#barbaroux

Text

Frev nicknames compilation

Maximilien Robespierre – the Incorruptible (first used by Fréron, and then Desmoulins, in 1790).

Augustin Robespierre – Bonbon, by Antoine Buissart (1, 2), Régis Deshorties and Élisabeth Lebas. Élisabeth confirmed this nickname came from Augustin’s middlename Bon.

Charlotte Robespierre – Charlotte Carraut (hid under said name at the time of her arrest, also kept it afterwards according to Élisabeth Lebas). Caroline Delaroche (according to Laignelot in 1825, an anonymous doctor in 1849 and Pierre Joigneaux in 1908).

Louis Antoine Saint-Just – Florelle (by himself), Monsieur le Chevalier de Saint-Just (by Salle and Desmoulins)

Jean-Paul Marat – the Friend of the People (l’Ami du Peuple) (self-given since 1789, when he started his journal with the same name)

Georges-Jacques Danton – Marius (by Fréron and Lucile Desmoulins).

Éléonore Duplay – Cornélie (according to the memoirs of Charlotte Robespierre and Paul Barras. Barras also adds that Danton jokingly called Éléonore “Cornelie Copeau, the Cornelie that is not the mother of Gracchus”)

Élisabeth Duplay – Babet (by Robespierre and Philippe Lebas in her memoirs)

Jacques Maurice Duplay – my little friend (by Robespierre), our little patriot (by Robespierre)

Camille Desmoulins – Camille (given by contemporaries since 1790. Most likely a play on the Roman emperor Camillus who saved Rome from Brennus in the 4th century like Camille saved the revolution on July 12, and not a reference to Camille behaving like a manchild to the people around him like is commonly stated.) Loup (wolf) by Fréron and Lucile (1, 2), Loup-loup by Fréron (1, 2), Monsieur Hon by Lucile.

Lucile Desmoulins – Loulou (by Camille 1, 2), Loup by Camille, Lolotte (by Camille (1, 2), Rouleau by Fréron (1, 2) and Camille, the chaste Diana (by Fréron), Bouli-Boula by Fréron (1, 2).

Horace Desmoulins – little lizard (Camille), little wolf (Ricord), baby bunny (Fréron).

Annette Duplessis (Lucile’s mother) — Melpomène (by Fréron), Daronne (by Camille)

Stanislas Fréron – Lapin (bunny) (by himself (1, 2, 3, 4, 5) and Lucile. According to Marcellin Matton, publisher of the Desmoulins correspondence and friend of Lucile’s mother and sister, Fréron obtained this nickname from playing with the bunnies at Lucile’s parents country house everytime he visited there, and Lucile was the one who came up with it). Martin by Camille and himself (likely a reference to the drawing ”Martin Fréron mobbed by Voltaire” which depicts Fréron’s father Élie Fréron as a donkey called ”Martin F”.)

Manon Roland — Sophie (by herself in a letter to Buzot).

Charles Barbaroux — Nysus by Manon Roland

François Buzot — Euryale by Manon Roland

Pierre Jacques Duplain — Saturne (by Fréron)

Guillaume Brune — Patagon (by Fréron)

Antoine Buissart (Robespierre’s pretend dad from Arras) — Baromètre (due to his interest in science)

Comment who had the best/worse nickname!

#french revolution#robespierre#danton#desmoulins#buzot#barbaroux#marat#fréron#maximilien robespierre#charlotte robespierre#augustin robespierre#camille desmoulins#lucile desmoulins#horace desmoulins#stanislas fréron#georges danton#manon roland#saint-just#louis antoine de saint just#élisabeth lebas#élisabeth duplay#éléonore duplay#fréron really likes nicknames…#frev compilation

135 notes

·

View notes

Text

i am being escorted away by the pun police as we speak

bonus:

#my humor is so broken 🥴#happy valentines day except the only people my heart belongs to are men who died over two hundred years ago!!!!!!!!!!!!!!#embrace the comic sans aesthetic 😎💪#frev#art#french revolution#saint-just#robespierre#hérault de sechelles#charles jean marie barbaroux#barbaroux#jean marie goujon#memes#shitpost

201 notes

·

View notes

Text

if I had a nickel for every revolutionary that survived a gunshot to the jaw and was guillotined, I'd have two nickels, which isn't a lot but it's weird that it happened twice.

#personal#frev#robespierre#barbaroux#wasn't there like. a week between Barbaroux shooting himself and him actually getting executed

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Probably a good time to post this it’s been rotting in my files for a bit now,,

116 notes

·

View notes

Text

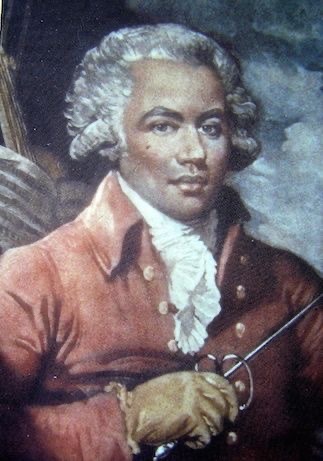

I sweAR TO GOD- If there’s one thing makes me question if I’m really aroace, it’s 18th century French men. Let me say it again…

EIGHTEEN CENTURY MFING FRENCH MEN-

LIKE WHY ARE THEY SO- AUUUUGGGHH

I know this is aesthetic attraction, BUT IMMA KEEP IT REAL WIT Y’ALL- Some of these mfs sLAP! LIKE THEY CAN HIT. ME. UP.

