#and historical re-enactors or places like

Text

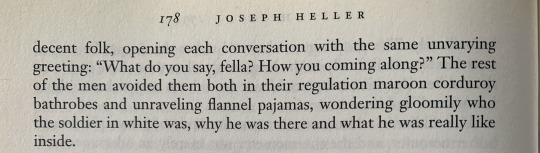

If you read the novel Catch-22 (1961), about U.S. Army pilots & sundry stationed on a Greek island during World War II, you will encounter this off-hand description during the period where Yossarian is hiding in the field hospital:

At which you will either pause worryingly, or you’re normal.

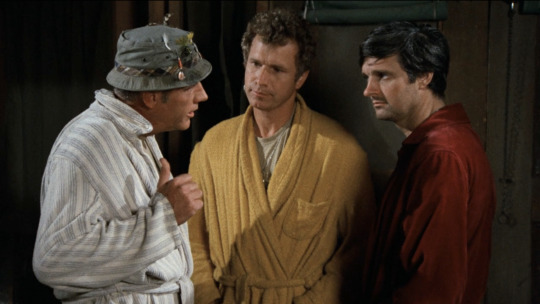

I am not normal, because I have watched the television show M*A*S*H (1972-1983), about U.S. Army medical staff in a mobile surgical unit during the Korean War, and which features a character called Hawkeye Pierce, who frequently looks like this:

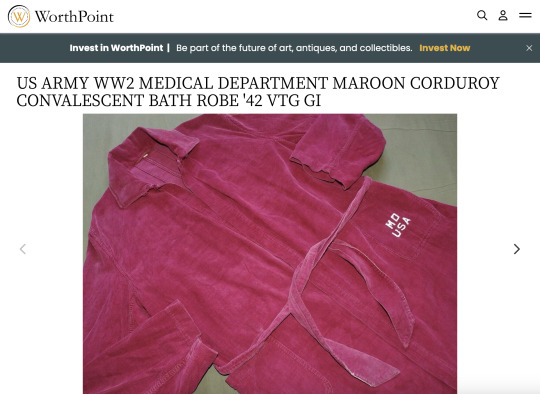

Now this bathrobe, iconic simply, appears red to the observer. However, deep into the run there is a line in which Hawkeye refers to it as "purple"—great consternation. But film cameras and light waves being what they are (capricious, devilish), it could very well be maroon in life. It could very well be maroon. It’s what I assumed after that comment. But what I'd never asked was, what is it made out of? Is that corduroy, could it be corduroy, could this be—

Oh noooooooo!

Why is Hawkeye the only one who is wearing the robe of patients from the last war, I ask you! Is it for the METAPHOR. To make me YELL. Did the costume department make it for him, or did they just already have one on hand in the WWII storage? Wait it wasn't real was it? Where is it, where is this robe!

Well babe, it’s in the Smithsonian:

A) of all, fucking fantastic, could not be a place I more want Alan Alda’s bathrobe as Hawkeye Pierce to be than the National Museum of American History. B) well well well well well, what do we have here:

[sic]

So looking THAT up brings you nothing that makes any sense, even trying to correct for spelling. But not to fear: historical re-enactors are here.

On the website of the “WW2 US Medical Research Centre,” an absolutely delightful combination of words and spelling brought to you by two European history buffs, and that’s Europeans who are obsessed with history, specifically American medical units in the 1940s, there’s a page for pajamas, and why look who’s here:

OH ho oh HO!

“Progressive Coat & Apron Mfg. Co.” is so similarly bizarre that I would be very willing to bet that something like idk, the imperfect process of digitizing thousands of records for a website catalog, could have absolutely resulted in “Agressive Coat and Manufacturing Company.” Which would mean yeah, yeah yeah: vintage World War II, slash Korea, just five years later. It was authentic, what they gave Alda to wear, along with his dog tags.

Just Hawkeye though still, which is what's odd.

BUT HANG ON.

Heeeeey now!

So I was recently reminded that in the pilot episode, but the pilot episode only, Wayne Rogers as Trapper John McIntyre also has the regulation corduroy MD/USA bathrobe! In fact, he actually has what would appear to become Hawkeye’s—observe the location of the embroidery. Pocket, like Hawkeye’s in every robe appearance after this first episode, the robe that ends up in the Smithsonian Museum. Whereas the one with the embroidery on the chest that's hanging above Hawkeye's cot here, a common variant that shows up when you’re searching around on military history websites, after this appearance I believe is seen just once more on a visiting colonel later in the first season, then quietly vanishes. Alda ends up in Trapper's, and stays in it for keeps, while Rogers gets, of all things, a cheery goldenrod terry number.

But like, why. Why just Hawkeye in the WWII surplus robe. Both Doyle and Watson have avenues here that I like to think about. For the Doylist side, I suspect it was a decision of like, this is simply too matchy. It’s 1972, our TV screens are small, we gotta take any chance we can get to distinguish these tall white men constantly wearing the same of two monochrome outfits.

In fact, I actually wonder if there was a world where Trapper might have stayed in the maroon and Hawkeye could have ended up in Henry’s robe.

The light blue & white striped bathrobe McLean Stevenson wore as Henry Blake was sold at auction in 2018, and the item description contains the curious detail of it having a handwritten tag inside reading “Hawkeye.” Well heeeyy again.

And here’s another curious detail:

There was a blue & white striped Army-issue robe as well

Now Henry’s is clearly NOT vintage WWII, lacking the pocket embroidery, being terry cloth, and also of course: pastel. But it’s INTERESTING, isn’t it? They had to have been GOING for that look, with that same unusual collar shape and that multi-stripe patterning.

(Also, for real 'what the hell even IS this color' fun, this militaria collectors purveyor has one of the maroon versions too, with photos you can page though and laugh as it flips between looking clearly purple and clearly red in every other photograph. Cameras!!!)

Anyway now we turn to the Watsonian explanation, which seems to run like this: the men at the 4077 were just casually passing their robes around to each other. It's about the intimacy in the face of war, etc. I can see bathrobes going missing when they bug out, getting stolen from the laundry by Klinger and scrapped for parts, being handed off to a poor cold Korean kid who needs it more, and then they need to get to the showers and one of them is like hey, just take mine, and then it’s his now. And eventually most of them end up in warmer-looking civilian robes than the Army holdovers that were being distributed early on, but Hawkeye, he just hung on to Trapper's.

And as a side effect, still looks like he's been injured in World War II.

#thank you for going with me on this journey#and thank you in particular: to Joseph Heller#really froze me in place at that line buddy#M*A*S*H#M*A*S*H hours#Catch 22#Joseph Heller#WWII

207 notes

·

View notes

Text

ao3 is mostly back up and @justleaveacommentfest is continuing! The theme for Day 2 is short (less than 2k words), so here’s a few shorter Davekat fics (+one Karkat&Roxy fic). You can find my recs for Day 1: New Fics/Old Fics here too. Feel free to comment with some recs for me as well <3

Again, even if you don’t read these fics, please go leave some comments!

Do You Look Like Me? 420 words, Dovekat <3

Summary: You’re beginning to feel something like panic, something awful and anxious kicking at your ribs, and you fucking hate it, and most of all you hate that there’s nothing you can do.

Be The One 1403 words, marriage proposal

Summary: It had never been easy for Karkat, no matter how hard he’d tried not to vacillate. He loved the idea of it, the concept of romance, but something about him and it did not work. His love was too much. He was too much.

This is a story about Karkat coming out as monogamous to himself and proposing to Dave.

Who The Fuck Catches A Cold In July? 1963 words, sickfic (this fic is locked, so you’ll need an ao3 account to read it)

Summary: Dave is sick. Karkat coddles him.

The Society of Skaian Re-enactors 1961 words, post-canon from the POV of a future Carapacian tour guide :P

Summary: The truth is, you love your job giving tours of one of the most fascinating landmarks on the Registry of Historic Places in Troll Kingdom. You’re about to begin your final tour of the day when two young men—who speak and dress like they’re attempting to re-enact two of the Creators from a millennium ago—join the tour group at the last minute. And they are seriously trying your patience.

+This isn’t Davekat and it’s a self rec but it’s the second Homestuck fic I ever wrote back in 2013 and it’s Karkat+Roxy being buddies and it’s silly lmao. Feel the Beat 967 words

Summary: Karkat is never accidentally falling asleep at a party ever, ever again.

