#Franz Waxman

Text

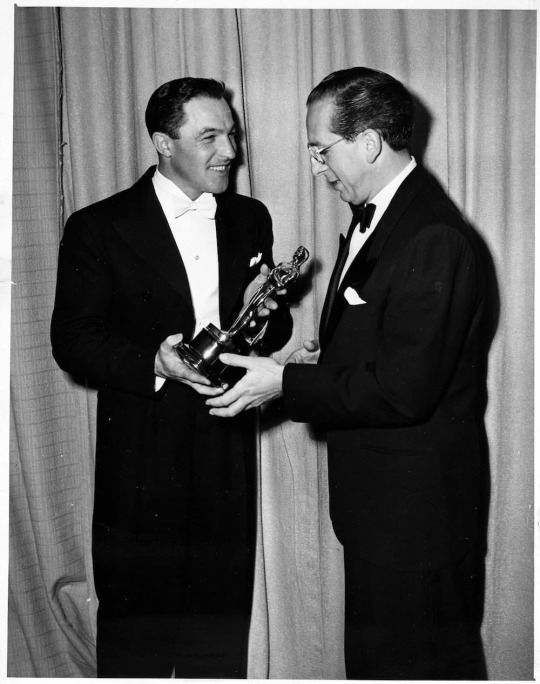

Franz Waxman accepts the Oscar for his score to Sunset Boulevard from Gene Kelly in 1951 #Oscars

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

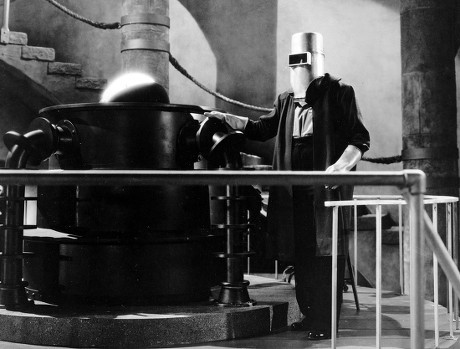

The Invisible Ray (1936)

"It was on such a night that Janos first caught his ray from Andromeda. Your father worked the guides. I held the detecting lens and... never saw again."

"Dear Mother Rukh."

"My son will not learn until too late, I fear, that the universe is very large, and there are some secrets we are not meant to probe."

#the invisible ray#1936#horror film#universal monster cycle#(at least tangentially)#lambert hillyer#john colton#howard higgin#douglas hodges#boris karloff#bela lugosi#frances drake#frank lawton#violet kemble cooper#walter kingsford#beulah bondi#frank reicher#paul weigel#georges renavent#franz waxman#enormously fun mad doctor mayhem which is let down by a pervasive element of racist caricature in the middle section‚ as the action moves#to Africa and brings with it all the suffocating colonial baggage that you might expect from a 1936 film (but which is absolutely no less#disappointing for it). the beginning and end are brilliant tho; amazing laboratory sets‚ cool and inventive sci fi visuals‚ dark and stormy#nights. and of course we have our two horror titans to enjoy: Karloff wide eyed and tragic‚ Lugosi bearded and seductive...#there is more emotional heft and greater poignancy here than many of these films achieve‚ and some little individual moments of beauty#(Karloff's mother's reaction‚ after having her sight restored‚ to seeing her own hands for the first time in many years is quite special)#even Walter Kingsford's comic turn is entertaining and this would stand as one of the best universal uses of Lugosi and Karloff's talents#if only it weren't for that dispiriting and patronising depiction of the African locals in that middle section.. an unfortunate shadow cast#over a nearly brilliant example of Universal's 30s horror hodgepodges

