#adèle de champagne

Text

Blanche de Navarre

A month after Marie's death in March 1198, a throng of barons accompanied nineteen-year-old Thibaut III to Melun, where he did homage for his lands and was knighted by the king. A year later the young count married Blanche of Navarre, the younger sister of Richard the Lionheart's widow Berengaria. Attending the magnificent ceremony in Chartres cathedral were the dowager queens Berengaria of England and Adèle of France (Thibaut's aunts), as well as many prelates and barons. The jubilation was short-lived, however, for Thibaut died in May 1201 while preparing to lead the Fourth Crusade. He left twenty-year-old Blanche a widow in the last week of her second pregnancy. For the next twenty-one years she would guide the county through the most perilous internal and external threats it had yet faced.

Whereas countess Marie clearly had possessed the requisite qualifications to act as regent — intimate connections with the Capetian and Plantagenet royal families, eleven formative years preparing to be countess, and sixteen years as countess consort — countess Blanche must have seemed singularly unsuited for such a role. A Navarrese speaker with a strong religious temperament, she had little experience as countess. She also faced an extraordinary challenge from the start: were her children, in fact, the legitimate heirs to the county? In 1190, when the unmarried Henry II left on the Third Crusade, the barons had sworn to accept his younger brother Thibaut III as count if Henry himself did not return. No one had anticipated that Henry would remain overseas seven years, marry there, and have children. Thus it was a legitimate question, in May 1201, whether Henry II's own daughters had better rights to Champagne than his brother Thibaut's infant daughter.

Blanche skillfully mastered a difficult situation. Mindful of king Philip's attempt to seize Flanders in 1191 in the absence of a male heir, she quickly made an alliance with the king the cornerstone of her regency. Within days of Thibaut's death she found Philip at nearby Sens, did homage — the first homage ever rendered by a countess — for her right of wardship and her dower lands, and promised not to remarry without his permission. As security for her conduct, she surrendered two castles bordering the royal domain (Bray-sur-Seine and Montereau-faut-Yonne) and her oneyear-old daughter to be raised at the royal court. Several days later the birth of a son, Thibaut IV, confirmed the soundness of her strategy: he was born heir apparent under royal protection.

Theodore Evergates - Aristocratic Women in Medieval France

#xii#xiii#blanche de navarre#countess of champagne#history of champagne#thibault iii de champagne#adèle de champagne#bérengère de navarre#philippe ii#thibault iv de champagne#theodore evergates#aristocratic women in medieval france

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

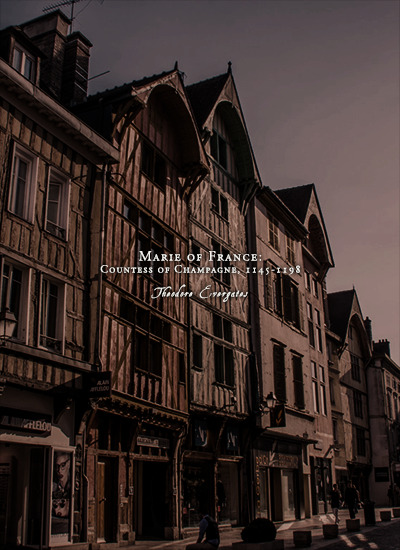

Favorite History Books || Marie of France: Countess of Champagne, 1145–1198 by Theodore Evergates ★★★★☆

Countess Marie of Champagne is known today primarily as a literary patron, notably of Chrétien de Troyes, who famously announced in his prologue to Lancelot, that since she “wished” him to tell the tale, he complied with her “command.” From that and several other mentions by contemporary writers, Marie has been cast as the animator of a “court of Champagne.” It is indeed ironic that, with few explicit references to her patronage, Marie is now cited more frequently than her husband, Count Henri the Liberal (1152−81), a commanding figure in his time who made the county of Champagne one of the premier principalities of northern France and whose intellectual interests are amply attested. Marie in fact was more than a cultural patron. She was ruling countess of Champagne for almost two decades in the 1180s and 1190s, initially during Count Henry’s absence overseas, then as regent for her son Henri II and as co-lord with him during the Third Crusade and his subsequent residence in Acre. From the age of thirty-four until her death at fifty-three she ruled almost continuously, presiding at the High Court of Champagne and attending to the many practical matters arising in a vibrant principality of the late twelfth century. She acted with the advice of her court officers but without limitation by either the king or a regency council. If Henri the Liberal’s crowning achievement was to create the county of Champagne as a dynamic, prosperous state, Marie’s was to preserve it in the face of several existential threats.

Historians of Capetian France have yet to appreciate the frequency and significance of wives acting in the absence of their husbands and during the minority of inheriting sons. That was a common family practice; only in a wife’s absence was a guardian or regency council appointed. During Countess Marie’s lifetime two royal regencies were necessitated by the absence of a resident queen while the king traveled overseas: when her mother, Eleanor of Aquitaine, accompanied Louis VII on the Second Crusade, and when Queen Isabelle died in childbirth shortly before Philippe II left on the Third Crusade. In each case the king designated regents as guardians of the realm. Louis appointed Abbot Suger of St-Denis and the seneschal Raoul of Vermandois “for the custody of the realm” (de regni custodia), said Eudes of Deuil, while Philippe enacted an ordinance (ordinationem) granting his uncle Guillaume, archbishop of Reims, and his mother, Adèle, the dowager queen, limited authority during his absence.³ Countess Marie, however, like most wives of princes, barons, and knights, was not burdened by a regency council. Her decisions at court and her letters patent carried the same authority as those of her husband and son, without mention of any provisional standing. Although she often associated her underage son with her in letters patent, she alone exercised the full plenitude of the comital office, even during Count Henri II’s extended stay in Palestine, and she sealed in her own name as countess of Troyes (her only title).

