#Black Health

Text

#@qimmahrusso#blackisbeautiful#blackwomen#blackwomenbelike#blackwomenaregorgeous#black fitness#black fitspiration#black health#blackwellness#blackisavibe#blackbeauty#afrocentric#brownskinbeauties#brownskingirls#blackwomenarestunning#beautifulblackwomen#blackgirlmagic#blackgirlaesthetic#blacktumblr

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

As fans and co-stars mourn the untimely death of actor Andre Braugher, there is a new emphasis on the pervasiveness of lung cancer among Black men and why they are more likely than other groups to die from the disease. The “Brooklyn Nine-Nine” star passed away last week, just months after his diagnosis, according to a statement from his publicist.

According to the American Lung Association, one in 16 Black men will be diagnosed with lung cancer in their lifetime. But while research has shown that a diagnosis doesn’t necessarily have to be a death sentence, Black men still have the highest death rate of lung cancer in the country — a grim stat partially due to the fact that they’re often diagnosed at later stages than others. Only 12 percent of Black men receive their diagnosis at an early stage, compared to 16 percent of white men and 20 percent of white women.

damn

117 notes

·

View notes

Photo

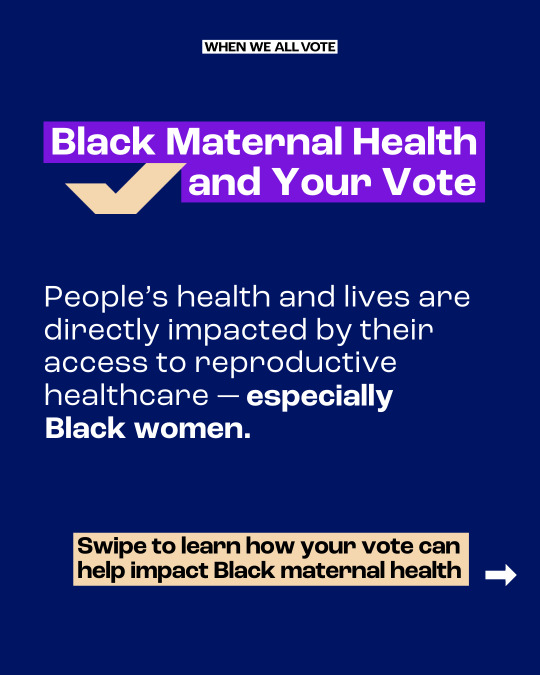

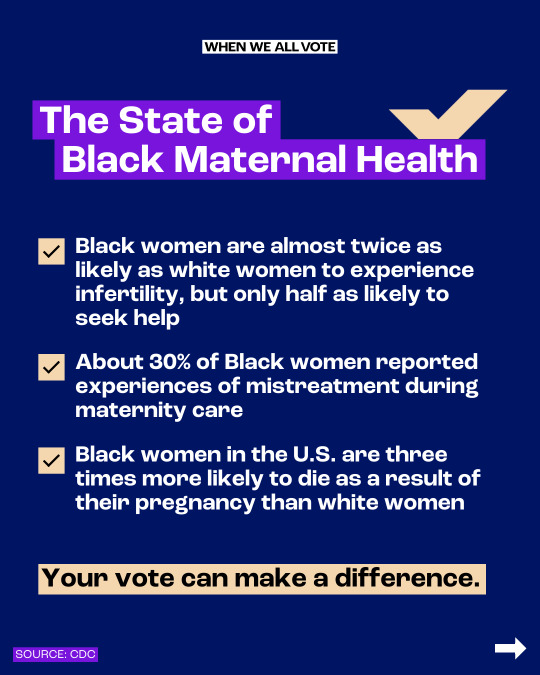

This Black Maternal Health Week, we’re bringing awareness to the staggering rates of Black maternal mortality and morbidity across the country.

Black mothers deserve access to the healthcare they need throughout pregnancy, childbirth, and postpartum.

The people we elect make decisions that impact our access to reproductive healthcare. Make sure you are registered to vote NOW at weall.vote/register. 💜

#black maternal health week#black maternal health#black women#black moms#black mothers#black health#reproductive health#reproductive justice#reproductive freedom#vote#voting#voter#register to vote#ballot#election#elections#black lives matter#blm

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Keep our black women out the hospital as much as possible. Protect them .