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

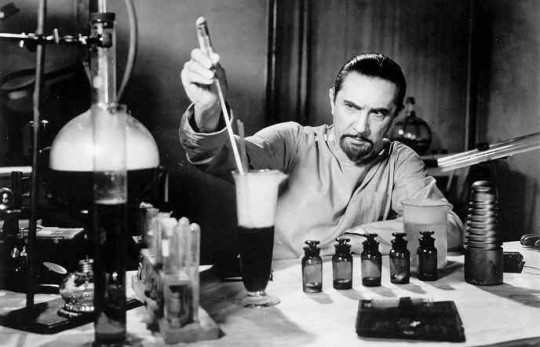

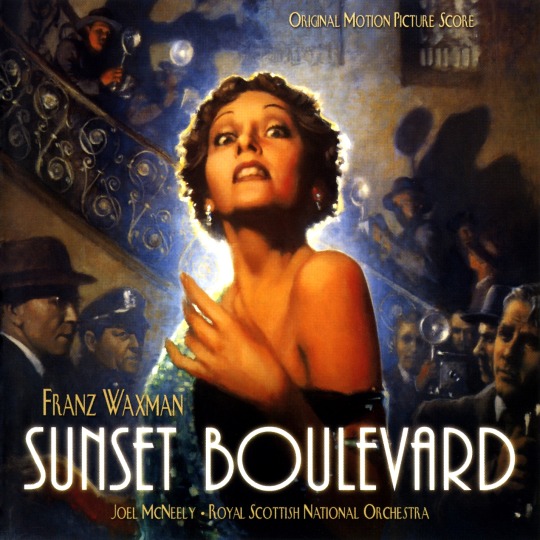

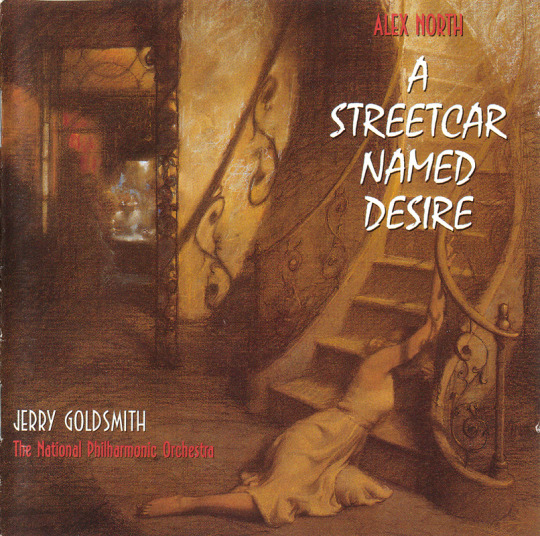

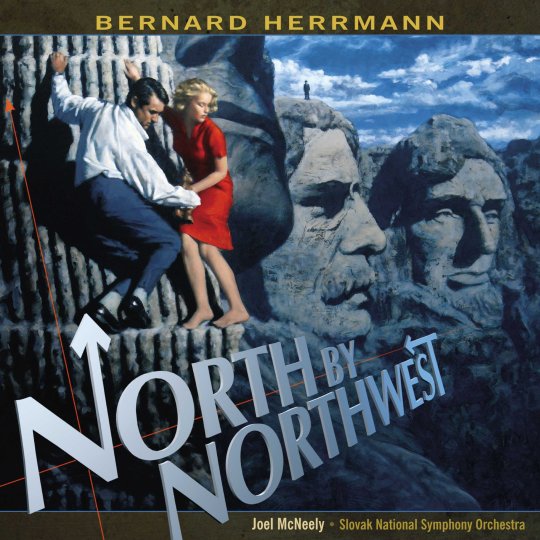

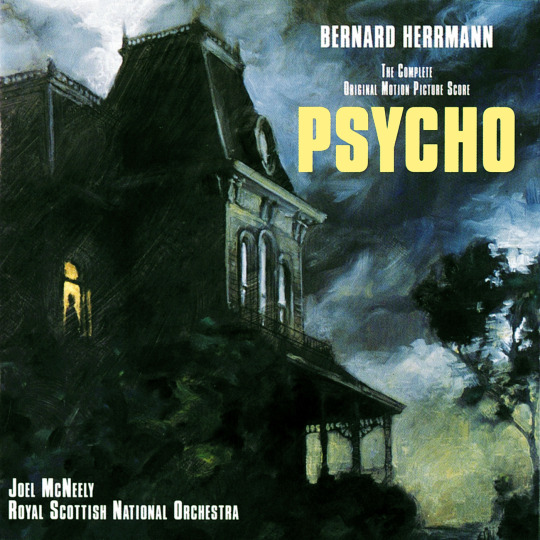

art by Matthew Peak for various film score re-recordings on the record label Varèse Sarabande (pt.1)

#matthew peak#Varèse Sarabande#joel mcneely#jerry goldsmith#bernard herrmann#franz waxman#alex north#also#these recordings are GREAT

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

If you're going to kill someone, do it simply.