#fic rec#homestuck fic#just leave a comment fest#davekat#dovekat#dave strider#karkat vantas#roxy lalonde#dove strider

25 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you have a favorite historical movie? Is there a movie that’s so inaccurate you can’t stand it? (Besides 300. That’s a nightmare…)

Ugh, I hate to admit it, but I'm a sucker for Gettysburg. Yes, both the movie and the book it's based on have some serious problems* but the way that they filmed on location and used re-enactors and practical effects helps the movie stand up over time. Plus I maybe also have a little bit of a crush on Col. Chamberlain's accent. I rewatch part of the movie every year for Memorial Day.

*The Killer Angels, and Gettysburg by extension, choose to portray Southern generals (most notably Lee and Longstreet) as overly sympathetic characters. While the Union Chamberlain's abolitionist sentiments are given voice, he gets less screen time than the Confederates combined and the depiction of Lee and Longstreet serves to erase the horrors of the slavery that they were fighting to protect.

As for one that I don't like, I'm not the biggest fan of Lincoln with Daniel Day Lewis. I think that we tend to give Lincoln the benefit of martyrdom after the fact, and let him skate by with some of the infinitely more problematic areas of his person and policies. In particular, Lincoln takes place beginning shortly after the Gettysburg Address in 1863. This is what I think of as the "golden era" of Lincoln's administration, after he'd worked out some major kinks.

Team of Rivals (the book Lincoln is based on) and its movie neglect the fact that Lincoln was originally in favor of shipping Black people back to Africa rather than initially committing to making inroads for Civil Rights. It makes Lincoln seem like a predestined giant, not a man who won the Republican nomination in 1860 mostly because he was the least divisive candidate. Yes, Lincoln was a great man, but he shouldn't be given all of the credit for all of the things all of the time.

-Reid

49 notes

·

View notes

Note

(@wingsofachampion) Hiya! I've been hearing a lot about Hisui, what is it? -Tropius

oh i am ALWAYS down to talk about Hisui

Hisui is an older name for the Sinnoh region, and scholars often use the term to refer to region as it existed in pre-modern times. The name Sinnoh actually comes from a collective title that was once used for the legendary Pokémon Dialga, Palkia, and Arceus. For a while the two major clans of Hisui, Diamond and Pearl, were in conflict over whether Dialga or Palkia was the more legitimate form of Sinnoh, but eventually they were able to come to a mutual understanding and they began to see the other clan's view as just as legitimate as their own. As the region grew, it started to be called "the Sinnoh region" more and more (both by the locals and by outsiders), and now its modern name is Sinnoh and the term "Hisui" is just a relic of the past

Hisui is special in that many Pokémon have forms that were (mostly) unique to that place and time. For instance, Hisuian Growlithe!

Honestly my favorite regional form of all time.

Another notable fact about Hisui is that Team Galactic, the extremist organization in modern Sinnoh, actually has their roots in a Hisuian organization known as the Galaxy Team. Unlike their modern-day incarnation, though, the Galaxy Team was a mostly benevolent organization which (in addition to essentially serving as the government of Jubilife Village) conducted groundbreaking research into Pokémon and fostered positive relationships between humans and Pokémon. They're a major reason that our world became what it is today!

Honestly, it's a bit disheartening to hear about all the cool things that the Galaxy Team did, and then be reminded of what Team Galactic is like...

anyways here's a pic of me and some historical re-enactors i had a photo op with on my trip to Sinnoh

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Western Beauty

Western wear is a category of men's and women's clothing which derives its unique style from the clothes worn in the 19th century Wild West. It ranges from accurate historical reproductions of American frontier clothing, to the stylized garments popularized by Western film and television or singing cowboys such as Gene Autry and Roy Rogers in the 1940s and 1950s. It continues to be a fashion choice in the West and Southwestern United States, as well as people associated with country music or Western lifestyles, for example the various Western or Regional Mexican music styles. Western wear typically incorporates one or more of the following, Western shirts with pearl snap fasteners and vaquero design accents, blue jeans, cowboy hat, a leather belt, and cowboy boots.

Hat

Lawman Bat Masterson wearing a bowler hat.

In the early days of the Old West, it was the bowler hat rather than the slouch hat, centercrease (derived from the army regulation Hardee hat), or sombrero that was the most popular among cowboys as it was less likely to blow out off in the wind.The hats worn by Mexican rancheros and vaqueros inspired the modern day cowboy hats.By the 1870s, however, the Stetson had become the most popular cowboy hat due to its use by the Union Cavalry as an alternative to the regulation blue kepi.

Stampede strings were installed to prevent the hat from being blown off when riding at speed. These long strings were usually made from leather or horsehair. Typically, the string was run half-way around the crown of a cowboy hat, and then through a hole on each side with its ends knotted and then secured under the chin or around the back of the head keeping the hat in place in windy conditions or when riding a horse.

The tall white ten gallon hats traditionally worn by movie cowboys were of little use for the historical gunslinger as they made him an easy target, hence the preference of lawmen like Wild Bill Hickok, Wyatt Earp and Bat Masterson for low-crowned black hats.

Originally part of the traditional Plains Indian clothing, coonskin caps were frequently worn by mountain men like Davy Crockett for their warmth and durability. These were revived in the 1950s following the release of a popular Disney movie starring Fess Parker.

Shirt

1950s style Western shirt with snap fastenings of the type popularized by singing cowboys

A Western shirt is a traditional item of Western wear characterized by a stylized yoke on the front and on the back. It is generally constructed of chambray, denim or tartan fabric with long sleeves, and in modern form is sometimes seen with snap pockets, patches made from bandana fabric, and fringe. The "Wild West" era was during the late Victorian era, hence the direct similarity of fashion.

A Western dress shirt is often elaborately decorated with piping, embroidered roses and a contrasting yoke. In the 1950s these were frequently worn by movie cowboys like Roy Rogers or Clayton Moore's Lone Ranger. Derived from the elaborate Mexican vaquero costumes like the guayabera, these were worn at rodeos so the cowboy could be easily identifiable. Buffalo Bill was known to wear them with a buckskin fringe jacket during his Wild West shows and they were fashionable for teenagers in the 1970s and late 2000s.

Another common type of Western shirt is the shield-front shirt worn by many US Cavalry troopers during the American Civil War but originally derived from a red shirt issued to prewar firefighters. The cavalry shirt was made of blue wool with yellow piping and brass buttons and was invented by the flamboyant George Armstrong Custer. In recent times this shield-front shirt was popularised by John Wayne in Fort Apache and was also worn by rockabilly musicians like the Stray Cats.

In 1946, Papa Jack Wilde put snap buttons on the front, and pocket flaps on the Western shirt, and established Rockmount Ranch Wear.

Coat

When a jacket is required there is a wide choice available for both linedancers and historical re-enactors. Cowboy coats originated from charro suits and were passed down to the vaqueros who later introduced it to the american cowboys. These include frock coats, ponchos popularised by Clint Eastwood's Spaghetti Westerns, short Mexican jackets with silver embroidery, fringe jackets popular among outlaw country, southern rock and 1980s heavy metal bands, and duster coats derived from originals worn in the Wild West. More modern interpretations include leather waistcoats inspired by the biker subculture and jackets with a design imitating the piebald color of a cow. Women may wear bolero jackets derived from the Civil War era zouave uniforms, shawls, denim jackets in a color matching their skirt or dress, or a fringe jacket like Annie Oakley.

For more formal occasions inhabitants of the West might opt for a suit with "smile" pockets, piping and a yoke similar to that on the Western shirts. This can take the form of an Ike jacket, leisure suit or three-button sportcoat. Country and Western singer Johnny Cash was known to wear an all-black Western suit, in contrast to the elaborate Nudie suits worn by stars like Elvis Presley and Porter Wagoner.The most elaborate western wear is the custom work created by rodeo tailors such as Nudie Cohn and Manuel, which is characterized by elaborate embroidery and rhinestone decoration. This type of western wear, popularized by country music performers, is the origin of the phrase rhinestone cowboy.

Trousers

Cowboy wearing leather chaps at a rodeo

A Texas tuxedo comprising a denim jacket, boots and jeans.

In the early days of the Wild West trousers were made out of wool. In summer canvas was sometimes used. This changed during the Gold Rush of the 1840s when denim overalls became popular among miners for their cheapness and breathability. Levi Strauss improved the design by adding copper rivets and by the 1870s this design was adopted by ranchers and cowboys. The original Levi's jeans were soon followed by other makers including Wrangler jeans and Lee Cooper. These were frequently accessorised with kippy belts featuring metal conchos and large belt buckles.

Leather chaps were often worn to protect the cowboy's legs from cactus spines and prevent the fabric from wearing out.Two common types include the skintight shotgun chaps and wide batwing chaps. The latter were sometimes made from hides retaining their hair (known as "woolies") rather than tanned leather. They appeared on the Great Plains somewhere around 1887.

