#QueerMedia

Text

Family Porn Night: A Movie Review

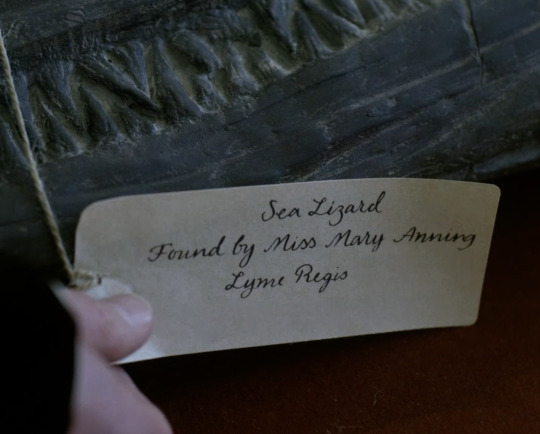

As the opening titles come on screen, we hear but don’t see the sound of water sloshing in a bucket, being wrung out of a rag, heavy breathing, scrubbing. The titles fade and we see a woman, on her hands and knees, cleaning the floor of what we eventually learn is the British Museum. We hear footsteps, the sharp bark of a man saying, “Move!” as he and several others, carrying a fossil on a stretcher, tramp across the floor she has just cleaned. On the fossil we see a handwritten tag that reads “Sea Lizard found by Miss Mary Anning Lyme Regis.” The man in charge harrumphs, pulls the tag off, and replaces it with a tag that says “ICHTHYOSAURUS LYME REGIS Presented by H. Hoste Henley Esquire.” He has written Mary Anning out of history.

Ammonite is writer/director Francis Lee’s attempt to write Mary Anning, and queerness, back into the world of 1840s Britain. The plot is a simple romantic drama with an enigmatic ending. Simply put, Mary Anning falls in love with Charlotte Murchison but chooses to remain alone rather than give up her career by moving with Charlotte to London. The complex beauty of the movie comes from Lee’s subversion of audience expectations as well as some traditional film-making procedures. But how well he succeeded is still up for debate. The movie flopped at the box office, grossing under $1,000,000 world wide, failing to recoup the $3,000,000 distribution rights, let alone the $13.4 million in production costs. Carson Timar of “Clapper” wrote, “This is a bland and empty feature that feels like an ancient fossil void of any passion or substantial emotion” (Timar, 2020). With movie darling Kate Winslet in the lead and rising-star Saoirse Ronan playing opposite her, the lackluster reception is surprising. Does Ammonite, like Moonlight, prove that queer films need to be sexless to be successful (Lodge, 2017), or can we ascribe Ammonite’s box office bomb to other causes? I believe the erotic scenes are only part of the answer. While I disagree with the Rotten Tomatoes reviewer who said, “Simply out [sic], Ammonite commits that cardinal sin of being truly boring” (Andrew L., Ammonite, 2022), the slow pace likely contributed to Ammonite’s poor, reception sealing Ammonite’s fate as a “perfectly respectable, eminently professional slice of prestige arthouse” (Clarke, 2021) doomed to accrue financial losses. The other variable is not lesbian eroticism per se but rather lesbian eroticism scripted by women for the female gaze. In other words, two of the components that Lee uses to queer cinema are the very things that make it a failure in the public sphere.

In Ways of Seeing (1972), John Berger writes, “Seeing comes before words…It is seeing which establishes our place in the surrounding world” (p. 7). Lee builds Mary Anning’s rocky world slowly, introducing the audience to her visually before any words are spoken. Although this is the well-trodden territory of a period romance, this is a romance that reimagines history. Mary Anning was a real person from Lyme Regis, UK, who sold fossils (called ‘relics’ in the movie) to the British Museum beginning at age 11. But there is no evidence of her having a love interest, gay or otherwise. Some of Anning’s descendants have questioned Lee’s manipulation of her story, which highlights the problems with “outing,” or ascribing queerness to public figures. Posthumously attributing identities to people may be a tempting way to queer the past by showing “the world that many widely admired and respected men and women are gay” (Duggan, 2006, p. 153), but it can be problematic to apply a modern understanding of queerness to people who cannot confirm or deny those identities and who may or may not have accepted our definitions. In other words, even if Anning had engaged in romantic liaisons with other women, she may not have seen those relationships as queer, either in the sense of their being gay or out of the ordinary. Lee attempts to “honor the complexity of [Anning’s] differences” (Duggan, 1991, p. 155) by building a rich and textured world that includes multiple ways of forming relationships. Even while I acknowledge that “outing” Anning may be problematic, I still find joy in the sapphic world Lee imagines.

