#Congress of Racial Equality (Core)

Text

On May 20, 1961, Freedom Riders traveling by bus through the South to challenge segregation laws were brutally attacked by a white mob at the Greyhound Station in downtown Montgomery, Alabama.

Several days before, on May 16, the Riders faced mob violence in Birmingham so serious that it threatened to prematurely end their campaign. The Freedom Riders were initially organized by the Congress on Racial Equality (CORE), but after the Birmingham attacks, an interracial group of 22 Tennessee college students, known as the Nashville Student Movement, volunteered to take over and continue the ride through Alabama and Mississippi to New Orleans.

These new Freedom Riders reached Birmingham on May 17 but were immediately arrested and returned to Tennessee by Birmingham police. Undeterred, the Riders and additional reinforcements from Tennessee returned to Birmingham on May 18. Under pressure from the federal government, Alabama Governor John Patterson agreed to authorize state and city police to protect the Riders during their journey from Birmingham to Montgomery.

At Montgomery city limits, state police abandoned the Riders' bus; the Riders continued to the bus station unescorted and found no police protection waiting when they arrived. Montgomery Public Safety Commissioner L.B. Sullivan had promised the Ku Klux Klan several minutes to attack the Riders without police interference, and, upon arrival, the Riders were met by a mob of several hundred angry white people armed with baseball bats, hammers, and pipes.

Montgomery police watched as the mob first attacked reporters and then turned on the Riders. Several were seriously injured, including a college student named Jim Zwerg and future U.S. Congressman John Lewis. John Seigenthaler, an aide to Attorney General Robert Kennedy, was knocked unconscious. Ignored by ambulances, two injured Riders were saved by good Samaritans who transported them to nearby hospitals.

#May 20 1961#1961#history#white history#us history#republicans#black history#Freedom Riders#civil rights#Birmingham#Jim Zwerg#Congress on Racial Equality#CORE#police#police cowardice#bad police#police brutality#cops#bad cops#dirty cops#Ku Klux Klan#KKK#jumblr#am yisrael chai

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Philadelphia, Neshoba County, Mississippi, June 21, 1964

James Chaney (May 30, 1943 – June 21, 1964)

Andrew Goodman (November 23, 1943 – June 21, 1964)

Michael Schwerner (November 6, 1939 – June 21, 1964)

(image: The «CORE-Lator», No. 107, (page 1), Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), New York, NY, July-August 1964 (pdf here). Civil Rights Movement Archive)

#graphic design#pamphlet#newsletter#james chaney#andrew goodman#michael schwerner#core lator#core#congress of racial equality#civil rights movement archive#1960s

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

👊🏾✊🏾 “When you see something that is not right, not fair, not just, you have to speak up. You have to say something; you have to do something.” ~ Congressman John Lewis (1940-2020) 🇺🇸

#John Lewis#Congressman John Lewis#civil rights activist#United States House of Representatives#United States Congress#5th congressional district of Georgia#Civil Rights Movement#the sixties#the sit in movement#Freedom Rides#Freedom Riders#1963 March on Washington#1965 Selma to Montgomery marches#1965 Bloody Sunday#sncc#Martin Luther King Jr#Fisk University#nonviolence#Congress of Racial Equality (Core)#SRC and VEP#March 2013#John Lewis: Good Trouble#Bobby Kennedy for President#King In The Wilderness#historical caricature#Black History Month

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

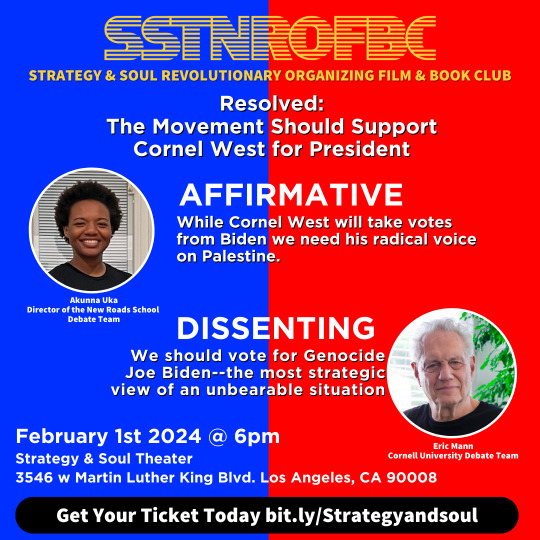

Strategy & Soul Film & Book Club Thursday @ 6pm Debate Topic: Presidential Election 2024 Read more inside...

Strategy & Soul Film & Book Club Thursday @ 6pm Debate Topic: Presidential Election 2024 Read more inside...