PUHLEASE!

Hand in marriage, Citoyen. HAND IN MARR- Nah I’m joking.

But seriously, why make them this fine bruh, like- oh my God…

IF I MISSED SOME OF YOUR FAVS OR FLOPS, PLEASE DO MENTION THEM!

#also joseph bologne (middle bottom pic) is actually a guadeloupean creole#however his father is french i believe…#probably my first post on frev#frev#french revolution#maximilien robespierre#louis antoine de saint just#camille desmoulins#georges couthon#herault de sechelles#augustin robespierre#barbaroux#joseph bologne#collot d'herbois

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

List of revolutionaries described as attractive by contemporaries:

1. Hérault

2. Barbaroux

3. ... Collot

🤡

#to be fair#i don't actually know if barbaroux was described as good looking#i saw some descriptions but didn't check if they were by contemporaries#so it's maybe just#hérault#and#well#collot#i need time to process this#fun#frev#barbaroux

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

Guys, can sOMEONE PLEASE TELL ME WHAT IS THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN

BARERE AND BARRAS AND BARBAROUX!!!!

#frevblr#frev community#i always need to go to google to understand who is who#i'm so done with them#barere#barras#barbaroux#im screaming#get help (:#fun fact: i still don't understand#shit post

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Journée d'Etude Jeunes Chercheurs : Le Bijou dans l'Histoire” 3e édition de l'Ecole Van Cleef & Arpels (Ecole des Arts Joailliers) animée par et en prEmmanuelle Amiot - Responsable de la Recherche à L'Ecole - et en présence de Mathieu Rousset-Perrier - Conservateur du Patrimoine et Responsable de la Collection Bijoux du Musée - au sein du "Salon des Boiseries” du Musée des Arts Décoratifs, octobre 2019.

#conferences#inspirations bijoux#RoussetPerrier#Amiot#Glorieux#Choi#Khatir#Moner#DufaillyDucel#Klopp#Baranyai#Portillo#Aribaud#Abad#Barbaroux#EcoleVanCleef&Arpels#MuseeArtsDecoratifs

0 notes

Note

hey sono in viaggio a torino a mi domandavo se hai dei posti belli da vedere da consigliare in centro (oltre alle principali attrazioni)?

cerea! fortunellə in giro per torino mentre io purtroppo ne sono lontana! anche se onestamente. buona fortuna, tra caldo e sovraffollamento di turisti <333

ALLORA la cosa bella di torino è che tantissime cose si possono raggiungere tranquillamente a piedi: il centro super centro non è troppo grande, e il centro in senso lato è comunque a portata di passeggiata

al di là di tutto ciò che puoi trovare googolando ‘torino cosa vedere’ (musei ecc) i miei suggerimenti sono (un po’ random)

1. monte dei cappuccini (che sicuramente trovi anche cercando ‘torino cosa vedere’, ma faccio uno strappo alla regola perché è uno dei miei posti preferiti). secondo me il posto più bello per vedere tutta torino dall’alto: se poi è una bella giornata, si vedono bene anche le montagne; meglio ancora se il sole sta calando. a volte i frati della chiesa dei cappuccini tengono aperto il chiostro e la terrazza che si affaccia sull’altro lato della collina: lo fanno veramente a sentimento, ma se trovi aperto approfittane perché è davvero un punto insolito rispetto al normale panorama dal piazzale

1.2 per arrivare e venire via, consiglio passeggiata tra le vie lì in collina, perché ci sono dei palazzi veramente belli e c’è una pace rara, per essere a due passi dal centro

2. parco del valentino, ma non solo il castello, il borgo medievale e la panchina degli innamorati che ok. a me piace tantissimo anche il giardino roccioso, consigliato se passi da quelle parti

2.2 e, nel caso, consiglio sia il lato del parco dall’altra parte del fiume, sia, in alternativa, passeggiata per san salvario (ad esempio se stai risalendo verso il centro): se non ti avvicini troppo alla parte che costeggia la stazione (che ha un po’ il mood stazione, come in tutte le città del resto), ci sono degli angolini molto carini e pacifici. bonus: a sansa c’è anche la sinagoga: non è visitabile (se non in occasioni particolari, probabilmente) ma è molto molto bella da fuori

3. spostiamoci in un’altra zona della città, in centro e molto bella: quadrilatero romano. certo, alcune vie sono iper ultra turistiche, ma io adoro passeggiare a caso tra i vicoletti più piccoli, uscendo dalla zona mega centrale, e sbucare a caso in zone tipo piazza della consolata (bello il santuario, ci sta fare due passi all’interno) e piazza emanuele filiberto. zona che mi piace molto: sembra parigi ma è meglio perché siamo a torino <3

3.2 se passi per quadrilatero, butta l’occhio a porta palatina mi racc!