Marie’s life beyond her role as literary patron and ruling countess encompassed an extensive network of family relationships, for she was connected by birth and marriage to two of the most prominent royal families of twelfth-century Europe. As the daughter of Louis VII and Eleanor of Aquitaine, Marie acquired through their second marriages numerous royal half-siblings whom she regarded as brothers and sisters: Louis’s children Marguerite of France and King Philippe II, and Eleanor’s sons Henry, Geoffroy, and Richard. Even more directly important in providing a nexus of personal support for her rule in Champagne were Henry the Liberal’s well-placed siblings: the royal seneschal Count Thibaut V of Blois (1152–91), Archbishop Guillaume of Sens and Reims (1168–1202), and Queen Adèle (1160–79, d. 1206). Marie’s seal inscribed her dual identity: “Daughter of the King of the Franks, Countess of Troyes.”

#historyedit#litedit#marie of france#house of capet#house of blois#medieval#french history#european history#women's history#history#nanshe's graphics#history books

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

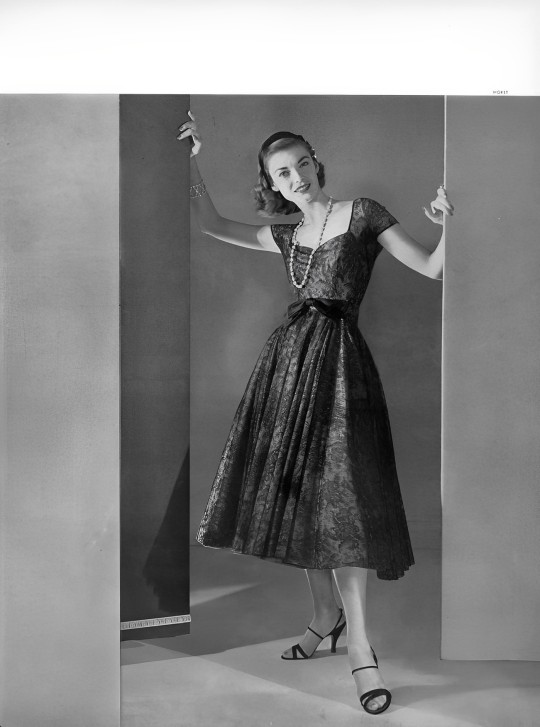

US Vogue December 1954 ❤️❤️❤️❤️❤️

An unidentified model, in a dress of sparkling champagne taffeta, beautifully puffed with black lace. By Adele Simpson. Stockings in this case—sandalfoot, of course—a new pale beige by Holeproof.

Un modèle non identifié, dans une robe de taffetas champagne éclatant, magnifiquement soufflé avec de la dentelle noire. Par Adèle Simpson. Bas dans ce cas-sandalfoot, naturellement-un nouveau beige pâle par Holeproof.

Photo Horst P. Horst

vogue archive

#us vogue#december 1954#fashion 50s#spring/summer#printemps/été#1955#american style#adele simpson#holeproof#robe en taffetas#taffeta dress#horst p. horst

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Adèle and Noémie are drinking champagne straight from the bottle in the middle of the afternoon on the red carpet of the Golden Globes and if that’s not a mood I don’t know what is

#that’s so french too lmao#i mean i guess it’s champagne ?#portrait de la jeune fille en feu#portrait of a lady on fire#noémie merlant#adèle haenel#gg 2020

126 notes

·

View notes

Text

Le pumpkin autumn challenge ne se terminera que le 30 novembre prochain… Pourtant, je ne peux m’empêcher de déjà penser à mes lectures cocooning de Noël. Ce sont des romans qui se déroulent pendant les fêtes ou sous la neige, des romances pour la plupart. Bref, des livres qui font du bien, d’auteurs que j’ai déjà lu et qui ne devraient pas me décevoir 🙂 Ma PAL de décembre est donc presque déjà prête. Au programme : des flocons, de l’amour, de l’humour et des cadeaux de Noël !

En anglais (VO), j’ai évidemment choisi de sélectionner SNOW FALLING, le roman qui est présent dans la série Jane the Virgin. Ça fait déjà un moment que j’ai fini la série mais ce livre est toujours dans ma pile à lire et je pense que le lire en décembre serait parfait. La couverture est un peu kitsch mais c’est celle qui est présente dans la série. Voici le résumé (qui parlera bien entendu plus au fan de la série ^^) :

“Fans of the show will undoubtedly enjoy the chance to read Jane’s book in real life.” —Entertainment Weekly

It’s been a lifetime (and three seasons) in the making, but Jane Gloriana Villanueva is finallyready to make her much-anticipated literary debut!

Jane the Virgin, the Golden Globe, AFI, and Peabody Award–winning The CW dramedy, has followed Jane’s telenovela-esque life—from her accidental artificial insemination and virgin birth to the infant kidnapping and murderous games of the villainous Sin Rostro to an enthralling who-will-she-choose love triangle. With these tumultuous events as inspiration, Jane’s breathtaking first novel adapts her story for a truly epic romance that captures the hope and the heartbreak that have made the television drama so beloved.

Snow Falling is a sweeping historical romance set in 1902 Miami—a time of railroad tycoons, hotel booms, and exciting expansion for the Magic City. Working at the lavish Regal Sol hotel and newly engaged to Pinkerton Detective Martin Cadden, Josephine Galena Valencia has big dreams for her future. Then, a figure from her past reemerges to change her life forever: the hotel’s dapper owner, railroad tycoon Rake Solvino.

The captivating robber baron sets her heart aflame once more, leading to a champagne-fueled night together. But when their indiscretion results in an unexpected complication, Josephine struggles to decide whether her heart truly belongs with heroic Martin or dashing Rake.

Meanwhile, in an effort to capture an elusive crime lord terrorizing the city, Detective Cadden scours the back alleys of the Magic City, tracking the nefarious villain to the Regal Sol and discovering a surprising connection to the Solvino family.

However, just when it looks like Josephine’s true heart’s desire is clear, danger strikes. Will her dreams for the future dissolve like so much falling snow or might Josephine finally get the happy ever after she’s been dreaming of for so long?