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

#black lives matter#aclu#black lgbt#lgbtqi#black stories#black girl magic#black man#black history#black men#black music#black panther#black love#blacklivesmatter#black pride#black history month#black people#black woman#black women#black femininity#black health#black doctors#black community#black beauty#black brothers#black sisters#NAACP#civil liberties#civil rights

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

YourTango: If You’ve Been Keeping Your Childhood Trauma A Secret, You Need To Read This

You’ve kept your childhood trauma a secret out of shame and fear. There was no one safe to tell. Now, you don’t know who you can trust. If you open up, you’re afraid of being judged or punished. It’s a lonely way to live and bad for your mental health.

Childhood trauma is devastating, no matter what form it takes. It affects your self-esteem, trust, future relationships, and sense of safety in the world. And, no matter what you do to forget, the secrets haunt you every day.

You know some of the reasons you’ve kept secrets, but is there more? Plus, you wonder, are some of the things you’re struggling with caused by your secrets?

Yes, keeping secrets can cause psychological symptoms and problems. So, let’s talk about 6 reasons why you might be keeping your childhood trauma a secret, how secrets lead to psychological problems, and what you can do about it now.

You have your reasons for keeping your trauma a secret. Everyone is different and trauma uniquely affects each child. Yet, there are some common things.

They have to do with what you felt, what you believed about people and yourself, and the only way you knew to manage your trauma. Maybe you can relate to some of these 6 reasons for keeping trauma a secret.

RELATED: 5 Ways To Heal Your Childhood Trauma (So You Don't Have To Suffer Any Longer)

1. You wondered if it was your fault

If your trauma was a form of abuse or even a loss, you might feel it’s your fault.

Children often blame themselves when they have no other way to interpret what happened. Or, when you got yelled at and felt bad. Even if you lost a parent, you might think you made it happen because you needed too much or got angry.

It’s not true. None of it was your fault. But, you’re vulnerable as a child to what you’re told. And to your fantasies and misinterpretations of your trauma and early life.

Now you have a taunting self-critical voice in your head that tells you all kinds of negative things about yourself. That voice makes you feel bad.

If you were yelled at, called names, or criticized as a child, it’s the voice of the parent who picked on you. That voice lives inside you and makes you feel to blame for everything.

This is a terrible thing to live with. It makes you close off to people. You can’t openly be yourself because you truly feel you have things to hide. Or that no one will like who you are.

When you live with such bad feelings, it’s hard not to feel shame. If you can’t be openly who you are, you can't open up about your trauma.

All you want to do is forget what happened. You don’t see any other choice.

2. You don’t want to remember

“Forgetting” or, at least detaching from the feelings you had in (and about) your trauma, is a typical reaction. It’s called dissociation. And it’s a way of protecting yourself during the traumatic experiences — to feel as if you weren’t there.

This kind of self-protection continues if you don’t get psychological help.

You might live a fairly detached emotional life. Maybe you even have OCD to control your feelings. Of course, you don’t want to remember.

Childhood trauma is too scary and the feelings are overwhelming. Especially when there is no one there to help you or understand the feelings you have. You were alone with it.

You try your best to push aside memories if they start to come back. What else can you do? When you convince yourself not to talk about it, then you are alone now too.

3. Remembering makes you relive it

One of the reasons you don’t want to think about it and try so hard not to, is that remembering makes you relive the trauma. Sometimes it comes back in flashbacks. You feel like you are there. Little and scared and helpless. It’s all real.

So, not only does the idea of telling your secret make you feel ashamed and afraid of humiliation. But, opening up your childhood trauma in any way makes you feel that it’s happening all over again. All the feelings flood back into it. It’s just too much.

You tell yourself, you can do it. Just push it away, don’t think about it, keep yourself busy. You’re convinced it should work. There isn’t any other way to deal with it. You keep telling yourself over and over, “It’s in the past. Isn’t it? Just move on.”