Women wore knee-length prairie skirts,red or blue gingham dresses or suede fringed skirts derived from Native American dress. Saloon girls wore short red dresses with corsets, garter belts and stockings.After World War II, many women, returning to the home after working in the fields or factories while the men were overseas, began to wear jeans like the men.

Neckwear

Working cowboy wearing a bandana or "wild rag," 1880s

During the Victorian era, gentlemen would wear silk cravats or neckties to add color to their otherwise sober black or grey attire. These continued to be worn by respectable Westerners until the early 20th century. Following the Civil War it became common practice among working class veterans to loosely tie a bandana around their necks to absorb sweat and keep the dust out of their faces. This practise originated in the Mexican War era regular army when troops threw away the hated leather stocks (a type of collar issued to soldiers) and replaced them with cheap paisley kerchiefs.

Another well-known Western accessory, the bolo tie, was a pioneer invention reputedly made from an expensive hatband. This was a favorite for gamblers and was quickly adopted by Mexican charros, together with the slim "Kentucky" style bowtie commonly seen on stereotypical Southern gentlemen like Colonel Sandersor Boss Hogg. In modern times it serves as formal wear in many western states, notably Montana, New Mexico

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The other night I had a dream that Sam carried me around a museum that showed different historical events.

In one large room, there was a battle in Rome with historical re-enactors. It felt like a real battle. Almost like a snapshot of the past. Everything was on fire. People screamed. I tried to push through everyone, but the crowd of costumed soldiers was too large and too dangerous. I flew and perched on top of a piller to avoid getting maimed.

Sam took me away from the room and carried me through a marble hallway. I tried to wriggle out of his grasp, but I went limp. He loves to carry me around like I’m a child and I hate it.

I set myself on fire to make him drop me. I grabbed him by the head to melt his face. He screamed and struggled for a bit, but he paralyzed me.

I tried to regain control of myself, but it felt like my muscles were being torn apart.

As he carried me, I cursed at him and told him how much I hate him.

This annoyed him and he became more serpentine. His neck elongated like a rokurokubi. It felt like he wrapped himself around me like a snake, constricting my attempts to break free from paralysis. His voice became a quiet hiss in my left ear.

His attempts to intimidate me never work because I know I can wake myself up at any time. All pain is temporary and he has no control over my ability to leave. The more pain he makes me feel, the more likely I am to wake up myself up.

Occasionally, he will throw me into another dreamscape. I run and hop through these worlds until I reach an exit to consciousness. The most effective way to exit a dreamscape is through a mirror or painting. If he takes away mirrors and paintings, a window will do in a pinch.

He plays a delicate game of trying to intimidate me while also keeping me unaware of my physical body.

I can never control him in my lucid dreams, but I can control my own body. If the body becomes too stressed in a dream, it will wake up. If you jump from a high place, your fear of falling will wake you. I do whatever I can to make myself stressed.

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

that's so cool! i love the hat especially. you're so creative. this isn't a question so much as invitation to infodump about historical fashion (or anything really!) - 🪴

thank you!

tldr included because hooh boy when i infodump i sure do infodump.

TL;DR: this made me realize I'd probably enjoy being a historian, museums are cool, secret pants supremacy, and according to one dressmaker guide, women should not have a pocket less than 14 inches long and eight inches wide.

I've loved history since I was little. I used to visit the state museum almost every week till I was around eight. I would always love looking at the diorama exhibits, it helped me feel less divorced from the people who lived long ago. I especially loved the children's area, where you could touch animal bones and furs, work on a fake archaeology site, and look at bugs under a microscope! I've also visited some historical re-enactment sites and villages, and they were almost magical to me. I'd love to be a re-enactor one day, but I don't know if I'd want it to be a long-term job.

Around the beginning of last summer, I discovered historical fashion, and it was like my love of history had been reborn. The late Victorian to early Edwardian era immediately became my favorite because of its silhouette. I started watching a lot of dress historians on youtube, especially Bernadette Banner. I was also beginning to define my own personal style, so this new information hit me at the perfect time.

The Victorian era lasts a long time in history, so you can imagine many different styles when you think of "victorian fashion" you could be thinking of bustles, hoop skirts, or long trains, all victorian women's fashion! By the victorian era, men's fashion was really boring and stayed relatively similar through the decades. Small changes would take place, but those changes were much harder to spot. While I love a nice Edwardian men's suit, I know more about women's fashion than I do men's.

Clothes back in the day were outrageously expensive even for the wealthy. You needed to acquire fine imported fabrics and silks if you were a lady of high society, and silk was so expensive that wealthy ladies would shamelessly wear pieced garments (where a panel of clothing is constructed from several scraps sewn together instead of one singular panel to conserve fabric) Women would re-wear dresses as long as they could, having the same gowns remade into the latest fashions rather than commissioning new ones. Besides getting their dresses reworked, there would often be new undergarments for each new silhouette, with the iconic Gibson girl figure sometimes faked by padding, ruffles, or entire boned undergarments designed to be worn along with one's corset. Even models of the time would doctor their photos to make their waists look impossibly small. Fun fact: the popular late Victorian silhouette was defined as a ratio that could be achieved through any means one might think of, including all of the aforementioned methods. With the Edwardian era came the bicycle, and particularly the acceptance of women riding bicycles and participating in sports. special sports corsets were produced, and while cycling became immensely popular, wearing trousers or pants was frowned upon by ladies of society. Attempting to bicycle in a skirt proved to be a dangerous and deadly task for women, so the split skirt was invented. The split skirt is essentially a baggy pair of pants that could be passed off as a skirt to the rest of the world. Some had button-down panels in the front that concealed the crease in the front of the skirt, but others left the front buttonless. I am a believer in split-skirt supremacy, the only other garments that come close to beating my love of split skirts are waistcoats and ulster jackets (aka Inverness coats)

I think this is where I'm going to stop, mainly because I'm running out of coherent thoughts but I very much love historical fashion, and tbh I would love for my future job to be thinking about history all the time

#clique secret santa 2022#vee talked here#historical fashion#history rambles#i could have put so many pictures in here if i wasn't tired rn#long post

0 notes

Text

The Ending of Black Sails

I keep seeing a lot of people posting about how pissed they are about how things ended in Black Sails. How there was no closure, about how the war ended, about how so many of the characters got screwed over and lost so much after coming so far etc

But the thing is... We knew how it ended going in. Flint Dies, (if you read Treasure Island, he canonically dies in Georgia of drink calling for ‘Darby McGraw, fetch aft the rum’ Georgia was a penal colony. so... as far as source material goes... that makes sense. Billy is, when we meet him in Treasure Island, ostracized and Hunted by Flint’s Crew, and Silver. Silver is running an inn with an African wife. (Madi)

As for the historical pirates...

Rackham and Anne and ‘Mark Read’ are dead/ disappeared at that point

Blackbeard is dead, via brutal fight as opposed to keelhauling, which pissed off some of my re-enactor friends.

Vane is long hanged, as seen in the show

Black Sails is not a happy ending story. it was never supposed to be.

The Age of Pirates began with the end of a war, and society’s callous castoff and usage of its lowest class, and their turning to piracy. Like in the prologue, Society brands them ‘Enemies of all Mankind’ and the pirates decree ‘War Against the World’ it ends with pirates either going whimpering ignominiously into the night like Hornigold, or Gloriously into History like Blackbeard.

It was never a happy ending show. It was a tough, struggle tooth and nail claw desperately to survive show, just look at the fight scenes, and then it ends with the Death of their Era, and the death of their way of life. It was always, always about the desperate struggle to make ones way in the world, and the failure that came of the Pirate Republic of Nassau. Somewhere in the interviews and stuff, they talk about the theme music, and the hurdy gurdy, giving off an erie hum cause it was damp that day. ‘These are broken, damaged men, in a broken damaged society’ and case in point, the final scene of the epic, and wholly iconic opening credits, is a man climbing to the peak of the mast with a skeleton. Doom pirates, on a doomed ship.

But my God. What a ride. If we have to be left with this, with everything Black Sails gave us, and took from us... remember this... in the final scene, when Rackham ponders his ‘legacy’ and we SEE his legacy, his flag, which became synonymous with piracy, which was used by other fictional pirates as Hook, Barbossa, and dozens of others, we are left with this. the legacy of their legends. In the end, the motto of the Bahamas under Woodes Rogers was ‘pirates expelled, commerce restored’ But not a single one of us sings Woodes Roger’s praises. his historical, or fictitious image. We all instead, celebrate Vane, Rackham, Flint, Teach and Silver.