Suspicion, Alfred Hitchcock (1941)

#Alfred Hitchcock#Samson Raphaelson#Joan Harrison#Alma Reville#Cary Grant#Joan Fontaine#Cedric Hardwicke#Nigel Bruce#May Whitty#Isabel Jeans#Heather Angel#Auriol Lee#Reginald Sheffield#Leo G. Carroll#Harry Stradling Sr.#Franz Waxman#William Hamilton#1941

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

McAttack

Ray McKenzie And His Orchestra: Count Basie’s And Duke Ellington’s Greatest Hits (1974) This is an lp to cd transfer of a double lp by this orchestra. In jazz this is a big band with several saxes, horns, piano etc & is not to be consumed with a symphony orchestra. These are decent interpretations of the hits. Nothing radical 🙂

On a genre hopping mp3 cd that runs too nearly 8 hours of music I…

View On WordPress

#am writing#Anita O&039;Day#Billy Preston#Franz Waxman#Gabor Szabo#Gary McFarland#homophobia#iTunes#jazz#Manu Dibango#mp3#music#Ontario#Peyton Place#photographs#Ray McKenzie#review#Soul Makossa#Soundtrack#Toronto

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Whiplash

The fact that S.Z. Sakall and Eve Arden are on hand to supply expert comic relief suggests that Warner Bros. actually expected the plot of Lew Seilers’ WHIPLASH (1948, TCM, YouTube) to be taken seriously. If they had cast poorer actors in the leads, it might now be considered high camp. Instead, it’s just silly and reminiscent of better film noirs. Artist Dane Clark falls for Alexis Smith while she’s vacationing on the Pacific. When she leaves abruptly, he follows her to New York, where he finds she’s married to a wheelchair-bound former boxer turned gangster (Zachary Scott). Scott takes a liking to Clark’s right hook and offers to sponsor him as a professional boxer, a job Clark takes simply to slut shame the woman he claims to love. Given his aggressive courting style — he keeps telling her what she wants — that doesn’t come as much of a surprise. Clark is an engaging personality who was brought to Warner Bros. as a threat to rebellious star John Garfield, and the film is clearly designed to cash in on the success of Garfield’s first independent production, BODY AND SOUL (1947). He manages to be both tough and vulnerable as required. Scott has less to work with. It’s his standard cad role, with the wheelchair the only difference. The real surprise, however, is Smith. Her face doesn’t move much, but her eyes are more alive than in many of her Warner’s films, and her line readings are impressive. She also gets the full glamour treatment from cinematographer Peverell Marley, complete with shots where the key light makes her eyes glow. He and Seiler also create some great film noir compositions. Franz Waxman did the evocative score. The film also features Jeffrey Lynn as Smith’s alcoholic brother, Alan Hale as Clark’s trainer, future Mouseketeer Jimmie Dodd as a pianist and Maudie Prickett as a nasty landlady who’s the butt of Arden’s jokes.

#film noir#dane clark#alexis smith#zachary scott#eve arden#s.a. sakall#jeffrey lynn#alan hale#jimmie dodd#maudie prickett#peverell marley#franz waxman

0 notes

Text

Viale del Tramonto

Franz Waxman (pseudonimo di Franz Wachsmann; 1906 - 24 febbraio 1967): Suite dalla colonna sonora del film Sunset Boulevard (1950) di Billy Wilder. Paramount Symphony Orchestra diretta dall’autore.

Main Title

Prelude [1:24]

Money Trouble – The Schwabadero [2:13]

Afternoon Outings – Sacrefice of Self-Respect [3:21]

After Auld Lang Syne – The Pampered Prince [7:06]

Interview With Demille…

youtube

View On WordPress

0 notes

Link

From Korngold, Steiner, and Herrmann to Greenwood, Levi, and Britell, here are my 70 all-time favorite original movie scores.

