#dunmore proclamation

Text

Hannah-Nikole Jones and Gerald Horne may not be aware of this but:

One of the bigger whoppers in Gerald Horne's Counterrevolution of 1776, and the 1619 Project essay that takes it as anything but a work of hackery, is treating this as a cause of the Revolution. In reality it was the opening salvo of the war spreading to the South from New England. A deed taken after a war began does not, Hannah Nikole Jones and Gerald Horne's selective understanding of chronology and reality aside, cause the event it reacts to.

All the same Dunmore did hit the Southern colonies where it hurt and the result was that the Continental Army wound up the most integrated US force of arms until the Truman era.

#lightdancer comments on history#black history month#us history#american revolutionary war#dunmore proclamation#1619 project#the counterrevolution of 1776#this is one of the set of lies in the book that does have to be presented as one#if you read these books and come away with the impression that George III was John Brown then well....#that's a you problem

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Watching Turn again B). This time I'm on Season 1 Episode 6.

The implementation of Lord Dunmore's Proclamation is interesting. I wish the script made it more clear that this Proclaimation originated in Virginia but Setauket is adopting it as well. I find the sliver of a paternalistic view of Anna to be interesting, but I like it because, even though she is a main character, this is a valid character flaw to have that follows the ideology of the 18th-century. They did however gloss over it a little to make her more sympathetic.

Hewlett's response to her is also interesting. He definitely isn't an abolitionist either, but leaning more anti-slavery, influenced by his English background. He definitely harbors a British supremacy viewpoint, but because of not being raised in a place where slavery is the norm, is not completely brainwashed into a paternalistic view like Americans. I really like this point because it does show conflicting viewpoints, something that isn't explored too much in historical fiction I know of.

We are reading Heart of Darkness in my literature class, so it is interesting to see how a British perspective is essential in understanding the hierarchies of both colonial societies. The contrast of Hewlett from these late 19th-century colonizers in the novella is also interesting, and it really shows how much Social Darwinism hurt.

I find it interesting how everyone treats Robert Rogers and how he treats others. I did only a little research, but Robert Rogers was born in Massachusetts and lived in New England while growing up. TURN makes it seem like he was born in Scotland, but he was raised by Scots-Irish parents. I wish this was explained better.

My point is that all the British officers treat Robert Rogers as lesser. At first this seems that it is just because he is rustic and rough, but the fact that he was raised in the American colonies adds a whole new layer of meaning. He is also an outsider due to his place of origin, and this shows through his interactions with other characters. He seems to reject the norms of English culture, too. Seems to me like a "no lives matters" guy 😭.

I am just briefly glancing at Rogers' wikipedia page for a sense of his life. Bro really had some troubles. He was charged with treason against Britain and became an alcoholic around the revolution. It's honestly sad :(

This post is kinda incoherent. There is more to explain but my brain is too tired from today to explain it.

Abigail and Mary are such girlbosses I love them.

Poor Ensign Baker 😭

TL;DR: LORD DUNMORE?!?!??!?! Social Darwinism sucks. Robert Rogers is American.

1 note

·

View note

Text

لم تكن ماري تعلم أن سعيها من أجل الحرية والمساواة سيأخذها إلى أربع دول وثلاث قارات على مدار حياتها.

Mary Perth (1740 — after 1813)

Mary Perth (1740 — after 1813)

Mary Perth arrived in Freetown, Sierra Leone, in search of freedom and self-government after she left behind slavery in the Unites States and discrimination in Nova Scotia (Canada). Mary was one of thousands of other black settlers whose dreams of self-determination did not materialize in Freetown in their lifetime.

Yet, Mary’s life would have been very different if she had remained in the United States or Nova Scotia. In Freetown, Mary Perth was able to operate a business and vote, a privilege not extended to women in the United States until 1920. In Freetown’s legal system, Mary had the right to be judged by a jury of her peers, unlike her counterparts in North America. In addition, interracial marriages were legal, centuries before the United States Supreme Court declared such marriages legal in the mid-twentieth century. Little did Mary know that her quest for freedom and equality would take her to four countries and three continents over the course of her lifetime.

Born in 1740, Mary was enslaved by John Willoughby of Norfolk, Virginia. Willoughby’s wife gave Mary a copy of the New Testament. It is unknown how or when Mary learned to read, but it is possible that she read the New Testament to her fellow slaves during secret meetings in her Norfolk neighborhood.

In 1775, the thirteen North American colonies were on the verge of a war for independence from Britain. Virginia Governor Lord Dunmore ordered martial law and issued a proclamation offering freedom to those slaves willing to join the British cause—but only if their masters were rebels (American patriots). The Willoughbys were Tories, loyal to the British, therefore the offer of freedom to slaves did not apply to Mary and her daughter, Patience.

In early 1776, American forces mounted an attack on the British position in Norfolk. As Dunmore’s naval fleet began to retreat from the city, the Willoughby family and their slaves sought refuge aboard British ships. Dunmore’s naval fleet retreated north to Gwynn’s Island, where a severe smallpox epidemic spread throughout the encampment. After quarantine, Mary and Patience survived the scourge. The American Patriots’ relentless bombardment of the British encampment forced Dunmore’s naval fleet to retreat from Virginia and sail north to New York in the spring of 1776.

In New York, even though Mary was separated from the Willoughby family during the chaos of war, she legally remained a slave. For several years, Mary lived on Manhattan Island where she likely worked as a domestic laborer for the British Army. There she met and married Caesar Perth, who was from Norfolk, Virginia.

News arrived in New York in 1781 that the British surrendered in Yorktown, effectively ending the war. This event caused the Perth family to confront two new crises. The first crisis was the terms of the peace treaty; the British agreed to return fugitive slaves to the victorious Americans. The Perth family’s fears were relieved when British General Guy Carlton declared that all of the blacks who had joined the British before 1782 would be freed. The second crisis centered on the fact that Mary needed to find a means to evacuate New York before she was discovered by the Willoughby family or the authorities. Mary and Caesar were able to acquire certificates of freedom, which effectively served as passports to the northern British territory of Nova Scotia.