Black Sails Ends as it began, and as History went. Desperate men, making a desperate Fortune, fighting a losing war against the society that made them desperate in the first place.

As Hornigold says, “In the end are all just thieves, awaiting a noose.”

But as Rackham says in turn, "A story is true. A story is untrue. As time extends, it matters less and less. The stories we want to believe, those are the ones that survive, despite upheaval and transition and progress. Those are the stories that shape history."―Jack Rackham

Long Live The Legend of Piracy. Raise the Black

#Black Sails#black sails starz#Calico Jack#Jack Rackham#Anne Bonny#Blackbeard#Edward Teach#Captain Flint#Billy Bones#Treasure Island#Long John Silver#John Silver#Caribbean#Golden Age of Piracy#Charles Vane#Nassau#woodes rogers#pirates#pyracy#famous pirates#epilogue#ending#Black Sails ending#caribbean piracy

438 notes

·

View notes

Note

Can you draw what a female Inca Empire would look like?

Hope you like it anon! Clothes from the Inca Empire are really gorgeous, and the patterns are so dazzling (even if I struggled to draw them shdjfkksbjdkbjfs)

Historical Footnotes:

This outfit is based on a combination of costumes of Inti Raymi’rata historical re-enactors (specifically, those of the chosen women or Aqllakuna, popularly called "Virgins of the Sun") and museum textiles and clothes.

Aqllakuna were a form of human tribute collected throughout the Inca Empire, or as they called themselves, Tawantinsuyo; they were selected from their families and communities at a young age and performed various services and functions for the Empire. They produced luxury items, wove fine cloth, brewed chicha (beer) for religious festivals, prepared ritual food, and some were selected as human sacrifices for religious rites. Some were given in marriage to men who’d distinguished themselves in service to the empire, but others lived out their entire lives without marrying.

Inti Raymi’rata is a traditional religious ceremony in honor of the sun god Inti, the most venerated deity in the religion; it was a celebration of the winter solstice as well as serving as a New Year. It lasted for nine days and was filled with colorful dances and processions and animal sacrifices to thank the gods. It’s still celebrated by the indigenous people of the Andes, and in 1944, the celebration was historically reconstructed by indigenous actors. Since then, a theatrical reenactment of the festival has taken place in Sacsayhuamán every year. Their costumes were massively helpful for this!!

Cloth played a huge cultural and economic role in the Empire. There were many different grades of cloth and they all had different usages. Qompi is the most high quality and they were reserved for the nobility and the royal family. Qompi was divided into two categories- those for the tribute, and those for royal and religious function.

The production of Qompi cloth was produced in state-run institutions called Akllawasi. Aqllakuna wove cloths for the nobility and clergy whereas a full-time body of male weavers called qumpicamayocs produced qompi cloth for the state.

Qompi were made from remarkably fine materials, so much so that the Spanish described them as silk. Their fabric could have a thread count of more than 600 threads per inch, higher than than that of European textiles of the time; this feat would not be surpassed until the Industrial Revolution.

Women wore a long dress that reached the ankle called anaku, and was held around the waist by a broad belt or sash called a chumpi. A shawl/mantle known as lliclla was worn over the shoulders and was fasted with tupu pins made of copper, bronze, silver, or gold, sometimes reinforced with tying string. The mantle could be and was used as a carrying device for daily tasks. The Empire was an far-spanning empire of course, so there was lots of geographic variation with the clothes worn throughout the region. Indigenous women in the area today still wear llicllas, though with European influenced patterns and colors and safety pins!

(Man I had to do some guess work about how two tupu pins fastened a lliclla cuz most women just use safety pins nowadays, and I saw only three or one tupu pin being used on the costumes at Inti Raymi almost never two?)

The primary colors used in textiles were black, white, green, yellow orange, purple and red; blue is rarely present. It was within that range that I chose the colors for her headdress! These colors were created from natural dyes extracted from plants, minerals, insects, and mollusks. Colors had specific associations- for example, red was associated with conquest, rulership, and blood. Purple, as in the rainbow, was considered the first color and is associate with Mama Ocllo, the mythological mother of the royal lineage and the dominant ethnic group of the Empire.

Both men and women wore cloth hats or headbands which could indicate status from their decorations and adornments. This hat was one I saw on the aqllakuna reenactors at Inti Raymi, and I couldn't really find any information about it?

Unfortunately, I couldn't find any pre-columbian llicllas to reference patterns for. The reason we have such a limited amount of textiles from Tawantinsuyo is that they burned many of their textiles to prevent the Spanish from gaining them. I referenced the pattern of the lliclla here on an royal tunic dating to 1440 and 1540. It's remarkable for the sheer amount of patterns and designs it uses, and was probably worn by the Sapa Inca himself!

Geometric designs were very popular, especially checkerboard motifs; in a checkerboard pattern, they repeat patterns in small rectangular units known as tocapus. Only people of high rank were allowed to wear tunics with tocapus, most of them incorporating only a limited amount of them. Therefore, the enormous status of the wearer is shown by the large number of tocapus and their diverse and detailed designs. Some of the tocapus’ designs may hold special meaning but this remains debated by scholars. However, I will speculate a little about one specific design- this t’oqapu pattern greatly resembles that of a standard military tunic, so it might be a symbol of military prowess and strength?

Animals were often depicted abstractly. Textile patterns and designs could be specific to a community or a family group, and could serve as a representation of a community and their cultural heritage. Part of the Empire’s strategy of domination was imposing standard imperial designs and forms, but they also allowed for local traditions to maintain their preferred forms.

#historical hetalia#hetalia#hetalia ocs#hws inca empire#Anonymous#WOWEE THIS IS LONG#imo i imagine Tawantinsuyo as male so i guess this is a nyo?#oh whale#man there is like no information on makeup or cosmetics in the inca empire smh#historically inaccurate hair is historically inaccurate#ask#aph inca empire

256 notes

·

View notes

Text

Theorizing about MacFrights in Canon and also about What Is the Last Resort

I ate too much on break time so now I have spare time at lunch, idk I'll write about this theory simmering in my mind

Tl;dr Mac is likely an actor. The Last Resort is...well... A resort, with many cool attractions, and its sad we only saw it used as a trap for Luigi & co.

While I have specific headcanons for the version of Mac I ship Marv with, I do like to think and theorize about a more "canon" Mac, something closer to what he's like in game that is.

To which I say he's most likely just a re enactor, enthused about and dedicated to his role as "king" of the "castle."

In his concept art, the castle used to have a banner reading "KNIGHT FOR A DAY" along with blatant ticket stands putting the floor out to be an attraction for guests. Everyday Renaissance fair lol. The banner was removed in the final version, but they still kept the ticket stand (or something similar) and cheesy fanfair through the speakers upon arrival. Which makes me wonder if they decided to change his 'backstory' or just make it less obvious? I'm leaning towards the latter. If they wanted to make him out to be real royalty, I figure they would take out the cheesy fanfair and stand y'know.

So we have a funky lil ghost guy pretending to be King for entertainments sake, probably grabs a coffee later at the shops off hours.

But of course the Castle MacFrights isn't the only attraction the Last Resort has to offer. They got fine music! Explore overgrown jungles... See spectacular movies... Historical museum, tricks and gym and dance and more!

The Last Resort is...well... A resort! Like Nickelodeon Suits you may see advertised sometimes. They got like a whole waterpark and restaurants while also being a place to stay with rooms and such. Like that!

And it's sad we only see it as just a trap, an elaborate ruse to capture E.Gadd and Luigi for King Boo, orchestrated by Hellen. It'd been cool to see like, guests walking around and having a good time around the floors. It's interesting to imagine how cool it could have been if we got to see it open to the public 😔

#txt#luigi's mansion 3#lm3#lm3 king macfrights#lm3 macfrights#lm3 headcanons#theory?#luigi's mansion#luigis mansion#luigis mansion 3

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Medieval mince pies - a recipe

Since I am making a reference to this in chapter 6 of It’s Beginning To Look A Lot Like... I thought I’d make it available so people can try it if they like! Not suitable for vegetarians and vegans, I’m afraid, but the rest of you, I can highly recommend it - they’re delicious! Recipe courtesy of my brilliant colleague John, a historical re-enactor in his spare time (and sometimes in work time, too).

Mynced Pies probably date from the 13th century when the main ingredients were shredded meat (often mutton or beef), suet and dried fruit. The addition of spices such as nutmeg, cinnamon and cloves is said to symbolise the gifts of the Magi. The addition of expensive ingredients such as dried fruit and spices means that these pies would have been something very special.

