#battle of bouvines

Text

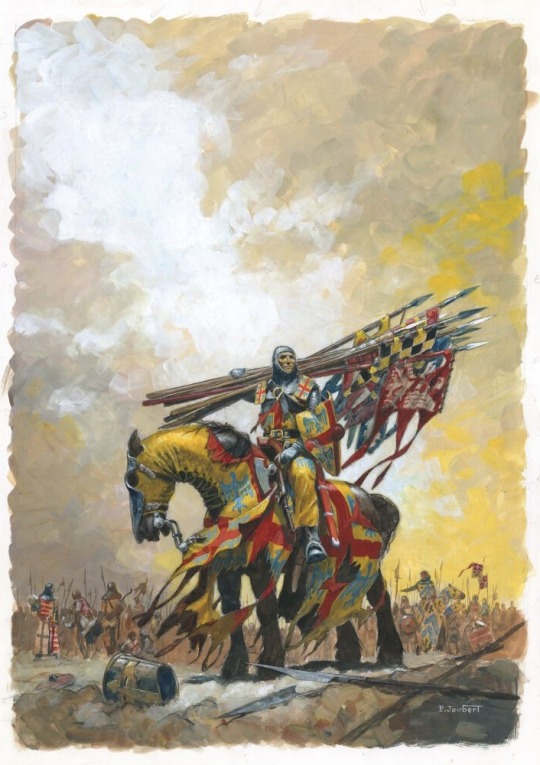

Chevalier de Montmorency by Pierre Joubert

#battle of bouvines#montmorency#knight#knights#medieval#middle ages#art#pierre joubert#history#france#europe#heraldry#banners#european#french#bouvines#matthieu ii de montmorency#matthew ii of montmorency#holy roman empire#flanders#angevin empire#battle#war

633 notes

·

View notes

Text

Philippe Auguste

The Capetian monarchy was an institution, with traditions and restrictions. But the personal element in the medieval period always remained a significant factor. To what extent the government of any individual king was personal is not easy to determine. In general it is true that counsellors could advise, but could not normally decide policy. Others were there to obey the will of the monarch, perhaps to help form it, but not to take over from it. Philip's views were shaped by many influences: by observing his father's work, by his father's advice, by his own education, by the advice he received from counsellors, by the experience of governing, by the views of churchmen, theologians, popes and fellow rulers, but in the end they were his views and could be imposed to the extent of the power of the monarchy at the time. Philip's court and government reflected his own personality. Gerald of Wales pointed out its contrasts with the Plantagenet court, the French king's being more sober as we have seen, more quiet in tone, more proper, with swearing forbidden. Philip brought about significant changes: less reliance on the magnates, a lesser role for his family; a greater place for the selected dose counsellors and for relatively humble knights.

It has been suggested that Philip's intellectual gifts were 'modest', which, although direct evidence is not easily available, seems to conflict with what we know about the king's abilities. He was able to deal with the bright men around him, such as Peter the Chanter. He was able to supervise governmental development and the administration, which needed a considerable grasp of accounting as well as a degree of literacy. His ability to deal with the papacy reveals a clear understanding of legal argument and his rights, and a firm determination to protect them. He was rarely outmanoeuvred by even the cleverest of his opponents. Philip went to war as any leader of his period would, but he was more prepared than most to seek and make peace.

Rigord said that Philip's aim was 'to deliver the weak from the tyranny of the strong', and that 'his first triumph is to see peace re-established'. His tolerance and mild temper puzzled the aggressive Bertran de Born, who thought the French needed a leader and had not found one in Philip, who did not become angry. Bertran preferred the attitude of Richard the Lionheart, for whom 'peace and truce have never been noble'. For Bertran it was a sneer to suggest that Philip liked peace even more than the noted diplomat Archbishop Peter of Tarentais. Bertran had cause to regret his underestimation of Philip, when the king later used his authority to replace Bertran as lord of Hautefort. No doubt that act was executed on the advice of counsellors, and Bertran could further nurse his belief that Philip was 'badly advised and worse guided'.

