#St Apollinaire

Text

Les potes de la Francophonie vous avez le droit de répondre aussi, je vous fais la bise (chez moi c'est une)

76 notes

·

View notes

Note

First of all sending some ibuprofen and a lot of melatonin for your aches and lack of sleep! Hopefully you'll get better soon ♡

For the book thing! Can I ask you 4, 14, 20 and 23 pleaaase? -☆

thank you 🥺 from your lips to god's ears my friend !

i answered 4 already, but luckily you gave me some other options.

14. What books do you want to finish before the year is over?

gonna read some poems by Apollinaire!! also want to read The Glass Hotel by Emily St. John Mandel before christmas because i found it in a little free library in my neighborhood and thought my sister might like it, but i can't be sure just from the blurb. and i am GOING to start The Name of the Rose, i SWEAR, i MEAN IT!!! but i don't know if i'll be able to finish it before the year ends.

20. What was your most anticipated release? Did it meet your expectations?

probably System Collapse by Martha Wells and yeah i loved it <3

i was also really looking forward to Sam Irby's latest essay collection, Quietly Hostile, which did not disappoint. laughed a lot in an airport, which is one of the best things a book can make one do, in my opinion.

and Translation State by Ann Leckie was fucking bonkers good but i can't actually remember now what my expectations were for it...pretty sure it was highly anticipated though because i remember refreshing my library holds queue 10 times a day for like a month after it came out lol.

23. What’s the fastest time it took you to read a book?

hmm, i'm not sure, i don't exactly track this! i can tell you the longest time it took me to read a book though (if we're not counting the french dictionary i've been reading since early april and haven't finished yet, it would be Les Misérables, which took almost three months).

i read Quietly Hostile in one day while traveling. i often read novellas in one day if not one sitting, which was likely the case for Into the Riverlands by Nghi Vo, Burning Roses by S. L. Huang (which i read during the whole carbon monoxide debacle, so i don't really remember much about it) (not because CO was affecting my memory but because waiting in the freezing cold for the gas company to show up and then waiting for four hours in urgent care is not exactly conducive to reading lol), Untethered Sky by Fonda Lee, and each of the Murderbot novellas. i read some manga for the first time ever this year and usually read about a volume a day (i did read the first volume of the french translation of Ranma 1/2 in one day because i couldn't put it down!!).

mostly i paced myself pretty deliberately this year because so much of my reading time was taken up with my daily french reading projects. so to sit down and read something in english that would take longer than 2 hours was not really feasible if i also wanted to spend 1-2 hours reading in french. i did get a lot faster at reading in french though!

book asks!!

#asks#not anon#books#*sigh* i can always count on you coming through in the clutch with asks for me#omg ETA i had to replace cmc with les mis as the book that took me the longest to read#because i forgot cmc was in 2022!!!

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Apollinaire Theatre Company’s ‘Touching the Void’ Reaches for the Moon

Cast of Apollinaire Theatre Company’s ‘Touching the Void’

‘Touching the Void’ — Based on the book by Joe Simpson. Adapted by David Greig. Directed by Danielle Fauteux Jacques. Scenic and Sound Design by Joseph Lark-Riley; Lighting Design by Danielle Fauteux Jacques; Movement Choreography by Audrey Johnson. Presented by Apollinaire Theatre Company at Chelsea Theatre Works, 189 Winnisimmet St.,…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Marie Laurencin was a French artist known for her delicate depictions of young women in idyllic landscapes. Using muted pinks, dove grays, and mint greens the artist created dreamlike visions of reality. “Why should I paint dead fish, onions and beer glasses? Girls are so much prettier,” she once said.

Born on October 31, 1883 in Paris, France, Laurencin like Pierre-Auguste Renoir studied porcelain painting in her youth. She attended drawing classes at the Académie Humbert before having her first solo exhibition in 1907. After falling into the circles of Pablo Picasso she became the lover of the famed poet Guillaume Apollinaire. Her close contact with the Cubists and Section d’Or artists such as Robert Delaunay and Jean Metzinger led her to develop her hallmark style of simplified volumes and arabesque lines. During her life she was a sought after portrait painter of notable Parisian celebrities including Coco Chanel.

Laurencin died on June 8, 1956 in Paris, France. In 1983, commemorating the 100th anniversary of her birthday, the Musée Marie Laurencin opened in Nagano, Japan. Today, the artist’s works are held in the collections of the Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris, The Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Tate Gallery in London, and the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg.

Biography copied from https://www.artnet.com/artists/marie-laurencin/, check out to see more of her amazing art

#Such an icon tbh#The ''why draw vases when girls are so much prettier'' part hits hard#Art#Woman artist#French artist#And I'm making some assumptions here but#Wlw artist#Bisexual artist

1 note

·

View note

Text

Birthdays 8.26

Beer Birthdays

Pete Slosberg (1950)

Peter V.K. Reid (1963)

Bobbi Sue Luther; St. Pauli Girl 2007 (1978)

Five Favorite Birthdays

Barbara Ehrenreich; writer (1941)

Shirley Manson; rock singer (1966)

Chris Pine; actor (1980)

Leon Redbone; Canadian-American singer-songwriter, and guitarist (1949)

Will Shortz; crossword & puzzle maker (1952)

Famous Birthdays

Prince Albert; English royalty (1819)

Guillaume Apollinaire; French writer (1880)

Jet Black; English drummer (1938)

Tori Black; porn actor (1988)

Ben Bradlee; journalist (1921)

John Buchan; Scottish writer (1875)

Cleopatra; Egyptian queen (69 B.C.E.)

Julio Cortazar; Argentine writer (1914)

Christopher Columbus; Italian explorer (1451)

Macaulay Culkin; actor (1980)

Chris Curtis; English drummer and singer (1941)

Eleanor Dark; Australian author and poet (1901)

Lee DeForest; inventor (1873)

Geraldine Ferraro; politician, U.S. vice-presidential candidate (1935)

James Franck; German physicist (1882)

Zona Gale; writer (1874)

Peggy Guggenheim; art patron (1898)

Christopher Isherwood; English writer (1904)

Johann Heinrich Lambert; Swiss mathematician, physicist & astronomer (1728)

Antoine Laurent Lavoisier; French chemist (1743)

Branford Marsalis; jazz saxophonist (1960)

Caroline Pafford Miller; author (1903)

Joseph-Michel Montgolfier; hot air ballon co-inventor (1740)

John Mulaney; comedian (1982)

Alan Parker; English guitarist and songwriter (1944)

Jules Romains; French author and poet (1885)

Jimmy Rushing; singer and bandleader (1901)

Albert Sabin; microbiologist (1906)

Mother Teresa; catholic missionary (1910)

Maureen Tucker; singer-songwriter and drummer (1944)

Nik Turner; English musician and songwriter (1940)

Robert Vickrey; painter (1926)

Robert Walpole; English politician (1676)

Edward Witten; physicist (1951)

Adrian Young; drummer and songwriter (1969)

0 notes

Text

The maternal grandmother of two Quebec girls killed by their father in July 2020 told a public inquiry Tuesday that shortly before their deaths, the father was overwhelmed by divorce proceedings and obsessed with the idea he would lose custody of them.

