#Taichi Yamada

Text

真夜中の匂い 山田太一

大和書房

写真=篠山紀信、装幀=高麗隆彦

436 notes

·

View notes

Text

The subtle transitions in their eyes as they depart. 😥

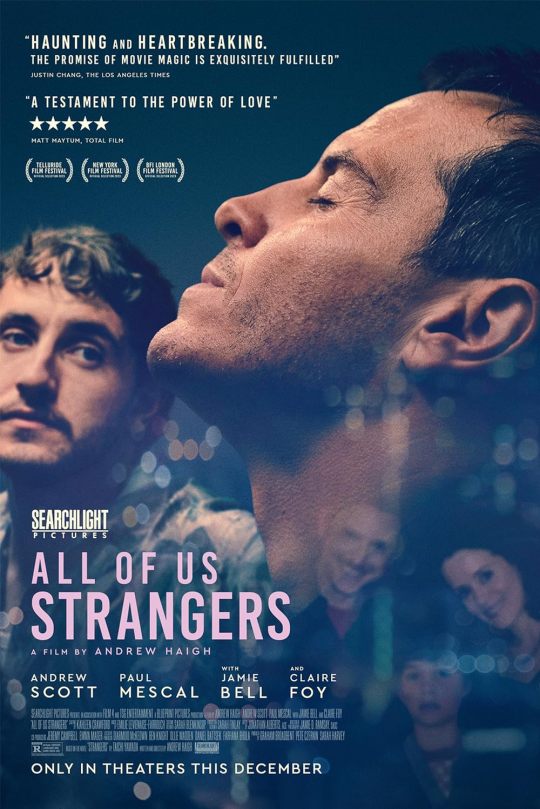

ALL OF US STRANGERS (2023)

#All of Us Strangers#Andrew Scott#Claire Foy#Jamie Bell#Andrew Haigh#Strangers#Ijintachi To No Natsu#Taichi Yamada#異人たちとの夏#山田 太一#Quotes

96 notes

·

View notes

Text

I watched All of Us Strangers on Tuesday night.

It took me a while to truly digest it - to sit with it and process.

This film made me feel like my heart was in my throat, and I left the cinema with puffy, red eyes.

Andrew Scott is a stellar actor. He uses every single part of himself in every single scene. I’ve never seen anyone convey so much, so silently.

This is the first time I had seen Paul Mescal in anything, and he was truly beautiful. I can’t wait to see what he does next.

Overall, the film was incredible. But expect to be distraught.

#all of us strangers#andrew scott#paul mescal#claire foy#jamie bell#strangers#taichi yamada#andrew haigh#jamie d. ramsay

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

'On a recent winter day in New York when the sun was shining, Andrew Scott rushed into a coffee shop between recording sessions for an upcoming series.

“I’m scheduled tighter than a teenage pop star,” he said, beaming.

The interview had been postponed once, and the location was switched at the last minute to save Scott some time in traffic. But he sat down fully engaged and eager to start talking. Immediately, though, a passerby tapped on the storefront glass and asked for a photo. Scott, without a grumble, sprinted out to oblige, even though the gesture seemed more like a command (“You’re under arrest,” joked Scott) than a polite request.

Scott, the 47-year-old Irish actor, is in demand like never before. That’s partly due to accrued good will. A regular presence on stage in the West End, Scott is known to many as the “Hot Priest” of “Fleabag” or the cunning Moriarty of “Sherlock.” Soon, he’ll play Tom Ripley in the Netflix series “Ripley,” adapted from the Patricia Highsmith novel.

But the real reason Scott’s time is short right now is Andrew Haigh’s new film, “All of Us Strangers.” In it, Scott plays a screenwriter working on a script about his childhood. The film is gently poised in a metaphysical realm; when Adam (Scott) returns to his childhood home, he finds his parents (Claire Foy, Jamie Bell) as they were before they died many years earlier.