Philip did in fact at times lose his temper, but usually with some point, as when he chopped down the elm on the Norman border, declaring by actions rather than words that he no longer accepted the Plantagenet stance on their rights to bring the king to the edge of their territories before they would hold discussions. Nor were his diplomatic activities always appreciated by his enemies. He could manoeuvre and manipulate with the best of them; he was the 'sower of discord' according to one English chronicler. To take just one example of his methods: in the conquest of Normandy he knew that Rouen was the key, which afterwards he would need to govern. Therefore he did not simply crush Rouen, and chose to discuss with the leading citizens what they would gain from surrender. If allowed in, he promised: 'I will prove a kind and just master to you.' In modern times he has been called 'a statesman of the first water', 'the first royal statesman in French history' ; it is a reputation which in this country we have somehow failed to recognize.

[..]

Philip was generally modest and unassuming, as we have seen in contrast to Richard the Lionheart both in Sicily and in the Holy Land. Bertran de Born thought the French king presented his deeds in tin-plate rather than in gilt. But Philip was aware of the need to present a regal figure, dignified if not flamboyant: a public face of modesty but a recognition of his own powers. The scene painted by Mouskes of Philip entering a church and praying: 'I am but a man, as you are, but I am king of France', has a deep truth to it. There is also a story of Peter the Chanter telling Philip what were the attributes of an ideal sovereign; Philip replied that he should be contented with the king that he had.

The efforts to show his connection back to Charlemagne demonstrate Philip's effort to bolster the Capetian position. His mother, Adela, and his first wife, Isabella of Hainault, both claimed descent from Charlemagne. His natural son was named Peter Charlot, after the great emperor. And the Carolingian claim seems to have become generally accepted. Innocent III declared: 'it is common knowledge that the king of France is descended from the lineage of Charlemagne'. No doubt there was some weakness in the argument, but William the Breton refers to him as 'the descendant of Charlemagne', and the Welshman Gerald believed that Philip aimed to restore the monarchy to 'the greatness which it had in the time of Charlemagne'.

Philip wished to present an imperial image of French monarchy, hence the use of an eagle on his seal, the label 'Augustus' applied by Rigord, his sister's marriage to two Byzantine emperors, and the raising to the Latin imperial throne of two of his brothers-in-law. The same point was being emphasized when the sword of Charlemagne had been brandished at Philip' s coronation ceremony. As one of the Parisian masters wrote in 1210: 'the king is emperor in his realm'. The royal family was being distanced from other families, however noble; royal power was being set above noble power. It was not just a question of wealth and lands, but of the nature of monarchy, its prestige, its religious and mystical significance. The claimed association with Charlemagne, by the twelfth century a powerful figure in legend as well as a great historical emperor, was an important part of this process.

Philip was a tough-minded individual, he would not otherwise have been such a great king. Those who had experience of dealings with Louis VII found Philip a much harder opponent with more steel in his character. He had tremendous determination, and strong views on basic policies. Before his father's death, while still a teenager, Philip was prepared to rule, issuing charters without his father's consent, reacting against some of his father's policies. Before long he threw off the shackles of his mother and her powerful family, and soon afterwards of the count of Flanders. The English chronicler Howden thought he did it because he 'despised and hated all whom he knew to be familiar friends of his father', which seems a distortion, but at least underlines the point that Philip was of independent mind from the first.

Philip preferred his close counsellors to be lesser men who accepted their subordinate role without question. We may be clear that his policy expressed his own views. There was an encounter at one of the conferences between Philip and King John which occurred between Boutavent and Gaillon, when the two kings were 'face to face for an hour, no one except themselves being within hearing', a brief comment but one which allows a sudden and vivid insight into the personal nature of thirteenth-century diplomacy.

Of course Philip took counsel, and made a point of doing so, but he was too independent a man to be dominated by another. And though inclined to prefer diplomatic solutions, he was a good enough warrior to win respect; as William the Breton said 'his arm was powerful in the use of weapons'. Bouvines was the most important battle of the age, and Philip was the victor. Where the loss of documentary evidence from the earlier period often makes it impossible to be certain that Philip was the innovator or the initiator, a knowledge of his character, his able leadership and his drive, make him far and away the likeliest candidate. One of Philip's major achievements was to shift the balances of an intricate system of government in France in favour of the Capetian monarchy, so that its views were more often heeded, and came to be heeded in areas where that had not previously been the case.