Ingredients:

For the Myncemeat

300g minced pork

1 tbsp white wine vinegar

150g dates (chopped small)

1/2 tsp ginger

150g currants

1/2 tsp pepper

150ml red wine

1/2 tsp salt

6 egg yolks (beaten)

1/4 tsp cloves

5 threads saffron (soaked in 1 tbsp warm water)

1/4 tsp mace

To make the Myncemeat

Mix all of the ingredients thoroughly in a large, non-metallic mixing bowl, adding the spices last, so that no one ingredient is clumping together.

Cover the bowl with cling film and place in a fridge for 3 days to allow the flavours to develop. Stir once a day. Use within 3 days.

For the hot water pastry (makes just over 750g of pastry)

475g flour (half strong and half plain) 125ml boiling water

75g unsalted butter 1½ tsp salt

100g lard or dripping

To make the Hot Water Pastry

Caution: hot fat can be dangerous - follow the instructions carefully.

Rub 75g butter into the flour until the mixture resembles breadcrumbs.

Place 100g lard in a large saucepan and heat until it melts. DO NOT OVERHEAT. The lard should not be heated to more than 30-40oC.

Remove the pan from the heat and carefully add 125ml of boiling water.

Add the salt and stir until it dissolves. Pour this mixture over the flour and work quickly into a dough. Use a knife while the mixture is hot and then, as soon as it is cool enough, work the dough well with your fingers until it is mixed evenly.

Press the dough out on to a plate, cover with cling film and leave until it reaches room temperature

Lightly flour the work surface, roll the dough to about ¾ cm thick, fold it in on itself by thirds, then repeat this roll and fold again. Leave the dough to rest for 20 minutes in a cool place before using.

To make the Mynced Pies

This is the easiest rather than the most traditional way and works very well. It will look quite straight-sided before baking, but will develop the traditional bulging sides as it bakes.

To shape your pastry dust the base of an upturned glass or jar (approx 10cm in diameter) with flour.

Roll a large handful of dough to about 20cm square and cut it into discs slightly larger than the base of the jar.

Lay the pastry over the jar evenly so that the edges drape down. Now press the dough tightly in against the sides, working it smooth with your fingers to remove any pleats of the pastry, and allowing the sides to stretch to about 3cm in depth.

Place the jar in the fridge for 5 minutes to set. Once the pastry is slightly firm, remove from the fridge and carefully prise the dough away from the jar with a blunt knife.

Carefully pack the pastry shell with mincemeat, then cut another slightly smaller disc from the pastry for the lid. Brush a little water around the inside top of the pastry shell, then lay the pastry lid over.

Press the lid down so that it sits tightly against the meat, and up to the edge of the shell. Use your thumb and forefinger to pinch the edges together.

Brush the lid and lip of the pies with beaten egg and cut a hole in the centre for the steam to escape. Chill the pies for an hour before baking.

To cook the pies, heat the oven to 200ºC (180ºC fan-assisted) and bake for 30-35mins or until the pork is cooked through.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Clashing Storm of Shields - Fighting in the Shield Wall (Part 1: Background)

I think I promised @warsofasoiaf a write up on shield wall combat nearly two years ago now but, after several different versions that each took a slightly different approach, I’ve finally nailed down something that works for me.

As my small introduction has become a rather large post, I’ve decided to split the subject into two sections: a section on the background (introduction, recruitment and organisation, equipment) and a section on how the battle actually took place. I’m posting the first section now, and will post the second in a couple of weeks.

Introduction

I.P. Stephenson once wrote that “the single most defining ideological event in Anglo-Saxon warfare came at Marathon in 490 B.C.”. This comment, and all the assumptions that go with it, highlights the single biggest problem people have in understanding combat in the Early Middle Ages. The uncritical application of Classical scholarship to the medieval world, and a failure to up with the current academic consensus, has significantly distorted how many historians think about shield wall combat.

For example, Gareth William suggests in Weapons of the Viking Warrior that the sax was especially useful in a close order, rim-to-boss formation and compares it to the gladius:

Roman legionaries fighting at close quarters were armed not with a long sword, but with a gladius, or short-sword, which was primarily a thrusting weapon, requiring a minimum of space between the individual soldiers in a line.

The problem with this assumption, leaving aside the fact that weapon sized saxes were rare to the point of non-existence in 9th-11th century Scandinavia and that gladius length saxes weren’t particularly common in Anglo-Saxon England either1, is that the famous Roman short sword wasn’t used for thrusting in a close order formation. Instead, it was used for both cutting and thrusting in open order, with each man taking up 4.5-6 feet of space2. It’s not until open order fighting was abandoned completely and the long spatha was universally adopted by the infantry that we hear of the thrust being the preferred method of combat by the Romans3. An assumption, almost certainly based on scholarship from before 2000, has been made about how the Romans fought and how it might be applied to Anglo-Saxon warfare, but no examination of the different context or more recent scholarship has been performed, leading to the wrong conclusion.

(The Bayeux Tapestry)

Similarly, it’s common in historical fiction set in the Early Middle Ages to feature battles that rely very heavily on Victor Davis Hanson’s The Western Way of War4. For example:

We in the front rank had time to thrust once, then we crouched behind our shields and simply shoved at the enemy line while the men in our second rank fought across our heads. The ring of sword blades and clatter of shield-bosses and clashing of spear-shafts was deafening, but remarkably few men died for it is hard to kill in the crush as two locked shield-walls grind against each other. Instead it you cannot pull it back, there is hardly room to draw a sword, and all the time the enemy’s second rank are raining sword, axe and spear blows on helmets and shield-edges. The worst injuries are caused by men thrusting blades beneath the shields and gradually a barrier of crippled men builds at the front to make the slaughter even more difficult. Only when one side pulls back can the other then kill the crippled enemies stranded at the battle’s tide line.

Bernard Cornwell, The Winter King

Other works, such as Giles Kristian’s Blood Eye and Edward Rutherfurd’s The Princes of Ireland, follow the same pattern of a physical collision between the two formations and a shoving match where weapons are almost secondary. This is a core concept of the traditional model of hoplite combat - the literal othismos (”push”) - that has been likened to a rugby scrum since the early 20th century. Ironically enough, VDH is a great pains to emphasize the unique nature of the Greek phalanx due to the hoplite shield, so even without the doubts of A.D. Fraser, Peter Krentz and all the other “Heretics” it would be questionable to apply this method of warfare to the Early Middle Ages5.

When you examine the differences between the two periods, for example the early Anglo-Saxon shields are often no more than 40cm in diameter and featuring spiked or “sugar loaf” bosses6, it becomes clear that the use of Greek warfare to represent 5th and 6th century warfare is incorrect. Similarly, the difference in construction between the aspis and Scandinavian shields of the 9th and 10th centuries, the aspis having thickly reinforced rims while the Scandinavian shields either taper towards the edges or remain very thin (<10mm), should offer a similar caution7.

In spite of the litany of criticisms I’ve just provided, it’s still necessary to refer back to our understanding of Greek and Roman warfare when examining combat in the Early Middle Ages, for two main reasons. Firstly, and most importantly, the sources are much more detailed about how fighting was carried out and were very often written by men who had themselves fought. While authors of the Early Middle Ages were not necessarily unfamiliar with warfare, they were remarkably uninterested in recording much in the way of details and there’s frequently little useful information to be extracted from accounts of battles.

Secondly, a far larger body of work exists on the how of Ancient hand-to-hand combat. While re-enactors of the medieval period are certainly numerous, perhaps even the most numerous of the pre-modern re-enactor, the sheer output of Greek and Roman re-enactors and the scholars who mine them for insights dwarfs that of medieval re-enactors and, on the whole, is more likely to be up to date with the scholarship of the field in general.

My goal here is to make the best possible use of sources on both Ancient and Medieval warfare in order to present a picture that is as close to a plausible reconstruction as I can manage. I don’t mean for this to be authoritative, and my views do in some cases differ from those of some re-enactors or academics, but I do hope you find this post a useful resource in your writing.

(This? This is what not to do.)

Trees of the Spear-Assembly: Who Were the Warriors?

One of the most important things in understanding combat in the Early Middle Ages is knowing who was doing the fighting and why, since this has a big impact on the way in which they fight, and with how much enthusiasm. In particular, the question of whether they were just poor farmers levied en masse or wealthier members of society who had both military obligations and the culture of carrying them out is an important one, as quite often this is used to demonstrate the difference between two sides.

The answer to the question is that, by and large, men who fought were freemen of some standing, if not always considerable landowners, and wealthy by the standards of their people. I emphasize the concept of relative wealth for good reason, and I’ll get into that as we have a look at the basic structure of the “armies” of the period.