For the first time in their lives, they were legally free. On July 31, 1783, when the Perth family boarded the ship L’Abondance, Mary was pregnant with her second child, Susan. They arrived in Nova Scotia and settled in Birchtown.

Building a settlement in Birchtown meant confronting numerous obstacles. Acclimating to the blistering cold northern climate and finding land useful for farming was a challenge. The Perth family escaped neither discrimination nor the practice of slavery. Some of the white Tories brought their slaves with them to Nova Scotia. A hostile reception from the white population and government officials delayed or denied promises of land grants to black immigrants. Shortage of work and land created economic hardships and opportunities for white Nova Scotians to exploit the labor of the black immigrants.

Disappointed by broken promises and the hardships of life in Nova Scotia, the Perth family was attracted to another opportunity to seek a promised land. Representatives from the Sierra Leone Company promised a better life, land, education, self-government, equality with whites, and Christian missions in Africa. In January 1792, the Perth family and hundreds of others boarded the Sierra Leone Company fleet of ships as they sailed across the Atlantic to the settlement of Freetown, Sierra Leone, West Africa.

When the settlers arrived in March, they discovered the promise of a new settlement included risks. Enduring the dry and rainy seasons and suspicious reception of the indigenous African people was a challenge for the Nova Scotian settlers. On arrival, they were surprised to discover that the Sierra Leone Company’s board members reneged on many of their promises, including self-government. Preachers and others in leadership within the black community protested and petitioned the Sierra Leone Company to fulfill its original promises.

When land was allocated to the settlers, Caesar Perth built a two-story house and farm on Waters Street. Unfortunately, after establishing a home for his family, Caesar died. Saddened by the loss of her husband, Mary sold the farm and converted her home into a boarding house for travelers arriving in Freetown.

Without warning in 1794, a French fleet attacked and raided Freetown, forcing many settlers to take flight. After the French departed, the governor recognized Mary’s loyalty and heroic acts during the crisis. The governor offered Mary a paid position as the governor’s housekeeper, which required her to care for and teach African-born children in the governor’s residence. Later, Mary accepted the governor’s offer to travel with him to London as his housekeeper. Susan died in England, and six years after arriving in London, Mary returned to Nova Scotia alone. Mary Perth likely died after 1813.

#MARY PERTH#black history#BLACK#AFRICA#enslaved#HUMAN RIGHTS#USA#blacklivesmatter#black women#revolution#civil rights

1 note

·

View note

Text

At least they acknowledge we don’t know where America would be if it was not for the revolution.

At least they acknowledge we don’t know where America would be if it was not for the revolution. One contributing factor that allowed for independence was the fact that Great Britain could not replenish its troops fast enough. The advancement in technology might have allowed them to win the war, we might be still living under British rule and Canada certainly would have never gained independence.

By 1804 all the northern states had abolished slavery and in 1862 the emancipation proclamation was signed. Slavery was abolished on the Island of Britain but serfdom was still running rampant through the empire. If British loyalist and slaves didn’t fight for the “British cause”, the Revolutionary War might have ended quickly and speed up the timeline of the American abolishment of slavery.

Has America done anything right? What about World War I or II? It’s just sad people hate their county so much. I’m confused why people who hate America don’t leave. The last section of this article is the most telling, a call for only majority rule and a monarch.

Direct Quotes

This July 4, let's not mince words: American independence in 1776 was a monumental mistake. We should be mourning the fact that we left the United Kingdom, not cheering it.

We obviously can't be entirely sure how America would have fared if it had stayed in the British Empire longer, perhaps gaining independence a century or so later, along with Canada.

But I'm reasonably confident a world in which the revolution never happened would be better than the one we live in now, for three main reasons: Slavery would've been abolished earlier, American Indians would've faced rampant persecution but not the outright ethnic cleansing Andrew Jackson and other American leaders perpetrated, and America would have a parliamentary system of government that makes policymaking easier and lessens the risk of democratic collapse.

It's true that had the US stayed, Britain would have had much more to gain from the continuance of slavery than it did without America. It controlled a number of dependencies with slave economies — notably Jamaica and other islands in the West Indies

In 1775, after the war had begun in Massachusetts, the Earl of Dunmore, then governor of Virginia, offered the slaves of rebels freedom if they came and fought for the British cause

America would have a better system of government if we'd stuck with Britain

we would've, in all likelihood, become a parliamentary democracy rather than a presidential one.

And parliamentary democracies are a lot, lot better than presidential ones.

The US is saddled with a Senate that gives Wyoming the same power as California, which has more than 66 times as many people. Worse, the Senate is equal in power to the lower, more representative house.

Finally, we'd still likely be a monarchy, under the rule of Elizabeth II, and constitutional monarchy is the best system of government known to man.

And monarchs are better.

0 notes

Text

Nikole Hannah-Jones Isn’t Done Challenging The Story Of America

Just about 16 minutes into the opening episode of Hulu’s “The 1619 Project” docuseries, the journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones walks through Colonial Williamsburg in a pair of red-and-black Air Jordans.

On a bench outside the building that was once the Virginia governor’s mansion, Hannah-Jones is joined by award-winning historian Woody Holton to talk about the birth of America.

Specifically, they are there to talk about John Murray, the Earl of Dunmore, who was Virginia’s colonial governor during the American Revolution. In 1775, Dunmore issued a proclamation that, among other things, declared that any enslaved person who fought on behalf of Britain against the colonists would be granted their freedom — a proclamation that “infuriated White Southerners,” Holton says.

“So,” Hannah-Jones replies, “you have this situation where many Virginians and other Southern colonists, they’re not really convinced that they want to side with the patriots, and this turns many of them toward the revolution, is that right?”

“If you ask them, it did. The record is absolutely clear,” says Holton, a professor of early American history at the University of South Carolina. “I can’t think of a point that I could make about the American Revolution where I could compile as many quotes as I can from White Southerners saying how furious they are.”