#bernard herrmann#jerry goldsmith#ennio morricone#franz waxman#miklos rosza#david raksin#elmer bernstein#john barry#jonny greenwood#mica levi

0 notes

Text

On Borrowed Time (1939)

As time marches on, certain names that were once synonymous with American drama lose their weight, even among film buffs. In the early twentieth century, the Barrymore siblings – Ethel, John, and Lionel – were celebrated on both Broadway and in Hollywood, each one making a successful transition from the silent era to synchronized sound. The eldest, Lionel, was born in 1878 and was a Hollywood elder statesman when he made 1939’s On Borrowed Time. Directed by Harold S. Bucquet and based on a 1938 play of the same name by Paul Osborn (itself based on a 1937 Lawrence Edward Watkin novel of the same name), On Borrowed Time is a star vehicle for the eldest Barrymore. By the late 1930s, Barrymore had broken his hip twice – never healing properly. As such, he remained wheelchair-bound for the remainder of his life. Physical disablement, even in modern Hollywood, often curtails acting careers. But Barrymore’s home studio, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM), often had their screenwriters find ways to incorporate Barrymore’s disability.

Lionel Barrymore was also in physical pain and depended on cocaine injections to work and sleep. However, this never affected his acting, as he delivers a wonderful lead performance in On Borrowed Time. Those less knowledgeable about this period in Hollywood history will probably only recognize his surname and the acting family he came from. Nowadays, most cinephiles probably only know of Lionel Barrymore through It’s a Wonderful Life (1946; Barrymore played the villainous Mr. Potter). Lionel Barrymore's role as the somewhat foul-mouthed but caring grandfather here offers something completely different.

Mr. Brink (Cedric Hardwicke) is hitchhiking somewhere near a small town in contemporary America. But he is not interested in riding with just anyone:

MAN IN CONVERTIBLE: May I give you a lift, sir?

MR. BRINK: Thank you, no. I have an appointment – a lady and gentleman.

MAN IN CONVERTIBLE: Oh, I’m sorry. [coughs] I thought you signaled me.

MR. BRINK: No. Not yet...

As you may have guessed, Mr. Brink is a personification of death. A few minutes later, he flags down that lady and gentleman and takes their lives in a car accident. That couple are the parents of John “Pud” Northrup (Bobs Watson; best known as Pee Wee in 1938’s Boys Town), who will now live solely under the care of Gramps and Granny (Barrymore and Beulah Bondi) and their housemaid Marcia (Una Merkel). At the memorial service for Pud’s parents, Gramps donates a substantial sum to the church. After learning of Gramps’ generosity, Pud exclaims that his grandfather doing such a good deed should allow him a wish. Gramps’ wish: as a deterrence local children stealing his apples, he wishes that anyone who climbs up his apple tree will be stuck there until he permits them down. Some time later, Mr. Brink arrives at Northrup grandparent homestead for an appointment with Gramps. Gramps tricks Mr. Brink up the apple tree, trapping him there – setting off a series of developments that put Gramps in a moral bind.

In a cast already headlined by character actors, how about some more? On Borrowed Time also features Henry Travers (the guardian angel Clarence in It’s a Wonderful Life) and Nat Pendleton as neighbors, Grant Mitchell as Gramps’ lawyer, James Burke as the sheriff, Charles Waldron as the reverend, and an uncredited Hans Conried (Captain Hook and Mr. Darling in 1953’s Peter Pan) as the man in the convertible.

Elsewhere, away from the camera, one can’t find much of composer Franz Waxman’s (1935’s Bride of Frankenstein, 1951’s A Place in the Sun) string-dominated score anywhere, but this is one of Waxman’s finest scores of his early career.