At the same time, the movie, loosely adapted from Taichi Yamada’s 1987 book “Strangers,” balances a budding romance with a neighbor ( Paul Mescal ), a relationship that unfolds with profound reverberations of family, intimacy and queer life. In a dreamy, longing ghost story, Scott is its aching, shimmering soul.

“The challenge of it was to try to go to that place but not gild the lily too much,” Scott says. “As an actor, I have to be in touch with that playful side of myself and that part of you that’s childish. I was actually quite struck by how vulnerable I looked in the film.”

Scott’s acutely tender performance has made him a contender for the Academy Awards. He was named best actor by the National Society of Film Critics. At the Golden Globes on Sunday (Scott wore a white tux and t-shirt), he was nominated for best actor in a drama.

Scott has long admired actors like Anthony Hopkins, Judi Dench and Meryl Streep — performers with a sense of humor who, he says, “are able to understand what you feel and what you present.” Scott, too, is often funny on screen (see Lena Dunham’s medieval romp “Catherine Called Birdy” ). And even in quiet moments, he seems to be buzzing inside at some discreet frequency. Something is always going on under the surface.

He’s been acting since he was young; drama classes were initially a way to get over shyness. Scott’s first film role came at age 17. He has often spoken about seeking to maintain a childlike perspective in acting. In that way, “All of Us Strangers” is particularly fitting. On Adam’s trips home, he sort of morphs back into the child he was. In one scene, he wears his old pajamas and crawls into bed with his parents.

“So many of the things that are required of you as an actor are a sense of humor and some ability to be able to put yourself in a situation. Because it’s all down to imagination,” says Scott. “For me, that’s the thing you need to keep. That’s the thing — because I started out when I was young — I don’t want to move too far away from. Like when kids go, ‘OK, you be this and I’ll be this.’ That ability doesn’t leave us. What does leave us is a lack of self-consciousness. Our job is to hold on to that.”

Haigh, the British filmmaker of “45 Years” and “Weekend,” began thinking of Scott for the role early on. They met and talked through the script for a few hours.

“He’s a similar generation to me. He’s a tiny bit younger than me, but he’s from the same generation,” says Haigh. “He understands that experience.”

Scott came out publicly in 2013, but his natural inclination is to be private. “I feel like I’ve given so much of myself in the film, you think you don’t want to give it all away,” he says. He describes “All of Us Strangers” — which Haigh shot partly in his childhood home — as personal, but not autobiographical in its depiction of the alienation that can linger after coming out.

“Mercifully, I feel very comfortable for the most part. But it stays with you that pain, and it actually makes you more compassionate, I think. Because we shot in Andrew’s childhood home, that sort of threw down the gauntlet in relation to how much of his own personality he was giving,” says Scott. “I wanted it to be sort of unadorned, unarmored and raw. That’s why I think there’s such tenderness in the film.”

Scott has sometimes recoiled from how sexuality is talked about the media and in Hollywood. He recently said the phrase “openly gay” should be done away with. As of late December, Scott hadn’t yet watched “All of Us Strangers” with his parents, though he planned to.

“The best way to express it is to say I’ll be very sensitive to how they watch it and how they feel about it, and how it makes me feel them watching it,” Scott says.

The tenderness in the film is also owed in part to Scott’s chemistry with Mescal. On-screen chemistry is an amorphous quality that the film industry has long tried to turn into a science with camera tests and marketing that flirts with real-life romance.

But for Scott, it’s something different. He and Phoebe Waller-Bridge had chemistry, overwhelmingly, in “Fleabag,” but that didn’t have anything to do with sexual attraction. Pinpointing that quality is something Scott pondered during Simon Stephens and Sam Yates’ recent staging of Chekhov’s “Uncle Vanya” at the National Theater. Scott played all eight roles, meaning he essentially had to have chemistry with himself.

“Chemistry isn’t just about sexual chemistry. It’s something to do with listening, and I think it’s something to do with playfulness,” Scott says. “Your ability to listen to someone and take note of what someone is doing is chemistry. You have to wait and see what the other actor is doing.”