Jim Bradbury- Philip Augustus, King of France, 1180-1223xiii

#xii#xiii#jim bradbury#philip augustus king of france 1180-1223#philippe ii#philippe auguste#pierre le chantre#rigord#bertran de born#richard coeur de lion#adèle de champagne#isabelle de hainaut#agnès de france#jean sans terre#battle of bouvines

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

mother likes taking pictures of me getting excited and pointing at things in museums

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

We might know how it ends, but like all good stories it bears repetition. So here it is again, the story of a battle.

Bernard Cornwell, Waterloo: The True Story of Four Days, Three Armies and Three Battles

So I've been getting lots of questions about the significance of the Battle of Waterloo for Britain, France, and indeed Europe.

Great claims have been made as to the legacy of the Battle of Waterloo; but it is not as clear cut as many may claim; for it certainly did not crush all French opposition in a single blow; it did not augur in a century of enduring peace and prosperity across Europe; nor can it claim to have permanently re-established the monarchical system in Europe. Therefore after all the glory, the death and suffering caused on that battlefield, what were its real long term legacies?

For the people living in the vicinity of Waterloo, the utter destruction of the land and of their homes was devastating to their lives, but time soon healed the wounds on the landscape and the abandoned equipment scattered across the battlefields became a virtual treasure trove for the locals as the field of Waterloo was soon at the top of every travellers ‘must see’ list during a sojourn in Belgium. Numbers lived for years selling relics of the battle or became guides to the battlefield as the bloody fields instantly became a top tourist attraction. Every poet and writer in Europe had to visit to witness the scenes of devastation before penning their impressions and publishing to an eager audience, hungry for every new edition.

When they are examined with the benefit of hindsight, battles are rarely accorded the significance given to them. Few become venerated among a nation’s lieux de mémoire, or contribute to the foundation myths of modern nations. Of the battles of the Napoleonic Wars, it is arguable that Leipzig [the 1813 battle lost to the Allies by French troops under Napoleon] has its place in the rise of German nationalism, even if its real importance was greatly exaggerated and mythologized by 19th-century cultural nationalists. In Pierre Nora’s magisterial study of France, only Bouvines, in 1214 [which ended the 1202–14 Anglo-French War], makes the cut. Waterloo, unsurprisingly, does not figure.

Yet at the time Waterloo was hailed in Britain as a battle different in scale and import from any other of the modern era. It had, it was claimed, ushered in a century of peace in continental Europe. It had brought to a close, in Britain’s favour, the centuries-old military rivalry with France. And it had ended France’s dream of building a great continental empire in Europe, while leaving Britain’s global ambitions intact. If the Victorian age could be claimed as ‘Britain’s century’, it was her victory over Napoleon that had ushered it in. Britain, it seemed, had every reason to celebrate, every reason to claim Waterloo as its own.

To some extent Britain’s response was justified; it was a victory that positioned the country favourably, bolstering its global ambitions and helping to create the conditions for the economic success that lay ahead in the Victorian era. Having laid the final, decisive blow on Napoleon, Britain could command a leading role in the peace negotiations that followed and thus shape a settlement that suited its interests. While other coalition states claimed back sections of Europe, the Vienna Treaty gave Britain control over a number of global territories, including South Africa, Tobago, Sri Lanka, Martinique and the Dutch East Indies, something that would become instrumental in the development of the British Empire’s vast colonial command. It is not surprising then that in other parts of Europe, Waterloo - though still widely acknowledged as decisive - is generally accorded less significance than the Battle of Leipzig.

If Waterloo was Britain’s greatest military triumph, as it is often feted, it surely does not owe that status to the battle itself. Military historians generally agree that the battle was not a great showcase of either Napoleon’s or Wellington’s strategic prowess. Indeed, Napoleon is commonly believed to have made several important blunders at Waterloo, ensuring that Wellington’s task of holding firm was less challenging than it might have been. The battle was a bloodbath on an epic scale but, as an example of two great military leaders locking horns, it leaves a lot to be desired.