Lee’s femme-centered world doesn’t limit gender expression. Mary is a complex character, outwardly mirroring the coldness of her Lyme Regis beach but with a depth of feeling we catch in glimpses, most often through Winslet’s uncanny ability to convey emotion without speaking. Mary plays with gender performance, but retains her essential womanness, subverting early Hollywood’s “gender-inversion stereotype” (Bernshoff & Griffin, 2004, p. 7). She smokes and swears frequently, has dirty fingernails and armpit hair (appropriate for the time but not for Hollywood). When engaged to take care of Charlotte, who has “melancholia,” Mary says, “There looks to be fuck all wrong with you to me” (0:28:30). She genuinely loves finding and cleaning fossils. When Charlotte, who has recently lost a baby, asks Mary if she has children, Mary replies, “I have my work. I don’t need children as well” (00:51:38).

As the movie progresses, Lee reveals Mary’s tender (feminine) side, showing her caring for a sick Charlotte and, at one point, wearing a dress and perfume to attend a recital with Charlotte. After Charlotte returns to London, Mary receives a letter from her. Before opening it, Mary lifts it to her nose hoping to catch the perfume Charlotte wore.

Charlotte originally acts as a more traditionally feminine counterpoint to Mary’s masculinity. She wears bonnets and bows, black to show mourning, and delicate heeled shoes. She’s weak and pale from what her husband calls “melancholia” but which could more honestly be called depression, either from the loss of a baby or the pressure of passing as heterosexual. Her angst doesn’t last long. Within a few scenes, Charlotte sets aside her expensive clothing for rugged boots to better accompany Mary on her morning fossil huts. Color comes back into her cheeks, she laughs more frequently, and she fully engages in Mary's work. Charlotte’s awakening coincides with her temporary move from London to Lyme Regis while Mary simply is regardless of her location. This juxtaposition has been noted by Karl Schoonover and Rosalind Galt in Queer Cinema in the World (2016), “Some people have to travel to express their sexuality and/or gender, and others stay home” (p. 77).

Lee contrasts elements in order to show how the women grow closer while retaining their core identity. While lying in bed together, Charlotte says, “Say it again.” Mary then recites a limerick:

There was a young woman named Sally

Who loved the occasional dally.

She sat on the lap

Of a well-endowed chap

And she said, ‘Oh, you’re right up my alley” (1:15:45).

Charlotte smiles, having let go of some of her feminine-coded sensibilities, while Mary, nude and vulnerable, curls trustingly next to her.

In a similar contrasting scene, Mary wades into the white-cap waves, turns, and waits for Charlotte to join her. Charlotte slowly walks out, frightened. She reaches Mary, who grabs her around the waist and smiles. Charlotte clings to her, still afraid, but feeling safe in Mary’s arms. This scene is the only time we see Mary laugh, and her joy mirrors the bright sun and warm filter unusual in this movie. Here, Mary both protects and pushes Charlotte, never demanding Charlotte change but offering help if Charlotte chooses to take it.

Two intimate scenes in the movie show just how transformative Lee’s film-making is. Rather than hire an intimacy choreographer, Lee, Winslet, and Ronan scripted each sex scene by themselves, relying on open communication and the trust they had in each other. These aren’t the “throw her up against the wall with no foreplay” scenes so common in heterosexual sex scenes, nor are they the “soapy shower and giggling college girls” lesbian scenes meant for the male gaze. Instead, Ammonite’s “staging of sexuality, gendered embodiment, and nonheteronormative sex” (Schoonover & Galt, 2016, p. 11) successfully disrupt heteronormative ideas about how sex happens, who enjoys sex, and how they enjoy it.

“Don’t take no for an answer,” seems to be the mantra in many erotic heterosexual scenes, but the first erotic scene in Ammonite queers cinema by pausing the action mid-point. After Charlotte kisses her, Mary kneels in front of Charlotte. Before going further, she waits, staring up at Charlotte until Charlotte raises her own skirts in enthusiastic consent.

The final erotic scene queers cinema by subverting audience expectations. The night before Charlotte is to return to London, they lovingly caress each other’s faces. Noses touching, they gently kiss. As the scene progresses, they each guide the other’s hand, sometimes moving the hand to their own pudendum and sometimes away. Lee uses close camera angles, focusing on how the women’s bodies move together. The camera stays on each woman’s face as she climaxes. These are women showing each other how they want to be touched. Each woman confidently directs the actions of the other while asserting her own right to pleasure.