Generally speaking, armies of the Early Middle Ages, across almost all of Europe, consisted of two elements: the Household (hirð, hird, comitatus, etc) and the Levy (fyrd, lið, exercitus, etc). I use “levy” here as a shorthand for any force composed of freemen who are not regularly attached to the household of a major landholder, as they were not usually assembled into a single coherent force with 100% unified command, but I do want to note that there would be a significant difference in the unity of an army made up of regional levies and one made up of lið (individual warbands)8.

The status of those serving in the household of a powerful landholder could vary significantly, from slaves to the sons of major landholders (although militarised slaves, it must be admitted, were rare outside of the Visigothic realm), and the more powerful the landowner the more likely the men of his household would be themselves descended from someone of considerable status. A significant portion could still be made up of poorer freemen who were sons of older warriors or whose family had some close connection to the major landowner.

For someone who maintained a large household, it was important that they present an image of being a wealthy as possible, and the best way to do this was to outfit the men of their household with every piece of military equipment that displayed status. So, whether he was descended from slaves or was the son of a family who owned a thousand acres, once a man had sworn their oath of loyalty to their new patron, they could be expect to be equipped with all the trappings of a warrior. This might only be symbolic in poorer regions (a fancier sword, a specific type of ornament, etc), especially if the landowner already had a number of armoured retainers, but it bound the different levels of freemen together into a single group.

Generally this oath swearing would occur after a youth had spent several years in the household of their future patron, where they would learn all the necessary skills of a warrior, such as riding, hunting, shooting a bow, using a sword and fighting with spear and shield. These youths probably participated in battles as auxiliaries with bows and javelins and only joined the ranks of the shield wall when they were considered full warriors, but we have only have very limited information on this point.

The status of men of the levy or warband varied to a much smaller degree. They were, in almost all cases, free and relatively wealthy by the standards of their region, although you do see a bit more of a variation in warbands, which might have members from a half dozen regions and many more backgrounds. In comparison, any army raised in defence of a region or raised from a region is going to consist entirely of free men and the majority of these will be fairly wealthy.

Simply put, even basic military equipment was sufficiently expensive that farmers who merely had enough land to sustain their family9 weren’t going to be able to afford much more than an axe, shield and spear or, depending on their region, a bow and 12-24 arrows. This is consistent across the Carolingian, Lombard and Scandinavian world during the 8th-11th centuries and, given the mostly aristocratic nature of warfare in Anglo-Saxon England, was likely true there as well10.

Basic military equipment, however, was not what rulers looked for when summoning forces for external wars or internal defence. We know from the capitularies of Charlemagne that only a man with four estates was required to arm and equip himself for service and that, with one exception, only men with one estate or more were required to pitch in to help equip one of their number for service11. Moreover, these estates weren’t even all the land the freeman held, just the lands he held which had unfree tenants, so that a “poor” freeman who merely had his own personal land was excluded from military service12.

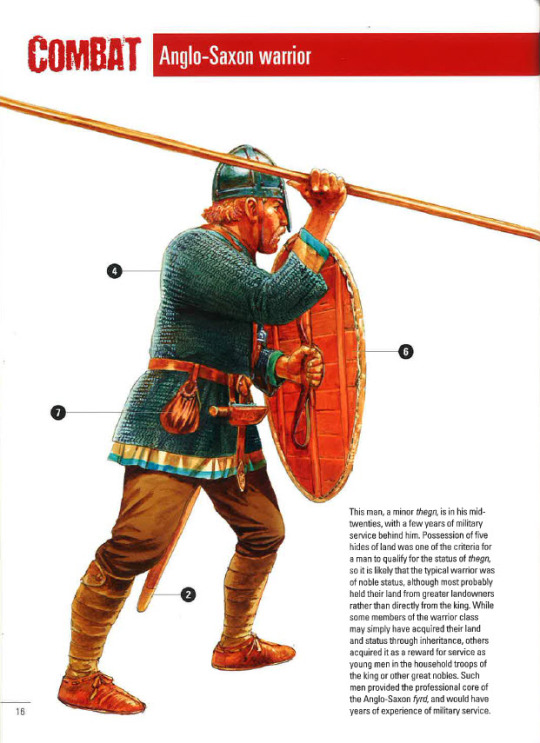

(The average Anglo-Saxon fighting man)

Much the same situation appears in mid-8th century Lombardy, where king Aistulf demanded that those who had 7 or more properties worked by unfree tenants should perform service with a horse and full equipment, while those with less than this, but who own more than 25 acres (40 iugera) of their own, were required to perform an unarmoured cavalry service. 25 acres is about half the land later Anglo-Norman evidence suggests is the minimum for unarmoured cavalry service, so possibly this was an attempt on Aistulf’s part to enfranchise the lesser freemen and get them to support his usurpation of the crown at the political assembly13. Note, however, that the minimum level for cavalry service is nearly double what a peasant family would need to subsist off and implies a man of moderate wealth in and of itself14.

England is somewhat different, as we lack any specific requirements for those being summoned to military service, but from at least 806 we can surmise that 1 man from every 5 hides of land was required for the army. By this point a “hide” wasn’t a measure of area but of value, approximately £1, in a time when 1d. was the wage of a skilled labourer15.

The implications of this aren’t immediately obvious, but when you consider that Wessex had a population of perhaps 450 000 people, across an area of 27 000 taxable hides, only 5400 men (1 man from every 20 families) were actually required for military service16. Many of these, perhaps even most, would have belonged in the retinues of major landholders as either part of their household or as landed warriors owing service to the landholder in exchange for their land. In the same vein, the one man from every hide who was required to maintain bridges and fortifications, as well as defend the burhs (not serve in the field!), was drawn on the basis of something like 1 man for every 4 families. These are heavy responsibilities, but still far from men with sickles and pitchforks making up the fyrd.

There are some exceptions, or else cases where the evidence is thin enough that it’s difficult to say one way or the other, and these typically occur in areas that a less densely populated and less wealthy. The kingdom of Dal Riada in the seventh century, for instance, raised about 3 men from every 2 households for naval duties, although it might also have called out fewer warriors from the general population of the most powerful clan for land warfare17.

(A replica of the Gokstad ship)

Scandinavia is somewhat trickier, since a lot of the sources are late and from a period where central authority existed. We know from archaeological evidence that, in Norway, large scale inland recruitment of men for naval expeditions had been occurring since the Migration Era, as the number of boathouses exceeds the best estimates of local populations18. These were initially clustered around important political and economic centers, but spread out more evenly across Norway during the middle ages as a central political authority arose. This system is likely at least one part of the origin for the leidang system of levying ships, which seems to have properly formed in Norway and Denmark during the late 10th or early 11th century as a result of royal power becoming strong enough to call out local levies across the whole kingdom19.

It seems likely, based on later law codes and other contemporary societies, that Scandinavian raiders during the 8th and 9th centuries were mostly the hird of a wealthy landowner (or their son), supplemented with sons of better off farmers from nearby holdings. Ships were comparatively small at this point, just 26-40 oars (approximately 30-44 men)20, and most had 24-32 oars per ship. This corresponds fairly well with what a prominent landholder might be able to raise from his own household, with additional crews coming from the sons of nearby farmers, although whether this was voluntary, coerced or some combination of the two is impossible to say21.

However, these farmers’ sons, while unlikely to wear mail in the majority of cases, should not be thought of as poor. The vast majority of farmers in 8th-10th century Scandinavia would have had one or two slaves and sufficient land to not only keep their slaves fed and employed, but also to potentially raise more children than later generations22. These farmers’ sons might have been “poor” by the standards of the men they faced in richer areas of the world, but they were rather well off by the standards of their society.

Later, after the end of the 10th century, the leidang was largely controlled by the king of the Scandinavian country and, particularly in the populous and relatively wealthy Denmark, poorer farmers were increasingly sidelined from any obligation to provide military service. Ships also rose in size from the end of the 9th/start of the 10th century, regularly reaching 60 oars for vessels belonging to kings or powerful lords, and even the “average” size seems to have gone from 24-32 oars to 40-50 oars23.

Slaughter Reeds and Flesh Bark: Arms and Armour of the Warrior

The equipment of the warrior consisted of, at its most basic level, a spear and a shield. For those who belonged to a poorer region, a single handed wood axe might serve as a sidearm, or perhaps even just a dagger, while in wealthier regions the sidearm would generally be a sword or a specialised fighting axe24. In an interesting twist, both the poorest and the wealthiest members of society were almost equally likely to use a bow, although I expect that the poorer men mostly used hunting bows, while the professional fighting men used heavier warbows25.