Ensuite, des flocons comme promis avec trois romans Feel-good qui se déroulent en hiver. La suite de la trilogie de Sarah Morgan que j’ai débuté l’année dernière et le nouveau livre de Clarisse Sabard dont la couverture est super mignonne et 100% en thème avec l’hiver. Pour ceux qui aimeraient se laisser tenter par Sarah Morgan, voici mon avis sur le tome 1.

Passons maintenant à un roman pour sourire et se nourrir par procuration, également d’une auteure #cocoon que beaucoup de lectrices adorent : Emily Blaine. J’ai acheté La crêperie des petits miracles d’occasion il n’y a pas longtemps et j’ai très envie de retrouver son adorable plume.

Adèle a tout quitté : Paris, le grand restaurant dans lequel elle travaillait, la pression constante des cuisines, la misogynie du chef qui la bridait chaque jour un peu plus. Pour échapper au burn out, elle s’est réfugiée chez une amie de sa grand-mère, à Saint-Malo. Dans la crêperie de Joséphine, elle reprend petit à petit ses marques, restant loin des cuisines mais s’occupant du service et des clients. Dans ce cocon gourmand et chaleureux, elle devient celle à qui l’on demande des conseils d’écriture pour un discours municipal, un dossier de candidature ou une lettre de réclamation. Alors, quand la crêperie est menacée de fermeture, Adèle est prête à tout pour empêcher que ce bastion d’humanité et de bienveillance ne disparaisse. À tout, y compris à convaincre Arnaud Langlois, puissant homme d’affaires fraîchement divorcé, de devenir son associé.

Et enfin, parce qu’une PAL de décembre sans livre sur Noël n’en est pas une, voici deux livres qui mettent clairement cette fête familiale à l’honneur. Sapin, guirlandes et cadeaux en vue… Noël Actually et Vous faites quoi pour Noël de Carène Ponte.

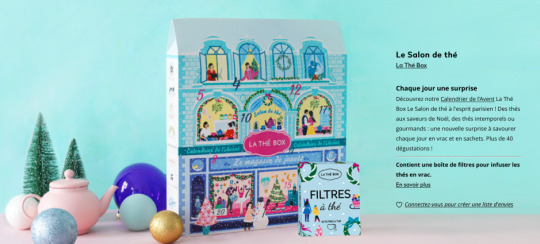

De quoi passer l’Avent comme il faut : avec des bons livres et du thé ❤ D’ailleurs en parlant de thé, j’ai pour la première fois commandé un calendrier de l’avent spécial thé. J’ai tellement hâte d’être en décembre pour goûter toutes ces petites merveilles. Si ça vous intéresse, je l’ai commandé sur LA THE BOX où ils proposent différents calendrier de l’avent en plus de leurs abonnements. Trop bien, non ? 🙂

Ma pile à lire de décembre #XMAS2020 Le pumpkin autumn challenge ne se terminera que le 30 novembre prochain... Pourtant, je ne peux m'empêcher de déjà penser à mes lectures cocooning de Noël.

0 notes

Text

Adèle Toussaint

Il y a généralement à bord trois ou quatre sortes de voyageuses, que j’ai rencontrées dans tous mes voyages. La première est celle que j’appellerai la poseuse. Celle-là à cause de son rang ou de sa fortune, se croit tellement au-dessus de ses compagnons de route, qu’elle ne daigne apparaître à table que bien rarement. D’ordinaire, elle se fait servir chez elle, occupe seule la cabine-salon, ne daigne échanger quelques paroles qu’avec le capitaine, a l’air de ne pas même voir les autres personnes, passe deux ou trois heures à sa toilette, et ne fait son apparition que vers les deux heures, toujours accompagnée d’une femme de chambre, portant son manteau ou son flacon. La seconde appartient à la classe appelée cocotte. Celle-là change de robes deux ou trois fois par jour, rit et parle très haut, est généralement du dernier bien avec le second et le lieutenant, prend des airs d'ingénue un jour, et, le lendemain, dit des choses qui feraient rougir un dragon; passe sa journée étendue sur la dunette, les cheveux au vent, sans perdre une occasion de montrer son pied et sa jambe, fait la charge des autres femmes, chante des airs d'opéra quand la nuit vient, danse et valse les jeudis et dimanches, reste sur le pont jusqu'à une heure du matin avec les officiers et les passagers de son choix, et défraie la traversée par une foule d'épisodes plus ou moins piquants. La troisième est la voyageuse sérieuse ou artiste, échangeant des paroles avec tous sans se lier avec personne, montant sur le pont, quand tout le monde en descend, pour jouir d'un beau lever du soleil ou d'un splendide clair de lune, arrangeant sa journée pour se garder quelques heures d'étude ou d'isolement, faisant sa correspondance, lisant, brodant, vêtue simplement, mais chaussée et gantée avec soin, ne se mêlant d'aucuns cancans, ne recherchant ni ne fuyant la société de ses compagnons de route, et ne désirant enlever aucun cœur, passant calme au milieu de toutes ces petitesses et de toutes ces vanités, s'attirant le respect de chacun, et souvent plus entourée à la fin du voyage que celles qui ont désiré l'être. C'est dans cette classe, Mesdames, que nous vous conseillons de vous ranger, si jamais il vous arrivait de voyager seules, ce que nous ne vous souhaitons pas. Dès le second jour de route, chacun a déjà ses sympathies et ses antipathies. On échange quelques saluts, voire même quelques phrases. Le surlendemain, les conversations s'entament. Il y a le passager communicatif, qui ne demande qu'à s'épancher, et qui vient vous raconter toutes ses histoires de famille ; il ne vous fait grâce ni d'une tante ni d'un cousin, et interrompt de temps à autre sa narration pour aller chercher les photographies de son père, de sa mère, de ses sœurs, frères et cousines. Il faut absolument que vous connaissiez jusqu'à la nourrice de son neveu. Ensuite, vient le passager mélancolique, un beau garçon qui pose pour un amour malheureux, tout en envoyant des regards langoureux aux dames qu'il attendrit, et qui voudraient toutes déjà le consoler. Il exhibe aussi à certains jours le portrait de son ingrate, qu'il conserve nuit et jour sur son cœur. Celui-là a toutes les chances pour être adoré, car l'obstacle est un attrait puissant, et chaque fille d'Eve rêve en secret de guérir ce pauvre amoureux de sa funeste passion. Après cela, nous avons le passager boute-en-train, ayant toujours un refrain aux lèvres, la moustache retroussée, le pantalon à la hussarde, payant presque tous les jours du Champagne aux officiers et faisant la cour à la cocotte et à la femme de chambre de la poseuse. Enfin, le passager maussade, toujours mécontent de la nourriture, de la marche du navire, des manières des officiers, de la tenue des femmes, du temps, qu'il trouve tantôt trop chaud et tantôt trop froid. Il cause à voix basse dans un coin comme un conspirateur, et cherche à recruter autour de lui tous les mécontents du navire. C'est généralement lui qu'on voit apparaître le matin, coiffé du bonnet de coton classique, souvenir de son ancien état, probablement.