Both erotic scenes are enigmas in the movie industry: female pleasure for a female gaze. Per Schoonover & Galt, cinema is “an apparatus of desire, endlessly reconstituting what Jacqueline Rose called sexuality in the field of vision” (2016, p. 11). Eroticism scripted by women, focusing on how women experience pleasure, queers film in a uniquely feminist way; it uses “the potential of the erotic to remake the cinematic desire machine” (Schoonover & Galt, 2016, p. 11) reflecting the sapphic world Lee has created. I argue that the initial sex scene with a focus on enthusiastic consent and cunnilingus is a “counterpublic logic of visibility” that queers media by “extending representation beyond mainstream fantasies about white femme lesbians” which is “achieved in and through sex acts” (Schoonover & Galt, 2016, p. 12). Both erotic scenes, as well as other hinted-at but not seen moments, occur in Mary's home or on Mary's beach, "locating lesbian desire in a domestic setting and turning to familial intimacies as a place where women might find fulfillment beyond the strictures of marriage" (Schoonover & Galt, 2016, p. 19). Once the women are in London, in Charlotte's male-owned home, the intimacy (physical and emotional) falters and dies.

Gender expansiveness and eager consent are not the only way Lee queers cinema. We learn that Mary had a relationship with another woman in her town, Elizabeth Philpot (played by Fiona Shaw), which ended when Mary’s father died. Elizabeth acts as an oracle, guiding Mary in her relationship with Charlotte and foreshadowing the end of that same relationship. When Mary’s mother, Molly (played by Gemma Jones), dies, Elizabeth visits Mary and says, speaking of their past romance, “I wasn’t sure I could live up to you. Or your expectations of me…You seemed to do everything you could to be distant…It seems your Mrs. Murchison has been able to unlock something in you I couldn’t…” (1:34:16). Here, Elizabeth references the softness Lee showed in the limerick and beach scenes. It’s also vital to note that neither woman seems to have faced ridicule because of their relationship, nor do they seem to have kept it particularly quiet. I appreciate seeing a lesbian relationship that doesn’t double as a morality play.

Mary follows Elizabeth’s advice and accepts an invitation to visit Charlotte in London. From this point on, Lee relies more heavily on language and sound to convey how small and out-of-place Mary is. This sudden cinematic shift undermines the queer worlding I found so lovely in the first two-thirds of the movie.

At London port, bodies (all of them male except hers) are in constant motion. They press around her while they yell to and at each other. We’ve lost the cool tones of Lyme and found harsh sunlight. Lee’s feminism is not subtle. If "(queer) film theory is always a feminist project" (Schoonover & Galt, 2016, p. 11), Lee hits the brief, but he does so with a sledgehammer.

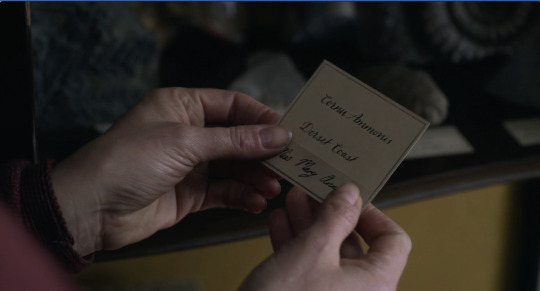

At Charlotte’s house, Mary opens a curio cabinet containing fossils she helped Roderick Murchison (played by James McArdle) find. The tag on one of the fossils reads, “Cornu Ammonis. Dorset Coast. Miss Mary Anning.” Taking it out, Mary notices the last line has been pasted on top of the original line. Pulling it back, Mary reads, “Mr. Murchison Esq.” Lee doesn’t just allude to his correction of the historical record, he screams it.

The breakup scene between the two women is similarly heavy-handed. Charlotte shows Mary to a room she has decorated for her “so we can be together always.” Winslet does an excellent job conveying a parade of emotions, but the ensuing dialogue lacks finesse and undermines the acting prowess of both Winslet and Ronan.

Mary doesn’t directly answer Charlotte, instead saying, “I really shouldn’t…I wanted to see my relic in the British Museum today….”

When Charlotte expresses dismay and repeats her offer to provide Mary with a new home, Mary says, “You presumed I’d just be fitted into your life here, like one of my relics in your fine glass case…Will you label me, too?” (1:47:45). Charlotte insists, “I want this to be different. Our different…I don’t want to go back to the life I had before you” (1:48:07). The unnatural, forced dialogue breaks Lee's “show, don’t tell” rule and makes it hard to access the emotion Lee wants us to feel.

Mary rushes out of the house, and we next see her in front of her ‘relic’ at the British Museum. She notices the tag, the first time she’s seen it, and, looking up, sees Charlotte gazing at her across the glass-encased fossil. The camera pans out in one of the few long-shots of the film and we see the women, faces covered by bonnets, caged fossil in the middle. Men in top hats circulate around them.

As if afraid that he wasn’t clear enough, in the last scene Lee reminds the viewer of his intentions. Mary walks through a portrait gallery showing the men who helped create and run the British Museum. The very last image is Mary, facing back toward the gallery, framed.

It isn’t just the shift to London or the sudden heavy-handed cinematography that jars the viewer. The final 20 minutes of the film tackles class issues but ignores broader themes of imperialism and racism.