Gaétane Tremblay told the inquest that she thought Martin Carpentier's obsession was like "a phobia you don't understand; Martin had no reason to be afraid of losing his Tremblay told the inquiry investigating the murders of 11-year-old Norah and 6-year-old Romy that he killed them in the woods near St-Apollinaire, Que., southwest of Quebec City, before killing himself.

The girls went missing with their father after a car crash on July 8, 2020. The search for them turned into a multi-day police manhunt that gripped the province. Police found the girls' bodies in the woods on July 11. And since the case started, questions have arisen about the quality of the police investigation.

Tremblay said Carpentier lived directly next door to her and often confided in her. His health worsened in 2020, she said, particularly after he began working nights. Carpentier seemed agitated and nervous on July 6, two days before the disappearance, she told the inquiry.

Tremblay said an agitated Carpentier told her he did not want to go through with his plan to divorce Amélie Lemieux, the girls' mother, from whom he had separated in 2015; Carpentier was also anxious about the possibility he would have to move from his home next door to Tremblay.

The inquiry heard Monday that Carpentier had looked into divorce proceedings but had not informed Lemieux said that work colleagues had suggested to him that a divorce could lead to losing custody and that Carpentier's new spouse wanted to marry before they bought a house.

Earlier in her testimony, Tremblay recounted another incident where Carpentier told her in May 2020 that he didn't like seeing his kids being cared for by Lemieux's boyfriend.

"He wasn't Norah's biological father but had adopted her in 2010 and didn't like anyone else taking care of his children," Tremblay said, adding that even when the girls weren't in his care, Carpentier would tell his girlfriend, "In case Amélie calls, I will be available."

Tremblay, who first met Carpentier around 2008, said the family took to him right away and could see that he loved our daughter, so they loved him even more.

She described Carpentier as an "exemplary father" who was always there for his daughters and remained close, saying that on the day the girls vanished, Carpentier told her he was going out for ice cream but never returned and that she can still see them every time she looks out a large window at her home.

"He told me, 'Gaétane, I'm going to bring the children back at 9 p.m., but I'd like to go there alone with my daughters," she recounted, "but he never came back."

0 notes

Text

De chevy monza 98 manuel mode d'emploi >>Download (Telecharger)

vk.cc/c7jKeU

De chevy monza 98 manuel mode d'emploi >> Lire en ligne

bit.do/fSmfG

Name: De chevy monza 98 manuel mode d'emploi.pdf

Author: Uosukainen Whitehead

Pages: 325

Languages: EN, FR, DE, IT, ES, PT, NL and others

File size: 7682 Kb

Upload Date: 21-10-2022

Last checked: 12 Minutes ago

17 déc. 2021 MODE D'EMPLOI. Avant d'effectuer le test sur votre système de refroidissement, testez d'abord la pompe en pompant plusieurs fois pour vous d'utilisation, panne, problème de fabrication. MODE D'EMPLOI La présente notice ne remplace en aucun cas le manuel d'entretien. Les meilleures offres pour 1963 Corvair Et Monza Usine Assemblage Manuel Explosé Vues Chevy Chevrolet sont sur eBay ✓ Comparez les prix et les spécificités Avis 4,8 Avis de anonymous Cnwagner Gm52088015 Auto Voiture Hydraulique Manuel Camion Rapide De K20, SSR, Monte Carlo, Lumina, Spark, Chevy Monza, Astra, Spin, tornado, V10, finition Monza (standardisée sur le cabriolet) et nible décourage d'avance toute utilisation de mode n'a pas duré, la seconde génération. Découvrez toutes les voitures de collection neuves et usagées à vendre à St-Apollinaire sur LesPac.com. Avis 5,0 (15 310) MWM moteur diesel D226 : notice d'entretien - instructions de services 1978 Chevrolet Monza Propriétaires Manuel Exploitation Sécurité Entretien Teinté. Chevrolet Malibu Maxx SS Chevrolet Meriva Chevrolet Monte Carlo Chevrolet Monza Chevrolet Nova Chevrolet One-Fifty Series Chevrolet P30 VAN Manuel Camion Chevrolet série N 1932 notice technique manuel entretien RARE Owner ´S Mode D 'em Ploi / Manuel Chevrolet Spécial + Deluxe Support 1951.

De chevy monza 98 brugervejledning

De chevy monza 98 mode d'emploi

De chevy monza 98 brugervejledning

De chevy monza 98 kezikonyv

De chevy monza 98 bedienungsanleitung

De chevy monza 98 user manual

De chevy monza 98 handbuch

De chevy monza 98 handleiding

De chevy monza 98 handbook

De chevy monza 98 prirucka

https://www.tumblr.com/cugekokerej/698825274446544896/oxford-ophthalmology-manuel-mode-demploi, https://www.tumblr.com/cugekokerej/698825100590546944/siemens-heating-control-notice-mode-demploi, https://www.tumblr.com/cugekokerej/698825274446544896/oxford-ophthalmology-manuel-mode-demploi, https://www.tumblr.com/cugekokerej/698825100590546944/siemens-heating-control-notice-mode-demploi, https://www.tumblr.com/cugekokerej/698825100590546944/siemens-heating-control-notice-mode-demploi.

0 notes

Text

Marche Yoga Nature Lieu : chapelle de St Apollinaire 69590

Marche Yoga Nature Lieu : chapelle de St Apollinaire 69590

#Castelneuviens

#ChateauneufLoire42800

#ChateauDuMollard

le Samedi 1er octobre à 10 H

Si vous désirez vous reconnecter à la nature par une marche dans les monts du Lyonnais.Des exercices de yoga et de méditation vous seront proposés pour se reconnecter à soi.Vivre une expérience ensemble.

(more…)

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Text

death creates life

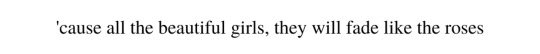

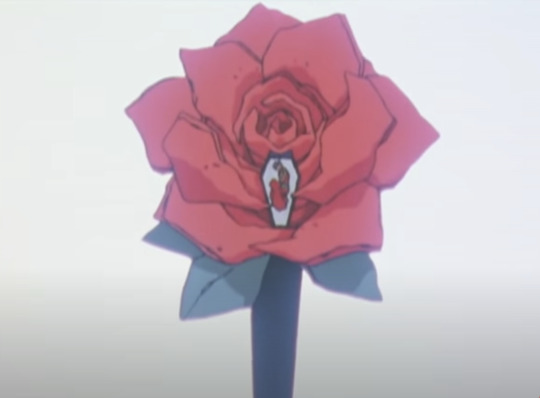

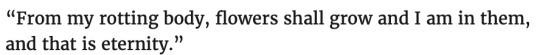

"Rhenish Autumn" Guillaume Apollinaire // Nature and Decay Sculpture - Amanda Reid // "Stoned at the Nail Salon" Lorde // Revolutionary Girl Utena (1997) // Edvard Munch // The Garden of Death - Hugo Simberg // "Dirge Without Music" Edna St. Vincent Millay // Dead Leaves - Alexandre Jacques Chantron // "Worms" Viagra Boys