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Resolved: The Movement Should Support Cornel West for President

[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_single_image image=”7455″ img_size=”300×300″ alignment=”right”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_column_text css=”.vc_custom_1706722947634{margin-bottom: 0px !important;}”]

Affirmative

While Cornel West will take votes…

View On WordPress

#Akunna Uka#Congress of Racial Equality#CORE#Cornell West#Denzel Washington#Eric Mann#Forest Whitaker#HBCU#James Farmer#Jurnee Smollett#Labor Community Strategy Center#Melvin B Tolson#Revolutionary Organizing#Strategy and Soul#Strategy and Soul event#Strategy and Soul Film and Book Club#Strategy And Soul theater#The Great Debaters#The Strategy Center#Wiley College

0 notes

Photo

On this day, 21 June 1964, three civil rights workers were murdered by police and Ku Klux Klan members in Mississippi. James Earl Chaney, a 21-year-old Black former union-plasterer and organiser with the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) from nearby Meridian, Mississippi, Andrew Goodman (pictured bottom, left), a 20-year-old Jewish anthropology student from New York, and Michael 'Mickey' Schwerner, a 24-year-old Jewish CORE organiser and former social worker from New York were lynched on the night of June 21–22 by members of the Mississippi White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, the Neshoba County's Sheriff Office and the Philadelphia Police Department located in Philadelphia, Mississippi. The three had been working on the "Freedom Summer" campaign, attempting to register Black people to vote. While seven of the killers ended up being jailed on federal charges of civil rights violations, the state of Mississippi didn't prosecute anyone for the murders until 2005, when they eventually charged one of the killers with manslaughter. He was then convicted and sentenced to 60 years imprisonment. Chaney's younger brother Ben later joined the Black Panther Party and the urban guerrilla group the Black Liberation Army, for which he ended up serving 13 years in prison. For this and hundreds of other stories, get hold of a copy of our first book: https://shop.workingclasshistory.com/products/working-class-history-everyday-acts-resistance-rebellion-book https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=648220290684523&set=a.602588028581083&type=3

179 notes

·

View notes

Text

Danny Lyon Congress of Racial Equality Member Bernie Sanders (center) and Other CORE Members Taking Part in a Civil Rights Sit-in, University of Chicago, Chicago, Il Jan, 1962

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

On this day, remembering James Baldwin

Happy Heavenly Birthday to the profound, brilliant author and activist Mr. James Arthur Baldwin!

James Arthur Baldwin was a novelist, essayist, playwright, poet, and social critic.

Baldwin's essays, such as the collection Notes of a Native Son (1955), explore palpable yet unspoken intricacies of racial, sexual, and class distinctions in Western societies, most notably in mid-20th-century America, and their inevitable if unnameable tensions.

Some Baldwin essays are book-length, for instance The Fire Next Time (1963), No Name in the Street (1972), and The Devil Finds Work (1976).

His novels and plays fictionalize fundamental personal questions and dilemmas amid complex social and psychological pressures thwarting the equitable integration of not only blacks, but also gay men—depicting as well some internalized impediments to such individuals' quest for acceptance—namely in his second novel, Giovanni's Room (1956), written well before gay equality was widely espoused in America.

Baldwin's best-known novel is his first, Go Tell It on the Mountain (1953).

SOCIAL & POLITICAL ACTIVISM:

He wrote about the movement, Baldwin aligned himself with the ideals of the Congress of Equality (CORE) and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee(SNCC). In 1963 he conducted a lecture tour of the South for CORE, traveling to locations like Durham and Greensboro, North Carolina and New Orleans, Louisiana. During the tour, he lectured to students, white liberals, and anyone else listening about his racial ideology, an ideological position between the "muscular approach" of Malcolm X and the nonviolent program of Martin Luther King Jr..

By the Spring of 1963, Baldwin had become so much a spokesman for the Civil Rights Movement that for its May 17 issue on the turmoil in Birmingham, Alabama, Time magazine put James Baldwin on the cover. "There is not another writer," said Time, "who expresses with such poignancy and abrasiveness the dark realities of the racial ferment in North and South."

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

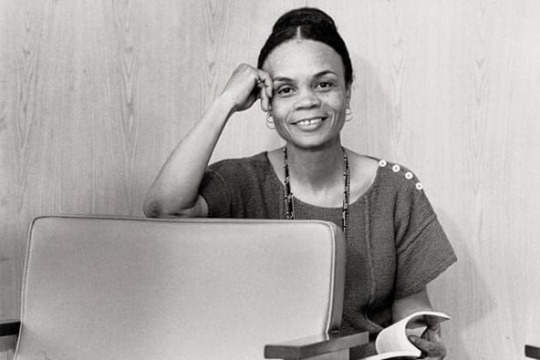

“Sonia Sanchez was born Wilsonia Benita Driver in Birmingham, Alabama. After her mother’s death in 1935 she lived with her grandmother. Her grandmother taught her to read at age four and write at age six. When her grandmother passed away in 1943, she moved to Harlem, New York where she stayed with her father Wilson Driver.