Classism is seen best in Mary’s interactions with Charlotte’s housekeeper. When the housekeeper answers Mary’s knock, she assumes from Mary’s rough clothing that she’s a hired worker. The housekeeper says, “Tradesman’s entrance is around the side. Go all the way back” (1:41:29). After explaining who she is, Mary is shown to the drawing room and Charlotte greets her with a passionate kiss. Mary glances at the housekeeper, but Charlotte says, “Oh, that’s just the maid,”(1:44:23) at which point the housekeeper side-eyes the women and shuts the drawing room door. Class bias goes unchallenged by any of the characters even in light of Charlotte’s relationship with poor, rural, crass Mary. Additionally, there are no Black, Indian, or Egyptian people. At the height of British imperialism, there should be several non-white people, especially once the action moves to London.

Ammonite does not employ “an anti-imperialist stance that de-privileges the Western queer film canon” (Schoonover & Galt, 2016, p. 15) in part because it fails to address Britain’s imperialism and in part because it, too, uses Western imperialist structures to (unsuccessfully) promote itself. Originally available only in theaters and on Amazon, viewers can now access it through other streaming services such as Hulu and Vudu. All subscription based. All part of the cinema industrial complex.

I enjoyed Ammonite. At least, I enjoyed it the second time. The first time, thinking it would be similar to the 2019 movie Wild Nights With Emily, I convinced my husband and my two daughters, aged 18 and 15, to watch it with me. As a heterosexual-passing pan woman who has been in love with Winslet since the 1995 remake of Sense and Sensibility, I had looked forward to seeing her in a role that more accurately represented me. However, sitting with two of my children I felt my face turn red. In a brilliant parenting moment /s I tried to cover up my embarrassment by saying, “This is important. People with vaginas experience sexual pleasure differently than the movies make it seem. As people with vaginas, we have to advocate for our own pleasure,” at which point my 15 year old ran out of the room, eyes closed, hands over her ears. The 18 year old stayed, but mostly to ridicule my parenting. Two years later, when my daughters feel particularly spicy, they’ll say, “Hey, mom! Remember when you made us watch lesbian porn?”

They echo criticism from the public. One reviewer said, “Serious concerns that a famous lady has been wronged by the Lesbian storyline. Proof/truth? As for the soft porn. Why? Nothing more than eroticism for a very small segment of the population” (Alastair G, Ammonite, 2022). Even though I disagree that the movie is soft porn, and I disagree that we're a "very small segment of the population," I think Alastair hits (unwittingly) on the reason the movie failed. A combination of the slow pace and sex by and for women, two of the aspects that queer the movie, result in an insurmountable barrier for a public that is trained to prefer action and rough-and-ready sex created for the male gaze.

References

Benshoff, H., & Griffin, S. (2010). In Queer Cinema the film reader (pp. 1–15). essay, Routledge. Taylor & Francis Group.

Berger, J. BBC and Penguin. (1972). chapter 1. In Ways of seeing (pp. 7–34).

Canning, I., Sherman, E., O’Reilly F.C. (Producers), & Lee, F. (Director). (2020). The Ammonite [Motion picture]. United Kingdom: Lionsgate.

Clarke, D. (2021, March 26). Ammonite: Even the saoirse ronan-kate winslet sex scenes are too respectable. The Irish Times. Retrieved October 10, 2022, from https://www.irishtimes.com/culture/film/ammonite-even-the-saoirse-ronan-kate-winslet-sex-scenes-are-too-respectable-1.4517920

Duggan, L., & Hunter, N. D. (2006). Chapter 12: Making it perfectly queer. In Sex wars: Sexual dissent and political culture (pp. 149–163). essay, Routledge.

Lodge, G. (2017, January 5). Does Moonlight show gay cinema has to be sexless to succeed? The Guardian. Retrieved October 10, 2022, from https://www.theguardian.com/film/2017/jan/05/does-moonlight-prove-that-gay-cinema-has-to-be-sexless-to-succeed

Na. (n.d.). Ammonite. Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved October 10, 2022, from https://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/ammonite

Schoonover, K., & Galt, R. (2016). Introduction Queer, World, Cinema. In Queer Cinema in the world (pp. 1–34). Duke University Press.

Schoonover, K., & Galt, R. (2016). Figures in the World: The Geopolitics of the Transcultural Queer. In Queer Cinema in the world (pp. 35-78).

Timar, C. (2020, December 6). Ammonite. CLAPPER. Retrieved October 10, 2022, from https://www.clapperltd.co.uk/home/ammonite

by Bryn Brody

#queermedia#Ammonite#AmmoniteMovie#Saoirse Ronan#Kate Winslet#Lesbian Film#Francis Lee#Movie Review#Mary Anning#Lyme Regis#romance movies

73 notes

·

View notes

Photo

May the Lord, who frees you from sin, save you and raise you up.