A few moments later, Scott will have to rush out just as quickly as he arrived. But before that, he leaned back, naturally lit by the winter sun, and pondered whether “All of Us Strangers,” in the nakedness of his performance, had taken him somewhere he hadn’t before been as an actor.

“Yeah, I think so,” said Scott. “Or else to return to something that perhaps I’ve been before.”'

#Andrew Scott#Paul Mescal#Andrew Haigh#All of Us Strangers#Phoebe Waller-Bridge#Fleabag#Ripley#Netflix#Moriarty#Sherlock#Taichi Yamada#Strangers#Patricia Highsmith#Jamie Bell#Claire Foy#Lena Dunham#Catherine Called Birdy#45 Years#Weekend#Simon Stephens#Sam Yates#Vanya#National Theatre

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

whos gonna be a babe and share the link to andrews scott latest masterpiece 'all of us strangers'?

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

I am still so moved by "All Of Us Strangers" Andrew Garfield did an incredible job in talking to Director Andrew Haigh, Claire Foy and with its lead Andrew Scott, who was so lovely when I shook his hand as I was in bits crying. Yes, this film triggers, but in a way that is healing. Andrew Haigh was so lovely and comforted me when I told him what had triggered me about his work. The film is pure genius. It's spiritual without being corny. It reflects its viewer, who bring their memories to the piece. The film has only four actors who carry the movie for 105 minutes. It's based on a Japanese novel by the late Taichi Yamada called Strangers, but other than its core, it bonds with anyone who grew up in the UK in the 80's. If this film does not move you, then you are already dead!

— Jon Thompson

from Twitter

#opinion#all of us strangers#andrew garfield#andrew haigh#claire foy#andrew scott#screening#moderating#jon thompson#from twitter#taichi yamada#japanese novel

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'll protect you from the hooded claw,

Keep the vampires from your door

#all of us strangers#andrew scott#paul mescal#andrew haigh#this film had so much heart and now mine is broken#heartbreak#taichi yamada#strangers to lovers#film#film edit#film stills#cinematography#cinema#intimacy#i am so devastated#atmospheric#grief#loss#i will now cry everytime i hear the power of love#the power of love#claire foy#jamie bell

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

#all of us strangers#andrew haigh#hideo kojima#taichi yamada#this is the british film of the year for me

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

All of Us Strangers

Movies watched in 2024

All of Us Strangers (2023, UK)

Director & Writer: Andrew Haigh (based on the novel by Taichi Yamada)

Mini-review:

Wow. I'm almost speechless right now. There are very, very few stories that have awoken these specific emotions inside of me. Everything about this script resonated with me to the bone. I don't know, I feel like I found a kindred spirit in the main character, even though our experiences are quite different. One of the reasons why this movie works so f**king well is the performances by its four stars. This is seriously some of the finest acting I've ever seen, and I'm not kidding. On top of that, Andrew Haigh's directing gives the film a haunting, dreamy vibe that makes the whole thing all the more special. It's safe to say All of Us Strangers has carved its own spot in my heart, and I won't stop thinking about it for a long time.

#all of us strangers#strangers#andrew haigh#taichi yamada#andrew scott#paul mescal#jamie bell#claire foy#drama#fantasy#magical realism#queer art#queer cinema#gay cinema#gay movies#lgbt#lgbtq#lgbtqia#lgbtq cinema#lgbtq movies#movies watched in 2024

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

想い出づくり 山田太一

大和書房

装画=大橋歩、装幀=高麗隆彦

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tell me everything.

ALL OF US STRANGERS (2023)

[+] LGBTQ 🏳️🌈

[+] ..more on “All of Us Strangers” 🎬

#All of Us Strangers#Claire Foy#Andrew Scott#Andrew Haigh#Strangers#Ijintachi To No Natsu#Taichi Yamada#異人たちとの夏#山田 太一#Quotes

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Bycie normalnym polega na tym, że w dorosłym życiu potrafimy zapanować nad słabościami wyniesionymi z dzieciństwa.”