#words#life#nature#death#web weaving#lyrics#parallel#anthy himemiya#anime#movie#art#flowers#z#garden#im praying for the fucking formatting oh my god this took too long#poetry

57 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Melbourne, May 10: The world-premiere Melbourne Winter Masterpieces exhibition, The Picasso Century, charts the extraordinary career of Pablo Picasso in dialogue with the many artists, poets and intellectuals with whom he intercepted and interacted throughout the 20th century, including Guillaume Apollinaire, Georges Braque, Salvador Dalí, Alberto Giacometti, Françoise Gilot, Valentine Hugo, Marie Laurencin, Dora Maar, André Masson, Henri Matisse, Dorothea Tanning and Gertrude Stein. Exclusively developed for the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV) by the Centre Pompidou and the Musée national Picasso-Paris, the exhibition features over 70 works by Picasso alongside over 100 works by more than 60 of his contemporaries, drawn from French national collections, as well as the NGV Collection. The Picasso Century will be on display from June 10 at NGV International, St Kilda Road, Melbourne. Exhibition organised by the Centre Pompidou, Paris, the Musée national Picasso-Paris, and the National Gallery of Victoria. For tickets and information, log on to www.visitmelbourne.com. #ngv #melbourne #exhibition #australia (at Melbourne, Victoria, Australia) https://www.instagram.com/p/CdZ2XeTrOh6/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Le Pont Amérique

✽

Under the America Bridge the train runs,

And our love runs away.

I remember,

We were swaying on the connection bogies,

Talking about our escape journey to the distant country.

The night is a clock chiming.

The days go by not I.*

A pantograph making a silhouette in the sunset.

After the lunar eclipse and the full tide,

The last train will carry you away.

Before the sunrise,

Wearing a hemp shirt,

I will think of you in a dress with cut work lace,

Blowing in the wind at a platform of the Ebisu Station.

The tracks surround a breath of the town.

The steam rising from the warm kitchen.

The laughter of children frolicking in the back alleys.

A piano playing at the Moderato that causes boredom.

A reading light that chases the story through the curtain.

The night is a clock chiming.

The days go by not I.

Under the America Bridge,

Everyday life continues to flow.

We are eternal travelers.

✽

© images: hiromi suzuki, 2021

…

References: Le Pont Mirabeau by Guillaume Apollinaire, *Quoted from Mirabeau Bridge Translated by Donald Revell via Poetry Foundation. Ebisu Minamibashi known as the America Bridge is a footbridge located between Meguro Station and Ebisu Station on the Yamanote Line in Shibuya Ward, Tokyo. It was originally exhibited at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair, US. The nickname comes from the fact that it was purchased by the Japanese National Railways (at that time) and erected at the present location in 1906 as a model for iron bridges.

Note: Le Pont Amérique is a part of the first poetry collection Ms. cried – 77 poems by hiromi suzuki (kisaragi publishing, 2013 ISBN978-4-901850-42-1). The poem written in Japanese have been translated by hiromi suzuki, 2021.

✽ ✽ ✽

Le Pont Amérique / Hiromi Suzuki

© poetry by hiromi suzuki, 2021

published in RIC Journal (December 31, 2021)

…

via RIC Journal

#hiromi suzuki#poetry#poem#prose#prose poetry#collage#photo-collage#photography#Ms. cried#poetry magazine#poetry journal#literary journal#RIC Journal

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

— ONLY SAINTS ; nanowrimo 2020

Old Mère taught me how to quilt when I was just old enough to thread a needle. She loved using her weathered hands to create, at the sewing machine or the pottery wheel or the rich black soil garden in front of her trailer. She sat me down on warm summer afternoons while my mother went to town and showed me different stitches, different styles, different seeds, and she taught me the art of magic-making.

The thing about magic-making is that it works in patterns. One word is not a spell, not on its own. Two words, repeated, with force—that is a different matter.

GENRE || new adult low fantasy

POV || first/present

STATUS || planning

GOAL || 20k-25k

THEMES || grief ; identity ; finding one ‘self’ among many possibilities ; managing unrealistic expectations ; learning the limits of the human heart

EXTRA || aroace autistic protag ; unhealthy family dynamics ; echolalia ; patterns found in everything

“You must be deliberate,” she lectured me when, more than once, my stitches turned out rushed and sloppy in my eagerness to please.

APOLLINAIRE is the grandson of the oldest witch in the South. He’s the first boy born in her line for three hundred years, and she guards him jealously, teaching him all the magic she knows before anyone else can corrupt him. Between his bloodline and his talent, there’s a lot riding on his shoulders, all before he’s twelve years old.

And then his father sues for custody in the divorce.

My father pushed me to go premed when I was sixteen. If I didn’t, he told me, I’d be a disappointment. Every man on his side of the family has a name followed by M.D., or Ph.D., or J.D., like their names are gilded with all the money they spent on college.

PAUL ST. ROSE is an emergency medic. At 21, it’s not the end of his career path—or his schooling—but it’s a good place to land and catch his breath. He’s always done well in high-stress environments, managing to keep his cool even when the world is falling apart around him.

But when his grandmother dies, he’s pulled back into the life he used to lead: back into Old Mère’s rickety trailer with the black soil garden out front; back into the social rough-and-tumble of his mother’s side of the family, rife with petty backstabbing; back into who he used to be.

Between the cold success of Paul and the honeysuckle-sweet occultism of Apollinaire, he crumbles under the weight of everything that he was supposed to be by now. He’s always done well in high-stress environments. But what can he do when he’s the one falling to pieces?

Only saints are saints.

[[ — yes, i’m planning on doing nano this year — yes, it’s probably a bad idea — no, i probably won’t be posting much more content for this until it’s done — but yes, i wanted to show off my cover and my excerpts — i won’t be running a taglist for only saints, but if you’re interested, check out my tags #wip: only saints and #oc: apollinaire — thank you — ]]

#my writing#wip: only saints#nanowrimo#nano 2020#my nano#my covers#cover art#watch me not touch this at all until november#it's gonna be fun#this is going to be a novella#not a full novel#mainly bc it's going to function#mostly as a character study for paul#who is officially the most 'self-insert' character#that i have in any of my active wips#oops

89 notes

·

View notes

Text

reading list - lyrical poetry

CLICK HERE TO ACCESS MY OTHER READING LISTS.