Evil 3x09

#evil#evil series#eviledit#evil cbs#evil paramount#tvfilmsource#userbbelcher#tvgifs#tvedit#smallscreensource#queermedia#queermedias#lgbtqedit#i am so stupidly sad over this oh my god dude#evil gifs#evil 3x09#blood tw#*mine

65 notes

·

View notes

Text

Supporting the LGBTQ+ community for over 30 years! http://gaycalgary.com

#gay#lgbt#lesbian#calgary#yyc#gayyeg#yeg#edmonton#canqueer#queer#lgbtq#gayhistory#gaycalgary#gaymedia#queermedia#queerhistory#gaytravel#travel#gaypride#pride

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

if you ever want me to watch a show or movie just tell me there are queer people

0 notes

Text

youtube

I know this isn't assigned or anything, but I wanted to just to post some of my favorite queer music as the class goes on! I have quite a few artists that I am a big fan of that are queer and/or make queer music, and so I want to show them off! This is Keep for Cheap, a Minnesota based band lead by lead singer duo and couple Kate and Autumn! The alum of Hamline University met in college choir, and soon started their self proclaimed Prairie Rock group, so take a listen to On The Floor!

1 note

·

View note

Photo

#sebastian croft#joe locke#cast#gifs#heartstopper#heartstopperedit#dailylgbtq#lgbtsource#queermedias#userkaylee#usersage#usermason#tuserjen#userkosmos#userlourdes#*#by lucie#1k

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

i watched a movie last night and it really reminded me of my ex so i’ll share it here instead. it’s a disney movie called strange world and i never saw any promo for it or heard about it at all but it’s pretty new. it made me real emotional because it focuses on father-son relationships and the youngest main character is biracial and queer which i’ve literally never seen in a disney movie ever??? like i can’t remember a single queer disney character let alone a main character and it makes me so happy because disney is so selective with their wokeness and like even luca which was totally a gay film isn’t technically gay bc they never really confirm it. but this guy is just crushing on another guy and NO ONE is weird about it it’s just totally normal and even his grandpa who he just met says NOTHING about it being a guy and just jumps into giving him advice about how to impress his “fella”. i died. i also didn’t know it was gonna be queer and it was a total surprise that just made me so happy and also made me think about my ex because she loves disney movies and queer rep and luca made her cry happy tears so i’m just hoping she’s seen this movie and if she has i know it made her really happy.

1 note

·

View note

Text

First day on Tumblr. I’m in search of places to be #queer, autistic, and brown online. Here to post all my #queermedia fandoms. This week’s fave #shaunajackie

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

May 2023 issue (# 330) of Erie Gay News is now out! See more at https://ift.tt/TQ4Neyw. Thanks to our advertisers and volunteers! #gay #lgbtq #Erie #gaypress #queermedia https://ift.tt/NzHOq2V

0 notes

Text

God's Own Country: A Happy Ending for Gay Film

In Yorkshire, northern England, 24-year-old Johnny Saxby lives with his father, Martin, and grandmother, Deirdre, and runs a family farm together. Johnny has to do endless farm work day in and day out, so in his free time, he often numbs himself with alcohol and sex. One day, a Romanian migrant worker, Gheorghe Ionescu, was hired by Martin to help with the busy lambing season. Johnny does not get along well with this quiet and handsome 27-year-old young man until one day he tackles Johnny to the ground and warns Johnny not to call him "gypsy" again. On the next day, they have a rough and passionate sex in the dirt and later gradually become closer. When Martin suffers a second stroke, Johnny realizes the responsibility of running the farm falls entirely on his shoulders. He asks Gheorghe if he can stay with him and maintain the farm together, but Gheorghe believes if they cannot redefine their relationship, this plan will not survive. Johnny then gets upset and drinks to excess and has a random sex with another man, which is found out later by Gheorghe, so Gheorghe leaves the farm with sorrow and anger. But in the end, Johnny brings Gheorghe back and Gheorghe moves into the house from the original caravan.

The above description is about the British film God's Own Country, written and directed by Francis Lee in 2017, which won the world cinema directing award at the 2017 Sundance Film Festival as the only UK-based production. This film is partly based on Lee's own experience, who is a gay people used to live in Yorkshire. As an uncommon gay film with a happy ending, God's Own Country expands queer media territory into the countryside and migrants. While God's Own Country presents a new perspective to view gay people, it also reinforces problematic narratives through its depiction of traditional masculinity, representation of migrant, and "normalization" of gay identity. With three main themes presented, this review post also discusses the connection between masculinity and gender performativity, migrant and intersectionality, and gay identity and homonormativity.