4. altro posto del cuore, i giardini reali, soprattutto per gli scorci sulla mole (sia dai giardini superiori: si entra passando per palazzo reale; sia dagli inferiori), soprattutto quando c’è poca gente: pace amore e armonia su questo pianeta [se vuoi una live slug reaction, ai giardini superiori ci sono delle sculture di lumache fluo fuchsia]

5. punto unico per consigliare passeggiata per tutte le vie “principali” del centro, ma ça va sans dire: se vai alla mole passi per via po e probabilmente vedrai piazza vittorio e piazza castello etc etc, non mi dilungo

6. ricordati di passare per la galleria subalpina (e conseguentemente piazza carignano e/o piazza carlo alberto e per la galleria san federico (che dà poi su via roma e piazza san carlo): sono stra famose ma magari unə non si ricorda di passarci e si perde degli angolini che sono dei bijou

7. in generale, torino è una città bellissima: io consiglio sempre di camminare a caso perché 1) tanto è pressoché impossibile perdersi, 2) oltre ai musei, ci sono veramente tanti tanti TANTI palazzi/angoli/scorci davvero belli. è una città che ti riempie gli occhi e le sinapsi di bellezza, 3) tante cose sono inaspettate! io alle volte mi trovo in angoli mai visti prima e rimango first reaction shock. c’è una chiesa aperta? vai a vederla, magari è bellissima! un vicolo che pare carino? vacci, tanto poi finisci su una parallela della strada che stavi facendo prima! secondo me è il modo migliore per visitare la città, oltre alle cose da vedere “obbligatoriamente”

non c’è necessariamente coerenza tra un punto e l’altro, quindi magari non riuscirai (o non avrai voglia) di vedere tutto tutto, ma sono i consigli che mi sento di dare un po’ su due piedi. spero di esserti stata utile! :)

#ps c’è anche la fetta di polenta in corso San Maurizio. ma mi pare che sia incartata per ristrutturazione. grazie bonus 110%#bonus vie random che mi sono venute in mente ora e mi piacciono molto: via pietro micca via bertola piazza solferino#via dei mercanti e via barbaroux sono molto carine e si avvicinano a zona quadrilatero. piccole ma caratteristiche (della torino penso#medievale)#VA BEH in pratica ho coperto tutto il centro. quindi scegli tu anche in base a cosa vuoi vedere di ‘famoso’: ma ogni area ha degli angolini#davvero chefs kiss#@ Stefano lo russo le chiavi della città e la cittadinanza onoraria quando

27 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you know anything about the supposed affair between Madame Roland and Buzot as well as maybe her relationship with Barbaroux?

Thank you!

The first time Manon mentions Buzot in her conserved correspondence is in a letter to Brissot dated April 28 1791 — ”your good friend Pétion got excited and spoke of it all the better; but why do the vigorous Robespierre and the wise Buzot not give themselves up to the advantage of written speeches, to the kind of reason for which one can then add the magic of declamation?” We do however have to wait until the fall of the same year to find a letter indicating the two were also becoming personal friends, it is dated September 9 1791 and adressed to Jean-Marie Roland:

I had promised myself to write to Madame Buzot; she could not imagine my sensitivity to the testimonials of interest that she has been kind enough to give me; I left her with a sort of haste, because I had to tear myself away, but that moment never leaves my heart. Tell her and her worthy husband how dear they are to us; you can speak for both of us, since you love them as much as I do.

During her interrogation held after her arrest on June 1 1793, Manon admitted her relationship with Buzot had started earlier than what her correspondence reveals, claiming she and her husband ”had been linked since the Constituent Assembly with Brissot, Pétion and Buzot” and ”that she knew them with Roland and through Roland; and that she had for them the degree of esteem and attachment each of them seemed to deserve according to her.” In her memoirs, she also reports the following about her relationship with the Buzots during the period of the Constituent Assembly:

During the Constituent Assembly, at the time of the revision, I was one day with Buzot's wife, when her husband returned from the Assembly very late, bringing Pétion for dinner. It was the time when the court had them treated as factious, and painted them as intriguers, all occupied in stirring up and agitating. After the meal, Pétion, seated on a large ottoman, began to play with a young hunting dog with the abandonment of a child; they both let go and fell asleep together, snuggled on top of each other: four people conversing did not prevent Pétion from snoring. ”So here we have this rebel,” said Buzot, laughing; ”we were looked askance on leaving the room, and those who accuse us, very agitated for their party, imagine that we are to maneuver!”

Buzot did not live very far from us; he had a wife who did not seem on the same level as him, but who was honest, and we saw each other frequently. When the success of Roland's mission, relating to the debts of the commune of Lyons, enabled us to return to Beaujolais, we remained in correspondence with Buzot and Robespierre; it was better followed with the former; there reigned between us more analogy, a greater basis for friendship, and a fund otherwise rich to maintain it. It became intimate, unalterable; I will tell elsewhere how this connection was tightened.