✵ ACTIVELY UPDATING ✵

☐ APOLLINAIRE, Guillaume – Alcools

☐ BAUDELAIRE, Charles – Les Fleurs du Mal

☐ BROOKE, Rupert – "The Soldier"

☐ CALLIMACHUS – Epigrams

☐ du BELLAY, Joachim – Les Regrets

☐ ÉLUARD, Paul – Capitale de la douleur

☐ GARCÍA LORCA, Federico – Romancero gitano

☐ GURNEY, Ivor – "Photographs"

☐ HORACE – Epistles

☐ HORACE – Odes

☐ JUVENAL – Satires

☐ KOMUNYAKAA, Yusef – "Camouflaging the Chimera"

☐ McCRAE, John – "In Flanders Fields"

☐ RILKE, Rainer Maria – Die Sonette an Orpheus

☐ OVID – Ars Amatoria

☐ OWEN, Wilfred – "Dulce et Decorum Est"

☐ PERSE, Saint-John – Amers

☐ PINDAR – The Olympian Odes

☐ PRÉVERT, Jacques – Paroles

☐ ROSSETTI, Christina – "A Dirge"

☐ SEEGER, Alan – "Rendezvous with Death"

☐ STATIUS, Publius Papinius – Silvae

☐ UNATTRIBUTED – Orphic Hymns

☐ WHITMAN, Walt – Drum-Taps

☐ WHITMAN, Walt – Leaves of Grass

POETS

BAUDELAIRE, Charles

BUKOWSKI, Charles

BYRON, Lord

CUMMINGS, E. E.

DeE ANGELIS, Milo

DICKINSON, Emily

ELIOT, T. S.

FROST, Robert

GINSBERG, Allen

HARDY, Thomas

HUGHES, Langston

HUGO, Victor

KEATS, John

MILLAY, Edna St. Vincent

MIŁOSZ, Czesław

MUSSET, Alfred de

NERUDA, Pablo

PAZ, Octavio

PLATH, Sylvia

POE, Edgar Allan

SAPPHO

SEXTON, Anne

SHAKESPEARE, William

SHELLEY, Percy Bysshe

VERLAINE, Paul

WHITMAN, Walt

WORDSWORTH, William

YEATS, W. B.

李白 (Li Bai)

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Birthdays 8.26

Beer Birthdays

Pete Slosberg (1950)

Peter V.K. Reid (1963)

Bobbi Sue Luther; St. Pauli Girl 2007 (1978)

Five Favorite Birthdays

Barbara Ehrenreich; writer (1941)

Shirley Manson; rock singer (1966)

Chris Pine; actor (1980)

Leon Redbone; Canadian-American singer-songwriter, and guitarist (1949)

Will Shortz; crossword & puzzle maker (1952)

Famous Birthdays

Prince Albert; English royalty (1819)

Guillaume Apollinaire; French writer (1880)

Jet Black; English drummer (1938)

Tori Black; porn actor (1988)

Ben Bradlee; journalist (1921)

John Buchan; Scottish writer (1875)

Cleopatra; Egyptian queen (69 B.C.E.)

Julio Cortazar; Argentine writer (1914)

Christopher Columbus; Italian explorer (1451)

Macaulay Culkin; actor (1980)

Chris Curtis; English drummer and singer (1941)

Eleanor Dark; Australian author and poet (1901)

Lee DeForest; inventor (1873)

Geraldine Ferraro; politician, U.S. vice-presidential candidate (1935)

James Franck; German physicist (1882)

Zona Gale; writer (1874)

Peggy Guggenheim; art patron (1898)

Christopher Isherwood; English writer (1904)

Johann Heinrich Lambert; Swiss mathematician, physicist & astronomer (1728)

Antoine Laurent Lavoisier; French chemist (1743)

Branford Marsalis; jazz saxophonist (1960)

Caroline Pafford Miller; author (1903)

Joseph-Michel Montgolfier; hot air ballon co-inventor (1740)

John Mulaney; comedian (1982)

Alan Parker; English guitarist and songwriter (1944)

Jules Romains; French author and poet (1885)

Jimmy Rushing; singer and bandleader (1901)

Albert Sabin; microbiologist (1906)

Mother Teresa; catholic missionary (1910)

Maureen Tucker; singer-songwriter and drummer (1944)

Nik Turner; English musician and songwriter (1940)

Robert Vickrey; painter (1926)

Robert Walpole; English politician (1676)

Edward Witten; physicist (1951)

Adrian Young; drummer and songwriter (1969)

0 notes

Photo

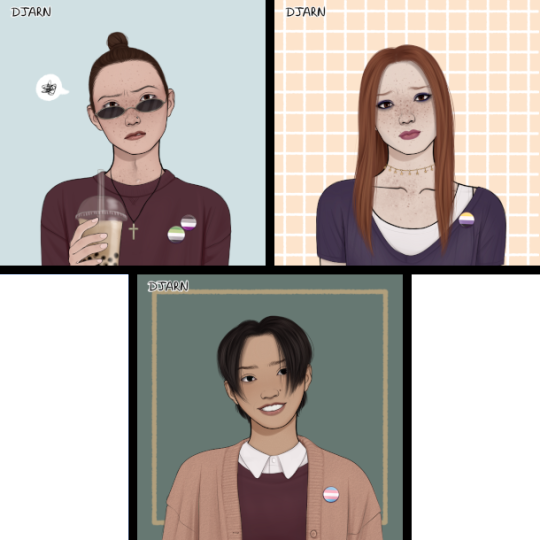

ONLY SAINTS – the main trio: apollinaire chastain st. rose and florette v chastain (top row), andrew mayer (bottom)

// aka i fucked around (on picrew) and found out (what my characters look like) but this is from like a couple weeks ago i just. really love these characters they’re my life ok

#picrews#verv makes too many picrews#way too many#but i love them#look at them#they're perfect#my absolute disaster children#'v' is not florie's middle initial btw#it's a 5#they're florette chastain the 5th#and that's only the ones their family is certain about

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

MATISSE AND RUSSIAN ICONS: The Metaphysics of Pictorial Space

"He paints 'images'" and in these "images endeavors to reproduce the divine. To attain this end he requires as a staffing point nothing but the object to be painted (human being or whatever it may be) and then the methods that belong to painting alone, color and form." ---- Wassily Kandinsky, writing about Henri Matisse [1]

Matisse’s Introduction to Russian Icons

There is a remarkable convergence between the work of Henri Matisse and that of the Russian icon painters. Our topic in this essay is precisely this convergence, and not the influence which icons may have had on Matisse. In the case of an artist of Matisse's caliber, influences -- although present and not without interest -- are superficial compared to that which gives quality to the art; because at a deeper level, every great artist is original, in the sense that the art draws its strength from direct contact with nature - and in Matisse's case, with nature at her deepest level, where one drinks from the very wellspring of being, of existence. That is why Matisse said that to be an artist one must rid oneself of prejudicial habits of vision and learn to look at life with the eyes of a child, and draw one's strength from the existence of objects. [2]

Matisse was already moving in a certain direction before he went to Russia, and the icons he saw there made a strong impression on him because he was ready to see them, because he was travelling on a path that converged with them. As Matisse himself put it, "You surrender yourself that much better when you see your efforts confirmed by such an ancient tradition. It helps you jump over the ditch."[3] It is not wrong to say that the icons influenced Matisse; but it is truer, and more to the point, to say that they confirmed his originality.

A certain kinship can be noted between ancient icons and Matisse's paintings even before the artist visited Russia. The Painter's Family was finished just before Matisse left for Moscow in October, 1911; yet the brilliant reds and black-and white checkerboard patterning are already reminiscent of icons. Matisse had very likely seen icons in 1906 in the exhibition organized by Sergei Diaghilev as part of the Salon d'Automne, and was probably familiar with more examples of iconography through reproductions. Interest in icons was "in the air" at that time. The 1911 Salon des Independants included works by several contemporary Russian artists working in a neo-Byzantine or archaic style; Guillame Apollinaire said they seemed to have "fooled the centuries."[4] Painters and patrons of contemporary art in Russia at this time, like Riabushinskii and Oustrukhov, collected icons.