From the character setting, and storyline, to the environment, God's Own Country is permeated with a traditional and binary "masculinity". The protagonist, Johnny, is a young sheep farmer living in the Yorkshire countryside who often engages in binge drinking and furtive casual sex. When he finds the one he wants to stay with (Gheorghe), he messes up since he does not know how to deal with this romantic relationship. And when he tries to bring Gheorghe back, it seems very difficult for him to express his apology. The depiction of such character is easily connected to a kind of traditional "masculinity" that is unemotional, violent, strong, high self-esteem, etc. Or, to put it in another way, an aggressive young man lives in a wild farm who does now know how to start an emotional communication.

Judith Butler (2006) argues that "there is no gender identity behind the expressions of gender; that identity is performatively constituted by the very 'expressions' that are said to be its results" (p. 34). In other words, "our gender is our expressions and behaviours (rather than those expressions and behaviours being the result of some underlying gender identity)" (Barker & Scheele 2016, p.79). People's gender then is more like an expression that is believed to be appropriate and correct within their cultural environment rather than a fixed nature within their bodies. In this sense, the masculinity of Johnny is more like an "intelligible" way to perform within his condition - a young sheep farmer in the countryside. The "good" thing may be Johnny, as a gay man, is not depicted in a stigmatized or stereotypical way that happens in many shows, but its depiction seems to reinforce the binary understanding of gender.

youtube

God's Own Country was released in 2017, which coincides UK's attempt of withdrawing from the European Union. Gheorghe, as a Romanian migrant worker in the film echoes the issue of migrants in Britain. Both as gay men, the nation, race, and class of Gheorghe is quite different from that of Johnny. Such demographic factors are greatly influencing the way Gheorghe interacts with Johnny who is a white, work-class, native British. When they first met, Johnny called Gheorghe a "gypsy". Later when they are in the bar, a white racist there also deliberately teases Gheorghe because of his identity.

Intersectionality refers to the overlapping of social categorization and how it is linked to the interconnected oppression. Doty (1993) also argues that cultural factors such as "class, ethnicity, gender, occupation, education, and religious, national, and regional allegiances influence our identity construction" and "can exert influences difficult to separate from the development of our identities queers" (p. 5). Although Gheorghe's identity of being gay does not bring him too much direct discrimination in the film, his race and class affect how he interact with Johnny and other people (such as the white racist in the bar mentioned above). And Gheorghe's conflict with Johnny is raised due to his identity, i.e. how Gheorghe as a Romanian migrant worker has a romantic gay relationship with a white, British farmer.

Moreover, how the film represents Gheorghe and his relationship with Johnny is also problematic. "The formal axe around which the film functions is the act of looking and being looked at, in particular the suspicious staring of the foreign 'outsider' by the white 'insider'" (Williams 2020, p.77). That is to say, the presentation of a Romanian migrant is from the viewpoint of a white British man. Although Gheorghe as a migrant seems to be depicted as the "savior" of British white man Johnny, Gheorghe's intersectional identity is actually not fully represented but more portrayed as the support or supplement of the main white character. For example, it is Gheorghe who saves Johnny from the heavy workload and mental loneliness, and teaches him how to "love" someone instead of just having brutal sex.

Unlike Brokeback Mountain (2005) or Boys Don't Cry (1999), queer characters do not struggle too much with their identity and social discrimination in God's Own Country. The gay identity of Johnny and Gheorghe seems to be very "natural" and "ordinary". Even when Deirdre, Johnny's Grandmother, finds a used condom in Johnny's room and realizes that her grandson may have sex with another man Gheorghe, she only emphasizes to Johnny that "he is only here to work". Johnny's family seems to accept their gay identity and relationship very well, or in another way, their gay identity and relationship are somehow "normalized" in the film. Furthermore, within their own relationship, Gheorghe is depicted as a gentle lover who is trying to tame his aggressive partner. And their relationship from the hostile beginning to the happy ending is very similar to traditional Hollywood romantic heterosexual films.

Homonormativity "is a politics that does not contest dominant heteronormative assumptions and institutions, but upholds and sustains them, while promising the possibility of a demobilized gay constituency and a privatized, depoliticized gay culture anchored in domesticity and consumption" (Duggan 2002, p. 50). In other words, although gay people may seem to be accepted and included in the mainstream or heteronormativity dominated system, they are actually framed and hidden under the heteronormativity and thus lose their identity. Although it may be good that the gay identity and relationship of Johnny and Gheorghe are treated as nothing special, the essence behind that may be the gay culture is depoliticized and thus loses its nature of being gay. Even gay couples may no longer be depicted as gay couples but heterosexual couples.

As an Asian, heterosexual college student, I may not be able to resonate with the film too much. Probably the scene where Gheorghe is discriminated against by a white racist can trigger some of the experiences around me. And although this film tells a story of a gay couple, the way this film puts their relationship yet is quite "familiar" to me, because of the last point I discussed above (homonormativity).