The opening half-hour of On Borrowed Time are its weakest. Hardwicke’s Mr. Brink has an eerily charismatic first impression that the scenes immediately following it cannot hope to match. Instead of learning more about the nature of Mr. Brink, the film instead shows us some of Pud’s misadventures and his relationship with his grandparents. Strangely, the loss of his parents seems to have had little effect on Pud at all, although his sadness seems to emerge in his contentious relationships with the other local boys and Aunt Demetria (Eily Malyon). Aunt Demetria, shortly after the Northrup parents’ deaths, hatches a scheme to assume guardianship of Pud and attain access to his considerable inheritance. Her designs are so obvious to all that when Gramps and Pud start calling her a “pismire” (literally, a pissing ant), Granny looks the other way when she might otherwise correct their boorish behavior. All of this takes longer to develop than it should (it does not help that Bobs Watson’s performance as Pud feels disjointed, but more on that shortly), even if the opening act primarily serves to show us how close Pud is to his grandparents. Even though we sense where the dramatic stakes are headed, On Borrowed Time almost seems to splinter into another film before we see Mr. Brink again.

In addition, contemporary reviews of On Borrowed Time lambasted screenwriters Alice D.G. Miller (1929’s The Bridge of San Luis Rey) and Frank O’Neill (no other film credits) for sanitizing the language from the original stage play due to the demands of the Hays Code (the self-censorship code that applied to major Hollywood studios from 1934-1968, repealed in favor of the current MPA ratings system). For the record, the text of the stage play was not freely available as I was writing this piece, so I have no means of comparison. Paul Osborn’s On Borrowed Time has only appeared on Broadway thrice: the 1938 original production and short-lived revivals in 1953 and 1991. The play had also been adapted for radio and television.

Compared to those film reviewers during the film’s 1939 release and many modern writers, I tend to be more forgiving if the Hays Code-enforced changes to a film do not significantly alter the spirit of the text. Sure, it would be funnier to hear disparaging language stronger than “pismire” in a 1939 film, but Pud’s and Gramps’ feelings towards Aunt Demetria, the apple-stealing boys, and Mr. Brink are comprehensible in this movie.

The closing two acts of On Borrowed Time draw its strengths from the performances and the narrative’s adoption of fairy tale logic (any film beginning with death flagging down folks he has an “appointment” with is almost always operating under the terms of the fantasy genre). In tandem, Lionel Barrymore and Bobs Watson’s good-humored and loving rapport lift the film above its structural flaws. Barrymore’s Gramps – an American Civil War and Spanish-American War veteran* – is a classic small town curmudgeon, only allowing his bitter exterior to crumble when Granny and Pud are around. Looking to protect Pud from Aunt Demetria, Gramps remains defiant towards the wills of Mr. Brink and the insistent neighbors. Perhaps it is not the greatest Lionel Barrymore performance, but he is always effective.

Bobs Watson, as Pud, is inconsistent anytime he does not share the scene with Barrymore. The explanation for his performance comes from Watson himself: “My dad was the one that really directed me, and I think some of the directors resented it a little bit… I trusted my dad implicitly, so I read the dialogue the way he told me.” His father’s influence results in occasionally overcooked line readings against director Harold S. Bucquet’s vision (MGM’s Dr. Kildare series, 1943’s The Adventures of Tartu), more theatrical than what the scene calls for. But when the scene calls for crying, by golly can Watson (who had a reputation for crying on cue) deliver. And his scenes with Barrymore are beautifully acted, convincingly showing the audience the love between grandson and grandfather.

Sir Cedric Hardwicke, a noted Shakespearean actor, cuts no corners as Mr. Brink. Mr. Brink is aware that, in time, he will keep all his appointments. Hardwicke plays Brink as slightly menacing, always dignified (no one expects that perfect an English accent in rural America), and somewhat aloof to what he probably thinks are childish trivialities and life’s mundane moments. He is the antagonist, but in no way is he the villain of this movie. That belongs to Eily Malyon as Aunt Demetria, a character some compare to Margaret Hamilton’s Mrs. Gulch/Wicked Witch from The Wizard of Oz (1939; released a little more than a month after On Borrowed Time) due to her temperament and unbending nature. One wishes the film made more use of the always-underappreciated Beulah Bondi as Granny (Bondi very often played elderly mothers and grandmothers, almost always appearing much older than she actually was), too.