It’s most likely after the two were reunited for the National Convention in September 1792 that the relationship became more than platonic — at least it’s only after this we find signs of this being the case. Throughout the latter months of 1792 we have a series of frosty letters exchanged between Manon and her protégé Lanthenas, which all seem to allude to the affair (check out page 261-262 of Marriage and Revolution: Monsieur and Madame Roland for an analysis of these). On December 25 1792 we also find a note Manon sent to Servan, telling him that ”after my husband, my daughter and one other person, you are the only one to which I make [my portrait] known.” In her memoirs, she further claims to have visited Buzot’s wife only a single time since the beginning of the Convention, a choice we might imagine was influenced by the growing feelings between her and François:

As for the alleged confabulations at the house of Buzot's wife, no charge in the world is as ridiculous. Buzot, whom I had seen a great deal during the Constituent Assembly, with whom I had remained in friendly correspondence; Buzot, whose pure principles, courage, sensitivity, gentle manners, inspired me with infinite esteem and attachment, came frequently to the Hôtel de l'Intérieur: I only went home to his wife's once since their arrival in Paris for the Convention.

Jean-Marie also found out about the relationship. In her memoirs, Manon writes the following about it:

I honored and cherished my husband like a sensitive daughter adores a virtuous father, to whom she would even sacrifice her love. But I found the man who could be that love, and, while I remained faithful to my duties, my ingenuous nature was unable to conceal the feelings that I was suppressing for their sake. My husband, a man of extreme sensitivity, both in affection and self-love, was unable to tolerate the slightest alteration of his rule; his imagination painted things in the darkest colours, his jealousy irritated me; happiness had fles far away from us, and both of us were unhappy.

The affair also didn’t go unnoticed by contemporaries. In his Étude sur Madame Roland, Charles-Aimé Dauban cites the following passage from the Moniteur on June 15 1793:

Duroy: I'm from the same department as Buzot; I have worked with him, and I am convinced that he would sacrifice the whole republic to satisfy his ambition. The marked incivility of Buzot dates from September 13; at that time, he received a letter from the wife of Roland (laughter is heard); he read it to me: the wife of Roland complained that the revolutionary commune had issued a warrant for the arrest of the virtuous Roland.

Dauban suggests the reason people laughed after hearing Manon mentioned is because they knew about the relationship between her and Buzot.

Their relationship also appears to be what Desmoulins is talking about in his Histoire des Brissotins (May 1793) when he writes: ”Jérôme Pétion told Danton in confidence that ”what makes poor Roland saddest is the fact people will discover his domestic sorrows and how bitter being a cuckold is to the old man, troubling the serenity of that great soul.” The girondin Louvet also seems to be alluding to it in his memoirs (1795) when remembering the day he said farewell to Buzot, Pétion and Barbaroux for the very last time:

[Pétion, Buzot and Barbaroux] were going, a few leagues away, towards the sea, to seek an invertan asylum; with what sorrow we bade each other farewell! Poor Buzot, he carried deep in his heart very bitter sorrows, which I alone knew, and which I must never reveal.

And the deputy René Vavasseur reported in his memoirs: ”Salles and Buzot were the most irritable of the party. We know one of the causes of Buzot's excessive irritability.”

Manon was arrested on June 1 1793, while Buzot fled Paris to avoid the same fate. They would never see each other again. We do however know of five letters Manon wrote to Buzot while in captivity (first published in 1864 within Charles-Aimé Dauban’s Étude sur Madame Roland et son temps). These, it would appear, are the only letters exchanged between them that have been conserved, or at least published (the letters Buzot wrote to Manon that the latter mentions, would for example appear to have gone missing). Since all five letters are quite long I’ve decided to only include the parts dealing with their relationship here:

June 22

How I reread them! I press them to my heart, I cover them with my kisses; I no longer hoped to receive any!... I had in vain searched for news of Madame Ch(alot); I had once written to M. Le Tellier, to É(vreux) so that you may have a sign of life from me; but the post is violated; I didn't want to send you anything, convinced that your name would cause the letter to be intercepted and that I would have compromised you. I came here, proud and calm, forming wishes and still harboring some hope for the defenders of liberty, when I learned of the decree of arrest against the twenty-two; I cried: My country is lost! I was in the most cruel anguish until I was assured of your escape; they were renewed by the decree of accusation which concerns you; they deviate well this atrocity to your courage! But, as soon as I found out that you were in Calvados, I regained my peace of mind. Carry on, my friend, with your generous efforts; Brutus despaired too soon of the salute from Rome to the fields of Philippi; as long as a republican breathes that he has his freedom, that he keeps his energy, he must, he can be useful. The midi offers you, in any case, a refuge; it will be the refuge of good people. It is there, if the dangers accumulate around you, that you must turn your eyes and carry your steps; it's there there that you will have to live, because there you will be able to serve your fellow men and exercise virtues. As for me, I will be able to either wait peacefully for the return of the reign of justice, or suffer the last excesses of tyranny, in a way that my example becomes just as useful. If I have feared something, it is that you have made imprudent attempts in my favor; my friend! It is by saving your country that you can bring my salvation, and I would not want my salvation at the expense of the other; but I would die satisfied knowing that you serve your country effectively. Death, torment, pain, they are nothing to me, I can defy it all; go, I will live until my last hour without wasting a single moment in the confusion of unworthy agitations. […] I spent my first days (in prison) writing a few notes which will one day give pleasure; I put them in good hands and I'll let you know, so that, in any case, they do not remain foreign to you. […] I dare not tell you, and you are the only one in the world who can appreciate it, that I was not very sorry to be arrested. ”They will be less furious, less ardent against R(oland), I said to myself; if they attempt a lawsuit, I will know how to support it in a way that will be useful to his glory; it seemed to me that I thus acquitted myself towards him of a indemnity due to his sorrows; but don't you also see that in finding myself alone it is with you that I remain? Thus, through captivity, I sacrifice myself to my husband, I preserve myself to my friend, and I owe to my executioners to reconcile duty and love: don't pity me! The others admire my courage, but they do not know my pleasures; you, who must feel them, keep them and all their charm by the constancy of your courage. This amiable Goussard! How taken I was to see his sweet face, to feel myself being pressed into his arms, being wet with his tears, and see him pull from his bosom two letters from you! May these details bring some calmness to your heart ! Go! we cannot cease to be reciprocally worthy of the sentiments which we have inspired in each other; we are not unhappy with that. Farewell my friend; my beloved, farewell!