That conversation serves the latest rebuttal to the controversy that has engulfed the project since its initial publication, as a series of articles in the New York Times Magazine, in August 2019. (The six-part Hulu series is an on-screen adaptation, and expansion, of that Pulitzer award-winning series, which has also included a best-selling book, podcast and school curriculum.) -(source: the washington post)

DNA America

“It’s what we know, not what you want us to believe.”

#dna #dnaamerica #news #politics #1619

1 note

·

View note

Text

A “little groggy”: the deputy sheriff of Baltimore and his “bowl of toddy”

Photograph of two hot toddy drinks

On December 21, 1776, Sergeant John Hardman of the Edward Veazey's Seventh Independent Company arrived at a public prison in Baltimore Town with captured British soldiers. [1] He was there escorting the British prisoners from Philadelphia. That night, Hardman ordered a “bowl of toddy” for the prisoners. Toddy, a popular drink originally adopted by the British, consisted of rum, hot water, and sugar.

Reposted from Academia.edu and History Hermann WordPress post. I originally wrote this when I worked at the Maryland State Archives on the Finding the Maryland 400 project.

Two other men, Daniel Curtis, the Baltimore County Sheriff, and John Ross, his deputy, asked for a “bowl of liquor.” [2] Ross, also a keeper of the town’s poor house, engaged in a friendly conversation with the prisoners, amongst whom Hardman was sitting. [3]

What happened next made people uneasy. Ross lifted the bowl of toddy, meant for the prisoners. He offered a toast, drinking to “damnation to General Washington & his army” and success “to Lord Howe & his army,” as well as to Lord Dunmore. [4] It was not unusual that he made a toast. [5] However, guards, likely Continental soldiers, saw his loyalty as antagonistic to the revolutionary cause. Since the Stamp Act in 1765, British royalty were praised less than the American colonists in toasts. This was magnified after independence.

Ross’s toast was particularly inflammatory in Baltimore. In 1775, Dunmore, then Governor of Virginia, declared that enslaved blacks and indentured servants who joined British ranks would become free. While few servants and enslaved blacks responded to his proclamation, the order echoed through the Chesapeake Bay as Dunmore formed the “Ethiopian Regiment.” [6] When Ross toasted to Dunmore, the prison guards were sure he was a sympathizer of the British Crown.

By the second toast, Ross, appearing a “little groggy,” asked the prisoners to drink “the same toast.” [7] The prisoners refused and Ross became belligerent. He drank the toddy, declaring that “they should not drink his toddy,” and that the prisoners should get a bowl for themselves. Then, appearing to “be a little in liquor,” he changed his allegiance. Ross “drank damnation to General or Lord Howe.” [8] Afterward, Hardman “challenged the said Ross,” saying he “would mark him” down for his disturbing conduct. Later, Hardman asked several people about Ross’s identity. [9]

James Calhoun, Chairman of the Committee of Observation for Baltimore Town, a provisional government in Baltimore, compiled depositions about the event in January 1777. [10] Ross was told to attend the next meeting of Maryland Council of Safety. On January 27, Ross appeared before the Council to directly address Hardman’s complaint, but Hardman was not present. [11] This was likely because he had enlisted in the Second Maryland Regiment and was not in the state at the time. The Council told Ross to appear before the Maryland General Assembly the following month on February 10. The resolution of this incident is not known. [12]

Drunken outbursts were common during colonial times. In 1770, every American over age 15, drank an average of about six shot glasses of whiskey, which is about 40 percent alcohol, every day! [13] With drinking alcohol as an important past time, it was viewed as pleasant and useful by fellow colonists. While public drunkenness was illegal, drinking played a central role in social activities, with taverns and public houses serving as places to drink and forums for revolutionary ideas. [14]

The Revolutionary War also changed Americans’ drinking habits. Americans settled on whiskey as a substitute for molasses and rum which were limited by the British naval blockade. [15] During the war, troops of the British and Continental armies were issued rations for alcohol but both armies prohibited drunkenness. [16] After the war, alcohol consumption declined slightly, but increased after 1790. [17] The spike in alcohol consumption ended with the success of the temperance movement in the nineteenth century, with more Americans criticizing alcohol use. [18]

– Burkely Hermann, Maryland Society of the Sons of American Revolution Research Fellow, 2016.

© 2016-2023 Burkely Hermann. All rights reserved.

Notes

[1] Journal and Correspondence of the Maryland Council of Safety, January 1-March 20, 1777, Archives of Maryland Online Vol. 16, 47, 48; Deposition about the statements of John Ross, Sub-Sheriff in Baltimore, December 23, 1776, Maryland State Papers, Red Books, Red Book 13, MdHR 4575-179 [MSA S989-19, 1/6/4/7]; Proceedings and Acts of the General Assembly, 1766-1768, Archives of Maryland Online Vol. 61, 14, 86, 87, 185, 299, 308, 310, 361, 368, 387, 389, 390, 393, 442, 520; Proceedings and Acts of the General Assembly, 1769-1770, Archives of Maryland Online Vol. 62, 126; Journal and Correspondence of the Council of Maryland, 1780-1781, Archives of Maryland Online Vol. 45, 71, 72; Proceedings and Acts of the General Assembly, 1771 to June-July, 1773, Archives of Maryland Online Vol. 63, 37, 282; Correspondence of Governor Sharpe, 1757-1761, Archives of Maryland Online Vol. 9, 421; Proceedings and Acts of the General Assembly, October 1773 to April 1774, Archives of Maryland Online Vol. 64, 199, 337; Journal and Correspondence of the Maryland Council of Safety, January 1-March 20, 1777, Archives of Maryland Online Vol. 16, 374. The British soldiers, recruited in North Carolina, may have been captured at the Battle of White Plains. Hardman was under the command of Levin Winder, who had recently been appointed as a captain.

[2] Journal and Correspondence of the Maryland Council of Safety, January 1-March 20, 1777, Archives of Maryland Online Vol. 16, 47. When Hardman describes Ross as a “sub-sheriff” this means that Ross is an assistant or deputy sheriff.