RELATED: The Common Phrase People With Unresolved Childhood Trauma Say Without Even Realizing It

4. You wonder if it is better to move on

You don’t want to open up your secrets. That’s too scary especially when thinking about it by yourself is overwhelming. The only thing that makes sense is to “forget about it” and move on.

You can’t think of any other way to deal with your childhood trauma. So you have to believe that just moving on is the only thing to do.

Yet, sometimes you still have flashbacks. or memories. Even symptoms of anxiety and depression. You feel socially anxious. It’s hard to relax and completely trust. That’s one reason you keep secrets. But, it’s also a difficult way to live. You can’t get close to anyone and it’s sometimes a lonely life.

But, the very thought of letting your secret out to anyone, makes you wonder who? You’re not sure if anyone is safe enough to trust. Who wouldn’t humiliate you? And, you don’t believe that anyone could understand.

5. You think no one would understand

Childhood trauma makes it extremely difficult to trust. So, you’ve had to go it alone in most ways in your life. You were betrayed by the people you were supposed to trust, the ones who were supposed to take care of you. They didn’t understand. Far from it. Instead, they deeply hurt and emotionally scarred you.

Sometimes you think that no one you meet has suffered the way you have. Intellectually you know that other people have suffered trauma too. But, you don’t know anyone who has. Or, at least, no one has talked about it either. So, where would you find someone to understand? It seems virtually impossible.

And, what if you tried to talk to someone who hasn’t had trauma? Could they remotely “get” what you’ve gone through? How hard it is to open up?

Not believing anyone can understand makes you more lonely. Plus, if you’ve been hurt a lot since childhood, this only reinforces your conviction that keeping your secret is the only way to go. Yet, is it?

Here are some reasons why keeping secrets might not be in your best interest:

1. “Forgetting” doesn’t work

Remember. “Forgetting” is the very common psychological defense of dissociation, detachment, or numbing. Every traumatized person reacts this way. It’s the only way you can protect yourself when you’re being hurt or abused as a child. Especially when the ones who should be helping you hurt you instead.

You want to believe you can forget. Forgetting is your best attempt to keep your trauma a secret from yourself. You think, at least you want to believe, that if you don’t open it up in your mind, it will go away. Certainly, you wish it would. But, it doesn’t work. If you stop to think about it, you know that too.

You are still suffering.

RELATED: Experts Reveal The Most Common Childhood Complaint They Hear In Therapy

2. Secrets eat away at you

Your secrets are living in your symptoms. Eating away at you. You’ve tried your best to move on, but you still have flashbacks or nightmares. Intrusive thoughts and memories enter your mind. Even if you don’t realize it consciously, it’s true.

These secrets of your childhood trauma affect your life every day.

No one keeps a secret unless they feel it’s too awful to tell. And, childhood trauma is awful. That’s the truth. Childhood trauma leaves deep scars.

But, if you live with your trauma in secret, it affects you more. Those secrets eat away at you. They eat away at your self-esteem. Secrets make you feel worse about yourself because you think there’s some shame in telling. There’s not.

But, if you believe that, you can’t get help. Your symptoms continue, even if you try to forget.

3. Untreated trauma creates symptoms

The symptoms of trauma take many forms. You’ve tried to forget and go numb.

Yet, you might still experience persistent episodes of depression. Maybe an eating disorder. OCD is a frequent result of childhood trauma. Even unrelenting physical symptoms, such as gastrointestinal problems, can be the places where your childhood trauma lives.

You can’t go on forever in a state of numbness. Eventually, like novocaine or a sedative, it wears off. Something in you comes alive.

If you don’t have a conscious memory or flashback, you have anxiety or depression. Sometimes it can be really bad. Or your OCD takes over and gets worse. You might even feel panicky and not know why.

These are all forms of the psychological problems a secret begins to take. Yet, these are symptoms. And, underlying these symptoms are deeper scars.

The scars of childhood trauma affect your self-esteem and your trust in people. They're expressed in your difficulty forming close relationships. Even having the work or creative success you want. These scars hide away in your symptoms of depression, anxiety, panic, OCD, physical problems, or eating disorders.