Driver attended Hunter College in New York City where she took creative writing courses although she graduated with a B.A. in Political Science in 1955. Continuing her education at New York University, Driver focused on the study of poetry. She also married and divorced Puerto Rican immigrant Albert Sanchez, although she retained his surname. She later married poet Etheridge Knight and together they had three children. They would later divorce.

In 1965 Sanchez taught at San Francisco State University. The course she offered at San Francisco State in 1966 on the literature of African Americans is generally considered the first of its kind taught at a predominately white university.

Sonia Sanchez released her first collection of poetry in 1969 entitled Homecoming. Her poetry was described at experimental and innovative; Sanchez was the first to blend the musical elements of the blues with the haiku and tanka poetry styles. She tackled many genres of literary art such as writing children’s books, and plays. Sanchez is most famous for her Spoken Word poetry books. She was awarded the American Book Award in 1985 for one of her best-known books, Home girls and Hand grenades.

Sanchez was a major influence in the Black Arts and Civil Rights Movements of the 1960s. She was an active member in the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) as well as the Nation of Islam. She was inspired when she met Malcolm X and used his vernacular in some of her poems. She left the Nation of Islam after three years of affiliation in protest of their mistreatment of women. She continues to advocate for the rights of oppressed women and minority groups.

Sanchez has received countless awards for her work including the P.E.N. Writing Award (1969), the National Academy of Arts Award (1978), and the National Education Association Award (1977-1988). She has guest lectured in over 500 colleges and universities. Her poetry has been heard worldwide in Africa, Australia, Canada, the Caribbean Islands, China, Cuba, Europe, and Nicaragua. Sanchez’s last faculty appointment was at Temple University in Philadelphia where she was the first Presidential Fellow at that institution and the first to hold the Laura Carnell Chair. Sanchez taught courses in English and Women’s Studies until her retirement in 1999.”

Ms. Sanchez now resides in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

MOGAI BHM- Belated Day 19!

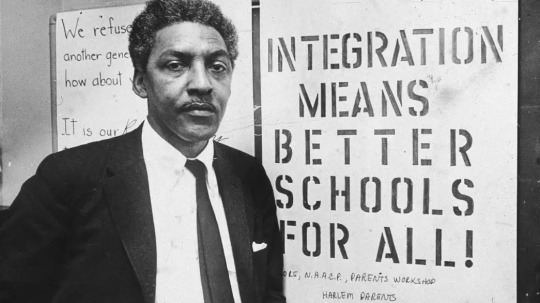

happy BHM! today i’m going to be talking about Bayard Rustin!

Bayard Rustin-

[Image ID: A black-and-white photograph of Bayard Rustin, a thin Black man with slightly greying, short frizzy hair. In the photo, he has a deadpan expression on his face and is wearing a black necktie, a white collared undershirt, and a black suit jacket. He is standing by a sign on a wall that says in large block text “INTEGRATION MEANS BETTER SCHOOLS FOR ALL!”. Below that, in small scribbled print, it says “N.A.A.C.P, PARENTS WORKSHOP HARLEM PARENTS”. There is another, smaller sign behind Rustin that is partially obscured by him, but what can be seen of it says “We refuse... another gene... how about... It is our...”. End ID.]

Bayard Rustin, a man who is frequently considered to have been Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s “right-hand man”, is a civil rights activist who has been largely erased from the Black history taught in schools, and from the general population’s knowledge and perception of the Civil Rights Movement- but he was an integral part of the movement, and his erasure has largely to do with the fact that he was openly and unapologetically gay.

Bayard Rustin was born in 1912 in Pennsylvania, where he was raised by a Quaker family who very early on instilled in him the principles of nonviolence, which laid the foundation for his involvement with the civil rights movement. At a young age, he was interested in civil rights and racial justice, and at first, the racially progressive views of the Young Communist League attracted him to join. Eventually, their politics changed and he left the league.

In 1941, he turned his sights to socialism by joining the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR), who at the time advocated for equal rights for all people (except, as he would later find out, gay people). That same year, he met two other men who would be influential in his life- A.J Muste, the leader of the FOR, and Phillip A. Randolph. With these two men, he helped propose the March on Washington that convinced FDR to sign the executive order that allowed Black workers into the defense industry, and in 1944, Bayard Rustin was arrested as a “conscientious objector” because he refused to sign up for the draft for WWII, to which he was staunchly opposed.

However, in 1953, Bayard was fired from his position in the FOR after being arrested and charged with “sex perversion” for having sex with another man. At the time, many people feared that open discussions of homosexuality would threaten the image and therefore ultimately the credibility and impact of the civil rights movement, so Bayard, along with many other Black queer people, were often targeted for their identities, either being forced to hide them or be careful with them, or having their identities completely used against them to disparage their credibility within the movement.

During the late 1940s, Bayard Rustin helped to co-found the Congress of Racial Equality, or CORE, which became one of the most central civil rights organizations in the civil rights movement. In 1947, he participated in FOR’s “Journey of Reconciliation” (discussed more in this post) which provided the blueprint for the Freedom Rides of the 1960s, which led to the illegalization of interstate bus segregation.