The Conversation was another picture painted before the trip to Moscow. Shchukin, writing to Matisse on August 22, 1912, said of this picture: "I often think of your blue painting (with two figures)... It reminds me of a Byzantine enamel, its colors are so rich and deep."[5] Matisse's first exposure to Byzantine art may have come through Signac. When the divisionist travelled to Venice and saw the Byzantine mosaics in San Marco, he decided to change his dots to squares. He brought back a number of postcards which he doubtless showed his disciple in St. Tropez. The impression of Byzantine mosaics seems to have stayed with Matisse. After his death, several photographs of the interior of Hagia Sophia were found pinned to the wall of his apartment in Nice.

Matisse arrived in Moscow on October 23, 1911. The next day, he visited Ilya Ostroukhov, painter and collector and "patron" of the Tretiakov Gallery, whom he had met in Paris, and asked to be shown his collection of Russian Icons. A day later Oustroukhov recounted the incident:

"Yesterday evening he visited us. And you should have seen his delight at the icons. Literally the whole evening he wouldn't leave them alone, relishing and delighting in each one. And with what finesse! ... At length he declared that for the icons alone it would have been worth his while coming from a city even further away than Paris, that the icons were now nobler for him than Fra Beato... Today Shchukin phoned me to say that Matisse literally could not sleep the whole night because of the acuity of his impression."[6]

"From that moment on, "writes Pierre Schneider, "Matisse spent all his time going around to visit churches, convents, and collections of sacred images, his excitement at the first encounter not having diminished one iota. He shared it with all who came to interview him during his stay in Moscow." [7]

On Oct. 31, Ilya Ostroukhov wrote to D.J. Tolstoy, the curator of the Hermitage Museum: "Matisse is here. He is deeply affected by the art of the icons. He seems overwhelmed and is spending his days with me frantically visiting monasteries, churches and private collections." [8]

"They are really great art," Matisse excitedly told an interviewer. "I am in love with their moving simplicity which, to me, is closer and dearer than Fra Angelico. In these icons the soul of the artist who painted them opens out like a mystical flower. And from them we ought to learn how to understand art." [9] What is one to make of this expression of heartfelt admiration for the old Russian icons? From these icons "we ought to learn how to understand art." This is a very strong statement. It sounds exaggerated. Yet, Matisse was habitually reserved and cautious in his statements, not prone to exaggeration. Our endeavor in these pages may be defined as an investigation of the meaning and validity of this assertion.

"From them we ought to learn how to understand art." Not one particular kind of art, but art in itself. The icons offered Matisse a revelation of what art is. This goes deeper than stylistic "influence." To speak of Matisse imitating or being influenced by icons is to miss the point. His relationship with them is on a deeper level. In them he has recognized, in an especially pure form, the essence of art. Art is, for Matisse, essentially a manifestation of the life in which both nature and the artist participate. Throughout his career Matisse was a truly original artist. This does not mean that one cannot find in his work what are commonly called "influences" of other artists, in this case the Russian iconographers. It means that Matisse's art is directly rooted in the place where art originates, in the wellspring of being which we mentioned at the beginning. Precisely because he strives to be true to nature, Matisse converges with the icon painters.

We know that before and after his trip to Moscow, Matisse responded enthusiastically to other forms of what were known as "primitive arts" – Persian miniatures, Japanese prints and African sculptures. But the icons held a special importance for two reasons.

The first was articulated by Matisse in several interviews in Moscow. On Oct. 27, he praised the monumentality and majesty of the Kremlin churches, and the reporter added: "The pure, rich colors of the old icons, their sincerity and immediacy, seemed a genuine discovery to him." Then he quotes Matisse: "This is primitive art. This is authentic popular art. Here is the primary source of all artistic endeavor. The modern artist should derive his inspiration from these primitives." [10] Matisse confided to another interviewer: "The icons are a supremely interesting example of primitive painting. Such a wealth of pure color, such spontaneity of expression I have never seen anywhere else. This is Moscow's finest heritage. People should come here to study, for one should seek inspiration from the primitives. An understanding of color, simplicity -- it's all in the primitives. It is the best thing Moscow has to offer. One should come here to learn because one should seek inspiration from the primitives."[11]

Matisse links the "primitive" quality of the icons with their authentic popularity. That is to say, this art was still in use and understood popularly. It worked. In Matisse's view, art is not to isolate itself in museums, but to "participate in our life."[12] Decades later, in a letter to Sister Jacques-Marie regarding the Chapelle du Rosaire at Vence, Matisse wrote: "I would like it to be useful. Do you think it could be useful?"[13] What does Matisse mean when he speaks of art "working" or being "useful"? This question brings us to one of the key connections between Matisse and the iconographers. In his conception and theirs, the role of art is therapeutic. It seeks to "relieve," to "alleviate," to "heal." How it does this we will see a little further on, but for now let us just say that the instrument of this "healing" is light."[14] "Light," says Schopenhauer, "is the most delightful of all things; it is the symbol of everything that is good, everything that heals. In all the religions of the world it symbolizes eternal salvation."[15] (Let us remember that, etymologically and theologically, salvation means healing.) The icons held a special importance for Matisse because they are an art whose specific function is to heal whoever contemplates them, by means of light; and this use is truly popular, understood by all the faithful who approach them. Presently we shall look into the nature of pictorial light, color and space, and then we shall see what this light has to do with healing.

Before we get to that, however, we can surmise a second reason for the special importance which the icons held for Matisse. Whereas Persian miniatures and Japanese prints were foreign to the West, icons were part of the heritage of western Europe until the late middle ages, in Romanesque and early Gothic painting and sculpture. The whole of western medieval art developed in direct or indirect dependency on Byzantium, and there was a rich exchange of formal ideas between East and West throughout the Middle Ages. Furthermore, the art of the great Venetians -- Titian, Veronese and Tintoretto -- has roots in Byzantine iconographic art, the influence coming by way of Crete. The Venetian legacy, with its Byzantine formal roots, was in turn widespread in western Europe, coming to Matisse via Chardin, Courbet and Cezanne. Thus while the icons were, like other eastern painting, impressively and revealingly different from "the art of the museums," they were nevertheless a significant part of the family tree of western art. This peculiar balance must have been especially stirring to the sensibilities of the young painter who had spent so much time studying western masterworks in the Louvre.

Space in Russian Icons and in Matisse: preliminary considerations

It is often said that icons and Matisse's late paintings and cutouts, and for that matter Japanese prints and Persian miniatures as well, are "flat." Such a statement can be either ambiguous or mistaken, depending on the understanding and intention of the speaker.