~ Taichi Yamada:"Obcy"

#taichi yamada#przemyślenia#życie#prawda#piękno#cytat o milosci#koniec#cytat o uczuciach#sztuka#cytat o ludziach

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Acá la versión en laptop y creo que empezare a a ser las cabezas de otro estilo o no se pero les gusta?

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

'From the first shot of Andrew Haigh’s unconventional ghost story All of Us Strangers, we are introduced to the world of the uncanny. Sunlight streams through the windows of a glass building, molten and syrupy against Andrew Scott’s skin. There’s something surreal and insubstantial about his reflection in the window. Then, we see the building itself, a new high-rise in Stratford, inhabited by only two men: Adam and Harry.

Adam (Scott) is a screenwriter who lives alone, subsisting on Chinese takeaways. He seems lost in his own world as he tries to write about his parents who died in a car accident when he was a child. When he decides to jog his memory by returning to his childhood home, he returns to find his parents apparently alive – but exactly as they were 30 years ago (by now, Adam is older than them). Loosely based on the novel Strangers by Taichi Yamada, Haigh re-appropriates the ghost story with a naturalistic bend, which allows Adam to re-engage with his grief and its entanglement with his queer identity.

The film also delves into Adam’s burgeoning love with his young, enigmatic neighbour, Harry (Paul Mescal). “It was such a joy, playing Harry, playing someone different to any role I’ve had. He’s a little bit frightening – and drunk, sexy and forward,” Mescal tells Dazed. The film unpicks the unsettled state of modern queerness – of feeling estranged by a heteronormative society even during a time when queerness is supposedly celebrated. Haigh takes this mutable sense of temporality and creates a sense of suspended, circular time as the film vacillates between two timelines, one focused on the past with his parents and another in the future with Harry.

At its core, All of Us Strangers is an exploration of queer love and intimacy across time. As Haigh says: “Love is the centre of Adam’s story. With both his parents and with Harry, love is about feeling seen.” Below, we speak to Paul Mescal, Andrew Scott, Andrew Haigh about the film.

In the film, the use of mementos, from photographs to music, are really evocative. Why did you want to invoke the past through these symbols?

Andrew Haigh: We shot the film in my own childhood home and I wanted to feel like I was putting myself into it. It’s my most personal film. I wanted to return to there because it’s the space I imagined while writing the script. I hadn’t been there for 45 years, yet I could remember so viscerally the smell of the house, the feel. The soundtrack is composed of songs I loved as a kid. I’ve always loved The Pet Shop Boys. It was a kind of therapy – of staging my memories to work through them. Memories exist like time travel in our mind constantly, it all feels as real.

The whole film is about feeling. We want you to feel the emotion of it, the texture, the sensuality of it, in a phenomenological way. Music just draws you back to the past in such a visceral way. The records have such an analogue texture to it, of real things and textures. That’s why we shot it on film, to keep that sense of materiality.

Andrew, what drew you to Adam’s character and the story?

Andrew Scott: It was the central idea of returning to the past. I find the character to be someone I really recognised and a character who goes on such a strong journey. He’s in every scene except two shots. What’s so interesting is that the film’s ghostly concept seems like such an audacious idea, but what’s so wonderful is that people walking outside in Soho right now are having conversations with people in their head who are not alive. Our imagination is so alive, and time is not a linear logic. To bring that memory to life is not as absurd as you might think.

Paul, what drew you to Harry’s character and the film? Aftersun and All of Us Strangers both tackle the ghosts of the past, memory and grief. What draws you to this complex subject and different ways of embodying it?

Paul Mescal: I think Harry is a beautiful character. He has an immense capacity to love somebody even though he’s dealing with extraordinary pain. We don’t really see a huge amount of it in the film, but there are instances where he talks about his incredibly difficult relationship with his family.