In 1956, Randolph, who had become Rustin’s mentor, urged him to meet with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. amidst the Montgomery Bus Boycott. When Rustin agreed, he and several other key pacifists of the movement met with King and were instrumental in convincing him to more fully adopt nonviolence as a way of life. Bayard Rustin’s upbringing in nonviolence led to it being one of the cornerstones of the civil rights movement.

Over the next couple of years, Bayard became part of King’s “inner circle” of close associates within the civil rights movement. He held a key position in King’s organization, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, which he had helped to found, and he was behind many efforts of integration. He helped to organize many key events, like the Prayer Pilgrimage for Freedom, and the Youth Marches for Integrated Schools. However, in 1960, he reluctantly agreed to step away from the SCLC and from Dr. King, because the Democratic Convention threatened to publish a rumor that King and Rustin were romantically and sexually involved, using Bayard’s orientation against him, if they followed through with a protest against the convention that they’d been planning. Bayard himself was very disappointed with the way King didn’t stand up for him, but he also acknowledged that it was probably best for the movement that he step away.

In the following years, he got involved outside of the scope of the SCLC. He did community organizing, and eventually, in 1963, he was reintegrated into King’s campaign through the Birmingham Campaign. It was then that he made his most notable and significant contribution to the Civil Rights Movement. He had strong organizational and strategic skills, and people who worked with him knew that there was no better man to re-energize the movement through a strategic march, than Rustin- and thus began the plan that brought to fruition Bayard’s previous plans of a march on Washington.

Many people involved were still against Bayard being involved- including John Lewis, a prominent member of the SNCC, and Roy Wilkins, a prominent chair of the NAACP. Their reservations were largely against both his sexuality and his previous communist affiliations, so it was agreed that instead, his mentor, Philip A. Randolph, would be elected to lead the march, so that he could then, in secret, choose his mentee, Bayard Rustin, to lead the march from behind the scenes.

So, within a time span of eight weeks, Bayard Rustin organized the infamous 1963 March on Washington. He spent those weeks incessantly writing letters and organizing with others. It was an extremely chaotic environment, but he was very focused and determined, and when the march happened, it singlehandedly re-energized the Civil Rights Movement and is remembered to this day as a monumental moment from the movement. From it, King’s famous “I Have A Dream” speech was born. Thanks to Rustin’s tireless efforts, the movement regained a lot of steam.

After that point in time, more people, including King himself, began to come out in support of Rustin, causing the accusations against him to lessen their effectiveness, although many within the movement were still against his involvement. For the rest of his life, Bayard Rustin remained a committed part of the Civil Rights Movement, and his contributions cannot be overstated. He was a proud gay Black man and he fought for his rights in the face of adversity from every angle.

tagging @metalheadsforblacklivesmatter @bfpnola @intersexfairy @cistematicchaos

Sources-

https://www.history.com/news/bayard-rustin-march-on-washington-openly-gay-mlk#:~:text=Why%20MLK's%20Right%2DHand%20Man,...and%20openly%20gay.&text=Jun%201%2C%202018-,Bayard%20Rustin%20was%20an%20indispensable%20force%20behind%20the%20Civil,...and%20openly%20gay.

https://kinginstitute.stanford.edu/encyclopedia/rustin-bayard

https://www.history101.com/bayard-rustin-mlk-right-hand/

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Congress of Racial Equality founded March 1942 pioneered direct nonviolent action in the 1940s before playing a major part in the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s. Founded by an interracial group of pacifists at the University of Chicago, CORE used nonviolent tactics to challenge segregation in Northern cities during the 1940s. Members staged sit-ins at Chicago area restaurants and challenged restrictive housing covenants. Expansion beyond the University of Chicago brought students from across the Midwest into the organization, and whites made up a majority of the membership into the early 1960s.

Civil rights activists from other organizations used CORE’s nonviolent tactics during the Montgomery Bus Boycott, CORE did not establish a presence in the South until 1957. CORE orchestrated or participated in some of the civil rights movement’s most iconic struggles. CORE’s national director, James Farmer, Jr., organized the Freedom Rides to test a recent SCOTUS decision integrating interstate buses and stations. Seven black and six white volunteers met staggering violence as they rode buses through the Deep South.

CORE cosponsored the March on Washington. CORE volunteers participated in Freedom Summer, a project that brought white Northerners to Mississippi to register Black voters. With the help of local police, Ku Klux Klansmen in Philadelphia, Mississippi killed three CORE volunteers at the beginning of the summer. Two of the victims were white, and the incident gained national attention and led to an increased federal presence in Mississippi. Violence continued, and tensions ran high between white and Black volunteers.