The short term significance in the aftermath of the Battle of Waterloo marked the end of Napoleon’s storied military career. He reportedly rode away from the battle in tears. Though he emerged victorious, the Duke of Wellington later reflected on the the horrific costs of that victory: “My heart is broken by the terrible loss I have sustained in my old friends and companions and my poor soldiers. Believe me, nothing except a battle lost can be half so melancholy as a battle won.” Wellington went on to serve as British prime minister, while Blucher, in his 70s at the time of the Waterloo battle, died a few years later.

Waterloo’s long term significance must surely be the role it played in achieving lasting peace in Europe. Wellington, who did not share Napoleon’s relish for battle, is said to have told his men, “If you survive, if you just stand there and repel the French, I’ll guarantee you a generation of peace”. Perhaps the lesson of this historic battle the nations of Europe which fought as foes that day need to forget these old sores and celebrate together; recognising that it did force Europe to acknowledge that it must find a new path of reconciliation and accord. This road has been far from smooth, but each time it has failed, a greater understanding of the need for the European states to work more closely together has emerged from the ashes.

Ultimately this is the truly significant importance of Waterloo.

#cornwell#bernard cornwell#quote#waterloo#battle of waterloo#wellington#napoleon#britain#france#prussia#europe#germany#battle#war#napoleonic war#politics#peace#military history#history

83 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The kingdom of France after the battle of Bouvines, 13th century.

by @LegendesCarto

67 notes

·

View notes

Text

Philippe II:

Won the Battle of Bouvines. Overall a pretty cool dude.

Philippe IV:

le gars est tellement sexy que c'est son nom ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

(translation: the guy is so sexy it's in his name *shrug emoji*)

Dates indicated are dates of reign.

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

https://www.tumblr.com/medievalistsnet/734648962108260352/the-battle-of-bouvines-1214-medievalistsnet?source=share

1200s was a crazy year in battles *chuckles*

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

Same anon who asked about the Scot/Port alliance AU thing. What about Wales and Portugal as allies?

Hi, Rains' anon! Thank you for coming by!

I think with Wales we bump into the same problem as with an alliance with Scotland instead of England. The thing that made the Anglo-Portuguese friendship begin and evolve was England's participation in the second crusade and its general seafaringness, which neither Scotland nor Wales had. It was the English that, while on route to Jerusalem, accidentally crashed into Portugal while they were in the middle of their fight against the islamic taifas, so if the Welsh couldn't spare the men to fight for the pope, that point of connection would never happen.

BUT LET'S IMAGINE SOMETHING ELSE.

I could maybe see this happening in two ways: 1) much earlier, maybe prior to the Roman conquest, or 2) much later, if the English never help Portugal in their reconquista and by the time Owain Glyndŵr rolls around he maybe sends an ambassador to sign an alliance with the Portuguese. Both of these are very unlikely, but let's play with it, let's say it could happen.

In scenario 1, the Celtic tribes in Wales could possibly have sent a mission to the Celtic tribes in Galicia and maybe possibly to the Lusitanos further south. This one is unlikely because research points to the Celtic tribes being so different from one another that to bring them all together against the much more powerful and much more disciplined Roman army would be near impossible due to their in-fighting. Maybe they could have exchanged a few princesses, made a few marriages, sent an army and horses here and there, but they would ultimately fall into Roman hands. From what little I could gather on the internet (I am no professional historian), both the Lusitanos in Hispania Ulterior and the Celtic tribes in Western Britannia were finally assimilated around the same time, between 20 and 60 a.d. in the 1st century. So even if they had allied then, it would still fall apart.

In scenario 2, the more interesting one, we would have to consider that Portugal never had any ties to the English and that English history happened without any ties to the Portuguese either.

There was a lot of trade that happened between these two, specially in a time when England and France were at constant war against one another, and Castile often allied with France against England. So fruits, furs, leather, salt, all of that was being imported into England from Portugal. We have to picture an England from 12th century onward that would be extremely isolated, aggressive, ill-fed and ill-dressed. They would depend too much on their trade with the County of Flanders, as well as maybe forced into an alliance with the Nordics, probably Denmark. The English population would suffer as well with increasing war taxes and the human cost of war.