0 notes

Text

As an historian and medievist I really would like to meet Aliénor d'Aquitaine and Philippe Auguste...

Aliénor d'Aquitaine was important in France and in England. Queen twice because she married Louis VII of France and after Henri II Plantegenet. She was duchess of Aquitaine and countess of Poitiers. She participated in the second crusade and she was the patron of literature. She was the most important woman at this time.

Philippe Auguste was the son of Louis VII de France and Adèle de Champagne. He became king of francs in 1180. In 1204 he decided to change the name Rex Francorum (King of francs) to Rex Franciæ (King of France). He participated in third crusade with Richard Ist of England. He won a lot of battles and his reign was long (42 years). He was famous because in 1214 he won the battle of Bouvines against John Lackland.

I could write a lot of things about them. Maybe one day.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Orient

Lavoûte-Chilhac, Mardi 26 février 2019

Orient

Ensemble de pays de l'Ancien Monde situés à l'est (orient) par rapport à la partie occidentale de l'Europe. (Il englobe toute l'Asie, une parte de l'Afrique du Nord-Est, avec l'Égypte et, dans une acception ancienne, une partie même de l'Europe balkanique.)

Répartition géographique

Les États du Proche-Orient ou levantins bordant la mer Méditerranée : Chypre, Égypte, Irak, Israël, Jordanie, Liban, Syrie et Turquie.

Nous avons passé Mouna et moi, la soirée chez Titou avec sa smala suffisamment orientalisée par six années passées par sa mère Geneviève aux commandes du lycée français de Beyrouth, dont nous fîmes la connaissance, ainsi que de Claire libanaise, sa secrétaire là-bas, venue passer une semaine de vacances auprès d'elle.

Nous nous sommes réunis autour d'une crêpes-partie sympa et trinquant au champagne; pour notre confort Mouna et Claire échangèrent leurs souvenirs en français que Claire parle à la perfection

Avec les gens ayant voyagé les conversations sont faciles et les échanges positifs, nous y associâmes Isabelle la maman des petites-filles de Geneviève : Adèle et Emma , 7 et 5 ans, dégourdies qui nous entraînèrent dans un jeu des sept familles où Mouna tricha tant qu'elle nous mit la pile.

La triche est orientale, Geneviève et moi ne l'avons pas contractée et Claire ne l'a pas affichée, elle m'a parue à ce niveau plus occidentalisée que ma moitié.

Nous nous retrouverons aujourd'hui à la maison pour le café, afin de permettre à Mouna de présenter ses œuvres à nos nouvelles relations, ce n'est pas si souvent que Lavoûte s'orientalise...

Que l'on ne vienne pas nous dire que nous ne faisons pas tout pour sortir Lavoûte de son trou.

C'est toujours pour Mouna, un plaisir.

0 notes

Text

Marie de France

For six years, from March 1181 to May 1187, Marie exercised the comital office as regent for her son Henry (II). She did so vigorously and alone, without restriction by a regency council. In the great hall of her palace in Troyes, which served as the political and administrative center of the county, as well as in her other castle towns, Marie sat with a small council of barons and administrative officers to discharge all the routine business of medieval rulers: receiving petitioners, arbitrating and settling disputes, making benefactions to churches, confirming private transactions, receiving homages, confiscating fiefs and granting new ones. Since her acts continued to be drawn up by the same chancery officials who had served her husband, they remained the same in form and content. With the notable exception of appointing a new marshal, Geoffroy of Villehardouin, in 1185, she made no discernible changes in her husband's officers or policies. Although feudal tenure by women apparently increased precisely during her rule, we cannot say whether she fostered that practice. Her court, however, was perceived as being receptive to women, several of whom sought her confirmations at critical junctures in their lives.

In 1181 Marie found herself widowed with four young children — Henry II was fifteen, Marie seven, Scholastique five or six, and Thibaut III only two. She considered marrying the recently widowed Philip, count of Flanders (1168-91), the son of her husband's old friend and crusade companion count Thierry. Philip and Marie were about the same age and well acquainted: a decade earlier he had sponsored the betrothal of her two oldest children, Henry II and young Marie, to the children of his sister Margaret, countess of Hainaut. Philip went so far as to seek a papal dispensation for his marriage to Marie, since they were indirectly related, but then, for unknown reasons, broke off negotiations. Marie, at thirty-nine, seems not to have sought another marriage. Thereafter she was preoccupied with completing the marriages between her children and the children of Margaret and count Baldwin V, who had renewed, broken, revised, then delayed carrying out the marriage contract between his only son and Marie's daughter. Countess Marie called on her in-laws to force the elusive count to deliver the groom; Gislebert of Mons describes the scene at Sens where the countess, the archbishop of Reims, the counts of Blois and Sancerre, and the duke of Burgundy cornered Baldwin, perhaps threatening him, if he did not follow through with the marriage, which finally did take place (January 1186). Marie then trumped Baldwin at his own game by ignoring the second part of the contract and arranging her own son's marriage to the infant heiress of Namur instead of to Baldwin's daughter.