In 1966 CORE chose a new, more militant leader in Floyd McKissick. The group initiated short-lived programs to fight poverty. CORE barred whites from membership and chose Roy Innis as its national director. He advocated Black entrepreneurship. He moved CORE out of the mainstream of civil rights organizations, opposing busing and supporting welfare reform. He supported judicial nominees that mainstream civil rights groups opposed, including Robert Bork and Clarence Thomas. #africanhistory365 #africanexcellence

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

CHRONOLOGY OF AMERICAN RACE RIOTS AND RACIAL VIOLENCE p.3

1911

National Urban League founded.

1914

Marcus Garvey establishes the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA).

November William Monroe Trotter confronts Woodrow Wilson in the White House over the president’s support for segregation in federal offices.

1915

Debut of the D.W. Griffith film, The Birth of a Nation.

Failure of African American lawsuit against the U.S. Treasury Department for compensation for labor rendered under slavery.

CHRONOLOGY OF AMERICAN RACE RIOTS AND RACIAL VIOLENCE lvii

November William J. Simmons refounds the Ku Klux Klan at Stone Mountain in Georgia.

1916

Madison Grant publishes The Passing of the Great Race, detailing his drastic prescription—including eugenics—to save the white race from being overwhelmed by ‘‘darker races.’’

May Jesse Washington, a seventeen-year-old illiterate black farm hand, is lynched in Waco, Texas.

1917

May–July East St. Louis, Illinois, riots.

August Houston, Texas, mutiny of black soldiers at Camp Logan.

1918

After protesting the lynching of her husband, Mary Turner, then eight months pregnant, is herself brutally lynched in Valdosta, Georgia.

April Congressman Leonidas C. Dyer of Missouri introduces an anti-lynching bill into Congress (the Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill is defeated in 1922).

July Chester and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, riots.

1919

NAACP publishes Thirty Years of Lynching in the United States: 1889–1918 by Martha Gruening and Helen Boardman.

May Charleston, South Carolina, riot.

Summer Known as ‘‘Red Summer’’ because of the great number of people killed in various race riots around the country.

July Longview, Texas, riot.

Publication of Claude McKay’s sonnet, ‘‘If We Must Die.’’

Chicago, Illinois, riot.

Washington, D.C., riot.

August Knoxville, Tennessee, riot.

September Omaha, Nebraska, riot.

September–

October

Elaine, Arkansas, riot.

1920

Founding of the Commission on Interracial Cooperation, a major interracial reform organization in the South.

1921

April Tulsa, Oklahoma, riot.

1922

Anti-Lynching Crusaders are formed to educate Americans about lynching and work for its elimination.

Chicago Commission on Race Relations issues its influential report on the 1919

Chicago riots.

lviii CHRONOLOGY OF AMERICAN RACE RIOTS AND RACIAL VIOLENCE

1923

January Rosewood, Florida, riot.

February U.S. Supreme Court decision in Moore v. Dempsey leads to eventual release of

twelve African Americans in Arkansas who were convicted in perfunctory mobdominated trials of killing five whites during the Elaine, Arkansas, riots of 1919.

1929

Publication of Walter White’s Rope and Faggot: A Biography of Judge Lynch.

1930

Nation of Islam (Black Muslims) is founded in Detroit, Michigan, by W.D. Fard.

Formation of the Association of Southern Women for the Prevention of Lynching, the first organization of white women opposed to lynching.

October Sainte Genevieve, Missouri, riot.

1931

Scottsboro Case occurs in Alabama; the case comprises a series of trials arising outof allegations that nine African American youths raped two white girls in Scottsboro,

Alabama.

1932

Supreme Court renders a decision in Powell v. Alabama, a case related to the Scottsboro, Alabama, incident of 1931.

1934

Elijah Muhammad assumes leadership of the Nation of Islam.

1935

March Harlem, New York, riot.

1936

First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt addresses the annual conventions of both the NAACP and National Urban League.

1939

Billie Holiday’s first performance of the anti-lynching song Strange Fruit occurs at Cafe´ Society, New York’s only integrated nightclub.

1941

Supreme Court decision in Mitchell v. United States spurs integration of first-class railway carriages.

1942

Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) is founded as the Committee of Racial Equality.

February Double V Campaign is launched to popularize the idea that blacks should fight for

freedom abroad to win freedom at home.

1943

May Mobile, Alabama, riot.

June Beaumont, Texas, riot.

June ‘‘Zoot Suit’’ riots in Los Angeles, California.

July Detroit, Michigan, riot.

August New York City (Harlem) riot.