The intended meaning of the word "flat" may simply be "unmodelled." Indeed, the modelling or shading of volumes in these works is usually slight, and is sometimes suppressed altogether. They are executed largely in line and flat tone. But that does not at all diminish the plenitude of the volumes! Volume is expressed in better ways. As Matisse explained to a visitor in his studio, who remarked on the volumetric quality of the Barnes Mural, "Yes, but in reality the painting is made in flat tones, without any gradation ... It is the drawing, and the harmony and contrast of the colors, that form the volume, just as in music a number of notes form a harmony more or less rich and profound according to the talent of the musician who has assembled them."[16] So let us not say that these pictures are flat, even if we only mean to refer to the flatness of the tones; the paintings are emphatically not flat.

Sometimes Matisse's pictures and the icons are said to be "flat" because they lack Albertian perspective -- as if space were dependent upon such perspective. This, too, is an error, as will be made clear by our investigation of the nature of pictorial space. This investigation will begin in the following paragraphs, and will be taken up again and deepened later in this essay.

Our experience of space in the world is largely kinesthetic, dependent upon the sensation of our bodies' movement, our feeling of the forces of gravity and equilibrium, and the ever-varying correlation between optical stimuli and eye movements -- including binocular convergence, accommodation to focal distance and parallax.[17] This elementary fact is forgotten by those who think that space is achieved in painting by optical verisimilitude, with its shading of volumes and its atmospheric and linear perspective approaching the effect of photography. An arbitrary "snapshot," the epitome of a purely optical impression, gives us a jumble of variously shaped tones removed from their spatial context. From being accustomed to viewing such flat images, whether in photographs or in academic "realist" paintings, we develop a "space blindness." The eye seizes upon recognizable details and, by a conventional sort of "leap of credulity" accepts the flat image as referring to things one has experienced in the world. The difference between flatness and space collapses.

The opposite happens in great paintings. There our experience of space is heightened. In a masterpiece of Matisse -- or of Rembrandt or Raphael, Giotto or Picasso or Mondrian, for example -- a feeling of depth is created by the pushing and pulling of shapes and colors. All the lines and tones are organized, at once musically and architectonically, in such a way as to give the viewer movement into and out of depth; and this depth is made palpable by the tension between it and the flatness of the pictorial surface. The real experience of space in a painting is not quantitative, dependent upon the suggestion of deep vistas; rather, it is qualitative, dependent upon the resonance of the tension between the flat plane and all the pushing and pulling planes of color. The difference between flatness and space is not collapsed in painting; it is amplified.

Two Views of Matter

The belief, so rampant in the academic art of the nineteenth century and still widespread today, that a painter can "copy" appearances -- as also the trust we put in the camera, a machine, to reproduce the way things look - betrays a tendency to reduce the material world to mere materiality, something which can be considered apart from spirit. When the churches of the West split from the Christians of the East at the end of the first millennium, they set off on a road of increasing rationalism, gradually losing the mystical vision of the world which the Orthodox in the East retained. Descartes' dualistic philosophy is a significant milestone in the western trend, although the direction was evident centuries earlier, notably in the medieval scholastics. Descartes held that matter is mere extension and that spirit is only found in our own minds or in heaven. To the extent that painting was influenced by this notion, it had to deal with the world, its light and its space, externally, mechanistically. To be sure, there was never any lack of allegory, or poetic or religious subject matter; but things were ontologically impoverished, rendered inert.

The Orthodox tradition knows no separation between nature and grace such as prevails in western thought in the wake of scholasticism. In the eastern view, as expressed from ancient times by Gregory of Nyssa, Maximus the Confessor and a host of others, matter is thoroughly and dynamically irradiated by the divine energies, apart from which matter would not exist. These energies are uncreated; they are God Himself. By the "luminous force"[18] of His logoi or "thought-wills" God creates and orders, sustains and governs all things in an intimate, dynamic relationship with each creature, operating within the creature. This inner life of nature blazes forth as what Saint Isaac of Syria calls "the flame of things." St. Maximus says: "The unspeakable and prodigious fire hidden in the essence of things, as in the bush, is the fire of divine love and the dazzling brilliance of His beauty inside every thing."[19] Icons are above all concerned with this inner life, this luminous force, this fire within creation.

Matisse similarly insists on the necessity for artists to be in touch with the inner lift of things. "The time spent at school should be replaced by a free stay in the Zoological Gardens. The pupils would gain knowledge there in constant observation of embryonic life and its vibrations. They would gradually acquire that ‘fluid’ which great artists come to possess." Matisse, like the icon painters, recognizes the need for a certain asceticism, a purification of the power of vision, in order that one may see the light and life within nature. Raymond Escholier describes how, relaxing in his garden in Nice, Matisse smiled at the crystal-clear light: "Everything is new," he said, "everything is fresh, as if the world had just been born. A flower, a leaf, a pebble, they all shine, they all glisten, lustrous, varnished, you can't imagine how beautiful it is! I sometimes think we desecrate life; from seeing things so much, we don't look at them any more. Our senses are wooly. We feel nothing. We are spoiled. I think that to really enjoy things, it would be wise to deprive ourselves of them. It is good to begin by renouncing, force oneself from time to time to take a cure of abstention."

The artistic process

Matisse describes the work of a painter as an inner process, culminating in the rhythmic and life-filled expression of an internal vision:

The first step toward creation is to see everything as it really is [dans sa verite], and that demands a constant effort...

A work of art is the climax of long work of preparation. The artist takes from his surroundings everything that can nourish his internal vision... He enriches himself internally with all the forms he has mastered and which he will one day set to a new rhythm.

It is in the expression of this rhythm that the artist's work becomes really creative. To achieve it, he will have to sift rather than accumulate details, selecting for example, from all possible combinations, the line that expresses most and gives life to the drawing; he will have to seek the equivalent terms by which the facts of nature are transposed into art....

That is the sense, so it seems to me, in which art may be said to imitate nature, namely, by the life that the creative worker infuses into the work of art. The work will then appear as fertile and as possessed of the same power to thrill, the same resplendent beauty as we find in works of nature.

Great love is needed to achieve this effect, a love capable of inspiring and sustaining that patient striving towards truth, that glowing warmth and that analytic profundity [depouillement profond] that accompany the birth of any work of art. But is not love the origin of all creation? [20]

This love, which is necessary for artistic creation, has a divine aspect:

Nothing is more gentle than love, nothing stronger, nothing higher, nothing larger, nothing more pleasant, nothing more complete, nothing better in heaven or on earth -- because love is born of God and cannot rest other than in God, above all living beings.[21]

The rhythmic quality of lines, tones and shapes, which Matisse insists on, is necessary for experiencing the vital energy at the heart of existence. The rhythms are perceived in nature by the artist who has purified his vision so as to be able to "look at life as he did when he was a child."[22] The artist must interiorize these rhythms, "until the object of his drawing has become like a part of his being, until he has it within him and can project it onto the canvas as his own creation."[23] In this sense the object is set forth in the work of art according to a new rhythm. There is a life that fills all creation, a life which is the manifestation of a great love. An artist can make a beautiful work of art, a work which manifests the splendor, the love-impelled vitality of nature, only to the extent that he reverently attends to reality "with the eyes of a child."