When Henry II (1187-90) assumed the countship, Marie retired to Meaux, probably with her youngest son Thibaut, then eight. The forty-twoyear-old countess could not have imagined that she would ever rule again. But the fall of Jerusalem to Saladin on October 2, 1187 electrified France, and young Henry II was swept up by the wave of enthusiasm for a new crusade to recover the holy city. In May 1190 the unmarried count departed with a large contingent of barons and knights on the Third Crusade, leaving his mother as regent once again. Marie ruled in his absence (he died overseas in September 1197), then continued to rule until her death in March 1198 at fifty-three. In all, she had ruled the county over fifteen years — in her husband's absence, as guardian for her oldest son and then in his absence, and finally in the last months of her life as guardian for her second son, Thibaut.

Although she was countess of Champagne for over thirty years, half of them as ruler, we know little about Marie's life and personality beyond her official acts. She seems to have been close to her half-brothers Geoffroy Plantagenet, for whom she dedicated an altar in Paris, and Richard the Lionheart, with whom she shared Adam of Perseigne as confessor, as well as with her half-sister Margaret, who spent Christmas 1184 with Marie and queen mother Adèle. Perhaps Marie saw her sister, countess Alix of Blois, and her mother, Eleanor of Aquitaine, after her parents were divorced in 1152, but there is no firm evidence of any meeting. For her husband Henry she ordered a sumptuous tomb placed in the center of the church of Saint-Etienne of Troyes next to the comital palace, but she herself chose to be buried at Meaux.

Marie's role as literary patron now seems secure. She could read vernacular French and probably Latin as well, given her education at Avenay, and she had a personal library, although its contents are not known. Chrétien de Troyes and Gace Brulé state that they wrote at her request, and she seems also to have patronized Conon de Béthune and Huon d'Oisy. The collegiate chapter of Notre-Dame-du-Val, which Marie founded in Provins with thirty-eight prebends, seems to have supported not only Chrétien but also his continuator Godfrey of Lagny, as well as the earliest known copyist of Chrétien's romances, Guiot of Provins. Perhaps Marie'sinterest in lyric poetry and romances dates from her married years, for the works she is know to have commissioned as a widow in the 1180s are all translations of religious texts: Psalms (Eructavit), Genesis, and possibly a collection of sermons by Bernard of Clairvaux.

Theodore Evergates - Aristocratic Women in Medieval France

#xii#theodore evergates#aristocratic women in medieval france#marie de france#countess of champagne#history of champagne#henri i de champagne#henri ii de champagne#thibault iii de champagne#marie de champagne#geoffroy de villehardouin#baudouin v de hainaut#adèle de champagne#alix de france#geoffroy plantagenêt#richard coeur de lion#chrétien de troyes#gace brulé

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Philippe Auguste

The Capetian monarchy was an institution, with traditions and restrictions. But the personal element in the medieval period always remained a significant factor. To what extent the government of any individual king was personal is not easy to determine. In general it is true that counsellors could advise, but could not normally decide policy. Others were there to obey the will of the monarch, perhaps to help form it, but not to take over from it. Philip's views were shaped by many influences: by observing his father's work, by his father's advice, by his own education, by the advice he received from counsellors, by the experience of governing, by the views of churchmen, theologians, popes and fellow rulers, but in the end they were his views and could be imposed to the extent of the power of the monarchy at the time. Philip's court and government reflected his own personality. Gerald of Wales pointed out its contrasts with the Plantagenet court, the French king's being more sober as we have seen, more quiet in tone, more proper, with swearing forbidden. Philip brought about significant changes: less reliance on the magnates, a lesser role for his family; a greater place for the selected dose counsellors and for relatively humble knights.

It has been suggested that Philip's intellectual gifts were 'modest', which, although direct evidence is not easily available, seems to conflict with what we know about the king's abilities. He was able to deal with the bright men around him, such as Peter the Chanter. He was able to supervise governmental development and the administration, which needed a considerable grasp of accounting as well as a degree of literacy. His ability to deal with the papacy reveals a clear understanding of legal argument and his rights, and a firm determination to protect them. He was rarely outmanoeuvred by even the cleverest of his opponents. Philip went to war as any leader of his period would, but he was more prepared than most to seek and make peace.

Rigord said that Philip's aim was 'to deliver the weak from the tyranny of the strong', and that 'his first triumph is to see peace re-established'. His tolerance and mild temper puzzled the aggressive Bertran de Born, who thought the French needed a leader and had not found one in Philip, who did not become angry. Bertran preferred the attitude of Richard the Lionheart, for whom 'peace and truce have never been noble'. For Bertran it was a sneer to suggest that Philip liked peace even more than the noted diplomat Archbishop Peter of Tarentais. Bertran had cause to regret his underestimation of Philip, when the king later used his authority to replace Bertran as lord of Hautefort. No doubt that act was executed on the advice of counsellors, and Bertran could further nurse his belief that Philip was 'badly advised and worse guided'.

Philip did in fact at times lose his temper, but usually with some point, as when he chopped down the elm on the Norman border, declaring by actions rather than words that he no longer accepted the Plantagenet stance on their rights to bring the king to the edge of their territories before they would hold discussions. Nor were his diplomatic activities always appreciated by his enemies. He could manoeuvre and manipulate with the best of them; he was the 'sower of discord' according to one English chronicler. To take just one example of his methods: in the conquest of Normandy he knew that Rouen was the key, which afterwards he would need to govern. Therefore he did not simply crush Rouen, and chose to discuss with the leading citizens what they would gain from surrender. If allowed in, he promised: 'I will prove a kind and just master to you.' In modern times he has been called 'a statesman of the first water', 'the first royal statesman in French history' ; it is a reputation which in this country we have somehow failed to recognize.

[..]

Philip was generally modest and unassuming, as we have seen in contrast to Richard the Lionheart both in Sicily and in the Holy Land. Bertran de Born thought the French king presented his deeds in tin-plate rather than in gilt. But Philip was aware of the need to present a regal figure, dignified if not flamboyant: a public face of modesty but a recognition of his own powers. The scene painted by Mouskes of Philip entering a church and praying: 'I am but a man, as you are, but I am king of France', has a deep truth to it. There is also a story of Peter the Chanter telling Philip what were the attributes of an ideal sovereign; Philip replied that he should be contented with the king that he had.