But, these psychological symptoms are clues. They’re signals that your childhood trauma is trying to get your attention. That you need some help. And, keeping secrets makes it impossible to get them.

Secrets make you stay away from psychotherapy too. For childhood trauma, therapy can change your life.

What needs to be understood are the very particular ways your trauma is repeating itself in how you feel about yourself, your dreams, the critical voice in your head that creates your shame, and your fears of closeness and intimacy.

What is being played out is unique to you and your history, different for each traumatized child.

Think about it. Keeping secrets might have seemed the only way to go. Especially since you’ve been convinced you’ll be judged or hurt again. Or that no one will understand. But, there are experts in treating childhood trauma.

And, these experts do know about and understand the reasons for secrets and your distrust.

Where do you start? Look for a psychotherapist who specializes in childhood trauma. If you can, find an expert who also has psychoanalytic training. Why?

Because a psychoanalyst has the knowledge to get to the early roots of your trauma. You aren’t just living with symptoms. The symptoms are expressions of what happened to you.

Once you can take the risk and decide it’s best to tell your secrets to someone who understands, it's important to be in a therapy that gets to the roots of how your childhood trauma, earliest relationships, and history still affect your life.

You don’t have to be alone with the feelings you’re so afraid will all come flooding back.

You need kindness. Understanding. Help develop trust. A therapist who not only gets to the roots but will invite and be with any feelings you have, including your anger. There are therapists who can. If this isn’t happening, move on. In good therapy, telling your secrets and getting help will change your life.

RELATED: The Sad Reason Why Childhood Trauma Is Holding You Back As An Adult

Dr. Sandra Cohen is a Los Angeles-based psychologist and psychoanalyst who specializes in working with survivors of abuse and childhood trauma.

This article was originally published at Sandra E. Cohen's blog. Reprinted with permission from the author.

#Childhood Trauma#Black Trauma#Trauma#childhood trauma#Black Health#Black LIves Matter#Sandra Cohen#Black Mental Health Matters

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

How Black WWI veterans got their own VA hospital in Tuskegee : NPR

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

#eds zebra#ehlers danlos zebra#zebras of color#people of color#poc#poc health#ehlers danlos#ehlers danlos syndrome#black people#african diaspora#african american#african americans#african american healthcare#health#healthcare#black health#black healthcare

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Health is wealth.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Get life insurance

25 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

The Shocking Truth About Heavy Metals… and How To Protect Yourself!

Heavy Metals are in just about everything... Watch this video to find out WHERE they are, HOW they are entering your body, and most importantly, how you can detox and protect yourself right now!

Are you suffering from heavy metal toxicity? You may have chronic symptoms like fatigue and brain fog, which can be caused by heavy metals. If you have any chronic symptoms, it may be worth it to take steps toward detoxing from heavy metals and avoiding them in the future so that you feel better.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

It's crazy how your relatives will speculate all types of illnesses when you tell them your symptoms. But when you actually show your symptoms all of a sudden you're lazy and "too young" for all that.

#black folks be wilding fr#i say im in pain everyday and yet you still have me caring the heaviest items in the house#i say my back hurts but when im lying down you've got problems#i hate it here#chronic pain#chronic illness#black health#physical illness#illnesses#jay's tism thoughts#tw ableism

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

A physician explores the obstacles keeping Black people out of medicine

When Dr. Uché Blackstock and her twin sister graduated from Harvard Medical School in 2005, they became the school’s first Black mother-daughter legacies. Their mother had received her medical degree three decades before and had an enormous influence over Blackstock’s career ambitions.

“She was a leader of a black woman physician group in Brooklyn. And so for many years, I thought that most physicians were Black women,” Blackstock said in an interview with “Marketplace” host Kai Ryssdal. “Until I got to college and medical school, and I realized that we actually are only about less than 3% of all physicians.”

From an early age, my twin sister, Oni, and I loved to play with our mother’s doctor’s bag. It was an old-school, heavy black leather bag, worn and cracked around the edges, that snapped open from the top to reveal the medical instruments inside. Her full name was written in faded golden uppercase letters across one side of the bag, followed by “M.D.” The bag lived in her bedroom, under her bureau. As children, we were always getting into her business, whether it was looking through old papers and photographs in the small file cabinet in her room or pulling out shoes and scarves from her closet. We knew that the medical bag was important to her, so that made it important to us.