July 3

What sweetness unknown to tyrants, whom the vulgar believe happy in the exercise of their power! And if it is true that a sublime intelligence distributes goods and evils among men according to the laws of rigorous compensation, can I complain of my misfortune, when such delights are reserved for me? I received your letter from the 27th; I still hear your courageous voice, I witness your resolutions, I experience the feelings that animate you, I am honored to love you and to be dear to you. Tell me, do you know sweeter moments than those spent in innocence and the charm of an affection that nature avows and that is regulated by delicacy, which pays homage to the duty of the privations it imposes on it, and nurtures the very strength to bear them? Do you know of any greater advantage than that of being superior to adversity, to death, and to find in your heart what to taste and beautify life to its last breath? Have you ever experienced these effects better than through the attachment that binds us, despite the contradictions of society and the horrors of oppression? I told you, I owe it to said attachment to please me in my captivity. Proud to be persecuted in this time when character and probity are proscribed, I would have borne it, even without you, with dignity; but you make it sweet and dear. The midwayers believe they are overwhelming me by putting me behind bars... Fools! what do I care if I live here or there? Don't I bring my heart everywhere I go, and reassure myself in prison, isn't that giving myself up to it without share? My duties, as soon as I am alone, are limited to vows for all that is just and honest, and what I love still occupies the first rank in this order. Go, I feel too well what is imposed on me in the natural course of things to complain about he violence that overthrew it.[…] I found it delightful to unite the means of being useful to [Roland] with a way of living which left me more to you. I would like to sacrifice my life to him in order to acquire the right to give my last breath to you alone. Except for the terrible agitations which the decrees against the exiles caused me, I never enjoyed greater calm than in this strange situation, and I tasted it without mixing once I learned almost all of them were in safety, since I saw you working in freedom to preserve that of your country. […] May this letter reach you soon, and give you a new testimony of my unalterable sentiments, communicate to you the tranquility that I enjoy, and add to all that you can feel and do that is generous and useful, the inexpressible charm of the affections that tyrants never knew, affections which serve both as trials and as rewards to virtue, affections which give value to life and make it superior to all evils! Greetings to our friends, and especially to the sensitive L(ouvet).

July 6

Yesterday I saw for the second time this excellent V(allée). He gave me your letters from the 30th and first. I didn’t dare to open them in his presence. One does not read a friend’s letter in front of a third party, if only he had known what he was carrying. […] I feel all the generosity of your care , the purity of the wishes, and the more I appreciate them, the more I like my present captivity. […] Four days ago I had this dear picture brought to me, that I, through some sort of superstition, didn't want to put in a prison; but why then refuse this sweet image, beautiful and precious as a revelation of the presence of the object? It is on my heart, hidden from all eyes, felt at all times and often bathed in my tears. Go, I am penetrated by your courage, honored by your attachment and by all that they both can inspire in your proud and sensitive soul. I cannot believe that heaven only reserves sorrows for sentiments so pure and so worthy of its favour. This sort of confidence makes me support life and contemplate death with calmness. Let us enjoy with ignorance the goods which are given to us. Whoever knows how to love as we do carries with him the principle of the greatest and best deeds, the prizes of the most painful sacrifices, the compensation for all ills. Farewell, my beloved, farewell!

July 7

[…] How I adore the bars behind which I’m free to love you without limits and where I can think of you without stop. Here, any other duty is forgotten, I no longer owe myself to anything except to the one who loves me and deserves to be cherished so well. Continue your career with generosity, serve your country, save liberty, each and everyone of your actions is a pleasure for me, and your conduct is my triumph. […] I am interrupted; my faithful maid brings me your letter from the 3rd; you are worried about my silence. […] If fate did not allow us to reunite soon, should we therefore abandon all hope of ever being brought together, and see only the tomb where our elements could be confounded? Metaphysicians and vulgar lovers talk a great deal about perseverance, but it is that of conduct which is rarer and more difficult than that of the affections. Surely, you are not made to lack anything that belongs to a strong and superior soul: do not therefore allow yourself to be carried away by the very excess of courage towards the goal where despair would also lead. You have seen my reasons for not accepting, under these circumstances, a dangerous expedient which does not seem necessary to me; but if the circumstances were to worsen decidedly, I would not persist in refusing a measure that their rigour would justify. It is only a question of calculating calmly, so as not to give to the impetuosity of feeling what it is for prudence to determine.