Portugal, on the other hand, would have to have won its independence from León by itself, and resisted every Castilian attempt to unify Iberia. They would also have a trade connection with the County of Flanders, but to avoid them entering in contact with the English there (in actual history, this triangle between Portugal, England and Flanders was a rich and prosperous trade alignment), Flanders would have to be completely neutral, which would mean that in the 13th century France would be able to take it over. The Treaty of Pont-à-Vendin would ensure France liberty to essentially do whatever it wanted and take whatever territories it pleased, and the Portuguese prince who had married the Countess of Flanders wouldn't have gone to the English for help. The Battle of Bouvines would never take place, and John I of England would never lose Normandy, the Angevin Empire would live a little longer and he wouldn't have to sign the Magna Carta.

An isolated and belligerent Portugal, one that never married João I to Philippa of Lancaster and thus never had the illustrious generation, which held the princes and princesses responsible for Portugal's maritime expansion, would maybe lean more on its alliances with Denmark, and could be receptive of a Welsh delegation seeking help in the beginning of the 15th century. The Portuguese would still have to have dealt with the Berber raids in the south, and maybe that could give them the naval war experience needed to aid the Welsh.

Portugal is also a mountainous country, so guerilla fighting against a bigger army in a rocky place seems to be right up their alley.

It is likely that the English would still win against Owain Glyndŵr in the end, but in the case they didn't, that the Portuguese proved to be the decisive factor that won Wales its independence, they could have a long and profitable history together. With Welsh wool bring traded for the goods Portugal had to offer.

With the English and the French still fighting the Hundred Years War, and the Ottomans still taking Constantinople, Portugal would still go out to sea and find a new route around Africa. Maybe it would take them longer without Prince Henry the Navigator, but with the Castilian Jewish expulsion at the end of the 14th century, they would still end up in Portugal and bring their knowledge and experience with them.

And with Antwerp in French hands, Portugal would have to invest in itself to be able to process and refine all the goods it was bringing from overseas and then Lisbon would be the biggest trade center in Europe (even bigger than it actually was), outshining Venice. That, added to its lone wolf stance having had no help to ascertain its independence and security, would probably make it an aggressive, self-sufficient country, impossibly rich and arrogant.

The power axis of Europe would maybe be more distributed. With both edges of it, Portugal and the Ottomans, controlling the flow of spices in a long cold war of sorts.

France would divide the Flemish region with the HRE, England would be even more isolated and maybe even impoverished, having to lean even heavier into piracy and suffering harsher consequences for it without the Anglo-Portuguese Alliance to lean back on.

Wales would probably prosper, but it would be too reliant on Portuguese naval help and commerce.

And since Castile would still get its share of the world because Portugal would still be arrogant enough to snub Columbus and Magellan, adding to the fact that the Ottomans would still finance the Moroccans against Portugal, Portugal would still fall to its own hubris eventually. And when it does, the Welsh would be on their own with a hungry neighbor by their side 👀

#asks#alternative history#this was so fun! I love thinking about this stuff!#thank you for sending this ask!!

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

being nice to king john

You know, considering my final history exam is tomorrow, I think I’ll be nice to King John for once. I mean we’re all very used to laughing at him and referring to him as to worst. to the point even his father gave him a rather horrible nickname, but does he really deserve such insult? Why is it we never hear of how John wasn’t all that bad? There are indeed worse.

The main downfall of John comes from the failure at the Battle of Bouvines, which is understandable, as nobody likes losing a war, not even France themselves as evident with the Treaty of Versailles, however, this does not mean we act in a similar fashion. John was also not the worst warrior, I mean just look at how the Tudors attempted to take France (thank you Mary). John tried his best, and I know that you, reader, have not tried. The attempt was also worth more, as to not try was to be considered lesser than a peasant, to try is to be bad but remembered, and to succeed was the ultimate checkpoint of being a good king, but last time I checked, France is still on the map and only ever left once back in 1940.