Whenever we could, we snuck up into her room, emptying out the contents of the bag on the floor: her stethoscope, with its long rubber tubing, the little hammer to test reflexes, the otoscope for ear exams, the ophthalmoscope for looking at the eyes. Then we’d sit and play doctor together. I’d listen to the thump, thump, thump of my sister’s heart with the stethoscope in my ears or I’d hop up onto the bed so Oni could hit just under my knee with the reflex hammer, making my leg flip up quickly. If our mother came in and found us mid-game, she would smile warmly. She was a petite woman who wore her hair natural and in a small Afro.

“Girls, please be careful with those. They’re all quite delicate,” she warned us.

Except for the stethoscope, I didn’t know any of the names of the precious contents of the bag, but I understood these were the tools of our mother’s trade. By the time my sister and I got to Harvard Medical School, the instruments were as familiar to us as the forks and spoons in our kitchen.

The children’s advocate Marian Wright Edelman once famously pointed out, “You can’t be what you can’t see.” Growing up in Brooklyn in the 1980s and ’90s, we saw Black women who were physicians all around us. Our mother practiced medicine at Kings County Hospital Center and its state affiliate, SUNY Downstate Health Sciences University, not far from our home in central Brooklyn. Our own pediatrician, Dr. June Mulvaney, was a Black woman. We loved going to see Dr. Mulvaney, even if vaccinations were involved, because she was a bespectacled, kind older woman with soft hands and an even softer smile, who was a good friend of our mother’s. Another Black physician, Dr. Mildred Clarke, an obstetrician-gynecologist, lived on our block. We would often see Dr. Clarke while out running errands, stopping to chat about the most recent neighborhood news. Our mother was the president of an organization of local Black women physicians that included Dr. Clarke and Dr. Mulvaney. They were all very put-together, fiercely intelligent women who held themselves with pride and devoted their little spare time educating their community through holding events like local health fairs.

From the day she gave birth to us at Columbia-Presbyterian Hospital in the Washington Heights section of Manhattan, our mother was determined that my sister and I should have every opportunity she had lacked. We grew up in the home our family owned on St. Mark’s Avenue in Crown Heights, Brooklyn. Back then, Crown Heights was a bustling neighborhood that was home to many middle-class and working-class families, a uniquely Brooklyn mix of Black Americans and immigrants from the Caribbean like our father, Earl Blackstock, who was born in Jamaica. Our mother was constantly reading to us as small children, bringing us to the library for story time or taking us on educational adventures in Prospect Park and the Brooklyn Botanic Garden. When we got older and entered grade school, she was the kind of mother who didn’t hesitate to give us extra assignments if she felt our teachers weren’t assigning enough challenging work. If we had friends over for sleepovers, she’d cue up the movie and popcorn, and when the movie was over, she’d announce it was time to do our math worksheets. Our friends, who also had to do the worksheets, didn’t seem to mind too much—somehow, she made it all seem like part of the fun. Saturdays were for a host of extracurricular activities: violin lessons, music theory, modern dance, and gymnastics. I can still picture her, leaning against the sink in our old kitchen, scouring the newspaper for educational activities while we were on vacation from school. Her goal was to keep us stimulated—always. Much to our dismay, we were rarely allowed to watch television. On weekends and holidays, we went to the most popular NYC museums, the United Nations, science exhibits, with our mother narrating, explaining, pointing things out as we went along. Even a walk around our neighborhood was an educational adventure, with her perusing her pocket-size book on flowers and pointing out the different types in our neighbors’ front yards.

“Girls, come over here. Look at these gorgeous azaleas,” she’d say to us, bending down to touch the flowers lightly with her slender fingers. “They bloom only in the springtime,” she’d continue as we peered over her shoulders.

Looking back, I think she understood that this world was going to be tough on us and she needed to make sure we were fully prepared, but also that we experienced moments of joy.