August 31

Know, my friend, the heart and attachment of your Sophie. You can’t yet imagiene her emotion, her delight at receiving your news. But what incertitudes remains with her, what worries devour her! Why don’t you talk a bit more about your business ventures, so perilous under the circumstances? The modesty of your small properties, the successes you can achieve for yourself are the only benefits she is likely to enjoy in the languor to which she is reduced; she breathes only for the fatherland and will die if you must suffer. I have taken it upon myself to speak to you for her and you cannot hide from yourself the need she has for employing a foreign hand. I will tell you better about her condition. Her sickness has, since your departure, taken a fatal character. […] The state of her family and the idea of your prosperity supported her at that time. I saw you, happy in suffering, preserving her serenity, the freedom of her mind, enjoying the goods she thought reserved for you and looking at herself as a propitiatory victim whose fate perhaps wanted the sacrifice for the price of the advantages assured to those who are dear to him. […] In the strange destiny which unites you so closely to disperse you more cruelly still, enjoy at least, oh my friend! the aspiration to be cherished with the tenderest heart that ever was. What tears I saw poor Sophie shed, kissing your letter and your portrait! Save your days for her; it is not impossible that her age resists the attacks which she bears with such courage; and you owe yourself to her love as long as she exists. She asked me to ask you if you neglected to take your speculations to America? She is convinced that, in spite of the embargo which opposes exports, but which cannot last long, it was with the United States that it was convenient for you to deal. She would like your views to turn in that direction; she was so penetrating with the depth of this disposition, that she is tormented by the suspiciousness which she believes to appear in your letter in this regard. […] Be wiser, my friend, don't think of anything from now on except with these brave republicans, there is no trust and security except with people of this species. Sophie awaits announcement of your resolution in this respect as it was the only means to parry your misfortunes. Farewell, man most beloved by the woman most in love! Farewell! Oh, how you are loved!

The correspondence appears to end here, despite it being another two months before Manon was executed. Through a letter from October the same year we learn that Manon gave away the portrait of Buzot she talks about in the fourth letter to a friend, telling him to take good care of it — ”it is my dearest property, I could only get rid of it in fear that it would be profaned.”

After the death of Manon we find a letter from Buzot to Jérome le Tellier, where he writes the following:

She is no more, she is no more, my friend! The scroundels have murdered her! Judge if I have anything left to regret on earth! Once you learn of my death, you will burn her letters.

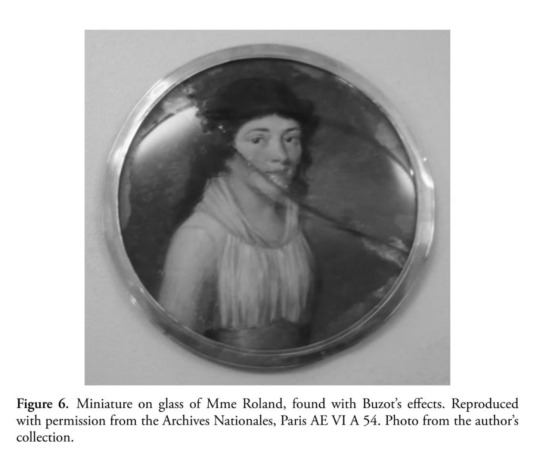

Finally, among Buzot’s effects was found the following portrait depicting Manon (cited on page 260 of Marriage and Revolution: Monsieur and Madame Roland):

As for the relationship between Manon and Barbaroux, I’ve not been able to find any letter between the two. A lot does however point towards such things having existed, but, like in the case of Buzot, been either destroyed or gone missing.

On June 13 1793 Barbaroux wrote to Lauze Duperret: ”Do not forget the estimable citizen Roland, and try to give her some consolation in her prison, by transmitting to her the good news; for that, you could go see Champagneux, head of the offices of the Minister of the Interior.” He followed that up two days later when telling the same person:

You will no doubt still have fulfilled my commission with regard to Madame Roland, by trying to pass on some consolations to her. She must be very unhappy, this estimable wife of the most estimable citizen! Ah! make every effort to see her and tell her that the twenty-two proscribed deputies, all good men, share her pain; may that relieve her! Do you think they have a plan to keep her prisoner? I don’t think so; I believe, on the contrary, that her virtue embarrasses them, and that they would like to see her removed. She should try the proposal to stay only under house arrest. May she soon enjoy her freedom, with our good friends! What a terrible crisis! but also what glory if we save freedom! I give you, enclosed, a letter that we have written to this estimable citizen; I don't need to tell you that you alone can fulfill this important commission: she must, at all costs, try to get out of her prison and find safety.