The efforts to show his connection back to Charlemagne demonstrate Philip's effort to bolster the Capetian position. His mother, Adela, and his first wife, Isabella of Hainault, both claimed descent from Charlemagne. His natural son was named Peter Charlot, after the great emperor. And the Carolingian claim seems to have become generally accepted. Innocent III declared: 'it is common knowledge that the king of France is descended from the lineage of Charlemagne'. No doubt there was some weakness in the argument, but William the Breton refers to him as 'the descendant of Charlemagne', and the Welshman Gerald believed that Philip aimed to restore the monarchy to 'the greatness which it had in the time of Charlemagne'.

Philip wished to present an imperial image of French monarchy, hence the use of an eagle on his seal, the label 'Augustus' applied by Rigord, his sister's marriage to two Byzantine emperors, and the raising to the Latin imperial throne of two of his brothers-in-law. The same point was being emphasized when the sword of Charlemagne had been brandished at Philip' s coronation ceremony. As one of the Parisian masters wrote in 1210: 'the king is emperor in his realm'. The royal family was being distanced from other families, however noble; royal power was being set above noble power. It was not just a question of wealth and lands, but of the nature of monarchy, its prestige, its religious and mystical significance. The claimed association with Charlemagne, by the twelfth century a powerful figure in legend as well as a great historical emperor, was an important part of this process.

Philip was a tough-minded individual, he would not otherwise have been such a great king. Those who had experience of dealings with Louis VII found Philip a much harder opponent with more steel in his character. He had tremendous determination, and strong views on basic policies. Before his father's death, while still a teenager, Philip was prepared to rule, issuing charters without his father's consent, reacting against some of his father's policies. Before long he threw off the shackles of his mother and her powerful family, and soon afterwards of the count of Flanders. The English chronicler Howden thought he did it because he 'despised and hated all whom he knew to be familiar friends of his father', which seems a distortion, but at least underlines the point that Philip was of independent mind from the first.

Philip preferred his close counsellors to be lesser men who accepted their subordinate role without question. We may be clear that his policy expressed his own views. There was an encounter at one of the conferences between Philip and King John which occurred between Boutavent and Gaillon, when the two kings were 'face to face for an hour, no one except themselves being within hearing', a brief comment but one which allows a sudden and vivid insight into the personal nature of thirteenth-century diplomacy.

Of course Philip took counsel, and made a point of doing so, but he was too independent a man to be dominated by another. And though inclined to prefer diplomatic solutions, he was a good enough warrior to win respect; as William the Breton said 'his arm was powerful in the use of weapons'. Bouvines was the most important battle of the age, and Philip was the victor. Where the loss of documentary evidence from the earlier period often makes it impossible to be certain that Philip was the innovator or the initiator, a knowledge of his character, his able leadership and his drive, make him far and away the likeliest candidate. One of Philip's major achievements was to shift the balances of an intricate system of government in France in favour of the Capetian monarchy, so that its views were more often heeded, and came to be heeded in areas where that had not previously been the case.

Jim Bradbury- Philip Augustus, King of France, 1180-1223xiii

#xii#xiii#jim bradbury#philip augustus king of france 1180-1223#philippe ii#philippe auguste#pierre le chantre#rigord#bertran de born#richard coeur de lion#adèle de champagne#isabelle de hainaut#agnès de france#jean sans terre#battle of bouvines

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Apple of his father's eye

Whatever Louis's failings in the eyes of his first wife, he later proved a good husband and father. There are no unfavourable comments on his second and third marriages, which both produced offspring. The second marriage, to Constance of Castile, added two daughters to the two by Eleanor. But there is no doubt that when his third wife, Adela of Champagne gave birth in 1165, the God-given son became the apple of his father's eye. Louis resisted the Capetian practice of associating his son in government with him. Perhaps the security of his position made it unnecessary. Perhaps, in 1172, when Henry archbishop of Reims suggested a coronation, and with papal support, Louis thought his seven-year old son too young. Louis had no doubts that Philip should be his heir. In 1179, when ill, Louis called an assembly in Paris. There he announced his intention of having Philip crowned on the feast of Assumption, on 15 August. These plans, however, were dramatically interrupted. Philip went hunting near Compiègne. Chasing a boar, he became lost alone in the woods. Found by a charcoal-burner, Philip was led to safety, but a night in the open, two days without food, and the shock of the whole episode, darnaged his health. The prince became ill to the point where death seemed imminent. The coronation was postponed.

Now Louis conducted himself as the caring father, weeping profusely, sighing night and day, inconsolable. One night the murdered Thomas Becket appeared before him, proc1aiming: 'Our Lord Jesus Christ sends me as your servant, Thomas the martyr of Canterbury, in order that you should go to Canterbury, if your son is to recover.' Louis's counsellors tried to dissuade the ageing king from a journey into the lion's den, but he overrode all opposition and went, accompanied by the counts of Flanders, Guisnes and Louvain, arriving at Dover on 22 August. He was met by Henry II who, whatever his suspicions, escorted Louis to Canterbury and treated him as an honoured guest. Louis spent two days praying, 'a humble and devout suppliant', and then returned home. Philip recovered rapidly and was crowned at Reims on 1 November. The episode added to Louis's pious reputation, though the journey had probably been undertaken less for prestige than from love of his son.

The Norman chronicler, Robert of Torigny, says that in 1179 there were great winds and forecasts of impending calamities. The effort of the journey had been too much for the sixty-year-old monarch. He went into decline, suffering a stroke which left him paralysed and unable to speak. Philip was installed as king and immediately took an active role. Louis VII became no more than 'a spectator in the last year of the reign'. His incapacity was such that his personal seal was taken away. He died in September 1180, with his fifteen-year-old son still recuperating. The father was buried at his own foundation, the Cistercian house of Barbeau. The inscription on his tomb, which Philip may weIl have taken to heart, read:

You who survive him are the successor of his dignity;

You diminish his line if you diminish his renown.