For our mother, science was part of that joy. Once we went to a science exhibit where there was a real cow’s eyeball on display so that kids could pick it up and see how an eye worked. At first, my sister and I recoiled from touching the large white eye with its spidery blood vessels, but our mother persuaded us to cradle the strange object in our hands, then she leaned in close and explained the mechanisms of the eye to us in great detail. What had scared us a few moments before became a way to introduce us to the wonder of sight.

When summer came around, she signed us up for science programs, including one at her hospital, where she taught some of our sessions. Her specialty was nephrology, the study of the kidneys, and I have a clear memory of sitting in class at age twelve, with a small group of other students, watching her standing in front of the chalkboard, wearing her long white coat over her small frame. I felt so proud to have her up in front of the room teaching a classroom of my peers.

As she took a big piece of white chalk, she asked us, “Did you know that the kidney is one of the most sophisticated organs in our bodies?”

She drew a long looping shape on the board, exclaiming, “And this is the nephron, the smallest unit of the kidney! It’s a powerhouse.”

I remember her pulling a cylinder-shaped filter from a dialysis machine, to show us how it processed the blood from patients. She explained to us, in easy-to-understand terms, how this plain looking filter saved lives. It was in that moment, sitting in that classroom as a twelve-year-old on a hot summer day, that I realized the power of my mother’s work—to heal, to repair, to care. To be the difference between someone living and dying. I felt in awe of her.

I later learned that our mother chose her specialty, nephrology, because it’s one of the most difficult specialties in medicine—the kidneys are incredibly complex organs, and she loved a challenge. But I believe she also went into the field because kidney disease disproportionately affects Black people, and she wanted to help in some way. Because poorly controlled blood pressure and blood sugar negatively impact the kidney’s function, many of her patients also had these conditions, which were the result of lack of access to quality care and the chronic pressure of living with racism and other structural inequities. In her work, my mother was determined to address these entrenched health problems to the utmost of her abilities.

It wasn’t only patients who benefited from her time and attention. Black medical students and junior faculty at Downstate sought her out for inspiration and advice and she became a mentor to a generation of Brooklyn physicians, even inspiring those in health care who weren’t physicians, but physician assistants, nurses, and social workers. Many years later, as an adult, I ran into a former student of my mother’s at a medical conference in the city. We made eye contact across the room, and she smiled and made her way toward me, later saying that she had recognized me because I looked so much like my mother. She immediately introduced herself, hugged me tightly, and told me that when she was a third-year medical student doing her clinical clerkship, she had gone to see my mother and confessed how nervous she felt about presenting patient cases. She had explained how she was immobilized with fear and anxiety when it came her turn to describe the patient’s medical history and plan for treatment to the team. From then on, my mother met with her every morning, before the start of the day, so they could practice her oral presentations together. This wasn’t part of my mother’s role or responsibility at Downstate—she wasn’t even on the woman’s team. But my mother knew how it felt to be a student looking for that kind of support, and so she became the mentor she wished she’d had. Today, that student is the associate dean in the Office of Diversity Education and Research at a New York City medical school.

Our mother was tireless in her work ethic. Even after she left the hospital, her work wasn’t done. Back then, she was president of the Susan Smith McKinney Steward Medical Society, a local organization of Black women physicians named after the third Black woman to obtain a medical degree in the US and the first in New York state. During the society’s regular meetings, Oni and I would sit in the back of a large conference room, doing our homework, whispering, or passing silly notes back and forth, as my mother and her colleagues handled their serious business. They spent considerable time planning community health fairs, where they would dispense information about diabetes, high blood pressure, and other health issues rampant in our community. At the fairs, they would take people’s vital signs, recommend follow-up services, and counsel neighbors about healthy diet and exercise. Our mother and the other women in her organization were our role models. They worked, they raised children, they took care of their households, and they gave back to their communities.

I don’t think it ever occurred to Oni and me to do anything else with our lives but to follow in their footsteps.

From Legacy by Uché Blackstock, MD, published by Viking, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2024 by Uché Blackstock, MD.

#A physician explores the obstacles keeping Black people out of medicine#Black Health#Black Doctors Matter#Healthcare in Black Communities#Black Lives Matter#Uché Blackstock

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

4 notes

·

View notes