[3] Deposition about the statements of John Ross, Sub-Sheriff in Baltimore; Proceedings and Acts of the General Assembly, 1769-1770, Archives of Maryland Online Vol. 62, 387, 403; Journal and Correspondence of the Maryland Council of Safety, January 1-March 20, 1777, Archives of Maryland Online Vol. 16, 47; Paul Starr, The Social Transformation of American Medicine: The rise of a sovereign profession and making of a vast industry (USA: Basic Books, 1982),105; Seth Rockman, Scraping By: Wage Labor, Slavery, and Survival in Early Baltimore (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009), 1, 194-196, 199-200, 203, 205-208, 210-212, 337; Camilla Townsend, Tales of Two Cities: Race and Economic Culture in Early Republican North and South America: Guayaquil, Ecuador, and Baltimore, Maryland (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2000), 37, 39, 122, 283-284; Proceedings and Acts of the General Assembly, 1766-1768, Archives of Maryland Online Vol. 61, 96; Proceedings and Acts of the General Assembly, October 1773 to April 1774, Archives of Maryland Online Vol. 64, 23; Journal and Correspondence of the Council of Maryland, 1780-1781, Archives of Maryland Online Vol. 45, 178, 267, 581; Journal and Correspondence of the Council of Maryland, 1789-1793, Archives of Maryland Online Vol. 72, 347; Journal and Correspondence of the Council of Maryland, 1781-1784, Archives of Maryland Online Vol. 48, 150; Proceedings and Acts of the General Assembly, October 1773 to April 1774, Archives of Maryland Online Vol. 64, 259, 260, 261, 262, 263, 264, 265, 266, 267, 268, 269. Interestingly, no hard liquors were allowed in the poor house. The poor house, also called an almshouse, on the outskirts of Baltimore Town, was created to serve as “relief” for the poor. It aimed to “reform” the poor to not be disorderly and engage in “meaningful” work.

[4] Deposition about the statements of John Ross, Sub-Sheriff in Baltimore; Journal and Correspondence of the Maryland Council of Safety, January 1-March 20, 1777, Archives of Maryland Online Vol. 16, 46. The prison guards may have also been suspicious of him considering that he never praised the Continental Army and George Washington in any of his toasts.

[5] Peter Thompson, “”The Friendly Glass”: Drink and Gentility in Colonial Philadelphia.” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 113, no. 4 (1989): 553, 557-558, 560; Richard J. Hooker, “The American Revolution Seen through a Wine Glass.” The William and Mary Quarterly 11, no. 1 (1954): 52-77; Thaddeus Russell, A Renegade History of the United States (New York: Free Press, 2010), 5. Not all of those who are toasted were praised. Hardman suspected Ross as “a Tory.”

[6] Gary B. Nash, Red, White, and Black: The Peoples of Early North America (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2000, fourth edition), 274-275; Ray Raphael, A People’s History of the American Revolution (New York: Perennial, 2002, second edition), 309-311, 316, 320-327, 331-332, 335, 342, 355, 358, 385, 397; Ronald Hoffman, A Spirit of Dissension: Economics, Politics and the Revolution in Maryland (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1973), 184-185. This regiment fought in the Battle of Great Bridge (1775) near Chesapeake, Virginia before many of those in the regiment succumbed to smallpox. In later years, every time British ships would come down the Chesapeake Bay, runaway slaves would flock to the incoming ships. Enslaved blacks renounced their owners and flocked to British lines, with some fugitives attacking plantations of their former masters on the Eastern Shore. Not surprisingly, desperate slaveowners in Maryland appealed to the state government, originally the Maryland Council of Safety, asking them for assistance.

[7] Journal and Correspondence of the Maryland Council of Safety, January 1-March 20, 1777, Archives of Maryland Online Vol. 16, 46, 47.

[8] Deposition about the statements of John Ross, Sub-Sheriff in Baltimore.

[9] Deposition about the statements of John Ross, Sub-Sheriff in Baltimore. This is interesting considering that earlier prisoners had told Ross who Hardman was.

[10] Journal and Correspondence of the Maryland Council of Safety, January 1-March 20, 1777, Archives of Maryland Online Vol. 16, 46, 47. These people made depositions: Elizabeth Dewit, wife of prison guard Thomas Dewit, prison guard Constantine O’Donnell, John Hardman, sergeant of Edward Veazey‘s company, Ross’s associate Daniel Curtis, and civil servant William Spencer.

[11] Journal and Correspondence of the Maryland Council of Safety, January 1-March 20, 1777, Archives of Maryland Online Vol. 16, 59, 60, 83.

[12] Journal and Correspondence of the Council of Maryland, April 1, 1778 through October 26, 1779, Archives of Maryland Online Vol. 21, 568. Ross appears again in October 1779 asking for, along with a number of others, a recount in an “unfair” county election of sheriffs, but the Council of Maryland refused to do that, saying that the election was “valid & effectual.”

[13] Jessica Kross, “”If You Will Not Drink with Me, You Must Fight with Me”: The Sociology of Drinking in the Middle Colonies.” Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies 64, no. 1 (1997): 28; W.J. Rorabaugh, The Alcoholic Republic: An American Tradition (New York: Oxford University Press, 1979), 10; Russell, 6-7; Alcohol and Drugs in North America: A Historical Encyclopedia, Vol 1: A-L (ed. David M. Fahey and Jon S. Miller, Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO, 2013), 84; W. J. Rorabaugh, “Alcohol in America.” OAH Magazine of History 6, no. 2 (1991):17. Americans drank whiskey that “80 proof,” referring to the weight of an average spirit and indicating the drink is 40 percent alcohol. Historian Jessica Kross said that this number “might well understate beer consumption and assumes women drank more than men” which was echoed by other scholars. Americans, of all ages, guzzled three and half gallons of alcohol per year, on average. They drank rum and cider at every meal.