Jim Bradbury - Philip Augustus, King of France, 1180-1223

#xii#jim bradbury#philip augustus king of france 1180-1223#louis vii#philippe ii#father and son#adèle de champagne#constance de castille#aliénor d'aquitaine

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Louis VII and his great vassals

Philip Augustus owed a considerable debt to his father, not least for extending royal authority into the principalities. Louis forged links which brought the great vassals closer to a monarchy which was becoming more than one among equals, establishing the suzerainty of the Capetians. Previously the magnates had rarely attended court, only doing homage, if at all, on their borders, and providing small contingents for military service, if any. Even in the Plantagenet lands, Louis advanced the royal position. Henry Plantagenet came to Paris to give homage in return for recognition in Normandy, something previous dukes had avoided. He went again as king in 1158, acknowledging that for his French lands: "I am his man." The Plantagenet sons made frequent visits to Paris to give homage. They offered Louis lands in return for recognition, weakening their grasp on vital border territories.

Even the practice of magnates having significant functions in the palace went into decline, but now a new sort of link began to be forged. The role of the magnates was altered by the emergence of large assemblies, sometimes local, sometimes broader. The assemblies at Vézelay and Etampes, in preparation for the Second Crusade, were an important step in the significance of something akin to national assemblies.

Louis's resistance to Frederick Barbarossa also paid dividends: in Flanders, Champagne and Burgundy. Barbarossa saw Louis as a 'kinglet', and coveted the lands between their respective realms, threatening and cajoling his French neighbours. Hostile relations developed between the kings, especially during the papal schism. Again Louis's Church policy gave him advantages. His favoured candidate for the papacy, Alexander III, carried the day, and Churches in the danger area turned to him as protector, as did some of the lesser nobility. The lord of Bresse offered himself as a vassal: 'come into this region where your presence is necessary to the churches as well as to me.'

Nor was Louis easy to push against his will. Even the count of Champagne experienced the king's wrath: 'you have presumed too far, to act for me without consulting me'. Louis's third marriage, to Adela in 1160, cemented his improving relations with the house of Champagne. He had transformed French policy to ally with the natural enemies of Anjou. Adela's brothers, Theobald V count of Blois, Henry the Liberal count of Champagne, Stephen count of Sancerre, and William who would be archbishop of Reims, became vital supporters of the crown; Theobald and Henry also married Louis's two daughters by Eleanor. The crown therefore did not have to face Henry II alone. When in 1173 Louis encouraged the rebellion by Young Henry, he could call to his support the counts of Flanders, Boulogne, Troyes, Blois, Dreux and Sancerre.

In the south Louis attempted to improve his position through marriage agreements. His marriage to Eleanor gave him an interest in Aquitaine, which was not completely abandoned after the divorce. He married his sister Constance to Raymond V count of Toulouse in 1154. In 1162 Raymond declared: 'I am your man, and all that is ours is yours.' It is true that Raymond' s marriage failed, his wife complaining 'he does not even give me enough to eat', and that Raymond flirted with a Plantagenet alliance, but only to join Richard against his father. By 1176 he had returned to the Capetian fold.

Louis used marriage as a prospect to cement relations with Flanders. Louis had brought Flanders into the coalition against Henry II, and now agreement was made for his son Philip to marry Isabella of Hainault, the count of Flanders' niece. The dukes of the other great eastern principality, Burgundy, were a branch of the royal family. As Fawtier has said, it was 'the only great fief over which royal suzerainty was never contested' - at least until the time of Philip Augustus. At Louis VI's coronation, three princes of the realm had refused to give homage. By the accession of Philip Augustus, liege homage of the great vassals to the crown had become the expected practice.

Vassals of the princes sometimes turned directly to the king for aid rather than to their own lords. Many in the south sought Louis's protection, including the viscountess of Narbonne, who declared: 'I am a vassal especially devoted to your crown'. Roger Trencavel received the castle of Minerve from Louis and did homage for it, though he was a vassal of the count of Toulouse, and the castle was not even the king's to give. William of Ypres, though a vassal of

the count of Flanders, asked Louis to enfief his son Robert. Under Louis, not only were the great vassals brought closer, but Capetian influence was filtering through to a lower stratum of vassals.

Jim Bradbury - Philip Augustus, King of France, 1180-1223

#xii#jim bradbury#philip augustus king of france 1180-1223#louis vii#philippe ii#henry ii plantagenêt#frédéric barberousse#pope alexander iii#adèle de champagne#thibaut v de blois#henri i de champagne#étienne de sancerre#guillaume aux blanches mains#marie de france#alix de france#aliénor d'aquitaine#constance de france#raymond v de toulouse#philippe d'alsace#isabelle de hainaut#roger trencavel

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

#xii#marie de france#princesses of france#history of champagne#henri i de champagne#louis vii#aliénor d'aquitaine#adèle de champagne#house of blois champagne#philippe ii#richard cœur de lion#siblings

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marie of France, Countess of Champagne- The Champagne family network.

Henry and Marie's personal relationship remains obscure. They were eighteen years apart in age and had radically different formative experiences. Henry grew up the eldest of four boys and six girls. He accompanied his parents on their journeys and from an early age was groomed in the arts of governance. At the time of his marriage he enjoyed an extensive network of well-placed siblings- Queen Adèle, Counts Thibaut of Blois (royal seneschal) and Stephen of Sancerre, Duchess Marie of Burgundy, and Countesses Agnès of Bar-le-Duc and Mathilde of Perche. Their youngest brother, William, provost of the Cathedral of Troyes and St-Quiriace of Provins, was poised for a brilliant career in the Church and soon became archbishop of Sens. Henry's strong ties with his siblings made for a thick family network that lasted throughout his entire life and later supported Marie after his death.