Death and loss are two themes currently popular in modern cinema (see: a vast bulk of Pixar’s filmography, 2016’s Manchester by the Sea, 2019’s The Farewell, and a large selection of pieces from any film festival worldwide), but in the early decades of talkies in Hollywood, you would be hard-pressed to find films in which those themes were truly central, not secondary, to the narrative. And when those themes do appear, they appear in the context of fantasy films, like Death Takes a Holiday (1934) and On Borrowed Time. Anecdotally, I suspect the scarcity of major Hollywood movies revolving around death and loss is partly due to the realities of the 1930s and 1940s. Audiences, concerned with a worldwide Great Depression and soon a Second World War, did not seek films ruminating about death and loss and sought escapist fare instead. There was enough despair to go around.

The film that emerges on the back of these performances is thanks to its ability not to concentrate on the fantastical situation the Gramps and Pud find themselves in, but to raise the moral questions that Mr. Brink’s presence – and eventual entrapment – poses. Mr. Brink’s time in the tree results in consequences that Gramps and Pud could not imagine. Gramps’ decision to delay his death for the love of his grandson is concurrently noble and selfish. It is noble in respect to wanting the best for Pud, so that he may live life away from his aunt’s icy attitude and pernicious designs regarding her nephew’s inheritance. But it is selfish in that, as Gramps learns, that Brink’s inability to make any appointments unless he comes down from the apple tree means that almost no living being can die (for spoiler reasons, I am not listing the exceptions here) – even the ones in physical pain. How is Gramps supposed to navigate this situation, in addition to the communal and legal pressures from his neighbors and the police?

A resolution comes abruptly, in a way that devastates Gramps (but would probably make the Brothers Grimm nod in appreciation). On Borrowed Time’s bittersweet ending is deserved, and – as long as the viewer accepts the film’s fantastical premise and rules – will play quite differently for audiences of different ages.

Lionel Barrymore had two daughters with Doris Rankin, his first wife. Barrymore and Rankin lost both daughters in their infancies; neither ever truly recovered from their losses. One wonders what Barrymore thought while making On Borrowed Time, a film that argues for one coming to terms with death, however unfair or untimely its arrival. For a 1939 release (a legendarily glorious year for American cinema), positioning such ideas as the film’s narrative keystone ensures On Borrowed Time a unique spot in the early years of Hollywood’s Golden Age.

My rating: 8/10

^ Based on my personal imdb rating. My interpretation of that ratings system can be found in the “Ratings system” page on my blog. Half-points are always rounded down.

* Gramps describes himself as having fought for the Union. This might make Gramps close to ninety years old, give or take, if we are to believe the film’s self-professed setting!

For more of my reviews tagged “My Movie Odyssey”, check out the tag of the same name on my blog.

NOTE: This is the 800th full-length Movie Odyssey review I have published on tumblr.

#On Borrowed Time#Harold S. Bucquet#Lionel Barrymore#Beulah Bondi#Cedric Hardwicke#Bobs Watson#Una Merkel#Nat Pendleton#Henry Travers#Grant Mitchell#Eily Malyon#James Burke#Charles Waldron#Alice D.G. Miller#Frank O'Neill#Lawrence Edward Watkin#Paul Osborn#Franz Waxman#TCM#My Movie Odyssey

0 notes

Text

Franz Waxman composing the MGM Fanfare in 1936

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Franz Waxman

Alles Gute zum Geburtstag, film composer Franz Wachsmann (Waxman)!

youtube

0 notes

Text

youtube

Lots of little instrumentation details in this! Double snares, double timpani, bass drum holding a bells belt in their other hand. (Of course, the double timps might be a holdover from an earlier piece, as I don't see two sets in a studio recording, and there are double pianos on stage which aren't used for this.)