[14] Kross, 43; Peter Thompson, “”The Friendly Glass”: Drink and Gentility in Colonial Philadelphia.” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 113, no. 4 (1989): 549; Russell, 20, 26; Christine Sismondo, America Walks Into A Bar: A Spirited History of Taverns and Saloons, Speakeasies and Grog Shops (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), xv, 54, 78-79; Peter Thompson, Rum Punch and Revolution: Taverngoing and Public Life in Eighteenth-Century Philadelphia (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1999), 13, 20, 75, 143, 145. Taverns were also places for revolutionary recruiting and organizing. Politicians even fished for votes among inebriated citizens.

[15] Rorabaugh, 17; Mark Edward Lender and James Kirby Martin, Drinking In America: A History (New York: The Free Press, 1987), 31. At the same time, rum consumption declined since rum became associated with Great Britain.

[16] Mark Edward Lender and James Kirby Martin, Drinking In America: A History (New York: The Free Press, 1987), 32; Eric Burns, The Spirits of America: A Social History of Alcohol (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2004), 16; Sarah H. Meachan, Every Home a Distillery: Alcohol, Gender, and Technology in the Colonial Chesapeake (Baltimore: JHU Press, 2009), 5, 95. George Washington specifically hated alcohol abuse even though he ordered alcohol for his men, as a morale booster.

[17] Rorabaugh, 10; Korss, 48; Thompson, 549; Russell, 28, 30, 33; Sharon V. Salinger, Taverns and Drinking in Early America (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002), 246, 252, 282; Rorabaugh, 21, 25, 36, 67, 136, 149-150, 167, 219; Mark Edward Lender and James Kirby Martin, Drinking In America: A History (New York: The Free Press, 1987), 38, 46; The Concise Princeton Encyclopedia of American Political History (ed., Michael Kazin, Rebecca Edwards, and Adam Rothman, Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2011), 405. Americans continued to drink in huge quantities, despite the failed efforts of temperance advocates, like Benjamin Rush, to limit consumption in taverns, inns, and drinking houses.

[18] Peter McCandless, Slavery, Disease, and Suffering in the Southern Lowcountry (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2011), 196, 272; Drugs in America: A Documentary History (ed. David F. Musto, New York: New York University Press, 2002), 3; Scott C. Martin, “Introduction: Toward a Cultural Theory of the Market Revolution,” Cultural Change and the Market Revolution in America, 1789-1860 (ed. Scott C. Martin, Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2005), 3; Mitchel P. Roth, Crime and Punishment: A History of the Criminal Justice System (Second Edition, United States: Wadsworth Cengage Learning, 2010), 112; Marvin Kitman, The Making of the President 1789: The Unauthorized Campaign Biography (New York: Grove Press, 1989), 40.

#bowl of toddy#groggy#baltimore#sheriffs#maryland 400#alcoholism#hot toddy#philadelphia#british prisoners#pows#revolutionary war#american revolution#us history

0 notes

Text

The Forgotten Fifth

I started this post years ago, but unfortunately since have lost many of my notes. Still, at this time (and the day after Juneteenth) I think it’s critical that we understand that Black Americans have been here since the beginning, have advocated for themselves, and have fought for themselves. Our inability to “see” Blacks in American history means we don’t understand why Native American slaughter and Westward expansion happened, we discuss the goals of the antebellum “South” as though 4 million Blacks did not live there (and comprised nearly 50% of the population in some states), we rarely bring forward the consequences of the self-emancipation of enslaved Blacks on the Confederate economy, and so on.

It’s also critical to reject false historical narratives that place white Americans as white saviors rescuing Blacks. Within the Hamilton fandom, there is a strong white supremacist narrative embedded in the praise for John Laurens*, an individual who could not be bothered to ensure the enslaved men with him were properly clothed - which says more about his attitude towards Blacks than any high language way he could write about them as an abstraction. And if we want to praise a white person for playing a big role in encouraging the emancipation of Blacks during the American Revolution, the praise should go to the Loyalist Lord Dunmore in that roundabout way.

The Forgotten Fifth is the title of Harvard historian Gary B. Nash’s book, and refers to the 400,000 people of African descent in the North American colonies at the time of the Declaration of Independence, one-fifth of the total population. Unlike commonly depicted, Blacks in the colonies were not waiting around for freedom to be given to them, or to assume a place as equals in the new Republic. Enslaved Blacks seized opportunities for freedom, they questioned and wrote tracts asking what the Declaration of Independence meant for them, they organized themselves. And they chose what side to fight on depending on the best offers for their freedom. At Yorktown in 1781, Blacks may have comprised a quarter of the American army.

Most of what’s below is taken from wikipedia, other parts are taken from sources I have misplaced - the work is not my own.

In May 1775, the Massachusetts Committee of Safety enrolled slaves in the armies of the colony. The action was adopted by the Continental Congress when they took over the Patriot Army. But Horatio Gates in July 1775 issued an order to recruiters, ordering them not to enroll "any deserter from the Ministerial army, nor any stroller, negro or vagabond. . ." in the Continental Army.[11] Most blacks were integrated into existing military units, but some segregated units were formed.

In November 1775, Virginia’s royal governor, John Murray, 4th early of Dunmore, declared VA in a state of rebellion, placed it under martial law, and offered freedom to enslaved persons and bonded servants of patriot sympathizers if they were willing to fight for the British. Lord Dunmore’s Ethiopian Regiment consisted of about 300 enslaved men.

in December 1775, Washington wrote a letter to Colonel Henry Lee III, stating that success in the war would come to whatever side could arm the blacks the fastest.[15] Washington issued orders to the recruiters to reenlist the free blacks who had already served in the army; he worried that some of these soldiers might cross over to the British side.