Originally, the explicit sex scene in this film makes me feel a little bit "awkward" and I feel like such scene is not very necessary. However, my knowledge in queer media studies makes me reconsider the role of sex in this film and I find that it is actually very "meaningful". Johnny used to be very aggressive in sex, but after the "tameness" of Gheorghe, Johnny gradually enjoys the touch and understands that there can be "love" (or emotion) in sex instead of just fulfilling the sexual needs. That is to say, the sex scene in this film actually sees the growth of a young man, the understanding of love, and the finding of oneself.

--- Miles

References

Barker, M. & Scheele, J. (2016). Section on Butler. In Queer a graphic history (pp. 73-83). Icon Books.

Butler, J. (2006). Identity, sex and the metaphysics of substance. In Gender trouble: Feminism and the subversion of identity (pp. 22-34). Routledge.

Doty, A. (1993). There's something queer here. In Making things perfectly queer (pp. 1-16). University of Minnesota Press.

Duggan, L. (2003). Equality, Inc. In The twilight of equality: Neoliberalism, cultural politics, and the attack on democracy (pp. 43-66). Beacon Press.

Williams J. (2020). Queering the cinematic field: Migrant love and rural beauty in God's Own Country (2017) and A Moment in the Reeds (2017). In Queering the migrant in contemporary European cinema (pp. 72-86). Routledge.

#QueerMedia#movie review#god's own country#gender performance#intersectionality#homonormativity#josh o'connor#alec secăreanu#Youtube

65 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Father Ignatious. Tell him..I-I love...

#evil#evil series#evil cbs#evil paramount#eviledit#tvfilmsource#tvcentric#tvedit#tvgifs#usertelevision#lgbtqedit#queermedias#evil gifs#evil 3x10#THIS SHIT HURTED MAN#*mine

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

GayCalgary Business Directory - Please add your Business or Group listing today! Dropped from over 750 listings down to just over 350 after a major clean-up of the listings. http://www.gaycalgary.com/directory

#gay#lgbt#lgbtq#lesbian#queer#gayyeg#yeg#edmonton#yyc#calgary#gaycalgary#alberta#gaybusinessdirectory#reddeer#lethbridge#medicinehat#gaytravel#travel#gaymedia#queermedia

0 notes

Text

Adolescent Identity in Aristotle and Dante Discover the Secrets of the Universe

The Young Adult genre of literature has witnessed quite the popularity boom since the turn of the 21st century. As more teenagers find themselves fascinated with reading about characters that share similarities to them, more authors are finding ways to create accurate representation of diverse communities (Warrior Cats is a whole different story). Aristotle and Dante Discover the Secrets of the Universe is a novel centered around two queer Mexican American teenagers navigating the world around them while simultaneously trying to understand who they are. The story highlights the significance of identity in the psychological development of adolescents, illustrated through nationality, sexual orientation, and gender roles.

The top row of photos follows the idea of adolescent development. The photo in the top left shows a starry night in the desert, a picturesque scene that Ari enjoyed viewing quite often. Anytime he wanted to clear his mind, the stars would provide an escape. This represents Ari’s psychological development of his independence. He goes out of his way to ensure his autonomy, often jokingly referring to his mother as a fascist. Driving out to the desert and staring at the sky was method of self-reliance he could always depend on. As Laurence Steinberg and Susan B. Silverberg found in their study, The Vicissitudes of Autonomy in Early Adolescence, “Studies in the development of self-reliance… indicate that this aspect of autonomy increases steadily as youngsters move from the preadolescent to the late adolescent years” (p. 843). Saenz wrote Ari as a young boy fascinated with having a life that was his own to live, which is a very common pattern of thinking and behaving for teenagers. The picture in the top right is indicative of this development too, representing Ari’s use of silence as a coping mechanism. In one of his first conversations with Dante after the surgery, Ari says “Rule number one: We won’t talk about the accident. Not Ever” (p. 128). Ari chose to let the traumatic car accident live and fester inside him, reverting to silence in order to get by. Later in the story, we see a continuation of his development as he begins to open up more, eventually coming to terms with his identity and love for Dante. The center photo in the first row illustrates Ari’s constant questioning of masculinity and what ‘makes’ a man. This is evident in one of the earlier scenes in the story, when Ari overhears boys at the public pool make misogynistic comments about a woman lifeguard on duty. Gee, Allen, and Clinton found in their study, Language, Class, and Identity: Teenager Fashioning Themselves Through Language, that not only is language incredibly significant for adolescent development, but the language certain teens use is associated with the ‘type’ of person they are, much like how Ari feels as though the boys at the pool are a different ‘type’ of masculine.