The battle’s failure then led to some rather angry barons, which led to them making poor John sign the magna carta, which he then ignored because I mean obviously. it has almost as many articles as the bible has books (63 articles compared to 66 books of the bible) how is one man supposed to remember all of it and also agree to it, especially some random garbage like respect the Welsh. Don’t forget, only four of these articles are upheld in England to this day, which pretty much shouts out loud as how much of it was a waste of paper. He was also quite smart to sign then ignore rather than not sign, as not sign was an imminent red flag that signals “let’s kill this evil guy” and so what he did was steer death away until it comes back as dysentery. This is a rather outstanding move meant for an intelligent man.

John has done good things too... I can’t remember what though because I don’t even know this man, I’m just a buffoon going off of what I remember from school.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

La Bataille de Bouvines by Horace Vernet (Galerie des Batailles, Palace of Versailles).

#battle of bouvines#bouvines#philip ii#philip augustus#france#flanders#flemish#holy roman empire#kingdom of france#knights#french#history#europe#european#medieval#art#middle ages#holy roman emperor#otto iv#versailles#horace vernet#holland#brabant#burgundy#england#lorraine#normandy#german#montmorency#limburg

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Events 7.27 (before 1900)

1054 – Siward, Earl of Northumbria, invades Scotland and defeats Macbeth, King of Scotland, somewhere north of the Firth of Forth.

1189 – Friedrich Barbarossa arrives at Niš, the capital of Serbian King Stefan Nemanja, during the Third Crusade.

1202 – Georgian–Seljuk wars: At the Battle of Basian the Kingdom of Georgia defeats the Sultanate of Rum.

1214 – Battle of Bouvines: Philip II of France decisively defeats Imperial, English and Flemish armies, effectively ending John of England's Angevin Empire.

1299 – According to Edward Gibbon, Osman I invades the territory of Nicomedia for the first time, usually considered to be the founding day of the Ottoman state.

1302 – Battle of Bapheus: Decisive Ottoman victory over the Byzantines opening up Bithynia for Turkish conquest.

1549 – The Jesuit priest Francis Xavier's ship reaches Japan.

1663 – The English Parliament passes the second Navigation Act requiring that all goods bound for the American colonies have to be sent in English ships from English ports. After the Acts of Union 1707, Scotland would be included in the Act.

1689 – Glorious Revolution: The Battle of Killiecrankie is a victory for the Jacobites.

1694 – A Royal charter is granted to the Bank of England.

1714 – The Great Northern War: The first significant victory of the Russian Navy in the naval battle of Gangut against the Swedish Navy near the Hanko Peninsula.

1775 – Founding of the U.S. Army Medical Department: The Second Continental Congress passes legislation establishing "an hospital for an army consisting of 20,000 men."

1778 – American Revolution: First Battle of Ushant: British and French fleets fight to a standoff.

1789 – The first U.S. federal government agency, the Department of Foreign Affairs, is established (it will be later renamed Department of State).

1794 – French Revolution: Maximilien Robespierre is arrested after encouraging the execution of more than 17,000 "enemies of the Revolution".

1816 – Seminole Wars: The Battle of Negro Fort ends when a hot shot cannonball fired by US Navy Gunboat No. 154 explodes the fort's Powder Magazine, killing approximately 275. It is considered the deadliest single cannon shot in US history.

1857 – Indian Rebellion: Sixty-eight men hold out for eight days against a force of 2,500 to 3,000 mutinying sepoys and 8,000 irregular forces.

1865 – Welsh settlers arrive at Chubut in Argentina.

1866 – The first permanent transatlantic telegraph cable is successfully completed, stretching from Valentia Island, Ireland, to Heart's Content, Newfoundland.

1880 – Second Anglo-Afghan War: Battle of Maiwand: Afghan forces led by Mohammad Ayub Khan defeat the British Army in battle near Maiwand, Afghanistan.

1890 – Vincent van Gogh shoots himself and dies two days later.

0 notes

Text

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Great Seal of King John of England (reigned 1199 – 1216).

John was the youngest child of Henry II. He was nicknamed “Lackland”, for it seemed as though he would inherit nothing. He rebelled against his father and against Richard I, who by 1189 was his only surviving brother, while he was away on the Third Crusade. When he returned, John begged his forgiveness, and was given it. Richard died in 1199, upon which John took the throne, although his nephew, Duke Arthur I of Brittany, had a better claim.