1944

Publication of Karl Gunnar Myrdal’s An American Dilemma: The Negro Problem and Modern Democracy.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

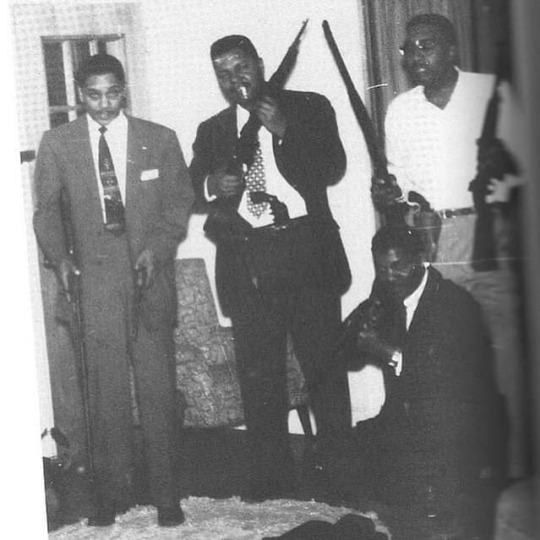

The Deacons for Defense and Justice was an armed self-defense African-American civil rights organization in the U.S. Southern states during the 1960s. Historically, the organization practiced self-defense methods in the face of racist oppression that was carried out under the Jim Crow Laws by local/state government officials and racist vigilantes. Many times the Deacons are not written about or cited when speaking of the Civil Rights Movement because their agenda of self-defense - in this case, using violence, if necessary - did not fit the image of strict non-violence that leaders such as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. espoused.

On July 10, 1964, a group of African American men in Jonesboro, Louisiana led by Earnest “Chilly Willy” Thomas and Frederick Douglas Kirkpatrick founded the group known as The Deacons for Defense and Justice to protect members of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) against Ku Klux Klan violence. Most of the “Deacons” were veterans of World War II and the Korean War. The Jonesboro chapter organized its first affiliate chapter in nearby Bogalusa, Louisiana led by Charles Sims, A.Z. Young and Robert Hicks. Eventually they organized a third chapter in Louisiana. The Deacons tense confrontation with the Klan in Bogalusa was crucial in forcing the federal government to intervene on behalf of the local African American community. The national attention they garnered also persuaded state and national officials to initiate efforts to neutralize the Klan in that area of the Deep South.

The Deacons emerged as one of the first visible self-defense forces in the South and as such represented a new face of the civil rights movement. Traditional civil rights organizations remained silent on them or repudiated their activities. They were effective however in providing protection for local African Americans who sought to register to vote and for white and black civil rights workers in the area. The Deacons, for example, provided security for the 1966 March Against Fear from Memphis to Jackson, Mississippi.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

"True emancipation lies in the acceptance of the whole past in deriving strength from all of my roots, in facing up to the degradation as well as the dignity of my ancestors."

As we come to the end of Pride Month 2023, I wanted to devote a little time to the remarkable life of Rev. Anna Pauline "Pauli" Murray --civil rights attorney, Episcopal priest, scholar, and advocate. Born in 1910 Baltimore, their mother tragically died when Murray was only four, and their father succumbed to depression and was later murdered in a mental hospital, and so Murray was raised by an aunt and grandparents, in a time when the threat of violence from the Ku Klux Klan was never too far away. Murray later moved to New York City and graduated from Hunter College in 1933 (as Columbia College did not at the time admit women). Throughout the 1930's Murray grappled with sexual and gender identity --this is in fact when they took on the preferred male-identifying name of "Pauli." A gifted photographer but an even more prolific author, Murray worked as a teacher with the New York City Remedial Reading Project, which offered a great deal of opportunity to write and publish. Among other publications, Pauli's essays and articles about civil rights would regularly appear in The Crisis and in Common Sense (both publications of the NAACP).

Pauli took the unusual (and risky!) step of petitioning to apply to graduate school at the University of North Carolina (current events alert!) --at the time an all-white institution. Such a prospect was considered sufficiently unobtainable that even the NAACP declined to actively support this effort. Pauli had in the meantime cultivated the acquaintance of then-First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, as well as A. Philip Randolph (see Lesson #68 in this series); associations which would later carry consequences. Pauli is listed as one of the founders of CORE (Congress of Racial Equality), along with Bayard Rustin (see Lesson #5 in this series), and James Farmer (Lesson #17). In 1943 they published a hugely important essay: "Negroes Are Fed Up;" and also a poem, Dark Testament, both of which spoke to the Harlem Race Riot of 1935.

In 1944 Murray graduated from Howard University Law School --while largely identifying as a man but still presenting as a woman, Murray famously coined the expression "Jane Crow" to describe the experience. They then applied to Harvard Law for an advanced degree on a Rosenwald Fellowship but was turned down --reportedly not due to racism (exact same current events alert!) but definitely due to sexism. They instead opted for the University of California Boalt School of Law; their graduate thesis was titled "The Right to Equal Opportunity in Employment." In 1945 Murray was named deputy attorney general for the state of California; the first African American to hold that post. In 1951 Pauli published States' Laws On Race and Color, a book that would later be described by Thurgood Marshall as the "Bible" for civil rights litigation, and was conspicuously referenced during Brown v. Board of Education arguments.