The second row of photos revolves around Ari’s identity-forming through the people around him. The first photo in particular represents Ari and Dante’s Mexican American nationality. Ari seems to rarely question ‘how Mexican he is’, while Dante, on the other hand, actively tries to distance himself from his heritage. His fluency in Spanish and his understanding of Mexican culture is limited compared to Ari’s. Adolescent development does not only consist of forming an identity we like, but it also includes pushing out the parts of us we are unfamiliar or uncomfortable with. This conclusion is also reached in the third photo. This represents Ari’s imprisoned older brother who he knows little about for most his adolescence. While Ari wishes that he had been a more present figure in his life, he also knows that he does not want to go down the same path. His own identity conflicts for a moment: his love for Dante versus his brother’s crime against a transgender woman. The center photo depicts the activities that Ari and Dante’s parents – or more specifically, fathers – partake in together. It symbolizes the differences between the two. Ari’s father is reserved and stoic, while Dante’s is talkative and doting. Ari constantly compares the two as he tries to navigate the choppy waters of masculinity. Saenz writes, “I wondered what that would be like, to walk into a room and kiss my father” (p. 26). Ari is confronted with two contrasting versions of fatherly love and affection, and throughout the story we see him figure out his tolerated level of affection and silence from father figures.

The third row of photos highlights the part of Ari’s identity that focuses on sexual orientation and softness. The first photo represents his mother, who kept in constant communication with her sister, even after the rest of the family shunned her for being lesbian. The audience can tell that finding out about this has a significant impact on Ari. It simultaneously encourages and discourages him to come out. While he can be comforted with the notion that his parents would accept him, he was reminded of the way queer people were treated, not just by strangers, but also by family. The second photo represents one of the largest plot points of the story: Ari and Dante falling in love, or rather, falling in love and coming to terms with it. While Ari’s affection is obvious for the audience, it isn’t until the final pages when he himself understands that he likes Dante. Dante himself isn’t without his own struggles, he admits to Ari that he’s worried his parents won’t be happy about his identity because he wouldn’t be able to give them biological grandchildren. Angel Daniel Matos describes this phenomenon is his article, “A Narrative of a Future Past”, pointing out that “Because of this blame placed on queer people and communities, the engagement in practices that pressure reproductive logics is framed as non-normative…” (p. 35). Dante is not alone in his feelings of guilt, as Saenz likely understood from being gay himself. The last photo represents Ari’s initial uneasiness with crying and emotion. While he chalks it up to feeling emasculating, it seems to stem deeper than that. He likely associates a lack of masculinity with being queer and is in denial of both things. Dante, on the other hand, cries often and a lot. He is unashamed about showing emotion and it sometimes proved to be unnerving for Ari.

This novel contains healthy representation for queer and Latinx teenagers, while also accurately following the psychological development of identities amongst adolescents. This book was released around the time that most of my peers were coming to terms with their sexualities. I’ve had multiple conversations with Latinx queer friends, with some telling me that this story helped them accept their identity. This narrative is important, it provides young teenagers the reminder that growing up isn’t easy and self-discovery won’t be as magical as people say it will be, but when you allow yourself to love wholeheartedly, you become free. Aristotle and Dante Discover the Secrets of the Universe shows that there’s a lot more to the identity-forming of teenagers that can conflict and tangle together but gives hope that it can all come together in the end.

________________________________________________________________

References

Gee, James Paul, et al. “Language, Class, and Identity: Teenagers Fashioning Themselves Through Language.” Linguistics and Education, vol. 12, no. 2, 2001, pp. 175–194., doi:10.1016/s0898-5898(00)00045-0.

Matos, Angel Daniel. “A Narrative of a Future Past: Historical Authenticity, Ethics, and Queer Latinx Futurity in Aristotle and Dante Discover the Secrets of the Universe.” Children's Literature, vol. 47, no. 1, 2019, pp. 30–56., doi:10.1353/chl.2019.0003.

Sáenz Benjamin Alire. Aristotle and Dante Discover the Secrets of the Universe. Simon & Schuster BFYR, 2012.

Steinberg, Laurence, and Susan B. Silverberg. “The Vicissitudes of Autonomy in Early Adolescence.” Child Development, vol. 57, no. 4, 1986, p. 841., doi:10.2307/1130361.

#ari and dante#adolescense#lgbtplus#literally the best book in the entire universe methinks#ya#queermedia#aristotle and dante discover the secrets of the universe

25 notes

·

View notes

Photo

aaron and rocco in the thing about jellyfish / alex and henry in red, white and royal blue

#queerlit#queerlitnet#the thing about jellyfish#red white and royal blue#rwrb#queermedia#mcquinstonsource#casey mcquiston#alex x henry#i was trying to find a quote about how long henry loved alex but i couldn't find one#also don't go reading the thing about jellyfish bc its some queer love story its actually not about that

18 notes

·

View notes