(For potential link rot purposes, this is the John Wilson Orchestra doing The Ride of the Cossacks from Taras Bulba at the 2013 Proms)

0 notes

Photo

Klatsch, Tratsch Heuchelei und üble Nachrede prägen den an sich beschaulich, prüde und gesittet wirkenden neuenglischen Weiler Peyton Place, aber hinter den malerischen Fassaden, da geht es zu: Sex, Gewalt, Unzucht, Ungerechtigkeit, Verlangen, Trunksucht,Vergewaltigung, Mord und Totschlag... Über die wirklichen Probleme spricht dann auch keiner. Heuchler allesamt! Dabei könnte es mit ein bisschen Verständnis für menschliche Bedürfnisse so schön sein. Und dann bricht auch noch der Krieg aus! Für so ein ...naja-De-Luxe-Color-Melodram (Mit Waxman-Score!) ist es alles recht explizit, obwohl dann, verglichen mit dem supererfolgreichen Skandal-Roman, auf dem es basiert, es wieder recht handzahm sei, so eine gängige Beschwerde.

#Peyton Place#Lana Turner#Hope Lange#Lee Philips#Lloyd Nolan#Diane Varsi#Arthur Kennedy#Russ Tamblyn#Film gesehen#Mark Robson#Franz Waxman

0 notes

Photo

- I want you to get rid of all these things.

- But these are Mrs. de Winter's things.

- I am Mrs. de Winter now!

Rebecca, Alfred Hitchcock (1940)

#Alfred Hitchcock#Robert E. Sherwood#Joan Harrison#Joan Fontaine#Laurence Olivier#George Sanders#Judith Anderson#Nigel Bruce#Reginald Denny#C. Aubrey Smith#Gladys Cooper#George Barnes#Franz Waxman#W. Donn Hayes#1940

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Furies

If all Westerns looked like John Ford’s or Anthony Mann’s, I think I’d be a much bigger fan of the genre. Of course, it’s almost unfair to call Mann’s THE FURIES (1950, Criterion Channel, YouTube) a Western. It’s more of an anti-Western. It features the same conflict as in most of the genre — the frontier vs. civilization — but in this case civilization is represented not by home, family and the feminine but rather by business interests, particularly banks. And as shot by Victor Milner, the wide-open spaces are more oppressive than liberating. These characters don’t need railroads and cities and farms to fence them in. They’re already confined by their own twisted passions. Walter Huston is the tyrannical, mercurial owner of a ranch called The Furies. He’s Lear on horseback. He plans to leave everything to his tough, adoring daughter (Barbara Stanwyck) as long as he can control her life, including whomever she might marry. Then he comes home from a business trip with a wealthy widow (Judith Anderson) out to take Stanwyck’s place, and the fur and the scissors fly. Charles Schnee adapted the script from a Niven Busch novel, and at the start it has the meandering quality of a lot of fiction. You can’t quite tell where the story’s going, but the characters and atmosphere are so rich it doesn’t matter. And when you get to see Huston (in his last film) and Stanwyck interact, who needs a plot. There’s a terrific score by Franz Waxman and wonderful supporting work from Anderson, Gilbert Roland, Thomas Gomez, Blanche Yurka and Beulah Bondi, who’s barely on screen five minutes yet manages to capture her character simply in the way she transfers her fan from one hand to the other. Censorship imposed a certain racism on the film. Where Stanwyck and Roland had an affair in the novel and even married, that was turned into a friendship and Roland’s unrequited love, because his character, a Mexican, couldn’t be intimate with a white woman. And then there’s Wendell Corey. He’s better than in a lot of his leading roles, but he hardly seems magnetic enough to capture Stanwyck’s passions. And the character, as written for the screen, doesn’t make a lot of sense. He uses Stanwyck at first and then suddenly falls in love with her. Nor does it help that he has a misguidedly chauvinistic proposal scene: “And don’t ask me to be your husband. If we marry, remember one thing. You’ll be my wife. Whenever you’re wrong, I’ll tell you so. If I’m ever wrong, you just keep your little mouth shut.” Would anybody ever believe he could exercise that kind of control over a Barbara Stanwyck? Or a Barbara Hale? Or even a Barbara Pepper?

#anthony mann#barbara stanwyck#walter huston#judith anderson#gilbert roland#blanche yurka#beulah bondi#thomas gomez#franz waxman#western noir#western#film noir#wendell corey

0 notes