Congress in 1776 agreed with Washington and authorized re-enlistment of free blacks who had already served. Patriots in South Carolina and Georgia resisted enlisting slaves as armed soldiers. African Americans from northern units were generally assigned to fight in southern battles. In some Southern states, southern black slaves substituted for their masters in Patriot service

In 1778, Rhode Island was having trouble recruiting enough white men to meet the troop quotas set by the Continental Congress. The Rhode Island Assembly decided to adopt a suggestion by General Varnum and enlist slaves in 1st Rhode Island Regiment.[16] Varnum had raised the idea in a letter to George Washington, who forwarded the letter to the governor of Rhode Island. On February 14, 1778, the Rhode Island Assembly voted to allow the enlistment of "every able-bodied negro, mulatto, or Indian man slave" who chose to do so, and that "every slave so enlisting shall, upon his passing muster before Colonel Christopher Greene, be immediately discharged from the service of his master or mistress, and be absolutely free...."[17] The owners of slaves who enlisted were to be compensated by the Assembly in an amount equal to the market value of the slave.

A total of 88 slaves enlisted in the regiment over the next four months, joined by some free blacks. The regiment eventually totaled about 225 men; probably fewer than 140 were blacks.[18] The 1st Rhode Island Regiment became the only regiment of the Continental Army to have segregated companies of black soldiers.

Under Colonel Greene, the regiment fought in the Battle of Rhode Island in August 1778. The regiment played a fairly minor but still-praised role in the battle. Its casualties were three killed, nine wounded, and eleven missing.[19]

Like most of the Continental Army, the regiment saw little action over the next few years, as the focus of the war had shifted to the south. In 1781, Greene and several of his black soldiers were killed in a skirmish with Loyalists. Greene's body was mutilated by the Loyalists, apparently as punishment for having led black soldiers against them.

The British promised freedom to slaves who left rebels to side with the British. In New York City, which the British occupied, thousands of refugee slaves had migrated there to gain freedom. The British created a registry of escaped slaves, called the Book of Negroes. The registry included details of their enslavement, escape, and service to the British. If accepted, the former slave received a certificate entitling transport out of New York. By the time the Book of Negroes was closed, it had the names of 1336 men, 914 women, and 750 children, who were resettled in Nova Scotia. They were known in Canada as Black Loyalists. Sixty-five percent of those evacuated were from the South. About 200 former slaves were taken to London with British forces as free people. Some of these former slaves were eventually sent to form Freetown in Sierra Leone.

The African-American Patriots who served the Continental Army found that the postwar military held no rewards for them. It was much reduced in size, and state legislatures such as Connecticut and Massachusetts in 1784 and 1785, respectively, banned all blacks, free or slave, from military service. Southern states also banned all slaves from their militias. North Carolina was among the states that allowed free people of color to serve in their militias and bear arms until the 1830s. In 1792, the United States Congress formally excluded African Americans from military service, allowing only "free able-bodied white male citizens" to serve.[22]

At the time of the ratification of the Constitution in 1789, free black men could vote in five of the thirteen states, including North Carolina. That demonstrated that they were considered citizens not only of their states but of the United States.

Here’s another general resource: https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part2/2narr4.html

*The hyper-focus on John Laurens is one of the ways white people in the Hamilton fandom tell on themselves - they center a narrative about freedom for Blacks around a white man (no story is important unless white people can stick themselves at the center of it, no matter how historically inaccurate!). Lord Dunmore’s 1775 proclamation, if known, is seen just as cynically politically smart, while Laurens’ vision is seen as somehow noble.

**Whether Lord Dunmore’s Proclamation - encouraging enslaved Blacks to rise up and kill their owners and join the Loyalist cause - played a major role in the progress of the American Revolution was hotly debated as part of the 1619 project.

4 notes

·

View notes

Link

But the debates playing out now on social media and in op-eds between supporters and detractors of the 1619 Project misrepresent both the historical record and the historical profession. The United States was not, in fact, founded to protect slavery—but the Times is right that slavery was central to its story. And the argument among historians, while real, is hardly black and white. Over the past half-century, important foundational work on the history and legacy of slavery has been done by a multiracial group of scholars who are committed to a broad understanding of U.S. history—one that centers on race without denying the roles of other influences or erasing the contributions of white elites. An accurate understanding of our history must present a comprehensive picture, and it’s by paying attention to these scholars that we’ll get there.

...

Far from being fought to preserve slavery, the Revolutionary War became a primary disrupter of slavery in the North American Colonies. Lord Dunmore’s Proclamation, a British military strategy designed to unsettle the Southern Colonies by inviting enslaved people to flee to British lines, propelled hundreds of enslaved people off plantations and turned some Southerners to the patriot side. It also led most of the 13 Colonies to arm and employ free and enslaved black people, with the promise of freedom to those who served in their armies. While neither side fully kept its promises, thousands of enslaved people were freed as a result of these policies.

21 notes

·

View notes

Photo

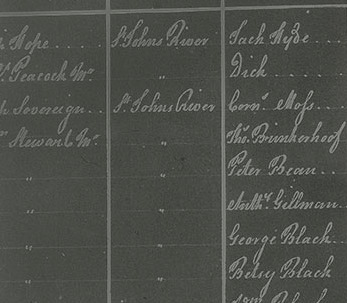

Little-known document offering details about the names, ages, places of origin, and personal situations of thousands of blacks who fled American slavery and hoped to find their promised land in Canada.

It is called the Book of Negroes.

The handwritten ledger runs to about 150 pages. It offers volumes of information about the lives of black people living more than two centuries ago. On an anecdotal level, it tells us who contracted smallpox, who was blind, and who was travelling with small children.

One entry for a woman boarding a ship bound for Nova Scotia describes her as bringing three children, with a baby in one arm and a toddler in the other. In this way, the Book of Negroes gives precise details about when and where freedom seekers managed to rip themselves free of American slavery.

As a research tool it offers historians and genealogists the opportunity to trace and correlate people backward and forward in time in other documents, such as ship manifests, slave ledgers, and census and tax records.

Sadly, however, the Book of Negroes has been largely forgotten in Canada. And that is a shame. Dating back to an era when people of African heritage were mostly excluded from official documents and records, the Book of Negroes offers an intimate and unsettling portrait of the origins of the Black Loyalists in Canada.