Matisse's approach is similar to that of the icon painters. They likewise expose themselves at length to that which they want to portray, until they can draw its traits not from the outside world but from deep within themselves. The Orthodox tradition holds that one can only see the uncreated light of divinity by being oneself transformed into light. Hence the iconographers must be ascetics, must purify their vision and become themselves filled with light. Then they will see all things as filled with light; they will walk in a divine space, the space of the kingdom of heaven which is within them. The space and the light are one; and all things are light, as an iron held in fire becomes fire. The icon painter expresses all this from within, expresses a space which is identical with light-energy and which does not recede from us, but rather opens out toward us. The saints who inhabit this space are, in the words of St. Macarius of Egypt, "all face and all light."

Let us look at an icon of Saint Nicholas. One of the most pronounced elements in the design is the relation among the crosses on the saint's omophorion [part of the outer liturgical vestment of a bishop]. They move counterclockwise around his shoulders. The symmetrical placement of light and dark shapes immediately to the right and left sides, respectively, of the saint's neck, ensures the movement of space around his head and the return of this movement on the left side, where the cross moves downward and toward the right to complete the spatial circle. The opposition between the downward and rightward movement of the left cross and the upward and rightward movement of the right cross is mediated by the strict parallelism of their constitutive parts, while the abrupt change in direction from the former to the latter is explained (and caused) by the abrupt collision of the omophorion with the forcefully rectangular shape of dark robe at the center of the icon. The vector of the left cross ricochets off the upper edge of this dark rectangle to become the vector of the right cross. The exceedingly great power of this dark rectangular shape, which is able to stand firm beneath these crosses (themselves strong and violent in their contrasts) is felt to issue forth from the blessing hand which extends into this shape, and thus to be an amplification, a visual proclamation, of the power emanating from the peaceful gesture. Thus the icon shows us simultaneously both the gentleness and the power of the blessing. At the same time, the Gospel book bounds forward from the dark rectangle, repeating its shape while being pushed forward by the visual action of the white omophorion. The color of the book relates it directly to the blessing hand, as well as to the head. The book pulls gently to the right, assisting the overall counterclockwise rotation of the space in the icon. This movement of space (and concomitantly of volume, since neither exists apart from the other in painting) is seen also in the subtle asymmetry of the head (characteristic of icons) -- in the placement of its features and the modeling of its volumes. It is hardly necessary to point out that all the lines and shapes in this icon, all the highlights in the dark robe and even the subtlest nuances of the modeling in the hand and face, as well as all the chromatic and tonal intervals, are rhythmically and harmonically interrelated.

In a testimonial of 1951, Matisse tells of how, in the Chapel at Vence, he wanted to do the same thing he had always done in his canvases: "In a very restricted space- the width is five meters --I wanted to inscribe a spiritual space as I had done so far in paintings of fifty centimeters or one meter; that is, a space whose dimensions are not limited even by the existence of the objects represented."[24]

This spiritual space is a kind of plenitude that is plastic, i.e. truly felt. It does not imitate some externally perceived space. And it is achieved through color -- color which, laid on in flat planes, provokes light "as one uses harmonies in music."[25] "Color helps to express light, not the physical phenomenon, but the only light that really exists, that in the artist's brain."[26] "Most painters require direct contact with objects in order to feel that they exist, and they can only reproduce them under strictly physical conditions. They look for an exterior light to illuminate them internally. Whereas the artist or the poet possesses an interior light which transforms objects to make a new world of them -- sensitive, organized, a living world which is in itself an infallible sign of divinity, a reflection of divinity."[27] Because the light-filled space that the artist finds within himself reflects the divine, it brings with it a communion with nature, and gives birth to art which is true to nature. "Awakened and supported by the divine, all elements will find themselves in nature."[28]

Our investigation thus far enables us to see the profound truth of Kandinsky's words about Matisse, quoted at the head of this essay: "He paints ‘images’" and in these "images endeavors to reproduce the divine. To attain this end he requires as a starting point nothing but the object to be painted (human being or whatever it may be) and then the methods that belong to painting alone, color and form."[29]

For Kandinsky, the freeing of art from the imitating of appearances allowed it to revert to its essence of line and pure tone. Matisse, committed to this most universal mode of painting, whose revival in France had been pioneered by Gaugin and Van Gogh, said to Teriade in 1936: "When the means of expression have become so refined, so attenuated that their power of expression wears thin, it is necessary to return to the essential principles that made human language. These are, after all, the principles that ‘go back,’ that restore life, that give us life. Pictures that have become refinements, subtle degradations, dissolutions without energy, call for beautiful blues, beautiful reds, beautiful yellows -- materials to stir the sensual depths in men. This is the starting point of fauvism: the courage to return to the purity of the means."[30] In a postcard to Manguin, sent from Moscow in 1911, Matisse had compared the icons to fauvist painting.[31] Later in life, reminiscing about his reaction to divisionist theories and rules, Matisse said he had to find a way to compose with the drawing in such a way as to enter directly into the arabesque with the color.[32] He stated that in the fauvist reaction against the diffusion of local tone in light, "Light is not suppressed, but is expressed by a harmony of intensely colored surfaces."[33]

In a letter to Charles Camoin in 1914, Matisse writes of his enthusiasm for a Seurat, intensely colored, with a band of blue dotted with violet at the top and the bottom, functioning like the repoussoir of the old masters. He has the Seurat on his wall alongside a photograph of Delacroix's "Jacob Wrestling with the Angel," which his daughter prefers because of its overall life. Comparing the two, Matisse notes that the Seurat remains grand, but "Delacroix's composition is more entirely created, while that of Seurat employs matter organized scientifically, reproducing, presenting to our eyes objects constructed by scientific means rather than by signs coming from feeling. As a result there is in his works a positivism, a slightly inert stability coming from his composition, which is not the result of a creation of the mind but of a juxtaposition of objects. It is necessary to cross this barrier to re-feel light, colored and soft, and pure, the noblest pleasure." The Delacroix, with its vital arabesque, is ultimately more significant to Matisse.[34]

In Matisse's Red Interior (Note: illustration 2 will be added), every line, every shape, every tone -- each of the pictorial elements -- is rhythmically related to all the other elements. The blue oval of the table top, pushing in front of the field of warm reds and yellows, jostles the lower left corner of the rectangle and pops the red shapes of the tomatoes to the fore. The contours of the table swing counterclockwise, descending on the left and ascending on the right to push the vase over to the left, flattening the right contour of the vase while the left contour bulges in response. The oval table is echoed above by the medallion enclosing a woman's profile, while the yellow medallion in turn is answered by the vertical yellow rectangle of the door standing ajar. This yellow door pulls strongly to the right, all the way to the edge of the canvas, yet resists conformity to the straight edge; the upper part of the door leans to the left, back toward the yellow medallion, and thus initiates a large counterclockwise rotation of the whole space of the painting, from the door to the mirror and then back down to the table, an amplification of the rotation of this very table. Balancing this rotation, however, is the movement of the great plane of red with its black zig-zags, from lower left to upper right, followed by the action of the yellow flowers outside, whose shape, a more active variation of that of the flowers in the vase, provides a counterpoint to the inclination of the yellow door.