In 1952 the scourge of McCarthyism caught up with Murray and cost them a number of prestigious posts due to affiliation with "radicals" like Marshall, Randolph, and particularly Ms. Roosevelt. Unbowed, Pauli went on to publish the gripping biographical account Proud Shoes, which led in turn to a job offer in the litigation dept. of Paul, Weiss, Rifkin, Wharton, and Garrison (as in, Lloyd), where she would meet lifelong partner Irene Barlow. In 1960 Pauli was appointed by President John F. Kennedy to the Committee on Civil And Political Rights, but the issue of intersectionality was never far from their priorities; notably in 1963 Murray took Bayard Rustin, A. Philip Randolph, and Martin Luther King to task for not including a single woman speaker at the March On Washington. Perhaps the most fascinating coda to this remarkable life comes in 1977, when in the wake of Irene Barlow's passing, Murray became the very first African-American woman Episcopal priest. Pauli died in 1985, having never come out publicly.

For a comprehensive listing of Pauli's writings, visit the Pauli Murray Center for History and Social Justice: https://www.paulimurraycenter.com/paulis-writing

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

“I became involved in a lot of human rights activities, which all stemmed from my sexual orientation as much as anything.”

Kiyoshi Kuromiya was a true hero who devoted his life to the struggle for social justice. Whether it’s was for civil right for Black Americans, the injustice of the Viet Nam War, Gay Rights, or effective treatment for people with AIDS - Kuromiya was there fighting for the cause.

Perhaps Kuromiya passion to fight oppression stems from the fact he was born at the World War II–era Japanese American internment camp (Heart Mountain, Wyoming).

At a very young age, Kuromiya was aware he was homosexual, although he didn’t know the term for it. At the age of 9 he found a copy of The Kinsey’s report on sexual behavior on open shelves in Public Library. It explain his nature to him. He soon “came out” to his parents. But later he was arrested for lewd behavior in a public park with a 16 year old teen boy. They were both detained and placed in juvenile hall for three days as punishment.

”… the judge or whatever he was told me and my parents that I was in danger of leading a lewd and immoral life.”

The arrest made Kuromiya feel like a criminal. The sense of shame forced him to keep his sexual identity a secret.

But those repressed feelings drove him to fight oppression. While attending the University of Pennsylvania in the early 1960s Kuromiya got involved with the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) in their efforts to desegregate Maryland diners. Then in August 1963, he attended the March on Washington (along with 250,000 others) to demand justice for all citizens. At the end of the march Martin Luther King Jr. made his famous "I Have a Dream" speech.

That evening Kuromiya had the opportunity to meet King and other Civil Rights leaders. He formed a friendship with King and became his assistant. He participated in the March on Washington and in the voter registration campaign with Black Students in Montgomery, Alabama.

As part of his anti-war efforts Kuromiya designed the “Fuck the Draft” using the pseudonym Dirty Linen Corp.

As a gay man, Kuromiya also sought equality and freedom for other gay people. In 1965 he participated in the “Annual Reminder” at Independence Hall, one of the earliest rallies to remind the public that LGBT people did not have basic civil rights protections. He used the occasion to publicly announce he was Gay.

After the Stonewall riots in 1969, Kuromiya helped to organize the Philadelphia chapter of the Gay Liberation Front. With the advent of the AIDS crisis he was involved with the creation of ACT-UP and was the editor for the organization’s “Standard of Care”, the first medical treatment and competency guidelines for people living with HIV/AIDS.

Kuromiya was diagnosed with AIDS in 1989. Then he suffered a recurrence of lung cancer that he had survived in the 1970s. But that didn’t stop him. He insisted on receiving the most aggressive treatment for his cancer and it’s impact on his HIV drug regimen. And participated in every treatment decision. Kuromiya died of complications from cancer in May 2000.

“I'm a twenty-year metastatic lung cancer survivor and a fifteen-year AIDS survivor. And I really believe that activism is therapeutic.”

#gay icons#Kiyoshi Kuromiya#Japanese American#Martin Luthor King Jr#civil rights#gay rights#ACT-UP#Fuck the Draft#stonewall riots#AIDS Standards of Care

83 notes

·

View notes

Text

By: Christopher F. Rufo

Published: Jan 17, 2024

This year’s Martin Luther King, Jr. Day was marked by contentious debate about the state of civil rights law in America.

On the left, as always, the failure to achieve equal outcomes along racial lines requires greater state intervention. On the right, a different critique has gained traction, most notably in Christopher Caldwell’s Age of Entitlement and Richard Hanania’s The Origins of Woke, books arguing that American civil rights law has metastasized into a “second Constitution” that has led inexorably to left-wing racialism as the nation’s new orthodoxy.

This critique has merit. The modern civil rights regime has assumed unprecedented power to reshape public and private life, regulating not only instances of outright discrimination but also the minutiae of thought, behavior, speech, and association. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 appealed to the noble principle of equality, but over time the legal structure that it helped establish has metamorphized into an intrusive “diversity and inclusion” bureaucracy that discriminates against supposed “oppressor” groups—namely whites and Asians—and imposes left-wing ideology.