Compiled in 1783 by officers of the British military at the tail end of the American Revolutionary War, the Book of Negroes was the first massive public record of blacks in North America. Indeed, what makes the Book of Negroes so fascinating are the stories of where its people came from and how it came to be that they fled to Nova Scotia and other British colonies.

The document, which is essentially a detailed ledger, contains the names of three thousand black men, women, and children who travelled — some as free people, and others the slaves or indentured servants of white United Empire Loyalists — in 219 ships sailing from New York between April and November 1783. The Book of Negroes did more than capture their names for posterity. In 1783, having your name registered in the document meant the promise of a better life. Source: Canadahistory.com

Black Paraphernalia Disclaimer- images from Google Images

The first proclamation appeared in November 1775, just months after the Revolutionary War had begun. To attract more support for the British forces, John Murray, the Virginia governor who was formally known as Lord Dunmore, infuriated American slave owners with his famous and the irony of him was he himself was a slave owner.

Dunmore Proclamation:

To the end that peace and good order may the sooner be restored ... I do require every person capable of bearing arms to resort to His Majesty’s standard ... and I do hereby further declare all indented servants, Negroes, or others (appertaining to Rebels) free, that are able and willing to bear arms, they joining His Majesty’s Troops, as soon as may be, for the more speedily reducing this Colony to a proper sense of their duty to his Majesty’s crown and dignity. Enslaved blacks attentively followed this proclamation, fleeing their owners to serve the British war effort.

The Philipsburg Proclamation

Came four years later and was designed to attract not just those “capable of bearing arms,” but any black person, male or female, who was prepared to serve the British in supporting roles as cooks, laundresses, nurses, and general laborers. Issued in 1779 by Sir Henry Clinton, commander-in-chief of the British forces, it promised: “To every Negro who shall desert the Rebel Standard, full security to follow within these lines, any occupation which he shall think proper.”

By 1782, as it became apparent that the British were losing the war, and as George Washington, commander-in-chief of the Continental Army, prepared to take control of New York City, blacks in Manhattan became increasingly desperate about their prospects. They had been promised freedom in exchange for service in wartime.

But would the British live up to their side of the bargain?

For a time, it looked as though they would not. When the terms of the provisional peace treaty between the losing British and the victorious rebels were finally made known in 1783, the loyal blacks felt betrayed. Article 7 of the peace treaty left the Black Loyalists with the impression that the British had abandoned them entirely. It said

All Hostilities both by Sea and Land shall from henceforth cease all prisoners on both sides shall be set at Liberty and His Britannic Majesty shall with all convenient Speed and without Causing any destruction or carrying away any Negroes or other Property of the American Inhabitants withdraw all its Armies, Garrisons, and Fleets, from the said United States.

Boston King, a Black Loyalist who fled from his slave owner in South Carolina, served with the British forces in the war, and went on to become a church minister in Nova Scotia and subsequently in Sierra Leone, noted in his memoir the terror that blacks felt when they discovered the terms of the peace treaty:

The horrors and devastation of war happily terminated and peace was restored between America and Great Britain, which diffused universal joy among all parties, except us, who had escaped from slavery and taken refuge in the English army; for rumor prevailed at New York, that all the slaves, in number 2,000, were to be delivered up to their masters, although’ some of them had been three or four years among the English.

This dreadful rumor filled us all with inexpressible anguish and terror, especially when we saw our old masters coming from Virginia, North Carolina, and other parts, and seizing upon their slaves in the streets of New York, or even dragging them out of their beds. Many of the slaves had very cruel masters, so that the thoughts of returning home with them embittered life to us. For some days we lost our appetite for food, and sleep departed from our eyes

Source: Canadahistory.com please click on link for the full fascinatiing story of the Book of Negros

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Two Emancipation Proclamations

You no doubt recall the unfortunate Lord Dunmore, bullied by Patrick Henry then surprised by outright revolt of colonists. Dunmore issued the first Emancipation proclamation as a contingent quid-pro-quo. All a slave had to do was bear arms against the insurgents and for King and Country to become a freedman for life under British rule. Now, would you argue from that precedent that the…

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Text

It is the claims about this proclamation that frankly make me wonder how anyone gave Gerald Horne a degree in history:

I recognize again that this may come across as mean spirited and more than a bit condescending but in this case both are earned. The Counterrevolution of 1776 would have you believe a proclamation made in November 1775 caused the outbreak of a war in April at Lexington and Concord. Linear time does not work this way, the proclamation and the challenges it introduced in the future United States were in reaction to the outbreak of a rebellion forged not by challenges to slavery, but by the British Empire's cracking down on what a more uncharitable view could say was a bunch of rich people refusing to pay taxes and inciting mass urban chaos to get away with it.

To repeat, Lexington and Concord were months before this, and Dunmore's decisions marked the arrival of the war in the Southern colonies. Events that follow other events cannot cause what they are in reaction to, it has never worked this way, and it never will. That people read a book that lied about the simple 'Event A leads to Event B' sequence and came across impressed rather than noting a lie that blatant inclines me to respect very little of the intelligence of anyone who read that book and thought it was valid. You might as well pick up a Michael Savage book and declare it cutting-edge intellect and you'd gain just as much from it.

All that aside the actual Proclamation very much was a laser-guided attack on a revolution where, to use a contemporary turn of phrase 'the loudest yelps for liberty came from the mouths of drivers of Negroes' and it meant in retrospect that until the 1860s the most integrated US force to ever fight a war was the Continental Army, on the one hand, and more Black people fought for freedom against the United States than ever fought for it.

#lightdancer comments on history#black history month#military history#american revolutionary war#dunmore's proclamation#you literally cannot claim an event in the winter of a year caused the events in the spring before that winter#time does not work that way

0 notes

Link

Really interesting look at the founding fathers and slavery as a motivation for the revolution.