Spearheads, at least from the 7th-11th centuries, were relatively long (blades of >25cm) and heavy (>200g), but most were well tapered for penetrating armour. Some, especially the longest examples, weighed around a pound, but were probably still considered one handed weapons26. Others, however, weighed in excess of two pounds and must have been two handed weapons, possibly the “hewing spear” mentioned in some 13th century sagas27. Javelins, too, appear to have tended to feature long, narrow blades that would have made them a short range weapon, while also providing considerable penetration within their ~40 meter range.

Swords, for their part, were not quite the heavy hacking implement once attributed to them, but also aren’t quite as well balanced as later medieval swords would be. Early swords, before the 9th century, tended to be balanced about halfway down the blade, which might make for a more powerful cut, but didn’t do much for rapid recovery or shifting the blade between covers. However, from the mid-9th century, the balance shifted back towards the hilt, which made them much faster and more maneuverable28. This may indicate a shift towards a looser form of combat, where sword play was more common, or it might indicate nothing more than a stylistic choice. After all, the Celts of the 2nd-1st century BC preferred long, heavy, poorly balanced swords for fighting in spite of relying on the usual Mediterranean “open” style of combat29.

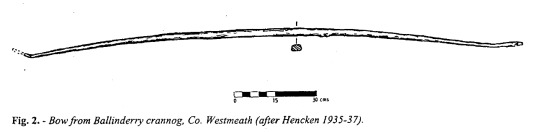

(The Ballinderry Bow)

Warbows, with a couple of exceptions, appear to have been short but powerful. Starting with the Illerup Adal bows, which most likely only had a draw length of 26-27″, we see a repeated pattern when very powerful bows are also much shorter than we expect them to be. In particular, the heavier of the two bows from Illerup Adal is very similar to the Wassenaar Bow, a 9th-10th century bow. A replica of the latter drew 106lbs @ 26″, making it quite a powerful bow, and similar bows have been found at Nydam, Leeuwarden-Heechterp and Aaslum. Only the Ballinderry and Hedeby bows break this trend, with both capable of being drawn to 28″-30″. In all cases, draw weights varied between 80lbs and 150lbs, although 80-100lbs is by far the most common30. The consequence of this is that the power of the bows is not going to be as high as later medieval bows, which were able to be drawn to 30″ and, as the arrows were also relatively light, suggests an energy of 40-60j under most circumstances. This is enough to penetrate mail at close range if using a bodkin arrowhead, but at longer ranges mail would have offered quite excellent protection.

When it comes to shields, there was evidently quite a bit of variation. Early Anglo-Saxon and Merovingian shields were quite small and light, about 40-50cm in diameter31, but later shields were generally 80-90cm in diameter. In particular, we have good evidence of viking shields generally fitting this description, although it’s less clear whether or not later Carolingian and Anglo-Saxon shields retained this diameter or reduced to 50-70cm in diameter (see f.n. 7). In all cases, however, the shield was fairly thin at the center, less than 10mm, and could be as low as 4mm thick at the edge. While thin leather or rawhide could be applied to the front and back of the shield to reinforce it, it’s equally possible that only linen was used to reinforce the shield, or even that the shields were without any reinforcement32.

Recent tests by Rolf F. Warming have shown that this style of shield is rapidly damaged by heavy attacks if used in a passive manner (as in a static shield wall) and that the shield is best used to aggressively defend yourself33. While the test was not entirely accurate to combat in a shield wall (more on this in the second part), it does highlight the relative fragility of early medieval shields compared to other, more heavily constructed shields like the Roman scutum in the Republican and early Empire or the Greek aspis. As I’ve said before, this means we have to rethink how early medieval warfare worked.

Finally, we come to the topic of armour. The dominant form of armour was the mail hauberk - usually resembling a T-shirt in form - and other forms of metal armour were far less common. Guy Halsall has suggested that poorer Merovingian and Carolingian warriors might have used lamellar armour34, and there is some evidence from cemeteries and artwork that Merovingian and Lombard warriors wore lamellar armour in the 6th and 7th centuries, but there’s little evidence to support lamellar beyond this. While it does crop up in Scandinavia twice during the 10th/11th centuries, it was almost certainly an uncommon armour that was used either by Khazar mercenaries or by prominent men who were using it as a status symbol35. Scale armour is right out, Timothy Dawson’s arguments aside, as there is no good evidence of it.

(Helmet from Valsgarde 8)

Helmets evolved throughout the Early Middle Ages, ultimately deriving from late Roman helmets that featured cheek flaps and aventails. During the 6th and 7th centuries, especially in Anglo-Saxon England and Scandinavia, masks were attached to the helmets, either for the whole face or just the eyes. The masks did not long survive the 7th century in Anglo-Saxon England, but the Gjermundbu helmet may suggest it lasted in Scandinavia through to the 10th century. Merovingian helmets of the 6th-8th century tend to be more conical and keep the cheek flaps, but do not have any mask36. Carolingian helmets of the 9th century appear to have been a unique style, more rounded but also coming down further towards the cheeks, and it’s hard to say if this eventually developed in the conical helmet of the late 10th/early 11th century or if it was just a dead end37. Regardless, by the 11th century the conical helmet was the most common form of helmet in England as well as the Continent.

And now for the controversial stuff: non-metallic armour. In short, I don’t think that textile armour was very common during the Early Middle Ages, nor do I think that hardened leather was very common either. The evidence from the High Middle Ages suggests that, unless someone who couldn’t afford to own mail was legally required to own textile armour, they generally didn’t, and we have plenty of quite reliable depictions of infantry serving without any form of body armour38. The shields in use were as much armour as most unarmoured men needed - since, as you’ll recall from the previous section, they rarely fought - and they covered a lot of the body. So far as I’m concerned, there wasn’t a need for it, and plenty of societies through history have fought in close combat without more armour than their shield.

Summing Up

This has been a very basic overview of the background to warfare in the Early Middle Ages, and I know I haven’t covered everything. Hopefully, however, I’ve provided enough background for people to follow along when I dig down into the actual experience of battle in my next post. I’ll cover the basics of scouting, choosing a site to give battle, the religious side of things and then, at long last, the grim face of battle for those standing in the shieldwall.

If you’d like to read more about society and warfare in the Early Middle Ages, then I’d recommend Guy Halsall’s Warfare and Society in the Barbarian Westand Philip Line's The Vikings and their Enemies: Warfare in Northern Europe, 750-1100, which together cover most of Western and Northern Europe from 400 AD to 1100 AD. While I have some disagreements with both authors, their works have shaped my thoughts over the years since I first acquired them. For the Vikings specifically, Kim Hjardar and Vegard Vike's Vikings at War is excellent, as much for the coverage of campaigns across the world as for the information on weapons and warfare.

Until next time!

- Hergrim

Notes

1 For the rarity of the sax in the viking world, see Vikings at War, by Kim Hjardar and Vegard Vike. For the Anglo-Saxon sax, see the list of finds here. Just 5 out of 33 (15%) had blades 44cm or more and, if you remove those longer than the Pompeii style of gladius (which is the point where some think the Romans changed to purely thrusting style), just two fit the bill.

2 Michael J. Taylor’s “Visual Evidence for Roman Infantry Tactics” is by far the best recent examination of Roman fighting styles, but Polybius has been translated in English for ages. See, however, M.C. Bishop, The Gladius, for an argument that the Romans changed to close order and preferred to rely on thrusting by the end of the 1st century AD.

3 See J. C. Coulston and M.C. Bishop, Roman Military Equipment: From the Punic Wars to the Fall of Rome, for the infantry adoption of the gladius. Any general history of the Roman military will cover the transition from open order to close order during the 3rd century AD.

4 Those of you with a copy of Victor Davis Hanson's The Western Way of War need to perform a quick exorcism. You must burn the book at midnight during the full moon and then divide the ashes into four separate containers, one of gold, one of silver, one of bronze and one of iron. You should then bury ashes from the iron container at a crossroads, scatter the ashes in the bronze container to the wind in four directions, pour the ashes from the silver container into a fast flowing river, and finally feed the ashes from the gold container to a cat, a bat and a rat.

5 A.D. Fraser “The Myth of the Phalanx-Scrimmage” is one of the earliest attacks on the idea of literal othismos. The debate reignited in the 1980s, with Peter Krentz’s “The Nature of Hoplite Battle” leading the charge of the heretics, and the conceptual othismos model is now the accepted version. Hans van Wees’ Greek Warfare: Myths and Realities is probably the best revisionist work to start with. Matthew A. Sears, as attractive as he looks, should be avoided.