To safeguard his enormous continental territories, John signed a treaty on soft terms with King Philip II of France. His barons scorned him for this, giving him the nickname “Softsword”. Not long after that, John had his marriage annulled so he could marry the 13-year-old Isabella of Angoulême.

France invaded the English territory of Normandy in 1202. John won a brilliant victory at Mirebeau in 1203, also capturing his nephew, who was fighting on the opposite side. Arthur disappeared under mysterious circumstances, quite likely murdered by John. This was another blow to his reputation.

Mirebeau was his last success on the continent. By 1204, John had lost most of the territory that Richard I had gained. He returned to England, where he imposed heavy taxes to raise enough money to reconquer the traditional Plantagenet lands on the continent.

In 1205, the Pope chose Stephen Langton to become the new Archbishop of Canterbury. The king strongly disagreed with this, and seized all the revenues of Canterbury and forced the monks into exile. The Pope suspended all church services in England, except for baptisms and hearing the confessions of the dying; John retaliated by seizing Church property. The Pope then excommunicated him, which his enemies took as an invitation to rebel against him. In 1211, the Welsh rose against him, the Irish and Scots were restless, and there were rumours of plots among the English barons. The Pope called on Philip II to depose John.

Philip prepared his army, but John prevented the invasion by declaring that he would become the Pope's vassal and pay him 1,000 marks a year – meaning that Philip would be invading the Pope's own property, so he had to back down. John accepted Langton as Archbishop, and the interdict was lifted in 1214. But this did not make everything fine – Langton, and many others, disapproved of John's gift of England to the Pope.

John now went back to France to try and recapture the lands he'd lost, but failed. When he returned to England, his position was even weaker than before. Rebellious barons began quoting Henry I's Charter of Liberties, which he'd issued over a century earlier. But John rejected the barons' demands, and ordered the confiscation of their estates. In response, the barons marched on London and plundered the city. John was forced to arrange a truce.

Magna Carta was signed on June 15th, 1215. It stated rights that were already considered to exist, thus limiting the powers of the king. (However, because it was a peace treaty, the barons had no way of enforcing it except by waging war on him.) The treaty contained two important principles: the right to trial bu jury, and the assurance that no tax would be raised “unless by common council of our kingdom”.

The Pope (now on John's side) urged him to reject the treaty; the barons looked to Louis Capet, the son of Philip II, for help. In May 1216, Louis entered London unopposed. While crossing the Wash with his army, John managed to lose his entire baggage train and his crown, and shortly afterwards he died of apoplexy, brought on by gorging himself on peaches and cider.

#history#military history#christianity#catholicism#treaty of le goulet#french invasion of normandy#battle of mirebeau#interdict of 1208#welsh uprising of 1211#anglo-french war (1213-14)#battle of bouvines#first barons' war#magna carta#britain#angevin empire#england#france#wales#ireland#scotland#king john#philip ii#pope innocent iii#louis viii

24 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Battle of Bouvines

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Children's Crusade: Real Story of the Tragic Event

Children's Crusade: Real Story of the Tragic Event

Children's Crusade: Real Story of the Tragic Event

Category Main

Description:

Get your free trial of MagellanTV here: https://try.magellantv.com/kingsandgenerals. It’s an exclusive offer for our viewers: an extended, month-long trial, FREE.

TopTrengingTV Hunting the most trend video of the moment, every hour every day 24/7.

⚙️

Published At: 2021-02-07T13:59:47Z

Tags: [‘top trending tv’,…

View On WordPress

#age#animated documentary#animated historical documentary#bouvines#children&039;s crusade#Children&039;s Crusade: Real Story of the Tragic Event#christianity#crusaders#crusades#decisive battles#documentary film#Early Muslim Expansion#frederick#full documentary#golden#hashashins#history channel#history documentary#history lesson#Islam#islamic#jerusalem#king and generals#kings and generals#main#Medieval#middle ages#military history#most viewed youtube video#philip

1 note

·

View note