Note that the light in the painting is a radiant encounter of fields of color, ceaselessly enriched by the ebb and flow of all the powerful and subtle exchanges that go on among the pictorial elements. There is not even any suggestion of incident illumination. Nor does the ample space of the painting make any allusion to perspective. The painting indeed manifests that "interior light which transforms objects to make a new world of them - sensitive, organized, a living world which is in itself an infallible sign of divinity, a reflection of divinity."[35]

The painting unfolds rhythmically as an organic whole in space and in time. Or rather, the space and time are born from the same unfolding. The painting is alive and active, manifesting the energy, the love, which creates and sustains nature, and with it space and time. The organic unfolding of all the elements within the painting is continuous with an unfolding of the painting toward the viewer -- the painting's splendor, clarity or radiance. The plenitude of being which the work manifests expands and radiates to illumine a beholder standing at even a distance of fifty or a hundred feet.[36] The painting is not limited by the dimensions of its frame. This expansiveness is a function of the mysterious reality- which painters call the picture plane: when all the lines, shapes and colors are interrelated in a dynamic and harmonic space/time equilibrium, the painting exercises a luminous presence which faces the viewer. The painting is "all light and face." We see here the true coincidence, the coinherence, of space, light and the picture plane. They are one reality, and that reality is an event, an event of transformation which, for Matisse as for the icon painters, manifests the divine.

Let us examine further this mysterious event which we call the picture plane. In painting, the picture plane cannot be taken for granted. It is not something one starts with, and which can be "preserved" or not, but something which must be achieved. Its achievement is simultaneous with the creation of pictorial space and light, because together they are constituent aspects of a single spiritual event. Matisse's colleague, Andre Derain, stated that color in painting does not come from the prism, but is a spiritual matter of inner life manifested by rhythm. Derain further observed that light in painting is not a principle of imitation, like illumination. Its purpose is not to illuminate objects, but to set the painting within its frame -- that is, to generate the picture plane. In a living painting, the rhythmic relation of lines, angles, shapes and colors results in what Derain described as a "paroxysm." The paroxysm is simultaneously the opening up of space and the breaking forth of radiance, of spiritual light, of real pictorial color. This paroxysm is thus tantamount to the event which is the picture plane. We see now that the picture plane is transcendent in its very essence. That is why it is so mysterious and hard to grasp. It only exists in an act by which it transcends itself. An infinity of pictorial space and light exists when, and only when, the picture plane exists. That is why in great painting the difference between flatness and space is not collapsed, but rather amplified -- and reconciled. It is also why when the picture plane is achieved, the surface on which the picture is painted feels right, and breathes the air of infinity, rather than feeling like a constriction or a limitation.

The joy of Matisse's knowledge of nature is the joy of a unitive knowledge which in its depth may be compared to conjugal knowledge. This joy lives on in the event of the picture plane, the paroxysm, ceaselessly renewed by the painting's rhythms. In this connection let us observe that the joyful light and space of the Orthodox icon are likewise that of a nuptial feast the feast of the eighth day of creation which is the fulfillment of God's espousal of his creation, now healed and transformed.

We can now see why icons are considered to be agents of inner, spiritual healing, why their light, their space, are therapeutic -- and why Matisse desired to create paintings that would have a therapeutic effect. The communion with nature, the participation in the divine, which is implicit in pictorial light and space, cannot but have a healing action. The event of the painting, the act of transcendence which constitutes the picture plane, the opening out of inner life and light, is itself the beginning of a process of spiritual transformation.

~ Endnotes:

1. W. Kandinsky, Concerning the Spiritual in Art. Intr. and tr. M.T.H. Sadler (New York: Dover Pub., 1977) p 17.

2. Jack Ham, ed., Matisse on Art. (Berkeley end Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1995) pp. 213, 218.

3. Ibid., p. 178.

4. Guillaume Apollinaire, "Les Russes," Gil Blas, April 22, 1911.

5. Cited in French in Alfred Barr, Matisse, his Art and his Public. (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1951), p.555.

6. "Matiss v Rossii osenju 1911 Goda," Trudy Gosudarstvennogo ermitaza, vol. 14 (1973), pp. 167-84. Quoted in Pierre Schneider, Henri Matisse. (New York: Rizzoli) 1984, p. 303.

7. Schneider, pp. 303-304.

8. Ibid., p. 14

9. Jack Flam, Matisse: the Man and His Art. (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1986), p. 323.

10. "Matisse in Moscow," Utro Rossi, Oct. 27, 1911, in Y.A. Rusakov, op. cit., p. 288.

11. Quoted in Matisse on Art, p. 296.

12. quoted by Pierre Schneider in the catalogue: H. Matisse. Exposition du Centenaire. (Paris, 1970), p. 13.

13. quoted in French in R. Escholier, Matisse from the Life. (London: Faber, 1960), p. 203.

14. Pierre Schneider, Henri Matisse. (New York: Rizzoli,1984), p. 10.

15. statement recorded in C. Zervos, Cahiers d'art, 5-6, 1931.

16. Matisse on Art, p. 110.

17. A clear and extensive treatment of this can be found in the book by the nineteenth century sculptor, Adolf Hildebrand, The Problem of Form.

18. St. Gregory of Nyssa, "In Hexaemeron," P.G., XLIV, pp. 72-3.

19. Amb., P.G. 91, 1148c.

20. Jack D. Flam, Matisse on Art. (New York, 1978), pp. 148-149. The quotation is from an interview conducted by Regine Pernoud and published in Le Courier de l'U.N.E.S.C.O., vol. VI, no. October, 1953. The translation given here is Flam’s, but I have inserted some of the words of the original French in brackets where I feel this is required by the subtlety of Matisse's expression.

21. Henri Matisse, Jazz. (Paris, 1947), quoted in Flam, Matisse on Art, p. 113.

22. loc. cit.

23. Ibid.

24. Matisse on Art, p. 207.

25. Ibid., p. 178.

26. Ibid., p. 156.

27. Ibid., p. 89.

28. Ibid., p. 156.

29. W. Kandinsky, Concerning the Spiritual in Art. Intr. and tr. M.T.H. Sadler. (New York: Dover Pub., 1977), p. 17.

30. Matisse on Art, pp. 122-123

31. Schneider, 1984, p. 309.

32. Dominique Fourcade, ed., Henri Matisse: Ecrits et propos sur l’art. (Paris: Hermann, 1972), footnote, p. 93.

33. Matisse on Art, p. 58.

34. Fourcade, ed. op cit., footnote, pp. 93-94. Translation of part of the letter given in Matisse on Art, p. 275.

35. Matisse on Art, p. 89.

36. Pierre Bonnard advised painters to take their canvases outside from time to time and view them from at least thirty feet away in order to judge them properly. The ability of a good painting to carry over distance is to a surprising degree independent of the size of the canvas--- surprising, that is, until one understands the reason.

~

Lazarus James Reid

#matisse#art article#painting#Sergei Shchukin#Russia#jacob’s well#tretiakov gallery#Sergei Diaghilev#icons#the chapel of the rosary#matisse jazz

3 notes

·

View notes