6 Early Anglo-Saxon Shields by Tania Dickinson and Heinrich Harke

7 Duncan B. Campbell’s Spartan Warrior 735–331 BC has the most easily accessible information on the best preserved aspis, which is ~10mm thick at the center and 12-18mm thick at the edge, but there’s also a good cross section in Nicholas Sekunda’s Greek Hoplite 480-323 BC. For Viking shields, see this page of archaeological examples by Peter Beatson. Note the similarity to oval shields from Dura Europos in thickness and tapering (Roman Shields by Hilary and John Travis). It’s also worth considering that Carolingian and Anglo-Saxon manuscript miniatures tend to show shields that rarely cover more than should to groin, implying a typical diameter of 50-70cm.

8 See Niels Lund’s “The armies of Swein Forkbeard and Cnut: "leding or lið?”” and Ben Raffield’s “Bands of brothers: a re‐appraisal of the Viking Great Army and its implications for the Scandinavian colonization of England” for an examination of how the lið was constructed, and see Richard Abels’ ‘Alfred the Great, the Micel Hæðn Here and the Viking Threat’, in T. Reuter (ed.), Alfred the Great. Papers from the Eleventh-Centenary Conference for a discussion on the nature of viking “armies”

9 10-15 acres depending on crop rotation and how close to subsistence level you want to peg this category

10 The Scandinavian Gulathing and Frostathing laws were only composed in the late 11th/early 12th century, but it has been argued that they were essentially a codification of earlier oral laws. At least with regards to equipment and service, I see no reason to doubt this.

11 Almost all of the relevant capitularies are translated in Hans Delbruck’s History of the Art of War: The Middle Ages, with the original Latin in an appendix.

12 Walter Goffart has made this incredibly clear in his recent series of loosely related articles: “Frankish Military Duty and the Fate of Roman Taxation,” Early Medieval Europe, 16/2 (2008), 166-90, “ The Recruitment of Freemen into the Carolingian Army, or, How Far May One Argue from Silence?” In J. France, K. DeVries, & C. Rogers (Eds.), Journal of Medieval Military History: Volume XVI (pp. 17-34) and ““Defensio patriae” as a Carolingian Military Obligation”. Although I think Goffart argues too strongly against the dominance and importance of aristocratic retinues in the Carolingian military - the great landowners had the most obligation, after all - he does do a brilliant job of highlighting both the universal requirement of service from eligible freemen and the fact that even a “poor” freeman being assessed for service was, in fact, far better off than most of society. This provides some extra context for the prevalence of swords in Merovingian burials, as note by Guy Halsall: it’s not that swords were cheap, it’s that the average Merovingian warrior was rich by the standards of his society.

13 For the text of the capitulary, see Delbruck. For Aistulf’s possible political motives, see Guy Halsall’s Warfare and Society in the Barbarian West. For Anglo-Norman minimum standards for unarmoured cavalry, see Mark Hagger’s Norman Rule in Normandy, 911–1144.

14 I think it’s worth addressing here the pessimistic low crop yields of older authors and their subsequent conclusion that 25-30 acres would be bare subsistence in the Early Middle Ages. As Jonathan Jarrett has proven (”Outgrowing the Dark Ages: agrarian productivity in Carolingian Europe re-evaluated” Agricultural History Review, Volume 67, Number 1, June 2019, pp. 1-28), these low yields are not supported by the evidence, and we should expect yields to be similar to High Medieval yields. His blog contains an early version of his thoughts on the matter.

15 For a recent exploration of the debate around the Anglo-Saxon military, see Ryan Lavelle’s Alfred’s Wars

16 See Richard Abel’s Alfred the Great for this although n.b. his reliance on old crop yield estimates

17 John Bannerman, Studies in the History of Dalriada. The suggestion that the Cenél nGabráin, being the most powerful clan, might have raised fewer men from the general populace for land combat is my own. They may simply have had the largest number of men in military households and, as such, not needed to rely as much on the general populace when on land. It may also be that calling up larger numbers of the free population for land service from the less powerful clans was in and of itself a method of dominance and control - the largest number of armed men left behind for defence/to suppress revolt would be those from the dominant clan.

18 “Boathouses and naval organization” by Bjørn Myhre in Military Aspects of Scandinavian Society in a European Perspective, AD 1-1300

19 That said, the political control of the Scandinavian kings over military levies should not be overstated - it could be very patchy, even in the 13th century. c.f. Philip Line, The Vikings and their Enemies

20 As suggested by Ole Crumlin-Pedersen in Archaeology and the Sea in Scandinavia and Britain, with the estimate of ~40 oars for the Sutton Hoo ship thrown in as a maximum size. Crew estimates are based on 11th century ships in Anglo-Saxon employ where, based on rates of pay and money raised to pay for the ships, there were only 3-4 men more than the rowers on each ship.

21 c.f. Egil’s Saga and the description of Arinbjorn’s preparation for raiding.

22 The Medieval Demographic System of the Nordic Countries by Ole Jørgen Benedictow. The speculation of larger family sizes is my own, based on other medieval evidence that wealthier families tend to have more children.

23 Ian Heath reproduces the leidang obligations of High Medieval Norway in Armies of the Dark Ages, although he incorrectly applies the two men per oar guideline that only became into being during the 13th and 14th centuries. Archaeological evidence only shows ships of 60+ oars or 26 oars, but from the lengthening of the largest ships and the 40-50 oar ships of the later leidang I feel it is appropriate to assume that the number of oars stayed the same from the 10th to the 14th century, it’s just that the number of rowers doubled as ships became heavier. This is similar to the evolution of the medieval galley.

24 I’ve covered saxes earlier in the notes. For axes, see Hjardar and Vike Vikings at War. Axeheads from western Scandinavia were often over a pound in weight, which is double the weight of specialized Slavic war axes and in the same weight range as the heads of broad axes. Even into the 13th century, these wood axes apparently kept turning up at weapons musters as sidearms.

25 Bows were considered an important aristocratic weapon in Merovingian, Carolingian and Scandinavian societies and, while not a prominent aristocratic weapon, it at least wasn’t shameful for a young English nobleman to use one in battle. The division between “hunting” and “war” bows can be seen in the Nydam Bog finds, where the most powerful bows tend to be relatively short (26-28″ draw length) and the longer bows (28-30″ draw length) tend to be fairly weak. Richard Wadge has demonstrated that civilian bows in medieval England were less powerful than military bows during the 13th century, and I’m applying this to the Nydam bows.

26 Ancient Weapons in Britain, by Logan Thompson

27 See “An Early Medieval Winged/Lugged Spearhead from the Dugo Selo Vicinity in the Light of New Knowledge about this Type of Pole-Mounted Weapon” by Željko Demo, and “An Early-Mediaeval winged spearhead from Fruška Gora” by Aleksandar Sajdl

28 Ancient Weapons in Britain, by Logan Thompson

29 The Celtic Sword, by Radomir Pleiner

30 Most dimensions are from Jürgen Junkmanns’ Pfeil und Bogen: Von der Altsteinzeit bis zum Mittelalter, although the information on the Illerup Adal comes to me from Stuart Gorman. Draw weights are only estimates based on replicas of some bows and a formula found in Adam Karpowicz’s “Ottoman bows – an assessment of draw weight, performance and tactical use” Antiquity, 81(313). Draw weights for yew bows in the real world can vary by as much as 40%, so these estimates are only general guidelines.

31 See f.n. 6 for early Anglo-Saxon shields and Halsall, Warfare and Society, for the early Merovingian shields

32 The shields from Dura Europos, constructed in the same way as Scandinavian shields of the 8th-10th century, feature either very thin leather (described as “parchment”), linen or else some kind of fiber set in a glue matrix. In contrast, two twelfth century kite shields from Pola. d, although constructed only with a single layer of planks like a Viking shield, had no covering at all. See Simon James, The arms and armour from Dura-Europos, Syria : weaponry recovered from the Roman garrison town and the Sassanid siegeworks during the excavations, 1922-37 and “Two Twelfth-Century Kite Shields from Szczecin, Poland” by Keith Dowen, Lech Marek, Sławomir Słowiński, Anna Uciechowska-Gawron & Elżbieta Myśkow, Arms & Armour, 16:2

33 Round Shields and Body Techniques: Experimental Archaeology with a Viking Age Round Shield Reconstruction

34 Halsall, Warfare and Society

35 Thomas Vlasaty has a great article that summarises this subject.

36 No real source for this beyond googling pictures of the various Anglo-Saxon, Scandinavian and Merovingian helmets.

37 This Facebook post has some wonderful pictures of the original helmet, a reconstruction of the helmet and comparisons with Carolingian art.

38 eg. the Porta Romana frieze, the porch lunette at the basilica of San Zeno in Verona, the Bury Bible.

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

good omens / good place