The 1619 project and Tom Cotton is what started me down this path.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Seymour Burr, Renegade Patriot

Once in bondage to the prominent Burr family, Seymour gave his enslavers the slip and threatened to join the British forces unless he was emancipated. Now he fights for his freedom in the Continental Army.

While many Americans joined the war effort to free themselves from British rule, others were fighting for their personal freedom. The promise of liberty, however, did not often come from the side of the Patriots. Seymour Burr first turned to the British before he enlisted in the Continental Army.

As an enslaved African American, the details of Seymour Burr’s early life are fuzzy. An enlistment document indicates that he was born in Guinea, West Africa in either 1754 or 1762. He is said to have been captured around the age of 7, and brought to the colonies via the Atlantic slave trade. By the start of the Revolution, he was enslaved by members of the Burr family in Connecticut, relatives of later vice president Aaron Burr.

On November 7, 1775, Lord Dunmore, the royal governor of Virginia, signed a proclamation promising freedom to anyone in service to the Patriots, either by enslavement or indentured servitude, who would abandon their masters and enlist in the British army. Within a month, hundreds of enslaved Black men answered Dunmore’s call. This was expanded in 1779 by General Henry Clinton’s Philipsburg Proclamation, which extended the British promise of freedom to any person enslaved by Americans, regardless of their ability to serve in the military. By the end of the war, at least 30,000 enslaved people from Virginia alone had escaped to the British side, along with thousands of others from throughout the colonies. Seymour Burr was almost among them.

Following Dunmore’s Proclamation, Seymour attempted to escape the Burr household to join the British forces, but was intercepted and returned to his enslavers. Likely fearing a repeat escape or a rebellion in their own home, the Burrs had a proposition for Seymour- if he would fight on behalf of the Patriot army, they would free him once his service was over. Seymour accepted, and enlisted in the Continental Army. He fought at Fort Catskill, and served beside George Washington through the winter of 1777 at Valley Forge.

Seymour left the army in 1782, at which time he was freed by the Burrs. In 1805, he married a Ponkapoag widow and inherited six acres of her late husband’s land outside of Canton, Massachusetts. He also collected a military pension later in his life. Seymour died on February 17, 1837.

Character Sheet: Seymour Burr

#ttrpg#5e#revwar#revolutionary war#US history#american revolution#colonial#AWI#dungeons and dragons#dnd#d&d

1 note

·

View note

Quote

Far from being fought to preserve slavery, the Revolutionary War became a primary disrupter of slavery in the North American Colonies. Lord Dunmore’s Proclamation, a British military strategy designed to unsettle the Southern Colonies by inviting enslaved people to flee to British lines, propelled hundreds of enslaved people off plantations and turned some Southerners to the patriot side. It also led most of the 13 Colonies to arm and employ free and enslaved black people, with the promise of freedom to those who served in their armies. While neither side fully kept its promises, thousands of enslaved people were freed as a result of these policies.

Opinion | I Helped Fact-Check the 1619 Project. The Times Ignored Me. -

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

Should the British have focused on keeping the Continental army and rebellion contained to the north Atlantic coast while building loyalist support in the south and blockading the ports, fighting a war of attrition while also turning the southern colonies away by promising more rights and powers should they lend men and arms to the fight up north?

Good question. In short I’d say this was the second best option open to the Crown (the best being the swift, targeted destruction of the Continental Army). However, I don’t think the odds of it ever being employed without hindsight were ever very high, and I think there’s still a slightly greater than even chance of it still failing even if it was implements.

The pros; After evacuating Boston there was essentially no British presence from New England to East Florida. This gave Britain the freedom to potentially undertake the sea-based war of attrition you mention, very similar to the US’s proposed “Anaconda Plan” for the American Civil War a century later. Blockading major ports and raiding coastal towns would’ve almost definitely dealt near-fatal damage to the colonial economy. Rights and powers were also a relatively potent carrot, and would’ve been better served in the south without the added stresses caused by the Dunmore Proclamation.

The cons; While perhaps leading to the collapse of the rebellion, such a strategy would’ve done little to address its causes or amend colonial discord. It would have also had an abrasive effect on the British economy and stretched the Royal Navy’s resources if another power entered the war. We know that the idea the south possessed a large population of Loyalists willing to actively support the crown was false - most people just wanted to wait the war out and not get involved, especially with revolutionaries violently suppressing dissenters. The concept of sectioning off a part of the colonies had also been tried previously - Burgoyne’s campaign was partly designed to separate New England from the other colonies, as the heartland of rebellion, sort of like cutting off an infected body part. We know how that ended.

In terms of real-world practicalities, it wasn’t really an option for Britain in 1775. The Crown’s army had just been evicted from the colonies. A statement had to be made, and the huge flotilla and subsequent invasion, and flawless capture of, New York was just the sort of statement the Crown wanted. It would be very difficult to have said “just let them have the colonies and let’s strangle them slowly.” And I’m not sure if, long-term, it would’ve had a better outcome (beyond the fact possibly a lot less people would’ve died)

9 notes

·

View notes

Quote

With the coming of the Revolution, black volunteers, Prince Hall among them, saw action in the early battles of Concord, Lexington and Bunker Hill.

When George Washington, named to head the Revolutionary Army, arrived at Cambridge to take command of his troops, he found scores of blacks among them. Although he and his officers allowed them to continue serving, they refused at first to accept them as regular members of the Continental Army.

Tradition says that it was Hall who led a delegation directly to the general in protest, reminding Washington that many colonists still sided with the British, that thousands of slaves had already responded to Lord Dunmore's proclamation welcoming Negroes into his forces, and that more would surely follow if only to obtain their personal freedom if they were barred from joining the Continental Army.

Washington thereupon agreed to allow them to join, and so informed the Congress. After the disastrous winter at Valley Forge, he abandoned all his reservations, accepting more than 5,000 into his forces. Six army enlistment records attest that Princes Hall was among those black members of the American Revolutionary Army.

Charles H. Wesley Ph.D.

#prince hall#george washington#revolutionary war#freemasons#freemason#Freemasonry#history#black history month

8 notes

·

View notes