Marie's early years, by contrast, lacked a secure grounding. Left in Paris as an infant of two during the Second Crusade, she was seven when her mother abandoned her and her younger sister Alix after the royal divorce of 1152. Marie seems not to have met her mother again, but even if she did, it is unlikely that they developed lasting emotional ties. Shortly after Louis remarried, the girls were sent away to the lands of their future husbands, Marie to Champagne and Alix to a convent or aristocratic household in western France. In 1164 fourteen-years old Alix became the second wife of Count Thibaut, then in his mid-thirties, who complained to the king that Henry did not attend his wedding. But in 1166 Alix and Thibaut came to Troyes for the Christmas holidays, which may have been the first time the sisters met since their separation in 1153. Although Marie once referred to her "dearest" sister Alix, they seem to have led entirely separate lives, both in their formative years as young women and even later as regents and widows. Marie developed compensatory attachments to her younger half-siblings: Louis VII's daughter Marguerite (born 1158) and Eleanor of Aquitaine's sons Henry the Young King (born 1155), Richard (born 1157), and Geoffroy (born 1158). She had even closer and long-lasting ties with Count Henry's slightly older siblings, especially Queen Adèle (born ca. 1145) and Archbishop William (born 1135).

[..]

Marie's first trip beyond the county was to Sens, where on 22 December 1168 she and Henry witnessed his brother William's consecration as archbishop of Sens [..]

Beyond being a celebratory event for Count Henry and his siblings, William's consecration was an opportunity for Countess Marie, then twenty-two yeas old with a two-year old son, to see her father again, perhaps for the first time since she left Paris in 1153, and also to meet Henry's sister Queen Adèle, who attended with Louis. That marked the beginning of a long-term relationship between Marie and Adèle, a relationship that became closer in the 1180s after they were widowed. They were about the same age, both with young sons who promised to continue the lineage of their much older husbands. And they were intimately related, Adèle having married Marie's father, Louis, and Marie having married Adèle's brother Henry. The family gathering at Sens surely included Adèle's brothers Count Thibaut, the royal seneschal, and Count Stephen of Sancerre, who together with the queen, the new archbishop, and Count Henry, represented a powerful block of siblings surrounding the king and his three-years-old heir Philip.

Theodore Evergates- Marie of France- Countess of Champagne, 1145-1198 (The Middle Age Series)

#xii#theodore evergates#marie of france countess of champagne#marie de france#henri i de champagne#thibaut v de blois#adèle de champagne#queens of france#étienne i de sancerre#guillaume aux blanches mains#alix de france#louis vii#aliénor d'aquitaine#marguerite de france#henry the young king#richard cœur de lion#geoffroy plantagenêt#philippe ii

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Daughters of the Counts of Flanders and Boulogne, part I

Judith de Flandre, Countess of Northumbria and Herzogin von Bayern. Daughter of Baudouin IV, comte de Flandre and Aenor de Normandie. Grandmother of Judith von Bayern, Herzogin von Schwaben.

Mathilde de Flandre, Queen of England. Daughter of Baudouin V, comte de Flandre and Adèle de France. Mother of Constance de Normandie, dugez Breizh and Adèle de Normandie, comtesse de Blois.

Mathilde de Boulogne, Queen of England. Daughter of Eustache III, comte de Boulogne and Moire of Scotland. Mother of Marie Ire, comtesse de Boulogne.

Gertrude de Flandre, contessa de Savoia. Daughter of Thierry, comte de Flandre and Sibylle d’Anjou.

Marguerite Ire, comtesse de Flandre. Daughter of Thierry, comte de Flandre and Sibylle d’Anjou. Mother of Isabelle de Hainaut, Yolande de Hainaut, and Sibylle de Hainaut

Isabelle de Hainaut, reine de France. Daughter of Marguerite Ire, comtesse de Flandre and Baudouin V, comte de Hainaut. Grandmother of Saint Isabelle de France.

Yolande de Hainaut, markgravin van Namen. Daughter of Marguerite Ire, comtesse de Flandre and Baudouin V, comte de Hainaut. Mother of Isabelle de Courtenay, Tsarina of Bulgaria; Yolande de Courtenay, Queen consort of Hungary; and Marie de Courtenay, Empress of Nicaea.

Sibylle de Hainaut, Dame de Beaujeu. Daughter of Marguerite Ire, comtesse de Flandre and Baudouin V, comte de Hainaut. Mother of Agnès de Beaujeu, comtesse de Champagne.

Jehanne, comtesse de Flandre. Daughter of Baudouin IX, comte de Flandre and Marie de Champagne.

Marguerite II, comtesse de Flandre. Daughter of Baudouin IX, comte de Flandre and Marie de Champagne. Mother of Jehanne de Dampierre, comtesse de Rethel.

#historyedit#house of flanders#french history#belgian history#european history#medieval#women's history#history#royalty aesthetic#nanshe's graphics

92 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Capetian princesses aesthetic, part I

Adèle, comtesse de Flandre. Daughter of Robert II and Constança d’Arle. Mother of Mathilde de Flandre.

Constance, princesse d’Antioche. Daughter of Philippe Ier and Bertha van Holland. Grandmother of Constance d’Antioche.

Cécile, comtesse de Tripoli. Daughter of Philippe Ier and Bertrade de Montfort.

Constance, comtessa de Tolosa. Daughter of Louis VI and Adelaide di Savoia. Mother of Azalaís de Tolosa.

Marie, comtesse de Champagne. Daughter of Louis VII and Alienòr d’Aquitània. Mother of Marie de Champagne.

Alais, comtesse de Blois. Daughter of Louis VII and Alienòr d’Aquitània. Mother of Marguerite, comtesse de Blois.

Marguerite, Queen of England. Daughter of Louis VII and Constanza de Castilla.

Alais, comtesse du Vexin. Daughter of Louis VII and Constanza de Castilla. Grandmother of Jehanne de Dammartin.

Agnès, Byzantine Empress. Daughter of Louis VII and Adèle de Champagne.

Saint Isabelle. Daughter of Louis VIII and Blanca de Castilla.

#house of capet#medieval#historyedit#french history#european history#women's history#history#nanshe's graphics#royalty aesthetic

252 notes

·

View notes