I think I am more interested in the past than I am in the future in general. I think the past is what informs our behaviour. There’s something about the past that feels unattainable. But what’s amazing about this film – its magic – is that it allows you to interrogate the past and to revisit conversations. That’s what’s so tragic about the past: once it’s gone, it’s locked there.

For every film, I usually create a playlist tailored to the character, to try and understand them. For Harry, I was listening a lot to ‘Adios, Florida’ by A Winged Victory For the Sullen.

Can you tell us a bit about the cinematography choices? The film features a lot of superimpositions and reflections in windows and mirrors. The first time we see Harry and Adam, they are both seen through the glassy reflection of a window or mirror.

Andrew Haigh: I knew that the film, even while naturalistic, couldn’t feel entirely real. It had to feel like it was hovering somewhere in a liminal space. In the opening shot, you almost ask, ‘Is it a reflection? Is it you?’ We aren’t quite sure what we are seeing.

I’m obsessed with reflections. On a philosophical basis, as a queer person, you spend a lot of the time reflecting and performing something which actually isn’t you. Especially when you’re in the closet. You spend the whole time reflecting an image to the world. That can be very disconcerting for you on a psychological basis. Reflection is the perfect way to express that. In this film, the reflection is often even different from who you are. It changes through the film when we play with those reflections and I find that really interesting. Towards the last scene, they get closer, and expose their real selves. I returned to some Francis Bacon paintings as references just to articulate what felt right aesthetically.

What was it like working with Andrew Haigh in his own home? Did you bring any of your personal mementos to set?

Andrew Scott: It was so generous of Andrew to let us film in his home. It throws down the gauntlet in terms of authenticity. I just felt I had to bring my own biography even if it’s not my own geography. One of the great pleasures was to speak to Andrew about how we grew up and the pain that we’ve been through – the 80s and 90s was a difficult time to be queer. We’ve come so far in relation to our experience in the world and I felt so seen by the script and by Andrew’s other films in the past. I brought my own sense of truth and my own experience.

I wore this golden chain that I’m wearing now too, and it catches the light in the film in a lovely way.

It’s remarkable the way you manage to transform into a child again in the house through your body language and this vulnerability we see in your face.

Andrew Scott: When Adam says, ‘It doesn’t take much to make you feel the way you felt back there,’ I think it resonates. You know, I live a very happy life now and I’m comfortable with who I am, but there was a time when that wasn’t the case. The pain of that time, as much as you try and suppress it, it’s very potent. To be able to do that again, that feeling is not as far away as I might have imagined. It was also a catharsis to do it again.

The coming-out conversations with Adam’s family are particularly poignant, capturing the sense of the atemporality of modern queerness. What was the process of writing them?

Andrew Haigh: It was quite painful to write those coming-out sequences. It wasn’t just coming out to his mother, which has its own complications, pain and terror. But it’s a reminder of how he used to feel back then. So, all of those things that the mother said, all those things that happened to him at school that the dad mentioned, those were things that happened to Adam – look, they happened to me, to a lot of gay kids back then. It’s a reminder of how I used to feel. The film is about the pain we try to keep hidden away, the grief and the trauma of being gay at that time. For Adam, it’s about that coming to the surface again, remembering how he used to feel. For me as a director and writer, and for Andrew as an actor, it brought all of those feelings back again. I got eczema again, which I haven’t had since I was a kid. My body literally reacted to how I used to feel when I was younger.

Harry is often a protector to Adam – taking care of him when he’s ill, taking him home from the club. Yet, we see brief moments of his immense pain throughout the film. Paul, how did you represent this pain bubbling under the surface?