The question is what to do about it. Libertarians have long argued that the Civil Rights Act compromises core freedoms of speech and association to such a degree that only repealing the law can restore them. Another faction argues that the solution to minoritarian identity politics is majoritarian identity politics—that is, if the legal regime has become a racial spoils system, then Americans of European descent must develop “white racial consciousness” and fight for their share.

Both these approaches are misguided. Some conservatives seem to have forgotten that the Civil Rights Act was a response to state-sanctioned racial injustice in the United States and that, at its best, the civil rights movement appealed to the ideals of the Declaration of Independence and the language of the Fourteenth Amendment. The libertarian proposal for abolishing the Civil Rights Act, like most libertarian proposals, is unfeasible. The white identity proposal, which I have previously criticized, is a recipe for permanent racial division, more akin to “prison gang politics” than republican virtue.

Happily, another avenue is open to us: reform. The ideological capture of the Civil Rights Act is neither fixed nor inevitable. Rather than argue for its abolition, Americans concerned about the excesses of the DEI bureaucracy should appeal to higher principles and demand that our civil rights law conform to the standard of colorblind equality. The answer to left-wing racialism is not right-wing racialism—it is the equal treatment of individuals under law, according to their talents and virtues, rather than their ancestry and anatomy. This policy does not require radical innovations. Embracing the philosophy of the American Founding—with its emphasis on natural rights and liberties—will suffice.

What would this new civil rights agenda look like in practice? First, reformers should outlaw affirmative action and racial preferences of any kind. Both policies are euphemisms for racial discrimination. The next president should rescind Lyndon Johnson’s 1965 Executive Order 11246, which established “affirmative action” and marked the initial deviation from the standard of colorblind equality. Congress should strengthen this principle by amending the language of the Civil Rights Act to make indisputably clear that the law will not permit state-sanctioned discrimination toward any racial group, whether in the minority or the majority.

Second, reformers must eliminate the “disparate impact” provisions in the Civil Rights Act of 1991 and overturn Griggs v. Duke Power Co., both of which have entrenched the doctrine that disparate group outcomes are de facto evidence of racial discrimination. This is a preposterous standard: a system of equal rights necessarily means unequal outcomes, as different groups have different preferences, talents, and capacities. Under a just system, the criterion for assessing biased treatment would not be disparate outcomes but specific, concrete discrimination, driven by animus. Much as libel law requires actual malice, anti-discrimination law should require proof that an individual or institution sought to discriminate. The change in standard would have an immediate effect, reducing the number of frivolous lawsuits and changing the incentives that have driven institutions toward racialist ideology as a defensive strategy.

Third, legislators should abolish the DEI bureaucracies in all American institutions, which openly discriminate against disfavored racial groups, impose ideological orthodoxies on American citizens, and restrict freedoms of speech and association. In addition, federal legislators should radically reduce the size of the federal departments of civil rights enforcement. Bureaucracies are designed to discover—or, if the supply is low, fabricate—whatever transgression they are tasked with eliminating. While a large civil rights enforcement apparatus may have been necessary to enforce non-discrimination law in the past, it is no longer necessary. Americans are a tolerant, cooperative people; a “night watchman” civil rights state and a competent courts system would be sufficient to resolve disputes and ensure compliance with the law.

The goal of these reforms is finally to realize a regime of full colorblind equality. The principle, first promised by the Declaration and supported today by a large majority of Americans, would mean that the state would treat all Americans equally, regardless of ancestry, and leave as much discretion as possible to individuals to determine their own futures, without the government imposing or requiring racial favoritism of any kind. Rather than pit ourselves against one another, we should aspire to a higher standard that subordinates racial faction to a broader national identity.

Americans do not have to accept the bigotries of the past or the present. In a vast and diverse country, colorblind equality is the only way forward.

#Christopher F. Rufo#Christpher Rufo#colorblindness#color blindness#colorblind#color blind#equality#equity#equality vs equity#DEI#DEI bureaucracy#diversity equity and inclusion#inclusion#diversity#racial discrimination#Civil Rights Act#Civil Rights#Civil Rights Movement#diversity and inclusion#religion is a mental illness

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

On this day, 30 November 1963, Black tenants in four rundown tenement buildings in Rochester Avenue, Brooklyn, went on rent strike, as part of a wave of rent strikes across the city in protest against slum conditions. The Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) announced that 11 families were withholding rent, joining 750 families in Harlem on rent strike. They were demanding that the city take over and renovate buildings at 104, 106 and 112 Rochester Ave, and that 110 Rochester Ave be condemned. Marshall English, a New York CORE activist, told the New York Times: "We have talked with landlords, big landlords and have met with a number of city agencies… So far the result has been nil… When the landlord is faced with no rents, then we get some action". * We only post highlights on here, for all our anniversaries follow us on Mastodon: https://mastodon.social/@workingclasshistory https://www.facebook.com/workingclasshistory/photos/a.296224173896073/2148957475289391/?type=3

183 notes

·

View notes