Duperret did as he was asked, writing to Manon on an unspecified date to tell her that ”I have for several days kept three letters Buzot and Barbaroux had adressed to me to give to you, without it being possible for me to send them to you.”

In another undated letter Manon responded to Duperret:

The news regarding my friends is the only good that affects me; you helped me taste it; tell them that the knowledge of their courage, and of all that they are capable of doing for liberty, consoles me over everything; tell them that my esteem, my attachment and my wishes will follow them everywhere, that the poster (affiche) of B(arbaroux) gave me great pleasure, etc.

All these letters were later used during Manon’s trial to help pass her death sentence.

Manon also shortly mentions Barbaroux in her fourth prison letter to Buzot. Her daughter’s music teacher Anne-Marie-Madeleine Mignot, did in her turn claim during her interrogation ”that [since August 13 1792] she noticed several deputies from the National Convention, such as Brissot, Gensonné, Guadet, Louvet, Barbaroux, Buzot, Pétion, Duperret, Duprat, Chassey, Vergniaux, Condorcet, and others whose names she doesn’t remember, often visited [the Rolands]; that especially Brissot, Buzot, Gorsas, Gensonné and Louvet came there more frequently than the others and had the most direct contact with femme Roland, who often received them in her cabinet.” Barbaroux would in other words have been a frequent visitor to the Rolands, but not the most frequent of them all. This was also confirmed by Manon herself, who during her own interrogation admitted Barbaroux came to visit her and her husband ”from time to time.”

Other than that, we basically only have their memoirs to rely on in regards to their relationship.

Manon’s memoirs:

It was in the course of July that, seeing affairs worsen by the perfidy of the court, the march of the foreign troops and the weakness of the Assembly, we sought a place where the threatened liberty could take refuge. We often talked with Barbaroux and Servan about the excellent spirit of the south, the energy of the departments in this part of France, and the facilities that this place would present for founding a republic there, if the triumphant court were to subjugate the North and Paris. We took maps; we traced the line of demarcation: Servan studied the military positions; they calculated the forces, they examined the nature and the means of transferring the productions: each one recalled the places or the people from whom one could hope for support, and repeated, that after a revolution which had given such great hopes , it was not necessary to fall back into slavery, but to try everything to establish somewhere a free government. “It will be our resource,” said Barbaroux, “if the Marseillais whom I have accompanied here are not sufficiently well supported by the Parisians to reduce the court; I hope, however, that they will come to the end of it and that we will have a Convention which will give the republic for all of France.

Barbaroux, whose features painters would not disdain to take for a head of Antinous, active, industrious, frank and brave, with the vivacity of a young Marseillais, was destined to become a man of merit and a citizen as useful as enlightened . Lover of independence, proud of the revolution, already nourished with knowledge, capable of a long attention span with the habit of applying himself, sensitive to glory; he is one of those subjects which a great politician would like to attach to himself, and which was to flourish with brilliance in a happy republic. But who would dare to foresee to what point premature injustice, proscription, misfortune can compress such a soul and wither its fine qualities! Moderate successes would have sustained Barbaroux in his career, because he loves reputation and has all the faculties necessary to make a very honorable one for himself: but the love of pleasure is next to it; if he once takes the place of glory, through spite of obstacles or disgust at reverses, he will weaken his excellent temper and cause him to betray his noble destination. During Roland's first ministry, I had occasion to see several letters from Barbaroux, addressed rather to the man than to the minister, and whose object was to make him judge the method that should be employed to preserve in the good path of ardent and easily irritated spirits, like those of the Bouches-du-Rhône. Roland, a strict observer of the law, and severe like it, could only speak one language when he was in charge of its execution. The administrators had gone a little astray, the minister had reprimanded them vigorously; they had become embittered: it was then that Barbaroux wrote to Roland to pay homage to the purity of intention of his compatriots, to excuse their errors, and to make Roland feel that a softer mode would bring them back more surely to the necessary subordination. These letters were dictated in the best spirit and with consummate prudence; when I saw their author, I was astonished at his youth. They had the effect which was unmistakable on a just man who wanted the good; Roland relaxed his austerity, took on a more fraternal than administrative tone, brought back the Marseillais and esteemed Barbaroux. We saw him more after leaving the ministry; his open character, his ardent patriotism inspired us with confidence; it was then that, reasoning from the bad state of things and from the fear of despotism for the North, we formed the conditional project of a republic in the South. “It will be our last resort,” said Barbaroux, smiling; but the Marseillais who are here will exempt us from having recourse to it. We judged by this speech and some others like it, that an insurrection was on the horizon; but confidence not extending further, we did not ask more about it. In the last days of July, Barbaroux almost ceased coming to our house, and told us, at the last, that we should not judge his feelings towards us based on the first glimpse of his absence, that his intention with it was to not compromise us. He set out again for Marseilles after the tenth, and returned as a deputy to the Convention. He did his duty there as a man of courage; many of his written speeches show excellent logic and knowledge in the administrative part of commerce; that on subsistence is, after the work of Creuzé-la-Touche, the best of its kind. But he would have to work to become a speaker. Barbaroux, affectionate and lively, became attached to Buzot, sensitive and delicate; I called them Nysus and Euryale: may they have a better fate than these two friends! Louvet, finer than the first, happier than the second, as good as both, became friends with both of them, but more particularly with Buzot, who served as a link to the other, and whose natural gravity made him a bit of a mentor.

