a lot more like Sacha Baron Cohen’s, filled with disposable political comedy meant to mock the anonymous and flatter the powerful. Morris is Cohen’s tonal, moral and aesthetic opposite: He’s never made anything that’s forgettable, and his contempt for the powerful and sympathy for the overlooked never leads him to caricature or ridicule anyone.

When Four Lions came out in 2010, few noticed the possible thematic linkages between Morris’ fascination with the news media’s construction of reality and his project of understanding the worldview of religious extremists through satire. In The Day Today and Brass Eye, he had brutally satirized an elite-level epistemological system that had meaninglessness at its core and that had scrambled the rest of society’s experience of the so-called real world. But what about the little guy who had never gotten the memo, and who still insisted on living as nonsense-free a life as possible? What did he look like in the vacuous, desiccated 2010s? What might he want?

Where Four Lions furnished one especially chilling answer, it really furnished five. The shambolically extreme Azzam al-Britani is a convert who thinks he’s a world-historical figure: “If I don’t go with you to training camp in Pakistan, Islam’s finished,” he proclaims. Faisal is driven to terrorism by sexual rejection, hinting that darkly male urges lurk behind otherwise inexplicable outbursts of violence, as they have for all of human history. Hassan is a poseur campus radical titillated by extremes but unsold on jihad as such. Waj is too daft to really know what he wants. But he idolizes his cousin Omar, a mall security guard and terror cell leader who dreams of dying with a smile and on his face and who perhaps believes he’s fulfilling the legacy of another cousin who met a heroic end defending a mosque in Bosnia.

…

It isn’t until toward the end of the film, as the authorities close in on our anti-heroes, that we see the recurrence of Day Today-type reality-building from above—except this time it’s being undertaken by gun-wielding agents of the state rather than hapless newsmen. In perhaps the darkest joke of the entire movie, and maybe the darkest funny joke in any movie, a pair of rooftop police snipers at the London Marathon are told by radio that one of the suspected bombers is in a bear costume. One of them immediately guns down a runner dressed as Chewbacca.

Is a wookie a bear? The two debate with sinister British dispassion and earnestness, immediately spinning an ex post facto justification for killing a faceless innocent while evincing zero remorse or horror at their actions. A lesser, more merciful satirist would have placed this back-and-forth before the fatal shot was fired, turning the snipers into deadly blunderers but leaving open the possibility for regret, perhaps even reform. Placed after the killing, the exchange makes an additional point about how even our own enlightened societies tend toward erasing their fatal mistakes from existence, indicating the ease with which nasty official acts eventually find their reasoning, however logically tortured and facially absurd. By the end of the movie, simple incompetence has already morphed into elaborate intentional dishonesty, as a British interrogator informs Omar’s pacifistic brother that for legal purposes, and because of the torture it’s implied he’s about to endure, he’s now on the sovereign territory of Egypt, despite being inside a shipping container inside of an air force hangar in England. There’s a tiny Egyptian flag on the inquisitor’s desk, making the lie true.

We meet another believer in The Day Shall Come: Moses Al Shabazz, Marchant Davis’ delusional Black separatist. Shabazz is an urban farmer raising a militia group that he believes will overthrow the white oppressors with toy crossbows and resurrected dinosaurs in a battle beginning on the film’s titular day of judgment.

Unlike the jihadists in Four Lions, however, Shabazz isn’t planning any specific atrocity. He preaches Black restraint and nonviolence right up until the dinosaurs arise. Falling into a rapidly escalating entrapment plot hatched on the fly by agent Glack, played by Anna Kendrick, Shabazz accepts money and guns from a fake ISIS leader—the bureau-sanctioned disguise of a potentially violent Syrian who Glack will deport back to his home country if he doesn’t cooperate with the FBI. The Syrian is introduced to Shabazz by a child porn enthusiast who the bureau is also blackmailing. As insane as these characters are, their equivalents, composed with even more extreme degrees of lunacy, are quite easy to find in the documentary aftermath of FBI entrapment operations, which gives the film a vertiginously human feel.

Shabazz, whose tiny sect is facing eviction from its modest compound in a gentrifying Miami slum, plans on pocketing the cash and burying the new ISIS guns in concrete. His extremism isn’t a danger to anyone, and the character reflects Morris’ belief that terrorism entrapment targets those who are naively idealistic and uncommonly credulous, traits that the truly dangerous usually don’t have. The FBI “preys on people who are on the fringe, who feel like they’re not normal,” Morris said in that 2019 Channel 4 interview.

…

By the time the FBI and the National Guard surround Shabazz and his followers at a doughnut shop, the thwarted fake purchase of fake ISIS uranium by fake Nazis has triggered a nuclear emergency that the panicked and ambivalent FBI agent who declares the state of emergency herself knows to be fake.

“So,” Glack asks her supervisor, “to stop a nuclear emergency I have to declare a nuclear emergency?” “Yes,” the more senior agent replies. “The logic only works if you say it slowly and keep the contradictory elements apart.”

From the beginning, the Shabazz case is stage-managed by people who, in a democracy, should be considered hilariously unfit to wield absolute power over the life and death of their fellow citizens. This disjuncture is where much of the movie’s humor comes from. “You’re gonna pitch me the next 9/11,” eye-rolls one bureau lawyer, knowing he’s about to be sold on the field office’s latest ridiculous sting idea. One especially dicey entrapment tactic will only work in the Fourth Federal Circuit Court of Virginia: “You have to fly ‘em there and rearrest ‘em when the land,” the lawyer frets. “Sure, whatever, perfect!” an agent responds.

Morris’ two feature films amount to a damningly familiar picture of life in the 21st century. In Morris’ world, belief in anything beyond a narrow band of quasi-official opinion is relegated to social outcasts and lonely misfits, many of whom are bonkers and some of whom are genuinely dangerous. Meanwhile, reality is contingent on the whims of powerful idiots who lie as easily as they breathe, and whose handiwork has left most of us unable to tell the difference between invention and truth.

…

Perhaps things aren’t as exaggeratedly terrible as The Day Shall Come makes them out to be, but there’s enough similarity between the world of the movie and the one we actually live in to validate any nagging unease. Colleyville might be another one of contemporary America’s many permanent mysteries, but as Morris’ films show, any skepticism we might have about an illogical and plainly evasive official accounting of events isn’t just the result of paranoia. At worst, our doubts spring from the dark outer reaches of the human and American condition. At best, they’re a revolt against numb acceptance of obvious, deadening nonsense.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

And there's the third and final review of the ones I've been putting off - Four Lions (2010).

#review#film reviews#letterboxd#satire#farce#dark comedy#channel 4#four lions#riz ahmed#kevin lindsay#benedict cumberbatch#british#extremism#film#rock out#rock on

0 notes