Paul Mescal: That’s the tragedy of the film. Harry is laughing at his own pain a lot of the time. Because that’s how humans are. It’s so difficult to talk about ourselves so directly – when we try to talk about things that cause us pain, I think we generally try and laugh through because it deflects from the rawness because if you really go into those feelings, sometimes you can’t really get out of it. And I think Harry’s a master chameleon. I wanted to play Harry as somebody who’s trying to hide his pain the whole way up until the ending. I wanted him to not show his pain, and I think I failed in the moment when I said, ‘I know what it’s like to stop caring about yourself’, because I was looking at Andrew and he was upsetting me so much.

The pain reveals this idea that, despite Harry being more forward and more sexually liberated, he still feels this pain and this shame because of his family. Essentially, if families aren’t caring and thoughtful, they can breed shame, which is ultimately quite damaging and you see the damage that it does to Adam. Adam has the privilege of being able to revisit those conversations with his parents. Harry doesn’t get that opportunity with his own and they’re still living, so I think it’s a wonderful illustration of how shame is bred in society, particularly in a home environment.

The love story features two different generations of queer men. How did you decide to represent their difference but also their shared sense of dislocation?

Andrew Haigh: There is a big difference between the different generations of queer people. They’ve grown up without the shadow of AIDS. We didn’t know how our lives would progress into the future then. Whereas, there’s now gay marriage and so much progression. Yet, to be queer in the world now still means you’re different and that’s still difficult. Some young people who seem great from the outside are still dealing with their trauma of being at school. Yes, it’s better, but it doesn’t mean it’s easy. I think we can often fight against the generation that came before, but it’s important that we see ourselves in this lineage together.

Paul, how did you approach building this tender sense of intimacy and chemistry with Andrew?

Paul Mescal: I loved Andrew as an actor before we knew each other properly. And when I started to know him more, we just really liked each other. I find that it’s actually easier to play sex scenes than it is to play the tenderness after sex. Because you’re both inhabiting a physical language – that distinct feeling of lying on a bed and talking to somebody you love after having sex. The tenderness required in your quality of touch is something you can’t really block and write. It’s not like you’re going to touch his hand like this at this particular moment. It just doesn’t work like that. So I think we do have this innate thing called chemistry, which I find impossible to describe.

The way you guys look at each other in the film is so sexy. I couldn’t look away.

Paul Mescal: That’s the bit that scared me. When I saw it for the first time in the audience, I asked Andrew if he remembered me doing that. The most illicit moment is not actually the sex, but my eyes looking up to Andrew when I’m about to go down on him.

How do we tackle queer loneliness for future generations?

Andrew Scott: I think the problem of queer loneliness comes from a basic thing: that people assume everybody unless told otherwise is straight. Everyone from a benign aunt to a taxi driver asks if you have a boyfriend if you’re a girl, and a girlfriend if you’re a boy. That’s the assumption. That’s why I love the embracing of the word ‘queer’ – as some people exist within a scale, defying this binary of choice. It’s very difficult to define – do we write down and laminate all our sexual fantasies to define us?

The way we talk about sexuality has to ultimately change. It’s the accidental cruelty of the benign aunt or the parent. That’s what makes people feel lonely. And, it’s not something you can defend as a child, because you don’t know or can’t fully articulate it yet. It’s this quiet and subtle feeling of loneliness that permeates these lives. I remember Geri Halliwell years and years ago with this little camp boy on TV, a Spice Girls fan – and the TV presenter asks ‘are you going to have a girlfriend when you grow up?’ and Geri Halliwell adds in, ‘or boyfriend’. That’s a wonderful thing, it’s a tiny thing but it offers the option. The reframing of how we talk to our youth.

All of Us Strangers is available in UK cinemas from January 26.'

#Andrew Scott#Andrew Haigh#Paul Mescal#All of Us Strangers#Strangers#Taichi Yamada#A Winged Victory For the Sullen#Adios Florida#Aftersun#Francis Bacon

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

little doodle that was originally meant for White Day (but I only got around to give it some colours now due to the cold knocking me out)

But it’s alright, this could…also probably happen on any other day ngl shdhfhg

2 notes

·

View notes