Barbaroux’ memoirs:

I went to the interview. Roland lodged in a house in the rue Saint-Jacques, on the third floor; it was a philosopher's retreat. His wife was present at the conversation and participated in it. Elsewhere, I will talk about this amazing woman. Roland asked me what I thought of France and the means of saving her; I opened my heart to him and concealed nothing from him of our first attempts in the South. Precisely, Servan and him had occupied themselves with the same plan. My confidences brought his. He told me that liberty was lost if the plots of the court were not foiled without delay; that La Fayette seemed to meditate on treasons in the North; that the army of the center, completely disorganized , lacking all kinds of ammunition , could not prevent the enemy from making a breakthrough, and that finally everything was arranged for the Austrians to be in Paris in six weeks. Have we then, he added, worked for three years at the finest revolution only to see it overthrown in a day? If liberty dies in France, it is forever lost for the rest of the world: all the hopes of the philosophers are disappointed. The most cruel tyrant will weigh on the earth. Let us prevent this misfortune, let us arm Paris and the departments of the North: or, if they succumb, let us carry to the south the Statue of Liberty, and found somewhere a colony of independent men. He said these words to me, and tears rolled from his eyes. The same feeling made those of his wife and mine flow. Oh! how the outpourings of confidence relieve saddened souls! I quickly gave them an overview of the resources of our departments and our hopes. I saw a sweet joy spread over Roland's brow; he shook my hand, and went to look for a geographical map of France.

Finally, I also found the following footnote in Mémoires inédits de Pétion et mémoires de Buzot et de Barbaroux:

Barbaroux had been the confidant of Madame Roland and of Buzot. I learned this fact from M. Barbaroux, who learned it from his grandmother. We can see, moreover, the confirmation of this tradition in certain passages in the letters from Barbaroux to Madame Roland, which we have published along with the letters to Buzot in our Étude sur madame Roland.

I have no idea regarding the letters from Barbaroux to Manon mentioned here however, I could find none whatsoever inside Étude sur madame Roland.

#girondin drama#Manon care to explain how the hell Euryale is a romantic nickname for your lover???#françois buzot#charles barbaroux#manon roland#ask#frev#buzot#barbaroux#frev friendships

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

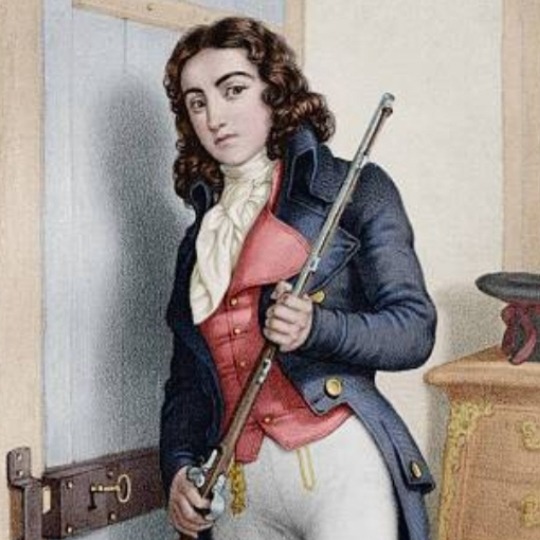

oh yea i finally finished that barbaroux painting from like a month ago 😔

#i took a break after painting the face then came back to it and finished the rest in a day lmao#the things i do for the forbidden bebe#the hat looks annoyingly plain but i cant find any way to fix it :(#barbaroux

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

[from Clifford D. Conner's Jean-Paul Marat: Tribune of the French Revolution]

I want to do evil physics with them

#personal#'evil physics' meaning that time I lit my electronics final on fire. and launched a PVC pipe rocket directly into traffic#marat#barbaroux#frev

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Plaque en hommage à : Charles Barbaroux

Type : Lieu de résidence

Adresse : 20 rue Mazarine, 75006 Paris, France

Date de pose : 1989

Texte : Dans cette maison habita en 1791 le député girondin Charles Barbaroux, 1767-1794

Quelques précisions : Charles Barbaroux (1767-1794) est un homme politique français. Diplômé de droit, il est une des figures marseillaises de la Révolution française. Il rejoint Paris, continuant à représenter Marseille au sein des forces révolutionnaires, et prend part à la journée du 10 août 1792 durant laquelle ses actions l'amènent à être élu député à la Convention. Opposé à Robespierre, il doit fuir la Terreur. Échappant à une arrestation, il se réfugie successivement à Caen, Quimper et Bordeaux. Pensant être sur le point d'être capturé, il tente de se suicider, mais manque sa tentative. Il est finalement arrêté et exécuté.

#individuel#hommes#residence#politiciens#revolution francaise#france#ile-de-france#paris#charles barbaroux

0 notes

Text

The unrealistic thing about the french revolution is that noone came up with the idea of making barbaroux stop talking girondin bullshit by giving him a kiss

26 notes

·

View notes